- 1Faculty of Psychology, eCampus University, Novedrate, Como, Italy

- 2Department of Education, Psychology and Communication, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy

Introduction: The empirical study about the negative impact of economic difficulties due to Covid- 19 on the psychological well-being of Italian women by considering perceived stress and marital satisfaction is an area worthy of investigation. The study explored these variables by hypothesizing that marital satisfaction (DAS) could moderate or mediate the links between economic difficulties, perceived stress (PSS), and psychological maladjustment (PGWBI).

Methods: A total of 320 Italian women completed an online survey about the study’s variables during the lockdown period. Women’s perceptions of economic difficulties due to COVID- 19 restrictions were detected through an ad-hoc specific question. Perceived stress, marital satisfaction and psychological maladjustment were assessed by standardized questionnaires (Perceived Stress Scale 10, Dyadic Satisfaction Scale and Psychological General Well-being Inventory).

Results: 39.7% of women who answered the online survey said that the Covid-19 significantly impacted their family income. Results indicated that marital satisfaction did not moderate the associations investigated. Conversely, data showed how economic difficulties (X) predicted lower psychological maladjustment through the mediation of perceived Stress (M1), which, in turn, was associated with higher levels of marital dissatisfaction (M2).

Conclusion: The results of the present study confirm the significant role of marital dissatisfaction in explaining the indirect effects of economic difficulties on psychological maladjustment in women. In particular, they indicated a significant spillover effect which transmitted strains experienced in one domain (economic difficulties) to another (the dissatisfaction of the couple), which in turn affected the psychological maladjustment.

Introduction

The lockdowns imposed because of the COVID-19 pandemic in European Countries and overseas impacted people at different levels, with consequences on the psychological well-being of the people involved as well as implications for their income (Brooks et al., 2020; International Labour Organization, 2020). Confining lockdown measures, including self-isolation, and the suspension of superfluous activities, led to a consequent reduction in work hours, income loss, and job loss for many workers (Crayne, 2020; Hensher, 2020; Matthews et al., 2021; McDowell et al., 2021). The economic difficulties and the worries and uncertainty of the future led to a condition of financial strain - the subjective stress about financial concerns – which impacted many individuals and families (Friedline et al., 2021; Hertz-Palmor et al., 2021). Several surveys undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic showed that unemployment, economic difficulties, and financial strain predicted higher levels of psychological distress and mental health disorders (Achdut and Refaeli, 2020; Kelley et al., 2020; Armour et al., 2021). More specifically, both loss of job/income (objective financial hardship) and perceptions of financial strain (the subjective feeling of economic well-being) were related to psychological maladjustment in terms of anxiety and depressive symptoms (Hertz-Palmor et al., 2021). Some authors (Ruengorn et al., 2021; Trógolo et al., 2022) suggested that the subjective perceptions of financial strain had more damaging effects on mental health (particularly on anxiety, depression, and perceived stress) than objective economic indicators (i.e., income or job loss). Conversely, other scholars suggested that objective financial hardship, such as job loss, unemployment, and lower income or loss of income, during the pandemic led to more psychological distress and depressive symptoms (Crayne, 2020; Pierce et al., 2020; van der Velden et al., 2020). Specifically, some European studies (Pierce et al., 2020; van der Velden et al., 2020) showed that, during the pandemic, people who lost their job, were unemployed, or had no income were more distressed than individuals who were employed or already unemployed before COVID-19. Similarly, other studies from the U.S. demonstrated that low income, lack of savings, and unemployment were risk factors for depression during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with pre-pandemic (Ettman et al., 2020; Fitzpatrick et al., 2020; Twenge and Joiner, 2020).

These findings outlined the associations between the COVID-19 related decrease in financial security and the deterioration in mental health. Indeed, individuals with higher economic difficulties and financial strain could perceive more psychological distress, which in turn promoted the onset of anxiety, depression, and a series of other mental health problems (Wilson et al., 2020; Witteveen and Velthorst, 2020; Hertz-Palmor et al., 2021). Specifically, some studies demonstrated that psychological distress due to financial strain led to the onset of anxious and depressive feelings or the exacerbation of depression (Wilson et al., 2020; Witteveen and Velthorst, 2020; Hertz-Palmor et al., 2021).

During the pandemic, economic difficulties and financial strain also harmed couple relationships by promoting greater dissatisfaction with marriage and lower relationship commitment, resulting in more frequent conflicts (see Epifani et al., 2021 for a review). For example, Balzarini et al. (2020) showed how economic difficulties, perceived stress, and confining lockdown measures were negatively associated with the couple’s relationship quality. In a recent meta-analysis, Falconier and Jackson (2020) indicated how economic strain impacted the quality of the couple’s relationship functioning, independently from sociodemographic factors, study design, or sample type.

The impact of financial stress on the quality of the couple’s relationships and psychological well-being has already been pointed out in the past literature (Kelley et al., 2022). Several studies showed how objective financial stressors, such as unstable income and perceived financial stress, predicted lower levels of marital satisfaction (Gudmunson et al., 2007; Archuleta et al., 2011; Stewart et al., 2017) and an increase in marital conflicts and marital dissolution (Dew et al., 2012). To explain the association between external stress (such as economic difficulties) and marital satisfaction, literature introduced the notion of “spillover effect.” The spillover effect refers to a situation when stress felt in one domain (e.g., work or couple) is transmitted to another domain (e.g., family/parenting behaviors) and negatively impacts the well-being of individuals in their other roles (Kouros et al., 2014). Many studies (e.g., Frone, 2003; Ilies et al., 2007; Kouros et al., 2014) have found that job stressors can spill over to the family domain and increase partner distress and marital dissatisfaction. More specifically, according to Pietromonaco and Overall (2020), unemployment, economic strain, and work difficulties could spill over and negatively impact the quality of the couples’ relationship by creating a context in which partners are distracted, fatigued, or overwhelmed. As a result, the partners could become conflictual and critical, give less support, and become less happy with their romantic relationship.

Moreover, literature indicated how deteriorated marital relationships could be a link between economic difficulties and psychological maladjustment. For example, Romeo et al. (2022) suggested that people who indicated a negative impact of COVID-19 on their family income reported a deteriorated couple relationships and higher levels of internalizing symptoms and post-traumatic symptoms.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the study of Pieh et al. (2020, 2021) showed how the couple’s relationship quality was related to mental health and well-being. They found that good relationship quality predicted higher levels of psychological well-being and mental health.

