- Department of Education Sciences, University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy

Health care is a critical context due to unpredictable situations, demanding clients, workload, and intrinsic organizational complexity. One key to improve the quality of health services is connected to the shift in organization perspective of viewing patients as active consumers rather than passive users. Therefore, higher levels of customer orientation (CO) are expected to improve organizational service effectiveness. According to a cultural perspective to CO, the aim of the study was to explore how different leaders’ behaviors (task-oriented and relationship-oriented) interact with CO of health organizations. Specifically, the aim of the paper was to contribute to this topic, by considering the leaders’ point of view. Since leader’s experience of CO is influenced by social processes in the work environment, workplace social support (WSS) was inserted as moderator in the relationship between leader behavior and CO. A survey study was conducted among 57 Health Department directors belonging to the National Health Service in the North of Italy in 2016. Findings showed that WSS moderated the influence of leadership concern for relationship on CO. Practical implications of the study are discussed.

Introduction

Health care is a critical context due to unpredictable situations, demanding clients, workload, and intrinsic organizational complexity. The need for health-care quality improvement in a period of increasing financial and service pressures requires to not separate financial performance and productivity from service quality. The King’s Fund (2013) points out that the quality of care provided by health organizations is a corporate responsibility: “Boards should be held to account for ensuring that their organizations achieve high standards of patient care, and that serial failures do not occur” (p. 9). The Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2001) report articulates six critical aims for health-care system. Care must be delivered by systems that are carefully and consciously designed to provide care that is safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.

One key to improve the quality of health services is connected to the shift in organizations’ perspective of viewing customers as active co-producers rather than users. Aiming at patient-centered care, hospital business is required to treat patients as customers. By considering customers as the first priority, not only client and staff satisfaction significantly increases as positive relationships with patients act as protective factors and lessen social stressors (Guglielmetti et al., 2014), but also clinical care outcomes improve (Zablah et al., 2012; Rania et al., 2015), following the double empowerment effect between customers and workers that has been highlighted in previous studies (Converso et al., 2015). Customer orientation (CO) predicts several important customer outcomes, such as customer-perceived service quality and satisfaction (Susskind et al., 2003), indicating that health providers’ delivering service on the front lines have an influence on patients’ experience with services. Moreover, leadership has a primary role in supporting organizational CO (Liao and Subramony, 2008). In the next sections, we described the concept of CO and the role of leadership in relation to it.

Customer Orientation

The term CO means the focus on meeting customers’ interests, needs, and expectations, and on delivering appropriate and personalized services. In the case of the health-care sector, where patients are the customers, it is defined as the ability of service providers to adjust their service, in a way that reflects patients’ reality (Daniel and Darby, 1997).

The concept has been approached in two distinct ways. The first one considers CO as a personal attitude or a surface-level personality trait, which refers to “an employee’s tendency or predisposition to meet customer needs in an on-the-job context” (Brown et al., 2002, p. 111) and as an antecedent of job outcomes as job satisfaction and job performance (Donavan et al., 2004; Matthews et al., 2016; Miao and Wang, 2016).

The second one considers CO as a set of organizational behaviors (Saxe and Weitz, 1982) connected to the organizational culture (Narver and Slater, 1990). CO is a service practice that assesses “the degree to which an organization emphasizes, in multiple ways, meeting customer needs and expectations for service quality” (Schneider et al., 1998, p. 153). It is embedded within the marketing concept of the health organization and promotes the dissemination of market-related knowledge, enabling the organization to deliver high quality care in a consistent and immediate manner (Hallums, 2008). Following Normann (1984), this approach permits to recognize the impact on the service quality of the quality of the relationship between customer and provider as well as between provider and leader. Indeed, the two different relationships are strictly interrelated: the quality of relationship is like a cascade flow from the back-office (or the top) to the front-line of the service process. In this way, although being patient-focused is essential, effective CO presupposes also to consider internal customers. “Because internal customers (employees) provide services to external customers (patients), their role is vital for delivering care of high quality and satisfying patients. […] employees will be willing to do their best in order to satisfy the needs of patients only after effective internal exchanges at their level have taken place. For this reason, unless an organization focuses on internal operational excellence, other than the market, continuous achievement and organizational effectiveness cannot be achieved” (Bellou, 2010, p. 386).

