Abstract

Recent developments of band topology have revealed a variety of higher-order topological insulators (HOTIs). These HOTIs are characterized by a variety of different topological invariants, making them different at a fundamental level. However, despite such differences, the fact that they all sustain higher-order topological boundary modes poses a challenge to phenomenologically tell them apart. This work presents experimental measurements of the coupling effects of topological corner modes (TCMs) existing in two different types of two-dimensional acoustic HOTIs. Although both HOTIs have a similar four-site square lattice, the difference in magnetic flux per unit cell dictates that they belong to different types of topologically nontrivial phases—one lattice possesses quantized dipole moments, but the other is characterized by quantized quadrupole moment. A link between the topological invariants and the response line shape of the coupled TCMs is theoretically established and experimentally confirmed. Our results offer a pathway to distinguish HOTIs experimentally.

Introduction

The recent development of topological band theory has revealed the existence of higher-order topological insulators (HOTIs) [1–5]. An important hallmark of such HOTIs is the existence of -dimensional topological boundary modes, where is the dimensionality of the system, and is an integer. Thanks to the development of classical wave crystals, HOTIs have not only been observed in solid-state electronics but also in photonic crystals [6–12], sonic crystals [13–19], and elastic-wave crystals [20, 21].

For HOTIs with two real-space dimensions, the higher-order topological boundary modes are zero-dimensional modes localized at the corners of the lattice. These topological corner modes (TCMs) can be protected by a variety of topological invariants, such as quantized dipole moments [9, 10, 22], quantized quadrupole moments [1, 23, 24], combinations of first Chern numbers [17], etc. However, although their topological protection can be revealed by theoretical computation of the topological invariants, it is difficult to distinguish them from an observational point of view.

A previous theoretical study has analyzed the finite-size effect on neighboring TCMs in a 2D HOTI [25]. By comparing two different types of topologically nontrivial square-lattice HOTIs—a topological dipole insulator (TDI) wherein the dipole moments are quantized and a topological quadrupole insulator (TQI) with a quantized quadrupole moment, it was shown that the TCMs’ spectral responses split, and the line shapes are associated with the topological characteristics of the HOTI. As such, the spectral responses of the coupled TCMs are an observable effect, by which the underlying topological nature can be phenomenologically revealed.

