Abstract

We overview our recent developments on a computational approach addressing quantum confinement of light atomic and molecular clusters (made of atomic helium and molecular hydrogen) in carbon nanotubes. We outline a multi-scale first-principles approach, based on density functional theory (DFT)-based symmetry-adapted perturbation theory, allowing an accurate characterization of the dispersion-dominated particle–nanotube interaction. Next, we describe a wave-function-based method, allowing rigorous fully coupled quantum calculations of the pseudo-nuclear bound states. The approach is illustrated by showing the transition from molecular aggregation to quasi-one-dimensional condensed matter systems of molecular deuterium and hydrogen as well as atomic 4He, as case studies. Finally, we present a perspective on future-oriented mixed approaches combining, e.g., orbital-free helium density functional theory (He-DFT), machine-learning parameterizations, with wave-function-based descriptions.

1 Introduction

The cylindrical confinement provided by carbon nanotubes has offered the possibility of studying the pronounced quantum behaviour of 4He atoms and H2 molecules at reduced dimensionality. Recent measurements have demonstrated the formation of two-dimensional (2D) 4He layers on the outer surface of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) (Noury et al., 2019). Also, an experimental study (Ohba, 2016) of gas adsorption at low (2–5 K) temperature revealed a quenched propagation of 4He atoms through carbon nanopores with diameters below 7 Å despite of their small kinetic diameter. The application of orbital-free helium density functional theory (He-DFT) to carbon nanotubes immersed in a helium nanodroplet provided theoretical explication that the experimental observations stem from the exceptionally high zero-point energy of 4He as well as its tendency to form two-dimensional (2D) layers upon adsorption at low temperatures (Hauser and de Lara-Castells, 2016). These conclusions were further confirmed by applying more accurate ab initio potential modelling along with a wave-function (WF)-based approach (Hauser et al., 2017). This study also showed that SWCNTs are filled by more molecules of N2 than 4He atoms, due to the higher zero-point energy of the latter. More generally, the interaction of small atomic and molecular systems with carbon-based nanostructures has attracted a lot of attention recently (see, e.g. Deb et al., 2016; Deb et al., 2019; Paul et al., 2019; Paul et al., 2020 and references therein).

