Abstract

The main driven force of the electronic nematic phase in iron-based superconductors is still under debate. Here, we report a comprehensive study on the nematic fluctuations in a non-superconducting iron pnictide system BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2 by electronic transport, angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES), and inelastic neutron scattering (INS) measurements. Previous neutron diffraction and transport measurements suggested that the collinear antiferromagnetism persists to x = 0.8, with similar Néel temperature TN and structural transition temperature Ts around 32 K, but the charge carriers change from electron type to hole type around x = 0.5. In this study, we have found that the in-plane resistivity anisotropy also highly depends on the Cr dopings and the type of charge carriers. While ARPES measurements suggest possibly weak orbital anisotropy onset near Ts for both x = 0.05 and x = 0.5 compounds, INS experiments reveal clearly different onset temperatures of low-energy spin excitation anisotropy, which is likely related to the energy scale of spin nematicity. These results suggest that the interplay between the local spins on Fe atoms and the itinerant electrons on Fermi surfaces is crucial to the nematic fluctuations of iron pnictides, where the orbital degree of freedom may behave differently from the spin degree of freedom, and the transport properties are intimately related to the spin dynamics.

1 Introduction

Electronic nematic phase breaks the rotational symmetry but preserves the translational symmetry of the underlying lattice in correlated materials [1–4]. In iron-based superconductors, the nematic order associated with a tetragonal-to-orthorhombic structural transition at temperature Ts acts as a precursor of the magnetic order below TN and the superconducting state below Tc [5–10]. The nematic fluctuations can be described by the electronic nematic susceptibility, which is defined as the susceptibility of electronic anisotropy to the uniaxial in-plane strain [11]. Divergent nematic susceptibility upon approaching Ts from high temperature is revealed by the elastoresistance and elastic moduli measurements, suggesting nematic fluctuations well above Ts [12–16]. The nematic fluctuations commonly exist in iron-based superconductors and are even present in compounds with tetragonal crystal symmetry without any static nematic order [17]. Accumulating evidence suggests that the optimal superconductivity with maximum Tc usually occurs near a nematic quantum critical point where the nematic fluctuations are the strongest [18–29]. However, the charge, spin, and orbital degrees of freedom are always intertwined in the presence of nematic fluctuations [30–39], giving a twofold rotational (C2) symmetry in many physical properties [5–11, 40–44] including anisotropic in-plane electronic resistivity and optical conductivity [45–51], lifting of degeneracy between dxz/dyz orbitals [52–58], anisotropic spin excitations at low energies [59–63], phonon-energy split in lattice dynamics [64, 65], and splitting of the Knight shift [66, 67]. In addition, it has been proposed that the local anisotropic impurity scattering of chemical dopants likely induces the twofold symmetry in the transport properties [68–70]. Such complex cases make it is difficult to clarify the main driven force of nematic phase by a single experimental probe.

Our previous works suggest that the Cr substitution is an effective way both to suppress the superconductivity and to tune the magnetism in iron-based superconductors [27, 71–73]. Specifically, in the BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2 system, by continuously doping Cr to the optimally superconducting compound BaFe1.9Ni0.1As2 with Tc = 20 K, the superconductivity is quickly suppressed above x = 0.05, but the magnetic transition temperature TN and the structural transition temperature Ts remain between 30 and 35 K as shown by neutron diffraction results on naturally twinned samples (Figure 1A). Moreover, the effective moment m is significantly enhanced first and then suppressed for dopings higher than x = 0.5, where the charge carriers change from electron type to hole type as shown by the sign of Hall and Seebeck coefficients [73]. These make BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2 a rare example to separately tune the magnetically ordered temperature TN by the local spin interactions and the magnetically ordered strength by the scattering of itinerant electrons on Fermi surfaces, respectively. The extra holes introduced by Cr substitutions compensate the electron doping thus may drive those non-superconducting compounds to a half-filled Mott insulator similar to the parent compounds of cuprate and nickelate superconductors [74–79]. It would be interesting to monitor the evolution of the nematic fluctuations starting from a metallic state toward to a localized insulating state [79–81], especially on the detwinned samples (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1

(Color online) Phase diagram and in-plane resistivity anisotropy of BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2. (A) The PM, AF, and SC mark the region of paramagnetic, antiferromagnetic, and superconducting phases defined by Ts, TN, and Tc, respectively. Here, Ts and TN were measured by neutron diffraction in our previous work on the naturally twinned samples [73]. (B) The gradient color maps the in-plane resistivity anisotropy δρ measured on detwinned samples. The vertical dashed line divides the regions for electron-type and hole-type charge carriers as determined by the sign of Hall and Seebeck coefficients [73].

In this paper, we further report a multi-probe study on the nematic fluctuations in the non-superconducting compounds BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2 (x = 0.05 ∼ 0.8) by electronic transport, angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES), and inelastic neutron scattering (INS) measurements. The in-plane resistivity anisotropy measured in the detwinned samples under uniaxial pressure shows a strong dependence on the Cr content with a clear sign change above x = 0.6. By focusing on two compounds with x = 0.05 and 0.5, ARPES measurements suggest possible band shifts induced by orbital anisotropy near Ts/TN for both dopings, but INS experiments reveal clearly different behaviors on the spin nematicity. The onset temperature of low-energy spin excitation anisotropy between Q = (1, 0, 1) and Q = (0, 1, 1) for x = 0.05 is about 110 K, but for x = 0.5, it is much lower, only about 35 K near the magnetic transition. Such temperature dependence of spin nematicity is consistent with the results of in-plane resistivity anisotropy. At high energies, the spin nematicity for x = 0.05 extends to about 120 meV, much larger than the case for x = 0.5 (about 40 meV), suggesting a possible linear correlation between the highest energy scale and the onset temperature of spin nematicity. Therefore, the nematic behaviors in iron pnictides are highly related to the interplay between local moments and itinerant electrons. While the C2-type anisotropies in spin excitations and in-plane resistivity are strongly correlated with each other [60], the orbital anisotropy induced band splitting may behave differently as affected by the complex Fermi surface topology [82–91].

2 Experiment Details

High-quality single crystals of BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2 were grown by the self-flux method [71–73, 92–95]; the characterization results of our sample can be found in previous reports [71, 73]. The crystalline directions of our sample were determined by an X-ray Laue camera (Photonic Sciences) in the backscattering mode with incident beam along the c − axis. After that, the crystals were cut into rectangle shapes (typical sizes: 1 mm × 2 mm) by a wire saw under the directions [1, 0, 0] × [0, 1, 0] in orthorhombic lattice notation (a = b = 5.6 Å). By applying a uniaxial pressure around 10 MPa, the crystal can be fully detwinned at low temperature, where the direction of pressure was defined as the b direction, and the pressure-free direction was defined as the a direction [60–63, 96–99]. The in-plane resistivity (ρa,b) was measured by the standard four-probe method with the Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS) from Quantum Design. To compare the temperature dependence of resistivity at different directions, we normalized the resistivity ρa,b(T) data at 150 K for each sample. The in-plane resistivity anisotropy was defined by δρ = (ρb − ρa)/(ρb + ρa) same as other literature [45–47].

ARPES experiments were performed at beamline 10.0.1 of the Advanced Light Source and beamline 5-4 of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light source with R4000 electron analyzers. The angular resolution was 0.3°, and the total energy resolution was 15 meV. All samples were cleaved in-situ at 10 K and measured in ultra-high vacuum with a base pressure lower than 4 × 10–11 Torr. We note that we used twinned samples without uniaxial pressure for the ARPES experiments. INS experiments were carried out at two thermal triple-axis spectrometers: PUMA at Heinz Maier-Leibnitz Zentrum (MLZ) [100], Germany, and TAIPAN at the Australian Centre for Neutron Scattering (ACNS) [101], ANSTO, Australia. The wave vector Q at (qx, qy, qz) was defined as (H, K, L) = (qxa/2π, qyb/2π, qzc/2π) in reciprocal lattice units (r.l.u.) using the orthorhombic lattice parameters a ≈ b = 5.6 Å and c ≈ 13 Å. All measurements were done with fixed final energy Ef = 14.8 meV, and a double focusing monochromator and analyzer using pyrolytic graphite crystals. To gain a better signal-noise ratio, eight pieces of rectangularly cut crystals (typical sizes: 7 mm × 8 mm × 0.5 mm) were assembled in a detwinned device made by aluminum and springy gaskets [60–63]. To reach both Q = (1, 0, 1) and Q = (0, 1, 1), the sample holder was designed to easily rotate by 90°, thus the scattering plane can switch from [H, 0, 0] × [0, 0, L] to [0, K, 0] × [0, 0, L]. The total mass of the crystals used in INS experiments was about 2 g from each sample set of x = 0.05 and x = 0.5. Time-of-flight neutron scattering experiments were carried out on the same sample sets at 4SEASONS spectrometer (BL-01) at J-PARC [102, 103], Tokai, Japan, with multiple incident energies Ei = 250, 73, 34, 20 meV, ki parallel to the c axis, and chopper frequency f = 250 Hz. The data were only corrected by the efficiency of detectors from the incoherent scattering of vanadium with white beam. As we were comparing two samples with similar mass under the same measured conditions at the same spectrometer, it was not necessary to do the vanadium normalization with mono-beam. The data were analyzed by the Utsusemi and MSlice software packages [104, 105].

