Abstract

We report on the spin Hall effect in epitaxial Pt films with well-defined crystalline (200), (220), and (111) orientations and smooth surfaces. The magnitude of the spin Hall effect has been determined by spin–torque ferromagnetic resonance measurements on epitaxial Pt/Py heterostructures. We observed a 54% enhancement of the charge-to-spin conversion efficiency of the epitaxial Pt when currents are applied along the in-plane direction. Temperature-dependent harmonic measurements on epitaxial Pt/Co/Ni heterostructures compared to a polycrystalline Pt/Co/Ni suggest the extrinsic mechanism underlying spin Hall effect in epitaxial Pt. Our work contributes to the development of energy-efficient spintronic devices by engineering the crystalline anisotropy of non-magnetic metals.

Introduction

Over the past decade, significant research efforts have been devoted to investigating magnetization manipulation in the heavy metal (HM)/ferromagnetic material (FM) heterostructure via spin–orbit torque (SOT) [1–6]. By engineering the bulk spin Hall effect (SHE) in HMs [7, 8] and interfacial Rashba–Edelstein effect (REE) [9–11], enhanced SOT values can be achieved that have the potential for developing novel energy-efficient magnetic memory [12], logic [13], and neuromorphic computing devices [14]. Conventional SOT studies mainly focus on textured HMs such as Pt [15], Au [16, 17], -W [18, 19], and -Ta [20], and transition metal alloys, for example, Cu-Ta [21] and Fe-Pt [22]. More recently, epitaxial materials with tunable crystalline anisotropy and well-defined orientations have been recognized as promising candidates for SOT studies [23–30]. Fruitful research highlights crystalline-dependent anisotropic properties, for example, crystalline orientation–dependent spin relaxation mechanism in Pt (111) [31] and enhanced SHE in epitaxial metal [Ta (111) [32]], magnetic alloys [Mn3Ge (0002) [33]], and topological insulators [BiSb (012) [34], Bi2Se3 [35]]. Particularly, the facet orientation–dependent SOT in epitaxial antiferromagnetic IrMn3 is contributed by orientation-dependent intrinsic SHE [36]. Likewise, crystallographic-dependent SOT could present in epitaxial HMs when spin current is generated in different crystalline orientations.

In this letter, we detail the growth of epitaxial Pt thin films and Pt/FM heterostructures with (200), (220), and (111) crystalline orientations. In epitaxial films, symmetries of the magnetic interactions will reflect the underlying crystal and interface symmetries where the three orientations studied have four-fold, two-fold, and three-fold surface symmetries, respectively. The symmetries should be reflected in fundamental properties such as interfacial anisotropy (both in-plane and out-of-plane) [37] and Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction (DMI) [38, 39]. For low-symmetry systems such as Pt (220) with C2v, the strength of the DMI may vary in magnitude or sign along different directions [40–44]. Such anisotropic DMI and anisotropy can stabilize novel phases such as antiskyrmions [41].

In this study, we focus on the SHE with the current flowing in various symmetry directions in Pt. By quantitatively evaluating the SOT along in-plane crystalline orientations via spin torque–FMR (ST-FMR) measurements, isotropic and anisotropic SHE have been observed and the role of the crystal symmetry enumerated. Moreover, by performing temperature-dependent harmonic measurements, we further reveal the intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms underlying the SHE in epitaxial and polycrystalline Pt films. By combining directional-dependent SOT and anisotropic magnetic properties, we anticipate energy-efficient magnetization manipulation in novel spin structures.

Sample Growth and Characterization

Epitaxial Pt films were grown onto single-crystalline MgO (200), MgO (220), and Al2O3 substrates by DC magnetron sputtering. The vacuum chamber had a base pressure of 8 10−8 Torr and a growth Ar pressure of 2.7 mTorr. Pt (200) was grown on Cr (200)-buffered MgO (200) substrates. The 5-nm-thick Cr (200) seed layers were deposited at 450°C to initiate the epitaxy, followed by Pt (200) deposition at 200°C. Pt (220) and Pt (111) films were grown directly on MgO (220) and Al2O3 substrates, respectively, at 300°C. The growth procedures have been optimized for both epitaxy and desirable smooth surface conditions. After the Pt growth, the substrate was cooled, and subsequential FM layers were grown in situ at room temperature to minimize the interfacial mixing effect and magnetic dead layers. All samples were capped with a 2-nm-thick amorphous Al2O3 layer to prevent surface oxidation. Following the aforementioned procedure, we prepared a series of epitaxial Pt (10)/Py (8) (Py, Ni81Fe19) samples for ST-FMR measurements and both epitaxial Pt (111) (5)/Co(0.8)/Ni(1) and polycrystalline Pt (15)/Co(0.8)/Ni(1) samples with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy for harmonic measurements (thickness in nanometer throughout the text unless otherwise stated). Note that the choice of Py as the FM layer is motivated by its wide application as an efficient spin detector [15, 45–50] and the usage of Co/Ni is due to its spontaneous perpendicular magnetic anisotropy, a prerequisite for harmonic measurements [51, 52].

