- 1Clinical Nutrition Section, Department of Laboratory Medicine, The Third People's Hospital of Chengdu, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

- 2Department of Nutrition and Food Hygiene, School of Public Health, Medical College of Soochow University, Suzhou, Jiangsu, China

- 3Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Deyang People's Hospital, Deyang, Sichuan, China

- 4Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, The First People's Hospital of Yibin, Yibin, Sichuan, China

- 5Department of Gastrointestinal Hernia & Bariatric Metabolic Surgery, The Second People's Hospital of Yibin, Yibin, Sichuan, China

- 6Department of Gastrointestinal, Anal and Hernia Surgery, Nanchong Central Hospital, Nanchong, Sichuan, China

Background: Preoperative oral carbohydrates (CHOs) have been widely utilized to improve perioperative outcomes. However, the effect of postoperative early enteral nutrition (EEN) intervention on patients’ postoperative recovery has yet to be validated by prospective outcomes. This study was designed to investigate the effect of preoperative oral CHOs combined with ENN nutrition on postoperative recovery in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC).

Methods: A multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled study was conducted on 331 CRC patients who underwent radical resection from March 1, 2022, to March 1, 2023 and were divided into Group A (preoperative oral CHOs combined with postoperative ENN group, n = 110), Group B (preoperative oral CHOs group, n = 110), and Group C (conventional control group, n = 111) according to the method of the randomized numerical table. The general clinical data, inflammatory indices, nutrition-related serum biomarkers, immune function, postoperative intestinal function recovery, complications and hospitalization length of the three groups were statistically analyzed.

Results: The baseline characteristics were similar among the groups. In the intention-to-treat analysis, the time to first exhaust (p < 0.05) and defecation (p < 0.05) was significantly shorter in group A than in groups B and C. The total protein (TP) level was significantly greater in group A than in groups B and C on the seventh postoperative day (p < 0.05). In addition, the percentage of T-lymphocytes to lymphocytes on the third postoperative day was greater in Group A than in Groups B and C (p < 0.05), and the length of hospitalization was significantly reduced. However, there was no difference in the incidence of postoperative complications.

Conclusion: Preoperative oral CHOs combined with postoperative EEN improved serum markers related to postoperative nutrition, enhanced the immunity of the body, and promoted early recovery of intestinal function. Preoperative oral CHOs combined with postoperative EEN is conducive to rapid postoperative recovery and reduces the length of hospitalization.

Clinical trial registration: https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.html?proj=144616, identifier ChiCTR2100054459.

1 Introduction

According to the latest statistics provided by the WHO International Centre for Research on Cancer (IARC) in 2022, the incidence of CRC is increasing in China; it is the second most prevalent malignant tumor and the fifth leading cause of death (1, 2). Although neoadjuvant therapy and targeted drugs are gradually being utilized in the treatment of colorectal patients, radical resection of CRC is still the most dominant modality for the treatment of this disease (3). Numerous studies have shown that the probability of postoperative malnutrition in oncology patients can reach 40–70%, especially in gastrointestinal malignancies and elderly patients. Malnutrition negatively affects the host immune response and tissue healing process and is an independent risk factor for postoperative complications (4). Accordingly, the risk of postoperative malnutrition is greater in CRC patients undergoing surgical resection than in those receiving other treatment modalities (5).

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) is a paradigm shift in perioperative care, using a multimodal/interdisciplinary method to care for surgical patients, improving preoperative preparation, intraoperative treatment outcomes, and early nutritional support for postoperative recovery (6). As part of the ERAS program, preoperative oral intake of CHO beverages alleviated thirst, nausea, and vomiting caused by fasting, and attenuated serum levels of postoperative inflammatory markers [cortisol, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, IL-10] (7–9).

Patients with CRC often experience a state of high metabolic stress following surgery, accompanied by inflammatory responses and nutritional risks. Serologically, this manifests as decreased plasma protein levels and compromised immunity (10, 11). Nutritional management during the perioperative period is crucial, and proper nutritional support accelerates postoperative patient recovery and reduces the risk of postoperative complications, thereby shortening patients’ hospital stay (12). In recent years, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses have concluded that postoperative EEN reduces postoperative morbidity (especially infectious complications) (13), mortality (14), and length of hospital stay (15). However, the effect of preoperative CHOs supplementation combined with postoperative EEN on the postoperative recovery of CRC patients has not been reported.

The objective of this study was to explore the effect of preoperative CHOs supplementation combined with postoperative EEN on the postoperative recovery of patients with CRC and to provide new nutritional strategies for patients in the perioperative period.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

Participants were recruited from December 2021 to September 2022. Patients hospitalized at Deyang People’s Hospital, Yibin First People’s Hospital, Yibin Second People’s Hospital, or Nanchong Central Hospital with a diagnosis of colorectal malignancy who underwent laparoscopic CRC resection were included as study subjects. The purpose, procedures, and risks of the study were explained to each participant before inclusion, and all participants provided informed consent. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Deyang People’s Hospital (No. 2021–04-157-K01).

2.2 Study design

This study was a multicenter, double-blind, prospective, randomized controlled trial. All patients or their legal representatives signed provided written informed consent. The trial was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration and was registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry on December 17, 2021 with registration number ChiCTR2100054459.

2.3 Randomization and sample size

A random number table was used to determine patient allocation. Patients were randomized (1:1:1) into a preoperative oral CHOs combined with postoperative EEN group (Group A), a preoperative oral CHOs group (Group B) and a conventional diet group (Group C). The trial parameters were set as follows: two-tailed α = 0.05, 1-β = 80%. The trial utilized a 1:1:1 allocation ratio for the experimental and control groups. The sample size calculation formula, as implemented in PASS software, yielded a total of 333 cases, with 111 cases each in Groups A, B, and C. Accounting for a 10% dropout rate during the clinical trial, the actual enrolment target was set at 368 patients. The total number of subjects in each group is 123. In accordance with the established inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 331 patients were enrolled in this study and randomly assigned to Group A (n = 110), Group B (n = 110), and Group C (n = 111). During the course of the study, 16 patients elected to discontinue their participation: The distribution of patients across the three groups is as follows: 7 from Group A, 8 from Group B, and 1 from Group C. The study was completed and included in the statistical analysis by 315 patients across all three groups: 103 from Group A, 102 from Group B, and 110 from Group C (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the study participants. Among the study participants, 315 (94.87%) participated in this study throughout and completed the collection of baseline information and evaluation indicators.

