Abstract

Based on the successful fabrication of PdSe2 monolayers, the electronic and thermoelectric properties of pentagonal PdX2 (X = Se, Te) monolayers were investigated via first-principles calculations and the Boltzmann transport theory. The results showed that the PdX2 monolayer exhibits an indirect bandgap at the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof level, as well as electronic and thermoelectric anisotropy in the transmission directions. In the PdTe2 monolayer, P-doping owing to weak electron–phonon coupling is the main reason for the excellent electronic properties of the material. The low phonon velocity and short phonon lifetime decreased the thermal conductivity (κl) of penta-PdTe2. In particular, the thermal conductivity of PdTe2 along the x and y transmission directions was 0.41 and 0.83 Wm−1K−1, respectively. Owing to the anisotropy of κl and electronic structures along the transmission direction of PdX2, an anisotropic thermoelectric quality factor ZT appeared in PdX2. The excellent electronic properties and low lattice thermal conductivity (κl) achieved a high ZT of the penta-PdTe2 monolayer, whereas the maximum ZT of the p- and n-type PdTe2 reached 6.6 and 4.4, respectively. Thus, the results indicate PdTe2 as a promising thermoelectric candidate.

1 Introduction

Currently, the energy crisis is the greatest challenge facing the world today, and requires the rapid acquisition of technological alternatives to traditional energy sources (Tan et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2018). Based on the Seebeck and Peltier effects, thermoelectric materials can convert thermal and electrical energy, thereby providing an initial solution to address this problem (He and Tritt, 2017). We use the thermoelectric quality factor ZT (Zhao et al., 2016; Snyder and Snyder, 2017) to measure the conversion efficiency of a thermoelectric material, expressed as:where S, σ, T, and κ are the Seebeck coefficient, electrical conductivity, absolute temperature, and thermal conductivity, respectively. The overall thermal conductivity (κ) is generated by the combined effect of the lattice (κl) and electronic (κe) thermal conductivity. Thus, a material with excellent electrical heating should achieve exceptional electrical properties [high Seebeck coefficient S, electronic conductivity σ, and power factor (PF) = S2σ] and thermal properties (low thermal conductivity κ). In addition, electrical conductivity is counter-correlated to S and directly proportional to κe (Jonson and Mahan, 1980), demonstrating the tradeoff in thermoelectric materials with a good ZT.

Low-dimensional materials can achieve local quantum pegging and polarization owing to the changes in their coordination environment and, thus, work well as thermoelectric materials (Dresselhaus et al., 2007). In particular, two-dimensional (2D) materials (Buscema et al., 2013; Kumar and Schwingenschlogl, 2015; Hong et al., 2016a; Gu et al., 2016; Yoshida et al., 2016; Hippalgaonkar et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019), especially transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) (Hippalgaonkar et al., 2017; Marfoua and Hong, 2019; Ding et al., 2020; Patel et al., 2020; Tao et al., 2020; Bilc et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021), have garnered extensive attention owing to their thermoelectric properties. TMDs exhibit various crystal structures, mainly the H (p-6 m2) and T (p-3m1) phases, which are experimentally found to have good thermal conductivity and low ZT (Yan et al., 2014; Hong et al., 2016b; Ma et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017). After the discovery of pentagonal graphene (Zhang et al., 2015), the low symmetry of the pentagonal composition has elevated the study of 2D electrothermal materials, such as pentagonal Y2N4 (Y = Pd, Ni or Pt), pentagonal Y2C (Y = Sb, As, P) and pentasilene (Tian et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2018a; Naseri et al., 2018; Gao et al., 2019; Gao and Wang, 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021). The discovery of the good structural stability and high carrier mobility of monoclinic pentagonal PdS2 by Wang et al. (2015) led researchers to conduct extensive studies on the various properties and potential applications of pentaco-MY2 (M = Pd, Pt; Y = Te, Se ) (Oyedele et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2018; Lan et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2020; Raval et al., 2021; Tao et al., 2021). Lan et al. (2019) demonstrated that the κl along the x-(y-) transport direction for PdTe2, PdSe2, and PdS2 are 1.42 (5.90), 2.91 (6.62), and 4.34 (12.48) Wm−1K−1, respectively. The maximum p-type ZT of penta-PdX2 (X = S, Se, Te) along the x-direction are 0.85, 1.18, and 2.42, respectively, demonstrating the potential of penta-PdX2 monolayers as thermoelectric materials. However, penta-PdTe2 monolayers have not yet been synthesized experimentally. In particular, although several studies have investigated the thermoelectric properties of pristine penta-PdX2, the conclusion are conflicting, and the principal discussions are controversial. Therefore, a systematic and detailed investigation should be conducted on the electronic and thermoelectric properties of pristine penta-PdX2 (X = Se, Te).

In this study, we systematically investigated the electronic and thermoelectric transport properties of monolayer pentagonal PdSe2 and PdTe2 by combining first-principles calculations and the Boltzmann transport theory. PdX2 exhibited the characteristics of an indirect bandgap semiconductor. The results show that the thermoelectric performance parameters of the penta-PdX2 (X = Se, Te) monolayers, such as thermal conductivity, relaxation time, carrier mobility, and ZT, show strong anisotropy in the x and y directions due to their specific structural characteristics. Compared with PdSe2, the heavier atomic mass and weaker chemical bonds of PdTe2 achieved a lower κl and higher ZT.