Theoretical Construct

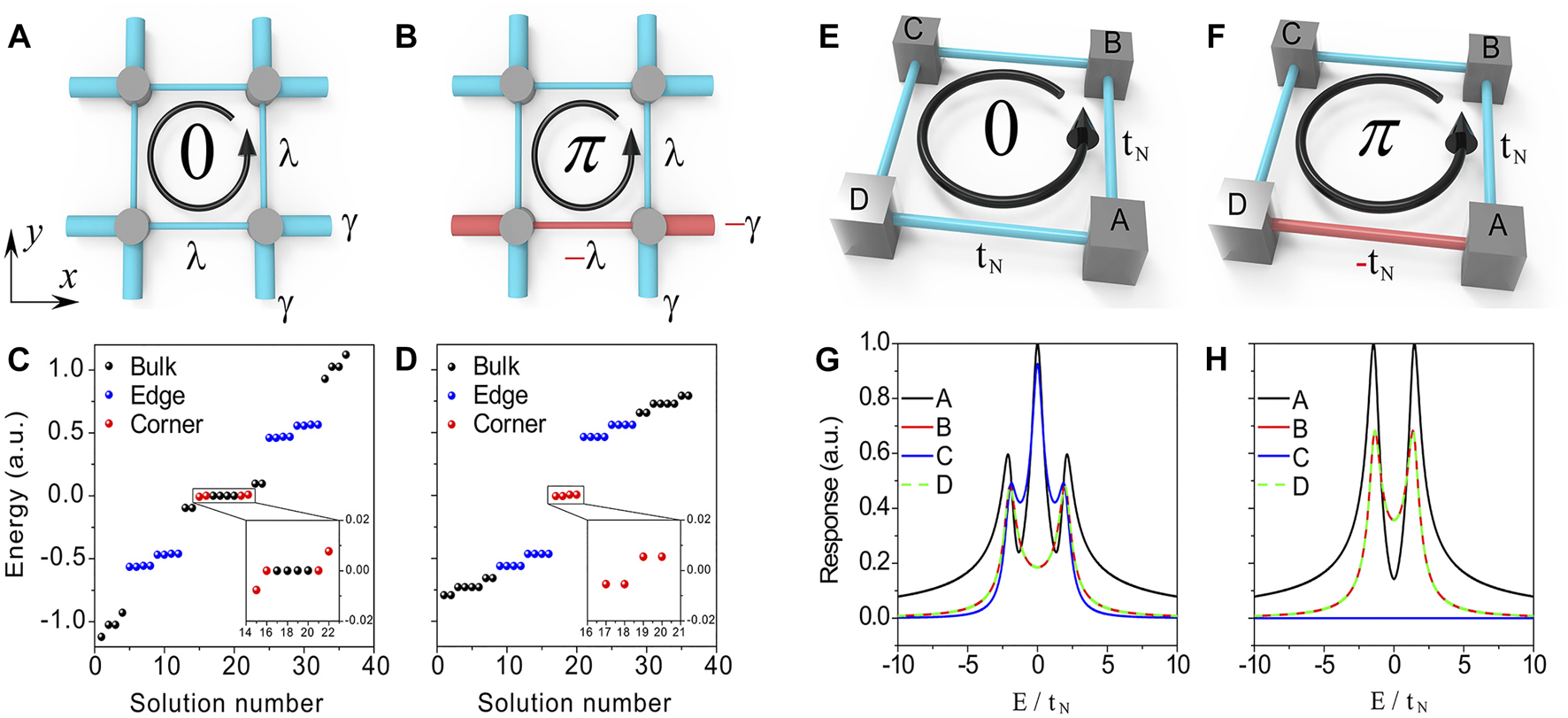

For the sake of completeness, we first briefly summarize the important theoretical background. A complete theoretical analysis can be found in Ref. [25]. Here, the TDIs and TQIs are both based on the extensions of the 1D Su-Schrieffer-Heeger (SSH) model, and we show the unit-cell structures for the 2D TDI and TQI in Figure 1A,B, respectively. The strengths of the staggered nearest couplings along x and y directions are denoted as intracell (thin tubes) and intercell (thick tubes) hopping. For the TDI, all hopping coefficients are on the same sign so that the net magnetic flux in a plaquette is zero. For the TQI, the hopping coefficients can take opposite signs, as indicated by the red tubes in Figure 1B. The resultant net magnetic flux is . When , both systems are in the topologically nontrivial phase and have topological edge modes and TCMs, as shown in Figures 1C,D.

FIGURE 1

The unit cell of the TDI (A) and TQI (B), where the thin and thick tubes denote the intracell ( or ) and intercell ( or ) hopping, respectively. (C–D) The bulk (black points), edge (blue points), and corner (red points) modes of a lattice of the TDI (C) and TQI (D), where and . (E–F) Schematic drawings of a corner-mode Hamiltonian for the TCMs of the TDI (E) and TQI (F). The gray boxes represent the TCMs. The blue and red tubes respectively represent positive and negative edge hopping. (G–H) The corner responses with excitation at corner A. Here, .

For a TDI lattice, the corresponding Hamiltonian can be written aswithwhere is a identity matrix, denotes Kronecker product, and and denote states of the left and right atoms, respectively, in the mth unit cell for a 1D SSH chain model. For a TQI, the Hamiltonian iswhere is a identity matrix, and is the z-component of the spin-1/2 Pauli matrices.