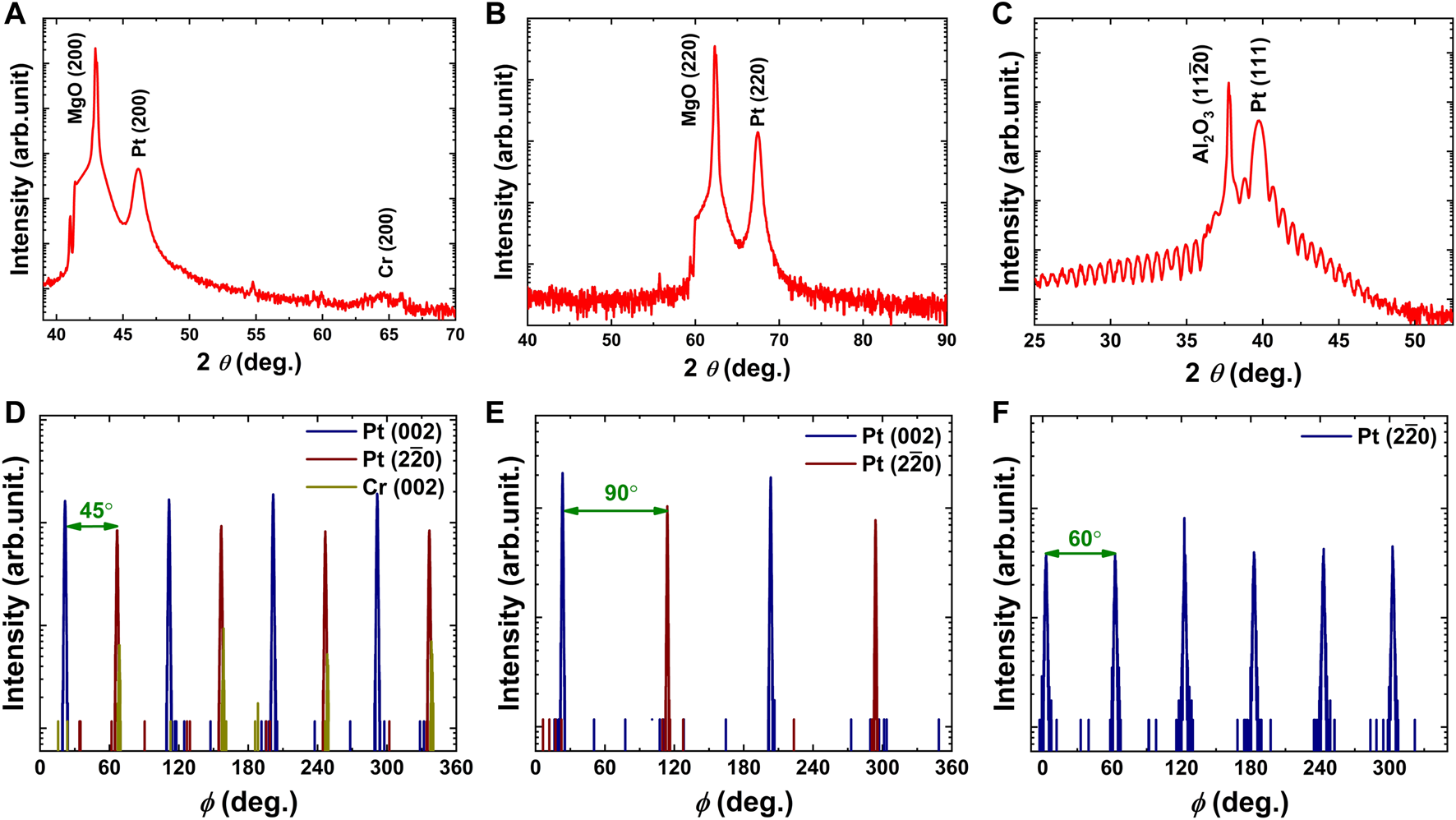

The crystallographic properties of as-deposited Pt films were evaluated by X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements. The out-of-plane symmetric -2 scans of Pt (200), Pt (220), and Pt (111) films are presented in Figures 1A–C, demonstrating the epitaxy growth along the substrates or the seed layers. The clear Laue oscillations of the Pt (111) peak indicate excellent lattice matching and a sharp Al2O3/Pt interface. Figures 1D–F show the in-plane XRD scan, confirming the characteristic four-fold symmetry of Pt (200) film and two-fold symmetry of Pt (220) film. Note that the Pt (111) sample exhibits a six-fold symmetry, which is attributed to crystal twinning. The relative orientation between the crystalline axis of the Pt thin films and substrates has been verified by both scans and semi-sphere pole figures, as shown in Supplementary Figure S2–S4. Specifically, for the Pt (200) sample, the in-plane Pt aligns with MgO and is 45° to the in-plane Cr and Pt . For the Pt (220) sample, the in-plane Pt //MgO and Pt // . For the Pt (111) sample, the in-plane Pt is perpendicular to the in-plane Al2O3. By fitting the low-angle X-ray reflectivity (XRR) data, the surface roughness of the deposited Pt (111), Pt (220), and Pt (200) films are found to be 0.085, 0.25, and 0.37 nm (Supplementary Figure S1A–C), respectively. The smooth surface condition of the prepared epitaxial Pt thin films contributes to a sharp HM/FM interface, which is the key to reduce inhomogeneous linewidth broadening [53] and improved spin current conductance [54]. We highlight that some previous studies of Pt (220) films observed significant surface roughness [55] which we have ameliorated.

FIGURE 1

Out-of-plane XRD scan of epitaxial Pt films: (A) MgO (200)/Cr (200)/Pt (200). (B) MgO (220)/Pt (220). (C) Al2O3/Pt (111). (D)–(F) In-plane scans showing epitaxial growth and the four-fold, two-fold, and six-fold symmetry of Pt (200), Pt (220), and Pt (111), respectively.