3 Results and Discussions

We first present the resistivity results in Figures 1-3. Apparently, the in-plane resistivity anisotropy show a strong dependence on the Cr doping level. In the Cr free sample BaFe1.9Ni0.1As2, the difference between ρa and ρb presents above the superconducting transition temperature Tc = 20 K, where ρa is metallic and ρb is semiconducting-like with an upturn at low temperature (namely, ρa < ρb) (Figure 2A). The superconductivity is completely suppressed at x = 0.05, and there is a dramatic difference between ρa and ρb with an anisotropy δρ persisting to about T = 110 K (Figure 2B). By further increasing Cr doping, both ρa and ρb become semiconducting-like even insulating-like above x = 0.1, and the resistivity anisotropy gets weaker and weaker, until it nearly disappears at x = 0.5 and 0.6 compounds (Figure 2C–H). For those high doping compounds x = 0.7 and 0.8, it seems that δρ changes sign with ρa > ρb at low temperatures (Figure 2I,J). To clearly compare the resistivity anisotropy upon Cr doping, we plot δρ as gradient color mapping in Figure 1B and show its detailed temperature dependence in Figure 3. Interestingly, the sign of δρ is also related to the type of charge carriers. δρ keeps strong and positive in the electron-type compounds but changes to negative and weak in the hole-type compounds (Figure 1B and Figure 3B). This is consistent with the results in the electron doped BaFe2−x(Ni, Co)xAs2 and the hole doped Ba1−xKxFe2As2, Ca1−xNaxFe2As2, and BaFe2−xCrxAs2 systems [45–48, 106–109]. However, in those cases, the onset temperature of δρ decreases with the structural transition temperature Ts when increasing the doping level from the non-superconducting parent compounds to optimally doped superconducting compounds. Here, in the BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2 system, both TN and Ts are actually within the range 32 ∼ 35 K for all probed dopings [73], but the onset temperature of δρ still extends to high temperatures, and it is then strongly suppressed by Cr doping (Figure 3A). In those hole-type compounds, δρ shows a peak feature (for x = 0.5 and 0.6) or a kink (for x = 0.7 and 0.8) responding to the magnetic and structural transitions (Figure 3B). The non-monotonic behavior of δρ may come from the competition between the scattering from hole bands and electron bands, and similar behaviors were observed in the nematic susceptiblity of the Cr doped BaFe2(As1−xPx)2 system [27].

FIGURE 2

(Color online) In-plane resistivity anisotropy of BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2 under uniaxial pressure. Here, ρb is the in-plane resistivity along the direction of uniaxial pressure, and ρa is the in-plane resistivity perpendicular to the direction of uniaxial pressure. For easy comparison, each curve is normalized by its resistivity at 150 K, and there is no resistivity anisotropy above this temperature.

FIGURE 3

(Color online) Temperature dependence of the in-plane resistivity anisotropy δρ from x = 0.05 to 0.8. (A) In electron-type compounds, δρ gets weaker but keeps positive when increasing Cr doping. (B) In hole-type compounds, δρ is very weak and becomes negative when x ≥0.7.

Next, we focus on the electronic structure and the spin excitations in two typical dopings x = 0.05 with TN = 32 K and x = 0.5 with TN = 35 K. The Fermi surface topology and band structure measured by ARPES on naturally twinned samples are shown in Figure 4. From the Fermi surface mapping in Figure 4A,B, we can find typical hole pockets around the zone center Γ point. Near the X point, an electron pocket is observed for x = 0.05. For x = 0.5, however, the Fermi surface resembles that of the hole-doped (Ba,K)Fe2As2 [53]. This is due to the hole doping introduced by the Cr substitution, which also introduces disorder directly in the Fe-planes, thus resulting in spectral features that appear broad [82]. Figure 4C,D show the second energy derivatives of the spectral images along the high symmetry direction (Γ-X). Larger hole pockets can indeed be seen for x = 0.5 compared to x = 0.05. As has been demonstrated previously on BaFe2As2, NaFeAs, and FeSe, the onset of Ts is associated with the onset of an observed anisotropic shift of the dxz and dyz orbital-dominated bands where the dxz band shifts down and the dyz band shifts up [52–56]. This shift is most prominently observed near the X point of the Brillouin zone. Moreover, such band splitting as measured on uniaxially strained crystals can be observed above Ts in the presence of this symmetry-breaking field. On a structurally twinned crystal, the anisotropic band shifts would appear in the form of a band splitting due to domain mixing. While we do not observe clearly the band splitting as shown in Figure 4C,D, we can clearly observe the lower branch with dominant intensity that shifts with temperature. This can be understood as the lower dxz band. We can fit the energy position of the band extracted from the X point and plot as a function of temperature. The temperature evolution clearly identifies a temperature scale associated with an onset of the band shift [53–55]. As shown in Figure 4E,F, the X band shifts at low temperature T ≈ 25 K for x = 0.05 and T ≈ 45 K for x = 0.5, respectively, closing to their structural or magnetic transition temperatures. We do note that while we cannot conclusively state that this represents the orbital anisotropy, the behavior we observe here on these twinned crystals is consistent with the expectation of the onset of orbital anisotropy [52, 57, 62]. We note here that the observed onset temperature of band splitting is close to the Ts (or TN), in contrast to the much higher onset in the resistivity anisotropy shown in Figure 3 measured on a strained crystal.

FIGURE 4

(Color online) ARPES results on x = 0.05 (left) and x = 0.5 (right) compounds. (A)–(B) The measured Fermi surfaces around the Γ and X points. (C)–(D) Band dispersions along the high symmetry direction Γ-X obtained from the second derivatives in the energy direction. (E)–(F) Temperature dependence of the fitted band position from the X point. All dashed lines are guides for eyes.

