Abstract

Mucin 1 (MUC1), a well-known tumor-associated antigen and attractive target for tumor immunotherapy, is overexpressed in most human epithelial adenomas with aberrant glycosylation. However, its low immunogenicity impedes the development of MUC1-targeted antitumor vaccines. In this study, we investigated three liposomal adjuvant systems containing toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) agonist monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA) and auxiliary lipids of different charges: cationic lipid dimethyldioctadecylammonium (DDA), neutral lipid distearoylglycerophosphocholine (DSPC) or anionic lipid dioleoylphosphatidylglycerol (DOPG), respectively. ELISA assay evidenced that the positively charged DDA/MPLA liposomes are potent immune activators, which induced remarkable levels of anti-MUC1 antibodies and exhibited robust Th1-biased immune responses. Importantly, the antibodies induced by DDA/MPLA liposomes efficiently recognized and killed MUC1-positive tumor cells through complement-mediated cytotoxicity. In addition, antibody titers in mice immunized with P2-MUC1 vaccine were significantly higher than those from mice immunized with P1-MUC1 or MUC1 vaccine, which indicated that the lipid conjugated on MUC1 antigen also played important role for immunomodulation. This study suggested that the liposomal DDA/MPLA with lipid-MUC1 is a promising antitumor vaccine, which can be used for the immunotherapy of various epithelial carcinomas represented by breast cancer.

Introduction

Mucin1 (MUC1), a transmembrane glycoprotein highly overexpressed and aberrantly glycosylated on many tumor tissues including ovarian, breast, pancreatic, prostate and ovarian carcinomas (Hollingsworth and Swanson, 2004; Kufe, 2009; Nath and Mukherjee, 2014; Chen et al., 2021). MUC1 glycoprotein contains a variable number of tandem repeats (VNTRs) region (HGVTSAPDTRPAPGSTAPPA) in its extracellular domain (Gaidzik et al., 2013; Pillai et al., 2015; Li and Li, 2020). With its unique biological features, tumor-associated antigen MUC1 glycoprotein has been considered as one of the favorable targets for the development of cancer immunotherapy (Barratt-Boyes, 1996; Singh and Bandyopadhyay, 2007; Pillai et al., 2015; Dhanisha et al., 2018; Brockhausen and Melamed, 2021). However, the weak immunogenicity of MUC1 limits its development and clinical application (Tang et al., 2008; Tang et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2021). To increase its immunogenicity, co-delivery of immunostimulating components and antigens establish an effective strategy for cancer vaccine (Ingale et al., 2007; Cai et al., 2014; Yin et al., 2017; Wu X. et al., 2018; Wu J.-J. et al., 2018; Supekar et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2021).

TLRs present on diverse cells like macrophages, Dendritic cells (DCs), B cells and natural killer (NK) cells (Adams, 2009; Baxevanis et al., 2013; Li et al., 2017; Gao and Guo, 2018; Owen et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2022). Monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA), a TLR4 agonist optimized from Salmonella minnesota lipopolysaccharide (LPS), is a promising immunostimulant licensed for use in human vaccines preventing viral infections (Alderson et al., 2006; Vacchelli et al., 2012; Gao and Guo, 2018; Shetab Boushehri and Lamprecht, 2018; Romerio and Peri, 2020). MPLA plays an important role in stimulating the maturation of DCs, inducing the upregulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II molecules, and promoting the migration of DCs to CD4 T cells (Akira and Takeda, 2004). In addition, MPLA is being actively investigated as a potent immunostimulatory adjuvant to cancer vaccines (Cluff et al., 2005; Didierlaurent et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017; Facchini et al., 2021).

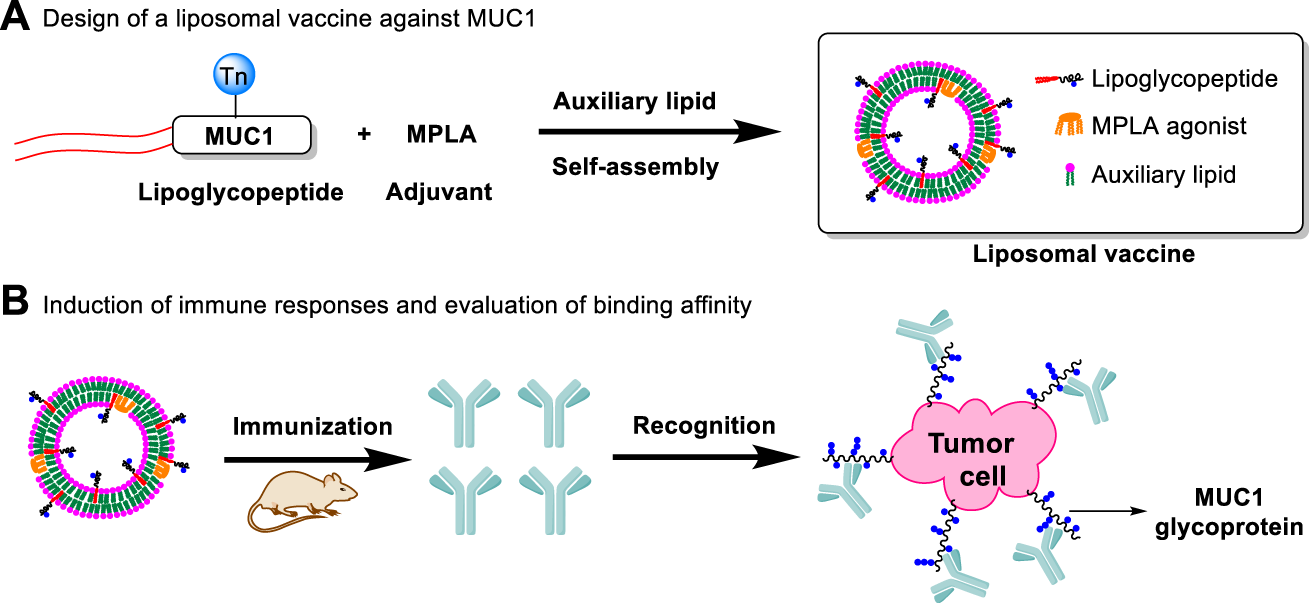

Lipid modification of peptides can promote self-assembly and formation of liposomes, which can enhance their immunogenicity by presenting the multivalent antigens and increasing uptake by antigen presenting cells (APCs) (Eskandari et al., 2017; Aiga et al., 2020). In addition, our previous studies showed that co-delivery of adjuvants and antigens via liposomes significantly increased the immunogenicity of antigen (Du et al., 2019). As liposomal adjuvant, MPLA can also effectively participate in the formation of liposomes and enhance immune responses (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Design of a liposomal vaccine consisting of auxiliary lipids, MUC1 lipoglycopeptides and MPLA adjuvant. (A) Design of a liposomal vaccine against MUC1; (B) Induction of immune responses and evaluation of binding affinity.

