Abstract

An additive-free and ultrasound-assisted approach has been established for the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction between substituted boronic acid and benzofuran-endowed aryl halides by employing a catalytic amount of Pd(PPh3)4. The resulting substituted biaryls were then employed as efficient starting materials to furnish a novel library of arylated benzofuran-triazole hybrids 13(a–i). The method offers a facile, efficient, and less time-consuming approach under non-inert conditions to synthesize the targeted derivatives in a good to excellent yield range of 70%–92%.

Introduction

Carbon–carbon bond-forming reactions play a crucial role in the synthesis of several intricate organic compounds (Akhtar et al., 2019; Brahmachari, 2016; Mushtaq et al., 2024; Zahoor et al., 2024a). Among several carbon–carbon (C-C) bond formation reactions, the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction (SMCR) has found huge significance since its discovery by Akira Suzuki and Norio Miyaura in 1979 (Miyaura et al., 1979). They carried out the reaction by treating aryl halides with alkenylboranes employing tetrakis (triphenylphosphine)palladium Pd(PPh3)4 as a catalyst (Miyaura and Suzuki, 1979). As a Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction involves the linkage of a Csp2-Csp2 bond, it is predominantly involved in the synthesis of planar compounds, thereby validating its efficiency in the drug development process (Miyaura and Suzuki, 1995). In Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, aryl iodides (as Suzuki coupling partners) are generally the most reactive aryl halides (Panahi et al., 2018). Generally, aryl bromides are more commonly employed than aryl chlorides, whose reactivity is less than that of aryl iodides and bromides (Miyaura and Suzuki, 1995; Sonogashira, 1998; Stanforth, 1998; Suzuki, 1999; Miyaura, 1998). However, in a few Pd-catalyzed reactions, aryl bromides involving cross-coupling reactions have been observed to proceed more rapidly than aryl iodides. Moreover, Suzuki reactions involving aryl bromides have been reported to occur more rapidly under room temperature conditions than those involving aryl iodides (Littke et al., 2000).

SMCR involves the facile synthesis of biaryl scaffolds, which are abundantly found in several pharmaceutically active and synthetically significant organic molecules (Adlington et al., 2018; Farhang et al., 2022; Kotha et al., 2002). This reaction has also found applications in the synthesis of natural products (Taheri Kal Koshvandi et al., 2018). Non-toxicity, readily accessible reagents, and high stereo- and regioselectivity are some of the merits of SMCR over other coupling reactions. The reaction proceeds by employing homogeneous catalysis, thus offering remarkable activity and selectivity (Suzuki, 1999; Suzuki, 2002; Johansson Seechurn et al., 2012; Zhang and Wang, 2015). Several Pd-based homogenous catalysts have been employed for this reaction, including Pd(II) complexes (Nagalakshmi et al., 2020; Ortega-Gaxiola et al., 2020; Thunga et al., 2019), PdCl2 (Nobre et al., 2018), Pd2dba3, Pd(PPh3)4 (Czompa et al., 2019; Suzuki and Yamamoto, 2011), Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (Mai et al., 2019; Sarkar et al., 2020), Pd (dppf)Cl2 (Alza et al., 2015), and Pd(OAc)2 (Li et al., 2018; Louvis et al., 2016). Most of these reactions have been carried out under an inert atmosphere (nitrogen or argon) (Wang et al., 2001).

Several heterogeneous catalytic systems, which include metal-based heterogeneous catalysts trapped on water-insoluble support and palladium supported on carbon (Pd/C), have also been introduced for this reaction. These catalytic systems have been found to be favorable in terms of facile recovery of the catalyst, low catalyst requirement, and high catalytic activity (Amoroso et al., 2011; Sancheti and Gogate, 2018; Zheng et al., 2013). However, these catalysts have unveiled several deficiencies, including a need for additives, long reaction times, and more palladium content (Felpin et al., 2006; Maegawa et al., 2007; Polshettiwar et al., 2010; Rao et al., 2014). These notable shortcomings must be avoided by investigating novel methods for the Suzuki coupling reaction to carry out this significant reaction in low catalyst loading within short reaction times.

Various chemical and physical changes that occur as a result of cavitational events in an ultrasound reactor make it an effective apparatus for the facile conversion of reactants into target molecules. Ultrasound is processed through multiple rarefaction and compression cycles that are produced in a liquid medium. Upon passing through several growth stages, these cavities eventually partially collapse, leading to severe local heating and high pressure (Cintas et al., 2014; Mason, 1997). In addition, the rapid disintegration of the cavitating bubble results in liquid circulation and severe agitation. These physical effects facilitate the breakage of solid aggregates. These factors may also contribute to providing a large surface area, thereby facilitating the reaction to proceed rapidly. For these reasons, ultrasound-assisted methodologies are considered greener approaches as they involve intense processing and moderate reaction conditions with reduced probabilities of side products (Brahmachari et al., 2021; Cravotto et al., 2015; Irfan et al., 2022).

The literature survey highlights the employment of ultrasonic conditions for Suzuki–Miyaura coupling to access diverse organic compounds. The reported protocols involved the use of palladium-based catalysts, that is, Pd/C (Cravotto et al., 2005), Pd/PVP (de Souza et al., 2008), and Pd(PPh3)4 (Cella and Stefani, 2006) under ultrasonic conditions. Similarly, synthesis of polydihexylfluorene has also been carried out by using an ultrasound-assisted Suzuki cross-coupling reaction (Gao et al., 2014). All these instances emphasize the applications of ultrasound irradiation toward the fast and facile conversion of Suzuki coupling partners into desired coupling products.

