- 1Faculty of Education, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 2Department of Psychology, Nipissing University, North Bay, ON, Canada

Many scholars have investigated the attitudes, beliefs, motives, and behavior of male clients of female sex workers. However, few have examined individual differences in major dimensions of personality expressed by men who purchase prostitution compared to those who do not. Although several evolutionary psychologists have studied prostitution and those involved in sex work, to our knowledge, none have explicitly considered the utility of an evolutionary personality perspective in trying to understand why particular men pay for sex. In the current mini-review, following other researchers, prostitution is described principally as a form of short-term mating sought primarily by men. We argue that the socially aversive traits embodying the Dark Tetrad (narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and sadism) may characterize certain male clients of female sex workers, particularly those consumers expressing the motives of desiring exciting and novel sex with women who are treated with contempt, perceiving prostitution in a business-like manner with little emotional involvement, and seeking to dominate and control sex workers who are viewed as vulnerable and subservient. The traits of the tetrad may also be more prevalent among men who purchase sex from female sex workers in outdoor (e.g., street prostitution) in comparison to indoor settings (e.g., escort agencies).

Introduction

Direct prostitution (e.g., street prostitution, escort services, and brothels) has been described as a form of sex work that involves an explicit exchange of material goods, favors, and/or services in return for sexual intimacy or erotic acts with no required commitment (Harcourt and Donovan, 2005). This is contrasted with indirect prostitution, wherein the exchange of money for sex may not be the main source of income (e.g., massage parlor workers), where purveyors do not refer to themselves as prostitutes (e.g., “camgirls,” adult film actors/actresses, and exotic dancers), or when people are forced into sex work out of necessity (e.g., survival sex). However, the terminology describing prostitution is a hotly contested matter among scholars (Benoit et al., 2018). Prostitution has been practiced across a myriad of different cultures since ancient times in sex-specific ways, whereby men have tended to be the primary consumers of sex work services offered by women and men (Dylewski and Prokop, 2019). Estimates of the percentage of men who purchase sex cross-culturally vary widely from 9 to 80% (discussed in Farley et al., 2011); however, several investigators have cautioned that previous estimates are likely inflated due to methodological issues (e.g., sampling bias), and that a more conservative estimate below 20% likely typifies men who have ever paid for sex (Månsson, 2004; Pan et al., 2011; Jewkes et al., 2012; Monto and Milrod, 2014; Ondrášek et al., 2018).

In the last decade, an increasing amount of scholarly work has been devoted to studying male clients of female sex workers (discussed in Milrod and Monto, 2017). Many researchers have studied the role of individual differences in attitudes, beliefs, motives, and behavior among men paying for direct and indirect forms of prostitution in comparison to those who do not pay for sex (Pitts et al., 2004; Monto and McRee, 2005; Farley et al., 2011, 2017; Monto and Milrod, 2014; Milrod and Monto, 2017). But few have directly assessed differences in major dimensions of personality (i.e., constellations of enduring individual differences in emotion, motivation, thoughts, and behavior) among those paying for prostitution (Wilson et al., 1992; Xantidis and McCabe, 2000; Sawyer et al., 2001). Several scholars have approached the topic of prostitution using the framework of evolutionary psychology (Burley and Symanski, 1981; Buss and Schmitt, 2001; Salmon, 2008; Prokop et al., 2018; Dylewski and Prokop, 2019). However, to our knowledge, none have explicitly considered the utility of an evolutionary personality perspective in studying male clients of prostitution, which is the focus of the current mini-review.

Personality, Mate Selection, and Mate Competition

Evolutionary psychologists have emphasized how personality dimensions influence both mate preferences (i.e., intersexual selection) and the ways in which people compete with rivals for mating opportunities (i.e., intrasexual competition; Jonason et al., 2012, 2015; Buunk et al., 2017; Buss and Schmitt, 2019). Because individual differences in personality impact fitness-relevant outcomes and show a high degree of inter-individual variability, heritability, and developmental stability, it is fruitful to consider their potential adaptive value (Nettle, 2006; Buss, 2009). From the perspective of life history theory, personality traits in human and non-human animals are argued to embody resource investment trade-offs (e.g., time, energy, and material assets) between the different components of fitness across the lifespan (e.g., survival, health, reproduction, and parenting) that are shaped by the social-ecological environment and consequently impact life history outcomes (e.g., age of sexual maturity; Figueredo et al., 2007; Wolf et al., 2007; Buss, 2009; Jonason et al., 2010; Simpson et al., 2017; Davis et al., 2019a,b). This life history framework has been applied to personality traits deemed to be socially desirable across cultures, such as honesty-humility (avoidance of manipulating others; Lee et al., 2013; Davis et al., 2019a), but also those dimensions of personality regarded as socially noxious, such as the interrelated traits that constitute the Dark Tetrad (Jonason et al., 2010; McDonald et al., 2012; Holtzman and Donnellan, 2015; Book et al., 2016; Davis et al., 2019b).

