Abstract

The socialist millionaire problem aims to compare the equality of two inputs from two users while keeping their inputs undisclosed to anyone. Quantum private comparison (QPC), whose security relies on the principles of quantum mechanics, can solve this problem and achieve the information-theoretic security of information processing. The current QPC protocols mainly utilize the bitwise XOR operation to implement the comparison, leading to insufficient security. In this paper, we propose a rotation operation-based QPC protocol to solve the socialist millionaire problem, which utilizes Bell states as quantum resources and rotation operations for classical calculations. The proposed protocol only utilizes easy-to-implement technologies such as Bell states, rotation operations, and Bell-basis measurements, making it more practical. The analysis demonstrates that our protocol can meet both the correctness and security requirements. Compared with the existing QPC protocols, our protocol has improved performance in terms of practicability and security.

1 Introduction

With the rapid development of quantum computing, there is a growing concern about the security and privacy of information transmission. Securing traditional encryption methods is no longer reliable due to the emergence of quantum algorithms (Shor’s algorithm [1] and Grover’s algorithm [2]). In order to enhance the security of information transmission, quantum cryptography, whose security is based on the principles of quantum mechanics, has become a focus and attracted much attention. The basic principles of quantum mechanics, such as quantum entanglement, non-cloning, the uncertainty principle, and the superposition principle, enable quantum communication to achieve information-theoretic security. In this context, quantum cryptography protocols, including quantum key distribution (QKD) [3, 4], quantum key agreement (QKA) [5–7], quantum secure direct communication (QSDC) [8, 9], and quantum secret sharing (QSS) [10, 11], have been proposed to address various cryptographic tasks.

The millionaire problem, a primitive of secure multi-party computing (SMC), was proposed by [12] in 1982. In this scenario, two millionaires aim to determine who is wealthier without disclosing their individual wealth. On the basis of Yao’s research, the socialist millionaire problem, a variant of the millionaire problem, was proposed by [13], in which two millionaires sought to compare whether their wealth was equal. However, [14] pointed out that calculating an equality function involving only two parties in the two-party computation setting is not secure. A semi-honest third party is inevitably introduced to complete the design of a secure private comparison protocol.

Quantum private comparison (QPC) utilizes the principles of quantum mechanics to ensure the security of private information. The goal of this project is to solve the socialist millionaire problem, which aims to determine whether the private inputs of the participants are equal while keeping their inputs undisclosed. The first QPC protocol was proposed by [15], in which two users compare their secrets using EPR pairs as quantum information carriers. Decoy photons and a one-way hash function are employed to ensure the security of the protocol. [16] introduced a QPC protocol based on triplet-entangled states in which the comparison result can be obtained even if not all data are compared completely. This is because the private inputs are divided into multiple groups, which leads to an improvement in efficiency. However, [17] pointed out that [16] is susceptible to intercept resend attacks, and some suggestions are provided to enhance the security of private information. After that, some researchers focus on using different quantum states, such as single photons [18, 19], Bell states [20], multi-qubit states [21–24], and high-dimensional quantum states [25–28], and various encoding methods to develop the QPC protocol. Additionally, semi-quantum private comparison (SQPC) protocols [29–36] have been proposed to alleviate the burden on quantum resources. These protocols allow participants with limited quantum abilities to compare their secrets.

[37] proposed a QPC protocol without a classical part that utilizes quantum gates for classical calculations, resulting in improved quantum security. [38] proposed a QPC protocol without requiring a third party. [39] utilized the property of entanglement swapping of Bell states to design a QPC protocol in which each round can compare three-bit classical information. In 2022, an eight-qubit entangled state was used for designing private comparison, which utilizes decoy photons and QKD technology to ensure security [40]. [41] designed a QPC protocol to compare whether single-qubit states are equal with rotation encryption and swap test. [42] employed 4D GHZ-like states as quantum resources to design the QPC protocol.

According to the analysis of previous QPC protocols, it is evident that the bitwise XOR operation is primarily used for comparisons in the design of QPC protocols. This process will result in classical results that exist in intermediate computations and are susceptible to attacks by classical attackers. In this paper, we propose a QPC protocol to solve the socialist millionaire problem using Bell states. This approach utilizes rotation operations to replace the bitwise XOR operation. No classical results are produced, resulting in enhanced security. In addition, it is straightforward to implement with current technology. In our protocol, the private inputs are encoded as the angles of the rotation operation. They can be compared with the assistance of a semi-honest third party who may exhibit unfaithful behavior but will perform the protocol process faithfully. TP is responsible for preparing the initial Bell states at the beginning of the protocol and conducting the Bell-basis measurement to obtain the classical result at the end. The participants only need to encode their inputs as angles and perform the rotation operation on the received quantum states. Compared to the previous protocols, our protocol has the following advantages: we use rotation operations instead of the bitwise XOR operation for classical calculations, which results in improved security. Complex quantum technologies, such as high-dimensional quantum states, entanglement swapping, and joint measurements, are not necessary. Our protocol only utilizes easy-to-implement technologies such as Bell states, rotation operations, and Bell-basis measurements, making it more practical. In other words, our protocol demonstrates superior performance in terms of practicability and security.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the core method of rotation operation. The details of the proposed rotation operation-based quantum solution for the socialist millionaire problem are provided in Section 3. Two simulation experiments and the analysis of the proposed protocol are presented in Sections 4, 5, respectively. Finally, the conclusion is provided in Section 6.

