Abstract

Chicoric acid has been widely used in food, medicine, animal husbandry, and other commercial products because of its significant pharmacological activities. However, the shortage of chicoric acid limits its further development and utilization. Currently, Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench serves as the primary natural resource of chicoric acid, while other sources of it are poorly known. Extracting chicoric acid from plants is the most common approach. Meanwhile, chicoric acid levels vary in different plants as well as in the same plant from different areas and different medicinal parts, and different extraction methods. We comprehensively reviewed the information regarding the sources of chicoric acid from plant extracts, its chemical synthesis, biosynthesis, and bioactive effects.

1 Introduction

Current research on chicoric acid focuses primarily on medicinal, chemical, natural agricultural production, and food and accounts for 50%, 18%, 13%, and 18%, respectively. Chicoric acid belongs to caffeic acid derivatives and its molecular formula is C22H18O12. Chicoric acid is soluble in ethanol, methanol, dioxane, acetone, and hot water; slightly soluble in ethyl acetate and ether; and insoluble in ligroin, benzene, and chloroform (Scarpati and Oriente, 1958). There are two chiral carbon atoms in this structure, so chicoric acid is divided into levorotatory-chicoric acid (L-chicoric acid), dextrorotatory-chicoric acid (D-chicoric acid), and meso-chicoric acid (meso-chicoric acid) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Three optical structures of chicoric acid.

Chicoric acid is a rare and valuable functional food ingredient with no obvious dose dependence, no overdose side effects, and no contraindications and drug interactions. Chicoric acid has been widely used in medicines, nutritional supplements, and health foods due to its promising pharmacological effects in regulating glucose and lipid metabolism; anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-aging properties, and against digestive system diseases (Peng et al., 2019). Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench, the main plant material of chicoric acid, has a 400-year history of use in Europe and America. However, the shortage of chicoric acid limits its further development and utilization. So, this article focuses on systematically summarizing chicoric acid sources, such as chemical synthesis and biosynthesis, and further elaborates on resource distribution and content of chicoric acid in different plants, aiming to find a beneficial pathway of chicoric acid production for further development and utilization (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Chemical structure, bioactive effects, and acquisition pathways of chicoric acid.

2 Natural Occurrence of Chicoric Acid

Plants containing chicoric acid are rich in resources and widely distributed, so chicoric acid has been utilized as an alternative medicine or a food supplement for quite some time (Street et al., 2013). Chicoric acid levels in different plants and different parts of the same plant often differ significantly. However, there are few reports on chicoric acid levels and different plant resource distributions. At present, E. purpurea is the main crude material for the extraction of chicoric acid, but the shortage of crude material limits further development and utilization. In order to solve that problem, it is necessary to analyze the resource distribution and chicoric acid levels in different plants.

2.1 Plants the Principal Sources of Chicoric Acid

At least 25 families, 63 genera and species, in the plant kingdom contain chicoric acid (Grignon-Dubois and Rezzonico, 2013), there is no substantial guidance due to the lack of detailed information on plant resources. For the convenience of discussion, this article has divided chicoric acid–containing plants into angiosperms, ferns, and other categories (Table 1) and discussed the resource distribution, historical changes, and usage of chicoric acid.

TABLE 1

| Plant names | Family | Genus | Resource distribution | Morphological classification | Plant parts | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench | Asteraceae | Echinacea | North America and China | Perennial herb | Aerial parts and roots | Shah et al. (2007); Wills and Stuart (1999); Wang et al. (2016) |

| Pterocypsela laciniata (Houtt.) Shih | Asteraceae | Pterocypsela | East Asia and Southeast Asia | Perennial herb | Leaves | He (2012); Ke et al. (2015) |

| Cichorium intybus L. | Asteraceae | Cichorium | Mediterranean region and Southwest Asia | Perennial herb | Aerial parts and roots | Carazzone et al. (2013); Mascherpa et al. (2012); Zhou (2014); Xu (2008) |

| Lactuca sativa L. | Asteraceae | Lactuca | Temperate areas | Annual or biennial plant | Lettuce head and leaves | Wei et al. (2021); Lin (2018); Zhang (2018); Degl et al. (2008); Vidal et al. (2019) |

| Taraxacum mongolicum Hand.-Mazz. | Asteraceae | Taraxacum | Temperate areas | Perennial herb | Aerial parts and roots | Nie et al. (2020); Wang et al. (2017); Chen et al. (2020) |

| Sonchus brachyotus DC. | Asteraceae | Sonchus | Northwest and South of China | Annual or perennial herb | Aerial parts and roots | Liu (2016) |

| Sonchus oleraceus L. | Asteraceae | Sonchus | Northeast, North, Central, and South China | Annual or biennial herb | Leaves | Ma et al. (2011) |

| Ixeris chinensis (Thunb.) Nakai | Asteraceae | Ixeris | North, South, and East China | Perennial herb | Aerial parts and roots | Dong et al. (2008) |

| Hypochaeris radicata L. | Asteraceae | Hypochaeris | Europe and China | Perennial herb | Flowering heads | Ye et al. (2007); Zidorn et al. (2005); Ortiz et al. (2008) |

| Bidens tripartita L. | Asteraceae | Bidens | China | Perennial plant | Aerial parts | Pozharitskaya et al. (2010) |

| Rabdosia rubescens (Hemsl.) Hara | Lamiaceae | Rabdosia | China | Small shrub | Leaves | Zhao et al. (2013) |

| Orthosiphon stamineus Benth. | Lamiaceae | Orthosiphon | India, Malaysia, China, Australia, and the Pacific area | Perennial herb | Leaves | Ameer et al. (2012); Guo et al. (2019b) |

| Echinodorus grandiflorus | Alismataceae | Echinodorus | Central America and South Brazil | Perennial marsh plant | Leaves | Han and Shi (2009); Marques et al. (2017) |

| Arachis hypogaea L. | Leguminosae | Arachis | Tropics and Subtropics | Annual plant | Leaf terminals | Krishna et al. (2015); Zhou and Meng (2017) |

| Equisetum arvense L. | Equisetaceae | Equisetum | Europe, Asia, and North America | Perennial herb | Sprouts and gametophytes | Veit et al. (1991); Veit et al. (1992); Xia (2019) |

| Lygodium japonicum (Thunb.) Sw. | Lygodiaceae | Lygodium | Australia and China | Perennial climbing plant | Frond | Yang et al. (2021) |

| Zostera marina L. | Potamogetonaceae | Zostera | Temperate northern hemisphere | Perennial herb | Leaves | Min et al. (2019); Pilavtepe et al. (2012) |

Plants that are the principal sources of chicoric acid.

2.1.1 Angiospermae

Chicoric acid is widely distributed in dicotyledons of Angiospermae, namely, Asteraceae, Lamiaceae, Rosaceae, Alismataceae, Cucurbitaceae, and others. Many reports have focused on the study of E. purpurea, Pterocypsela laciniata, and Cichorium intybus of the Asteraceae family.

2.1.1.1 Asteraceae

There are eight species and several varieties of the Echinacea, among which E. purpurea, Echinacea angustifolia (DC) Hell., and Echinacea pallida (Nutt.) are widely used in medicine. E. purpurea is a perennial herb with a medical history dating back more than 300 years (Shah et al., 2007) and was introduced in China as a flower in the 1970s. It is currently cultivated on a large scale in China as a medicinal plant. E. purpurea is widely used in drug materials, nutritional supplements, and health foods. Chicoric acid is often used as an indicator component in the quality evaluation of materials and preparations (Wills and Stuart, 1999; Xu et al., 2006; Sun, 2011; Chen et al., 2012; Han et al., 2013; Han et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016).

There are eight species and one variety species of Pterocypsela, located primarily in East Asia and Southeast Asia. China is rich in resources, most of which are distributed in the east. As a common weed, Pterocypsela has strong fecundity and adaptability to harsh environments (He, 2012; Ke et al., 2015). P. laciniata is a perennial herb of Pterocypsela with abundant plant resources and chicoric acid.

Cichorium originated in ancient Rome and Greece and was distributed in the Mediterranean and Southwest Asia. Of the eight total species, three exist in China. C. intybus, a perennial herb of Cichorium, was cultivated as a high-grade vegetable in the 19th century. It can be cooked into lettuce (Carazzone et al., 2013) and used for health care. Chicoric acid is an important index for the quality evaluation of C. intybus (Mascherpa et al., 2012; Zhou, 2014), and the amount of chicoric acid differs significantly in different regions and in different areas of the same plant (Xu, 2008).

Lactuca sativa, an annual or biennial vegetable crop, is widely cultivated in temperate areas around the globe. An in-depth analysis did not reveal the origin of L. sativa, but it was first domesticated near the Caucasus (Wei et al., 2021). A variety of cultivation types gradually formed after long-term directional selection and cultivation (Lin, 2018), which were divided into six cultivation types (Zhang, 2018). The content of chicoric acid varied significantly in response to different storage environments (Degl et al., 2008; Oh et al., 2009; Becker et al., 2015; Vidal et al., 2019).

There are more than 2,000 species of the Taraxacum, widely distributed from the temperate areas in the northern hemisphere to the central subtropical regions and South America (Gong et al., 2001). Dandelion is a perennial herb of Taraxacum, and there are 20 species used as medicinal plants in China. Large-scale artificial cultivation has continued in China because of its low growing environment requirements, simple management techniques, and high planting yield (Chen et al., 2020). Taraxacum mongolicum and Taraxacum sinicm Kitag reportedly contain chicoric acid, but there are few studies on the topic (Wang et al., 2017; Nie et al., 2020).

There are 50 species of Sonchus worldwide, located mostly in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Mediterranean/Atlantic islands (Liu, 2016). Sonchus brachyotus, an annual or perennial herb of Sonchus, sees extensive use in northwest and southern China. S. oleraceus, distributed in Northeast, North, Central, and Southern China (Ma et al., 2011), is not only easy to cultivate but also rich in nutrition. Sonchus asper (L.) Hill and S. oleraceus also contain chicoric acid, but the amount remains unclear.

There are 20 species of Ixeris in North, South, and East China. Ixeris chinensis and Ixeris sonchifolia Hance belong to Ixeris. The perennial herb I. chinensis has been used as a traditional Chinese herbal medicine for thousands of years. I. sonchifolia has been cultivated artificially recently in many areas. Chicoric acid is often used as one of the quality control indexes of these plants (Dong et al., 2008; Zhao and Jiang, 2016).

Hypochaeris radicata is a perennial herb, and studies have indicated that the oldest populations of H. radicata originated in Europe and expanded via at least three migratory routes to other countries (Ortiz et al., 2008) and have been found in Zhejiang and Guizhou of China (Ye et al., 2007). The species are largely used for both food and medicine in Italy. One study has shown a positive correlation between the altitude of the growth environment and the content of chicoric acid (Zidorn et al., 2005). Bidens tripartita, a perennial plant, is widely distributed throughout China. Previous studies on B. tripartita confirmed the presence of chicoric acid in this plant (Pozharitskaya et al., 2010).

