Abstract

We have investigated the effect of the target atomic number Z2 on the mean charge state ( using various model predictions such as the Shima–Ishihara –Mikumo, Ziegler–Biersack–Littmark, Schiwietz, Schiwietz–Grande , Fermi-gas-models and theoretical codes with experimental data available in the literature. This investigation makes it possible to determine the best-fit model to calculate . In this work, we discuss the post-collision charge state distribution in different targets used as thin films and projectile beams (Fq+, Siq+, Clq+, and Cuq+) with different charge states (available in literature). A detailed overview of such collision experiments has been explored over a wide energy range of 1.07–3.93 MeV/u. In this contribution, an overview of the mean charge state dependence on the Fermi velocity of target materials is provided. Finally, the influence of the non-radiative electron capture at the target exit surface on the projectile charge state distribution for fast projectiles in different targets is shown, and a comparison is made with experimental data.

1 Introduction

The interaction of highly charged ions with media particles through gaseous, solid, and plasma targets has been the subject of extensive study for understanding fundamental problems in atomic and nuclear physics, plasma physics, accelerator physics, and various applications in semiconductor technology [1–5]. These interactions are complex due to the simultaneous occurrence of various physical processes, such as ionization, excitation, radiative decay, Auger decay, electron decay, and radiative and non-radiative electron capture. Several studies have been conducted to shed light on these interactions [6–9]. These studies provide theoretical frameworks, experimental techniques, and data collected up to the time of publication. When highly charged ions (HCIs) penetrate through targets (gaseous or solid), they interact with the target atoms and produce a charge state distribution (CSD). To replicate the mean charge state (, various empirical models have been proposed, including the Thomas–Fermi model [10], Bohr model [11], Betz model [11], Itoh model [11], Ziegler–Biersack–Littmark model (Z-B-L) [11], Nikolaev–Dmitriev model [12], To-Drouin model [13, 14], Shima–Ishihara–Mikumo model (S-I-M) [15], Schiwietz–Grande model (S-G-M) [16], Schiwietz model [17], and the Fermi-gas model (F-G-M) [18]. These models are based on experimental results obtained from electromagnetic measurements.

In this work, only the models that demonstrate a dependency of the mean charge state ( on the target atomic number are considered. The dependence on is analyzed due to its numerous applications in industries related to plasma processing and others, where the distribution of charge states is of importance. These include the Shima–Ishihara–Mikumo model, Ziegler–Biersack–Littmark model, Schiwietz model, Schiwietz–Grande model, and Fermi-gas model. On the other hand, models that do not display such dependencies, such as the Thomas–Fermi model, Bohr model, Betz model, Nikolaev–Dmitriev model, To-Drouin model, and Itoh model, will not be discussed.

Currently, there are computer programs such as ETACHA [19], GLOBAL and CHARGE [20], and BREIT [21] that can calculate the charge state fractions as the ion beam moves through solid and gaseous targets [22, 23]. A new version of ETACHA, called ETACHA4, has recently been developed, [24] and it can now handle lower energies (0.05–30 MeV/u) and ions with up to 60 electrons. Additionally, the equilibrium mean charge state can now be measured using X-ray spectroscopy [25].

We have compared the predictions of empirical models such as Z-B-L and F-G-M; semi-empirical models including S-I-M, Schiwietz model, and S-G-M; and the theoretical model ETACHA4 for the dependence of the mean charge state ( on the target atomic number , with experimental results [26]. In this comparison, the mean charge state ( of Si (5+–10+), Cl (8+–12+), F (5+–8+), and Cu (12+) projectiles, with energies ranging from 1.07 to 3.93 MeV/u, 1.94–3.08 MeV/u, 1.5–3.10 MeV/u, and 1.86 MeV/u, respectively, have been used with different solid targets ( = 4–83). The experimental data used in this study were taken from Ref. 26. The selection of halogenated projectiles was made due to their high charge exchange efficiency, while Si and Cu projectiles are important in the semiconductor industry.

2 General background

When an ion beam passes through a target with the thickness x (atoms/cm2), various electron capture and loss processes (radiative and non-radiative electron capture, ionization, electron emission, excitation to bound states, etc.) become effective, and for increasing target thickness, the charge state fractions change greatly due to the influence of competing for ionization (electron loss) and recombination (electron capture) processes, i.e., charge-changing processes. The charge state fraction represents the likelihood of the projectile ion having a specific charge state q after passing through a target of thickness x. As the target thickness increases, the values of can change significantly due to the interplay of ionization (electron loss) and recombination (electron capture) processes [27], which are responsible for the change in charge state within the medium.

The dependence of the on the target thickness x is found by solving the balance (rate) equations (first-order differential equations), which relate with the cross-sections of projectile ion interactions with media particles [3]. In the case of gas/foil targets, the balance equations have the formwhere x is the target thickness or the areal density. The sum over q means the summation of cross-sections over all possible charge states: for i < j is the single- and multiple-electron loss, and for i > j are electron capture cross-sections, respectively, in cm2/atom units. Here, N is the target density in atom/cm3 units, and L is the penetration depth of ions in the target in cm.

For a given equilibrium charge state distribution, the equilibrium mean charge state is defined by

The distribution of equilibrium fractions over charge states q is usually described by a Gaussian distribution with the following parameters: distribution width d is given byand the asymmetry parameter s (skewness) is defined as

3 Empirical and semi-empirical models

We shall briefly discuss different empirical and semi-empirical models and ETACHA4 for the equilibrium mean charge state involving with experimental data [26].

3.1 Shima–Ishihara–Mikumo model

The Shima–Ishihara–Mikumo model [15] has refined the equilibrium mean charge state to make it compatible with the value at higher energies. This refined is given by,where is the reduced velocity, and is the atomic number of the targets. Next, using the non-carbon target data, the Shima–Ishihara–Mikumo model approximated a linear combination of with a correction term of where is a function of target dependence, to be multiplied by the original expression to get

Here

The authors cite the limitations of their target-dependent model as , and . The limitations are based on the available data pool used by the Shima–Ishihara–Mikumo model.

3.2 Ziegler–Biersack–Littmark model

The Ziegler–Biersack–Littmark model is used in the well-known Stopping and Range of Ions in Matter (SRIM) code [11]. The Z-B-L formula can be written as:where is the reduced velocity as given by and is the relative velocity as given bywhere v is the ion velocity and is the Fermi velocity of the medium. The Fermi velocity is the electron velocity at the highest occupied energy level for conduction electrons in the solid.

3.3 Schiwietz model

Schiwietz et al. [17] have used a large array of over 800 data points that span a wide variety of ions and aims to determine the equilibrium mean charge state for the systems that are studied. The expression for is given as,

Here, Z is the atomic number of the ion,is a reformulated reduced velocity, and the power term is used to adjust the steepness of the charge state curves as a function of x with the following correction terms:andwhere is the atomic number of the target. The scaled projectile velocity is given by,where is the Bohr velocity.

3.4 Schiwietz–Grande model

The Schiwietz–Grande model (S-G-M) [16] has presented a highly parameterized least-squares fit built from an array of over 850 experimental data points for the equilibrium mean charge state . The expression for is given as,where

3.5 Fermi-gas model

According to the Fermi-gas model (F-G-M)-based empirical formula, the mean charge state inside the target [18] is given by,with and being the projectile atomic number and Fermi velocity of the target electrons, respectively.

