- 1African Studies Centre Leiden, Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands

- 2Department of Anthropology, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, United States

- 3The MARCS Institute for Brain, Behaviour and Development, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Music beats spoken language in identifying individuals uniquely in two disparate communities. In addition to their given names, which conform to the conventions of their languages, speakers of the Oyda (Omotic; SW Ethiopia) and Yopno (Finisterre-Huon; NE Papua New Guinea) languages have “name tunes,” short 1–4 s melodies that can be sung or whistled to hail or to identify for other purposes. Linguistic given names, for both communities, are often non-unique: people may be named after ancestors or contemporaries, or bear given names common to multiple individuals. But for both communities, name tunes are generally non-compositional and unique to individuals. This means that each new generation is likely to bring thousands of new name tunes into existence. In both communities, name tunes are produced in a range of contexts, from quotidian summoning and mid-range communication, to ceremonial occasions. In their use of melodies to directly represent individual people, the Oyda and Yopno name tune systems differ from surrogate speech systems elsewhere that either: (a) mimic linguistic forms, or (b) use music to represent a relatively small set of messages. Also, unlike some other musical surrogate speech traditions, the Oyda and Yopno name tune systems continue to be used productively, despite societal changes that have led to declining use in some domains.

Introduction

Philosophers have long distinguished proper names from common nouns on the basis of their semantics; in contrast to common nouns, which denote classes of things, proper names are said to denote individuals (Searle, 1958; Kripke, 1980). In this study, we describe musical practices from different sides of the world that share this property with names. Among the Oyda of Ethiopia and the Yopno of Papua New Guinea, a distinct musical tune is closely associated with each individual. In fact, these tunes are more uniquely associated with individuals than proper names are. In these communities, multiple individuals may share the same proper name, by virtue of being named after them, or by the name's popularity. What we term “name tunes,” in contrast, are unique to individuals, at least normatively.

Speech surrogate systems are often divided into two main types: abridgment and ideographic (Stern, 1957). In abridgment systems, musical features correlate with features of the affiliated language: pitch with tone or vowel quality, or duration with vowel length. This is typical of “whistled languages,” such as those corresponding to Spanish, Turkish, and Highland Mazateco (Cowan, 1948; Classe, 1957; Meyer, 2021), but abridgment systems in which musical instruments serve as proxies for speech are also attested (Niles, 2010). In ideographic systems, musical phrases are conventionally associated with words or expressions, bearing meaning without a phonic connection to the language. These are typified by some of the slit-gong drum messaging traditions of northern New Guinea (Burridge, 1959; Niles, 2010), and the “talking drums” of West Africa (Neeley, 1999; Winter, 2014).

The Oyda and Yopno name tune systems differ from both abridgment and ideographic systems in that the name tunes directly denote an individual, without recourse to language. That is, Oyda and Yopno name tunes reference individual human community members themselves; they are not “abridgments” or “ideographs” of people's given names. While there are minor stylistic differences between Oyda and Yopno name tunes, the two traditions are remarkably similar, and both are absent from most surrounding communities. This paper offers a first comparative analysis of the usage contexts and formal characteristics of Oyda and Yopno name tunes.

Comparing Oyda and Yopno Name Tune Traditions

Oyda Name Tunes: moyzé

The Oyda language of southern Ethiopia (about 45,000 speakers) belongs to the Ometo branch of Omotic. The Oyda region is dominated by mountains and valleys which are partly shaped by the Great Rift Valley system.

Most Oyda people have both a proper name and a moyzé “name tune.”1 Both men and women, as well as children from age five or six onward, use moyzé. While a proper name can simultaneously be used to designate different people, two or more living people cannot share the same moyzé. As such, moyzé are a more reliable personal identifier than a proper name.