The Dark Tetrad and Short-Term Mating

The Dark Tetrad is a four-variable model of personality that is characterized by ego-centrism and grandiosity (i.e., narcissism), manipulative and cynical tendencies (i.e., Machiavellianism), callousness and antisociality (i.e., psychopathy), as well as taking enjoyment in the pain and suffering of others (i.e., sadism; Buckels et al., 2013; Book et al., 2016; Meere and Egan, 2017; Paulhus et al., 2018). From a life history perspective, investigators have argued that the Dark Tetrad dimensions appear to comprise an organized system of co-adapted traits that facilitate, to varying degrees, investment in early sexual development, short-term mating strategies, risk-taking, exploitation, and aggressive behavior; a so-called “fast life history strategy” (Lalumière et al., 2001; Gladden et al., 2009; Jonason et al., 2010; McDonald et al., 2012; Davis et al., 2019b). This is contrasted with personality traits, such as honesty-humility, that appear to be linked to a “slower life history strategy” whereby resources are invested in producing fewer offspring later on in development, heightened parental care, risk-aversion, as well as greater physical and psychosocial health (Davis et al., 2019a). However, researchers have cautioned that the application of life history theory to human personality has become fractioned from its theoretical origins in ecology and evolutionary biology (Nettle and Frankenhuis, 2019). The fast–slow continuum of life history has also been criticized by some who argue that these strategies do not operate on a single continuum (Holtzman and Senne, 2014). Scholars have further contended that the evolutionary processes that lead to differences between species in life history (Darwinian evolution) are not the same as those that lead to differences in psychological traits among members within a species (e.g., developmental plasticity; Zietsch and Sidari, 2019). Nonetheless, academics maintain that a life history framework is useful for understanding variability in personality traits in human and non-human animals (Wolf et al., 2007; Vonk et al., 2017; Davis et al., 2019b; Young et al., 2019; Del Giudice, 2020).

In previous research, the traits of the tetrad have been associated with, to varying degrees, an earlier sexual debut (Harris et al., 2007), a higher sex drive, impersonal sexual fantasies with multiple partners (Baughman et al., 2014), an unrestricted sociosexual orientation (i.e., a willingness and desire to have sex in the absence of love and commitment; Foster et al., 2006; Holtzman and Strube, 2013; Jones and de Roos, 2017; Tsoukas and March, 2018; Fernández del Río et al., 2019), a higher likelihood of committing infidelity (Jones and Weiser, 2014), and sexual risk-taking (Dubas et al., 2017) that collectively signal heightened investment in short-term mating. Individuals expressing higher levels of the Dark Tetrad personality dimensions are also more likely to engage in aggression (Paulhus et al., 2018), sexually coercion (Koscielska et al., 2019), and criminal behavior (e.g., vandalism, illegal substance use, and assault; Edwards et al., 2017; Pfattheicher et al., 2019). Deficits in affective empathy (i.e., a diminished capacity to feel the emotions of another) have also been linked to higher levels the Dark Tetrad traits (Jonason and Krause, 2013; Jonason et al., 2013; Sest and March, 2017; Heym et al., 2019). It has been argued that to feel empathy for another, it is necessary to perceive that others have minds like our own (i.e., mentalization). Failing to attribute minds to others can result in not seeing other people as fully human (i.e., dehumanization), which may facilitate interpersonal aggression and violence (Fiske, 2009; Farley et al., 2017). These dynamics may be especially apparent among those with elevated levels of Dark Tetrad traits (Bastian, 2019).

Prostitution, Short-Term Mating, and the Evolution of Economic Exchange

Evolutionary scholars have argued that prostitution qualifies a form of short-term mating because it tends to involve an explicit exchange of goods (e.g., money, jewelry, and/or drugs) for temporary and impersonal sexual intimacy (Burley and Symanski, 1981; Buss and Schmitt, 2001; Salmon, 2008; Meskó et al., 2014; Prokop et al., 2018; Dylewski and Prokop, 2019). Previous researchers have shown how several non-human animals exchange material resources for sexual opportunities and vice versa. Female purple-throated carib hummingbirds (Eulampis jugularis) trade sex for access to feeding sites that are vigilantly guarded by more dominant males (Wolf, 1975). Female Adélie penguins (Pygoscelis adeliae) engage in extra-pair copulations with unpaired males in exchange for stones that are required for nest construction (Hunter and Davis, 1998). Female chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) provide sex in return for calorie-rich meat from males that hunt (Gomes and Boesch, 2009). Although money is a human cultural artifact, brown capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) are capable of learning the validity of symbolic currency and may trade tokens for sex (Chen et al., 2006; Santos and Rosati, 2015; De Petrillo et al., 2019). These studies highlight how prostitution is not unique to humans and that monetary transactions can be understood from an evolutionary perspective.

Individual Differences Among Male Clients of Female Sex Workers

Cross-culturally, men who pay for sex report having more sexual partners than men who have never purchased sex (Pitts et al., 2004; Monto and McRee, 2005; Ward et al., 2005; Schei and Stigum, 2010; Ompad et al., 2013; Monto and Milrod, 2014; Farley et al., 2017). Male clients also tend to report an earlier sexual debut than non-clients (Schei and Stigum, 2010; Ompad et al., 2013; Rich et al., 2018) and display a preference for having sex with a variety of partners, as well less relational and committed sex (Xantidis and McCabe, 2000; Farley et al., 2017). Furthermore, male clients of prostitution express more permissive attitudes toward extramarital sex, they think about sex more frequently, report a higher frequency of masturbating (Monto and McRee, 2005; Monto and Milrod, 2014), and access pornography more often than men who do not pay for sex (Monto and McRee, 2005; Farley et al., 2012). Male clients have further been shown to engage in more sexual risk-taking and have a higher likelihood of acquiring and transmitting sexually transmitted illnesses than non-buyers (Ward et al., 2005; Schei and Stigum, 2010; Pan et al., 2011; Ompad et al., 2013; Rich et al., 2018; Seidu et al., 2019). Compared to men who have never bought sex, male clients also display less empathic accuracy (i.e., accurately inferring the thoughts and feelings of another) toward female sex workers than non-clients (Farley et al., 2011, 2017). Purchasing sex has also been associated with rape myth acceptance among men (Cotton et al., 2002), as well as the perpetration of intimate partner violence (Raj et al., 2008; Decker et al., 2009), sexually coercive behavior (Farley et al., 2011, 2017), and rape against non-prostituting women (Monto and McRee, 2005; Jewkes et al., 2006).

