- Chongqing Key Laboratory of Photoelectric Functional Materials, College of Physics and Electronic Engineering, Chongqing Normal University, Chongqing, China

New diluted magnetic semiconductors represented by Li(Zn,Mn)As with decoupled charge and spin doping have received much attention due to their potential applications for spintronics. However, their low Curie temperature seriously restricts the wide application of these spintronic devices. In this work, the electronic structures, ferromagnetic properties, formation energy, and Curie temperature of Cu doped LiMgN and the corresponding Li deficient system are calculated by using the first principles method based on density functional theory, combined with Heisenberg model in the Mean-Field Approximation. We find that the Cu doped systems have high temperature ferromagnetism, and the highest Curie temperature is up to 573K, much higher than the room temperature. Li(Mg0.875Cu0.125)N is a half metallic ferromagnet and its net magnetic moments are 2.0 μв. When Li is deficient, the half metallic ferromagnetism becomes stronger, the magnetic moments increase to 3.0 μв. The bonding and differential charge density indicate that the half metallic ferromagnetism can be mainly attributed to the strong hybridization between N 2p and doped Cu 3d orbitals. The results show that Cu doped LiMgN is a kind of ideal new dilute magnetic semiconductor that will benefit potential spintronics applications.

Introduction

In the modern information technology, the transmission and processing of information mainly use the charge of electrons, while the storage of information mainly uses the spin of electrons. The two degrees of freedom are independent of each other. Diluted magnetic semiconductors (DMS) utilize the electron’s charge and spin degrees of freedom simultaneously to achieve novel quantum functionalities, which can combine the properties of semiconductor with ferromagnetism and have potential applications in spintronics (Ohno, 1998). Therefore, the designed spintronic devices have the advantages of lower energy consumption, faster running speed and smaller volume (Zutic et al., 2004; Dietl, 2010; Kacimi et al., 2014). However, there are some insurmountable difficulties for traditional III-V group based dilute magnetic semiconductors prepared by doping transition metals. For example, since the magnetic moments and carriers are provided by the same doped element, the binding effect of the spin and charge precludes the possibility of tuning electric and magnetic properties individually (Kaczkowski and Jezierski, 2009). The heterovalent substitution of Mn2+ into Ga3+ leads to severely chemical solubility of the magnetic ions (Potashnik et al., 2001). The average solubility for Mn is less than 1%, and only metastable films can be formed, resulting in that it is difficult to study the origin and mechanism of magnetism in dilute magnetic semiconductors Potashnik et al., 2001). Besides, the impurity ions often have higher ionization energy, restricting the contribution of free carriers in the system (Yan et al., 2007).

To overcome these difficulties, Mašek et al. (2007) theoretically proposed a kind of new diluted magnetic semiconductor Li(Zn,Mn)As based on I-II-V group elements, wherein magnetism due to isovalent substitution can be decoupled from carrier doping with excess/deficient Li concentrations. Deng et al. (2011), Jin et al. (2013) successfully prepared polycrystalline Li(Zn,Mn)As bulk materials with TC as high as ∼50 K. Muon spin rotation measurements have established that the magnetically ordered volume reaches 100% below TC, and the magnitudes of the ferromagnetic exchange coupling and the ordered moment are comparable to those of (Ga,Mn)As (Deng et al., 2011). Sato et al. (2012) theoretically calculated the electronic structures of Mn doped LiZnAs, LiZnP and LiZnN, and found that introduced Li vacancies could strongly suppress spinodal decomposition, induce ferromagnetic interaction and improve Tc in these systems. Following this, a series of new generation diluted ferromagnetic semiconductors, e.g., “111” type Li(Zn,Mn)P (Deng et al., 2013; Ding et al., 2013) and Li(Cd,Mn)P (Han et al., 2019), “122” type (Ba,K) (Zn,Mn)2As2 (Zhao et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2014),“1111” type (La,Ca)(Zn,Mn)SbO (Ding et al., 2014), and “32522” type (Sr3La2O5)(Zn,Mn)2As2 (Man et al., 2014), were successfully synthesized. A number of progresses of these new DMSs have been made on both fundamental studies and potential applications. Among them, the highest Tc is 230 K of the (Ba,K)(Zn,Mn)2As2 system (Zhao et al., 2014). However, it remains below room temperature.