Moyzé are typically whistled by blowing air between two fingers of a hand held against the mouth while the airstream is modified by the movement of fingers of the other hand (Amha in preparation). Some people blow air at a joint between their index-finger and middle finger, some between the middle finger and their ring-finger, still others between their ring-finger and little finger. This appears to have impact on the audibility of the whistle: air blown into the juncture between the index finger and the ring finger seems to have higher pitch, and is said by the Oyda to “reach farther,” than that between the index finger and ring finger. Another difference among people involves the hand someone habitually uses to blow air into. Some prefer to use the left hand for this while using the right hand for modulating air; others prefer the reverse. People claim that they can tell who is whistling their moyzé name based solely on the sound. According to one consultant: “The whistling of different people differs as their fingerprint would differ.”

An individual's moyzé is known and used by people close to him/her and is also introduced to new acquaintances. Such “teaching of moyzé” is done by singing the moyzé using consonant-vowel (CV) combinations, such as léeteléetetóom, for someone whose proper name is S'as'ima. Such sung “vocables” are not used to address people but are crucial for transmission of moyzé forms. Sung vocables can include any of the five vowels of the language: /i/, /u/, /e/, /o/, and /a/. Both short and long forms are attested. Consonants tend to be /m/, /n/, /l/, /w/, /h/, and /t/, but a few moyzé containing /b/ and /g/ are recorded, e.g., tóógirgidáalíiim.

Moyzé are most often used for communication at a distance, but also serve to invoke the memory of a deceased person. Moyzé are often used to summon or get the attention of family members at work in different places, to alert the addressee of some danger or emergency, and to greet someone when passing by his/her house. Until hunting was outlawed in the 1970s, moyzé were also widely used to assemble people for a hunting party. Among Oyda who still practice the traditional religion, moyzé play an important role in announcing death to family members in different villages and during funerals, where the moyzé name of the deceased is repeatedly called using a side-blown, trumpet-like instrument, also called moyzé, that is made from cattle horn. Indeed, it is possible that the term originally derived from moys- ‘to see off, accompany someone for part of the journey,' and that the original function of Oyda name tunes was funerary. With the expansion of Protestant and Pentecostal faiths among the Oyda, the use of moyzé in funeral contexts is eroding, but its use in daily communication has been maintained. In some cases, young people may be innovating new arenas in which to use moyzé; one young man uses his deceased father's moyzé as a mobile ring tone.

Moyzé may be given (e.g., by a parent to a child, a husband to his wife), may be self-created, or inherited. Adults can choose to keep an inherited moyzé of a deceased family member alongside their own moyzé, thereby having more than one moyzé for some time. Either their own moyzé or the inherited one can then be passed on to one of their own descendants.

Yopno Name Tunes: konggap

The Yopno language (Reed, 2000; Slotta, 2014) is spoken by some 8,000 people living in the Yopno valley in the northeast of Papua New Guinea. Yopno is a Papuan language of the Finisterre branch of the Finisterre-Huon language family. Yopno is most closely related to the Nankina and Domung languages to its north and west. Speakers of these three languages (total population: 15,000) all use name tunes, known in Yopno as konggap (Nankina: kunggwap). Konggap have been discussed by Niles (1992), Slotta (2012), and Ammann et al. (2013).

Konggap are most often sung using the vowels /a/, /o/, and /e/. Sung in this way, konggap can be heard at great distances across the deep gorges and along the steep mountain slopes found throughout the region. This is also the form in which konggap are performed at funerals and in ceremonial dances. But on a daily basis in the confines of homes, villages, and gardens, konggap may also be whistled, hummed or sung in the middle of spoken conversation.

Virtually everyone in the region has one of these melodies uniquely associated with him or her. The konggap are sung, whistled, and hummed throughout the day as people summon others, alert them to their presence, or even think about them. The Yopno language is non-tonal and konggap bear no phonic relation to people's proper names. Rather, each is a melodic and rhythmic sequence that identifies its bearer uniquely in a way that proper names do not, a point Yopno people routinely mentioned to the second author when discussing konggap. Traditional Yopno proper names are typically shared with living namesakes or ancestral forebears. Today, these names are often supplemented with names from English or Kâte, the former lingua franca of the Lutheran church in the region. But these too are drawn from a limited stock, so it is common for people to share a name with numerous others. In contrast, konggap are described as ideally unique to their bearer.