2 Computational details

All calculations were performed based on the density functional theory with the projector-augmented plane wave method used in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) (Blöchl, 1994; Kresse and Furthmüller, 1996). The electron exchange-correlation energy was described by GGA-PBE (Perdew et al., 1996) and the cut-off energy was set to 500 eV (Monkhorst and Pack, 1976). The structural optimization was performed until the energy change per atom was less than 10–5 eV, the forces on atoms were less than 10–4 eV Å−1, all the stress components were less than 0.02 GPa, and there was a maximum displacement of . The k-point meshes were set as 12 × 11 × 1 to ensure the energy convergence. We took a 20 Å thick vacuum slab insertion to model the periodic structure of the monolayers. We used the Boltzmann transport equation based on the relaxation time approximation to calculate the thermoelectric transport coefficients (Madsen and Singh, 2006).

κ l is mainly dominated by anharmonic phonon–phonon scattering. According to the Boltzmann–Peierls theory and the relaxation time approximation, κl is computed by (Yue et al., 2022):where Nq is the number of wave vectors, Ω is the unit cell volume, α and β are Cartesian coordinate directions, Cq,j is the specific heat capacity of the jth phonon branch at the crystal momentum q, υq,j is the phonon group velocity obtained from the harmonic phonon frequency, and τq,j is the phonon lifetime. The harmonic phonon frequency was calculated by constructing a 4 × 4 × 1 supercell based on the finite displacement method, as implemented in the Phonopy package (Togo et al., 2008). The anharmonic third-order interatomic force constants (3rd-IFCs) were computed by constructing a 4 × 4 × 1 supercell with the cutoff value of the fifth nearest neighbor. By combining the 2nd-IFCs and 3rd-IFCs, κl was obtained through the ShengBTE code (Li et al., 2014).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Structural models and electronic properties

The penta-PdX2 monolayer with the P21/c space group (No. 14) consists entirely of pentagons. The schematic crystal structures of pentagonal PdX2 (X = Se, Te) are shown in Figure 1A. The diagram shows that the Pd atom is linked to four X-atoms, and that the adjacent X-atoms are connected to each other to form an anisotropic pentagonal structure. The anisotropy of pentagonal structure determines the anisotropy of the electron and transport properties. After structural optimization, the lattice parameter a (b) of penta-PdSe2 and penta-PdTe2 are 5.71 (5.90) and 6.14 (6.44) Å, respectively, which are consistent with previous theoretical calculations (Bardeen and Shockley, 1950) (see Table 1).

FIGURE 1

(A) Schematic of the top and side view of the penta-PdSe2 monolayer; the unit cells are marked by the black line. (B) Band structure of the PdSe2 and (C) PdTe2 monolayers. The horizontal line indicates the Fermi level. The high symmetry k points are: Γ(0 0 0), X (0.5 0 0), M (0.5 0.5 0), Y (0 0.5 0), and S (0.39 0.5 0).

TABLE 1

| Materials | a (Å) | b (Å) | h (Å) | PdSe(Te) (Å) | Eg (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PdSe2 | 5.71 | 5.90 | 1.52 | 2.46 | 1.31 |

| PdTe2 | 6.14 | 6.44 | 1.70 | 2.63 | 1.26 |

Lattice parameters (a ,b), the thickness of monolayer materials (h), and bandgap (Eg) at the PBE level.

To determine the electronic properties of the PdSe2 and PdTe2 monolayers, we calculated the respective energy band structures and electronic density of states (DOS), as shown in Figure 1, Supplementary Figure S1 of the Supporting Information (SI). All materials exhibited semiconducting band structures with indirect bandgaps for the penta-PdSe2 (1.31 eV) and PdTe2 (1.26 eV) monolayers. Combined with the partial DOS (Supplementary Figure S1 of SI), the conduction and valence bands were mainly composed of Pd_d and X_p orbitals. In penta-PdSe2, the valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM) occurred in the Γ-X and Γ-S paths, respectively, as shown in Figure 1B. In penta-PdTe2, the CBM values were close to the degenerate minima in the Γ-Y and Γ-X paths with a difference of 2 meV only.

3.2 Electronic transport properties

The carrier mobility can be calculated using the deformation potential theory, which is based on the electron–acoustic phonon scattering mechanism, and can be expressed as follows (Bardeen and Shockley, 1950):where ħ, kB, T, and m* are the reduced Planck constant, Boltzmann constant, temperature, and effective mass along the transport direction, respectively. md is the average effective mass, decided by the effective masses along the x and y transport directions. C2D represent the elastic modulus, which can be expressed as , where E, l, l0, and S0 are the total energy, lattice constant after and before deformation, and area of the unit cell, respectively. By fitting the band-edge curve, we can obtained the deformation potential constant El.