Experimental Results and Discussion

ST-FMR Measurements

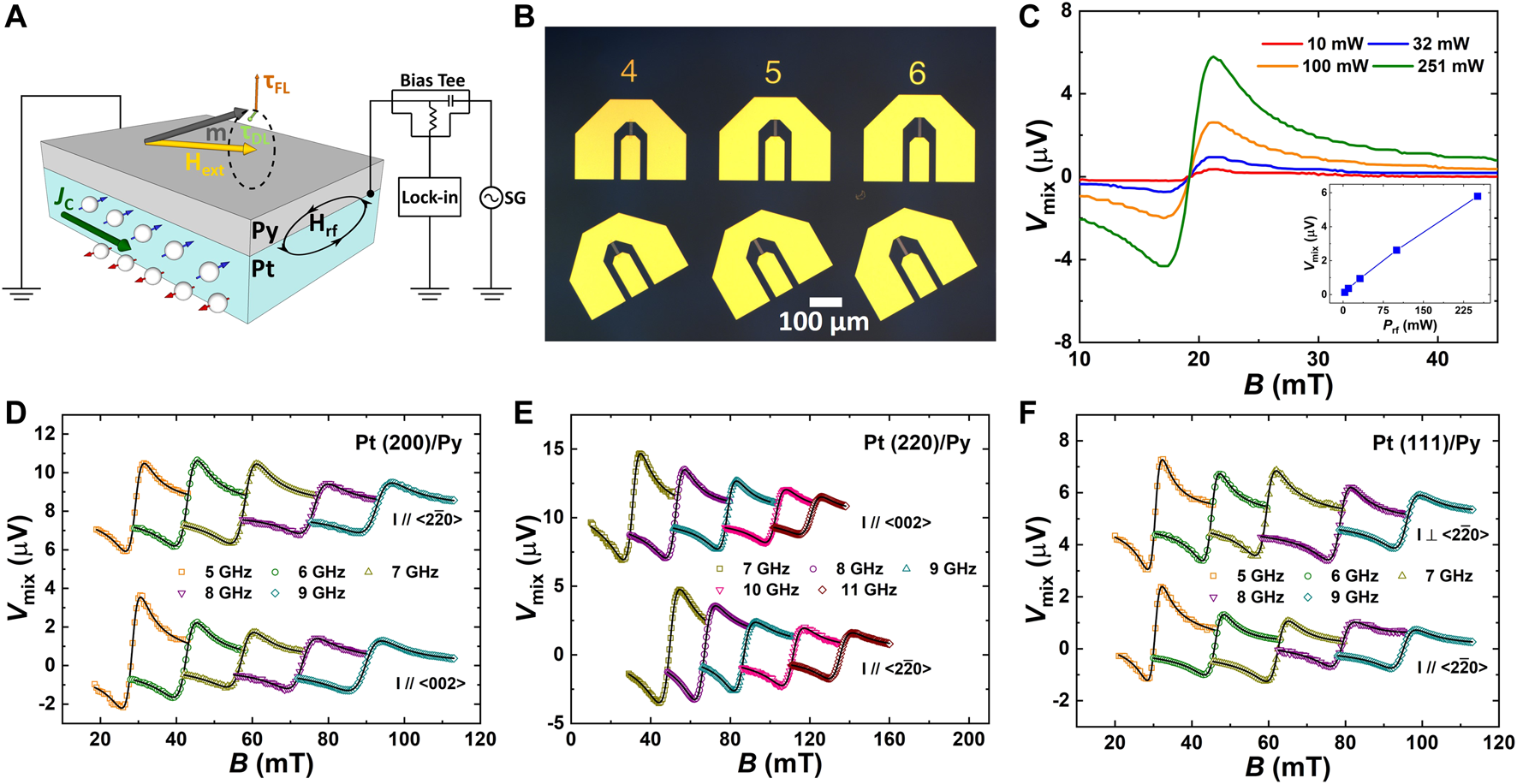

We first introduce our ST-FMR measurement technique to characterize the charge-to-spin conversion efficiency of the deposited epitaxial Pt films. Figure 2A illustrates the schematic of our ST-FMR measurement setup. In the measurements, a microwave current is applied along specific in-plane crystalline directions in the Pt layer determined by lithography. Due to the combination of the SHE and spin diffusion effects, oscillating spin currents can be generated in the Pt films, transported across the Pt/Py interface, and absorbed by the adjacent Py layer. The out-of-plane Oersted field torque and the in-plane SOT will drive precessional motion of the Py magnetization around the direction of the in-plane effective magnetic field, leading to an oscillatory change in resistance arising from the anisotropic magnetoresistance (AMR) of Py. The largest precession amplitude is found to occur at the ferromagnetic resonance (FMR) frequency of the Py layer. Mixing the oscillatory resistance and the applied RF current will give rise to a DC voltage, which can be detected by a lock-in amplifier with a modulated RF current.

FIGURE 2

(A) Schematic diagram of ST-FMR measurement setup. (B) Optical microscope image of patterned Pt/Py CPWs with ground–signal–ground electrodes. (C) ST-FMR spectra measured at different RF power. Insert: the ST-FMR signal Vmix with a linear dependence on the input microwave power. (D)–(F) The measured ST-FMR spectra (open dots) with fitting curves (solid lines) on Pt (200)/Py, Pt (220)/Py, and Pt (111)/Py, respectively. The curves are offset for visual clarity.

Figure 2B shows the optical image of the photolithographically patterned microstrips with varied aspect ratios for impendence matching and two different orientations of the current. Coplanar wave guide (CPW) channels are patterned in certain angles to align with the crystalline orientations in the prepared Pt/Py films. Ti (6)/Au (200) pads are fabricated for symmetric ground–signal–ground contact electrodes by a standard sputtering and lift-off technique. The RF current is applied to the CPW channels via wire bonding from transmission lines to the ground–signal–ground electrodes. The in-plane external magnetic field is oriented 45° relative to the CPWs to improve the magnitude of the measured ST-FMR signals [46]. Measurement of the induced DC voltages takes advantage of a bias tee which separates the input RF microwave currents and the ST-FMR signals. All the ST-FMR measurements presented in this work were performed at room temperature. The measured DC voltage follows a linear dependence on the applied microwave power, as shown in Figure 2C, suggesting the marginal role of the Joule heating effect in our measurements.

The ST-FMR technique provides a quantitative measurement of the of the prepared epitaxial Pt films. The lineshape of the measured DC voltage can be expressed as a combination of symmetric Lorentzian and antisymmetric Lorentzian [56–58]:where the parameter is the amplitude of symmetric Lorentzian arising from the spin Hall–induced anti-damping SOT exerted on Py, is the amplitude of antisymmetric Lorentzian resulting from the sum of field-like SOT and Oersted field torque, is the resonance field, and is the full-width-half-maximum (FWHM) linewidth of the Py layer. The ratio between and is directly proportional to , which can be further expressed as follows [15]:where is the permeability in vacuum; is the reduced Planck constant, is elementary charge; is the saturated magnetization of Py, which has been characterized to be 698 kA/m via vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) measurements (Supplementary Figure S5); is the effective magnetization of Py which can be obtained from fitting the frequency-dependent resonance field by the Kittel formula [59]; and and represent the thickness of Py and Pt layers, respectively.

Figures 2D–F show the experimental ST-FMR resonance spectrum measured on Pt (200)/Py, Pt (220)/Py, and Pt (111)/Py samples with microwave frequencies varying from 5 to 11 GHz. Due to the larger saturation field of Py, measurements of the Pt (220)/Py sample are mainly focused in the high-frequency regime. For Pt (220)/Py, the shift of the resonance fields when the RF current applied along different crystalline directions is attributed to the in-plane anisotropy of Py induced by Pt (220) with low symmetry (C2v), while in high-symmetry systems (C4v and C3v) of Pt (200) and Pt (111) samples, nearly isotropic Py magnetic properties make the resonance fields independent of the in-plane direction. The experimental results (open dots) were well-fitted with Eq. 1 (solid lines). We note that follows a constant value over the whole frequency range of our measurements. It is worth mentioning that the lineshape method based on Eq. 2 only provides an estimation of the upper limit of due to the resonance-driven spin pumping effect from Py to Pt as reported in a previous work [46, 49].