Heterocycles are integral structural constituents of several bioactive organic compounds and drugs. Benzofuran and triazole are oxygen and nitrogen-containing heterocyclic scaffolds that are key structural units of several pharmaceutically significant organic compounds and therapeutic agents (Bozorov et al., 2019; Khanam and Shamsuzzaman, 2015). Benzbromarone 1, amiodarone 2, and saprisartan 3 are some of the clinically established benzofuran-endowed drugs. These drugs are known to treat gout, tachycardia, and hypertension, respectively (Nevagi et al., 2015). Similarly, nefazodone 4, anastrozole 5, and fluconazole 6 are some triazole-bearing market-available drugs that are effective against depression, breast cancer, and fungal diseases, respectively (Figure 1) (Kharb et al., 2011).

FIGURE 1

Structures of some benzofuran and triazole core-constituting drugs.

Bearing in mind the significance of ultrasound-assisted approaches and pharmaceutical significance of these heterogeneous scaffolds, we have carried out the novel synthesis of arylated benzofuran-triazole hybrids by utilizing a novel additive-free approach for Suzuki–Miyaura coupling, constituting low catalyst loading of tetrakis (triphenylphosphine) palladium under ultrasonic irradiation and a non-inert atmosphere (Scheme 1).

SCHEME 1

(a) Previous synthetic routes. (b) Our synthetic strategy.

Results and discussion

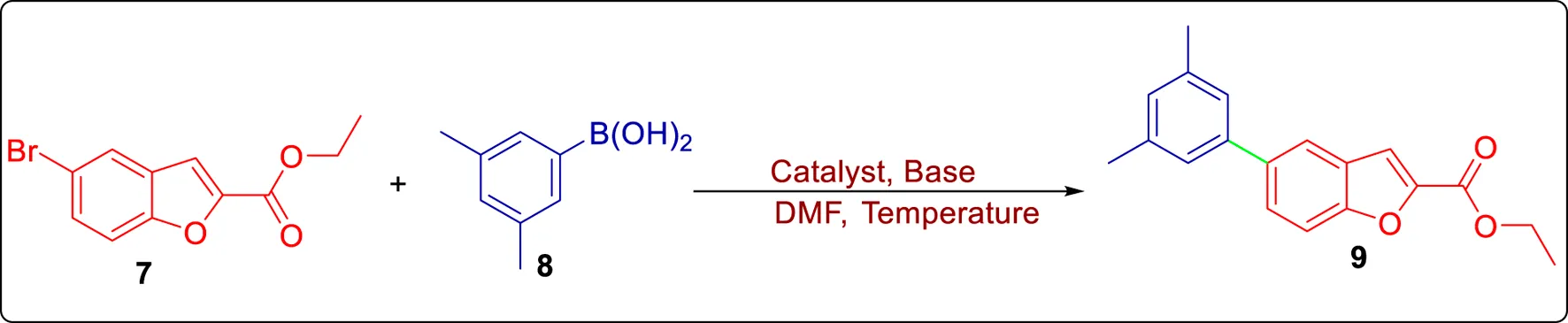

The 5-bromo-substituted benzofuran-based ester was synthesized using the reported protocol (Faiz et al., 2019). The synthesized halogenated ester 7 was employed in a model Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction with 3,5-dimethyl benzene boronic acid 8 using several palladium-based catalysts in the presence of different bases. The optimization of reaction conditions was carried out by varying the Pd catalyst and bases under conventional heating and ultrasonication irradiation in dimethylformamide (DMF). Initially, the Suzuki reaction was investigated using palladium (II) acetylacetone (Pd (acac)2) and aqueous sodium carbonate (base) under conventional conditions, which gave the resulting coupled molecule 9 in 10% yield (Table 1, entry 1). The reaction was repeated at 90 °C using potassium phosphate as a base, which was found to diminish the yield of target molecule 9 (8%). Similarly, utilization of tris(dibenzylideneacetone)dipalladium (0) (Pd2 (dba)3) as a catalyst employing different bases (aq. Na2CO3 and Cs2CO3) at 80 °C and 60 °C (respectively) afforded the target molecule 9 in 50% and 30% yield (Table 1, entries 3 & 4). It was observed that the Suzuki reaction carried out using aqueous sodium carbonate afforded a relatively better yield (50%) of the target molecule in a shorter duration (6 h) than the one obtained by using cesium carbonate, which afforded a 30% yield of product in 8 h. However, when the same reaction was carried out under ultrasonic conditions using aq. Na2CO3, 50% yield of target molecule 9 was obtained in relatively less time (4 h) (Table 1, entry 5). The catalytic effects of [1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene]dichloropalladium (II) (Pd (dppf)Cl2) and bis(triphenylphosphine)palladium (II) dichloride (PdCl2(PPh3)2) were also explored by employing two different bases using conventional and ultrasonication conditions. A Pd (dppf)Cl2-promoted and ultrasonic-assisted Suzuki reaction involving aqueous sodium carbonate/aqueous potassium carbonate afforded target molecule 9 in 52% and 55% yields, respectively (Table 1, entries 6 and 8). A Pd (dppf)Cl2 catalyst in the presence of aqueous sodium carbonate and potassium carbonate (base) at 25 °C furnished the target molecule 9 in 48% and 52% yields, respectively (Table 1, entries 7 and 9). The PdCl2(PPh3)2-catalyzed model reaction carried out by employing sodium carbonate resulted in a relatively higher yield (60%) of the targeted product 9 than the reaction carried out in aqueous potassium carbonate (53%) (Table 1, entries 10 and 11). Repeating the same reaction under ultrasonic irradiations harnessing aq. Na2CO3 furnished a higher yield (67%) of product 9 in a relatively shorter duration of 2 h (Table 1, entry 12). The catalytic efficiency of tetrakis (triphenylphosphine)palladium (0) (Pd(PPh3)4) was also investigated under ultrasonication conditions using these two bases. It was observed that the use of 5 mol% of this catalyst in the model reaction and using aqueous sodium carbonate as a base resulted in a remarkable yield of 92% of the targeted molecule 9 (Table 1, entry 13). Meanwhile, employment of potassium carbonate within a Pd(PPh3)4-mediated model reaction diminished the yield of coupled product 9 i.e., 85%. (Table 1, entry 14), thereby indicating the use of the Pd(PPh3)4 catalyst, aq. Na2CO3, and ultrasonic irradiation as the best optimized conditions for the studied reaction.

