- 1Department of Engineering and Management, Munich University of Applied Sciences HM, Munich, Germany

- 2Department of Applied Sciences and Mechatronics, Munich University of Applied Sciences HM, Munich, Germany

- 3Wacker Chemie AG, Burghausen, Germany

The drying of bacteria using various methods is a widely used technique for long-term stabilization across different applications. For organisms capable of producing the enzyme urease, which are used in microbial induced carbonate precipitation (MICP), drying may also offer promising new fields for application. In the present study, two drying methods, fluidized bed drying and freeze-drying, were applied to Sporosarcina pasteurii, both with and without the commonly used cryoprotectant maltodextrin. The dried samples were evaluated in terms of cell viability, storage stability (based on urease activity) at three different temperatures (room temperature, 4

1 Introduction

The formation of calcium carbonate precipitation caused by various microorganisms is well researched and commonly referred to as microbial induced carbonate precipitation (MICP). These microorganisms are capable of precipitating calcium carbonate (CaCO3), such as bacterial Baidya et al. (2023) or fungal Devgon et al. (2024) organisms. However, the bacterium Sporosarcina pasteurii is commonly preferred for the biocementation process, due to its outstanding ability to produce large amounts and high-quality

When working with MICP, the largest portion of current research and applications utilize liquid cultures that are cultivated immediately before their use. The storage of liquid cultures of S. pasteurii under different conditions (25

As an alternative to the liquid cultures, dried bacteria or enzymes can also be used for MICP applications. Dried bacteria can offer many advantages compared to liquid cultures, such as longer storage stability, require less storage or transport volume, and can also be stored at moderate temperatures Peiren et al. (2015). There are already several drying methods for microorganisms that are well established in other areas of application. The most important and widely known drying techniques for bacteria include freeze-drying (lyophilization), spray drying, fluidized bed drying, and vacuum drying Broeckx et al. (2016); Tan et al. (2018). Lactic acid bacteria are frequently dried due to their importance in the food industry, making them the primary focus of research on microorganism drying Morgan et al. (2006); Santivarangkna et al. (2007). During the process of freeze-drying, cells are first frozen and then dehydrated by sublimating the frozen moisture under high vacuum conditions. The process of fluidized bed drying often requires a carrier material, such as microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), which has been demonstrated to support the drying of different organisms Son et al. (2022). In general, the drying process removes physically bound and unbound water from cells. Furthermore, physiological reactions and the metabolism are inhibited or inactivated, respectively. For instance, different bacteria, such as Enterococcus faecium M74 Stummer et al. (2012), Lactobacillus plantarum Bensch et al. (2014); Strasser et al. (2009), Lactobacillus reuteri Schell and Beermann (2014), Lactobacillus lactis 1464 Wirunpan et al. (2016), and E. faecium Strasser et al. (2009), have been successfully dried using fluidized bed drying.

To achieve a higher cell viability, a lot of different cryoprotectants can be used to protect the cells during the drying process and the storage period. Different types of sugar, such as maltodextrin or sucrose (Oluwatosin et al. (2022); Bensch et al. (2014); Wang et al. (2020), are often used as they enhance desiccation tolerance by stabilizing membranes and proteins, replacing water around polar residues in macromolecular structures Morgan et al. (2006). It is also possible to use (skim) milk powder Ge et al. (2024); Oluwatosin et al. (2022); Wang et al. (2020), as proteins may play a more critical role than sugars in desiccation protection, which could explain the effectiveness of protein-rich substances. Instead of relying on active bacterial cells in liquid, a promising approach involves the application of bacterial spores. For example, S. pasteurii was utilized to enhance the thermal stability and flame resistance of cellulose aerogels, containing bacteria and yeast, through calcium carbonate biomineralization Jones and Srubar (2022). Further innovations include the immobilization of microorganisms or spores on various materials to enhance their application. Examples include immobilization on aggregates Khushnood et al. (2020), mixtures of metakaolin and sodium silicate Jadhav et al. (2018), or perlite Jiang et al. (2020); Alazhari et al. (2018), often used in self-healing systems alongside nutrients and protective layers. Clay particles were also used as carriers for immobilized microorganisms, which are used for MICP Wiktor and Jonkers (2011). Additionally, direct mixing of MICP microorganisms with cement has been explored Jonkers et al. (2010), as well as microencapsulation techniques using spray drying, freeze-drying, or extrusion Pungrasmi et al. (2019). These microencapsulation methods help in protecting the microorganisms while facilitating their activation when conditions are favourable Xu et al. (2024); Wang et al. (2014).

It has already been shown that the organism S. pasteurii used in the present study can be dried using different methods for various purposes. The organism was freeze-dried for SEM analysis to determine bacterial characteristics (morphology structure such as length and width) Chen et al. (2021); Fu et al. (2022) or for long-term storage and sale of small quantities for strain preservation, allowing the organism to be cultivated in liquid media again Kahani et al. (2020); Li et al. (2023); Omoregie et al. (2020); Røyne et al. (2019). There is also literature in which lyophilised MICP-compatible bacterial cells, including S. pasteurii, have been reused for various MICP applications. Terzis and Laloui (2018) and Terzis and Laloui (2019) produced freeze-dried S. pasteurii samples and subsequently tested them with varying biomass and urea concentrations to evaluate their functionality for MICP applications in sand with different properties. Similar results were shown by Tuttle et al. (2025), which also used freeze-dried S. pasteurii and investigated viability and MICP performance in sand columns and field applications. Valencia-Galindo et al. (2021) compared MICP capable freeze-dried powder with freshly cultivated bacteria, in which the fresh bacteria deliver better results. Furthermore, Fu et al. (2022) prepared microbial healing agents by drying S. pasteurii spores at 40

There is currently a gap in literature regarding the investigation of different drying methods without and with sugar-based protectants and the following use of the cells for MICP applications. Although some studies have explored the drying and reuse of bacteria for MICP applications, no systematic, direct comparison between freeze-drying and fluidized bed drying has been reported. In particular, their effects on the viability of vegetative S. pasteurii cells, the role of sugar-based protectants such as maltodextrin, and their subsequent performance in soil stabilization remain unexamined. Therefore, the research objectives of the present study are to introduce a new approach by directly comparing two of the most commonly used drying methods for microorganisms: freeze-drying, which is widely used for drying microorganisms, and fluidized bed drying, which is considered to be very gentle due to its moderate drying temperatures in comparison to spray drying. The study also evaluates the effects of maltodextrin under these conditions on S. pasteurii. In addition, the long-term storage stability of the dried bacteria over 90 days and their subsequent use in soil stabilization will be investigated, an aspect that has not been studied in previous research.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Cultivation and preparation of Sporosarcina pasteurii

The used bacterium S. pasteurii DSM 33 was cultivated in parallel bioreactors (Bioengineering AG, RALF Plus-System) with a working volume of 2.5 L. To collect enough bacterial biomass, three reactors were harvested for the fluidized bed drying and one for the freeze-drying experiments. For the reactors, the

