Abstract

We theoretically prove that it is possible to realize strong photon blockade at n-order exceptional points (EPn) in a two-level quantum emitter (QE)–cavity quantum electrodynamics (QED) system even if the emitter–cavity coupling strength is weak. When the single-mode cavity is gain, we show that the ultrastrong single-photon blockade (1 PB) emerges at two-order exceptional points (EP2), avoiding the strong non-linearity of the system. In addition, we first give the pseudo-Hermitian condition for the non-Hermitian cavity QED system and find that the third-order exceptional points (EP3) can be predicted under certain constraints of the parameters. For this case, the pronounced 1 PB at EP3 will be triggered. Furthermore, we also consider the usual EP2-enhanced 1 PB existing in the system with or without the dipole–dipole interaction (DDI) under the pseudo-Hermitian condition. A striking feature is that the system without DDI can realize more obvious 1 PB at EP2 than the case of with DDI. What is important is that both EP2 and EP3 will appear in the weak coupling regime. Our proposal sheds new light on strong EP-engineered photon blockade in the weak coupling regime, providing a unique platform for making high-quality single-photon sources.

1 Introduction

As a significant area of quantum optics, the generation and manipulation of single photons have been making great strides in the past few decades and possess a wide array of applications in the fields of quantum communications [1], quantum cryptography [2], and quantum information processing [3-4]. One of the basic physical mechanisms for generating single photons is the photon blockade (PB) effect. What we called PB is that the first photon within an optical system will block the transmission of the second photon, leading to the phenomenon of photon antibunching in the system. This effect is first produced by Imamoglu et al. in 1997 [5], which plays key roles in exchanging and dealing with photonic quantum information [6–8].

So far, there are two main methods that have been used to generate strong photon blockade effects. One is the conventional photon blockade (CPB), and the other is the unconventional photon blockade (UPB). The CPB schemes require strong non-linear interactions between polaritons, which lead to a quantum anharmonic ladder in the energy spectrum. If a photon is tuned to resonantly excite the system from its ground state to the lowest excited states, the population of the two-photon state will be suppressed and only one photon is allowed in the system. The CPB effect has been achieved in various systems, including atom–cavity QED systems [10-12], cavity optomechanical systems [14], spinning Kerr cavity [16-17], and superconducting qubit systems [18-19].

Different from CPB, the physical mechanism of UPB relies on the quantum destructive interference between two or more quantum transition pathways in weakly non-linear systems. In the experiment, the phenomenon of UPB can be observed in the quantum dot–cavity QED system [21–23] and coupled superconducting resonators [24]. With the development of experiments, theoretical research has also been expanded in different quantum systems, for example, the couple cavities with second-order or third-order non-linearities [25–27], the cavity QED systems based on whispering-gallery-mode resonators [28-29], and the non-reciprocal devices such as spinning optomechanical systems [30].

Although both CPB and UPB can realize photon blockade, each type of PB has its own disadvantages in practice. Specifically, the realization of CPB depends on the strong light–matter interaction of the system, which is a big challenge in a few quantum systems. In particular, a fundamental CPB system typically requires a microcavity with a high Q factor [31], which is difficult to fabricate due to technical limitations. As for UPB, it may be hard to realize strong PB with large average photon numbers, resulting in the difficulty to obtain high-quality single-photons.

To solve these problems existing in the system, researchers try to achieve strong PB at the critical points, especially at exceptional points (EPs). EPs can be treated as critical points of the quantum phase transition from the PT-symmetric phase to the PT-symmetric-broken phase, where two or more eigenvalues and corresponding eigenvectors simultaneously coalesce [32–34]. EPs are one of the peculiar characteristics of the non-Hermitian systems [35], and there are lots of fascinating phenomena around these points such as single-mode lasers [36-37], unidirectional invisibility [38–40], sensitive enhancement [41–45], and topological energy transfer [46-47]. Very recently, EP-tuned purely quantum effects and their applications have been researched like non-reciprocal devices [48–50] and steady Bell-state generation [51].

Additionally, Mostafazadeh defined a new Hamiltonian that exists in the non-Hermitian systems, i.e., pseudo-Hermitian Hamiltonian [52–54]: a Hamiltonian H with a discrete spectrum that satisfies , where U is a linear Hermitian operator. The eigenvalues of this Hamiltonian are either real or complex conjugate pairs. So far, pseudo-Hermiticity plays an important role in the formation of higher-order exceptional points [55] and gives rise to a rich phenomenon in different fields of physics [56–58].

In this work, we theoretically propose a cavity QED system consisting of a gain single-mode cavity and a pair of two-level quantum emitters (QEs). First, we analytically demonstrate that the use of the gain cavity can provide relatively strong PB compared with the loss cavity even if the QE-cavity coupling strength is weak. For this case, we further prove that EP2 can be predicted in parameter space when the cavity and the QEs share the same frequency detuning. At EP2, we can obtain ultrastrong photon blockade effects with large mean photon numbers. Then, we prove that EP3 can be predicted in this system under the pseudo-Hermitian conditions. At this operator regime, the strong PB phenomenon can still be found. Compared with the PB effect that occurs at EP3 and EP2, we find that the PB effect enhanced at EP2 is stronger than that enhanced at EP3. Our proposal provides a new method to realize strong single-photon blockade in the weak coupling regime.

The paper is organized as follows: in Section 2, we give a detailed description of the physical model. By analytically solving a group of dynamics equations, we can obtain the expression of the second-order correlation function and mean photon number. Then, we discuss the origin of the PB effect in the normal loss cavity. In Section 3, we demonstrate that the strong PB effect can be achieved at EP2 in the weak coupling regime, and the physical mechanism can be analyzed in different quantum phase transition regions. In Section 4, we derive the pseudo-Hermitian condition for this considered system; both EP3 and EP2 can be predicted under specific parameter conditions. We study the EP3-enhanced strong PB phenomenon in Section 5. In Section 6, we compared the PB effect enhanced at EP3 and EP2 under different pseudo-Hermitian conditions. Finally, we give the conclusion of the whole work in Section 7.

2 Physical system of the two-level QE-cavity QED system

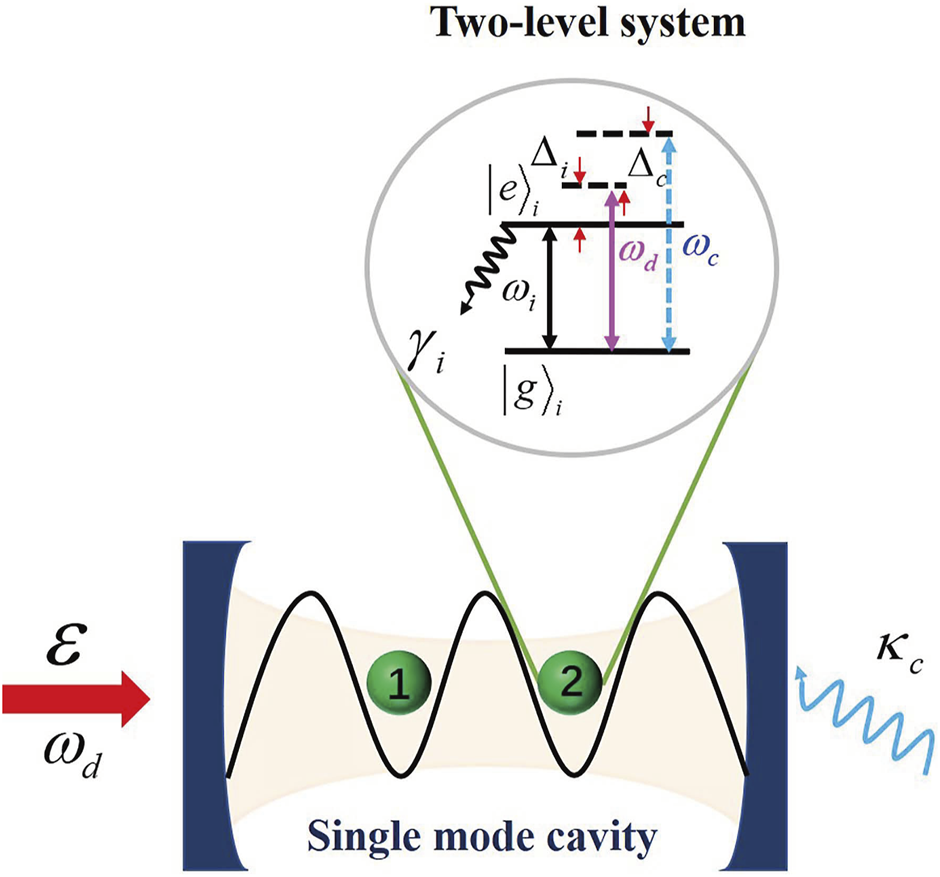

We construct two two-level QEs (e.g., two-level atoms, molecules, ions, or quantum dots) with the resonant frequency located in a single-mode cavity with the resonant frequency . The ground (excited) QE state is expressed as , and denotes the coupling strength between the QE and single-mode cavity. This cavity is coherently driven by a classical field with the Rabi frequency and pump frequency , as illustrated in Figure 1. Using the rotating-wave approximation, the Hamiltonian of the system can be described as (setting )where and are the cavity and QEi frequency detunings, respectively. Here, is the annihilation (creation) operator of the cavity mode and is the lowering operator of the ith two-level QE.

FIGURE 1

Schematic illustration of the two-level quantum emitter (QE)–cavity QED system with the cavity-mode frequency and QEi resonant frequency . A classical field with the intensity and the angular frequency is used to drive the cavity. Here, and represent the ground state and excited state of QEi, respectively. is the effective decay rate of the cavity, and is the decay rate of QEi.

The dynamics of this cavity-driven QED system is governed by the quantum master equation:where is the system density matrix and the Liouvillian operators and describe the cavity decay rate with and the QEs with rate , respectively. In the case of weak driving, we can neglect the quantum jump term to obtain the effective non-Hermitian Hamiltonian:Here, we take in the following calculation.