TABLE 1

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sr. no. | Catalyst | Base | Temperature (oC) | Time (h) | Yield (%) |

| 1 | Pd (acac)2 | Aq. K2CO3a | 80 | 6 | 10 |

| 2 | Pd (acac)2 | K3PO4a | 90 | 6 | 8 |

| 3 | Pd2 (dba)3 | Aq. Na2CO3a | 80 | 6 | 50 |

| 4 | Pd2 (dba)3 | Cs2CO3a | 60 | 8 | 30 |

| 5 | Pd2 (dba)3 | Aq. Na2CO3b | 80 | 4 | 50 |

| 6 | Pd (dppf)Cl2 | Aq. Na2CO3b | 80 | 4 | 52 |

| 7 | Pd (dppf)Cl2 | Aq. Na2CO3a | 25 | 5.5 | 48 |

| 8 | Pd (dppf)Cl2 | Aq. K2CO3b | 80 | 4 | 55 |

| 9 | Pd (dppf)Cl2 | Aq. K2CO3a | 25 | 6 | 52 |

| 10 | PdCl2(PPh3)2 | Aq. Na2CO3a | 80 | 4 | 60 |

| 11 | PdCl2(PPh3)2 | Aq. K2CO3a | 80 | 6 | 53 |

| 12 | PdCl2(PPh3)2 | Aq. Na2CO3b | 80 | 2 | 67 |

| 13 | Pd(PPh3)4 | Aq. Na2CO3b | 80 | 2 | 92 |

| 14 | Pd(PPh3)4 | Aq. K2CO3b | 80 | 2 | 85 |

Reaction conditions: 7 (1 mmol), 8 (1 mmol), dimethylformamide (DMF), solvent, conventional heating/stirring.

Ultrasound-assisted protocol.

Under optimized conditions, the SMC reaction was carried out by treating aryl halide 7 with substituted aryl boronic acids 8 to attain coupled product 9 in an efficient yield of 92%. The obtained biaryl was further made to react with hydrazine monohydrate in methanol to afford the respective benzohydrazide 10 in a remarkable yield of 95%. The benzohydrazide then underwent reaction with phenylisothiocyanate in dichloromethane (DCM), followed by base-mediated cyclization to furnish the corresponding triazole framework 11 in a 77% yield (Scheme 2) (Zahoor et al., 2024b).

SCHEME 2

Utilization of optimized reaction conditions within the synthetic pathway to access the arylated benzofuran-triazole framework.

The substituted phenylacetamides (prepared by treating substituted anilines with bromoacetyl bromide) (Irfan et al., 2022) were further treated with the benzofuran-based triazole framework 11 by employing potassium carbonate and potassium iodide in DCM. In this way, this synthetic strategy resulted in the generation of novel arylated benzofuran-triazole hybrids 13(a-i) in a good to efficient yield range (72%–90%) (Scheme 3).

SCHEME 3

Substrate scope for the synthesis of arylated benzofuran-triazole hybrids 13(a–i).

Diversely substituted phenyl acetamides were treated to determine the substrate scope of the synthetic protocol. All of the target molecules were obtained successfully. The analysis of synthesized compounds with their respective yields revealed the potential influence of electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups on the yield of targeted derivatives. The electron-donating substituents (Me, OMe, and n-Bu) bearing derivatives 13a, 13b, 13e, and 13f were attained in 70%–78% yield. Meanwhile, the electron-withdrawing substituents (NO2, Cl, and F) bearing derivatives 13(c, g-i) were attained in better yields (80%–92%). However, the 2-methyl 5-nitro substituted hybrid 13d was achieved in 77% yield (Scheme 3).

