Abstract

Urban systems are characterized by populations with heterogeneous characteristics, and whose spatial distribution is crucial to understand inequalities in life expectancy or education level. Traditional studies on spatial segregation indicators focus often on first-neighbour correlations but fail to capture complex multi-scale patterns. In this work, we aim at characterizing the spatial distribution heterogeneity of socioeconomic features through diffusion and synchronization dynamics. In particular, we use the time needed to reach the synchronization as a proxy for the spatial heterogeneity of a socioeconomic feature, as for example, the income. Our analysis for 16 income categories in cities from the United States reveals that the spatial distribution of the most deprived and affluent citizens leads to higher diffusion and synchronization times. By measuring the time needed for a neighborhood to reach the global phase we are able to detect those that suffer from a steeper segregation. Overall, the present manuscript exemplifies how diffusion and synchronization dynamics can be used to assess the heterogeneity in the presence of node information.

1 Introduction

The expansion of urbanization and progressive increase of the population in cities has intensified the concern over the many dimensions of segregation—i.e., school, economic or ethnics—that have a tangible impact in the health, education and equal opportunities of citizens [1–8]. In fact, quantifying the extent of segregation and the identification of economically and socially isolated neighborhoods has been a topic of wide interest that first led to the development of global metrics, and which were later extended to spatial metrics [9–14]. Most of the initial spatial measures were limited to first neighbour indices, which facilitated the development of multi-scalar indices that provide a more nuanced picture of segregation [15–21], yet understanding the role played by each of the scales and their interplay still remains a challenge.

Dynamical processes in general, and in particular diffusion [22–30] and synchronization [31–35] dynamics, have been widely studied in complex networks on account of their relation with the spread of diseases and information [36, 37] and real-world phenomena in social or economic systems [38–40]. Interestingly, they provide insights on the topological scales and structure of networks and reveal the existence of functional meso-scale structures [27, 30, 32, 34, 41].

Here we use previous knowledge on diffusion and synchronization dynamics to assess the multi-scale patterns of residential segregation. By moving the focus from the network topology and organization to the node states, we are able to measure how well distributed a population with a certain characteristic is using the time needed to reach the absorbing state. Our framework requires thus the implementation of a population dynamic to drive the system towards the homogeneous state, in our case diffusion and synchronization dynamics. None of them constitute here an attempt to model or predict the changes in the spatial distribution of a population characteristic but are highly stylized simplifications of their evolution that allow us to measure the time needed to attain the homogeneous state, which we consider to be the non-segregated scenario. Dynamical approaches are thus introduced here not because they provide a realistic approximation to the evolution of population dynamics but because they offer a significant advantage to measure multi-scale correlations as they do not require to take distance explicitly into account. Moreover, the assumption that cities converge towards uniformity is rather unrealistic without a heavy external driver, and is only a means to construct our measures.

As case studies we provide an analysis on the distribution of citizens of a certain income category in cities from the United States, and the distribution of a set of socioeconomic indicators in the city of Paris throughout an average day (see Supplementary Material Section 2 and Supplementary Figures S8–S10). The analysis on the spatial organization of income categories reveals that the most deprived and affluent sectors display higher diffusion and synchronization times linked to a higher heterogeneity, and allow us to split the cities in two groups depending on the difference on the level of segregation. Finally, we evaluate the level of synchronization at the neighborhood level which allow us to spot the more sensitive places in a city.

2 Results

2.1 Diffusion Dynamics and Income Segregation

Citizens exhibit a huge diversity of characteristics usually captured by socioeconomic indicators such as education level, income or ethnicity, and they are often heterogeneously distributed in space: those individuals with similar characteristics tend to live close between them. To assess the heterogeneity of a population with a characteristic k ∈ K, we consider a graph G(V, E) with adjacency matrix A = {aij} in which the spatial units are represented as a set of nodes V connected by a set of edges E. The adjacency matrix A we have considered takes aij = 1 when spatial units i and j are adjacent and aij = 0 otherwise, which is the traditional connectivity matrix used to capture residential segregation. Still, other types of (weighted) matrices could be considered to assess, for example, the impact of mobility in segregation. The state of a node is given by the fraction of citizens living in node i that belong to socioeconomic category (or class) k, written aswhere is the total number of citizens in unit i that belong to category k. As extreme cases, when there are no citizens of category k living in i, and when all the citizens in node i belong to category k. Of course, the normalization conditionis fulfilled for all nodes i.

To measure the multi-scalar patterns of segregation, our assumption is that cities suffering from stronger residential segregation are further from the stationary state where the citizens of category k are homogeneously distributed in space. Although cities are in continuous change and most likely far from equilibrium, similar approaches such as the long-standing Schelling and the Alonso-Muth-Mills models have been able to draw relevant conclusions from the equilibrium state [42, 43].

By adopting diffusion dynamics we do not refuse the high complexity of population dynamics influenced by a wide variety of demographic, economic, political, and behavioral factors [44–47] but avoid introducing further parameters and factors that could hinder our aim of characterizing the segregation of a particular population category. Bear in mind that our final goal is by no means to assess real-world migration processes but to construct a multi-scalar measure of segregation that does not explicitly include the distance and the use of more complex and realistic approaches that would complicate the interpretation of the results. Diffusion constitutes one of the most basic approximations to how information, or any other characteristic, is transmitted through a system. Although far from the real behavior, it provides one of the simplest scenarios where the flow of population follows a gradient.