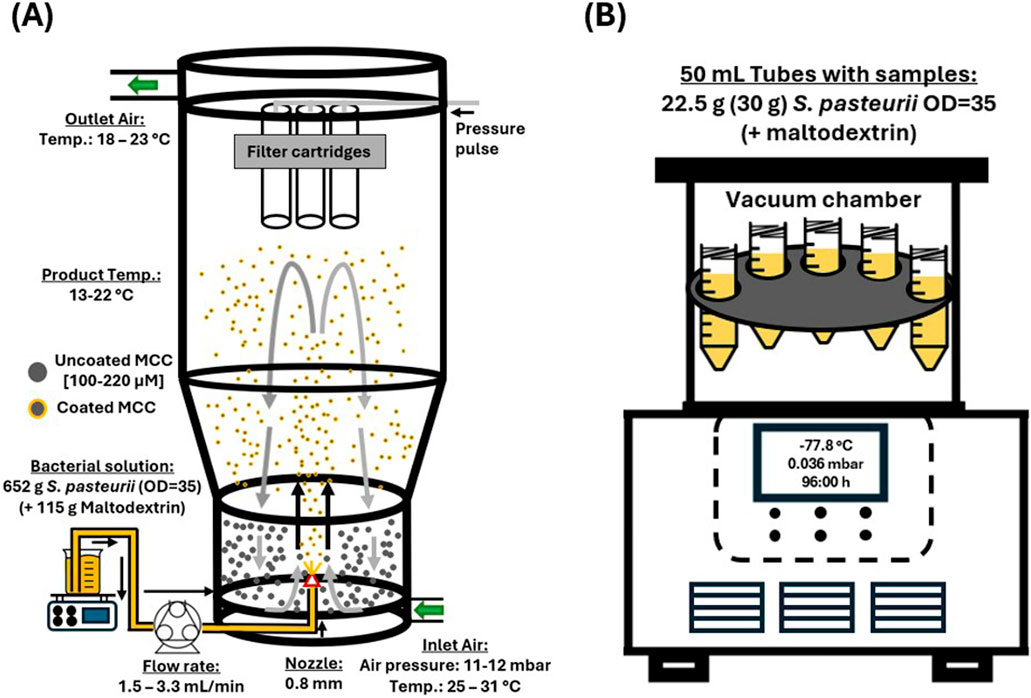

2.2 Fluidized bed drying

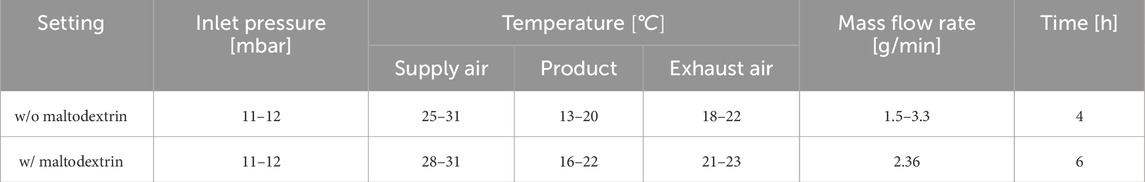

For fluidized bed drying, a laboratory fluidized bed processor (DMR Prozesstechnologie GmbH, WFP-Mini) was used. The complete test setup is shown in Figure 1A. The S. pasteurii cells produced in accordance with Section 2.1 were sprayed into the reactor chamber using a spray lance (25 mm) with a 0.8 mm nozzle and an air flow of 100% nitrogen. A total of 652 g of bacterial suspension with an

Figure 1. Graphical illustration of the two different drying methods for Sporosarcina pasteurii used in the present study, fluidized bed drying (A) and freeze-drying (B). The illustration for the freeze-drying is based on Taskin (2020).

At the beginning of the experiment, the three filter cartridges (Type KE 2671 Ti07/1–0.13 V4A FRV Ø 75 mm x L 200 mm) of the fluidized bed dryer were examined for adhesions during the drying process. For this, the experiment was briefly stopped, and the fluidized bed reactor was opened. The drying process was completed once the entire bacterial suspension had been transported into the fluidized bed drying reactor. Afterwards, the resulting powder was dried for 30–45 min with the same settings but without the addition of bacterial suspension, hereinafter referred as post-drying. Afterwards, the powder was transferred into 50 mL tubes and used for the upcoming experiments, described in Section 2.4 and 2.5.

2.3 Freeze-drying

For the freeze-drying of the bacterial suspension prepared according to Section 2.1, a laboratory system (ZIRBUS technology GmbH, VaCo 2, −80

2.4 Imaging and SEM

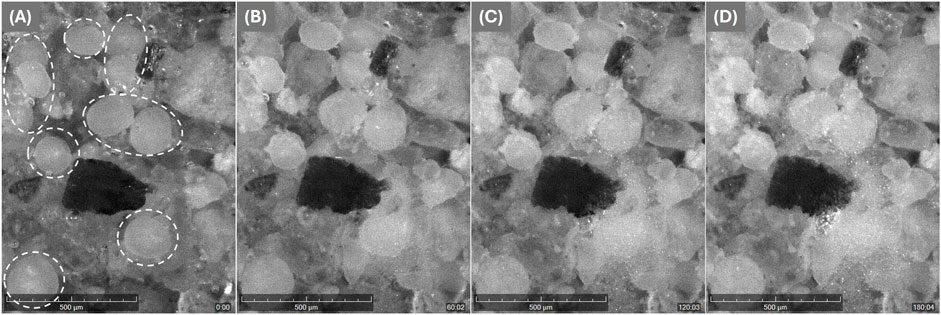

For the real-time observation of particle imaging during calcium carbonate precipitation, an analytical imaging instrument was used (Technobis Crystallization Systems, Crystalline). Therefore, quartz sand and powder without the maltodextrin was mixed and filled into a 20 mL glass vial. After the vial was placed in the device and the camera focused, cementation solution was filled in. Then the experiment was started at 30

2.5 Analysis of dried bacteria

To compare the two different drying methods in terms of particle distribution, cell viability after the drying process, and final application after rehydration for MICP, identical experiments were conducted for both types of resulting powders.

2.5.1 Weight, particle distribution and residual moisture

After the drying process, the total weight of each powder was measured directly with a scale (Mettler-Toledo GmbH, XS6002-S DR). Afterwards, about 2 g of the dried powder was used to analyse the particle distribution via laser scattering (HORIBA Europe GmbH, LA-960), and 2.5 g were weighed and heated at 105

2.5.2 Cell viability

In the present study, the viability of S. pasteurii cells was determined, where cell viability refers to their ability to form colony-forming units (CFUs), similar to Stummer et al. (2012); Ge et al. (2024). To analyse the cell viability of S. pasteurii after the different drying procedures, 5 g of each powder were transferred in 15 mL tubes and filled up with 9 g/L NaCl solution. To detach the cells from the carrier or to rehydrate them, the tubes were shaken in horizontal position on an incubator shaker for 1 h at 150 rpm (shaking diameter 20 mm). The tubes were stored for 5 min to allow the MCC to settle. Afterwards, 2 mL of the supernatant from the top were decanted and transferred in 2 mL tubes. The cells were washed with 9 g/L NaCl by centrifugation at 9,614 rcf for 30 min (Hermle Labortechnik GmbH, Z233 MK-2) and the cell pellet was resuspended in fresh 9 g/L NaCl solution to remove the maltodextrin and other substances from the bacterial cells. From this suspension, the

2.5.3 Storage

To identify the influence of storage time on the different powders up to 92 days at three different temperatures, the powders were split in three settings. Therefore, the powders were transferred into 50 mL tubes and stored in the laboratory at room temperature, in the refrigerator at 4

2.5.4 Usage for MICP

After the storage period of 92 days, the different powders were tested for the process of MICP at room temperature in quartz sand columns. Therefore, the quartz sand was mixed with a quantity of powder such that a urease activity of 40