2.4 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) age ≥ 18 years, either sex; (ii) laparoscopic radical surgery for CRC; (iii) NRS 2002 score ≥ 3 points (16); (iv) ability to take nutritional supplements orally; (v) no distant metastases detected on X-ray computed tomography (CT) scanning; (vi) American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification I–III (17); and (vii) fully accepted the study and signed a commitment form.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) patients with intestinal or pyloric obstruction; (ii) reflux esophagitis, Los Angeles classification A or above; (iii) patients with gastroparesis; (iv) patients receiving enteral nutrition (EN) or parenteral nutrition (PN) supplementation due to severe malnutrition (≥9 points on the PG-SGA (Patient-Global Assessment)); (v) patients with comorbidities with underlying diseases of vital organs and hepatic or renal insufficiency; (vi) patients already enrolled in other clinical trials; (vii) patients or authorized persons unwilling to participate; and (viii) patients judged by the investigator to be unsuitable for participation and potential disputes.

2.5 Treatment protocol

Nutritional risk screening was conducted by a dietician prior to enrollment, with NRS 2002 scores ≥ 3 required for enrollment.

Anesthesia protocol: (i) Intravenous access was established, patients were connected to a monitor and received oxygen, and invasive arterial monitoring was performed under local anesthesia. Patients without contraindications were recommended to receive NSAIDs preoperatively and early postoperatively, not exceeding 3 days. (ii) Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks, such as erector spinae plane blocks, thoracic paravertebral blocks, and transversus abdominis plane blocks, were performed before surgery. (iii) Dexmedetomidine (0.3 μg/kg) was added to 100 mL of saline infused over 15 min; it was not used if the preoperative heart rate was lower than 50 beats/min or in cases of atrioventricular block. (iv) Induction of anesthesia: 0.03–0.05 mg/kg midazolam, 0.3–0.5 μg/kg sufentanil, 0.6–1 mg/kg rocuronium bromide, 0.1–0.15 mg/kg cisatracurium, 0.3 mg/kg etomidate (or 1–1.5 mg/kg propofol), followed by tracheal intubation after 5 min. (v) Generally, infusion of crystalloids at a rate of 1.5–2 mL/(kg·h) was sufficient to maintain fluid homeostasis for abdominal surgery. Zero fluid balance was advocated. In addition to appropriate fluid supplementation, small doses of vasoconstrictor drugs could be used to prevent excessive volume loading, postoperative tissue edema, and slow gastrointestinal recovery. (vi) Maintenance drugs: 2% sevoflurane or 6 mg/kg/h propofol; BIS monitoring was applied to maintain an appropriate depth of sedation (BIS value of 40–60); the drug was adjusted according to the patient’s blood pressure and heart rate and was discontinued during skin closure. At the end of surgery, intravenous nalbuphine 10 mg and tropisetron 5 mg could be administered. Bowel obstruction, preoperative neoadjuvant therapy, and the use of anti-anaerobic drugs can increase postoperative PONV, and the prophylactic use of two or three antiemetic drugs is recommended. (vii) The endotracheal tube was removed after the patient regained consciousness and had good independent breathing, after which the patient was sent to the PACU. (viii) Management of patients during their stay in the PACU was carried out according to the management system of the anesthesia recovery room of the Department of Anesthesiology. Postoperative analgesia: Intravenous patient-controlled analgesia: formula: 2–2.5 μg/kg sufentanil + 3 μg/kg dexmedetomidine + 40 mg nalbuphine + 15 mg tolansetron diluted in saline to 150 mL. The analgesic pump settings were as follows: background dose 3 mL/h, PCA bolus 3 mL, lockout time 20 min.

2.6 Surgical procedure

The criteria for radical surgery included the following: the distal and proximal margins of the colon tumor were at least 10 cm according to the CME principle, and the root needed to reach the D3 level; radical surgery for right hemicolectomy needed to be performed up to the left side of the superior mesenteric vein, with the vein skeletonized and the artery ligated at the root of its branch; radical surgery for transverse colon cancer needed to address the root of the middle colic artery; and radical surgery for left hemicolectomy needed to clear the left colic artery and the left branch of the middle colic artery (or the main trunk). Sigmoid colon cancer involved mainly the left colic vessels, sigmoid vessels, and superior rectal artery; the distal bowel should be preserved if it was more than 2 cm above the peritoneal reflection, and the superior rectal artery should be preserved. Radical treatment of rectal cancer was based on the principle of TME, and preservation of the left colic artery could be decided according to the situation; the proximal margin was 5 cm for upper, 2 cm for middle, and 1–2 cm for lower rectal cancer, ensuring a negative distal margin. Laparoscopic pressure was maintained at 11–14 mmHg; the number of ports was not specified; total laparoscopy (laparoscopic anastomosis), laparoscopic-assisted, or hand-assisted laparoscopy were available; anastomosis could be end-to-side, end-to-end (functional end-to-end), or side-to-side. At the end of the procedure, 1 drain was placed in the operative field. Surgical procedure: establishment of pneumoperitoneum, placement of trocars, exploration, positioning, mobilization, resection and anastomosis, reinforcement, closure of mesenteric defects, irrigation, placement of drains, and closure of the incision. Routine postoperative management included oxygen, cardiac monitoring, fluid replacement, and electrolytes (potassium chloride 4–6 g/day, sodium chloride 4.5 g/day); the dressing was changed every other day, and the drainage tube was removed after abdominal ultrasound was performed approximately 1–3 days postoperatively if drainage was minimal.