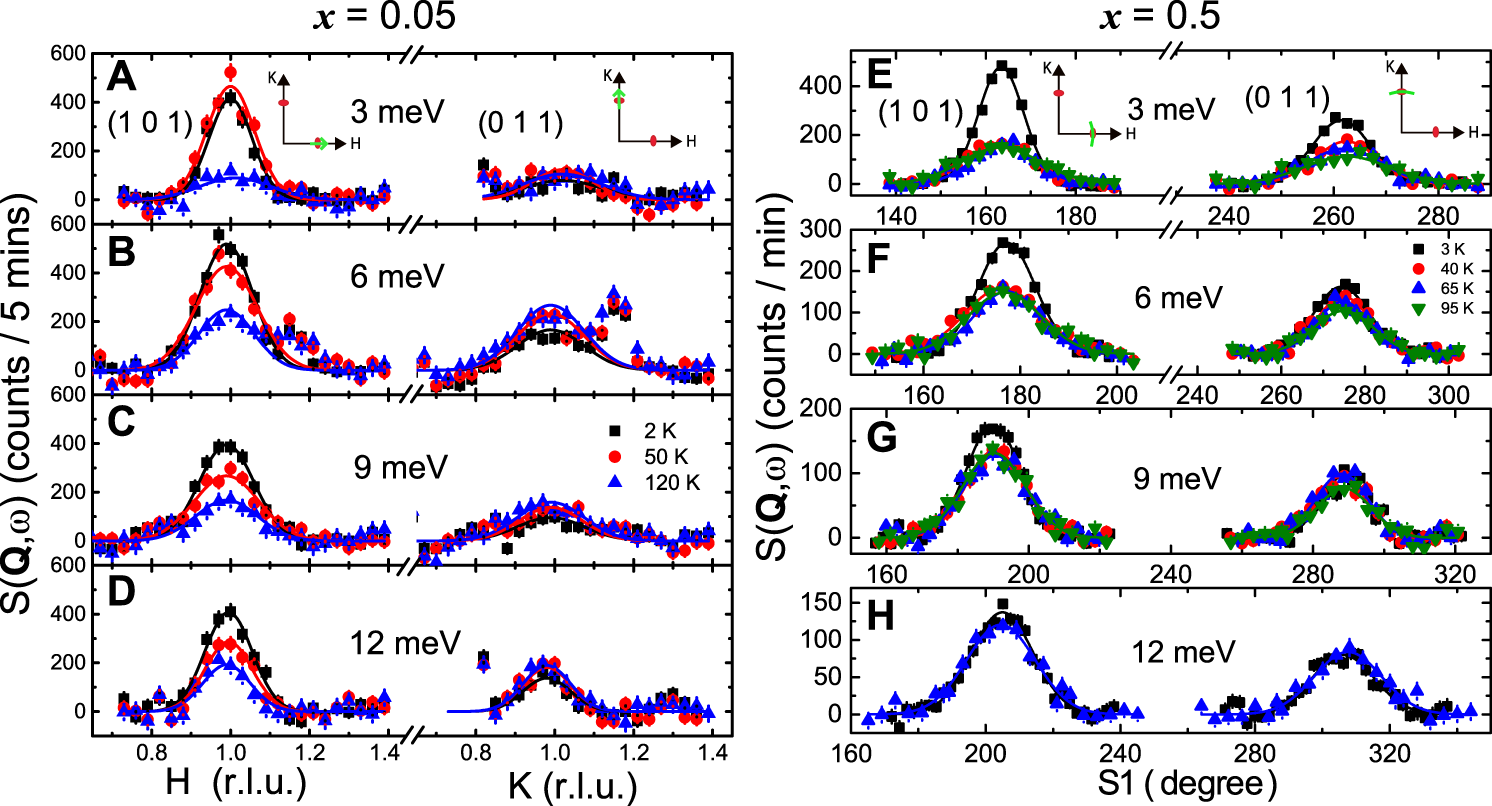

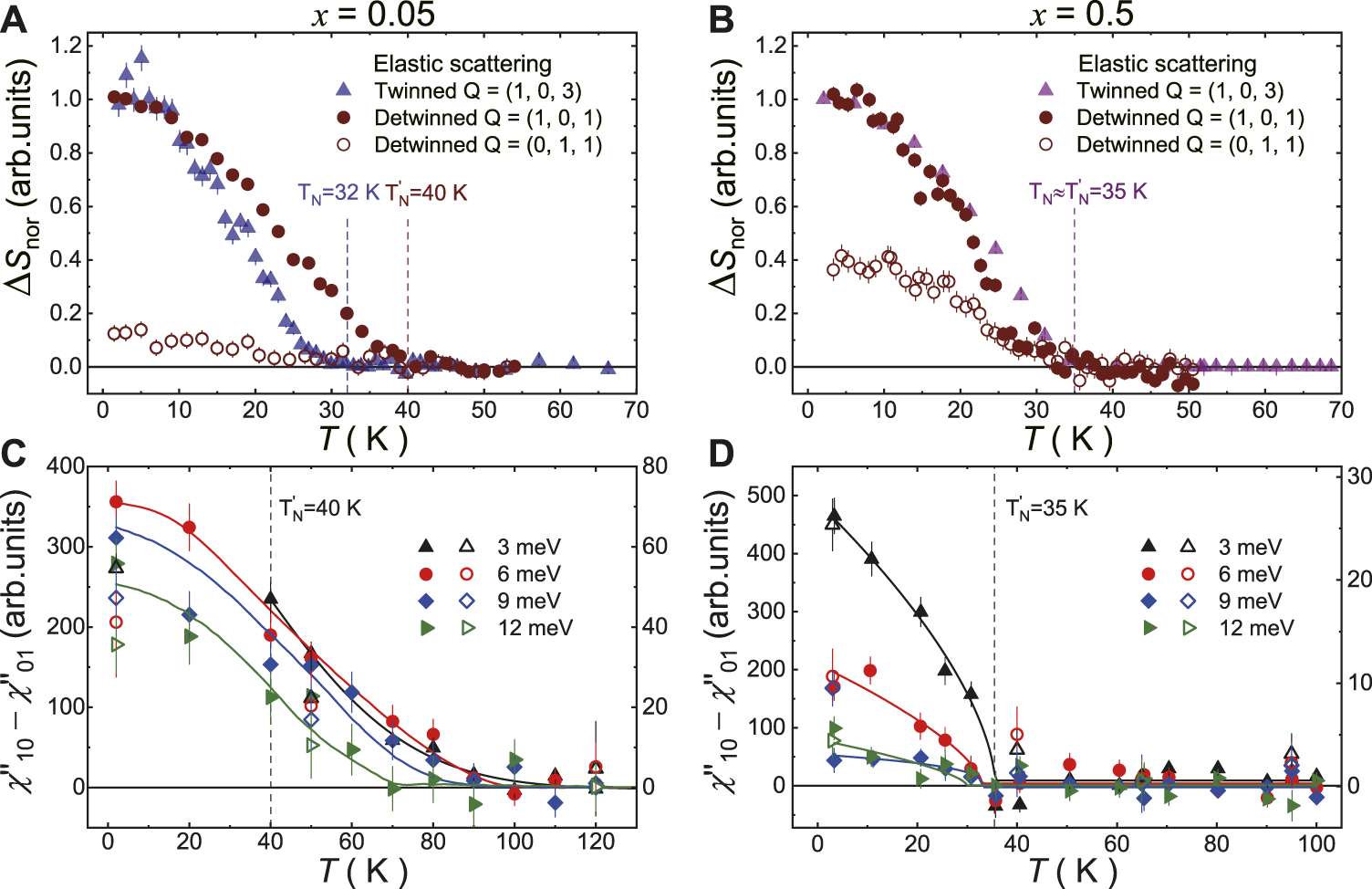

We then turn to search the connection between the resistivity anisotropy and the spin excitation anisotropy. The first evidence of spin nematicity was observed in BaFe2−xNixAs2 (x = 0, 0.065, 0.085, 0.10, 0.12) [60–63], where BaFe1.9Ni0.1As2 is the starting compound of this study. Low-energy spin excitations are measured on the detwinned BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2 (x = 0.05 and 0.5) samples by INS experiments using two triple-axis spectrometers. The results of constant-energy scans at E = 3, 6, 9, and 12 meV are summarized in Figure 5. With convenient design of the detwinned device and sample holder, we can easily perform constant-energy scans (Q − scans) either along the [H, 0, 1] or [0, K, 1] direction after rotating the whole sample set by 90°. For the x = 0.5 sample, we instead do the S1 rocking scans at Q = (1, 0, 1) and (0, 1, 1). It should be noticed that the Néel temperature TN is slightly enhanced by the applied uniaxial pressure in the x = 0.05 sample from 32 to 40 K (so does Ts) but does not change for the x = 0.5 sample ( K) (Figure 6A,B). Such an effect has been detected in the BaFe2−x(Ni, Co)xAs2 system [110]. The detwinned ratio can be estimated by comparing the integrated intensities of magnetic Bragg peak between Q = (1, 0, 1) and Q = (0, 1, 1) positions, which is about 10:1 for the x = 0.05 samples, and 4:1 for the x = 0.5 samples, respectively. Such a large ratio means successful detwin for both sample sets. At the first glance, it is very clear for the difference of the spin excitations between Q = (1, 0, 1) and Q = (0, 1, 1) especially at low temperatures, which could be attributed to the spin Ising-nematic correlations (so-called spin nematicity). After warming up to high temperatures, the spin excitations at Q = (1, 0, 1) decrease and become nearly identical to those at Q = (0, 1, 1). The nematic order parameter for the spin system can be approximately represented by , in which (or ) is the local spin susceptibility at Q = (1, 0, 1) (or Q = (0, 1, 1)). Figure 6C,D show the temperature dependence of for both compounds, where the Bose population factor is already corrected. We also plot the data (open symbols) obtained from the integrated intensity of those Q − scans in Figure 5. For the x = 0.05 compound, the spin nematicity decreases slightly upon increasing energy and terminates well above K (Figure 6C)73. For the lowest energy we measured (3 meV), the onset temperature of spin nematicity is about 110 K, similar to the in-plane resistivity anisotropy in Figure 3A. The results for x = 0.5 compound show markedly differences, where quickly decreases with both energy and temperature, and the onset temperature is around K (Figure 6D). No spin anisotropy can be detected above 40 K for both Q − scans and energy scans, and this is also consistent with the very weak in-plane resistivity anisotropy for x = 0.5 (Figure 3B). The spin nematic theory predicts that the nematic fluctuations enhance both the intensity and the correlation length of spin excitations at (π, 0) but suppress those at (0, π) even above Ts. This was firstly testified in the detwinned BaFe1.935Ni0.065As2 and can also be seen here in Figure 561. Although the peak intensities at Q = (1, 0, 1) seem stronger than those at Q = (0, 1, 1) in Figure 5G,H, the peak width is smaller, and the integrated intensity of the Q-scans are closed to each other. The above results of spin nematicity in BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2 (x = 0.05 and 0.5) resemble to those in BaFe2−xNixAs2, where spin excitations at low energies change from C4 to C2 symmetry in the tetragonal phase at temperatures approximately corresponding to the onset of the in-plane resistivity anisotropy.