Based on the above considerations, we developed liposomal vaccines using the amphiphilic lipidated MUC1 glycopeptides as target antigens and TLR4 agonist MPLA as immunoadjuvant. Considering that the negative charge of the MPLA adjuvant may affect the assembly of liposomes (Brandt et al., 2000; Korsholm et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013), we designed three commonly applied auxiliary lipids of different charges including cationic lipid dimethyldioctadecylammonium (DDA) (Hilgers and Snippe, 1992; Korsholm et al., 2007), neutral lipid distearoylglycerophosphocholine (DSPC) and anionic lipid dioleoylphosphatidylglycerol (DOPG), respectively. DDA could efficiently form a kind of cationic liposome, which facilitated the antigen presentation and further induced Th1-biased immune responses (Qu et al., 2018). Phospholipid DSPC (Nakamura et al., 2015) or DOPG (Yanasarn et al., 2011) is used as the key component in the formation of liposomes. Its stability is affected by phospholipid charge, which can influence drug delivery efficiency. The DDA cationic liposome-forming lipid has been reported to enhance the antigen uptake and presentation to T cells as a potent adjuvant (Yu et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013). In addition, in order to determine the best lipid anchor, four MUC1 glycopeptides were constructed: MUC1, P1-MUC1, P2-MUC1 and P3-MUC1, then the structure-activity relationship between the lipid-tailed MUC1 and the liposomal adjuvant system was studied.

Results and Discussion

Chemical Synthesis of MUC1 Glycopeptide and Lipoglycopeptides

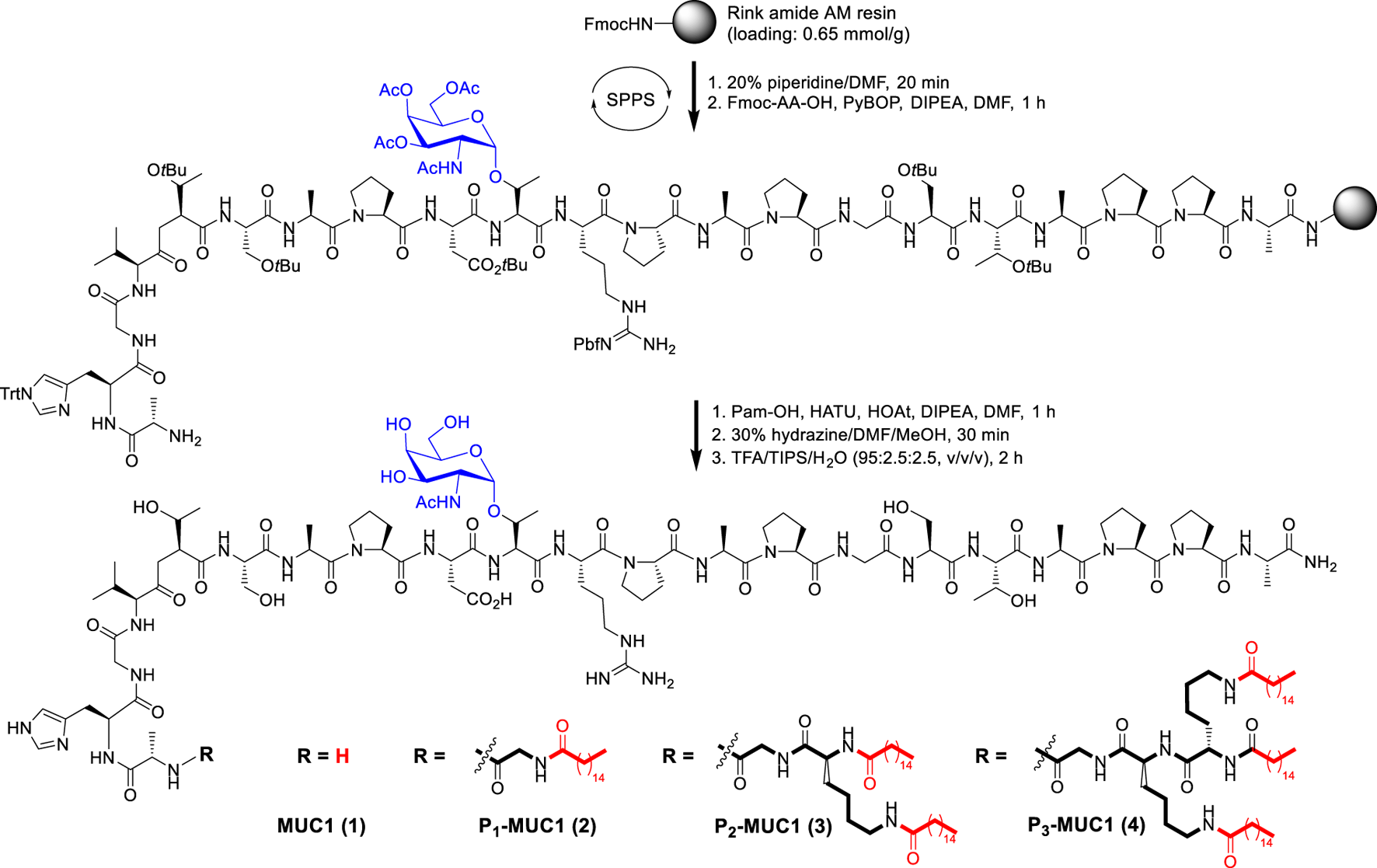

The resin-bound peptide MUC1 with Tn glycosylation on the PDTRP motif was synthesized via the solid phase methodology using Fmoc strategy (Scheme 1 and Supplementary Schemes S1–S4). Then the palmitic acid was directly conjugated to the resin-bound peptide as described previously (Du et al., 2019). After deprotection and work up, the MUC1 glycopeptide and lipoglycopeptides were isolated in yields of 10–35% and characterized by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and ESI mass spectrometry (Supplementary Figures S6–S13).

SCHEME 1

Synthesis of MUC1 glycopeptide and lipoglycopeptides by solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS).