Across samples of arrested offenders and non-offenders from different cultures, a very consistent set of reasons regarding why men purchase sex from women have been identified (McKeganey, 1994; Xantidis and McCabe, 2000; Vanwesenbeeck, 2001; Cotton et al., 2002; Månsson, 2004, 2006; Pitts et al., 2004; Lowman and Atchison, 2006; Monto, 2010; Milrod and Monto, 2012, 2017; Farley et al., 2017; Ondrášek et al., 2018). However, caution should be exercised when trying to extrapolate findings from offenders to non-arrested male clients of sex work because these individual differ in important ways (e.g., in terms of demographic characteristics; Monto and McRee, 2005; Monto and Milrod, 2014), which may affect the degree to which they express certain motives for buying sex. These key general motives include: wanting novel, exciting, and forbidden sex with a variety of female sex workers who are treated with contempt to satisfy their sexual urges; seeking specific sexual acts that dating or romantic partners are unwilling or unlikely to provide; perceiving sex in a business-like manner without emotional involvement that is less complicated than dating and romantic relationships; a desire to dominate and control female sex workers who are perceived as vulnerable and subservient; and seeking comfort, companionship, love, and intimacy. The results described in this section support the idea that a majority of male clients of female sex workers express heightened short-term mating proclivities, but that the motives guiding a subgroup of men purchasing prostitution may actually signal long-term mating effort (e.g., wanting companionship).

Few researchers have directly assessed major dimensions of personality among male clients of female sex workers. In Zimbabwe, men who had previously been clients of prostitution reported higher levels of impulsivity, pleasure seeking, and ego-defensiveness (Wilson et al., 1992). Australian male clients of brothels purchasing services from female sex workers expressed higher levels of sensation-seeking (i.e., eagerness in seeking out novel and stimulating activities) than non-clients (Xantidis and McCabe, 2000). Xantidis and McCabe (2000) also found that male clients espousing motives in line with viewing sex as a business transaction, were significantly higher in sensation-seeking than customers seeking romance and companionship. American men who bought prostitution services reported heightened levels of hostile masculinity, which is argued to be a personality profile embodying hostility and cynicism toward women, and attitudes that justify aggression toward and the domination of women (Farley et al., 2017). Among American men arrested for prostitution, those who endorsed inaccurate beliefs about prostitution (e.g., “prostitutes make a lot of money”), scored higher on cynicism (misanthropy and interpersonal distrust) and antisocial practice (criminal behavior and lawlessness), and lower on self-esteem (Sawyer et al., 2001).