The protective role of a good marital relationship on mental health was also outlined in several previous studies (Horwitz et al., 1996; Simon, 2002; Williams, 2003; Thoits, 2011) that showed how, according to the stress-buffering model (Cohen and Wills, 1985), significant others may buffer the harmful effects of stressful events on mental health through providing emotional support and active coping assistance. Indeed, if individuals receive emotional support from their significant others, in case of external stressors, they will be more effective in mobilizing their resources and become less prone to suffer from psychological maladjustment (Jesus et al., 2016; Viseu et al., 2018).

With specific reference to the negative impact of economic difficulties on mental health, some researchers (Conger et al., 1999; Lincoln and Chae, 2010) indicated that a good marital relationship might protect against economic hardship and reduce some negative affect that frequently accompanies economic pressure. More specifically, Lincoln and Chae (2010) investigated whether marital satisfaction moderates the influence of economic difficulties on psychological distress among African Americans. Results showed how marital satisfaction had a protective role in moderating the negative effects of financial difficulties on psychological distress. Moreover, Viseu et al. (2018) assessed the association between economic difficulties and the symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression by testing the moderating effect of informational, practical, and emotional support from significant others on these associations. Results showed the moderating effects of support from significant others regarding the association between economic stress and mental health. Similarly, another recent study (Chai, 2023) investigated the association between economic difficulties and psychological distress by exploring how this link could be mediated by sleep problems and moderated by marital status (a moderated mediation model). Results showed that economic problems predicted psychological distress through the partial mediation of sleep problems. Moreover, marital status moderated the associations between economic problems and psychological distress and between sleep difficulties and psychological distress.

Considering the above-cited literature, we were interested in exploring a line of research that is almost blank and rife with potential for exploration. Specifically, we decided to investigate the predictive role of economic difficulties on psychological maladjustment in Italian women by focusing on marital satisfaction as both a potential protective factor (moderator) or explicative mechanism of this association (mediator).

The present study had two aims. The first one is to explore the role of marital satisfaction in moderating the indirect effects of economic difficulties on women’s psychological maladjustment through the mediation of perceived stress. According to the literature (Lincoln and Chae, 2010; Chai, 2023), we supposed that marital satisfaction could exert a protective role by reducing the negative impact of economic difficulties and perceived stress on women’s psychological adjustment.

The second aim is to explore the potential spillover effect from economic difficulties to women’s psychological maladjustment by considering the serial mediation of perceived stress and marital dissatisfaction. In other words, based on the literature (Epifani et al., 2021; Friedline et al., 2021; Hertz-Palmor et al., 2021), we hypothesized that economic difficulties during the Covid-19 outbreak could predict the onset of higher levels of perceived stress which, in turn, negatively affects the couple’s relationship with consequences for psychological adjustment.

The focus is on women because research (Reizer et al., 2020) has shown that they were more prone than men to stress and psychological adjustment problems during the COVID-19 period. Specifically, women reported higher levels of internalizing symptoms, depression, anxiety, and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic in China (Wang et al., 2020) and in 25 European countries (Gamonal-Limcaoco et al., 2020).

Methods

Procedure

A web-based survey was created on the Qualtrics Platform and spread through different social media sites (the survey link was posted on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram, with a snowball sampling via WhatsApp) from April 2020 to July 2020. The survey was directed to married or cohabiting women, who were asked to answer some questions about sociodemographic characteristics and to fill out some questionnaires about the study’s variables during the lockdown period.

Participation in the survey was voluntary, and women had to give their informed consent to participate as well as to data treatment before starting to answer the questions. The survey took approximately 20 min to be completed. In the treatment of the participants, we have followed APA guidelines and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Participants