FIGURE 5

(Color online) Inelastic neutron scattering results on the spin excitations of uniaxially detwinned samples for x = 0.05 (left) and x = 0.5 (right) compounds measured by two triple-axis spectrometers TAIPAN and PUMA. We compared the constant-energy scans (Q −scans along [H,0,1] or [0, K,1], S1 rocking scans at Q = (1,0,1) or (0, 1, 1)) for E = 3, 6, 9, 12 meV, respectively. All data are corrected by a linearly Q −dependent background, and the solid lines are Gaussian fittings. The spurious signals in 6 meV data are ignored.

FIGURE 6

(Color online) The order parameter of antiferromagnetism and spin nematicity for x = 0.05 and x =0.5 compounds. (A) and (B) The magnetic order parameters measured at Q = (1,0,3) on twinned samples, Q = (1,0,1) and Q = (0,1,1) on detwinned samples by elastic neutron scattering. All data are subtracted by the normal state background and normalized by the intensity at base temperature for Q = (1,0,3) or Q = (1,0,1). (C) and (D) Spin nematicity measured by inelastic neutron scattering. The solid symbols are the differences of local susceptibility χ′′ between Q = (1,0,1) and Q = (0,1,1) (left y-axis), and the open symbols are similar but obtained by integrating the constant-energy scans in Figure 5 corrected by the Bose population factor (right y-axis). The vertical dash lines mark the magnetic transition temperature TN on twinned samples and on detwinned samples. All solid lines are guides to eyes.

Moreover, INS experiments on detwinned BaFe2As2 and BaFe1.9Ni0.1As2 suggest that the spin anisotropy can persist to very high energy [62, 63], even in the later case the splitting of the dxz and dyz bands nearly vanishes [57]. To quantitatively determine the energy dependence of spin excitation anisotropy, we have performed time-of-flight INS experiments on the uniaxially detwinned BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2 (x = 0.05 and 0.5), and the results are shown in Figures 7, 8. It should be noted that for such experiments, the energy transfer is always coupled with L due to ki ∥ c [102, 103]. The two-dimensional (2D) energy slices and one-dimensional (1D) cuts along [H, 0] and [0, K] at various energies are presented in Figure 7. Indeed, the spin excitations are twofold symmetric below 100 meV for both compounds. The spin excitations at E = 3 meV, Q = (0, ±1) are very weak in the x = 0.05 compound, then continuously increase upon energy, and become nearly the same as Q = (±1, 0) around 110 meV. For the x = 0.5 compound, although the spin excitations at Q = (0, ±1) can be initially observed at E = 3 meV, the spin anisotropy still exists at 15 meV and then disappears above 42 meV. To further compare the spin excitations in both compounds, we have calculated the total spin fluctuations and the spin nematicity from the integrated intensity marked by the dashed diamonds in Figure 7D,L. In principle, the local dynamic susceptibility χ′′ can be estimated from the integration outcome of the spin excitations within one Brillouin zone, and here χ′′ can be simply calculated through dividing the integration signal in the Q = (0, 0) (1, 1), (2, 0), (1, −1) boxes, giving the diamond shape integration zone [8]. The total spin susceptibility in the x = 0.5 compound is stronger than that in x = 0.05 but decays much quickly with energy (Figure 8A,C). The spin nematicity apparently has different energy scales for two compounds, where it is about 120 meV for x = 0.05 but only 40 meV for x = 0.5, respectively. The energy scale of in the superconducting compound BaFe1.9Ni0.1As2 is 60 meV [62], and for the parent compound BaFe2As2, it is about 200 meV up to the band top of the spin waves [63]. These facts lead to a possible linear correlation between the highest energy and the onset temperature of spin nematicity at low energy (inset of Figure 8D). Within the measured energy range, both and can be fit with a power-law dependence on the energy, ∼ A/Eα, where the amplitude A and exponent α are listed in each panel of Figure 8. Indeed, the larger value of α for x = 0.5 in comparison to that for x = 0.05 suggests faster decay with energy for both the spin fluctuations and the spin nematicity. Similar fitting on the results of BaFe1.9Ni0.1As2 gives parameters in between them [62]. Although the low energy data below 10 meV may be affected by the L-modulation of spin excitations, and by the superconductivity in BaFe1.9Ni0.1As2, the similar quantum critical behavior both for and in these three compounds is expected by the Ising-nematic scenario [60–63].

FIGURE 7

(Color online) Inelastic neutron scattering results on the spin excitations of the uniaxially detwinned samples for x = 0.05 (left) and x = 0.5 (right) compounds measured at T = 5 K by time-of-flight spectrometer 4SEASONS. All data are presented in both 2D slices for the [H, K] plane and 1D cuts along [H,0] or [0, K] at typical energy windows E = 3±1,15±2,42±4,110±10 meV. The solid lines are Gaussian fittings guiding for eyes, which are not shown in panel (P) due to poor data quality. The dashed diamonds in panel (D) and (L) illustrate the integrated Brillouin zone for spin excitations around Q = (1,0) and Q = (0,1), respectively.

FIGURE 8

(Color online) Energy dependence of the total spin fluctuations and the spin nematicity of uniaxially detwinned samples for x =0.05 (left) and x =0.5 (right) compounds. Different symbols correspond to different incident energies in the measurements. Both of and can be fitted with a power-law dependence on the energy, ∼ A/Eα, where the amplitude A and exponent α are listed in each panel. The inset of panel (D) shows the correlation between the highest energy and the onset temperature at low energy of .

In our previous neutron diffraction results on the BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2 system, the Cr dopings have limited effects on the magnetically ordered temperature TN but significantly enhance the effective ordered moment m by reaching a maximum value at x = 0.5 [73]. The Néel temperature TN is mostly determined by the local magnetic coupling related to the local FeAs4 tetrahedron structure. The evolution of ordered moment probably induced by the changes of the density of states and the orbital angular momentum from itinerant electrons on the Fermi surfaces. The Cr doping introduces both local distortion on the lattices and hole doping on the Fermi pockets, yielding a non-monotonic change of the conductivity of charge carriers. As shown in Figure 2, the low-temperature upturn of resistivity is enhanced by Cr doping first but then weakens in those hole-type compounds. Among these dopings, x = 0.5 has the most insulating-like behavior, and thus strongly localized charge carriers and maximum ordered moment, but its spin nematicity quickly drops down for both the temperature and energy dependence. In contrast to the magnetically ordered strength, both the structural transition temperature Ts and the lattice orthorhombicity δ = (a − b)/(a + b) are nearly Cr doping independent [73]. This means the static nematic order is also nearly Cr independent in this system, as opposed to the case for dynamic nematic fluctuations.