Improvement of TC is always a fundamental issue for diluted ferromagnetic semiconductor materials. To explore new dilute magnetic semiconductor materials with better performance, in this work, the electronic structures, ferromagnetic properties, formation energy, and Curie temperature of Cu doped LiMgN and the corresponding Li deficient system are investigated by using the first principle calculation method based on density functional theory (DFT), combined with Heisenberg model in the Mean-Field Approximation. We find that the Cu doped systems have high temperature ferromagnetism, the highest Tc is up to 573 K, which indicate that Cu doped LiMgN is a kind of ideal new dilute magnetic semiconductor.

Computational Details

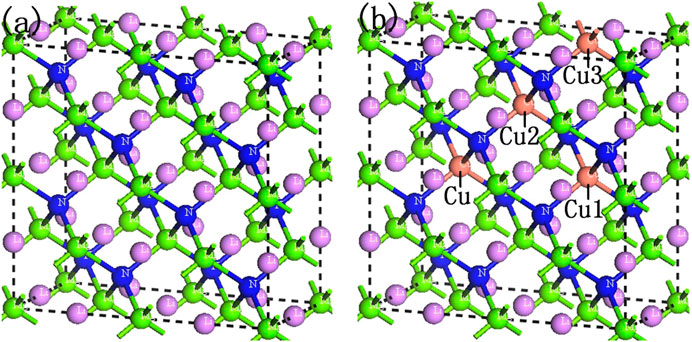

LiMgN is an antifluorite structure (Kuriyama et al., 2002) with the lattice constant a = b = c = 4.955 Å, belongs to the space group F-43 m. It can be prepared by the reaction of Li, Mg and N2 at high temperature (800°C) (Kuriyama et al., 2002). The LiMgN tetrahedral lattice can be viewed as a zinc blende MgN binary compound, analogous to GaN, filled with Li atoms at tetrahedral interstitial sites near N. In the present work, a 2 × 2 × 1 (48 atoms) supercell of ZB-type LiMgN was constructed, containing 16 Li, 16 Mg and 16 N atoms, as shown in Figure 1A. Two Mg atoms were substituted by two Cu atoms, thus the doping concentration was 12.5%. When one Cu atom was fixed, another Cu atom was selected three asymmetric positions for comparison (as shown in Figure 1B). One Li atom closest to the Cu atom was removed in order to introduce a Li vacancy (VLi) in the 2 × 2 × 1 supercell.

All the first-principles calculations were carried out with the Cambridge Serial Total Energy Package (CASTEP) code (Segall et al., 2002) based on the density functional theory (DFT) method. The periodic boundary conditions were applied in all calculations, and the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) in Perdew Burke Ernzerhof (PBE) (Perdew et al., 1996) was performed to deal with the electronic exchange-correlation potential energy. In order to reduce the number of the plane wave basis vectors groups, the plane-wave ultrasoft pseudo potential (USPP) method (Vanderbilt, 1990) was implemented to describe the interaction between ionic core and valence electrons. The valence electronic states were Li:2s1, Mg:2p63s2, N:2s22p3 and Cu:3d104s1, respectively. The cut-off energy for the plane-wave was 400 eV, and the Monkhorst-Pack mesh was 3 × 3 × 6 for the integral calculation of the total energy and charge density in the Brillouin zone. The self-consistent convergence accuracy was set at 2.0 × 10−6 eV/atom. The structures of each doped configuration were optimized before the calculations of total energies and the electronic structures.