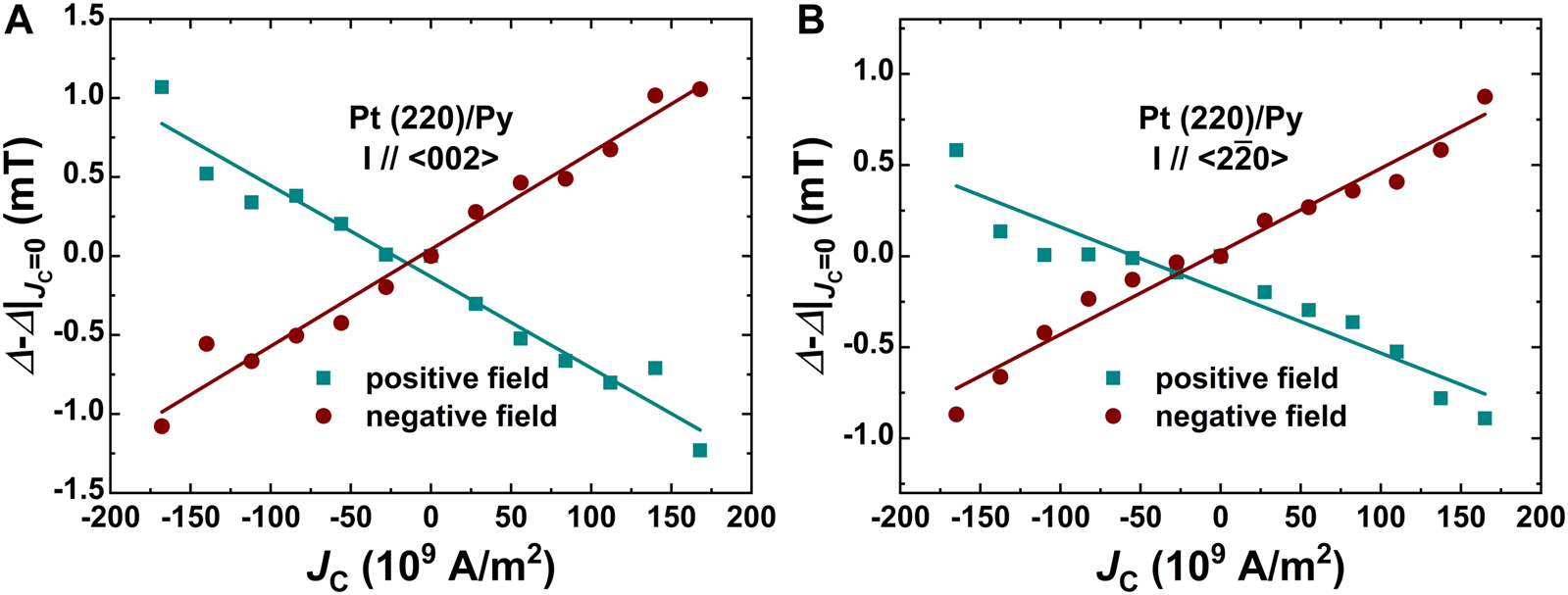

To independently verify the results obtained from the lineshape method, we also performed linewidth modulation measurements. By applying a DC current to the patterned Pt/Py microstrip, a static anti-damping torque effectively modulates the Gilbert damping of Py, resulting in a systematic current-dependent variation of the linewidth of the obtained ST-FMR spectra. Based on the spin-transfer torque (STT) model [56], the injected DC spin currents effectively increase (decrease) the damping of the Py layer when the spin polarization is parallel (antiparallel) to the Py magnetization, leading to a broadened (reduced) ST-FMR linewidth [15, 60]. Furthermore, reversing the polarity of the external magnetic field that saturates Py magnetization will also lead to the sign change of the observed signals, as illustrated in Figure 3. Quantitatively, can be obtained from the slope of the DC-dependent resonance linewidth of Py as follows [15, 23, 49]:where is the angle between DC current and external magnetic field, is the FMR frequency, is the gyromagnetic ratio, and is the electric current density in the epitaxial Pt layer. Figure 3 presents the results of modulated linewidth as a function of in Pt (220)/Py(8) sample. By four-probe measurement, the longitudinal resistivity of Pt (220) and the 8-nm-thick Py films along individual crystalline orientations has been characterized independently on control samples (Supplementary Figure S6). Thus, can be quantitatively calculated from the portion of current distribution based on the parallel resistor model. As shown in Figures 3A,B, when the electric current is along , the slope is approximately 54% larger than that when current is along . We note that such distinct crystalline orientation–dependent SHE is absent in higher symmetry Pt (200)/Py and Pt (111)/Py samples.

FIGURE 3

Variation of FMR linewidth as a function of applied DC current at a microwave frequency f = 7 GHz for current along (A) and (B) on Pt (220)/Py, respectively. Solid lines are linear fits to the data.

To summarize our ST-FMR results, Table 1 shows the obtained of Pt along different crystalline orientations of the prepared epitaxial Pt films. In general, a larger value of is observed in the sample with higher . In the high-symmetry systems such as square Pt (200) and hexagonal Pt (111) lattice with C4v and C3v symmetry, the difference between along different in-plane crystalline orientations is less than 5%, within the experimental error. Notably, the isotropic yields isotropic in Pt (220) and Pt (111) samples. Isotropic has been observed in other high-symmetry epitaxial materials, such as SrIrO3 (0001) [25] and Fe (001)/Pt [61]. In contrast, in the low-symmetry system (C2v) of Pt (220), is 11% larger than . The obtained value of along direction is significantly larger than that along direction via both lineshape and linewidth methods. We remark that the obtained anisotropic on Pt (220) agrees with the results recently reported [30], where enhancement of was also observed in Pt when current was along direction.

TABLE 1

| Sample | Current direction | () | at 300 K (Lineshape method) | at 300 K (Linewidth method) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt (200) (10)/Py(8) | 17.3 | 0.055 | — | |

| 16.6 | 0.053 | — | ||

| Pt (220) (10)/Py(8) | 15.3 | 0.050 | 0.028 | |

| 13.8 | 0.039 | 0.018 | ||

| Pt (111) (10)/Py(8) | 11.7 | 0.034 | — | |

| 11.8 | 0.032 | — |

Crystalline orientation–dependent longitudinal resistivities and charge-to-spin conversion efficiencies of epitaxial Pt films and Pt/FM structures.

As the thickness of the measured Pt films is greater than the spin diffusion length , the measured is mainly contributed by bulk SHE, bulk REE, and interfacial REE [62]. The bulk SHE consists of intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms, in which orientational-dependent anisotropic can be contributed by the intrinsic SOC and intrinsic SHE. On the other hand, different extrinsic scattering events can give rise to anisotropic SHE; however, extrinsic impurity scattering is minor in the undoped, highly crystalline epitaxial Pt. Therefore, we believe that the anisotropic bulk SHE in Pt is mainly driven by the orientation-dependent intrinsic mechanism. This is supported by the fact that since broken space inversion symmetry is absent in Pt crystals, the bulk REE contribution can be ruled out [63]. Last, the interfacial REE is expected to be anisotropic in the Pt (220)/Py interface. Simon et al. demonstrated, for reduced symmetry surface such as Au (110), the anisotropic REE dominates due to the mixing of the surface state with the bulk state [64]. Conclusively, the anisotropy in both intrinsic SHE and interfacial REE could result in anisotropic .