All of the synthesized derivatives were structurally characterized by several spectroscopic techniques, including NMR spectroscopy (1H-NMR and 13C-NMR) and mass spectrometric analysis. In the 1H-NMR spectrum of the 2,4-dimethyl substituted derivative 13a, the two singlets at 2.26 ppm and 2.34 ppm correspond to the methyl protons of 13a. In addition, the singlet peak of two protons at 4.33 ppm arises as a result of -CH2 attached to the sulfur atom. The singlet at 6.71 ppm corresponds to the signal of furan-H. The aromatic protons gave signals in the range of 6.98–7.69 ppm. In addition, -NH gave a singlet signal at 9.55 ppm. For the 13C-NMR spectrum, the characteristic aliphatic carbon signals were found at 17.9 ppm, 21.1 ppm, 21.3 ppm, and 36.0 ppm. In addition, the carbon signal of the carbonyl carbon was observed at 166.5 ppm. Furthermore, an [M + H]+ peak was observed at 559.0 via mass spectrometry analysis, and the found value was significantly close to the theoretical value. The structural characterization of all compounds was carried out in a similar manner.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and instruments

All the requisite precursors, chemical reagents, and solvents were purchased from Macklin (China, Shanghai Pudong New Area) and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). These analytical-grade chemicals and solvents were used to carry out the synthetic protocol without additional purification. Thin-layer chromatography was carried out at each step to analyze the progress of the reaction. The melting points (mp) of synthesized compounds were obtained via a WRS-1B melting point apparatus, which have been used uncorrected. 13C-NMR spectra and 1H-NMR spectra of synthesized hybrids were obtained via a Bruker spectrophotometer run at 100 MHz/400 MHz and 400 MHz/600 MHZ, respectively. Deuterated chloroform and dimethyl sulfoxide were used for solubility, and tetramethyl silane (TMS) was employed as an internal standard. MestReNova software was used to interpret the spectral details.

Synthesis of compounds 13 (a–i)

The synthesized benzofuran-endowed aryl halide 7 (1 mmol) and substituted boronic acid 8 (1 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (5 mL). After 30 min of room temperature stirring, Pd(PPh3)4 (5 mol%) and 1 M Na2CO3 solution (5.5 mL) were added to the reaction mixture, which was subjected to ultrasonication for approximately 90–120 min. After indication of completion of reaction by thin layer chromatography, solvent extraction was performed with ethyl acetate and water, followed by drying the moisture content in the organic layer via anhydrous Na2SO4. Column chromatography (n-hexane:ethyl acetate 99:1) of the concentrated organic layer was then performed to obtain the pure product 9. The biaryl 9 was then used as precursor to synthesize the novel arylted benzofuran-triazole conjugates 13(a-i) via reported protocol (Zahoor et al., 2024b).

13a, White powder; 70%; mp 217–219 °C; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 9.55 (s, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 16 Hz, 5H), 7.54 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (d, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 7.14 (s, 2 H), 6.98 (s, 3H), 6.71 (s, 1H), 4.33 (s, 2H), 2.34 (s, 9H), 2.26 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 166.5, 154.3, 140.8, 142.5, 141.7, 138.3, 138.3, 137.6, 136.1, 135.1, 132.7, 131.1, 130.4, 130.4, 130.4, 130.2, 128.8, 127.6, 127.3, 127.3, 127.3, 126.1, 125.7, 125.2, 125.2, 125.2, 122.9, 120.0, 111.7, 108.2, 36.0, 21.3, 21.1, 17.9. MS (m/z): 559.0 [M+ + H]. Elem. Anal. Calc. for C34H30N4O2S: C, 73.09; H, 5.41; N, 10.03. Found: C, 73.07; H, 5.39; N, 10.07.

13b, Off-white powder; 71%; mp 170–172 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 9.61 (s, 1H), 7.76 (s, 1H), 7.63-7.61 (m, 1H), 7.53-7.51 (m, 2H), 7.45 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 8 Hz, 3H), 7.14 (s, 2H), 7.03 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (s, 1H), 6.84 (d, J = 4 Hz, 2H), 6.50 (s, 1H), 4.09 (s, 2H), 2.34 (s, 9H), 2.29 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 166.5, 154.3, 140.8, 138.3, 138.3, 137.6, 136.1, 132.7, 131.1, 130.4, 130.4, 130.4, 130.4, 130.2, 128.8, 127.3, 127.3, 127.3, 127.3, 126.1, 125.7, 125.2, 125.2, 125.2, 125.2, 122.9, 120.0, 111.7, 108.2, 36.0, 21.3, 21.1, 21.1, 17.9. MS (m/z): 559.0 [M+ + H]. Elem. Anal. Calc. for C34H30N4O2S: C, 73.09; H, 5.41; N, 10.03. Found: C, 73.07; H, 5.45; N, 10.05.

13c, White solid; 80%; mp 175–177 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 10.99 (s, 1H), 8.67 (s, 1H), 7.89-7.83 (m, 2H), 7.66-7.60 (m, 5H), 7.51-7.49 (m, 1H), 7.41-7.38 (m, 4H), 7.09 (s, 2H), 6.93 (s, 1H), 4.15 (s, 2H), 2.30 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) 166.7, 157.5, 155.5, 155.3, 154.4, 154.0, 152.7, 147.6, 147.3, 143.5, 143.0, 140.4, 138.3,138.3, 136.9, 130.7, 130.2, 129.6, 129.4, 129.0, 128.1, 128.1, 127.7, 125.2, 125.2, 120.4, 113.6, 111.9, 107.7, 55.3, 37.2, 21.4. MS (m/z): 576.0 [M+ + H]. Elem. Anal. Calc. for C32H25N5O4S: C, 66.77; H, 4.38; N, 12.17. Found: C, 66.79; H, 4.42; N, 12.19.

