Abstract

This work investigated the photochemical degradation of malachite green (MG), a cationic triphenylmethane dye used as a coloring agent, fungicide, and antiseptic. UV photolysis was ineffective in the removal of MG as only 12.35% degradation of MG (10 mg/L) was achieved after 60 min of irradiation. In contrast, 100.00% degradation of MG (10 mg/L) was observed after 60 min of irradiation in the presence of 10 mM H2O2 by UV/H2O2 at pH 6.0. Similarly, complete removal (100.00%) of MG was observed at 30 min of the reaction time by UV/H2O2/Fe2+ employing [MG]0 = 10 mg/L, [H2O2]0 = 10 mM, [Fe2+]0 = 2.5 mg/L, and [pH]0 = 3.0. For the UV/H2O2 process, the degradation efficiency was higher at pH 6.0 than at pH 3.0 as the kobs values were 0.0873 and 0.0690 min−1, respectively. However, UV/H2O2/Fe2+ showed higher reactivity at pH 3.0 than at pH 6.0. Chloride and nitrate ions slightly inhibited the removal efficiency of MG by both UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes. Moreover, three degradation products (DPs) of MG, (i) 4-dimethylamino-benzophenone (DABP), (ii) 4-amino-benzophenone (ABP), and (iii) 4-dimethylamino-phenol (DAP), were identified by GC-MS during the UV/H2O2 treatment. These DPs were found to demonstrate higher aquatic toxicity than the parent MG, suggesting that researchers should focus on the removal of target pollutants as well as their DPs. Nevertheless, the results of this study indicate that both UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes could be implemented to alleviate the harmful environmental impacts of dye and textile industries.

1 Introduction

Synthetic dyes are primarily used in the textile, food, and cosmetics industries. These industries frequently discharge a large amount of untreated and partially treated dye effluents, leading to substantial environmental pollution (Slama et al., 2021). These dyes pose significant harm to human beings and other ecosystems. According to available literature, certain synthetic dyes exhibit toxic properties such as dermatologic effects, allergenic, and carcinogenic (Arora, 2014; Tkaczyk et al., 2020). These dyes constitute the largest category of all colorants, with more than 100,000 varieties available commercially worldwide. The global production of synthetic dyes exceeds 1 million tons annually (Tkaczyk et al., 2020). The extensive use of dyes across various fields greatly impacts water sources (Slama et al., 2021; Tkaczyk et al., 2020; Lal et al., 2024). Synthetic dyes are extensively used in the textile, leather, printing, and paper industries, with certain varieties also being applied in the pharmaceutical and cosmetics industries and in food production (Tkaczyk et al., 2020). The large-scale production of dyes and their broad range of applications lead to the generation of large volumes of colored wastewater and various types of post-production wastes. The textile industry accounts for a significant amount of dyes in aquatic environments, with dye losses during dyeing processes ranging from a minimum of 5% to as much as 50%, depending on the type of fabric and dye. As a result, approximately 200 billion liters of colored effluents are produced annually (Kant, 2012). Additionally, the discharge of textile chemicals raises concerns and presents scientific challenges (Kishor et al., 2021). Given their commercial value, the impacts and risks associated with these chemicals have been studied intensively (Katheresan et al., 2018).

Malachite green (MG), a synthetic dye, is commonly used in aquaculture, textile, and food product industries (Sharma et al., 2023). MG poses potential risks to aquatic life, human health, and the environment (Sharma et al., 2023; Gharavi-Nakhjavani et al., 2023). As a result, regulatory bodies worldwide have taken measures to restrict or ban its use (Gopinathan et al., 2015). Therefore, it is essential to efficiently eliminate synthetic organic dyes from (waste) water (Singh and Arora, 2011). In this regard, different methods have been explored. Several physical, biological, and chemical methods have been used for this purpose, including adhesion to substances, chemical precipitation, photochemical and/or chemical degradation (Khan I. et al., 2020), adsorption (Lanjwani et al., 2024), coagulation (Khan I. et al., 2020; Lanjwani et al., 2024), membrane processes (Oladoye et al., 2023), as well as microbial decolorization (Alsukaibi, 2022) or biological degradation (Thao et al., 2023). Traditional methods were insufficient to treat wastewater containing these stable toxins. However, some methods are very effective in the removal/degradation of toxic environmental pollutants (Sivaraman et al., 2022; Mishra et al., 2019), among which advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) are predominant (Garrido-Cardenas et al., 2020; Fast et al., 2017).

AOPs use highly reactive oxidizing species such as •OH and SO4•‒ to remove organic pollutants from water bodies (Khan et al., 2013; Islam et al., 2023; Hu et al., 2022; Sepúlveda et al., 2024). AOPs have the advantages of being environmentally friendly, achieving complete degradation of pollutants (Fast et al., 2017), and being relatively low cost compared to other methods. Additionally, AOPs can be applied on-site, minimizing the need to transport and treat effluents. Different oxidants such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), peroxymonosulfate (HSO5−), and persulfate (S2O82‒) are generally used in AOPs as sources of reactive radicals. Among different AOPs, UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes are commonly used as (waste)water treatment processes (Khan et al., 2014). Both UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes are based on the formation of highly reactive and non-selective hydroxyl radicals (•OH). The hydroxyl radical (•OH) possesses a standard redox potential (Eo) of +2.80 V versus the normal hydrogen electrode (NHE). It exhibits a short lifetime (t1/2 < 1 μs) and high reactivity, making it a powerful oxidant. Moreover, the reactivity of hydroxyl radical is pH-dependent and has a typical reaction rate of 106 to 1011 M−1 s−1 with organic compounds. Notably, •OH reacts in a non-selective manner, engaging in various reactions including electron transfer, addition, and abstraction of hydrogen, impacting their reactivity and potential applications in pollutant removal and environmental remediation (Oh et al., 2016).

This study explores the efficacy of MG degradation by UV, UV/H2O2, and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes. The effect of different H2O2, MG, and Fe2+ concentrations and pH conditions on the removal efficiency of MG was evaluated. Moreover, the impact of nitrate and chloride ions was also investigated. In addition, the degradation products (DPs) of MG were identified, and potential degradation pathways were proposed. Finally, the toxicity of the identified DPs and MG was determined using the Ecological Structure Activity Relationship (ECOSAR) Program.

2 Experimental

2.1 Chemicals and reagents

Malachite green hydrochloride (C23H25N2Cl, molar mass = 364.911 g/mol), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37.0%), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 95.0%–98.0%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, ≥97.0%), potassium chloride (KOH, ≥85.0%), and sodium nitrate (NaNO3, ≥99.0%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30% v/v) and ferrous sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4.7H2O) were supplied by Merck.

2.2 Experimental procedures

Experiments were conducted in a photo-reactor consisting of a 100-mL beaker, kept on a magnetic stirrer to continuously mix the reaction solution. The radiation source was a 35-Watt UV lamp (UV-C, wavelength 254 nm, manufactured by Philips, Holland). The concentration of MG in the irradiated solutions was 10 mg/L, if not stated otherwise. Samples of 5 mL from the irradiated solutions were collected at specific time intervals for analysis. Whenever needed, the pH was adjusted with HCl and NaOH.

2.3 Analytical methods

A UV–Vis spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer) was used to measure the MG concentration in the treated solutions. The absorbance was recorded at 617 nm. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS, Agilent Technologies, 6890 Series) was used to identify the DPs of MG. In GC-MS, the separation was carried out with an HP-5MS capillary column (30 m, 0.25 mm I.D., 0.25 μm). The oven temperature was programmed as follows: 100°C (1 min) to 180°C at a rate of 20°C min‒1 (3 min) and finally set to 250°C at a rate of 10°C min‒1 (2 min). The temperatures of the injector and MS detector were set at 250°C and 280°C, respectively. The carrier gas was helium (flow rate = 1.0 mL min−1). The MS was applied in the EI mode at 70 eV. The DPs were determined at full scan mode ranging from 50 to 550 amu.

