Abstract

The continuing rapid expansion of 99mTc diagnostic agents always calls for scaling up 99mTc production to cover increasing clinical demand. Nevertheless, 99mTc availability depends mainly on the fission-produced 99Mo supply. This supply is seriously influenced during renewed emergency periods, such as the past 99Mo production crisis or the current COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, these interruptions have promoted the need for 99mTc production through alternative strategies capable of providing clinical-grade 99mTc with high purity. In the light of this context, this review illustrates diverse production routes that either have commercially been used or new strategies that offer potential solutions to promote a rapid production growth of 99mTc. These techniques have been selected, highlighted, and evaluated to imply their impact on developing 99mTc production. Furthermore, their advantages and limitations, current situation, and long-term perspective were also discussed. It appears that, on the one hand, careful attention needs to be devoted to enhancing the 99Mo economy. It can be achieved by utilizing 98Mo neutron activation in commercial nuclear power reactors and using accelerator-based 99Mo production, especially the photonuclear transmutation strategy. On the other hand, more research efforts should be devoted to widening the utility of 99Mo/99mTc generators, which incorporate nanomaterial-based sorbents and promote their development, validation, and full automization in the near future. These strategies are expected to play a vital role in providing sufficient clinical-grade 99mTc, resulting in a reasonable cost per patient dose.

1 Introduction

Short-lived radionuclides continue to prove their crucial role in the development of nuclear medicine utilization in both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Effective therapy involves the delivery of a specific radiation dose to the tumor tissues either by the use of an external radiation source or internal radiotherapy techniques. For the former, hard gamma-ray emitters are favorably used, while a great need for the radionuclides with a low range of highly ionizing radiation emissions, such as alpha, beta and/or Auger electrons, are required to achieve internal therapy successfully (IAEA, 2009; Qaim, 2019). Definitely, a profitable therapy protocol strongly depends on the delivery of accurate information about the cancer lesion, such as the shape, size, and blood flow to the affected organ. To achieve this step, high-quality tumor imaging must be performed with the help of in-vivo diagnostic investigation tools. This method can be divided into two main categories, Positron Emission Tomography (PET), which includes the use of several positron emitters, and Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT), in which radionuclides emitting low energetic gamma radiation are of great interest (Pimlott and Sutherland, 2011).

Particularly, SPECT radionuclides should have one or at least one main gamma energy line in the range of 100–200 keV. Table 1 displays the most commonly used radionuclides in SPECT imaging processes (Pimlott and Sutherland, 2011; Tàrkànyi et al., 2019).

TABLE 1

| Radionuclide | Half-life | Mode of decay | Main photon energy, keV | Branching ratio (intensity), % | Availability | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99mTc | 6.01 h | IT (99.996%) | 140.51 | 89 | 99Mo → 99mTc (99Mo/99mTc generator) | |

| 100Mo(p,2n)99mTc | ||||||

| 100Mo(d,3n)99mTc | ||||||

| 123I | 13.27 h | EC, β+ (100%) | 158.97 | 83 | 122Te(d,n)123I | • High cost |

| 123Te(p,n)123I | • Low availability | |||||

| 111In | 2.80 d | EC (100%) | 171.28 | 90 | 112Cd(p,2n)111In | • Relatively long half-life |

| 245.39 | 94 | 111Cd(p,n)111In | ||||

| 201Tl | 3.04 d | EC (100%) | 167.43 | 10 | 203Tl(p,3n)201Pb → 201Tl | • Relatively long half-life |

| 67Ga | 3.26 d | EC (100%) | 93.31 | 39.2 | 68Zn(p,2n)67Ga | • Relatively long half-life |

| 184.57 | 21.2 | 67Zn(p,n)67Ga | ||||

| 300.21 | 16.8 |

The predominantly used radionuclides in SPECT processes and their nuclear characteristics.

To describe the pivotal role of 99mTc, S. Esarey called it a vitally crucial diagnostic isotope used nearly once a second worldwide (IAEA, 2011). Undoubtedly, 99mTc is the most extensively used diagnostic radionuclide in the SPECT family. It is currently involved in 80–85% of all in-vivo nuclear medicine diagnostic examinations (Boschi et al., 2017; Gumiela, 2018; Martini et al., 2018; Osso et al., 2012; Owen et al., 2014; Sakr et al., 2017). Annually, 30–40 million SPECT imaging studies have been conducted worldwide using 99mTc solely (half of which in the United States). 99mTc utilization is estimated to increase by 3–8% every year (Banerjee et al., 2000; Eckelman, 2009; Guerin et al., 2010; IAEA, 2013a; Chakravarty et al., 2013; Owen et al., 2014; Dilworth and Pascu, 2015; Gumiela, 2018; Haroon and Nichita, 2021). 99mTc decays by a relatively short half-life (T1/2 = 6.01 h) and emits only one-gamma photon at low energy of 140.51 keV. This energy is ideally suited to penetrate the tissues and can be efficiently detected through SPECT cameras from outside the body, resulting in a high-quality image of the target organs with minimum radiation exposure dose to the patient. In addition, 99mTc has unique coordination chemistry, which allows conjugation with a broad spectrum of diverse pharmaceutical molecules (IAEA, 2009; Dilworth and Pascu, 2015; Boschi et al., 2017; Gumiela, 2018). These 99mTc-labelled compounds have been involved in the visualization of most organs (Vallabhajosula et al., 1989; Zolle, 2007; Leggett and Giussani, 2015; Araz et al., 2020; Urbano et al., 2020; Parihar et al., 2021). Moreover, the global on-demand availability of 99mTc through the user-friendly 99Mo/99mTc generators with reasonable cost-effectiveness has greatly encouraged nuclear medicine departments to conduct many research studies to explore its pivotal role in diagnostic imaging in detail (Mikaeili et al., 2018; Gan et al., 2020; Ávila-Sánchez et al., 2020). Table 2 highlights the wide-scale applicability of 99mTc-based radiopharmaceuticals and provides the injection activity and the estimated exposure dose for each diagnostic procedure. Furthermore, based on its accessible availability and favorable nuclear properties, 99mTc received considerable attention in multi-disciplinary fields. Recently, it has been involved in a variety of industrial radiotracer applications (Fauquex et al., 1983; Kantzas et al., 2000; Bandeira et al., 2002; Borroto et al., 2003; Berne and Thereska, 2004; Hughes et al., 2004; Thyn and Zitny, 2004; Dash et al., 2012; Pavlovicl et al., 2020).

TABLE 2

| Organ | 99mTc radiopharmaceuticals | Recommended adult injected activity, MBqa | Radiation dose estimationb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNMMI | ENAM | Injected activity, MBq | Effective dose, mSv | ||

| Brain | 99mTc-ECD | 555–1110 | 555–725 | 700 | 5.4 |

| 99mTc-HMPAO | 555–1110 | 555–725 | 700 | 6.5 | |

| 99mTc-MAA | 40.7–151.7 | 60–78 | 78 | 0.9 | |

| Bone and bone marrow | 99mTc-MDP | 740–1110 | 375–490 | 740 | 4.2 |

| 99mTc-HMPAO (WBC) | 185–370 | 375–490 | 370 | 4.1 | |

| Heart | 99mTc-Pyrophosphate | 370–555 | N.A | 370 | 2.1 |

| 99mTc-Tetrofosmin/sestaMIBI (exercise) | 740–1480 | 900–1176 (One-day protocol) | 740 | 5.2 | |

| 450–588 (2-day protocol min) | |||||

| 675–882 (2-day protocol max) | |||||

| 99mTc-Tetrofosmin / sestaMIBI (resting) | 740–1480 | 300–392 (One-day protocol) | 740 | 5.6 | |

| 450–588 (2-day protocol min) | |||||

| 675–882 (2-day protocol max) | |||||

| 99mTc-RBC | 555–1110 | 600–784 (Blood pool) | 555 | 3.9 | |

| 99mTc-DMSA | 74–222 | 73–95 | 90 | 0.8 | |

| 99mTc-DTPA (IV) | 37–1110 | 166–196 (normal renal function) | 190 | 0.9 | |

| 150–196 (abnormal renal function) | |||||

| 99mTc-MAG3 | 37–370 | 58–69 | 58 | 0.4 | |

| Liver | 99mTc-Sulfur/albumin colloid (IV) | 148–222 | N.A | 185 | 2.6 |

| 99mTc-Sulfur/albumin colloid (oral) | 18–74 | N.A | 46 | 1.0 | |

| 99mTc-IDA | N.A | 112–147 | N.A | N.A | |

| Lung | 99mTc-DTPA (Inhalation) | 19.98–40.70 | N.A | 30 | 0.2 |

| 99mTc-Technegas | 18.5–37 | 525–686 | 37 | 0.6 | |

| Spleen | 99mTc-RBCs | 555–1110 | 30–39 (Denatured RBC) | 555 | 3.9 |

| Stomach | 99mTc-Pertechnetate | N.A | 112–147 | 112 | 1.5 |

| Thyroid | 99mTc-Pertechnetate | 74–370 | 60–78 | 78 | 1.0 |

| Parathyroid | 99mTc-MIBI | 740–1480 | N.A | N.A | N.A |

| Cancer cells identification | 99mTc-SestaMIBI | N.A | 675–882 | N.A | N.A |

The most commonly used 99mTc-based radiopharmaceuticals with their recommended injection activity and the estimated exposure dose.

(ENAM), European Association of Nuclear Medicine; (SNMMI), the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging.

The activity doses were calculated for body weights from 50 to 68 Kg.

The exposure doses are based on (ICRP, 2015).