Design and Preparation of Vaccine Candidates

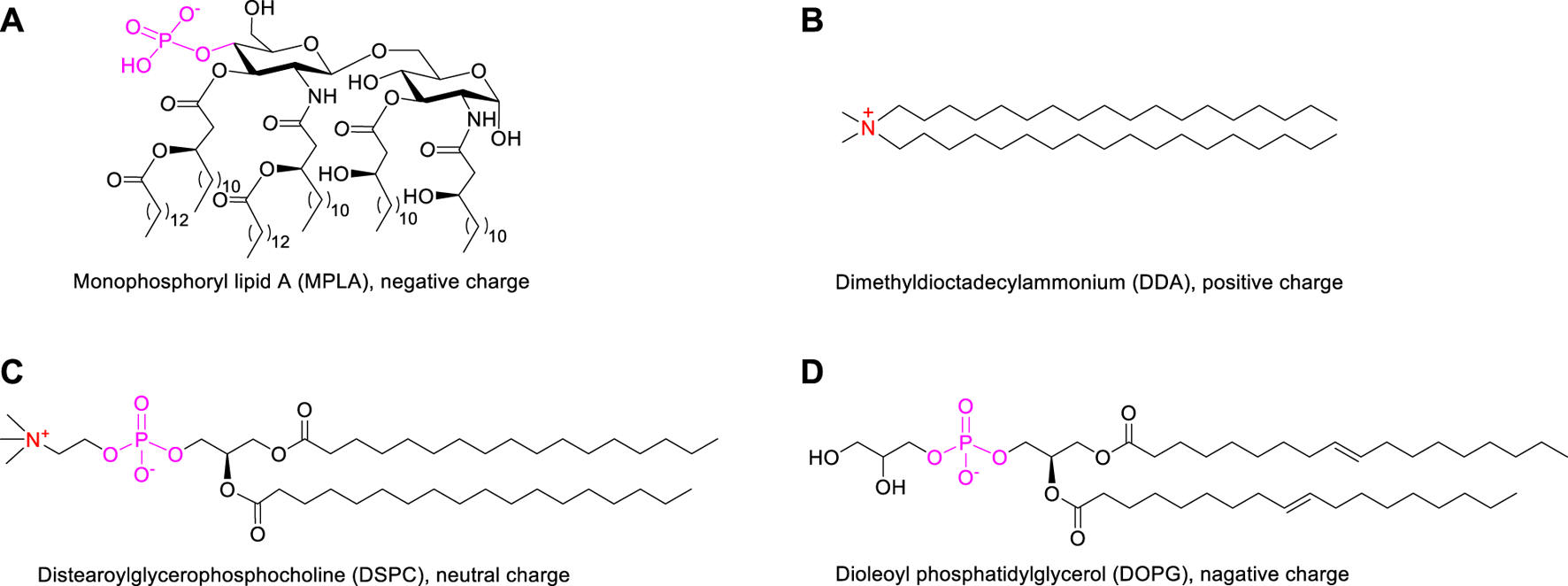

The design of a liposomal adjuvant based on MPLA and auxiliary lipids of different charges was described in Supplementary Table S1. In this strategy, two issues are mainly discussed: 1) the interaction between auxiliary lipids of different charges and the adjuvant MPLA (Figure 2); 2) the influence of different numbers of lipid chain on the immune activity of vaccines. Liposomes composed of antigens, adjuvant and auxiliary lipids were produced using the lipid-film hydration method (Du et al., 2019). The mole ratio of MUC1 antigen, agonist (MPLA), auxiliary lipid was maintained at 1:1:8 (Karlsen et al., 2014). Subsequently, in order to compare the effect of different auxiliary lipids on vaccine efficacy, positive charged DDA, neutral DSPC and negatively charged DOPG were introduced. Finally, to explore the influence of lipid modification, equimolar amounts of MUC1 glycopeptide (10 nmol, 22 μg), Pam(P1)-MUC1 (10 nmol, 25 μg), Pam2(P2)-MUC1 (10 nmol, 28 μg) and Pam3(P3)-MUC1 (10 nmol, 32 μg) were employed in the vaccine design. After hydration of a lipid film that contained all components in a 10 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4), the liposomes were prepared by ultrasound for 20 min.

FIGURE 2

The structures of MPLA adjuvant (A) and auxiliary lipids including cationic DDA (B), neutral DSPC (C) and anionic DOPG (D).

Immunization of Mice

Female BALB/c mice (aged 6–8 weeks) were inoculated on day 0, and again on days 14 and 28. Two weeks after each immunization, sera were collected for immune activity assessment (Supplementary Scheme S6). All animal studies were carried out according to National Institute of Health and institutional guidelines. During the immunization period, no weight loss and other abnormal physiological phenomena (such as changes in hair, behavior and appetite) (Supplementary Figure S5) were observed in mice.

Characterization of Vaccines

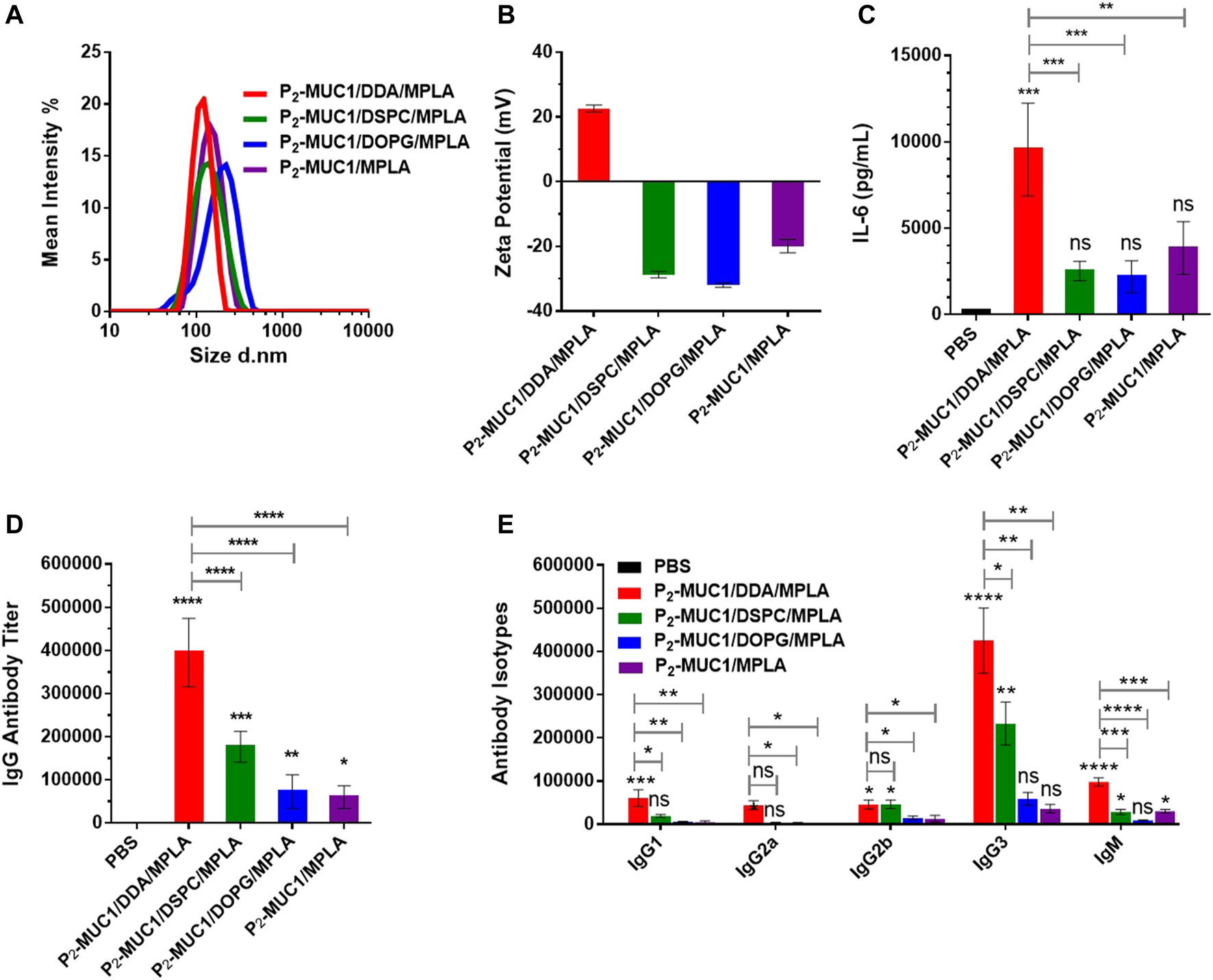

As shown in Figure 3A, the dynamic light scattering (DLS) showed that these liposomes have homogeneous particle sizes with diameters of approximately 100 nm, which may facilitate transport to the lymph nodes (Jiang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018). In addition, zeta potential showed that liposomal DDA/MPLA along with P2-MUC1 antigen had a higher value of positive zeta potential than other liposomes (DSPC/MPLA or DOPG/MPLA) (Figure 3B). The charge of liposomes is mainly caused by a combination of auxiliary lipids and MPLA. Due to the mole ratio of DDA and MPLA at 8:1, the cationic DDA makes its corresponding liposome positively charged.