The parameters calculated at 300 K are listed in Table 2 and include the effective mass neutrality, the elastic modulus, the deformation potential and the carrier mobility. As Table 2 shows, the anisotropy of the PdSe2 and PdTe2 structures causes them to exhibit anisotropy in all of the above parameters. In the x-direction, the effective mass of the holes was smaller than that of the electrons, particularly for the PdSe2 monolayers, which is in good agreement with their dispersive band structures (Figure 1). In the y-direction, the effective mass of the electrons (0.51) of PdSe2 was smaller than that of the holes (1.41), whereas the opposite results were found in the PdTe2 monolayers. The deformation potential of the holes in the monolayer materials was smaller than that of the electrons in both directions, which reflects the lower scattering rate due to the hole–acoustic phonon interaction and larger carrier mobility. As listed in Table 1, the penta-PdX2 monolayer exhibited high hole mobility at 300 K. For p-type doping, the small potential constant along the y transport direction indicates high hole mobility. The hole mobilities along the x(y) directions were 620 (1230) and 1063 (1817) cm2 V−1 s−1 for the PdSe2 and PdTe2 monolayers, respectively which mark them as showing a great advantage in electron transport.

TABLE 2

| Carrier | D | C2D | El | m* | md | μ | τ(fs) | θ D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PdSe2 | h | x | 2.34 | 1.22 | 0.81 | 1.07 | 619.88 | 285.86 | 63 |

| y | 3.83 | 0.84 | 1.41 | 1.07 | 1229.46 | 986.97 | |||

| e | x | 2.34 | 3.32 | 14.68 | 2.74 | 1.80 | 15.07 | ||

| y | 3.83 | 3.73 | 0.51 | 2.74 | 67.32 | 19.55 | |||

| PdTe2 | h | x | 1.44 | 1.01 | 0.54 | 0.84 | 1063.47 | 326.95 | 45 |

| y | 3.18 | 0.74 | 1.30 | 0.84 | 1817.26 | 1345.03 | |||

| e | x | 1.44 | 2.09 | 0.87 | 1.12 | 115.61 | 57.27 | ||

| y | 3.18 | 1.80 | 1.44 | 1.12 | 207.96 | 170.49 |

Calculated deformation potential (El), elastic constant (C2D), effective mass of carrier (m*), average effective mass (md), carrier mobility (μ), relaxation time (τ) of the electron (e) and hole (h) along different directions (D) at 300 K, and average Debye temperatureθD (K).

The relaxation time can be obtained using the following equation:

The temperature-dependent relaxation times of electrons and holes along the x and y transport directions is shown in Figure 2. In agreement with our predictions, the relaxation times also exhibit significant anisotropy, and the holes lifetime (Figure 2A) was significantly longer than that of the electrons because of the weaker hole phonon scattering (Figure 2B). The results demonstrated that the individual anisotropy of the relaxation times was mainly due to differences in the effective masses in x and y transport directions. Among all p-type candidates, The PbTe2 monolayer had the largest amount of relaxation time variation with temperature along the y-direction, which is mainly due to the smallest potential constant El and average effective mass m* at the VBM.

FIGURE 2

Relaxation time of the (A) holes and (B) electrons of the PdSe2 and PdTe2 monolayer along the x and y transport directions.

The calculated S and σ/τ along the x and y transport directions at 300 K as functions of the carrier concentration (n) of the PdSe2 and PdTe2 monolayer are plotted in Supplementary Figures S2, S3 of SI, respectively. With increasing n, S decreased while σ/τ increased. The transmission coefficients S and σ can be treated with the degenerate-doped single parabolic model, where S and σ were expressed as:

In the single parabolic band, S decreased as n increased, whereas linearly increased with n. Compared with p-type doping (Figure 3A), the S of n-type doping was higher for a fixed n (1013 cm−2). This is because the electron effective mass lies at the edge of conduction band. The isoenergy surfaces enabled analysis of the shape of the electron band. The isoenergy surfaces of the PdX2 monolayer were plotted (Figure 4), and the results suggested that a single pocket appear only in the Γ-X path for p-type doping, whereas multiple degenerate isoenergy pockets occurs for n-type doping. These results are consistent with previous reports on the significant enhancement of S owing to multiple degenerate bands at the band extrema (Xing et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2021). In p-type doping, the two-pocket properties (Figure 1C) increased S for PdTe2 in penta-PdX2 at room temperature. S decreased from PdSe2 to PdTe2 at temperatures above 600 K, which can be ascribed to the dual polarization effect caused by the reduced bandgap. Meanwhile, a larger hole’s effective mass increased S along the y-direction for the PdSe2 and PdTe2 monolayers. The electrical conductivity during the relaxation time is inversely proportional to S, (as shown in Figure 3A and C) of the SI. In addition, the higher carrier pocket degeneracy and effective mass favor a higher S for n-type doping. Among them, n-type doped PdTe2 obtained the largest S in the x- or y-direction.

FIGURE 3

(A,C) Calculated Seebeck coefficient of penta-PdSe2 and penta-PdTe2 as a function of temperature and electrical conductivity. (B,D) Function of the carrier concentration at 300 K along the x and y directions under p-type (top panels) and n-type (bottom panels) doping.

FIGURE 4

Constant energy surface of (A) penta-PdSe2 and (B) penta-PdTe2. The top images denote the highest valence with the energy of 0.1 eV less than the VBM, and the bottom images denote the lowest conduction band with the energy of 0.1 eV more than the CBM.