Equation 1 was used to determine the degrading efficiency of MG.where C0 represents the starting concentration of MG and Ct represents the MG concentration at time t.

2.4 Frontier electron densities and point charge calculations

To find the reactive sites/centers in the MG molecule where •OH can preferentially attack, the frontier electron densities (FEDs) of the molecular orbitals of MG and point charges of the C and N atoms were calculated using the Gaussian 09 program (An et al., 2015; Rehman et al., 2018). FED calculations were performed for both the highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMOs) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (LUMOs). Initially, the geometry of MG was optimized using the HF/3–21 g basis set. Thereafter, the energy calculations for FEDs and point charge determination were performed using the hybrid density functional B3LYP method of the density functional theory (DFT) with the 6–311 g basis set (B3LYP/6–311 g).

2.5 Determination of aquatic toxicity

The Ecological Structure Activity Relationship (ECOSAR) program (ECOSAR, 2014) was used to evaluate the acute and chronic toxicities of MG and its DPs. The ECOSAR is an effective tool for predicting the aquatic toxicity of toxic pollutants (Ali et al., 2018). This program evaluates the acute and chronic toxicities of toxic compounds toward fish, daphnia, and green algae. Acute toxicity is evaluated in terms of the LC50 and EC50. LC50 is the toxicant concentration which could cause the death of 50% fish and 50% daphnia after 96 and 48 h of exposure, respectively. EC50 is the concentration of the toxicant responsible for 50% growth inhibition of green algae after 96 h of exposure.

3 Result and discussion

3.1 Direct photolysis of MG

Before investigating the efficiencies of UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes for the degradation of MG, it was studied by direct photolysis (UV only) employing UV-C (254 nm) light. The 254-nm UV-C light photons do not have sufficient amount of energy to directly split water molecules into reactive species, i.e., hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and hydrated electrons (e−aq), because only radiation with λ < 190 nm can split water to produce •OH and e−aq (Gonzalez et al., 2004; Imoberdorf and Mohseni, 2011). Therefore, any degradation of MG at 254 nm radiation can only be attributed to the formation of its excited-state species (MG*) upon absorption of 254 nm photons (reaction (Equation 2)) (Khan et al., 2014). The excited-state molecules can either undergo direct degradation (reaction (Equation 3)) or may lead to the formation of reactive oxygen species (singlet oxygen, 1O2) (reaction (Equation 4)) which then attack the MG molecules and cause their degradation (reaction (Equation 5)) (Chen et al., 2008).

In this study, only 12.35% degradation of MG (10 mg/L) was achieved by direct photolysis at pH 6.0 after 60 min of irradiation. At pH 3.0 and 11.0, a slight decrease in degradation from 12.35% to 10.04% and 11.27%, respectively, was observed. The observed pseudo-first-order rate constant (kobs) was 0.0027, 0.0024, and 0.0022 min−1 at pH 6.0, 3.0, and 11.0, respectively. These results suggest that direct photolysis is not an effective method for the removal of MG from water (Figure 1). These results are in agreement with findings of Modirshahla and Behnajady (2006). Therefore, UV-C was accompanied by H2O2 and H2O2/Fe2+ in the following experiments for efficient degradation of MG.

FIGURE 1

Effect of pH on % degradation of MG by direct photolysis. [MG]0 = 10 mg/L.

3.2 Degradation of MG by UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes

3.2.1 Effect of the initial H2O2 concentration

Both UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes are called hydroxyl radical-based AOPs since they result in the formation of •OH, as shown in (Equations 6–9) (Khan et al., 2013; Khan et al., 2017; Shah et al., 2015; Jiad and Abbar, 2023).

The reaction (Equation 9) regenerates ferrous ions (catalyst) during the treatment process and thus helps in continuous production of •OH in the reaction mixture, thereby degrading the target pollutants until their complete mineralization, as long as the source of •OH (i.e., H2O2) is available in the solution.

In the present study, four different concentrations of H2O2, i.e., 2, 5, 10, and 20 mM, were tested for their ability to degrade MG by the UV/H2O2 process at pH 6.0 using 10 mg/L MG. The results are depicted in Figure 2. It was observed that a combination of H2O2 with UV has significantly improved the degradation of MG compared to direct photolysis. The degradation of MG was found to be 78.5, 87.8 and 100% at 60 min in presence of 2, 5 and 10 mM H2O2, respectively, compared to 12.35% in direct photolysis. This increase in % degradation was due to the generation of •OH in the UV/H2O2 process (reaction (Equation 6)). Since •OH radicals are highly reactive and non-selective species, they reacted fast with MG, resulting in its degradation. As the concentration of H2O2 increases in the reaction solution, a larger pool of •OH is expected to be produced, thereby enhancing the degradation process. However, a further increase in H2O2 concentration to 20 mM was found to have a detrimental effect on the degradation efficiency as only 94.9% degradation of MG was observed at the H2O2 concentration of 20 mM. The negative impact of higher H2O2 concentration on the degradation efficiency of MG was due to the scavenging effect of H2O2 for •OH (Equation 10) (Khan et al., 2013; Modirshahla and Behnajady, 2006; Khan J. A. et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2020; Rauf et al., 2016). Since this scavenging effect is predominant at higher H2O2 concentration, a relatively lesser degradation of MG was observed at higher H2O2 concentration (20 mM) than the optimum value (10 mM). The HO2• has been reported to be less reactive as compared to •OH and hence do not contribute much toward MG degradation (Modirshahla and Behnajady, 2006; Hameed and Lee, 2009). The kobs was calculated to be 0.0271, 0.0355, 0.0873, and 0.0529 min−1 at 2.0, 5.0, 10.0, and 20.0 mM H2O2, respectively. Therefore, it is crucial to optimize the H2O2 concentration to achieve the best result in pollutant removal in H2O2-assisted AOPs.

FIGURE 2

Effect of H2O2 concentration on % degradation of MG in the UV/H2O2 process. [H2O2]0 = 2 mM, 5 mM, 10 mM, and 20 mM, [MG]0 = 10 mg/L.

In case of UV/H2O2/Fe2+, the same initial concentrations of H2O2 were studied as in the case of the UV/H2O2 process, i.e., 2, 5, 10, and 20 mM. The initial concentration of MG was 10 mg/L, that of Fe2+ was 2.5 mg/L, and the pH was 3.0. The purpose of acidic pH, i.e., pH 3, was to keep the photo-Fenton system highly efficient as the catalytic activity of Fe2+ for H2O2 activation has been found to be the highest at acidic pH values (Khan et al., 2013; Hameed and Lee, 2009; Nasuha et al., 2021). At an initial H2O2 concentration of 2, 5, 10, and 20 mM, the degradation efficiency was found to be 71.21, 83.31, 95.61%, and 84.77%, respectively, at 20 min (Figure 3). Similarly, the kobs values at 2, 5, 10, and 20 mM H2O2 were found to be 0.0695, 0.0957, 0.1499, and 0.1014 min‒1, respectively. This trend is similar to that found in the UV/H2O2 process. Thus, it can be suggested that the role of H2O2 is similar in both UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes, i.e., initially increasing the level of •OH up to a certain optimum concentration of H2O2 (10 mM in this case) through reactions Equations 6–9 and then decreasing the level of •OH via the scavenging process (reaction (Equation 10)).

FIGURE 3

Effect of H2O2 concentration on the UV/H2O2/Fe2+ process. [Fe2+]0 = 2.5 mg/L, [MG]0 = 10 mg/L, [H2O2]0 = 2, 5, 10, and 20 mM, pH 3.0. The inset indicates the kobs values at studied H2O2 concentrations.