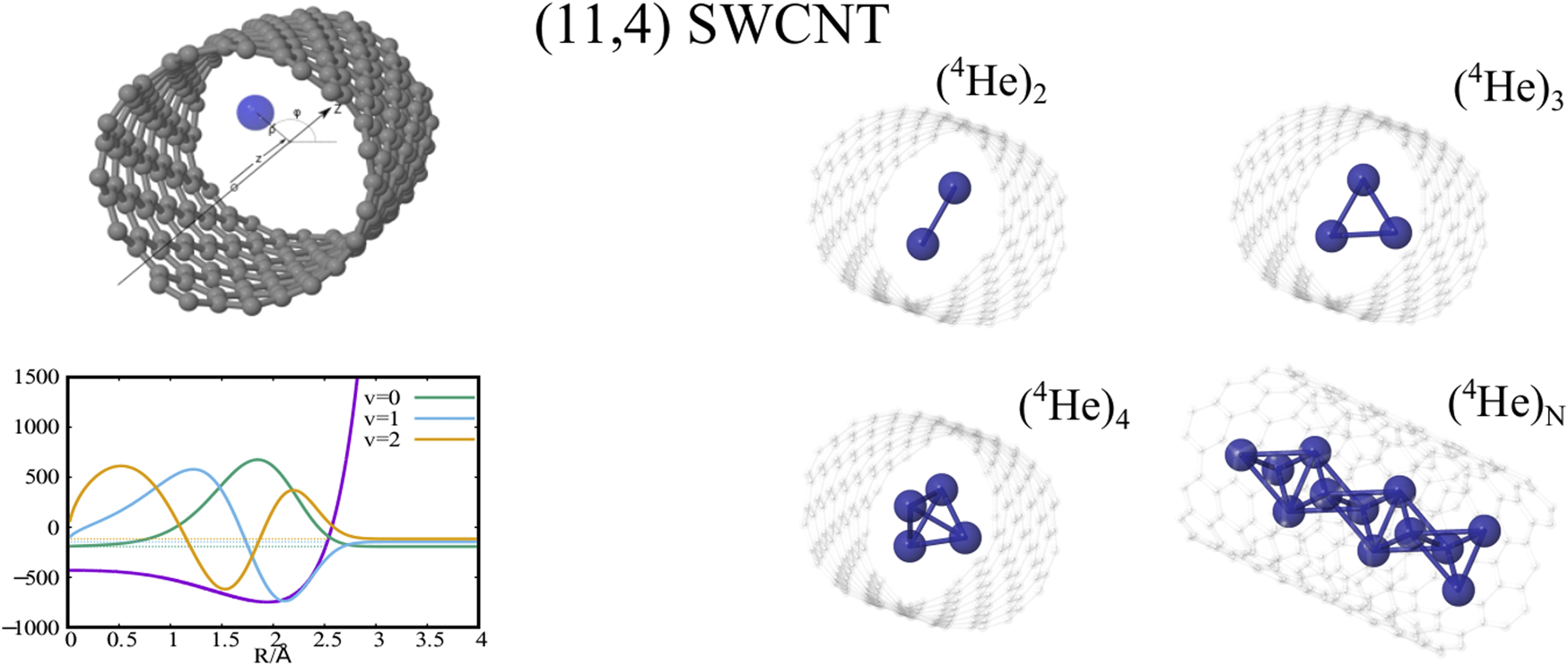

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

For the case of molecular deuterium, our recent theoretical work has provided conclusive evidence for the transition from molecular aggregation to quantum solid-like packing in a SWCNT of 1 nm diameter (de Lara-Castells and Mitrushchenkov, 2020; de Lara-Castells and Mitrushchenkov, 2021), confirming a previous study using an embedding approach in a broader (ca. 1.4 nm) SWCNT (de Lara-Castells et al., 2017). Experimental evidence, using neutron scattering, on the formation of one-dimensional D2 crystals under carbon nanotube confinement has been reported as well (Cabrillo et al., 2021). Altogether, these studies have confirmed the key role played by the quantum nature of the nuclear degrees of freedom in the confined atomic helium, molecular hydrogen, or molecular deuterium motion.

The quest for the understanding of the aggregation of molecular H2 in carbon nanotubes is also application-oriented as it is being actively used as a clean energy source, substituting fossil fuels. In fact, its combustion produces only heat and water, and it can be efficiently combined with oxygen in a fuel cell to produce electricity. Yet, the usage of hydrogen as a profit fuel requires a substantial development of efficient storage materials (Schlapbach and Züttel, 2001; Züttel, 2003; Zheng et al., 2021) such as metal organic frameworks, Rosi et al. (2003) covalent organic frameworks (Zheng et al., 2021), and carbon-based nanoporous materials (Cheng et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2010). Hydrogen storage methods are aimed to pack hydrogen molecules as close as possible, existing direct experimental evidences for solid-like packing of hydrogen at temperatures of industrial importance (Ting et al., 2015). Actually, the question on the nature of the hydrogen packing in carbon nanotubes is truly fundamental. Thus, the possible existence of either a superfluid (Rossi and Ancilotto, 2016) or a crystalline phase (Del Maestro and Boninsegni, 2017; Ferré et al., 2017) for para-H2 molecules inside carbon nanotubes at zero (Rossi and Ancilotto, 2016; Ferré et al., 2017) or ultra-low temperatures (Del Maestro and Boninsegni, 2017) have been addressed as well (see also (Cazorla and Boronat, 2017) for a recent review). Specially appealing in regards to the impact of quantum effects on the diffusion of H2 and D2 along carbon nanotubes is the experimental finding of reserved trends in their rates upon cooling (Nguyen et al., 2010), with the D2 isotope becoming the faster inspite of its higher mass (Nguyen et al., 2010). The impact of quantum effects in confined H2 and D2 motion has been theoretically confirmed as well (Mondelo-Martell and Huarte-Larrañaga, 2016; Mondelo-Martell et al., 2017; Mondelo-Martell and Huarte-Larrañaga, 2021).

The high interest on the confinement of clusters of atomic 4He is also related to the superfluid nature of 4He droplets at a temperature close to absolute zero (0.4 K) (Mudrich and Stienkemeier, 2014) and, more specifically, to the onset of such fascinating property in doped clusters made of just a few 4He atoms (Toennies and Vilesov, 2004). Then, the question is whether the confinement provided by SWCNTs can favour the emergence of such feature at reduced dimensionality. The effect of carbon nanotube confinement has been also shown to be remarkable for the 3He isotope inside a SWCNT of 1 nm diameter. Thus, as opposed to the free dimer case, the confined 3He dimer is predicted to be bound, mainly as a consequence of the strong localization along the radial 3He–SWCNT direction (de Lara-Castells and Mitrushchenkov, 2021).

This overview article is organized as follows. The next section presents the computational approach addressing the modeling of intermolecular adsorbate–SWCNT interactions as well as fully coupled quantum calculations of the corresponding pseudo-nuclear wavefunctions. Section 3 presents an illustrative application of the computational approach to the transition from molecular aggregation to quasi-one-dimensional (1D) matter systems composed by either D2/H2 molecules or 4He atoms. Finally, Section 4 closes with a summary of concluding remarks and a few future prospects.

2 Computational Approach

2.1 Ab Initio Modelling of the Adsorbate-Nanotube Interaction

Achieving a correct description of the interaction of the lightest atomic and molecular clusters in nature (i.e., made of He or H2) with its confining SWCNT environment is a challenge even for expensive ab initio methods since they are dominated by long-range dispersion forces (van der Waals forces). Extended dispersion-corrected DFT methods are applicable including confinement effects in extended SWCNT structures but they bear a tendency to overshoot when applied to ultimate cases of dispersion-dominated (e.g., He-surface) interactions. One key idea has consisted in designing a functional [the so-called dlDF functional (Pernal et al., 2009)] which accounts for the dispersionless interaction energy only so that the dispersion corrections can be safely added later. Within a practical implementation of this idea, the incremental method (Stoll, 1992) is applied on non-periodic (small) cluster models of extended systems and combined with periodic dispersionless DFT calculations (de Lara-Castells et al., 2014b; de Lara-Castells et al., 2014a). This approach has been shown to be particularly successful when describing the interaction of atomic helium (de Lara-Castells et al., 2014a) as well as heavier noble gases (de Lara-Castells et al., 2015) with coronene/graphene/graphite surfaces. Very recently, it has been also demonstrated how modern ab initio intermolecular perturbation theory allows a cost-effective and accurate characterization of van der Waals-dominated He-SWCNT and H2-SWCNT interactions using small clusters models of the SWCNTs. The use of small cluster models is justified as complicated, dispersionless contributions are mostly of short-range nature. Dispersion, on the other hand, is long-range, but the corresponding parameters show excellent transferability properties upon increasing the size of the surface cluster models (de Lara-Castells et al., 2014a; de Lara-Castells et al., 2015). Therefore, these parameters can be calculated at high level of ab initio theory on small clusters and then scaled to the actual SWCNT system. As previously emphasized (de Lara-Castells and Hauser, 2020), detailed energy decomposition schemes, an intrinsic feature of methods such as density functional theory (DFT)-based symmetry-adapted perturbation theory [SAPT(DFT)] (Hesselmann and Jansen, 2003; Misquitta et al., 2003; Heßelmann et al., 2005; Misquitta et al., 2005) has been shown to be particularly useful in this respect.