We plot the eigenvalues of Eq. 1, 3 in Figures 1C,D, respectively. The parameters are set as , , and . The bulk, edge, and corner modes are marked by black, blue, and red points, respectively. In both cases, four TCMs are found. As seen in the insets, the four TCMs are not degenerate. This is because, in a finite-sized lattice, the edges can provide coupling to neighboring TCMs [25]. For the TDI, the TCMs split into three clusters, with the two modes in the middle being degenerate. The two degenerate TCMs are still pinned at zero energy because of chiral symmetry. For the TQI, it can be proved that all eigenstates, including bulk modes and TCMs, are at least doubly degenerate [25, 26]. Therefore, the TCMs are divided into two doubly degenerate clusters, which are symmetric about zero energy. The finite-sized coupling effect can be captured by a four-state effective Hamiltonian with the four TCMs as the basis, which readsfor the TDI, andfor the TQI. Here, , where () denotes the strength of the eigenstate () of . Since , is vanishing for large . These models are schematically shown in Figures 1E,F. Note that similar to their respective unit cells, there is a magnetic flux of 0 and in the TDI and TQI-corner models, respectively. From Eqs. 4, 5, we can use a Green’s function to describe the spectral responses of the coupled TCMswhere is the eigenvalue and is the eigenvector, and accounts for any dissipative effect in the system. When excited at corner , the response at the corner will be . When excited at corner A, the responses at each corner are shown in Figure 1G for the TDI, and Figure 1H for TQI. It is seen that the spectral responses are different for the TDI and TQI. Particularly, the TDI responses can split into three peaks when measured at corners A and C, and the TQI response vanishes when measured at C. Such distinctions are an important manifestation of the quantized magnetic fluxes in the systems, which can be used as experimental evidence to distinguish the two classes of HOTIs.