When still a baby, a child receives its first konggap, often composed by the mother while tending to the child. That konggap is later replaced by a new melody composed by a friend, relative, or often by the bearer him- or herself. The konggap of some is given by ancestors in dreams. Over their lives, people may cycle through multiple konggap, and even have more than one in use at the same time.

On a day-to-day basis, konggap are perhaps most often used to hail and summon, but, as with the funerary moyzé, they can also bespeak emotional associations with the people whose konggap are sung. Passing by a relative's house on the way to the forest, a man will sing his relative's konggap to alert him to his own passage. Seeing a friend at a distance along the steep mountain slopes in the region, a person will sing the friend's konggap as a greeting or summons. When one's thoughts turn to a person who has died or who one has not seen for a while, one expresses sorrow by singing or whistling the relative's konggap. Joy at the arrival of a friend is expressed with konggap. Shown a photo of the local preschool class by the second author, a group of children in Nian village burst into a mass of song—each singing out the konggap of a friend they recognized in the photo.

As with moyzé, konggap play a role in announcing death. Here, however, care must be taken, because singing a deceased person's konggap can also be taken as a sign that the singer is responsible for their death. At a funeral, where people gather around the body of the deceased for one or more days, women collectively sing the konggap of the deceased and of the relatives and friends of the deceased, sometimes cycling through dozens of konggap. The name tunes often elicit tears in the listening mourners.

Konggap are also sung in men's ceremonial dances (Niles, 1992; Ammann et al., 2013) to mark other moments of social importance—a new marriage, the conception of a first child, or an official event. A group of men sing their own individual konggap simultaneously, synchronizing the beginnings and endings of their very different konggap with a common beat. This is one of the few times a person sings his own konggap, which otherwise rings of great pretension. Indeed, an individual performer's konggap is said to potentially take on magical potency to seduce women in such performances.

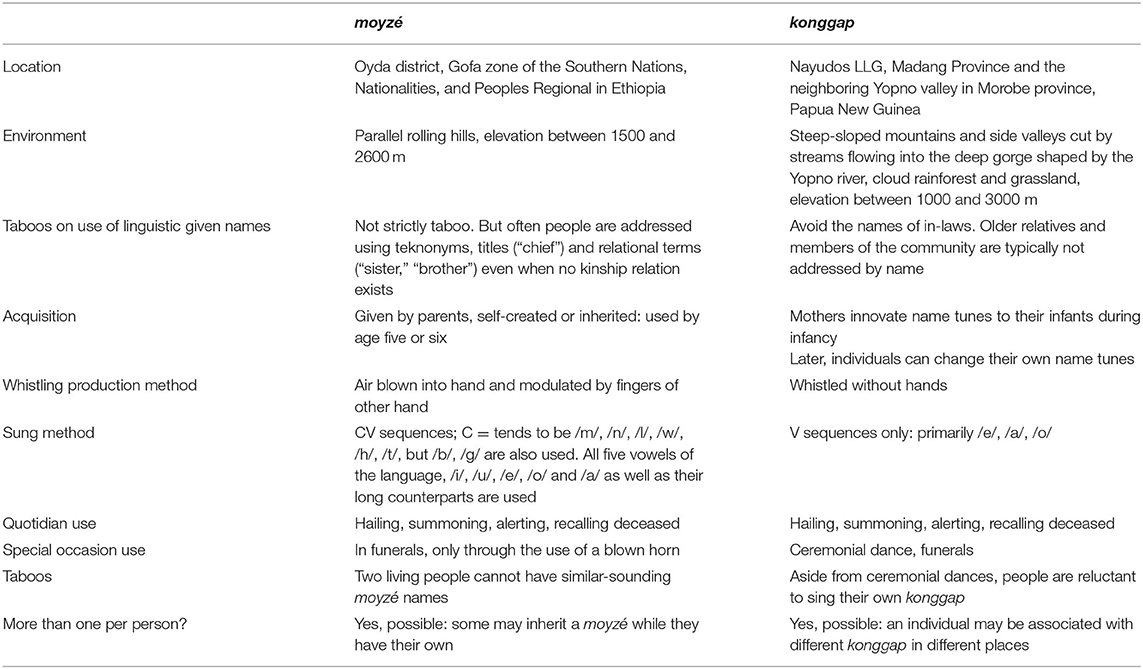

Table 1 compares key features of the konggap with those of the moyzé.