Personality, Prostitution, and the Dark Tetrad

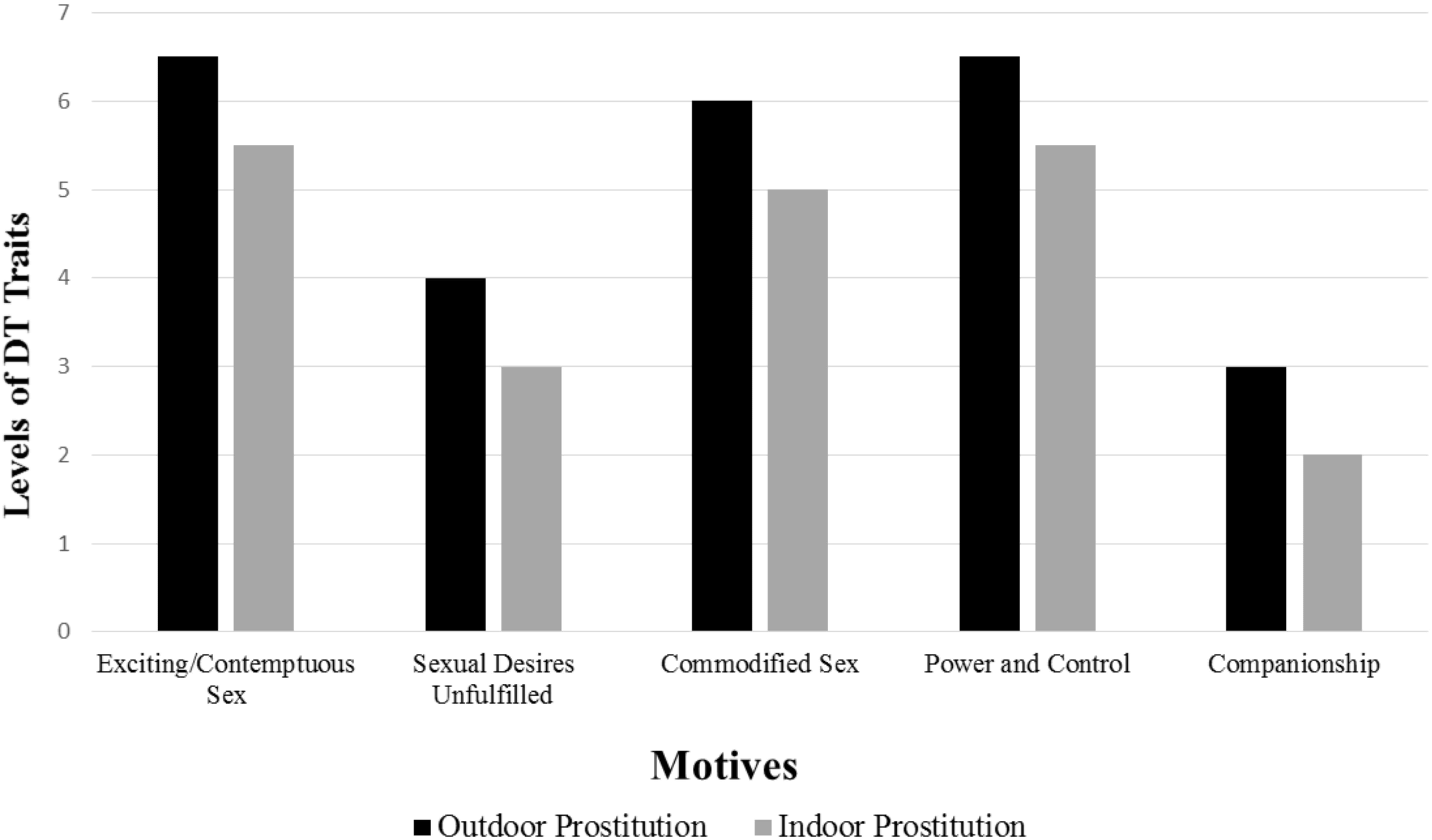

There are several lines of evidence discussed in the preceding sections that support the argument that the Dark Tetrad personality characteristics may be relevant in understanding why certain men pay for sex. Like many male clients of prostitution, individuals higher on the Dark Tetrad traits tend to express a penchant for short-term and impersonal sex (Holtzman and Strube, 2011, 2013; Jonason et al., 2012, 2015; Tsoukas and March, 2018; Fernández del Río et al., 2019), sexual risk-taking (Dubas et al., 2017), a desire for stimulation and novelty (Baumeister and Campbell, 1999; Carter et al., 2014), impulsivity (Jonason and Tost, 2010; Jones and Paulhus, 2011), greater rape myth acceptance (Jonason et al., 2017), lower emotional empathy (Jonason and Krause, 2013; Jonason et al., 2013; Sest and March, 2017; Heym et al., 2019), as well as the perpetration of interpersonal aggression, violence, and criminal behavior (Edwards et al., 2017; Paulhus et al., 2018; Pfattheicher et al., 2019). These findings also suggest that the Dark Tetrad may be especially prevalent among men expressing particular motives, including exciting and contemptuous sex with a variety of sex workers, commodified and business-like sex, and the desire to have power over and to control sex workers (see Figure 1 for predicted relations). Conversely, the traits of the tetrad may not as clearly typify men seeking sex workers for specific acts due to unfulfilled desires from their partners. The prevalence of the Dark Tetrad dimensions is likely even more diminished among men who buy sex for the purpose of companionship, intimacy, and love.

Figure 1. Dark Tetrad, Motives, and Type of Prostitution Service. Hypothetical expression of Dark Tetrad traits along a scale from 1 (low) to 7 (high) among male clients of female sex works by motive and type of prostitution service.

It is also possible that male clients of outdoor sex work (e.g., street prostitution) embody higher levels of the Dark Tetrad dimensions in comparison to men who purchase indoor services (e.g., escort services). This is because outdoor sex work is characterized by elevated risk, danger, illegal substance use, and the exploitation of women who are more often the targets of violence on behalf of clients (Lowman, 2000; Lowman and Atchison, 2006; Sanders, 2008; Milrod and Monto, 2012, 2017). Indeed, many men who seek female sex workers through internet sexual service providers for indoor prostitution report avoiding outdoor sex workers for these reasons (Milrod and Monto, 2017). Male clients of indoor sex work tend to be older and buy sex for the purpose of companionship, love, and intimacy in comparison to men who pay for outdoor prostitution services (Milrod and Monto, 2012, 2017).

It is important to consider evidence that could falsify the predictions delineated in the previous section. The personality trait of honesty-humility shares a negative association with each Dark Tetrad trait (Lee et al., 2013; Meere and Egan, 2017). Therefore, if honesty-humility is positively associated with the motives of exciting and contemptuous sex, commodified sex, or power and control, evidence would run counter to our predictions. Similarly, if men who buy sex in the form of outdoor prostitution express greater honesty-humility than clients who buy sex using indoor services, this would also contradict our proposition.

In future research, it will be important to examine major dimensions of personality, such as the Dark Tetrad traits, among clients, as well as the type of prostitution service they are accessing. Furthermore, many investigators do not assess whether men who have paid for sex have previously been arrested for solicitation of prostitution, which precludes an examination of this potentially confounding variable (Monto and McRee, 2005; Monto and Milrod, 2014). It is also important for researchers to consider the role of random responding when studying variables with values that are not centered around the middle of response scales, such as narcissism and psychopathy (Holtzman and Donnellan, 2017). Failure to take random responding into account for these kinds of variables can lead to inflated and biased effect size estimates, which can contribute to inaccurate inferences about statistical results.