2.7 Nutrition interventions

(i) Preoperative oral CHOs level combined with postoperative EEN group (group A): patients were required to undergo NRS 2002 ≥ 3 nutritional risk screening for enrollment, 800 mL of oral CHOs (Oral CHOs nutritional solution contains 12.5 g of CHOs per 100 mL, comprising 80% maltodextrin and 20% crystalline sugar.) and fasting on the evening of the preoperative day, and 400 mL of oral CHOs (5 mL/kg) 2 h before the preoperative day. Enteral nutrition was given in the early postoperative period, and the specific enteral nutrition program was as follows: ① The day after surgery, patients should consume 20 mL of oral CHOs 6 h post-surgery until optimal tolerance is reached. Subsequently, the consumption of 50–100 mL of oral CHOs at three-hour intervals is recommended in order to achieve optimal recovery (total volume: 400 mL). ② On the 1st postoperative day, based on the patient’s tolerance, it is recommended to administer oral nutritional supplements (ONS) every 2 ~ 3 h (target total: 400–500 kcal) (Per 100 g, ONS provides 413.96 kcal of energy, with nutritional composition including: protein 15 g, fat 6.7 g, carbohydrates 72.3 g, sodium 300 mg, vitamin A 500 μg RE, vitamin D 1.2 μg, vitamin E 7.60 mg α-TE, vitamin B1 0.90 mg, vitamin B2 1.2 mg, vitamin B6 1.50 mg, vitamin B12 3.00 μg, vitamin C 100.0 mg, niacinamide 15.00 mg, folic acid 425 μg DFE, pantothenic acid 2.20 mg, calcium 80 mg, zinc 7.00 mg, taurine 110 mg). ONS every 2 ~ 3 h on the 1st day after surgery, depending on the patient’s tolerance. ③ Postoperative day 2: ONS every 2–3 h as tolerated by the patient. ONS targets a total of 750 kcal; ④ Postoperative day 3: ONS every 2–3 h as tolerated by the patient. ONS targets a total of 1,000 kcal, with the nutritionist following up and recording the other dietary energy/protein intake. ⑤ Postoperative day 4: ONS every 2–3 h according to the patient’s tolerance. ONS targets a total of 1,250 kcal, and nutritionist’s follow-up and record the energy/protein intake of other diets. ⑥ Postoperative days 5–7: adjust to semiliquid and gradually transition to soft food (target energy between 25–30 kcal/kg-d and protein between 1.0–1.2 g/kg-d).

(ii) Preoperative oral CHOs group (group B): Patients were screened for nutritional risk to ensure an NRS-2002 score ≥ 3. After enrollment, the patients were given 800 mL of oral CHOs on the evening before surgery and 400 mL of oral CHOs (5 mL/kg) 2 h before surgery. On the postoperative day, patients were given 20 mL of oral CHOs 6 h after surgery and 50–100 mL of oral CHOs every 3 h, depending on the patient’s tolerance (400 mL of oral CHOs in total). A liquid diet should be started 24 h after surgery under the guidance of the dietician and then transitioned from a liquid diet to a semiliquid diet or a liquid diet.

(iii) Conventional control group (Group C): Patients who are screened for nutritional risk and who meet the NRS-2002 criteria of ≥3 are included in this group. Patients follow the routine perioperative management of gastrointestinal surgery, and bowel preparation is carried out by adopting a semiliquid diet–fluid diet–fasting and rehydration before surgery. Patients were required to fast for 8 h before surgery, and enema cleansing was performed the night before surgery to ensure the smooth progress of the surgery. After postoperative evacuation, a liquid diet was started, and then a transition from a liquid diet to a semiliquid diet was made.

2.8 Data collection and outcomes

(i) General characterization: the following demographic and clinical data were obtained at admission: sex, age, height, weight, and past medical history. (ii) Laboratory test indicators: white blood cell count (WBC), red blood cell count (RBC), hemoglobin (HGB), platelet (PLT), total bilirubin (TBIL), alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total protein (TP), albumin (ALB), prealbumin (pALB), C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and T lymphocyte subsets. (iii) Postoperative complications: pulmonary infections, abdominal infections, surgical incision infections, intestinal obstruction, anastomotic fistulae, and other complications. (iv) Postoperative recovery: time to first postoperative exhaust and defecation, total length of hospitalization, and postoperative length of stay.

2.9 Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as counts with percentages, and numerical variables are presented as the means with standard deviations (SDs). Differences between groups were analyzed via Pearson’s chi-square test (χ2) or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate for categorical variables; a t test was used for numerical variables. Statistical tests with a two-tailed p-value ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. The data were analyzed via IBM® SPSS® Statistics 23.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, United States).

3 Results

3.1 Baseline characteristics of the subjects

As summarized in Table 1, 315 subjects (103 in group A, 102 in group B, and 110 in group C) were analyzed in this study. There were no significant differences in age, sex, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), or comorbid underlying disease (e.g., hypertension, diabetes mellitus) related parameters at baseline (p > 0.05).

3.2 Preoperative immune status

As shown in Table 2, the immune status of the three groups of patients was further analyzed before surgery. Preoperative laboratory tests revealed no significant differences in immune-related indicators, including WBC, HGB, PLT, ALT, AST, TBIL, DBIL, TP, pALB, ALB, CRP, and IL-6; the percentage of T lymphocytes; the percentage of T helper/induced lymphocytes; the percentage of T suppressor cells; and the percentage of CD4+/CD8+ cells, among the three groups of patients (p > 0.05). These findings suggested that the three groups were comparable to each other.

3.3 Postoperative nutrition-related serum biomarkers

The nutrition-related serum biomarkers related to the postoperative period in groups A, B and C are summarized in Table 3. TP has a shorter half-life and is less affected by acute stress, providing a more stable reflection of nutritional support efficacy. Therefore, we evaluated postoperative total protein levels in three groups of patients (18). Within 3 days after surgery, there was no significant difference in TP levels among groups A, B and C (p > 0.05), but at the one-week postoperative period, the TP levels of group A were significantly greater than those of groups B and C (p < 0.05). At either time point, there was no statistically significant difference in pALB or ALB among the three groups postoperatively (p > 0.05).

3.4 Comparison of postoperative hepatic and renal function recovery among the three groups of patients

Table 4 shows the postoperative liver and renal function indicators in groups A, B, and C. The results revealed no significant difference in ALT, AST, TBIL, DBIL, BUN or Cr among patients at 1, 3, and 7 days after surgery in among the preoperative oral CHOs combined with postoperative EEN group or the preoperative oral CHOs group or the conventional control group (p > 0.05).