4 Results and discussion

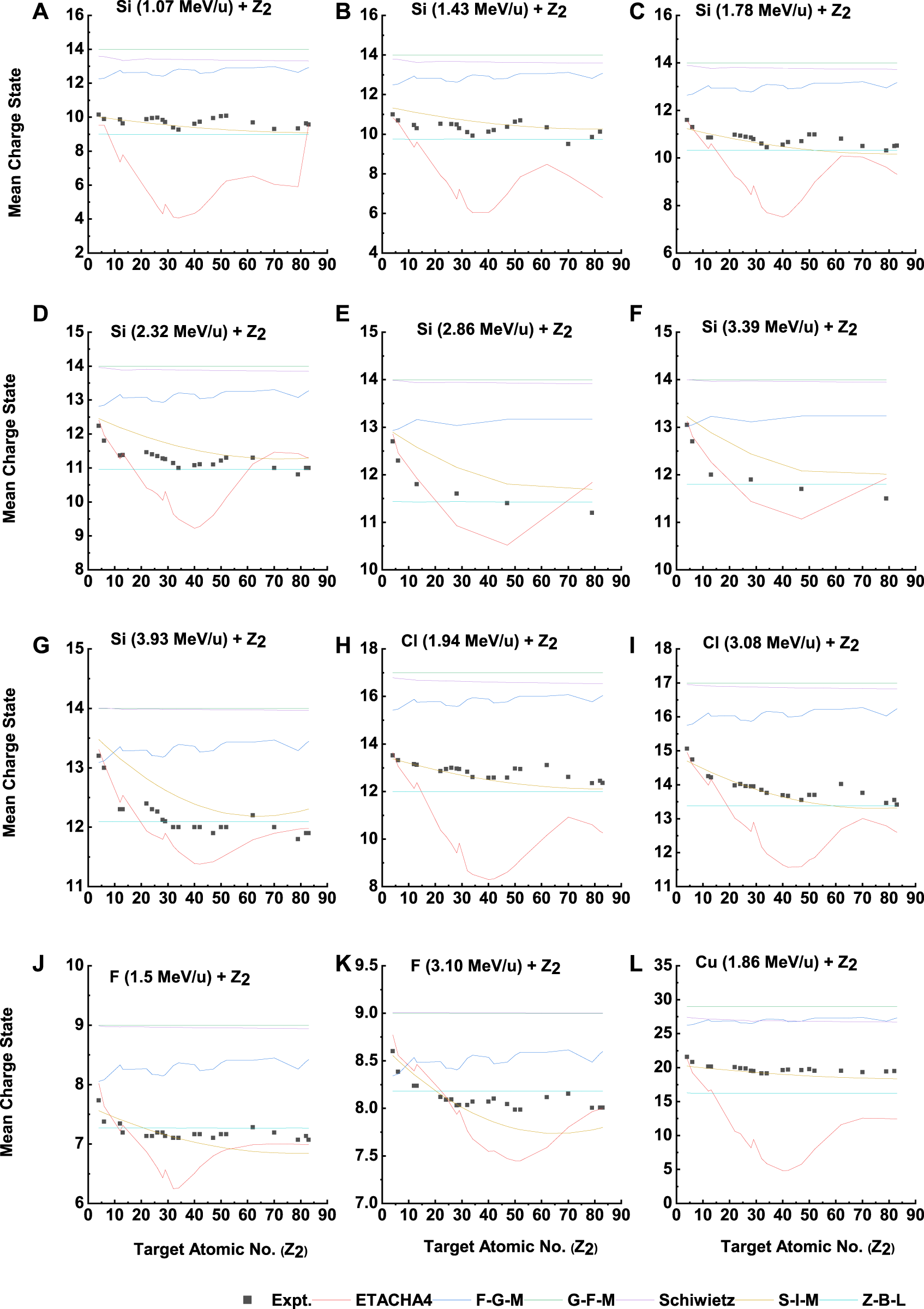

We have conducted a comparison between the predictions of empirical, semi-empirical, and theoretical models (ETACHA4) for the dependence of the equilibrium mean charge state on with experimental results [26]. This comparison is shown in Figure 1 for Si, Cl, F, and Cu projectiles. The experimental mean charge states [26] show an oscillatory behavior as a function of , rather than a monotonic decrease with increasing target atomic number. This oscillatory pattern may suggest the presence of electron capture from inner shell vacancies [27].

FIGURE 1

The equilibrium mean charge state vs. target atomic number for Si (A–G), Cl (H, I), F (J, K), and Cu (L) projectiles at different energies. Experimental data are taken from Ref. 26. The solid lines are provided only to guide the eye.

The oscillation in the mean charge state decreases as the energy of the projectile increases, as the projectile spends less time near the target atom. At high projectile energies, the target electrons may contribute more to excitation and ionization [27] than to Coulombic interactions at the exit surface of the target. Additionally, if the energy of the projectile is raised, the mean equilibrium charge state for a fixed target also increases, resulting in a higher charge state distribution.

In contrast, at lower energies, the inner shell electron contributes less to the excitation and ionization, which can be inferred from Coulombic repulsion dominating at the exit surface of the target.

The Z-B-L empirical model demonstrates a weak dependence between the mean charge state and . The mean charge state does not change significantly with an increase in , showing not even a difference of 1 in for all values. The Z-B-L model also shows an oscillatory (not monotonic) behavior of with increasing and a decrease in the mean charge state with an increase in the target atomic number, as observed in Figure 1. The model slightly overestimates the mean charge state of fluorine ions but underestimates the mean charge states of heavier projectiles from Si to Cu. At low beam energies for all projectiles, there is a considerable difference (0.01–5.29) between the experimental data and Z-B-L predictions, but as the beam energy increases, the agreement between the experimental data and Z-B-L predictions improves.

In the F-G-M model, the predictions for the mean charge state are consistently overestimated compared to the experimental results for all four projectiles (Si, Cl, F, and Cu) across the entire target atomic number range . At lower beam energies, there is a large discrepancy between the experimental data and F-G-M predictions (with differences ranging from 0.39 to 9.83). However, as the beam energy increases, the agreement between the two improves. Like the Z-B-L model, the F-G-M model also exhibits a weak dependence of on .

In the Schiwietz model, there is a considerable gap (5.85–7.77) between the experimental results and the model’s predictions for all four projectile ions across the range of target atomic numbers. The model overestimates the experimental results, but as the beam energy increases, the agreement improves gradually. This significant mismatch at low energies can be attributed to the model’s failure to properly account for excitation and ionization effects.

The S-I-M model predicts a monotonic decrease in the mean charge state with increasing , as shown in Figure 1. However, this differs from the experimental results, where the decrease is not monotonic. For Si projectiles with an energy of 1.07 MeV/u, the S-I-M predictions are lower than those in the experimental data. As the projectile energy increases from 1.43 to 3.93 MeV/u, the S-I-M predictions overestimate the experimental value throughout the target atomic number range. In the case of Cl projectiles, the S-I-M predictions underestimate the experimental value for energies between 1.94 and 3.08 MeV/u, with the exception of target atomic numbers 12–26 at 3.08 MeV/u, where the S-I-M predictions are higher. For F ions with the energy range of 1.5 and 3.10 MeV/u, the S-I-M predictions overestimate the experimental data for low target atomic numbers (4–24), but the agreement improves as the target atomic number increases (26–34). For target atomic numbers greater than 34, the S-I-M predictions underestimate the experimental results. Overall, the SI-M model underestimates experimental results throughout the energy range, barring exceptions for the Cl projectile. This difference between the experimental and S-I-M results could be due to the semi-empirical nature of the S-I-M model.