3.2.2 Effect of initial MG concentration

To analyze how varying concentrations of MG influence its degradation efficiency by UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes, a series of experiments were conducted at initial concentration of 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 mg/L of [MG]0. For the UV/H2O2 process, the degradation efficiency was 100.00, 96.98, 84.91%, and 69.43% at 20 min of reaction time when [MG]0 = 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 mg/L of MG, respectively, while applying [H2O2]0 = 10 mM and pH = 6.0 (Figure 4). The degradation of MG followed pseudo-first-order kinetics, with the observed pseudo-first-order rate constant (kobs) of 0.1541, 0.1274, 0.0873, and 0.0524 min−1 at [MG]0 = 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 mg/L, respectively.

FIGURE 4

Effect of MG concentration on % degradation of malachite green in the UV/H2O2 process. [H2O2]0 = 10 mM, [MG]0 = 2.5 mg/L, 5 mg/L, 10 mg/L, and 20 mg/L. The inset indicates the kobs values at different MG concentrations.

For the UV/H2O2/Fe2+ process, the degradation efficiency was 100, 89.92, 77.99, and 69.49% at 10 min of treatment when the initial MG concentration was 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 mg/L, respectively (Figure 5), employing [Fe2+]0 = 2.5 mg/L, [H2O2]0 = 10 mM, and pH = 3.0. The kobs values were found to be 0.3884, 0.2333, 0.1565, and 0.1180 min‒1 for [MG]0 = 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 mg/L, respectively.

FIGURE 5

Effect of MG concentration on the UV/H2O2/Fe2+ process. [Fe2+]0 = 2.5 mg/L, [MG]0 = 2.5 mg/L, 5 mg/L, 10 mg/L, and 20 mg/L, [H2O2]0 = 10 mM, pH 3.0. The inset indicates the kobs values at different MG concentrations.

These results clearly indicated that as the concentration of MG increases, the degradation efficiency decreases for both of the UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes. Since both these processes rely on the same reactive species, i.e., •OH, and the source of •OH (i.e., H2O2) is also the same in both processes, the reasons for the reduced degradation efficiency at higher MG concentration are also the same. The reduced degradation efficiency at a higher dye concentration is the solution’s elevated absorbance. This is particularly relevant because MG has a significant absorbance below 300 nm, which is the same range where H2O2 absorbs (Navarro et al., 2019). It means that the color produced by the MG dye acts as a filter for UV light and thereby reduces the penetration of light into the reaction mixture. As a result, at higher MG concentration, fewer photons are available to interact with the H2O2 molecule. Consequently, there will be lesser production of hydroxyl radicals, which are responsible for the degradation of dye molecules. By the same reason, the rate of regeneration of catalyst (Fe2+) via reaction (9) also decreases at higher MG concentration. Consequently, the rate of H2O2 activation by Fe2+ to produce •OH via reaction (7) also decreases at higher MG concentration. Thus, the filter out of the UV light by the dye color resulted in reduced •OH formation, which ultimately led to the lower degradation efficiency of MG in both UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes at higher MG concentration. Another possible reason of the lower degradation efficiency at higher MG concentration is the enhanced level of intermediate (degradation products of MG) molecules produced at higher MG concentration. As a result, the competition between MG and intermediate molecules for •OH increases, and there are greater chances for •OH to react with intermediate molecules rather than MG molecules when the level of intermediate molecules enhances at higher MG concentration, which led to lower degradation efficiency of MG.

Though the % degradation decreases with increase in MG concentration, the rate of degradation (the number of molecules undergo degradation per unit time) increases with increase in MG concentration. At higher MG concentration, a higher number of the dye molecules are exposed to reactive radicals, and hence, the chances of collisions between •OH and MG molecules increase, which led to the higher degradation rate of MG (Khan et al., 2013; Rehman et al., 2018; Galindo et al., 2001). As a result, the rate of MG degradation was calculated to be 0.103, 0.217, 0.562, and 0.745 mg/L/min at 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 mg/L MG concentration, respectively, at 10 min of reaction time for the UV/H2O2 process. Similarly, for the UV/H2O2/Fe2+ process at 5 min of reaction time, the rate of degradation of MG was found to be 0.426, 0.770, 1.130, and 2.191 mg/L/min at 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 mg/L MG concentration, respectively.

Of note, % degradation is a relative term that refers to the number of molecules undergoing degradation related to the total number of molecules in the system. This relative quantity decreases with an increase in the target compound concentration. On the other hand, the rate of degradation is an absolute term which represents the actual number of molecules undergo degradation in the given specified time. It is not related to the total number of molecules. This absolute quantity increases with an increase in the target compound concentration.

3.2.3 Effect of Fe2+ concentration on MG degradation by the UV/H2O2/Fe2+ process

To investigate the effect of different concentrations of Fe2+ on the degradation of MG by the UV/H2O2/Fe2+ process, a series of experiments were conducted using different initial concentrations of Fe2+ (i.e., 0.5, 1, 2.5, and 5 mg/L). Other conditions were kept constant at [H2O2]0 = 10 mM, [MG]0 = 10 mg/L, and pH = 3.0. The obtained results are depicted in Figure 6. The results indicated that the degradation efficiency increases with increasing the initial concentration of Fe2+ ([Fe2+]0). At [Fe2+]0 of 0.5, 1.0, 2.5, and 5.0 mg/L, the degradation efficiencies were 71.17, 80.25, 88.31, and 96.05% at 15 min, respectively. Similarly, the values of kobs were found to be 0.093, 0.113, 0.1565, and 0.2204 min−1 at [Fe2+]0 = 0.5, 1.0, 2.5, and 5.0 mg/L, respectively. The increase in degradation of MG with an increase in [Fe2+]0 is due to the presence of Fenton-like reaction (Equation 7). Fe2+ triggers the activation of H2O2, leading to the formation of •OH via an electron transfer process where electrons move from Fe2+ to H2O2 (De Laat and Gallard, 1999). Therefore, as the [Fe2+]0 increases, the rate of •OH formation increases, which subsequently led to higher degradation efficiency of MG.

FIGURE 6

Effect of Fe2+ concentration on % degradation of MG in the UV/H2O2/Fe2+ process. [MG]0 = 10 mg/L, [H2O2]0 = 10 mM, pH 3.0. The inset indicates the relationship between kobs and Fe2+ concentration.

Further insight into the relationship between kobs and [Fe2+]0 showed that the increase in kobs with increase in [Fe2+]0 is not linear (Figure 6 inset). This non-linear relation is due to the •OH scavenging effect of Fe2+ at a substantially higher concentration (Equation 11) (Hameed and Lee, 2009; Chen and Pignatello, 1997; Joseph et al., 2000).