Conclusion

In the current mini review, we argue that an evolutionary personality perspective can shed unique insight into the personality characteristics of male clients of female sex work. Given that men who display higher levels of socially deviant personality traits (e.g., the Dark Tetrad dimensions) tend to express a penchant for short-term mating, as well as heightened sensation-seeking, impulsivity, sexual risk taking, and criminality, it is likely that many clients of female sex workers possess similar personalities. These relations may be particularly apparent among male clients espousing specific motives (e.g., power and control), as well as those men who seek outdoor prostitution services. Nonetheless, there is a dearth of research on the personality characteristics that typify men who buy sex from those who do not. Empirical work on this topic is important because it can be used to better inform lawmakers, health professionals, and sex workers regarding the kinds of men who purchase sex, as well as the risks and dangers associated with involvement in particular kinds of prostitution.

Author Contributions

AD took the lead role in determining the focus of the submission, conducting the literature review, and writing the manuscript. TV and SA provided important guidance in helping to writing and editing the manuscript in preparation for submission. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Bastian, B. (2019). A dehumanization perspective on dependence in low-satisfaction (abusive) relationships. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 36, 1421–1440. doi: 10.1177/0265407519835978

Baughman, H. M., Jonason, P. K., Veselka, L., and Vernon, P. A. (2014). Four shades of sexual fantasies linked to the Dark Triad. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 67, 47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.034

Baumeister, R. F., and Campbell, W. K. (1999). The intrinsic appeal of evil: sadism, sensational thrills, and threatened egotism. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 3, 210–221. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_4

Benoit, C., Jansson, S. M., Smith, M., and Flagg, J. (2018). Prostitution stigma and its effect on the working conditions, personal lives, and health of sex workers. J. Sex Res. 55, 457–471. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1393652

Book, A., Visser, B. A., Blais, J., Hosker-Field, A., Methot-Jones, T., Gauthier, N. Y., et al. (2016). Unpacking more “evil”: what is at the core of the dark tetrad? Pers. Indiv. Differ. 90, 269–272. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.009

Buckels, E. E., Jones, D. N., and Paulhus, D. L. (2013). Behavioral confirmation of everyday sadism. Psychol. Sci. 24, 2201–2209. doi: 10.1177/0956797613490749

Burley, N., and Symanski, R. (1981). “Women without: an evolutionary and cross-cultural perspective on prostitution,” in The Immoral Landscape: Female Prostitution in Western Societies, ed. R. Symanski (New York, NY: Butterworths), 239–274.

Buss, D. M. (2009). How can evolutionary psychology successfully explain personality and individual differences? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 4, 359–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01138.x

Buss, D. M., and Schmitt, D. P. (2001). “Sexual strategies theory: an evolutionary perspective,” in Social Psychology and Human Sexuality: Essential Readings, ed. R. Baumeister (Hove: Psychology Press), 57–94.

Buss, D. M., and Schmitt, D. P. (2019). Mate preferences and their behavioral manifestations. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 70, 77–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103408

Buunk, A. P., Bucksath, A. F., and Cordero, S. (2017). Intrasexual competitiveness and personality traits: a study in Uruguay. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 108, 178–181. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.11.060

Carter, G. L., Campbell, A. C., and Muncer, S. (2014). The Dark Triad: beyond a ‘male’mating strategy. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 56, 159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.09.001

Chen, M. K., Lakshminarayanan, V., and Santos, L. R. (2006). How basic are behavioral biases? Evidence from capuchin monkey trading behavior. J. Polit. Econ. 114, 517–537. doi: 10.1086/503550

Cotton, A., Farley, M., and Baron, R. (2002). Attitudes toward prostitution and acceptance of rape myths. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 32, 1790–1796. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00259.x

Davis, A. C., Visser, B., Volk, A. A., Vaillancourt, T., and Arnocky, S. (2019a). Life history strategy and the HEXACO model of personality: a facet level examination. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 150:109471. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.06.014

Davis, A. C., Visser, B., Volk, A. A., Vaillancourt, T., and Arnocky, S. (2019b). The relations between life history strategy and dark personality traits among young adults. Evol. Psychol. Sci. 5, 166–177. doi: 10.1007/s40806-018-0175-3

De Petrillo, F., Caroli, M., Gori, E., Micucci, A., Gastaldi, S., Bourgeois-Gironde, S., et al. (2019). Evolutionary origins of money categorization and exchange: an experimental I nvestigation in tufted capuchin monkeys (Sapajus spp.). Anim. Cogn. 22, 169–186. doi: 10.1007/s10071-018-01233-2

Decker, M. R., Seage, G., Hemenway, D., Gupta, J., Raj, A., and Silverman, J. G. (2009). Intimate partner violence perpetration, standard and gendered STI/HIV risk behaviour, and STI/HIV diagnosis among a clinic-based sample of men. Sex. Trans. Infect. 85, 555–560. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.036368

Del Giudice, M. (2020). Rethinking the fast-slow continuum of individual differences. Evol. Hum. Behav. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2020.05.004

Dubas, J. S., Baams, L., Doornwaard, S. M., and van Aken, M. A. G. (2017). Dark personality traits and impulsivity among adolescents: differential links to problem behaviors and family relations. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 126, 877–889. doi: 10.1037/abn0000290

Dylewski, Ł., and Prokop, P. (2019). “History of prostitution,” in Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science, eds T. K. Shackelford and V. A. Weekes-Shackelford (Cham: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-16999-6_270-1

Edwards, B. G., Albertson, E., and Verona, E. (2017). Dark and vulnerable personality trait correlates of dimensions of criminal behavior among adult offenders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 126, 921–927. doi: 10.1037/abn0000281

Farley, M., Freed, W., Phal, K. S., and Golding, J. (2012). “A thorn in the heart: Cambodian men who buy sex,” Paper Presented at the Focus on Men Who Buy Sex: Discourage Men’s Demand for Prostitution, Stop Sex Trafficking Conference, Phnom Penh.