The F-G-M model reveals an oscillatory pattern in the mean charge state with respect to , shown in Figure 1. The calculated mean charge state from F-G-M model, thus, demonstrates a behavior that is opposite to the experimental and consistently overestimates the experimental , as seen in Figure 5. There is a difference of 0.02–8.08 between the experimental and F-G-M . As the energy of the beam increases, the agreement between the experimental and calculated results gradually improves. It is important to mention that in the F-G-M model, the charge state distribution within the target is considered, but the combined effects of both within the target and at the exit surface are seen in the experimental results.

Further, the ETACHA4 model does not show oscillatory behavior in with , as seen in Figure 1 for Si, Cl, F, and Cu projectiles, respectively. At low target atomic numbers (4–6), there is good agreement between the experimental data and ETACHA4 predictions. However, as the target atomic number increases ( =12–13), a considerable difference between the two is observed, with the ETACHA4 data underestimating the experimental data. For intermediate values ( =22–52), ETACHA4 again underestimates the experimental data, but the difference between experimental and ETACHA4 is as much as 14–15. Despite ETACHA4 underestimating experimental for low energies (1.07–1.78 MeV/u) and overestimating it for high energies (2.32–3.93 MeV/u) at high ( =62–83), there is still good agreement between the experimental data and ETACHA4 predictions. As the projectile energy increases, the deviation between the experimental data and ETACHA4 predictions decreases across all . To understand why these differences are observed, we examine the parameter [24]. The discussion of the results from ETACHA4 has focused on the projectile perturbation parameters. When a single theoretical method tries to address both perturbative and non-perturbative collision systems, it often fails to match experimental observations. To determine whether a collision system falls within the perturbative or non-perturbative regime, one can use the projectile perturbation parameter , which has been defined by Ref. 24 as follows:

The atomic numbers of the target and the projectile are represented by and , respectively. The mean orbital velocity of the active electron of the projectile ion is represented by , and the velocity of the projectile is represented by . The value, thus, determines the dynamic conditions for a specific collision system.

Comparing the values of Kp parameters for different targets, we see that the values are less than 1 for Be, C, Mg, and Al targets throughout the energy range. One expects good agreement between the theory and experiment. The Kp parameter is greater than 1 for other targets throughout the energy range, and thus, the agreement between the theory and experiment may be worse, as evident from the figure. However, the departure is much higher in intermediate ( =22–52), albeit the Kp parameters remain greater than 1 for all the beam energies for a particular system.

In addition, for a quantitative evaluation of the model predictions, we have calculated the sum of the squared residuals (SSR),where is the residual or deference and n is the number of data points. The mean squared errorsto find the minimum mean errors for all Si, Cl, F, and Cu projectiles. Here, we can see that the lowest mean error on all projectile energies is obtained for S-I-M and Z-B-L models. Apart from S-I-M and Z-B-L, the minimum mean errors are obtained at the lowest levels for ETACHA4 and F-G-M. Therefore, either ETACHA4 or F-G-M can be used to estimate the mean charge state inside the solid target. However, ETACHA4 can only be used for a certain number of electrons in the projectile ion, and thus, difficulties arise in implementing it for heavier projectiles, whereas with F-G-M, there are no such restrictions.

In summary, the detailed comparison suggests that predictions from the S-I-M and Z-B-L models are somewhat superior to those from the other models. The mean charge state predicted by the S-I-M model decreases with the increase of the target atomic number (Z2) at fixed energy but does not show the oscillatory behavior observed in experimental results. However, the mean charge state predicted by the Z-B-L model decreases with the increase of the target atomic number (Z2), at fixed energy, with oscillatory behavior similar to experimental findings. It is also seen in this comparison that the mean charge state predicted by the F-G-M model also shows oscillatory behavior with the target atomic number. To understand the oscillatory behavior and deviation from the experimental data, we have scrutinized both models (Z-B-L and F-G-M) very precisely.

4.1 Effect of Fermi velocity

The Fermi velocity of the target plays an important role in understanding the oscillatory behavior of the mean charge state. Here, we have scrutinized Z-B-L and F-G-M models in terms of Fermi velocity owing to their empirical nature.