Most of the studies on CO conclude their discussion with managerial implications. All of them recommend formal leaders to implement specific organizational strategies to improve CO. In the next section, we explored the managerial issues related to CO. Following McVicar (2016), we split managerial issues into leadership behaviors (Blake and Mouton, 1964, 1982; Pruitt and Rubin, 1986) and workplace social support (WSS; Hobfoll, 2002).

Leadership Behaviors and Customer Orientation

Leadership is considered one of the most important determinants on organizational processes: the quality of leadership has been linked to a multitude of outcomes within occupational health psychology. There is ample evidence suggesting that leaders play a key role in influencing employee attitudes toward customers (Liao and Subramony, 2008). “Managerial philosophies and values influence organization’s internal business practices, which, in turn, influence employee and customer interactions and behaviors” (Susskind et al., 2003, p. 180). In the medical literature, effective leaders, from executives to front-line managers, have been shown to contribute to the implementation of an organizational culture that values quality of care. Leaders can encourage care quality by promoting CO (Gountas and Gountas, 2016), patient-centered care, rather than provider-centered (Pelzang, 2010; Cliff, 2012; Dell’Aversana and Bruno, 2017) and patient safety (Kaplan et al., 2010; Bruno and Bracco, 2016). As Shaller (2007) pointed out, the most important factor contributing to health-care improvement is the commitment and engagement of senior leadership. Specifically, leadership has a crucial function since it determines the quality of relationship within the team, thus influencing the quality between employees and clients. Sustaining the quality of relationship within the team (internal clients) improves the quality of relationship with the external clients, thus permitting to increase the quality of health services (Corrigan et al., 2000; Kim and Lee, 2016).

Reviews covering decades of leadership research agree on two predominant types of leadership behavior: relations-oriented behavior and task-oriented behavior (Judge et al., 2004). Differences in leaders’ performance can be explained by the extent to which the leader is task- or person-oriented (Yukl et al., 2002; Kellett et al., 2006; Gaubatz and Ensminger, 2017). In particular, Stock and Hoyer (2002) found positive relationships between employees’ CO and different leadership styles: leaders’ emphasis on task achievement, leaders’ supportiveness, and initiation of CO. Moreover, there is evidence that leader’s CO predicts employee’s CO (Strong, 2006).

Although leadership behaviors appear as a crucial factor for promoting a culture that focuses on customer relationships and customer service (Anaza et al., 2016), according to Liaw et al. (2010), “it is somewhat surprising that the ways in which leadership behaviors influence customer orientation have received little attention in the existing literature” (p. 478). Indeed, in previous studies, researchers have attempted to identify the antecedents of CO by examining predominantly the main effects of leadership on CO employees’ perceptions. Compared with the large literature on employees, less attention has been paid on CO for organizational leaders (Schuh et al., 2012).

Workplace Social Support

Workplace Social Support (WSS) is a key construct implicated with a variety of health and organizational outcomes: it is a resource in the work environment which can be employed in dealing with complex problems (De Jonge et al., 2008).

More specifically, in the cultural perspective of CO expressive emotional network resources are recognized as drivers of CO, as form of social capital that provides direct access to information and emotional support to improve CO (Anaza et al., 2016). WSS may increase performance in two ways: “first, it provides individuals with emotional support. Second, having a network for emotional support among coworkers helps employees maintain the required patience, care, and focus needed to provide high-quality customer service even in the face of challenging interactions. Coworker support provides greater job resources to deal with stressful and difficult customers” (Anaza et al., 2016, p. 1475). In this way, WSS plays a role in creating value for customers. Walsh et al. (2015) claimed that CO is affected by WSS, finding that an empowered work environment enhances employees’ affective responses and these affective responses should spillover to the employee–customer interface, leading to a greater level of CO.

The same process has not yet been explored for leaders. Tepper and Taylor (2003) argued that supervisors who perceived they were treated fairly by the organization could reciprocate by treating subordinates more favorably. Expressive emotional network resources may support leaders in their middle position between customers’ service excellence demands on one hand, and productivity and performance requirements on the other hand (Babakus et al., 2009; Cortini, 2016). Indeed, there is evidence on the different way that managerial and non-managerial employees perceive organizational values (Schneider et al., 1998) and on the different extent to which they focus on customers’ needs (Martin and Fraser, 2002).

According to the cultural perspective to CO, we expect that leader’s experience of external CO is influenced by social processes in the workplace. Therefore, in our study, the focus is on leaders. Focusing on formal leaders does not imply that leadership as social influence is limited to these roles, but means that those in formal leadership roles have a particularly strong potential to affect outcomes relevant to organizations, especially the organizational culture, that in turns influences the quality of care (Kaissi et al., 2004).

