A commentary on

The ‘Musilanguage’ Model of Language Evolution

by Brown, S. (2000). The Origins of Music. eds S. Brown, B. Merker, and N. L. Wallin (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 271–300. doi: 10.1037/e533412004-001

The model of musilanguage (Brown, 2000, 2017) requires a new musicological term to refer to its texture. Like choral singing, and unlike speech, musilanguage is based on simultaneous vocalization of multiple participants who reproduce the same signal (call) at random time intervals and pitch levels, akin to a wolf “chorus.1” Voiced utterances produce multiple pitches, generating a “jumbled” texture, similar to polyphony and heterophony, but not fully qualifying as such.

The term “heterophony” was introduced by Stumpf (1897) to refer to the fusion of sounds whose components retained their singular identity. Stumpf discovered this word in Plato's Laws (Plato, 2013, p. 203), where it referred to pitch and rhythm discrepancy between the vocals and the lyre performing the same tune. Four years later, Stumpf (1901) reused this term to describe Thai music. He characterized heterophony as the looping of simultaneous melodic paraphrases [Umspielen], where parts generally followed the same melodic contour while differing in detail, so that minute discrepancies would meet again in unison.

Adler (1908) conceptualized heterophony as a style alternative to homophony and polyphony, applicable across Siamese, Japanese, Javanese, and Russian musics. He specifically found Russian heterophony to present a paradigm of heterophonic arrangement, designed to make melodic repetition less monotonous and more idiosyncratic for each singer's voice.

The Russian Musical Encyclopedia defines heterophony as a multi-part music generated by the collective performance of the same melody, where parts contain deviations from the principal melodic formula (Mueller, 1973). Such organization is regarded as a general textural type of ornamental, harmonic, and/or polyphonic variation that can complicate classification. Indeed, already in 1911, Stumpf criticized Adler for misapplication of the term (Stumpf and David, 2012). The keynote of heterophony is an ongoing melodic repetition with numerous intermittent variations, which seems to apply to musilanguage chorusing (Brown, 2007). However, such chorusing contains no synchronization, whereas heterophony implies prevalent synchronization of parts.

Swan (1943) defined heterophony as “a principal melody improvised simultaneously by several singers, retaining its main outline in each voice, yet showing enough independence to result in places in 2- and 3- and even 4-part harmony2.” The Grove Dictionary (Cooke, 2001), following Swan's definition, emphasizes a collective synchronized execution. Although the notation example provided in the Grove article shows a consistent misalignment of 5 parts (Knudsen, 1968), such heterophony is rare and does not sound “jumbled3.” Its asynchronicities remain minimal (<half-a-beat). Longer asynchronies (≥beat) generate polyphonic imitations, where the same melody becomes deliberately distributed between multiple parts to produce juxtapositions at certain temporal intervals4.

Polyphony is “a style of simultaneously combining number of parts, each forming an individual melody and harmonizing with each other” (Oxford Dictionary). Despite its association with Western art-music, polyphony penetrated Western popular (Bukofzer, 1940) and traditional music (Ahmedaja, 2011), prompting research of non-European polyphony (Arom, 2004; Jordania, 2006). Many ethnomusicologists prefer alternative terms (diaphony, disphony), while others treat “polyphony” as an umbrella term for any multi-part music, setting terminological confusion (Cooke, 2001). Current consensus defines polyphony as “a mode of expression based on simultaneous combination of separate parts, perceived and produced intentionally in their mutual differentiation, in a given formal order” (Agamennone, 1996)5.

Polyphonic and heterophonic textures differ in orderliness: heterophonic parts are inadvertent, unlike polyphonic parts (Tallmadge, 1984). Polyphony induces individualization of parts by means of sharpening their functional contrast in texture. Hence, synchronization is even more important for polyphony—parts must align in pitch and time throughout the entirety of music. This makes polyphonic performance metrically stricter than heterophonic performance.

Even stricter is synchronization in another “classic” texture—homophony—“music in which all melodic parts move together at more or less the same pace” (Hyer, 2001). Contrary to common belief, homophony is not bound to European music alone (Nikolsky, 2016). Its reliance on chords and harmonic intervals demands high concision in tones' onsets: in the order of under 100 msec (Huron, 2001), typically, 30–50 msec (Rasch, 1988).

All “classic” textures rely on harmonic, metric, and thematic integrity of parts. Performers attune their performance to the pitch of their partners, the manifestation of beat in their rhythms, and the distribution of musical material across parts—what musicologists call “thematic material” and consider an expressive point of a musical work by which it can be remembered (Drabkin, 2001). In this semiotic sense (Réti, 1951), the notion of thematicity is applicable to folk and non-Western music (Mazel, 1960). However, harmonicity, metricity, and thematicity are inadmissible for musilanguage. Even modifying “classic” terms (e.g., “jumbled heterophony”) would constitute a misnomer: musilanguage inherently lacks any form of arrangement of parts.