4.1.1 Z-B-L model

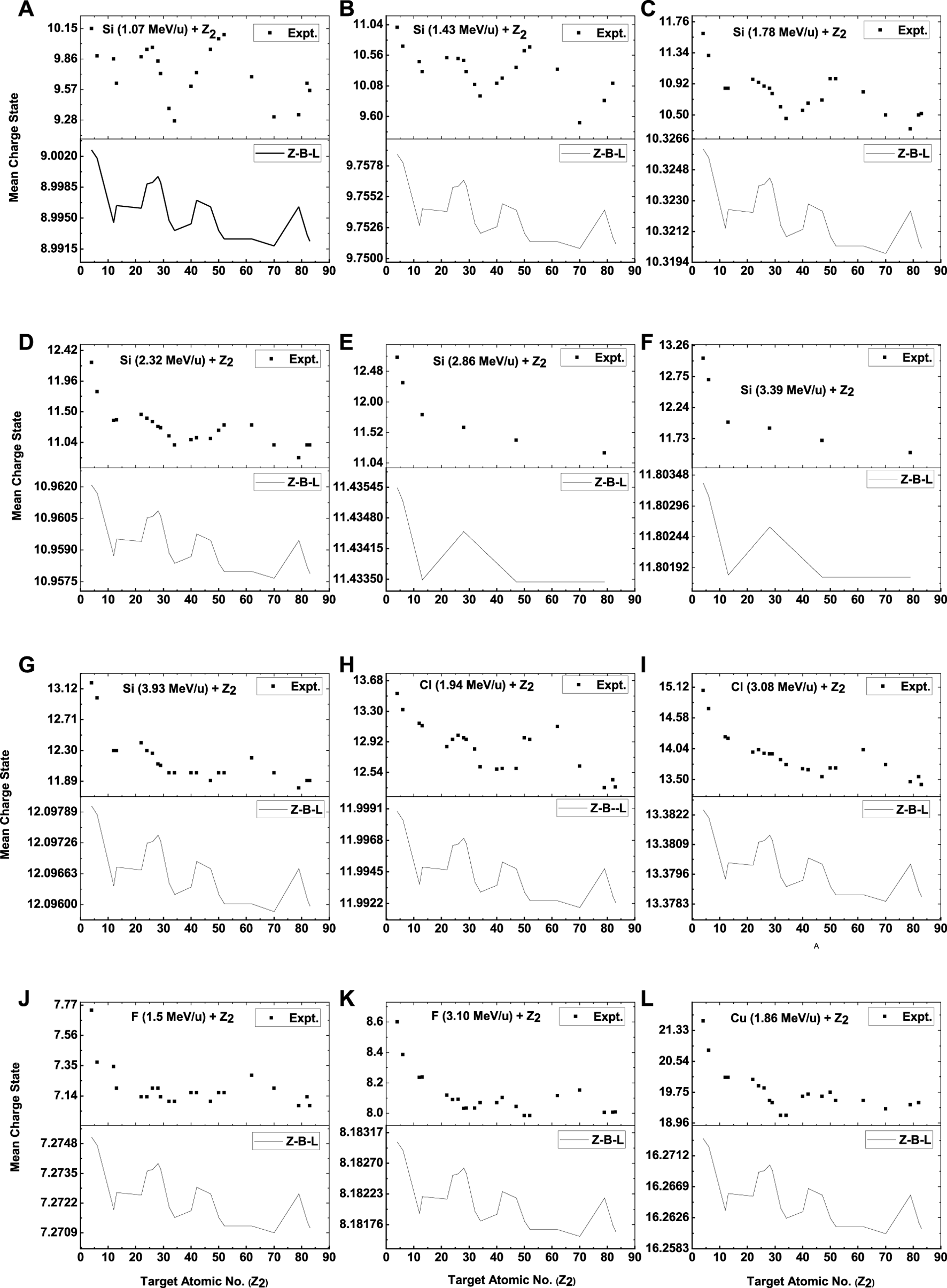

As discussed previously, the prediction of the Z-B-L model is closer to the experimental data. Apart from fluorine, for all projectiles (Si, Cl, and Cu), the predictions underestimate the experimental data, as shown in Figure 2. However, Z-B-L predictions show an oscillatory nature similar to that of the experimental results. Figure 3 shows the percentage deviation between Z-B-L predictions and experimental data. In Figure 4, we have shown ratio, where is the Fermi velocity and is the projectile velocity. According to Figure 4, a clear dependence of mean charge state distribution can be attributed to Fermi velocity.

FIGURE 2

Comparison of experimental mean charge state [26] with Z-B-L mean charge state at different energies as a function of target atomic number (A-L). The solid lines are to guide the eye only.

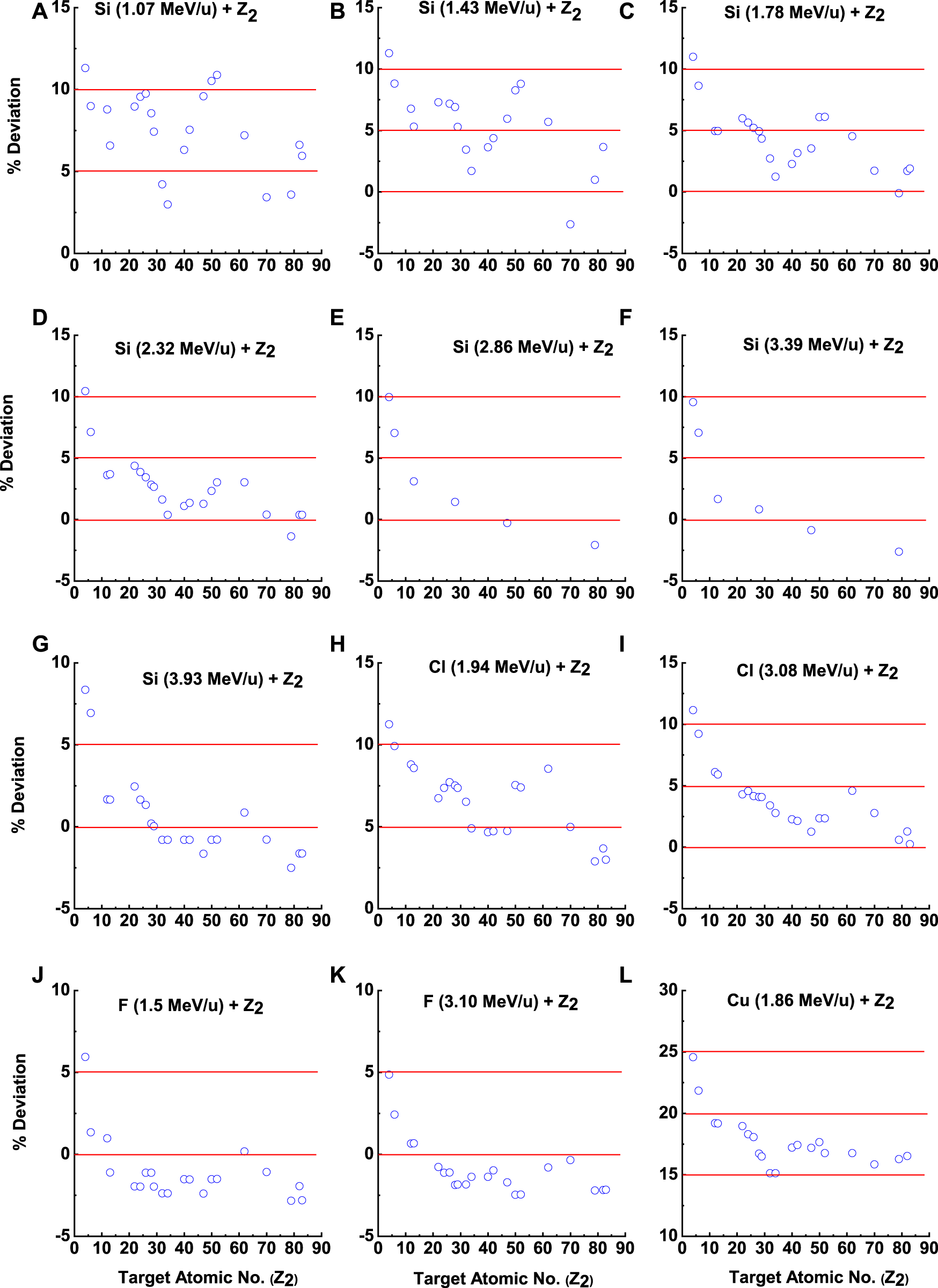

FIGURE 3

Comparison of the percentage of deviation of the Z-B-L model and the experimental mean charge state as a function of Z2(A-L).

FIGURE 4

Z2 dependence of Fermi velocities with respect to projectile velocities: (A) Si as projectile, (B) F as projectile, (C) Cl as projectile, and (D) Cu projectile.

The Fermi velocity is a measure of how quickly electrons can move within a material and is related to its electronic properties, such as electrical conductivity. The Fermi velocity is an important parameter in the calculation of various properties of solids and is also used in the description of electron–phonon interactions and transport phenomena in materials.

As can be seen from Figure 4, the oscillation strength is stronger for low Z targets. As the target atomic number increases, the strength of the oscillation decreases noticeably. This is a clear demonstration of the effect of the target’s electronic structure, as higher Z targets have more electrons compared to low Z target systems.

4.1.2 F-G-M model

Figure 5 shows a comparison between experimental data and theoretical results from the F-G-M model for the mean charge state against the target atomic number. Here, in Figure 5, the F-G-M model shows oscillatory behavior of with Z2, but in this model, we see that increases (not monotonically) with the increase of (Z2). Therefore, the calculated mean charge state from F-G-M shows the opposite behavior to experimental and F-G-M overestimates experimental also shown in Figure 5. However, the mean charge state predicted by the F-G-M model follows oscillatory behavior similar to experimental results. A comparison of the percentage of deviation of the F-G-M model and the experimental mean charge state as a function of Z2 is shown in Figures 6, 7; they show the percentage deviation between F-G-M predictions and experimental data. Since F-G-M overestimates experimental , this scenario favors the multi-electron capture process obtained at the exit surface of the target. In the next section, we will discuss the effect of electron capture at the exit surface in detail.