2.1.1.2 Lamiaceae

Rabdosia rubescens, a small shrub of Rabdosia, is native to the valley of the Yellow River and the Yangtze River, as well as the Jiyuan Taihang Mountain and Wangwu Mountain in Henan province. The growing environment is characterized by hillsides and woodlands. Recently, the artificial planting of R. rubescens in Jiyuan City has expanded, with yields accounting for 95% of the total Chinese output. R. rubescens in Jiyuan City is a “national geographic product.” In China, R. rubescens is consumed as a famous traditional medicinal herb and tea (Zhao et al., 2013). Although the plant contains chicoric acid, not much research exists on this.

Ocimum basilicum L., a perennial herb of the Ocimum, has more than 150 species around the world. O. basilicum, originated in the warm tropical climates of India, Africa, and southern Asia and has been cultivated worldwide as an aromatic crop and ornamental plant. Some research reported that levels of chicoric acid varied from 0.09 to 0.16 mg/g in dried samples (Kwee and Niemeyer, 2011).

Orthosiphon stamineus belongs to a perennial Orthosiphon herb, occurs widely in India, Malaysia, China, Australia, and the Pacific area. O. stamineus is a valued medicinal plant in traditional folk medicine (Ameer et al., 2012). Leaves of this plant find use in tea, and the rest of the dried plant is used for medicine. Chicoric acid is also the most important bioactive component of this plant (Guo et al., 2019a).

2.1.1.3 Other Genera

Chicoric acid has been detected in other plants from different families, namely, Echinodorus grandiflorus, Cucurbita pepo L. (Iswaldi et al., 2013), Arachis hypogaea, Pulsatilla chinensis (Bge.) Regel (Zhang et al., 2008), and Pyracantha fortuneana (Maxim.) Li. However, acid levels in these plants are unknown and require additional research.

E. grandiflorus, a perennial marsh plant of the Alismataceae, originates from Central America and southern Brazil (Han and Shi, 2009) and has medicinal uses (Marques et al., 2017). C. pepo is a trailing annual herb of the Cucurbitaceae. A. hypogaea, an annual plant of the Leguminosae, is widely distributed in the tropics and subtropics. A. hypogaea plays an important role in the world agricultural economy not only for vegetable oil but also as a source of proteins, minerals, and vitamins (Krishna et al., 2015). A. hypogaea is the highest yielding oil crop in China (Zhou and Meng, 2017).

P. fortuneana is an evergreen shrub or small tree of the Rosaceae. Because of its strong adaptability, P. fortuneana thrives with high yields and is widely distributed in Asia and Europe. Chicoric acid was also detected in the fruit of P. fortuneana. P. chinensis, belonging to the genus Pulsatilla of the buttercup family, is also widely distributed in Europe and Asia. Eleven of the 43 species of this plant have been found in Liaoning, Hebei, and Henan.

2.1.2 Pteridophyta

Chicoric acid may be a specific chemical component in Pteridophyta, because chicoric acid has been detected in 23 of 29 species (Hasegawa and Taneyama, 1973). Pteridaceae, Dryopteridaceae, Equisetaceae, and other Pteridophyta (Cao et al., 2013) have been cultivated for health care.

Equisetum arvense, a perennial herb of Equisetaceae, is native to Europe, Asia, and North America and widely distributed in Heilongjiang (Xia, 2019). Meso-chicoric acid was isolated from the sprouts (fertile) and gametophytes of E. arvense (Veit et al., 1991; Veit et al., 1992), but little reports about the content.

Pteris cretica L. and Onychium japonicum (Thumb.) Kze. belong to Pteridaceae. P. cretica is a perennial evergreen herb. O. japonicum occurs primarily in Taiwan, Japan, Korea, and other Asian countries and is used to treat enteritis, jaundice, flu, chronic gastritis, and fever. Dryopteris erythrosora (D.C. Eaton) Kuntze is a species of Dryopteridaceae native to China and Japan and distributed throughout East Asia. Chicoric acid was detected in the frond of these plants.

Lygodium japonicum, a perennial climbing plant of Lygodiaceae, mainly distributed in Australia and the southwestern area of China (Yang et al., 2021). The entire L. japonicum plant is used to treat various inflammatory diseases. Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn is a serious invasive weed of upland and marginal lands in many parts of the world (Stewart et al., 2008); however, chicoric acid has been detected in it.

2.1.3 Other Categories

The ocean is a potential source of various raw materials for food and drugs. Compared with terrestrial plants, marine plants with large biomass have obvious advantages as a source of chemical raw materials. Cymodocea nodosa, Syringodium fifiliforme Kütz, and Posidonia oceanica (L.) Delile also contain chicoric acid.

P. oceanica occurs primarily in the Mediterranean Sea. Phenolic compounds are the major metabolites and chicoric acid accounts for 80–89% of the total phenolics. Due to the significant content of chicoric acid, more and more investigations on this plant have taken place (Haznedaroglu and Zeybek, 2007). However, this species is endangered because of anthropogenic effects. C. nodosa is one of the most important macrophytes in the Mediterranean Sea and eastern Atlantic coasts. Some studies have shown that the content of chicoric acid varies in different parts of the plant (Grignon-Dubois and Rezzonico, 2013).

Zostera marina, the most widespread seagrass species of Potamogetonaceae throughout the temperate northern hemisphere (Min et al., 2019), is the largest seagrass meadow in the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea areas in China. Although chicoric acid has been detected in the leaves of Z. marina, the data are incomplete (Pilavtepe et al., 2012). S. fifiliforme is distributed across the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico as seagrass, and it has been reported that S. fifiliforme contains chicoric acid, but no exact statistics are available (Nuissier et al., 2010).

2.2 Methods of Chicoric Acid Extractions and Its Contents in Plants

The amount of chicoric acid is closely related to the plant source, medicinal parts, harvest period, processing, and extraction methods. So far, a systematic study on chicoric acid levels has not been found. Although chicoric acid comes from a variety of plants, the selection of safe and economical plant sources requires further research. By analyzing the relationship between factors and the content of chicoric acid, the distribution of chicoric acid in the plant can be preliminarily predicted, which provides a basis for further development of chicoric acid.

2.2.1 Content of Chicoric Acid in Echinacea purpurea

E. purpurea is the raw material for chicoric acid extraction in most studies. Several factors impact chicoric acid levels (Table 2). For 2-year old E. purpurea, the content of chicoric acid is higher in flowers than in other parts during flowering (Wang et al., 2002). The content of chicoric acid in the stems, leaves, and flowers were 9.7%, 44.7%, and 23.6%, respectively (Li et al., 2011). The chicoric acid levels maximized during flowering and provided the best harvest period for E. purpurea (Innocenti et al., 2005).

TABLE 2

| Extraction methods | Medicinal origin | Medicinal parts | Extraction conditions | Yield of chicoric acid (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reflux extraction | Shaanxi | Dried aboveground parts | Extraction was performed 3 times with 1.5 h each time | 1.03 | Zhong et al. (2010) |

| Xinjiang | All dried grasses | 15 times; 40% ethanol, 3 times, 2 h each time | 0.55 | Ma et al. (2014) | |

| The extraction temperature was 90°C | |||||

| Guangdong | All dried grasses | 8 times; 80% ethanol, 3 times, 1 h each time | 1.09 | Zhang et al. (2008) | |

| Hebei | Dried flowers | 20 times; 20% ethanol, 2 times, 2 h each time, extraction temperature was 90°C | 0.75 | Sun et al. (2019) | |

| Shandong | Dried flowers | 20 times; 60% ethanol, 2 times, 2 h each time, extraction temperature of 70°C | 2.30 | Cheng et al. (2018) | |

| Ultrasonication extraction | Anhui | All dried grasses | 8 times; 55% ethanol was extracted twice, 45 min each | 1.22 | Cao et al. (2010) |

| Beijing | Dried roots, stems, leaves, flowers, aboveground parts | 125 times; methanol–0.5% phosphoric acid (4:1) solution was extracted by ultrasound for 40 min | 0.90 (root) | Wang et al. (2002) | |

| 0.43 (stem) | |||||

| 1.84 (leaf) | |||||

| 2.15 (flower) | |||||

| 1.05 (overground part) | |||||

| Shandong | Dried roots, stems, leaves, flowers | 125 times; 70% methanol, ultrasound 30 min | 1.28 (root) | Han et al. (2014) | |

| 0.36 (stem) | |||||

| 2.32 (leaf) | |||||

| 2.11 (flower) | |||||

| Shandong | Dried aboveground parts | 62.5 times; 70% methanol was extracted by ultrasonography for 3 times, 10 min each | 2.02 | Xin et al. (2012) | |

| Guangdong | Dried roots, stems, leaves, flowers, whole grasses | 62.5 times; methanol–0.5% phosphoric acid aqueous solution (4:1) was extracted by ultrasound for 60 min | 1.21 (root) | Li et al. (2011) | |

| 0.07 (stem) | |||||

| 0.56 (leaf) | |||||

| 0.25 (flower) | |||||

| 0.33 (whole herb) | |||||

| Ultrasonic microwave co-extraction method | Tianjin | Fresh roots | 25 times; 50% ethanol, ultrasound for 90 s without microwave power; the extraction power was 300 W and the extraction time was 660 s | 0.02 | Wang et al. (2015) |

| Spray extraction | Shaanxi | All dried grasses | Spray 4 times 70% ethanol at 20 kg pressure for 3 min | 0.53 | Zhao and Yang (2018) |

| Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction method | Guangdong | Dried flowers | CO2 was extracted with 40% ethanol entrainment at a flow rate of 25 kg/hand a pressure of 30 MPa for 2 h at 60°C | 1.06 | Lin et al. (2011) |

Comparison of chicoric acid levels in Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench.

2.2.2 Chicoric Acid Levels in Other Plant Resources

Related references have reported that the content of chicoric acid in P. laciniata is 26.1 mg/g, 2.2 times higher than in E. purpurea (Ke, 2015). Chicoric acid levels varied with different plant areas and medicinal parts in C. intybus, but chicoric acid levels above ground from Jiangsu were higher (Innocenti et al., 2005). The content of chicoric acid in I. chinensis and S. brachyotus varied greatly, the reason for which may be related to medicinal parts and picking time (Liu, 2016), drying process and preparation method (Sun, 2011), and extraction conditions and other factors (Xin et al., 2012). A summary of these studies appears in Table 3.