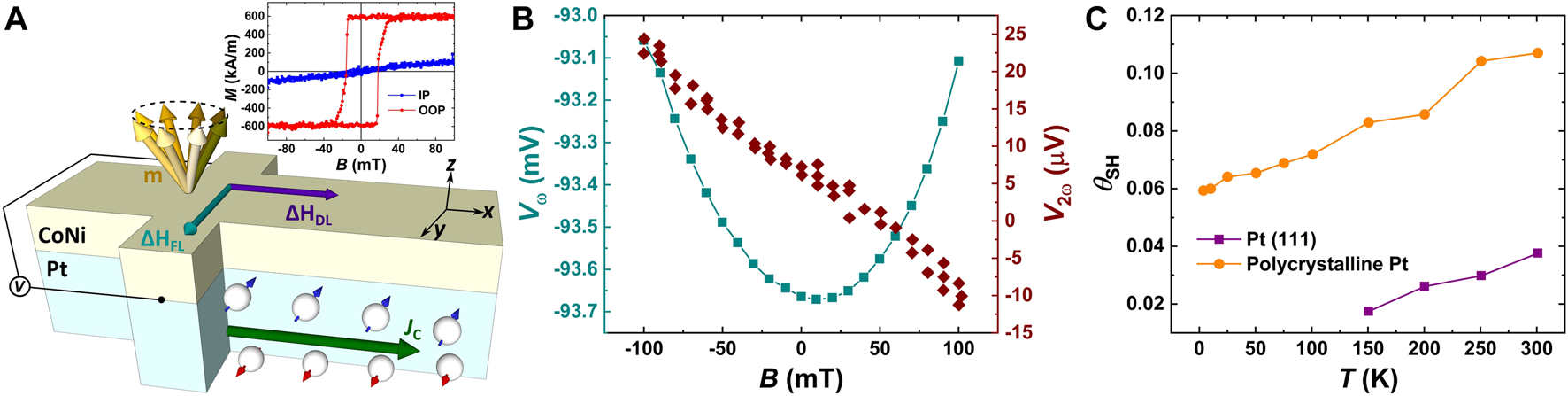

Temperature-Dependent Harmonic Measurements

To further understand the resistivity-dependent SHE of the epitaxial Pt films, we performed temperature-dependent harmonic measurements on patterned Pt/Co(0.8)/Ni(1) Hall devices, as illustrated in Figure 4A. Figure 4B shows the characteristic first and second harmonic Hall results measured in the prepared device. For bulk SHE, when a charge current flows through the Pt along the x-axis, spin current is generated along the z-axis with spin polarization along the y-axis. A damping-like SOT and a field-like SOT produced by the generated spin currents are exerted on the magnetization of Co/Ni [1, 4]. When reaches an equilibrium position, the effects of these two SOTs can be described equivalently as the damping-like effective field () and field-like effective field (), respectively [1, 4]. By applying a 5-mA AC current at a frequency of 161 Hz, the generated causes an oscillation of around the equilibrium position. By sweeping an in-plane external magnetic field along the current direction, the field dependence of the first harmonic signal Vω and the 90° out-of-phased second-harmonic signal V2ω can be measured. The derivatives of the harmonics signal are used to calculate the ratio coefficient [20, 65, 66]:and the can be extracted as follows [20, 65, 66]:where is the ratio of the planar Hall resistance RPHE and AHE resistance RAHE. Note that the reported RPHE is typically much smaller than RAHE [66], giving rise to the following approximation: [25, 66, 67]. Notably, the slope of V2ωx versus the field along the x axis is much larger than the slope of V2ωy versus field along the y axis, indicating a negligible contribution from the field-like SOT. Hence, we only consider the damping-like SOT in this work. From , can be calculated based on the following equation [68, 69]:

FIGURE 4

(A) Schematic diagram of harmonic measurements of Pt/Co(0.8)/Ni(1) samples. The aspect ratio of the Hall cross is 1:3 to minimize Joule heating effects. Insert: M vs B curves on Pt (111)/Co(0.8)/Ni(1). Measured in-plane longitudinal field dependence of (B) first-harmonic Hall signal and second-harmonic Hall signal in Pt/Co(0.8)/Ni(1) sample. (C) Temperature dependence of the charge-to-spin conversion efficiency measured on polycrystalline Pt and epitaxial Pt (111).

Figure 4C presents the obtained temperature-dependent of epitaxial and polycrystalline Pt films. As mentioned before, the growth condition of Co/Ni on Pt (111) is consistent with the growth condition of Co/Ni on polycrystalline Pt. Furthermore, the saturated magnetization of Pt/Co/Ni for both polycrystalline Pt and Pt (111) sample is nearly the same (600 kA/m), suggesting similar surface conditions. We can see that measured on Pt (111) at room temperature agrees well with the value obtained from ST-FMR measurements. Also, of polycrystalline Pt is about 3 times larger than that of the epitaxial Pt (111), which is comparable with the values reported in other studies [24]. In the temperature range of our measurements, of both polycrystalline and epitaxial Pt films decreases monotonically with temperature. Due to the high residual-to-resistance ratio in epitaxial Pt (111), the shunting effect becomes significantly pronounced in the low-temperature regime; thus, the measured anomalous Hall signals coming from Co/Ni become negligibly small below 150 K. In metals with spin–orbit coupling, spin Hall conductivity is predicted to scale with linearly or quadratically [70]. The former contribution results from the extrinsic scattering in “clean metals,” and the latter one is driven by the intrinsic mechanism in “dirty metals” [70]. Isasa et al. reported that the intrinsic mechanism dominates the SHE in polycrystalline Pt [71], while for the case of epitaxial Pt (111) with significantly reduced resistivity, the weight of extrinsic mechanism is reasonably raised in “cleaner” epitaxial Pt (111). Our results support the previous picture.