FIGURE 5

Comparison of experimental mean charge state [26] with F-G-M mean charge state at different energies as a function of target atomic number (A-L). The solid lines are to guide the eye only.

FIGURE 6

Comparison of the percentage of deviation of the F-G-M model and the experimental mean charge state as a function of Z2(A-L).

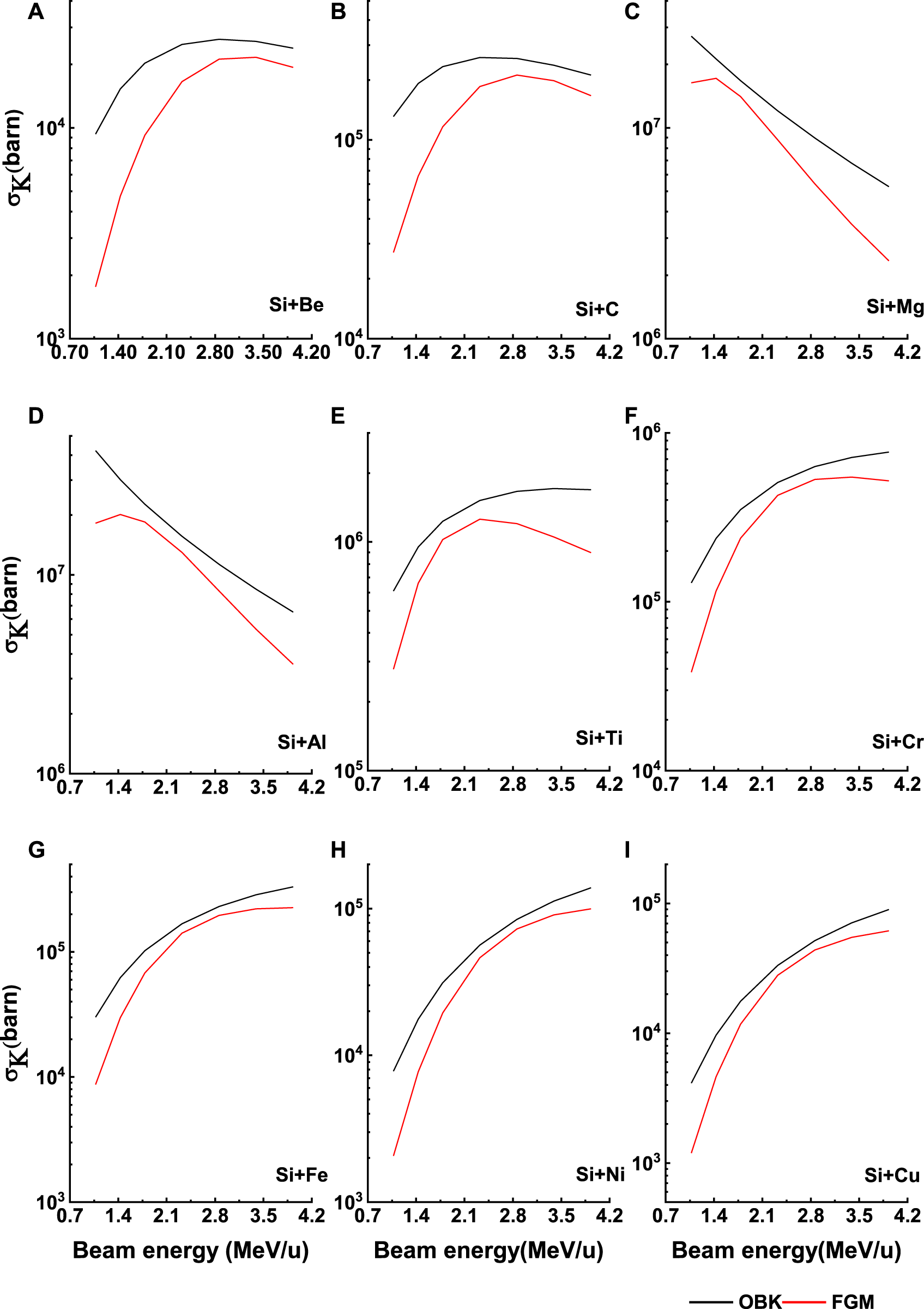

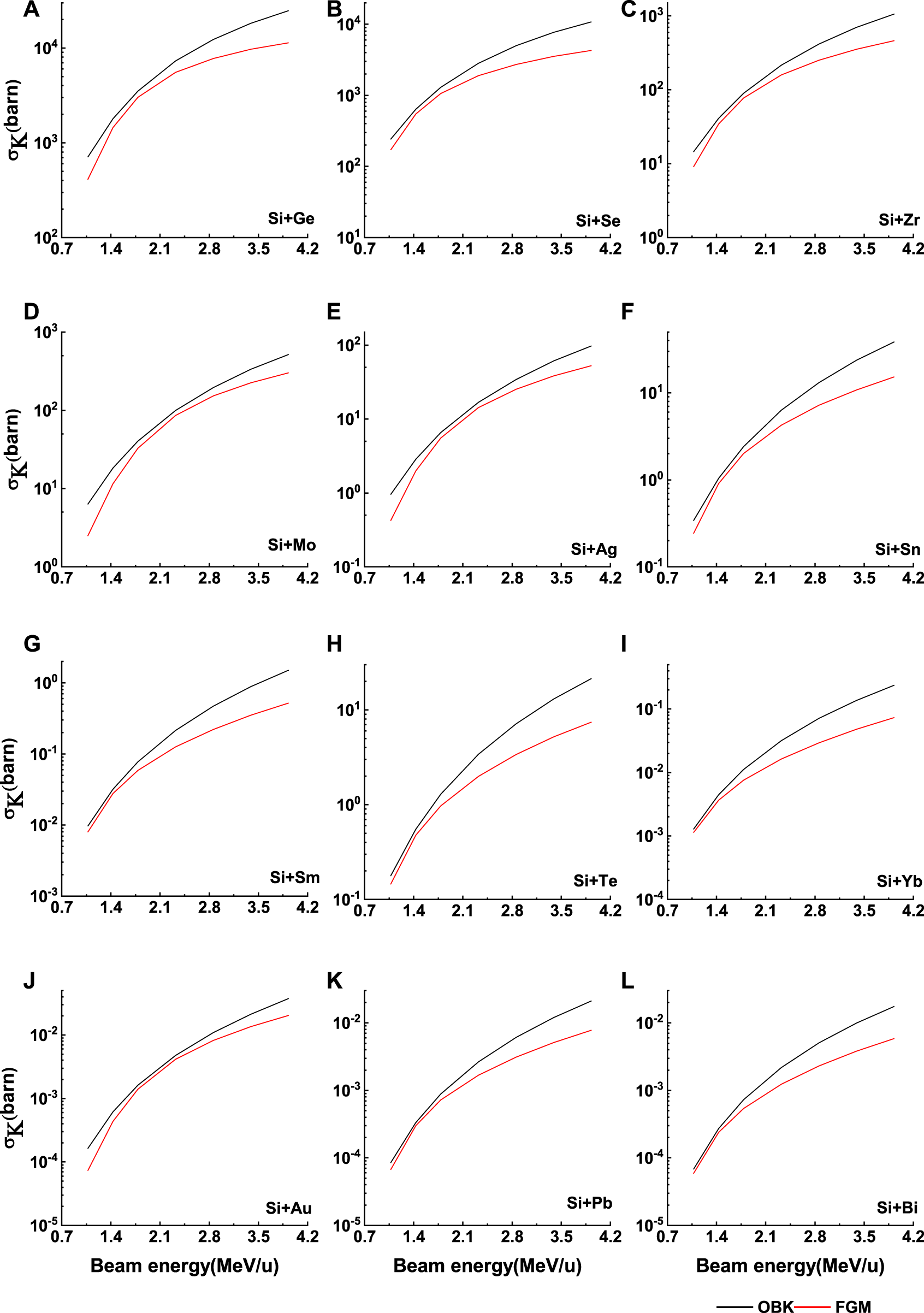

FIGURE 7

The electron capture cross sections obtained from OBK approximation and F-G-M prediction vs target atomic number (Z2) bombarded by H-like Si (A-G), Cl (H, I), F (J, K), and Cu (L) ion beam. The solid lines are to guide the eye only.

4.2 Effect of electron capture at the exit surface

Apart from the electron capture processes occurring inside the target, certain electron capture processes also occur at the exit surface of the target [28–32], including the radiative and non-radiative capture processes. In addition, the surface electron capture processes must change every charge state produced inside the target. Consequently, the mean charge state shifts to a lower charge state. This effect is more prominent on the low-energy side as the electron capture cross-section is higher at low beam velocities [28]. The F-G-M data in Figure 5 reflect this exact picture, i.e., the predictions are higher than the measured values. F-G-M overestimates experimental due to the charge-exchanging process at the target exit surface, i.e., the electron capture from the target exit surface to the projectile ion.

Furthermore, the difference in mean charge state between the experimental findings and the F-G-M model shown in Figure 5 goes even up to 3. Such a scenario favors the multi-electron capture process occurring at the exit surface of the target.

The underestimation of experimental data by the F-G-M model predictions shows that the surface electron capture processes must alter every charge state produced inside the target. To understand the deviation between experimental data [26] and F-G-M predictions, an electron capture phenomenon (electron capture cross section) is calculated. To obtain the electron capture cross-section from inner shells by fully stripped ions, the theory of Lapicki and Losonsky [33] has been used, which is based on the Oppenheimer–Brinkman–Kramers (OBK) approximation [34] with binding and Coulomb deflection correction for low-velocity ions. Thus, we have made use of Nikolaev’s electron capture cross-section [35] formula.and and are the shell orbital velocities for the projectile ion and target atoms in atomic units, where and are the principle quantum numbers of electrons in the and shell, respectively. It should be noted that the values of and are as prescribed by Slater rules. (in atomic units) and (in eV) are the projectile velocity and binding energy of the shell electron of the target, respectively. In the present work, projectile velocities [26] and shell orbital velocities atomic units are used.