In order to give a better understanding of the PB effect from the physical point of view, we need to calculate the zero-delayed second-order correlation function . Under the weak driving assumption, i.e., (in this paper, we only analyze the case of weak drive), we assume that the total excitation number of the system is truncated to 2. As a result, the time-dependent wave function can be written aswhere is the coefficient of the quantum state . r stands for the photon number in the cavity. and 1 represent the two QEs in the ground states and excited states, respectively. First of all, it is necessary to obtain the steady-state solution of . We start from solving the Schrodinger equation and then obtain a set of equations of motion for coefficients:where . Under the weak driving condition, one can assume that . By setting , we can easily obtain the steady-state solution of the aforementioned equations, which are expressed aswhere and the determinant

According to Eqs 6–8, the second-order correlation function can be approximately yielded by and the mean photon number in the cavity is . The expression of can be expanded as

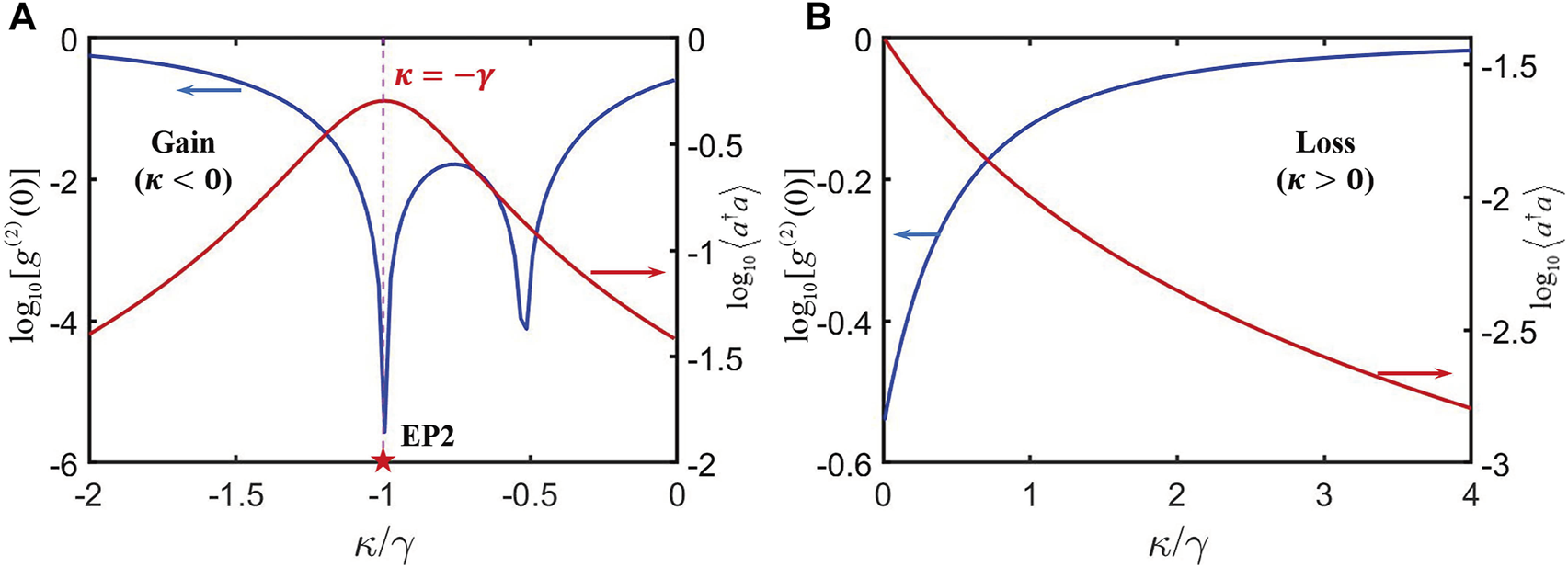

2.1 The PB in the QE-cavity QED system with the gain (loss) cavity

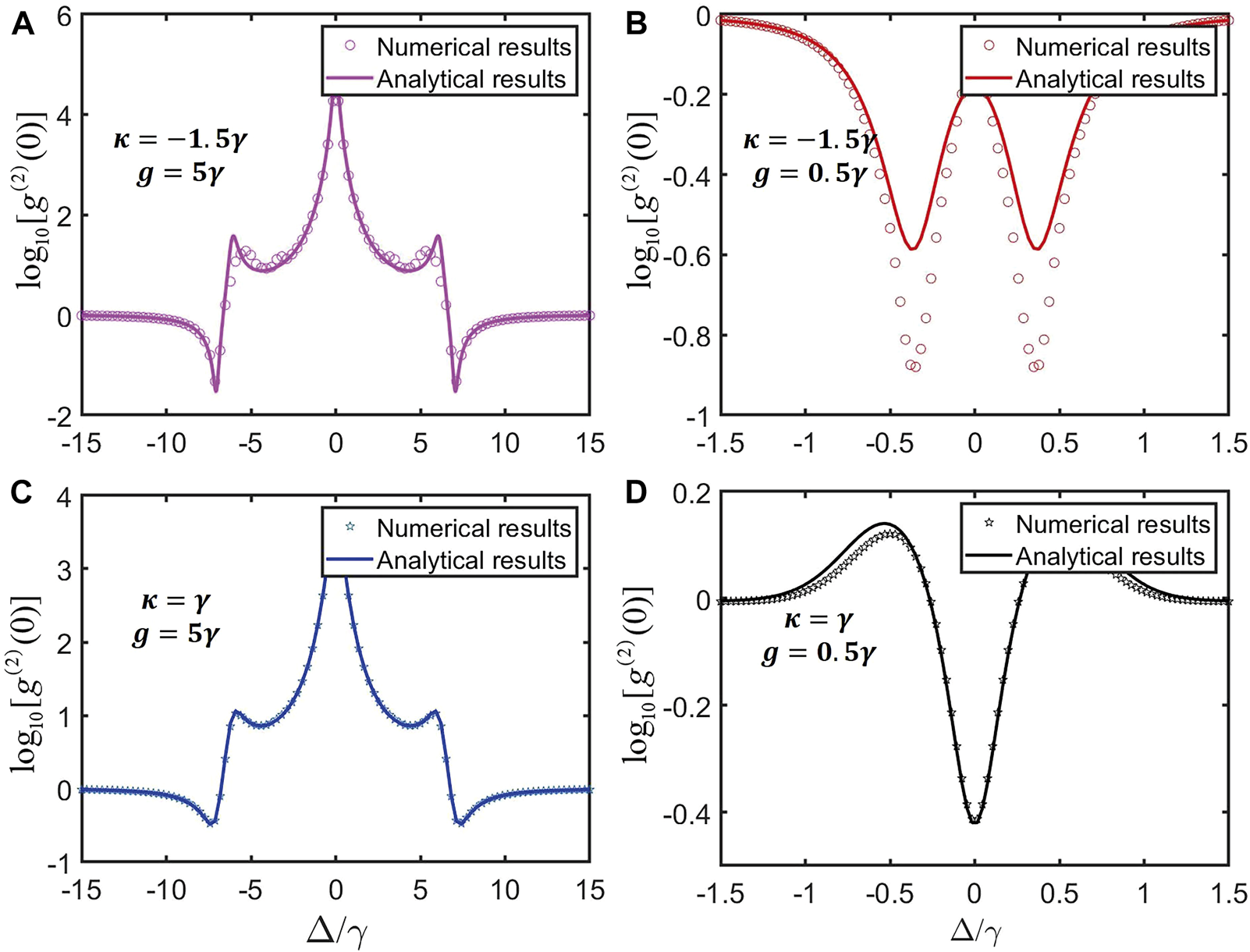

For simplicity, we assume that the two-level QE-cavity coupling strengths are the same (i.e., ) and that the QE and cavity frequency detunings are also identical (i.e., ) in this section. Next, we prove the validity of our previous calculations by comparing the analytical results with the numerical results given by Eq. 2 under the weak driving assumption shown in Figure 2. The analytical results are in good agreement with the numerical results for the second-order correlation function. In the same strong coupling regime, the use of the gain cavity can show more obvious photon blockade effects (See Figures 2A,C). As for the same weak coupling regime, the choice of the active or passive cavity has a little effect on PB effects (See Figures 2B,D). Therefore, it is worth presenting a new physical model for realizing strong PB effects at a specific area in the weak coupling regime.

FIGURE 2

In the system with the gain (dissipation) cavity, the logarithmic plots of the second-order correlation function as a function of the normalized detuning for two cases: (A, C) the system in the strong coupling regime, while (B, D) in the weak coupling regime. Here, the other parameters are chosen as . The driving strength takes as in the following figures.

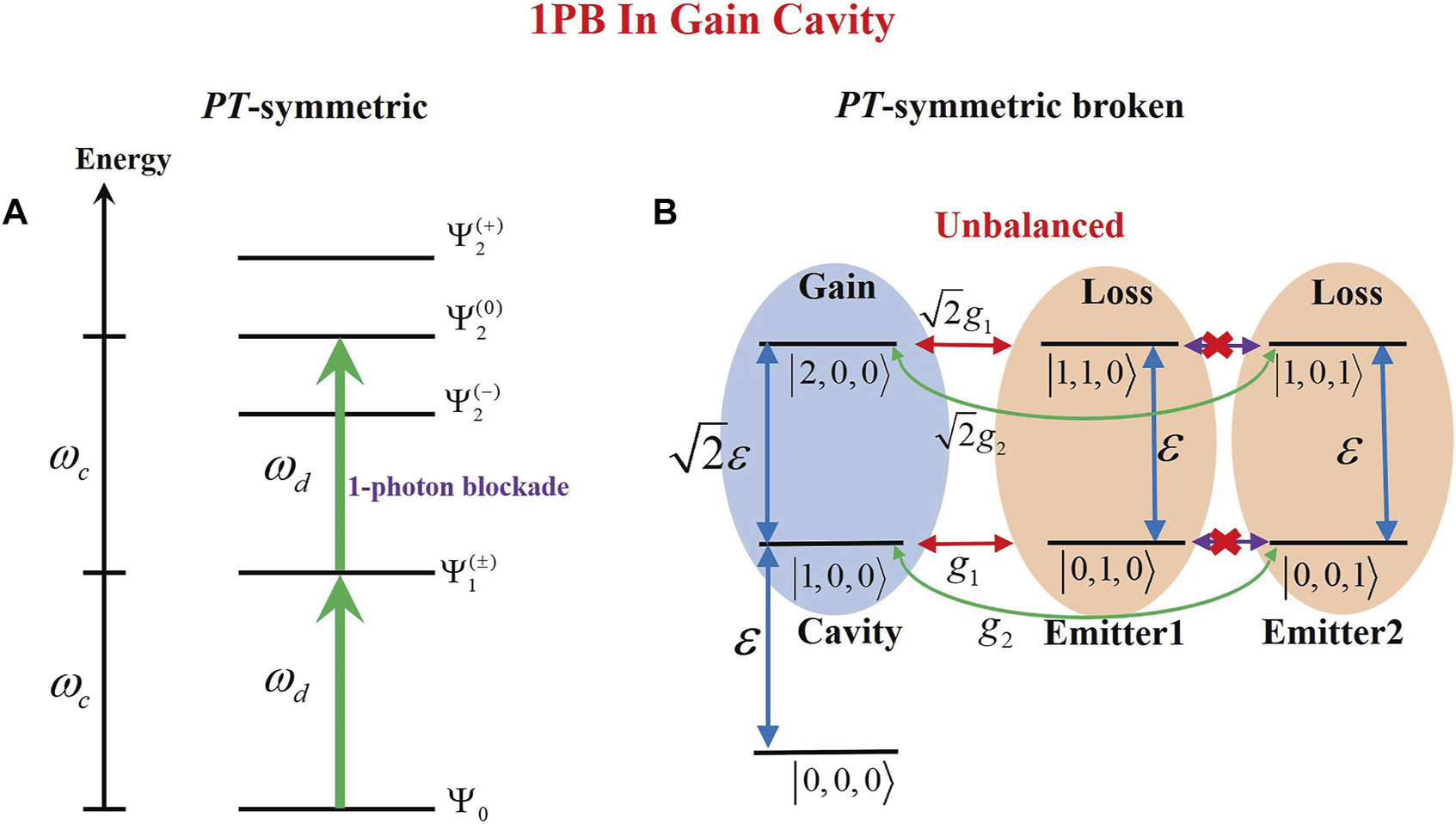

For a better understanding of the physical mechanism of the PB effect in the system with the loss- or gain-cavity mode, we consider the system by utilizing the dressed-state representation. Specifically, this coupled system has a discrete spectrum consisting of a ladder-type dressed state, with separated energy levels and other collective states are and [59]. Owing to the whole system being under the weak driving assumption, the principal quantum number of the system is truncated to .

