Abstract

Introduction:

Lung cancer prevalence rate has been rising steadily in recent years, for the prevention and treatment, the detection of tumor marker CYFRA 21-1 DNA demonstrates its significance.

Methods:

In this work, an electrochemical biosensor was constructed for sensitive detection of CYFRA 21-1 DNA based on the novel developed Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 magnetic heterogeneous nanorods (MHNRs). Firstly, Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs were prepared by hydrothermal-calcination method, and then Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au magnetic nanocomposites (MNCs) were obtained though gold-coating. Subsequently, the magnetic self-assembling electrochemical biosensor based on Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs was successfully constructed, which was verified by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). To optimize the biosensor’s experimental conditions and evaluate its performance, differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) was conducted.

Results and Discussion:

The results showed that the detection range of CYFRA 21-1 DNA was 10 pM–10 μM, the limit of detection (LOD) was 1.5 pM. The biosensor exhibited excellent selectivity, reproducibility, and stability; the relative standard deviation (RSD) was 2.01%. The average recovery rate in the spiked diluted human serum samples was 101.4%, and the RSD was ≤5.2%, indicating that the biosensor possessed promising prospect.

1 Introduction

Based on the statistics of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), approximately one fifth of the global human population will be diagnosed with cancer during their lifetime, there into, lung cancer is the most frequently malignant tumor with an incidence of 12.4% and mortality of 18.7% (Bray et al., 2024). The early-stage symptoms of lung cancer are not obvious and non-specific, which mimic those of other respiratory diseases or common colds (Candal-Pedreira et al., 2024; Tsiligianni et al., 2024). Therefore, the majority of lung cancer cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage, thus missing the best treatment period (Servadio et al., 2024). While, early diagnosis can effectively improve the survival rate of patients (Basha et al., 2025; Blanco-Villar et al., 2024; Tesema et al., 2025). Consequently, the development of a real-time and accessible modality for the early lung cancer detection represents an urgent need (Fang et al., 2025; Wang Y. Z. et al., 2025).

Minimally invasive and non-invasive body fluid detection is a novel method for dynamic monitoring of cancer development, offering considerable advantages in terms of safety and comfort (Huang S. et al., 2024). Serum detection of biomarkers is a powerful means to promote prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of tumors. The biomarkers with diagnostic value for lung cancer mainly include cytokeratin 19 fragment (CYFRA 21-1) (Wang et al., 2020), neuron-specific enolase (NSE) (Wang K. Y. et al., 2025), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) (Chen, 2025), etc. It is worth noting that non-small cell lung cancers accounts for the significant majority of lung cancer patients (Li et al., 2021), and CYFRA 21-1 DNA has been verified as a reliable diagnostic biomarker for NSCLC (Zhao et al., 2020). Thus, the detection of serum CYFRA 21-1 DNA concentration is particularly important for the clinical diagnosis of early-stage lung cancer. So far, these several techniques including PCR (Mishra et al., 2018), polysaccharide and eATRP dual amplification sensor (Zhao et al., 2020), LoC-SERS (Bao et al., 2023), and SPR (Wang et al., 2016) have been successfully employed for the sensitive detection of CYFRA 21-1 DNA. However, there still exhibits several limitations, including but not limited to complex instruments, cumbersome operation, long response time and low economic efficiency. Nowadays, the detection of biomarkers is evolving toward convenient, rapid, and cost-effective strategies, with electrochemical biosensors emerging as a particularly promising solution.

In recent years, biosensors for biomarkers detection utilizing magnetic nanomaterials have gained widespread application due to their unique advantages such as magnetic separation and magnetic immobilization (Farag et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024; Yue et al., 2025). Magnetic ferrite nanomaterials, particularly α-Fe2O3 (hematite) and Fe3O4 (magnetite) have been extensively applied in biosensing owing to the characteristics of exceptional biocompatibility, low toxicity, and high surface area (Alshammari et al., 2024; Da Silva and Brett, 2020; Xue et al., 2025). Furthermore, integration with magnetic glassy carbon electrodes (MGCE) enables full utilization of the magnetic nanomaterials’ inherent advantages, significantly simplifying experimental procedures (Su et al., 2025; Xu et al., 2025). However, the magnetic property of α-Fe2O3 magnetic nanomaterials is too weak to enable the immobilization process (Tombuloglu et al., 2020), while that of Fe3O4 magnetic nanomaterials is too strong (Lu et al., 2025), causing the problem of agglomeration. To obtain the appropriate magnetic property for wider application, some scholars have developed Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 magnetic heterogeneous nanomaterials (Liu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2018). Moreover, the introduction of AuNPs has architected Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au magnetic nanocomposites, which not only enables superior current amplification efficiency in working electrodes but also creates the foundation for biosensor construction (Fukuzumi et al., 2025; Miao et al., 2025; Munusamy et al., 2025).

In this project, an electrochemical biosensor was developed employing Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 magnetic heterogeneous nanorods (MHNRs) as base substrate, where AuNP-ssDNA conjugate form a high-affinity bond as the connection that enable ssDNA to specifically capture CYFRA 21-1 DNA based on base complementary pairing for target detection. This system undergone magnetic self-assembly onto the MGCE surface, with subsequent microscopic events transformed into visual electrical signals through interface electron transfer kinetics. In particular, the biosensor was defined as indicator-free because it dispensed with the conjugation of signal-reporting moieties (e.g., fluorophores or electroactive molecules) to the target. Electrochemical characterization techniques, cyclic voltammetry (CV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were employed for the biosensor fabrication and interfacial analysis, while differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), owing to superior sensitivity, is utilized for parameters optimization and analytical performance evaluation.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

The materials, reagents and the corresponding suppliers are provided in the Supplementary Material.