2 Rotation operation

The rotation operation can be represented by the following matrix:

Eq. 1 can be considered a unitary matrix rotated around the y-axis with an angle on the Bloch sphere. When performing the rotation operation on the quantum state , we have

In order to obtain , we can only perform the rotation operation on . Thus, we have

Four types of Bell states can be represented as follows:

When performing rotation operations on Bell states, we observe the following special features:

Lemma 1 holds for .Proof. Without the loss of generality, let us consider as an example. We haveIn the same way, we can prove thatThus,Lemma 1 holds.

Lemma 2 holds for .Proof: Without the loss of generality, let us consider as an example. We haveSince the global phase has no observable effect, we can easily infer thatIn the same way, we can prove thatThus,Lemma 2 holds.

Lemma 3 holds.Proof: Without the loss of generality, let us consider as an example. We haveSince the global phase has no observable effect, we can easily infer thatIn the same way, we can prove thatThus,Lemma 3 holds.

3 Quantum solution for the socialist millionaire problem

In the description of the socialist millionaire problem, there are two users, Alice and Bob, each having their own secrets X and Y, respectively. They sought to compare whether X = Y while keeping X and Y undisclosed to each other, and they learn nothing if .

The binary representations of X and Y are and , respectively, where , , and . Since the proposed protocol is designed for the two-party computation setting, a semi-honest third party named Charlie is involved in performing the comparison. Before the protocol begins, Alice and Bob share a secret key via a QKD protocol. The details of the proposed rotation operation-based quantum solution for the socialist millionaire problem are depicted as follows:

Step 1: Charlie prepares a 2n-length quantum sequence , where G is randomly chosen from four kinds of Bell states. He records their states and takes the first and second particles of all Bell states to generate two ordered n-length quantum sequences and , respectively.

Step 2: Charlie generates 2m decoy photons randomly chosen from . Next, he inserts the same number of decoy photons into and at random positions to generate two new (m + n)-length quantum sequences and , respectively. Then, he records the positions and states of each decoy photon. Finally, he sends to Alice (Bob).

Step 3: When receiving , Alice (Bob) sends a message to Charlie, who will then announce the positions and measurement basis to Alice (Bob). If the decoy photon is in , the measurement basis is Z-basis; otherwise, the measurement basis is X-basis. If an eavesdropper exists, the measurement outcome will not be consistent with the initially prepared decoy photons, and Charlie and Alice (Bob) will abort the protocol. Otherwise, Alice (Bob) discards the decoy photons to get and and performs the following steps:

Step 4: Alice performs rotation operations and on to get . For Bob, he performs rotation operations and on to get .

Step 5: Alice (Bob) follows the same procedures, which involve inserting decoy photons to generate , sending them to Charlie, and checking the presence of an eavesdropper, similar to what Charlie and they did. If they detect the presence of an eavesdropper, they abort the protocol. Otherwise, Charlie discards the decoy photons to get and proceeds with the following steps:

Step 6: Charlie performs Bell-basis measurements on and to obtain the measurement results. If all measurement results match the initially prepared Bell states, then X = Y. Otherwise, . Charlie announces the final comparison result to Alice and Bob.