FIGURE 3

DLS (A) and zeta potential (B) results for vaccines. Values are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). The secretions of cytokines (C), MUC1-specific IgG antibody (D) and antibody isotypes (E) were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (n = 5). Control: phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). ****, p < .0001, ***, p < .001, **, p < .01, and *, p < .05 compared with the control group by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey’s HSD test. Comparisons between different groups were also conducted by ANOVA using Tukey’s HSD test. Data represent the mean ± SD of five mice from three separate experiments.

Liposomal DDA/MPLA Induced a Stronger Immune Response

To assess the interaction between MPLA agonist and auxiliary lipids of different charges, the secretion level of IL-6 after the first immunization was evaluated (Figure 3C). The results showed that all groups containing MPLA agonist produced high levels of IL-6 compared to the control group. This rapid production of cytokines indicated that the TLR signaling pathways were activated in mice immunized with these vaccines. Interestingly, IL-6 cytokines induced by the co-administration of cationic DDA and MPLA was higher than those induced by DSPC/MPLA and DOPG/MPLA. This may be attributed to the better electrostatic attraction between the positively charged DDA and the negatively charged MPLA agonist (Hilgers and Snippe, 1992; Korsholm et al., 2007), which increased uptake of liposomes by APCs.

As DDA/MPLA showed a great ability to induce cytokine secretion, we next explored its potential in stimulating antibody responses in vivo. The MUC1-specific IgG antibody titers in sera were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Compared with P2-MUC1/DSPC/MPLA and P2-MUC1/DOPG/MPLA liposomal vaccines, the P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA liposomal vaccine induced higher anti-MUC1 IgG antibody titers (Figure 3D, 2-fold higher than P2-MUC1/DSPC/MPLA, 5-fold higher than P2-MUC1/DOPG/MPLA). In terms of antibody isotypes, IgG3 titers were greatly increased in mice immunized with DDA/MPLA/P2-MUC1 (Figure 3E), which suggested that DDA/MPLA liposome could promote antigen deposition at the injection site and induce prominent Th1-biased response (Henriksen-Lacey et al., 2011). In addition, P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA liposomal vaccine induced higher levels of IgG antibody titers than P2-MUC1/MPLA without any auxiliary lipids (6-fold).

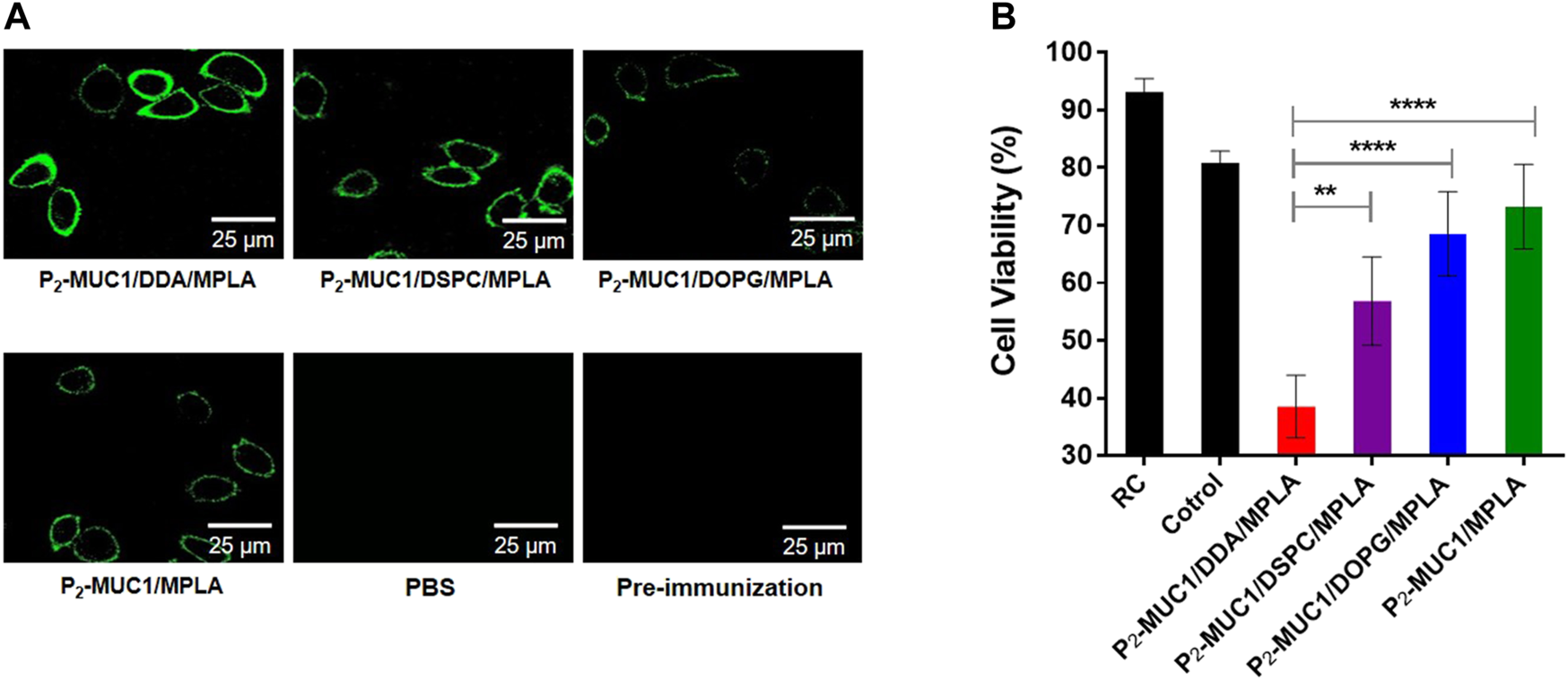

Meanwhile, the ability of antisera to recognize human MCF-7 breast cancer cell line was detected by confocal fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry techniques. As shown in Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure S2, on one hand, P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA vaccine induced higher levels of antibodies that recognized MUC1 positive MCF-7 cancer cells relative to P2-MUC1/DSPC/MPLA and P2-MUC1/DOPG/MPLA vaccine. On the other hand, P2-MUC1/MPLA vaccine without any auxiliary lipids not only generated lower levels of IL-6 cytokines and antibodies, but also showed low binding affinity. This result indicated that the positively charged liposomes with DDA and MPLA were important to enhance the recognition ability of antibodies to cancer cells.

FIGURE 4

MUC1-specific antibodies recognize MUC1-positive breast cancer cell line (MCF-7). (A) Confocal fluorescence microscopy images of the cells stained with pre-immunization sera, sera from PBS and the third immunization antisera collected from P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA, P2-MUC1/DSPC/MPLA, P2-MUC1/DOPG/MPLA and P2-MUC1/MPLA group. (Scale bar = 25 μm). (B) MTT test for complement-dependent cytotoxicity. Differences were determined by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD test (PBS was used as control). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (****p < .0001, **p < .01). Data are the mean SD of five mice and are representative of five independent experiments.

