Abstract

Pseudomodes of non-self-adjoint Schrödinger operators corresponding to large pseudoeigenvalues are constructed. The approach is non-semiclassical and extendable to other types of models including the damped wave equation and Dirac operators.

1 Introduction

The (-)pseudospectrum (with positive ) of an operator in a Hilbert space is the union of the spectrum of and all those complex numbers from the resolvent set of for whichEquivalently, comprises the spectrum of and (pseudoeigenvalues) for which there exists a vector (pseudomode) in the domain of such thatIf is self-adjoint (or, more generally, normal), the -pseudospectrum is trivial in the sense that it is just the -tubular neighbourhood of the spectrum of . In general, however, the pseudoeigenvalues can lie outside the -tubular neighbourhood and their location is important to correctly seize various properties of , see [1–3].

The goal of this brief research report is to explain in a succinct way the approach in Krejčiřík and Siegl [4] to locate pseudoeigenvalues of (non-semiclassical) Schrödinger operatorswhere is at least locally square-integrable and . In such a case, there exists a unique m-accretive extension of Equation 1 initially defined on , see ([5], Thm. VII.2.6). Since our constructed pseudomodes are compactly supported and at least twice weakly differentiable, they belong to the domain of .

The operator is self-adjoint (respectively, normal) if, and only if, is real-valued (respectively, is constant). To ensure non-trivial pseudospectra, we shall therefore adopt the standing hypothesiswhere the limits are allowed to be infinite. The assumption (Equation 2) can be interpreted as a “global” version of the Davies’ condition , see [6] and also [7].