In fact, we focus on one of the best-case scenarios where the values of converge towards equilibrium following a gradient, which could be interpreted as the change of residence of citizens of category k to regions where they are less abundant.

We focus on the economic segregation in the metropolitan areas of the United States with more than 1 million inhabitants and analyze a dataset containing the number of households within an income interval k residing in each census tract (see Table 1).

TABLE 1

| Class | Income ($) |

| 1 | Less than 10,000 |

| 2 | 10,000–14,999 |

| 3 | 15,000–19,999 |

| 4 | 20,000–24,999 |

| 5 | 25,000–29,999 |

| 6 | 30,000–34,999 |

| 7 | 35,000–39,999 |

| 8 | 40,000–44,999 |

| 9 | 45,000–49,999 |

| 10 | 50,000–59,999 |

| 11 | 60,000–74,999 |

| 12 | 75,000–99,999 |

| 13 | 100,000–124,999 |

| 14 | 125,000–149,999 |

| 15 | 150,000–199,999 |

| 16 | 200,000 or more |

Income range (in US dollars) corresponding to each category (or class).

Once we have the set of initial node states , their evolution through time is determined by the diffusion dynamicswhereis the degree of node i. For simplification purposes, we have opted to use a normalized diffusion dynamic, with diffusion strength equal to 1. Note that we have independent diffusion processes for each category k.

The diffusion dynamic lasts until the stationary state, , ∀i is reached, and we denote the spanned time as τdiff(k). Since the time to reach the stationary state can be infinitely large, we have considered that it is reached when the variance of , in time, becomes lower than 0.0001. We hypothesize that lower values of τdiff(k) are related to a more homogeneous distribution of the population within a category k, and the other way around when it is higher. In the extreme case in which all units have the same initial value of , the diffusion time τdiff(k) would attain its minimum value. As we aim to compare cities with different characteristics, we control for confounding factors such as the particular distribution of xk or the topology of the graph by running the same diffusion dynamics on the same graph but where the values of xk have been reshuffled, thus defining the average null-model diffusion time calculated over 500 reshuffling realizations. The relative diffusion time we will use throughout this manuscript can then be written asA relative diffusion time equal to one means that it is compatible with the null model, i.e., there are no remarkable spatial dependencies, while a greater value suggests that spatial heterogeneities delay the arrival to the stationary state.