3.5 Postoperative inflammation indicators

Postoperative inflammatory and immune-related indicators are summarized in Table 5. The WBC, HGB and CRP levels of all patients were not significantly different among the three groups (p > 0.05). However, the decrease in the IL-6 indicator in group A was greater than that in groups B and C after the seventh postoperative day (p < 0.05). The percentage of T lymphocytes as a percentage of lymphocytes was much greater in group A than in groups B and C starting on the third postoperative day (p < 0.05), but there were no significant changes in the proportion of T-assisted/induced lymphocytes, the proportion of T-suppressed lymphocytes, or the proportion of CD4+/CD8+ lymphocytes (p > 0.05).

3.6 Postoperative intestinal functional status

The results revealed that the time to first defecation and exhaust was significantly earlier in group A than in groups B and C (p < 0.05) (Table 6).

3.7 Postoperative intestinal functional status

Table 7 summarizes the postoperative complications, which mainly included lung infection, surgical incision infection, anastomotic fistula, abdominal infection, pulmonary embolism, and celiac leakage. The number of patients with all kinds of complications was small, and there was no significant difference between patients in groups A (0.078%), B (0.059%), and C (0.09%).

Furthermore, further analysis of the total length of hospital stays and postoperative length of stay in Groups A, B, and C revealed that there was no difference in the total number of days of hospitalization among the three groups, but the postoperative length of stay of patients in Group A (8.69 ± 2.13) was less than that in Groups B (11.64 ± 4.16) and C (11.68 ± 5.47) (p < 0.05).

3.8 Association between TP, IL-6, and T lymphocyte percentages and time to first exhaust or defecation

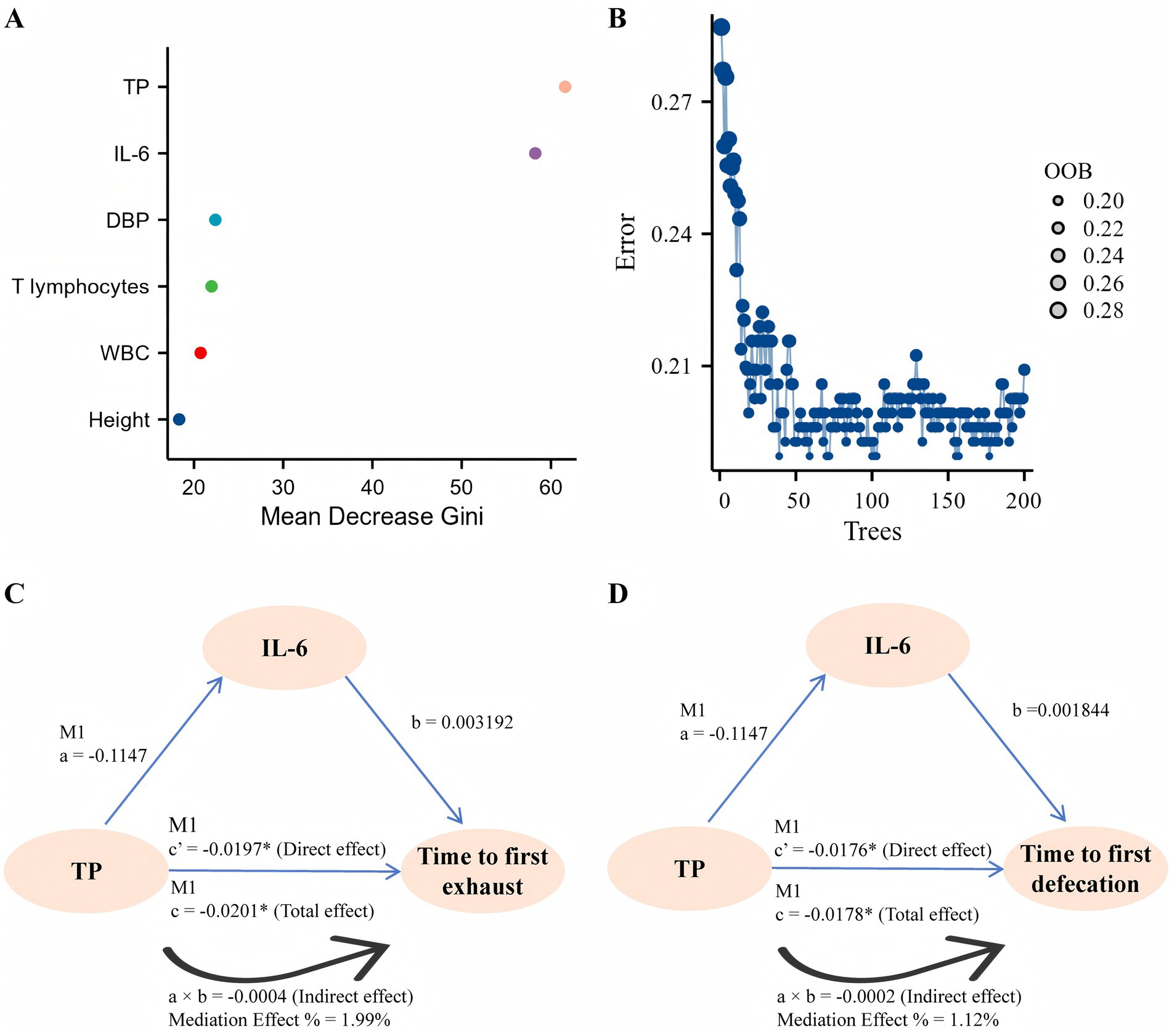

At baseline, the time to first defecation/exhaust was negatively associated with TP, T lymphocytes, and DBP but positively associated with IL-6, WBC, and height (Table 8). Random forest analysis of TP, IL-6, T lymphocytes, WBC, DBP, and height revealed that the predictor TP was the most important, followed by IL-6, and the out-of-bag (OOB) error rate was low, suggesting good predictive accuracy of the model (Figures 2A,B). Interestingly, further mediation effects analyses revealed the direct association of TP on postoperative day 7 with first defecation (total effect: −0.0201, direct effect: −0.0197)/time to defecation (total effect: −0.0178, direct effect: −0.0176), which was not observed in Groups B and C; moreover, the mediating effect of IL-6 was excluded (Table 9 and Figures 2C,D). The details of the testing procedures for the mediated effects model are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 2. Correlation analysis. (A) The effect of each variable on the heterogeneity of observations at each node of the classification tree was calculated, with larger values indicating greater importance of the variable. (B) The number of decision trees is 200, and the OOB is visualized. (C,D) A graphic example of the mediation effect.