3 Results

3.1 Post-drying sample analysis (residual moisture, image analysis, cell viability)

3.1.1 Fluidized bed drying

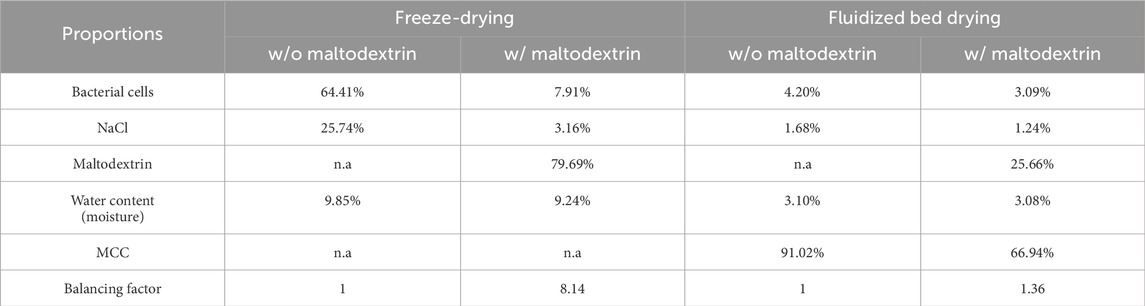

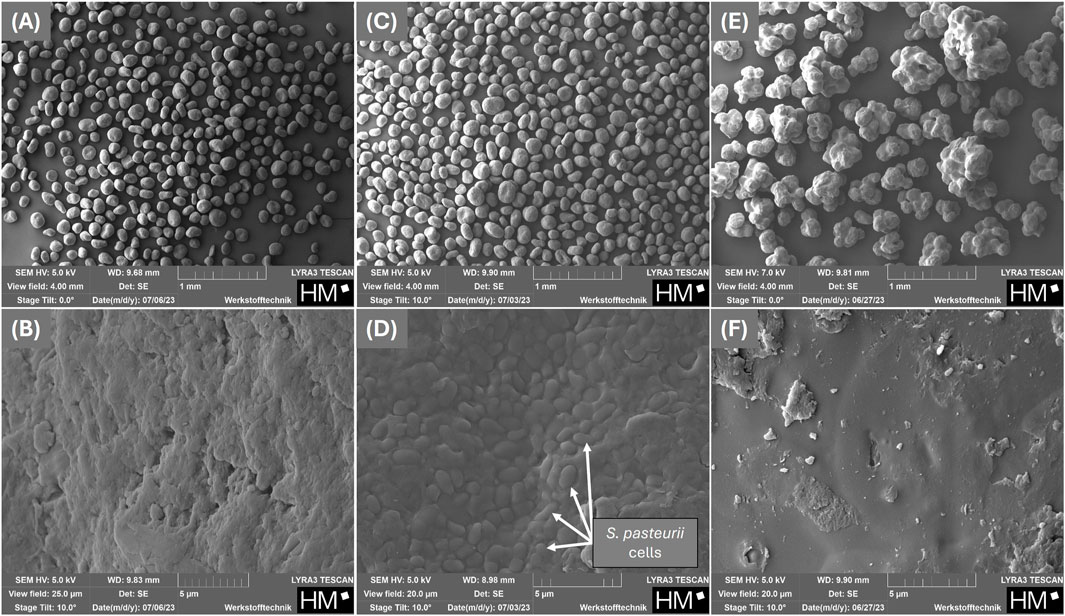

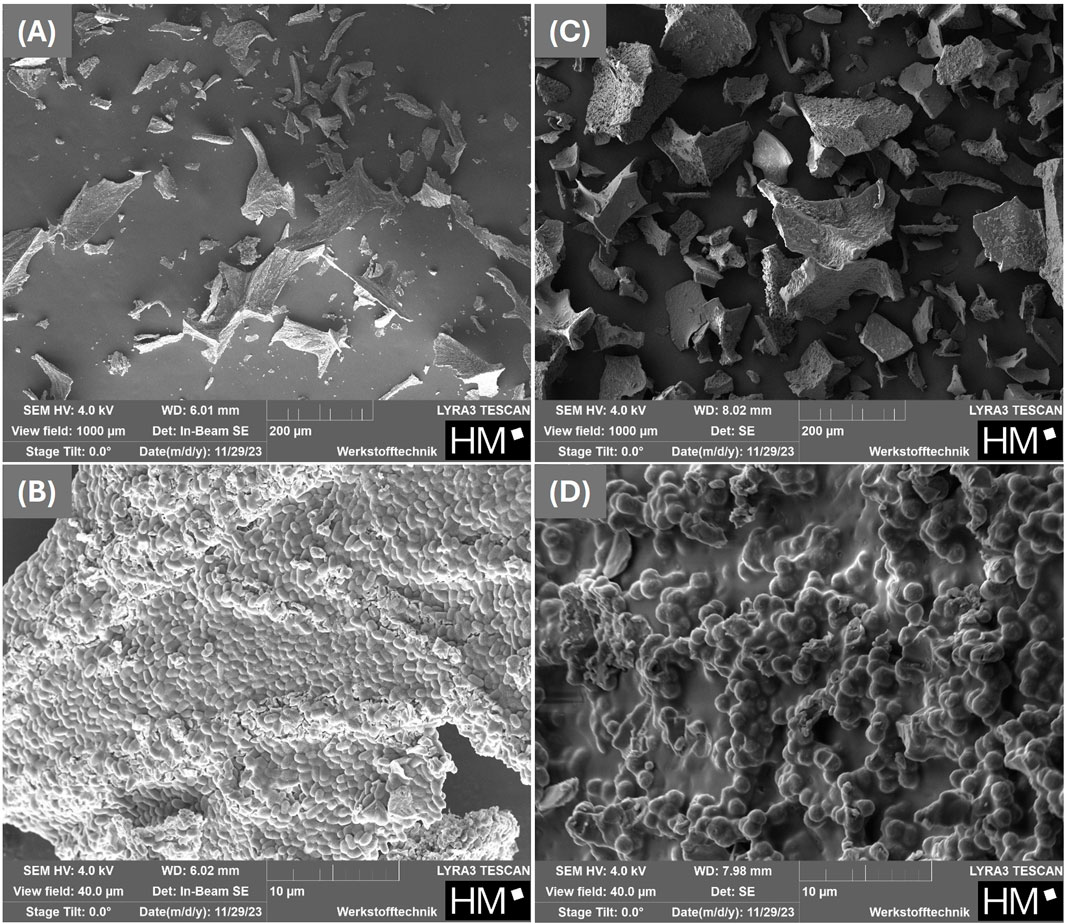

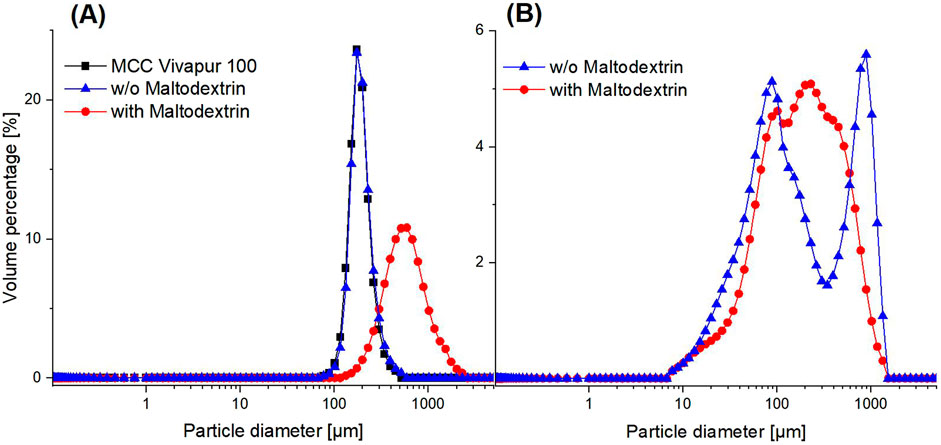

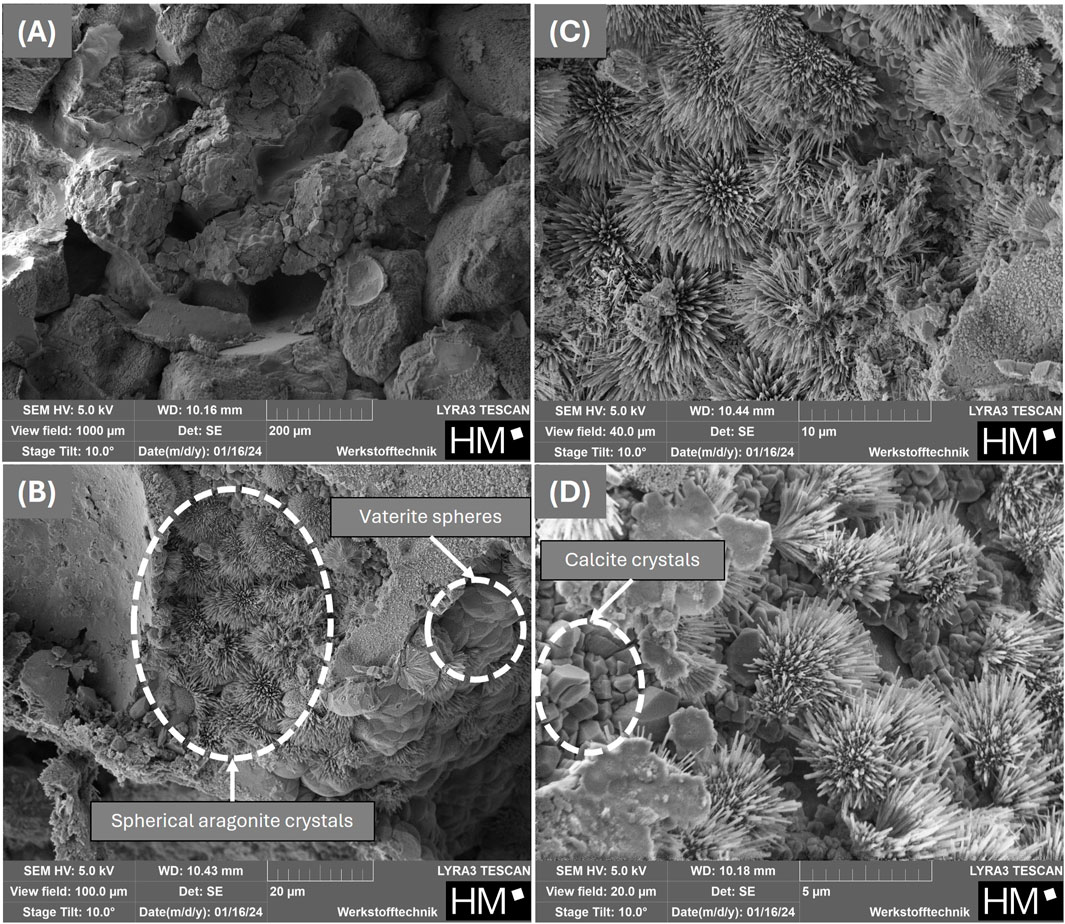

After the fluidized bed drying process and the post-drying, the residual moisture of the powders was measured, resulting in resulting in 3.10% w/o and 3.08% with maltodextrin. The residual moisture content of the MCC before drying was 4.37%. SEM images of the MCC before the fluidized bed drying process (Figures 2A,B) and after the process without (Figures 2C,D) and with maltodextrin as protectant (Figures 2E,F) were taken. Figures 2A,C,D show images at a magnification corresponding to a field of view of 4 mm, while Figures 2B,D,F show images at higher magnification, with a field of view between 25

Figure 2. SEM-micrographs of the carrier used for fluidized bed drying: microcrystalline cellulose before coating with Sporosarcina pasteurii (A,B) and after coating with Sporosarcina pasteurii without (C,D) and with 15% (w/w) maltodextrin (E,F) as a protectant.