4 Simulation experiments

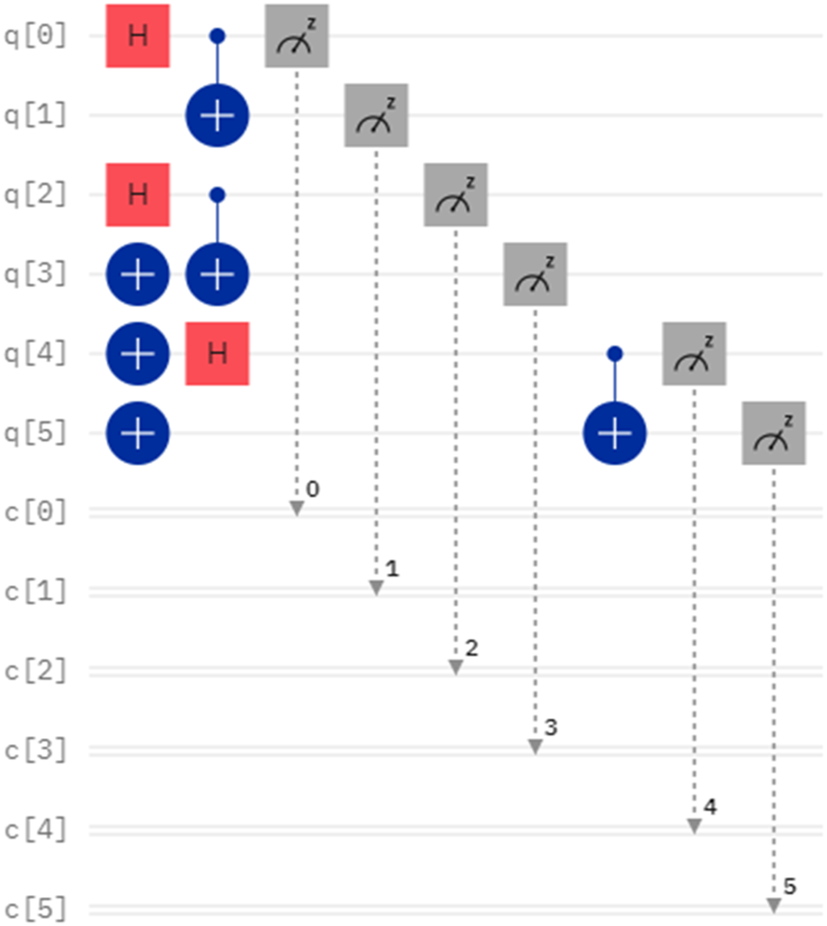

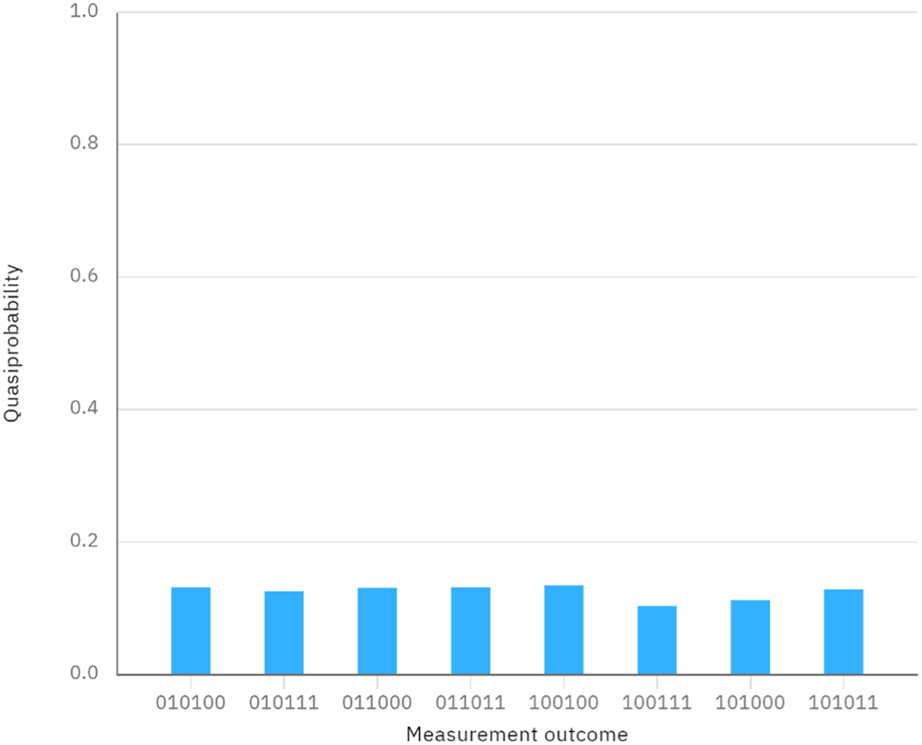

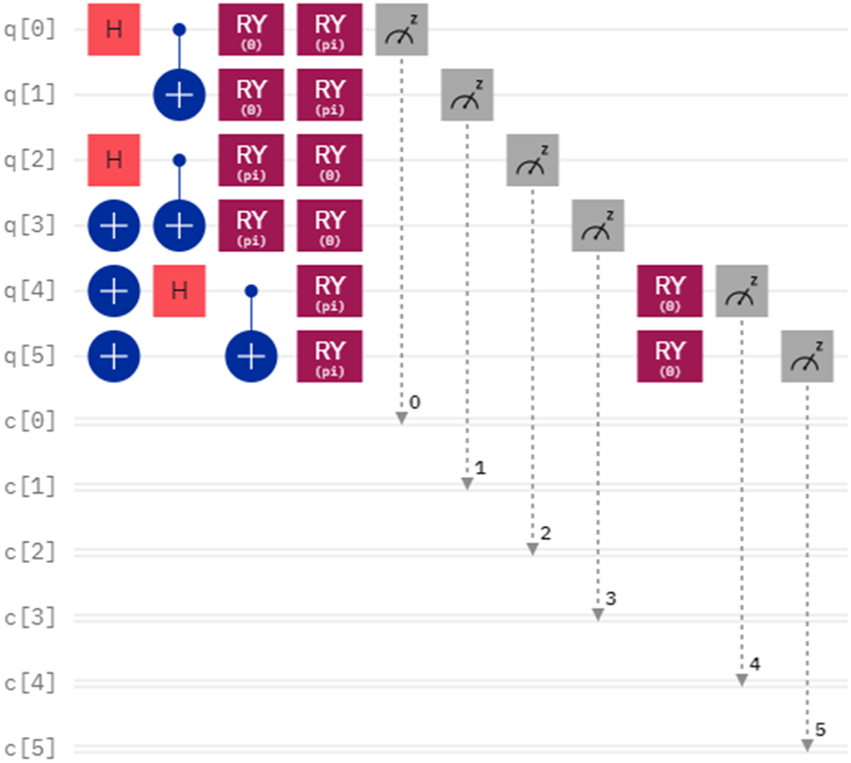

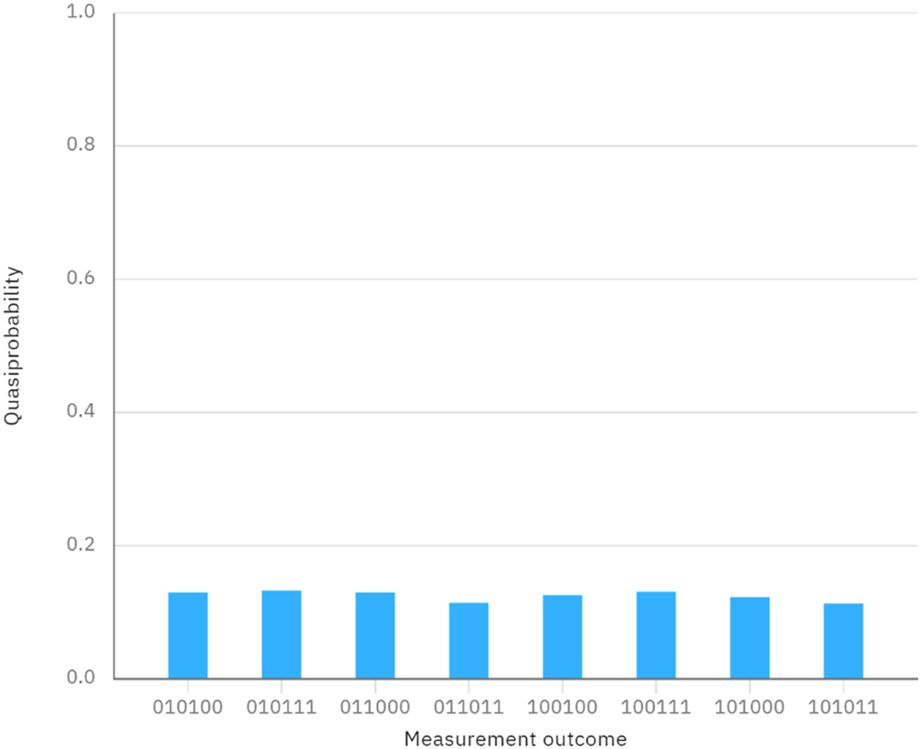

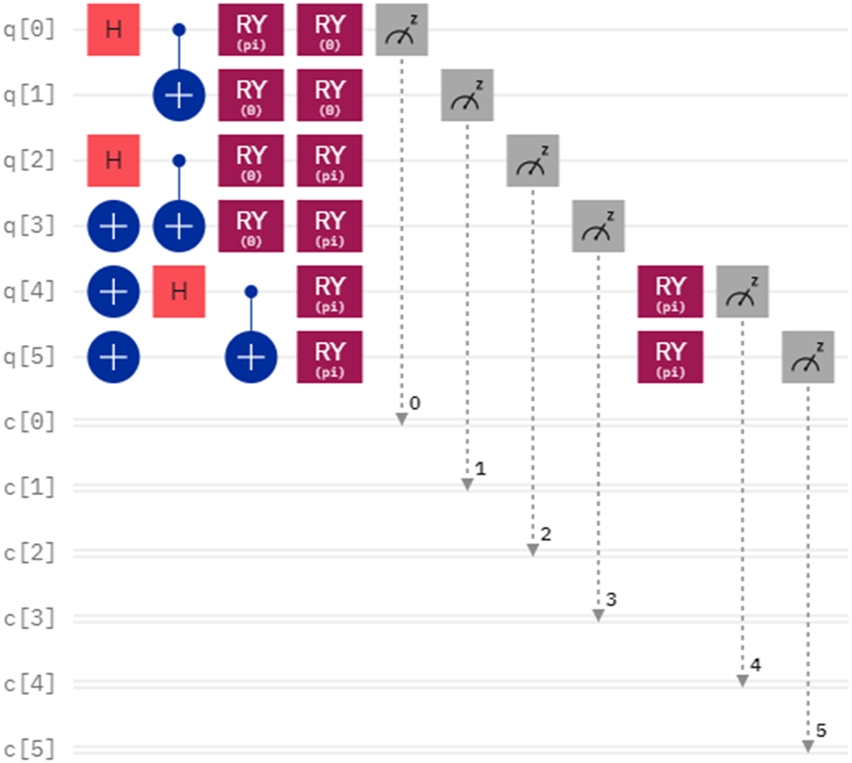

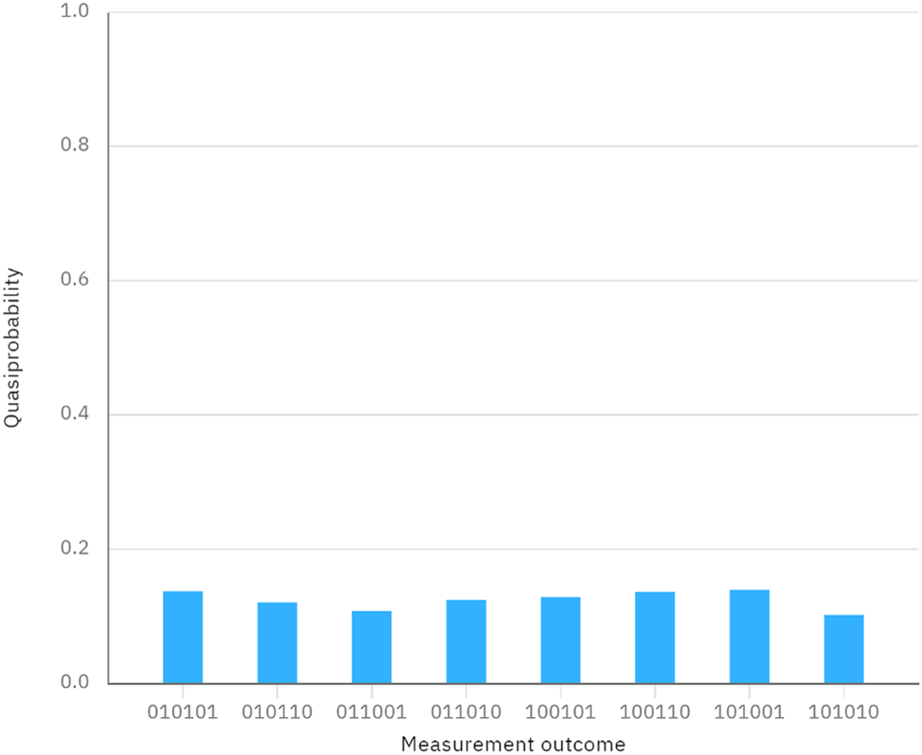

Considering a case, the secrets of Alice and Bob are denoted as X = 6 and Y = 6, which can be represented in binary form as and . Since the lengths of X and Y are 3, the number of Bell states is 3. We assume that the initially prepared Bell states are denoted as , and the quantum circuit and measurement outcome without considering the eavesdropping detection can be seen in Figures 1, 2. Since the quantum circuit is designed and executed on IBM Quantum Composer, which is accessible for circuits utilizing fewer than 7 qubits, and the chosen measurement basis is the Z basis, the measurement outcomes are represented in the form of 0 and 1. Suppose that the secret key shared between Alice and Bob via a QKD protocol is . When Alice performs the rotation operations and on the first particles of and Bob performs the rotation operations on the second particles of , the corresponding quantum circuit and the final measurement outcome can be seen in Figures 3, 4, respectively. It must be noted that no Bell-basis measurement exists on the IBM Quantum Composer, and we use single-particle measurement instead of Bell-basis measurement to get the same effect. From Figure 4, we can easily observe that the measurement outcome when performing the quantum circuit in Figure 3 is the same as the measurement outcome of the initially prepared Bell states in Figure 1. This indicates that