Aims

In light of the previous theoretical constructs, the aim of this study was to analyze leaders’ perceived CO in relation to leadership behavior and WSS in the health-care service context.

More specifically, we explored (a) the different ways leaders’ behavior (task-oriented and/or relationship-oriented) is related to a wider or lesser CO and (b) if the WSS moderates this relationship.

Method

A survey study was conducted among 62 Health Department directors belonging to the National Health Service in the North of Italy in 2016. All the directors were attending a course of managerial competences revalidation.

Participants were given an anonymous questionnaire, of whom 57 were usable. All subjects gave written informed consent and authorized and approved the use of anonymous/collective data for publications. Given the masculine dominant nature of our sample, we did not consider gender as a control variable.

In line with recent works (Thomas et al., 2001; Anaza et al., 2016), the CO was measured through the SOCO Scale (Saxe and Weitz, 1982). We used the 24-item, 9-point version revisited by Hoffman and Ingram (1992) in order to fit the health-care sample (α = 0.89). Examples of items are as follows: “I try to help patients achieve their goal”; “I try to achieve my goal by satisfying patients.”

In relation to leadership, the two dimensions ‘concern for task’ and ‘concern for relationship’ were measured through Blake and Mouton’s (1982) Managerial Grid, on which research and theory on leadership converges and the Dual Concern Theory is based (Pruitt and Rubin, 1986; Kellett et al., 2006; Garg and Jain, 2013). We used eight items of the subscale ‘Concern for task’ (α = 0.58) and eight items of the subscale ‘Concern for relationship’(α = 0.69), scored on a 5-point rating scale. Sample items are as follows: “Nothing is more important than accomplishing a goal or task” for ‘Concern for task’; “I encourage my team to participate when it comes decision making time and I try to implement their ideas and suggestions” for ‘Concern for relationship.’

Workplace social support (WSS) was measured through six items of the Demand-Induced Strain Compensation Questionnaire in its 5-point scale, Italian version (Bova et al., 2015) (α = 0.74). Sample items include: “Employee X will feel esteemed at work by others.”

Findings

Preliminary Analysis

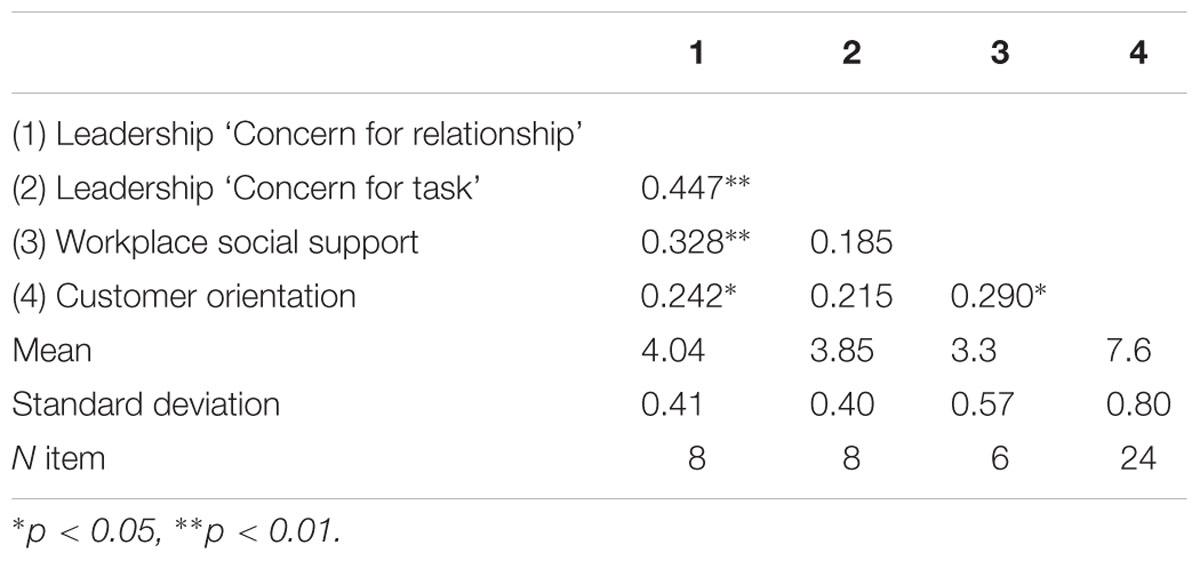

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) and correlation of research variables are shown in Table 1. Significant positive relationships are shown between leadership concern for relationship, CO, and WSS, whereas leadership for task correlates positively with leadership concern for relationship. To address the common method bias, we adopted the Harman’s single-factor test (Conway and Lance, 2010).