TABLE 3

| Herbs | Medicinal origin | Medicinal parts | Extraction methods | Extraction conditions | Yield of chicoric acid (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cichorium intybus L. | Xinjiang | Dried stem | Ultrasonication extraction | 21 times; 50% ethanol, ultrasound at 60°C for 50 min (180 W) | 0.15 | Meng et al. (2015); Meng (2016) |

| Jiangsu | Dried overground part | Ultrasonication extraction | 12 times; 54% ethanol, ultrasound 30 min (40 w) | 0.15 | Xu (2008) | |

| Jiangsu | Dried overground part | Reflux extraction | 24 times; 54% ethanol was refluxed at 90°C for 1 h | 0.15 | Xu (2008) | |

| Netherlands | Dried overground part | Dried overground part | Reflux of 60 times 70% methanol at 60°C for 1 h | 0.88 | Hua et al. (2011) | |

| Ixeris chinensis (Thunb.) Nakai | Shanxi | Dried overground part | Reflux extraction | 50 times; 70% ethanol heated reflux extraction 1 h | 0.77–1.14 | Liu (2016) |

| Sonchus brachyotus DC. | Shanxi | Dried overground part | Reflux extraction | 50 times; 70% ethanol heated reflux extraction 1 h | 0.34–2.69 | Liu (2016) |

| Pterocypsela laciniata (Houtt.) Shih | Jiangsu | Dried leaves | Ultrasonication extraction | Ultrasonic extraction with 100 times 80% ethanol solution at 45°C for 70 min | 2.61 | Liu (2016) |

| Sonchus asper (L.) Hill | Jiangsu | Dried leaves | Ultrasonication extraction | Ultrasonic extraction with 100 times 80% ethanol solution at 45°C for 70 min | 1.50 | Ke (2015) |

Comparison of the content of chicoric acid in different plants.

3 Chemical Synthesis of Chicoric Acid

E. purpurea is often used as a crude material for chicoric acid production, but a large-scale preparation of high purity chicoric acid has not been reported, which limits its further development and utilization. This requires a synthetic method as an alternative to complement natural plant extraction. In this article, synthetic methods to produce chicoric acid are summarized and the characteristics of each method are compared to provide new synthetic routes.

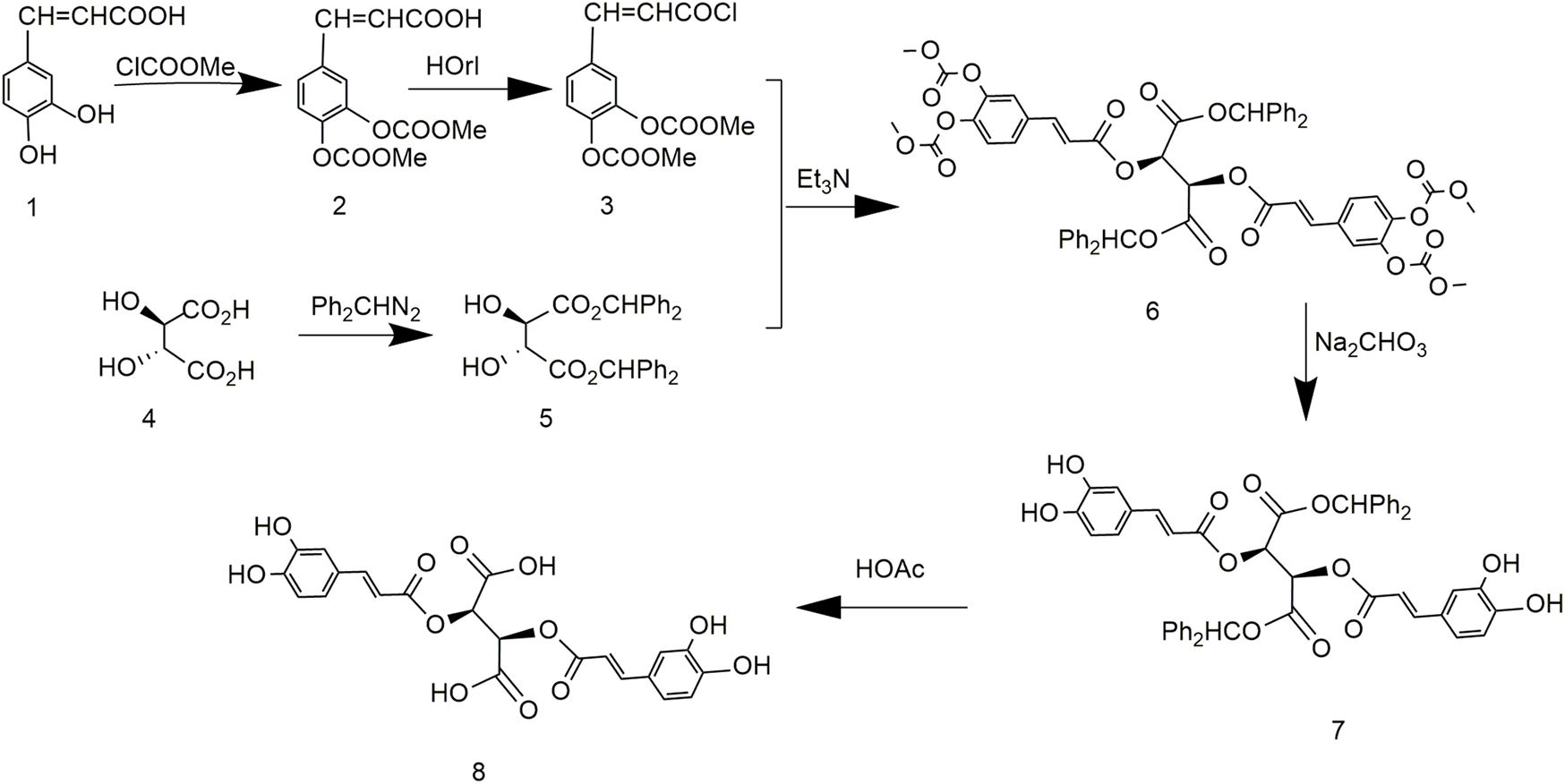

3.1 Chicoric Acid Synthesis Using (E)-3-(2-Oxo-3a,7a-Dihydrobenzo[d][1,3]Dioxol-5-yl)Acryloyl Chloride and (2R,3S)-2,3-Dihydroxysuccinic Acid

In 1958, chicoric acid was first extracted from C. intybus and its different configurations were chemically synthesized. L-chicoric acid was synthesized via caffeoyl chloride and D-tartaric acid and deprotection of acetic acid (Figure 3). D-chicoric acid, L-chicoric acid, and meso-chicoric acid were synthesized by reactions with L-tartaric acid, D-tartaric acid, and meso-tartaric acid, respectively. These syntheses were simple, but the purity of chicoric acid was too low. In addition, the use of the unstable caffeoyl chloride led to low yields of chicoric acid (Scarpati and Oriente, 1958).

FIGURE 3

Chemical synthesis pathway 1 of chicoric acid.

3.2 Chicoric Acid Synthesis Using Di-Tert-Butyl (2R,3S)-2,3-Dihydroxysuccinate and (E)-4-(3-Chloro-3-Oxoprop-1-En-1-yl)-1,2-Phenylene Diacetate

Based on previous research, the optimized process simplified production and occurred under mild reaction conditions (Kulangiappar et al., 2014). First, tert-butyl tartrate was obtained by protecting the carboxyl group of tartaric acid with a tert-butyl group followed by protecting the phenolic hydroxyl of caffeic acid with an acetyl group to produce diacetyl caffeic acid. Then, compound 2 reacted with compound 3, and finally the protective group of previous reaction was removed to obtain L-chicoric acid (Figure 4). The reaction conditions of this method are mild, but L-tert-butyl tartrate is difficult to synthesize. Many by-products and low yields limit large-scale production.

FIGURE 4

Chemical synthesis pathway 2 of chicoric acid.

3.3 Chicoric Acid Synthesis Using Dibenzhydryl (2R,3R)-2,3-Dihydroxysuccinate and (Z)-4-(3-Chloro-3-Oxoprop-1-En-1-yl)-1,2-Phenylene Dimethyl Bis(Carbonate)

King et al. (1999) reported a method for synthesizing chicoric acid with different configurations by protecting tartaric acid with diphenylmethyl. The synthesis of chicoric acid was mainly carried out in two directions (Figure 5). Diphenylmethane protected the carboxyl group of L-tartaric acid, and the phenolic hydroxyl group of caffeic acid was protected by ClCOOMe to obtain 3,4-cyclocarbonate of caffeoyl chloride. The two protected components reacted, and the protecting groups were removed to obtain L-chicoric acid. Too many steps lead to an overall yield of 33.3%. In addition, the carboxyl-protected crude material of tartaric acid diphenyl diazomethane was unstable to the point of explosion during synthesis, which seriously curtails industrial adaptation.

FIGURE 5

Chemical synthesis pathway 3 of chicoric acid.

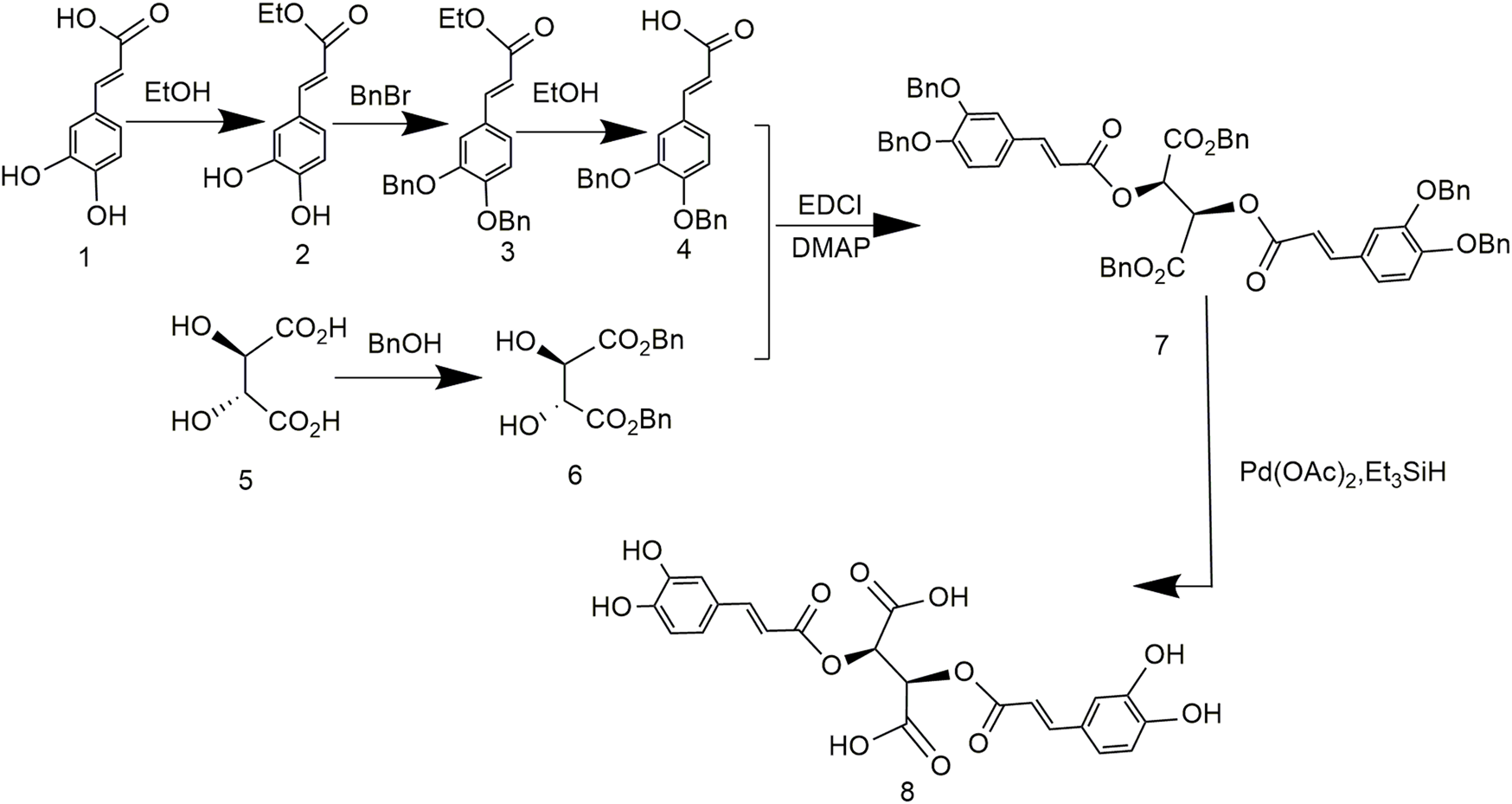

3.4 Chicoric Acid Synthesis Using Dibenzyl (2R,3R)-2,3-Dihydroxysuccinate and (E)-3-(3,4-Bis(Benzyloxy)Phenyl)Acrylic Acid