all the measurement results match the initially prepared Bell states, suggesting that the comparison result is X = Y. In a precise sense, we can conclude that X = Y due to the identical rotation operations performed by Alice and Bob. The simulation experiment further verifies the correctness and feasibility of the protocol.

FIGURE 1

Quantum circuit of the initially prepared Bell states.

FIGURE 2

Measurement outcomes of the initially prepared Bell states.

FIGURE 3

Quantum circuit for comparing X and Y.

FIGURE 4

Measurement outcomes when performing the quantum circuit in Figure 3.

Considering another case, the secrets of Alice and Bob are denoted as and , which can be represented in binary form as and . Since the lengths of X and Y are 3, the number of Bell states is 3. Suppose that the secret key shared between Alice and Bob via a QKD protocol is . We also assume that the initially prepared Bell states are denoted as , which are the same as those in the first case. When Alice performs the rotation operations and on the first particles of and Bob performs the rotation operations and on the second particles of , the corresponding quantum circuit and the final measurement outcome can be seen in Figures 5, 6, respectively. From Figure 6, however, we can observe that the measurement outcome when performing the quantum circuit shown in Figure 5 is different from the measurement outcome of the initially prepared Bell states in Figure 1. This discrepancy indicates that the measurement results do not match the initially prepared Bell states, suggesting that the comparison result is . Since the rotation operations performed by Alice and Bob are different, we can draw the direct conclusion that . From another perspective, we can directly see that .