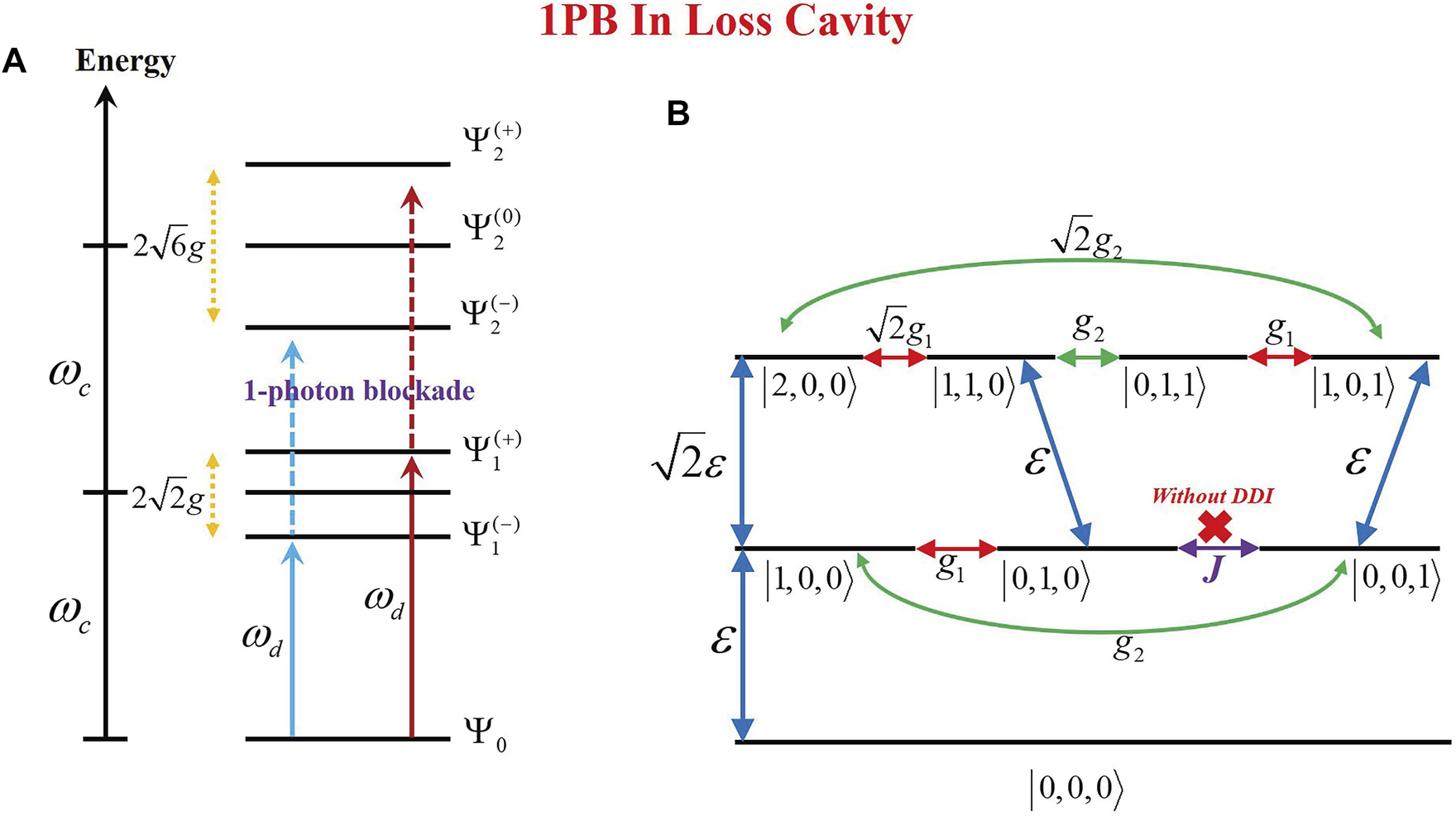

In the case of the loss cavity, when a photon is resonantly excited from the ground state of the system to the states of the lowest doublet, i.e., , the absorption of the subsequent photon at the identical pump frequency will be blocked due to the large mismatch energy induced by energy-level anharmonicity (see Figure 3A). This is the blockade mechanism of the well-known CPB scheme.

FIGURE 3

(A) Anharmonic ladder-type energy-level diagram to explain the PB effect in the system with the loss cavity. (B) Quantum transition pathways of the system for different quantum states .

Neglecting the dipole–dipole interaction (DDI) between two QEs, there is a direct transition pathway induced by the pump field, i.e., and two indirect pathways induced by the QE-cavity coupling strengths, i.e., and (see Figure 3B). The direct transition pathway for the two-photon excited states will be forbidden, owing to the quantum destructive interference with the indirect pathways [32-60]. Consequently, the probability of the two-photon excited states will be reduced, which means that the weak coupling condition can still induce the PB effect. This is the blockade mechanism of the UPB scheme.

2.2 The exceptional point of the system with the gain cavity

In this section, we study the strong PB at a certain characteristic value in a weak coupling limit. This QE-cavity QED system can be described by the Hamiltonian without a driving term in the matrix form as

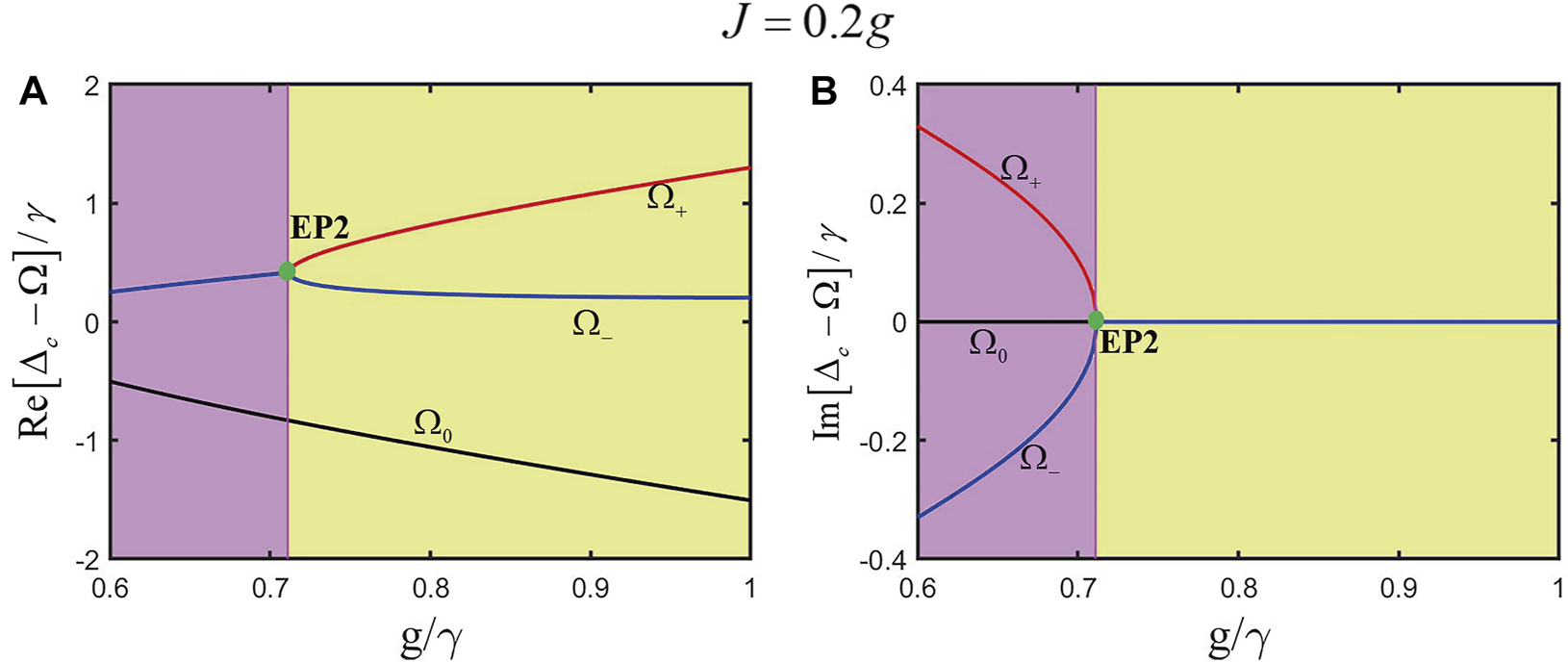

Here, we choose and . The eigenvalues of the system in single-photon space are expressed aswith the corresponding eigenvectors given by