Electrical conductivity was determined based on the relaxation time τ. Figures 3B,D show the electrical conductivities of the PdSe2 and PdTe2 monolayers at 300 K in p-type and n-type doping. The p-type electrical conductivity was higher than the n-type electrical conductivity because of the higher carrier mobility and longer carrier lifetime. In p-type doping, the electrical conductivity along the y-direction was larger than that along the x-direction, although the effective mass of the holes in the y-direction was higher. Similar behavior was observed for n-type doping. This trend is mainly attributed to the significantly larger elastic constant in the y-direction, which increased τ in all temperature ranges.

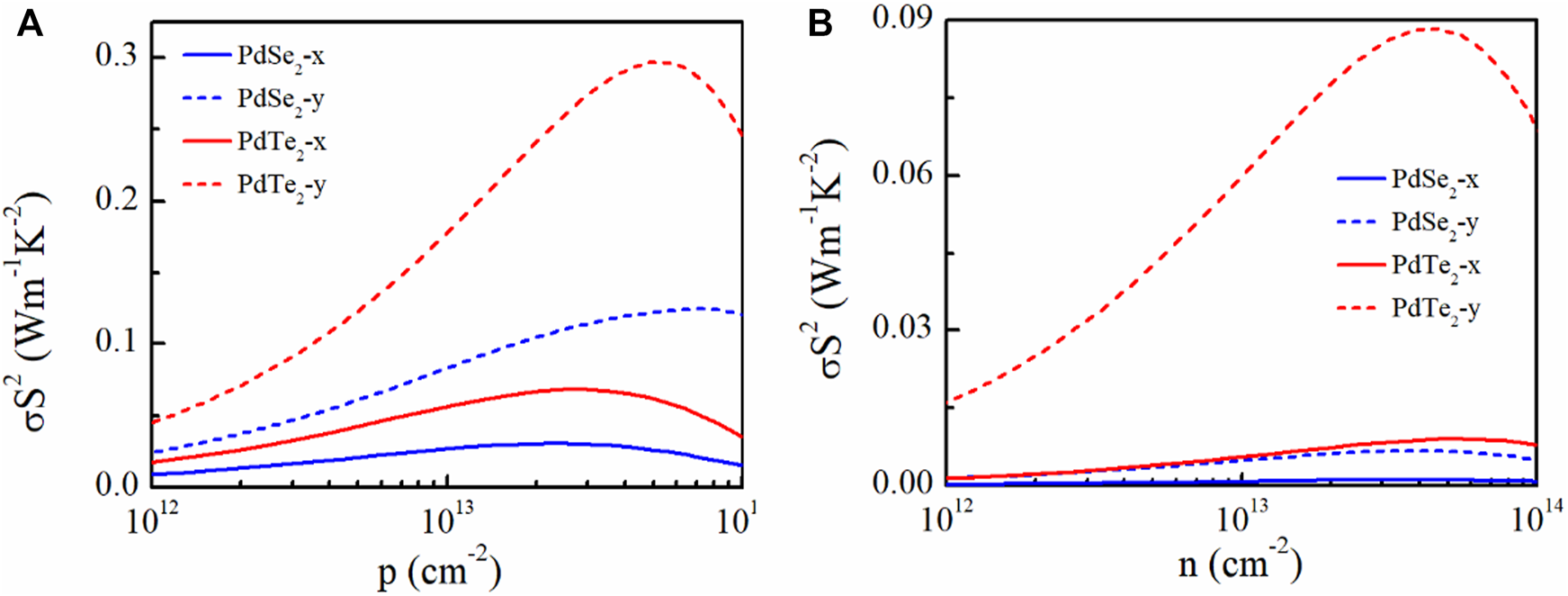

PF is used to evaluate the ability of a material to convert electrical energy. The determined PF in this study is plotted in Figure 5. A higher electrical conductivity combined with a suitable S achieved a higher PF for p-type doping. In particular, for PdTe2, the highest PF during p-type and n-type doping at 300 K reached 300 mWmK−2 along the y-direction (Figure 5A) and 90 mW mK−2 (Figure 5B), respectively.

FIGURE 5

Calculated (A)p-type and (B)n-type power factor (σS2) of penta-PdSe2 and penta-PdTe2 as a function of the carrier concentration at 300 K along the x- (solid lines) and y- (dotted lines) directions.