Moderation Analysis

Two moderated regression analyses were used to test the moderating role of the WSS on the relationship between leadership behavior (‘concern for task’ and ‘concern for relationship’) and CO. We used PROCESS macro for SPSS developed by Hayes (2013), using model n. 1. In the first analysis, we had leadership concern for relationship as independent variable, the WSS as moderator, and CO as dependent variable. In the second one, we tested leadership concern for task as independent variable with the same moderator and dependent variables. The variables were mean-centered prior to analysis.

Leadership ‘Concern for Relationship’

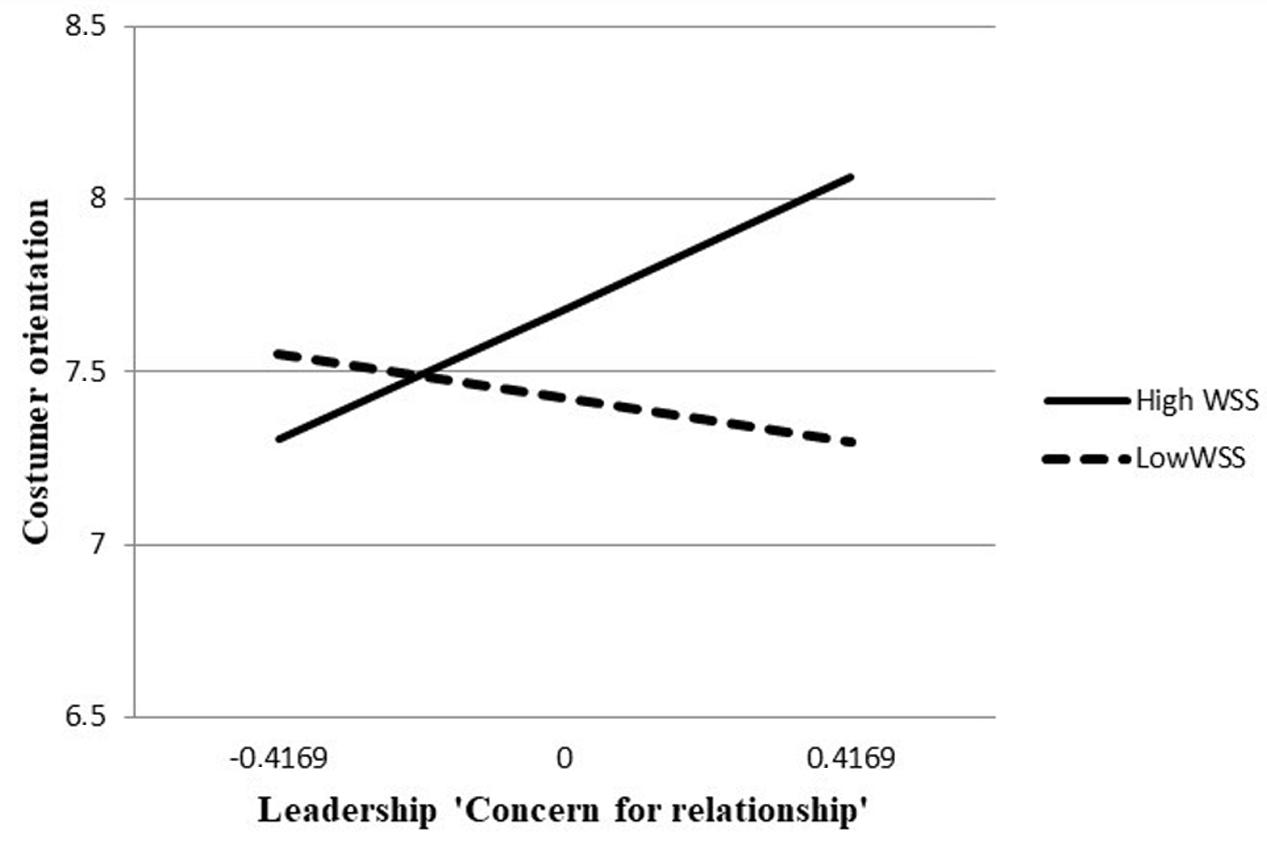

Regression analysis found there was no main effect of leadership concern for relationship on CO [b = 0.30, SE = 0.25, t(53) = 1.21, p = 0.2294] and of WSS on CO [b = 0.22, SE = 0.18, t(53) = 1.23, p = 0.2224]. Most importantly, we obtained the interaction between leadership concern for relationship and WSS on CO [b = 1.05, SE = 0.37, t(53) = 2.83, p = 0.0065]. As shown in Figure 1, analyses revealed that leadership concern for relationship was positively related with CO for higher levels of WSS, b = 90, SE = 0.32, t(53) = 2.80, p = 0.0070. Conversely, the relationship between leadership concern for relationship and CO was not significant for lower levels of WSS, b = -30, SE = 0.33, t(53) = -0.92, p = 0.3615 (Figure 1).

Leadership ‘Concern for Task’

Analyses revealed that there was no main effect of leadership concern for task on CO, b = 0.35, SE = 0.26, t(53) = 1.37, p = 0.1758 and of WSS on CO, b = 0.20, SE = 0.20, t(53) = 1.02, p = 0.3107. Moreover, analyses revealed no significant interaction between leadership concern for task and WSS on CO, b = 0.96, SE = 0.50, t(53) = 1.92, p = 0.0605.

Discussion, Conclusion, and Practical Implications

Due to the role of the health service culture in the development of service quality and customer perceptions of organizational image (Senge, 2006), there is a need to study the factors that affect the quality of CO, including leaders’ behavior and WSS. Our study contributes to the debate analyzing the different ways leaders’ behavior is related to a wider or lesser CO and if WSS moderates this relationship.

Findings did not show any direct effect of leadership behaviors on CO. This effect was moderated by the presence of higher level of WSS. Findings showed that the abovementioned resources moderated the relationship between leadership concern for relationship and CO. No moderating effect was found for the relationship between leadership concern for task and CO. However, this finding could be affected by the poor reliability of the leadership ‘concern for task’ scale.