Conclusion

In summary, we have prepared high-quality epitaxial Pt thin films on a series of substrates. Systematic ST-FMR measurements demonstrate the isotropic nature of SHE in the high-symmetry Pt (200) and Pt (111) films. In contrast, the low-symmetry system such as (220) orientated Pt exhibits the anisotropic SHE behavior that is correlated to the anisotropic resistivity. The temperature-dependent harmonic measurements further suggest that SOT can be a hint for “cleaner” metals with more extrinsic contribution to SHE. The observed crystalline orientation–dependent of epitaxial Pt could be readily extended to other Pt/FM heterostructures with a broad range selection of FMs. Our work reveals the underlying mechanism of SHE in crystalline textured metals and broadens the material scope available for developing energy-favorable spintronic devices for next-generation information technologies.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

YX and EF conceived the idea and designed the project. YX fabricated devices and performed characterization. YX and HW performed the measurements. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported as part of Quantum Materials for Energy Efficient Neuromorphic Computing, an Energy Frontier Research Center (QMEEN-C EFRC) funded by the United States DOE, Office of Science under Award No. DE-SC0019273. Device microfabrication was performed at the San Diego Nanotechnology Infrastructure at University of California, San Diego (UCSD), a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure, which is supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant ECCS-1542148).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank R. Descoteaux for technical assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphy.2021.791736/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

MironIMGarelloKGaudinGZermattenP-JCostacheMVAuffretSet alPerpendicular Switching of a Single Ferromagnetic Layer Induced by In-Plane Current Injection. Nature (2011) 476:189–93. 10.1038/nature10309

2.

MironIMMooreTSzambolicsHBuda-PrejbeanuLDAuffretSRodmacqBet alFast Current-Induced Domain-wall Motion Controlled by the Rashba Effect. Nat Mater (2011) 10:419–23. 10.1038/nmat3020

3.

LiuLPaiC-FLiYTsengHWRalphDCBuhrmanRA. Spin-Torque Switching with the Giant Spin Hall Effect of Tantalum. Science (2012) 336:5. 10.1126/science.1218197

4.

LiuLLeeOJGudmundsenTJRalphDCBuhrmanRA. Current-Induced Switching of Perpendicularly Magnetized Magnetic Layers Using Spin Torque from the Spin Hall Effect. Phys Rev Lett (2012) 109:096602. 10.1103/physrevlett.109.096602

5.

HanJRichardellaASiddiquiSAFinleyJSamarthNLiuL. Room-Temperature Spin-Orbit Torque Switching Induced by a Topological Insulator. Phys Rev Lett (2017) 119:077702. 10.1103/physrevlett.119.077702

6.

JiangMAsaharaHSatoSKanakiTYamasakiHOhyaSet alEfficient Full Spin-Orbit Torque Switching in a Single Layer of a Perpendicularly Magnetized Single-Crystalline Ferromagnet. Nat Commun (2019) 10:2590. 10.1038/s41467-019-10553-x

7.

HirschJE. Spin Hall Effect. Phys Rev Lett (1999) 83:1834–7. 10.1103/physrevlett.83.1834

8.

TanakaTKontaniHNaitoMNaitoTHirashimaDSYamadaKet alIntrinsic Spin Hall Effect and Orbital Hall Effect In4dand5dtransition Metals. Phys Rev B (2008) 77:165117. 10.1103/physrevb.77.165117

9.

RashbaEI. Properties of Semiconductors with an Extremum Loop. I. Cyclotron and Combinational Resonance in a Magnetic Field Perpendicular to the Plane of the Loop. Sov Phys Solid State (1960) 2:1109.

10.

RashbaEIBychkovYA. Oscillatory Effects and the Magnetic Susceptibility of Carriers in Inversion Layers. J Phys C (1984) 17:6039.

11.

EdelsteinVM. Spin Polarization of Conduction Electrons Induced by Electric Current in Two-Dimensional Asymmetric Electron Systems. Solid State Commun (1990) 73:233–5. 10.1016/0038-1098(90)90963-c

12.

LauY-CBettoDRodeKCoeyJMDStamenovP. Spin-orbit Torque Switching without an External Field Using Interlayer Exchange Coupling. Nat Nanotech (2016) 11:758–62. 10.1038/nnano.2016.84

13.

KhitunABaoMWangKL. Magnonic Logic Circuits. J Phys D: Appl Phys (2010) 43:264005. 10.1088/0022-3727/43/26/264005

14.

GrollierJQuerliozDCamsariKYEverschor-SitteKFukamiSStilesMD. Neuromorphic Spintronics. Nat Electron (2020) 3:360–70. 10.1038/s41928-019-0360-9

15.

LiuLMoriyamaTRalphDCBuhrmanRA. Spin-Torque Ferromagnetic Resonance Induced by the Spin Hall Effect. Phys Rev Lett (2011) 106:036601. 10.1103/physrevlett.106.036601

16.

MihajlovićGPearsonJEGarciaMABaderSDHoffmannA. Negative Nonlocal Resistance in Mesoscopic Gold Hall Bars: Absence of the Giant Spin Hall Effect. Phys Rev Lett (2009) 103:166601.

17.

El HadriMSGibbonsJXiaoYRenHAravaHLiuYet alLarge Spin-to-Charge Conversion in Ultrathin Gold-Silicon Multilayers. Phys Rev Mater (2021) 5:064410. 10.1103/physrevmaterials.5.064410

18.

PaiC-FLiuLLiYTsengHWRalphDCBuhrmanRA. Spin Transfer Torque Devices Utilizing the Giant Spin Hall Effect of Tungsten. Appl Phys Lett (2012) 101:122404. 10.1063/1.4753947

19.

RenHWuS-YSunJZFullertonEE. Ion Beam Etching Dependence of Spin-Orbit Torque Memory Devices with Switching Current Densities Reduced by Hf Interlayers. APL Mater (2021) 9:091101. 10.1063/5.0060461

20.

KimJSinhaJHayashiMYamanouchiMFukamiSSuzukiTet alLayer Thickness Dependence of the Current-Induced Effective Field Vector in Ta|CoFeB|MgO. Nat Mater (2013) 12:240–5. 10.1038/nmat3522

21.

ChenT-YWuC-TYenH-WPaiC-F. Tunable Spin-Orbit Torque in Cu-Ta Binary alloy Heterostructures. Phys Rev B (2017) 96:104434. 10.1103/physrevb.96.104434

22.

OuYRalphDCBuhrmanRA. Strong Enhancement of the Spin Hall Effect by Spin Fluctuations near the Curie Point of FexPt1–x Alloys. Phys .Rev .Lett (2018) 120:097203. 10.1103/physrevlett.120.097203

23.