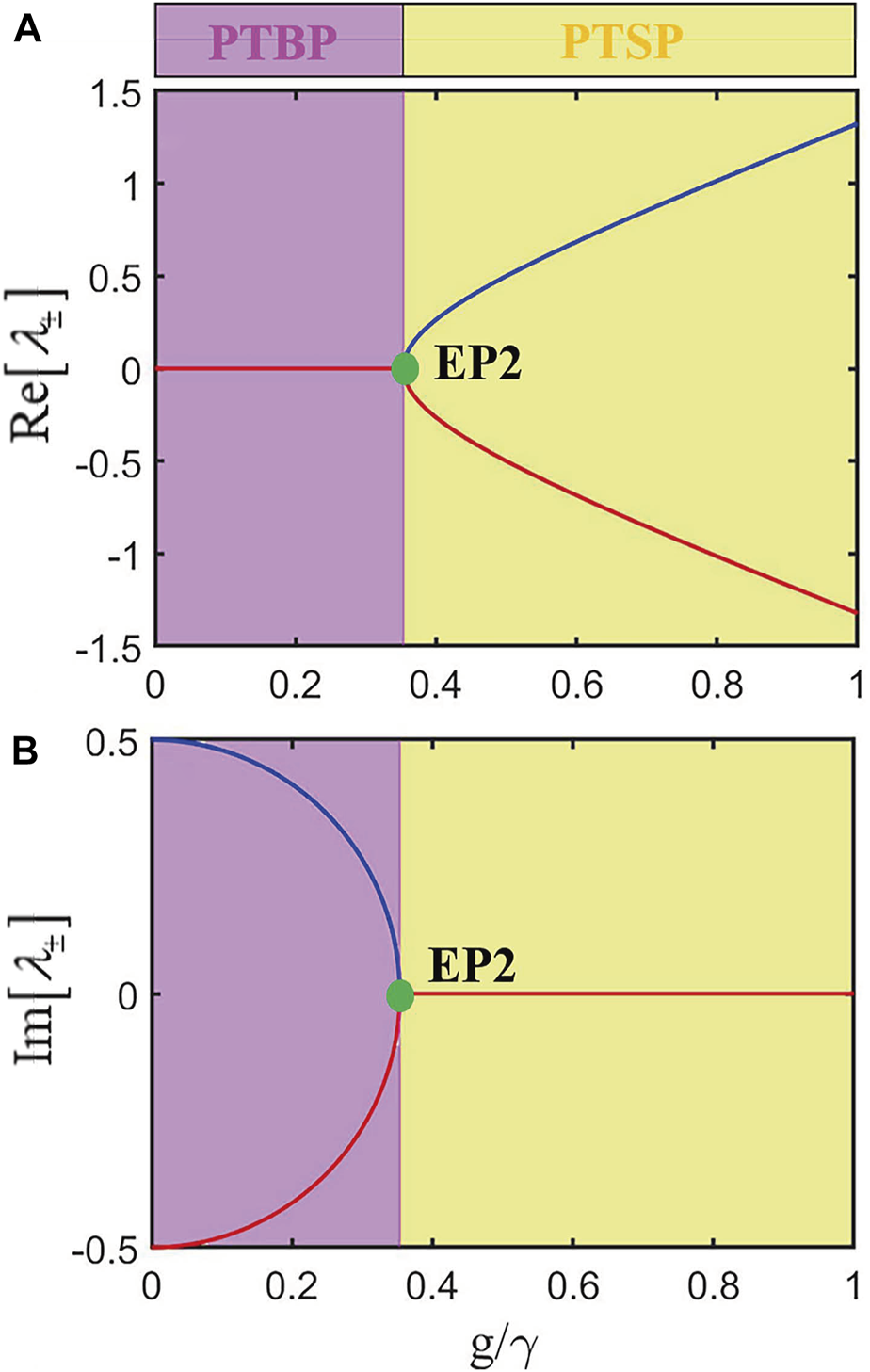

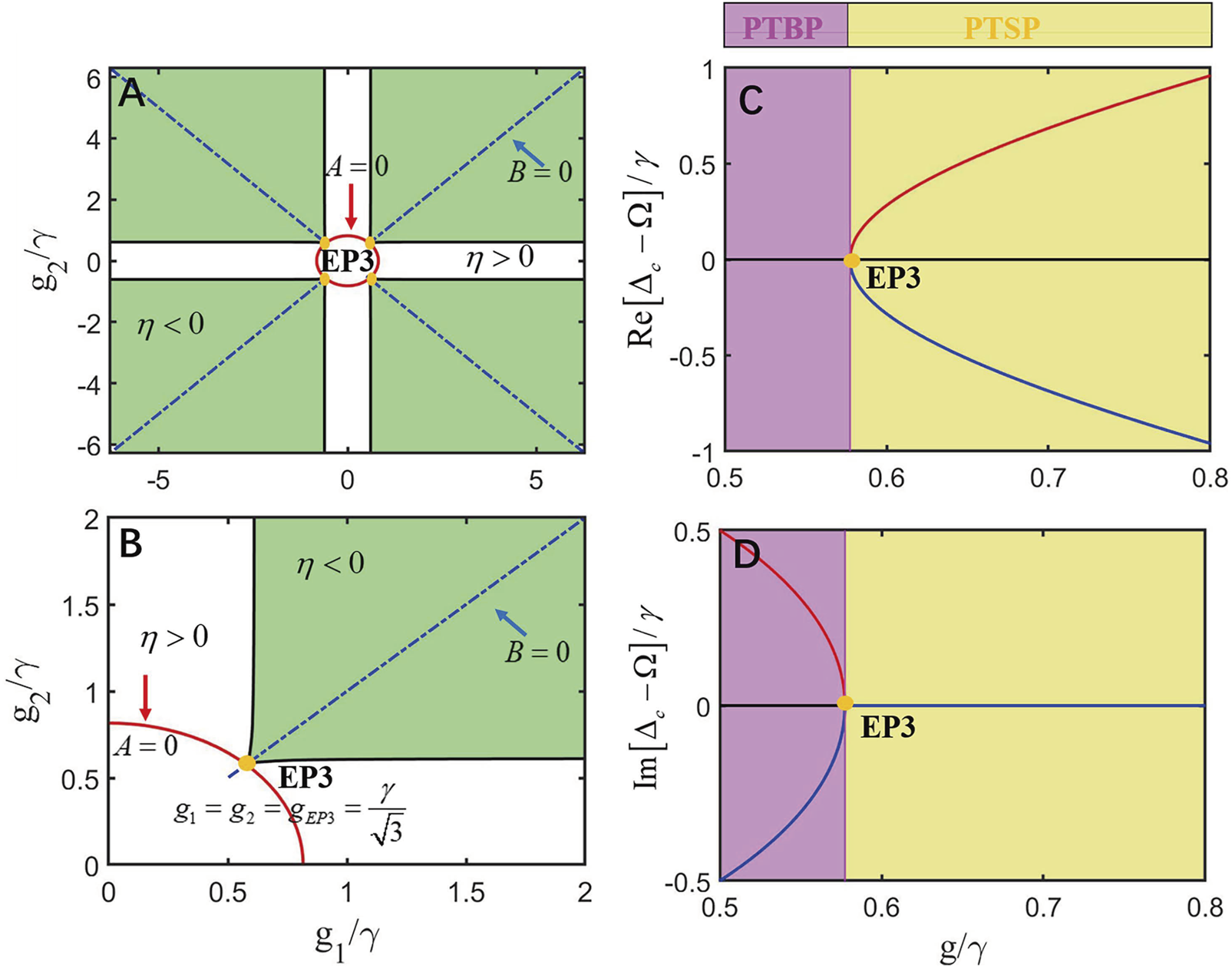

According to Eq. 11, we find that when , the two eigenvalues and the corresponding eigenvectors will coalesce simultaneously, which indicates that the second-order exceptional point (EP2) will appear. Considering special circumstances, we think the two-level QE-cavity system has the same coupling strength, i.e., . In Figure 4, we plot the real [see Figure 4A] and imaginary parts [see Figure 4B] of eigenvalues as a function of the coupling strength g. For the case of , the two eigenvalues are real and non-degenerate, indicating that the system is in the PT-symmetric phase (PTSP). When , the eigenvalue is a pair of complex conjugates, which is the significant feature of the PT-symmetry-broken phase (PTBP). When , both the eigenvalues and corresponding eigenvectors are degenerated. The pink and yellow areas indicate the PT-symmetric phase and PT-symmetry-broken phase, respectively. Subsequently, we will analyze the single-photon blockade effect at and around EP2.

FIGURE 4

(A) Real and (B) imaginary parts of the eigenvalues are obtained by Eq. 12 with versus the same coupling strength g (i.e.; ). Green dots show the position of EP2 when . The pink and yellow areas represent the PT-symmetric phase (PTSP) and PT-symmetry-broken phase (PTBP) area, respectively.

3 EP2-enhanced strong PB effects in the system

In order to demonstrate the optimal photon blockade at EP2, we plot both the mean photon number and second-order correlation function in two scenarios: i) the system with the gain cavity (i.e., ) or ii) with the dissipation (i.e., ) cavity, as shown in Figure 5. It is easy to find that when , the ideal photon blockade will appear at , where the minimal value of and the maximum value of will be achieved simultaneously. For the case of the system with the gain cavity, there are two dips, one of which is located at EP2. However, for the cases of loss cavity, with the increase in the dissipation rate of the cavity, the PB effect will decrease rapidly. Therefore, compared with the gain cavity and loss cavity, the gain cavity provides a new possibility for imperfect photon blockade.

FIGURE 5

Second-order correlation function and the mean photon number as functions of in the system with the gain cavity (Panel (A)) and with the loss cavity (Panel (B)). Here, we take the coupling regime at and and the other parameters are same as those in the main text.

Furthermore, we can prove the optimal photon blockade at EP2 by calculating the value of . By setting in Eq. 9, we can seek out the positions where the pronounced photon antibunching phenomenon appears. The realization of the minimum value of requires , that is,

Therefore, the strong PB effect can be obtained around for . We noted that the coefficient of when , which indicates that will reach its maximum value and will reach its maximum value at .