In addition, to evaluate the potential of antisera to activate the complement system, the complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) assay was performed and the percentage of lysed cells was determined by applying a tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. As shown in Figure 4B, when P2-MUC1 was used as an antigen, the antisera from DDA/MPLA gourp could more effectively activate the complement system and kill MCF-7 cells than DSPC/MPLA and DOPG/MPLA group. These result reflected that the antigen-specific antibodies induced by cationic DDA/MPLA liposomes can effectively activate the complement system. The co-delivery of adjuvant and antigen was guaranteed by stable liposomes. There is a better electrostatic attraction between the positively charged DDA and the negatively charged MPLA agonist, which enhances the stability of the liposomes (Brandt et al., 2000; Korsholm et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013) and facilitated the uptake of antigen by antigen presenting cells (APCs). On the other hand, positively charged liposomes may be more easily absorbed and swallowed by negatively charged cell membranes. Therefore, the immune responses were enhanced by P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA liposomal vaccine.

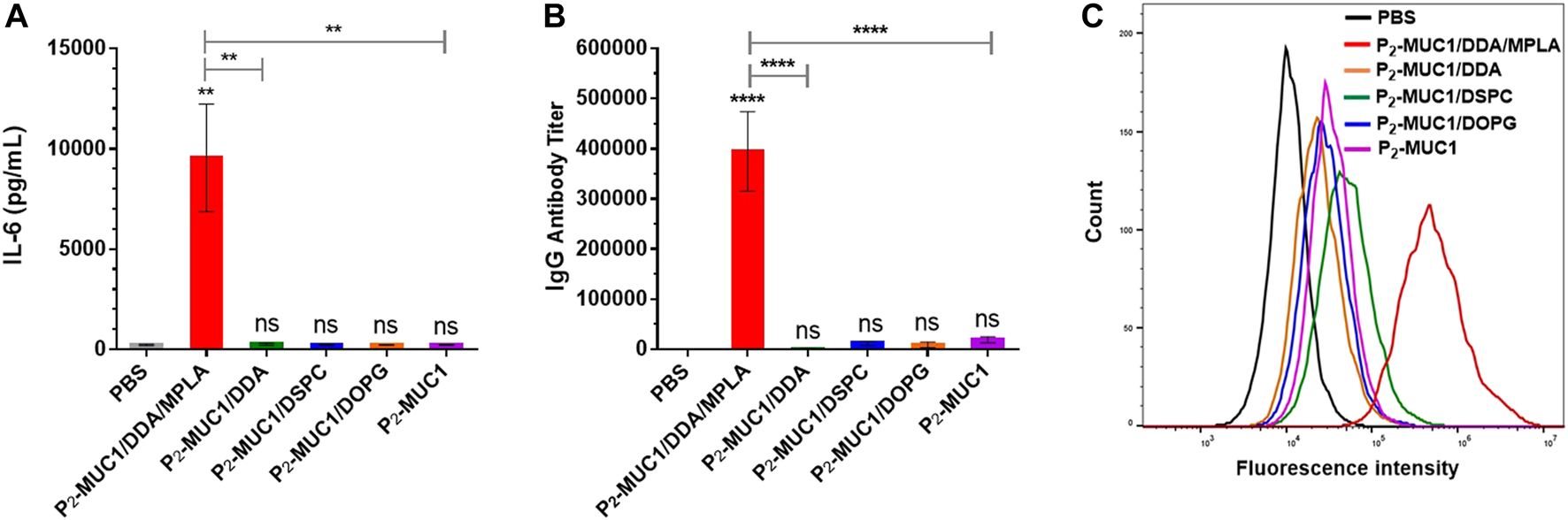

To determine the role of MPLA adjuvant in vaccines, mice were immunized with P2-MUC1/DDA, P2-MUC1/DSPC, P2-MUC1/DOPG and P2-MUC1. As shown in Figure 5, the results showed that only administration with MPLA increased the secretion levels of IL-6 cytokines (Figure 5A) and IgG antibody titers (Figure 5B) in mice. Moreover, the recognition potential of different groups was also assessed (Figure 5C). Only the antisera of mice vaccinated with MPLA showed a strong binding ability to the target cells MCF-7, which indicated that MPLA played an important role to enhance the anti-MUC1 immune responses and improve the recognization ability of antibodies to MCF-7 cells.

FIGURE 5

The secretions of cytokines (A) and MUC1-specific IgG antibody (B) were detected by ELISA (n = 5). (C) Flow cytometry histograms of the cells stained with sera from PBS and the third immunization antisera collected from P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA, P2-MUC1/DDA, P2-MUC1/DSPC, P2-MUC1/DOPG and P2-MUC1 group. Control: phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). ****, p < .0001 and **, p < .01 compared with the control group by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey’s HSD test. Comparisons between different groups were also conducted by ANOVA using Tukey’s HSD test. Data represent the mean ± SD of five mice from three separate experiments.