3.9 Total protein status prediction time to first exhaust/defecation

To predict the time to first exhaust/defecation, hierarchical linear regression analysis was performed (Table 10). Hierarchical linear regression models revealed that TP combined with IL-6, WBC count, height, DBP, and T lymphocytes explained 29.7% of the time to first exhaust values and 30.7% of the time to defecate values.

Table 10. Hierarchical regression analysis of first exhaust/defecation as the dependent variable (n = 315).

4 Discussion

The present data demonstrated that on postoperative day seven, patients in the group with preoperative oral CHO combined with postoperative ENN (Group A) had significantly greater TP levels and a faster reduction in the level of the inflammatory indicator IL-6 than did those in the preoperative oral CHO group (Group B) and the conventional control group (Group C). Additionally, patients in Group A had a shorter time to first postoperative exhaust/defecation and shorter postoperative hospitalization than did those in Groups B and C. Importantly, TP levels combined with IL-6, WBC, height, DBP, and T lymphocytes could be predictors of the time to first exhaust/defecation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the effects of preoperative oral CHO combined with postoperative ENN on the perioperative recovery of CRC patients. These findings could provide a novel nutritional strategy for CRC patients in the perioperative period and accelerate their postoperative recovery.

Patients with CRC are usually asked to abstain from food and drink for 1 day prior to surgery and to take laxatives and perform cleansing enemas to reduce possible intraoperative complications (e.g., anesthetic aspiration, anastomotic fistula, and incisional infection) (19). However, prolonged dietary abstinence depletes hepatic glycogen reserves and increases the risk of causing insulin resistance (20). Consequently, preoperative oral CHO nutritional regimens are routinely used to prevent or ameliorate postoperative insulin resistance, hyperkalemia, and inflammatory responses in patients with CRC (21). Increasing evidence suggests that postoperative ENN also promotes postoperative bowel motility and increases TP and transferrin levels in patients with gastrointestinal tumors (22). Although, in this study, no differences were observed between preoperative oral CHO and conventional controls, we found that preoperative oral CHO combined with postoperative ENN significantly elevated patients’ postoperative TP levels compared with those in the conventional control and preoperative oral CHO groups. TP levels are critical to patients’ postoperative recovery (23). Clinical studies have shown that, compared with fasting patients, patients in the EEN group had significantly greater total protein levels on both the third and seventh postoperative days and had shorter periods of postoperative fever and flatus (24). Multiple meta-analyses have also demonstrated that patients with high total serum protein levels have a shorter recovery time from postoperative bowel function and fewer complications than patients with low total protein levels do (25–27). The findings of this study suggested that a strategy integrating preoperative oral carbohydrate administration with postoperative ENN effectively enhanced postoperative total protein and albumin levels. Although albumin and TP serve as key indicators reflecting acute inflammation and stress, maintaining and elevating their levels is clinically regarded as a positive signal of effective nutritional support and alleviated metabolic stress, and is associated with improved clinical outcomes (28–30). Consequently, it can be hypothesized that the intervention may have contributed to the recovery of these indicators by concurrently alleviating surgical stress and providing timely nutritional support.

Our study also revealed a significant decrease in IL-6 levels in the preoperative oral CHO combined with postoperative ENN group compared with the preoperative oral CHO group and the conventional control group. This finding is consistent with the results of recent RCTs for patients undergoing surgery for esophageal (31) and gastric cancer (32). Numerous clinical studies have shown that ENN exerts immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects. A study of postoperative ENN intervention in patients with gastric cancer revealed that the serum levels of IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) were significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group, resulting in a lower degree of inflammation (33). Similar intervention outcomes were observed in patients with colitis, with EEN reducing serum IL-6, interleukin 1 (IL-1), and TNF-α levels and attenuating the state of intestinal oxidative stress (34). Moreover, we found that patients in the preoperative oral CHO combined with postoperative ENN group had a greater percentage of T lymphocytes to lymphocytes than did those in the preoperative oral CHO group and the conventional control group. These findings indicate that preoperative oral CHO combined with postoperative ENN may promote the recovery of postoperative immune function in CRC patients.

The recovery of bowel function in colon cancer patients after surgery is mainly indicated by the time to exhaust and defecation (35, 36). Numerous RCTs have demonstrated that postoperative ENN promotes intestinal peristalsis, prevents intestinal mucosal injury, and facilitates the absorption of nutritional preparations. A study of a postoperative ENN intervention that included patients with pancreatic, esophageal, and gastric cancers revealed that the ENN intervention upregulated patients’ serum TP levels and that patients in the ENN group had shorter times to first exhaust and defecation than did those in the control group (37). Similarly, in this study, patients in the preoperative oral CHO combined with postoperative ENN group had a shorter time to first exhaust/defecation than did those in the preoperative oral CHO group and the conventional control group.

Mechanistic studies support the concept that protein supplementation or increasing total protein levels could shorten the time to first postoperative exhaustion/defecation by inhibiting inflammatory markers [CRP (38), IL-6 (39), and IL-10 (40)] or signaling pathways [PI3K/AKT (41) and NF-κB (42)]. A prospective cohort study revealed that TP levels were negatively associated with length of hospitalization and time to first defecation (43). Additionally, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α levels are positively associated with the time to first exhaust/defecation (44). In our study, patients in the preoperative oral CHO combined with postoperative ENN group had less postoperative hospitalization than did those in the preoperative oral CHO group and the conventional control group. Furthermore, total protein, T lymphocytes and DBP were negatively associated with the time to first exhaust/defecation, whereas IL-6, height and WBC count were positively associated with the time to first exhaust/defecation. Random forest analysis revealed that TP was the most important predictor, followed by IL-6. Random forest analysis revealed that TP was the most important predictor, followed by IL-6. Lactoferrin supplementation has been shown to exert an anti-inflammatory effect by reducing circulating IL-6 and TNF-α levels (45). However, in our study, mediated effect analysis revealed that TP on postoperative day 7 was directly associated with the time to first exhaust/defecation, excluding the mediating effect of IL-6. Therefore, on the basis of the above studies, we concluded that preoperative oral CHO combined with postoperative ENN increased TP levels in postoperative patients and that TP was associated with the time to first exhaust/defecation.