Experimental Results

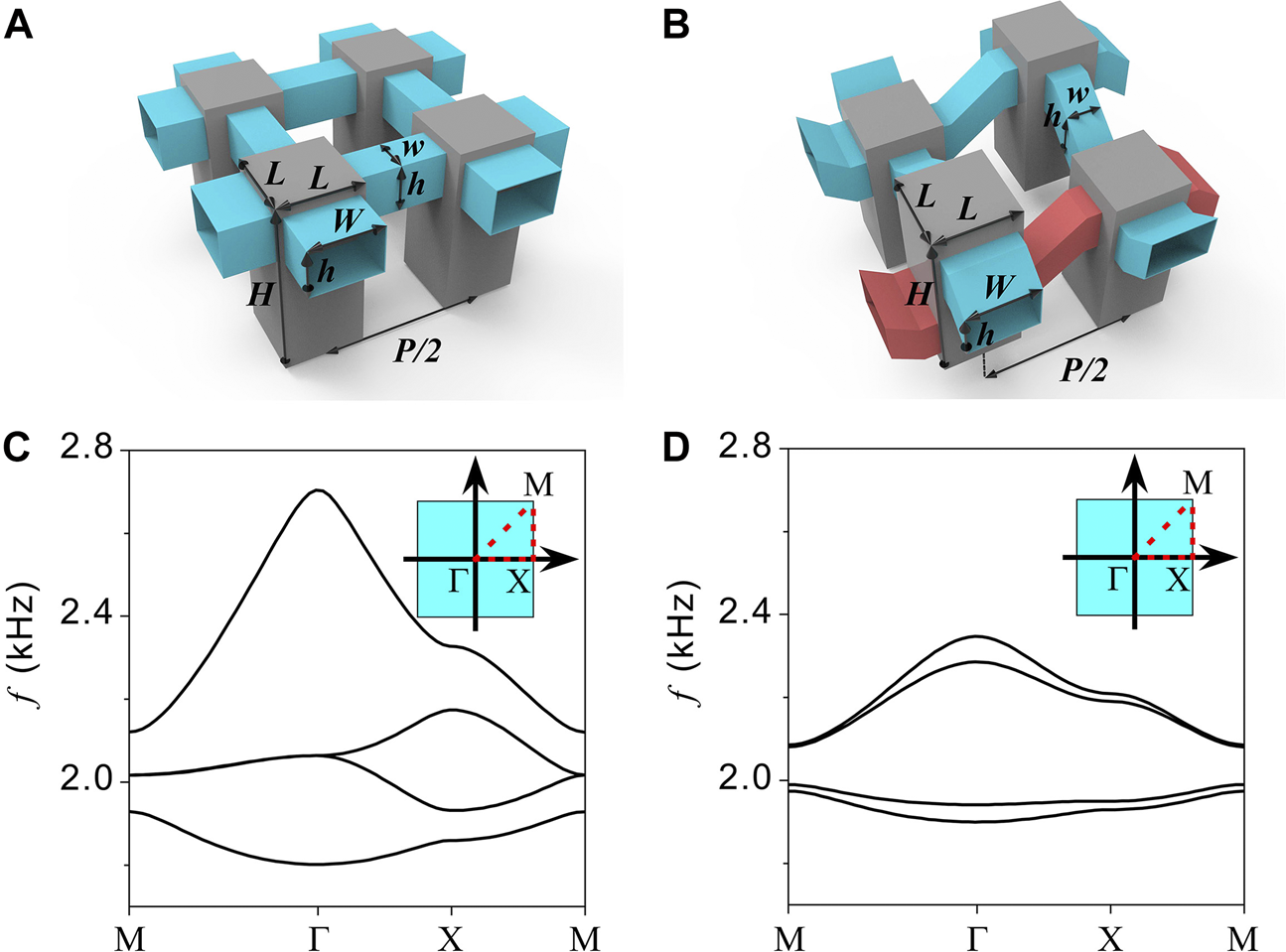

We next present the designs of phononic crystals to realize both the TDI and TQI. The unit cells are shown in Figures 2A,B, respectively. The gray blocks denote the acoustic cavities, whose first-order resonance fulfills the role of the on-site orbital. The cavities have a height of and a width of , and they are coupled by tubes that facilitate the hopping terms. For the TDI, the widths of the intracell and intercell coupling tubes are and , respectively. They are connected at a vertical position with the height being the same . The lattice constant is . The design of the TQI is different because we need to realize hopping terms with a negative sign. To achieve this, we connect the top of one cavity to the bottom of the designated neighbor using a bent tube (red in Figure 2B). The blue tubes which facilitate positive hopping are also bent in the same manner so that all tubes have the same length. The positions of the cavities are staggeredly elevated so that the lengths of the intracell or intercell coupling tubes are the same. We use COMSOL Multiphysics to compute the band structures of the two types of unit cells. The medium inside the cavity and coupling tubes is air with a mass density of and a sound speed of , where the imaginary part denotes losses. The results are respectively shown in Figures 2C,D, where four bands are seen for both cases.

FIGURE 2

(A–B) The designs of phononic crystal unit cells of the TDI (A) and TQI (B). (C–D) The band structures of the TDI (C) and TQI (D). The inset in each plot denotes the first Brillouin zone.