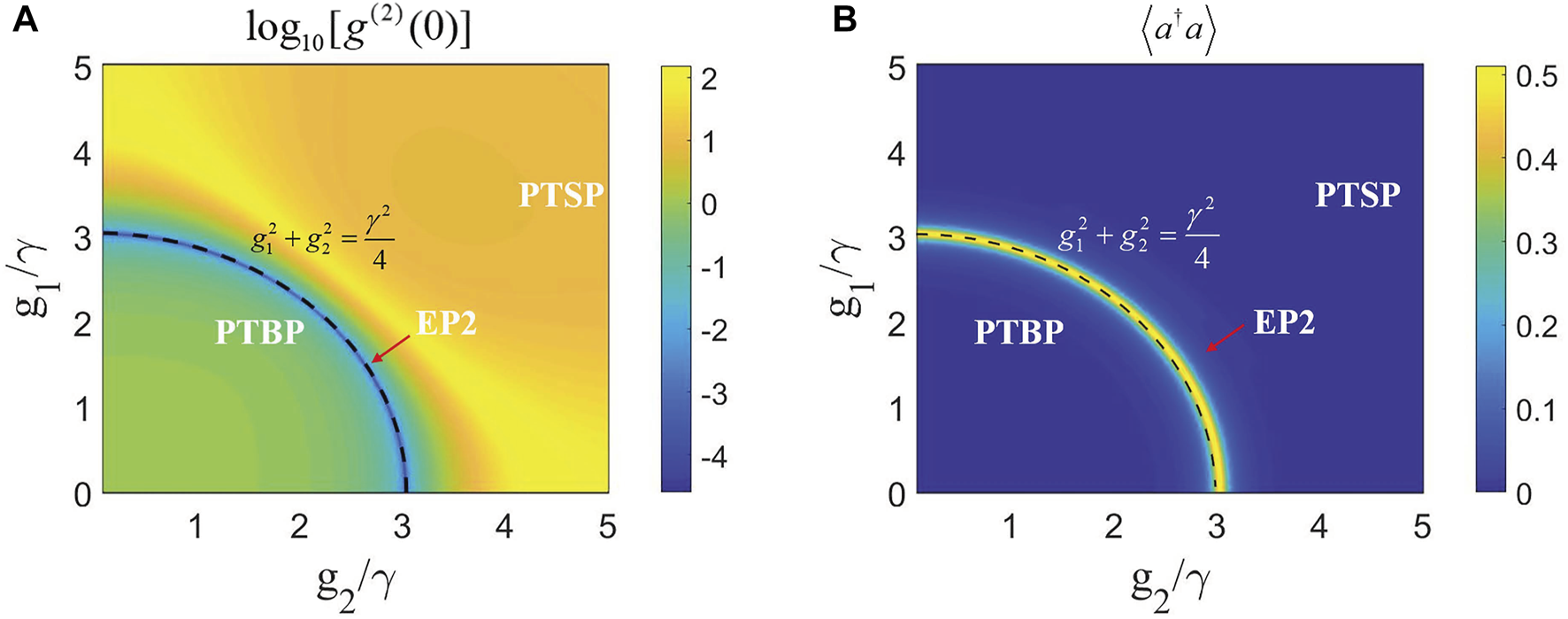

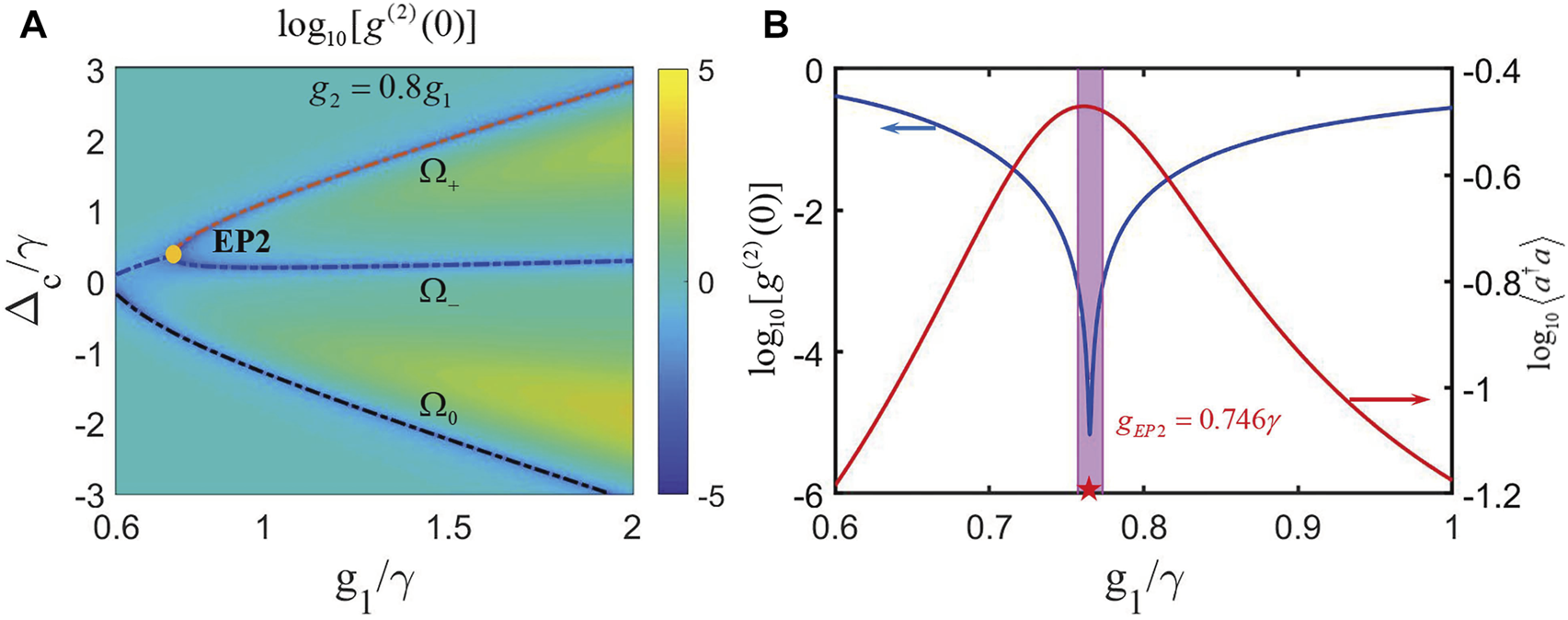

For the general case of , we plot (see Figure 6A) and (see Figure 6B) in terms of and , respectively. The black dashed lines of EP2 denote the optimal condition of the PB effect, i.e., . Under this optimal condition, of the PB effect may reduce to and will increase to 0.32. For better proof that the PB effect enhanced at EP2, as shown in Figure 7A, we provide as functions of normalized detuning and the same coupling strength . It is worth pointing out that the EP2 will be emerged at , indicating that the strong PB phenomenon has occurred in a weak coupling limit. This result is demonstrated in Figure 7B.

FIGURE 6

When the coupling strengths are different, i.e., , (A) the logarithmic plots of and (B) are as functions of the coupling strengths and . The black dashed lines indicate the area of EP2 in the condition of . The other parameters are similar to those in Figure 4.

FIGURE 7

EP2-enhanced strong PB effect in the condition of and . (A) Logarithmic plots of as functions of normalized detuning and the same coupling strength . The red circle shows the position of EP2, where the extremely small can be achieved. (B) Plots of (see blue curves) and (see red curves) versus the coupling strength . The pink dashed line indicates the position of EP2. We choose in panel (B).

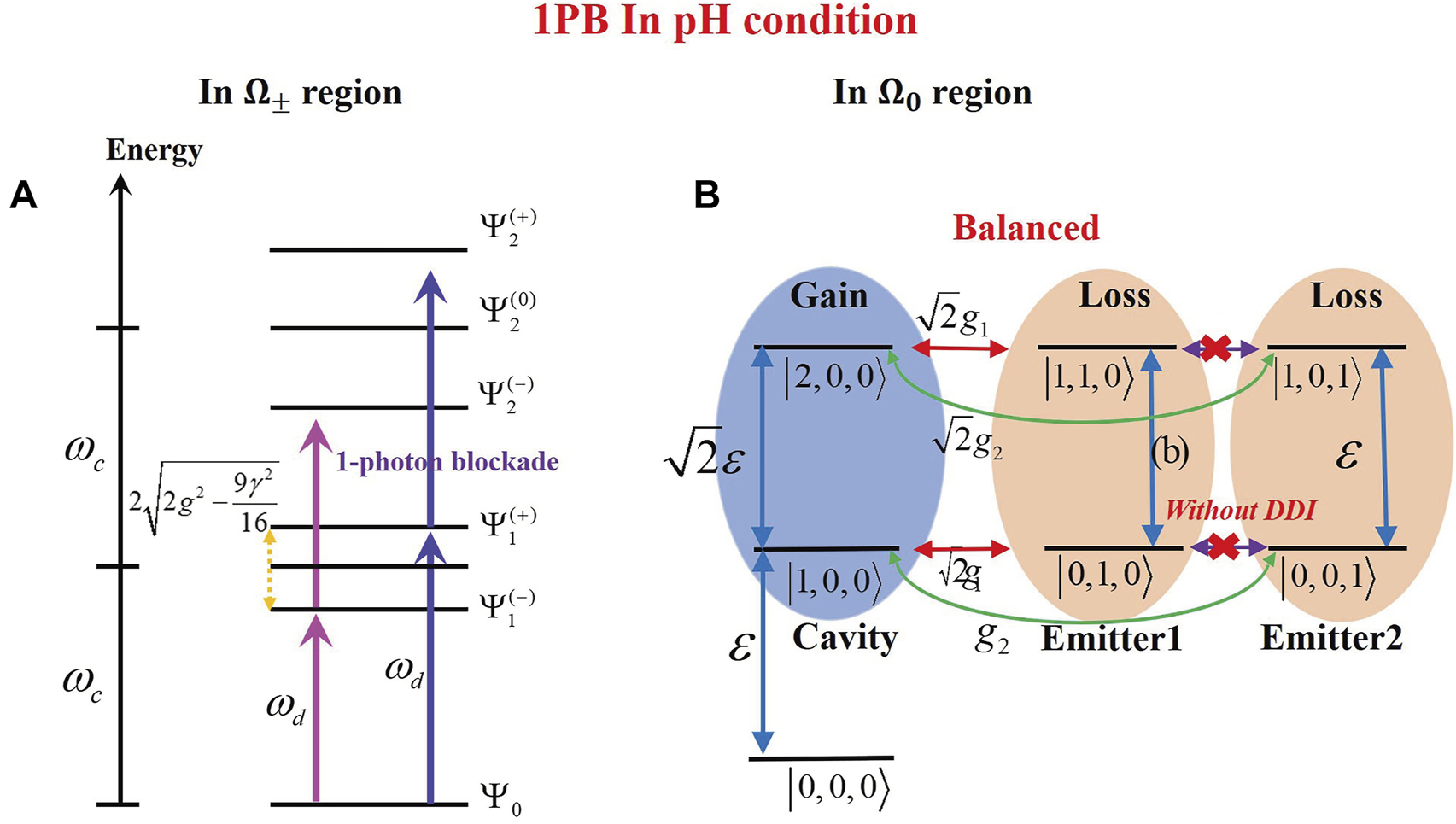

In the following section, we study the reason for the PB effect in different regions. On one hand, to explain the PB effect when (i.e., in the PT -symmetric region), we draw the ladder-type energy level of the quantum state, as shown in Figure 8A. According to the eigenvalues of the system, this physical mechanism can be understood as follows: when , the single-photon state is a single state. If the driving frequency equals to , a photon is excited from the ground state to the single excited state resonantly, so the single-photon probability increases dramatically. However, the two-photon excitation probability may decrease due to the detuning.

FIGURE 8

Level diagram of the quantum states for the cavity QED with the gain cavity under the weak cavity-driven assumption: (A) dressed states and (B) quantum states.

On the other hand, when , there are two quantum paths that suffer from different efforts, i.e., the photon gain in the path and the photon loss in the two paths, i.e., and . Therefore, the total loss and gain rate are unbalanced in this model. The gain of the photons in the cavity will compensate for the photon loss of the system, which makes the single-photon probability increase. This is the main reason for the PB effect occurring in the PT-symmetric-broken region. Through our calculation of the second-order correlation function by Eq. 9, one can easily adjust the coupling strength to realize the optimal photon blockade. Additionally, in the PT-symmetric-broken region (i.e., ), the photon blockade will be more obvious with the increase in the coupling strength g. However, in the PT-symmetric region (i.e., ), the photon antibunching phenomenon will be transformed into photon bunching with the increasing coupling strength.

4 Pseudo-Hermitian conditions for EP3 in the system

In addition to EP2, whether high-order exceptional points (i.e., EP3) will also affect the PB effect is worth studying. In this part, we further show the strong PB at EP3. First, we need to find the pseudo-Hermitian (pH) condition of the system. Following [52–54], the non-Hermitian Hamiltonian without DDI becomes pseudo-Hermitian when its eigenvalues satisfy one of the following conditions: i) all three eigenvalues are real or ii) one of the eigenvalues is real and the others are a pair of complex conjugates. Solving , i.e.,where I is an identity matrix. We can obtain three eigenvalues from Eq. 14. Then, in order to meet the pseudo-Hermitian condition, both Eq. 14 and its complex conjugation expression, i.e., should have the same solutions. Solving these two equations gives rise to the pseudo-Hermitian conditions of the Hamiltonian (14) aswhere is the frequency detuning of the cavity and QEs. In the following calculation, we give the conditions

From the first condition in Eq. 16, it is easy to see that the gain cavity must be introduced to the QED system to keep the gain and loss balanced. From the last equation in Eq. 16, it should satisfy the condition of . By setting , the relationship of minimal values of two-level QE-cavity coupling strength is given by , which is a basic condition that should be met in our system. When the system is pseudo-Hermitian, the characteristic equation can be specifically written aswhere

According to Cardano’s formula and methods [61], the solution of the characteristic equation in Eq. 16 can be determined by the discriminantwith . If , Eq. 17 has three real solutions, but the solutions are one real root and a pair of complex conjugates if . In the critical point at , these three real solutions coalesce to the same value, i.e., . In other words, when , EP3 will appear. If the Hamiltonian in Eq. 11 satisfies the conditions of (16), this non-Hermitian Hamiltonian will transform into a pseudo-Hermitian Hamiltonian.

To prove the aforementioned analysis, we plot the phase transition in Figure 9A, where the green and blank areas represent and , respectively. The black lines, blue dashed lines, and a red curve denote the conditions of , , and , respectively. The yellow crossing points produced by the black, blue, and red lines indicate EP3s in math. We can only find one EP3 in our system when two-level QE-cavity coupling strengths are the same, i.e., (see Figure 9B). Furthermore, we analytically prove this critical condition for the existence of EP3.

FIGURE 9

(A) Quantum phase of the discriminant in Eq. 19 under the pseudo-Hermitian conditions in Eq. 16 as a function of coupling strengths and . (B) The yellow dots represent the ranges of and are plotted to predict EP3. (C, D) Real and imaginary parts of the eigenvalues (see the black lines) and (see the red and blue lines) versus the same coupling strength in the conditions of Eq. 20.

We noted that when , the pseudo-Hermitian conditions in Eq. 16 reduce to

Moreover, the coefficients in Eq. 18 become

The discriminant in Eq. 19 is . We substitute the coefficients in Eq. 21 into Eq. 17 and obtained

Three roots can be obtained by solving the equation

It is obvious that the three real solutions coalesce into one when , i.e.,

This is EP3 of the proposed QE-cavity QED system. However, when , two roots of Eq. 17 coalesce to a typical point, , which means that EP3 transformed into EP2. To verify this result, we plot the real and imaginary parts of the eigenvalues of Eq. 17 in Figures 9C,D, respectively. We noted that the minimum value of the coupling strength is smaller than that of . Clearly, when , one eigenvalue is real and the other eigenvalue is a pair of complex conjugate. For , all three eigenvalues are real. At a critical point , these eigenvalues coalesce to EP3, i.e., .