In our most recent works (de Lara-Castells and Mitrushchenkov, 2020; de Lara-Castells and Mitrushchenkov, 2021), the SAPT(DFT) method has been used to derive by fitting the dispersionless and dispersion SAPT(DFT) energy contributions to an additive pairwise potential model (PPM) (de Lara-Castells et al., 2016; Hauser and de Lara-Castells, 2017; de Lara-Castells et al., 2017; Hauser et al., 2017), which is a modified version of that proposed by Carlos and Cole (Carlos and Cole, 1980). For the illustrative cases presented in this work, these terms were calculated for the interaction between a single H2 molecule (He atom) and a hydrogen-saturated (unsaturated) nanotube SWCNT(5, 5) tube made of 62 (40) atoms, considering two transverse sections of the tube. The SAPT(DFT) MOLPRO (Heßelmann et al., 2005; Werner et al., 2012) implementation was applied, using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) density functional (Perdew et al., 1996) and the augmented polarized correlation-consistent triple-zeta basis (Woon et al., 1994) for all atoms but the hydrogen atoms saturating the dangling bonds, for which the correlation-consistent double-zeta basis was used instead.

The PPM functional form (de Lara-Castells et al., 2016; Hauser and de Lara-Castells, 2017; de Lara-Castells et al., 2017; Hauser et al., 2017) for the dispersionless energy contribution accounts for the typical exponential growth of the dominant dispersionless term, the exchange-repulsion, but also including a Gaussian-type “cushion” to describe weakly attractive tails stemming from other dispersionless termswhere Rc is a cut-off distance, RA-C stands for the distance between the adsorbate center-of-mass and one carbon atom of the SWCNT, and θC is the angle between the radial vector going from the SWCNT center to one carbon atom and the vector RA-C pointing from the adsorbate center-of-mass to the same C atom. The dimensionless factor γR in the first term accounts for the anisotropy of the C − C bonds. The sum in Eq. (1) runs over all carbon atoms of the nanotube. For the dispersion part, we apply the typical C6/C8 expansion with the damping functions of Tang and Toennies fn (n = 6, 8) (Tang and Toennies, 1984)where γA is also a dimensionless anisotropy parameter. The inclusion of γA and γR anisotropy terms has been found to be important when modelling potential corrugation effects on both curved carbon and metallic surfaces (de Lara-Castells et al., 2016; Hauser and de Lara-Castells, 2017; Hauser et al., 2017).

2.2 The Pseudo-Nuclear Wave-Function Problem

Our method has been designed to allow bound-state calculations for N identical atoms or molecules (referred to as “pseudo-nuclei”, PNs) inside a SWCNT. Using cylindrical coordinates (xi, yi, zi → ρi, ϕi, zi) for each PN (see left panel of Figure 1), together with a Jacobian transformation of the volume to keep the Hamiltonian “explicitly Hermitian”, , the Hamiltonian describing a motion of N PN’s takes the formwhere the distance rij is explicitly given by

FIGURE 1

Top panel. Left-hand side: Radial scan of the interaction energies between a single H2 molecule and a short (single-walled) carbon nanotube (sCNT) of helicity index (5, 5). The pairwise potential model is compared with reference ab initio calculations using the SAPT(DFT) approach. Right-hand side: Radial scan of the total interaction energies (full lines) and dispersion contributions (dashed lines) between a single H2 molecule and carbon nanotubes with helicity indexes of increasing value. Source: (de Lara-Castells et al., 2017) Bottom panel. Left-hand side: Cylindrical coordinates describing a single particle in a tube. Right-hand side: interaction potentials PN-CNT (A, B) and PN-PN (C, D) together with the corresponding low-lying bound states of a single confined PN. (A, C): PN = H2, (B, D): PN = 4He. Source: (de Lara-Castells and Mitrushchenkov, 2021).