Figure 3. SEM-micrographs of the freeze-dried organism Sporosarcina pasteurii without (A,B) and with 15% (w/w) maltodextrin as protectant (C,D).

Figure 4. Particle size distribution of dried Sporosarcina pasteurii using fluidized bed drying (A) by coating on microcrystalline cellulose (MCC Vivapur 100) and freeze-drying (B). Both methods were performed without and with the cryoprotectant maltodextrin.

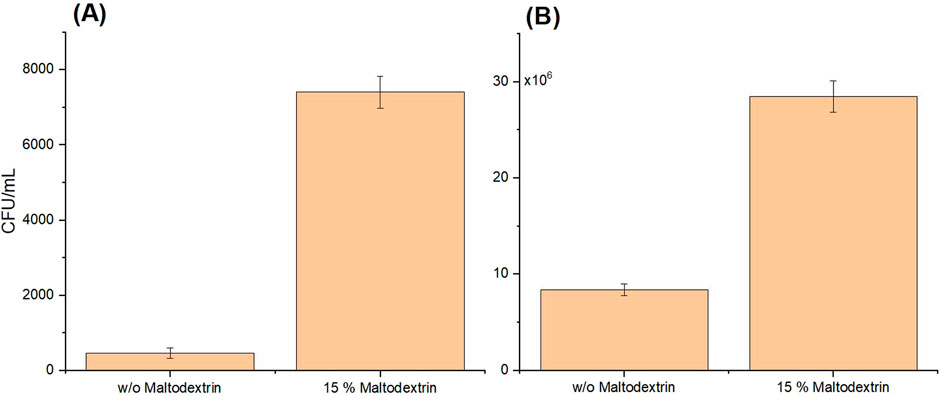

Figure 5. Cell viability of Sporosarcina pasteurii, tested on agar plates by colony-forming unit (CFU) counts per mL of resuspended powder after fluidized bed drying (A) and freeze-drying (B), without and with maltodextrin as a protectant. The plated suspension was prepared from resuspended powder and adjusted to an

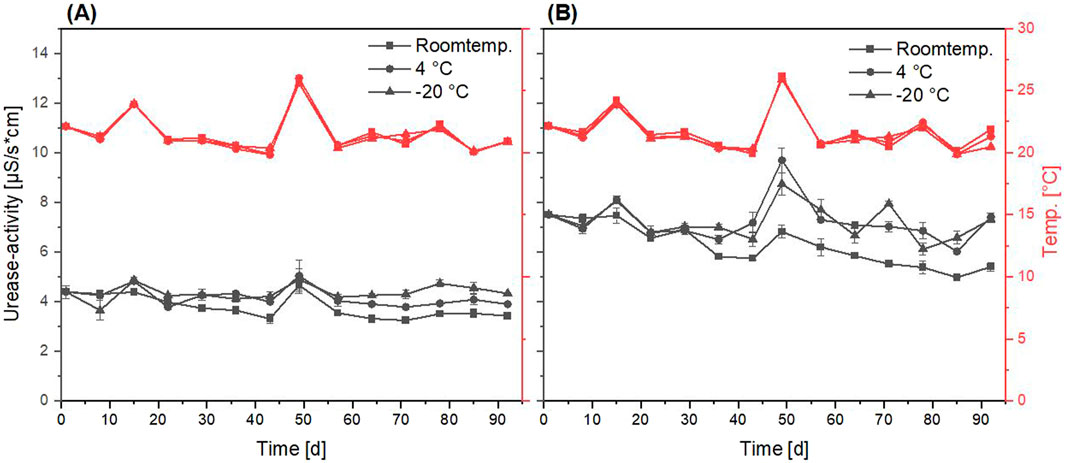

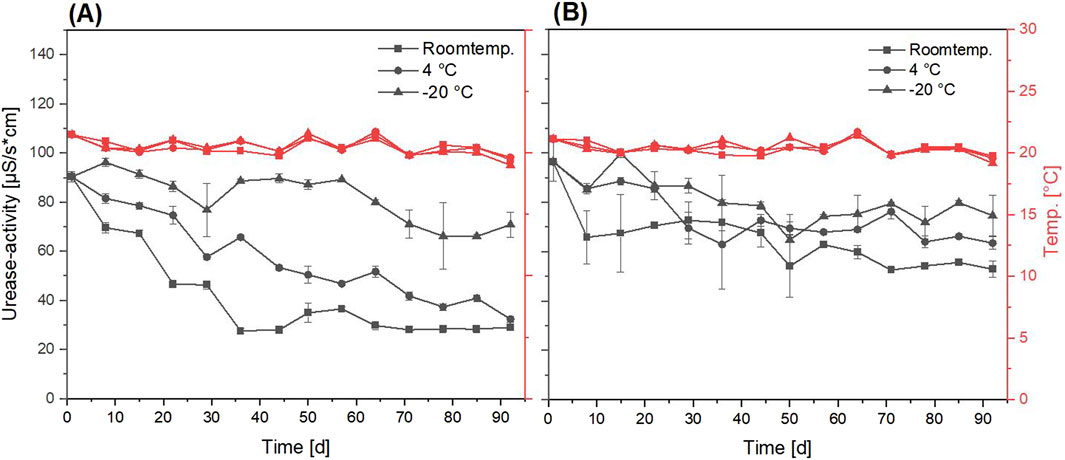

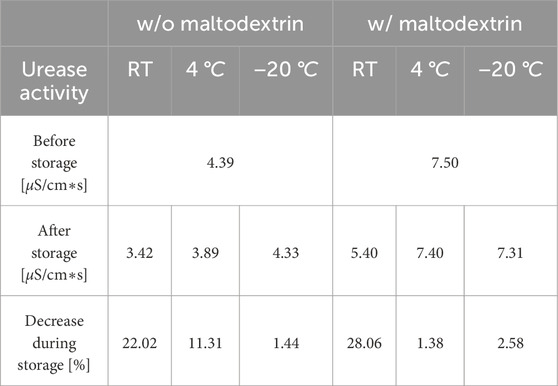

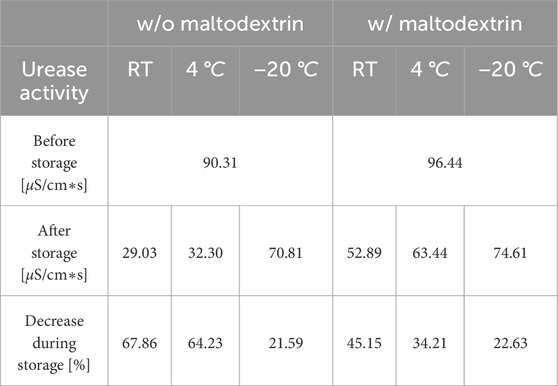

Figure 6. Progression of urease activity (black graphs) of fluidized bed dried Sporosarcina pasteurii powder over 92 days of storage under different conditions (room temperature, 4

3.1.2 Freeze-drying

After the bacterial suspensions with and w/o protectant were freeze-dried in 50 mL tubes and the resulting dried bacterial mass was crushed, SEM images were also taken here. Figures 3A,C show images at a magnification corresponding to a field of view of 1 mm, while Figures 3B,D show images at higher magnification, with a field of view of 40

Figure 7. Progression of urease activity (black graphs) of freeze-dried Sporosarcina pasteurii powder over 92 days of storage under different conditions (room temperature, 4

3.2 Storage

Over a period of 92 days all powders were stored under three different conditions (room temperature, 4

3.2.1 Fluidized bed drying

The dried powder using the fluidized bed drying process with a protectant showed a higher urease activity of 7.50

Table 3. Comparison of initial and final urease activity in fluidized bed dried powder, including percentage loss after storage for 92 days under three different conditions (room temperature (RT), 4

3.2.2 Freeze-drying

A greater loss of the urease activity after the storage at room temperature and 4

Table 4. Comparison of initial and final urease activity in freeze-dried powder, including percentage loss after storage for 92 days under three different conditions (room temperature (RT), 4