Recently, a machine learning-based prediction model revealed that time to first postoperative feeding, age, probiotics, and oral antibiotics for bowel preparation were independent risk factors for time to first defecation in CRC patients (46). A predictive model for hospitalization time after gastric cancer surgery revealed that four clinical characteristics, the neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR) on postoperative day one, the NLR on postoperative day three, the preoperative prognostic nutrient index and the first anal exhaust, were good predictors of hospitalization time (47). Studies on postoperative ENN interventions [intestinal anastomosis in pediatrics (48), radical total gastrectomy for gastric cancer (49), intestinal obstruction (50), etc.] have shown that ENN could contribute to the recovery of postoperative bowel function. However, few studies have delved into multivariate analysis of the time to first postoperative exhaust/defecation for patients with CRC. The present study demonstrated that TP combined with IL-6, WBC, height, DBP and T lymphocytes can be used as predictors of the time to first exhaust/defecation.

In this study, we investigated the value of preoperative oral CHO combined with postoperative ENN in CRC patients. The results of the present study revealed that preoperative oral CHO combined with postoperative ENN among CRC patients could significantly optimized postoperative nutrition-related indicators, strengthen immune function, promote early recovery of intestinal function, and significantly shorten the duration of postoperative hospitalization. It is important to note that this study utilized serum TP and albumin as the primary nutrition-related indicators. It is acknowledged that in circumstances involving stress, such as surgical procedures, the levels of these visceral proteins are considerably impacted by the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. The reduced concentrations observed may be indicative of heightened catabolism and modified capillary permeability, rather than being solely attributable to inadequate nutritional intake (51–53). Consequently, it is recommended that they be regarded more accurately as composite markers of nutritional risk and inflammatory stress. Notwithstanding this limitation, patients in the intervention group exhibited elevated protein levels and enhanced clinical outcomes (e.g., reduced hospitalization durations), providing substantial evidence that our integrated nutritional strategy effectively mitigated metabolic disturbances and catabolic states induced by surgical trauma. It is recommended that future studies incorporate more specific nutritional assessment tools (e.g., body composition analysis, grip strength) in order to provide more comprehensive evidence. Meanwhile, there were several limitations in this study. Firstly, long-term prognostic data were not obtained, and more experimental data are needed to validate whether EEN support impacts patient prognosis. Secondly, potential confounders were not adequately controlled, and some clinical variables (e.g., tumor stage and differences in drug combinations) were not adequately matched, which may affect the interpretation of the results. Moreover, this study did not assess patients’ postoperative quality of life (e.g., physical recovery, psychological status) and focused only on physiologic indicators, which failed to fully reflect the clinical value of the intervention. Therefore, we anticipate that further studies will be conducted to clarify the relationships among these variables.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Deyang People’s Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ZH: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Methodology. YL: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology. QX: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. XY: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. DZ: Writing – review & editing, Project administration. LZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (No. 2025YFHZ0308).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2025.1699541/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Van Roermund, NS, Ijspeert, JEG, and Dekker, E. Developing a strategy for prevention of avoidable Postcolonoscopy colorectal cancers: current and future perspectives. Gastroenterology. (2025) 168:854–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.12.003

2. Dee, EC, Laversanne, M, Bhoo-Pathy, N, Ho, FDV, Feliciano, EJG, Eala, MAB, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality estimates in 2022 in Southeast Asia: a comparative analysis. Lancet Oncol. (2025) 26:516–28. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(25)00017-8

3. Eng, C, Yoshino, T, Ruíz-García, E, Mostafa, N, Cann, CG, O'Brian, B, et al. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. (2024) 404:294–310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00360-X

4. Knudsen, MD, Wang, K, Wang, L, Polychronidis, G, Berstad, P, Hjartåker, A, et al. Colorectal Cancer incidence and mortality after negative colonoscopy screening results. JAMA Oncol. (2025) 11:46–54. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2024.5227

5. Knight, SR, Ghosh, D, Kingsley, PA, Lapitan, MA, Parreno-Sacdalan, MD, Sundar, S, et al.Impact of malnutrition on early outcomes after cancer surgery: an international, multicentre, prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. (2023) 11:e341–9. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(22)00550-2

6. Turan, A, Khanna, AK, Brooker, J, Saha, AK, Clark, CJ, Samant, A, et al. Association between mobilization and composite postoperative complications following major elective surgery. JAMA Surg. (2023) 158:825–30. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2023.1122

7. Ljungqvist, O, de Boer, HD, Balfour, A, Fawcett, WJ, Lobo, DN, Nelson, G, et al. Opportunities and challenges for the next phase of enhanced recovery after surgery: a review. JAMA Surg. (2021) 156:775–84. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0586

8. Zhang, S, He, L, Yu, Y, Yuan, X, Yang, T, Yan, F, et al. Effects of preoperative oral carbohydrates on insulin resistance and postoperative recovery in diabetic patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: a preliminary prospective, single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. (2025), 39:3338–49. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2025.07.036

9. Wang, XH, Wang, ZY, Shan, ZR, Wang, R, and Wang, ZP. Effects of preoperative Oral carbohydrates on recovery after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Perianesth Nurs. (2025) 40:169–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2024.03.007

10. Morgan, E, Arnold, M, Gini, A, Lorenzoni, V, Cabasag, CJ, Laversanne, M, et al. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. (2023) 72:338–44. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327736

11. Schrag, D, Shi, Q, Weiser, MR, Gollub, MJ, Saltz, LB, Musher, BL, et al. Preoperative treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. (2023) 389:322–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2303269