3.2.4 Effect of pH

pH is a crucial factor that significantly impacts the effectiveness of AOPs by influencing the generation of •OH and is consistently taken into account for the optimization of water treatment processes. To study the effect of pH on the degradation of MG by UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes and determine the optimal pH of the reaction mixture, experiments were carried out at pH = 3.0 and 6.0. For UV/H2O2, the concentrations of MG and H2O2 were kept constant at 10 mg/L and 10 mM, respectively. For UV/H2O2/Fe2+, the same concentrations of MG and H2O2 were used in addition to [Fe2+]0 = 2.5 mg/L. The results indicated that the degradation of MG was influenced by the pH of the solution (Figure 7). For the UV/H2O2 process, the degradation efficiency was higher at pH 6.0 compared to pH 3.0. Specifically, 91.82% MG degradation was observed at pH 6.0 compared to 84.35% at pH 3.0 after 30 min of irradiation. The kobs value decreased from 0.0873 to 0.0690 min‒1 as the pH changed from 6.0 to 3.0 (Figure 7A). However, 100% degradation of MG was achieved after 60 min of treatment at both pH 3.0 and 6.0. Hence, the UV/H2O2 process shows higher degradation efficiency at pH 6.0 as compared to acidic pH. Iron-based processes such as Fenton and photo-Fenton are AOPs that demonstrate a strong pH dependence where acidity has been found as a favorable condition for the degradation of target compounds (Khan et al., 2013; Chan and Chu, 2003; Yong et al., 2015). Unlike the UV/H2O2 process, UV/H2O2/Fe2+ showed higher removal efficiency at pH 3.0 than at pH 6.0. The degradation of MG was found to be 100.00% and 96.67% after 30 min of treatment at pH 3.0 and pH 6.0, corresponding to kobs of 0.1565 and 0.1135 min‒1, respectively (Figure 7B). A comparable pattern was noticed by Hassan et al. (2023) and Khan et al. (2013). Fe2+ has been found to have higher catalytic activity at acidic conditions for H2O2 activation to generate •OH (Equation 7) (Khan et al., 2013; Chan and Chu, 2003). As the pH increases, iron undergoes precipitation in the form of Fe(OH)3 and hence, Fe2+ was not available to activate H2O2 for •OH generation, thereby hindering the degradation efficiency of MG at pH 6.0 (Deb et al., 2023).

FIGURE 7

Effect of pH on % degradation and kobs of MG by UV/H2O2(A) and UV/H2O2/Fe2+(B). Experimental conditions: [MG]0 = 10 mg/L, [H2O2]0 = 10 mM, and [Fe2+]0 = 2.5 mg/L.

To better understand the efficiencies of the AOPs studied in this work in comparison with the similar AOPs reported previously on the degradation of MG, please refer to Table 1. Moreover, Table 2 summarizes the comparison of the efficiencies of different AOPs applied for the treatment of MG. Both these tables provide important information for enriching the existing knowledge on the removal of dyes by various AOPs.

TABLE 1

| Method | Concentration of malachite green (mg/L) | [H2O2]0 | [Fe2+]0 | pH | Time (min) | Degradation (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV/H2O2 | 10 | 10 mM | ---- | 6.0 | 60 | 100 | This study |

| UV/H2O2/Fe2+ | 10 | 10 mM | 2.5 mg/L | 3.0 | 30 | 100 | This study |

| UV/H2O2 | 10 | 300 mg/L | ---- | ---- | ≈25–30 | 100 | Modirshahla and Behnajady (2006) |

| UV/H2O2 | 25 | 1.5 mL of 33% H2O2/250 mL | ---- | 5.6 | 50 | 96 | Dar et al. (2023) |

| UV/H2O2/Fe2+ | 25 | 1.5 mL of 33% H2O2/250 mL | ---- | ---- | 40 | 100 | Dar et al. (2023) |

| UV/H2O2 | 100 | 12 mM | ---- | 3.0 | 60 | 95 | Ghime et al. (2019) |

| UV/H2O2/Fe2+ | 100 | 12 mM | 60 ppm | 3.0 | 60 | 98 | Ghime et al. (2019) |

Comparison of MG removal by UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes studied in this work and those reported by other researchers.

TABLE 2

| Method | Malachite green (mg/L) | Experimental condition | Time (min) | Degradation (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV/H2O2 | 10 | 10 mM H2O2, pH 6.0 | 60 | 100 | This study |

| UV/H2O2/Fe2+ | 10 | 10 mM H2O2, 2.5 mg/L Fe2+, pH 3.0 | 100 | This study | |

| TiO2 photocatalysis | 100 | 0.6 g/L TiO2, UV light (32-W lamp) | 60 | 95 | Ghime et al. (2019) |

| TiO2 photocatalysis | 10 | 0.5 g/L TiO2, UV-A light (9 W lamp) | 40 | 100 | Berberidou et al. (2007) |

| Sonolysis (under argon) | 10 | 135 W ultrasound power, argon atmosphere | 120 | 100 | Berberidou et al. (2007) |

| Chemical oxidation with ozone (O3) | 36.49 | Ozone (0.5 g/h), pH 3.0, 5.0, and 7.0 | 110 | 96.74 at pH 3.0, 80.5 at pH 5.0, and 50.1 at pH 7.0 | Mirila et al. (2018) |

| Electrochemical oxidation | 20 | I = 32 mA.cm−2, pH = 3, [Na2SO4] = 0.1 mol/L, boron-doped diamond (BDD) | 60 | 98 | Guenfoud et al. (2014) |

| Kissiris/Fe3O4/TiO2 with the glucose oxidase (GOx) enzyme | 20 | Initial glucose concentration = 20 mM, pH 5.5, temp. = 40°C, catalyst = 2 g | 120 | 99 | Elhami et al. (2015) |

Comparison of different AOPs for the degradation of malachite green.

3.2.5 Effect of chloride and nitrate ions

To investigate the effect of common inorganic ions on the degradation efficiency of MG by UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes, the degradation of MG was studied in the presence of chloride (Cl−) and nitrate ions (NO3−)- used as representative inorganic ions. It was found that both Cl− and NO3− slightly reduced the degradation efficiency of MG (Table 3). For the UV/H2O2 process, the degradation of MG decreased from 100.0% to 84.1% and 91.95% at 60 min of treatment in the presence of 5 mM each of Cl− and NO3−, respectively, employing [MG]0 = 10 mg/L [H2O2]0 = 10 mM, and [pH]0 = 6. The kobs was found to be 0.0873, 0.0415, and 0.0502 min‒1 in the presence of no scavenger, Cl−, and NO3−, respectively (Table 3). Similarly, for the UV/H2O2/Fe2+ process, the degradation of MG decreased from 96.0% to 78.2% and 85.5% at 20 min of treatment in the presence of 5 mM each of Cl− and NO3−, respectively, employing [MG]0 = 10 mg/L, [H2O2]0 = 10 mM, [Fe2+]0 = 2.5 mg/L, and [pH]0 = 3. The kobs of MG by UV/H2O2/Fe2+ was found to be 0.1565, 0.0817, and 0.1016 min‒1 in the presence of no scavenger, Cl−, and NO3−, respectively (Table 3).

TABLE 3

| Anion | UV/H2O2 | UV/H2O2/Fe2+ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % degradation at 60 min of treatment | k obs (min‒1) | % degradation at 20 min of treatment | k obs (min‒1) | |

| No scavenger | 100.00 | 0.0873 | 96.00 | 0.1565 |

| Chloride ion (5 mM) | 84.10 | 0.0415 | 78.18 | 0.0817 |

| Nitrate ion (5 mM) | 91.95 | 0.0502 | 85.46 | 0.1016 |

Effect of chloride and nitrate ions on % degradation and kobs of MG by UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes. Experimental conditions: [MG]0 = 10 mg/L, [H2O2]0 = 10 mM, [Fe2+]0 = 2.5 mg/L. pH was 6.0 for UV/H2O2 and 3.0 for UV/H2O2/Fe2+.

The reduction in the degradation efficiency of MG by Cl− in both processes, i.e., UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+, could possibly be attributed to the scavenging effect of Cl− for •OH. This is because the main reactive species in both of these processes is •OH, as confirmed by the methanol scavenging test (data not shown). Chloride ions quench •OH effectively in accordance of reactions Equation 12, 13 (Muruganandham and Swaminathan, 2004; Alshamsi et al., 2007).

The slight decrease in the removal efficiency of MG by Cl− may possibly be due to the reversibility of reaction Equation 12, which re-produces the •OH via backward reaction with a little higher rate constant (kb) than its scavenging via forward reaction (kf). Moreover, the presence of Fe2+ in UV/H2O2/Fe2+, could also potentially contribute to the lower removal efficiency of MG by Cl− (reaction (Equation 14)) (Ali et al., 2018; Malik and Saha, 2003).