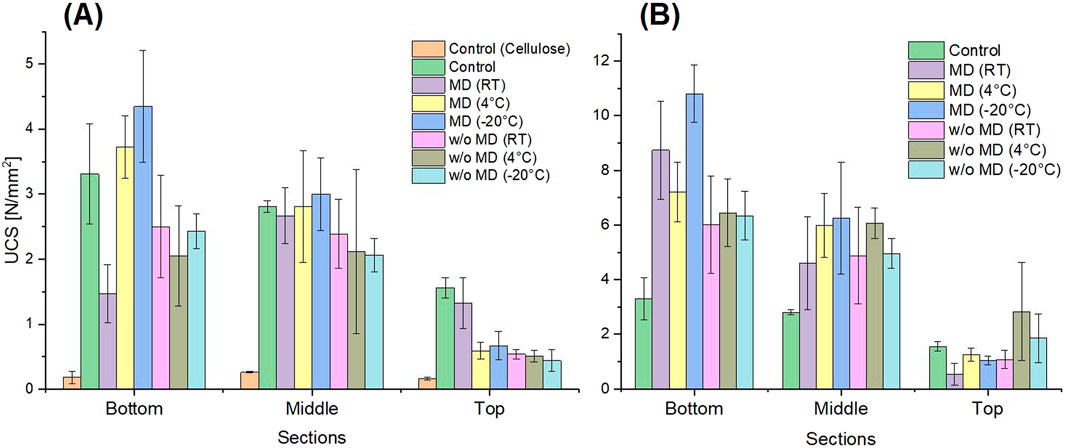

3.3 Usage for MICP

In order to determine the potential of the various powders for the process of biocementation after storage, sand columns were produced as test specimens. A total urease activity of 40

Figure 8. Uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) data of the reactivated Sporosarcina pasteurii powder dried with fluidized bed drying (A) and freeze-drying (B). For all treated sand columns, a total urease activity of 40

3.3.1 Fluidized bed drying

Both powders, with and without protectant, showed urease activity after storage and could still be used for biocementation, as shown in Figure 8. A solidification of the sand was observed in all column areas, comparable to that achieved with a liquid culture without MCC in the sand. The highest strength achieved was 4.35

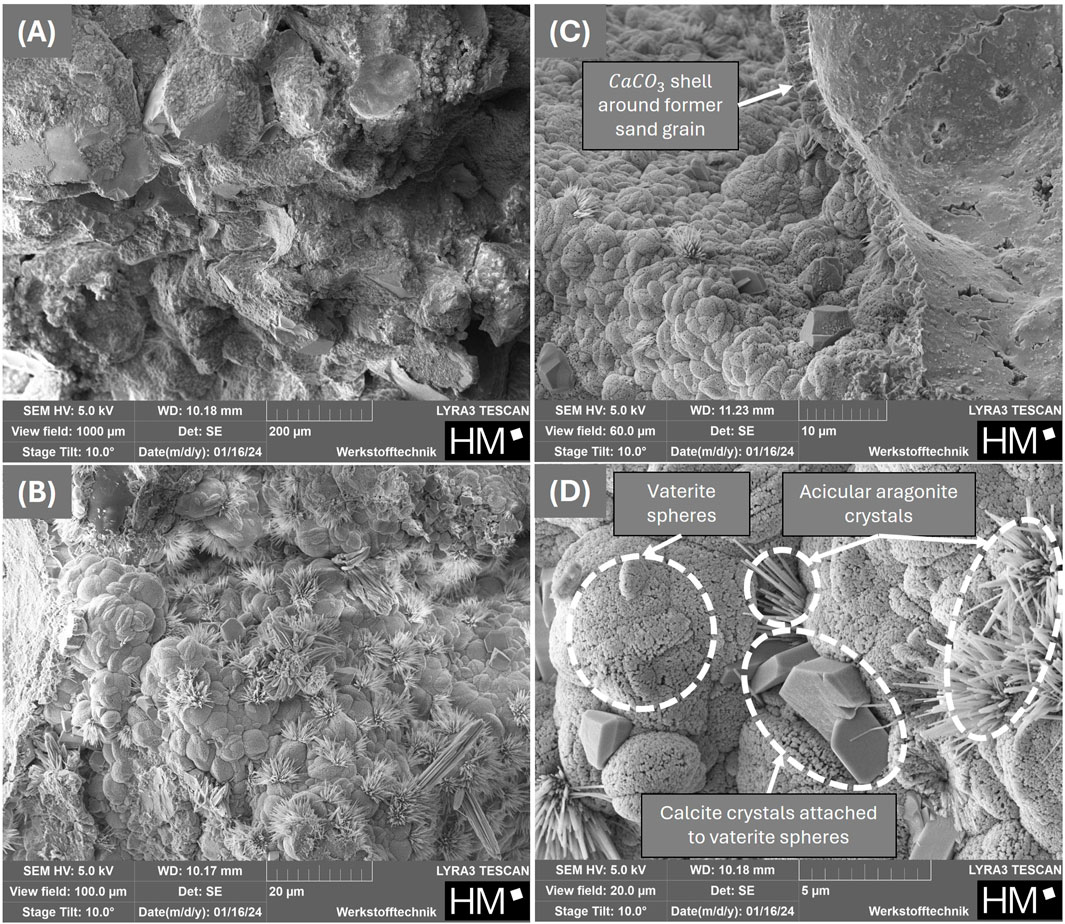

Figure 9. SEM-micrographs of fragments from the bottom section of cured sand columns with increasing magnifications from (A-D) produced with the powder obtained from fluidized bed drying with maltodextrin.

3.3.2 Freeze-drying

The maximum UCS of 10.81

Figure 10. SEM-micrographs of fragments from the bottom section of cured sand columns with increasing magnifications from (A-D) produced with the powder obtained from freeze-drying with maltodextrin.

4 Discussion

4.1 Post-drying sample analysis (residual moisture, image analysis, cell viability)

The low viability of the cells after fluidized bed drying cannot be attributed to the type of spray flow, which consisted of nitrogen. Ghandi et al. (2012) showed that during spray drying, an atomization stage with nitrogen ensures higher survival rates in Lactococcus lactis than ambient air alone, due to the prevention of oxidation of the cell membrane by the inertness of nitrogen. It was therefore assumed that this positive effect of nitrogen could also have come into play with fluidized bed drying in the present study. However, after fluidized bed drying, hardly any cells (<1%) were still able to form CFUs (Figure 5A). Nevertheless, there was measurable urease activity, indicating that the urease enzyme was still active after drying. Wang et al. (2024) showed that immobilizing urease on MCC is possible, which could also be seen in the present study with urease containing cells. One theory for the low viability of the cells after fluidized bed drying could be that the residual moisture content of the powder was too low, as it was significantly reduced to 3.08% and 3.10% by post drying, shown in Table 2. Here, the presence of the cryoprotectant maltodextrin had no influence on the residual moisture. The nozzle used for spraying the bacteria into the drying chamber had a diameter of 0.8 mm, which was comparable to those used in other studies that dried bacteria using fluidized bed drying Bensch et al. (2014), which achieved a significantly higher survival rate of the cells. These findings indicate that the nozzle, as well as the temperatures used and the mass flow rate, which were lower in the present study compared to similar studies Bensch et al. (2014); Stummer et al. (2012); Strasser et al. (2009), can be ruled out as the cause of the low viability.

With freeze-drying, the residual moisture was significantly higher with 9.24% and 9.85% and the viability of the cells was almost 21% (Figure 5B). It has already been reported that a water content that is too high or too low could affect the viability of dried cells. Zayed and Roos (2004) discovered an optimal residual moisture for freeze-dried Lactobacillus salivarius cells between 2.8%–5.6% and Oluwatosin et al. (2022) reached also a lower residual moisture with 2.92% after freeze-drying Lactobacillus plantarum cells.

Compared to studies that had also worked with maltodextrin as a cryoprotectant, this viability (also called survivability) was rather low. For Lactobacillus acidophilus FTDC 3081 other cryoprotectants, such as skim milk or sucrose, worked better in a freeze-drying process in comparison to 10% or 20% (w/v) maltodextrin, but still better than without Tang et al. (2020). In the present study, too, the cryoprotectant always had a positive influence. Therefore, the low vitality compared to the state of research for other organisms can rather be attributed to the drying behavior of S. pasteurii. Ge et al. (2024) tested four different possible cryoprotectants in five different concentrations, each with the most varied vitality results after freeze-drying for the organism L. lactis ZFM559. This highlights how diverse and complex it can be to find the right cryoprotectant in the appropriate concentration for a given organism, likely for S. pasteurii as well. In the case of L. plantarum cells, a decline in cell viability was observed after freeze-drying with water or 10% (m/v) maltodextrin and after storage at room temperature or 4

When looking at the SEM images (Figures 2E,F; Figures 3C,D), it was noticeable that the powder with maltodextrin had a smooth, non-cracked surface without the bacteria being visible. Majidzadeh Heravi et al. (2022) also described a uniformly smooth surface of the maltodextrin-coated or dried powders. It can therefore be assumed that maltodextrin completely surrounds and embeds the cells. This protected them from further external influences until they were rehydrated again. However, this protection did not appear to be sufficient to protect the cells from a loss of viability if the residual moisture content of the powder was too low.