We note that, in order to preserve the cylindrical symmetry of the system, the very small corrugation appearing along the azimuthal degree of freedom ϕ is not accounted for. Considering long nanotubes, it is thus assumed that the interaction potential depends only on ρ. The atomic structure of the SWCNT, however, is implicitly considered through the SAPT(DFT) calculations used to fit the parameters of our PPM (see Section 3.1). These potentials are used within the Discrete Variable Representation (DVR) approach (Bačic̀ and Light, 1989) upon fitting them to polynomials of ρ:

To separate the overall Z-translation and overall rotational motions, we introduce relative coordinates as ti = zi − zN and χi = ϕi − ϕN, for i = 1 … N − 1. The overall Z-translation and overall rotation coordinates are conveniently defined as and Φ = ϕN. The overall rotation quantum number reads Λ = m1 + m2 + ⋯ + mN, where mi is the integer standing for the projection of the angular momentum of the i-th particle onto the nanotube axis. Since both PN–SWCNT and PN–PN interactions do not depend on Φ, the coordinate Φ can be separated via the factor . Finally, the full kinetic energy is written as whereand

We note that the internal Hamiltonian does not account explicitly for the bosonic permutation symmetry of all N particles. The symmetry is automatically included for the particles labelled as 1 … N − 1 since it is equivalent to a simple exchange of the corresponding coordinates ti, ρi, χi. The exchange of the particles labelled as i and N, however, results in linear transformations of the coordinates ti and χi. The symmetry with respect to the i ↔ N exchange is analyzed a posteriori by defining a “bosonic symmetry factor” Q as the matrix element:

The Q factor is unity for true bosonic solutions. This test is used as a criteria to evaluate the wavefunction accuracy.

To calculate the eigenvalues of the internal Hamiltonian, we use the DVR approach (Bačic̀ and Light, 1989; de Lara-Castells and Mitrushchenkov, 2020; de Lara-Castells and Mitrushchenkov, 2021). This approach allows an easy and quick evaluation of the pair interaction potential V2, with the basis set being obtained as a direct product of functions for the different coordinates. Sinc-DVR functions are conveniently employed for the t and χ coordinates. When dealing with the polar radii ρ, however, it is necessary to explicitly treat the singular kinetic energy term , which stems from the Jacobian transformation to cylindrical coordinates. For this purpose, we use the DVR basis obtained for the finite basis set representation (FBR) built from the radial functions of two-dimensional (2D) Harmonic oscillator functions. However, this basis renders the grid size too large for clusters with, e.g., 4 PNs since the internal Hamiltonian becomes 10-dimensional (10 D). This problem is efficiently solved by using potential-optimized DVR (PO-DVRs) functions (Echave and Clary, 1992), allowing for a very fast energy convergence as well. The diagonalization of the resulting Hamiltonian matrix is carried out using the Jacobi-Davidson algorithm (Sleijpen and van der Vorst, 1996). This technique has been very successful even for characterizing ill-behaved interactions such as, e.g., the “hard-core” interaction problem of doped helium clusters (de Lara-Castells et al., 2009a; de Lara-Castells et al., 2009b).

3 Illustrative Applications

In the first subsection, we will illustrate how the interaction of molecular hydrogen with various SWCNTs can be modelled at ab initio level. In the second subsection, we will show how our computational approach has allowed to reveal the transition from van-der-Waals-type molecular aggregation to quasi-1D condensed matter systems for atomic 4He and molecular H2 and D2 inside a SWCNT of 1 nm diameter.

3.1 H2-Nanotube Interaction Potentials for SWCNTs of Increasing Diameter

As an illustrative case, the top (left-hand) panel of Figure 1 shows the total H2/CNT interaction potential as a function of the radial distance r between the molecule center-of-mass and the SWCNT(5,5) center, along with the electrostatic Eelec, exchange-repulsion Eexch-rep, induction Eind, and dispersion contributions Edisp. Upon applying the pairwise PPM presented in Section 3.1, the radial scans of interaction energies shown in the upper (right-hand) panel of Figure 1 are obtained for SWCNTs of increasing diameter.

As can be observed in the top panel of Figure 1 (left-hand side), the H2/CNT attractive interaction is dispersion-dominated, with the exchange-repulsion dominating the whole dispersionless term. This repulsive energy contribution grows exponentially as the molecule-surface distance decreases although such behaviour is somewhat smoothed out by the attractive electrostatic contribution. The induction term contributes very little at the potential minimum but considerably at the SWCNT cage. The potential minimum is located at the center of the narrowest nanotube (diameter of 6.74 Å), where the adsorbates benefit from the dispersion interaction with carbon atoms at both sides of the carbon cage. However, upon increasing the nanotube diameter (see right-hand panel at the top of Figure 1), the dispersion becomes very small at the nanotube center and the potential minima shift towards the carbon cage. For a nanotube of diameter of 27.21 Å, the value of the well-depth (−56 meV) is already close to that obtained for a graphene sheet and measured for the H2 molecule adsorbed onto graphite (−51.7 meV from Ref. 29). From the top (left-hand side) panel of Figure 1 it can also be observed that the pairwise potential model closely reproduces the results obtained with the SAPT(DFT) method. Similar conclusions hold for the case of the He/SWCNT interaction (Hauser et al., 2017), also emphasizing the usefulness of the SAPT(DFT)-derived PPM (see Section 3.1).

3.2 From van-der-Waals Aggregation to Quasi-One-Dimensional Chains

Considering a SWCNT of 1 nm diameter and helicity index (11, 4), the He-SWCNT and H2-SWCNT one-particle potentials V1(ρ) are shown in the bottom (right-side) panels of Figure 1 along with a few supported bound states of a single 4He atom or H2 molecule. Figure 2 presents the plots of the ground-state two-dimensional (2D) densities of PN4 clusters (PN = 4He, para-H2, and ortho-D2).