Farley, M., Golding, J. M., Matthews, E. S., Malamuth, N. M., and Jarrett, L. (2017). Comparing sex buyers with men who do not buy sex: new data on prostitution and trafficking. J. Interpers. Viol. 32, 3601–3625. doi: 10.1177/0886260515600874

Farley, M., Macleod, J., Anderson, L., and Golding, J. M. (2011). Attitudes and social characteristics of men who buy sex in Scotland. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 3, 369–383. doi: 10.1037/a0022645

Fernández del Río, E., Ramos-Villagrasa, P. J., Castro, Á, and Barrada, J. R. (2019). Sociosexuality and bright and dark personality: the prediction of behavior, attitude, and desire to engage in casual sex. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:2731. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16152731

Figueredo, A. J., Vásquez, G., Brumbach, B. H., and Schneider, S. M. (2007). The K-factor, covitality, and personality. Hum. Nat. 18, 47–73. doi: 10.1007/bf02820846

Fiske, S. T. (2009). From dehumanization and objectification, to rehumanization: neuroimaging studies on the building blocks of empathy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1167, 31–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04544.x

Foster, J. D., Shrira, I., and Campbell, W. K. (2006). Theoretical models of narcissism, sexuality, and relationship commitment. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 23, 367–386. doi: 10.1177/0265407506064204

Gladden, P. R., Figueredo, A. J., and Jacobs, W. J. (2009). Life history strategy, psychopathic attitudes, personality, and general intelligence. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 46, 270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.10.010

Gomes, C. M., and Boesch, C. (2009). Wild chimpanzees exchange meat for sex on a long-term basis. PloS One 4:e5116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005116

Harcourt, C., and Donovan, B. (2005). The many faces of sex work. Sex. Trans. Infect. 81, 201–206. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012468

Harris, G. T., Rice, M. E., Hilton, N. Z., Lalumiere, M. L., and Quinsey, V. L. (2007). Coercive and precocious sexuality as a fundamental aspect of psychopathy. J. Pers. Disord. 21, 1–27. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.1.1

Heym, N., Firth, J., Kibowski, F., Sumich, A., Egan, V., and Bloxsom, C. A. (2019). Empathy at the heart of darkness: empathy deficits that bind the Dark Triad and those that mediate indirect relational aggression. Front. Psychiatry 10:95. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00095

Holtzman, N. S., and Donnellan, M. B. (2015). “The roots of Narcissus: old and new models of the evolution of narcissism,” in Evolutionary Perspectives on Social Psychology, eds V. Zeigler-Hill, L. L. Welling, and T. K. Shackelford (Cham: Springer), 479–489. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-12697-5_36

Holtzman, N. S., and Donnellan, M. B. (2017). A simulator of the degree to which random responding leads to biases in the correlations between two individual differences. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 114, 187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.013

Holtzman, N. S., and Senne, A. L. (2014). Fast and slow sexual strategies are not opposites: implications for personality and psychopathology. Psychol. Inq. 25, 337–340. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2014.915708

Holtzman, N. S., and Strube, M. J. (2011). “The intertwined evolution of narcissism and short-term mating: an emerging hypothesis,” in The Handbook of Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder: Theoretical Approaches, Empirical Findings, and Treatments, eds W. K. Campbell and J. D. Miller (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc), 210–220. doi: 10.1002/9781118093108.ch19

Holtzman, N. S., and Strube, M. J. (2013). Above and beyond short-term mating, long-term mating is uniquely tied to human personality. Evol. Psychol. 11, 1101–1129. doi: 10.1177/147470491301100514

Hunter, F. M., and Davis, L. S. (1998). Female Adélie penguins acquire nest material from extrapair males after engaging in extrapair copulations. Auk 115, 526–528. doi: 10.2307/4089218

Jewkes, R., Dunkle, K., Koss, M. P., Levin, J. B., Nduna, M., Jama, N., et al. (2006). Rape perpetration by young, rural South African men: prevalence, patterns and risk factors. Soc. Sci. Med. 63, 2949–2961. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.027

Jewkes, R., Morrell, R., Sikweyiya, Y., Dunkle, K., and Penn-Kekana, L. (2012). Transactional relationships and sex with a woman in prostitution: prevalence and patterns in a representative sample of South African men. BMC Public Health 12:325. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-325

Jonason, P. K., Girgis, M., and Milne-Home, J. (2017). The exploitive mating strategy of the Dark Triad traits: tests of rape-enabling attitudes. Arch. Sex. Behav. 46, 697–706. doi: 10.1007/s10508-017-0937-1

Jonason, P. K., Koenig, B. L., and Tost, J. (2010). Living a fast life: the Dark Triad and life history theory. Hum. Nat. 21, 428–442. doi: 10.1007/s12110-010-9102-4

Jonason, P. K., and Krause, L. (2013). The emotional deficits associated with the Dark Triad traits: cognitive empathy, affective empathy, and alexithymia. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 55, 532–537. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.027

Jonason, P. K., Luevano, V. X., and Adams, H. M. (2012). How the Dark Triad traits predict relationship choices. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 53, 180–184. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.03.007

Jonason, P. K., Lyons, M., Bethell, E. J., and Ross, R. (2013). Different routes to limited empathy in the sexes: examining the links between the Dark Triad and empathy. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 54, 572–576. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.009