13d, Off-white solid; 77%; mp 156–158 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 10.29 (s, 1H), 8.98 (s, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.43-7.66 (m, 8H), 7.30 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (s, 2H), 6.97 (s, 1H), 6.49 (s, 1H), 4.14 (s, 2H), 2.56 (s, 3H), 2.35 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 166.8, 154.4, 148.3, 146.6, 142.1, 140.7, 138.3, 138.3, 137.7, 137.1, 136.2, 132.5, 131.4, 130.8, 130.5, 130.5, 130.5, 128.8, 127.5, 127.2, 126.4, 125.2, 125.2, 125.2, 120.1, 119.2, 116.7, 111.7, 108.6, 36.12, 21.3, 21.3, 19.0. MS (m/z): 589.9 [M+]. Elem. Anal. Calc. for C33H27N5O4S: C, 67.22; H, 4.62; N, 11.88. Found: C, 67.28; H, 4.66; N, 11.86.

13e, White powder; 78%; mp 152–154 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 10.13 (s, 1H), 7.67-7.59 (m, 5H), 7.54 (t, J = 8 Hz, 3H), 7.46 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.15 (s, 1H), 6.97 (s, 1H), 6.83 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 6.43 (s, 1H), 3.97 (s, 2H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 2.34 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 166.0, 165.9, 156.3, 154.4, 154.3, 142.7, 140.9, 138.3, 137.6, 132.8, 131.4, 131.2, 130.4, 130.4, 129.2, 128.7, 127.6, 127.3, 127.2, 126.1, 125.2, 124.3, 121.3, 120.0, 114.0, 113.2, 111.7, 107.9, 106.8, 55.4, 36.0, 21.3, 21.3. MS (m/z): 561.0 [M+ + H]. Elem. Anal. Calc. for C33H28N4O3S: C, 70.69; H, 5.03; N, 9.99. Found: C, 70.71; H, 5.07; N, 9.97.

13f, White solid; 75%; mp 191–193 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 10.19 (s, 1H), 7.62-7.38 (m, 10H), 7.15-7.09 (m, 4H), 6.96 (s, 1H), 6.44 (s, 1H), 3.98 (s, 2H), 2.54 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 2.34 (s, 6 H), 1.56-1.24 (m, 4H), 0.89 (t, J = 6 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 166.1, 154.4, 148.2, 142.7, 140.9, 138.9, 138.3, 138.3, 137.6, 135.8, 132.8, 131.1, 130.4, 130.4, 128.7, 128.7, 127.6, 127.3, 127.3, 126.1, 125.2, 125.2, 125.2, 120.0, 119.7, 119.7, 119.6, 111.7, 107.9, 36.1, 35.0, 33.6, 22.2, 21.3, 21.3, 13.9. MS (m/z): 587.0 [M+ + H]. Elem. Anal. Calc. for C36H34N4O2S: C, 73.69; H, 5.84; N, 9.55. Found: C, 73.73; H, 5.86; N, 9.57.

13g, Off-white powder; 88%; mp 216–218 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 9.87 (s, 1H), 8.30 (d, J = 12 Hz, 1H), 7.34-7.62 (m, 10H), 7.14 (s, 2H), 7.02 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (s, 1H), 6.50 (s, 1H), 4.12 (s, 2H), 2.34 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 154.3, 153.4, 148.4, 142.9, 140.9, 138.2, 138.2, 137.5, 134.9, 132.9, 131.0, 130.3, 130.3, 129.3, 128.7, 127.6, 127.3, 127.3, 127.3, 127.3, 127.3, 125.9, 125.2, 125.2, 125.0, 124.1, 122.2, 119.9, 111.7, 107.8, 35.8, 21.3. MS (m/z): 564.9 [M+]. Elem. Anal. Calc. for C32H25ClN4O24S: C, 68.02; H, 4.46; N, 9.91. Found: C, 68.06; H, 4.42; N, 9.95.

13h, Off-white powder; 79%; mp 224–226 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 10.49 (s, 1H), 7.67-7.59 (m, 7H), 7.55-7.47 (m, 2H), 7.39 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.27 (s, 1H), 7.15 (s, 2H), 6.97 (s, 1H), 6.44 (s, 1H), 3.96 (s, 2H), 2.34 (s, 6 H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 166.4, 154.4, 151.2, 150.5, 150.2, 149.4, 148.8, 148.8, 142.5, 140.8, 138.3, 137.6, 136.8, 135.8, 134.2, 132.7, 131.2, 130.4, 128.9, 128.8, 127.2, 126.2, 125.2, 120.9, 120.0, 111.7, 110.1, 110.1, 108.0, 36.0, 21.3, 21.3. MS (m/z): 564.9 [M+]. Elem. Anal. Calc. for C32H25ClN4O2S: C, 68.02; H, 4.46; N, 9.91. Found: C, 68.04; H, 4.48; N, 9.95.

13i, Off-White solid; 92%; mp 253–255 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 10.45 (s, 1H), 7.67-7.61 (m, 6H), 7.54 (d, J = 8, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 4 Hz, 2H), 7.15 (s, 2 H), 7.01-6.97 (m, 3H), 6.47 (s, 1H), 4.01 (s, 2H), 2.34 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 166.1, 160.5, 154.4, 140.8, 138.3, 138.3, 138.3, 137.7, 134.2, 132.6, 131.3, 130.4, 130.4, 130.4, 128.8, 127.5, 127.2, 127.2, 126.3, 125.2, 125.2, 125.2, 121.4, 121.3, 120.1, 115.6, 115.3, 111.7, 108.3, 36.1, 21.3, 21.3. MS (m/z): 549.0 [M+ + H]. Elem. Anal. Calc. for C32H25FN4O2S: C, 70.06; H, 4.59; N, 10.21. Found: C, 70.04; H, 4.57; N, 10.19%.