The sequences of single-stranded oligonucleotides were followed.

Sulfhydryl probe (ssDNA): 5′-SH-GAAGGGAGGAATGGTGTCAGGGGCG-3′

CYFRA 21-1 DNA (tDNA): 5′-CGCCCCTGACACCATTCCTCCCTTC-3′

Single-base mismatch sequence (SBM DNA): 5′-CGCCCCTGACTCCATTCCTCCCTTC-3′

Double-base mismatch sequence (DBM DNA): 5′-CGCGCCTGACTCCATTCCTCCCATC-3′

Negative control sequence (NC DNA): 5′-TATTAGCCGTCAGTGGAAAGGACCT-3′.

2.2 Preparation and characterization of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs

The Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs were fabricated using a hydrothermal-calcination method. Initially, 2.0 g of anhydrous ferric chloride (FeCl3) and 1.0 g of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) were dissolved in 70 mL double-distilled water (DDW). The system was then subjected to ensure complete dissolution and homogeneity. After transferring into a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave, it was placed in hydrothermal treatment at 100 °C for 10 h in a programmable temperature-controlled furnace. After the reaction, the supernatant was removed to get the sediment, which was subsequently washed three times with anhydrous ethanol, and then dried to obtain β-FeOOH nanorods.

Next, galactose and β-FeOOH nanorods were uniformly mixed in a 2:1 mass ratio and transferred into a crucible for further processing. It was calcined in a muffle furnace at 300 °C for 30 min, the calcined product was Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs.

To achieve Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs, the preparation of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@PEI was a prerequisite. 1.6 g of polyvinylimine (PEI) was added in 160 mL of DDW, stirring thoroughly until fully dissolved. The solution was supplemented with 60 mg of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs, and the resulting suspension was maintained at ultrasound for 30 min. The suspension was transferred to a round-bottom flask and reacted in a water bath at 90 °C for 90 min with magnetic stirring. Upon completion of the reaction, the precipitate was collected by centrifugation. It was subsequently washed twice with DDW and dried to obtain Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@PEI.

The Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs were prepared via the modified sodium borohydride reduction method for chloroauric acid. The whole experimental procedures were conducted under low-temperature conditions. 15 mg Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@PEI were dispersed in 225 mL of DDW under ultrasound treatment for 10 min 1.5 mL chlorauric acid solution (20 mg/mL) was added dropwise to the suspension under continuous stirring. The mixture was then kept under ultrasound for 30 min. Subsequently, 3 mL trisodium citrate solution (38 mM) was dropped into the above suspension, followed by 1 min of stirring. Then, 13 mL sodium borohydride solution (0.075 wt%) was added dropwise to the reaction mixture under continuous stirring for the reduction of chlorauric acid, and maintained stirring for 15 min. The resulting suspension was centrifuged to remove the liquid supernatant. The Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs were obtained by washing twice with DDW and grinding after drying.

The morphological and compositional characteristics of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs and Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs were analyzed using the scanning electron microscope (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The crystalline phase of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs was identified by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku D/max 2500 PC) with Cu-Kα radiation. The magnetic measurement of both Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs and Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs was measured using a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM, ADE DMS-HF-4).

2.3 Construction and evaluation of the indicator-free electrochemical biosensor

The indicator-free Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs biosensor was sequentially constructed. In the first place, 15 μL of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs (20 mg/mL) were mixed with 15 μL of activated ssDNA (2 μM) and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. In this process, ssDNA was bonded with Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs to synthesize Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au-ssDNA via Au-S bond. Additionally, magnetic separation was employed to remove supernatant, followed by washing with Phosphate Buffer Solution (PBS, pH 7.2) to eliminate the unbonded ssDNA. Furthermore, 50 μL Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, 0.25%) was incubated with the resulting solid at 25 °C for 30 min to minimize nonspecific binding. Similarly, magnetic separation was used to isolate the target nanocomposites and PBS applied to remove unbound substances. In the next step, 30 μL of CYFRA 21-1 DNA solution (1 μM) was added to the product obtained from the previous step and hybridized at 65 °C for 5 min in a water bath shaker (Tm for ssDNA and CYFRA 21-1 DNA of 66.89 °C). Then, the magnetic separation and washing procedures were repeated. 30 μL of ultrapure water was added to form suspension, which of 9 μL was drop-casted onto the pretreated magnetic glassy carbon electrode (MGCE) surface and dried in 37 °C, and electrochemical measurements were subsequently performed on a CHI-760E electrochemical workstation containing 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− and 0.1 M KCl in ultrapure water with MGCE, Ag/AgCl electrode, and Pt electrode respectively as the working electrode, reference electrode, and the counter electrode. The feasibility of the stepwise fabrication process was systematically verified using CV, EIS, and DPV with the scan voltage of −0.1–0.7 V and scan rate of 100 mV/s for CV, the frequency range of 0.1 Hz–10 kHz and signal amplitude of 5 mV for EIS, and the measure voltage of 0.2 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for DPV analysis.

While, unless specifically indicated, triplicate independent parallel experiments (n = 3) were carried out under identical conditions for validating the reliability of the data. The error bars were shown in the graphs correspond to standard deviation (SD) calculated from the replicates.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Principle of the indicator-free electrochemical biosensor

The stepwise construction procedures and detection process of the CYFRA 21-1 DNA biosensor were schematically illustrated in Scheme 1. To begin with, the integration of AuNPs with Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs offered abundant binding sites for ssDNA and amplified current signal. The modified ssDNA was stably immobilized onto surface Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs via Au-S covalent bonding. Furthermore, BSA was employed as a blocking agent and surface passivating agent to minimize non-specific binding and prevent potential interference from extraneous factors. Lastly, the target CYFRA 21-1 DNA bound specifically to ssDNA through the principle of Watson-Crick base pairing, causing measurable alterations in electrical signals to achieve detection purposes. It was worth mentioning that in this strategy, the MHNRs could be incubated in liquid phase, and subsequently magnetically self-assembled onto the surface of MGCE, forming a uniform film to service electrochemical measurements.