4.2 Storage

When looking at the urease activity at the beginning of storage (Figures 6, 7), the high difference in urease activity per gram of powder can be attributed to the proportion of MCC in the weight of the fluidized bed dried powder. Due to the unknown loss of MCC and liquid not sprayed onto it during the drying process, an exact calculation was not possible. For the freeze-dried powder, this effect was not relevant, due to the directly dried bacteria without any carrier. In comparison to stored liquid cultures of S. pasteurii Erdmann et al. (2022); Mehring et al. (2021), the urease activity showed a better stability for every powder, except the freeze-dried powder without maltodextrin (Figure 7A).

The storage conditions of S. pasteurii in liquid culture showed varying effects on viability, optical density, and urease activity. After 18 days, no significant impact was observed at −18

In comparison to the study of Tuttle et al. (2025), in which the lyophilized S. pasteurii cells were stored in plastic bags at 25

4.3 Usage for MICP

Due to the low viability of the S. pasteurii cells after the fluidized bed drying process, it can be assumed that using this powder for biocementation was no longer a MICP process but rather an enzyme induced carbonate precipitation (EICP) or a mixture of both principles. For the freeze-dried powders, the viability was higher with almost 21%, therefore both, MICP and EICP, probably occurred with the freeze-dried powder. In general, the enzyme urease is described as an intracellular enzyme Mobley et al. (1995), and in the organism S. pasteurii, urease is also present intracellularly Ma et al. (2020). Due to the low viability, cell damage must be assumed, such as damage to the cell wall, which could lead to the release of intracellular urease. This extracellularly available urease would still be able to catalyze urea hydrolysis, thereby enabling carbonate precipitation even in the absence of fully viable cells.

A key advantage of the approach used in the present study were the exceptionally high UCS values achieved. Reviews featuring numerous UCS values indicate that the most reported values (Zhang et al., 2025; Fu et al., 2023; Tong et al., 2021), although derived from liquid cultures and therefore not directly comparable, are generally lower than those obtained in the present study. This indicates that the treatment method achieves remarkably high compressive strengths in sand columns even without optimization. Compared to a liquid culture with the same total urease activity, higher strengths were achieved with the different dried powders. This could be attributed to the fact that the enzyme and the microorganism were less likely to be washed out by the cementation solution, consisting of calcium ions and urea, when present in powdered form or coated on MCC. Adsorption studies have already demonstrated that microbial washout consistently occurs when MICP was conducted using liquid cultures of S. pasteurii Sang et al. (2023); Tobler et al. (2014); Hanisch et al. (2024). As a result, the urease activity in the sand column decreases with each flow of the cementing solution, leading to lower strengths of the control (green bars), as shown in Figure 8. Similar observations regarding the inhomogeneous distribution and strength reduction of the sand columns with distance from the solution inlet were reported by Hanisch et al. (2024). It can be attributed to the consumption of calcium ions in the initial areas of the sand column due to the MICP process, followed by the formation of

Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that, in theory, all sand columns in the present study, prepared with the dried powders, should exhibit the same strength, as they were subjected to identical urease activity. Within the respective drying method, this also applies approximately, no matter with or without protectant. Therefore, an influence of the protectant on the strength of the sand column can be excluded. However, there was a big difference in the strengths when comparing the two powders produced in different ways. With UCS values in a range of 1.47–4.35

In the study by Tuttle et al. (2025), sand columns were treated up to twelve times with a cementation solution (0.33 M urea, 0.33 M

SEM images (Figures 9, 10) of the different

Figure 11 illustrates the formation of

Figure 11. Images from the Crystallization System (Technobis), show the resulting

5 Conclusion

The study investigates the possibility of drying the microorganism S. pasteurii, which is frequently used in the field of MICP, using two different techniques: the commonly used freeze-drying and fluidized bed drying, both with and without the protectant maltodextrin. As a first study, these two methods were examined with regard to long-term storage of cells for 92 days under different conditions and their subsequent application in soil stabilization, with the following main results.

• Maltodextrin showed a positive effect on cell viability and urease stability for both drying methods. For fluidized bed drying it tended to make the entire spraying process longer due to higher viscosity and led to a powder with strong agglomeration. In the case of freeze-drying, the protectant had a much more positive effect.

• The freeze-dried powder with maltodextrin showed the highest cell viability (ability to form CFUs) with almost 21% compared to the control (fresh liquid culture). After fluidized bed drying, the cell viability was less than 1%. Nevertheless, measurable enzyme activity was detected immediately afterwards and also after 3 months of storage for all powders.

• The storage temperature of the different powders (room temperature, 4

• Each powder, regardless of the drying or storage method, increased the strength of sand columns through the MICP process by up to 10.81

Fluidized bed drying can have significantly lower costs, with only 8.8% fixed costs and 17.9% production costs compared to freeze-drying (Santivarangkna et al., 2007). In addition to the high variability of the carrier materials (size, materials, particle distribution), it is a highly efficient alternative to freeze-drying. Moreover, the present study clearly demonstrates, even without process optimization, that dried S. pasteurii bacteria can be stored for extended periods and successfully reused for soil stabilization. In addition, dried bacterial powders offer significant advantages not only for storage but also for transport to specific application sites. The reduced weight and volume of dried bacteria in comparison to liquid cultures lead to lower transportation costs, making large-scale MICP applications more feasible and economically viable. Furthermore, drying allows for applying the cells in higher concentrations, potentially enhancing their effectiveness in MICP processes and improving overall performance in practical applications.

The present study confirms that fluidized bed and freeze-drying enables storage of S. pasteurii even at room temperature without the need for a protective agent, highlighting its suitability for practical MICP applications and supporting large-scale implementation—thus making MICP more easy and broadly applicable in the construction and geoengineering sectors.

Further optimization of the drying processes, including the investigation of various cryoprotectants and their concentrations, could significantly improve storage stability. In addition, alternative drying methods, such as spray drying, may provide promising results for preserving bacteria used in MICP applications. Moreover, reactivation protocols—such as the composition of the recovery media and pre-hydration steps—are also critical factors that can influence the viability and performance of dried cells upon reuse.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PH: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization, Methodology. MP: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. CE: Resources, Writing – review and editing. SK: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing. TM: Resources, Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing. RH: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Open Access funding enabled and organized by project DEAL. Funding Open access was provided by the Publication Fund of the Munich University of Applied Sciences HM. The research was financially supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research under the project MicrobialCrete (Grant: 13FH119PX8).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Benedikt Kaufmann and Yasemin Geiger for their help with freeze-drying, Daniel Wanghofer for his support with fluidized bed drying and Frédéric Lapierre and Martin Poppe for their assistance with laboratory tests. We would also like to thank Mr. Maag for his support with the Crystalline system from Technobis Crystallization Systems.

Conflict of interest

Authors SK and TM were employed by Wacker Chemie AG.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alazhari, M., Sharma, T., Heath, A., Cooper, R., and Paine, K. (2018). Application of expanded perlite encapsulated bacteria and growth media for self-healing concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 160, 610–619. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.11.086

Alev, B., Tunali, S., Yanardag, R., and Yarat, A. (2019). Influence of storage time and temperature on the activity of urease. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 51, 159–163. doi:10.34049/bcc.51.2.4536

Baidya, P., Dahal, B. K., Pandit, A., and Joshi, D. R. (2023). Bacteria-induced calcite precipitation for engineering and environmental applications. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 1–25. doi:10.1155/2023/.2613209

Bensch, G., Rüger, M., Wassermann, M., Weinholz, S., Reichl, U., and Cordes, C. (2014). Flow cytometric viability assessment of lactic acid bacteria starter cultures produced by fluidized bed drying. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 4897–4909. doi:10.1007/s00253-014-5592-z

Broeckx, G., Vandenheuvel, D., Claes, I. J. J., Lebeer, S., and Kiekens, F. (2016). Drying techniques of probiotic bacteria as an important step towards the development of novel pharmabiotics. Int. J. Pharm. 505, 303–318. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.04.002

Chen, B., Sun, W., Sun, X., Cui, C., Lai, J., Wang, Y., et al. (2021). Crack sealing evaluation of self-healing mortar with sporosarcina pasteurii: influence of bacterial concentration and air-entraining agent. Process Biochem. 107, 100–111. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2021.05.001

Chen, Y.-Q., Wang, S.-Q., Tong, X.-Y., and Kang, X. (2022). Crystal transformation and self-assembly theory of microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 106, 3555–3569. doi:10.1007/.s00253-022-11938-7