Conclusion

To conclude, we have developed a facile, additive-free, and convenient protocol for the Suzuki cross-coupling reaction to synthesize substituted biaryls in high yields. The reaction was carried out by treating benzofuran-endowed aryl halide and substituted boronic acids using aq. Na2CO3 and Pd(PPh3)4 under ultrasonic conditions to access the coupling products within a minimum time. Compared to previous studies, the developed protocol has been found to be facile and efficient in terms of reaction conditions, catalyst loading, and product yields, as it does not require an inert atmosphere or the use of additives. The obtained products were efficiently employed as synthetic building blocks to synthesize a novel series of arylated benzofuran-based phenyl acetamides. The merits of the utilized methodology are the facile conversion, short duration, broad substrate scope, non-inert atmosphere, and high yields.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

MS: Project administration, Writing – review and editing, Resources. SA: Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing. AM: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Methodology. SM: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review and editing. AZ: Supervision, Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review and editing. SE: Resources, Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing. AI: Writing – review and editing, Resources. KK-M: Resources, Funding acquisition, Writing – review and editing. KR: Writing – review and editing, Resources. MM: Resources, Funding acquisition, Writing – review and editing, Project administration.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The research was partly financed by the following research projects: Collegium Medicum, The Mazovian Academy in Plock, and the Medical University of Lublin (DS 730).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2025.1726528/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Adlington N. K. Agnew L. R. Campbell A. D. Cox R. J. Dobson A. Barrat C. F. et al (2018). Process design and optimization in the pharmaceutical industry: a suzuki–miyaura procedure for the synthesis of savolitinib. Org. Chem.84, 4735–4747. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b02351

2

Akhtar R. Zahoor A. F. Parveen B. Suleman M. (2019). Development of environmental friendly synthetic strategies for sonogashira cross coupling reaction: an update. Synth. Commun.49, 167–192. 10.1080/00397911.2018.1514636

3

Alza E. Laraia L. Ibbeson B. M. Collins S. Galloway W. R. Stokes J. E. et al (2015). Synthesis of a novel polycyclic ring scaffold with antimitotic properties via a selective domino heck–suzuki reaction. Chem. Sci.6, 390–396. 10.1039/c4sc02547d

4

Amoroso F. Colussi S. Del Zotto A. Llorca J. Trovarelli A. (2011). PdO hydrate as an efficient and recyclable catalyst for the suzuki–miyaura reaction in water/ethanol at room temperature. Catal. Commun.12, 563–567. 10.1016/j.catcom.2010.11.026

5

Bozorov K. Zhao J. Aisa H. A. (2019). 1,2,3-Triazole-containing hybrids as leads in medicinal chemistry: a recent overview. Bioorg. Med. Chem.27, 3511–3531. 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.07.005

6

Brahmachari G. (2016). Design for carbon–carbon bond forming reactions under ambient conditions. RSC Adv.6, 64676–64725. 10.1039/c6ra14399g

7

Brahmachari G. Nayek N. Mandal M. Bhowmick A. Karmakar I. (2021). Ultrasound-promoted organic synthesis - a recent update. Curr. Org. Chem.25, 1539–1565. 10.2174/1385272825666210316122319

8

Cella R. Stefani H. A. (2006). Ultrasound-assisted synthesis of Z and E stilbenes by suzuki cross-coupling reactions of organotellurides with potassium organotrifluoroborate salts. Tetrahedron62, 5656–5662. 10.1016/j.tet.2006.03.090

9

Cintas P. Tagliapietra S. Gaudino E. C. Palmisano G. Cravotto G. (2014). Green Chem.16, 1056. 10.1039/C3GC41955J

10

Cravotto G. Palmisano G. Tollari S. Nano G. M. Penoni A. (2005). The suzuki homocoupling reaction under high-intensity ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem.12, 91–94. 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2004.05.005

11

Cravotto G. Borretto E. Oliverio M. Procopio A. Penoni A. (2015). Organic reactions in water or biphasic aqueous systems under sonochemical conditions. A review on catalytic effects. Catal. Commun.63, 2–9. 10.1016/j.catcom.2014.12.014

12

Czompa A. Pásztor B. L. Sahar J. A. Mucsi Z. Bogdán D. Ludányi K. et al (2019). Scope and limitation of propylene carbonate as a sustainable solvent in the suzuki-miyaura reaction. RSC Adv.9, 37818–37824. 10.1039/c9ra07044c

13

de Souza A. L. F. da Silva L. C. Oliveira B. L. Antunes O. A. C. (2008). Microwave- and ultrasound-assisted suzuki–miyaura cross-coupling reactions catalyzed by Pd/PVP. Tetrahedron Lett.49, 3895–3898. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.04.061

14

Faiz S. Zahoor A. F. Ajmal M. Kamal S. Ahmad S. Abdelgawad A. M. et al (2019). Design, synthesis, antimicrobial evaluation, and laccase catalysis effect of novel benzofuran–oxadiazole and benzofuran–triazole hybrids. J. Heterocycl. Chem.56, 2839–2852. 10.1002/jhet.3674

15

Farhang M. Akbarzadeh A. R. Rabbani M. Ghadiri A. M. (2022). A retrospective-prospective review of suzuki–miyaura reaction: from cross-coupling reaction to pharmaceutical industry applications. Polyhedron227, 116124. 10.1016/j.poly.2022.116124