SCHEME 1

Schematic representation of the biosensor for the detection of CYFRA 21-1 DNA.

3.2 Characteristics of nanomaterials

The structural, morphological, and compositional properties of nanomaterials utilized to construct the biosensor were characterized, as illustrated in Figure 1. The TEM image of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 was presented in Figure 1A. The Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 exhibited a well-defined rod-like morphology and uniform particle size distribution (Figures 1B,C), with an average length of 443 nm and a diameter of 109 nm. Following the reduction of HAuCl4 by NaBH4, TEM analysis (Figure 1D) revealed the successful attachment of spherical AuNPs with a diameter of 11 nm onto the surfaces of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs (denoted as Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au), the diameter distribution of AuNPs was shown in Figure 1E, while, the corresponding EDS spectrogram of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs was displayed in Figure 1F, the element (atomic%) ratios of O, Fe, and Au on their surfaces were 23.89%, 57.53%, and 18.58%. According to the results of EDS, the loading efficiency of AuNPs was calculated, and achieved 10.24%.

FIGURE 1

TEM image (A), length distribution (B), and diameter distribution (C) of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs, TEM image (D) of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs, the diameter distribution (E) of AuNPs, EDS spectrogram (F) of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs, XRD pattern (G) of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs, the hysteresis loops (H) and N2 physisorption curves (I) of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs and Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs.

In Figure 1G, the XRD data of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs was displayed. Thereinto, the diffraction peaks at 2θ = 30.1°, 35.4°, and 62.5° were indexed to the (220), (311), and (440) planes of the face-centered cubic (FCC) structure, respectively, consistent with the reference PDF card (JCPDS No. 19-0629), which indicated the existence of Fe3O4 crystalline phase. Nevertheless, the presence of distinct non-Fe3O4 characteristic diffraction peaks at 2θ = 24.1° (012), 33.2° (104), and 49.5° (024), along with an excessive peak response at approximately 35°, suggesting the existence of α-Fe2O3 in the nanomaterials, as confirmed by comparison with the reference PDF card (JCPDS No. 33-0664). The coexistence of Fe3O4 and α-Fe2O3 demonstrated the successful fabrication of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs. The magnetic properties of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs and Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs were depicted in Figure 1H. The hysteresis loops of the two nanomaterials exhibited saturation magnetizations (Ms) of 18.0 emu/g and 9.8 emu/g, respectively. The results revealed that following the incorporation of non-magnetic AuNPs, the Ms of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs decreased; however, this value was sufficient for efficient magnetic separation and magnetic self-assembly procedures. N2 physisorption curves of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs and Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs were displayed in Figure 1I, their adsorption curves belonged to type-IV and H3-type hysteresis loops, and their specific surface areas reached 36.8 m2/g and 29.4 m2/g, the values were relatively smaller owing to the larger density of density. Meanwhile, the loading of AuNPs obviously led to a decrease of 7.4 m2/g for specific surface area, the reason for this may be that AuNPs occupied part of the pores, which also further demonstrated the successful preparation of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs.

To further verify the successful preparation of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs, XPS analysis technique was employed to ascertain the chemical state and elements composition of the product as Figure 2. Firstly, the comprehensive spectrum was shown in Figure 2A, the states of all the chemical elements were annotated. Figure 2B displayed the XPS spectrum of Fe 2p, revealing the distinct peaks at 710.27 eV and 724.07 eV respectively corresponding to Fe 2p3/2 and Fe 2p1/2. The peaks at 712.59 eV and 726.79 eV indicated the existence of Fe3+; while, the peaks at 710.39 eV and 724.09 eV certified the existence of Fe2+. Furthermore, the satellite peaks resulting from energy dissipation caused by electron transitions in the valence band were observed at 718.89 eV and 733.39 eV. In the C 1s spectrum (Figure 2C), the C-O peak was observed at 285.99 eV; while, the O-C=O peak appeared at 288.39 eV. These peaks corresponded to the presence of C-O/O-C=O peak at 530.77 eV in the O 1s spectrum (Figure 2D). The spectrum of Au 4f was revealed in Figure 2E, the peaks were anastomotic with the binding energies at 83.89 eV and 87.49 eV, suggesting the existence of Au in the product. These characteristics collectively validated again the successful preparation of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs.

FIGURE 2

XPS survey (A) and Fe 2p (B), C 1s (C), O 1s (D), and Au 4f (E) core-level spectra recorded of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au.

3.3 Detection feasibility of the biosensor

The construction of the biosensor was characterized utilizing CV and EIS to validate its feasibility (Yue et al., 2024). In Figure 3A, the REDOX peaks of [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− showed variations with different modified electrodes. Initially, compared with the current of the unmodified MGCE (curve a), the redox current significantly decreased after the modification with the Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs (curve b), which could be associated with the increased electron transfer resistance resulting from the MHNRs. In contrast, the current of MGCE/Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au (curve c) exhibited a notable increase, which was induced by the integration of highly conductive AuNPs that evidently enhance the electron transfer rate. When the ssDNA was chemisorbed onto the MNCs through Au-S bond, the electron transfer resistance increased. Moreover, the negatively charged phosphate backbone of ssDNA introduced electrostatic repulsion with the [Fe(CN)6]3−/4−, leading to a reduction in the redox current (curve d). The current value of curve e was further reduced due to the insulating effect of BSA. Ultimately, following the material which Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au-ssDNA/BSA hybridized with CYFRA 21-1 DNA was modified to the surface of MGCE, the redox current demonstrated a further reduction (curve f), the mechanism underlying current reduction was similar to the effect observed with ssDNA, indicating that ssDNA successfully captured the target CYFRA 21-1 DNA. In summary, the verification of these processes not only confirmed the feasibility of the proposed strategy but also established a robust foundation for subsequent experimental investigations.