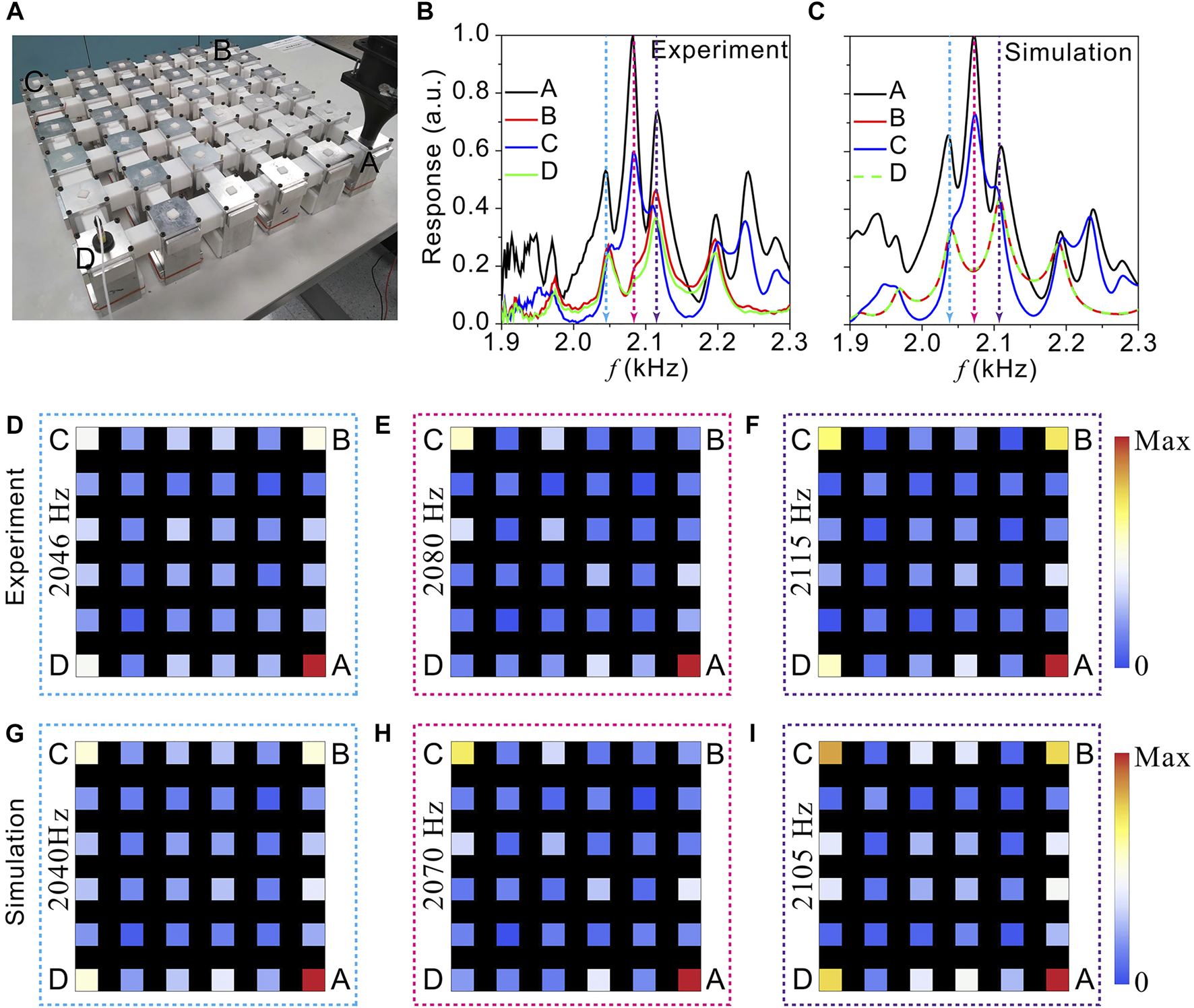

Based on these two designs, we have fabricated the phononic crystals. The cavities are machined from aluminum alloy and the coupling tubes are 3D printed using photosensitive resin. The photographs of the TDI and TQI configurations are shown in Figure 3A, 4A, respectively. Both lattices are in size, containing a total of 36 cavities. At the top of the cavities, we drilled a small hole (covered with a small white plug), where a sound signal is sent or a probe can detect the acoustic signal inside the cavity. We excite corner A with a loudspeaker, as shown in Figure 3A, 4A. Then, we used a microphone to obtain the spectral response field in every cavity. For the TDI lattice, the responses measured at corners A, B, C, D are shown in Figure 3B. In the predicted frequency regime, i. e., 2,050–2,150 Hz, a three-peak response line shape is seen for both the spectra measured at corners A and C. And two-peak line shape is seen for corners B and D. These results agree well with the theoretical prediction by the tight-binding model (Figures 1C,G). To confirm that these responses are due to the coupled TCMs, we have measured the pressure responses in all cavities at the frequencies of the response peaks. The results are shown in Figures 3D–F. Clearly, the spatial distributions are strongly localized at the corners, which is a signature characteristic of TCMs. We have further verified the responses in numerical simulations. The results in Figure 3C,G–I also show excellent agreement with the experiment.

FIGURE 3

(A) A photograph showing the fabricated TDI phononic crystal. (B–C) Measured (B) and simulated (C) corner responses. (D–F) Measured responses at the frequencies corner-mode resonant peaks: (D) 2046Hz, (E) 2080Hz, (F) 2115 Hz. (G–I) Simulated responses at the frequencies corner-mode resonant peaks: (G) 2040Hz, (H) 2070Hz, (I) 2105 Hz.