The activity doses were taken from https://www.eanm.org/publications/dosage-calculator/ and http://www.snmmi.org/ClinicalPractice/doseTool.aspx (accessed 8.6.2022).

Despite the central role of 99mTc for different diagnostic medical investigations as well as recent industrial implementations, its limited availability at the usage sites is a real difficulty. The primary objective of this review paper is to provide a detailed and comprehensive evaluation of the different production routes of 99mTc that have commercially been exploited. In addition, new production strategies that could potentially promote efficient utilization of 99mTc in the near future are highlighted. In the following sections, the paper discusses the different production routes of the parent 99Mo either by nuclear reactors or particle accelerators, the direct production technology of 99mTc at a cyclotron, and the different 99Mo/99mTc generator systems and their role in supplying 99mTc. Furthermore, the paper underlines the advantages, outcomes, and technical challenges of the different 99mTc production approaches along with their current situation and the possible future perspectives.

2 Production and supply of 99Mo

The increasing interest in 99mTc-labelled radiopharmaceuticals for diagnostic purposes has heightened the need for securing a sufficient supply of 99Mo. Practically, almost all of the used clinical-grade 99mTc in nuclear medicine is derived from 99Mo/ 99mTc generators. In this system, 99Mo (T1/2 = 65.94 h) yields 99mTc by beta β− decay, as shown in Figure 1 (Boyd, 1982a; Hidalgo et al., 1967; IAEA, 2017, 2013a; NEA, 2017, 2010). 99Mo is produced with the use of one of two main facilities; nuclear reactors or particle accelerators. Figure 2 displays the potential production routes of 99Mo and 99mTc.

FIGURE 1

The decay scheme of 99Mo and 99mTc (Hidalgo et al., 1967).

FIGURE 2

The potential production routes of 99Mo and 99mTc. Abbreviations: HEU: Highly Enriched Uranium; LEU: Low Enriched Uranium.

2.1 Reactor-based 99Mo production

The medical isotope 99Mo can be produced in nuclear reactors through two primary routes (IAEA, 1999):

2.1.1 Fission-produced 99Mo

Undoubtedly, the neutron-induced uranium fission technique is widely considered the “gold standard” for the large-scale

99Mo supply for medical applications. Actually, over 95% of all

99Mo used for the production of medical-grade

99mTc is available from the fission of uranium targets in nuclear reactors. These targets can be categorized according to the content of the fissile

235U radioisotope (

IAEA, 1999,

2002,

2005;

NAP, 2016):

1. Natural uranium: 235U content is about 0.72%.

2. Low Enriched Uranium (LEU): 0.72% < 235U content <20%.

3. Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU): 20% ≤ 235U content ≤90%.

4. Weapons-grade Enriched Uranium: 235U content ≥90%.

Generally, a neutron-induced fission reaction occurs when a target of a heavy fissionable element, such as 235U, is introduced into the reactor core. Hence, the 235U nucleus absorbs a thermal neutron and undergoes a fission reaction, resulting in two fission fragments. These comprise about 200 different radionuclides, including 99Mo, according to the reaction . The resulting 99Mo is called a Non-Carrier Added (NCA) product and possesses high specific activity defined as the 99Mo radioactivity per unit molybdenum mass. The fission yield for this reaction is about 6.132% (Haroon and Nichita, 2021; Grummitt and Wilkinson, 1946; Hyde, 1964; IAEA, 2013a, 2008, 2003). Other molybdenum isotopes, namely 97Mo, 98Mo, and 100Mo, are also produced with a total fission yield of 18.1%. These stable isotopes may dilute the 99Mo final activity. However, the specific activity of fission 99Mo is 1000 folds higher than the specific activity of 99Mo produced from neutron-activated 98Mo, as detailed in Section 2.1.2 below (Sameh and Ache, 1989). Table 3 shows a comparison between the production routes of 99Mo in a nuclear reactor.

TABLE 3

| Criteria | Uranium fission | Neutron activation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Material | LEU | U-Al alloy | Natural 98Mo | MoO3 | |

| U-metallic foil | Mo metal | |||||

| HEU | U-Al alloy | Enriched 98Mo | MoO3 | |||

| Mo metal | ||||||

| Availability | Restricted to few producers | Broadly available | ||||

| Production process | Nuclear reaction | 235U (n,f)99Mo | 98Mo (n,γ)99Mo | |||

| Cross-section, barn | 586 (× 6% fission yield) | Thermal flux | 0.13 | |||

| Epithermal flux | 6.7±0.3 | |||||

| Yield | >10,000 Ci 99Mo/g Mo | Natural 98Mo target | ∼0.2–1 Ci 99Mo/g Mo | Influenced by the neutron flux capacity | ||

| Enriched 98Mo target | ≥4 Ci 99Mo/g Mo | |||||

| Specific activity | High specific activity product | Low specific activity product | ||||

| Production facility | Limited to a small number of irradiation sites | More than 50 reactors with high neutron flux (>1014 n/cm2s) are geographically well-distributed | ||||

| Co-production isotopes | 200 different radioisotopes such as 131I and 133Xe | 99Mo solely | ||||

| Chemical Processing | Separation step | Mandatory | Can be avoided | |||

| Feasibility | Complicated and involves hazardous materials | Simple and does not include any hazardous substances | ||||

| Laboratories | Limited | Globally available | ||||

| Concerns | Proliferation risks | High | Negligible | |||

| Cost | High | Low | ||||

| Waste | 50 Ci waste per production of only 1 Ci 99Mo | Negligible | ||||

| Maturity | Status | Well-established technology | Growing technology | |||

| Capability | Covers >95% of the global demand | Used on small-scale production in some countries | ||||

| Licensing and approval | Nuclear regulatory | Approved | Approved | |||

The evaluation of reactor-based 99Mo production technologies.

2.1.1.1 Global supply chain of fission-produced 99Mo

The availability of a sufficient 99Mo supply involves a sequence of connected steps with high complexity. These steps can be defined as the 99Mo supply chain. In the first step, uranium targets are fabricated and tested. Then, these targets are shipped to the irradiation facilities where the production of 99Mo takes place. After that, the irradiated targets are transported to well-equipped processing facilities comprising hot cells, where the separation and purification of 99Mo from other fission products are accomplished. Afterward, the purified carrier-free 99Mo solutions are eventually used for the 99Mo/99mTc generator assembly process. Subsequently, these generators are globally distributed to provide 99mTc of high quality, ready to use for different medical needs (NAP, 2018, 2016).

Based on the fact that 99Mo decays with a relatively short half-life (T1/2 = 65.94 h), all previous steps need to be achieved as rapidly as possible to minimize radioactive decay losses. The quantity of 99Mo produced is defined with the term “six-day Curie”. This term represents how much 99Mo radioactivity remains 6 days after the end of processing. Figure 3 highlights the six-day Curie concept through the 99Mo supply chain (Paterson et al., 2015). The “six-day Curie” concept has been introduced by the manufacturers as a base for calibrating the sales price. However, it is not very suitable to express the losses of 99Mo from the end of bombardment to arrival at the end user since neither transport to the processing facility, processing time, chemical yield, and transport times to the end user are accounted for.

FIGURE 3

The schematic demonstration of the fission-produced 99Mo supply chain, including target irradiation, the production of 99Mo, and the 6-day Curie expression. The produced 99Mo activity from the supply chain is approximately 22% of the total irradiated activity in case of 100% recovery of 99Mo from the irradiated targets. In the same manner, if the processing efficiency is 90%, the expected remaining activity is about 17% of the total produced activity.

Close to 10,000 uranium targets (among them 8,000 targets involving HEU) are consumed annually to afford a 99Mo supply for nuclear medicine utilization. There are, at present, only four agencies that can manufacture and supply targets to the irradiation facilities. These laboratories are operated under the authority of the Atomic Energy Commission of Argentina (CNEA), Argentina; Canadian Nuclear Laboratories (CNL), Canada; Company for the Study and Production of Atomic Fuels (CERCA), France; and Nuclear Technology Products Radioisotopes (NTP), South Africa (NAP, 2018, 2016).

The neutron bombardment of the targets can be carried out in research reactors of high neutron flux, which is usually in the range of ≥ 1014 n/cm2s. Table 4 illustrates the potential irradiation reactors and their production volume (Zhuikov, 2014; NAP, 2018; NEA, 2019). The 99Mo production capability of these reactors covers more than 95% of the global medical need for 99Mo. The target irradiation process typically lasts five to 7 days until the 99Mo growth reaches 80% of the saturation yield. At this point, the overall 99Mo activity remains unchanged. That is because the quantity of 99Mo produced by the target irradiation equals the loss of 99Mo activity due to the radioactive decay (Paterson et al., 2015; NEA, 2017).