FIGURE 3

CV (A) and EIS spectra (B) of [Fe(CN)6]3-/4- at various modified electrodes: (a) unmodified MGCE, (b) MGCE/Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3, (c) MGCE/Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au, (d) MGCE/Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au-ssDNA, (e) MGCE/Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au-ssDNA/BSA, and (f) MGCE/Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au-ssDNA/BSA/CYFRA 21-1 DNA.

The EIS curves which represented the electron transfer resistance (Ret) under various loading conditions as depicted in Figure 3B. Firstly, it was essential to clarify that the semicircle radius observed in the Nyquist plot provided a direct indication of the Ret (Ito et al., 2019). The trends of its semicircle radius were distinctly observed in Figure 3B. With the exception of curve c, the semicircle radius of the other curves was larger compared with those of the previous steps. These results excellently agreed with the observed trends of CV curves, further indicating the detection feasibility of the biosensor.

3.4 Optimization of experimental conditions

The sensitivity and stability of the biosensor were critically dependent on several important experimental parameters. To achieve optimum detection performance, the following four critical parameters–the concentrations of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs and ssDNA, target hybridization time and temperature were optimized.

The quantity of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs significantly influenced the number of captured targets, the amplification effect of the current, and the incubation efficiency. Therefore, its optimization was crucial. All the results were illustrated in Figure 4A, as the concentration increased, the current values exhibited an initial rise followed by a subsequent decline. These phenomena could be induced by the insufficient current enhancement effect of AuNPs at low concentrations, whereas at high concentrations, excessive surface loading on the MGCE hindered electron transfer. Therefore, the Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs with a concentration of 15 mg/mL corresponding to the highest current point was the optimal concentration.

FIGURE 4

DPV responses for the optimization of the Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au concentration (A), the ssDNA concentration (B), target hybridization time (C), and target hybridization temperature (D).

Subsequently, the concentration optimization of ssDNA (Tm = 66.89 °C) was displayed in Figure 4B, which determined the maximum capture capacity of analyte. In the first place, an increase in ssDNA concentration from 0.5 μM to 1.5 μM caused a significant reduction in the current, indicating an elevation in the amount of ssDNA bound to the Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au MNCs via the Au-S bond. Secondly, within the concentration range of 1.5 μM–2.5 μM, the current remained relatively stable, confirming that the available AuNPs binding sites on the MNCs were almost entirely occupied. Consequently, the results showed that the ideal ssDNA concentration was 1.5 μM, which corresponded to the current saturation point. Ultimately, optimized hybridization conditions for the capture probe and CYFRA 21-1 DNA (Tm = 66.89 °C) played a critical role in determining the biosensor’s sensitivity and stability. A direct correlation had been demonstrated between the number of captured CYFRA 21-1 DNA and the electrochemical response (Huang S. et al., 2024), manifested as increased Ret on the MCCE surface, resulting in reduced current. Hence, in Figures 4C,D, the lower current values indicating more effective probe-target complex formation. Then, the optimal hybridization conditions were determined to be 65 °C for 15 min, corresponding to the minimum current values. Following condition optimization, the biosensor’s overall performance was expected to significantly improve.