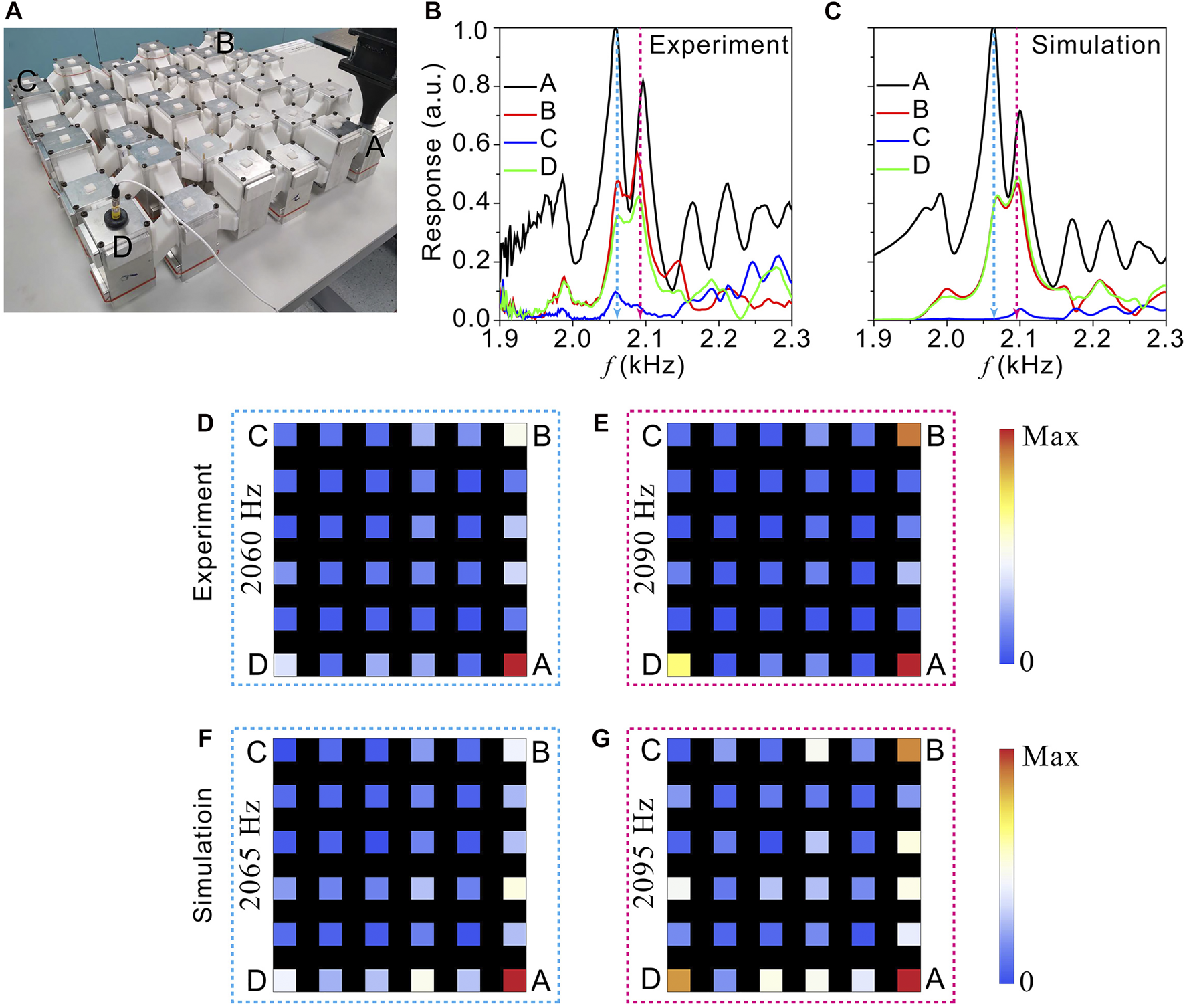

FIGURE 4

(A) A photograph showing the fabricated TQI phononic crystal. (B–C) Measured (B) and simulated (C) corner responses. (D–E) Measured responses at the frequencies corner-mode resonant peaks: (D) 2060Hz, (E) 2090 Hz. (F–G) Simulated responses at the frequencies corner-mode resonant peaks: (F) 2065Hz, (G) 2095 Hz.

Similar experiments were performed for the TQI lattice. In Figure 4B, two response peaks are identified in the bulk gap (2,000–2,150 Hz) for the spectra measured at corners A, B, D. Also, the response at corner C is significantly weaker. These observations again align with the prediction (Figures 1D,H) and simulations (Figure 4C). We further confirm in the measured (Figures 4D,E) and simulated (Figures 4F,G) spatial maps that the response peaks are indeed due to the TCMs.

Conclusion

In summary, we have experimentally observed the coupling effects of TCMs in two different types of acoustic HOTIs. The measured line shapes of the corner responses agree excellently with a previous theoretical study, which confirms that the topological properties of the HOTIs can indeed influence the coupling effects of TCMs. Therefore, the corner responses can serve as an experimental hallmark to separate HOTIs of different classes. It is interesting to further the study by investigating the coupling effects in other types of HOTIs such as a Kagome lattice [4], honeycomb lattice [20], etc. On the other hand, the coupled higher-order topological modes can be a useful starting point for higher-order non-Hermitian physics [27, 28]. They may also find applications such as topological wave and light confinement [13, 29] and topological lasing [30, 31].