FIGURE 2

Plot of 2D densities for the ground state of PN4 ⊂ SWCNT(11, 4) complexes. Left to right: PN = 4He, para-H2, ortho-D2. (A)t1 and t2 coordinates; (B)t1 and χ1 coordinates; (C)t1 and χ2 coordinates; (D)χ1 and χ2 coordinates. Source: (de Lara-Castells and Mitrushchenkov, 2021).

As previously reported (de Lara-Castells and Mitrushchenkov, 2020; de Lara-Castells and Mitrushchenkov, 2021) the structuring of PNN clusters, with N = 1 − 3, is characterized by a high pseudo-nuclear delocalization. Thus, the triangular-like structure exhibited by confined (4He)3 clusters (see graphical abstract) freely rotates inside the nanotube. However, as can be observed in Figure 2, whatever the bosonic particle be, the most probable structure is pyramidal-like. This confinement effect is specially remarkable for the case of 4He, due to the high delocalization of the bare PN–PN dimer (see bottom panel (d) of Figure 1). Yet, it features an increasing spatial delocalization when going from molecular ortho-D2 through molecular para-H2 to atomic 4He. Inspite of para-H2 molecules being twice as light as 4He atoms, the three times deeper attractive well of the pair potential (see bottom panels (a) and (b) of Figure 1) causes a much more compact structuring of the (para-H2)4 cluster when compared with the 4He counterpart. Particularly, we note that the extended profile of the 2D densities in the χ coordinates reflects a quasi-independent relative rotational motion of two (4He)2 dimers lying orthogonal to the tube axis. Since ortho-D2 molecules are twice as heavy as para-H2 molecules, the solid-like nature of the (ortho-D2)4 structure (a regular tetrahedron) becomes even more apparent than for the (para-H2)4 counterpart. The formation of (vibrationally averaged) tetrahedral structures of (para-H2)4 clusters is not a special effect from the SWCNT confinement. In fact, the same feature has also been revealed in clathrate hydrate cages (Sebastianelli et al., 2008; Witt et al., 2010). These similarities indicate that the aggregation of multiple light PNs are driven by quantum nuclear effects and very weak dispersive PN–PN interaction forces rather than the much more stronger PN–SWCNT (or PNT-cage) energy contribution (see bottom panels (a) and (b) of Figure 1). As discussed in detail in our previous work (de Lara-Castells and Mitrushchenkov, 2020), the onset of solid-like packing for molecular deuterium is explained by analyzing the potential minima landscape, allowing also to predict the formation of a one-dimensional chain of tetrahedral structures along the tube axis when the number of D2 molecules increase. Similar conclusions holds for the cases of 4He atoms and H2 molecules (de Lara-Castells and Mitrushchenkov, 2021). Moreover, these special structures feature stabilization of collective rotational motion resembling the behaviour of quantum rings exhibiting persistent current (charged particles) or persistent flow (neutral particles). This characteristic has been connected with the onset of superfluid motion and persistent flow in quantum rings made of 4He atoms by Bloch (Bloch, 1973). It is remarkable that such feature occurs already in clusters made of four 4He atoms at the reduced dimensionality offered by the confining medium.

4 Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

Summarizing, this mini review shows how a challenging case of confined molecular system can be accurately characterized using multi-scale first-principles modelling. In order to emphasize the key role of quantum effects, we have chosen the lightest atomic and molecular species in nature as the confined object and SWCNTs as the confining medium. In the first part, we have overviewed how an ab initio-derived pairwise potential model can accurately characterize the intermolecular interaction between the confining medium and the confined object. In the second part, we have illustrated how a computational approach, allowing for rigorous fully coupled quantum calculations of the pseudo-nuclear bound states, has been capable of revealing the transition from van der Waals-type molecular aggregation to quasi-1D condensed matter systems under cylindrical carbon nanotube confinement. Remarkably, it has been also shown that the structuring is driven by purely dispersive PN-PN interactions together with quantum pseudo-nuclear effects and not the much more stronger PN-tube interaction forces. In this way, it can be also understood why, inspite of its weak cohesive PN-PN interaction, neutron scattering experimental measurements have very recently shown the formation of quasi-one-dimensional structures of molecular D2 corresponding to cylindrical sections of the hexagonal close-packed bulk crystal (Cabrillo et al., 2021).

As a future perspective, we are aimed to adapt our Full Configuration Interaction Nuclear Orbital (FCI-NO) approach (de Lara-Castells et al., 2009b), originally developed for doped helium clusters, to the present case in which the carbon nanotube acts as the “dopant” species. The essential advantage of this ansatz is that the wave function is expanded using products of nuclear orbitals, allowing the employment of second quantization techniques, an automatic inclusion of Fermi–Dirac and Bose–Einstein nuclear spin statistical effects, and, then, a characterization of 3He and 4He isotopes on an equal footing. The second future prospect is the creation of embedding approaches linking our wave-function-based description with orbital free He-DFT (Dalfovo et al., 1995; Ancilotto et al., 2017), following previous efforts (Hauser et al., 2017). In this sense, the highly accurate method presented in our latest work (de Lara-Castells and Mitrushchenkov, 2021) is expected to provide benchmark results guiding new, machine-learning driven, parameterizations in He-DFT, as already illustrated in electronic structure theory (Meyer et al., 2020).

Statements

Author contributions

MPdLC and AOM have equally contributed to the conceptualization of this work, and the writing and edition of this manuscript.