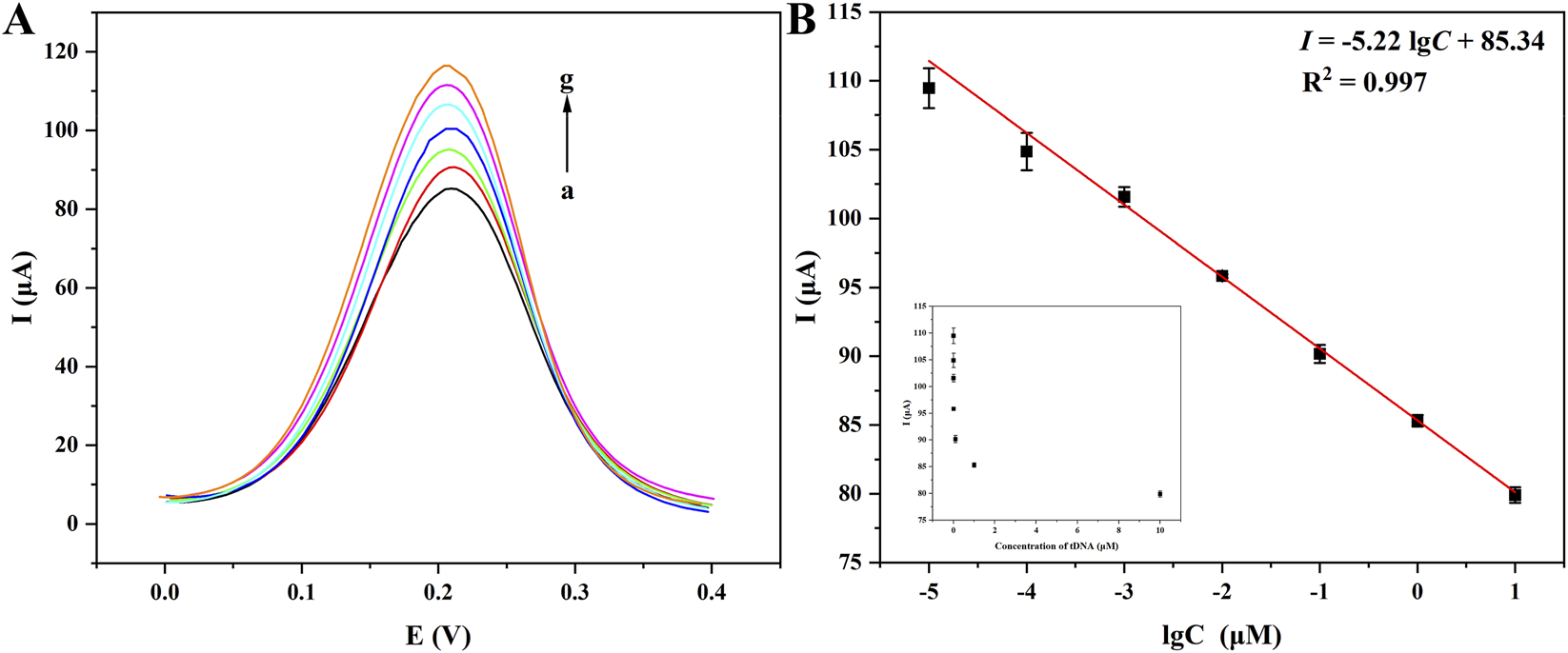

3.5 Detection of CYFRA 21-1 DNA

Under the optimized conditions, the biosensor’s performance was comprehensively evaluated using CYFRA21-1 DNA as the model analyte. Firstly, the correlation between CYFRA 21-1 DNA concentration (C) and the DPV current response was systematically analyzed. In Figure 5, with the increase of CYFRA 21-1 DNA concentration, the DPV peak decreased as Figure 5A, and a strong linear correlation was demonstrated between the logarithm of the CYFRA 21-1 DNA concentration and current response in the range of 10 pM–10 μM as Figure 5B. The linear equation was expressed as I = −5.22 lgC + 85.34 (R2 = 0.997), with a limit of detection (LOD) of 1.5 pM and a limit of quantification (LOQ) of 4.5 pM, calculated by 3σ and 10σ criteria, respectively. The biosensor exhibited an extensive linear range and a low detection threshold, which could be attributed to the signal amplification capability of AuNPs and the high binding specificity of CYFRA 21-1 DNA toward ssDNA. Compared with the literature reported in past 3 years (listed in Table 1), according to the molecular weight (MW) of 196.20 for CYFRA 21-1 DNA, the liner range of this work reached 1962 pg/L-1962 μg/L (i.e. 1.962 pg/mL–1.962 μg/mL), obviously, the upper limit of the range has been largened about 20 times compared with that reported by Huang et al. (Huang Z. Q. et al., 2024), while, the lower limit of the range is only about 2 times. Therefore, the liner range has been broadened, and adapted the clinical application for the detections of healthy people and patients. While, the biosensors revealed more lower LOD, lower cost, and shorter detection period. All the data suggested their promising prospect of clinical application.

FIGURE 5

DPV curves of CYFRA 21-1 at different concentrations detected by the biosensor of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au-DNA/BSA as probe (A): (a–g): 10 μM, 1 μM, 100 nM, 10 nM, 1 nM, 100 pM, 10 pM; linear relationship between different concentrations of CYFRA 21-1 DNA and currents (B).

TABLE 1

| Detection approach | Linear range | LOD | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence | 0.1 fM–105 fM | 7.8 × 10−2 fM | Huang et al. (2024a) |

| Electrochemiluminescence | 1 fg/mL–108 fg/L | 0.4 fg/mL | Huang et al. (2024b) |

| Electrochemiluminescence | 10 fg/mL–5 × 107 ng/mL | 5.5 fg/mL | Ren et al. (2024a) |

| Electrochemiluminescence | 102 fg/mL−107 fg/mL | 46 fg/mL | Ren et al. (2024b) |

| Electrochemical | 104 fg/mL−1010 fg/mL | 104 fg/mL | Wang et al. (2023) |

| Photoelectrochemical | 102 fg/mL–5 × 107 fg/mL | 50 fg/mL | Zhang et al. (2023) |

| Electrochemical | 15 fg/mL–90 × 103 fg/mL | 4.59 × 103 fg/mL | Aydın et al. (2023) |

| Electrochemical | 5 × 103 fg/mL–4 × 108 fg/mL | 1.15 × 103 fg/mL | Cai et al. (2023) |

| Electrochemical | 104 fM–1010 fM | 1.5 × 103 fM | This work |

Comparison of the reported electrochemical methods for CYFRA 21-1 detection.

3.6 Selectivity, reproducibility, stability of the biosensor

To further evaluate the biosensor’s performance, systematic investigations were conducted to verify its selectivity, reproducibility, and stability. To begin with, comparative detection experiments were performed using SBM DNA, DBM DNA, and NC DNA as potential interfering substances to assess the selectivity and eliminate potential false positive signals, with the results compared against the CYFRA 21-1 DNA target group. As elucidated in Figure 6A, the current difference (ΔI) between the other groups (SBM DNA, DBM DNA, NC DNA, and their mixture (Mix)) and blank group was minimal, within a 5 μA margin, whereas the tDNA group revealed a distinct response with ΔI of −24.1 μA, and the Mix group also revealed similar response with ΔI of −23.7 μA, the response of Mix had no influence because of the addition of the other substances, which revealed the excellent antijamming capability of the biosensor. The experimental results conclusively demonstrated the high specificity of this biosensor.

FIGURE 6

Selectivity (A), reproducibility (B), and stability (C) study of the biosensor using Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au-DNA/BSA as probes.