TABLE 4

| Irradiation facilitya | Country | Irradiated target | Neutron flux, n/cm2S | Year commissioned | Estimated available capacity, six-day Ci/week | Production of 99Mo, Week/year | Estimated available production capacity by 2024b, six-day Ci/year | Estimated global market share, % | Expected shutdown, year | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global producers | BR-2 | Belgium | HEU/LEU | 1.0E15 | 1961 | 6,500 | 21 | 136,500 | 17 | 2026 | |

| HFR | Netherlands | HEU/LEU | 2.7E14 | 1961 | 6,200 | 39 | 241,800 | 29 | 2026 | ||

| LVR-15 | Czech Republic | HEU/LEU | 1.5E14 | 1957 | 3,000 | 30 | 90,000 | 11 | 2028 | ||

| Maria | Poland | HEU | 3.5E14 | 1974 | 2,200 | 36 | 79,200 | 9 | 2040 | ||

| OPAL | Australia | LEU | 3.0E14 | 2006 | 2,150 | 43 | 92,450 | 11 | 2057 | ||

| +1,350c | +58,050c | 7 | |||||||||

| Safari-1 | South Africa | LEU | 2.4E14 | 1965 | 3,000 | 44 | 130,700 | 16 | 2030 | ||

| NRU | Canada | HEU | 4.0E14 | 1957 | 40% (Global market) | N.A | N.A | N.A | 2018 Retired | ||

| Osiris | France | HEU | 1.7E14 | 1966 | 8% (Global market) | N.A | N.A | N.A | 2015 Retired | ||

| Regional producers | RIAR | RBT-6 | Russia | HEU | 1.4E14 | 1975 | 540 | 50 | 27,000 | Domestic use | 2025 |

| RBT-10 | HEU | 1.5E14 | 1983 | 2025 | |||||||

| KAPROV | WWR-c | HEU | 2.5E13 | 1959 | 350 | 48 | 16,800 | Domestic use | 2025 | ||

| RA-3 | Argentina | HEU | 4.8E13 | 1961 | 500 | 46 | 23,000 | Domestic use | 2027 | ||

The producers of fission 99Mo and their global production volume.

The information is derived from:

The IAEA’s Research Reactor Database (RRDB): https://nucleus.iaea.org/rrdb/#/home (accessed 8.6.2022), NEA, 2019, Zhuikov, 2014, and NAP, 2018.

BR-2, Belgian Reactor 2; HFR, high flux reactor; OPAL, open pool australian light water; NRU, national research universal; SAFARI-1, South African Fundamental Atomic Research Installation 1; RIAR, the Research Institute of Atomic Reactors; and N.A, Not Available.

Available production capacity: is the upper limit of 99Mo production capability that can be achieved on a routine operating schedule.

Additional 99Mo production capability owing to the engagement of a new processing facility, namely, the ANSTO, Nuclear Medicine (ANM) project, which started in May 2019.

After the irradiation step, the targets are left to cool down, allowing short-lived and ultra-short-lived fission products to decay. Then, the irradiated targets are moved to the processing facilities where the recovery of 99Mo from other fission products is conducted, and a pure 99Mo-molybdate solution is prepared. Currently, there exist only five large-scale processing centers that can perform this task. Table 5 shows the five main processing facilities and their global 99Mo supply (IAEA, 2013a, 2015; NAP, 2016,; NEA, 2019).

TABLE 5

| Processing facilitya | Country | Target | Chemical processb | Estimated available supply capacity, six-day Ci/week | Production of 99Mo, week/year | Estimated available supply capacity by 2024c, six-day Ci/year | Estimated global market share, % | Expected shutdown, year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global producers | ANSTO | Australia | LEU | Alkaline | 2,150 | 43 | 92,450 | 13 | 2057 |

| dANM project | +1,350 C | +58,050 C | 8 | ||||||

| eCurium | Netherlands | LEU | Alkaline | 5,000 | 52 | 260,000 | 37 | N.A | |

| IRE | Belgium | HEU | Alkaline process | 3,500 | 49 | 171,500 | 24 | 2028 | |

| NTP | South Africa | LEU | Alkaline | 3,000 | 44 | 130,700 | 18 | 2030 | |

| fCNL/Nordion | Canada | HEU | Acidic | 29% (Global market) | N.A | N.A | N.A | stopped | |

| Mallinckrodt | Netherlands | HEU | Alkaline | 24% (Global market) | N.A | N.A | N.A | stopped | |

| Regional producers | RIAR | Russia | HEU | Alkaline | 540 | 50 | 27,000 | Domestic use | 2025 |

| KAPROV | HEU | Alkaline | 350 | 48 | 16,800 | Domestic use | 2025 | ||

| CNEA | Argentina | LEU | Alkaline | 500 | 46 | 23,000 | Domestic use | 2027 | |

The main uranium fission processing facilities and their 99Mo supply capacities.

ANSTO: australian nuclear science and technology organization; ANM: ANSTO, nuclear medicine; IRE: national institute for radioelements; NTP: nuclear technology products radioisotopes; RIAR: the Research Institute of Atomic Reactors; and N.A: Not Available.

The alkaline process is fully compatible with the U-Al alloy targets and offers the advantage of 131I co-production capability.

Available supply capacity: is the upper limit of 99Mo supply capability that can be achieved on a routine operation framework.

Additional 99Mo supply capability owing to the engagement of a new processing facility, namely, ANSTO, Nuclear Medicine (ANM), which started in May 2019.

Curium was established through a merger between Mallinckrodt Nuclear Medicine and Ion Beam Applications Molecular (IBAM). http://www.mallinckrodt.com/about/news-and-media/2197068 (accessed 8.6.2022).

CNL/Nordion terminated their 99Mo processing activities at the end of 2016.

The uranium fission method deserves careful attention owing to its capability to provide adequate amounts of 99Mo in a carrier-free form with high specific activity, which can satisfy the global medical need. However, the application of this technology faces inherent critical challenges. For instance, proliferation concerns are dramatically growing owing to the use of massive amounts of HEU targets. Nearly 80% of the global demand of 99Mo is produced using uranium targets containing up to 93% of enriched 235U. During the production steps, about 50 kg of weapons-grade HEU are usually handled, and only a very minute amount (∼3%) is utilized in the entire process (NAP, 2009; NEA, 2010; IAEA, 2015). In order to eliminate these nuclear proliferation issues, HEU targets have to be fully substituted by LEU or natural uranium targets (Wu et al., 1995; Cols et al., 2000; Conner et al., 2000). In addition, the aging fleet of the currently used irradiation facilities is also of concern. Approximately 95% of the global supply of 99Mo depends on only six reactors. With the exclusion of OPAL, all the other five reactors have been in service for more than 50 years. Lately, a number of unplanned shutdowns have taken place, and consequently, the international medical community has severely suffered from a 99Mo shortage (Gumiela, 2018). In case of any unexpected future interruption, a renewed 99Mo supply crisis cannot be ruled out and could seriously affect many countries due to the expected rise in the cost of dose per patient (NEA, 2011).

Moreover, the separation and purification of 99Mo from fission products is a sophisticated process and calls for large and complex infrastructures, professional technical skills, and well-equipped laboratories. Only few centers worldwide are well-prepared to conduct this task (Ali and Ache, 1987; NAP, 2016, 2018; NEA, 2019). Furthermore, the generation of massive quantities of toxic radioactive waste containing medium and long-lived radionuclides has to be considered. A significant number of Curies (∼50 Ci) of fission radioactive waste are generated per production of one Curie (Ci) of 99Mo (Boyd, 1987; IAEA, 1998; Tur, 2000). The difficulties mentioned above are clearly reflected in the continuing need for long-term capital investments and routine operating expenditures. As a result, the production cost of 1 Ci of 99Mo from the fission route is four times higher than that of 1 Ci of neutron-capture-produced 99Mo (Boyd, 1982a).

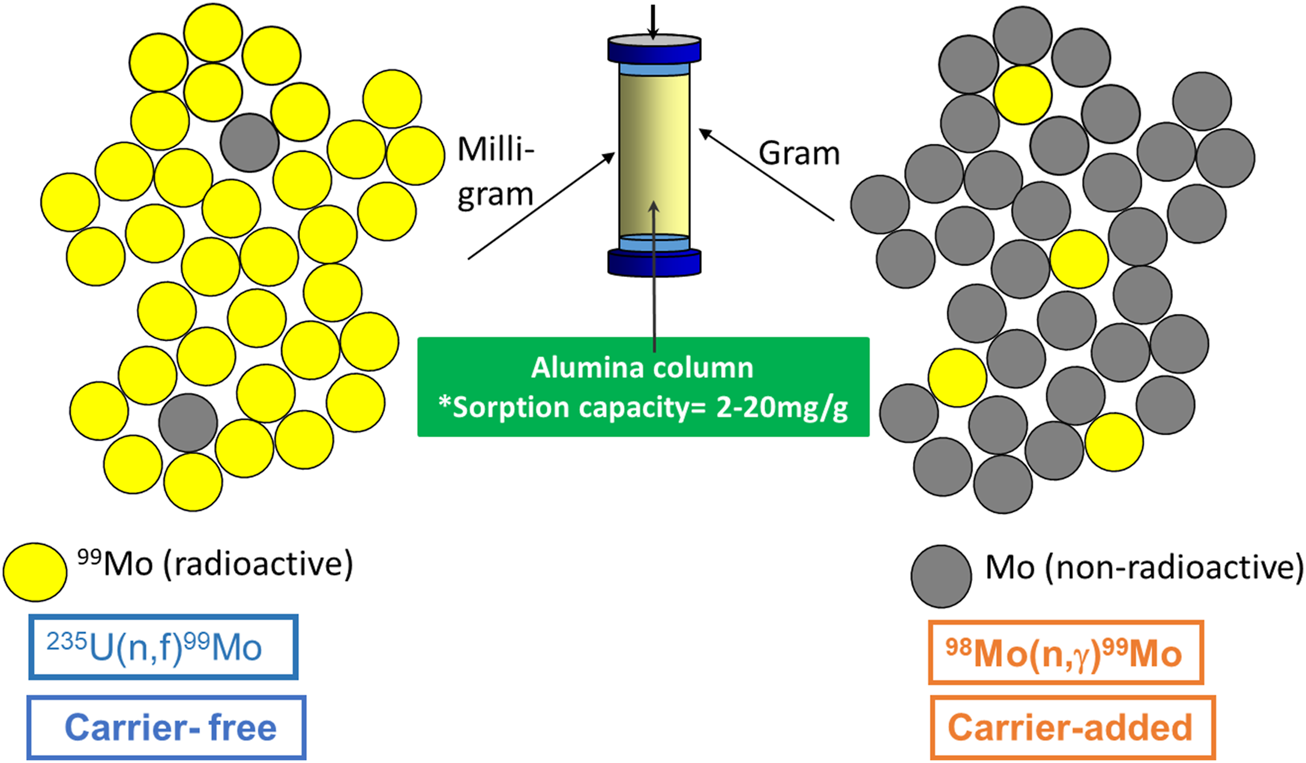

2.1.2 Neutron-capture-produced 99Mo

99Mo can also be produced through the neutron activation of natural or enriched 98Mo targets in the thermal flux of typical research reactors. This technology has been used for 99Mo production for more than five decades. Molybdenum has seven different naturally occurring stable isotopes, as shown in Table 6. 98Mo is the most naturally abundant molybdenum isotope with 24.13%.