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

XL and SW performed numerical simulations and designed the experiment. XL, SW, GZ carried out the measurements. All authors analyzed and discussed the results. XL and GM wrote the manuscript with inputs from others. GM initiated and supervised the research.

Funding

This work was supported by Hong Kong Research Grants Council (12302420, 12300419, 22302718, and C6013-18G), National Natural Science Foundation of China (11922416, 11802256), and Hong Kong Baptist University (RC-SGT2/18-19/SCI/006).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Weiwei Zhu for the discussions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

BenalcazarWABernevigBAHughesTL. Quantized Electric Multipole Insulators. Science (2017) 357:61–6. 10.1126/science.aah6442

2.

BenalcazarWABernevigBAHughesTL. Electric Multipole Moments, Topological Multipole Moment Pumping, and Chiral Hinge States in Crystalline Insulators. Phys Rev B (2017) 96:245115. 10.1103/physrevb.96.245115

3.

SchindlerFCookAMVergnioryMGWangZParkinSSPBernevigBAet alHigher-order Topological Insulators. Sci Adv (2018) 4:eaat0346. 10.1126/sciadv.aat0346

4.

EzawaM. Higher-Order Topological Insulators and Semimetals on the Breathing Kagome and Pyrochlore Lattices. Phys Rev Lett (2018) 120:026801. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.026801

5.

XieBWangHXZhangXZhanPJiangJHLuMet alHigher-order Band Topology. Nat Rev Phys (2021) 1-13. 10.1038/s42254-021-00323-4

6.

PetersonCWBenalcazarWAHughesTLBahlG. A Quantized Microwave Quadrupole Insulator with Topologically Protected Corner States. Nature (2018) 555:346–50. 10.1038/nature25777

7.

MittalSOrreVVZhuGGorlachMAPoddubnyAHafeziM. Photonic Quadrupole Topological Phases. Nat Photon (2019) 13:692–6. 10.1038/s41566-019-0452-0

8.

NohJBenalcazarWAHuangSCollinsMJChenKPHughesTLet alTopological protection of Photonic Mid-gap Defect Modes. Nat Photon (2018) 12:408–15. 10.1038/s41566-018-0179-3

9.

ChenX-DDengW-MShiF-LZhaoF-LChenMDongJ-W. Direct Observation of Corner States in Second-Order Topological Photonic Crystal Slabs. Phys Rev Lett (2019) 122:233902. 10.1103/physrevlett.122.233902

10.

XieB-YSuG-XWangH-FSuHShenX-PZhanPet alVisualization of Higher-Order Topological Insulating Phases in Two-Dimensional Dielectric Photonic Crystals. Phys Rev Lett (2019) 122:233903. 10.1103/physrevlett.122.233903

11.

El HassanAKunstFKMoritzAAndlerGBergholtzEJBourennaneM. Corner States of Light in Photonic Waveguides. Nat Photon (2019) 13:697–700. 10.1038/s41566-019-0519-y

12.

ZhangLYangYLinZKQinPChenQGaoFet alHigher-Order Topological States in Surface-Wave Photonic Crystals. Adv Sci (Weinh) (2020) 7:1902724. 10.1002/advs.201902724

13.

XuCChenZ-GZhangGMaGWuY. Multi-Dimensional Wave Steering with Higher-Order Topological Phononic Crystal. Sci Bull (2021) 66:1740–5. 10.1016/j.scib.2021.05.013

14.

XueHYangYGaoFChongYZhangB. Acoustic Higher-Order Topological Insulator on a Kagome Lattice. Nat Mater (2019) 18:108–12. 10.1038/s41563-018-0251-x

15.

NiXWeinerMAlùAKhanikaevAB. Observation of Higher-Order Topological Acoustic States Protected by Generalized Chiral Symmetry. Nat Mater (2019) 18:113–20. 10.1038/s41563-018-0252-9

16.

ZhangXWangH-XLinZ-KTianYXieBLuM-Het alSecond-order Topology and Multidimensional Topological Transitions in Sonic Crystals. Nat Phys (2019) 15:582–8. 10.1038/s41567-019-0472-1

17.