16

Felpin F. X. Ayad T. Mitra S. (2006). Pd/C: an old catalyst for new applications – its use for the suzuki–miyaura reaction. Eur. J. Org. Chem.2006, 2679–2690. 10.1002/ejoc.200501004

17

Gao X. Lu P. Ma Y. (2014). Ultrasound-assisted suzuki coupling reaction for rapid synthesis of polydihexylfluorene. Polymer55, 3083–3086. 10.1016/j.polymer.2014.05.036

18

Irfan A. Zahoor A. F. Kamal S. Hassan M. Kloczkowski A. (2022). Ultrasonic-assisted synthesis of benzofuran appended oxadiazole molecules as tyrosinase inhibitors: mechanistic approach through enzyme inhibition, molecular docking, chemoinformatics, ADMET and drug-likeness studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 10979. 10.3390/ijms231810979

19

Johansson Seechurn C. C. Kitching M. O. Colacot T. J. Snieckus V. (2012). Palladium‐catalyzed cross‐coupling: a historical contextual perspective to the 2010 nobel Prize. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.51, 5062–5085. 10.1002/anie.201107017

20

Khanam H. Shamsuzzaman (2015). Bioactive benzofuran derivatives: a review. Eur. J. Med. Chem.97, 483–504. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.11.039

21

Kharb R. Sharma P. C. Yar M. S. (2011). Pharmacological significance of triazole scaffold. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem.26, 1–21. 10.3109/14756360903524304

22

Kotha S. Lahiri K. Kashinath D. (2002). Recent applications of the suzuki–miyaura cross-coupling reaction in organic synthesis. Tetrahedron58, 9633–9695. 10.1016/s0040-4020(02)01188-2

23

Li X. Zhang H. Hu Q. Jiang B. Zeli Y. (2018). A simple and mild suzuki reaction protocol using triethylamine as base and solvent. Synth. Commun.48, 3123–3132. 10.1080/00397911.2018.1519075

24

Littke A. F. Dai C. Fu G. C. (2000). Versatile catalysts for the suzuki cross-coupling of arylboronic acids with aryl and vinyl halides and triflates under mild conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc.122, 4020–4028. 10.1021/ja0002058

25

Louvis A. D. R. Silva N. A. Semaan F. S. Da Silva F. D. C. Saramago G. de Souza L. C. et al (2016). Synthesis, characterization and biological activities of 3-aryl-1,4-naphthoquinones – Green palladium-catalysed suzuki cross coupling. J. Chem.40, 7643–7656. 10.1039/c6nj00872k

26

Maegawa T. Kitamura Y. Sako S. Udzu T. Sakurai A. Tanaka A. et al (2007). Heterogeneous Pd/C‐Catalyzed ligand‐free, room‐temperature suzuki–miyaura coupling reactions in aqueous media. Chem. Eur. J.13, 5937–5943. 10.1002/chem.200601795

27

Mai S. Li W. Li X. Zhao Y. Song Q. (2019). Palladium-catalyzed suzuki-miyaura coupling of thioureas or thioamides. Nat. Commun.10, 5709. 10.1038/s41467-019-13701-5

28

Mason T. J. (1997). Ultrasound in synthetic organic chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev.26, 443. 10.1039/cs9972600443

29

Miyaura N. (1998). 6, 187–243.

30

Miyaura N. Suzuki A. (1979). Stereoselective synthesis of arylated (E)-alkenes by the reaction of alk-1-enylboranes with aryl halides in the presence of palladium catalyst. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun.866, 866. 10.1039/c39790000866

31

Miyaura N. Suzuki A. (1995). Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of organoboron compounds. Chem. Rev.95, 2457–2483. 10.1021/cr00039a007

32

Miyaura N. Yamada K. Suzuki A. (1979). A new stereospecific cross-coupling by the palladium-catalyzed reaction of 1-alkenylboranes with 1-alkenyl or 1-alkynyl halides. Tetrahedron Lett.20, 3437–3440. 10.1016/s0040-4039(01)95429-2

33

Mushtaq A. Zahoor A. F. Ahmad M. N. Khan S. G. Akhter N. Nazeer U. et al (2024). Accessing the synthesis of natural products and their analogues enabled by the barbier reaction: a review. RSC Adv.14, 33536–33567. 10.1039/d4ra05646a

34

Nagalakshmi V. Sathya M. Premkumar M. Kaleeswaran D. Venkatachalam G. Balasubramani K. (2020). Palladium(II) complexes comprising naphthylamine and biphenylamine based schiff base ligands: synthesis, structure and catalytic activity in suzuki coupling reactions. J.Organometal. Chem.914, 121220. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2020.121220

35

Nevagi R. J. Dighe S. N. Dighe S. N. (2015). Biological and medicinal significance of benzofuran. Eur. J. Med. Chem.97, 561–581. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.10.085

36

Nobre S. M. Cavalheiro V. M. Duarte L. S. (2018). Synthesis of brominated bisamides and their application to the suzuki coupling. J. Mol. Struct.1171, 594–599. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.05.103

37

Ortega-Gaxiola J. I. Valdés H. Rufino-Felipe E. Toscano R. A. Morales-Morales D. (2020). Inorg. Chim. Acta504, 119460. 10.1016/j.ica.2020.119460