TABLE 6

| Isotope | Abundance, % | Thermal (n,γ) cross-section, barn | Half-life | Mode of decay | Decay product | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 92Mo | 14.649 | 2E-7a | Stable | N.A | N.A | 92Mo(n,γ)93mMo |

| 0.08 | 92Mo(n,γ)93gMo | |||||

| 94Mo | 9.187 | 0.34 | Stable | N.A | N.A | |

| 95Mo | 15.873 | 13.4 | Stable | N.A | N.A | |

| 96Mo | 16.673 | 0.55 | Stable | N.A | N.A | |

| 97Mo | 9.582 | 2.2 | Stable | N.A | N.A | |

| 98Mo | 24.292 | 0.130 | Stable | N.A | N.A | |

| 100Mo | 9.744 | 0.199 | 7.01E18 years | Double β- | 100Ru (Stable) | The only unstable naturally occurring isotope of Mo |

The naturally occurring molybdenum isotopes (Magill et al., 2022).

This value is deduced from (Gedeonov and Nosov, 1989).

During the irradiation process, the target nucleus, 98Mo, captures one thermal neutron and emits gamma rays to form 99Mo according to the nuclear reaction . The produced 99Mo is a Carrier-Added (CA) product (not carrier-free) with low specific activity, as only a small portion of molybdenum is converted to 99Mo. In other words, the 99Mo activity is diluted with the inactive bulk of the 98Mo target (Molinski, 1982). The specific activity of the produced 99Mo can be determined from the following equation:

Where;

S is the specific activity of the produced 99Mo in mCi/g or Bq/g,

L is the Avogadro number (6.022 × 1023),

σ is the thermal activation cross-section (0.13 barns, i.e., 0.13 × 10–24 cm2),

is the thermal neutron flux in n/cm2s,

a is the abundance of 98Mo isotope (∼24.14%),

A is the atomic mass of molybdenum (95.94),

t is the total irradiation time,

λ is the radioactive decay constant (ln2/T1/2),

T1/2 is the half-life of the 99Mo product (T1/2 = 65.94 h), and it is in the same unit as t.

Based on Eq 1, 2, the 99Mo specific activity at the End of Bombardment (EOB) mainly depends on some essential parameters, such as the value of the neutron flux in the irradiation channel, the effective cross-section, the irradiation period, and the 98Mo content in the irradiated target (Binney and Scherpdz, 1978; Hetherington and Boyd, 1999).

The use of enriched 98Mo target material provides an adequate opportunity to enhance the specific activity. This increase is proportional to the enrichment factor. Therefore, the specific activity yield of the produced 99Mo can be improved by a factor of four using enriched targets, which have a 98Mo content ≥96%.

98Mo targets can also be defined according to the chemical form of the target material, which involves the use of MoO3 or Mo metal. The irradiated MoO3 powder can be easily dissolved compared to Mo metal. However, when molybdenum metal is used, the amount of 98Mo in the same irradiation space is higher, resulting in higher 99Mo yields per Gram material.

One of the main parameters that limit the specific activity that results from this method is the small neutron capture cross-section of 98Mo targets, which is 0.13 barns for thermal neutrons. However, this value can be increased for the same target to 6.7 barns when the irradiation is conducted in the epithermal energy region (Lavi, 1978; IAEA, 2013a). In practice, specific activities of 10–15 Ci/g Mo have been achieved (Ryabchikov et al., 2004). The produced specific activity of 99Mo from neutron irradiation of 98Mo targets is particularly low compared to 99Mo provided by the uranium fission method (see Table 3). However, the specific activity can be increased by a factor of eight if an enriched 98Mo target of a particular geometry is irradiated in a high flux reactor (Ali and Ache, 1987; Hetherington and Boyd, 1999; Hasan and Prelas, 2020).

In principle, commercial power reactors offer an adequate neutron spectrum and neutron flux for producing Low Specific Activity (LSA) 99Mo. However, power reactors are usually not equipped for the introduction of samples for irradiation during operation. This fact significantly limits the use of power reactors as irradiation sources. There are exceptions. The new EPR reactors and the older KONVOI type Pressurized Water Reactors (PWR) have a built-in, so-called aeroball system for in-situ flux measurements. During operation, 51V spheres of 1.7 mm diameter can be filled in columns in the reactor, irradiated for a short time period, and extracted again. The produced activity is then measured on a so-called measuring table (Konheiser et al., 2016; Framatome, 2019a). This system could be repurposed to introduce metallic Mo-spheres or MoO3 ceramic spheres for irradiation (Framatome, 2019b). As the columns are several meters long and there are a large number of columns, sufficient amounts of Mo can be irradiated.

Furthermore, one of the potential projects that utilize neutron-capture-produced 99Mo has been implemented by Northstar Company in the United States. Northstar uses the Missouri University Research Reactor (MURR) to irradiate both natural and enriched 98Mo targets. The estimated production capacity of this project will be about 4500 six-day Curie 99Mo per week by 2024 (NEA, 2019). Northstar is supplying LSA 99Mo solution to be used with a generator system of RadioGenix, which produces 99mTc in a computer-controlled generator system.

Clearly, the neutron activation technology eliminates proliferation concerns, as it offers a clean method to provide 99Mo without the need to handle any fissile materials. In addition, it asks for fewer technological requirements and financial budgets compared to the uranium fission approach (Boyd, 1982a). Moreover, based on the fact that only molybdenum targets are irradiated, this process involves less demanding chemical separation and purification steps as well as the generated radioactive waste level can be neglected. Furthermore, the good global distribution of reactors with high neutron flux capability could significantly support the 99Mo economy. The method is fast, and a time span of 3 days from the EOB to the arrival of the generator to the end-user is feasible. On the one hand, the 99Mo decay loss can be minimized, as the 99Mo activity can be delivered in a short period directly after production. On the other hand, a stable supply of 99Mo can be guaranteed even in case of any unplanned interruptions that may arise from the fission production line.

Despite the potential advantages of producing neutron-capture-produced 99Mo, its utility for the production of 99mTc generators faces some potential challenges, especially with conventional alumina columns. Using such materials leads to a large elution volume with a very low 99mTc radioactive concentration and a significant 99Mo breakthrough risk. Recently, extensive research efforts have been conducted for alternative strategies to overcome these problems. In this regard, the challenges and the current progress are therefore discussed in more detail in Sections 3.2, 3.3.

2.2 Accelerator-based 99Mo production

Recently, there has been a growing interest in using modern particle accelerators as a promising solution to produce 99Mo for medical applications. This approach allows the production of 99Mo without the need for HEU targets and generates relatively low amounts of radioactive waste compared to nuclear reactors (Van der Marck et al., 2010). The idea is built on the acceleration of charged particles, such as protons, deuterons, or electrons, to induce nuclear reactions in the target material. In some cases, the accelerated particles can interact with the target material and directly produce 99Mo or even 99mTc. In other cases, the reaction becomes more complex and takes place in two steps. In the first step, the primary charged particles are successfully accelerated and strike an intermediate target material to produce secondary particles, such as neutrons or high-energy photons. Then, the secondary particles interact with the main target material to produce 99Mo (NEA, 2010). The choice of one of these techniques mainly depends on the post-irradiation 99Mo production capability. The primary accelerator-based 99Mo − or direct 99mTc production approaches are summarized in Table 7. In Table 7, the irradiation yields were calculated under modern-day, realistic assumptions concerning beam intensities using publicly available nuclear codes. For photonuclear reactions, it was assumed that the electron beam is delivered by an IBA TT-300 HE rhodotron (IBA, 2018) impinging on a high-power converter target (Türler et al., 2021). The photon spectrum and the yield of 99Mo were calculated by Vagheian (Vagheian, 2022). For proton and deuteron-induced reactions, it was assumed that the beam is being delivered by a IBA Cyclone IKON-1000 cyclotron as a typical representative of accelerators in the 30 MeV energy range (IBA, 2022). It was assumed that a solid target station could accept a maximum proton beam current of 400 μA (i.e., Nirta High Power Solid target (90–400 μA)), since molybdenum is a very refractive element. For the calculations, the web-based “Medical Isotope Browser” was employed (see the footnote in Table 7). As can be seen from Table 7, the production of 99Mo with an electron accelerator from 100Mo appears to be most promising due to the large activities that can be produced. Proton irradiations of 100Mo yield significantly less yield of 99Mo, while producing more undesired by-products. The direct production of 99mTc from 100Mo is a viable option but significantly reduces the distribution radius of the product (see Section 3.1). In the following, the accelerator-based production of 99Mo is discussed in more detail.