3.3 Thermal transport properties

We analyzed the thermal transport properties of the PdX2 (X = Se, Te) monolayer based on the harmonic and anharmonic effects. Phonon spectra were obtained from the harmonic interatomic force constants, as shown in Supplementary Figure S4 of SI. Heavier elements and a small force constant have lower vibration frequency. The maximum phonon vibrational frequency gradually decreased from the PdSe2 to PdTe2 monolayers, indicating the suppressed phonon vibrations and shift of the optical branches toward lower energies, thereby achieving strong interactions between the phonon modes and decreasing κl. Using the harmonic (2nd) and anharmonic (3rd) interatomic force constants, κl of the PdSe2 and PdTe2 monolayers were obtained, as shown in Figure 6A. In general, κl decreased with increasing temperature owing to the low-frequency phonons (Figure 6B) and demonstrate anisotropy along different directions. At 300 K, the calculated κl was 3.99 (10.58) and 0.41 (0.83) W m−1K−1 for PdSe2 and PdTe2, respectively, along the x(y) transport directions. These results are comparable to other thermoelectric materials with superior thermoelectric properties, such as monolayer SnSe (3 Wm−1K−1) (Zhang et al., 2016), bulk SnSe (0.62 Wm−1K−1) (Xiao et al., 2016), Ge4Se3Te (1.6 Wm−1K−1) (Huang et al., 2021), silicene (2.86 Wm−1K−1) (Peng et al., 2016), germanene (2.4 Wm−1K−1) (Peng et al., 2017), and GeSe (2.63 Wm−1K−1) (Liu et al., 2018b). Therefore, κe is a vital factor in the ZT evaluation owing to the low κl.

FIGURE 6

(A) Lattice thermal conductivity as a function of temperature, (B) phonon contributions toward the total lattice thermal conductivity, (C) phonon velocity, and (D) phonon lifetime of the penta-PdSe2 and penta-PdTe2 monolayers.

To analyze κl, we obtained the phonon group velocity and lifetime. The lower thermal conductivity is mainly attributed to the decreasing phonon velocity from PdSe2 to PdTe2, as shown in Figure 6C. Compared to the PdSe2 monolayer, the PdTe2 monolayer exhibited a shorter phonon lifetime, as shown in Figure 6D, indicating that the PdTe2 monolayer exhibits a considerably higher scattering rate and anharmonic feature, which can also be obtained from the phonon spectra. The scattering probability of the emission and absorption processes can be described by the frequency-dependent scattering phase space. The scattering phase spaces of the emission and absorption processes at 300 K are shown in Supplementary Figure S5 in the SI. The suppressed phonons increased the scattering phase space and enhanced the anharmonic feature, resulting in decreased thermal conductivity from PdSe2 to PdTe2 in the low-frequency region.

To further analyze the anharmonic feature, the difference in the charge density was computed as:where , , and are the total charge density, charge density of the metal atoms, and chalcogen atoms, respectively. Lower charge density was accumulated on the Pd–Te bonds of PdTe2, compared to PdSe2, suggesting that penta-PdTe2 was significantly softer than PdSe2 with a strong anharmonic effect, as shown in Figure 7. Furthermore, the average acoustic Debye temperature (θD) was evaluated using the formula:where θi (i = ZA, TA, LA) is obtained by , where h, kB, and vi,max are the Planck constant, Boltzmann constant, and the maximal phonon frequency of the ith acoustic phonon mode, respectively. The θD values of the PdSe2 and PdTe2 monolayers were 63 and 45 K, respectively. The low Debye temperature is due to the weak interatomic bonding of the PdTe2 monolayer, which suggested more phonons could participate in the scattering process, thereby reducing κl.

FIGURE 7

Difference of the charge density of the (A) penta-PdSe2 and (B) penta-PdTe2 monolayers, respectively. The red and green regions denote the charge accumulation and depletion, respectively. The charge density isosurfaces were set to 0.05 eÅ−3.

3.4 Quality factor

The dimensionless thermoelectric ZT was analyzed. κe was calculated using the Wiedemann–Franz law (Jonson and Mahan, 1980):where L is the Lorenza number (L = 2.45 × 10–8 WΩK−2). κe of the PdSe2 and PdTe2 monolayers at 300 K are shown in Supplementary Figure S6 of the SI, which was similar to κl. κe in the y-direction was larger than that in the x-direction owing to the high electronic conductivity in the y-direction. The larger κe and κl in the y-direction also prove that the thermoelectric properties were worse along the y-direction than along the x-direction.

The ZT values for p- and n-type doping of the monolayer materials at 300 K along the x and y directions are plotted in Figure 8. The ZT values of the p-type-doped PdSe2 and PdTe2 monolayers were larger than those with n-type doping because of the higher electronic conductivity. Owing to the smaller κl and higher PF, the PdTe2 monolayer obtained the largest ZT values, regardless of the doping type. In particular, the calculated ZT of the p-type- and n-type-doped PdTe2 monolayers along the x- (y-) direction were 5.2 (6.6) and 2.1 (4.4), demonstrating PdTe2 as a promising thermoelectric candidate.

FIGURE 8

Figure of merit ZT of the penta-PdSe2 and penta-PdTe2 monolayers under (A)p-type and (B)n-type doping as a function of the carrier concentration at 300 K along the x and y directions.