5 EP3-enhanced strong PB effects in the system

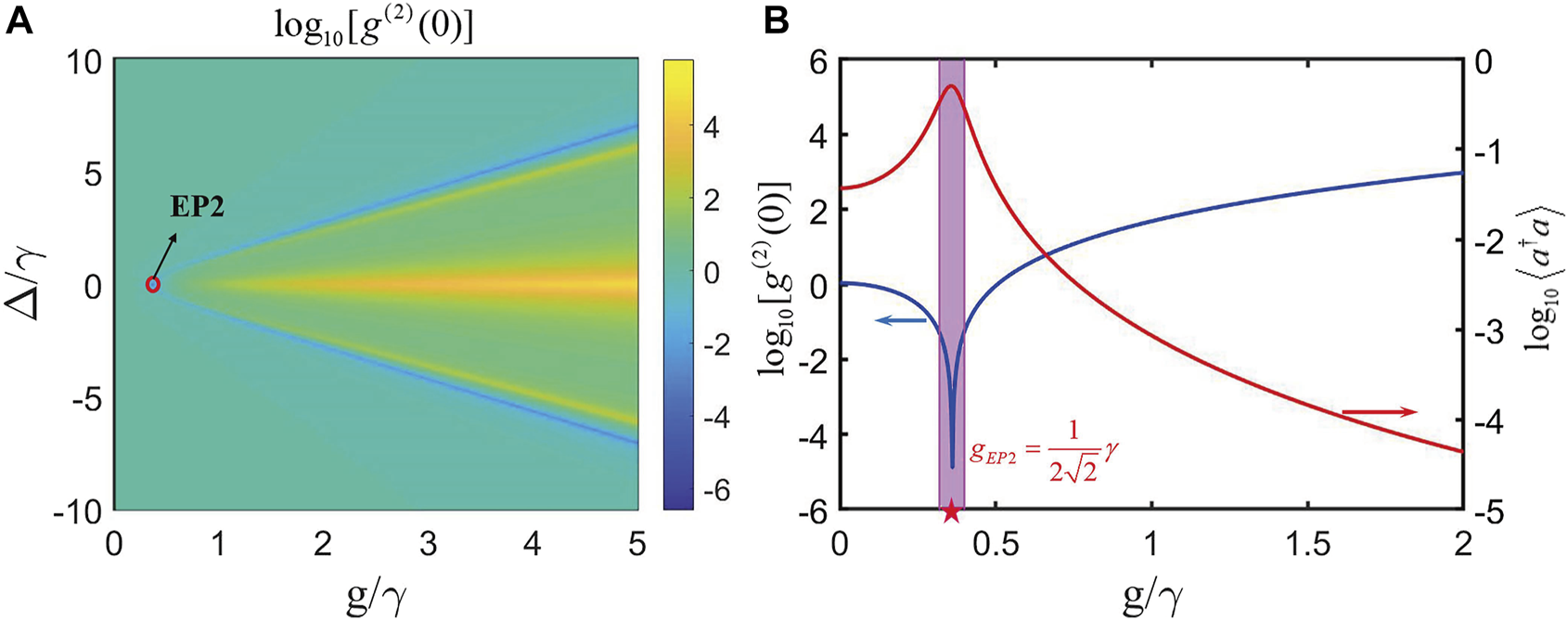

According to the analysis in Section 4, we demonstrate that there is a typical EP3 in the pseudo-Hermiticity condition. In this section, we will study the PB effect at EP3. First, in order to get the minimum value of , we should substitute Eq. 20 into Eq. 9, i.e.,

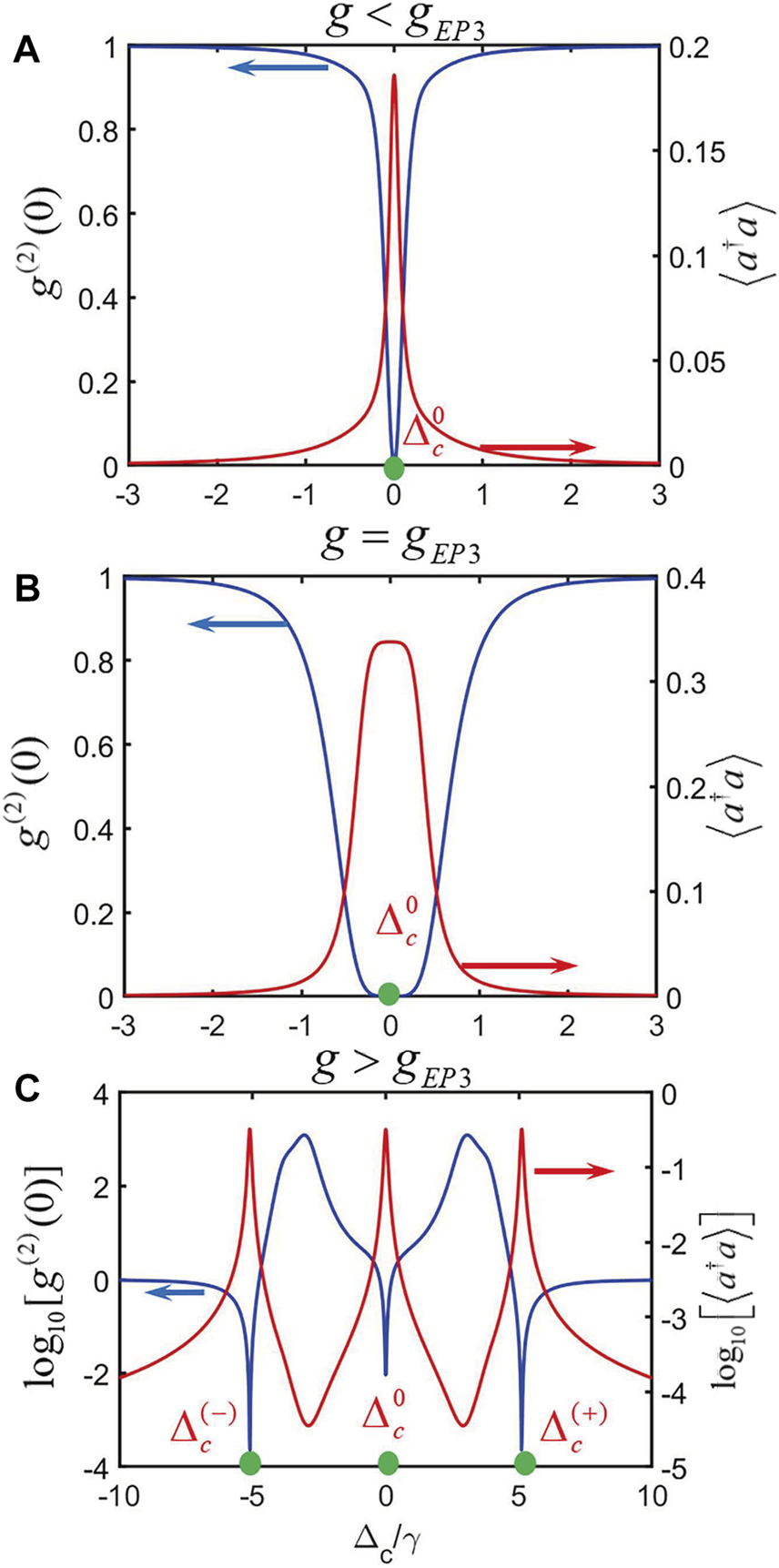

Therefore, we can obtain the conditions for as

Obviously, when (i.e., ), the corresponding cavity detuning at . This desired operator regime is found, which result in a strong photon blockade phenomenon, as shown in Figure 10B. In addition, when , only detuning is allowed. The maximum value of the mean number photon and the minimum value of can be achieved at this position, as described in Figure 10A. In the case of , all of the detunings in Eq. 26 are allowed, as shown in Figure 10C. Therefore, we can observe the PB effect in three regimes with the increase in the coupling strength. The aforementioned results exhibit that under pseudo-Hermiticity conditions, the strong PB phenomenon will be observed at EP3 even if the coupling strengths are weak.

FIGURE 10

Logarithmic plots of and as a function of the cavity frequency detuning in the cases of (A), (B), and (C). The green dots represent the optimal operator regime for the realization of the strong PB phenomenon at and .

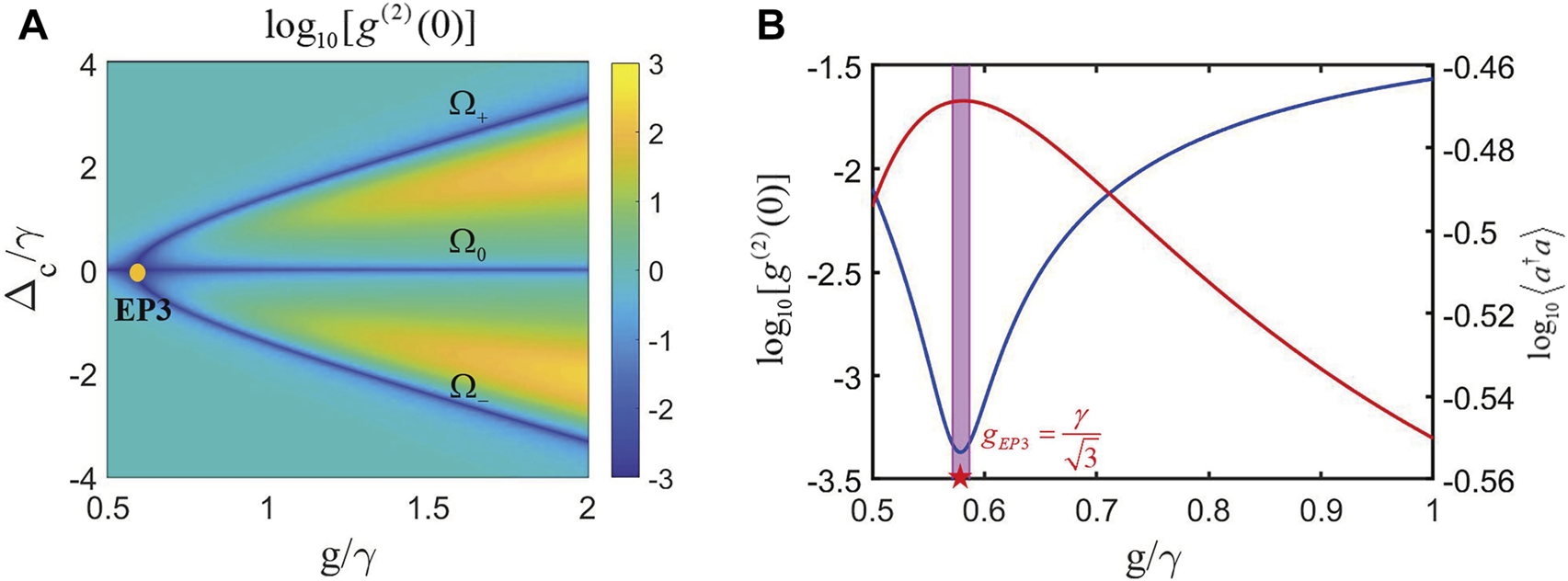

We can also find out EP3 in the logarithmic plot of as functions of the normalized detuning and QE-cavity coupling strength , which is shown in Figure 11A. The strong PB phenomenon is obtained at , which is shown as the pink area in Figure 11B. In the following section, to explain reasons for the photon blockade in the region, we give the anharmonic ladder-type energy-level structure in this region (see Figure 12A), where the absorption of the second photon will be blocked, owing to the energy mismatch. This physical mechanism is similar to CPB. On the contrary, in the region, the obvious PB located at the optimal detuning at comes from the destructive interference between different transition paths (see Figure 12B), which is similar to UPB. At EP3, the PB effect will be significantly enhanced through the coinciding cases of CPB- and UPB-based photon blockade.