TABLE 7

| Facility | Accelerated particle | Incident particle | Target material | Nuclear reaction | Reaction parameters | Thick target yield at EOB, Ci | Available activity at calibration, Ci | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target thickness, mm | Incident energy, MeV | Incident currenta, µA | |||||||

| Electron accelerator | Electron | Photon | nat.U | 238U(γ, f)99Mo | 3.17b | 40 | 3125 | 2.30c | 1.08 |

| Electron | Photon | 100Mo | 100Mo(γ,n)99Mo | 9.96b | 40 | 3125 | 137c | 64.34 | |

| Deuteron accelerator | Deuteron | Neutron | 100Mo | 100Mo(n,2n)99Mo | N.A | N.A | N.A | N.A | N.A |

| Deuteron | Deuteron | 100Mo | 100Mo(d,p2n) 99Mo | 0.17 | 15 | 100 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| 0.20 | 16 | 100 | 0.03 | 0.01 | |||||

| 0.24 | 17 | 100 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |||||

| 0.28 | 18 | 100 | 0.07 | 0.034 | |||||

| Deuteron | Deuteron | 100Mo | 100Mo(d,3n)99mTc | 0.14 | 15 | 100 | 0.35 | N.A | |

| 0.18 | 16 | 100 | 0.67 | N.A | |||||

| 0.21 | 17 | 100 | 1.12 | N.A | |||||

| 0.25 | 18 | 100 | 1.73 | N.A | |||||

| Proton accelerator | Proton | Proton | 100Mo | 100Mo(p,pn)99Mo 100Mo (p,2p)99Nb →99Mo | 0.30 | 15 | 400 | 0.26 | 0.12 |

| 0.61 | 20 | 400 | 2.52 | 1.18 | |||||

| 0.99 | 25 | 400 | 7.36 | 3.46 | |||||

| 1.43 | 30 | 400 | 13.85 | 6.50 | |||||

| 1.92 | 35 | 400 | 21.44 | 10.07 | |||||

| Proton | Proton | 232Th | 232Th(p,f)99Mo | N.A | N.A | N.A | N.A | N.A | |

| Proton | Proton | 100Mo | 100Mo(p,2n)99mTc | 0.32 | 15 | 400 | 21.67 | N.A | |

| 0.63 | 20 | 400 | 48.01 | N.A | |||||

| 1.01 | 25 | 400 | 62.23 | N.A | |||||

| 1.45 | 30 | 400 | 68.18 | N.A | |||||

| 1.94 | 35 | 400 | 73.04 | N.A | |||||

| Proton | Proton | 98Mo | 98Mo(p,γ) 99mTc | 2.07 | 35 | 400 | 0.01 | N.A | |

| α-particle accelerator | α-particle | α-particle | 96Zr | 96Zr(α,n)99Mo | 0.06 | 15 | 100 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| 0.11 | 20 | 100 | 0.04 | 0.02 | |||||

| 0.16 | 25 | 100 | 0.04 | 0.02 | |||||

| 0.22 | 30 | 100 | 0.04 | 0.02 | |||||

| 0.29 | 35 | 100 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |||||

The main accelerator-based 99Mo and 99mTc production routes and their production capabilities per day.

The data were calculated using “Medical Isotope Browser” of IAEA: https://www-nds.iaea.org/relnsd/isotopia/isotopia.html (accessed on 08.06.2022) utilizing recommended cross section data from (Tarkanyi et al., 2019).

https://www.iba-radiopharmasolutions.com/cyclotrons-equipment (accessed on 08.06.2022).

Thickness of 1 radiation length (1 X0).

Yield of a cylindrical target of 1 X0 thickness and 2 cm diameter at a distance of 2 cm from a distributed Ta converter of 4.5 mm thickness. The thick target yield can be obtained by multiplication by a factor of about 4.

2.2.1 Photonuclear reactions

With electron accelerators, a high-intensity electron beam is allowed to impinge on a dense target material to produce Bremsstrahlung photons. These photons can be used to produce

99Mo by two main strategies:

1- Photon-induced fission (photofission) reaction.

2- Photon-induced nuclear (photonuclear) reaction.

In the photo-fission method, high specific activity 99Mo can be obtained from the reaction . The 99Mo production output is approximately 3700 times lower than the neutron-induced uranium fission method, attributed to the considerably lower reaction cross-section (0.16 barn) (van der Marck, 2010; Qaim, 2012). After the irradiation process is accomplished, 99Mo is chemically separated from the 238U targets in the same way as the previously described technique for irradiated HEU targets in nuclear reactors (Owen et al., 2014). For commercial production, high energy accelerators need to be used (Ruth, 2009). However, this option is still under demonstration. Using 235U targets increase the 99Mo yield (Krishichayan et al., 2017). Nonetheless, this option does not have enough justification due to higher production costs, high process complexity, and proliferation issues (Bertsche, 2010).

The photonuclear transmutation reaction offers a promising strategy for 99Mo production according to the reaction . The maximum cross-section of this reaction is 0.15 barn at a photon energy of 14 MeV (van der Marck, 2010; Crasta et al., 2011), which is larger than the 238U photo-fission reaction for producing 99Mo, which results in a higher 99Mo yield by a factor of about 17 in case highly enriched 100Mo targets are used (Bertsche, 2010). Specific activities of about 5 Ci/G of 100Mo can be achieved, resulting in production capacities of more than 100 Ci per day. Mang’era et al. (2015) reported the production of 2.4–3 GBq/h/g/mA 99Mo from 97.39% enriched 100Mo targets. Commercially available electron accelerators can deliver up to 3 mA of beam at energies up to 40 MeV. Also, a high-power converter target design has recently been submitted as patent application (Türler et al., 2021). Therefore, future production of 100 Ci per day with a specific activity of 5 Ci/g appears feasible. Nevertheless, the specific activity yield is still lower than for the reaction. In order to achieve a sustainable long-term 99Mo supply, two main difficulties need to be urgently solved. First, while high power electron accelerators are commercially available, suitable converter targets that can accept more than 100 kW beam power still need to be developed (Türler et al., 2021). Second, the possibility of reusing the valuable 100Mo target material should receive intensive research consideration (Bertsche, 2010).

2.2.2 14.1 MeV neutron-induced reactions

99Mo can also be produced through the bombardment of a 100Mo target with high energy neutrons according to the nuclear reaction 100Mo(n,2n)99Mo. Here, the 14.1 MeV neutrons are generated in the reaction 3H(d,n)4He. The reaction cross-section for the reaction 100Mo(n,2n)99Mo is about 1.5 barn at the neutron energy level of 14.1 MeV, which is ten times higher than the cross-section of the 98Mo(n,γ)99Mo reaction in the thermal region. In addition, a long irradiation period of more than 8 days and a high-intensity neutron flux ≥ 1013 n/cm2s is required (Nagai and Hatsukawa, 2009). Even so, the production of low specific 99Mo with large amounts of inactive carrier is still present even with 100Mo targets of 100% enrichment. Under the conditions mentioned above, the specific activity of the produced 99Mo was estimated at about 2 Ci/g (79 GBq/g).

In another approach, 14 MeV neutrons from a D-T generator are directed at a low enriched 235U salt solution, where 99Mo is produced as a fission product and periodically separated. This approach is being commercially exploited by Shine Medical Technologies Inc. (Wisconsin, United States) (Ruth, 2020).

2.2.3 Spallation neutron-induced reactions

Similar to the concept of neutron-induced fission or capture reactions in a nuclear reactor, 99Mo can be produced with the use of an Accelerator-Driven Subcritical Reactor (ADSR) through 235U(n,f)99Mo and 98Mo(n,γ)99Mo reactions (Abderrahim et al., 2010; Bertsche, 2010; NEA, 2010; Owen et al., 2014; Syarip et al., 2018). However, the used neutrons have a different origin. High-intensity neutron flux can be generated following the bombardment of a heavy mass target material with an accelerated proton beam, such as lead, uranium, tungsten, or tantalum. This reaction produces fast neutrons with a kinetic energy level of more than 1 MeV up to almost the beam energy of the proton beam, which then is slowed down to the epithermal energy level with the help of a moderator. These conditions offer a unique opportunity to obtain a reasonable 99Mo yield with a relatively high specific activity using the 98Mo(n,γ)99Mo option. Uranium targets have to undergo routine chemical processing to provide purified active solution (Pillai et al., 2013).

2.2.4 Other production methods

Many research groups have proposed other possibilities through proton- or deuteron-induced 99Mo production (Beaver and Hupf, 1971; Lagunas-Solar et al., 1991; IAEA, 1999; Hermanne et al., 2007). For example, the reaction has a small cross-section and yields low amounts of 99Mo. Meanwhile, the reaction has a twofold higher reaction cross-section than the former. Nonetheless, both require high-power accelerators. Despite using enriched 100Mo targets and high-energy power accelerators, these two strategies seem to be not satisfactory for stable long-term production of 99Mo for medical use.

3 99mTc production and supply strategies: Challenges and progress

3.1 Cyclotron-produced 99mTc

The severe 99Mo production shortage during the past few years, along with the widespread concerns of unexpected future 99Mo supply inadequacy, have generated a growing need for establishing an independent sustainable supply of 99mTc. Consequently, many research projects have been established to promote the direct production of 99mTc exploiting cyclotron production. The cyclotron-based 99mTc production can provide an independent option for domestic utilization (IAEA, 1999; Ruth, 2009, 2014; Gagnon et al., 2011; Hanemaayer et al., 2014; Owen et al., 2014; Metello, 2015; Boschi et al., 2017; Martini et al., 2018).

Several approaches have been proposed for direct 99mTc production, such as 100Mo(p,2n)99mTc, 98Mo(p,γ)99mTc, 100Mo(d,3n)99mTc, 98Mo(d,n)99mTc, 97Mo(d,γ)99mTc, and 96Mo(α,p)99mTc. It is pertinent to point out that the proton-induced reactions produce the highest production yields compared to deuteron or alpha particle-induced reactions. In addition, accelerators with high beam intensity of deuterons or alpha particles are currently rare. For these reasons, they received less attention (Lagunas-Solar et al., 1991; IAEA, 1999, 2017; Takács et al., 2003; Guerin et al., 2010; Owen et al., 2014; Stolarz et al., 2015).