4 Conclusion

In this study, we systematically investigated the electronic structures, electronic transport, and thermal transport properties of pentagonal PdX2 (X = Se, Te) monolayers using first-principles calculations and with Boltzmann transport theory. The PdSe2 and PdTe2 monolayer semiconductors had bandgaps of 1.31 and 1.26 eV, respectively. The anisotropic crystal structure of penta-PdX2 (X = Se, Te) achieved anisotropic transport properties. At the optimized doping concentration, the PdSe2 and PdTe2 monolayers with p-type and n-type doping along the x- (y-) directions obtained PF of up to 30 (120) and 70 (300) mW m−1 K−2, and 1 (7) and 9 (88) mW m−1 K−2, respectively. The shorter phonon lifetime of penta- PdX2 decreased κl. In particular, the κl values were 3.99 (10.58) and 0.41 (0.83) Wm−1K−1 for PdSe2 and PdTe2 along the x- (y-) direction at 300 K, respectively. Owing to its smaller phonon group velocity and larger scattering space, PdTe2 exhibited lower thermal conductivity. The reasonable PF and low κl imply that the optimal ZT values of p-type and n-type-doped PdTe2 along the y-direction at the optimal doping concentrations of 6.6 and 4.4, respectively, indicating that the PdTe2 monolayer is a thermoelectric material with excellent properties.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

LL and HH: Conceptualization, methodology, software; LL and HH: Writing—original draft preparation. LL, ZH, JX, and HH: Investigation; HH: Supervision; LL: Writing—review and editing.

Funding

Financial support was received from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11904033 and 12204215), the Advanced Research Projects of Chongqing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (cstc2019jcyj-msxmX0674), and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province of China (ZR2021QA026).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2022.1061703/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Bardeen J. Shockley W. (1950). Deformation potentials and mobilities in non-polar crystals. Phys. Rev.80, 72–80. 10.1103/physrev.80.72

2

Bilc D. I. Benea D. Pop V. Ghosez P. Verstraete M. J. (2021). Electronic and thermoelectric properties of transition-metal dichalcogenides. J. Phys. Chem. C125, 27084–27097. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c07088

3

Blöchl P. E. (1994). Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B50, 17953–17979. 10.1103/physrevb.50.17953

4

Buscema M. Barkelid M. Zwiller V. van der Zant H. S. Steele G. A. Castellanos-Gomez A. (2013). Large and tunable photothermoelectric effect in single-layer MoS2. Nano Lett.13, 358–363. 10.1021/nl303321g

5

Ding W. Li X. Jiang F. Liu P. Liu P. Zhu S. et al (2020). Defect modification engineering on a laminar MoS2 film for optimizing thermoelectric properties. J. Mat. Chem. C8, 1909–1914. 10.1039/c9tc06012j

6

Dresselhaus M. S. Chen G. Tang M. Y. Yang R. Lee H. Wang D. et al (2007). New directions for low‐dimensional thermoelectric materials. Adv. Mat.19, 1043–1053. 10.1002/adma.200600527

7

Gao Z. Wang J.-S. (2020). Thermoelectric penta-silicene with a high room-temperature figure of merit. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces12, 14298–14307. 10.1021/acsami.9b21076

8

Gao Z. Zhang Z. Liu G. Wang J.-S. (2019). Ultra-low lattice thermal conductivity of monolayer penta-silicene and penta-germanene. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.21, 26033–26040. 10.1039/c9cp05246a

9

Gu X. Li B. Yang R. (2016). Layer thickness-dependent phonon properties and thermal conductivity of MoS2. J. Appl. Phys.119, 085106. 10.1063/1.4942827

10

He J. Tritt T. M. (2017). Advances in thermoelectric materials research: Looking back and moving forward. Science357, eaak9997. 10.1126/science.aak9997

11

Hippalgaonkar K. Wang Y. Ye Y. Qiu D. Y. Zhu H. Wang Y. et al (2017). High thermoelectric power factor in two-dimensional crystals of MoS2. Phys. Rev. B95, 115407. 10.1103/physrevb.95.115407

12

Hong J. Lee C. Park J.-S. Shim J. H. (2016). Control of valley degeneracy in MoS2 by layer thickness and electric field and its effect on thermoelectric properties. Phys. Rev. B93, 035445. 10.1103/physrevb.93.035445

13

Hong Y. Zhang J. Zeng X. C. (2016). Thermal conductivity of monolayer MoSe2 and MoS2. J. Phys. Chem. C120, 26067–26075. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b07262

14

Hu Z.-Y. Li K.-Y. Lu Y. Huang Y. Shao X.-H. (2017). High thermoelectric performances of monolayer SnSe allotropes. Nanoscale9, 16093–16100. 10.1039/c7nr04766e

15

Huang H. Fan X. Zheng W. Singh D. J. (2021). Improved thermoelectric transport properties of Ge4Se3 Te through dimensionality reduction. J. Mat. Chem. C9, 1804–1813. 10.1039/d0tc04537c

16

Huang S. Wang Z. Xiong R. Yu H. Shi J. (2019). Significant enhancement in thermoelectric performance of Mg3Sb2 from bulk to two-dimensional mono layer. Nano Energy62, 212–219. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.05.028

17

Jonson M. Mahan G. (1980). Mott's formula for the thermopower and the Wiedemann-Franz law. Phys. Rev. B21, 4223–4229. 10.1103/physrevb.21.4223

18

Kresse G. Furthmüller J. (1996). Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mat. Sci.6, 15–50. 10.1016/0927-0256(96)00008-0

19

Kumar S. Schwingenschlogl U. (2015). Thermoelectric response of bulk and monolayer MoSe2 and WSe2. Chem. Mat.27, 1278–1284. 10.1021/cm504244b