Findings highlight the important role of WSS in stimulating health-relevant aspects of leadership behavior (Gregersen et al., 2016). In fact, the leadership dimension ‘concern for relationship’ seems to be related to CO, only if leaders can refer to higher resources in their work environment. Undoubtedly, listening to information from the front-line, sharing information, taking care of the quality of relationship with and among their collaborators, monitoring their identification in organizational values and patients’ needs, using feedback is high-demanding. One key point emerging from this study is that providing health-care contexts with higher expressive emotional network resources could facilitate leadership focusing both internal and external clients (Cortini et al., 2016).

A second key point of the study is the different roles of leaders’ behaviors. ‘Concern for task’, i.e., the focus on task and goals achievement, is traditionally considered the primary dimension of leadership in the bureaucratic model, in which standardization of procedures is the answer to the complexity of organizational processes as well as to the need for transparency of Public Administrations.

On the contrary, service organizations need to take into account the variability of the clients and the need for personalization of services. The diversity of each client, inputting variance and risk of fragmentation into the system, requires leaders to protect integrative functions. This study supports the need for health services to interpret leaders’ role as not merely oriented to accomplishment of tasks and focus on goal, standards, and performance. In this direction, leadership means maintaining or improving processes that facilitate accomplishment of tasks not only by clarifying role expectations and standards for task performance, but also by caring for their collaborators. “Relations-behaviors largely concern maintaining or improving cooperative interpersonal relationships that build trust and loyalty. Relations-behaviors include listening carefully to others to understand their concerns, providing support and encouragement, helping, and recognizing people as individuals” (Kellett et al., 2006, p. 150).

Our findings offer several implications. First, if the health system wants to increase its patient-centeredness, it must take care of its leaders, by providing them with resources in their job context, and more specifically social support resources. For instance, leaders have to be accompanied through recruitment and training to make their managerial competencies related to concern for relationship more visible, accessible, and reflective (Bruno and Dell’Aversana, 2017a,b,c). In Italy, this issue is quite relevant, since in health domain directors are primarily chosen on their technical skills. On the contrary, their leadership competencies are generally taken for granted, and not always evaluated or trained before and during their work experience as leaders.

A further implication is based on the acknowledgment that the quality of relationship in the back-office may have an important effect on the quality and degree of CO. Hence, the study extends work that has shown the relationship between internal and external marketing (Kim and Lee, 2016). Organizations need to provide devices to focus on internal marketing in order to sustain CO.