Formal Qualities

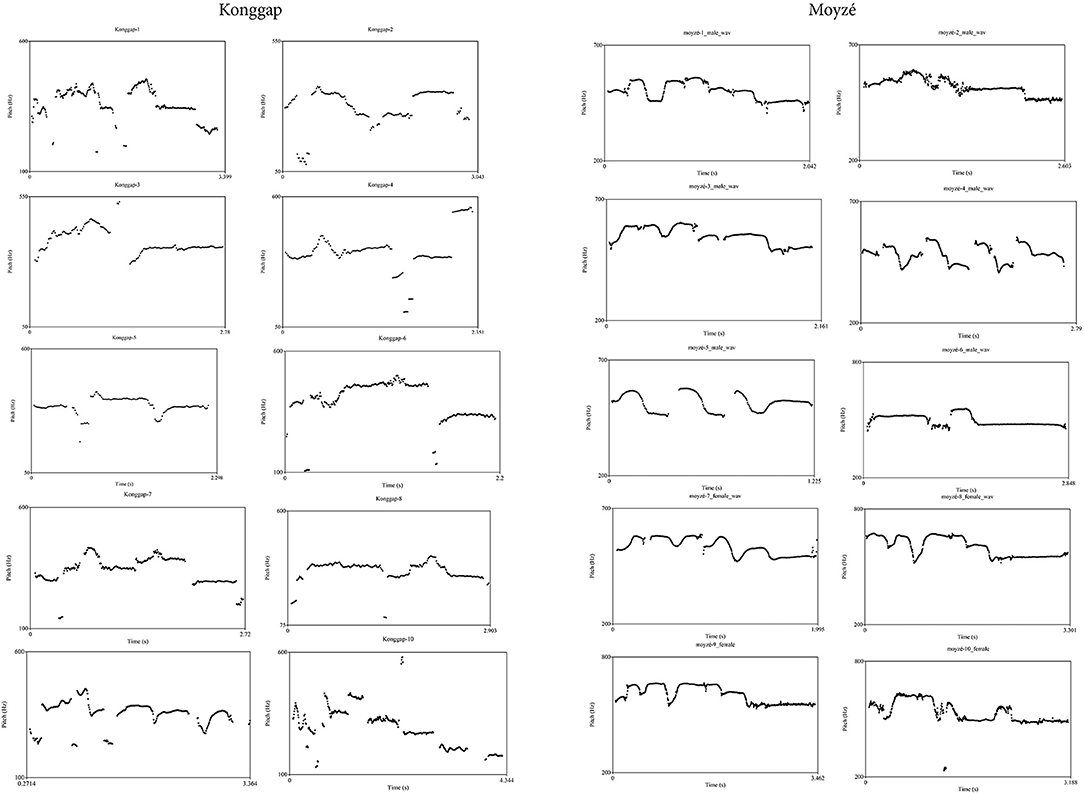

Figure 1 shows pitch traces for a sample of 10 sung konggap (left) and 10 whistled moyzé productions (right), analyzed using Praat (Boersma and Weenink, 2019). Time (in seconds) is charted on the x-axes, and pitch range (Hz.) is charted on the y-axes. The konggap were recorded using a Sony MZ-R55 minidisc recorder at the funeral for a deceased woman. In the recordings, a group of women sing the konggap of relatives of the deceased, using the vowels /a/, /e/, and /o/. The moyzé were recorded using a Linear PCM LS-11 audio recorder at 44.1 kHz/16bit. Six were performed by men and four by women.