12. Tajan, M, and Vousden, KH. Dietary approaches to Cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. (2020) 37:767–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.04.005

13. Chapman, B, Wong, D, Sinclair, M, Hey, P, Terbah, R, Gow, P, et al. Reversing malnutrition and low muscle strength with targeted enteral feeding in patients awaiting liver transplant: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. (2024) 80:1134–46. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000840

14. Zhao, J, Yuan, F, Song, C, Yin, R, Chang, M, Zhang, W, et al. Safety and efficacy of three enteral feeding strategies in patients with severe stroke in China (OPENS): a multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint trial. Lancet Neurol. (2022) 21:319–28. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00010-2

15. Gao, X, Liu, Y, Zhang, L, Zhou, D, Tian, F, Gao, T, et al. Effect of early vs late supplemental parenteral nutrition in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. (2022) 157:384–93. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.0269

16. Schuetz, P, Fehr, R, Baechli, V, Geiser, M, Deiss, M, Gomes, F, et al. Individualised nutritional support in medical inpatients at nutritional risk: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet. (2019) 393:2312–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32776-4

17. Thompson, A, Fleischmann, KE, Smilowitz, NR, de Las Fuentes, L, Mukherjee, D, Aggarwal, NR, et al. 2024 AHA/ACC/ACS/ASNC/HRS/SCA/SCCT/SCMR/SVM guideline for perioperative cardiovascular management for noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. (2024) 150:e351–442. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001285

18. Cameron, K, Nguyen, AL, Gibson, DJ, Ward, MG, Sparrow, MP, and Gibson, PR. Review article: albumin and its role in inflammatory bowel disease: the old, the new, and the future. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2025) 40:808–20. doi: 10.1111/jgh.16895

19. Gillis, C, Buhler, K, Bresee, L, Carli, F, Gramlich, L, Culos-Reed, N, et al. Effects of nutritional Prehabilitation, with and without exercise, on outcomes of patients who undergo colorectal surgery: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. (2018) 155:391–410.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.012

20. Manoogian, ENC, Wilkinson, MJ, O'Neal, M, Laing, K, Nguyen, J, Van, D, et al. Time-restricted eating in adults with metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. (2024) 177:1462–70. doi: 10.7326/M24-0859

21. Ceresoli, M, Ripamonti, L, Pedrazzani, C, Pellegrino, L, Tamini, N, Totis, M, et al. Determinants of late recovery following elective colorectal surgery. Tech Coloproctol. (2024) 28:132. doi: 10.1007/s10151-024-03004-3

22. Wang, J, Wang, L, Zhao, M, Zuo, X, Zhu, W, Cui, K, et al. Effect of early enteral nutrition support combined with chemotherapy on related complications and immune function of patients after radical gastrectomy. J Healthc Eng. (2022) 2022:1531738. doi: 10.1155/2022/1531738

23. Svane, MS, Bojsen-Møller, KN, Martinussen, C, Dirksen, C, Madsen, JL, Reitelseder, S, et al. Postprandial nutrient handling and gastrointestinal hormone secretion after roux-en-Y gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy. Gastroenterology. (2019) 156:1627–1641.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.262

24. Yang, J, Zhang, X, Li, K, Zhou, Y, Hu, Y, Chen, X, et al. Effects of EN combined with PN enriched with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on immune related indicators and early rehabilitation of patients with gastric cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr. (2022) 41:1163–70. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2022.03.018

25. Bally, MR, Blaser Yildirim, PZ, Bounoure, L, Gloy, VL, Mueller, B, Briel, M, et al. Nutritional support and outcomes in malnourished medical inpatients: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. (2016) 176:43–53. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6587

26. van Zanten, AR, Sztark, F, Kaisers, UX, Zielmann, S, Felbinger, TW, Sablotzki, AR, et al. High-protein enteral nutrition enriched with immune-modulating nutrients vs standard high-protein enteral nutrition and nosocomial infections in the ICU: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2014) 312:514–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7698

27. He, LB, Liu, MY, He, Y, and Guo, AL. Nutritional status efficacy of early nutritional support in gastrointestinal care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg. (2023) 15:953–64. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i5.953

28. Abedi, F, Zarei, B, and Elyasi, S. Albumin: a comprehensive review and practical guideline for clinical use. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. (2024) 80:1151–69. doi: 10.1007/s00228-024-03664-y

29. Li, S, Zhang, J, Zheng, H, Wang, X, Liu, Z, and Sun, T. Prognostic role of serum albumin, Total lymphocyte count, and Mini nutritional assessment on outcomes after geriatric hip fracture surgery: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Arthroplast. (2019) 34:1287–96. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.02.003

30. Possa, LO, Hinkelman, JV, Santos, CAD, Oliveira, CA, Faria, BS, Hermsdorff, HHM, et al. Association of dietary total antioxidant capacity with anthropometric indicators, C-reactive protein, and clinical outcomes in hospitalized oncologic patients. Nutrition. (2021) 90:111359. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2021.111359

31. Pan, YP, Kuo, HC, Lin, JY, Chou, WC, Chang, PH, Ling, HH, et al. Serum cytokines correlate with pretreatment body mass index-adjusted body weight loss grading and cancer progression in patients with stage III esophageal squamous cell carcinoma undergoing neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery. Nutr Cancer. (2024) 76:486–98. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2024.2341461

32. Jin, Z, and Chen, Y. Serum PM20D1 levels are associated with nutritional status and inflammatory factors in gastric cancer patients undergoing early enteral nutrition. Open Med. (2025) 20:20241111. doi: 10.1515/med-2024-1111

33. Li, K, Xu, Y, Hu, Y, Liu, Y, Chen, X, and Zhou, Y. Effect of enteral Immunonutrition on immune, inflammatory markers and nutritional status in gastric Cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy: a randomized double-blinded controlled trial. J Investig Surg. (2020) 33:950–9. doi: 10.1080/08941939.2019.1569736

34. Peter, C, Abukhris, A, Brendel, J, Böhne, C, Bohnhorst, B, and Pirr, S. Growth and duration of inflammation determine short- and Long-term outcome in very-low-birth-weight infants requiring abdominal surgery. Nutrients. (2023) 15:1668. doi: 10.3390/nu15071668