Funding

This work has been partly supported by the Spanish Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER, UE) under Grant Nos. PID 2020-117605GB-I00 and MAT 2016-75354-P.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andreas W. Hauser Graz University of Technology and Ricardo Fernández-Perea IEM-CSIC, Spain for their previous and very fruitful collaboration on the topic of this mini review.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Ancilotto F. Barranco M. Coppens F. Eloranta J. Halberstadt N. Hernando A. et al (2017). Density Functional Theory of Doped Superfluid Liquid Helium and Nanodroplets. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem.36, 621–707. 10.1080/0144235X.2017.1351672

2

Bačić Z. Light J. C. (1989). Theoretical Methods for Rovibrational States of Floppy Molecules. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem.40, 469–498. 10.1146/annurev.pc.40.100189.002345

3

Bloch F. (1973). Superfluidity in a Ring. Phys. Rev. A.7, 2187–2191. 10.1103/PhysRevA.7.2187

4

Cabrillo C. Fernández-Perea R. Bermejo F. J. Chico L. Mondelli C. González M. A. et al (2021). Formation of One-Dimensional Quantum Crystals of Molecular Deuterium inside Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon175, 141–154. 10.1016/j.carbon.2020.12.067

5

Carlos W. E. Cole M. W. (1980). Interaction between a He Atom and a Graphite Surface. Surf. Sci.91, 339–357. 10.1016/0039-6028(80)90090-4

6

Cazorla C. Boronat J. (2017). Simulation and Understanding of Atomic and Molecular Quantum Crystals. Rev. Mod. Phys.89, 035003. 10.1103/RevModPhys.89.035003

7

Cheng H.-M. Yang Q.-H. Liu C. (2001). Hydrogen Storage in Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon39, 1447–1454. 10.1016/s0008-6223(00)00306-7

8

Dalfovo F. Lastri A. Pricaupenko L. Stringari S. Treiner J. (1995). Structural and Dynamical Properties of Superfluid Helium: A Density-Functional Approach. Phys. Rev. B52, 1193–1209. 10.1103/PhysRevB.52.1193

9

Deb J. Bhattacharya B. Paul D. Sarkar U. (2016). Interaction of Nitrogen Molecule with Pristine and Doped Graphyne Nanotube. Phys. E84, 330–339. 10.1016/j.physe.2016.08.006

10

Deb J. Paul D. Sarkar U. (2019). Donor-acceptor Decorated Graphyne: A Promising Candidate for Nonlinear Optical Application. Dae Solid State Phys. Symp.10.1063/1.5113008

11

de Lara-Castells M. P. Bartolomei M. Mitrushchenkov A. O. Stoll H. (2015). Transferability and Accuracy by Combining Dispersionless Density Functional and Incremental post-Hartree-Fock Theories: Noble Gases Adsorption on Coronene/Graphene/Graphite Surfaces. J. Chem. Phys.143, 194701. 10.1063/1.4935511

12

de Lara-Castells M. P. Fernández-Perea R. Madzharova F. Voloshina E. (2016). Post-Hartree-Fock Studies of the He/Mg(0001) Interaction: Anti-corrugation, Screening, and Pairwise Additivity. J. Chem. Phys.144, 244707. 10.1063/1.4954772

13

de Lara-Castells M. P. Hauser A. W. Mitrushchenkov A. O. Fernández-Perea R. (2017). Quantum Confinement of Molecular Deuterium Clusters in Carbon Nanotubes: Ab Initio Evidence for Hexagonal Close Packing. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.19, 28621–28629. 10.1039/C7CP05869A

14

de Lara-Castells M. P. Hauser A. W. (2020). New Tools for the Astrochemist: Multi-Scale Computational Modelling and Helium Droplet-Based Spectroscopy. Phys. Life Rev.32, 95–98. 10.1016/j.plrev.2019.08.001

15

de Lara-Castells M. P. Mitrushchenkov A. O. (2021). A Nuclear Spin and Spatial Symmetry-Adapted Full Quantum Method for Light Particles inside Carbon Nanotubes: Clusters of 3He, 4He, and Para-H2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.23, 7908–7918. 10.1039/d0cp05332e

16

de Lara-Castells M. P. Mitrushchenkov A. O. Delgado-Barrio G. Villarreal P. (2009a). Using a Jacobi-Davidson "Nuclear Orbital" Method for Small Doped 3He Clusters. Few-body Syst.45, 233–236. 10.1007/s00601-009-0035-6

17

de Lara-Castells M. P. Mitrushchenkov A. O. (2020). From Molecular Aggregation to a One-Dimensional Quantum crystal of Deuterium inside a Carbon Nanotube of 1 nm Diameter. J. Phys. Chem. Lett.11, 5081–5086. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c01432

18

de Lara-Castells M. P. Stoll H. Civalleri B. Causà M. Voloshina E. Mitrushchenkov A. O. et al (2014a). Communication: A Combined Periodic Density Functional and Incremental Wave-Function-Based Approach for the Dispersion-Accounting Time-Resolved Dynamics of 4He Nanodroplets on Surfaces: 4He/Graphene. J. Chem. Phys.141, 151102. 10.1063/1.4898430

19

de Lara-Castells M. P. Stoll H. Mitrushchenkov A. O. (2014b). Assessing the Performance of Dispersionless and Dispersion-Accounting Methods: Helium Interaction with Cluster Models of the TiO2(110) Surface. J. Phys. Chem. A.118, 6367–6384. 10.1021/jp412765t