The nature of the iron-based superconductor can be theoretically described as a magnetic Hund’s metal, in which the strong interplay between the local spins on Fe atoms and the itinerant electrons on Fermi surfaces gives correlated electronic states [80, 81]. Indeed, time-of-flight INS experiments on the detwinned BaFe2As2 suggest that the spin waves in the parent compound are preferably described by a multi-orbital Hubbard–Hund model based on the itinerant picture with moderate electronic correlation effects, instead of a Heisenberg model with effective exchange couplings from local spins. Upon warming up to high temperatures, the intensities of spin excitation anisotropy decrease gradually with increasing energy and finally cut off at an energy away from the band top of spin waves [63]. Therefore, the energy scale of spin nematicity sets an upper limit for the characteristic temperature for the nematic spin correlations, as well as the onset temperature of resistivity anisotropy. Here, by adding up the results on the in-plane anisotropies of resistivity, orbital energy, and spin excitations in BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2, they clearly suggest that the electronic nematicity is intimately related to the spin dynamics, which seems consistent with Hund’s metal picture. Specifically, by doping Cr to suppress the superconductivity in BaFe1.9Ni0.1As2, it makes the charge carriers initially localized with enhanced electron correlations [73], which may enhance the electronic correlations by increasing the intra- and inter-orbital onsite repulsion U as well as Hund’s coupling JH [63], and thus gives rise to stronger spin excitations and larger spin anisotropy in the Cr doping x = 0.05 compound. Another effect is the lifting up of dyz and dxy along the Γ-X direction to the Fermi level, which primarily contributes to the effective moments [80]. The orbital-weight redistribution triggered by the spin order suggests that the orbital degree of freedom is coupled to the spin degree of freedom [111]. By further increasing Cr doping to x = 0.5, the localization effect is so strong that the electron system becomes insulating at low temperature. In this case, the itinerant picture based on Hund’s metal may not be applicable anymore. The low density of itinerant electrons weakens the nematic fluctuations and probably limits them inside the magnetically ordered state. In either case for x = 0.05 or x = 0.5, the band splitting does not directly correspond to the spin nematic correlations but only present below the nematic ordered temperature. This may attribute to the weak spin–orbit coupling in this system, as the spin anisotropy in spin space can only present at very low energies [59]. In addition, our results can rule out the picture of local impurity scattering driven nematicity since the impurity scattering from Cr substitutions is certainly stronger in the x = 0.5 compound, but it does not promote the nematic fluctuations.

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, we have extensively studied the in-plane resistivity anisotropy, orbital ordering, and spin nematicity in a non-superconducting BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2 system. We have found that the Cr doping strongly affect the anisotropy of resistivity and spin excitations along with the itinerancy of charge carriers. While the onset temperatures of resistivity anisotropy and spin nematicity are similar and correlated with the energy scale of spin anisotropy, the orbital anisotropy shows an onset temperature irrelevant to them. These results suggest that the electronic correlations from the interplay between local moments and itinerant electrons are crucial to understand the nematic fluctuations, thus inspiring the quest for the driven force of the electronic nematic phase in iron-pnictide superconductors.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the datasets are currently private. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to HL, hqluo@iphy.ac.cn.

Author contributions

HL and DG proposed and designed the research. DG, TX, WZ, and RZ contributed in sample growth and resistivity measurements. MY, MW, S-KM, MH, DL, and RB contributed to the ARPES measurements. DG and HL carried out the neutron scattering experiments with SD, GD, XL, JP, KI, and KK. DG, HL, SL, and PD analyzed the data. HL, DG, and MY wrote the paper. All authors participated in discussion and comment on the paper.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2018YFA0704200, No. 2017YFA0303100, and No. 2017YFA0302900), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 11822411, No. 11961160699, and No. 12061130200), the Strategic Priority Research Program (B) of the CAS (Grant No. XDB25000000 and No. XDB07020300), and the KC Wong Education Foundation (GJTD-2020-01). HL is grateful for the support from the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of CAS (Grant No. Y202001) and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. JQ19002). MW is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 11904414 and No.12174454), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2021B1515120015), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2019YFA0705702). The work at University of California, Berkeley, and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division under Contract No. DE-AC02-05-CH11231 within the Quantum Materials Program (KC2202) and the Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The ARPES work at Rice University was supported by the Robert A. Welch Foundation (Grant No. C-2024 (MY)). The neutron scattering work at Rice University was supported by the U.S. DOE, BES (Grant No. DE-SC0012311) and by the Robert A. Welch Foundation (Grant No. C-1839 (PD)).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the helpful discussion with Xingye Lu at Beijing Normal University and Yu Song at Zhejiang University. The neutron scattering experiments in this work are performed at thermal triple-axis spectrometer PUMA at Heinz Maier-Leibnitz Zentrum (MLZ), Germany, thermal triple-axis spectrometer TAIPAN at Australian Centre for Neutron Scattering (ACNS), Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO), Australia (Proposal No. P4263), and time-of-flight Fermi-chopper spectrometer 4SEASONS (BL-01) at the Materials and Life Science Experimental Facility of J-PARC (Proposal Nos. 2015A0005, 2016A0169). ARPES measurements were performed at the Advanced Light Source and the Stanford Radiation Lightsource, which are both operated by the Office of Basic Energy Sciences, U.S. DOE.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

OganesyanVKivelsonSAFradkinE. Quantum Theory of a Nematic Fermi Fluid. Phys Rev B (2001) 64:195109. 10.1103/physrevb.64.195109

2.

FradkinEKivelsonSA. Electron Nematic Phases Proliferate. Science (2010) 327:155–6. 10.1126/science.1183464

3.

FradkinEKivelsonSALawlerMJEisensteinJPMackenzieAP. Nematic Fermi Fluids in Condensed Matter Physics. Annu Rev Condens Matter Phys (2010) 1:153–78. 10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-070909-103925

4.

WangWLuoJWangCYangJKodamaYZhouRet alMicroscopic Evidence for the Intra-unit-cell Electronic Nematicity inside the Pseudogap Phase in YBa2Cu4O8. Sci China Phys Mech Astron (2021) 64:237413. 10.1007/s11433-020-1615-y

5.

FernandesRMSchmalianJ. Manifestations of Nematic Degrees of Freedom in the Magnetic, Elastic, and Superconducting Properties of the Iron Pnictides. Supercond Sci Technol (2012) 25:084005. 10.1088/0953-2048/25/8/084005

6.

FernandesRMChubukovAV. Low-energy Microscopic Models for Iron-Based Superconductors: a Review. Rep Prog Phys (2017) 80:014503. 10.1088/1361-6633/80/1/014503

7.

ChenXDaiPFengDXiangTZhangF-C. Iron-based High Transition Temperature Superconductors. Nat Sci Rev (2014) 1:371–95. 10.1093/nsr/nwu007

8.

DaiP. Antiferromagnetic Order and Spin Dynamics in Iron-Based Superconductors. Rev Mod Phys (2015) 87:855–96. 10.1103/revmodphys.87.855

9.

SiQYuRAbrahamsE. High-temperature Superconductivity in Iron Pnictides and Chalcogenides. Nat Rev Mat (2016) 1:16017. 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.17

10.

Gong Dong-LiangDLuo Hui-QianH. Antiferromagnetic Order and Spin Dynamics in Iron-Based Superconductors. Acta Phys Sin (2018) 67:207407. 10.7498/aps.67.20181543

11.

BöhmerAEMeingastC. Electronic Nematic Susceptibility of Iron-Based Superconductors. Comptes Rendus Phys (2016) 17:90–112. 10.1016/j.crhy.2015.07.001

12.

ChuJ-HKuoH-HAnalytisJGFisherIR. Divergent Nematic Susceptibility in an Iron Arsenide Superconductor. Science (2012) 337:710–2. 10.1126/science.1221713

13.

KuoH-HFisherIR. Effect of Disorder on the Resistivity Anisotropy Near the Electronic Nematic Phase Transition in Pure and Electron-Doped BaFe2As2. Phys Rev Lett (2014) 112:227001. 10.1103/physrevlett.112.227001

14.

KuoH-HShapiroMCRiggsSCFisherIR. Measurement of the Elastoresistivity Coefficients of the Underdoped Iron Arsenide Ba(Fe0.975Co0.025)2As2. Phys Rev B (2013) 88:085113. 10.1103/physrevb.88.085113

15.

BöhmerAEBurgerPHardyFWolfTSchweissPFromknechtRet alNematic Susceptibility of Hole-Doped and Electron-Doped BaFe2As2 Iron-Based Superconductors from Shear Modulus Measurements. Phys Rev Lett (2014) 112:047001. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.047001

16.

GongDLiuZGuYXieTMaXLuoHet alNature of the Antiferromagnetic and Nematic Transitions in Sr1−xBaxFe1.97Ni0.03As2. Phys Rev B (2017) 96:104514. 10.1103/physrevb.96.104514

17.

BöhmerAEChenFMeierWRXuMDrachuckGMerzMet alEvolution of Nematic Fluctuations in CaK(Fe1−xNix)4As4 with Spin-Vortex Crystal Magnetic Order [Preprint] (2020). Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.13207.