To address problems caused by expensive tartaric acid derivatives and poor reproducibility, the synthesis of chicoric acid was further optimized. Both carboxyl groups of tartaric acid and the phenolic hydroxyl group of caffeic acid were protected by benzylation, followed by esterification and reduction to obtain L-chicoric acid (Figure 6). This synthetic route used heavy metal salts, which increased the production cost and led to heavy metal residues. In addition, the by-products affected drug quality (Lamidey et al., 2002).

FIGURE 6

Chemical synthesis pathway 4 of chicoric acid.

3.5 Chicoric Acid Synthesis Using (E)-3-(3,4-Diacetoxyphenyl)Acrylic Acid and (2R,3R)-2,3-Dihydroxysuccinic Acid

Chicoric acid synthesis was improved based on a previous work to simplify the route and improve the purity (Zhou, 2014). The phenolic hydroxyl of caffeic acid was protected by an acetyl group and reacted with L-tartaric acid to obtain (2R,3R)-2,3-bis(((E)-3-(3,4-diacetoxyphenyl)acryloyl)oxy)succinic acid. LiOH hydrolysis removed the protecting group; the metal ions and chicoric acid formed a stable complex and were hydrolyzed to obtain relatively pure chicoric acid (Figure 7). Although the purity of the product was 99.7%, it did not maximize the yield or reduce the cost.

FIGURE 7

Chemical synthesis pathway 5 of chicoric acid.

3.6 Chicoric Acid Synthesis Using (E)-Hypochlorous (E)-3-(2-Oxidobenzo[d][1,3,2]Aioxathiol-5-yl)Acrylic Anhydride and (2R,3R)-2,3-Dihydroxysuccinic Acid

To solve the problem of high cost and low yield, the synthesis of chicoric acid was optimized, and its crystal shape studied (Tian et al., 2021). The product of caffeic acid and sulfoxide chloride reacted with L-tartaric acid to yield L-gesnerate sulfonate. After removing the protecting group in an alkaline solution, L-chicoric acid was obtained (Hunan Normal University, Changsha, 2021; Figure 8). After further crystallization, the yield and purity of chicoric acid were 80.5% and 98.5%, respectively. Although the purity and yield of the product increased, the process was still cumbersome.

FIGURE 8

Chemical synthesis pathway 6 of chicoric acid.

The structure of chicoric acid was obtained by intermolecular esterification of tartaric acid and two molecules of caffeic acid. Because both tartaric acid and caffeic acid contained hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, side reactions readily occurred. Therefore, the most common synthetic pathway utilized protective groups to protect phenolic hydroxyl groups of caffeic acid and carboxyl groups of tartaric acid before esterification. The difference lies in the selection of raw materials and the different reagents to protect phenolic hydroxyl groups of tartaric acid. These protecting groups include tert-butyl, benzyl, or carboxyl benzyl to protect tartaric acid, while the caffeic acid phenol hydroxyl was protected by acetyl, benzyl ethyl, oxygen acyl, or metal ions. Despite the myriad synthetic methods, none brought higher quality chicoric acid in high purity, yield, and economic and environmental protection.

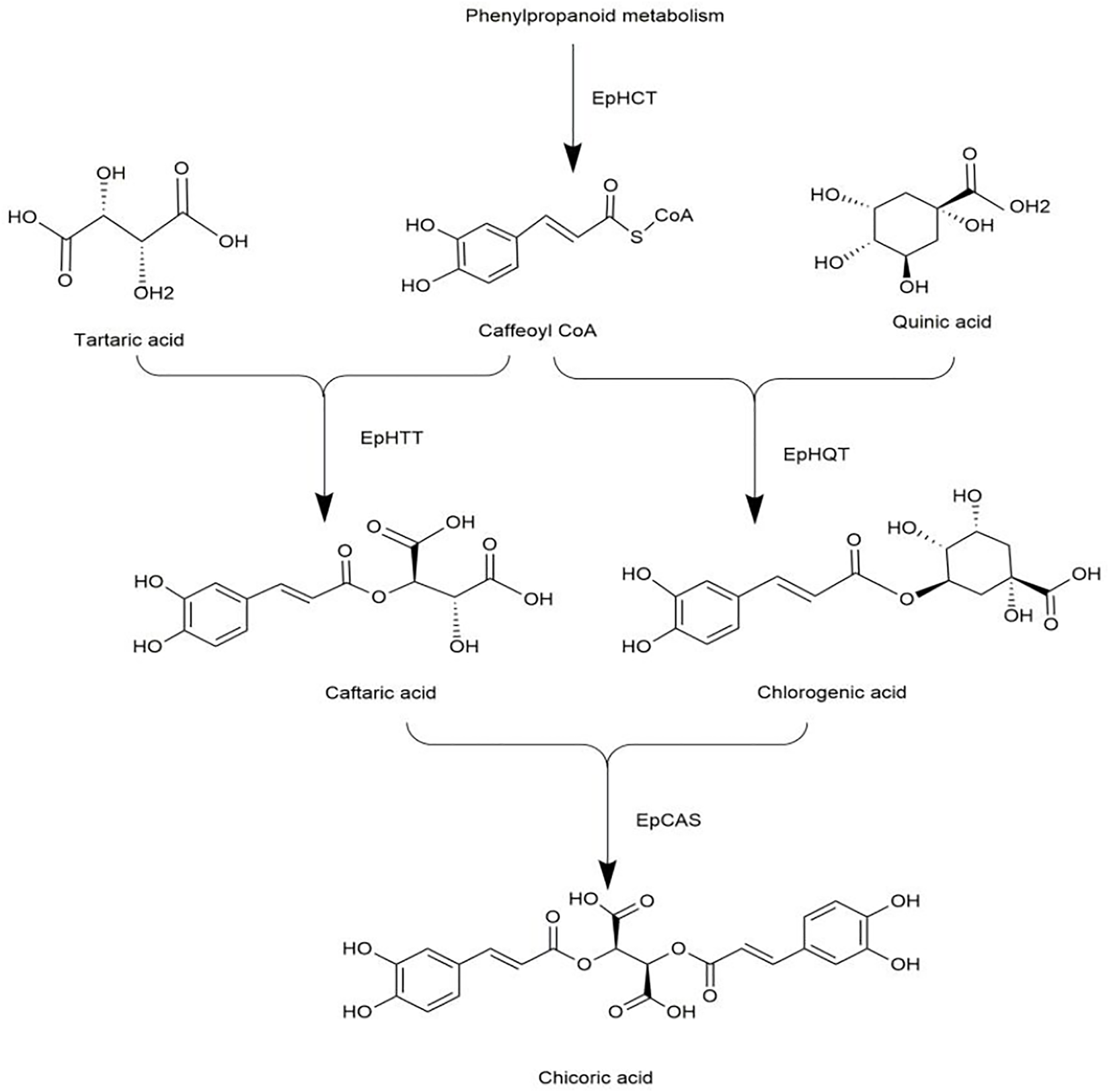

4 Biosynthesis of Chicoric Acid

Chicoric acid is a phenolic acid and generally forms via the shikimic acid‐phenylpropanoid pathway (Kuhnl et al., 1987; Petersen et al., 2009). Understanding what factors regulate the distribution of chicoric acid in plants may help regulate chicoric acid accumulation by altering certain conditions. Although there are many studies on the biosynthetic pathway of chicoric acid, its mechanism remains unclear.

Recently, a study filled this gap by reporting the biosynthetic pathway of chicoric acid in Echinacea (Fu et al., 2021). The biosynthesis of chicoric acid occurs in three main stages. Firstly, phenylpropanoid reacts to form caffeoyl CoA via the enzyme EpHCT. Secondly, EpHTT and EpHQT were responsible for the biosynthesis of caftaric acid and chlorogenic acid in the cytosol, respectively. Finally, caftaric acid and chlorogenic acid were transferred from the cytosol into vacuole, and chicoric acid was synthesized via EpCAS (Figure 9). The biosynthetic pathway of chicoric acid production has been reprogrammed in tobacco, but its applicability in other species needs additional study.

FIGURE 9

Biosynthetic pathway of chicoric acid.

5 Bioactive Effects

Chicoric acid has a long history of clinical use and can effectively treat a variety of diseases. Because of this, numerous studies that have focused on chicoric acid have been conducted on the biological activities of both in vitro and in vivo models. Chicoric acid has long attracted attention as a medication and nutraceutical to improve health based on its anti-inflammation (Liu, 2016; Liu et al., 2017a; Liu et al., 2017b; Tsai et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020), glucose and lipid homeostasis (Kim et al., 2017; Lipchock et al., 2017), neuroprotection effects (Bekinschtein et al., 2008; Kour and Bani, 2011a), anti-aging effects (De Winter, 2015; Peng et al., 2019), and antioxidant and immune-stimulating properties (Kour and Bani, 2011b; Schlernitzauer et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017; Jia et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2018). In addition, its antivirus properties, such as immunodeficiency viruses (Healy et al., 2009; Crosby et al., 2010; Nobela et al., 2018), herpes simplex viruses (Langland et al., 2018), and respiratory syncytial virus (Zhang et al., 2021) are particularly significant. Tables 4 and 5 summarize these studies.