Calculations for the electron capture cross section in Figures 4, 5 are based on the OBK approximation [34] and the F-G-M model [18] for H-like Si ions. The effective electron capture cross-section from the F-G-M model is equal to [38]. Here, is the charge state fraction for a specific charge state . The formula given is used to obtain [36]

Here, the distribution width is taken from Novikov and Telpova [37] as,

Here, and The mean charge state is calculated from the F-G-M model [18]. The results from the calculations are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Target | 1.07 MeV/u | 1.43 MeV/u | 1.78 MeV/u | 2.32 MeV/u | 2.86 MeV/u | 3.39 MeV/u | 3.93 MeV/u | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Si + Z2 | ||||||||||||||

| Si + Be | 12.26 | 0.19 | 12.50 | 0.31 | 12.65 | 0.45 | 12.82 | 0.67 | 12.94 | 0.81 | 13.02 | 0.84 | 13.09 | 0.81 |

| Si + C | 12.31 | 0.21 | 12.54 | 0.34 | 12.69 | 0.49 | 12.85 | 0.71 | 12.97 | 0.82 | 13.05 | 0.84 | 13.12 | 0.79 |

| Si + Mg | 12.77 | 0.60 | 12.94 | 0.81 | 13.05 | 0.84 | 13.16 | 0.73 | 13.25 | 0.61 | 13.31 | 0.51 | 13.36 | 0.44 |

| Si + Al | 12.63 | 0.43 | 12.82 | 0.67 | 12.94 | 0.82 | 13.07 | 0.83 | 13.16 | 0.73 | 13.23 | 0.63 | 13.29 | 0.54 |

| Si + Ti | 12.65 | 0.45 | 12.83 | 0.69 | 12.96 | 0.83 | 13.09 | 0.83 | 13.18 | 0.72 | 13.24 | 0.61 | 13.30 | 0.53 |

| Si + Cr | 12.48 | 0.29 | 12.68 | 0.49 | 12.82 | 0.68 | 12.97 | 0.84 | 13.07 | 0.84 | 13.14 | 0.76 | 13.20 | 0.68 |

| Si + Fe | 12.47 | 0.29 | 12.67 | 0.48 | 12.81 | 0.67 | 12.96 | 0.84 | 13.06 | 0.85 | 13.14 | 0.77 | 13.20 | 0.68 |

| Si + Ni | 12.43 | 0.26 | 12.64 | 0.44 | 12.78 | 0.62 | 12.93 | 0.82 | 13.04 | 0.86 | 13.12 | 0.80 | 13.18 | 0.72 |

| Si + Cu | 12.47 | 0.29 | 12.67 | 0.48 | 12.81 | 0.67 | 12.96 | 0.84 | 13.06 | 0.84 | 13.14 | 0.77 | 13.20 | 0.68 |

| Si + Ge | 12.75 | 0.58 | 12.92 | 0.81 | 13.03 | 0.86 | 13.15 | 0.76 | 13.24 | 0.63 | 13.30 | 0.53 | 13.35 | 0.46 |

| Si + Se | 12.84 | 0.71 | 12.99 | 0.86 | 13.10 | 0.82 | 13.21 | 0.67 | 13.29 | 0.54 | 13.35 | 0.46 | 13.39 | 0.39 |

| Si + Zr | 12.78 | 0.62 | 12.94 | 0.83 | 13.06 | 0.86 | 13.17 | 0.73 | 13.25 | 0.60 | 13.31 | 0.50 | 13.36 | 0.44 |

| Si + Mo | 12.59 | 0.39 | 12.78 | 0.63 | 12.91 | 0.81 | 13.05 | 0.87 | 13.14 | 0.78 | 13.21 | 0.67 | 13.27 | 0.58 |

| Si + Ag | 12.64 | 0.44 | 12.83 | 0.69 | 12.95 | 0.85 | 13.08 | 0.85 | 13.17 | 0.74 | 13.24 | 0.63 | 13.29 | 0.54 |

| Si + Sn | 12.84 | 0.71 | 12.99 | 0.87 | 13.10 | 0.83 | 13.21 | 0.67 | 13.29 | 0.54 | 13.35 | 0.46 | 13.39 | 0.39 |