Limitations

There are some limitations to the present research. The main limitations are the small sample size, the cross-sectional design of the study, and its reliance on self-report measures. Future longitudinal studies should investigate other causal directions or even reciprocal relations of the variables more profoundly. Second, the study used single-source data. Future research may overcome this limitation by collecting data from multiple sources, for instance, customer assessments of health service and collaborators’ evaluation of leadership behavior. We have not addressed the relationship of CO and traditional performance measures. Future research is necessary to integrate these outcomes.

Ethics Statement

The questionnaire included a statement regarding the personal data treatment, in accordance with the Italian privacy law (Law Decree DL-196/2003). The workers authorized and approved the use of anonymous/collective data for scientific publications. Because the data were collected anonymously and the research investigated psychosocial variables not adopting a medical perspective, ethical approval was not sought.

Author Contributions

AB, GDA, and AZ conceptualized the study and the theoretical framework. AB wrote the Section “Introduction.” AB and AZ collected data. GDA analyzed the data and wrote the Sections “Method” and “Findings.” AB wrote the Section “Discussion, Conclusion, and Practical Implications.” All the authors then revised and improved the manuscript several times.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank very much all the participants involved in this research.

References

Anaza, N. A., Nowlin, E. L., and Wu, G. J. (2016). Staying engaged on the job: the role of emotional labor, job resources, and customer orientation. Eur. J. Mark. 50, 1470–1492. doi: 10.1108/EJM-11-2014-0682

Babakus, E., Yavas, U., and Ashill, N. J. (2009). The role of customer orientation as a moderator of the job demand–burnout–performance relationship: a surface-level trait perspective. J. Retail. 85, 480–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2009.07.001

Bellou, V. (2010). The role of learning and customer orientation for delivering service quality to patients. J. Health Organ. Manag. 24, 383–395. doi: 10.1108/14777261011064995

Blake, R. R., and Mouton, J. S. (1982). Theory and research for developing a science of leadership. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 18, 275–291. doi: 10.1177/002188638201800304

Bova, N., De Jonge, J., and Guglielmi, D. (2015). The demand-induced strain compensation questionnaire: a cross-national validation study. Stress Health 31, 236–244. doi: 10.1002/smi.2550

Brown, T. J., Mowen, J. C., Donavan, D. T., and Licata, J. W. (2002). The customer orientation of service workers: personality trait effects on self- and supervisor performance ratings. J. Mark. Res. 39, 110–119. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.39.1.110.18928

Bruno, A., and Bracco, F. (2016). Promoting safety through well-being: an experience in healthcare. Front. Psychol. 7:1208. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01208

Bruno, A., and Dell’Aversana, G. (2017a). Reflective practice for psychology students: the use of reflective journal feedback in higher education. Psychol. Learn. Teach. 16, 248–260. doi: 10.1177/1475725716686288

Bruno, A., and Dell’Aversana, G. (2017b). Reflective practicum in higher education: the influence of the learning environment on the quality of learning. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 1–14. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2017.1344823

Bruno, A., and Dell’Aversana, G. (2017c). ‘What shall I pack in my suitcase?’: the role of work-integrated learning in sustaining social work students’ professional identity. Soc. Work Educ. 1–15. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2017.1363883

Cliff, B. (2012). Patient-centered care: the role of healthcare leadership. J. Healthc. Manag. 57, 381–383. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2017.1363883

Converso, D., Loera, B., Viotti, S., and Martini, M. (2015). Do positive relations with patients play a protective role for healthcare employees? Effects of patients’ gratitude and support on nurses’ burnout. Front. Psychol. 6:470. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00470

Conway, J. M., and Lance, C. E. (2010). What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. J. Bus. Psychol. 25, 325–334. doi: 10.1007/s10869-010-9181-6

Corrigan, P. W., Lickey, S. E., Campion, J., and Rashid, F. (2000). Mental health team leadership and consumers’ satisfaction and quality of life. Psychiatr. Serv. 51, 781–785. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.6.781

Cortini, M. (2016). Workplace identity as a mediator in the relationship between learning climate and job satisfaction during apprenticeship: suggestions for HR practitioners. J. Workplace Learn. 28, 54–65. doi: 10.1108/JWL-12-2015-0093

Cortini, M., Pivetti, M., and Cervai, S. (2016). Learning climate and job performance among health workers. A pilot study. Front. Psychol. 7:1644. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01644