Results and Discussion

Electronic Structures

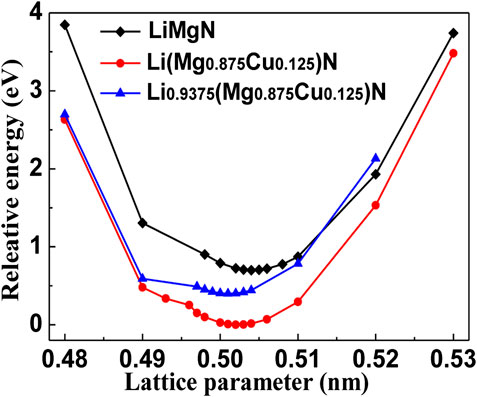

In order to achieve the equilibrium lattice constants, the structures of Li1-y(Mg1-xCux)N were optimized firstly. The geometry optimization curves are plotted in Figure 2. It can be seen that the optimized lattice constant for LiMgN is 5.04 Å, which is slightly overestimated comparing with the experimental value (4.955 Å) (Kuriyama et al., 2002). The optimized lattice constants of Li (Mg0.875Cu0.125) and Li0.9375 (Mg0.875Cu0.125) N are 5.02 and 5.01 Å respectively, slightly less than that of the pure LiMgN.

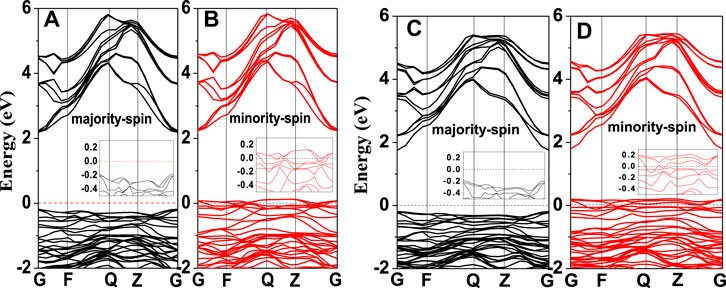

Pure LiMgN is a direct band gap semiconductor. The valence band is mainly composed of N-2p, Mg-2p state and Li-2s electronic states, and the conduction band is mainly composed of Mg-2p and Mg-3s electronic states. Figure 3 shows the spin polarized energy band structures of Cu doped LiMgN and the corresponding Li deficient system, and the inset is enlarged views of the vicinity of Fermi level. It can be seen in Figures 3A,B that some impurity levels are introduced near the Fermi level by Cu doping. In the majority-spin bands, the impurity bands merge into the valence band top, and the Fermi level still lies in the band gap, so the majority-spin bands remain semiconducting nature. While in the minority-spin bands, the Fermi level penetrates through the impurity bands, resulting in that two of the impurity levels cross the Fermi level, which demonstrates that the minority-spin bands exhibit metallic properties. So the Cu doped LiMgN system becomes a half-metallic material with 100% spin-polarized ratio of conduction electron. The spin-flip band gap is 0.13 eV (shown in Table 1). Figures 3C,D are the energy band structures of Cu doped LiMgN with Li vacancies. They are similar to that of Cu doped LiMgN, indicates that Li0.9375(Mg0.875Cu0.125)N also exhibits half metallic property. However, the minority-spin bands are somewhat different. The impurity levels across the Fermi level increase to three, and the spin-flip band gap increases to 0.22 eV, which indicates that the more robust half-metallic behavior to lattice deformation and temperature for Li deficient system.

FIGURE 3. The spin polarized band structures of Li(Mg0.875Cu0.125)N (A,B); and Li0.9375(Mg0.875Cu0.125)N (C,D). Inset: Enlarged views near Fermi level.

TABLE 1. The band gaps (Eg), the spin-flip/half-metallic gaps (HM gap), magnetic moments (M), and formation energies (Ef) of Li1-y(Mg0.875Cu0.125)N.