Lipid Modification of MUC1 Glycopeptide Improved Immune Responses

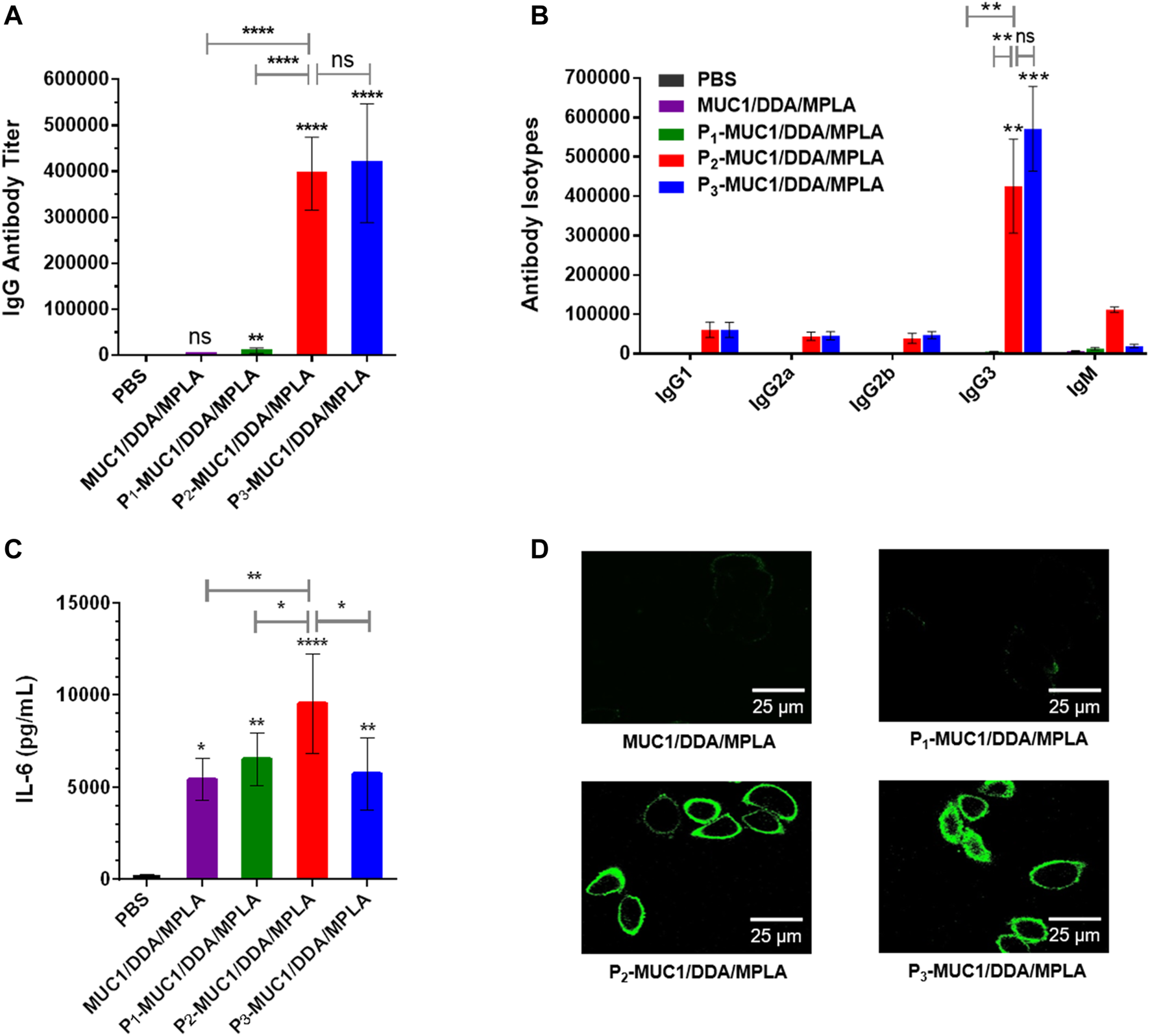

To explore the influence of lipid modification, equimolar amounts of MUC1 glycopeptide, P1-MUC1, P2-MUC1 and P3-MUC1 were employed in the DDA/MPLA vaccines design. The results indicated that P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA induced stronger anti-MUC1 specific IgG antibody responses in mice (110 and 38-fold higher IgG titers than MUC1/DDA/MPLA and P1-MUC1/DDA/MPLA at day 42, respectively). The IgG antibodies elicited by P3-MUC1/DDA/MPLA was comparable to P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA (Figure 6A).

FIGURE 6

The secretions of MUC1-specific IgG antibody (A), antibody isotypes (B) and cytokines (C) were detected by ELISA (n = 5). (D) Confocal fluorescence microscopy images of the cells stained with sera from PBS and the third immunization antisera collected from MUC1/DDA/MPLA, P1-MUC1/DDA/MPLA, P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA, P3-MUC1/DDA/MPLA. The images are representative of five independent experiments (Scale bar = 25 μm).

Meanwhile, the sera on day 14 of P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA group also showed high IgG antibody titers, indicating that P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA could rapidly elicit robust immune responses (Supplementary Figure S4). Next, the anti-MUC1 IgG antibody subclasses (IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3) titers on day 42 were also analyzed (Figure 6B). Except for groups immunized with P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA and P3-MUC1/DDA/MPLA, other groups were unable to induce an effective antibody immune response. No significant difference was observed between P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA and P3-MUC1/DDA/MPLA in IgG subtypes titers. Interestingly, the level of IgG3 was remarkably higher than that of IgG1, which may be partly attributed to the fact that MPLA is a T helper type 1-like (Th1) adjuvant (Korsholm et al., 2010; Gao and Guo, 2018).

In addition, P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA produced higher levels of IL-6 cytokines compared to MUC1, lipidated P1-MUC1 or P3-MUC1 with positively charged DDA and MPLA adjuvant (Figure 6C). As shown in Figure 6D, compared with P3-MUC1/DDA/MPLA group, P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA group showed a similar fluorescence intensity, which was significantly stronger than other vaccine candidates (MUC1/DDA/MPLA and P1-MUC1/DDA/MPLA). This may be due to the fact that lipid modification of MUC1 glycopeptides promoted self-assembly and formation of liposomes, which enhanced immune responses by presenting the multivalent antigens and increasing uptake by APCs. Given that P2-MUC1 is easier to synthesize and prepare than P3-MUC1 and can be assembled into liposomes with smaller particle sizes (Supplementary Figure S1), dipalmitoyl lipid anchors are the best lipid anchors.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we developed liposomal vaccines containing auxiliary lipids of different charges, MUC1 lipoglycopeptides and MPLA adjuvant. Compared with the negatively charged DOPG and the neutral DSPC, the positively charged DDA induced stronger antigen-specific immune responses. In addition, we confirmed that the amphiphilic P2-MUC1 glycopeptide promoted the assembly of liposomal vaccines and significantly enhanced the recognition ability of antibodies to MCF-7 cells. More importantly, the sera from P2-MUC1/DDA/MPLA gourp could effectively activate the complement system and kill MCF-7 cells. The results showed that the strategy of coadministration of lipoglycopeptide and liposomal DDA/MPLA is a convenient platform for building antitumor vaccines.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Laboratory Animal Center, Huazhong Agricultural University.

Author contributions

JG, L-SW and J-JD conceived the research ideas, supervised the project and wrote the manuscript. S-HZ and W-BX performed the animal experiments. R-YZ and Z-RC performed the immunological experiments. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Funding

The project was funded by the Talent Introduction Project of Hubei Polytechnic University (21xjz32R), National Natural Science Foundation of China (21772056, 22177035), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFA0505200), Wuhan Bureau of Science and Technology (2020020601012217), Youth Chutian Scholar Fund of Hubei Province (4032401), and State Key Laboratory of Structural Chemistry (20180023).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2022.814880/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Adams S. (2009). Toll-like Receptor Agonists in Cancer Therapy. Immunotherapy1, 949–964. 10.2217/imt.09.70

2

Aiga T. Manabe Y. Ito K. Chang T. C. Kabayama K. Ohshima S. et al (2020). Immunological Evaluation of Co‐Assembling a Lipidated Peptide Antigen and Lipophilic Adjuvants: Self‐Adjuvanting Anti‐Breast‐Cancer Vaccine Candidates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.59, 17705–17711. 10.1002/anie.202007999

3

Akira S. Takeda K. (2004). Toll-like Receptor Signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol.4, 499–511. 10.1038/nri1391

4

Alderson M. R. McGowan P. Baldridge J. R. Probst P. (2006). TLR4 Agonists as Immunomodulatory Agents. J. Endotoxin Res.12, 313–319. 10.1179/096805106X118753

5

Barratt-Boyes S. M. (1996). Making the Most of Mucin: a Novel Target for Tumor Immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother.43, 142–151. 10.1007/s002620050315

6

Baxevanis C. N. Voutsas I. F. Tsitsilonis O. E. (2013). Toll-like Receptor Agonists: Current Status and Future Perspective on Their Utility as Adjuvants in Improving Antic Ancer Vaccination Strategies. Immunotherapy5, 497–511. 10.2217/imt.13.24