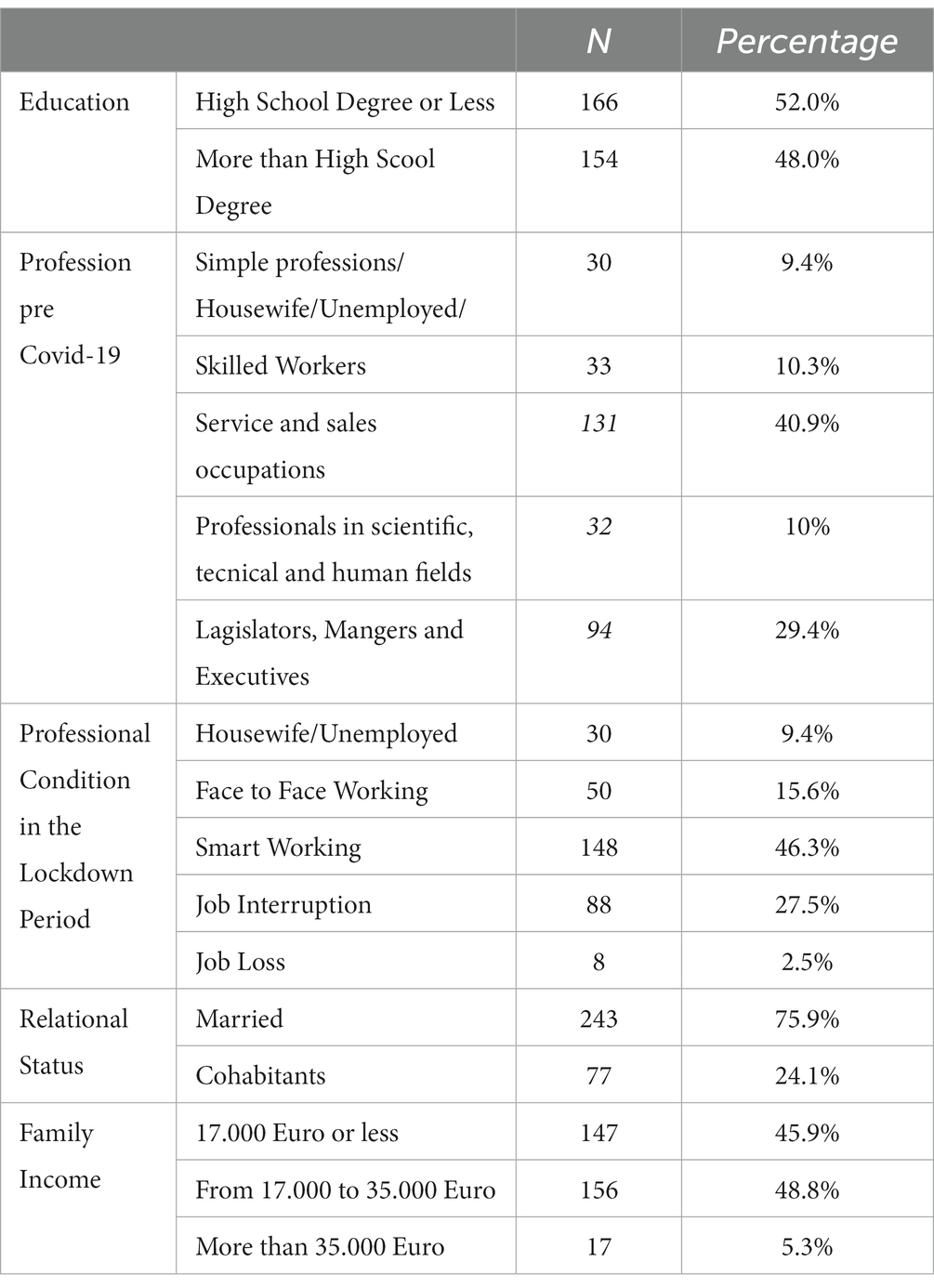

For the survey (which addressed married or cohabitant women with children), 320 Italian women aged between 30 and 58 years old (M = 42.48; DS = 6.0) agreed to participate and provided data. A summary of the participant’s demographic characteristics is displayed in Table 1. In short, a significant number of women were married (76%; duration of marriage or cohabitation: M = 13.0; DS = 7.8), well educated (48% with more than a high school degree), and with a total family income ranging from 17.000 to 35.000 euro (49%).

Measures

Economic difficulties

Women’s perceptions of Economic Difficulties due to COVID-19 restrictions were detected through an ad-hoc specific question: “Did the restrictive measures due to the Covid-19 emergency negatively impact your family income, with a consequent condition of concern, tension, and stress?.” The answers were dichotomously coded as “Yes” =1; or “Not” = 0. We used a dichotomous response as we are primarily interested in detecting the appraisal of the presence/absence of a negative economic impact of Covid-19. 39.7% of the sample indicated that the restrictive measures negatively impacted their family income.

Perceived stress

The women’s perceived stress was assessed with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10). The PSS-10 (Cohen et al., 1983; 1988; Italian version Fossati, 2010) is a self-report measure consisting of 10 items aimed to measure self-reported stress in terms of “How unpredictable, uncontrollable, and over-loaded respondents find their lives.” Participants are asked to answer each question on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). The PSS-10 total score ranges from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived stress. In this study, the value of the internal consistency of the measure was found to be high for the Perceived Stress Scale (α = 0.84).

Marital satisfaction

The women’s marital satisfaction was measured with the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Spanier, 1976); Italian validation by Gentili et al. (2002). The DAS is a measure that assesses the quality of marital adjustment, and it has four subscales: (1) Dyadic Consensus (13 items), (2) Dyadic Satisfaction (10 items), (3) Affective Expression (4 items), and (4) Dyadic Cohesion (5 items). In the present study, due to the survey length, we administered only the Dyadic Satisfaction items to gain information about the level of women’s marital satisfaction (in terms of positive interactions or conflicts and thoughts of separation/divorce). In the study of the Italian validation of the DAS (Gentili et al., 2002), the internal consistency value for Marital Satisfaction was: α = 0.87, in this sample, the internal consistency of this Scale was also high (α = 0.81).

Psychological maladjustment

The participant’s psychological maladjustment was assessed using the Psychological General Well-being Inventory (PGWB; Dupuy, 1984). We used the Italian Short Version of the measure (Grossi et al., 2006), which is composed of six items that refer to these sub-scales: positive well-being, self-control, general health, vitality, anxiety, and depression. Higher scores show better psychological adjustment. In our sample, the internal consistency of the Total Score was high: α = 0.86.

Data analysis

Point-serial correlations were used to investigate the associations between the variables.

Measures of central tendency (mean or median and absolute and relative frequencies) and dispersion (standard or interquartile deviation) were first computed to describe the sample. Descriptive statistics such as Skewness, Kurtosis, and boxplot were also used to inspect data distributions and to find outliers.

A Point-biserial correlation matrix was computed to investigate the associations between the predictor economic difficulties (a categorical variable) and the other variables of the study. Path analyses were performed to test the hypothesized relationships within a moderated mediation model and a serial mediation model. We used the Process Macro for SPSS (Hayes and Preacher, 2013) with Model 59 for the moderated mediation model and with Model 6 for the serial mediation model, which was estimated with a bias-corrected bootstrap sampling method (5,000 samples) because it is particularly suitable for small samples (Hayes, 2012). “A value of p of 0.05 was set as the critical level for statistical significance (for the analysis of indirect effects, if the 95% confidence interval includes 0, then the indirect effect is not significant at the 0.05 level, while if the interval does not include 0, is not in the interval then the indirect effect is statistically significant at the 0.05 level” (Hayes, 2013, p. 633).

The first model allowed exploring whether marital satisfaction (W) moderated the indirect effects of economic difficulties (X) on psychological maladjustment(Y) through perceived Stress (M).

The serial mediation model allowed for exploring the indirect effects of economic difficulties (X) on psychological maladjustment (Y) through perceived stress (M1) and marital satisfaction (M2) as serial mediators.