Figure 1 shows that the name tunes of both traditions often end with relatively lower pitch than the rest of the tune, and the final “note” is often sustained. These pitch contours are not directly reminiscent of the prosodic contours of any linguistic units in either language. Due to the unstaged group singing and noisy, uncontrolled recording context of the konggap, brief, spurious pitch trace fragments appear, primarily in the lower frequencies. These were not used for measuring pitch ranges, below.

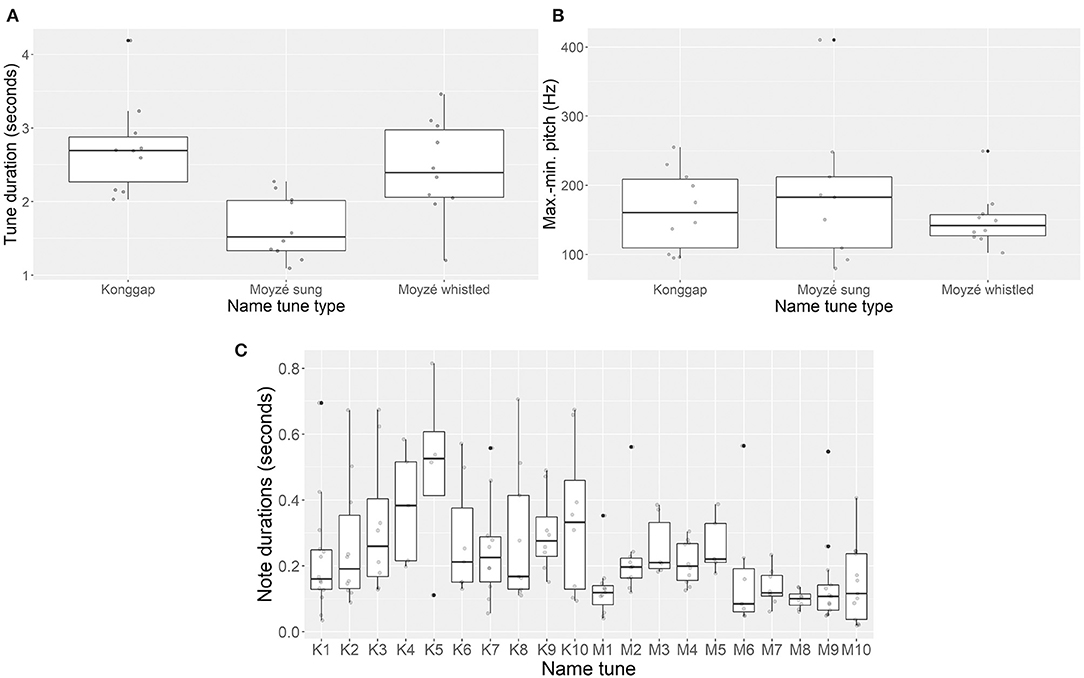

Figure 2 visualizes tune duration, pitch range, and note durations of the productions in Figure 1, along with sung renditions of the same moyzé. Figure 2A compares durations of the konggap with those of both sung and whistled moyzé. The sung konggap and whistled moyzé have similar average durations; the sung moyzé are shorter than all konggap, and most whistled moyzé. Figure 2B gives the results of subtracting the least pitch value from the greatest pitch value in each tune, based on actual sung notes, not any spurious pitch readings by Praat that appear in Figure 1. The konggap and sung moyzé are very similar here, while whistled renditions of the moyzé feature smaller pitch ranges, overall. Note that the graph depicts the difference between minimum and maximum pitch in each name tune, not the actual pitch values.

Figure 2. Tune duration, pitch range, and average note duration for sampled konggap and moyzé (K = konggap, M = moyzé).

Figure 2C aims to quantify the amount of rhythmic variation in each name tune. We segmented all “notes” in konggap and sung moyzé samples in Praat. A note was taken to be a sung vocoid or CV sequence with perceptually stable pitch; this was obtained by listening, along with visual inspection of the spectrogram. The number of notes per tune ranged from 4 to 14 (mean: 8.7; median: 8). Overall, there is more variation in note duration within individual konggap samples than within individual moyzé samples. Several moyzé are characterized by relatively even and short note durations (generally <0.4 s in duration), while all konggap include mixtures of short notes (lasting 0.2 s or less), and long notes (lasting 0.4 s or more).