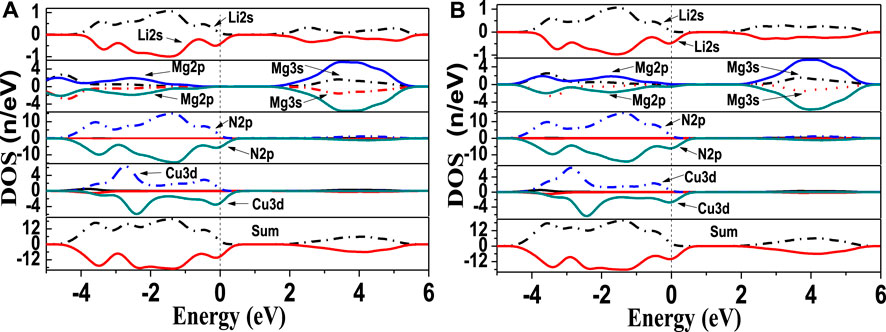

Figure 4 shows the density of states (DOS) of Cu doped LiMgN and the corresponding Li deficient system. It can be seen in Figure 4A that the sub-bands crossing the Fermi level mainly come from Li-2s, N-2p and Cu-3d states of the minority-spin. Besides, one can also note that a resonance peak appears near the Fermi surface, indicating that the electron orbitals of Li-2s, N-2p and Cu-3d states have strong sp-d hybridization near the Fermi level. The t2g energy level split from Cu-3d states of the minority-spin is pushed across the Fermi level, which makes it become a half-filled state. This causes that the states of the majority-spin are slightly more than those of the minority-spin, resulting in the net magnetic moments. The calculated net magnetic moments are 2.0 μв for Li(Mg0.875Cu0.125)N as shown in Table 1. Figure 4B shows that when Li is deficient, the DOS of Li-2s, N-2p and Cu-3d states near the Fermi level increase obviously. This indicates that the Li vacancies enhance the sp-d orbital hybridization. The t2g energy levels are pushed further above the Fermi level, which makes none of the three levels is occupied by electrons. This increases the spin-flip band gap and net magnetic moments for Li0.9375(Mg0.875Cu0.125)N. The formation energy of the two systems is also calculated and shown in Table 1. The stability of the doped system decreases slightly with respect to pure LiMgN.

Ferromagnetism and Bonding

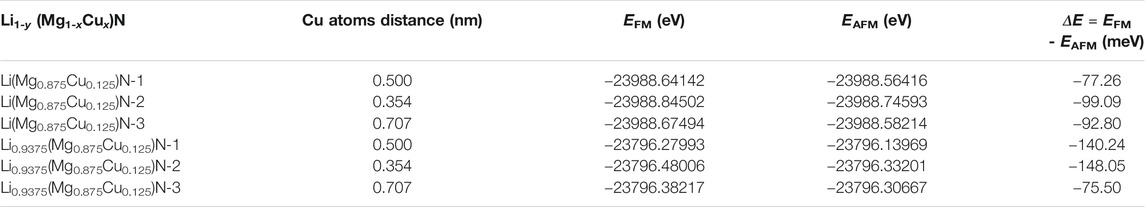

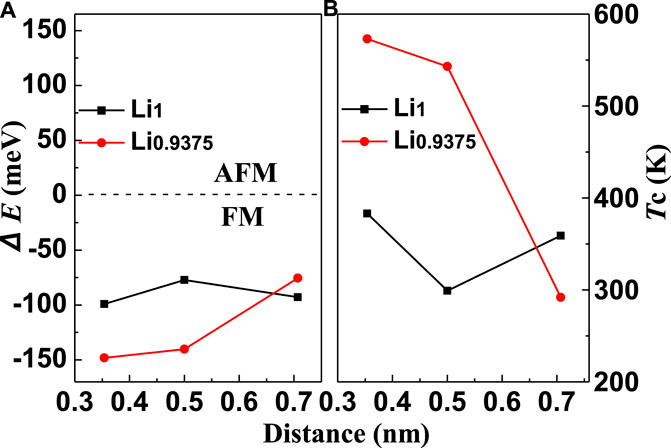

To explore the magnetic properties of the systems, the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic coupling energy of Li1-y(Mg0.875Cu0.125)N with different Cu doped position are calculated and shown in Table 2, where EFM is the ferromagnetic coupling energy of the systems, EAFM is the antiferromagnetic coupling energy, and ΔE is the difference between the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic coupling energy. It can be seen obviously that ΔE < 0 for each doped position, indicating that the ferromagnetic order is more stable than the antiferromagnetic order. The Cu doped LiMgN systems are half-metallic ferromagnet. To further understand the ferromagnetic properties of Li1-y(Mg0.875Cu0.125)N, the variation of ΔE with the distance between two Cu atoms is plotted in Figure 5A. It can be seen that ΔE decreases with the distance, implying that the half-metallic ferromagnetism become stronger as the two Cu atoms is closer. Moreover, when Li is deficient, the half-metallic ferromagnetism is further enhanced.