ZhangWJungfleischMBFreimuthFJiangWSklenarJPearsonJEet alAll-electrical Manipulation of Magnetization Dynamics in a Ferromagnet by Antiferromagnets with Anisotropic Spin Hall Effects. Phys Rev B (2015) 92:144405. 10.1103/physrevb.92.144405

24.

RyuJAvciCOKarubeSKohdaMBeachGSDNittaJ. Crystal Orientation Dependence of Spin-Orbit Torques in Co/Pt Bilayers. Appl Phys Lett (2019) 114:142402. 10.1063/1.5090610

25.

WangHMengK-YZhangPHouJTFinleyJHanJet alLarge Spin-Orbit Torque Observed in Epitaxial SrIrO3 Thin Films. Appl Phys Lett (2019) 114:232406. 10.1063/1.5097699

26.

SekiTIihamaSTaniguchiTTakanashiK. Large Spin Anomalous Hall Effect in L10−FePt : Symmetry and Magnetization Switching. Phys Rev B (2019) 100:144427. 10.1103/physrevb.100.144427

27.

LiHWangGLiDHuPZhouWMaXet alSpin-orbit Torque-Induced Magnetization Switching in Epitaxial Au/Fe4N Bilayer Films. Appl Phys Lett (2019) 114:092402. 10.1063/1.5078395

28.

GaborMSPetrisorTJrNasuiMNathJMironIM. Spin-Orbit Torques and Magnetization Switching in Perpendicularly Magnetized Epitaxial Pd/Co2FeAl/MgO Structures. Phys Rev Appl (2020) 13:054039. 10.1103/physrevapplied.13.054039

29.

ThompsonRRyuJDuYKarubeSKohdaMNittaJ. Current Direction Dependent Spin Hall Magnetoresistance in Epitaxial Pt/Co Bilayers on MgO(110). Phys Rev B (2020) 101:214415. 10.1103/physrevb.101.214415

30.

ThompsonRRyuJChoiGKohdaMNittaJet alAnisotropic Spin-Orbit Torque through Crystal-Orientation Engineering in Epitaxial Pt. Phys Rev Appl (2021) 15:014055. 10.1103/physrevapplied.15.014055

31.

RyuJKohdaMNittaJ. Observation of the D'yakonov-Perel' Spin Relaxation in Single-Crystalline Pt Thin Films. Phys Rev Lett (2016) 116:256802. 10.1103/physrevlett.116.256802

32.

GamouHDuYKohdaMNittaJ. Enhancement of Spin Current Generation in Epitaxial α -Ta/CoFeB Bilayer. Phys Rev B (2019) 99:184408. 10.1103/physrevb.99.184408

33.

HongDAnandNLiuCLiuHArslanIPearsonJEet alLarge Anomalous Nernst and Inverse Spin-Hall Effects in Epitaxial Thin Films of Kagome Semimetal Mn3Ge. Phys Rev Mater (2020) 4:094201. 10.1103/physrevmaterials.4.094201

34.

KhangNHDUedaYHaiPN. A Conductive Topological Insulator with Large Spin Hall Effect for Ultralow Power Spin-Orbit Torque Switching. Nat Mater (2018) 17:808–13. 10.1038/s41563-018-0137-y

35.

JamaliMLeeJSJeongJSMahfouziFLvYZhaoZet alGiant Spin Pumping and Inverse Spin Hall Effect in the Presence of Surface and Bulk Spin−Orbit Coupling of Topological Insulator Bi2Se3. Nano Lett (2015) 15:7126–32. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b03274

36.

ZhangWHanWYangS-HSunYZhangYYanBet alGiant Facet-dependent Spin-Orbit Torque and Spin Hall Conductivity in the Triangular Antiferromagnet IrMn 3. Sci Adv (2016) 2:1600759. 10.1126/sciadv.1600759

37.

EngelBNEnglandCDvan LeeuwenRAWiedmannMHFalcoCM. Interface Magnetic Anisotropy in Epitaxial Superlattices. Phys Rev Lett (1991) 67:1910–3. 10.1103/physrevlett.67.1910

38.

DzyaloshinskiiI. A Thermodynamic Theory of Weak Ferromagnetism of Antiferromagnetics. J Phys Chem Sol (1958) 4:241.

39.

MoriyaT. Anisotropic Superexchange Interaction and Weak Ferromagnetism. Phys Rev (1960) 120:91.

40.

NembachHTShawJMWeilerMJuéESilvaTJ. Linear Relation between Heisenberg Exchange and Interfacial Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya Interaction in Metal Films. Nat Phys (2015) 11:825–9. 10.1038/nphys3418

41.

HoffmannMZimmermannBMüllerGPSchürhoffDKiselevNSMelcherCet alAntiskyrmions Stabilized at Interfaces by Anisotropic Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya Interactions. Nat Commun (2017) 8:1. 10.1038/s41467-017-00313-0

42.

CamosiLRohartSFruchartOPizziniSBelmeguenaiMRoussignéYet alAnisotropic Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya Interaction in Ultrathin Epitaxial Au/Co/W(110). Phys Rev B (2017) 95:214422. 10.1103/physrevb.95.214422

43.

RaeliarijaonaANepalRKovalevAA. Boundary Twists, Instabilities, and Creation of Skyrmions and Antiskyrmions. Phys Rev Mater (2018) 2:124401. 10.1103/physrevmaterials.2.124401

44.

TsurkanSZakeriK. Giant Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya Interaction in Epitaxial Co/Fe Bilayers with C2v Symmetry. Phys Rev B (2020) 102:060406. 10.1103/physrevb.102.060406

45.

FanYUpadhyayaPKouXLangMTakeiSWangZet alMagnetization Switching through Giant Spin-Orbit Torque in a Magnetically Doped Topological Insulator Heterostructure. Nat Mater (2014) 13:699–704. 10.1038/nmat3973

46.

WangYDeoraniPQiuXKwonJHYangH. Determination of Intrinsic Spin Hall Angle in Pt. Appl Phys Lett (2014) 105:152412. 10.1063/1.4898593

47.

MellnikARLeeJSRichardellaAGrabJLMintunPJFischerMHet alSpin-transfer Torque Generated by a Topological Insulator. Nature (2014) 511:449–51. 10.1038/nature13534

48.

NanTEmoriSBooneCTWangXOxholmTMJonesJGGet alComparison of Spin-Orbit Torques and Spin Pumping across NiFe/Pt and NiFe/Cu/Pt Interfaces. Phys Rev B (2015) 91:214416. 10.1103/physrevb.91.214416

49.