FIGURE 5

Quantum circuit for comparing and .

FIGURE 6

Measurement outcomes when performing the quantum circuit in Figure 5.

In conclusion, these two simulations reveal the correctness and feasibility of our protocol.

5 Analysis

5.1 Correctness

Without the loss of generality, we take as the initially prepared Bell state. When performing rotation operations , ) and (, ) on the first and second particles of , respectively, we have

Without the loss of generality, we set , and four situations should be considered.

Case IWhen and , we haveWhen performing Bell-basis measurement on , the measurement outcome is , indicating that .

Case IIWhen and , we haveWhen performing Bell-basis measurement on , the measurement outcome is , indicating that .

Case IIIWhen and , we haveWhen performing Bell-basis measurement on , the measurement outcome is , indicating that .

Case IVWhen and , we haveWhen performing Bell-basis measurement on , the measurement outcome is , indicating that .The same method can be used to verify the 2n-length quantum sequence S, which could help confirm the protocol’s correctness.

5.2 Security analysis

In this section, we will demonstrate that the proposed protocol is resistant to both external and insider attacks. More specifically, any eavesdroppers attempting to steal the private inputs will be inevitably detected. One participant cannot access the private input of another participant, even if they process the immediate result. TP, who knows the comparison result, cannot learn the private inputs.