35. Qin, Q, Huang, B, Wu, A, Gao, J, Liu, X, Cao, W, et al. Development and validation of a post-radiotherapy prediction model for bowel dysfunction after rectal Cancer resection. Gastroenterology. (2023) 165:1430–1442.e14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.08.022

36. Wisse, PHA, de Klaver, W, van Wifferen, F, van Maaren-Meijer, FG, van Ingen, HE, Meiqari, L, et al. The multitarget faecal immunochemical test for improving stool-based colorectal cancer screening programmes: a Dutch population-based, paired-design, intervention study. Lancet Oncol. (2024) 25:326–37. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00651-4

37. Deftereos, I, Yeung, JM, Arslan, J, Carter, VM, Isenring, E, and Kiss, N. Adherence to ESPEN guidelines and associations with postoperative outcomes in upper gastrointestinal cancer resection: results from the multi-Centre NOURISH point prevalence study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. (2022) 47:391–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.10.019

38. Tang, G, Pi, F, Qiu, YH, and Wei, ZQ. Postoperative parenteral glutamine supplementation improves the short-term outcomes in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery: a propensity score matching study. Front Nutr. (2023) 10:1040893. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1040893

39. Daskalaki, MG, Axarlis, K, Aspevik, T, Orfanakis, M, Kolliniati, O, Lapi, I, et al. Fish Sidestream-derived protein hydrolysates suppress DSS-induced colitis by modulating intestinal inflammation in mice. Mar Drugs. (2021) 19:312. doi: 10.3390/md19060312

40. Wang, J, Bai, X, Peng, C, Yu, Z, Li, B, Zhang, W, et al. Fermented milk containing Lactobacillus casei Zhang and Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis V9 alleviated constipation symptoms through regulation of intestinal microbiota, inflammation, and metabolic pathways. J Dairy Sci. (2020) 103:11025–38. doi: 10.3168/jds.2020-18639

41. Du, Y, Li, D, Chen, J, Li, YH, Zhang, Z, Hidayat, K, et al. Lactoferrin improves hepatic insulin resistance and pancreatic dysfunction in high-fat diet and streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Nutr Res. (2022) 103:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2022.03.011

42. Li, CW, Yu, K, Shyh-Chang, N, Li, GX, Jiang, LJ, Yu, SL, et al. Circulating factors associated with sarcopenia during ageing and after intensive lifestyle intervention. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. (2019) 10:586–600. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12417

43. Zhao, X, Wang, Y, Yang, Y, Pan, Y, Liu, J, and Ge, S. Association between preoperative nutritional status, inflammation, and intestinal permeability in elderly patients undergoing gastrectomy: a prospective cohort study. J Gastrointest Oncol. (2022) 13:997–1006. doi: 10.21037/jgo-22-367

44. Wei, XY, Huo, HC, Li, X, Sun, SL, and Zhang, J. Relationship between postoperative rehabilitation style, gastrointestinal function, and inflammatory factor levels in children with intussusception. World J Gastrointest Surg. (2024) 16:2640–8. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i8.2640

45. Prokopidis, K, Mazidi, M, Sankaranarayanan, R, Tajik, B, McArdle, A, and Isanejad, M. Effects of whey and soy protein supplementation on inflammatory cytokines in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. (2023) 129:759–70. doi: 10.1017/S0007114522001787

46. Yang, S, Zhao, H, An, Y, Guo, F, Zhang, H, Gao, Z, et al. Machine learning-based prediction models affecting the recovery of postoperative bowel function for patients undergoing colorectal surgeries. BMC Surg. (2024) 24:143. doi: 10.1186/s12893-024-02437-9

47. Zhang, X, Wei, X, Lin, S, Sun, W, Wang, G, Cheng, W, et al. Predictive model for prolonged hospital stay risk after gastric cancer surgery. Front Oncol. (2024) 14:1382878. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1382878

48. Drossard, S, and Schuffert, L. Early enteral nutrition (EEN) following intestinal anastomosis in pediatric patients – what's new? Innov Surg Sci. (2024) 9:167–73. doi: 10.1515/iss-2024-0017

49. Cai, B, Xu, G, Zhang, Z, Tao, K, and Wang, W. Early Oral feeding is safe and comfortable in patients with gastric Cancer undergoing radical Total gastrectomy. Nutr Cancer. (2025) 77:79–85. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2024.2396150

50. Wang, ZZ, Liu, ZK, Ma, WX, Wu, YH, and Duan, XL. Prediction of the risk of severe small bowel obstruction and effects of Houpu Paiqi mixture in patients undergoing surgery for small bowel obstruction. BMC Surg. (2024) 24:63. doi: 10.1186/s12893-024-02343-0

51. Cheng, E, Shi, Q, Shields, AF, Nixon, AB, Shergill, AP, Ma, C, et al. Association of Inflammatory Biomarkers with Survival among Patients with Stage III Colon Cancer. JAMA Oncol. (2023) 9:404–13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.6911

52. Dark, P, Hossain, A, McAuley, DF, Brealey, D, Carlson, G, Clayton, JC, et al. Biomarker-guided antibiotic duration for hospitalized patients with suspected sepsis: the ADAPT-sepsis randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2025) 333:682–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.26458

Keywords: CRC, immune function, enteral nutrition, CHOs, postoperative recovery

Citation: He Z, Liu Y, Xu Q, Yang X, Zhou D and Zhang L (2025) Effect of preoperative oral carbohydrate combined with postoperative early enteral nutrition on the perioperative rehabilitation of patients with colorectal cancer: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Front. Nutr. 12:1699541. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1699541

Edited by:

Susmita Barman, University of Nebraska Medical Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Bangli Hu, Guangxi Medical University Cancer Hospital, ChinaKatherine Garcia Malpartida, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia, Spain

Copyright © 2025 He, Liu, Xu, Yang, Zhou and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lili Zhang, aHlyQGFsdS5zdWRhLmVkdS5jbg==

Zeyin He

Zeyin He Yong Liu

Yong Liu Qiyin Xu4

Qiyin Xu4 Lili Zhang

Lili Zhang