38

Panahi L. Naimi-Jamal M. R. Mokhtari J. (2018). Ultrasound-assisted suzuki-miyaura reaction catalyzed by Pd@Cu2(NH2-BDC)2(DABCO). J. Organomet. Chem.868, 36–46. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2018.04.038

39

Polshettiwar V. Decottignies A. Len C. Fihri A. (2010). Suzuki-miyaura cross-coupling reactions in aqueous media: green and sustainable syntheses of biaryls. ChemSusChem Chem. and Sustain. Energy and Mater.3, 502–522. 10.1002/cssc.200900221

40

Rao X. Liu C. Zhang Y. Gao Z. Jin Z. (2014). Pd/C-catalyzed ligand-free and aerobic suzuki reaction in water. Chin. J. Catal.35, 357–361. 10.1016/s1872-2067(12)60754-2

41

Sancheti S. V. Gogate P. R. (2018). Intensification of heterogeneously catalyzed suzuki-miyaura cross-coupling reaction using ultrasound: understanding effect of operating parameters. Ultrason. Sonochem.40, 30–39. 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.01.037

42

Sarkar P. Ahmed A. Ray J. K. (2020). Suzuki cross coupling followed by cross dehydrogenative coupling: an efficient one pot synthesis of phenanthrenequinones and analogues. Tetrahedron Lett.61, 151701. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2020.151701

43

Sonogashira K. (1998). Weinheim: Wiley VCH, 203–229.

44

Stanforth S. P. (1998). Catalytic cross-coupling reactions in biaryl synthesis. Tetrahedron54, 263–303. 10.1016/s0040-4020(97)10233-2

45

Suzuki A. (1999). Recent advances in the cross-coupling reactions of organoboron derivatives with organic electrophiles, 1995–1998. J. Organomet. Chem.576, 147–168. 10.1016/s0022-328x(98)01055-9

46

Suzuki A. (2002). Cross-coupling reactions via organoboranes. J. Organometal. Chem.653, 83–90. 10.1016/s0022-328x(02)01269-x

47

Suzuki A. Yamamoto Y. (2011). Cross-coupling reactions of organoboranes: an easy method for C–C bonding. Chem. Lett.40, 894–901. 10.1246/cl.2011.894

48

Taheri Kal Koshvandi A. Heravi M. M. Momeni T. (2018). Current applications of suzuki–miyaura coupling reaction in the total synthesis of natural products: an update. Appl. Organomet. Chem.32, e4210. 10.1002/aoc.4210

49

Thunga S. Poshala S. Anugu N. Konakanchi R. Vanaparthi S. Kokatla H. P. (2019). An efficient Pd(II)-(2-aminonicotinaldehyde) complex as complementary catalyst for the suzuki-miyaura coupling in water. Tetrahedron Lett.60, 2046–2048. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2019.06.051

50

Wang C. Kilitziraki M. Pålsson L. O. Bryce M. R. Monkman A. P. Samuel I. D. W. (2001). Adv. Funct. Mater.11, 47. 10.1002/1616-3028(200102)11:1<47::AID-ADFM47>3.0.CO;2-T

51

Zahoor A. F. Parveen B. Javed S. Akhtar R. Tabassum S. (2024a). Recent developments in the chemistry of negishi coupling: a review. Chem. Pap.78, 3399–3430. 10.1007/s11696-024-03369-7

52

Zahoor A. F. Munawar S. Ahmad S. Iram F. Anjum M. N. Khan S. G. et al (2024b). Design, synthesis and biological exploration of novel N-(9-Ethyl-9H-Carbazol-3-yl)Acetamide-Linked Benzofuran-1,2,4-Triazoles as Anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents: combined wet/dry approach targeting main protease (mpro), spike glycoprotein and RdRp. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25, 12708. 10.3390/ijms252312708

53

Zhang D. Wang Q. (2015). Palladium catalyzed asymmetric suzuki–miyaura coupling reactions to axially chiral biaryl compounds: chiral ligands and recent advances. Coord. Chem. Rev.286, 1–16. 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.11.011

54

Zheng M. M. Wang L. Huang F. H. Guo P. M. Wei F. Deng Q. C. et al (2013). Ultrasound irradiation promoted lipase-catalyzed synthesis of flavonoid esters with unsaturated fatty acids. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym.95, 82–88. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2013.05.028

Summary

Keywords

Suzuki reaction, Pd(PPh3)4, ultrasound, arylated benzofuran-triazole hybrids, heterocycles

Citation

Saif MJ, Ahmad S, Mushtaq A, Munawar S, Zahoor AF, Ettampola S, Irfan A, Kotwica-Mojzych K, Ruszel K and Mojzych M (2025) Ultrasonic-assisted, additive-free Pd-catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling enabled synthesis of novel arylated benzofuran-triazole hybrids. Front. Chem. 13:1726528. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2025.1726528

Received

16 October 2025

Revised

10 November 2025

Accepted

11 November 2025

Published

10 December 2025

Volume

13 - 2025

Edited by

Hitendra M. Patel, Sardar Patel University, India

Reviewed by

Ivan Damljanović, University of Kragujevac, Serbia

Jovana Bugarinovic, University of Kragujevac, Serbia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Saif, Ahmad, Mushtaq, Munawar, Zahoor, Ettampola, Irfan, Kotwica-Mojzych, Ruszel and Mojzych.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ameer Fawad Zahoor, fawad.zahoor@gcuf.edu.pk; Mariusz Mojzych, m.mojzych@mazowiecka.edu.pl

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.