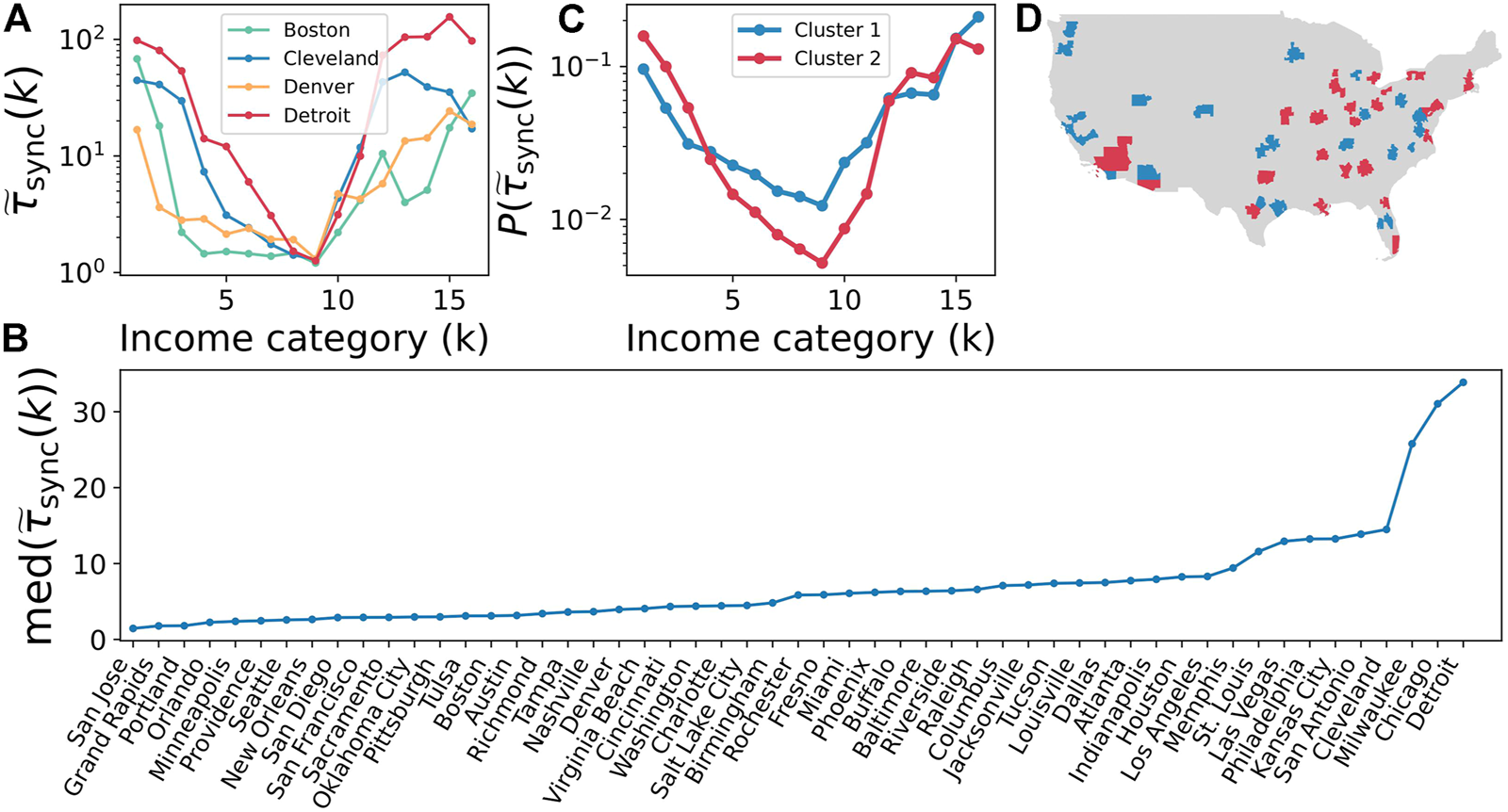

We analyze the normalized diffusion times by running simulations for all US cities above 1 million of inhabitants and each of the 16 income categories k as a proxy for how heterogeneously distributed is the population; we have excluded New York City, whose adjacency network does not provide an accurate picture of residential segregation due to the particular geography of Manhattan. In Figure 1A we display in Boston, Cleveland, Detroit and Denver observing a common qualitative behavior: smaller values for middle-income categories, and higher ones for the categories in the extremes of the income distribution. Our results suggest that the wealthier and most deprived citizens suffer from stronger segregation and display a more clustered spatial distribution. More interestingly, category 9 seems to be the more homogeneously distributed across space, in agreement with the results observed in [20] and with the mean and standard deviation of xk as well as the Moran’s I (see Supplementary Material Section 1 and Supplementary Figure S1). Still, there are strong quantitative differences, with Cleveland and Detroit displaying higher values for most of the categories, in contrast to Boston and Denver.

FIGURE 1

Diffusion dynamics as a measure for income segregation. (A) Synchronization time for each of the 16 income categories in Boston, Cleveland, Denver and Detroit. (B) Median value of across income categories as a function of its variance. (C) Ranking for the median value of for the studied set of US cities.

Since takes a set of 16 values for each city, we calculate their median and variance values over all categories to ease the comparison between the set of cities studied. While the median value provides information on the segregation across all economic categories, its variance reports the variability among them. Figure 1B shows this median value of , as a function of its variance, . The prior cities appear ordered as Detroit, Cleveland, Boston and Denver, although the variance is very similar for Cleveland and Boston, likely due to the high values observed for low-income categories in Boston. Finally, we provide in Figure 1C the ranking of the selected US cities according to , as a measure of the overall segregation in cities. On top of it, we find cities such as Milwaukee or Detroit, which have been reported to suffer from economic and ethnic segregation [49–51].

By applying diffusion dynamics we implicitly assume that xk evolves homogeneously towards consensus, which more than a realistic scenario, it is a means to calculate the time needed to reach consensus and obtain a measure of segregation. To further inspect the actual change of between 2011 and 2019 in each of the spatial units i, we first construct the normalized time-series for each spatial unit across those years asand then cluster, for each category k, the temporal profiles of all the nodes. For the clustering, we have made use of the k-means algorithm [52, 53], grouping together those units with a similar temporal evolution, and setting the number of clusters to 3. The resulting time-series of the corresponding centroids for the highest and lowest income categories are depicted in Figure 2, where a non-monotonic behavior is observed in most of the cases, with oscillatory behaviors through time of varying amplitude.

FIGURE 2

Average temporal evolution of the abundance of households within the lowest and highest income. Temporal evolution of centroids after performing a k-means clustering on the normalized abundance of households with category k, , as a function of time t for the lower (A) and higher (B) income categories.

2.2 Synchronization Dynamics and Income Segregation

According to the oscillations in the temporal evolution of (Figure 2), diffusion dynamics appear to be a rather simplistic approach to assess the time needed to converge. Even thought we do not aim to mimic the real evolution of , we seek for a dynamic that at least can resemble its real behaviour in a qualitative way. Thus, despite still constituting a stylized approximation, a dynamical process with an oscillatory behavior, like a system of coupled Kuramoto oscillators, appears to be a better way to assess the spatial heterogeneity of socioeconomic indicators across cities. To analyze segregation in terms of synchronization dynamics, we treat each of the spatial units i as an individual Kuramoto oscillator, with an initial phase that is set by distributing the fraction of population in node i that belongs to a category k within the range [0, π] asThe interaction between spatial units is given by the Kuramoto modelwhere we have modified the traditional interaction term between oscillators by dividing the angle difference by two, allowing for the interaction between regions displaying extreme values of . Additionally, to facilitate the global synchronization of the system, we set all the individual natural frequencies of the oscillators to the same value, i.e., ωi = 1, ∀i. In order to account separately the segregation of each category k, our approach assumes that there is no interaction between categories and, thus, synchronize independently of k.