Results

Descriptive and correlational analyses

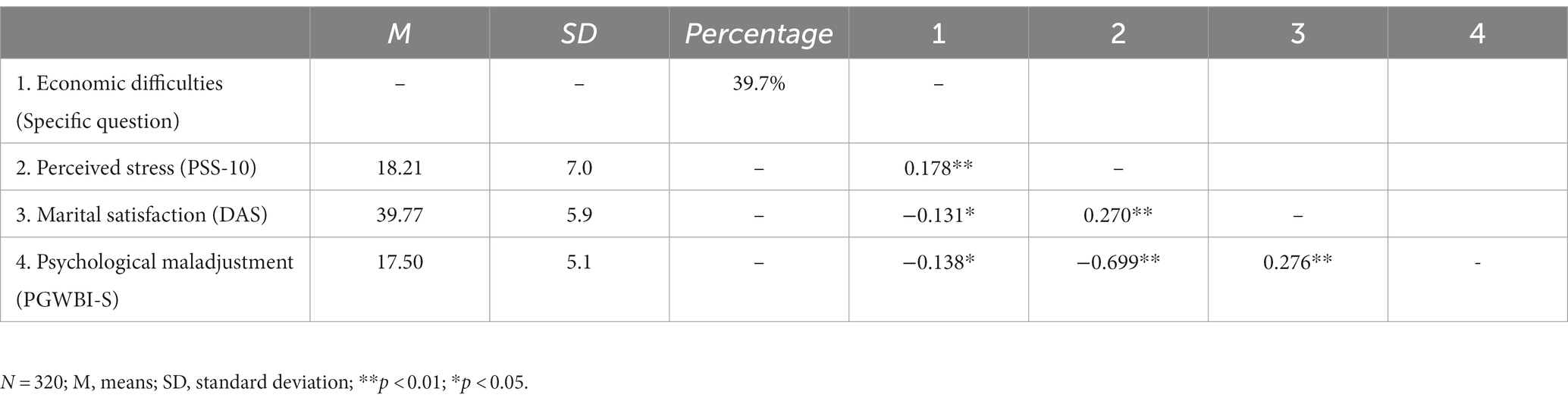

Descriptive statistics, point-biserial, and Pearson correlations are reported in Table 2. Means and standard deviations of scores in all scales were similar to those found in other Italian and international studies with normative samples (Grossi et al., 2006; Camisasca et al., 2016, 2019; Grabowski et al., 2021). Economic difficulties were significantly associated with perceived stress, marital satisfaction, and psychological maladjustment (r from −0.13 to 0.17), and perceived stress was correlated with both marital dissatisfaction (r = 0.27) and psychological maladjustment (r = −0.69).

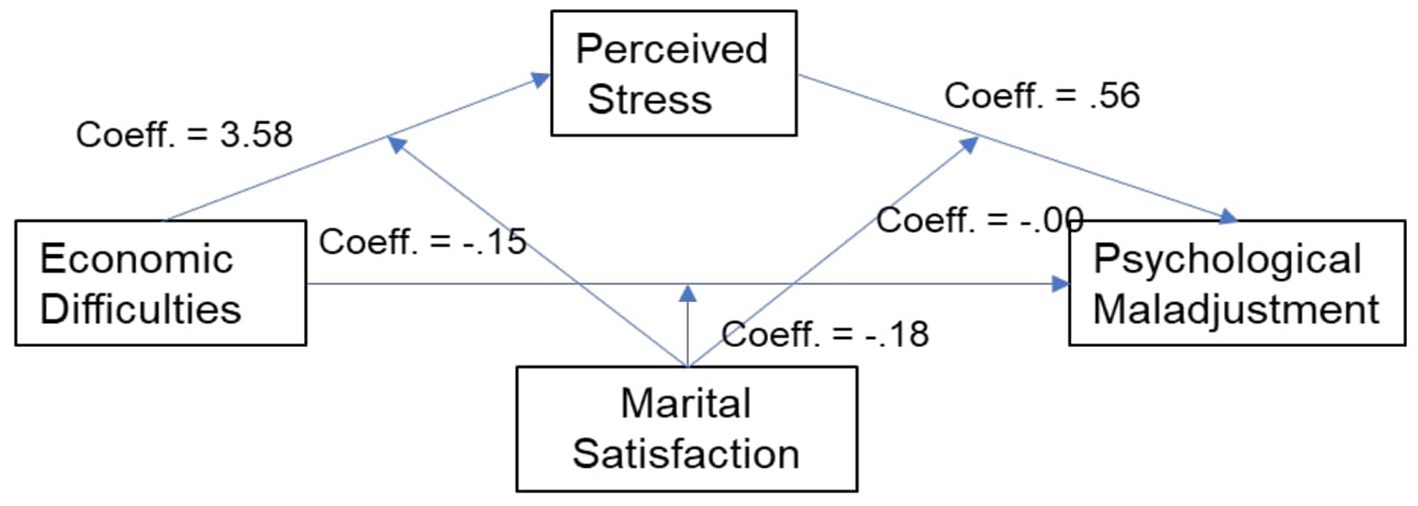

The moderated mediation model

This model (see Figure 1) allowed exploring whether marital satisfaction (W) moderated the indirect effects of economic difficulties (X) on psychological maladjustment (Y) through perceived stress (M). In the analyses, we also considered the effect of family income as a possible covariate.

Results showed that economic difficulties resulted in predicting the perceived stress (Coeff. = 3.58; p < 0.01; LLCI-ULCI: 0.58;6.59), while marital satisfaction did not moderate this association (Coeff. = −0.15; p 0.16; LLCI-ULCI: −0.36;0.06). Marital satisfaction did not even moderate the effect of economic difficulties on the psychological maladjustment (Coeff. = 0.18; p 0.08; LLCI-ULCI: −0.40;0.02) nor the effects of perceived stress on psychological maladjustment (Coeff. =0.003; p 0.06; LLCI-ULCI: −0.001;0.01). Finally, the indirect effect of economic difficulties on women’s psychological maladjustment through the mediation of perceived stress (R2 = 0.50; F = 53.03; p < 0.01; Eff. =0.37; LLCI-ULCI: −1.29; −2.04), was not moderated by marital satisfaction (Index of Moderated mediation; −0.08; LLCI-ULCI: −0.20;0.09). The covariate family income did not exert a predictive role on both perceived stress (Coeff. = 0.67; p = 0.06; LLCI-ULCI: −0.04;1,40) and psychological maladjustment (Coeff. = −0.16; p > 0.05; LLCI-ULCI: −0.53;0.20).