5.2.1 External attacks

Suppose that an outsider eavesdropper, Eve, with quantum capabilities, attempts to steal the private inputs. Various quantum attacks, including intercept–measure–resend attacks, man-in-the-middle attacks, and correlation–elicitation attacks, are frequently mentioned as methods to steal information. However, if the decoy-state method is used to detect the eavesdropper, any eavesdropping in the quantum channel will be detected, and the quantum communication protocol will be aborted. The decoy-state method can be considered an effective approach to detecting the presence of an eavesdropper, as validated in [43]. Since the quantum sequence transmitted in the quantum channel includes both target states and non-orthogonal states (decoy photons) that cannot be distinguished by Eve, Eve has to consider both of them as the target states and perform the same operation on them. This will inevitably lead to the modification of the photon sequence, making her actions detectable. Without the loss of generality, Eve performs the same operation to entangle the sample photons and the prepared auxiliary quantum system , and this process can be expressed as

where are four pure states determined by the unitary operations , and they satisfy

Moreover, must satisfy the following conditions: and . To avoid being detected by the participants when they perform the eavesdropping detection, Eqs 2–5 must satisfy the following conditions:

where is a column-zero vector. We can further infer that . Substituting and the results of Eq. 6 into Eqs 2–5, we can obtain

It can be easily seen that regardless of the sample photons, the auxiliary quantum system will always be in state . In other words, the non-orthogonal states (decoy photons) can be distinguished by Eve. Performing any operation will inevitably introduce errors. Therefore, Eve’s malicious behavior will be detected, and she will never succeed.

In addition, the rotation operations performed on the initially prepared Bell states result in the transmitted quantum states containing four different types (). Without knowing the rotation angles, no one can determine the initial Bell states by measuring the received quantum states. Therefore, rotation operations also ensure the security of information transmission in the quantum channel.

5.2.2 Insider attacks

The insider participants (Charlie, Alice, and Bob) may launch attacks to steal private inputs. Two cases of participants’ attacks are analyzed as follows:

Case 1Attack from TPIn our protocol, the semi-honest TP will execute the protocol process faithfully, but she cannot conspire with any participants. She may steal some useful information through the protocol loophole. Throughout the entire process, TP is involved in preparing the initial Bell states at the beginning of the protocol and conducting the Bell-basis measurement to obtain the classical result at the end. Although she knows the final comparison result, she still cannot infer the private inputs. For example, when Alice and Bob perform rotation operations and on their received quantum sequences, the final measurement result obtained by TP is the same as when Alice and Bob perform rotation operations and on their received quantum sequences. Similarly, when Alice and Bob perform rotation operations and on their received quantum sequences, the final measurement result obtained by TP is the same as when Alice and Bob perform rotation operations and on their received quantum sequences. As a result, TP cannot distinguish rotation operations performed by Alice and Bob. Additionally, TP may launch attacks similar to Eve, but this behavior will be detected, as discussed in Section 5.2.1. Therefore, TP’s attack does not work.

Case 2Attack from Alice or BobThe roles of Alice and Bob are identical. Without the loss of generality, assume that dishonest Alice tries to obtain Bob’s private information. Bob’s private inputs are encoded into the rotation operation , which is then performed on the received sequence . However, since there is no communication between Alice and Bob, intercepting the sequences and transmitted between Alice and TP is the only way for Alice to learn Bob’s operation. This attack does not work because the decoy-state method is adopted to detect eavesdropping, as discussed in Section 5.2.1. Therefore, the private inputs of Alice and Bob will remain undisclosed to each other.

5.3 Efficiency and comparison

In the QPC protocol, qubit efficiency [44] can be used to evaluate the utilization of quantum states, which is defined as

where represents the number of classical bits compared in the whole protocol and represents the total number of qubits consumed, excluding the decoy photons used to detect the eavesdropper. The comparison between our protocol and some other QPC protocols is presented in Table 1, focusing on quantum resources, quantum operations, and qubit efficiency. In our protocol, a Bell state is required for comparing one-bit classical information, resulting in a qubit efficiency of 50%.

TABLE 1

| Reference [15] | Reference [16] | Reference [19] | Reference [39] | Reference [40] | Ours | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum resource | EPR pairs | GHZ state | Single photons | Bell states | Eight-qubit entangled state | Bell states |

| Unitary operation | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Entanglement swapping | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Bitwise XOR operation | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Quantum measurement | Bell-basis | Single-particle | Single-particle | GHZ-basis | Single-particle | Bell-basis |

| Qubit efficiency | 25% | 33% | 25% | 50% | 25% | 50% |

Comparison between our protocol and some other QPC protocols.

From Table 1, we can observe that the qubit efficiency and quantum resource of our protocol compared to [39] are identical, but our approach involves rotation operations and Bell-basis measurements instead of entanglement swapping and GHZ-basis measurements. This modification makes our protocol easier to implement and facilitates comparison. Compared with [40], our protocol demonstrates superior performance in quantum resource utilization, as the preparation of eight-qubit entangled states poses a significant challenge. Additionally, [39, 40] require the bitwise XOR operation for comparison, leading to inadequate security. Although [15] and our protocol mainly utilize unitary operations, our protocol has higher qubit efficiency. Implementing [15, 16, 19] is easy with current technology, but the qubit efficiency is relatively low. It must be noted that our protocol has an advantage in terms of security compared with [16, 39, 40] since the participants (Charlie, Alice, and Bob) do not perform any classical operations, including the bitwise XOR operation, and record the intermediate computations because the classical computation is replaced by the rotation operation. Therefore, a classical attacker has a lower chance of performing successful attacks because no classical result is produced, significantly reducing the probability of stealing private information. This could contribute to the better security of the QPC protocol.