In sum, konggap and moyzé are formally very similar. They last for similar amounts of time (1.09–4.19 s) and feature similar pitch ranges. Moyzé vary more in length than konggap, and konggap tend to have more internal rhythmic variation than the moyzé. Durations and pitch contours of both konggap and moyzé suggest that, if they should be compared with any linguistic units, this should be the utterance or clause (not the word, or proper name). Future research should compare the forms of konggap and moyzé to Yopno and Oyda musical genres: we expect that musical styles may reveal more than language about the origins of konggap and moyzé stylistic conventions.

Discussion

This has been the first comparative analysis of two name tune traditions. We have seen that in the Oyda and Yopno name tune traditions, a short musical sequence references an individual community member. These name tunes are maximally specific and individual; more so than proper names within each language, which can be identical in both communities to either ancestral figures' names or to living people's names. It appears that each new generation induces the generation of thousands of new moyzé and konggap name tunes. These name tune systems thus exemplify the human capacity for musical creativity, as well as for recognition and reproduction of musical sequences.

The Oyda moyzé and Yopno konggap are similar to each other in length and pitch range per tune, but diverge slightly in internal rhythmic variation (greater in the konggap). In both traditions, name tunes play an important role in funerary proceedings, evoking the essence of the deceased individual in a medium that could be said to speak directly to the emotions. The Yopno name tune tradition differs from the Oyda tradition in that konggap are also used in men's group song/dance performances.

Musical evocation of individuals is found beyond these two systems. The yoik of the Sami are short songs or chants that can be not only linked to individual people, but also to activities, animals, emotions, and nature (Anderson, 1984; Krumhansl et al., 2000: p. 19; Hanssen, 2011). At least two of the northern New Guinea communities with slit-gong drum messaging traditions (the Tangu and Reite) are also reported to have used particular drum sequences for each individual person—and sometimes individual domestic animals—in a community (Burridge, 1959; Leach, 2002).

In contrast, the Mehek, a Sepik area New Guinea community (Hatfield, 2016) have a small, apparently fixed inventory of isi “name whistles,” which, crucially, are each associated with a given name, not with individual people. Individuals who share a given name also share an isi. Some isi also map onto multiple given names; only 94 isi are attested. The tunes themselves are generally shorter and less complex than either konggap or moyzé. Mehek further has a few longer name “songs” for some given names, which appear to be slightly longer and more complex than either konggap or moyzé.