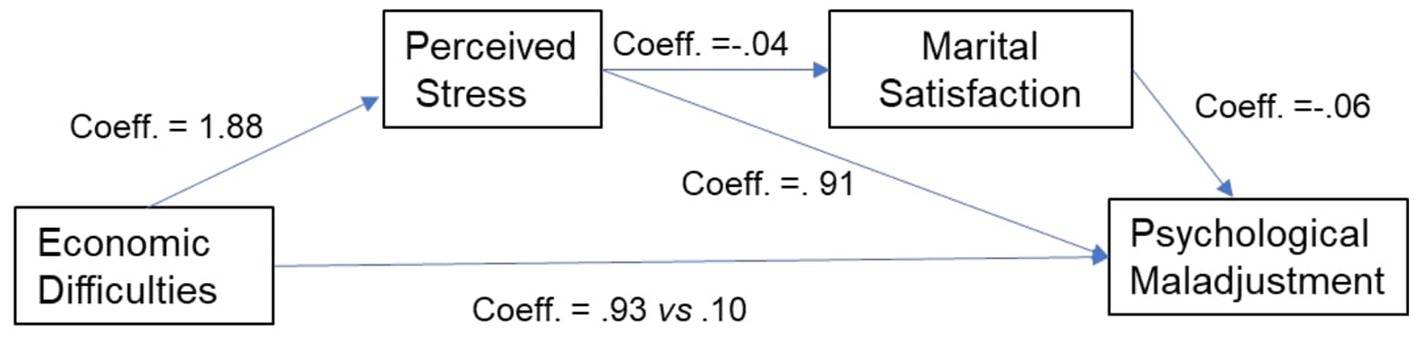

The serial mediation model

This model (see Figure 2) allowed for exploring the indirect effects of economic difficulties (X) on psychological maladjustment (Y) through perceived stress (M1) and marital satisfaction (M2) as serial mediators. In the analyses, we also considered the effects of family income as a possible covariate.

The total effect of economic difficulties on psychological maladjustment was statistically significant (Coeff. =0.93, p < 0.05; c path), while the direct effect was not found to be significant (Coeff. = 0.10 p = 0.81; c path). Additionally, significant indirect effects were found (R2 = 0.49; F = 104.25; p < 0.001). In particular, the first indirect pathway passed from X (economic difficulties) to Y (psychological maladjustment) through M1 (perceived Stress: Coeff. = 0.91; LLCI-ULCI: −1.98−0.09). The second indirect pathway passed from X (economic difficulties) to Y (psychological maladjustment) through M1 (perceived stress) negatively affecting M2, marital satisfaction (Coeff. = −0.04; LLCI-ULCI: −0.10;.−0.00).

The covariate family income did not exert a predictive role on either perceived stress (Coeff. = 0.66; p = 0.06; LLCI-ULCI: −0.02;1.34) or psychological maladjustment (Coeff. = −0.18; p > 0.05; LLCI-ULCI: −0.54;0.18).

Discussion

The Covid-19 pandemic involved an increase in economic difficulties with a consequent perceived psychological stress and a worsening of both mental health (Codagnone et al., 2020) and quality of family relationships (Pietromonaco and Overall, 2022). Thus, during the Covid-19 pandemic, some studies explored the predictive role of economic difficulties on both mental health and couple relationships (Balzarini et al., 2020; Falconier and Jackson, 2020). However, no study focused on marital satisfaction as a potential moderator or mediator of the effects of these associations. For this reason, we conducted a study in order to: (1) investigate the role of marital satisfaction in moderating the indirect effects of economic difficulties on psychological maladjustment through the mediation of perceived stress and (2) explore the potential spillover effect from economic difficulties to psychological maladjustment through the serial mediation of perceived stress and marital dissatisfaction.

Regarding the first aim, path analyses indicated that marital satisfaction did not moderate the indirect effects of economic difficulties on psychological maladjustment. In other words, we did not detect a protective role of marital satisfaction in decreasing the predictive impact of economic difficulties on psychological maladjustment. Results showed that economic difficulties predicted perceived stress which, in turn, predicted psychological maladjustment. However, these associations were not moderated by marital satisfaction.

The negative impact of economic difficulties on psychological maladjustment is consistent with the results of other contemporary studies, which showed that, aside from the utilitarian aspect of compensation, individuals derive significant meaning and value from their work (Crayne, 2020; Matthews et al., 2021; McDowell et al., 2021). As Crayne (2020, p. 180) suggested, “Work is a source of motivation and expression of personal beliefs that people hold as inextricable from their self-concept. Moreover, workplaces are a primary source of high-quality interpersonal interaction and relationship-building for many adults. Therefore, given the considerable proportion of adult life generally spent at work, it is reasonable that economic difficulties and work restrictions during the Covid-19 pandemic could have negatively contributed to psychological maladjustment.” However, in contrast with the buffering hypothesis (Cohen and Wills, 1985), which states that some factors, such as marital satisfaction (Rosand et al., 2011, 2012), may protect against severe effects of certain strains, this study’s results did not confirm the protective role of marital satisfaction. This finding aligns with the one reported by Balzarini et al. (2022, p. 24), who stated that “partner responsiveness is less effective in alleviating the strain from financial stress and financial concerns may be less mitigable through a partner’s support”. That is, when a partner feels lonely or stressed, a responsive partner could provide support through either spending time with his/her partner (to relieve loneliness) or being supportive of the stress. However, a partner’s support may not help relieve the financial strain because economic stressors may persist despite a partner’s responsiveness (e.g., if an individual loses a job, a partner’s support and responsiveness might not be useful to mitigate financial concerns and economic difficulties). In line with our results, Shi and Whisman (2023) in a recent longitudinal study showed that marital satisfaction did not moderate the association between acute stressful life events and depressive symptoms.

Concerning the second aim, results showed a significant spillover effect from economic difficulties to psychological maladjustment. The spillover effect was detected through higher levels of perceived stress and marital dissatisfaction. Our results about the predictive effect of economic difficulties on perceived stress are consistent with those of the literature (Harvey and Bray, 1991; Achdut and Refaeli, 2020; Friedline et al., 2021; Hertz-Palmor et al., 2021), which showed that unemployment and economic difficulties had high psychological costs, including the potential loss of meaning in life, impairment of personal identity, and the reduction of self-esteem that an individual typically draws from his/her job. Therefore, economic difficulties and strain promoted higher worry, tension, unhappiness, pessimism, and perceived stress.

Our data also indicated that the adverse emotional climate due to perceived stress spilled over to the couple’s relationship by increasing marital dissatisfaction and unhappiness. This result is also consistent with the literature (Pietromonaco and Overall, 2020; Işık and Kaya, 2022), which showed that increased levels of perceived stress led to decreased spousal support and marital satisfaction during the Covid-19 pandemic. Specifically, Pietromonaco and Overall (2020, p. 4) argued that “external stress made it difficult for partners to be responsive to each other because they were distracted, fatigued, or overwhelmed. As a result of this emotional climate, partners can become overly critical or argumentative, blame their partner, provide poorer support, and, over time, become less satisfied with their partner and relationship.” Again, Turliuc and Candel (2021) indicated that higher levels of external stress were associated with subsequent lower marital satisfaction during the Covid-19 pandemic, particularly for women.