TABLE 4

| Disorders | Models | Dose (μM) | Duration (h) | Effects | Suggested mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | HUVECs | 100 | 24 | ↓ cell apoptosis | (+) the AMPK signaling pathway; ↓ Iκ-Bα; ↓ NF-κB; ↓ iNOS; ↓ IL-1β; ↓ p-eNOS | Ma et al. (2021) |

| ↓ p65 NF-κB nuclear translocation | ||||||

| ↓ oxidative/nitrative stresses | ||||||

| PC-12 cells | 10 and 20 | 24 | ↓ misfolding; ↓ fibrillation of hIAPP; ↓ aggregation | ↓ Cytotoxicity; ↑ biocompatibility | Luo et al. (2020) | |

| Lipid metabolism | HepG2 human hepatoma | 100 and 200 | 24 | ↓ lipid accumulation | (−) SREBP-1/FAS signaling pathways; (+) PPARa/UCP2 signaling pathways | Mohammadi et al. (2020) |

| HepG2 human hepatoma | 10 and 20 | 24 | ↓ lipid accumulation; ↓ oxidative stress; ↓ inflammation | ↑ AMPK; ↑ Nrf2; ↓ NF-κB | Ding et al. (2020) | |

| Inflammation | PBMCs (T2DM patients) | 50 | 6 | ↓ inflammation | ↓ IL-6; ↑ SIRT1; ↑ pAMPK | Sadeghabadi et al. (2019) |

| SH-SY5Y cells | 80 | 12 | (−) inflammatory factor release; ↑ mitochondrial function and energy metabolism | ↑ PGC-1α; ↑ SIRT1; ↑ pAMPK | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| Gastric function | Human gastric cancer cell | 20 | 48 | (−) apoptosis in gastric cancer cells; ↓ cell viability | ↑ p70S6 kinase; ↑ AMPK; ↑ PERK; ↑ ATF4 | Sun X S et al. (2019) |

In vitro effects of chicoric acid in the treatment of various disorders.

↑, increase; ↓, decrease; (+), active; (−), inhibit; N/A, not available; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; Iκ-Bα, inhibitor kappa B alpha; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; IL-1β, interleukin-1 beta; hIAPP, human islet amyloid polypeptide; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; Nrf2, nuclear factor–erythroid 2 related factor 2; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; IL6, interleukin 6; PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α; SIRT1, silent information regulator type 1; pAMPK, phospho-AMP–activated protein kinase; PERK, protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase; ATF4, activating transcription factors 4.

TABLE 5

| Disorders | Species (sex) | Models | Dose (mg/kg/d) | Duration (days) | Effects | Suggested mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain function | C57BL/6 mice (M) | Parkinson's disease (MPTP) | 40, p.o. | 12 | ↑ immunological response | ↑ BDNF; ↑ DA; ↑ 5-HT | Wang et al. (2022) |

| Chicken embryo (N/A) | Neurotoxicity (TH) | 100 µg/60 g (air cell injection) | 19 | ↑ Antioxidant; ↑ anti-inflammatory; ↑ genoprotective; ↑ antiapoptotic; ↓ NO; ↓ MPO | ↓ TNF-α; ↓ IL-1β; ↓ CASP3; ↓ BCL-2; ↓ NF-κB1 | Farag et al. (2021) | |

| Liver function | C57BL/6 mice (M) | Acute liver injury (LPS + d-GalN) | 50, p.o. | 1 | ↓ Hepatic injury; ↓ inflammation | (+) Nrf2 pathway; ↓ MAPKs; ↓ NF-κB; ↓ ALT; ↓ AST; ↑ AMPK | Li et al. (2020) |

| Wistar rats (M) | Liver injury (methotrexate) | 25 and 50, p.o. | 19 | ↓ Hepatic injury; ↓ inflammation; ↓ oxidative stress | (+) Nrf2/HO-1 signaling and PPARγ; ↑ Nrf2; ↑ HO-1; ↑ NQO-1; ↑ PPARγ; ↑ BCL-2; ↓ Bax; ↓ cytochrome c; ↓ caspase-3 | Hussein et al. (2020) | |

| C57BL/6 mice (M) | Nonalcoholic fatty liver (high-fat diet) | 15 or 30, p.o. | 63 | ↓ lipid accumulation; ↓ oxidative stress; ↓ inflammation | ↑ SOD; ↓ ROS; ↑ AMPK; ↑ Nrf2; ↓ NF-κB | Ding et al. (2020) | |

| Aging | Caenorhabditis elegans (N/A) | Lifespan extension (chicoric acid) | 25 and 50, p.o. | 12 | ↑ Oxidative stress resistance; ↓ ROS; ↓ pumping rate; ↓locomotive activity | In part through regulation AAK-2 and SKN-1 | Peng et al. (2019) |

| Kidney function | Wistar rats (M) | Acute kidney injury (methotrexate) | 25 and 50, i.p. | 15 | (−) apoptosis; ↑ antioxidant defenses | ↓ NF-κB; ↓ p65; ↓ NLRP3; ↓ caspase-1; ↓ IL-1β; ↓ caspase-3; ↑ BCL-2 | Abd EI-Twab et al. (2019) |

| Lung function | BALB/c mice (M) | Acute lung injury (lipopolysaccharide) | 20 or 40, i.p. | 12 | ↓ protein leakage; ↓ lung wet/dry ratio; ↑ antioxidant defenses | ↓ MAPK; ↑ SOD; ↑ HO-1; ↑ Nrf2;↓ MPO | Ding et al. (2019) |

In vivo effects of chicoric acid in the treatment of various disorders.

M, male; F, female; ↑, increase; ↓, decrease; (+), active; (−), inhibit; p.o., per os (oral administration); i.p., intraperitoneal injection; N/A, not available; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; MPTP, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine; DA, dopamine; 5-HT, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; TH, thiacloprid; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; NO, nitric oxide; MPO, myeloperoxidase; CASP3, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase; BCL-2, B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; d-GalN, d-galactosamine; MAPKs, mitogen-activated protein kinases; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; PPARγ, proliferator-activated receptor gamma; SOD, serum superoxide dismutase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ROS, reactive oxygen species; AAK-2, a homolog of adenosine monophosphate (AMP)–activated protein kinase; SKN-1, a homolog of nuclear factor–erythroid 2 related factor 2; MPO, inflammatory cell infiltration, myeloperoxidase.

6 Conclusion and Perspectives

Although there are many chemical synthetic methods, the environmentally friendly and economic synthesis method for bulk preparation of chicoric acid with high purity and high yield needs optimization. Chicoric acid is unstable and the solubility of chicoric acid varies greatly in different solvents. Therefore, the stability and solubility of chicoric acid can be improved by a structural modification to preserve the activity of chicoric acid to meet the needs of different dosages. The biosynthesis of chicoric acid in E. purpurea is still at the preliminary research stage, and the mechanism also requires additional study to clarify. The enrichment of chicoric acid in different plants, parts, and stages can be further explained via an in-depth study of its biosynthesis to regulate and improve the content of chicoric acid by modern biotechnology. Even though there are an increasing number of studies reporting bioactivities of chicoric acid, there are still limitations in arriving at a concrete conclusion due to differences in models, doses, and treatment durations used. Thus, research on chicoric acid requires additional study, and in-depth studies on the pharmacodynamic mechanism are needed to guide clinical medication.

L-chicoric acid was isolated from E. purpurea and P. chinensis (Zhang et al., 2008), D-chicoric acid from C. intybus, and meso-chicoric acid from E. arvense (Veit et al., 1991; Veit et al., 1992), but the optical isomers of chicoric acid from different plants have not been systematically summarized and their pharmacological activities of different optical isomers need to be further studied. C. intybus, L. sativa, E. purpurea, and other herbs belong to medicinal and food homologous plants. The amount of chicoric acid in P. laciniata was significantly higher than in E. purpurea. Some marine resources with large biomasses require more study and utilization. New medicinal resources of chicoric acid should be expanded using resource survey, biological relationships, pharmacological activity, and similarity of the growing environment. It is necessary to systematically study the related factors affecting chicoric acid levels, look for dominant species, and formulate a good scientific agriculture practice based on the biosynthesis and accumulation mechanism of chicoric acid. At the same time, a combination of modern technology and new methods such as tissue culture and biotechnology should help optimize the synthesis of chicoric acid.

Statements

Author contributions

Data collection: XL, FJ, LQ, TZ, CW, and GL; design, analysis, and interpretation of the data: CW, TZ, LS, JL, and HL; critical revision of the manuscript: SF and FL. All authors contributed to writing and formatting of the final version.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project for Key New Drug Development of China (No. 2017ZX09301058); National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82004233); and Project of Medical and Health Technology Development Program in Shandong Province (No. 202013030996).

Conflict of interest

Author HL was employed by the company Lunan Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2022.888673/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abd El-Twab S. M. Hussein O. E. Hozayen W. G. Bin-Jumah M. Mahmoud A. M. (2019). Chicoric Acid Prevents Methotrexate-Induced Kidney Injury by Suppressing NF-Κb/nlrp3 Inflammasome Activation and Up-Regulating Nrf2/ARE/HO-1 Signaling. Inflamm. Res.68, 511–523. 10.1007/s00011-019-01241-z

2

Ameer O. Z. Salman I. M. Asmawi M. Z. Ibraheem Z. O. Yam M. F. (2012). Orthosiphon Stamineus: Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicology. J. Med. Food15, 678–690. 10.1089/jmf.2011.1973

3

Becker C. Urlić B. Jukić Špika M. Kläring H. P. Krumbein A. Baldermann S. et al (2015). Nitrogen Limited Red and Green Leaf Lettuce Accumulate Flavonoid Glycosides, Caffeic Acid Derivatives, and Sucrose while Losing Chlorophylls, Β-Carotene and Xanthophylls. PLoS One10, e0142867. 10.1371/journal.pone.0142867

4

Bekinschtein P. Cammarota M. Katche C. Slipczuk L. Rossato J. I. Goldin A. et al (2008). BDNF Is Essential to Promote Persistence of Long-Term Memory Storage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.105, 2711–2716. 10.1073/pnas.071186310510.1073/pnas.0711863105

5

Cao J. Xia X. Chen X. Xiao J. Wang Q. (2013). Characterization of Flavonoids from Dryopteris Erythrosora and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant, Anticancer and Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition Activities. Food Chem. Toxicol.51, 242–250. 10.1016/j.fct.2012.09.039

6

Cao L. Hao Z. H. Sun J. Wang C. Y. (2010). Study on the Optimization of Uitrasoni Wave Extraction Cichoric Acid from Echinacea Purpurea. Chin. J. Veterinary Med.44, 35–37. CNKI: SUN: ZSYY.0.2010-05-017. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2010&filename=ZSYY201005017&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=U8GakrH3eo7DiiaNV3JTqHZuzGNxW_inEnpPpBHp0ePYKkofWX7A2z2ycDd-tI0s.