Furthermore, under optimized and strictly controlled experimental conditions, eight parallel tDNA detection experiments were executed (Figure 6B), with a relative standard deviation (RSD) of 2.01%, confirming excellent reproducibility. Lastly, Figure 6C presented the measurement results of batch-prepared Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au-ssDNA/BSA nanocomposites, which were stored in stored at 4 °C in PBS (pH = 7.4) for varying durations prior to incubation with tDNA. The measurement results revealed that the biosensor currents exhibited small fluctuation over the course of 14 days, confirming it possessed long-term storage stability. In conclusion, the developed biosensor demonstrated exceptional selectivity, reproducibility, and operational stability, rendering significant potential for practical applications in cancer diagnosis.

3.7 Analysis of real samples

The addition-recovery strategy with 20-fold diluted human serum was designed for evaluating the application of the biosensor in real samples. Varying concentrations of spiked CYFRA 21-1 (10 nM, 1 nM, and 100 pM) were measured. The results with treated current responses were outlined in Table 2, the recovery rates were indicated to range from 90.0% to 107.8%, and the relative standard deviation (RSD) was ≤5.2%, indicating excellent precision. In conclusion, the biosensor demonstrated outstanding resistance to interference and practical application capability, which suggesting potential for clinical detection purposes.

TABLE 2

| Spiked (nM) | Test (nM) | Recovery (%) | RSD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 10.64 | 106.4 | 4.3 |

| 1 | 1.078 | 107.8 | 1.8 |

| 0.1 | 0.090 | 90.0 | 5.2 |

Determination of CYFRA 21-1 concentration in spiked human serum samples using Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au-DNA/BSA as probes.

4 Conclusion

In this project, an indicator-free electrochemical biosensor was competently constructed, which employed the Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 MHNRs as basic framework for supersensitive detection of CYFRA 21-1 DNA. The AuNPs-based modification strategy not only created binding sites for ssDNA, but also amplified the current signal. The target CYFRA21-1 DNA was captured through high-affinity base complementary pairing. The increase in electrochemical current verified this process and achieved the detection purpose. The optimization experiments of the construction conditions had enhanced the sensitivity of this biosensor and establishes the foundation for performance analysis. This biosensor had high specificity, which could capable distinguishing SBM sequence, DBM sequence, and NC sequence. Furthermore, it possessed excellent reproducibility, stability, and the ability to conduct real sample analysis. In the future, the platform would be expected to develop into a powerful detection methodology for cancer biomarkers and other analytes, with promising translational prospects in clinical point-of-care diagnostics.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the ethical committee of Danyang People’s Hospital (Ethical number: 20250901-1). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

XY: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. PD: Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft. ZW: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing. JW: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. HW: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. Z-aW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the Zhenjiang Science & Technology Program (Grant Nos. SH2024041 and SH2023086).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2025.1696542/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Alshammari T. K. Ghoshal S. K. Bakhtiar H. Salim A. A. Alias S. S. (2024). Elucidating the structural and spectroscopic attributes of titania-iron oxide (TiO2-(α-Fe2O3)) nanocomposites: showcasing a pulsed laser ablation in liquid approach. Mater. Chem. Phys.318, 129235. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2024.129235

2

Aydın E. B. Aydın M. Sezgintürk M. K. (2023). Novel electrochemical biosensing platform based on conductive multilayer for sensitive and selective detection of CYFRA 21-1. Sensors Actuators B Chem.378, 133208. 10.1016/j.snb.2022.133208

3

Bao X. T. Wang S. Y. Liu X. Y. Li G. (2023). Highly sensitive detection of CYFRA21-1 with a SERS sensing platform based on the MBs enrichment strategy and antibody-DNA-mediated CHA amplification. Front. Bioeng. Biotech.11, 1251595. 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1251595

4

Basha S. K. A. H. Kshirsagar P. R. Rao P. S. Tak T. K. Sivaneasan B. (2025). PCA-F-SHCNNet: Principal component analysis-fused-shepard convolutional neural networks for lung cancer detection and severity level classification. Biomed. Signal. Proces.107, 107843. 10.1016/j.bspc.2025.107843

5

Blanco-Villar M. L. Expósito-Hernández J. Navarro-Moreno E. Martín J. M. L. Mota A. A. Couñago F. (2024). Analyzing diagnostic and treatment wait times for lung cancer patients: key insights from a provincial registry study. Lung Cancer194, 107867. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2024.107867

6

Bray F. Laversanne M. Sung H. Ferlay J. Siegel R. L. Soerjomataram I. et al (2024). Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA-Cancer J. Clin.74, 229–263. 10.3322/caac.21834

7

Cai K. Pi W. Qin J. Peng C. Wang D. Gu Y. et al (2023). Detection of CYFRA 21-1 in human serum by an electrochemical immunosensor based on UiO-66-NH2@CMWCNTs and CS@AuNPs. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces230, 113517. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2023.113517

8

Candal-Pedreira C. Ruano-Ravina A. Calvo de Juan V. Cobo M. Cantero A. Rodríguez-Abreu D. et al (2024). Analysis of diagnostic delay and its impact on lung cancer survival: results from the Spanish thoracic tumor registry. Arch. Bronconeumología60, S38–S45. 10.1016/j.arbres.2024.07.006

9

Chen L. L. (2025). Assessing the diagnostic utility of serum tumor markers for lung cancer detection in patients with interstitial pneumonia. Clin. Transl. Oncol.27, 486–493. 10.1007/s12094-024-03638-7

10

Da Silva W. Brett C. M. A. (2020). Novel biosensor for acetylcholine based on acetylcholinesterase/poly (neutral red) - deep eutectic solvent/Fe2O3 nanoparticle modified electrode. Electroanal. Chem.872, 114050. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2020.114050