We use the standard order parameter |zk| to assess the global level of synchronization for a category k in a city, whereand N is the total number of spatial units or Kuramoto oscillators [35]. We consider that a city has reached the synchronized state when |zk| > 0.999. As in the case of diffusion, we assess how the distribution of initial phases determines the synchronization of the system, a city in our case, by measuring the time τsync(k) required to reach the synchronized state. The more heterogeneously distributed the initial phases are, the higher the time the system requires to synchronize. To distinguish between the effect produced by the spatial distribution from its overall distribution as well as the topology of the graph, we also measure the average time the system needs to synchronize when the same phases are redistributed at random, . The normalized synchronization time of the system is then given by the ratioLike for diffusion, a synchronization time close to one means that the spatial distribution of phases is compatible with the null model, and a larger value indicates that spatial heterogeneities delay the appearance of a synchronized state.

In Figure 3A we inspect the normalized synchronization time in Boston, Cleveland, Detroit and Denver when spatial units interact through Kuramoto-like dynamics. All four of them share similar features, with central classes displaying smaller synchronization times compared to the most disadvantaged and wealthier ones. An expected result since those individuals in the extremes of the income distribution tend to be more isolated and clustered together compared to middle-income citizens. Despite sharing qualitative features, the cities shown display sharp quantitative differences. Almost all categories appear to be significantly more isolated in Detroit and Cleveland compared to Denver and Boston, where looks much flat. Overall, the synchronization results are compatible with the diffusion ones, likely because both dynamical processes share common features. We have further checked that the mean xk does not determine directly the normalized synchronization times in Supplementary Figure S1.

FIGURE 3

Synchronization time as a measure for income segregation. (A) Synchronization time for each of the 16 income categories in Boston, Cleveland, Denver and Detroit. (B) Ranking for the median value of for the studied set of US cities. (C) Average value of as a function of each income category i for the two main clusters detected. (D) Location and cluster assignment for each of the analyzed cities.

Likewise with diffusion, we calculate the median and variance of over all categories to be able to compare between analyzed cities (see Supplementary Figure S2 for the individual rankings of for the categories k = 1 and k = 16). The ranking is shown in Figure 3B and has cities such as Detroit, Cleveland, Milwaukee or Memphis close to the top, which are well-known for being among the most economically segregated cities in the United States. The location in the ranking of the cities in Figure 3A is consistent with our observations, with Boston and Denver on the bottom of the ranking and Detroit and Cleveland on the top of it.

Our index is given by the median value of the normalized synchronization times, yet depending on the dimension of segregation we aim to capture, we can also construct an index based on a population-weighted average. Whereas the median gives equal weight to each economic category focusing on the segregation suffered by residents of category k, the weighted average provides an overall picture of segregation taking the population of each category into account. We show the ranking obtained for the weighted average index and its relation with in Supplementary Figures S6, S7. Additionally, we show in Supplementary Figures S3, S4 how significantly correlates with the traditional Moran’s I [54] as well as a multi-scale quantity based on class mean first passage times developed in [20, 21], reinforcing the idea that synchronization (and diffusion) dynamics indeed capture the patterns of residential segregation. Despite the dynamics we have used are stylized versions of the real behavior of the quantity and do not capture the full complexity of its temporal evolution, it is able to capture segregation with values comparable to other segregation indicators.

Although is larger for extreme categories in most of the cities, some of them like Denver display smaller variations than others such as Detroit and, therefore, it might be of interest to group cities according to the change in synchronization times. By running a k-means algorithm on the normalized value of so that , we can split the cities of study between those with higher and smaller differences in , see Figure 3C. In Figure 3D, we display the cluster assigned to each metropolitan area, where no strong spatial pattern is observed. Still, the cities in the Midwest, which are known for being economically segregated, fall into the red cluster, together with other cities such as Baltimore or Los Angeles. If, instead, we focus on the blue cluster, we have cities such as Sacramento or Washington D.C. Among the cities discussed in Figure 3A, Denver falls into the group with more homogeneous segregation (in blue) and the rest into the one with more unequal segregation patterns (in red).

Beyond the global quantification of segregation, we can also evaluate the local level of segregation of a concrete census tract i at a given time step t by computingwhere is the phase of unit i at time t and Φk(t) is the average phase of all the oscillators in a city in a given time t [32]. When we consider that oscillator i has synchronized, from which we can obtain . However, given that can oscillate through time, we only consider that a unit i has reached the global synchronized state at a time when does not go below 0.999 anymore, otherwise our methodology could fail to capture long-range correlations. In order to provide a metric for each spatial unit, simulations last until each of the spatial units have fullfiled the synchronization criteria. Normalizing by its null model counterpart, it yields , a measure of the local synchronization time.