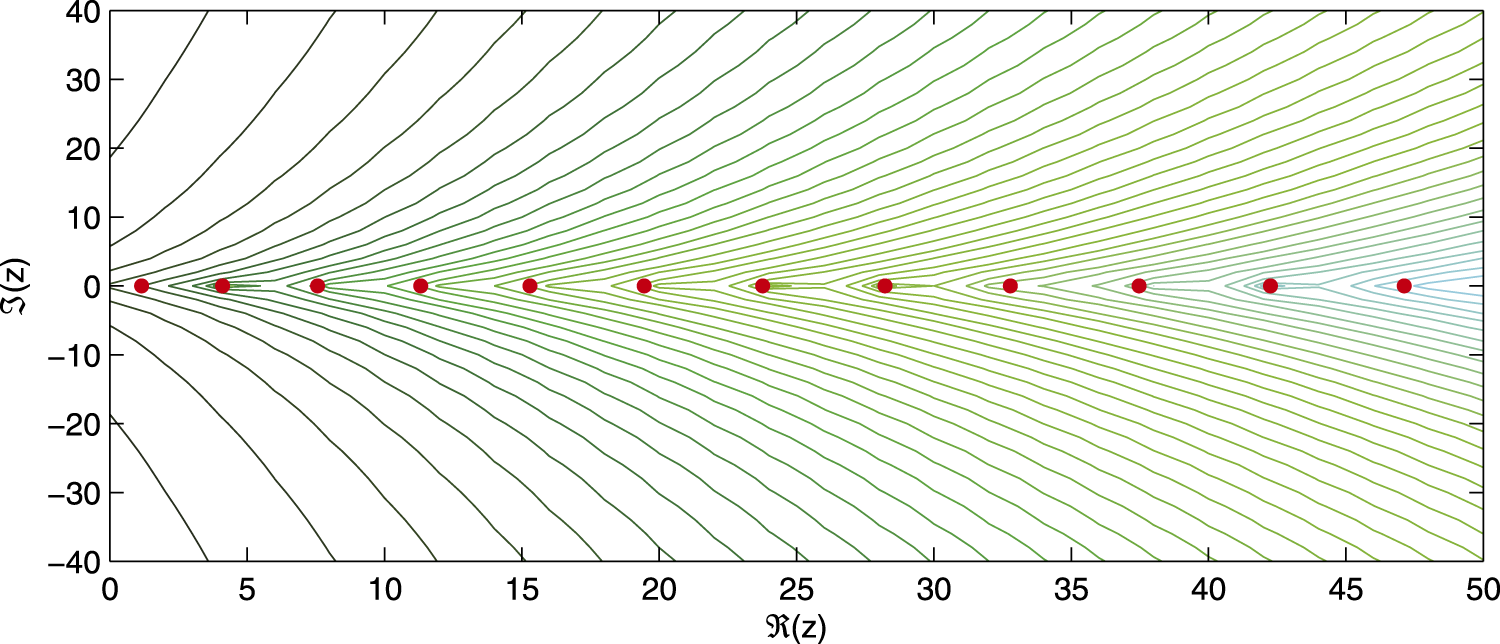

To simplify the presentation, the potential will be assumed to be smooth and imaginary-valued. Typical examples to keep in mind are as follows:or their imaginary shifts. In particular, with is the celebrated imaginary cubic (or Bender’s) oscillator (with purely real and discrete spectrum, see Figure 1), which was made popular in the context of the so-called -symmetric quantum mechanics in [8].

FIGURE 1

Spectrum (red dots) and pseudospectra (enclosed by the green contour lines) of the imaginary cubic oscillator. (Courtesy of Miloš Tater.)

The objective is to develop a systematic construction of pseudomodes ensuring that, for any diminishing , there is a complex number with large magnitude such that . The results are particularly striking whenever this set of pseudoeigenvalues lie outside (in fact, “very far” from) the -tubular neighbourhood of . This is particularly the case of the imaginary cubic oscillator, for which the analysis below show that for an arbitrarily small there exists a pseudoeigenvalue with an arbitrarily large imaginary part, despite the fact that the spectrum is purely real (see Figure 1 for a numerical quantification of the pseudospectrum level lines). This property implies the lack of Riesz basis for the eigenfunctions, challenging in the spirit of [9] the physical relevance of the -realisation of the Bender’s oscillator. The follow-up [4] summarised in this report can be considered as a methodical and more advanced study of not necessarily polynomial potentials.

The feature of the approach of [4] is that it does not rely on semiclassical methods developed in [6, 7, 10]. In fact, we are able to construct large-energy pseudomodes for potentials (like of exponential type, see of Equation 3) which cannot be reduced (by scaling) to a small Planck’s constant included in the kinetic energy. On the contrary, the known claims in the semiclassical setting follow immediately from our approach.

2 Methods

Our strategy of the construction of pseudomodes is based on the Liouville–Green approximation, also known as the JWKB method in mathematical physics. The key idea is that, if were constant, exact solutions of the differential equation associated with would be the two non-integrable functions

The starting point of the approximation scheme is to use the same ansatz for variable as well. More specifically, we choose for it is exponentially decaying under the hypothesis (Equation 2), whenever is small with respect to the limits of at . A direct computation yieldsRecalling the simplifying hypothesis that and assuming in addition that and (typically large), one has the estimatefor every . It follows that large real energies always lie in the pseudospectrum, namely, for every positive ,Of course, this result is interesting only if the supremum norm is bounded. From examples (Equation 3), relevant potentials are thus and with , in which case we can take and obtain thus a pseudomode satisfying the decay as . The latter is particularly interesting because the spectrum of the imaginary Airy operator is empty, see, e.g., ([3, 11], Section VII.A) or more generally [12], where the last reference includes also an elementary proof of the optimal resolvent norm estimate for the Airy operator.

It is not difficult to modify the exponentially decaying pseudomode to a compactly supported pseudomode , while still keeping the same decay as . Indeed, let be a smooth function such that on and outside . Given any positive number , let us define the rescaled cut-off function . Then is compactly supported and one hasUsing that pointwise as , while one gains one by each derivative, it is possible to verify the desired decay by the -dependent choice .