6 Conclusion

To sum up, in this paper, we propose a rotation operation-based QPC protocol to solve the socialist millionaire problem. The protocol utilizes Bell states as quantum resources and rotation operations for classical calculations. The private inputs of the participants are encoded into the rotation operations, and no classical result is produced. This effectively reduces the risk of classical attacks and enhances the security of the QPC protocol. Compared with the current QPC protocols, complex quantum technologies such as high-dimensional quantum states, entangled swapping technology, and joint measurements are not required. Our protocol only utilizes easy-to-implement technologies such as Bell states, rotation operations, and Bell-basis measurements. All of these improvements could not only make our protocol more practical but also enhance its security. In other words, our protocol demonstrates superior performance in terms of practicability and security. In the future, we will focus on designing a semi-quantum private comparison to reduce the demand for quantum resources and develop a more efficient QPC protocol.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MH: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, and writing–original draft. S-YS: writing–review and editing. WZ: funding acquisition, supervision, and writing–review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work is supported by the Open Fund of Network and Data Security Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province (grant no. NDS2024-1) and the Gongga Plan for the “Double World-class Project.”

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

ShorPW. Polynomial-time algorithms for prime factorization and discrete logarithms on a quantum computer. SIAM Rev (1999) 41(2):303–32. 10.1137/S0036144598347011

2.

GroverLK. Quantum mechanics helps in searching for a needle in a haystack. Phys Rev Lett (1997) 79(2):325–8. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.79.325

3.

BennettCHBrassardG. Quantum cryptography: public key distribution and coin tossing. Theor Comput Sci (2014) 560:7–11. 10.1016/j.tcs.2014.05.025

4.

ZhangWvan LeentTRedekerKGarthoffRSchwonnekRFertigFet alA device-independent quantum key distribution system for distant users. Nature (2022) 607(7920):687–91. 10.1038/s41586-022-04891-y

5.

HuangXZhangSBChangYQiuCLiuDMHouM. Quantum key agreement protocol based on quantum search algorithm. Int J Theor Phys (2021) 60:838–47. 10.1007/s10773-020-04703-x

6.

ZhouNRLiaoQZouXF. Multi-party semi-quantum key agreement protocol based on the four-qubit cluster states. Int J Theor Phys (2022) 61(4):114. 10.1007/s10773-022-05102-0

7.

LiHHGongLHZhouNR. New semi-quantum key agreement protocol based on high-dimensional single-particle states. Chin Phys B (2020) 29(11):110304. 10.1088/1674-1056/abaedd

8.

HuangXZhangSChangYYangFHouMChenW. Quantum secure direct communication based on quantum homomorphic encryption. Mod Phys Lett A (2021) 36(37):2150263. 10.1142/S0217732321502631

9.

ShengYBZhouLLongGL. One-step quantum secure direct communication. Sci Bull (2022) 67(4):367–74. 10.1016/j.scib.2021.11.002

10.

HilleryMBužekVBerthiaumeA. Quantum secret sharing. Phys Rev A (1999) 59(3):1829–34. 10.1103/PhysRevA.59.1829

11.

ShenACaoXYWangYFuYGuJLiuWBet alExperimental quantum secret sharing based on phase encoding of coherent states. Mech Astron (2023) 66(6):260311. 10.1007/s11433-023-2105-7

12.

YaoAC. Protocols for secure computations. In: 23rd annual symposium on foundations of computer science (sfcs 1982); November 1982; Chicago, IL, USA (1982). p. 160–4.

13.

BoudotFSchoenmakersBTraoreJ. A fair and efficient solution to the socialist millionaires’ problem. Discrete Appl Math (2001) 111(1-2):23–36. 10.1016/S0166-218X(00)00342-5

14.

LoHK. Insecurity of quantum secure computations. Phys Rev A (1997) 56(2):1154–62. 10.1103/PhysRevA.56.1154

15.

YangYGWenQY. An efficient two-party quantum private comparison protocol with decoy photons and two-photon entanglement. J Phys A: Math Theor (2009) 42(5):055305. 10.1088/1751-8113/42/5/055305

16.

ChenXBXuGNiuXXWenQYYangYX. An efficient protocol for the private comparison of equal information based on the triplet entangled state and single-particle measurement. Opt Commun (2010) 283(7):1561–5. 10.1016/j.optcom.2009.11.085

17.

LinJTsengHYHwangT. Intercept–resend attacks on Chen et al.'s quantum private comparison protocol and the improvements. Opt Commun (2011) 284(9):2412–4. 10.1016/j.optcom.2010.12.070

18.

HouMWuY. Single-photon-based quantum secure protocol for the socialist millionaires’ problem. Front Phys (2024) 12:1364140. 10.3389/fphy.2024.1364140

19.

HuangWWenQYLiuBGaoFSunY. Robust and efficient quantum private comparison of equality with collective detection over collective-noise channels. Sci China Phys Mech Astron (2013) 56:1670–8. 10.1007/s11433-013-5224-0

20.

LiuWWangYBCuiW. Quantum private comparison protocol based on Bell entangled states. Commun Theor Phys (2012) 57(4):583–8. 10.1088/0253-6102/57/4/11

21.

XuQDChenHYGongLHZhouNR. Quantum private comparison protocol based on four-particle GHZ states. Int J Theor Phys (2020) 59:1798–806. 10.1007/s10773-020-04446-9

22.