7

Brandt L. Elhay M. Rosenkrands I. Lindblad E. B. Andersen P. (2000). ESAT-6 Subunit Vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun.68, 791–795. 10.1128/IAI.68.2.791-795.2000

8

Brockhausen I. Melamed J. (2021). Mucins as Anti-cancer Targets: Perspectives of the Glycobiologist. Glycoconj. J.38, 459–474. 10.1007/s10719-021-09986-8

9

Cai H. Sun Z.-Y. Chen M.-S. Zhao Y.-F. Kunz H. Li Y.-M. (2014). Synthetic Multivalent Glycopeptide-Lipopeptide Antitumor Vaccines: Impact of the Cluster Effect on the Killing of Tumor Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.53, 1699–1703. 10.1002/anie.201308875

10

Chen W. Zhang Z. Zhang S. Zhu P. Ko J. K.-S. Yung K. K.-L. (2021). MUC1: Structure, Function, and Clinic Application in Epithelial Cancers. Ijms22, 6567. 10.3390/ijms22126567

11

Cluff C. W. Baldridge J. R. Stöver A. G. Evans J. T. Johnson D. A. Lacy M. J. et al (2005). Synthetic Toll-like Receptor 4 Agonists Stimulate Innate Resistance to Infectious challenge. Infect. Immun.73, 3044–3052. 10.1128/IAI.73.5.3044-3052.2005

12

Didierlaurent A. M. Morel S. Lockman L. Giannini S. L. Bisteau M. Carlsen H. et al (2009). AS04, an Aluminum Salt- and TLR4 Agonist-Based Adjuvant System, Induces a Transient Localized Innate Immune Response Leading to Enhanced Adaptive Immunity. J. Immunol.183, 6186–6197. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901474

13

Dhanisha S. S. Guruvayoorappan C. Drishya S. Abeesh P. (2018). Mucins: Structural Diversity, Biosynthesis, its Role in Pathogenesis and as Possible Therapeutic Targets. Crit. Rev. Oncology/Hematology122, 98–122. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.12.006

14

Du J. J. Zou S. Y. Chen X. Z. Xu W. B. Wang C. W. Zhang L. et al (2019). Liposomal Antitumor Vaccines Targeting Mucin 1 Elicit a Lipid‐Dependent Immunodominant Response. Chem. Asian J.14, 2116–2121. 10.1002/asia.201900448

15

Eskandari S. Guerin T. Toth I. Stephenson R. J. (2017). Recent Advances in Self-Assembled Peptides: Implications for Targeted Drug Delivery and Vaccine Engineering. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.110-111, 169–187. 10.1016/j.addr.2016.06.013

16

Facchini F. A. Minotti A. Luraghi A. Romerio A. Gotri N. Matamoros-Recio A. et al (2021). Synthetic Glycolipids as Molecular Vaccine Adjuvants: Mechanism of Action in Human Cells and In Vivo Activity. J. Med. Chem.64, 12261–12272. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00896

17

Gaidzik N. Westerlind U. Kunz H. (2013). The Development of Synthetic Antitumour Vaccines from Mucin Glycopeptide Antigens. Chem. Soc. Rev.42, 4421–4442. 10.1039/c3cs35470a

18

Gao J. Guo Z. (2018). Progress in the Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Lipid A and its Derivatives. Med. Res. Rev.38, 556–601. 10.1002/med.21447

19

Henriksen-Lacey M. Christensen D. Bramwell V. W. Lindenstrøm T. Agger E. M. Andersen P. et al (2011). Comparison of the Depot Effect and Immunogenicity of Liposomes Based on Dimethyldioctadecylammonium (DDA), 3β-[N-(N′,N′-Dimethylaminoethane)carbomyl] Cholesterol (DC-Chol), and 1,2-Dioleoyl-3-Trimethylammonium Propane (DOTAP): Prolonged Liposome Retention Mediates Stronger Th1 Responses. Mol. Pharmaceutics8, 153–161. 10.1021/mp100208f

20

Hilgers L. A. T. Snippe H. (1992). DDA as an Immunological Adjuvant. Res. Immunol.143, 494–503. 10.1016/0923-2494(92)80060-x

21

Hollingsworth M. A. Swanson B. J. (2004). Mucins in Cancer: protection and Control of the Cell Surface. Nat. Rev. Cancer4, 45–60. 10.1038/nrc1251

22

Ingale S. Wolfert M. A. Gaekwad J. Buskas T. Boons G.-J. (2007). Robust Immune Responses Elicited by a Fully Synthetic Three-Component Vaccine. Nat. Chem. Biol.3, 663–667. 10.1038/nchembio.2007.25

23

Jiang H. Wang Q. Sun X. (2017). Lymph Node Targeting Strategies to Improve Vaccination Efficacy. J. Controlled Release267, 47–56. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.08.009

24

Karlsen K. Korsholm K. S. Mortensen R. Ghiasi S. M. Andersen P. Foged C. et al (2014). A Stable Nanoparticulate DDA/MMG Formulation Acts Synergistically with CpG ODN 1826 to Enhance the CD4+ T-Cell Response. Nanomedicine9, 2625–2638. 10.2217/nnm.14.197

25

Korsholm K. S. Petersen R. V. Agger E. M. Andersen P. (2010). T‐helper 1 and T‐helper 2 Adjuvants Induce Distinct Differences in the Magnitude, Quality and Kinetics of the Early Inflammatory Response at the Site of Injection. Immunology129, 75–86. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03164.x

26

Kufe D. W. (2009). Mucins in Cancer: Function, Prognosis and Therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer9, 874–885. 10.1038/nrc2761

27

Li J.-K. Balic J. J. Yu L. Jenkins B. (2017). TLR Agonists as Adjuvants for Cancer Vaccines. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.1024, 195–212. 10.1007/978-981-10-5987-2_9

28

Li W.-H. Li Y.-M. (2020). Chemical Strategies to Boost Cancer Vaccines. Chem. Rev.120, 11420–11478. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00833

29

Liu Y. Wang Z. Yu F. Li M. Zhu H. Wang K. et al (2021). The Adjuvant of α-Galactosylceramide Presented by Gold Nanoparticles Enhances Antitumor Immune Responses of MUC1 Antigen-Based Tumor Vaccines. IjnVol. 16, 403–420. 10.2147/IJN.S273883

30

Nakamura T. Kuroi M. Harashima H. (2015). Influence of Endosomal Escape and Degradation of α-Galactosylceramide Loaded Liposomes on CD1d Antigen Presentation. Mol. Pharmaceutics12, 2791–2799. 10.1021/mp500704e

31

Nath S. Mukherjee P. (2014). MUC1: a Multifaceted Oncoprotein with a Key Role in Cancer Progression. Trends Mol. Med.20, 332–342. 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.02.007

32

Owen A. M. Fults J. B. Patil N. K. Hernandez A. Bohannon J. K. (2021). TLR Agonists as Mediators of Trained Immunity: Mechanistic Insight and Immunotherapeutic Potential to Combat Infection. Front. Immunol.11, 622614. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.622614

33

Pillai K. Pourgholami M. H. Chua T. C. Morris D. L. (2015). MUC1 as a Potential Target in Anticancer Therapies. Am. J. Clin. Oncol.38, 108–118. 10.1097/COC.0b013e31828f5a07