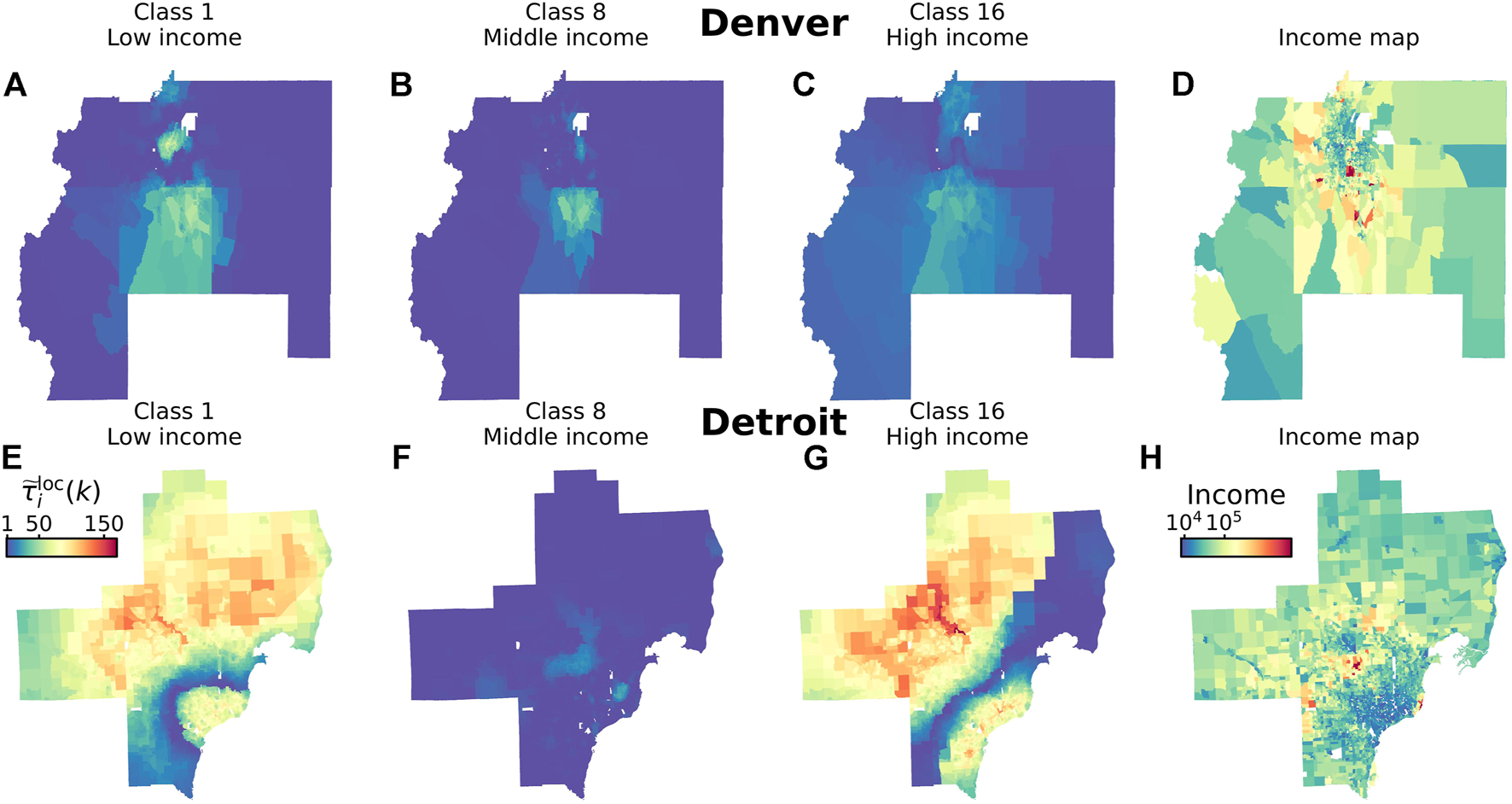

Figure 4 displays the normalized synchronization times for each of the census tracts in Denver and Detroit, focusing on three very distinct income categories: low income, Figures 4A,E; middle income, Figures 4B,F; and high income, Figures 4C,G. To ease the comparison between income categories, the range of values is common for all the maps, evincing the strong differences between Detroit and Denver, especially for the low and high-income categories. Figures 4D,H also report the income per census tract. The shape of the segregation in Detroit can be outlined by the lower-income downtown and the richer suburbs, being the most segregated parts, and a less-segregated region in-between. In the case of Denver, we only slightly see high values for the low-income category in the North of the city and the high-income category in the South.

FIGURE 4

Local synchronization time as a measure for income segregation. Normalized synchronization time for each census tract in Denver (A–C) and Detroit (E–G) for three different income categories: (A,E) class 1 (low income); (B,F) class 8 (middle income); (C,G) class 16 (high income). We provide as a reference the median income of each census tract in (D) Denver and (H) Detroit.