Chen, S., Kang, B., Zha, F., Shen, Y., Chu, C., and Tao, W. (2024). Effects of different Mg/Ca molar ratio on the formation of carbonate minerals in microbially induced carbonate precipitation (micp) process. Constr. Build. Mater. 442, 137643. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137643

Devgon, I., Kumar Sachan, R. S., Rajput, K., Kumar, M., Mohammad Said Al-Tawaha, A. R., Karnwal, A., et al. (2024). Exploring fungal potential for microbial-induced calcite precipitation (micp) in bio-cement production. Front. Mater. 11, 1396081. doi:10.3389/fmats.2024.1396081

Erdmann, N., Kästner, F., de Payrebrune, K., and Strieth, D. (2022). Sporosarcina pasteurii can be used to print a layer of calcium carbonate. Eng. life Sci. 22, 760–768. doi:10.1002/elsc.202100074

Erdmann, N., Schaefer, S., Simon, T., Becker, A., Bröckel, U., and Strieth, D. (2024). Micp treated sand: insights into the impact of particle size on mechanical parameters and pore network after biocementation. Discov. Mater. 4, 45. doi:10.1007/s43939-024-00108-3

Fu, Q., Wu, Y., Liu, S., Lu, L., and Wang, J. (2022). The adaptability of Sporosarcina pasteurii in marine environments and the feasibility of its application in mortar crack repair. Constr. Build. Mater. 332, 127371. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127371

Fu, T., Saracho, A. C., and Haigh, S. K. (2023). Microbially induced carbonate precipitation (micp) for soil strengthening: a comprehensive review. Biogeotechnics 1, 100002. doi:10.1016/j.bgtech.2023.100002

García-González, J., Rodríguez-Robles, D., Wang, J., de Belie, N., Morán-del Pozo, J. M., Guerra-Romero, M. I., et al. (2017). Quality improvement of mixed and ceramic recycled aggregates by biodeposition of calcium carbonate. Constr. Build. Mater. 154, 1015–1023. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.08.039

Ge, S., Han, J., Sun, Q., Ye, Z., Zhou, Q., Li, P., et al. (2024). Optimization of cryoprotectants for improving the freeze-dried survival rate of potential probiotic lactococcus lactis zfm559 and evaluation of its storage stability. LWT 198, 116052. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2024.116052

Ghandi, A., Powell, I. B., Howes, T., Chen, X. D., and Adhikari, B. (2012). Effect of shear rate and oxygen stresses on the survival of lactococcus lactis during the atomization and drying stages of spray drying: a laboratory and pilot scale study. J. Food Eng. 113, 194–200. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2012.06.005

Hanisch, P., Pechtl, M., Maurer, H., Maier, F., Bischoff, S., Nagy, B., et al. (2024). The effect of different additives on bacteria adsorption, compressive strength and ammonia removal for micp. Environ. Earth Sci. 83, 635. doi:10.1007/s12665-024-11929-z

Hu, W., Cheng, W.-C., Wen, S., and Yuan, K. (2021). Revealing the enhancement and degradation mechanisms affecting the performance of carbonate precipitation in eicp process. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 750258. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2021.750258

Iyer, P. V., and Ananthanarayan, L. (2008). Enzyme stability and stabilization—aqueous and non-aqueous environment. Process Biochem. 43, 1019–1032. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2008.06.004

Jadhav, U. U., Lahoti, M., Chen, Z., Qiu, J., Cao, B., and Yang, E.-H. (2018). Viability of bacterial spores and crack healing in bacteria-containing geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 169, 716–723. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.03.039

Jiang, L., Jia, G., Jiang, C., and Li, Z. (2020). Sugar-coated expanded perlite as a bacterial carrier for crack-healing concrete applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 232, 117222. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117222

Jones, R. J., and Srubar, W. V. (2022). Biomineralization of symbiotic cultures of bacteria and yeast (scoby) cellulose aerogels. Adv. Eng. Mater. 24, 2200681. doi:10.1002/.adem.202200681

Jonkers, H. M., Thijssen, A., Muyzer, G., Copuroglu, O., and Schlangen, E. (2010). Application of bacteria as self-healing agent for the development of sustainable concrete. Ecol. Eng. 36, 230–235. doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2008.12.036

Kahani, M., Kalantary, F., Soudi, M. R., Pakdel, L., and Aghaalizadeh, S. (2020). Optimization of cost effective culture medium for sporosarcina pasteurii as biocementing agent using response surface methodology: up cycling dairy waste and seawater. J. Clean. Prod. 253, 120022. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120022

Khoshtinat, S. (2023). Advancements in exploiting sporosarcina pasteurii as sustainable construction material: a review. Sustainability 15, 13869. doi:10.3390/su151813869

Khushnood, R. A., Qureshi, Z. A., Shaheen, N., and Ali, S. (2020). Bio-mineralized self-healing recycled aggregate concrete for sustainable infrastructure. Sci. total Environ. 703, 135007. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135007

Lapierre, F. M., Schmid, J., Ederer, B., Ihling, N., Büchs, J., and Huber, R. (2020). Revealing nutritional requirements of micp-relevant sporosarcina pasteurii dsm33 for growth improvement in chemically defined and complex media. Sci. Rep. 10, 22448. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79904-9

Lapierre, F. M., Bolz, I., Büchs, J., and Huber, R. (2022). Developing a fluorometric urease activity microplate assay suitable for automated microbioreactor experiments. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 936759. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2022.936759

Li, Z., Huo, L., Zhi, J., Zhang, S., and Wu, X. (2023). Growth kinetics of bacillus pasteurii in xanthan gum solid-free drilling fluid at different temperatures. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 223, 211482. doi:10.1016/j.geoen.2023.211482

Lv, M., Ma, X., Anderson, D. P., and Chang, P. R. (2018). Immobilization of urease onto cellulose spheres for the selective removal of urea. Cellulose 25, 233–243. doi:10.1007/.s10570-017-1592-3

Ma, L., Pang, A.-P., Luo, Y., Lu, X., and Lin, F. (2020). Beneficial factors for biomineralization by ureolytic bacterium sporosarcina pasteurii. Microb. cell factories 19, 12. doi:10.1186/s12934-020-1281-z

Majidzadeh Heravi, R., Ghiasvand, M., Rezaei, E., and Kargar, F. (2022). Assessing the viability of three lactobacillus bacterial species protected in the cryoprotectants containing whey and maltodextrin during freeze-drying process. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 74, 505–512. doi:10.1111/lam.13631

Mehring, A., Erdmann, N., Walther, J., Stiefelmaier, J., Strieth, D., and Ulber, R. (2021). A simple and low-cost resazurin assay for vitality assessment across species. J. Biotechnol. 333, 63–66. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2021.04.010

Mobley, H. L., Island, M. D., and Hausinger, R. P. (1995). Molecular biology of microbial ureases. Microbiol. Rev. 59, 451–480. doi:10.1128/mr.59.3.451-480.1995

Morgan, C. A., Herman, N., White, P. A., and Vesey, G. (2006). Preservation of micro-organisms by drying; a review. J. Microbiol. methods 66, 183–193. doi:10.1016/.j.mimet.2006.02.017

Mujah, D., Shahin, M. A., and Cheng, L. (2017). State-of-the-art review of biocementation by microbially induced calcite precipitation (micp) for soil stabilization. Geomicrobiol. J. 34, 524–537. doi:10.1080/01490451.2016.1225866

Naveed, M., Duan, J., Uddin, S., Suleman, M., Hui, Y., and Li, H. (2020). Application of microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation with urea hydrolysis to improve the mechanical properties of soil. Ecol. Eng. 153, 105885. doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2020.105885

Oluwatosin, S. O., Tai, S. L., and Fagan-Endres, M. A. (2022). Sucrose, maltodextrin and inulin efficacy as cryoprotectant, preservative and prebiotic - towards a freeze dried lactobacillus plantarum topical probiotic. Biotechnol. Rep. Amst. Neth. 33, e00696. doi:10.1016/j.btre.2021.e00696

Omoregie, A. I., Palombo, E. A., Ong, D. E., and Nissom, P. M. (2020). A feasible scale-up production of sporosarcina pasteurii using custom-built stirred tank reactor for in-situ soil biocementation. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 24, 101544. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2020.101544

Peiren, J., Buyse, J., de Vos, P., Lang, E., Clermont, D., Hamon, S., et al. (2015). Improving survival and storage stability of bacteria recalcitrant to freeze-drying: a coordinated study by european culture collections. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99, 3559–3571. doi:10.1007/.s00253-015-6476-6

Pungrasmi, W., Intarasoontron, J., Jongvivatsakul, P., and Likitlersuang, S. (2019). Evaluation of microencapsulation techniques for micp bacterial spores applied in self-healing concrete. Sci. Rep. 9, 12484. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49002-6