7

Carazzone C. Mascherpa D. Gazzani G. Papetti A. (2013). Identification of Phenolic Constituents in Red Chicory Salads (Cichorium Intybus) by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detection and Electrospray Ionisation Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Food Chem.138, 1062–1071. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.11.060

8

Chen L. Huang G. Gao M. Shen X. Gong W. Xu Z. et al (2017). Chicoric Acid Suppresses BAFF Expression in B Lymphocytes by Inhibiting NF-Κb Activity. Int. Immunopharmacol.44, 211–215. 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.01.021

9

Chen M. G. N. Wang H. Li Y. S. Fan Q. L. Qin X. (2020). Research Progress on Cultivation Techniques and Application of Medicinal and Edible Dandelion. J. Shanxi Agric. Sci.48, 2007–2011. CNKI: SUN: SXLX.0.2020-12-037. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2020&filename=SXLX202012037&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=sAxHpliTfBVr29GyS7p2Y7ET6rD5rv_hlyp5UrDWMeKx0_FY7NMv71rNLiLufvFk.

10

Chen S. Pan S. Zhao W. Yang Z. Wu H. Yang Y. (2012). Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Characterization of a New Compound, Li3NaBaB6O12. Solid State Sci.14, 1186–1190. CNKI: SUN: ZCYO.0.2012-06-043. 10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2012.05.026https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2012&filename=ZCYO201206043&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=Rhr96zUc9WoK_QLcCWWurdOCoHZiC9TmJjDKvKasaWQ2k6OoOwSuuYO_XgBLGDvy.

11

Cheng Y. X. Liu Y. F. Sun Q. X. Guo S. F. (2018). Study on the Extraction Technology and Anti-inflammatory Activity of the Effective Components in Echinacea Purpurea Flower. J. Pharm. Res.37, 39–141+145. 10.13506/j.cnki.jpr.2018.03.003

12

Crosby D. C. Lei X. Gibbs C. G. McDougall B. R. Robinson W. E. Reinecke M. G. (2010). Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Novel Hybrid Dicaffeoyltartaric/diketo Acid and Tetrazole-Substituted L-Chicoric Acid Analogue Inhibitors of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Integrase. J. Med. Chem.53, 8161–8175. 10.1021/jm1010594

13

De Winter G. (2015). Aging as Disease. Med Health Care Philos18, 237–243. 10.1007/s11019-014-9600-y

14

Degl E. I. Pardossi A. Tattini M. Guidi L. (2008). Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Power in Minimally Processed Salad. J. Food Biochem.32, 642–653. 10.1111/j.1745-4514.2008.00188.x

15

Ding H. Ci X. Cheng H. Yu Q. Li D. (2019). Chicoric Acid Alleviates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Lung Injury in Mice through Anti-inflammatory and Anti-oxidant Activities. Int. Immunopharmacol.66, 169–176. 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.10.042

16

Ding X. Jian T. Li J. Lv H. Tong B. Li J. et al (2020). Chicoric Acid Ameliorates Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease via the AMPK/Nrf2/NFκB Signaling Pathway and Restores Gut Microbiota in High-Fat-Diet-Fed Mice. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev.2020, 1–20. 10.1155/2020/9734560

17

Dong J. P. (2008). Isolation of Chemical Composition in Ixeris Sonchifolia (Bge.) Hance and Assaying Collected at Different Time. [Jilin (JL)]: Jilin Agricultural University. [dissertation].

18

Farag M. R. Khalil S. R. Zaglool A. W. Hendam B. M. Moustafa A. A. Cocco R. et al (2021). Thiacloprid Induced Developmental Neurotoxicity via ROS-Oxidative Injury and Inflammation in Chicken Embryo: The Possible Attenuating Role of Chicoric and Rosmarinic Acids. Biology10, 1100. 10.3390/biology10111100

19

Fu R. Zhang P. Jin G. Wang L. Qi S. Cao Y. et al (2021). Versatility in Acyltransferase Activity Completes Chicoric Acid Biosynthesis in Purple Coneflower. Nat. Commun.12. 10.1038/s41467-021-21853-6

20

Gong Z. N. Zhang W. M. Liu C. H. He B. Tan R. X. (2001). Taraxacum Plant Resources in China. China's Wild Plant Resour.3, 9–14+5. CNKI: SUN: ZYSZ.0.2001-03-003. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2001&filename=ZYSZ200103003&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=Jj1LfyIr3XIY0gklnrP1hhkO3P0sw7j5upxP_Tw53J0OwqRbRuxOXrl2EOT34fBb.

21

Grignon-Dubois M. Rezzonico B. (2013). The Economic Potential of Beach-Cast Seagrass - Cymodocea Nodosa: a Promising Renewable Source of Chicoric Acid. Bot. Mar.56, 303–311. 10.1515/bot-2013-0029

22

Guo Z. Li B. Gu J. Zhu P. Su F. Bai R. (2019a). Simultaneous Quantification and Pharmacokinetic Study of Nine Bioactive Components of Orthosiphon Stamineus Benth. Extract in Rat Plasma by UHPLC-MS/MS. Molecules24, 3057. 10.3390/molecules24173057

23

Guo Z. Liang X. Xie Y. (2019b). Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis on the Chemical Constituents in Orthosiphon Stamineus Benth. Using Ultra High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Analysis164, 135–147. 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.10.023

24

Han L. N. Sun J. Y. Guo Q. M. (2014). Dynamic Determination of Active Ingredients in Introduced Echinacea Purpurea. World Sci. Technol. TCM Mat. Med.16, 1858–1861. CNKI: SUN: SJKX.0.2014-08-033.

25

Han L. N. Sun J. Y. Guo Q. M. Zhou F. Q. (2013). Study on Drying Methods of Introduced Echinacea Purpurea. J. Tradit. Chin. Med.40, 2549–2551. 10.13192/j.issn.1000-1719.2013.12.062

26

Han S. Q. Shi W. F. (2009). Study on the Cultivation Methods of Echinodorus Grandiflorus. J. Lands. Res.1, 1054–1055. 10.13989/j.cnki.0517-6611.2009.03.107

27

Hasegawa M. Taneyama M. (1973). Chicoric Acid from Onychium Japonicum and its Distribution in the Ferns. Bot. Mag. Tokyo86, 315–317. 10.1007/bf02488787

28

Haznedaroglu M. Z. Zeybek U. (2007). HPLC Determination of Chicoric Acid in Leaves ofPosidonia Oceanica. Pharm. Biol.45, 745–748. 10.1080/1388020070158571710.1080/13880200701585717

29

He W. Q. (2012). A Taxonomic Study on Pterocypsela Shih (Lactuceae-Compositae). [Zhengzhou (HA)]: Zhengzhou University. [dissertation].

30

Healy E. F. Sanders J. King P. J. Robinson W. E. (2009). A Docking Study of L-Chicoric Acid with HIV-1 Integrase. J. Mol. Graph. Model.27, 584–589. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2008.09.011

31

Hua C. Li J. L. Zhou F. Zhou Q. C. Zhang B. J. Wang R. L. et al (2011). Process Optimization for Cichoric Acid Extraction from Cichorium Lntybus L. Shoots. Food Sci.32, 126–129. CNKI: SUN: SPKX.0.2011-20-027. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2011&filename=SPKX201120027&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=BYZSl-Ec_IkNMeWiUlunMoviCLluBYN9Mg6uzPawPNDn5iVODCvPNYLXq8cq6Xuu.

32

Hussein O. E. Hozayen W. G. Bin-Jumah M. N. Germoush M. O. Abd El-Twab S. M. Mahmoud A. M. (2020). Chicoric Acid Prevents Methotrexate Hepatotoxicity via Attenuation of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation and Up-Regulation of PPARγ and Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.27, 20725–20735. 10.1007/s11356-020-08557-y

33

Innocenti M. Gallori S. Giaccherini C. Ieri F. Vincieri F. F. Mulinacci N. (2005). Evaluation of the Phenolic Content in the Aerial Parts of Different Varieties of Cichorium Intybus L. J. Agric. Food Chem.53, 6497–6502. 10.1021/jf050541d

34

Iswaldi I. Gómez-Caravaca A. M. Lozano-Sánchez J. Arráez-Román D. Segura-Carretero A. Fernández-Gutiérrez A. (2013). Profiling of Phenolic and Other Polar Compounds in Zucchini (Cucurbita Pepo L.) by Reverse-phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Quadrupole Time-Of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. Food Res. Int.50, 77–84. 10.1016/j.foodres.2012.09.030

35

Jia L. Chen Y. Tian Y. H. Zhang G. (2018). MAPK Pathway Mediates the Anti-oxidative E-ffect of C-hicoric A-cid against C-erebral I-schemia-reperfusion I-njury I-n�vivo. Exp. Ther. Med.15, 1640–1646. 10.3892/etm.2017.5598

36

Ke X. H. (2015). Separation, Purification and Microbial Transformation of Cichoric Acid from Pterocarpus Multilobate. Nanjing (China): Nanjing Normal University.

37

Ke X. H. Chen Y. R. Zhao W. W. Qian Y. Y. Dai K. W. Tang C. K. (2015). Separation and Purification of Cichoric Acid in Pterocypsela Laciniata (Houtt.) Shih Extracts. J. Nanjing Norm. Univ.15, 88–92. CNKI:SUN: NJSE. 0.2015-02-016.

38

Kim M. Yoo G. Randy A. Kim H. S. Nho C. W. (2017). Chicoric Acid Attenuate a Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis by Inhibiting Key Regulators of Lipid Metabolism, Fibrosis, Oxidation, and Inflammation in Mice with Methionine and Choline Deficiency.Mol.Nutr.Food Res. 65. 10.1002/mnfr.201600632

39

King P.J. Ma G. Miao W. Jia Q. McDougall B. R. Reinecke M. G. (1999). Structure‐Activity Relationships: Analogues of the Dicaffeoylquinic and Dicaffeoyltartaric Acids as Potent Inhibitors of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Integrase and Replication.J. Med. Chem. 42, 497–509. 10.1021/jm9804735

40

Kour K. Bani S. (2011b). Augmentation of Immune Response by Chicoric Acid through the Modulation of CD28/CTLA-4 and Th1 Pathway in Chronically Stressed Mice. Neuropharmacology60, 852–860. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.001

41

Kour K. Bani S. (2011a). Chicoric Acid Regulates Behavioral and Biochemical Alterations Induced by Chronic Stress in Experimental Swiss Albino Mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav.99, 342–348. 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.05.008

42

Krishna G. Singh B. K. Kim E.-K. Morya V. K. Ramteke P. W. (2015). Progress in Genetic Engineering of Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.)-A Review. Plant Biotechnol. J.13, 147–162. 10.1111/pbi.12339

43

Kühnl T. Koch U. Heller W. Wellmann E. (1987). Chlorogenic Acid Biosynthesis: Characterization of a Light-Induced Microsomal 5-O-(4-Coumaroyl)-D-Quinate/shikimate 3′-hydroxylase from Carrot (Daucus Carota L.) Cell Suspension Cultures. Archives Biochem. Biophysics258, 226–232. 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90339-0

44

Kulangiappar K. Anbukulandainathan M. Raju T. (2014). Nuclear versus Side-Chain Bromination of 4-Methoxy Toluene by an Electrochemical Method. Synth. Commun.44, 2494–2502. 10.1080/00397911.2014.905599

45

Kwee E. M. Niemeyer E. D. (2011). Variations in Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Properties Among 15 Basil (Ocimum Basilicum L.) Cultivars. Food Chem.128, 1044–1050. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.04.011

46

Lamidey A.-M. Fernon L. Pouységu L. Delattre C. Quideau S. Pardon P. (2002). A Convenient Synthesis of the Echinacea-Derived Immunostimulator and HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitor (−)-(2r,3r)-Chicoric Acid. Hca85, 2328–2334. 10.1002/1522-2675(200208)85:8<2328:aid-hlca2328>3.0.co;2-x

47

Langland J. Jacobs B. Wagner C. E. Ruiz G. Cahill T. M. (2018). Antiviral Activity of Metal Chelates of Caffeic Acid and Similar Compounds towards Herpes Simplex, VSV-Ebola Pseudotyped and Vaccinia Viruses. Antivir. Res.160, 143–150. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.10.021

48

Li J. Nie B. Wu L. Zeng Z. L. (2011). Determination of Cichoric Acid in Introducing Plant of Echinacea Purpurea. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal.31, 1804–1807. 10.16155/j.0254-1793.2011.09.025

49

Li Z. Feng H. Han L. Ding L. Shen B. Tian Y. et al (2020). Chicoric Acid Ameliorate Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Lipopolysaccharide and D ‐galactosamine Induced Acute Liver Injury. J. Cell Mol. Med.24, 3022–3033. 10.1111/jcmm.14935

50

Lin J. Chen R. X. Ceng W. S. (2011). Extraction of Cichoric Acid from Echinacea Purpurea by Supercritical CO2 Fliud. China Food Addit.3, 60–64. CNKI: SUN: ZSTJ.0.2011-03-00.