Another significant result of our study is that the quality of the couple’s relationship, denoted by unhappiness and dissatisfaction, was directly associated with psychological maladjustment in women. This result is in line with previous studies (see Falconier et al., 2015), which showed that extra-dyadic stress is directly and indirectly related to lower psychological well-being through increased intra-dyadic stress from relationship problems. In particular, the female extra-dyadic and intra-dyadic stress negatively affected relationship satisfaction and posed more risks for marital quality.

In sum, the results of the present study confirm the significant role of marital dissatisfaction in explaining the indirect effects of economic difficulties on psychological maladjustment in women. In particular, they indicated a significant spillover effect which transmitted strains experienced in one domain (economic difficulties) to another (the dissatisfaction of the couple), which in turn affected the psychological maladjustment.

Limitations and future directions of research

A series of limitations affect the findings of this study. The first one is that only one individual in the couple (a woman) was involved, preventing the analyses of the interplay between the couple’s members. Examining both partners and using dyadic data would have improved the knowledge of the associations of the considered variables. Second, the cross-section design of the study cannot demonstrate any causal effect. Results should thus be interpreted cautiously, and bi-directional effects could be considered. For example, we could also explore how economic difficulties affect psychological maladjustment, which in turn could be associated with marital dissatisfaction. Third, the sociodemographic homogeneity of participants and the small sample size limit the generalizability of results, even though the bootstrapping method could partly overcome this limitation. Another limitation is due to the single-item question used to assess the economic difficulties. We used a single-item query with a dichotomic answer to detect the presence/absence of economic difficulties (due to the pandemic). The use of an interval-level scale could have allowed a better and more detailed understanding of the degree of Covid-19 economic impact. Moreover, although we considered the family income as a covariate in the mediational analyses, the exploration, in further research, of other variables (the sample’s professional condition before and during the Covid pandemic) could be useful to better understand the associations investigated.

Moreover, another limitation consisted in administering only the items of the subscale dyadic satisfaction of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS). Indeed, exploring the other dimensions of this scale could allow an in-depth understanding of the role of the quality of the couple’s relationship in the associations investigated. A last limitation is related to the self-reported data because it is well known that self-report measures assessing sensitive information can be affected by social desirability, which could have inflated some associations.

Despite these limitations, the results of the present study can contribute to the advancement of knowledge about the effect that economic difficulties during the Covid-19 pandemic had on women’s psychological well-being through the mediation of both perceived stress and marital dissatisfaction. Longer-term studies could indicate whether these changes in relationship satisfaction remain a temporary phenomenon or will continue after the Covid-19 pandemic and, eventually, substantiate increased risks of partnership dissolution. Moreover, our results substantiate the importance of better understanding the associations between economic difficulties, marital satisfaction, and psychological maladjustment by assuming the interdependence between husband and wife. Therefore, future studies could consider the crucial aspects of interpersonal interaction in intimate relationships using an analysis method focused on the internal correlation of couple data. In this perspective, the actor–partner interdependence model (APIM, Kenny and Cook, 1999) can be used to investigate dyadic paired data, which can be examined directly at the dyadic level, as well as roles and partnerships.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Achdut, N., and Refaeli, T. (2020). Unemployment and psychological distress among young people during the COVID-19 pandemic: psychological resources and risk factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:7163. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197163

Archuleta, K. L., Britt, S. L., Tonn, T. J., and Grable, J. E. (2011). Financial satisfaction and financial stressors in marital satisfaction. Psychol. Rep. 108, 563–576. doi: 10.2466/07.21.PR0.108.2.563-576

Armour, C., McGlinchey, E., Butter, S., McAloney-Kocaman, K., and McPherson, K. E. (2021). The COVID-19 psychological wellbeing study: understanding the longitudinal psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK; a methodological overview paper. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 43, 174–190. doi: 10.1007/s10862-020-09841-4

Balzarini, R. N., Muise, A., Zoppolat, G., Di Bartolomeo, A., Rodrigues, D. L., Alonso-Ferres, M., et al. (2020). Love in the time of COVID: perceived partner responsiveness buffers people from lower relationship quality associated with covid-related stressors. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 14, 342–355. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/e3fh4

Balzarini, R. N., Muise, A., Zoppolat, G., Gesselman, A. N., Lehmiller, J. J., Garcia, J. R., et al. (2022). Sexual desire in the time of COVID-19: how COVID-related stressors are associated with sexual desire in romantic relationships. Arch. Sex. Behav. 51, 3823–3838. doi: 10.1007/s10508-022-02365-w

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395, 912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Camisasca, E., Miragoli, S., Di Blasio, P., and Feinberg, M. (2019). Co-parenting mediates the influence of marital satisfaction on child adjustment: the conditional indirect effect by parental empathy. J. Child Fam. Stud. 28, 519–530. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1271-5

Camisasca, E., Miragoli, S., Milani, L., and Di Blasio, P. (2016). Adattamento di coppia, cogenitorialità e benessere psicologico dei figli: uno studio esplorativo [Marital adjustment, coparenting and children’s psychological adjustment: an exploratory study]. Psicologia della Salute 2, 127–141. doi: 10.3280/PDS2016-002007

Chai, L. (2023). Financial strain and psychological distress among middle-aged and older adults: a moderated mediation model. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 3, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2023.2207611

Codagnone, C., Bogliacino, F., Gómez, C., Charris, R., Montealegre, F., Liva, G., et al. (2020). Assessing concerns for the economic consequence of the COVID-19 response and mental health problems associated with economic vulnerability and negative economic shock in Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. PLoS One 15:e0240876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240876

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., and Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 24, 385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404

Cohen, S., and Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98, 310–357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Conger, R. D., Rueter, M. A., and Elder, G. H. Jr. (1999). Couple resilience to economic pressure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 76, 54–71. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.76.1.54

Crayne, M. P. (2020). The traumatic impact of job loss and job search in the aftermath of COVID-19. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 12, S180–S182. doi: 10.1037/tra0000852

Dew, J., Britt, S., and Huston, S. (2012). Examining the relationship between financial issues and divorce. Fam. Relat. 61, 615–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00715.x

Dupuy, H. J. (1984). The general psychological well-being (PGWB) index. Assessment of quality of life in clinical trials of cardiovascular therapies, 170–183. Available at: https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/10027309413/

Epifani, I., Wisyaningrum, S., and Ediati, A. (2021). “Marital distress and satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review.” Proceedings of the International Conference on psychological studies (ICPSYCHE 2020) (Netherlands: Atlantis Press), 109–115.