As we detail in Supplementary Figure S5, the spatial patterns of segregation product of the synchronization dynamics are significantly different to those obtained from first-neighbor quantities such as the Moran’s I. Instead of focusing on those regions whose proportion of citizens is high (or low) compared to its neighbors, our methodology highlights those with a ratio of population within a category k distinct than the average, either because it is high or low, and spatially isolated from those regions with average values. In other words, a region with a high proportion of residents of category k might not show a large local spatial correlation if their neighbors have similar values but could, instead, produce high values of if it is isolated from those regions displaying a proportion of citizens closer to the city average. As the majority of spatial measures, our approach can also suffer the so-called modifiable areal unit problem [55] in a similar fashion. However, given that our methodology captures mid and long-range correlations instead of local differences, it might be less affected by such small local changes.

Finally, we inspect if the synchronization time of a region displays any type of connection with its actual income. To do so, we plot in Figure 5 the normalized local synchronization time as a function of the median income averaged over all the census tracts within bins of $5,000 in four US cities. Again we see that segregation is much stronger in Detroit followed by Cleveland and Boston. High-income regions are more segregated in Boston compared to Cleveland. In general terms, the census tracts with a median income between $50,000 and $80,000 seem to be the less segregated ones as they synchronize faster for both low and high-income categories. These results are in agreement with the cluster assignment of the previous cities, with Detroit, Cleveland and Boston in the red cluster where low and high-income categories need more time to synchronize, and Denver in the blue cluster where only the high-income categories need more time to synchronize.

FIGURE 5

Synchronization time and median income. Normalized synchronization time as a function of the median income averaged over bins of $5,000 for class 1 (A), class 8 (B) and class 16 (C).

3 Discussion

Traditional spatial segregation indicators that focus on local scale of segregation fail in most cases to capture the presence of long-range correlations, thus highlighting the need of multi-scale indices [15–21]. Our framework does not consider any specific scale, but uses a dynamical approach that captures the patterns of segregation across the multiple scales. We have revealed how categories in the extreme of the income distribution are more heterogeneously distributed in space compared to middle classes, displaying larger diffusion and synchronization times. This approach has also allowed us to group together those cities that display common features of segregation. In this context, it is important to note that our work does not attempt to model the evolution of income segregation nor can be used as a forecasting tool, but takes modeling assumptions to assess the level of segregation that a distribution of population exhibits.

Despite the main manuscript focuses on the economic segregation, our methodology can be used to assess the heterogeneity in the spatial distribution of any characteristic. Moreover, it can go beyond the spatial component of segregation by including in the analysis other types of graphs, e.g., the daily mobility network of citizens. In this way, we could assess how citizens of diverse socioeconomic environments interact through mobility [56–59].

Summarizing, we show how diffusion and synchronization dynamics can be used in some systems to assess the heterogeneity in the distribution of node features. While the present work focuses on the initial phases of oscillators and their synchronization time, node metadata could also be understood as an internal frequency and provide further insights on feature correlation across topological scales.

Statements

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs.

Author contributions

AB performed the research. AB, SG, and AA designed the research and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

AB acknowledges financial support from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación under the Juan de la Cierva program (FJC2019-038958-I). We acknowledge support by Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (PGC2018-094754-BC21, FIS2017-90782-REDT and RED2018-102518-T), Generalitat de Catalunya (2017SGR-896 and 2020PANDE00098), and Universitat Rovira i Virgili (2019PFR-URV-B2-41). AA acknowledges also ICREA Academia and the James S. McDonnell Foundation (220020325).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphy.2022.833426/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

KennedyBPKawachiIGlassRProthrow-StithD. Income Distribution, Socioeconomic Status, and Self Rated Health in the united states: Multilevel Analysis. BMJ (1998) 317:917–21. 10.1136/bmj.317.7163.917

2.

ElliottJR. Social Isolation and Labor Market Insulation: Network and Neighborhood Effects on Less-Educated Urban Workers. Sociological Q (1999) 40:199–216. 10.1111/j.1533-8525.1999.tb00545.x

3.

CollinsWJMargoRA. Residential Segregation and Socioeconomic Outcomes. Econ Lett (2000) 69:239–43. 10.1016/s0165-1765(00)00300-1

4.

RossNANobregaKDunnJ. Income Segregation, Income Inequality and Mortality in north American Metropolitan Areas. GeoJournal (2001) 53:117–24. 10.1023/a:1015720518936

5.

MayerSE. How Economic Segregation Affects Children's Educational Attainment. Social Forces (2002) 81:153–76. 10.1353/sof.2002.0053

6.

Acevedo-GarciaDLochnerKA. Residential Segregation and Health. Neighborhoods and Health (2003). p. 265–87. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195138382.003.0012Residential Segregation and Health

7.

WheelerCH. Urban Decentralization and Income Inequality: Is Sprawl Associated with Rising Income Segregation across Neighborhoods? FRB of St. Louis (2006). Working Paper No. 2006–037A.

8.

OwensA. Income Segregation between School Districts and Inequality in Students' Achievement. Sociol Educ (2018) 91:1–27. 10.1177/0038040717741180

9.

CliffADOrdJK. Spatial Processes: Models & Applications. Taylor & Francis (1981).

10.

DawkinsCJ. Measuring the Spatial Pattern of Residential Segregation. Urban Stud (2004) 41:833–51. 10.1080/0042098042000194133

11.