TABLE 2. The ferromagnetic and anti-ferromagnetic coupling energy of Li1-y(Mg0.875Cu0.125)N with different Cu doped position.

FIGURE 5. The energy difference of the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic state (A) and the Curie temperature (B) as a function of the two doped Cu atoms distance for Li1-y (Mg0.875Cu0.125)N.

The ideal DMS should have Curie temperature (Tc) higher than the room temperature. The Curie temperature of the Cu doped LiMgN systems is estimated by using the Heisenberg model in the Mean-Field Approximation (Sato et al., 2003):

where x is the number of doped particles, ΔE is the difference between the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic coupling energy, and KB is the Boltzmann constant. The variation of Tc with the distance between two Cu atoms is shown in Figure 5B. It can be seen that Tc of the doped systems is significantly enhanced when Li is deficient, and the maximum Tc is up to 573 K, much higher than the room temperature. Which shows that Cu doped LiMgN is a kind of ideal new dilute magnetic semiconductor that will benefit potential spintronics applications.

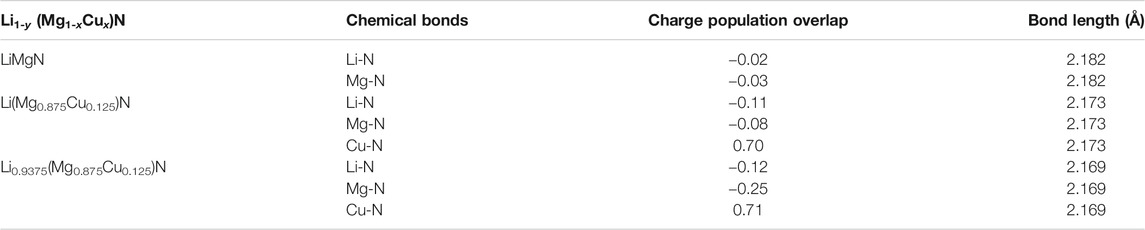

Table 3 shows the bond length and charge population overlap of the doped systems. It is found that the numbers of the charge population overlap for the Li-N and Mg-N bonds in pure LiMgN are negative, which indicates that they are ionic bonds. For Cu doped system, the numbers of the charge population overlap for Li-N and Mg-N bonds decrease. Meanwhile, the number of the charge population overlap for Cu-N bond is positive, demonstrating the covalent nature for the Cu-N bond, which is due to the strong hybridization between N 2p and doped Cu 3d orbitals. In general, the radius of Cu ion is larger than that of Mg ion. However, the bond length decreases for Cu doped system because of the Cu-N covalent bond nature, resulting in that the lattice constant also decreases. When Li is deficient, the numbers of the charge population overlap for Li-N and Mg-N bonds further decreases, whereas that of Cu-N bond further increases. This indicates that more charges transfer from the Li and Mg atoms to the Cu and N atoms, resulting in that the covalent nature for the Cu-N bond become stronger.

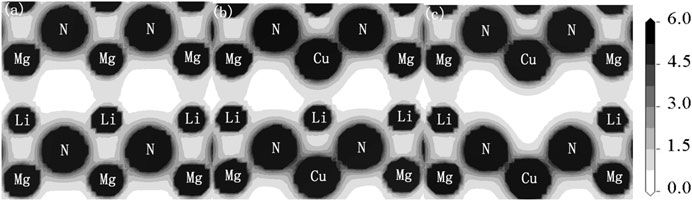

Figure 6 shows the charge density for Li1-y(Mg1-xCux)N along (2,2,1) plane. It can be seen that the values of charge density around Li and Mg atoms (Figure 6B) also decrease compared with those of pure LiMgN (Figure 6A). Besides, we can find that the charges transfer from the Li and Mg atoms to the Cu and N atoms, resulting in that the interaction between Cu and N atoms is stronger than that between Mg and N atoms. When Li is deficient, the charges further transfers and the interaction between Cu and N atoms become stronger. These results indicate that the effect of Cu doping on the ferromagnetic properties and bonding of the doped system is mainly attributed to the strong hybridization between N 2p and doped Cu 3d orbitals.