11

Fang R. J. Wang J. L. Han X. Li X. X. Tong J. J. Qin Y. S. et al (2025). Deciphering the molecular fingerprint of haemoglobin in lung cancer: a new strategy for early diagnosis using two-trace two-dimensional correlation near infrared spectroscopy (2T2D-NIRS) and machine learning techniques. Spectrochim. Acta A337, 126107. 10.1016/j.saa.2025.126107

12

Farag M. A. A. Eyhab A. Fenjan M. N. Yasser F. M. Sofiene M. Bokov D. O. et al (2025). Aptamer-magnetic nanoparticle complexes for powerful biosensing: a comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem.55, 502–515. 10.1080/10408347.2023.2298328

13

Fukuzumi N. Hirao G. Ogawa A. Asahi T. Maeda M. Zako T. (2025). Density and structure of DNA immobilised on gold nanoparticles affect sensitivity in nucleic acid detection. Sci. Rep.15, 8222. 10.1038/s41598-025-92474-y

14

Huang S. Liu S. Fang Y. Li H. H. Yang M. L. Wang W. et al (2024a). An ultra-sensitive electrochemical biosensor for circulating tumor DNA utilizing dual enzyme-assisted target recycle and hybridization chain reaction amplification strategies. Microchem. J.204, 111164. 10.1016/j.microc.2024.111164

15

Huang Z. Q. Zhao L. Li Y. Y. Wang H. Ma H. M. Wei Q. et al (2024b). Glucose oxidation induced pH stimuli response controlled release electrochemiluminescence biosensor for ultrasensitive detection of CYFRA 21-1. Talanta266, 124955. 10.1016/j.talanta.2023.124955

16

Ito Y. Okuda-Shimazaki J. Tsugawa W. Loew N. Shitanda I. Lin C. E. et al (2019). Third generation impedimetric sensor employing direct electron transfer type glucose dehydrogenase. Biosens. Bioelectron.129, 189–197. 10.1016/j.bios.2019.01.018

17

Li X. F. Zhang Y. W. Hao L. L. Liu Y. J. Wang X. Yang H. X. et al (2021). Ultrasensitive label-free detection for lung cancer CYFRA 21-1 DNA based on ring-opening polymerization. Talanta223, 121730. 10.1016/j.talanta.2020.121730

18

Liu T. Zhang S. T. Wang Z. Xu Y. Y. (2022). Preparation and characterization of α-Fe2O3/Fe3O4 heteroplasmon nanoparticles via the hydrolysis-combustion-calcination process of iron nitrate. Mater. Res. Express.9, 045011. 10.1088/2053-1591/ac68c6

19

Lu Y. Wang X. Jia Y. J. Zhang S. Yang J. K. Li Q. et al (2025). PAD4 inhibitor-loaded magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles for magnetic targeted chemotherapy and magnetic resonance imaging of lung cancer. Int. J. Nanomed.20, 3031–3044. 10.2147/IJN.S502814

20

Miao J. Y. Liu Y. F. Xiao Y. Yuan C. Z. Xu Q. Chen P. P. et al (2025). Water-stable perovskite/metallic nanocomposites-based SERS aptasensor for detection of neuron-specific enolase. Biosens. Bioelectron.280, 117462. 10.1016/j.bios.2025.117462

21

Mishra A. Singh N. Sahu D. K. Kumar S. (2018). 33P expression of biomarkers IDH1, CEA, TPA and CYFRA21-1 in peripheral blood and tissue of non-small cell lung carcinoma patients detected by real-time PCR. J. Thorac. Oncol.13, S18. 10.1016/S1556-0864(18)30313-7

22

Munusamy S. Zheng H. Y. Jahani R. Zhou S. Chen J. Kong J. H. et al (2025). DNA-assisted CRISPR-Cas12a enhanced fluorescent assay for protein detection in complicated matrices. ACS Appl. Bio. Mater.8, 754–762. 10.1021/acsabm.4c01600

23

Ren X. Shao M. Y. Li X. F. Xie Z. X. Zhao J. X. Wang H. et al (2024a). Confinement-enhanced electrochemiluminescence by Ru(dcbpy)32+-functionalized γ-CD-MOF@COF-LZU1 porous hybrid material as micro-reactor for CYFRA 21-1 detection. Talanta273, 125959. 10.1016/j.talanta.2024.125959

24

Ren X. Shao M. Y. Xie Z. X. Li X. J. Ma H. M. Fan D. W. et al (2024b). A co-reactive immunosensor based on Ti3C2Tx MXene@TiO2–MoS2 hybrids promoting luminol@Au@Ni–Co NCs electrochemiluminescence for CYFRA 21–1 detection. ACS Sens.9, 1992–1999. 10.1021/acssensors.3c02784

25

Servadio M. Rosa A. C. Addis A. Kirchmayer U. Cozzi I. Michelozzi P. et al (2024). Investigating socioeconomic disparities in lung cancer diagnosis, treatment and mortality: an Italian cohort study. BMC Public Health24, 1543. 10.1186/s12889-024-19041-4

26

Su L. T. Yang Z. Q. Peng H. P. Liu A. L. (2025). A dual nano-signal probe-based electrochemical immunosensor for the simultaneous detection of two biomarkers in gastric cancer. Biosensors15, 80. 10.3390/bios15020080

27

Tesema G. A. Stirling R. G. Wah W. Tessema Z. T. Heritier S. Earnest A. (2025). Geographic variation in delay to surgical treatment among non-small cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer199, 108077. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2024.108077

28

Tombuloglu H. Slimani Y. AlShammari T. M. Bargouti M. Ozdemir M. Tombuloglu G. et al (2020). Uptake, translocation, and physiological effects of hematite (α-Fe2O3) nanoparticles in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Environ. Pollut.266, 115391. 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115391