20

de Lara-Castells M. P. Villarreal P. Delgado-Barrio G. Mitrushchenkov A. O. (2009b). An Optimized Full-Configuration-Interaction Nuclear Orbital Approach to a "Hard-Core" Interaction Problem: Application to (3HeN)-Cl2(B) Clusters (N≤4). J. Chem. Phys.131, 194101. 10.1063/1.3263016

21

Del Maestro A. Boninsegni M. (2017). Absence of Superfluidity in a Quasi-One-Dimensional Parahydrogen Fluid Adsorbed inside Carbon Nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B95, 054517. 10.1103/PhysRevB.95.054517

22

Echave J. Clary D. C. (1992). Potential Optimized Discrete Variable Representation. Chem. Phys. Lett.190, 225–230. 10.1016/0009-2614(92)85330-D

23

Ferré G. Gordillo M. C. Boronat J. (2017). Luttinger parameter of quasi-one-dimensional para−H2. Phys. Rev. B95, 064502. 10.1103/PhysRevB.95.064502

24

Sleijpen G. L. van der Vorst H. A. (1996). A Jacobi-Davidson Iteration Method for Linear Eigenvalue Problems. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl.17, 401–425. 10.1137/s0895479894270427

25

Hauser A. W. de Lara-Castells M. P. (2016). Carbon Nanotubes Immersed in Superfluid Helium: The Impact of Quantum Confinement on Wetting and Capillary Action. J. Phys. Chem. Lett.7, 4929–4935. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b02414

26

Hauser A. W. de Lara-Castells M. P. (2017). Spatial Quenching of a Molecular Charge-Transfer Process in a Quantum Fluid: the Csx-C60 Reaction in Superfluid Helium Nanodroplets. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.19, 1342–1351. 10.1039/C6CP06858H

27

Hauser A. W. Mitrushchenkov A. O. de Lara-Castells M. P. (2017). Quantum Nuclear Motion of Helium and Molecular Nitrogen Clusters in Carbon Nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. C121, 3807–3821. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b12959

28

Hesselmann A. Jansen G. (2003). Intermolecular Dispersion Energies from Time-dependent Density Functional Theory. Chem. Phys. Lett.367, 778–784. 10.1016/S0009-2614(02)01796-7

29

Heßelmann A. Jansen G. Schütz M. (2005). Density-functional Theory-Symmetry-Adapted Intermolecular Perturbation Theory with Density Fitting: A New Efficient Method to Study Intermolecular Interaction Energies. J. Chem. Phys.122, 014103. 10.1063/1.1824898

30

Liu C. Chen Y. Wu C.-Z. Xu S.-T. Cheng H.-M. (2010). Hydrogen Storage in Carbon Nanotubes Revisited. Carbon48, 452–455. 10.1016/j.carbon.2009.09.060

31

Mattera L. Rosatelli F. Salvo C. Tommasini F. Valbusa U. Vidali G. (1980). Selective Adsorption of 1H2 and 2H2 on the (0001) Graphite Surface. Surf. Sci.93, 515–525. 10.1016/0039-6028(80)90279-4

32

Meyer R. Weichselbaum M. Hauser A. W. (2020). Machine Learning Approaches toward Orbital-free Density Functional Theory: Simultaneous Training on the Kinetic Energy Density Functional and its Functional Derivative. J. Chem. Theor. Comput.16, 5685–5694. 10.1021/acs.jctc.0c00580

33

Misquitta A. J. Jeziorski B. Szalewicz K. (2003). Dispersion Energy from Density-Functional Theory Description of Monomers. Phys. Rev. Lett.91, 033201. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.033201

34

Misquitta A. J. Podeszwa R. Jeziorski B. Szalewicz K. (2005). Intermolecular Potentials Based on Symmetry-Adapted Perturbation Theory with Dispersion Energies from Time-dependent Density-Functional Calculations. J. Chem. Phys.123, 214103. 10.1063/1.2135288

35

Mondelo-Martell M. Huarte-Larrañaga F. (2021). Competition of Quantum Effects in H2/D2 Sieving in Narrow Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes. Mol. Phys.119, e1942277. 10.1080/00268976.2021.1942277

36

Mondelo-Martell M. Huarte-Larrañaga F. (2016). Diffusion of H2 and D2 Confined in Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes: Quantum Dynamics and Confinement Effects. J. Phys. Chem. A.120, 6501–6512. 10.1021/acs.jpca.6b00467

37

Mondelo-Martell M. Huarte-Larrañaga F. Manthe U. (2017). Quantum Dynamics of H2 in a Carbon Nanotube: Separation of Time Scales and Resonance Enhanced Tunneling. J. Chem. Phys.147, 084103. 10.1063/1.4995550

38

Mudrich M. Stienkemeier F. (2014). Photoionisaton of Pure and Doped Helium Nanodroplets. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem.33, 301–339. 10.1080/0144235X.2014.937188

39

Nguyen T. X. Jobic H. Bhatia S. K. (2010). Microscopic Observation of Kinetic Molecular Sieving of Hydrogen Isotopes in a Nanoporous Material. Phys. Rev. Lett.105, 085901. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.085901

40

Noury A. Vergara-Cruz J. Morfin P. Plaçais B. Gordillo M. C. Boronat J. et al (2019). Layering Transition in Superfluid Helium Adsorbed on a Carbon Nanotube Mechanical Resonator. Phys. Rev. Lett.122. 10.1103/physrevlett.122.165301