FIGURE 11

EP3-enhanced strong PB effect in the pseudo-Hermitian conditions. (A) Plot of as functions of normalized detuning and the coupling strength . EP3 is marked by the red circle. In (B), the pink dashed area indicates the obvious PB effect at . We take the parameters as and .

FIGURE 12

Explanation of the PB effect of the non-Hermitian system in the pseudo-Hermitian condition for different regions: (A) in the region and (B) in the region.

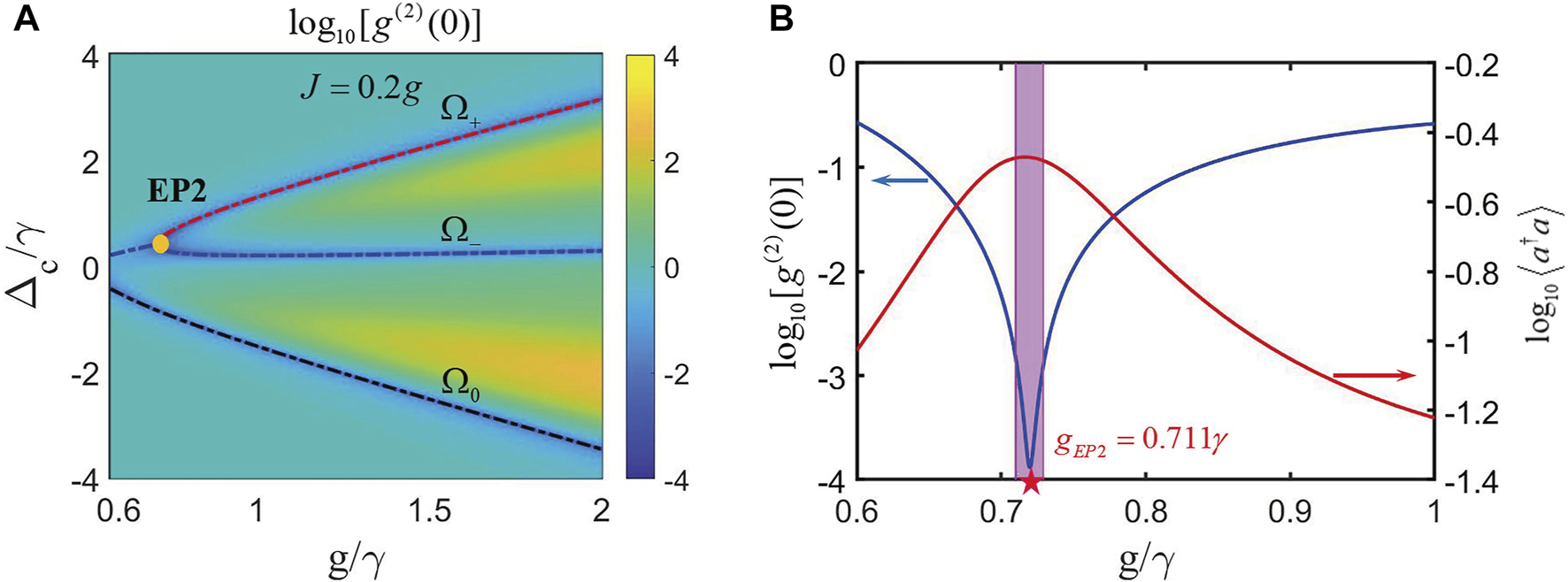

6 Comparison with the enhanced PB effect at EP2 and EP3 in the pseudo-Hermitian condition

In practice, the QE-cavity coupling strengths are position-dependent. Hence, the two coupling strengths are usually different for more general cases. For these cases, the transformation between EP3 and EP2 is achieved by changing the coupling strength. As an example, we take , which meet the condition of . In Figure 13A, we numerically plot the real parts of eigenvalues of the Hamiltonian (11) as a function of the coupling strength . It is not difficult to find that there is a typical EP2 at . As expected, the minimum areas in the spectrum (see the blue pattern) are very well in agreement with the real eigenvalues of the effective non-Hermitian Hamiltonian in Eq. 11, as shown by the dashed lines. One of the eigenvalues is always real for arbitrary (as the black lines show), and the other two eigenvalues are a pair of complex conjugates (as the blue and red lines show) when .

FIGURE 13

In the pseudo-Hermitian conditions when , EP3 is transformed into EP2. (A) The minimum value of (see the blue areas) is in good agreement with the real parts of solutions in Eq. 17, where the black dashed line denotes and the red and blue dashed lines denote . (B) Around EP2, the minimum value of and the large mean photon number are achieved simultaneously, indicating the strong PB effect. We take the parameter as and the others are same as those in Figure 11.

Clearly, by comparing the results of Figure 11B and Figure 13B, it is obvious that this new scheme with different coupling strengths exhibits a very strong PB effect at EP2, having approximately two orders of magnitude reduction of . However, the mean photon number is almost invariant, which implies that it is independent of the transformation of EPn.

Moreover, considering the two-level QE interaction with the dipole–dipole interaction, we can still find EP2 at by taking via using the same method explained in Section 4 (Appendix A). By numerically solving Eq. 17, we can obtain the position of EP2, as shown in Figure 14A. Similarly, we can clearly see the obvious PB effect at in Figure 14B. By comparing the results in Figures 11B, 14B, the system with DDI shows stronger PB effects at EP2 than the system without DDI.

FIGURE 14

In the pseudo-Hermitian conditions when and , there is also an EP2 in the system. (A) Plots of versus the normalized detuning and the coupling strength . In (B), the strong PB effect is shown at . We choose detuning as and other parameters are same as those in Figure 11.

According to aforementioned analysis, we find that the PB effect at EP2 is more obvious than that at EP3 in the condition of the balanced gain–loss rate. When the coupling strength is different, i.e., , the photon loss in the paths and is asymmetric, which strengthens the quantum interference of the transition paths. In addition, when we consider the influence of DDI between the two emitters, photon loss will emerge in three or more paths. Therefore, the destructive interference between different paths of two-photon excitation will be enhanced, resulting in the more apparent photon blockade effect.

7 Conclusion

In short, we have studied the photon blockade effects in a cavity QED system, where the single-mode cavity is gain and the emitters are loss. Through the analytical solution and numerical results, we, respectively, obtain the equal-time second-order correlation functions to describe the intensity of photon blockade for different cases. We find an interesting phenomenon that there is an EP2 in the system in specific conditions. At this point, the perfect photon antibunching can be observed. Moreover, we find that the physical mechanism of the photon blockade is completely different in PT-symmetric and PT-symmetric-broken regions. For the PT-symmetric region, the anharmonicity of the eigenenergy spectrum occurs, which is similar to CPB. However, in the PT-symmetric-broken region, the interference paths with the photon gain and loss result in UPB. At EP2, the UPB phenomenon is most obvious.

Then, we derive the pseudo-Hermiticity conditions for predicting EP3. The PB effect is also improved at EP3, and we can also explain the photon blockade in different regions. Compared with EP3- and EP2-enhanced PB in different pseudo-Hermiticity conditions, we find that the EP2-enhanced PB may exhibit smaller second-order correlation function. Our work provides a new theoretical foundation for the realization of strong PB effects without strong enough non-linearity of the system under the existing experimental conditions. Our research mainly focused on the theoretical model of photon blockade without experiments. With the development of quantum technologies, we believe that high-quality single-photon sources will be prepared based on EPs in the future.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

XZ and GZ took the lead on the research work by running the simulations, performing most of the analysis, and producing most of the figures. ZL contributed to the code development. ZL wrote substantial parts of the manuscript. All authors contributed equally to the discussions, read the manuscript, and provided critical feedback.

Acknowledgments

ZL acknowledges the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62075004 and 11804018) and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (4212051).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Barrett J Hardy L Kent A . No signaling and quantum key distribution. Phys Rev Lett (2005) 95(1):010503. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.010503

2.

Gisin N Ribordy GG Tittel W Zbinden H . Quantum cryptography. Rev Mod Phys (2002) 74(1):145–95. 10.1103/RevModPhys.74.145

3.

Hu JY Yu B Jing MY Xiao LT Jia ST Qin GQ et al Experimental quantum secure direct communication with single Photons. Light Sci Appl (2016) 5 (9):e16144. 10.1038/lsa.2016.144

4.

Gao WB Fallahi P Togan E Miguel-Sanchez J Imamoglu A . Observation of entanglement between a quantum dot spin and a single photon. Nature (2012) 491(7424):426–30. 10.1038/nature11573

5.

Imamoglu A Schmidt H Woods G Deutsch M . Strongly interacting photons in a nonlinear cavity. Phys Rev Lett (1997) 78:1467–70. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.79.1467

6.

Knill E Laflamme R Milburn GJ . A scheme for efficient quantum computation with linear optics. Nature (2001) 409(6816):46–52. 10.1038/35051009

7.

Kok P Munro WJ Nemoto K Ralph TC Dowling JP Milburn GJ . Linear optical quantum computing with photonic qubits. Rev Mod Phys (2007) 79(1):135–74. 10.1103/RevModPhys.79.135

8.

Scarani V Bechmann-Pasquinucci H Cerf NJ Dusek M Lutkenhaus N Peev M . The security of practical quantum key distribution. Rev Mod Phys (2009) 81(3):1301–50. 10.1103/RevModPhys.81.1301

9.

Birnbaum KM Boca A Miller R Boozer AD Northup TE Kimble HJ . Photon blockade in an optical cavity with one trapped atom. Nature (2005) 436(7047):87–90. 10.1038/nature03804

10.

Hamsen C Tolazzi KN Wilk T Rempe G . Two-photon blockade in an atom-driven cavity qed system. Phys Rev Lett (2017) 118(13):133604. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.133604

11.

Lin JZ Hou K Zhu CJ Yang YP . Manipulation and improvement of multiphoton blockade in a cavity-qed system with two cascade three-level atoms. Phys Rev A (2019) 99(5):053850. 10.1103/PhysRevA.99.053850

12.

Zhu CJ Yang YP Agarwal GS . Collective multiphoton blockade in cavity quantum electrodynamics. Phys Rev A (2017) 95(6):063842. 10.1103/PhysRevA.95.063842

13.

Rabl P . Photon blockade effect in optomechanical systems. Phys Rev Lett (2011) 107(6):063601. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.063601

14.

Liao JQ Nori F . Photon blockade in quadratically coupled optomechanical systems. Phys Rev A (2013) 88(2):023853. 10.1103/PhysRevA.88.023853

15.

Xie H Liao CG Shang X Ye MY Lin XM . Phonon blockade in a quadratically coupled optomechanical system. Phys Rev A (2017) 96(1):013861. 10.1103/PhysRevA.96.013861

16.