Nitrate ions (NO3−) were found to have a less retarding effect than Cl− on the degradation of MG by both UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes. This could possibly be due to the low reactivity of NO3− with •OH (Rehman et al., 2018).

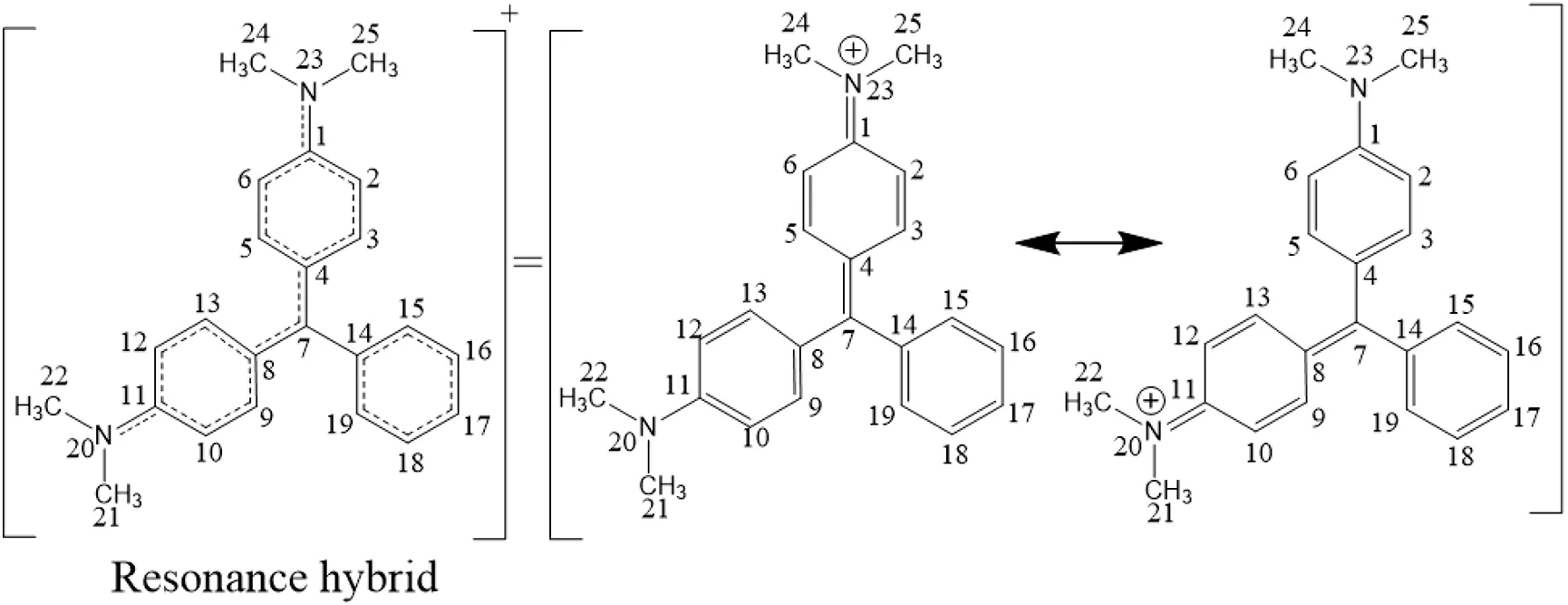

3.3 Identification of degradation products and possible degradation pathways

The DPs of MG produced during UV/H2O2 treatment were identified by GC-MS. Prior to discussing the experimentally detected DPs of MG, it is highly useful to find the potential reactive sites of MG where •OH could initially attack via addition or hydrogen abstraction reactions. For this purpose, the density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the HF/3–21 g basis set for optimization and B3LYP/6–311 g basis set for energy calculations. The DFT calculations were performed using the Gaussian 09 program to find out the FEDs and point charges of the MG atoms to predict the positions in the MG molecule where •OH can easily undergo addition or hydrogen abstraction reactions. The calculated values of FEDs and point charges of the MG are given in Table 4. It has been reported that atoms having larger values of (FED2HOMO + FED2LUMO) are more likely to be attacked by the •OH via addition reaction/pathway (An et al., 2015). On the other hand, •OH could preferably abstract hydrogen from atoms having more positive charge. Based on this information, the •OH could initially react with C7 atom via the addition reaction due to its large (FED2HOMO + FED2LUMO) value (An et al., 2015; Rehman et al., 2018). The next preferable sites of •OH addition reactions could be the N20 and N23 atoms followed by the C4 and C8 atoms. The highest point charge values are possessed by C1 and C11 atoms due to their attachment with the electronegative N atoms. However, both of these C atoms bear no hydrogen atom to be abstracted by •OH. Similarly, the carbon atoms bearing the next higher value of point charge, i.e., C7, also lack hydrogen atoms to be abstracted by •OH. The same is the case with C14, which has the next higher value of point charge. Therefore, the possible hydrogen abstraction sites are proposed to be C3 and C9 as well as C5 and C13, which have the lowest negative values (i.e., relatively large values) of point charge among the atoms bearing hydrogen atoms.

TABLE 4

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atom | FED2HOMO + FED2LUMO | Point charge | Atom | FED2HOMO + FED2LUMO | Point charge |

| C1 | 0.0590 | 0.23732 | C14 | 0.0236 | −0.09591 |

| C2 | 0.0452 | −0.25008 | C15 | 0.0408 | −0.16964 |

| C3 | 0.0578 | −0.12135 | C16 | 0.0066 | −0.18682 |

| C4 | 0.0774 | −0.13303 | C17 | 0.0288 | −0.15825 |

| C5 | 0.0567 | −0.12959 | C18 | 0.0066 | −0.18681 |

| C6 | 0.0480 | −0.25203 | C19 | 0.0408 | −0.16964 |

| C7 | 0.2168 | 0.15527 | N20 | 0.1724 | −0.36351 |

| C8 | 0.0774 | −0.13303 | C21 | 0.0019 | −0.36622 |

| C9 | 0.0578 | −0.12135 | C22 | 0.0019 | −0.36616 |

| C10 | 0.0452 | −0.25008 | N23 | 0.1723 | −0.36351 |

| C11 | 0.0590 | 0.23732 | C24 | 0.0019 | −0.36616 |

| C12 | 0.0479 | −0.25203 | C25 | 0.0019 | −0.36622 |

| C13 | 0.0567 | −0.12960 | |||

Frontier electron densities and point charges of MG atoms calculated by the Gaussian 09 program.

In the present work, three DPs of MG were identified, namely: (a) 4-dimethylamino-benzophenone (DABP), (b) 4-amino-benzophenone (ABP), and (c) 4-dimethylamino-phenol (DAP) (Scheme 1). The hydroxyl radical could possibly attack the central carbon atom of MG, leading to the formation of a hydroxylated reactive cationic radical (MG-OH)—not detected in the present study but is supposed to be a tentative degradation product based on the DFT calculations (Berberidou et al., 2007). The subsequent demethylation and further oxidation by •OH finally led to the formation of DAP and DABP (Berberidou et al., 2007). The demethylation of DABP—a common reaction of MG—could then lead to the formation of ABP (Berberidou et al., 2007). The mentioned three DPs have also been detected by other researchers while studying the degradation of MG by AOPs (Berberidou et al., 2007; Milano et al., 1995; Xie et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2002; Ju et al., 2009). Moreover, it has been previously reported that the cleavage of benzophenone generally leads to the formation of benzene and benzaldehyde (Berberidou et al., 2007). The formation of amino-benzene from MG and then its conversion to nitro-benzene by •OH have also been reported (Berberidou et al., 2007). The attack of •OH on lower-molecular weight aromatic DPs such as amino-benzene, nitro-benzene, benzaldehyde, and benzene further leads to the formation of lower-molecular weight organic acids, which subsequently lead to the formation of CO2, H2O, nitrate, nitrite, and/or ammonium ions (Xie et al., 2001; Ju et al., 2009). The present study suggests that treatment of MG-containing water by HR-AOPs not only leads to its complete degradation but also leads to its complete mineralization—albeit slowly.