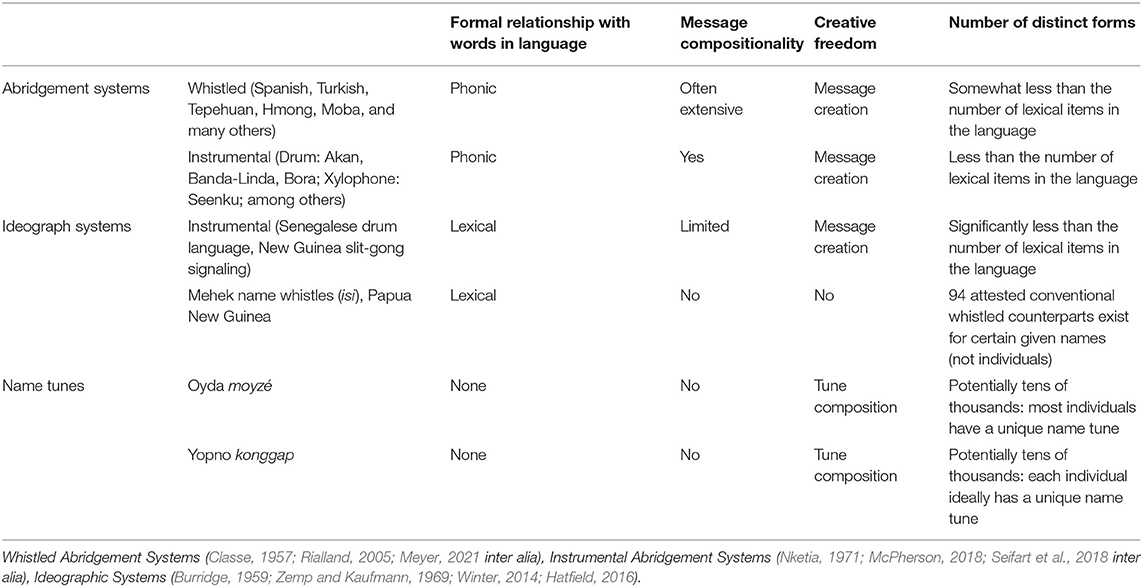

Table 2 compares features of these other traditions with those of the konggap and moyzé.

Mountainous environments may have played roles in the development of name tune systems among both the Oyda and the Yopno, as may be the case with surrogate speech systems—especially whistled ones—elsewhere (Meyer, 2021). Indeed, in both Oyda and Yopno, name tunes coexst with small inventories of whistled phrases (in Yopno, these may also be sounded on a conch shell horn) with meanings like “yes,” “come,” and “go”: these do correspond to the Oyda and Yopno languages through abridgment, just like other whistled languages around the world. Another factor in the development of these name tunes systems may be taboos on pronouncing certain proper names: in both communities, people avoid using some proper names, in either strict taboos on speaking in-laws' names (Yopno) or milder social preferences to address and reference using kin terms (Oyda). But such preferences are far from unique to these communities (Fleming, 2011). The fact remains that neighboring communities to the Oyda and Yopno, who live in similar terrains and have similar cultural practices, lack name tune traditions entirely.

The next populated area due east from the Yopno area is the Uruwa region. Although Uruwa people use no name tunes, just one of the 10 Uruwa villages uses birth-order terms (small sets of names that denote a person's sex and birth-order) to hail and refer to individuals, while the other villages do not (Sarvasy, 2013, 2017). Perhaps naming systems—musical or linguistic–lend themselves to clean breaks with neighboring groups, unlike other aspects of language and culture, which are more likely to evince clines.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://dobes.mpi.nl/projects/oyda/language/.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Volkswagen Stiftung for the DoBeS project on Oyda; University of Chicago Institutional Review Board, University of Chicago. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

AA contributed to Oyda name tune data and analysis. JS contributed to Yopno name tune data and analysis. HSS contributed to formal analysis. All authors contributed to writing.

Funding

Grant from the DoBeS programme of Volkswagen Stiftung II/84 327 to AA. Fulbright-Hayes Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Grant, Wenner-Gren Dissertation Fieldwork Grant, Endangered Languages Documentation Programme Individual Postdoctoral Fellowship to JS. Grant from the Australian Research Council DE180101609 to HSS.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

AA wishes to thank the Oyda speakers who provided information on moyzé and her host family: Ato Tegegne Taddese and his wife w/o Birtukan. JS is grateful to his hosts in Nian, Weskokop, Gua, and Ganngalut villages, and to everyone in the Yopno valley who supported his research. Thanks also to Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald and Roger Dean for helpful comments.

Footnotes

References

Ammann, R., Keck, V., and Wassmann, J. (2013). The sound of a person: a music-cognitive study in the Finisterre Range in Papua New Guinea. Oceania 83, 63–87. doi: 10.1002/ocea.5012

Boersma, P., and Weenink, D. (2019). Praat (Version 6.1.03) [Software]. Available online at: www.praat.org (accessed July 25, 2021).

Burridge, K. O. L. (1959). The slit-gong in Tangu, New Guinea. Ethnos 24, 136–150. doi: 10.1080/00141844.1959.9980869

Classe, A. (1957). The whistled language of la gomera. Sci. Am. 196, 111–124. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0457-111

Fleming, L. (2011). Name taboos and rigid performativity. Anthropol. Q. 84, 141–164. doi: 10.1353/anq.2011.0010

Hanssen, I. (2011). A song of identity: Yoik as example of the importance of symbolic cultural expression in intercultural communication/health care. J. Intercult. Commun. 27. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01021.x

Hatfield, A. (2016). A Grammar of Mehek [Ph.D. dissertation]. State University of New York, Buffalo, NY, Unites State. Available online at: http://www.acsu.buffalo.edu/~dryer/hatfield_mehek2016.pdf (accessed July 25, 2021).