Daniel, K., and Darby, D. N. (1997). A dual perspective of customer orientation: a modification, extension and application of the SOCO scale. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 8, 131–147. doi: 10.1108/09564239710166254

De Jonge, J., Le Blanc, P. M., Peeters, M. C., and Noordam, H. (2008). Emotional job demands and the role of matching job resources: a cross-sectional survey study among health care workers. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 45, 1460–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.11.002

Dell’Aversana, G., and Bruno, A. (2017). Different and similar at the same time. Cultural competence through the lens of healthcare providers. Front. Psychol. 8:1426. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01426

Donavan, D. T., Brown, T. J., and Mowen, J. C. (2004). Internal benefits of service-worker customer orientation: job satisfaction, commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Mark. 68, 128–146. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.68.1.128.24034

Garg, S., and Jain, S. (2013). Mapping leadership styles of public and private sector leaders using Blake and mouton leadership model. Drishtikon 4, 48–64.

Gaubatz, J. A., and Ensminger, D. C. (2017). Department chairs as change agents: leading change in resistant environments. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 45, 141–163. doi: 10.1177/1741143215587307

Gountas, S., and Gountas, J. (2016). How the ‘warped’ relationships between nurses’ emotions, attitudes, social support and perceived organizational conditions impact customer orientation. J. Adv. Nurs. 72, 283–293. doi: 10.1111/jan.12833

Gregersen, S., Vincent-Höper, S., and Nienhaus, A. (2016). Job-related resources, leader–member exchange and well-being–a longitudinal study. Work Stress 30, 356–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00368.x

Guglielmetti, C., Gilardi, S., Accorsi, L., and Converso, D. (2014). The relationship with patients in healthcare: which workplace resources can lessen the impact of social stressors? Psicol. Salute 2, 121–137. doi: 10.3280/PDS2014-002008

Hallums, A. (2008). Developing a market orientation. J. Nurs. Manag. 2, 87–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.1994.tb00134.x

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 6, 307–324. doi: 10.1037//1089-2680.6.4.307

Hoffman, K. D., and Ingram, T. N. (1992). Service provider job satisfaction and customer-oriented performance. J. Serv. Mark. 6, 68–77. doi: 10.1108/08876049210035872

IOM (2001). Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Judge, T. A., Piccolo, R. F., and Ilies, R. (2004). The forgotten ones? The validity of consideration and initiating structure in leadership research. J. Appl. Psychol. 89:36. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.1.36

Kaissi, A., Kralewski, J., Curoe, A., Dowd, B., and Silversmith, J. (2004). How does the culture of medical group practices influence the types of programs used to assure quality of care? Health Care Manag. Rev. 29, 129–138.

Kaplan, H., Brady, P., Dritz, M., Hooper, D., Linam, W., Froehle, C., et al. (2010). The influence of context on quality improvement success in healthcare: a systematic review of the literature. Milbank Q. 88, 500–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00611.x

Kellett, J. B., Humphrey, R. H., and Sleeth, R. G. (2006). Empathy and the emergence of task and relations leaders. Leadersh. Q. 17, 146–162. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.12.003

Kim, B., and Lee, J. (2016). Relationships between personal traits, emotional intelligence, internal marketing, service management, and customer orientation in Korean outpatient department nurses. Asian Nurs. Res. 10, 18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2015.10.005

Liao, H., and Subramony, M. (2008). Employee customer orientation in manufacturing organizations: joint influences of customer proximity and the senior leadership team. J. Appl. Psychol. 93, 317–328. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.317

Liaw, Y. J., Chi, N. W., and Chuang, A. (2010). Examining the mechanisms linking transformational leadership, employee customer orientation, and service performance: the mediating roles of perceived supervisor and coworker support. J. Bus. Psychol. 25, 477–492. doi: 10.1007/s10869-009-9145-x

Martin, L. A., and Fraser, S. L. (2002). Customer service orientation in managerial and non-managerial employees: an exploratory study. J. Bus. Psychol. 16, 477–484. doi: 10.1023/A:1012885310251

Matthews, L. M., Zablah, A. R., Hair, J. F., and Marshall, G. W. (2016). Increased engagement or reduced exhaustion: which accounts for the effect of job resources on salesperson job outcomes? J. Mark. Theory Pract. 24, 249–264. doi: 10.1080/10696679.2016.1170532

McVicar, A. (2016). Scoping the common antecedents of job stress and job satisfaction for nurses (2000–2013) using the job demands–resources model of stress. J. Nurs. Manag. 24, 112–136. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12326

Miao, C. F., and Wang, J. (2016). The differential effects of functional vis-à-vis relational customer orientation on salesperson creativity. J. Bus. Res. 69, 6021–6030. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.05.017

Narver, J. C., and Slater, S. F. (1990). The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. J. Mark. 54, 20–35. doi: 10.2307/1251757

Normann, R. (1984). Service Management: Strategy and Leadership in Service Business. Chichester: Wiley.