18.

KuoH-HChuJ-HPalmstromJCKivelsonSAFisherIR. Ubiquitous Signatures of Nematic Quantum Criticality in Optimally Doped Fe-Based Superconductors. Science (2016) 352:958–62. 10.1126/science.aab0103

19.

YoshizawaMKimuraDChibaTSimayiSNakanishiYKihouKet alStructural Quantum Criticality and Superconductivity in Iron-Based Superconductor Ba(Fe1-x Cox)2As2. J Phys Soc Jpn (2012) 81:024604. 10.1143/jpsj.81.024604

20.

DaiJSiQZhuJ-XAbrahamsE. Iron Pnictides as a New Setting for Quantum Criticality. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2009) 106:4118–21. 10.1073/pnas.0900886106

21.

KasaharaSShiHJHashimotoKTonegawaSMizukamiYShibauchiTet alElectronic Nematicity above the Structural and Superconducting Transition in BaFe2(As1−xPx)2. Nature (2012) 486:382–5. 10.1038/nature11178

22.

ShibauchiTCarringtonAMatsudaY. A Quantum Critical Point Lying beneath the Superconducting Dome in Iron Pnictides. Annu Rev Condens Matter Phys (2014) 5:113–35. 10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-031113-133921

23.

LedererSSchattnerYBergEKivelsonSA. Superconductivity and Non-fermi Liquid Behavior Near a Nematic Quantum Critical Point. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2015) 114:4905–10. 10.1073/pnas.1620651114

24.

LuoHZhangRLaverMYamaniZWangMLuXet alCoexistence and Competition of the Short-Range Incommensurate Antiferromagnetic Order with the Superconducting State of BaFe2−xNixAs2. Phys Rev Lett (2012) 108:247002. 10.1103/physrevlett.108.247002

25.

LuXGretarssonHZhangRLiuXLuoHTianWet alAvoided Quantum Criticality and Magnetoelastic Coupling in BaFe2−xNixAs2. Phys Rev Lett (2013) 110:257001. 10.1103/physrevlett.110.257001

26.

HuDLuXZhangWLuoHLiSWangPet alStructural and Magnetic Phase Transitions Near Optimal Superconductivity in BaFe2(As1−xPx)2. Phys Rev Lett (2015) 114:157002. 10.1103/physrevlett.114.157002

27.

ZhangWWeiYXieTLiuZGongDMaXet alUnconventional Antiferromagnetic Quantum Critical Point in Ba(Fe0.97Cr0.03)2(As1−xPx)2. Phys Rev Lett (2019) 122:037001. 10.1103/physrevlett.122.037001

28.

LiuZGuYZhangWGongDZhangWXieTet alNematic Quantum Critical Fluctuations in BaFe2−xNixAs2. Phys Rev Lett (2016) 117:157002. 10.1103/physrevlett.117.157002

29.

GuYLiuZXieTZhangWGongDHuDet alUnified Phase Diagram for Iron-Based Superconductors. Phys Rev Lett (2017) 119:157001. 10.1103/physrevlett.119.157001

30.

ChandraPColemanPLarkinAI. Ising Transition in Frustrated Heisenberg Models. Phys Rev Lett (1990) 64:88–91. 10.1103/physrevlett.64.88

31.

HuJXuC. Nematic Orders in Iron-Based Superconductors. Phys C Supercond (2012) 481:215–22. 10.1016/j.physc.2012.05.002

32.

FernandesRMChubukovAVSchmalianJ. What Drives Nematic Order in Iron-Based Superconductors?Nat Phys (2014) 10:97–104. 10.1038/nphys2877

33.

FernandesRMChubukovAVKnolleJEreminISchmalianJ. Preemptive Nematic Order, Pseudogap, and Orbital Order in the Iron Pnictides. Phys Rev B (2012) 85:024534. 10.1103/physrevb.85.024534

34.

WangFKivelsonSALeeD-H. Nematicity and Quantum Paramagnetism in FeSe. Nat Phys (2015) 11:959–63. 10.1038/nphys3456

35.

MaCWuLYinW-GYangHShiHWangZet alStrong Coupling of the Iron-Quadrupole and Anion-Dipole Polarizations in Ba(Fe1−xCox)2As2. Phys Rev Lett (2014) 112:077001. 10.1103/physrevlett.112.077001

36.

ThorsmølleVKKhodasMYinZPZhangCCarrSVDaiPet alCritical Quadrupole Fluctuations and Collective Modes in Iron Pnictide Superconductors. Phys Rev B (2016) 93:054515. 10.1103/physrevb.93.054515

37.

WangQShenYPanBHaoYMaMZhouFet alStrong Interplay between Stripe Spin Fluctuations, Nematicity and Superconductivity in FeSe. Nat Mater (2015) 15:159–63. 10.1038/nmat4492

38.

ChubukovAVFernandesRMSchmalianJ. Origin of Nematic Order in FeSe. Phys Rev B (2015) 91:201105(R). 10.1103/physrevb.91.201105

39.

YamakawaYOnariSKontaniH. Nematicity and Magnetism in FeSe and Other Families of F-Based Superconductors. Phys Rev X (2016) 6:021032. 10.1103/physrevx.6.021032

40.

LeeC-CYinW-GKuW. Ferro-Orbital Order and Strong Magnetic Anisotropy in the Parent Compounds of Iron-Pnictide Superconductors. Phys Rev Lett (2009) 103:267001. 10.1103/physrevlett.103.267001

41.

KrügerFKumarSZaanenJvan den BrinkJ. Spin-orbital Frustrations and Anomalous Metallic State in Iron-Pnictide Superconductors. Phys Rev B (2009) 79:054504. 10.1103/physrevb.79.054504

42.

LvWWuJPhillipsP. Orbital Ordering Induces Structural Phase Transition and the Resistivity Anomaly in Iron Pnictides. Phys Rev B (2009) 80:224506. 10.1103/physrevb.80.224506

43.

ChenC-CMaciejkoJSoriniAPMoritzBSinghRRPDevereauxTP. Orbital Order and Spontaneous Orthorhombicity in Iron Pnictides. Phys Rev B (2010) 82:100504(R). 10.1103/physrevb.82.100504

44.

ValenzuelaBBasconesECalderónMJ. Conductivity Anisotropy in the Antiferromagnetic State of Iron Pnictides. Phys Rev Lett (2010) 105:207202. 10.1103/physrevlett.105.207202

45.

ChuJ-HAnalytisJGDe GreveKMcMahonPLIslamZYamamotoYet alIn-Plane Resistivity Anisotropy in an Underdoped Iron Arsenide Superconductor. Science (2010) 329:824–6. 10.1126/science.1190482

46.

TanatarMABlombergECKreyssigAKimMGNiNThalerAet alUniaxial-strain Mechanical Detwinning of CaFe2As2 and BaFe2As2 Crystals: Optical and Transport Study. Phys Rev B (2010) 81:184508. 10.1103/physrevb.81.184508

47.

YingJJWangXFWuTXiangZJLiuRHYanYJet alMeasurements of the Anisotropic In-Plane Resistivity of Underdoped FeAs-Based Pnictide Superconductors. Phys Rev Lett (2011) 107:067001. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.067001

48.

ManHLuXChenJSZhangRZhangWLuoHet alElectronic Nematic Correlations in the Stress-free Tetragonal State of BaFe2−xNixAs2. Phys Rev B (2015) 92:134521. 10.1103/physrevb.92.134521

49.

LuoXStanevVShenBFangLLingXSOsbornRet alAntiferromagnetic and Nematic Phase Transitions in BaFe2(As1−xPx)2 Studied by Ac Microcalorimetry and SQUID Magnetometry. Phys Rev B (2015) 91:094512. 10.1103/physrevb.91.094512

50.

MirriCDuszaABastelbergerSChuJ-HKuoH-HFisherIRet alHysteretic Behavior in the Optical Response of the Underdoped Fe Arsenide Ba(Fe1−xCox)2As2 in the Electronic Nematic Phase. Phys Rev B (2014) 89:060501(R). 10.1103/physrevb.89.060501

51.

FisherIRDegiorgiLShenZX. In-plane Electronic Anisotropy of Underdoped '122' Fe-Arsenide Superconductors Revealed by Measurements of Detwinned Single Crystals. Rep Prog Phys (2011) 74:124506. 10.1088/0034-4885/74/12/124506

52.

