- 1Research and Development Cell, Lovely Professional University, Phagwara, India

- 2School of Mechanical Engineering, Lovely Professional University, Phagwara, India

- 3Department of Mechanical Engineering, Chandigarh University, Mohali, Punjab, India

Ceramic-based surface treatments, including plasma spraying, sol-gel coatings, and hydroxyapatite (HAp) layers, have emerged as effective strategies for enhancing the functionality of metallic biomaterials in orthopedic and dental implants. These coatings enhance cellular adhesion, accelerate bone growth, enhance osseointegration, corrosion barriers, and wear, and help maintain the mechanical integrity of the implant during cyclic loading. Plasma spraying is currently used because it is inexpensive and can produce thick deposits, especially with HAp, which enhances implant osteoconductivity and corrosion resistance. Sol-gel techniques facilitate the deposition of a uniform, nanostructured coating at low temperature, which increases the homogeneity of the coating and bioactivity. Functionally graded finishes gradually transition in terms of composition or porosity between the metal interface and the outer surface, corresponding to the stiffness to minimize stress concentration without eliminating bioactive layers to encourage bone ingrowth. Antibacterial coatings of silver, copper, and zinc have proven effective in antimicrobial activity via a variety of mechanisms, providing extended protection against bacterial colonization of the implant surface. Despite their advantages, ceramic coatings face challenges, such as poor adhesion, delamination, and long-term durability under physiological loading. Ongoing research focuses on developing functionally graded, composite, and antibacterial coatings to improve the performance and longevity of biomedical implants. The optimization of the coating thickness, adhesion strength, and minimization of defects is crucial to maximize the protective effects and ensure the long-term success of ceramic-coated metallic implants in clinical applications.

1 Introduction

The functionality of metallic biomaterials in orthopedic and dental implants is significantly increased by ceramic-based surface treatment. Using bioactive ceramics, including hydroxyapatite or bioactive glass, on metal surfaces, such coatings promote enhanced cellular adhesion and faster bone formation, thereby augmenting osseointegration. At the same time, ceramic layers are also effective barriers to corrosion and wear, which maintain the mechanical integrity of the implant when subjected to cyclic loading (Alahnoori et al., 2023). Figure 1 schematically represents the key surface engineering strategies evaluated in clinical orthopedic implant studies. These human implant case studies show that all approaches improve bone implantation, survival, and mechanical functionality, and thus, the complementary importance of chemical and topographical changes in the further development of orthopedic biomaterials (Aruna et al., 2017; Balas et al., 2024).

Figure 1. Case studies of orthopedic implant materials in humans (Aruna et al., 2017; Balas et al., 2024).

The adoption of ceramic coatings, such as bioactive glasses and silicate-based ceramics, is of special importance because of their capability to establish chemical bonding with the surrounding tissues, resulting in the integration of the surrounding tissues, thereby leading to healing. Moreover, the coatings may have antibacterial qualities, which lessen the chance of infection after implantation (Balla et al., 2013).

Figure 2 shows the preparation and evaluation of porous alumina coatings on titanium substrates for bioceramic bone plating, focusing on the corrosion resistance and biocompatibility. Anodizing in sulfuric or phosphoric acid electrolytes forms a nanostructured Al2O3 layer on titanium by applying a voltage between aluminum (anode) and titanium (cathode). The resulting porous alumina, containing sulfate or phosphate ions, was characterized by immersion in simulated body fluid (SBF) to assess ion release, calcium phosphate deposition, and electrochemical corrosion behavior at 37 °C using a three-electrode potentiostat. SBF immersion tests track the controlled release of therapeutic Al3+ and surface adsorption of Ca2+ and CO32-, which promote biomineralization. Corrosion experiments demonstrated increased passivation and reduced leaching of metal ions because of the ceramic barrier. In vitro cell adhesion experiments indicated that osteoblasts adhered to and spread on the porous oxide surface (Matijosius et al., 2025).

Figure 2. Corrosion and biocompatibility of bioceramic alumina coatings (Matijosius et al., 2025) CC-BY 4.0.

This enhanced integration also results in better patient outcomes and increases the longevity of implant functionality, as it improves the overall stability of the implant and the healing process (Abate et al., 2021).