| Si + Te | 12.92 | 0.82 | 13.06 | 0.87 | 13.16 | 0.75 | 13.26 | 0.58 | 13.34 | 0.47 | 13.39 | 0.39 | 13.43 | 0.35 |

| Si + Sm | 12.92 | 0.83 | 13.06 | 0.87 | 13.16 | 0.76 | 13.26 | 0.58 | 13.34 | 0.47 | 13.39 | 0.39 | 13.43 | 0.35 |

| Si + Yb | 12.99 | 0.89 | 13.12 | 0.82 | 13.21 | 0.67 | 13.31 | 0.51 | 13.38 | 0.41 | 13.43 | 0.35 | 13.47 | 0.31 |

| Si + Au | 12.64 | 0.45 | 12.83 | 0.71 | 12.95 | 0.87 | 13.08 | 0.87 | 13.17 | 0.75 | 13.24 | 0.63 | 13.29 | 0.54 |

| Si + Pb | 12.88 | 0.79 | 13.03 | 0.90 | 13.13 | 0.81 | 13.24 | 0.63 | 13.31 | 0.51 | 13.37 | 0.42 | 13.41 | 0.37 |

Charge state fraction of H-like Si (Si+13) obtained from F-G-M [18] in different target elements and at different kinetic energies of the Si ion beam.

Figure 7 shows a comparison between the electron capture cross-sections obtained from OBK approximations and F-G-M predictions, where the targets vary but the beam energy is fixed. As the target atomic number increases, a considerable difference occurs between the F-G-M predictions and the OBK approximation. However, F-G-M predictions underestimate the OBK approximation. For fixed ion beam energy, when the target atomic number increased, the electron capture cross-section increased. But, after a certain target atomic number, the electron capture cross-section decreased with increasing target atomic numbers. In Figure 7, we can see that, when , the electron capture cross-section increased as target atomic numbers increased because in this range, the OBK approximation is dominant. However, when , the electron capture cross-section decreased as target atomic numbers increased because, in this range, binding effect and Coulomb deflection are included in the capture cross-section.

In Figures 8, 9, the electron capture cross-sections were obtained from OBK approximation and F-G-M prediction for different targets bombarded by Si28 ions as a function of ion beam energies. Here, the electron capture cross-sections obtained from the F-G-M model predictions underestimate the OBK approximation. For low atomic numbers 4–6 and high atomic numbers 22–83, the electron capture cross-section increased with increasing beam energy for the asymmetric collision partners (. However, for a symmetric system (, the electron capture cross-section decreased with increasing beam energy.

FIGURE 8

The electron capture cross sections obtained from OBK approximation and F-G-M prediction for different targets (from Be to Cu) bombarded by Si28 ions as a function of ion beam energies (A-I). The solid lines are to guide the eye only.

FIGURE 9

The electron capture cross sections obtained from OBK approximation and F-G-M prediction for different targets (from Ge to Bi) bombarded by Si28 ions as a function of ion beam energies (A-L). The solid lines are to guide the eye only.

It is clear from the aforementioned scenario that the electromagnetic measurements, magnetic or electric, cannot map the actual picture occurring in the bulk of the foil as it concerns the total charge of the ion. The total charge is governed by both bulk and surface effects.

5 Conclusion

Drawing a thorough comparison with the experimental values, empirical models show a trend similar to that of the experimental results. After scrutinizing the F-G-M and Z-B-L models (both empirical) in terms of Fermi velocity and percentage deviation from the experimental results, the Z-B-L is found to be the best-fit model of all models considered in this study for calculating the mean charge state. Furthermore, the F-G-M model shows oscillatory behavior of with , but increases (not monotonically) with the increase of () which can be attributed to its lack of consideration of exit surface effects. We have also shown that the mean charge state inside the foil is much higher than that of the exit surface. This indicates that the exit surface plays a significant role in changing the charge state distribution. The oscillation strength is stronger for low Z targets. As the target atomic number increases, the strength of the oscillation decreases noticeably. We see that the F-G-M model predictions for the mean charge state overestimate the experimental mean charge state (Figure 5). The previous discussion and Figure 5 suggest that the electron capture at the exit surface of the target is crucial and needs to be included in the theoretical calculations.

For further study on the electron capture cross-section for different targets with different energies of the projectile, we observed that the electron capture cross-section from the OBK approximation differs from the electron capture cross-section from the F-G-M model prediction. The F-G-M model predictions underestimate the OBK approximation. Therefore, electron capture cross-sections from within and at the exit surface of the target are required to resolve this difference. In this context, a projectile’s mean charge state post-collision with the target is extremely essential. Furthermore, the study about the influence of the target atomic number (Z2) on mean charge state can enhance our understanding of the target density effect in bulk media.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

DK wrote the original draft of the manuscript. SK and BS revised the manuscript. RK supervised the manuscript preparation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

DK acknowledges discussion and support from ATMOL group at IUAC, New Delhi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

AlisonSKWarshawSD. Passage of heavy particles through matter. Rev Mod Phys (1953) 25:779–817. 10.1103/revmodphys.25.779

2.

AlisonSK. Experimental results on charge-changing collisions of hydrogen and helium atoms and ions at kinetic energies above 0.2 kev. Rev Mod Phys (1958) 30:1137–68. 10.1103/revmodphys.30.1137

3.

BetzHD. Charge states and charge-changing cross sections of fast heavy ions penetrating through gaseous and solid media. Rev Mod Phys (1972) 44:465–539. 10.1103/revmodphys.44.465

4.

SchardtDElsasserTSchulz-ErtnerD. Heavy-ion tumor therapy: Physical and radiobiological benefits. Rev Mod Phys (2010) 82:383–425. 10.1103/revmodphys.82.383

5.

NikoghosyanASchulz-ErtnerDDidingerBJakelOZunaIHossAet alEvaluation of therapeutic potential of heavy ion therapy for patients with locally advanced prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol. Phys. (2004) 58:89–97. 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)01439-1

6.

BetzH. D.Charge Equilibration of High-Velocity Ions in Matter. Methods Exp Phys (1980) 17:73-148. 10.1016/S0076-695X(08)60298-7

7.

ShimaKIshiharaTMiyoshiTMikumoT. Equilibrium charge-state distributions of 35—146-MeV Cu ions behind carbon foils. Phys Rev A (1983) 28:2162–8. 10.1103/physreva.28.2162

8.

ShimaKMikumoTTawaraH.Equilibrium charge state distributions of ions (Z1 ⩾ 4) after passage through foils: Compilation of data after 1972. Data Nucl Data Tables (1986) 34:357–91. 10.1016/0092-640x(86)90010-0

9.

ShimaKKunoNYamanouchiMTawaraM. Equilibrium charge fractions of ions of Z = 4–92 emerging from a carbon foil. Data Nucl Data Tables (1992) 51:173–241. 10.1016/0092-640x(92)90001-x

10.

WoodgateGK. Elementary atomic structure. Clarendon Press, Oxford, New York and Oxford Science Publications (1983).

11.

SchmittC. J. (2010). Equilibrium charge state distributions of low-z ions incident on thin self-supporting foils. Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame, Indiana and Christopher J. Schmitt.

12.