Scheme 1

Proposed degradation mechanism of malachite green by the UV/H2O2 process.

3.4 Toxicity evaluation

The ultimate goal of a water treatment technology is to achieve clean and pure water, i.e., toxicant-free water. To check whether the toxicity of the treating mixture reduces during the degradation of MG or not, the aquatic toxicity of the detected DPs toward fish, daphnia, and green algae was determined using the ECOSAR program (Rehman et al., 2023; Iqbal et al., 2024a; Iqbal et al., 2024b; Khan et al., 2023) (Table 5). Surprisingly, all the three detected DPs were found to have higher toxicity (both acute and chronic) than the parent MG. Therefore, it can be concluded that the researchers should not just focus on the removal of target compound while dealing with the removal of dyes. Rather, the toxicity of the treated solution should be determined before, during, and after the treatment in order to ensure the reduction in toxicity of the treated solution. Moreover, the treatment time should be prolonged such that the treatment technology not only degrades/removes the target pollutant but also the DPs, i.e., until complete mineralization is achieved.

TABLE 5

| Compound | Acute toxicity | Chronic toxicity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish (LC50) | Daphnia (LC50) | Green algae (EC50) | Fish (ChV) | Daphnia (ChV) | Green algae (ChV) | |

| MG | 3,230 | 1,640 | 774 | 277 | 118 | 158 |

| DABP | 12.0 | 7.67 | 9.48 | 1.35 | 1.05 | 3.26 |

| ABP | 15.1 | 1.79 | 4.48 | 0.138 | 0.022 | 1.11 |

| DAP | 442 | 236 | 137 | 40.2 | 19.4 | 31.2 |

Aquatic toxicity of malachite green and its identified DPs (unit = mg L−1).

4 Conclusion

The present study investigated the degradation of MG by UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes. MG was found to be resistant toward direct photolysis as only 12.35% MG degradation was achieved by direct photolysis at pH 6.0 after 60 min of treatment. However, the combination of H2O2 with UV light accelerated the degradation of MG, achieving 100% degradation of MG at 10 mM H2O2 concentration when treated for 60 min, suggesting the higher reactivity of MG with •OH. Further enhancement in the degradation efficiency of MG by UV/H2O2 was observed by adding Fe2+ ion—an effective catalyst for H2O2 activation—as 100% degradation of MG was observed at [Fe2+]0 = 2.5 mg/L and 30 min of treatment. The higher concentration of MG was found to have a detrimental effect on its degradation by both UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes. However, increasing concentrations of H2O2 and Fe2+ were found to have a positive effect on MG degradation. For the UV/H2O2 process, a higher removal efficiency of MG was observed at pH 6.0 as compared to at pH 3.0. Nitrate (NO3−) and chloride ions (Cl−) have negatively impacted the MG degradation by both UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes. However, NO3− showed less retarding effect than Cl−, possibly due to the lower reactivity of NO3− with •OH than that of Cl−. Based on the GC-MS analysis, three degradation products (DPs) of MG were identified, namely: (a) 4-dimethylamino-benzophenone (DABP), (b) 4-amino-benzophenone (ABP), and (c) 4-dimethylamino-phenol (DAP). The computational aquatic toxicity study toward three aquatic organisms (fish, daphnia, and green algae) showed that all of the detected DPs are more toxic than MG. The present study revealed that MG can effectively be degraded by hydroxyl radical-based AOPs; however, researchers should also ensure the complete removal of its DPs so that the toxicity of the treated water may not increase due to the formation of toxic DPs.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

SW: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing–original draft. PF: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, and writing–original draft. JK: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, supervision, and writing–review and editing. AZ: software, validation, and writing–review and editing. MA: conceptualization and writing–review and editing. AA-A: funding acquisition, validation, and writing–review and editing. NS: conceptualization and writing–review and editing. CH: software, validation, and writing–review and editing. MA: conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, validation, and writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors highly acknowledge the financial support from Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, Pakistan, through Research Innovation Fund (RIF). CH acknowledges the support of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (Nos. 2021R1A2C1093183 and 2021R1A4A1032746). The authors also gratefully acknowledge the Researchers Supporting Project (number RSPD2024R534), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgments

The authors highly acknowledge the financial support from Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, Pakistan, through Research Innovation Fund (RIF). CH acknowledges the support of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (Nos. 2021R1A2C1093183 and 2021R1A4A1032746). The authors also gratefully acknowledge the Researchers Supporting Project (number RSPD2024R534), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Ali F. Khan J. A. Shah N. S. Sayed M. Khan H. M. (2018). Carbamazepine degradation by UV and UV-assisted AOPs: kinetics, mechanism and toxicity investigations. Process Saf. Environ. Prot.117, 307–314. 10.1016/j.psep.2018.05.004

2

Alshamsi F. A. Albadwawi A. S. Alnuaimi M. M. Rauf M. A. Ashraf S. S. (2007). Comparative efficiencies of the degradation of Crystal Violet using UV/hydrogen peroxide and Fenton's reagent. Dyes Pigm74, 283–287. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2006.02.016

3

Alsukaibi A. K. (2022). Various approaches for the detoxification of toxic dyes in wastewater. Processes10 (10), 1968. 10.3390/pr10101968

4

An T. An J. Gao Y. Li G. Fang H. Song W. (2015). Photocatalytic degradation and mineralization mechanism and toxicity assessment of antivirus drug acyclovir: experimental and theoretical studies. Appl. Catal. B Environ.164, 279–287. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2014.09.009

5

Arora S. (2014). Textile dyes: it’s impact on environment and its treatment. J. Bioremed. Biodeg5 (3), 1. 10.4172/2155-6199.1000e146

6

Berberidou C. Poulios I. Xekoukoulotakis N. P. Mantzavinos D. (2007). Sonolytic, photocatalytic and sonophotocatalytic degradation of malachite green in aqueous solutions. Appl. Catal. B Environ.74, 63–72. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2007.01.013

7

Chan K. Chu W. (2003). Modeling the reaction kinetics of Fenton’s process on the removal of atrazine. Chemosphere51, 305–311. 10.1016/s0045-6535(02)00812-3

8

Chen F. He J. Zhao J. Yu J. C. (2002). Photo-Fenton degradation of malachite green catalyzed by aromatic compounds under visible light irradiation. New J. Chem.26, 336–341. 10.1039/b107404k

9

Chen R. Pignatello J. (1997). Role of quinone intermediates as electron shuttles in Fenton and photoassisted Fenton oxidations of aromatic compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol.31, 2399–2406. 10.1021/es9610646

10

Chen Y. Hu C. Qu J. Yang M. Chemistry P. A. (2008). Photodegradation of tetracycline and formation of reactive oxygen species in aqueous tetracycline solution under simulated sunlight irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem.197, 81–87. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2007.12.007

11

Dar A. Anwar J. Munir A. (2023). Photocatalytic degradation of malachite green dye with UV/H2O2 system in presence of transition metal ions. J. Chem. Soc. Pak.45 (6), 302. 10.52568/001284/jcsp/45.04.2023

12

Deb A. Rumky J. Sillanpää M. (2023). “Fenton, photo-Fenton, and electro-Fenton systems for micropollutant treatment processes,” in Advanced oxidation processes for micropollutant remediation. Editors KhalidM.ParkY.KarriR. R.WalvekarR. (Boca Raton, FL: CRC press, Taylor & Francis group), 157–185. 10.1201/9781003247913-8