To cover a larger class of potentials, let us consider a modified ansatz , where is a function to be chosen later. A direct computation yieldsNow we choose to annihilate the error term from Equation 4, by solving the first-order linear differential equation , namely, . Thus we arrive at the familiar expressionThenwhere the new error term can be estimated as follows:This result is an improvement upon (Equation 4) with (Equation 5) in two respects. First, if the supremum norm is bounded for , we get a pseudomode with an improved decay as . This is the case of and with from examples (Equation 3). Second, keeping the decay by the choice , we can now cover with from examples (Equation 3).

The above scheme can be continued by employing the general ansatz in square-root powers of :where and with is iteratively chosen in such a way to annihilate the previous error term . By enlarging , more derivatives of are required. On the other hand, a better decay (in negative powers of ) of the new error term is achieved and a larger class of potentials can be covered. For instance, all the examples (Equation 3) are already covered by the choice , namely, as .

3 Results

To make the above procedure rigorous, it is important to ensure that in the expansion (Equation 6) is dominant, in order to guarantee that have appropriate decay properties at . One of the main achievements of [4] is the formulation of the robust sufficient conditionto hold as with some real number for every . Note that , and 0 for the potentials , and of Equation 3, respectively. In fact, it is possible to allow for (corresponding to superexponentially growing potentials). Moreover, different behaviours at may be allowed. However, let us stick to Equation 7 to make the presentation here as simple as possible.

To get a compactly supported pseudomode, it turns out that the adequate -dependent cut-off function should be supported in the interval , where (denoting )Recall that we assume and note that as . In particular, , and as for the potentials , and of Equation 3, respectively.

Under the present simplifying hypotheses (in particular, , and ), the general result of Krejčiřík and Siegl [4] (Thm. 3.7) can be formulated as follows.

Let be smooth satisfying Equations 2, 7 with given . Ifthen there exists such that and

The extra condition (Equation 8) with the choice is clearly satisfied for the potential of Equation 3 (in fact, for any bounded potential satisfying Equations 2, 7). To satisfy Equation 8 for all the polynomial potentials of Equation 3, it is sufficient to take . Finally, Equation 8 is verified for the exponential potential of Equation 3 with .

In Krejčiřík and Siegl [4], the decay rate in Equation 9 is carefully quantified in terms of the left-hand side of Equation 8 and other quantities related to the behaviour of a general potential at infinity.

4 Discussion

4.1 Generality

The JWKB-type scheme sketched in Section 2 is made rigorous in [4] for a fairly general class of potentials , beyond the present simplifying hypotheses. In particular, the potential is allowed to have a real part, however, its largeness must be suitably “small” with respect to its imaginary part. This is quantified by natural modifications of Equations 2, 7. What is more, pseudoeigenvalues along general curves (beyond the present simplifying hypothesis ) diverging in the complex plane are located. In particular, the rotated harmonic (or Davies’) oscillator made popular in the pioneering work [13] or shifted harmonic oscillator studied in [3, 14] are covered. At the same time, potentials decaying at infinity are included. Finally, possibly discontinuous potentials (like ) are comprised by a refined mollification argument.

4.2 Optimality

It turns out that the conditions on potentials identified in [4] as well as the regions in the complex plane where the pseudoeigenvalues are located are optimal. The latter can be checked directly for the rotated harmonic (or Davies’) oscillator with help of the conjecture due to [15] solved by [16], More generally, the optimality of the pseudospectral regions follows by upper resolvent estimates performed in [17, 18].

4.3 Generalisations

The method of [4] is fairly robust and can be generalised to other models. So far, this has been done for the damped wave equation in [19], Dirac operators in [20] and biharmonic operators in [21].

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DK: Writing–review and editing, Writing–original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal Analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. PS: Writing–review and editing, Writing–original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal Analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. DK was supported by the EXPRO grant No. 20-17749X of the Czech Science Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

TrefethenLNEmbreeM. Spectra and pseudospectra. Princeton University Press (2005).

2.

DaviesEB. Linear operators and their spectra. Cambridge University Press (2007).