34

Qu W. Li N. Yu R. Zuo W. Fu T. Fei W. et al (2018). Cationic DDA/TDB Liposome as a Mucosal Vaccine Adjuvant for Uptake by Dendritic Cells In Vitro Induces Potent Humoural Immunity. Artif. Cell Nanomedicine, Biotechnol.46, 852–860. 10.1080/21691401.2018.1438450

35

Romerio A. Peri F. (2020). Increasing the Chemical Variety of Small-Molecule-Based TLR4 Modulators: An Overview. Front. Immunol.11, 1210. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01210

36

Shetab Boushehri M. A. Lamprecht A. (2018). TLR4-Based Immunotherapeutics in Cancer: A Review of the Achievements and Shortcomings. Mol. Pharmaceutics15, 4777–4800. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00691

37

Singh R. Bandyopadhyay D. (2007). MUC1: A Target Molecule for Cancer Therapy. Cancer Biol. Ther.6, 481–486. 10.4161/cbt.6.4.4201

38

Smith Korsholm K. Agger E. M. Foged C. Christensen D. Dietrich J. Andersen C. S. et al (2007). The Adjuvant Mechanism of Cationic Dimethyldioctadecylammonium Liposomes. Immunology121, 216–226. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02560.x

39

Supekar N. T. Lakshminarayanan V. Capicciotti C. J. Sirohiwal A. Madsen C. S. Wolfert M. A. et al (2018). Synthesis and Immunological Evaluation of a Multicomponent Cancer Vaccine Candidate Containing a Long MUC1 Glycopeptide. ChemBioChem19, 121–125. 10.1002/cbic.201700424

40

Tang C.-K. Katsara M. Apostolopoulos V. (2008). Strategies Used for MUC1 Immunotherapy: Human Clinical Studies. Expert Rev. Vaccin.7, 963–975. 10.1586/14760584.7.7.963

41

Tang J. Pearce L. O'Donnell-Tormey J. Hubbard-Lucey V. M. (2018). Trends in the Global Immuno-Oncology Landscape. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.17, 783–784. 10.1038/nrd.2018.167

42

Vacchelli E. Galluzzi L. Eggermont A. Fridman W. H. Galon J. Sautès-Fridman C. et al (2012). Trial Watch: FDA-Approved Toll-like Receptor Agonists for Cancer Therapy. Oncoimmunology1, 894–907. 10.4161/onci.20931

43

Wang L. Feng S. Wang S. Li H. Guo Z. Gu G. (2017). Synthesis and Immunological Comparison of Differently Linked Lipoarabinomannan Oligosaccharide-Monophosphoryl Lipid A Conjugates as Antituberculosis Vaccines. J. Org. Chem.82, 12085–12096. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b01817

44

Wang Y.-Q. Zhang H.-H. Liu C.-L. Wu H. Wang P. Xia Q. et al (2013). Enhancement of Survivin-specific Anti-tumor Immunity by Adenovirus Prime Protein-Boost Immunity Strategy with DDA/MPL Adjuvant in a Murine Melanoma Model. Int. Immunopharmacology17, 9–17. 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.04.015

45

Wu J.-J. Li W.-H. Chen P.-G. Zhang B.-D. Hu H.-G. Li Q.-Q. et al (2018). Targeting STING with Cyclic Di-GMP Greatly Augmented Immune Responses of Glycopeptide Cancer Vaccines. Chem. Commun.54, 9655–9658. 10.1039/c8cc04860f

46

Wu X. McFall-Boegeman H. Rashidijahanabad Z. Liu K. Pett C. Yu J. et al (2021). Synthesis and Immunological Evaluation of the Unnatural β-linked Mucin-1 Thomsen-Friedenreich Conjugate. Org. Biomol. Chem.19, 2448–2455. 10.1039/d1ob00007a

47

Wu X. Yin Z. McKay C. Pett C. Yu J. Schorlemer M. et al (2018). Protective Epitope Discovery and Design of MUC1-Based Vaccine for Effective Tumor Protections in Immunotolerant Mice. J. Am. Chem. Soc.140, 16596–16609. 10.1021/jacs.8b08473

48

Yanasarn N. Sloat B. R. Cui Z. (2011). Negatively Charged Liposomes Show Potent Adjuvant Activity when Simply Admixed with Protein Antigens. Mol. Pharmaceutics8, 1174–1185. 10.1021/mp200016d

49

Yin X.-G. Chen X.-Z. Sun W.-M. Geng X.-S. Zhang X.-K. Wang J. et al (2017). IgG Antibody Response Elicited by a Fully Synthetic Two-Component Carbohydrate-Based Cancer Vaccine Candidate with α-Galactosylceramide as Built-In Adjuvant. Org. Lett.19, 456–459. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03591

50

Yu H. Karunakaran K. P. Jiang X. Shen C. Andersen P. Brunham R. C. (2012). Chlamydia Muridarum T Cell Antigens and Adjuvants that Induce Protective Immunity in Mice. Infect. Immun.80, 1510–1518. 10.1128/IAI.06338-11

51

Zhang R. Billingsley M. M. Mitchell M. J. (2018). Biomaterials for Vaccine-Based Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Controlled Release292, 256–276. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.10.008

52

Zhou S.-H. Zhang R.-Y. Zhang H. Liu Y.-L. Wen Y. Wang J. et al (2022). RBD Conjugate Vaccine with Built-In TLR1/2 Agonist Is Highly Immunogenic against SARS-CoV-2 and Variants of Concern. Chem. Commun.2022. 10.1039/D1CC06520C

53

Zhou Z. Mandal S. S. Liao G. Guo J. Guo Z. (2017). Synthesis and Evaluation of GM2-Monophosphoryl Lipid A Conjugate as a Fully Synthetic Self-Adjuvant Cancer Vaccine. Sci. Rep.7, 017–11500. 10.1038/s41598-017-11500-w

54

Zhu H. Wang K. Wang Z. Wang D. Yin X. Liu Y. et al (2022). An Efficient and Safe MUC1-Dendritic Cell-Derived Exosome Conjugate Vaccine Elicits Potent Cellular and Humoral Immunity and Tumor Inhibition In Vivo. Acta Biomater.138, 491–504. 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.10.041

Summary

Keywords

DDA, MPLA, MUC1, lipoglycopeptide, liposome, cancer vaccine

Citation

Du J-J, Zhou S-H, Cheng Z-R, Xu W-B, Zhang R-Y, Wang L-S and Guo J (2022) MUC1 Specific Immune Responses Enhanced by Coadministration of Liposomal DDA/MPLA and Lipoglycopeptide. Front. Chem. 10:814880. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2022.814880

Received

15 November 2021

Accepted

17 January 2022

Published

04 February 2022

Volume

10 - 2022

Edited by

Amit Sharma, Central Scientific Instruments Organization (CSIR), India

Reviewed by

Guo Huichen, Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute (CAAS), China

Rashmi Kumar, Institute of Microbial Technology (CSIR), India

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Du, Zhou, Cheng, Xu, Zhang, Wang and Guo.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Long-Sheng Wang, wls@mail.tsinghua.edu.cn; Jun Guo, jguo@mail.ccnu.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

This article was submitted to Chemical Biology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Chemistry

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.