FIGURE 6. The maps of charge density for Li1-y(Mg1-xCux)N in (2,2,1) surface. (A) LiMgN; (B) Li(Mg0.875Cu0.125)N; (C) Li0.9375(Mg0.875Cu0.125)N.

Conclusion

In this work, the electronic structures, ferromagnetism, formation energy, and Curie temperature of Cu doped LiMgN and the corresponding Li deficient system are calculated by using the first principles method based on density functional theory, combined with Heisenberg model in the Mean-Field Approximation. We find that the Cu doped systems exhibit half-metallic ferromagnetism, which is helpful for spin injection. The net magnetic moments for Li(Mg0.875Cu0.125)N are 2.0 μв. When Li is deficient, the half-metallic ferromagnetism becomes stronger, the magnetic moments increase to 3.0 μв. The density of states, bonding and charge density indicate that the half-metallic ferromagnetism can be mainly attributed to the strong hybridization between N 2p and doped Cu 3d orbitals. Besides, we also find that the highest Curie temperature is up to 573 K when Li is deficient, much higher than the room temperature. These results indicate that Cu doped LiMgN is a kind of ideal new dilute magnetic semiconductor and will benefit potential spintronics applications.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The work described in this paper is supported by Chongqing Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. cstc2019jcyj-msxmX0251).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Deng, Z., Jin, C. Q., Liu, Q. Q., Wang, X. C., Zhu, J. L., Feng, S. M., et al. (2011). Li(Zn,Mn)As as a new generation ferromagnet based on a I-II-V semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 2, 422. doi:10.1038/ncomms1425

Deng, Z., Zhao, K., Gu, B., Han, W., Zhu, J. L., Wang, X. C., et al. (2013). Diluted ferromagnetic semiconductor Li(Zn,Mn)P with decoupled charge and spin doping. Phys. Rev. B 88, 081203. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.88.081203

Dietl, T. (2010). A ten-year perspective on dilute magnetic semiconductors and oxides. Nat. Mater. 9, 965. doi:10.1038/nmat2898

Ding, C., Gong, X., Man, H., Zhi, G., Guo, S., Zhao, Y., et al. (2014). The suppression of curie temperature by Sr doping in diluted ferromagnetic semiconductor (La1-xSrx) (Zn1-yMny) AsO. Eur. Phys. Lett. 107, 17004. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/107/17004

Ding, C., Qin, C., Man, H. Y., Imai, T., and Ning, F. L. (2013). NMR investigation of the diluted magnetic semiconductor Li(Zn1−xMnx)P (x = 0.1). Phys. Rev. B 88, 041108. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.88.041102

Han, W., Chen, B. J., Gu, B., Zhao, G. Q., Yu, S., Wang, X. C., et al. (2019). Li(Cd,Mn)P: a new cadmium based diluted ferromagnetic semiconductor with independent spin & charge doping. Sci. Rep. 9, 7490. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-43754-x

Jin, C. Q., Wang, X. C., Liu, Q. Q., SiJia, Z., ShaoMin, F., Zheng, D., et al. (2013). New quantum matters: build up versus high pressure tuning. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 56, 2337. doi:10.1007/s11433-013-5356-2

Kacimi, S., Mehnane, H., and Zaoui, A. (2014). I–II–V and I–III–IV half-Heusler compounds for optoelectronic applications: comparative ab initio study. J. Alloy. Compd. 587, 451. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.10.046

Kaczkowski, J., and Jezierski, A. (2009). Ab initio calculations of magnetic properties of wurtzite Al0.9375TM0.0625N (TM = V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni). Acta Phys. Pol. A 115, 275. doi:10.12693/APhysPolA.115.275