ChenZGZhuWTanYWangLMaG. Acoustic Realization of a Four-Dimensional Higher-Order Chern Insulator and Boundary-Modes Engineering. Phys Rev X (2021) 11(1):011016. 10.1103/physrevx.11.011016

18.

ChenZGWangLZhangGMaG. Chiral Symmetry Breaking of Tight-Binding Models in Coupled Acoustic-Cavity Systems. Phys Rev Appl (2020) 14(2):024023. 10.1103/physrevapplied.14.024023

19.

Serra-GarciaMPeriVSüsstrunkRBilalORLarsenTVillanuevaLGet alObservation of a Phononic Quadrupole Topological Insulator. Nature (2018) 555:342–5. 10.1038/nature25156

20.

FanHXiaBTongLZhengSYuD. Elastic Higher-Order Topological Insulator with Topologically Protected Corner States. Phys Rev Lett (2019) 122(20):204301. 10.1103/physrevlett.122.204301

21.

WuQChenHLiXHuangG. In-plane Second-Order Topologically Protected States in Elastic Kagome Lattices. Phys Rev Appl (2020) 14(1):014084. 10.1103/physrevapplied.14.014084

22.

XieB-YWangH-FWangH-XZhuX-YJiangJ-HLuM-Het alSecond-order Photonic Topological Insulator with Corner States. Phys Rev B (2018) 98(20):205147. 10.1103/physrevb.98.205147

23.

QiYQiuCXiaoMHeHKeMLiuZ. Acoustic Realization of Quadrupole Topological Insulators. Phys Rev Lett (2020) 124(20):206601. 10.1103/physrevlett.124.206601

24.

XueHGeYSunH-XWangQJiaDGuanY-Jet alObservation of an Acoustic Octupole Topological Insulator. Nat Commun (2020) 11:2442. 10.1038/s41467-020-16350-1

25.

ZhuWMaG. Distinguishing Topological Corner Modes in Higher-Order Topological Insulators of Finite Size. Phys Rev B (2020) 101(R):161301. 10.1103/physrevb.101.161301

26.

ZhaoYXHuangY-XYangSA. Z2 -projective Translational Symmetry Protected Topological Phases. Phys Rev B (2020) 102:161117. 10.1103/physrevb.102.161117

27.

DingKMaGXiaoMZhangZQChanCT. Emergence, Coalescence, and Topological Properties of Multiple Exceptional Points and Their Experimental Realization. Phys Rev X (2016) 6:021007. 10.1103/physrevx.6.021007

28.

TangWJiangXDingKXiaoY-XZhangZ-QChanCTet alExceptional Nexus with a Hybrid Topological Invariant. Science (2020) 370:1077–80. 10.1126/science.abd8872

29.

OtaYLiuFKatsumiRWatanabeKWakabayashiKArakawaYet alPhotonic crystal Nanocavity Based on a Topological Corner State. Optica (2019) 6:786. 10.1364/optica.6.000786

30.

KimH-RHwangM-SSmirnovaDJeongK-YKivsharYParkH-G. Multipolar Lasing Modes from Topological Corner States. Nat Commun (2020) 11:5758. 10.1038/s41467-020-19609-9

31.

HanCKangMJeonH. Lasing at Multidimensional Topological States in a Two-Dimensional Photonic Crystal Structure. ACS Photon (2020) 7:2027–36. 10.1021/acsphotonics.0c00357

Summary

Keywords

topological corner modes, higher-order topological insulators, phononic crystals, tightbinding model, green’s function

Citation

Li X, Wu S, Zhang G, Cai W, Ng J and Ma G (2021) Measurement of Corner-Mode Coupling in Acoustic Higher-Order Topological Insulators. Front. Phys. 9:770589. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2021.770589

Received

04 September 2021

Accepted

07 October 2021

Published

26 October 2021

Volume

9 - 2021

Edited by

Yiqi Zhang, Xi’an Jiaotong University, China

Reviewed by

Haoran Xue, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Yihao Yang, Zhejiang University, China

Daohong Song, School of Physics, Nankai University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2021 Li, Wu, Zhang, Cai, Ng and Ma.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guancong Ma, phgcma@hkbu.edu.hk

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work

† Present address: Shiqiao Wu, School of Physical Science and Technology, Soochow University, Suzhou, China

This article was submitted to Optics and Photonics, a section of the journal Frontiers in Physics

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.