The direct production of the 99mTc using energetic proton beams involves two reactions; and . The former has a very small reaction cross-section and produces a low 99mTc yield, which is not convenient for large-scale production (Lagunas-Solar et al., 1991; Takács et al., 2003). The is more promising for large-scale production because it has a higher cross-section, and its optimum proton energy range is compatible with most conventionally used cyclotrons. Therefore, it has been attracting considerable attention from the scientific community (Lagunas-Solar et al., 1991; Takács et al., 2003; Martini et al., 2018). This approach was first mentioned by Beaver and Hupf at the University of Miami School of Medicine in 1971 using enriched 100Mo targets (Beaver and Hupf, 1971). Afterward, the possibility of using natural 100Mo targets was evaluated by Almeida and Helus in 1977 (Lagunas-Solar et al., 1991; IAEA, 1999). Recently, many attempts have been conducted to explore the most appropriate conditions to produce considerable amounts of high specific activity of 99mTc with the least possible impurity level. These studies concluded that the final 99mTc product greatly depends on three primary factors: the 100Mo target enrichment quality, the irradiation conditions, and the duration of the chemical processing.

The most commonly used molybdenum target material is the Mo metal. In addition, the utilization of MoO3 and Mo2C is also possible (Richards et al., 2013). The fabrication of the molybdenum targets can be developed with the help of several technical advances. These approaches involve preparing foils, pressing and thermal sintering of molybdenum powder, vacuum sputtering technology, laser beam pressed molybdenum powder method, electrochemical plating technique, and electrophoretic deposition followed by thermal sintering process (Richards et al., 2013; Hanemaayer et al., 2014; Stolarz et al., 2015; Hou et al., 2016; Martini et al., 2018). The target purity plays a crucial role and greatly affects the quality of the final 99mTc product. The contribution of other molybdenum isotopes with 100Mo in the target material leads to producing different impurities such as Tc, Nb, Ru, and Zr (Beaver and Hupf, 1971; Lagunas-Solar et al., 1991; IAEA, 1999; Guerin et al., 2010; Owen et al., 2014; Hou et al., 2016). To reduce the impurity level, the isotopic abundance of 100Mo targets must not be less than 99.5%. Some of the produced impurities can be removed during the separation and purification processes. However, the different Tc isotopes have the same chemical behavior as 99mTc. Therefore, the separation of these isotopes poses considerable laborious challenges, especially with current conventional separation technology. The Tc isotopes can be classified into two groups. The first group involves the long-lived radioisotopes, such as 99gTc (T1/2 = 2.11×105 y), 98Tc (T1/2 = 4.2×106 y), and 97gTc (T1/2 = 4.21×106 y). These radioisotopes decrease the final specific activity of the product, but they may not be involved in an additional dose for the patient (Beaver and Hupf, 1971; Lagunas-Solar et al., 1991). On the other hand, the second group contains the shorter half-lives radioisotopes, such as 93mTc (T1/2 = 43.5 min), 93gTc (T1/2 = 2.75 h), 94mTc (T1/2 = 52 min), 94gTc (T1/2 = 4.9 h), 95mTc (T1/2 = 61 d), 95gTc (T1/2 = 20 h), 96mTc (T1/2 = 51.5 min), 96gTc (T1/2 = 4.28 h), and 100Tc (T1/2 = 15.8 s). This group not only substantially drops the specific activity of the final product, but also delivers up to 30% extra unjustified dose to the patient (Beaver and Hupf, 1971; Lagunas-Solar et al., 1991; IAEA, 1999, 2017; Hou et al., 2012; Lededa et al., 2012; Owen et al., 2014; Meléndez-Alafort et al., 2019). Accordingly, the optimization of irradiation parameters offers another opportunity to minimize the produced technetium impurities. These parameters include the bombarding beam energy, irradiation time, and incident beam intensity.

As a generic rule, the higher the proton energy and the longer irradiation time, the higher the production yield. However, these two factors have to be well-controlled to reduce the co-production of undesirable impurities, resulting in a high level of specific activity product obtained. The threshold proton energy for the reactions , , and are 7.7, 17, and 24 MeV, respectively. In addition, further side reactions can take place in the energy range above 24 MeV. Therefore, the optimum bombarding energy is preferably maintained at an energy level lower than 24 MeV and applies the shortest possible irradiation time that can satisfy the production demand plan (Beaver and Hupf, 1971; Esposito et al., 2013; IAEA, 2017, 1999).

In order to achieve a high production yield, the beam power intensity should be set to the highest possible value. This beam current crucially depends on the target material, the applied incident beam angle, and the cooling system during the irradiation process (Beaver and Hupf, 1971; IAEA, 1999). It is worth mentioning that molybdenum targets have preferable chemical and physical properties reflected by their high melting point and excellent thermal conductivity. Therefore, they can withstand high beam currents. The target cooling process is also influenced by the thermal conductivity of the target material and the temperature of the used cooling item. Effective target cooling can be achieved by applying helium flow on the front side and water-cooling of the supporting material of the target during the irradiation process. Some research studies proposed the use of liquid nitrogen instead of water-cooling for more effective target cooling (IAEA, 2017, 1999).

After completing the irradiation process, the target is left to cool down to reduce the incorporation of short-lived impurities in the final product, followed by chemical processing. This step is crucial and should be achieved in the shortest possible time to minimize 99mTc decay loss (Qaim, 2012). The post-production target processing can be achieved in two steps: target dissolution and chemical separation and purification. The efficient dissolution of the molybdenum targets is paramount for an effective 99mTc recovery. The target dissolution can be performed either by chemical or electrochemical procedures. The chemical dissolution can be performed with the help of concentrated sodium hydroxide, hydrogen peroxide, and heating. In the case of foil targets, concentrated acids can also be used. The electrochemical dissolution system consists of the molybdenum target as an anode, a platinum layer as a cathode, and potassium hydroxide, which works as an electrolyte. Electrochemical methods may involve violent reactions and need double the time to achieve the same task compared to chemical methods (Gumiela, 2018; IAEA, 2017, 1999).

Many potential techniques have been implemented for the 99mTc recovery from dissolved 100Mo targets. Because of the short half-live of 99mTc, a fast separation reaction is a key to selecting the extraction method. The most commonly used methods include solvent extraction, which can be carried out with the use of Methyl Ethyl Ketone (MEK) or Cetyl Trimethyl Ammonium Bromide (CTAB) (Martini et al., 2018). Column chromatographic separation methods involve the use of ion exchanger sorbent materials with high radiation resistance, such as Dowex-1 or Polyethylene Glycol (PEG). Some other techniques have also been proposed, such as dry thermo-chromatographic extraction and the chemical precipitation of the molybdenum as a hetero-poly acid salt. The former generates small quantities of waste, and the latter could provide a reasonable separation yield. Nevertheless, both strategies are not widely utilized (IAEA, 1999; Boschi et al., 2017; Gumiela, 2018).

Based on these discussions and as mentioned earlier, the cyclotron-produced

99mTc technology has been extensively studied in recent years, and some success has been achieved. Therefore, this method can be regarded as a backup solution for

99mTc supply to deal with emergencies. However, its potential is inadequate to replace the current

99Mo/

99mTc generator production completely; as the following critical issues still call for convincing answers:

• Only for regional consumption: The short half-life of 99mTc (T1/2 = 6.01 h) restricts its wide-scale distribution. As a result, the delivery advantage is only limited to hospitals located near the production sites. Therefore, the implementation of this supply strategy necessarily asks for an even geographic distribution of cyclotrons.

• High cost per dose: The end-user should receive the required dose at a reasonable price, and the dose price should be competitive with that delivered from a 99Mo/99mTc generator. The use of enriched 100Mo targets to ensure the production of high-quality 99mTc increases the production cost. In addition, the recycling process of the used target material adds an extra production expenditure. Furthermore, the long post-irradiation processing step and the transportation requirements are reflected by the loss of 99mTc radioactivity. All these parameters can be translated into a significant cost factor.

• A low specific activity product delivers extra radiation dose to the patients: The utilization of highly enriched 100Mo targets is vital to produce 99mTc with high specific activity suitable for imaging applications. A 100% isotopic purity of 100Mo targets is hard to achieve, and small quantities of other stable Mo isotopes are constantly incorporated into the target material. Consequently, considerable amounts of different technetium isotopes are always co-produced. On the one hand, these impurities reduce the specific activity of the produced 99mTc product, which significantly affects the labeling efficacy of 99mTc-radiopharmaceutical kits. On the other hand, it may contribute to additional radiation exposure to the patient (Hou et al., 2012; Lededa et al., 2012; Selivanova et al., 2015; Meléndez-Alafort et al., 2019).

• Uncertainty of long-term supply capability: The direct production of 99mTc has been proposed since 1971, and it has not been thoughtfully implemented as a long-term supply strategy. Many recent efforts have focused on establishing a large-scale 99mTc supply on a daily routine basis. However, several problems need to be solved. These challenges can be briefly summarized in the need for a sufficient daily availability of patient doses at a reasonable price. Additionally, this strategy continues asking for a realistic supply plan design that can deal with the production difficulties and find innovative logistic solutions to meet the rapid product delivery requirements.