Kuriyama, K., Nagasawa, K., and Kushida, K. (2002). Growth and band gap of the filled tetrahedral semiconductor LiMgN. J. Crys. Grow. 237, 2019–2022. doi:10.1016/S0022-0248(01)02249-7

Man, H., Qin, C., Ding, C., Wang, Q., Gong, X., Guo, S., et al. (2014). (Sr3La2O5)(Zn1-xMnx)2As2: a bulk form diluted magnetic semiconductor isostructural to the “32522” Fe-based superconductors. Eur. Phys. Lett. 105, 67004. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/105/67004

Mašek, J., Kudrnovský, J., Máca, F., Gallagher, B. L., Campion, R. P., Gregory, D. H., et al. (2007). Dilute moment n-type ferromagnetic semiconductor Li(Zn,Mn)As. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 067202, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.067202

Ohno, H. (1998). Making nonmagnetic semiconductors ferromagnetic. Science 281, 951. doi:10.1126/science.281.5379.951

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K., and Ernzerhof, M. (1996). Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865

Potashnik, S. J., Ku, K. C., Chun, S. H., Berry, J. J., Samarth, N., and Schiffer, P., (2001). Effects of annealing time on defect-controlled ferromagnetism in Ga1-xMnxAs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 1495. doi:10.1063/1.1398619

Sato, K., Dederichs, P. H., and Katayama-Yoshida, H. (2003). Curie temperatures of III-V diluted magnetic semiconductors calculated from first principles. Europhys. Lett. 61, 403. doi:10.1209/epl/i2003-00191-8

Sato, K., Fujimoto, S., Fujii, H., Fukushima, T., and Katayama-Yoshida, H., (2012). Computational materials design of filled tetrahedral compound magnetic semiconductors. Physica B 407, 2950. doi:10.1016/j.physb.2011.09.036

Segall, M. D., Lindan, P. J. D., Probert, M. J., Pickard, C. J., Hasnip, P. J., Clark, S. J., et al. (2002). First-principles simulation: ideas, illustrations and the CASTEP code. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 14, 2717. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/14/11/301

Vanderbilt, D. (1990). Soft self-consistent pseudopotentials in a generalized eigenvalue formalism. Phys. Rev. B Condens Matter 41, 7892. doi:10.1103/physrevb.41.7892

Yan, Y., Li, J., Wei, S. H., and Al-Jassim, M. M. (2007). Possible approach to overcome the doping asymmetry in wideband gap semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 135506. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.135506

Zhao, K., Deng, Z., Wang, X. C., Han, W., Zhu, J. L., Li, X., et al. (2013). New diluted ferromagnetic semiconductor with Curie temperature up to 180 K and isostructural to the '122' iron-based superconductors. Nat. Commun. 4, 1442. doi:10.1038/ncomms2447

Zhao, K., Chen, B. J., Zhao, G. Q., Yuan, Z., Liu, Q., Deng, D., et al. (2014). Ferromagnetism at 230 K in (Ba0.7K0.3)(Zn0.85Mn0.15)2As2 diluted magnetic semiconductor. Chin. Sci. Bull. 59, 2524. doi:10.1007/s11434-014-0398-z

Keywords: Cu doped LiMgN, electronic structures, ferromagnetism, Curie temperature, first-principles

Citation: Deng J, Yang W, Hu A, Yu P, Cui Y, Ding S and Wu Z (2021) Ferromagnetism With High Curie Temperature of Cu Doped LiMgN New Dilute Magnetic Semiconductors. Front. Mater. 7:595953. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2020.595953

Received: 18 August 2020; Accepted: 28 September 2020;

Published: 23 February 2021.

Edited by:

Xiaotian Wang, Southwest University, ChinaReviewed by:

Xu Li, Chengdu University of Information Technology, ChinaYongtian Wang, North China Electric Power University, China

Liu Jun, Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications, China

Copyright © 2021 Deng, Yang, Hu, Yu, Cui, Ding and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shoubing Ding, c2hvdWJpbmdkaW5nQGNxbnUuZWR1LmNu; Zhimin Wu, em13dUBjcW51LmVkdS5jbg==

Junquan Deng

Junquan Deng Zhimin Wu

Zhimin Wu