Jonason, P. K., Lyons, M., and Blanchard, A. (2015). Birds of a “bad” feather flock together: the Dark Triad and mate choice. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 78, 34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.01.018

Jonason, P. K., and Tost, J. (2010). I just cannot control myself: the Dark Triad and self- control. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 49, 611–615. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.031

Jones, D. N., and de Roos, M. S. (2017). Differential reproductive behavior patterns among the Dark Triad. Evol. Psychol. Sci. 3, 10–19. doi: 10.1007/s40806-016-0070-8

Jones, D. N., and Paulhus, D. L. (2011). The role of impulsivity in the Dark Triad of personality. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 51, 679–682. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.04.011

Jones, D. N., and Weiser, D. A. (2014). Differential infidelity patterns among the Dark Triad. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 57, 20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.09.007

Koscielska, R. W., Flowe, H. D., and Egan, V. (2019). The dark tetrad and mating effort’s influence on sexual coaxing and coercion across relationship types. J. Sex. Aggress. 1–11. doi: 10.1080/13552600.2019.1676925

Lalumière, M. L., Harris, G. T., and Rice, M. E. (2001). Psychopathy and developmental instability. Evol. Hum. Behav. 22, 75–92. doi: 10.1016/S1090-5138(00)00064-7

Lee, K., Ashton, M. C., Wiltshire, J., Bourdage, J. S., Visser, B. A., and Gallucci, A. (2013). Sex, power, and money: prediction from the Dark Triad and Honesty–Humility. Eur. J. Pers. 27, 169–184. doi: 10.1002/per.1860

Lowman, J. (2000). Violence and the outlaw status of (street) prostitution in Canada. Viol. Against Women 6, 987–1011. doi: 10.1177/10778010022182245

Lowman, J., and Atchison, C. (2006). Men who buy sex: a survey in the Greater Vancouver Regional District. Can. Rev. Sociol. 43, 281–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-618X.2006.tb02225.x

Månsson, S. A. (2004). Men’s Practices in Prostitution and Their Implications for Social Work. Available online at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.645.745 (accessed August 3, 2020).

Månsson, S. A. (2006). Men’s demand for prostitutes. Sexologies 15, 87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.sexol.2006.02.001

McDonald, M. M., Donnellan, M. B., and Navarrete, C. D. (2012). A life history approach to understanding the Dark Triad. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 52, 601–605. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.003

McKeganey, N. (1994). Why do men buy sex and what are their assessments of the HIV-related risks when they do? Aids Care 6, 289–301. doi: 10.1080/09540129408258641

Meere, M., and Egan, V. (2017). Everyday sadism, the Dark Triad, personality, and disgust sensitivity. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 112, 157–161. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.02.056

Meskó, N., Láng, A., and Bernáth, L. (2014). “Women evaluate their partners’ sexual infidelity: trade-off between disease avoidance and abandonment avoidance,” in Acta Szekszardiensium/Scientific Publications, Tom XVI, ed. É Farkas (Szekszárd: University of Pécs), 111–128.

Milrod, C., and Monto, M. (2017). Older male clients of female sex workers in the United States. Arch. Sex. Behav. 46, 1867–1876. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0733-3

Milrod, C., and Monto, M. A. (2012). The hobbyist and the girlfriend experience: behaviors and preferences of male customers of internet sexual service providers. Deviant Behav. 33, 792–810. doi: 10.1080/01639625.2012.707502

Monto, M. A. (2010). “Prostitutes’ customers: motives and misconceptions,” in Sex for Sale: Prostitution, Pornography, and The Sex Industry, ed. R. Weitzer (Abindon: Routledge), 233–254.

Monto, M. A., and McRee, N. (2005). A comparison of the male customers of female street prostitutes with national samples of men. Int. J. Offen. Ther. Comp. Criminol. 49, 505–529. doi: 10.1177/0306624X04272975

Monto, M. A., and Milrod, C. (2014). Ordinary or peculiar men? Comparing the customers of prostitutes with a nationally representative sample of men. Int. J. Offen. Ther. Comp. Criminol. 58, 802–820. doi: 10.1177/0306624X13480487

Nettle, D. (2006). The evolution of personality variation in humans and other animals. Am. Psychol. 61, 622–631. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.6.622

Nettle, D., and Frankenhuis, W. E. (2019). The evolution of life-history theory: a bibliometric analysis of an interdisciplinary research area. Proc. R. Soc. B 286:20190040. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.0040

Ompad, D. C., Bell, D. L., Amesty, S., Nyitray, A. G., Papenfuss, M., Lazcano-Ponce, E., et al. (2013). Men who purchase sex, who are they? An interurban comparison. J. Urban Health 90, 1166–1180. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9809-8

Ondrášek, S., Øimnáèová, Z., and Kajanová, A. (2018). “It’s also a kind of adrenalin competition”–selected aspects of the sex trade as viewed by clients. Hum. Affairs 28, 24–33. doi: 10.1515/humaff-2018-0003

Pan, S., Parish, W. L., and Huang, Y. (2011). Clients of female sex workers: a population-based survey of China. J. Infect. Dis. 204, S1211–S1217. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir537

Paulhus, D. L., Curtis, S. R., and Jones, D. N. (2018). Aggression as a trait: the Dark Tetrad alternative. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 19, 88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.007

Pfattheicher, S., Keller, J., and Knezevic, G. (2019). Destroying things for pleasure: on the relation of sadism and vandalism. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 140, 52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.03.049