Pelzang, R. (2010). Time to learn: understanding patient-centred care. Br. J. Nurs. 19, 912–917. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2010.19.14.49050

Pruitt, D. G., and Rubin, J. Z. (1986). Social Conflict: Escalation, Stalemate and Settlement. New York, NY: Random House.

Rania, N., Migliorini, L., Zunino, A., Bianchetti, P., Vidili, M. G., and Cavanna, D. (2015). La riabilitazione oncologica: qualità della cura e benessere psicologico del paziente. Salute Soc. 2, 60–73. doi: 10.3280/SES2015-002005

Saxe, R., and Weitz, B. A. (1982). The SOCO scale: a measure of the customer orientation of salespeople. J. Mark. Res. 19, 343–351. doi: 10.2307/3151568

Schneider, B., White, S. S., and Paul, M. C. (1998). Linking service climate and customer perception of service quality: tests of a causal model. J. Appl. Psychol. 83, 150–163. doi: 10.1037//0021-9010.83.2.150

Schuh, S. C., Egold, N. W., and van Dick, R. (2012). Towards understanding the role of organizational identification in service settings: a multilevel study spanning leaders, service employees, and customers. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 21, 547–574. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2011.578391

Senge, P. M. (2006). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Shaller, D. (2007). Patient-Centered Care: What Does It Take?. New York City, NY: The Commonwealth Fund.

Stock, R. M., and Hoyer, W. D. (2002). Leadership style as a driver of salespersons’ customer orientation. J. Mark. Focus. Manag. 5, 355–376. doi: 10.1023/B:JMFM.0000008074.24518.ea

Strong, C. A. (2006). Is managerial behavior a key to effective customer orientation? Total Qual. Manag. 17, 97–115.

Susskind, A. M., Kacmar, K. M., and Borchgrevink, C. P. (2003). Customer service providers’ attitudes relating to customer service and customer satisfaction in the customer-server exchange. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 179–187. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.179

Tepper, B. J., and Taylor, E. C. (2003). Relationships among supervisors’ and subordinates’ procedural justice perceptions and organizational citizenship behaviors. Acad. Manag. J. 46, 97–105. doi: 10.2307/30040679

The King’s Fund (2013). Patient-centred Leadership. Rediscovering our Purpose. London: The King’s Fund.

Thomas, R. W., Soutar, G. N., and Ryan, M. M. (2001). The selling orientation-customer orientation (S.O.C.O.) scale: a proposed short form. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 21, 63–69.

Walsh, G., Yang, Z., Dose, D., and Hille, P. (2015). The effect of job-related demands and resources on service employees’ willingness to report complaints: Germany versus China. J. Serv. Res. 18, 193–209. doi: 10.1177/1094670514555510

Yukl, G., Gordon, A., and Taber, T. (2002). A hierarchical taxonomy of leadership behavior: integrating a half century of behavior research. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 9, 15–32. doi: 10.1177/107179190200900102

Keywords: customer orientation, health service, leadership, workplace social support, task-oriented behavior, relationship-oriented behavior, patient-centered care

Citation: Bruno A, Dell’Aversana G and Zunino A (2017) Customer Orientation and Leadership in the Health Service Sector: The Role of Workplace Social Support. Front. Psychol. 8:1920. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01920

Received: 01 June 2017; Accepted: 17 October 2017;

Published: 01 November 2017.

Edited by:

Gabriele Giorgi, European University of Rome, ItalyReviewed by:

Michela Cortini, Università degli Studi “G. d’Annunzio”, ItalyDaniela Converso, Università degli Studi di Torino, Italy

Copyright © 2017 Bruno, Dell’Aversana and Zunino. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andreina Bruno, YW5kcmVpbmEuYnJ1bm9AdW5pZ2UuaXQ=

Andreina Bruno

Andreina Bruno Giuseppina Dell’Aversana

Giuseppina Dell’Aversana Anna Zunino

Anna Zunino