XuJWKentAD. Charge-To-Spin Conversion Efficiency in Ferromagnetic Nanowires by Spin Torque Ferromagnetic Resonance: Reconciling Lineshape and Linewidth Analysis Methods. Phys Rev Appl (2020) 14:014012. 10.1103/physrevapplied.14.014012

50.

MüllerMLiensbergerLFlackeLHueblHKamraABelzigWet alGrowth Optimization of TaN for Superconducting Spintronics. Phys Rev Lett (2021) 126:087201.

51.

DaalderopGHOKellyPJden BroederFJA. Prediction and Confirmation of Perpendicular Magnetic Anisotropy in Co/Ni Multilayers. Phys Rev Lett (1992) 68:682–5. 10.1103/physrevlett.68.682

52.

BrockJAMontoyaSAImM-YFullertonEE. Energy-efficient Generation of Skyrmion Phases in Co/Ni/Pt-Based Multilayers Using Joule Heating. Phys Rev Mater (2020) 4:104409. 10.1103/physrevmaterials.4.104409

53.

McMichaelRDTwisselmannDJKunzA. Localized Ferromagnetic Resonance in Inhomogeneous Thin Films. Phys Rev Lett (2003) 90:227601. 10.1103/physrevlett.90.227601

54.

ZhuLRalphDCBuhrmanRA. Effective Spin-Mixing Conductance of Heavy-Metal-Ferromagnet Interfaces. Phys Rev Lett (2019) 123:057203. 10.1103/physrevlett.123.057203

55.

LairsonBMVisokayMRSinclairRHagstromSClemensBM. Epitaxial Pt(001), Pt(110), and Pt(111) Films on MgO(001), MgO(110), MgO(111), and Al2O3(0001). Appl Phys Lett (1992) 61:1390–2. 10.1063/1.107547

56.

SlonczewskiJC. Current-driven Excitation of Magnetic Multilayers. J Magnetism Magn Mater (1996) 159:L1–L7. 10.1016/0304-8853(96)00062-5

57.

SankeyJCBragancaPMGarciaAGFKrivorotovINBuhrmanRARalphDC. Spin-Transfer-Driven Ferromagnetic Resonance of Individual Nanomagnets. Phys Rev Lett (2006) 96:227601. 10.1103/physrevlett.96.227601

58.

SankeyJCCuiY-TSunJZSlonczewskiJCBuhrmanRARalphDC. Measurement of the Spin-Transfer-Torque Vector in Magnetic Tunnel Junctions. Nat Phys (2008) 4:67–71. 10.1038/nphys783

59.

KittelC. On the Theory of Ferromagnetic Resonance Absorption. Phys Rev (1948) 73:155–61. 10.1103/physrev.73.155

60.

PetitSBaraducCThirionCEbelsULiuYLiMet alSpin-Torque Influence on the High-Frequency Magnetization Fluctuations in Magnetic Tunnel Junctions. Phys Rev Lett (2007) 98:077203. 10.1103/physrevlett.98.077203

61.

GuillemardCPetit-WatelotSAndrieuSRojas-SánchezJ-C. Charge-spin Current Conversion in High Quality Epitaxial Fe/Pt Systems: Isotropic Spin Hall Angle along Different In-Plane Crystalline Directions. Appl Phys Lett (2018) 113:262404. 10.1063/1.5079236

62.

SongCZhangRLiaoLZhouYZhouXChenRet alSpin-orbit Torques: Materials, Mechanisms, Performances, and Potential Applications. Prog Mater Sci (2021) 118:100761. 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2020.100761

63.

CiccarelliCAndersonLTshitoyanVFergusonAJGerhardFGouldCet alRoom-temperature Spin-Orbit Torque in NiMnSb. Nat Phys (2016) 12:855–60. 10.1038/nphys3772

64.

SimonESzilvaAUjfalussyBLazarovitsBZarandGSzunyoghL. Anisotropic Rashba Splitting of Surface States from the Admixture of Bulk States: Relativisticab Initiocalculations Andk⋅pperturbation Theory. Phys Rev B (2010) 81:235438. 10.1103/physrevb.81.235438

65.

HayashiMKimJYamanouchiMOhnoH. Quantitative Characterization of the Spin-Orbit Torque Using Harmonic Hall Voltage Measurements. Phys Rev B (2014) 89:144425. 10.1103/physrevb.89.144425

66.

GarelloKMironIMAvciCOFreimuthFMokrousovYBlügelSet alSymmetry and Magnitude of Spin-Orbit Torques in Ferromagnetic Heterostructures. Nat Nanotech (2013) 8:587–93. 10.1038/nnano.2013.145

67.

ZhengZZhangYFengXZhangKNanJZhangZet alEnhanced Spin-Orbit Torque and Multilevel Current-Induced Switching in W/Co−Tb/Pt Heterostructure. Phys Rev Appl (2019) 12:044032. 10.1103/physrevapplied.12.044032

68.

PaiC-FMannMTanAJBeachGSD. Determination of Spin Torque Efficiencies in Heterostructures with Perpendicular Magnetic Anisotropy. Phys Rev B (2016) 93:144409. 10.1103/physrevb.93.144409

69.

Seung HamWKimSKimD-HKimK-JOkunoTYoshikawaHet alTemperature Dependence of Spin-Orbit Effective fields in Pt/GdFeCo Bilayers. Appl Phys Lett (2017) 110:242405. 10.1063/1.4985436

70.

NagaosaNSinovaJOnodaSMacDonaldAHOngNP. Anomalous Hall Effect. Rev Mod Phys (2010) 82:1539. 10.1103/revmodphys.82.1539

71.

IsasaMVillamorEHuesoLEGradhandMCasanovaF. Temperature Dependence of Spin Diffusion Length and Spin Hall Angle in Au and Pt. Phys Rev B (2015) 91:024402. 10.1103/physrevb.91.024402

Summary

Keywords

spin Hall effect, spin torque ferromagnetic resonance, harmonics, epitaxial, platinum

Citation

Xiao Y, Wang H and Fullerton EE (2022) Crystalline Orientation–Dependent Spin Hall Effect in Epitaxial Platinum. Front. Phys. 9:791736. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2021.791736

Received

08 October 2021

Accepted

06 December 2021

Published

05 January 2022

Volume

9 - 2021

Edited by

Weiwei Lin, Southeast University, China

Reviewed by

Cheng Song, Tsinghua University, China

Guoqiang Yu, Institute of Physics (CAS), China

Shiheng Liang, Hubei University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Xiao, Wang and Fullerton.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eric E. Fullerton, efullerton@ucsd.edu

This article was submitted to Interdisciplinary Physics, a section of the journal Frontiers in Physics

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.