13

De Laat J. Gallard H. (1999). Catalytic decomposition of hydrogen peroxide by Fe (III) in homogeneous aqueous solution: mechanism and kinetic modeling. Environ. Sci. Technol.33, 2726–2732. 10.1021/es981171v

14

Elhami V. Karimi A. Aghbolaghy M. (2015). Preparation of heterogeneous bio-Fenton catalyst for decolorization of Malachite Green. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. E.56, 154–159. 10.1016/j.jtice.2015.05.006

15

Fast S. A. Gude V. G. Truax D. D. Martin J. Magbanua B. S. (2017). A critical evaluation of advanced oxidation processes for emerging contaminants removal. Environ. Process.4, 283–302. 10.1007/s40710-017-0207-1

16

Galindo C. Jacques P. Kalt A. P A. (2001). Photochemical and photocatalytic degradation of an indigoid dye: a case study of acid blue 74 (AB74). J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem.141, 47–56. 10.1016/s1010-6030(01)00435-x

17

Garrido-Cardenas J. A. Esteban-García B. Agüera A. Sánchez-Pérez J. A. Manzano-Agugliaro F. (2020). Wastewater treatment by advanced oxidation process and their worldwide research trends. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health17 (1), 170. 10.3390/ijerph17010170

18

Gharavi-Nakhjavani M. S. Niazi A. Hosseini H. Aminzare M. Dizaji R. Tajdar-Oranj B. et al (2023). Malachite green and leucomalachite green in fish: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.30 (17), 48911–48927. 10.1007/s11356-023-26372-z

19

Ghime D. Goru P. Ojha S. Ghosh P. (2019). Oxidative decolorization of a malachite green oxalate dye through the photochemical advanced oxidation processes. Glob. Nest J.21 (2), 195. 10.30955/gnj.003000

20

Gonzalez M. G. Oliveros E. Wörner M. Braun A. M. (2004). Vacuum-ultraviolet photolysis of aqueous reaction systems. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C. Photochem. Rev.5, 225–246. 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2004.10.002

21

Gopinathan R. Kanhere J. Banerjee J. (2015). Effect of malachite green toxicity on non-target soil organisms. Chemosphere120, 637–644. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.09.043

22

Guenfoud F. Mokhtari M. Akrout H. (2014). Electrochemical degradation of malachite green with BDD electrodes: effect of electrochemical parameters. Diam. Relat. Mater.46, 8–14. 10.1016/j.diamond.2014.04.003

23

Hameed B. Lee T. (2009). Degradation of malachite green in aqueous solution by Fenton process. J. Hazard. Mater.164, 468–472. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.08.018

24

Hassan A. F. Mustafa A. Esmail G. Awad A. (2023). Adsorption and photo-fenton degradation of methylene blue using nanomagnetite/potassium carrageenan bio-composite beads. Arab. J. Sci. Eng.48, 353–373. 10.1007/s13369-022-07075-y

25

Hu J. Chen S. Liang X. (2022). Heterogeneous catalytic oxidation for the degradation of aniline in aqueous solution by persulfate activated with CuFe2O4/activated carbon catalyst. ChemistrySelect7, e202201241. 10.1002/slct.202201241

26

Imoberdorf G. Mohseni M. (2011). Degradation of natural organic matter in surface water using vacuum-UV irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater.186, 240–246. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.10.118

27

Iqbal J. Shah N. S. Ali Khan J. Ibrahim A. Masood Pirzada B. Naushad M. et al (2024a). Visible light driven ZnFe2O4 for the degradation of oxytetracycline in the presence of HSO5− at semi-pilot scale and additional H2 production. Chem. Eng. J.498, 155402. 10.1016/j.cej.2024.155402

28

Iqbal J. Shah N. S. Ali Khan J. Naushad M. Boczkaj G. Jamil F. et al (2024b). Pharmaceuticals wastewater treatment via different advanced oxidation processes: reaction mechanism, operational factors, toxicities, and cost evaluation – a review. Sep. Purif. Technol.347, 127458. 10.1016/j.seppur.2024.127458

29

Islam M. Kumar S. Saxena N. Nafees A. (2023). Photocatalytic degradation of dyes present in industrial effluents: a review. ChemistrySelect8, e202301048. 10.1002/slct.202301048

30

Jiad M. M. Abbar A. H. (2023). Efficient wastewater treatment in petroleum refineries: hybrid electro-Fenton and photocatalysis (UV/ZnO) process. Chem. Eng. Res. Des.200, 431–444. 10.1016/j.cherd.2023.10.050

31

Joseph J. M. Destaillats H. Hung H.-M. Hoffmann M. R. (2000). The sonochemical degradation of azobenzene and related azo dyes: rate enhancements via Fenton's reactions. J. Phys. Chem. A104, 301–307. 10.1021/jp992354m

32

Ju Y. Yang S. Ding Y. Sun C. Gu C. He Z. et al (2009). Microwave-enhanced H2O2-based process for treating aqueous malachite green solutions: intermediates and degradation mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater.171, 123–132. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.05.120

33

Kant R. (2012). Textile dyeing industry an environmental hazard. Nat. Sci.4 (1), 22–26. 10.4236/ns.2012.41004

34

Katheresan V. Kansedo J. Lau S. Y. (2018). Efficiency of various recent wastewater dye removal methods: a review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.6 (4), 4676–4697. 10.1016/j.jece.2018.06.060

35

Khan I. Saeed K. Ali N. Khan I. Zhang B. Sadiq M. (2020a). Heterogeneous photodegradation of industrial dyes: an insight to different mechanisms and rate affecting parameters. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.8 (5), 104364. 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104364

36

Khan J. A. He X. Khan H. M. Shah N. S. Dionysiou D. D. (2013). Oxidative degradation of atrazine in aqueous solution by UV/H2O2/Fe2+, UV/S2O82−/Fe2+ and UV/HSO5−/Fe2+ processes: a comparative study. Chem. Eng. J.218, 376–383. 10.1016/j.cej.2012.12.055

37

Khan J. A. He X. Shah N. S. Khan H. M. Hapeshi E. Fatta-Kassinos D. et al (2014). Kinetic and mechanism investigation on the photochemical degradation of atrazine with activated H2O2, S2O82− and HSO5−. Chem. Eng. J.252, 393–403. 10.1016/j.cej.2014.04.104

38

Khan J. A. He X. Shah N. S. Sayed M. Khan H. M. Dionysiou D. D. (2017). Degradation kinetics and mechanism of desethyl-atrazine and desisopropyl-atrazine in water with •OH and SO4•− based-AOPs. Chem. Eng. J.325, 485–494. 10.1016/j.cej.2017.05.011

39

Khan J. A. Sayed M. Shah N. S. Khan S. Khan A. A. Sultan M. et al (2023). Synthesis of N-doped TiO2 nanoparticles with enhanced photocatalytic activity for 2,4-dichlorophenol degradation and H2 production. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.11, 111308. 10.1016/j.jece.2023.111308

40

Khan J. A. Sayed M. Shah N. S. Khan S. Zhang Y. Boczkaj G. et al (2020b). Synthesis of eosin modified TiO2 film with co-exposed {001} and {101} facets for photocatalytic degradation of para-aminobenzoic acid and solar H2 production. Appl. Catal. B Environ.265, 118557. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118557

41

Kishor R. Purchase D. Saratale G. D. Saratale R. G. Ferreira L. F. R. Bilal M. et al (2021). Ecotoxicological and health concerns of persistent coloring pollutants of textile industry wastewater and treatment approaches for environmental safety. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.9 (2), 105012. 10.1016/j.jece.2020.105012

42

Lal R. Gour T. Dave N. Singh N. Yadav J. Khan A. et al (2024). Green route to fabrication of Semal-ZnO nanoparticles for efficient solar-driven catalysis of noxious dyes in diverse aquatic environments. Front. Chem.12, 1370667. 10.3389/fchem.2024.1370667