Since musilanguage occupies an evolutionary position between the “natural” animal vocalizations and the simplest human oral communication, it predates mode, scale, meter—and therefore, heterophony and polyphony. This situation calls for a new term—isophony: texture that uses brief calls, continuously reproduced by multiple performers with irrational deviations in timing and pitch, where each participant retains idiosyncrasy of the rhythmic, timbral, and directional attributes of the pitch contour—altogether producing a “jumbled” effect (Nikolsky, 2016, Appendix-5)6. Vocalization can be considered “isophonic” if it maintains a single call as a unit of texture, scalable shorter/longer and higher/lower through the continuum of duration and frequency for every participating part—consistently reproducing that call out-of-sync in relation to the moment of its onset or termination.

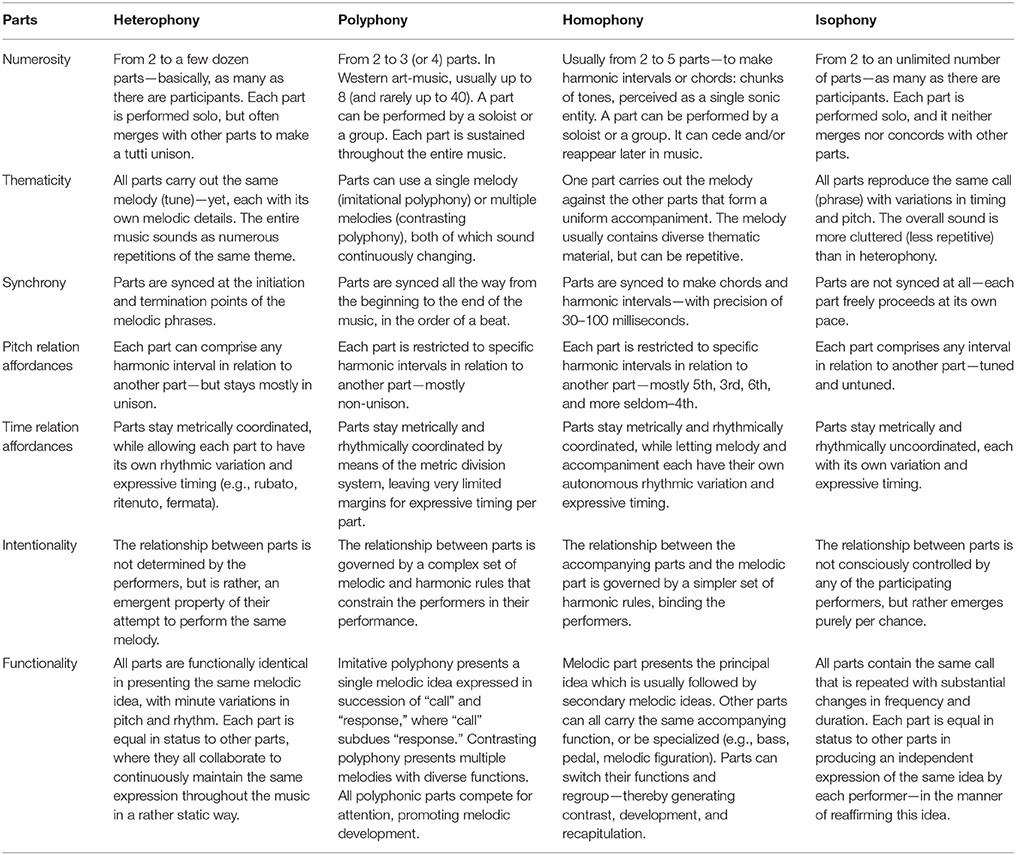

Isophony contrasts “classic” textures by its tendency to expose each participant's identity without enmeshing into the ensemble. Isophony involves the assembly of individuals, rather than a single entity (“choir”). Isophonic tones never meet in unison or in beat, and are devoid of any form of harmonization7. Isophony's only feature of tonal organization is the uniformity of the melodic and timbral characteristics of a call. The function of isophonic texture is to attract attention to each participant's expression of the same state of mind. The important features that distinguish isophony from heterophony, polyphony, and homophony are summarized in the Table 1.

Conceptualization of isophony as a primordial texture that predated music, establishes the lineage in the morphological evolution of music, allowing comparative cross-examination of musical structures in multi-part music.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

AN was employed by company, Braavo Enterprises as a technical and creative director. Braavo Enterprises specializes in developing content for educational and edutainment programs for children of 5–11 years of age.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^The sample of a wolf pack howling can be heard at:http://chirb.it/kFLxIC. It is characterized by the reproduction of the same call at various speeds and pitch levels, without any synchronization of the onset and termination points of the calls.

2. ^I have italicized those words in the definition that imply the general coordination in time between the performances of all the participants.

3. ^An example of the Hebrides Psalm can be heard at: http://chirb.it/raeaOr. It presents a clear single melodic line that is “smudged” by consistent delays between different parts—presenting a rare style of melodic variation by means of a deliberate “reverberation” effect induced by the continuous sub-beat time lagging between parts.

4. ^Well-known examples of musical texture in monothematic imitational polyphony in folk music are round-songs. In art-music, Bach's “Musical Offering” BWV 1079 contains excellent demonstration of polyphonic arrangement of a single melody in the so-called “riddle canons”—notated as a melody solo ought to be performed by a few musicians who enter one by one in specific time intervals.