3.2 99Mo/99mTc generators

Despite the fast global spread of diagnostic scans using 99mTc-radiopharmaceuticals, the 99mTc availability at the hospitals and nuclear pharmacies continues to be a potential challenge. These challenges include the production difficulties, notable price, and remarkable radioactivity loss due to frequent deliveries to the usage sites. Accordingly, its effective utilization is only restricted to sites with a well and close connection to the production centers (Sakr et al., 2017). In the light of this perceived need, different 99Mo/99mTc generator strategies have been proposed and developed. 99mTc generators are considered the most widely used strategy to ensure the ease of 99mTc availability in a cost-efficient manner. In other words, it allows conducting a variety of 99mTc scans independently of on-site production requirements (Knapp and Mirzadeh, 1994; Chakravarty et al., 2012a, 2012b; Knapp and Baum, 2012; Chakravarty and Dash, 2013; Sakr et al., 2017).

3.2.1 99Mo/99mTc radioactive equilibrium in the generator system

The 99Mo/99mTc generator technology has been developed to offer an easy and repetitive on-site supply of 99mTc at desirable time intervals. Historically, 99Mo/99mTc generators were named “cows”, from which a fresh 99mTc radioactivity can be periodically “milked” or extracted. Based on the fact that 99Mo and 99mTc are radioisotopes of two different elements, they have unique differences in their chemical and physical properties, and the generator system can supply 99mTc with high specific activity, i.e., Non-Carrier-Added grade (NCA) and with high radionuclidic purity acceptable for radiopharmaceutical preparations (Lebowitz and Richards, 1974; Molinski, 1982; IAEA, 2013b).

99Mo/99mTc generators are efficient radiochemical separation tools, by which a convincingly purified yield of the daughter, 99mTc, can be effectively extracted from the decay of the parent 99Mo. In other words, the 99Mo/99mTc generator concept is based on housing 99Mo to decay. Then, a complete separation of the generated 99mTc can be performed without any disturbance of 99Mo. This separation process is managed through the 99Mo-decay/99mTc-growth concept (Lebowitz and Richards, 1974; Molinski, 1982; Guillaume and Brihaye, 1986; Saha, 1992; Osso and Knapp, 2011; Knapp and Baum, 2012; Chakravarty and Dash, 2013; Gumiela, 2018).

Generally, the generator concept is based on the parent/daughter relationship, by which the parent, with a longer half-life, decays to yield its shorter-lived daughter. Hence, a sort of radioactive equilibrium is established. This state is called secular or transient equilibrium, depending on the ratio between the two physical half-lives of the parent and its daughter. The secular equilibrium arises when the parent’s half-life is 100 times longer than the half-life of the daughter. Whereas the transient equilibrium, as in the 99Mo/99mTc generator system, is recognized when the parent’s half-life is ten-fold longer than that of the daughter (Sakr et al., 2017). Figure 4 illustrates the transient equilibrium between 99Mo and 99mTc.

FIGURE 4

Transient radioactive equilibrium in 99Mo/99mTc generator system. Ael: Eluted 99mTc activity. A0: 99Mo activity at calibration.

The equilibrium between 99Mo and 99mTc is reached after approximately four elapsed half-lives of 99mTc. During the 99mTc ingrowth, its production is remarkably faster than its decay. After the equilibrium is established, the 99mTc growth and decay rates are equal. At this point, 99mTc apparently decays with the longer half-live of 99Mo. This advantage considerably reduces the 99mTc radioactivity loss during shipment to remote users. However, it decays with its physical half-life directly after its elution from the generator. Directly after the elution, the generator starts the same process from the beginning, as 99Mo decays to give rise to new fresh 99mTc. Accordingly, 99mTc begins to be re-built-up again (Lebowitz and Richards, 1974; IAEA, 2013b). The growth, extraction, and regrowth of 99mTc are non-stop procedures. Consequently, the elution step can be repeated as long as sufficient 99Mo radioactivity is available to conduct the required applications. Therefore, 99mTc can be eluted from the generator at periodical elution batches.

The mathematical correlation that describes the 99mTc growth from the decay of 99Mo can be explained using the Batemann equations, as follows (Hidalgo et al., 1967; Lebowitz and Richards, 1974; Lamson et al., 1976; Ekelman and Coursey, 1982; IAEA, 2013b):

The decay of 99Mo can be expressed as

Where:

λ: is the 99Mo decay constant,

: indicates the number of 99Mo atoms at the time (t).

: refers to the number of 99Mo atoms when t = 0.

The production of 99mTc is the same as the decay of 99Mo. Considering that 99mTc decays at a rate of. Hence, the 99mTc growth rate can be represented by:

If only 99Mo is present initially

Accordingly, the Eq 6 can be reformulated as:

Taking into account that only about 87.5% of 99Mo decays to 99mTc (IAEA, 2017).

In order to give units of disintegration per second (A) rather than atoms (N), both sides of Eq 8 are multiplied by

At the time (t), when the radioactive equilibrium between 99Mo and 99mTc activities is reached, the growth rate of 99mTc is equal to its decay rate:

Hence, the maximum activity of the 99mTc, which is present at the time (t), can be calculated from the following equation:

Clearly, the radioactive relationship between 99Mo and 99mTc offers an excellent opportunity to introduce an ideal generator system, by which the separation of the short-lived 99mTc at favorable time intervals can easily be achieved. The eluted radioactivity can be quantified using equation number (6). Nevertheless, it is significantly influenced by the elution process efficiency. Hence, the maximum 99mTc radioactivity can be eluted on a daily basis, which is one of the potential advantages of the generator system.

3.2.2 Criteria of a clinical 99Mo/99mTc generator

The effective

99Mo/

99mTc generator system should fulfill the following characteristics (

Lebowitz and Richards, 1974;

Sakr et al., 2017;

IAEA, 2018):

• Use simple, safe, and user-friendly operational protocols that avoid any violent chemical reactions and support a feasible implementation at hospitals and nuclear medicine centers.

• Assure rapid radiochemical separation to minimize the 99mTc radioactivity decay loss.

• Provide the highest possible elution yield with a reproducible separation efficiency over the generator operation lifetime.

• Capable of sustainable elutions with a negligible amount of radioactive waste.

• Provide a carrier-free 99mTc radioactivity with high specific activity without any need for purification processes.

• Supply sterile, isotonic, and pyrogen-free 99mTc radioactive solution at any elution cycle without any further need for chemical treatment.

• Produce 99mTc with high radioactive concentration adequate for the radiopharmaceuticals synthesis without any need for post-elution concentration steps.

• Supply the 99mTc radioactivity with high chemical, radiochemical, and radionuclidic purities. The chemical purity expresses how much of the produced 99mTc is free from inactive impurities that arise from the target material and/or the used chemicals. The radiochemical purity is the percentage of 99mTc radioactivity present in the pertechnetate chemical form, 99mTcO4-. The radionuclidic purity represents the percentage of the 99mTc radioactivity to the total radioactivity of its solution.

• Minimize the personnel involved during the elution process to reduce the radiation exposure dose.

• Involve the use of chemical solutions and materials with high radiation stabilities to avoid any possible contamination to 99mTc radioactivity.

3.2.3 Production technologies of 99Mo/99mTc generators

Historically, the idea of a 99Mo/99mTc generator system was first proposed in the middle of the 1950S during the development of 132Te/132I generators at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL). In this experiment, the 99mTc was detected as a trace impurity in the 132I eluted solution. Afterward, it was understood that this 99mTc was produced from its parent, 99Mo, which took the same separation path of 132Te throughout the chemical processing of the fission products. This unique parent-daughter chemistry between 99Mo and 99mTc has encouraged the fabrication of the first 99Mo/99mTc generator (Richards et al., 1982; Anderson et al., 2019). In 1957, the first 99Mo/99mTc generator was produced at BNL (Tucker et al., 1958; Molinski, 1982; Richards et al., 1982). Then, in early 1960, the first 99Mo/99mTc generator was used for clinical research at Brookhaven medical department, which paved the way for the first utilization of 99Mo/99mTc generators in clinical investigations at Argonne Cancer Research Hospital in 1961 (Richards, 1965; Lebowitz and Richards, 1974; Atkins, 1975). Later on, through the following seven decades, the idea was developed, and several 99Mo/99mTc generator structures were established based on the different physical and chemical behaviors of 99Mo and 99mTc radionuclides (Allen, 1965; Boyd, 1987; IAEA, 1995, 2013b; Maoliang, 1997; Osso and Knapp, 2011; Knapp and Baum, 2012; Mostafa et al., 2016).

The careful selection of the radiochemical separation strategy is considered the cornerstone for the fundamental development of 99mTc generators. In fact, this selection focuses explicitly on simplifying the extraction process and avoiding any technical complexities for the users. In addition, it supplies the possible maximum 99mTc yield with the minimum quantity of radioactive waste. Furthermore, it supports a rapid 99mTc elution with high-performance quality, which consequently; can be easily adopted as a mature commercial technology. In the light of this context, the following subsidiary sections underline the critical features of potential 99Mo/99mTc generators production strategies. Table 8 highlights a comparison between the potential development technologies of 99mTc radioisotope generators.