41

Ohba T. (2016). Limited Quantum Helium Transportation through Nano-Channels by Quantum Fluctuation. Sci. Rep.6. 10.1038/srep28992

42

Paul D. Deb J. Sarkar U. (2019). Influence of Noble Gas Atoms on B12N12 Fullerene: A DFT Study. Dae Solid State Phys. Symp. 10.1063/1.5113010

43

Paul D. Dua H. Sarkar U. (2020). Confinement Effects of a Noble Gas Dimer inside a Fullerene Cage: Can it Be Used as an Acceptor in a DSSC?. Front. Chem.8. 10.3389/fchem.2020.00621

44

Perdew J. P. Burke K. Ernzerhof M. (1996). Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett.77, 3865–3868. 10.1103/physrevlett.77.3865

45

Pernal K. Podeszwa R. Patkowski K. Szalewicz K. (2009). Dispersionless Density Functional Theory. Phys. Rev. Lett.103, 263201. 10.1103/physrevlett.103.263201

46

Rosi N. L. Eckert J. Eddaoudi M. Vodak D. T. Kim J. O'Keeffe M. et al (2003). Hydrogen Storage in Microporous Metal-Organic Frameworks. Science300, 1127–1129. 10.1126/science.1083440

47

Rossi M. Ancilotto F. (2016). Superfluid Behavior of Quasi-One-dimensionalp−H2 inside a Carbon Nanotube. Phys. Rev. B94, 100502. 10.1103/PhysRevB.94.100502

48

Schlapbach L. Züttel A. (2001). Hydrogen-Storage Materials for Mobile Applications. Nature414, 353–358. 10.1038/35104634

49

Sebastianelli F. Xu M. Bačić Z. (2008). Quantum Dynamics of Small H2 and D2 Clusters in the Large Cage of Structure II Clathrate Hydrate: Energetics, Occupancy, and Vibrationally Averaged Cluster Structures. J. Chem. Phys.129, 244706. 10.1063/1.3049781

50

Stoll H. (1992). On the Correlation Energy of Graphite. J. Chem. Phys.97, 8449–8454. 10.1063/1.463415

51

Tang K. T. Toennies J. P. (1984). An Improved Simple Model for the Van Der Waals Potential Based on Universal Damping Functions for the Dispersion Coefficients. J. Chem. Phys.80, 3726–3741. 10.1063/1.447150

52

Ting V. P. Ramirez-Cuesta A. J. Bimbo N. Sharpe J. E. Noguera-Diaz A. Presser V. et al (2015). Direct Evidence for Solid-like Hydrogen in a Nanoporous Carbon Hydrogen Storage Material at Supercritical Temperatures. ACS Nano9, 8249–8254. 10.1021/acsnano.5b02623.PMID:26171656

53

Toennies J. P. Vilesov A. F. (2004). Superfluid Helium Droplets: A Uniquely Cold Nanomatrix for Molecules and Molecular Complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.43, 2622–2648. 10.1002/anie.200300611

54

Werner H. J. Knowles P. J. Knizia G. Manby F. R. Schütz M. Celani P. et al (2012). Molpro, Version 2012.1, a Package of Ab Initio Programs, See Available at: http://www.molpro.net [Dataset].

55

Witt A. Sebastianelli F. Tuckerman M. E. Bačić Z. (2010). Path Integral Molecular Dynamics Study of Small H2 Clusters in the Large Cage of Structure II Clathrate Hydrate: Temperature Dependence of Quantum Spatial Distributions. J. Phys. Chem. C114, 20775–20782. 10.1021/jp107021t

56

Woon D. E. Dunning Jr. Dunning T. H. (1994). Gaussian Basis Sets for Use in Correlated Molecular Calculations. IV. Calculation of Static Electrical Response Properties. J. Chem. Phys.100, 2975–2988. 10.1063/1.466439

57

Zheng J. Wang C.-G. Zhou H. Ye E. Xu J. Li Z. et al (2021). Current Research Trends and Perspectives on Solid-State Nanomaterials in Hydrogen Storage. Research. 10.34133/2021/3750689

58

Züttel A. (2003). Materials for Hydrogen Storage. Mater. Today6, 24–33. 10.1016/S1369-7021(03)00922-2

Summary

Keywords

clusters of molecular hydrogen, clusters of atomic helium, carbon nanotubes, quantum confinement, ab initio intermolecular interaction theory, wave-function method for bound-state calculations, full quantum coupled characterizations

Citation

de Lara-Castells MP and Mitrushchenkov AO (2021) Mini Review: Quantum Confinement of Atomic and Molecular Clusters in Carbon Nanotubes. Front. Chem. 9:796890. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.796890

Received

17 October 2021

Accepted

08 November 2021

Published

08 December 2021

Volume

9 - 2021

Edited by

Heribert Reis, National Hellenic Research Foundation, Greece

Reviewed by

Utpal Sarkar, Assam University, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2021 de Lara-Castells and Mitrushchenkov.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: María Pilar de Lara-Castells, Pilar.deLara.Castells@csic.es; Alexander O. Mitrushchenkov, Alexander.Mitrushchenkov@univ-eiffel.fr

This article was submitted to Theoretical and Computational Chemistry, a section of the journal Frontiers in Chemistry

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.