BrownLAChungS-Y. Spatial Segregation, Segregation Indices and the Geographical Perspective. Popul Space Place (2006) 12:125–43. 10.1002/psp.403

12.

DawkinsC. The Spatial Pattern of Black-white Segregation in Us Metropolitan Areas: an Exploratory Analysis. Urban Stud (2006) 43:1943–69. 10.1080/00420980600897792

13.

WongDWSShawS-L. Measuring Segregation: An Activity Space Approach. J Geogr Syst (2011) 13:127–45. 10.1007/s10109-010-0112-x

14.

ReySJSmithRJ. A Spatial Decomposition of the Gini Coefficient. Lett Spat Resour Sci (2013) 6:55–70. 10.1007/s12076-012-0086-z

15.

FarberSPáezAMorencyC. Activity Spaces and the Measurement of Clustering and Exposure: A Case Study of Linguistic Groups in Montreal. Environ Plan A (2012) 44:315–32. 10.1068/a44203

16.

LoufRBarthelemyM. Patterns of Residential Segregation. PLOS ONE (2016) 11:e0157476. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157476

17.

ChodrowPS. Structure and Information in Spatial Segregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A (2017) 114:11591–6. 10.1073/pnas.1708201114

18.

OlteanuMRandon-FurlingJClarkWAV. Segregation through the Multiscalar Lens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A (2019) 116:12250–4. 10.1073/pnas.1900192116

19.

SousaSNicosiaV. Quantifying Ethnic Segregation in Cities through Random Walks (2020). arXiv (2020) arXiv:2010.10462.

20.

BassolasANicosiaV. First-passage Times to Quantify and Compare Structural Correlations and Heterogeneity in Complex Systems. Commun Phys (2021) 4:1–14. 10.1038/s42005-021-00580-w

21.

BassolasASousaSNicosiaV. Diffusion Segregation and the Disproportionate Incidence of Covid-19 in African American Communities. J R Soc Interf (2021) 18:20200961. 10.1098/rsif.2020.0961

22.

GómezSDíaz-GuileraAGómez-GardeñesJPérez-VicenteCJMorenoYArenasA. Diffusion Dynamics on Multiplex Networks. Phys Rev Lett (2013) 110:028701. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.028701

23.

Solé-RibaltaADe DomenicoMKouvarisNEDíaz-GuileraAGómezSArenasA. Spectral Properties of the Laplacian of Multiplex Networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys (2013) 88:032807. 10.1103/PhysRevE.88.032807

24.

De DomenicoMSolé-RibaltaACozzoEKiveläMMorenoYPorterMAet alMathematical Formulation of Multilayer Networks. Phys Rev X (2013) 3:041022. 10.1103/physrevx.3.041022

25.

LiYChenWWangYZhangZL. Influence Diffusion Dynamics and Influence Maximization in Social Networks with Friend and Foe Relationships. Proc sixth ACM Int Conf Web search Data mining (2013) 657–66. 10.1145/2433396.2433478

26.

DelvenneJCLambiotteRRochaLE. Diffusion on Networked Systems Is a Question of Time or Structure. Nat Commun (2015) 6:7366–10. 10.1038/ncomms8366

27.

De DomenicoM. Diffusion Geometry Unravels the Emergence of Functional Clusters in Collective Phenomena. Phys Rev Lett (2017) 118:168301. 10.1103/physrevlett.118.168301

28.

MasudaNPorterMALambiotteR. Random Walks and Diffusion on Networks. Phys Rep (2017) 716-717:1–58. 10.1016/j.physrep.2017.07.007

29.

CencettiGBattistonF. Diffusive Behavior of Multiplex Networks. New J Phys (2019) 21:035006. 10.1088/1367-2630/ab060c

30.

BertagnolliGDe DomenicoM. Diffusion Geometry of Multiplex and Interdependent Systems. Phys Rev E (2021) 103:042301. 10.1103/PhysRevE.103.042301

31.

ArenasADíaz-GuileraAPérez-VicenteCJ. Synchronization Processes in Complex Networks. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena (2006) 224:27–34. 10.1016/j.physd.2006.09.029

32.

ArenasADíaz-GuileraAPérez-VicenteCJ. Synchronization Reveals Topological Scales in Complex Networks. Phys Rev Lett (2006) 96:114102. 10.1103/physrevlett.96.114102

33.

Gómez-GardeñesJMorenoYArenasA. Paths to Synchronization on Complex Networks. Phys Rev Lett (2007) 98:034101. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.034101

34.

Gómez-GardeñesJMorenoYArenasA. Synchronizability Determined by Coupling Strengths and Topology on Complex Networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys (2007) 75:066106. 10.1103/PhysRevE.75.066106

35.

ArenasADíaz-GuileraAKurthsJMorenoYZhouC. Synchronization in Complex Networks. Phys Rep (2008) 469:93–153. 10.1016/j.physrep.2008.09.002

36.

Gómez-GardeñesJSoriano-PañosDArenasA. Critical Regimes Driven by Recurrent Mobility Patterns of Reaction-Diffusion Processes in Networks. Nat Phys (2018) 14:391–5. 10.1038/s41567-017-0022-7

37.