Pitts, M. K., Smith, A. M., Grierson, J., O’Brien, M., and Misson, S. (2004). Who pays for sex and why? An analysis of social and motivational factors associated with male clients of sex workers. Arch. Sex. Behav. 33, 353–358. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000028888.48796.4f

Prokop, P., Dylewski, Ł, Woźna, J. T., and Tryjanowski, P. (2018). Cues of woman’s fertility predict prices for sex with prostitutes. Curr. Psychol. 39, 919–926. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9807-9

Raj, A., Reed, E., Welles, S. L., Santana, M. C., and Silverman, J. G. (2008). Intimate partner violence perpetration, risky sexual behavior, and STI/HIV diagnosis among heterosexual African American men. Am. J. Men’s Health 2, 291–295. doi: 10.1177/1557988308320269

Rich, R., Leventhal, A., Sheffer, R., and Mor, Z. (2018). Heterosexual men who purchase sex and attended an STI clinic in Israel: characteristics and sexual behavior. Israel J. Health Policy Res. 7:19. doi: 10.1186/s13584-018-0213-4

Salmon, C. A. (2008). “The world’s oldest profession: evolutionary insights into prostitution,” in Evolutionary Forensic Psychology: Darwinian Foundations of Crime and Law, eds J. Duntley and T. K. Shackelford (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 121–135. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195325188.003.0007

Sanders, T. (2008). Male sexual scripts: intimacy, sexuality and pleasure in the purchase of commercial sex. Sociology 42, 400–417. doi: 10.1177/0038038508088833

Santos, L. R., and Rosati, A. G. (2015). The evolutionary roots of human decision making. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66, 321–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015310

Sawyer, S., Metz, M. E., Hinds, J. D., and Brucker, R. A. (2001). Attitudes towards prostitution among males: a “consumers’ report”. Curr. Psychol. 20, 363–376. doi: 10.1007/s12144-001-1018-z

Schei, B., and Stigum, H. (2010). A study of men who pay for sex, based on the Norwegian national sex surveys. Scand. J. Public Health 38, 135–140. doi: 10.1177/1403494809352531

Seidu, A. A., Darteh, E. K. M., Kumi-Kyereme, A., Dickson, K. S., and Ahinkorah, B. O. (2019). Paid sex among men in sub-Saharan Africa: analysis of the demographic and health survey. SSM Popul. Health 11:100459. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100459

Sest, N., and March, E. (2017). Constructing the cyber-troll: psychopathy, sadism, and empathy. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 119, 69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.038

Simpson, J. A., Griskevicius, V., Szepsenwol, O., and Young, E. (2017). “An evolutionary life history perspective on personality and mating strategies,” in The Praeger Handbook of Personality Across Cultures: Evolutionary, Ecological, and Cultural Contexts of Personality, ed. A. T. Church (Westport: Praeger), 1–29.

Tsoukas, A., and March, E. (2018). Predicting short-and long-term mating orientations: the role of sex and the dark tetrad. J. Sex Res. 55, 1206–1218. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1420750

Vanwesenbeeck, I. (2001). Another decade of social scientific work on sex work: a review of research 1990–2000. Annu. Rev. Sex Res. 12, 242–289. doi: 10.1080/10532528.2001.10559799

Vonk, J., Weiss, A., and Kuczaj, S. A. (eds) (2017). Personality in Nonhuman Animals. New York, NY: Springer International Publishing.

Ward, H., Mercer, C. H., Wellings, K., Fenton, K., Erens, B., Copas, A., et al. (2005). Who pays for sex? An analysis of the increasing prevalence of female commercial sex contacts among men in Britain. Sex. Trans. Infect. 81, 467–471. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.014985

Wilson, D., Manual, A., and Lavelle, S. (1992). Personality characteristics of Zimbabwean men who visit prostitutes: implications for AIDS prevention programmes. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 13, 275–279. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(92)90102-U

Wolf, L. L. (1975). “Prostitution” behavior in a tropical hummingbird. Condor 77, 140–144. doi: 10.2307/1365783

Wolf, M., Van Doorn, G. S., Leimar, O., and Weissing, F. J. (2007). Life-history trade-offs favour the evolution of animal personalities. Nature 447, 581–584. doi: 10.1038/nature05835

Xantidis, L., and McCabe, M. P. (2000). Personality characteristics of male clients of female commercial sex workers in Australia. Arch. Sex. Behav. 29, 165–176. doi: 10.1023/A:1001907806062

Young, E. S., Simpson, J. A., Griskevicius, V., Huelsnitz, C. O., and Fleck, C. (2019). Childhood attachment and adult personality: a life history perspective. Self Ident. 18, 22–38. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2017.1353540

Keywords: prostitution, sex work, short-term mating strategies, personality, Dark Tetrad

Citation: Davis AC, Vaillancourt T and Arnocky S (2020) The Dark Tetrad and Male Clients of Female Sex Work. Front. Psychol. 11:577171. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577171

Received: 28 June 2020; Accepted: 18 August 2020;

Published: 17 September 2020.

Edited by:

Norbert Meskó, University of Pécs, HungaryReviewed by:

Kagan Kircaburun, Nottingham Trent University, United KingdomNicholas S. Holtzman, Georgia Southern University, United States

Copyright © 2020 Davis, Vaillancourt and Arnocky. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adam C. Davis, YWRhdmkxNTRAdW90dGF3YS5jYQ==

Adam C. Davis

Adam C. Davis Tracy Vaillancourt

Tracy Vaillancourt Steven Arnocky

Steven Arnocky