JiZXZhangHGFanPR. Two-party quantum private comparison protocol with maximally entangled seven-qubit state. Mod Phys Lett A (2019) 34(28):1950229. 10.1142/S0217732319502298

23.

JiZZhangHWangH. Quantum private comparison protocols with a number of multi-particle entangled states. IEEE Access (2019) 7:44613–21. 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2906687

24.

ChangYZhangWBZhangSBWangHCYanLLHanGHet alQuantum private comparison of equality based on five-particle cluster state. Commun Theor Phys (2016) 66(6):621–8. 10.1088/0253-6102/66/6/621

25.

JiaHYWenQYSongTTGaoF. Quantum protocol for millionaire problem. Opt Commun (2011) 284(1):545–9. 10.1016/j.optcom.2010.09.005

26.

YuCHGuoGDLinS. Quantum private comparison with d-level single-particle states. Physica Scripta (2013) 88(6):065013. 10.1088/0031-8949/88/06/065013

27.

GuoFZGaoFQinSJZhangJWenQY. Quantum private comparison protocol based on entanglement swapping of d-level Bell states. Quan Inf Process (2013) 12(8):2793–802. 10.1007/s11128-013-0536-6

28.

WangBGongLHLiuSQ. Multi-party quantum private size comparison protocol with d-dimensional Bell states. Front Phys (2022) 10:981376. 10.3389/fphy.2022.981376

29.

ZhouNRXuQDDuNSGongLH. Semi-quantum private comparison protocol of size relation with d-dimensional Bell states. Quan Inf Process (2021) 20:124–15. 10.1007/s11128-021-03056-6

30.

GongLHLiMLCaoHWangB. Novel semi-quantum private comparison protocol with Bell states. Laser Phys Lett (2024) 21(5):055209. 10.1088/1612-202X/ad3a54

31.

GongLHChenZYQinLGHuangJ. Robust multi-party semi-quantum private comparison protocols with decoherence-free states against collective noises. Adv Quan Tech (2023) 6(8):2300097. 10.1002/qute.202300097

32.

WangBLiuSQGongLH. Semi-quantum private comparison protocol of size relation with d-dimensional GHZ states. Chin Phys B (2022) 31(1):010302. 10.1088/1674-1056/ac1413

33.

LiYCChenZYXuQDGongLH. Two semi-quantum private comparison protocols of size relation based on single particles. Int J Theor Phys (2022) 61(6):157. 10.1007/s10773-022-05149-z

34.

WuWQGuoLNXieMZ. Multi-party semi-quantum private comparison based on the maximally entangled GHZ-type states. Front Phys (2022) 10:1048325. 10.3389/fphy.2022.1048325

35.

JiangLZSemi-quantum private comparison based on Bell states. Quan Inf Process (2020) 19(6):180. 10.1007/s11128-020-02674-w

36.

LinPHHwangTTsaiCW. Efficient semi-quantum private comparison using single photons. Quan Inf Process (2019) 18:207–14. 10.1007/s11128-019-2251-4

37.

LangYFQuantum gate-based quantum private comparison. Int J Theor Phys (2020) 59(3):833–40. 10.1007/s10773-019-04369-0

38.

WuWQZhouGLZhaoYXZhangH. New quantum private comparison protocol without a third party. Int J Theor Phys (2020) 59:1866–75. 10.1007/s10773-020-04454-9

39.

HuangXZhangSBChangYHouMChengW. Efficient quantum private comparison based on entanglement swapping of bell states. Int J Theor Phys (2021) 60:3783–96. 10.1007/s10773-021-04915-9

40.

FanPRahmanAUJiZJiXHaoZZhangH. Two-party quantum private comparison based on eight-qubit entangled state. Mod Phys Lett A (2022) 37(05):2250026. 10.1142/S0217732322500262

41.

HuangXChangYChengWHouMZhangSB. Quantum private comparison of arbitrary single qubit states based on swap test. Chin Phys B (2022) 31(4):040303. 10.1088/1674-1056/ac4103

42.

LiuCZhouSGongLHChenHY. Quantum private comparison protocol based on 4D GHZ-like states. Quan Inf Process (2023) 22(6):255. 10.1007/s11128-023-03999-y

43.

HuangXZhangWZhangS. Practical quantum protocols for blind millionaires’ problem based on rotation encryption and swap test. Physica A: Stat Mech its Appl (2024) 637:129614. 10.1016/j.physa.2024.129614

44.

HuangXZhangWFZhangSB. Efficient multiparty quantum private comparison protocol based on single photons and rotation encryption. Quan Inf Process (2023) 22(7):272. 10.1007/s11128-023-04027-9

Summary

Keywords

socialist millionaire problem, quantum private comparison, bell states, rotation operation, security

Citation

Hou M, Sun S-Y and Zhang W (2024) Quantum private comparison for the socialist millionaire problem. Front. Phys. 12:1408446. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2024.1408446

Received

28 March 2024

Accepted

08 May 2024

Published

19 June 2024

Volume

12 - 2024

Edited by

Nanrun Zhou, Shanghai University of Engineering Sciences, China

Reviewed by

Lihua Gong, Shanghai University of Engineering Sciences, China

Ma Hongyang, Qingdao University of Technology, China

Run-Hua Shi, North China Electric Power University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Hou, Sun and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Zhang, zhangwei@scujj.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.