Huang R Miranowicz A Liao JQ Nori F Jing H . Nonreciprocal photon blockade. Phys Rev Lett (2018) 121(15):153601. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.153601

17.

Wang K Wu Q Yu Y-F Zhang Z-M . Nonreciprocal photon blockade in a two-mode cavity with a second-order nonlinearity. Phys Rev A (2019) 100(5):053832. 10.1103/PhysRevA.100.053832

18.

Hoffman AJ Srinivasan SJ Schmidt S Spietz L Aumentado J Tureci HE et al Dispersive photon blockade in a superconducting circuit. Phys Rev Lett (2011) 107(5):053602. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.053602

19.

Lang C Bozyigit D Eichler C Steffen L Fink JM Abdumalikov AA Jr. et al Observation of resonant photon blockade at microwave frequencies using correlation function measurements. Phys Rev Lett (2011) 106(24):243601. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.243601

20.

Ma S-l Xie J-k Ren Y-l Li X-k Li F-l . Photon-pair blockade in a josephson-photonics circuit with two nondegenerate microwave resonators. New J Phys (2022) 24(5):053001. 10.1088/1367-2630/ac60df

21.

Tang J Geng WD Xu XL . Quantum interference induced photon blockade in a coupled single quantum dot-cavity system. Scientific Rep (2015) 5:9252. 10.1038/srep09252

22.

Snijder HJ Frey JA Norman J Flayac H Savona V Gossard AC et al Observation of the unconventional photon blockade. Phys Rev Lett (2018) 121(4):043601. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.043601

23.

Liang X Duan Z Guo Q Guan S Xie M Liu C . Photon blockade in a bimode nonlinear nanocavity embedded with a quantum dot. Phys Rev A (2020) 102(5):053713. 10.1103/PhysRevA.102.053713

24.

Vaneph C Morvan A Aiello G Fechant M Aprili M Gabelli J et al Observation of the unconventional photon blockade in the microwave domain. Phys Rev Lett (2018) 121(4):043602. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.043602

25.

Gerace D Savona V . Unconventional photon blockade in doubly resonant microcavities with second-order nonlinearity. Phys Rev A (2014) 89(3):031803. 10.1103/PhysRevA.89.031803

26.

Zhou YH Shen HZ Yi XX . Unconventional photon blockade with second-order nonlinearity. Phys Rev A (2015) 92(2):023838. 10.1103/PhysRevA.92.023838

27.

Flayac H Gerace D Savona V . An all-silicon single-photon source by unconventional photon blockade. Scientific Rep (2015) 5:11223. 10.1038/srep11223

28.

Qu Y Li J Wu Y . Interference-modulated photon statistics in whispering-gallery-mode microresonator optomechanics. Phys Rev A (2019) 99(4):043823. 10.1103/PhysRevA.99.043823

29.

Qu Y Shen S Li J Wu Y . Improving photon antibunching with two dipole-coupled atoms in whispering-gallery-mode microresonators. Phys Rev A (2020) 101(2):023810. 10.1103/PhysRevA.101.023810

30.

Li B Huang R Xu X Miranowicz A Jing H . Nonreciprocal unconventional photon blockade in a spinning optomechanical system. Photon Res (2019) 7(6):630–41. 10.1364/prj.7.000630

31.

Carusotto I Ciuti C . Quantum fluids of light. Rev Mod Phys (2013) 85(1):299–366. 10.1103/RevModPhys.85.299

32.

El-Ganainy R Makris KG Khajavikhan M Musslimani ZH Rotter S Christodoulides DN . Non-hermitian physics and Pt symmetry. Nat Phys (2018) 14(1):11–9. 10.1038/nphys4323

33.

Ozdemir SK Rotter S Nori F Yang L . Parity-time symmetry and exceptional points in photonics. Nat Mater (2019) 18(8):783–98. 10.1038/s41563-019-0304-9

34.

Lin Z Pick A Loncar M Rodriguez AW . Enhanced spontaneous emission at third-order Dirac exceptional points in inverse-designed photonic crystals. Phys Rev Lett (2016) 117(10):107402. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.107402

35.

Ashida Y Gong ZP Ueda M . Non-hermitian physics. Adv Phys (2020) 69(3):249–435. 10.1080/00018732.2021.1876991

36.

Feng L Wong ZJ Ma RM Wang Y Zhang X , 346. New York, NY (2014). p. 972–5. 10.1126/science.1258479Single-mode laser by parity-time symmetry breakingScience6212

37.

Hodaei H Miri MA Heinrich M Christodoulides DN Khajavikhan M . Parity-time-symmetric microring lasers. Science (New York, NY) (2014) 346(6212):975–8. 10.1126/science.1258480

38.

Peng B Ozdemir SK Lei FC Monifi F Gianfreda M Long GL et al Parity-time-symmetric whispering-gallery microcavities. Nat Phys (2014) 10(5):394–8. 10.1038/nphys2927

39.

Lin Z Ramezani H Eichelkraut T Kottos T Cao H Christodoulides DN . Unidirectional invisibility induced by Pt-symmetric periodic structures. Phys Rev Lett (2011) 106(21):213901. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.213901

40.

Chang L Jiang X Hua S Yang C Wen J Jiang L et al Parity-time symmetry and variable optical isolation in active-passive-coupled microresonators. Nat Photon (2014) 8(7):524–9. 10.1038/nphoton.2014.133

41.

Hodaei H Hassan AU Wittek S Garcia-Gracia H El-Ganainy R Christodoulides DN et al Enhanced sensitivity at higher-order exceptional points. Nature (2017) 548(7666):187–91. 10.1038/nature23280

42.

Lai Y-H Lu Y-K Suh M-G Yuan Z Vahala K . Observation of the exceptional-point-enhanced sagnac effect. Nature (2019) 576(7785):65–9. 10.1038/s41586-019-1777-z

43.

Hokmabadi MP Schumer A Christodoulides DN Khajavikhan M . Non-hermitian ring laser gyroscopes with enhanced sagnac sensitivity. Nature (2019) 576(7785):70–4. 10.1038/s41586-019-1780-4

44.

Chen WJ Ozdemir SK Zhao GM Wiersig J Yang L . Exceptional points enhance sensing in an optical microcavity. Nature (2017) 548(7666):192–6. 10.1038/nature23281

45.

Zhong Q Ren J Khajavikhan M Christodoulides DN Ozdemir SK El-Ganainy R . Sensing with exceptional surfaces in order to combine sensitivity with robustness. Phys Rev Lett (2019) 122(15):153902. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.153902

46.

Xu H Mason D Jiang LY Harris JGE . Topological energy transfer in an optomechanical system with exceptional points. Nature (2016) 537(7618):80–3. 10.1038/nature18604

47.

Wang X Guo G Berakdar J . Enhanced sensitivity at magnetic high-order exceptional points and topological energy transfer in magnonic planar waveguides. Phys Rev Appl (2021) 15(3):034050. 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.15.034050

48.

Zhang HL Huang R Zhang SD Li Y Qiu CW Nori F et al Breaking anti-Pt symmetry by spinning a resonator. Nano Lett (2020) 20(10):7594–9. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c03119

49.

Downing CA Zueco D Martin-Moreno L . Chiral current circulation and Pt symmetry in a trimer of oscillators. Acs Photon (2020) 7(12):3401–14. 10.1021/acsphotonics.0c01208

50.

Bao LY Qi B Dong DY Nori F . Fundamental limits for reciprocal and nonreciprocal non-hermitian quantum sensing. Phys Rev A (2021) 103(4):042418. 10.1103/PhysRevA.103.042418

51.

Yuan HY Yan P Zheng S He QY Xia K Yung M-H . Steady Bell state generation via magnon-photon coupling. Phys Rev Lett (2020) 124(5):053602. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.053602

52.

Mostafazadeh A . Pseudo-Hermiticity versus PT Symmetry: The necessary condition for the reality of the spectrum of a non-hermitian Hamiltonian. J Math Phys (2002) 43(1):205–214. 10.1063/1.1418246

53.

Mostafazadeh A . Pseudo-Hermiticity versus PT-Symmetry. II. A complete characterization of non-hermitian Hamiltonians with a real spectrum. J Math Phys (2002) 43(5):2814–2816. 10.1063/1.1461427

54.

Mostafazadeh A . Pseudo-hermiticity versus Pt-symmetry iii: Equivalence of pseudo-hermiticity and the presence of antilinear symmetries. J Math Phys (2002) 43(8):3944–51. 10.1063/1.1489072

55.

Zhang G-Q You JQ . Higher-order exceptional point in a cavity magnonics system. Phys Rev B (2019) 99(5):054404. 10.1103/PhysRevB.99.054404

56.

Zhu G . Pseudo-hermitian Hamiltonian formalism of electromagnetic wave propagation in a dielectric medium-application to the nonorthogonal coupled-mode theory. J Lightwave Tech (2011) 29(6):905–11. 10.1109/jlt.2011.2113391

57.

Zhang XZ Song Z . Non-hermitian anisotropic xy model with intrinsic rotation-time-reversal symmetry. Phys Rev A (2013) 87(1):012114. 10.1103/PhysRevA.87.012114

58.

Simeonov LS Vitanov NV . Dynamical invariants for pseudo-hermitian Hamiltonians. Phys Rev A (2016) 93(1):012123. 10.1103/PhysRevA.93.012123

59.

Zhu CJ Hou K Yang YP Deng L . Hybrid level anharmonicity and interference-induced photon blockade in a two-qubit cavity qed system with dipole–dipole interaction. Photon Res (2021) 9(7):1264. 10.1364/prj.421234

60.

Flayac H Savona V . Unconventional photon blockade. Phys Rev A (2017) 96(5):053810. 10.1103/PhysRevA.96.053810

61.

Kopp J . Efficient numerical diagonalization of hermitian 3 × 3 matrices. Int J Mod Phys C (2008) 19(3):523–48. 10.1142/s0129183108012303

Appendix A

When two QEs are close enough, the dipole–dipole interaction (DDI) between two QEs will not be neglected. Hence, the Hamiltonian in Eq. 1 will add the DDI term, i.e., , where J is the strength of DDI. Using the same method in Section 4, we obtain the pseudo-Hermitian conditions of the system as

Here, we take for simplicity. In this case, the coefficients in Eq. 17 become

Specifically, we choose , which satisfy the condition of . In Figure 15, we plot the real and imaginary parts of the solutions of Eq. 17. It is not difficult to find if one of the roots () is real and the others () are a pair of complex conjugates. This result shows that there is a typical EP2 at .

FIGURE 15

Real (see panel (A)) and imaginary parts (see panel (B)) of the eigenvalues (see the black lines) and (see the red and blue lines) versus the coupling strength in the conditions of Eq. (A2). The parameters are chosen as .

Summary

Keywords

exceptional points, PT-symmetric, pseudo-Hermitian condition, cavity–atom QED system, photon blockade

Citation

Li Z, Li X, Zhang G and Zhong X (2023) Realizing strong photon blockade at exceptional points in the weak coupling regime. Front. Phys. 11:1168372. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2023.1168372

Received

17 February 2023

Accepted

03 April 2023

Published

20 April 2023

Volume

11 - 2023

Edited by

Hong Xie, Fujian Jiangxia University, China

Reviewed by

Hailang Dai, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China

Ma Hongyang, Qingdao University of Technology, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Li, Li, Zhang and Zhong.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guofeng Zhang, 08226@buaa.edu.cn; Xiaolan Zhong, zhongxl@buaa.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.