ZhangZ-KLiuCZhanX-XLuXZhangC-XZhangY-C. Dynamics of Information Diffusion and its Applications on Complex Networks. Phys Rep (2016) 651:1–34. 10.1016/j.physrep.2016.07.002

38.

PluchinoALatoraVRapisardaA. Changing Opinions in a Changing World: A New Perspective in Sociophysics. Int J Mod Phys C (2005) 16:515–31. 10.1142/s0129183105007261

39.

CalderónCChongASteinE. Trade Intensity and Business Cycle Synchronization: Are Developing Countries Any Different?J Int Econ (2007) 71:2–21. 10.1016/j.jinteco.2006.06.001

40.

ErolaPDíaz-GuileraAGómezSArenasA. Modeling International Crisis Synchronization in the World Trade Web, 7. Networks and Heterogeneous Media (2012). 385–97. 10.3934/nhm.2012.7.385Modeling International Crisis Synchronization in the World Trade WebNhm

41.

MotterAEZhouCKurthsJ. Network Synchronization, Diffusion, and the Paradox of Heterogeneity. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys (2005) 71:016116. 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.016116

42.

SchellingTC. Dynamic Models of Segregation†. J Math Sociol (1971) 1:143–86. 10.1080/0022250x.1971.9989794

43.

FujitaM. Urban Economic Theory. Cambridge University Press (1989).

44.

ZhangJ. A Dynamic Model of Residential Segregation. J Math Sociol (2004) 28:147–70. 10.1080/00222500490480202

45.

ClarkWAV. Changing Residential Preferences across Income, Education, and Age. Urban Aff Rev (2009) 44:334–55. 10.1177/1078087408321497

46.

ZhangJ. Tipping and Residential Segregation: a Unified Schelling Model*. J Reg Sci (2011) 51:167–93. 10.1111/j.1467-9787.2010.00671.x

47.

DeLucaSGarbodenPMERosenblattP. Segregating Shelter. Annals Am Acad Polit Soc Sci (2013) 647:268–99. 10.1177/0002716213479310

49.

AdelmanRM. Neighborhood Opportunities, Race, and Class: The Black Middle Class and Residential Segregation. City & Community (2004) 3:43–63. 10.1111/j.1535-6841.2004.00066.x

50.

ThomasMMoyeR. Race, Class, and Gender and the Impact of Racial Segregation on Black-white Income Inequality. Sociol Race Ethn (2015) 1:490–502. 10.1177/2332649215581665

51.

FloridaRMellanderC. Segregated City: The Geography of Economic Segregation in America’s Metros. Martin Prosperity Institute (2015).

52.

HartiganJAWongMA. Algorithm as 136: A K-Means Clustering Algorithm. Appl Stat (1979) 28:100–8. 10.2307/2346830

53.

LikasAVlassisNJ. VerbeekJ. The Global K-Means Clustering Algorithm. Pattern Recognition (2003) 36:451–61. 10.1016/s0031-3203(02)00060-2

54.

MoranPAP. The Interpretation of Statistical Maps. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Methodological) (1948) 10:243–51. 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1948.tb00012.x

55.

FotheringhamASWongDWS. The Modifiable Areal Unit Problem in Multivariate Statistical Analysis. Environ Plan A (1991) 23:1025–44. 10.1068/a231025

56.

XuYBelyiASantiPRattiC. Quantifying Segregation in an Integrated Urban Physical-Social Space. J R Soc Interf (2019) 16:20190536. 10.1098/rsif.2019.0536

57.

TóthGWachsJDi ClementeRÁJSágváriBKertészJet alInequality Is Rising where Social Network Segregation Interacts with Urban Topology. Nat Commun (2021) 12:1–9. 10.1038/s41467-021-21465-0

58.

BokányiEJuhászSKarsaiMLengyelB. Universal Patterns of Long-Distance Commuting and Social Assortativity in Cities. Scientific Rep (2021) 11:1–10. 10.1038/s41598-021-00416-1

59.

MoroECalacciDDongXPentlandA. Mobility Patterns Are Associated with Experienced Income Segregation in Large Us Cities. Nat Commun (2021) 12:4633–10. 10.1038/s41467-021-24899-8

60.

MansonSSchroederJRiperDVRugglesS. IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 14.0 [Database]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS (2019). [Dataset]. 10.18128/D050.V14.0

Summary

Keywords

urban segregation, spatial heterogeneity, synchronization, phase-oscillators, diffusion

Citation

Bassolas A, Gómez S and Arenas A (2022) Diffusion and Synchronization Dynamics Reveal the Multi-Scale Patterns of Spatial Segregation. Front. Phys. 10:833426. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2022.833426

Received

11 December 2021

Accepted

04 April 2022

Published

25 April 2022

Volume

10 - 2022

Edited by

Haroldo V. Ribeiro, State University of Maringá, Brazil

Reviewed by

Zoltan Neda, Babeș-Bolyai University, Romania

Matjaž Perc, University of Maribor, Slovenia

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Bassolas, Gómez and Arenas.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aleix Bassolas, aleix.bassolas@gmail.com

This article was submitted to Social Physics, a section of the journal Frontiers in Physics

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.