3.

KrejčiříkDSieglPTaterMViolaJ. Pseudospectra in non-Hermitian quantum mechanics. J Math Phys (2015) 56:103513. 10.1063/1.4934378

4.

KrejčiříkDSieglP. Pseudomodes for Schrödinger operators with complex potentials. J Funct Anal (2019) 276:2856–900. 10.1016/j.jfa.2018.10.004

5.

EdmundsDEEvansWD. Spectral theory and differential operators. Oxford: Oxford University Press (1987).

6.

DaviesEB. Semi-classical states for non-self-adjoint Schrödinger operators. Comm Math Phys (1999) 200:35–41. 10.1007/s002200050521

7.

ZworskiM. A remark on a paper of E. B. Davies. Proc Amer Math Soc (2001) 129:2955–7. 10.1090/s0002-9939-01-05909-3

8.

BenderCMBoettcherPN. Real spectra in non-Hermitian Hamiltonians having PT symmetry. Phys Rev Lett (1998) 80:5243–6. 10.1103/physrevlett.80.5243

9.

SieglPKrejčiříkD. On the metric operator for the imaginary cubic oscillator. Phys Rev D (2012) 86:121702(R. 10.1103/physrevd.86.121702

10.

DenckerNSjöstrandJZworskiM. Pseudospectra of semiclassical (pseudo-) differential operators. Comm Pure Appl Math (2004) 57:384–415. 10.1002/cpa.20004

11.

HelfferB. Spectral theory and its applications. New York: Cambridge University Press (2013).

12.

ArnalASieglP. Generalised airy operators preprint on arXiv:2208.14389 (2022).

13.

DaviesEB. Pseudo-spectra, the harmonic oscillator and complex resonances. Proc R Soc Lond A (1999) 455:585–99. 10.1098/rspa.1999.0325

14.

MityaginBSieglPViolaJ. Differential operators admitting various rates of spectral projection growth. J Funct Anal (2017) 272:3129–75. 10.1016/j.jfa.2016.12.007

15.

BoultonL. The non-self-adjoint harmonic oscillator, compact semigroups and pseudospectra. J Operator Theor (2002) 47:413–29.

16.

Pravda-StarovK. A complete study of the pseudo-spectrum for the rotated harmonic oscillator. J Lond Math. Soc. (2006) 73:745–61. 10.1112/s0024610706022952

17.

Bordeaux MontrieuxW. Estimation de résolvante et construction de quasimode près du bord du pseudospectre (2013). Preprint on arXiv:1301.3102

18.

ArnalASieglP. Resolvent estimates for one-dimensional Schrödinger operators with complex potentials. J Funct Anal (2023) 284:109856. 10.1016/j.jfa.2023.109856

19.

ArifoskiASieglP. Pseudospectra of the damped wave equation with unbounded damping. SIAM J Math Anal (2020) 52:1343–62. 10.1137/18m1221400

20.

KrejčiříkDNguyen DucT. Pseudomodes for non-self-adjoint Dirac operators. J Funct Anal (2022) 282:109440. 10.1016/j.jfa.2022.109440

21.

Nguyen DucT. Pseudomodes for biharmonic operators with complex potentials. SIAM J Math Anal (2022) 55:6580–624. 10.1137/22m1470682

Summary

Keywords

pseudospectrum, non-self-adjointness, Schrödinger operators, complex potentials, WKB method

Citation

Krejčiřík D and Siegl P (2024) Pseudomodes of Schrödinger operators. Front. Phys. 12:1479658. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2024.1479658

Received

12 August 2024

Accepted

30 September 2024

Published

22 October 2024

Volume

12 - 2024

Edited by

Jose Luis Jaramillo, Université de Bourgogne, France

Reviewed by

Catherine Drysdale, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom

Michael Hitrik, University of California, Los Angeles, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Krejčiřík and Siegl.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: David Krejčiřík, david.krejcirik@fjfi.cvut.cz

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.