20

Lan Y.-S. Chen X.-R. Hu C.-E. Cheng Y. Chen Q.-F. (2019). Penta-PdX2 (X= S, Se, Te) monolayers: Promising anisotropic thermoelectric materials. J. Mat. Chem. A7, 11134–11142. 10.1039/c9ta02138h

21

Li W. Carrete J. Katcho N. A. Mingo N. (2014). ShengBTE: A solver of the Boltzmann transport equation for phonons. Comput. Phys. Commun.185, 1747–1758. 10.1016/j.cpc.2014.02.015

22

Liu P.-F. Bo T. Xu J. Yin W. Zhang J. Wang F. et al (2018). First-principles calculations of the ultralow thermal conductivity in two-dimensional group-IV selenides. Phys. Rev. B98, 235426. 10.1103/physrevb.98.235426

23

Liu X. Ouyang T. Zhang D. Huang H. Wang H. Wang H. et al (2020). First-principles calculations of phonon transport in two-dimensional penta-X2C family. J. Appl. Phys.127, 205106. 10.1063/5.0004904

24

Liu X. Zhang D. Wang H. Chen Y. Wang H. Ni Y. (2021). Ultralow lattice thermal conductivity and high thermoelectric performance of penta-Sb2C monolayer: A first principles study. J. Appl. Phys.130, 185104. 10.1063/5.0065330

25

Liu Z. Wang H. Sun J. Sun R. Wang Z. Yang J. (2018). Penta-Pt2N4: An ideal two-dimensional material for nanoelectronics. Nanoscale10, 16169–16177. 10.1039/c8nr05561k

26

Ma J. Chen Y. Han Z. Li W. (2016). Strong anisotropic thermal conductivity of monolayer WTe2. 2D Mat.3, 045010. 10.1088/2053-1583/3/4/045010

27

Madsen G. K. Singh D. J. (2006). BoltzTraP. A code for calculating band-structure dependent quantities. Comput. Phys. Commun.175, 67–71. 10.1016/j.cpc.2006.03.007

28

Marfoua B. Hong J. (2019). High thermoelectric performance in hexagonal 2D PdTe2 monolayer at room temperature. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces11, 38819–38827. 10.1021/acsami.9b14277

29

Monkhorst H. J. Pack J. D. (1976). Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B13, 5188–5192. 10.1103/physrevb.13.5188

30

Naseri M. Lin S. Jalilian J. Gu J. Chen Z. (2018). Penta-P2X (X= C, Si) monolayers as wide-bandgap semiconductors: A first principles prediction. Front. Phys.13, 138102–138109. 10.1007/s11467-018-0758-2

31

Oyedele A. D. Yang S. Liang L. Puretzky A. A. Wang K. Zhang J. et al (2017). PdSe2: Pentagonal two-dimensional layers with high air stability for electronics. J. Am. Chem. Soc.139, 14090–14097. 10.1021/jacs.7b04865

32

Patel A. Singh D. Sonvane Y. Thakor P. Ahuja R. (2020). High thermoelectric performance in two-dimensional Janus monolayer material WS-X (X= Se and Te). ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces12, 46212–46219. 10.1021/acsami.0c13960

33

Peng B. Zhang D. Zhang H. Shao H. Ni G. Zhu Y. et al (2017). The conflicting role of buckled structure in phonon transport of 2D group-IV and group-V materials. Nanoscale9, 7397–7407. 10.1039/c7nr00838d

34

Peng B. Zhang H. Shao H. Xu Y. Zhang R. Lu H. et al (2016). First-principles prediction of ultralow lattice thermal conductivity of dumbbell silicene: A comparison with low-buckled silicene. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces8, 20977–20985. 10.1021/acsami.6b04211

35

Perdew J. P. Burke K. Ernzerhof M. (1996). Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett.77, 3865–3868. 10.1103/physrevlett.77.3865

36

Raval D. Babariya B. Gupta S. K. Gajjar P. Ahuja R. (2021). Ultrahigh carrier mobility and light-harvesting performance of 2D penta-PdX2 monolayer. J. Mat. Sci.56, 3846–3860. 10.1007/s10853-020-05501-w

37

Snyder G. J. Snyder A. H. (2017). Figure of merit ZT of a thermoelectric device defined from materials properties. Energy Environ. Sci.10, 2280–2283. 10.1039/c7ee02007d

38

Sun M. Chou J.-P. Shi L. Gao J. Hu A. Tang W. et al (2018). Few-layer PdSe2 sheets: Promising thermoelectric materials driven by high valley convergence. ACS omega3, 5971–5979. 10.1021/acsomega.8b00485

39

Tan G. Zhao L.-D. Kanatzidis M. G. (2016). Rationally designing high-performance bulk thermoelectric materials. Chem. Rev.116, 12123–12149. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00255

40

Tao W.-L. Lan J.-Q. Hu C.-E. Cheng Y. Zhu J. Geng H.-Y. (2020). Thermoelectric properties of Janus MXY (M= Pd, Pt; X, Y= S, Se, Te) transition-metal dichalcogenide monolayers from first principles. J. Appl. Phys.127, 035101. 10.1063/1.5130741