Ettman, C. K., Abdalla, S. M., Cohen, G. H., Sampson, L., Vivier, P. M., and Galea, S. (2020). Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 3:e2019686. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686

Falconier, M. K., and Jackson, J. B. (2020). Economic strain and couple relationship functioning: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 27, 311–325. doi: 10.1037/str0000157

Falconier, M. K., Nussbeck, F., Bodenmann, G., Schneider, H., and Bradbury, T. (2015). Stress from daily hassles in couples: its effects on intradyadic stress, relationship satisfaction, and physical and psychological well-being. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 41, 221–235. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12073

Fitzpatrick, K. M., Harris, C., and Drawve, G. (2020). Living in the midst of fear: depressive symptomatology among US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Depress. Anxiety 37, 957–964. doi: 10.1002/da.23080

Fossati, A. (2010). Italian translation of the perceived stress scale. Available at: https://www.cmu.edu/dietrich/psychology/stress-immunity-disease-lab/scales/.doc/italian_pss_10_with_info.doc

Friedline, T., Chen, Z., and Morrow, S. P. (2021). Families' financial stress & well-being: the importance of the economy and economic environments. J. Fam. Econ. Iss. 42, 34–51. doi: 10.1007/s10834-020-09694-9

Frone, M. R. (2003). “Work-family balance” in Handbook of occupational health psychology. eds. J. C. Quick and L. E. Tetrick (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 143–162.

Gamonal-Limcaoco, R. S., Mateos, E. M., Fernández, J. M., and Roncero, C. (2020). Anxiety, worry, and perceived stress in the world due to the COVID-19 pandemic, march 2020. Preliminary results. MedRxiv, 2020-04. [Epub ahead of preprint] doi: 10.1101/2020.04.03.20043992

Gentili, P., Contreras, L., Cassaniti, M., and D'arista, F. (2002). La Dyadic Adjustment Scale: Una misura dell'adattamento di coppia. Minerva Psichiatr. 43, 107–116.

Grabowski, J., Stepien, J., Waszak, P., Michalski, T., Meloni, R., Grabkowska, M., et al. (2021). Social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Perceived stress and containment measures compliance among polish and Italian residents. Front. Psychol. 12:673514. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.673514

Grossi, E., Groth, N., Mosconi, P., Cerutti, R., Pace, F., Compare, A., et al. (2006). Development and validation of the short version of the psychological general well-being index (PGWB-S). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 4, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-88

Gudmunson, C. G., Beutler, I. F., Israelsen, C. L., McCoy, J. K., and Hill, E. J. (2007). Linking financial strain to marital instability: examining the roles of emotional distress and marital interaction. J. Fam. Econ. Iss. 28, 357–376. doi: 10.1007/s10834-007-9074-7

Harvey, D. M., and Bray, J. H. (1991). Evaluation of an intergenerational theory of personal development: family process determinants of psychological and health distress. J. Fam. Psychol. 4, 298–325. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.4.3.298

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Available at: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

Hayes, A. F. (Editor) (2013). “Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis” in Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (New York, NY: Guilford Publications), 1–20.

Hayes, A. F., and Preacher, K. J. (2013). “Conditional process modeling: using structural equation modeling to examine contingent causal processes” in Structural equation modeling: A second course. eds. G. R. Hancock and R. O. Mueller (Charlotte: IAP Information Age Publishing), 219–266.

Hensher, D. A. (2020). What might Covid-19 mean for mobility as a service (MaaS)? Transp. Rev. 40, 551–556. doi: 10.1080/01441647.2020.1770487

Hertz-Palmor, N., Moore, T. M., Gothelf, D., DiDomenico, G. E., Dekel, I., Greenberg, D. M., et al. (2021). Association among income loss, financial strain, and depressive symptoms during COVID-19: evidence from two longitudinal studies. J. Affect. Disord. 291, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.054

Horwitz, A. V., White, H. R., and Howell-White, S. (1996). Becoming married and mental health: a longitudinal study of a cohort of young adults. J. Marriage Fam. 58, 895–907. doi: 10.2307/353978

Ilies, R., Schwind, K. M., Wagner, D. T., Johnson, M. D., DeRue, D. S., and Ilgen, D. R. (2007). When can employees have a family life? The effects of daily workload and affect on work-family conflict and social behaviors at home. J. Appl. Psychol. 92, 1368–1379. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1368

International Labour Organization (2020). ILO monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. Updated Estimates and Analysis. Int Labour Organ. Available at: http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/533608

Işık, R. A., and Kaya, Y. (2022). The relationships among perceived stress, conflict resolution styles, spousal support, and marital satisfaction during the COVID-19 quarantine. Curr. Psychol. 41, 3328–3338. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02737-4

Jesus, S. N., Leal, A. R., and Viseu, J. N. (2016). Coping as a moderator of the influence of economic stressors on psychological health. Análise Psicológica. 34, 365–376. doi: 10.14417/ap.1122

Kelley, M., Ferrand, R. A., Muraya, K., Chigudu, S., Molyneux, S., Pai, M., et al. (2020). An appeal for practical social justice in the COVID-19 global response in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob. Health 8, e888–e889. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30249-7

Kelley, H. H., Lee, Y., LeBaron-Black, A., Dollahite, D. C., James, S., Marks, L. D., et al. (2022). Change in financial stress and relational well-being during COVID-19: exacerbating and alleviating influences. J. Fam. Econ. Iss. 44, 34–52. doi: 10.1007/s10834-022-09822-7

Kenny, D. A., and Cook, W. (1999). Partner effects in relationship research: conceptual issues, analytic difficulties, and illustrations. Pers. Relat. 6, 433–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1999.tb00202.x

Kouros, C. D., Papp, L. M., Goeke-Morey, M. C., and Cummings, E. M. (2014). Spillover between marital quality and parent–child relationship quality: parental depressive symptoms as moderators. J. Fam. Psychol. 28, 315–325. doi: 10.1037/a0036804