YiMLuDChuJ-HAnalytisJGSoriniAPKemperAFet alSymmetry-breaking Orbital Anisotropy Observed for Detwinned Ba(Fe1-xCox)2 as 2 above the Spin Density Wave Transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2011) 108:6878–83. 10.1073/pnas.1015572108

53.

YiMZhangYLiuZ-KDingXChuJ-HKemperAFet alDynamic Competition between Spin-Density Wave Order and Superconductivity in Underdoped Ba1−xKxFe2As2. Nat Commun (2014) 5:3711. 10.1038/ncomms4711

54.

YiMLuDHMooreRGKihouKLeeC-HIyoAet alElectronic Reconstruction through the Structural and Magnetic Transitions in Detwinned NaFeAs. New J Phys (2012) 14:073019. 10.1088/1367-2630/14/7/073019

55.

YiMPfauHZhangYHeYWuHChenTet alNematic Energy Scale and the Missing Electron Pocket in FeSe. Phys Rev X (2019) 9:041049. 10.1103/physrevx.9.041049

56.

ZhangYHeCYeZRJiangJChenFXuMet alSymmetry Breaking via Orbital-dependent Reconstruction of Electronic Structure in Detwinned NaFeAs. Phys Rev B (2012) 85:085121. 10.1103/physrevb.85.085121

57.

YiMZhangYShenZ-XLuD. Role of the Orbital Degree of Freedom in Iron-Based Superconductors. npj Quant Mater (2017) 2:57. 10.1038/s41535-017-0059-y

58.

WatsonMDDudinPRhodesLCEvtushinskyDVIwasawaHAswarthamSet alProbing the Reconstructed Fermi Surface of Antiferromagnetic BaFe2As2 in One Domain. npj Quantum Mat (2019) 4:36. 10.1038/s41535-019-0174-z

59.

LuoHWangMZhangCLuXRegnaultL-PZhangRet alSpin Excitation Anisotropy as a Probe of Orbital Ordering in the Paramagnetic Tetragonal Phase of Superconducting BaFe1.904Ni0.096As2. Phys Rev Lett (2013) 111:107006. 10.1103/physrevlett.111.107006

60.

LuXParkJTZhangRLuoHNevidomskyyAHSiQet alNematic Spin Correlations in the Tetragonal State of Uniaxial-Strained BaFe2−xNix as 2. Science (2014) 345:657–60. 10.1126/science.1251853

61.

ZhangWParkJTLuXWeiYMaXHaoLet alEffect of Nematic Order on the Low-Energy Spin Fluctuations in Detwinned BaFe1.935Ni0.065As2. Phys Rev Lett (2016) 117:227003. 10.1103/physrevlett.117.227003

62.

SongYLuXAbernathyDLTamDWNiedzielaJLTianWet alEnergy Dependence of the Spin Excitation Anisotropy in Uniaxial-Strained BaFe1.9Ni0.1As2. Phys Rev B (2015) 92:180504(R). 10.1103/physrevb.92.180504

63.

LuXSchererDDTamDWZhangWZhangRLuoHet alSpin Waves in Detwinned BaFe2As2. Phys Rev Lett (2018) 121:067002. 10.1103/physrevlett.121.067002

64.

RenXDuanLHuYLiJZhangRLuoHet alNematic Crossover in BaFe2As2 under Uniaxial Stress. Phys Rev Lett (2015) 115:197002. 10.1103/physrevlett.115.197002

65.

HuYRenXZhangRLuoHKasaharaSWatashigeTet alNematic Magnetoelastic Effect Contrasted between Ba(Fe1−xCox)2As2 and FeSe. Phys Rev B (2016) 93:060504(R). 10.1103/physrevb.93.060504

66.

BaekS-HEfremovDVOkJMKimJSvan den BrinkJBüchnerB. Orbital-driven Nematicity in FeSe. Nat Mater (2015) 14:210–4. 10.1038/nmat4138

67.

IyeTJulienM-HMayaffreHHorvatićMBerthierCIshidaKet alEmergence of Orbital Nematicity in the Tetragonal Phase of BaFe2(As1−xPx)2. J Phys Soc Jpn (2015) 84:043705. 10.7566/jpsj.84.043705

68.

RosenthalEPAndradeEFArguelloCJFernandesRMXingLYWangXCet alVisualization of Electron Nematicity and Unidirectional Antiferroic Fluctuations at High Temperatures in NaFeAs. Nat Phys (2014) 10:225–32. 10.1038/nphys2870

69.

IshidaSNakajimaMLiangTKihouKLeeCHIyoAet alAnisotropy of the In-Plane Resistivity of Underdoped Ba(Fe1−xCox)2As2 Superconductors Induced by Impurity Scattering in the Antiferromagnetic Orthorhombic Phase. Phys Rev Lett (2013) 110:207001. 10.1103/physrevlett.110.207001

70.

AllanMPChuangT-MMasseeFXieYNiNBud’koSLet alAnisotropic Impurity States, Quasiparticle Scattering and Nematic Transport in Underdoped Ca(Fe1−xCox)2As2. Nat Phys (2013) 9:220–4. 10.1038/nphys2544

71.

ZhangRGongDLuXLiSDaiPLuoH. The Effect of Cr Impurity to Superconductivity in Electron-Doped BaFe2−xNixAs2. Supercond Sci Technol (2014) 27:115003. 10.1088/0953-2048/27/11/115003

72.

ZhangRGongDLuXLiSLaverMNiedermayerCet alDoping Evolution of Antiferromagnetism and Transport Properties in Nonsuperconducting BaFe2−2xNixCrxAs2. Phys Rev B (2015) 91:094506. 10.1103/physrevb.91.094506

73.

GongDXieTZhangRBirkJNiedermayerCHanFet alDoping Effects of Cr on the Physical Properties of BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2. Phys Rev B (2018) 98:014512. 10.1103/physrevb.98.014512

74.

PizarroJMCalderónMJLiuJMuñozMCBasconesE. Strong Correlations and the Search for High-Tc Superconductivity in Chromium Pnictides and Chalcogenides. Phys Rev B (2017) 95:075115. 10.1103/physrevb.95.075115

75.

EdelmannMSangiovanniGCaponeMde' MediciL. Chromium Analogs of Iron-Based Superconductors. Phys Rev B (2017) 95:205118. 10.1103/physrevb.95.205118

76.

de’MediciLGiovannettiGCaponeM. Selective Mott Physics as a Key to Iron Superconductors. Phys Rev Lett (2014) 112:177001. 10.1103/physrevlett.112.177001

77.

LeePANagaosaNWenX-G. Doping a Mott Insulator: Physics of High-Temperature Superconductivity. Rev Mod Phys (2006) 78:17–85. 10.1103/revmodphys.78.17

78.

GuQWenH-H. Superconductivity in Nickel-Based 112 Systems. The Innovation (2022) 3:100202. 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100202

79.

SongYYamaniZCaoCLiYZhangCChenJSet alA Mott Insulator Continuously Connected to Iron Pnictide Superconductors. Nat Commun (2016) 7:13879. 10.1038/ncomms13879

80.

YinZPHauleKKotliarG. Kinetic Frustration and the Nature of the Magnetic and Paramagnetic States in Iron Pnictides and Iron Chalcogenides. Nat Mater (2011) 10:932–5. 10.1038/nmat3120

81.

GeorgesAMediciLd.MravljeJ. Strong Correlations from Hund's Coupling. Annu Rev Condens Matter Phys (2013) 4:137–78. 10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-020911-125045

82.

YiMLuDHAnalytisJGChuJ-HMoS-KHeR-Het alElectronic Structure of the BaFe2As2 Family of Iron-Pnictide Superconductors. Phys Rev B (2009) 80:024515. 10.1103/physrevb.80.024515

83.

RichardPSatoTNakayamaKTakahashiTDingH. Fe-based Superconductors: an Angle-Resolved Photoemission Spectroscopy Perspective. Rep Prog Phys (2011) 74:124512. 10.1088/0034-4885/74/12/124512

84.

SongYWangWZhangCGuYLuXTanGet alTemperature and Polarization Dependence of Low-Energy Magnetic Fluctuations in Nearly Optimally Doped NaFe0.9785Co0.0215As. Phys Rev B (2017) 96:184512. 10.1103/physrevb.96.184512

85.

SongYManHZhangRLuXZhangCWangMet alSpin Anisotropy Due to Spin-Orbit Coupling in Optimally Hole-Doped Ba0.67K0.33Fe2As2. Phys Rev B (2016) 94:214516. 10.1103/physrevb.94.214516

86.