NikolaevV. S.DmitrievI. S. (1968). On the equilibrium charge distribution in heavy element ion beams. Phys. Lett.28A:277–278. 10.1016/0375-9601(68)90282-X

13.

ToK. X.DrouinR.Equilibrium-charge-state distribution studies of energetic boron ions in carbon and observation of doubly excited states in B III. Physics Scripta (1976) 14:277-280. 10.1088/0031-8949/14/6/006

14.

ToK. X.DrouinR.Semi-empirical determination of the charge states of a fast ion beam (Z<=18). Nucl. Instr. And Meth. (1978) 160:461-463. 10.1016/0029-554X(79)90201-5

15.

ShimaKIshiharaTMikumoT. Empirical formula for the average equilibrium charge-state of heavy ions behind various foils. Nucl Instr Meth (1982) 200:605–8. 10.1016/0167-5087(82)90493-8

16.

SchiwietzGGrandePL. Improved charge-state formulas. Nucl Instr Meth Phys Res B (2001) 175:125–31. 10.1016/s0168-583x(00)00583-8

17.

SchiwietzGCzerskiKRothMStaufenbielFGrandePL. Femtosecond dynamics – snapshots of the early ion-track evolution. Nucl Instr Meth Phys Res B (2004) 226:683–704. 10.1016/j.nimb.2004.05.043

18.

BranditWLaubertRMourinoMSchwarzschildA. Dynamic screening of projectile charges in solids measured by target X-ray emission. Phys Rev Lett (1973) 30:358–61. 10.1103/physrevlett.30.358

19.

RozetJPStephanCVernhetD. Etacha: A program for calculating charge states at GANIL energies. Nucl Instr Meth Phys Res B (1996) 107:67–70. 10.1016/0168-583x(95)00800-4

20.

ScheidenbergerC.StohlkerT. H.MeyerhofW. E.GeisselH.MoklerP. H.BlankB.et alCharge states of relativistic heavy ions in matterNucl. Instr. And Meth. Phys. Res. B. (1998) 142:441-462. 10.1016/s0168-583x(98)00244-4

21.

WincklerN.RybalchenkoA.ShevelkoV. P.Al-TuranyM.KolleggerT.StöhlkerT. H.et alBREIT code: Analytical solution of the balance rate equations for charge‐state evolutions of heavy-ion beams in matterNucl. Instr. And Meth. Phys. Res. B. (2017) 392:67–73. 10.1016/j.nimb.2016.11.035

22.

KhuyagbaatarJ.AckermannD.AnderssonL.-L.BallofJ.BrüchleW.DüllmannCh.E.et alStudy of the average charge states of 188Pb and 252,254No ions at the gas-filled separator TASCANucl. Instr. And Meth. Phys. Res. A. (2012) 689:40–46. 10.1016/j.nima.2012.06.007

23.

OganessianY. T.UtyonkovV. K.SolovyevD. I.AbdullinF. S.DmitrievS. N.IbadullayevD.et alAverage charge states of heavy ions in rarefied hydrogenNucl. Instr. Meth. Phys. Res. A. (2023) 1048:167978.

24.

LamourEFainsteinPDGalassiMPrigentCRamirezCARivarola RozetJet alExtension of charge-state-distribution calculations for ion-solid collisions towards low velocities and many-electron ions. Phys Rev A (2015) 92:042703. 10.1103/physreva.92.042703

25.

SharmaP.NandiT.X-ray spectroscopy: An experimental technique to measure charge state distribution during ion‐solid interactionPhys. Lett. A. (2015) 160:1–6. 10.1016/j.physleta.2015.09.031

26.

IshiharaT.ShimaK.KimuraT.IshiiS.MomoiT.YamaguchiH.et alEquilibrium charge state distributions of fast Si and Cl ions in carbon and gold foilsNucl. Inst. and Meth. (1982) 204:235-243. 10.1016/0167-5087(82)90102-8

27.

TolstikhinaI.ImaiM.WincklerN.ShevelkoV.Basic Atomic Interactions of Accelerated Heavy Ions in Matter. Springer Ser At Opt Plasma Phys (2018) 98.

28.

DayMEbelM. Wake-bound states: Dispersive and surface effects. Phys Rev B (1979) 19:3434–40. 10.1103/physrevb.19.3434

29.

SchiwietzGSchneiderDTanisJ. Formation of Rydberg states in fast ions penetrating thin carbon-foil and gas targets. Phys Rev Lett (1987) 59:1561–4. 10.1103/physrevlett.59.1561

30.

KemmlerJBurgdorferJReinholdCO. Theory of thel-state population of Rydberg states formed in ion-solid collisions. Phys Rev A (1991) 44:2993–3000. 10.1103/physreva.44.2993

31.

NandiT. Formation of the circular rydberg states in ion-solid collisions. Astrophys J (2008) 673:L103–6. 10.1086/527319

32.

SwamiDKNandiT. Present status of theoretical understanding of charge changing processes at low beam energies. Radi Phys Chem (2018) 153:120–30. 10.1016/j.radphyschem.2018.08.034

33.

LapickiGLosonskyW. Electron capture from inner shells by fully stripped ions. Phys Rev A (1977) 15:896–905. 10.1103/physreva.15.896

34.

MayR. Formation of highly excited neutral atoms by charge-exchange. Phys Lett (1964) 11:33–4. 10.1016/0031-9163(64)90244-6

35.

NikolovV. S.Calculation of the effective cross sections for proton charge exchange in collisions with multi-electron atoms. J. Exptl. Theoret. Phys. (1966) 51:1263-1280.

36.

SharmaPNandiT. Experimental evidence of beam-foil plasma creation during ion-solid interaction. Phys Plasma (2016) 23:083102. 10.1063/1.4960042

37.

NikolovN.TeplovaY. A.Methods of estimation of equilibrium charge distribution of ions in solid and gaseous media. Phys. Lett. A. (2014) 378:1286–1289. 10.1016/j.physleta.2014.03.004

38.

ChatterjeeSSharmaPSinghSOswalMKumarSMontanariCCet alSignificance of the high charge state of projectile ions inside the target and its role in electron capture leading to target-ionization phenomena. Phys Rev A (2021) 104:022810. 10.1103/physreva.104.022810

Summary

Keywords

ion–solid collision, charge state distribution, mean charge state, electron capture and loss process, non-radiative electron capture, exit surface effect, Fermi effect

Citation

Swami DK, Kumar S, Singh B and Karn RK (2023) Exploring the influence of target atomic number () on mean equilibrium charge state (: A comprehensive study. Front. Phys. 11:1145632. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2023.1145632

Received

16 January 2023

Accepted

09 March 2023

Published

28 March 2023

Volume

11 - 2023

Edited by

Mukesh Ranjan, Institute for Plasma Research (IPR), India

Reviewed by

Dharmendra Singh, Central University of Jharkhand, India

Nissar Ahmad Keen, University of Kashmir, India

Hardev Singh, Kurukshetra University, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Swami, Kumar, Singh and Karn.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: D. K. Swami, swami@iuac.res.in; Sarvesh Kumar, sarvesh.sharma67@gmail.com

ORCID: D. K. Swami, orcid.org/0000-0002-8135-4702; Sarvesh Kumar, orcid.org/0000-0002-1996-9925

This article was submitted to Condensed Matter Physics, a section of the journal Frontiers in Physics

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.