Rodriguez-Blanco, J. D., Shaw, S., and Benning, L. G. (2011). The kinetics and mechanisms of amorphous calcium carbonate (acc) crystallization to calcite, via vaterite. Nanoscale 3, 265–271. doi:10.1039/c0nr00589d

Røyne, A., Phua, Y. J., Balzer Le, S., Eikjeland, I. G., Josefsen, K. D., Markussen, S., et al. (2019). Towards a low co2 emission building material employing bacterial metabolism (1/2): the bacterial system and prototype production. PloS one 14, e0212990. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0212990

Sang, G., Lunn, R. J., El Mountassir, G., and Minto, J. M. (2023). Transport and fate of ureolytic sporosarcina pasteurii in saturated sand columns: experiments and modelling. Transp. Porous Media 149, 599–624. doi:10.1007/.s11242-023-01973-x

Santivarangkna, C., Kulozik, U., and Foerst, P. (2007). Alternative drying processes for the industrial preservation of lactic acid starter cultures. Biotechnol. Prog. 23, 302–315. doi:10.1021/bp060268f

Schell, D., and Beermann, C. (2014). Fluidized bed microencapsulation of lactobacillus reuteri with sweet whey and shellac for improved acid resistance and in-vitro gastro-intestinal survival. Food Res. Int. 62, 308–314. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2014.03.016

Ševčík, R., Šašek, P., and Viani, A. (2018). Physical and nanomechanical properties of the synthetic anhydrous crystalline caco3 polymorphs: vaterite, aragonite and calcite. J. Mater. Sci. 53, 4022–4033. doi:10.1007/s10853-017-1884-x

Son, Y., Min, J., Jang, I., Yi, C., and Park, W. (2022). Development of a novel compressed tablet-based bacterial agent for self-healing cementitious material. Cem. Concr. Compos. 129, 104514. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2022.104514

Song, C., Wang, C., Elsworth, D., and Zhi, S. (2022). Compressive strength of micp-treated silica sand with different particle morphologies and gradings. Geomicrobiol. J. 39, 148–154. doi:10.1080/01490451.2021.2020936

Strasser, S., Neureiter, M., Geppl, M., Braun, R., and Danner, H. (2009). Influence of lyophilization, fluidized bed drying, addition of protectants, and storage on the viability of lactic acid bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 107, 167–177. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04192.x

Stummer, S., Toegel, S., Rabenreither, M.-C., Unger, F. M., Wirth, M., Viernstein, H., et al. (2012). Fluidized-bed drying as a feasible method for dehydration of enterococcus faecium m74. J. Food Eng. 111, 156–165. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2012.01.005

Tan, D. T., Poh, P. E., and Chin, S. K. (2018). Microorganism preservation by convective air-drying—A review. Dry. Technol. 36, 764–779. doi:10.1080/.07373937.2017.1354876

Tang, H. W., Abbasiliasi, S., Murugan, P., Tam, Y. J., Ng, H. S., and Tan, J. S. (2020). Influence of freeze-drying and spray-drying preservation methods on survivability rate of different types of protectants encapsulated lactobacillus acidophilus ftdc 3081. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 84, 1913–1920. doi:10.1080/09168451.2020.1770572

Taskin, O. (2020). Evaluation of freeze drying for whole, half cut and puree black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa l.). Heat Mass Transf. 56, 2503–2513. doi:10.1007/.s00231-020-02867-0

Terzis, D., and Laloui, L. (2018). 3-d micro-architecture and mechanical response of soil cemented via microbial-induced calcite precipitation. Sci. Rep. 8, 1416. doi:10.1038/.s41598-018-19895-w

Terzis, D., and Laloui, L. (2019). Cell-free soil bio-cementation with strength, dilatancy and fabric characterization. Acta Geotech. 14, 639–656. doi:10.1007/s11440-019-00764-3

Tobler, D. J., Cuthbert, M. O., and Phoenix, V. R. (2014). Transport of Sporosarcina pasteurii in sandstone and its significance for subsurface engineering technologies. Appl. Geochem. 42, 38–44. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2014.01.004

Tong, Yu, Hanene, S., Yoan, P., and Jean-Marie, F. (2021). Review on engineering properties of micp-treated soils. Geomechanics Eng. 27, 13–30. doi:10.12989/GAE.2021.27.1.013

Tuttle, M. J., Bradow, B. M., Martineau, R. L., Carter, M. S., Mancini, J. A., Holley, K. A., et al. (2025). Shelf-stable sporosarcina pasteurii formulation for scalable laboratory and field-based production of biocement. ACS Appl. Mater. and Interfaces 17, 7251–7261. doi:10.1021/.acsami.4c15381

Valencia-Galindo, M., Sáez, E., Ovalle, C., and Ruz, F. (2021). Evaluation of the effectiveness of a soil treatment using calcium carbonate precipitation from cultivated and lyophilized bacteria in soil’s compaction water. Buildings 11, 545. doi:10.3390/buildings11110545

Wang, J. Y., Soens, H., Verstraete, W., and de Belie, N. (2014). Self-healing concrete by use of microencapsulated bacterial spores. Cem. Concr. Res. 56, 139–152. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2013.11.009

Wang, X., Tang, D., and Wang, W. (2020). Improvement of a dry formulation of pseudomonas protegens sn15-2 against ralstonia solanacearum by combination of hyperosmotic cultivation with fluidized-bed drying. BioControl 65, 751–761. doi:10.1007/s10526-020-10042-x

Wang, S., Fang, L., Dapaah, M. F., Niu, Q., and Cheng, L. (2023). Bio-remediation of heavy metal-contaminated soil by microbial-induced carbonate precipitation (micp)—a critical review. Sustainability 15, 7622. doi:10.3390/su15097622

Wang, B., Wang, Z., Chen, M., Du, Y., Li, N., Chai, Y., et al. (2024). Immobilized urease vector system based on the dynamic defect regeneration strategy for efficient urea removal. ACS Appl. Mater. and Interfaces 16, 41321–41331. doi:10.1021/acsami.4c08323

Wiktor, V., and Jonkers, H. M. (2011). Quantification of crack-healing in novel bacteria-based self-healing concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 33, 763–770. doi:10.1016/.j.cemconcomp.2011.03.012

Wirunpan, M., Savedboworn, W., and Wanchaitanawong, P. (2016). Survival and shelf life of lactobacillus lactis 1464 in shrimp feed pellet after fluidized bed drying. Agric. Nat. Resour. 50, 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.anres.2016.01.001

Xu, X., Guo, H., Cheng, X., and Li, M. (2020). The promotion of magnesium ions on aragonite precipitation in micp process. Constr. Build. Mater. 263, 120057. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120057

Xu, J.-M., Chen, Z.-T., Cheng, F., Liu, Z.-Q., and Zheng, Y.-G. (2024). Exploring a cellulose-immobilized bacteria for self-healing concrete via microbe-induced calcium carbonate precipitation. J. Build. Eng. 95, 110248. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2024.110248

Zayed, G., and Roos, Y. H. (2004). Influence of trehalose and moisture content on survival of lactobacillus salivarius subjected to freeze-drying and storage. Process Biochem. 39, 1081–1086. doi:10.1016/S0032-9592(03)00222-X

Zhang, X., Wang, H., Wang, Y., Wang, J., Cao, J., and Zhang, G. (2025). Improved methods, properties, applications and prospects of microbial induced carbonate precipitation (micp) treated soil: a review. Biogeotechnics 3, 100123. doi:10.1016/j.bgtech.2024.100123

Zhou, G., Xu, Y., Wang, Y., Zheng, L., Zhang, Y., Li, L., et al. (2023). Study on micp dust suppression technology in open pit coal mine: preparation and mechanism of microbial dust suppression material. J. Environ. Manag. 343, 118181. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118181

Keywords: Sporosarcina pasteurii, microbial induced carbonate precipitation (MICP, ), fluidized bed drying, lyophilization (freeze-drying), storage, cell viability, protectant

Citation: Hanisch P, Pechtl M, Eulenkamp C, Krickl S, Melchin T and Huber R (2025) Impact of drying methods and storage conditions on the reactivation of Sporosarcina pasteurii for microbial induced carbonate precipitation. Front. Mater. 12:1616486. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2025.1616486

Received: 22 April 2025; Accepted: 22 October 2025;

Published: 21 November 2025.

Edited by:

John L. Provis, Paul Scherrer Institut (PSI), SwitzerlandCopyright © 2025 Hanisch, Pechtl, Eulenkamp, Krickl, Melchin and Huber. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Robert Huber, cm9iZXJ0Lmh1YmVyQGhtLmVkdQ==

Patrick Hanisch

Patrick Hanisch Markus Pechtl1

Markus Pechtl1 Robert Huber

Robert Huber