41

Tao W.-L. Zhao Y.-Q. Zeng Z.-Y. Chen X.-R. Geng H.-Y. (2021). Anisotropic thermoelectric materials: Pentagonal PtM2 (M = S, Se, Te). ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces13, 8700–8709. 10.1021/acsami.0c19460

42

Tian H. Tice J. Fei R. Tran V. Yan X. Yang L. et al (2016). Low-symmetry two-dimensional materials for electronic and photonic applications. Nano Today11, 763–777. 10.1016/j.nantod.2016.10.003

43

Togo A. Oba F. Tanaka I. (2008). First-principles calculations of the ferroelastic transition between rutile-type and CaCl2-type SiO2 at high pressures. Phys. Rev. B78, 134106. 10.1103/physrevb.78.134106

44

Wang N. Gong H. Sun Z. Shen C. Li B. Xiao H. et al (2021). Boosting thermoelectric performance of 2D transition-metal dichalcogenides by complex cluster substitution: The role of octahedral Au6 clusters. ACS Appl. Energy Mat.4, 12163–12176. 10.1021/acsaem.1c01777

45

Wang Y. Li Y. Chen Z. (2015). Not your familiar two dimensional transition metal disulfide: Structural and electronic properties of the PdS2 monolayer. J. Mat. Chem. C3, 9603–9608. 10.1039/c5tc01345c

46

Xiao Y. Chang C. Pei Y. Wu D. Peng K. Zhou X. et al (2016). Origin of low thermal conductivity in SnSe. Phys. Rev. B94, 125203. 10.1103/physrevb.94.125203

47

Xing G. Sun J. Ong K. P. Fan X. Zheng W. Singh D. J. (2016). Perspective: n-Type oxide thermoelectrics via visual search strategies. Apl. Mat.4, 053201. 10.1063/1.4941711

48

Yan R. Simpson J. R. Bertolazzi S. Brivio J. Watson M. Wu X. et al (2014). Thermal conductivity of monolayer molybdenum disulfide obtained from temperature-dependent Raman spectroscopy. ACS Nano8, 986–993. 10.1021/nn405826k

49

Yang L. Chen Z. G. Dargusch M. S. Zou J. (2018). High performance thermoelectric materials: Progress and their applications. Adv. Energy Mat.8, 1701797. 10.1002/aenm.201701797

50

Yoshida M. Iizuka T. Saito Y. Onga M. Suzuki R. Zhang Y. et al (2016). Gate-optimized thermoelectric power factor in ultrathin WSe2 single crystals. Nano Lett.16, 2061–2065. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b00075

51

Yue T. Sun Y. Zhao Y. Meng S. Dai Z. (2022). Thermoelectric performance in the binary semiconductor compound A2Se2 (A= K, Rb) with host-guest structure. Phys. Rev. B105, 054305. 10.1103/physrevb.105.054305

52

Zhang J. Liu X. Wen Y. Shi L. Chen R. Liu H. et al (2017). Titanium trisulfide monolayer as a potential thermoelectric material: A first-principles-based Boltzmann transport study. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces9, 2509–2515. 10.1021/acsami.6b14134

53

Zhang L.-C. Qin G. Fang W.-Z. Cui H.-J. Zheng Q.-R. Yan Q.-B. et al (2016). Tinselenidene: A two-dimensional auxetic material with ultralow lattice thermal conductivity and ultrahigh hole mobility. Sci. Rep.6, 19830. 10.1038/srep19830

54

Zhang S. Zhou J. Wang Q. Chen X. Kawazoe Y. Jena P. (2015). Penta-graphene: A new carbon allotrope. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.112, 2372–2377. 10.1073/pnas.1416591112

55

Zhao L.-D. Tan G. Hao S. He J. Pei Y. Chi H. et al (2016). Ultrahigh power factor and thermoelectric performance in hole-doped single-crystal SnSe. Science351, 141–144. 10.1126/science.aad3749

56

Zhao Y. Yu P. Zhang G. Sun M. Chi D. Hippalgaonkar K. et al (2020). Low‐symmetry PdSe2 for high performance thermoelectric applications. Adv. Funct. Mat.30, 2004896. 10.1002/adfm.202004896

57

Zhu X.-L. Hou C.-H. Zhang P. Liu P.-F. Xie G. Wang B.-T. (2019). High thermoelectric performance of new two-dimensional IV–VI compounds: A first-principles study. J. Phys. Chem. C124, 1812–1819. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b09787

Summary

Keywords

two-dimensional material, thermoelectric material, transport property, first-principles calculation, electronic structure

Citation

Li L, Huang Z, Xu J and Huang H (2022) Theoretical analysis of the thermoelectric properties of penta-PdX2 (X = Se, Te) monolayer. Front. Chem. 10:1061703. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2022.1061703

Received

04 October 2022

Accepted

28 October 2022

Published

08 November 2022

Volume

10 - 2022

Edited by

San-Dong Guo, Xi’an University of Posts and Telecommunications, China

Reviewed by

Liang Qiao, Changchun University, China

Zhi Wen Chen, University of Toronto, Canada

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Li, Huang, Xu and Huang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haihua Huang, huanghaihua@lcu.edu.cn

This article was submitted to Physical Chemistry and Chemical Physics, a section of the journal Frontiers in Chemistry

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.