29

Tsiligianni I. Christodoulakis A. Monastirioti A. Mavroudis D. Agelaki S. (2024). The journey of lung cancer patients from symptoms to diagnosis in Greece. A mixed methods approach. NPJ Prim. Care Resp. M.34, 1–9. 10.1038/s41533-024-00359-w

30

Wang H. Wang X. M. Wang J. Fu W. L. Yao C. Y. (2016). A SPR biosensor based on signal amplification using antibody-QD conjugates for quantitative determination of multiple tumor markers. Sci. Rep.6, 33140. 10.1038/srep33140

31

Wang Z. L. Fan Y. P. Wu R. Huo Y. X. Wu H. Wang F. et al (2018). Novel magnetic g-C3N4/α-Fe2O3/Fe3O4 composite for the very effective visible-light-fenton degradation of Orange II. RSC Adv.8, 5180–5188. 10.1039/C7RA13291C

32

Wang X. Zhang Y. W. Zhao L. Y. Wang D. Z. Yang H. X. Kong J. M. (2020). Polysaccharide-enhanced ARGET ATRP signal amplification for ultrasensitive fluorescent detection of lung cancer CYFRA 21-1 DNA. Anal. Bioanal. Chem.412, 2413–2421. 10.1007/s00216-020-02394-1

33

Wang J. J. Yang X. M. Hua X. Li Y. N. Jin B. K. (2023). Novel ratiometric electrochemical biosensor for determination of cytokeratin 19 fragment antigen 21-1 (Cyfra-21-1) as a lung cancer biomarker. Anal. Lett.56, 2708–2724. 10.1080/00032719.2023.2181970

34

Wang X. L. He L. Y. Li Y. X. Guo J. Wang C. C. (2024). A chemiluminescence immunosensor for biomarker detection based on boronic acid-modified magnetic composite microspheres. J. Mater. Chem. B12, 10285–10293. 10.1039/D4TB01582G

35

Wang K. Y. Chang Z. X. Li Y. J. Wang Y. N. Tang Y. Gao X. N. et al (2025a). Precise detection of NSE and ProGRP with nanoprobes for early diagnosis of small cell lung cancer. Chem. Commun.61, 3179–3182. 10.1039/D4CC06230B

36

Wang Y. Z. Su C. Liang X. Li X. X. Jing M. X. Wang Q. et al (2025b). Diagnosis of PD-L1 related non-small cell lung cancer from micro-liters blood. Talanta293, 128077. 10.1016/j.talanta.2025.128077

37

Xu Z. H. Lv Z. X. Yang H. J. Zhang J. S. Sun Z. J. He D. W. et al (2025). Label-free electrochemical biosensor with magnetic self-assembly constructed via PNA-DNA hybridization process on α-Fe2O3/Fe3O4 nanosheets for APOE ε4 genes ultrasensitive detection. Bioelectrochemistry161, 108847. 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2024.108847

38

Xue M. J. Sang S. B. Zhao D. Duan Q. Q. Guo X. (2025). A flexible magnetic DNA biosensor composed of AgNWs/hydrogel/PS/Fe3O4 for the detection of ASFV P72 protein gene fragment. Microchim. Acta192, 268. 10.1007/s00604-025-07114-z

39

Yue Y. Zhang X. J. Xu Z. H. Sun L. Li S. S. Liu R. J. (2024). Ultrasensitive detection of PSA in human serum using label-free electrochemical biosensor with magnetically induced self-assembly based on α-Fe2O3/Fe3O4@Au nanocomposites. Microchem. J.201, 110487. 10.1016/j.microc.2024.110487

40

Yue Y. Liu M. Ma M. Y. Xu Z. H. Zhang H. D. Wang Q. X. et al (2025). CRISPR/Cas14a integrated with DNA walker based on magnetic self-assembly for human papillomavirus type 16 oncoprotein E7 ultrasensitive detection. Biosens. Bioelectron.272, 117135. 10.1016/j.bios.2025.117135

41

Zhang Y. Y. Wu T. T. Cui Q. Q. Qu Z. F. Zhang Y. Ma H. M. et al (2023). ReS2@Au NPs as signal labels quenching steady photocurrent generated by NiCo2O4/CdIn2S4/In2S3 heterojunction for sensitive detection of CYFRA 21-1. Biosens. Bioelectron.222, 114992. 10.1016/j.bios.2022.114992

42

Zhao L. Y. Yang H. X. Zheng X. K. Li J. G. Jian L. H. Feng W. S. et al (2020). Dual signal amplification by polysaccharide and eATRP for ultrasensitive detection of CYFRA 21–1 DNA. Biosens. Bioelectron.150, 111895. 10.1016/j.bios.2019.111895

Summary

Keywords

aptamer, CYFRA 21-1 DNA, detection, electrochemical biosensor, Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au magnetic nanocomposites

Citation

Yi X, Deng P, Wang Z, Wang J, Wang H and Wu Z-a (2025) Construction of the indicator-free electrochemical biosensor with magnetically self-assembly based on Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 magnetic heterogeneous nanorods for the ultra-sensitive detection of CYFRA 21-1 DNA. Front. Chem. 13:1696542. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2025.1696542

Received

01 September 2025

Revised

01 December 2025

Accepted

04 December 2025

Published

12 December 2025

Volume

13 - 2025

Edited by

Yixi Xie, Xiangtan University, China

Reviewed by

Chandrababu Rejeeth, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China

Wei-Wei Zhao, Nanjing University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Yi, Deng, Wang, Wang, Wang and Wu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hongfei Wang, zcwanghongfei@163.com; Zhan-ao Wu, wuzhanao359@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.