43

Lanjwani M. F. Tuzen M. Khuhawar M. Y. Saleh T. A. (2024). Trends in photocatalytic degradation of organic dye pollutants using nanoparticles: a review. Inorg. Chem. Commun.159, 111613. 10.1016/j.inoche.2023.111613

44

Malik P. K. Saha S. K. (2003). Oxidation of direct dyes with hydrogen peroxide using ferrous ion as catalyst. Sep. Purif. Technol.31, 241–250. 10.1016/s1383-5866(02)00200-9

45

Milano J. C. Loste-Berdot P. Vernet J. L. (1995). Photooxydation du Vert de Malachite en Milieu Aqueux en Presence de Peroxyde D'Hydrogene: Cinetique et Mecanisme Photooxidation of Malachite Green in Aqueous Medium in the Presence of Hydrogen Peroxide: Kinetic and Mechanism. Environ. Technol.16, 329–341. 10.1080/09593331608616275

46

Mirila D. C. Pîrvan M. Ș. Platon N. Georgescu A. M. Zichil V. Nistor I. D. (2018). Total mineralization of malachite green dye by advanced oxidation processes. Acta Chem. Iasi26, 263–280. 10.2478/achi-2018-0017

47

Mishra S. Chowdhary P. Bharagava R. N. (2019). “Conventional methods for the removal of industrial pollutants, their merits and demerits,” in Emerging and eco-friendly approaches for waste management. Editors BharagavaR. N.ChowdharyP. (Springer), 1–31.

48

Modirshahla N. Behnajady M. (2006). Photooxidative degradation of Malachite Green (MG) by UV/H2O2: influence of operational parameters and kinetic modeling. Dyes Pigm70, 54–59. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2005.04.012

49

Muruganandham M. Swaminathan M. (2004). Photochemical oxidation of reactive azo dye with UV-H2O2 process. Dyes Pigm62, 269–275. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2003.12.006

50

Nasuha N. Hameed B. Okoye P. (2021). Dark-Fenton oxidative degradation of methylene blue and acid blue 29 dyes using sulfuric acid-activated slag of the steel-making process. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.9, 104831. 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104831

51

Navarro P. Zapata J. P. Gotor G. Gonzalez-Olmos R. Gómez-López V. (2019). Degradation of malachite green by a pulsed light/H2O2 process. Water Sci. Technol.79, 260–269. 10.2166/wst.2019.041

52

Oh W. D. Dong Z. Lim T. T. (2016). Generation of sulfate radical through heterogeneous catalysis for organic contaminants removal: current development, challenges and prospects. Appl. Catal. B Environ.194, 169–201. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.04.003

53

Oladoye P. O. Ajiboye T. O. Wanyonyi W. C. Omotola E. O. Oladipo M. E. (2023). Insights into remediation technology for malachite green wastewater treatment. Water Sci. Technol.16 (3), 261–270. 10.1016/j.wse.2023.03.002

54

Rauf M. A. Ali L. Sadig M. S. Ashraf S. S. Hisaindee S. (2016). Comparative degradation studies of Malachite Green and Thiazole Yellow G and their binary mixture using UV/H2O2. Desalin. Water Treat.57, 8336–8342. 10.1080/19443994.2015.1017745

55

Rehman F. Parveen N. Iqbal J. Sayed M. Shah N. S. Ansar S. et al (2023). Potential degradation of norfloxacin using UV-C/Fe2+/peroxides-based oxidative pathways. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem.435, 114305. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2022.114305

56

Rehman F. Sayed M. Khan J. A. Shah N. S. Khan H. M. Dionysiou D. D. (2018). Oxidative removal of brilliant green by UV/S2O82‒, UV/HSO5‒ and UV/H2O2 processes in aqueous media: a comparative study. J. Hazard. Mater.357, 506–514. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.06.012

57

Sepúlveda M. Musiał J. Saldan I. Chennam P. K. Rodriguez-Pereira J. Sopha H. et al (2024). Photocatalytic degradation of naproxen using TiO2 single nanotubes. Front. Environ. Chem.5, 1373320. 10.3389/fenvc.2024.1373320

58

Shah N. S. He X. Khan J. A. Khan H. M. Boccelli D. L. Dionysiou D. D. (2015). Comparative studies of various iron-mediated oxidative systems for the photochemical degradation of endosulfan in aqueous solution. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem.306, 80–86. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2015.03.014

59

Sharma J. Sharma S. Soni V. (2023). Toxicity of malachite green on plants and its phytoremediation: a review. Regional Stud. Mar. Sci.62, 102911. 10.1016/j.rsma.2023.102911

60

Singh K. Arora S. (2011). Removal of synthetic textile dyes from wastewaters: a critical review on present treatment technologies. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol.41, 807–878. 10.1080/10643380903218376

61

Sivaraman C. Vijayalakshmi S. Leonard E. Sagadevan S. Jambulingam R. (2022). Current developments in the effective removal of environmental pollutants through photocatalytic degradation using nanomaterials. Catalysts12 (5), 544. 10.3390/catal12050544

62

Slama H. B. Chenari Bouket A. Pourhassan Z. Alenezi F. N. Silini A. Cherif-Silini H. et al (2021). Diversity of synthetic dyes from textile industries, discharge impacts and treatment methods. Appl. Sci.11 (14), 6255. 10.3390/app11146255

63

Thao T. T. P. Nguyen-Thi M. L. Chung N. D. Ooi C. W. Park S. M. Lan T. T. et al (2023). Microbial biodegradation of recalcitrant synthetic dyes from textile-enriched wastewater by Fusarium oxysporum. Chemosphere325, 138392. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.138392

64

Tkaczyk A. Mitrowska K. Posyniak A. (2020). Synthetic organic dyes as contaminants of the aquatic environment and their implications for ecosystems: a review. Sci. Total Environ.717, 137222. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137222

65

Wei Y. Wang C. Liu D. Jiang L. Chen X. Li H. et al (2020). Photo-catalytic oxidation for pyridine in circumneutral aqueous solution by magnetic Fe-Cu materials activated H2O2. Chem. Eng. Res. Des.163, 1–11. 10.1016/j.cherd.2020.08.007

66

Xie Y. Wu K. Chen F. He J. Zhao J. (2001). Investigation of the intermediates formed during the degradation of malachite green in the presence of Fe3+ and H2O2 under visible irradiation. Res. Chem. Intermed.27, 237–248. 10.1163/156856701300356455

67

Yong L. Zhanqi G. Yuefei J. Xiaobin H. Cheng S. Shaogui Y. et al (2015). Photodegradation of malachite green under simulated and natural irradiation: kinetics, products, and pathways. J. Hazard. Mater.285, 127–136. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.11.041

Summary

Keywords

malachite green, UV light, hydrogen peroxide, photo-Fenton, degradation mechanism, wastewater treatment

Citation

Wilayat S, Fazil P, Khan JA, Zada A, Ali Shah MI, Al-Anazi A, Shah NS, Han C and Ateeq M (2024) Degradation of malachite green by UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes: kinetics and mechanism. Front. Chem. 12:1467438. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2024.1467438

Received

19 July 2024

Accepted

23 September 2024

Published

24 October 2024

Volume

12 - 2024

Edited by

Chao Zeng, Jiangxi Normal University, China

Reviewed by

Xiaohui Ren, Wuhan University of Science and Technology, China

István Székely, Babeș-Bolyai University, Romania

Chunhui Dai, East China University of Technology, China

Jianhua Zhang, Wuhan Textile University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Wilayat, Fazil, Khan, Zada, Ali Shah, Al-Anazi, Shah, Han and Ateeq.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Javed Ali Khan, javedkhan@awkum.edu.pk, khanjaved2381@gmail.com; Muhammad Ateeq, m.ateeq@awkum.edu.pk

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.