51

Lin K. (2018). “Investigation of Suitable Lighting Modes for Lactuca sativa L,” in Protected Hydroponic Cultivation ([Fujian (FJ)]: Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University). [dissertation].

52

Lipchock J. M. Hendrickson H. P. Douglas B. B. Bird K. E. Ginther P. S. Rivalta I. et al (2017). Characterization of Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B Inhibition by Chlorogenic Acid and Cichoric Acid. Biochemistry56, 96–106. 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b01025

53

Liu H. X. (2016). Comparative Study on Major or Chemical Constituents and Anti-inflammatory and Hepatoprotective Activities of Ixeris Chinensis (Thunb.) Nakai and Sonchus Brachyotus DC. [Shanxi (SX)]: Shanxi University of Chinese Medicine. [dissertation].

54

Liu Q. Chen Y. Shen C. Xiao Y. Wang Y. Liu Z. et al (2017a). Chicoric Acid Supplementation Prevents Systemic Inflammation‐induced Memory Impairment and Amyloidogenesis via Inhibition of NF‐κB. FASEB J.31, 1494–1507. 10.1096/fj.201601071R

55

Liu Q. Fang J. Chen P. Die Y. Wang J. Liu Z. et al (2019). Chicoric Acid Improves Neuron Survival against Inflammation by Promoting Mitochondrial Function and Energy Metabolism. Food Funct.10, 6157–6169. 10.1039/c9fo01417a

56

Liu Q. Hu Y. Cao Y. Song G. Liu Z. Liu X. (2017b). Chicoric Acid Ameliorates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Oxidative Stress via Promoting the Keap1/Nrf2 Transcriptional Signaling Pathway in BV-2 Microglial Cells and Mouse Brain. J. Agric. Food Chem.65, 338–347. 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b04873

57

Luo Z. Gao G. Ma Z. Liu Q. Gao X. Tang X. et al (2020). Cichoric Acid from Witloof Inhibit Misfolding Aggregation and Fibrillation of hIAPP. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.148, 1272–1279. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.10.100

58

Ma J. Li M. Kalavagunta P. K. Li J. He Q. Zhang Y. et al (2018). Protective Effects of Cichoric Acid on H2O2-Induced Oxidative Injury in Hepatocytes and Larval Zebrafish Models. Biomed. Pharmacother.104, 679–685. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.05.081

59

Ma X. L. Wei H. Y. Feng W. Y. Fei F. (2014). Study on Optimization of Extraction Process of Echinacea by Orthogonal Design. Xinjiang J. TCM.32, 52–54. CNKI: SUN: XJZY.0.2014-03-025. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2014&filename=XJZY201403025&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=szAESMCry96YpidvMkLV9333TC-tz2104KQwnE8WGcQ62mL4XuYOtYzID_mM_Fx6.

60

Ma X. Zhang J. Wu Z. Wang X. (2021). Chicoric Acid Attenuates Hyperglycemia-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction through AMPK-dependent Inhibition of Oxidative/nitrative Stresses. J. Recept. Signal Transduct.41, 1–15. 10.1080/10799893.2020.1817076

61

Ma X. Z. Zeng Y. Wu Y. Li P. Y. (2011). Review on the Chemical Constituents and Pharmcological Activities of Sonchus L. J. Qinghai Norm. Univ.27 (02), 49–52. 10.16229/j.cnki.issn1001-7542.2011.02.009

62

Marques A. M. Provance D. W. Kaplan M. A. C. Figueiredo M. R. (2017). Echinodorus Grandiflorus : Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Pharmacological Overview of a Medicinal Plant Used in Brazil. Food Chem. Toxicol.109, 1032–1047. 10.1016/j.fct.2017.03.026

63

Mascherpa D. Carazzone C. Marrubini G. Gazzani G. Papetti A. (2012). Identification of Phenolic Constituents inCichorium endiviaVar.Crispumand Var.latifoliumSalads by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detection and Electrospray Ioniziation Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem.60, 12142–12150. 10.1021/jf3034754

64

Meng C. G. Fu H. F. Chen X. W. Wang Y. Y. Zhang Y. D. (2015). Study on Extraction and Antioxidant Activity of Cichoric Acid from Cichorium Lntybus L. J. Food Saf. Qual.6, 4460–4467. 10.19812/j.cnki.jfsq11-5956/ts.2015.11.036

65

Meng C. G. (2016). Study on the Technology of Extraction and Separation and Physiological Activity of Cichoric Acid from Cichoriuh Intybus L. [Shanxi (SX)]: Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University.

66

Min X. Yi Z. Xiao-Jing S. Yun-Ling Z. Hai-Peng Z. (2019). The Distribution of Large Floating Seagrass (Zostera Marina) Aggregations in Northern Temperate Zones of Bohai Bay in the Bohai Sea, China. PLoS One14, e0201574. 10.1371/journal.pone.0201574

67

Mohammadi M. Abbasalipourkabir R. Ziamajidi N. (2020). Fish Oil and Chicoric Acid Combination Protects Better against Palmitate-Induced Lipid Accumulation via Regulating AMPK-Mediated SREBP-1/FAS and PPARα/UCP2 Pathways. Archives Physiology Biochem., 1–9. 10.1080/13813455.2020.1789881

68

Nie W. J. Xu S. S. Zhang Y. M. (2020). Advances in the Study of Effective Components and Pharmacological Action of Dandelion. J. Liaoning Univ. TCM.22, 140–145. 10.13194/j.issn.1673-842x.2020.07.034

69

Nobela O. Renslow R. S. Thomas D. G. Colby S. M. Sitha S. Njobeh P. B. et al (2018). Efficient Discrimination of Natural Stereoisomers of Chicoric Acid, an HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitor. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol.189, 258–266. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.10.025

70

Nuissier G. Rezzonico B. Grignon-Dubois M. (2010). Chicoric Acid from Syringodium Filiforme. Food Chem.120, 783–788. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.11.010

71

Oh M.-M. Carey E. E. Rajashekar C. B. (2009). Environmental Stresses Induce Health-Promoting Phytochemicals in Lettuce. Plant Physiology Biochem.47, 578–583. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.02.008

72

Ortiz M. Á. Tremetsberger K. Terrab A. Stuessy T. F. García-castaño J. L. Urtubey E. et al (2008). Phylogeography of the Invasive weed Hypochaeris radicata(Asteraceae): from Moroccan Origin to Worldwide Introduced Populations. Mol. Ecol.17, 3654–3667. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03835.x

73

Peng Y. Sun Q. Gao R. Park Y. (2019). AAK-2 and SKN-1 Are Involved in Chicoric-Acid-Induced Lifespan Extension in caenorhabditis Elegans. J. Agric. Food Chem.67, 9178–9186. 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b00705

74

Petersen M. Abdullah Y. Benner J. Eberle D. Gehlen K. Hücherig S. et al (2009). Evolution of Rosmarinic Acid Biosynthesis. Phytochemistry70, 1663–1679. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.05.010

75

Pilavtepe M. Yucel M. Helvaci S. S. Demircioglu M. Yesil-Celiktas O. (2012). Optimization and Mathematical Modeling of Mass Transfer between Zostera Marina Residues and Supercritical CO2 Modified with Ethanol. J. Supercrit. Fluids68, 87–93. 10.1016/j.supflu.2012.04.013

76

Pozharitskaya O. N. Shikov A. N. Makarova M. N. Kosman V. M. Faustova N. M. Tesakova S. V. et al (2010). Anti-inflammatory Activity of a HPLC-Fingerprinted Aqueous Infusion of Aerial Part of Bidens Tripartita L. Phytomedicine17, 463–468. 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.08.001

77

Sadeghabadi Z. A. Ziamajidi N. Abbasalipourkabir R. Mohseni R. Borzouei S. (2019). Palmitate-induced IL6 Expression Ameliorated by Chicoric Acid through AMPK and SIRT1-Mediated Pathway in the PBMCs of Newly Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes Patients and Healthy Subjects. Cytokine116, 106–114. 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.12.012

78

Scarpati M. L. Oriente G. (1958). Chicoric Acid (Dicaffeyltartic Acid): Its Isolation from Chicory (Chicorium Intybus) and Synthesis. Tetrahedron4, 43–48. 10.1016/0040-4020(58)88005-9

79

Schlernitzauer A. Oiry C. Hamad R. Galas S. Cortade F. Chabi B. et al (2013). Chicoric Acid Is an Antioxidant Molecule that Stimulates AMP Kinase Pathway in L6 Myotubes and Extends Lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One8, e78788. 10.1371/journal.pone.0078788

80

Shah S. A. Sander S. White C. M. Rinaldi M. Coleman C. I. (2007). Evaluation of Echinacea for the Prevention and Treatment of the Common Cold: A Meta-Analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis.7, 473–480. 10.1016/s1473-3099(07)70160-3

81

Stewart G. Cox E. Le Duc M. Pakeman R. Pullin A. Marrs R. (2008). Control of pteridium Aquilinum: Meta-Analysis of a Multi-Site Study in the UK. Ann. Bot.101, 957–970. 10.1093/aob/mcn020

82

Street R. A. Sidana J. Prinsloo G. (2013). Cichorium Intybus: Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicology. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern. Med.2013, 1–13. 10.1155/2013/579319

83

Sun J. Y. (2011). The Preliminary Study on Morphology and Active Components Dynamical Accumulation of Echinacea Purpurea (L.) Moench Cultivated. [Shandong (SD)]: Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. [dissertation].