5. ^My italics emphasize points that distinguish polyphonic texture from heterophonic.

6. ^This appendix contains an overview of the evolution of musical texture, following the model of “histories of fine art”—see Table 2 (p. 13–16) in it.

7. ^An example of isophony is an Akia tribe song (courtesy of Anthony Seeger): http://chirb.it/ryANbJ. The leader coins the call (vocable “Tete”), and the tribe repeats it at various pitch levels and duration values, where each participant displays their specific social status through the relative duration of the same call (Seeger, 2004).

References

Adler, G. (1908). “Über heterophonie,” in Jahrbuch Der Musikbibliothek Peters XV, ed R. Schwartz (Leipzig: Edition Peters), 17–27.

Agamennone, M. (1996). Polifonie. Procedimenti, Tassonomie E Forme: Una Riflessione “a Più Voci.” Venice: Edizioni Il Cardo.

Ahmedaja, A. (2011). European Voices: Cultural Listening and Local Discourse in Multipart Singing Traditions in Europe, Vol. 2. Vienna; Koln; Weimar: Böhlau Verlag.

Arom, S. (2004). African Polyphony and Polyrhythm: Musical Structure and Methodology. Transl. by M. Thom, B. Tuckett, and R. Boyd. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, S. (2000). “The ‘Musilanguage’ model of language evolution,” in The Origins of Music, eds S. Brown, B. Merker, and N. L. Wallin (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 271–300.

Brown, S. (2007). Contagious heterophony: a new theory about the origins of music. Music. Sci. 11, 3–26. doi: 10.1177/102986490701100101

Brown, S. (2017). A joint prosodic origin of language and music. Front. Psychol. 8:1894. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01894

Bukofzer, M. F. (1940). Popular polyphony in the middle ages. Music. Quart. 26, 31–49. doi: 10.1093/mq/XXVI.1.31

Cooke, P. (2001). “Polyphony. Non-Western. General,” in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, eds S. Sadie and J. Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers).

Drabkin, W. (2001). “Theme,” in New Grove Dict. Music Music, eds S. Sadie S and J. Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers).

Huron, D. (2001). Tone and voice: a derivation of the rules of voice-leading from perceptual principles. Music Percept. 19, 1–64. doi: 10.1525/mp.2001.19.1.1

Hyer, B. (2001). “Homophony,” in New Grove Dict. Music Music, eds S. Sadie and J. Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers).

Jordania, J. (2006). Who Asked the First Question? The Origins of Human Choral Singing, Intelligence, Language and Speech. Tbilisi: Logos.

Knudsen, T. (1968). Ornamental hymn/psalm singing in Denmark, the Faroe Islands and the hebrides. DFS Inform. 2, 5–22.

Mazel, L. (1960). Structuring of the Music Works [CmpoeNIe MyZYKAlXNYx ppoIZWeDeNIJ], 2nd Edn. Moscow: Muzyka.

Mueller, T. F. (1973). “Heterophony,” in Encyclopedia of Music, Vol. 1, ed Y. Keldysh (Moscow: Soviet Encyclopedia), 1973–1976.

Nikolsky, A. (2016). Evolution of tonal organization in music optimizes neural mechanisms in symbolic encoding of perceptual reality. Part-2: Ancient to seventeenth century. Front. Psychol. 7:211. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00211

Rasch, R. A. (1988). “Timing and synchronization in ensemble performance,” in Generative Processes in Music; The Psychology of Performance, Improvisation, and Composition, ed J. A. Sloboda (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press), 70–90. Available online at: http://psycnet.apa.org/record/1988-98076-004

Seeger, A. (2004). Why Suyá Sing: A Musical Anthropology of an Amazonian People. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Stumpf, C. (1897). Die Pseudo-Aristotelischen Probleme Über Musik. Abhandlungen Der Königlichen Akademie Der Wissenschaften Zu Berlin, Vol. 3. Berlin: Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Stumpf, C. (1901). “Tonsystem und musik der siamesen,” in Beiträge Zur Akustik Und Musikwissenschaft, ed C. Stumpf (Leipzig: Veerlag von Johann Ambrosius Barth), 69–138.

Swan, A. J. (1943). The nature of the Russian folk-song. Music. Quart. 29, 498–516. doi: 10.1093/mq/XXIX.4.498

Keywords: texture, heterophony, polyphony, homophony, musilanguage, asynchrony, isophony, meter

Citation: Nikolsky A (2018) Commentary: The ‘Musilanguage’ Model of Language Evolution. Front. Psychol. 9:75. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00075

Received: 09 November 2017; Accepted: 18 January 2018;

Published: 26 February 2018.

Edited by:

Timothy L. Hubbard, Arizona State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Steven Brown, McMaster University, CanadaCopyright © 2018 Nikolsky. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aleksey Nikolsky, YWxla3NleUBicmFhdm8ub3Jn

Aleksey Nikolsky

Aleksey Nikolsky