XieTWeiYGongDFennellTStuhrUKajimotoRet alOdd and Even Modes of Neutron Spin Resonance in the Bilayer Iron-Based Superconductor CaKFe4As4. Phys Rev Lett (2018) 120:267003. 10.1103/physrevlett.120.267003

87.

XieTGongDGhoshHGhoshASodaMMasudaTet alNeutron Spin Resonance in the 112-Type Iron-Based Superconductor. Phys Rev Lett (2018) 120:137001. 10.1103/physrevlett.120.137001

88.

XieTLiuCBourdarotFRegnaultL-PLiSLuoH. Spin-excitation Anisotropy in the Bilayer Iron-Based Superconductor CaKFe4As4. Phys Rev Res (2020) 2:022018(R). 10.1103/physrevresearch.2.022018

89.

WangTZhangCXuLWangJJiangSZhuZet alStrong Pauli Paramagnetic Effect in the Upper Critical Field of KCa2Fe4As4F2. Sci China Phys Mech Astron (2020) 63:227412. 10.1007/s11433-019-1441-4

90.

GuoJYueLIidaKKamazawaKChenLHanTet alPreferred Magnetic Excitations in the Iron-Based Sr1−xNaxFe2As2 Superconductor. Phys Rev Lett (2019) 122:017001. 10.1103/physrevlett.122.017001

91.

LiuCBourgesPSidisYXieTHeGBourdarotFet alPreferred Spin Excitations in the Bilayer Iron-Based Superconductor CaK(Fe0.96Ni0.04)4As4 with Spin-Vortex Crystal Order. Phys Rev Lett (2022) 128:137003. 10.1103/physrevlett.128.137003

92.

LuoHWangZYangHChengPZhuXWenH-H. Growth and Characterization of A1−xKxFe2As2(A = Ba, Sr) Single Crystals With x= 0-0.4. Supercond Sci Technol (2008) 21:125014. 10.1088/0953-2048/21/12/125014

93.

ChenYLuXWangMLuoHLiS. Systematic Growth of BaFe2−xNixAs2 Large Crystals. Supercond Sci Technol (2011) 24:065004. 10.1088/0953-2048/24/6/065004

94.

XieTGongDZhangWGuYHuesgesZChenDet alCrystal Growth and Phase Diagram of 112-type Iron Pnictide Superconductor Ca1−yLayFe1−xNixAs2. Supercond Sci Technol (2017) 30:095002. 10.1088/1361-6668/aa7994

95.

WangTChuJFengJWangLXuXLiWet alLow Temperature Specific Heat of 12442-type KCa2Fe4As4F2 Single Crystals. Sci China Phys Mech Astron (2020) 63:297412. 10.1007/s11433-020-1549-9

96.

LuXTsengK-FKellerTZhangWHuDSongYet alImpact of Uniaxial Pressure on Structural and Magnetic Phase Transitions in Electron-Doped Iron Pnictides. Phys Rev B (2016) 93:134519. 10.1103/physrevb.93.134519

97.

TamDWWangWZhangLSongYZhangRCarrSVet alWeaker Nematic Phase Connected to the First Order Antiferromagnetic Phase Transition in SrFe2As2 Compared to BaFe2As2. Phys Rev B (2019) 99:134519. 10.1103/physrevb.99.134519

98.

TamDWYinZPXieYWangWStoneMBAdrojaDTet alOrbital Selective Spin Waves in Detwinned NaFeAs. Phys Rev B (2020) 102:054430. 10.1103/physrevb.102.054430

99.

LiuPKlemmMLTianLLuXSongYTamDWet alIn-plane Uniaxial Pressure-Induced Out-of-Plane Antiferromagnetic Moment and Critical Fluctuations in BaFe2As2. Nat Commun (2020) 11:5728. 10.1038/s41467-020-19421-5

100.

SobolevOParkJT. PUMA: Thermal Three Axes Spectrometer. J Large Scale Res Facil (2015) 1:A13. 10.17815/jlsrf-1-36

101.

DanilkinSAYethirajM. TAIPAN: Thermal Triple-Axis Spectrometer. Neutron News (2009) 20:37–9. 10.1080/10448630903241217

102.

NakamuraMKajimotoRInamuraYMizunoFFujitaMYokooTet alFirst Demonstration of Novel Method for Inelastic Neutron Scattering Measurement Utilizing Multiple Incident Energies. J Phys Soc Jpn (2009) 78:093002. 10.1143/jpsj.78.093002

103.

KajimotoRNakamuraMInamuraYMizunoFNakajimaKOhira-KawamuraSet alThe Fermi Chopper Spectrometer 4SEASONS at J-PARC. J Phys Soc Jpn (2011) 80:SB025. 10.1143/jpsjs.80sb.sb025

104.

InamuraYNakataniTSuzukiJOtomoT. Development Status of Software "Utsusemi" for Chopper Spectrometers at MLF, J-PARC. J Phys Soc Jpn (2013) 82:SA031. 10.7566/jpsjs.82sa.sa031

105.

ISIS Facility. ISIS Facility, Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, UK (2000). Available at: https://www.isis.stfc.ac.uk/Pages/Excitations-Software.aspx.

106.

BlombergECTanatarMAFernandesRMMazinIIShenBWenH-Het alSign-reversal of the In-Plane Resistivity Anisotropy in Hole-Doped Iron Pnictides. Nat Commun (2013) 4:1914. 10.1038/ncomms2933

107.

MaJQLuoXGChengPZhuNLiuDYChenFet alEvolution of Anisotropic In-Plane Resistivity with Doping Level in Ca1−xNaxFe2As2 Single Crystals. Phys Rev B (2014) 89:174512. 10.1103/physrevb.89.174512

108.

KobayashiTTanakaKMiyasakaSTajimaS. Importance of Fermi Surface Topology for In-Plane Resistivity Anisotropy in Hole- and Electron-Doped Ba(Fe1−xTMx)2As2 (TM = Cr, Mn, and Co). J Phys Soc Jpn (2015) 84:094707. 10.7566/jpsj.84.094707

109.

IshidaKTsujiiMHosoiSMizukamiYIshidaSIyoAet alNovel Electronic Nematicity in Heavily Hole-Doped Iron Pnictide Superconductors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2020) 117:6424–9. 10.1073/pnas.1909172117

110.

TamDW. Uniaxial Pressure Effect on the Magnetic Ordered Moment and Transition Temperatures in BaFe2−xTxAs2 (T = Co, Ni). Phys Rev B (2017) 95:060505(R). 10.1103/physrevb.95.060505

111.

DaghoferMLuoQ-LYuRYaoDXMoreoADagottoE. Orbital-weight Redistribution Triggered by Spin Order in the Pnictides. Phys Rev B (2010) 81:180514(R). 10.1103/physrevb.81.180514

Summary

Keywords

iron-based superconductors, electronic nematic phase, nematic fluctuations, resistivity, spin excitations, orbital ordering, neutron scattering

Citation

Gong D, Yi M, Wang M, Xie T, Zhang W, Danilkin S, Deng G, Liu X, Park JT, Ikeuchi K, Kamazawa K, Mo S-K, Hashimoto M, Lu D, Zhang R, Dai P, Birgeneau RJ, Li S and Luo H (2022) Nematic Fluctuations in the Non-Superconducting Iron Pnictide BaFe1.9−xNi0.1CrxAs2. Front. Phys. 10:886459. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2022.886459

Received

28 February 2022

Accepted

12 April 2022

Published

13 June 2022

Volume

10 - 2022

Edited by

Ivar Martin, Argonne National Laboratory (DOE), United States

Reviewed by

Andreas Kreisel, Leipzig University, Germany

Yao Shen, Brookhaven National Laboratory (DOE), United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Gong, Yi, Wang, Xie, Zhang, Danilkin, Deng, Liu, Park, Ikeuchi, Kamazawa, Mo, Hashimoto, Lu, Zhang, Dai, Birgeneau, Li and Luo.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huiqian Luo, hqluo@iphy.ac.cn

† Present addresses: Dongliang Gong, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee, United States Tao Xie, Neutron Scattering Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, United States Wenliang Zhang, Photon Science Division, Swiss Light Source, Paul Scherrer Institut, Villigen PSI, Switzerland

This article was submitted to Condensed Matter Physics, a section of the journal Frontiers in Physics

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.