84

Sun X. S. Zhu L. Z. Zhu L. P. Zhang W. C. Yan S. G. (2019). Optimization of Reflux Extraction Conditions of Chicory Acid in Echinacea Purpurea. J. qilu Univ. Technol.33, 35–40. 10.16442/j.cnki.qlgydxxb.2019.01.006

85

Sun X. Zhang X. Zhai H. Zhang D. Ma S. (2019). Chicoric Acid (CA) Induces Autophagy in Gastric Cancer through Promoting Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Stress Regulated by AMPK. Biomed. Pharmacother.118, 109144–144. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109144

86

Tian S. X. Li H. L. Xu G. Y. Chen B. (2021). A Synthetic Method of Cichoric Acid and Preparation of L-Cichoric Acid Crystal Form. China. Patent No CN109678706B. Beijing: China: State Intellectual Property Office Patent Office.

87

Tsai K.-L. Kao C.-L. Hung C.-H. Cheng Y.-H. Lin H.-C. Chu P.-M. (2017). Chicoric Acid Is a Potent Anti-atherosclerotic Ingredient by Anti-oxidant Action and Anti-inflammation Capacity. Oncotarget8, 29600–29612. 10.18632/oncotarget.16768

88

Veit M. Strack D. Czygan F.-C. Wray V. Witte L. (1991). Di-E-caffeoyl-meso-tartaric Acid in the Barren Sprouts of Equisetum Arvense. Phytochemistry30, 527–529. 10.1016/0031-9422(91)83720-6

89

Veit M. Weidner C. Strack D. Wray V. Witte L. Czygan F.-C. (1992). The Distribution of Caffeic Acid Conjugates in the Equisetaceae and Some Ferns. Phytochemistry31, 3483–3485. 10.1016/0031-9422(92)83711-7

90

Vidal V. Laurent S. Charles F. Sallanon H. (2019). Fine Monitoring of Major Phenolic Compounds in Lettuce and Escarole Leaves during Storage. J. Food Biochem.43, e12726. 10.1111/jfbc.12726

91

Wang H. Liu W. Z. Lu X. L. Chen S. Z. Al T. M. (2002). Determination of Cichoric Acid in Echinacea Purpuea. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi27, 418–420. CNKI: SUN: ZGZY.0.2002-06-004. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2002&filename=ZGZY200206004&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=V2C53YkAq4Qo3-JfQoHPMalPR2zQqpVIisWLwznTDIn-TbEZggQS8QARaKrSt6zS.

92

Wang N. Li R. Feng B. Cheng Y. Guo Y. Qian H. (2022). Chicoric Acid Prevents Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration in a Mouse Parkinson's Disease Model: Immune Response and Transcriptome Profile of the Spleen and Colon. Ijms23, 2031. 10.3390/ijms23042031

93

Wang Y. C. Wang L. Jin H. Li Q. C. Yang X. L. (2015). Study on Extraction Conditions of Ultrasonic Microwave Synergistic Extraction Method of Cichoric Acid. Food Res. Evelopment36, 28–31. CNKI: SUN: SPYK.0.2015-15-011.

94

Wang Y. Diao Z. Li J. Ren B. Zhu D. Liu Q. et al (2017). Chicoric Acid Supplementation Ameliorates Cognitive Impairment Induced by Oxidative Stress via Promotion of Antioxidant Defense System. RSC Adv.7, 36149–36162. 10.1039/c7ra06325c

95

Wang Y.R Y. R. Li Y. M. Yang N. Zhou B. S. Chen F. Liu J. P. et al (2017). Research Progress on Chemical Compositions and Pharmacological Actions of Taraxacum. Special Wild Econ. Animal Plant Res39, 67–75. 10.16720/j.cnki.tcyj.2017.04.015

96

Wang Y. Y. Sun Y. B. Wang H. S. Yang H. He Z. M. Li Z. J. (2016). Determination of Chicoric Acid from Different Medicinal Part of E. Purpurea Moench by HPLC. Ginseng Res.28, 23–25. 10.19403/j.cnki.1671-1521.2016.02.007

97

Wei T. van Treuren R. Liu X. Zhang Z. Chen J. Liu Y. et al (2021). Whole-genome Resequencing of 445 Lactuca Accessions Reveals the Domestication History of Cultivated Lettuce. Nat. Genet.53, 752–760. 10.1038/s41588-021-00831-01

98

Wills R. B. H. Stuart D. L. (1999). Alkylamide and Cichoric Acid Levels in Echinacea Purpurea Grown in Australia. Food Chem.67, 385–388. 10.1016/S0308-8146(99)00129-6

99

Xia Y. (2019). Discussion on the Distribution Law of Horsetail Economic Plants in Heilongjiang Province. J. For. Surv. Des.3, 81–82. CNKI: SUN: LYKC.0.2019-03-034. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2019&filename=LYKC201903034&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=fpzZ6Ov6TRzaaGhjrI4GNGRJHkXYkvSDdxjZwqWN2HtpzpiXxn_QSe3xuPd_LoUU.

100

Xin J. Han L. N. Zhou F. Q. (2012). Optimization of Extraction Technology of Cichoric Acid from Echinacea Purpurea by Orthogonal Test. J. Shandong Univ. TCM36, 539–541. 10.16294/j.cnki.1007-659x.2012.06.032

101

Xu D. Tang Y. W. Zhu W. (2006). Determ Ination of 2 Caffeic Acid Derivatives in Echinacea Extracts by RP-HPLC. Chin. Tradit. Pat. Med.28, 1493–1497. CNKI: SUN: ZCYA.0.2006-10-030. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2006&filename=ZCYA200610030&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=znJyWvpZrrrr-qckmtgxztC_9qJIfGohFGRp6le3ytMaydtiIDYmpDHkc7bD5RCt.

102

Xu J. M. (2008). Study on Extracting Cichoric Acid from Cichory and Fingerprint. [Beijing (BJ)]: Beijing University of Chemical Technology. [dissertation].

103

Yang L. Wang X. H. Cheng H. Y. Chen J. W. Zhan Z. L. Bai J. Q. (2021). Textual Research on the Materia Medica of Hai Jin Sha. J. Shaanxi Univ. Chin. Med.44, 55–62. 10.1038/s41440-020-00605-x

104

Ye X. Y. Li G. Y. Ma D. D. Xie W. Y. Wang Y. P. (2007). A Newly Escaped Plant Species in Zhejiang Province:Hypochaeris Radicata. J. Zhejiang For. Coll.5, 647–648. CNKI: SUN: ZJLX.0.2007-05-028. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2007&filename=ZJLX200705028&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=NUvY6BnY4B2Jhu_4US60MdjqLeh7dCBGMF298bHaUyWC-mahzS98_pv6I34s9XB2.

105

Zhang L. (2018). Studies on the Lettuce Genomic Evolution and Genetic Cloning of a Major Generesponsible for Leaf Color Variation in Lettuce. [WuHan (HB)]: Hua Zhong Agricultural University. [dissertation].

106

Zhang L. Zou R. X. Deng Y. Zhang Q. Y. Bi X. L. (2008). Study on Extraction Technology of Effective Parts of Echinacea Purpurea. Chin. Pat. Med.4, 603–605.

107

Zhang T. Li J. Shi L. Feng S. Li F. (2021). Anti-RSV Activities of Chicoric Acid from Echinacea Purpurea In Vitro. Minerva. Surg.77. 10.23736/S2724-5691.21.08925-5

108

Zhang X. Q. Shi B. J. Li Y. L. Hiroshi K. Ye W. C. (2008). Chemical Constituents in Aerial Parts of Pulsatilla Chinensis. Chin. Traditional Herb. Drugs39, 651–653. CNKI: SUN: ZCYO.0.2008-05-005. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2008&filename=ZCYO200805005&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=3PosB37mGFB_h-yoaGna7kVepPcjinlLHGKeXxzGfc1uaJ6-VjBNLPRfC1sfOuLr.

109

Zhao C. Y. Jiang M. Y. (2016). The Chemical Constituents and Antioxidant Activity of Ixeris Sonchifolia. J. Pharm. Pract.34, 24–27+51. CNKI: SUN: YXSJ.0.2016-01-008. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2016&filename=YXSJ201601008&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=HDTjppNTJcz5TFALG6JzYyu5clF9KpH_nDPtPsYURq-6D-l8NSlW1fV7_V75wJY4.

110

Zhao J. Deng J. W. Chen Y. W. Li S. P. (2013). Advanced Phytochemical Analysis of Herbal Tea in China. J. Chromatogr. A1313, 2–23. 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.07.039

111

Zhao Y. M. Yang L. (2018). Study on the Spray Extraction Process of Cichoric Acid from Echinacea Purpurea. J. Shaanxi Agric. Sci.64, 32–35. CNKI: SUN: SNKX.0.2018-10-010.

112

Zhong Y. J. Li L. Xu F. L. (2010). Studies on Extraction Process of Cichoric Acid in Echinacea Purpurea. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Formulae16, 1–4. 10.13422/j.cnki.syfjx.2010.04.011

113

Zhou S. Meng H. K. (2017). Factors Affecting Changes in Planting Areas of Main Peanut Producing Areas in China. Jiangsu Agric. Sci.45, 250–253. 10.15889/j.issn.1002-1302.2017.13.065

114

Zhou X. J. (2014). Comprehensive Evaluation on the Quality of Aerial Parts of Chicory. [Beijing (BJ)]: Beijing University of Chinese Medicine. [dissertation].

115

Zidorn C. Schubert B. Stuppner H. (2005). Altitudinal Differences in the Contents of Phenolics in Flowering Heads of Three Members of the Tribe Lactuceae (Asteraceae) Occurring as Introduced Species in New Zealand. Biochem. Syst. Ecol.33, 855–872. 10.1016/j.bse.2004.12.027

Summary

Keywords

chicoric acid, biosynthesis, chemical synthesis, natural occurrence, content detection, bioactive effects

Citation

Yang M, Wu C, Zhang T, Shi L, Li J, Liang H, Lv X, Jing F, Qin L, Zhao T, Wang C, Liu G, Feng S and Li F (2022) Chicoric Acid: Natural Occurrence, Chemical Synthesis, Biosynthesis, and Their Bioactive Effects. Front. Chem. 10:888673. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2022.888673

Received

04 March 2022

Accepted

09 May 2022

Published

23 June 2022

Volume

10 - 2022

Edited by

Kamaldeep Paul, Thapar Institute of Engineering & Technology, India

Reviewed by

Viduranga Y. Waisundara, Australian College of Business and Technology, Sri Lanka

Amit Jaisi, Walailak University, Thailand

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Yang, Wu, Zhang, Shi, Li, Liang, Lv, Jing, Qin, Zhao, Wang, Liu, Feng and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuai Feng, fengshuaihappy@163.com; Feng Li, 13969141796@163.com

†ORCID: Min Yang, orcid.org/0000-0002-0264-5123

This article was submitted to Organic Chemistry, a section of the journal Frontiers in Chemistry

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.