TABLE 8

| Production technology | Separation technique | Advantages | Disadvantages | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Column chromatography | Based on alumina | Using (n,f)99Mo | Selective sorption of 99Mo (solid-phase extraction) | • Well-established technology | • Increases the nuclear proliferation concerns | |

| • Produces clinical-grade 99mTc in high radionuclidic, radiochemical, and chemical purities | • Produces large quantities of long-lived radioactive wastes | |||||

| • Supplies 99mTc in high RAC | ||||||

| Based on gel matrices | Using (n,γ)99Mo | • Eliminates proliferation concerns | • Supply 99mTc with very low RAC | |||

| • Retention of 99mTc on the column matrix | ||||||

| • Production of undesirable radioactive impurities | ||||||

| • A multi-step procedure leads to the loss of the 99Mo radioactivity | ||||||

| Based on nano-sorbents | Using (n,γ)99Mo | • Eliminates proliferation concerns | • Not yet demonstrated at activity scale necessary for clinical use | |||

| • The production of a 99mTc with desirable RAC | • Is not currently standard practice in 99Mo/99mTc generators | |||||

| • Improves 99Mo economy | ||||||

| • Inexpensive | ||||||

| Sublimation | Differences in the sublimation temperatures of 99Mo and 99mTc oxides | • Generates a 99mTc radionuclide of high purity | • Complex procedure | |||

| • Require high degree of safety standards | ||||||

| • Low 99mTc separation efficiency yield from 99Mo | ||||||

| Solvent extraction | Difference in the solubility of 99Mo and 99mTc in two immiscible liquid phases | • Low stability of the organic solvents | ||||

| • Low separation efficiency | ||||||

| • Requires a very high degree of radiation safety considerations | ||||||

| Electrochemical | Difference in the reduction potential of 99Mo and 99mTc | • The capacity is not limited by the amount of sorbent or extractant | • Expensive | |||

| • Generate H2 and O2, leading to explosion danger | ||||||

| Supported Liquid Membrane (SLM) | Selective extraction of the 99mTc using porous hydrophobic membrane | • Slow separation kinetics | ||||

| • Unsatisfactory 99mTc yield | ||||||

| • 99Mo breakthrough | ||||||

| • Radiation instability of the membrane and the extractant | ||||||

| • Generates significant amounts of radioactive waste | ||||||

The potential production strategies of 99Mo/99mTc generators.

3.2.3.1 Sublimation generators

Sublimation is a physical phenomenon, which can be defined as the direct conversion of solids into a gas without moving through the liquid state. Perrier and Segrè were the first who described the possibility of a 99mTc thermal extraction from 99Mo based on the difference in the sublimation temperatures or volatilities of their oxides (Perrier and Segrè, 1937). Tc2O7 and MoO3 become volatile at temperatures of 550 and 1,000°C, respectively (Perrier and Segrè, 1937; Childs, 2017). The separation steps were reported through several research studies. The irradiated 99MoO3 target is carefully placed inside a muffle furnace, in which a flow of oxygen stream is allowed to pass through. Then, the temperature is gradually elevated to about 800 °C. On heating, Tc2O7 is formed, which sublimates at 550°C. After that, the volatile Tc2O7 vapors are carried by the oxygen stream and trapped using a cooled surface. Finally, they are allowed to be completely dissolved in water or saline solution to obtain 99mTcO4− (Hallaba and El-Asrag, 1975; Molinski, 1982; Zsinka, 1987; Miller, 1995; Christian et al., 2000; IAEA, 2013b).

This generator strategy generates a small volume of radioactive waste. In addition, it provides high specific activity 99mTc even if 99Mo of low specific activity origin is available. However, attempts to implement this technique in nuclear medicine departments as a clinical-based generator system suffered from several critical constraints. For instance, it includes the manipulation of bulk, complex, and fragile equipment, which needs a meticulous operational methodology and an advanced level of precautions and safety standards. Moreover, the 99mTc separation yield is very low. Furthermore, it uses high heating temperatures, which may lead to a serious radiation contamination risk in case of any operational failure. Accordingly, these potential drawbacks discouraged further development plans in this direction.

3.2.3.2 Solvent extraction generators

The solvent extraction-based generator is a multi-step separation technique by which 99mTcO4- can be recovered from an aqueous solution that contains the 99Mo/99mTc mixture by the extraction into an organic solvent (IAEA, 2013b). The separation of 99mTc from its parent with the help of organic extractants was originally demonstrated by Gerlit in 1956 (Gerlit, 1956; Anders, 1960; Lebowitz and Richards, 1974; Molinski, 1982).

The separation process involves the dissolution of the irradiated 99Mo target in an alkaline solution. Then, an organic solvent is added, which is followed by multiple-extraction cycles. Each cycle includes a vigorous shaking of the two immiscible phases to allow the 99mTcO4− to migrate from the original aqueous solution to the organic extractant phase leaving its parent behind. After that, the extractant is segregated, washed several times, and thermally evaporated. Finally, the residual precipitate is redissolved in a saline solution. The process efficiency strongly depends on the selective capability of the extractant solvent for the 99Mo/99mTc pair. In other words, the process relies on the relative distribution or solubility ratio of the two radionuclides between the extractor and the original aqueous solution (Chattopadhyay et al., 2010, 2014; IAEA, 2013b; Mitra et al., 2020).

Therefore, the ideal extractant should show a considerable selective affinity towards 99mTc and neglected distribution selectivity for 99Mo. The first used organic extractant to achieve the extraction process was Methyl Ethyl Ketone (MEK). After that, various organic solvents were reported (Allen, 1965; Anwar et al., 1968; Baker, 1971; Tachimori et al., 1971; Iqbal and Ejaz, 1974; Noronha, 1986; Bhatia and Turel, 1989; Bhatia and Turel, 1989; Minh and Lengyel, 1989; Taskaev et al., 1995; Chen and Tomasberger, 2001; Zykov et al., 2001; Skuridin and Chibisov, 2010). Even so, MEK is still considered the predominant extractant of choice because of its highly selective behavior for 99mTcO4-, which permits the production of 99mTc with high specific activity (IAEA 2017).

Practically, the solvent extraction generators are associated with a number of serious drawbacks that impede their wide-scale utilization; it is a complicated multi-step process with low extraction efficiency and requires a long separation time, resulting in the loss of 99mTc radioactivity. Moreover, the separation step consumes large volumes of the organic extractant, creating significant radioactive waste. In addition, a strong possibility of fire hazards that result from the flammable nature of MEK. Furthermore, the poor radiation stability of organic solvents may heighten the contamination risk of the final 99mTc product with some organic impurities.

3.2.3.3 Electrochemical generators

The electrochemical-based 99mTc generator can be introduced as a separation technique built on an oxidation-reduction reaction. This reaction is mainly governed by the difference in the formal reduction potential of the 99Mo/99mTc pair. Herein, the generator system consists of an electrochemical cell, in which the 99mTc radionuclide can be separated from the 99Mo/99mTc equilibrium mixture by a reduction reaction on the surface of an electrode under the effect of an external voltage in accordance with its electrochemical reduction potential, i.e., electrochemical deposition. The 99Mo/99mTc pair exhibits different electrochemical reduction potentials, and their electrochemical reduction reactions can be illustrated as follows (Chakravarty et al., 2012b; 2012c, 2011, and 2010a):

It can be observed that the 99mTcO4− species have a higher electrochemical reduction potential than the 99MoO42- ions, which offers a positive advantage in facilitating the separation step.

The process starts with the dissolution of the irradiated 99Mo target in a strong alkaline electrolyte (pH ∼ 13). Then, a constant potential is applied and adjusted for a certain period to permit the 99mTcO4- species to be electro-deposited on the surface of the cathode electrode. After that, this cathode is removed from the working cell and transferred to a new cell, where the deposited 99mTc can be stripped back and redissolved in a saline solution by applying a high reverse potential (reverse electrode polarity) for a short period. By this technique, 99mTc can be oxidized back to the solution in the form of 99mTcO4-. Eventually, 99mTc eluate is allowed to pass through an alumina column to minimize the 99Mo contamination level.

In order to achieve a satisfactory 99mTc separation yield, some parameters have to be well-optimized during the electrolysis process. For instance, careful attention should be devoted to adjusting the effective potential, proper selection of suitable electrodes and electrolysis medium candidates, and successful control of the electrolyte pH and separation time.

The applied potential is the crucial factor for a successful extraction. Generally, the electrochemical separation can be performed by either applying a constant current (galvanostatic) or a constant potential (potentiostatic) conditions. However, the potentiostatic condition offers favorable 99mTc deposition and, in the meantime, limits the precipitation of 99Mo and/or any other contaminants. The electrolysis potential should be adjusted to be more negative than the formal reduction potential of 99mTcO4- species and less negative than the electrochemical reduction potential of 99MoO42- ions. Therefore, the optimum reduction potential for the 99mTc generator system should be in the region of:

Additionally, it needs to be fully compatible with the used electrolyte to avoid any possibility of chemical degradation during the separation process. Several classes of electrolytes of organic or aqueous origin can be used. The aqueous electrolytes show higher radiation stability during the course of the electrolysis compared to organic liquids, which results in fewer chemical impurities associated with the produced 99mTc radioactive solution. However, their use is usually associated with the evolution of hydrogen gas, which lowers the pH of the electrolyte medium and may decrease the separation performance. For the working electrodes, they need to be chemically inert with considerable electrochemical and radiation resistance. The temperature of the medium should be adjusted sufficiently below the electrolyte boiling point to avoid its rapid evaporation, which results in unacceptable 99mTc solution purity. The reaction time should be established to achieve the highest possible 99mTc yield in the shortest period to minimize 99mTc radioactivity loss (Chakravarty et al., 2012b; 2012c, 2011; 2010a; 2010b).

Based on this method, Chakravarty et al., 2010a, reported the production of 99mTc from a 99Mo/99mTc generator. The daughter extraction was performed in an electrochemical cell by applying a constant potential of 5 V in sodium hydroxide electrolyte (pH ∼ 13). The electrolysis process lasted for approximately 1 hour. Hence, the 99mTc selectively accumulated on the platinum electrode (cathode). The 99mTc deposited was recovered in a 0.9% saline solution. Then, it was purified with the use of an alumina column (Chakravarty et al., 2010a).