Krumhansl, C. L., Toivanen, P., Eerola, T., Toiviainen, P., Järvinen, T., and Louhivuori, J. (2000). Cross-cultural music cognition: cognitive methodology applied to North Sami yoiks. Cognition 76, 13–58. doi: 10.1016/S0010-0277(00)00068-8

Leach, J. (2002). Drum and voice: aesthetics and social process on the rai coast of papua new guinea. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 8, 713–734. doi: 10.1111/1467-9655.00130

McPherson, L. (2018). Grammatical principles and documentary implications. Anthropol. Linguist. 60, 255–294. doi: 10.1353/anl.2019.0006

Meyer, J. (2021). Environmental and linguistic typology of whistled languages. Annu. Rev. Linguist. 7, 493–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011619-030444

Niles, D. (1992). “Konggap, kap and tambaran: music of the Yopno/Nankina area in relation to neighbouring groups,” in Abschied von der Vergangenheit. Ethnologische Berichte aus dem Finisterre-Gebirge in Papua New Guinea, ed J. Wassmann (Berlin: Reimer), 149–183.

Niles, D. (2010). Editor's Introduction to Zemp and Kaufmann (1969). Kulele 4. Boroko: Institute for Papua New Guinea Studies, 1–50.

Nketia, J. H. K. (1971). “Surrogate languages of Africa,” in Current Trends in Linguistics: Linguistics in Sub-Saharan Africa, Vol. VII, ed T. A. Sebeok (Berlin: Mouton), 699–732.

Rialland, A. (2005). Phonological and phonetic aspects of whistled languages. Phonology 22, 237–271. doi: 10.1017/S0952675705000552

Sarvasy, H. (2013). Across the great divide: how birth-order terms scaled the Saruwaged Mountains in Papua New Guinea. Anthropol. Linguist. 55, 234–255. doi: 10.1353/anl.2013.0012

Seifart, F., Meyer, J., Grawunder, S., and Dentel, L. (2018). Reducing language to rhythm: Amazonian Bora drummed language exploits speech rhythm for long-distance communication. R. Soc. Open Sci. 5:170354. doi: 10.1098/rsos.170354

Slotta, J. (2012). On the Receiving End: Cultural Frames for Communicative Acts in Postcolonial Papua New Guinea (Ph.D. thesis). The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States.

Slotta, J. (2014). Documenting Yopno Diversity: Dialect Variation in a Papuan Language. London: SOAS, Endangered Languages Archive. Available online at: https://elar.soas.ac.uk/Collection/MPI43302 (accessed July 25, 2021).

Stern, T. (1957). Drum and whistle languages: an analysis of speech surrogates. Amer Anthropol. 59, 487–506. doi: 10.1525/aa.1957.59.3.02a00070

Winter, Y. (2014). On the Grammar of a Senegalese Drum Language. Language 90, 644–668. doi: 10.1353/lan.2014.0061

Keywords: Oyda, Yopno, surrogate speech, name tune, konggap, moyzé, music, whistled language

Citation: Amha A, Slotta J and Sarvasy HS (2021) Singing the Individual: Name Tunes in Oyda and Yopno. Front. Psychol. 12:667599. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.667599

Received: 13 February 2021; Accepted: 15 July 2021;

Published: 11 August 2021.

Edited by:

Yoad Winter, Utrecht University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Don Niles, Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies, Papua New GuineaGerrit Bloothooft, Utrecht University, Netherlands

Copyright © 2021 Amha, Slotta and Sarvasy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Azeb Amha, YS5hbWhhQGFzYy5sZWlkZW51bml2Lm5s

Azeb Amha

Azeb Amha James Slotta

James Slotta Hannah S. Sarvasy

Hannah S. Sarvasy