Lincoln, K. D., and Chae, D. H. (2010). Stress, marital satisfaction, and psychological distress among African Americans. J. Fam. Issues 31, 1081–1105. doi: 10.1177/0192513X10365826

Matthews, T. A., Chen, L., Chen, Z., Han, X., Shi, L., Li, Y., et al. (2021). Negative employment changes during the COVID-19 pandemic and psychological distress: evidence from a nationally representative survey in the US. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 63, 931–937. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002325

McDowell, C. P., Herring, M. P., Lansing, J., Brower, C. S., and Meyer, J. D. (2021). Associations between employment changes and mental health: US data from during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 12:631510. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631510

Pieh, C., O’Rourke, T., Budimir, S., and Probst, T. (2020). Relationship quality and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown. PLoS One 15:e0238906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238906

Pieh, C., Probst, T., Budimir, S., and Humer, E. (2021). Associations between relationship quality and mental health during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:2869. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18062869

Pierce, M., Hope, H., Ford, T., Hatch, S., Hotopf, M., John, A., et al. (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 883–892. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4

Pietromonaco, P. R., and Overall, N. C. (2020). Applying relationship science to evaluate how the COVID-19 pandemic may impact couples' relationships. Am. Psychol. 76, 438–450. doi: 10.1037/amp0000714

Pietromonaco, P. R., and Overall, N. C. (2022). Implications of social isolation, separation, and loss during the COVID-19 pandemic for couples' relationships. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 43, 189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.07.014

Reizer, A., Koslowsky, M., and Geffen, L. (2020). Living in fear: the relationship between fear of COVID-19, distress, health, and marital satisfaction among Israeli women. Health Care Women Int. 41, 1273–1293. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2020.1829626

Romeo, A., Castelli, L., Benfante, A., and Tella, M. D. (2022). Love in the time of COVID-19: the negative effects of the pandemic on psychological well-being and dyadic adjustment. J. Affect. Disord. 299, 525–527. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.078

Rosand, G. M., Slinning, K., Eberhard-Gran, M., Roysamb, E., and Tambs, K. (2011). Partner relationship satisfaction and maternal emotional distress in early pregnancy. BMC Public Health 11:161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-161

Rosand, G. M., Slinning, K., Eberhard-Gran, M., Roysamb, E., and Tambs, K. (2012). The buffering effect of relationship satisfaction on emotional distress in couples. BMC Public Health 12, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-66

Ruengorn, C., Awiphan, R., Wongpakaran, N., Wongpakaran, T., and Nochaiwong, S. (2021). Health outcomes and mental health care evaluation survey research group (HOME-survey). Association of job loss, income loss, and financial burden with adverse mental health outcomes during coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in Thailand: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Depress. Anxiety 38, 648–660. doi: 10.1002/da.23155

Shi, Y., and Whisman, M. A. (2023). Marital satisfaction as a potential moderator of the association between stress and depression. J. Affect. Disord. 327, 155–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.093

Simon, R. W. (2002). Revisiting the relationships among gender, marital status, and mental health. Am. J. Sociol. 107, 1065–1096. doi: 10.1086/339225

Spanier, G. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: new scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J. Marriage Fam. 38, 15–28. doi: 10.2307/350547

Stewart, R. C., Dew, J. P., and Lee, Y. G. (2017). The association between employment- and housing-related financial stressors and marital outcomes during the 2007–2009 recession. J. Financial Therapy 8, 43–61. doi: 10.4148/1944-9771.1125

Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 52, 145–161. doi: 10.1177/0022146510395592

Trógolo, M. A., Moretti, L. S., and Medrano, L. A. (2022). A nationwide cross-sectional study of workers’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: impact of changes in working conditions, financial hardships, psychological detachment from work and work-family interface. BMC psychol. 10:73. doi: 10.1186/s40359-022-00783-y

Turliuc, M. N., and Candel, O. S. (2021). Not all in the same boat. Socioeconomic differences in marital stress and satisfaction during the Covid-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 12:35148. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635148

Twenge, J. M., and Joiner, T. E. (2020). US Census Bureau-assessed the prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Depress. Anxiety 37, 954–956. doi: 10.1002/da.23077

van der Velden, P. G., Contino, C., Das, M., van Loon, P., and Bosmans, M. W. (2020). Anxiety and depression symptoms and lack of emotional support among the general population before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. A prospective national study on prevalence and risk factors. J. Affect. Disord. 277, 540–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.026

Viseu, J., Leal, R., de Jesus, S. N., Pinto, P., Pechorro, P., and Greenglass, E. (2018). Relationship between economic stress factors and stress, anxiety, and depression: moderating role of social support. Psychiatry Res. 268, 102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.008

Wang, D., Hu, B., Hu, C., Zhu, F., Liu, X., Zhang, J., et al. (2020). Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 323, 1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585

Williams, K. (2003). Has the future of marriage arrived? A contemporary examination of gender, marriage, and psychological well-being. J. Health Soc. Behav. 44, 470–487. doi: 10.2307/1519794

Wilson, J. M., Lee, J., Fitzgerald, H. N., Oosterhoff, B., Sevi, B., and Shook, N. J. (2020). Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with worse mental health. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 62, 686–691. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001962

Keywords: COVID-19, economic difficulties, perceived stress, marital satisfaction, psychological maladjustment, women

Citation: Camisasca E, Covelli V, Cafagna D, Manzoni GM, Cantoia M, Bavagnoli A, Crescenzo P, Marsicovetere V, Pesce M and Visco MA (2023) From economic difficulties to psychological maladjustment in Italian women during the Covid-19 pandemic: does marital dissatisfaction moderate or mediate this association? Front. Psychol. 14:1166049. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1166049

Edited by:

Ramona Bongelli, University of Macerata, ItalyReviewed by:

Federica Biassoni, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyOctav Sorin Candel, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, Romania

Copyright © 2023 Camisasca, Covelli, Cafagna, Manzoni, Cantoia, Bavagnoli, Crescenzo, Marsicovetere, Pesce and Visco. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elena Camisasca, ZWxlbmEuY2FtaXNhc2NhQHVuaWVjYW1wdXMuaXQ=

Elena Camisasca

Elena Camisasca Venusia Covelli

Venusia Covelli Dario Cafagna

Dario Cafagna Gian Mauro Manzoni1

Gian Mauro Manzoni1 Pietro Crescenzo

Pietro Crescenzo Mario Pesce

Mario Pesce Marina Angela Visco

Marina Angela Visco