Bioactive and biopassive surfaces play an important role in biomedical applications, particularly in the improvement of hemocompatibility and functionality of medical equipment. In biopassive surfaces, the objective is to reduce biological interactions, whereas in bioactive surfaces, biological systems actively interact with the surfaces to develop certain interactions. These two classes of surfaces possess their own roles and advantages in medical and biomaterial applications, as indicated in different studies (A et al., 2024).

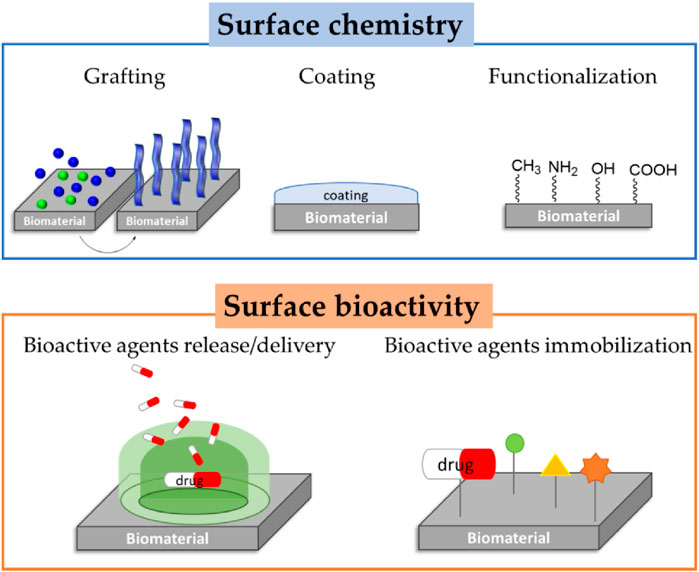

Figure 3 shows two complementary strategies for tailoring biomaterial surfaces. The top section, surface chemistry, encompasses three approaches: grafting, where functional molecules or polymers chemically attach to the substrate to impart specific interfacial properties; coating, wherein a discrete layer of material uniformly covers the biomaterial to modify its surface characteristics; and functionalization, which introduces discrete chemical groups (–CH3, –NH2, –OH, –COOH) to enable targeted interactions. The lowest tier, surface bioactivity, compares agent release/delivery, where encapsulated drugs are progressively freed off the surface to obtain local therapeutic impact, to agent immobilization, where bioactive molecules (drugs, proteins, peptides) are permanently linked to the surface to induce cell adhesion, cell signaling, or antimicrobial activity. The combination of these strategies enables the tight regulation of the chemical and biological activities of biomaterial interfaces (Sánchez-Bodón et al., 2023).

Figure 3. Schematic representation of biopassive and bioactive surfaces (Sánchez-Bodón et al., 2023).

Surface treatments, such as yttria-stabilized zirconia and alumina-zirconia compounds, are also very strong and biocompatible, which are associated with long-term durability. These high-tech ceramic finishes offer high wear resistance and resistance to all the chemicals in the mouth. They also improve the aesthetic results of a patient because of their ability to imitate the color of natural teeth and their transparency. Moreover, there is ongoing research on novel surface modifications to enhance the speed of osseointegration and decrease the occurrence of peri-implantitis (Abdulghafor et al., 2023).

Figure 4 illustrates the biomechanical structure of a hip prosthesis, displaying the key components and forces involved in the hip joint function. The prosthesis has an acetabular component that fits into the hip socket, a ball (femoral head) that fits into the acetabular cup, and a stem that fits into the femoral canal. The diagram illustrates the resultant joint reaction force produced by the abductor lever arm mechanism (produced by the abductor muscles), forming a moment arm around the hip joint. Such a lever system plays an important role in stabilizing the pelvis during walking and weight-bearing, where prosthetic devices mimic the natural biomechanics of the hip joint and deliver long-term and stable functionalities to patients with hip joint disorders (Mirza et al., 2010).

Figure 4. Schematic of the Joint Reaction Force generated by the abductor lever arm (Mirza et al., 2010) CC-BY 4.0.

Antibacterial agents, such as ceramic coatings, can be designed to have anti-bacterial properties that are essential in avoiding biomaterial-related infections, which is a widely encountered problem in dental and orthopedic implants. These antibacterial activities can be accomplished in different ways, such as the use of metal ions or nanoparticles with known antimicrobial activities (Abdullah et al., 2023).

Hydroxyapatite (HAp) is a crucial aspect of biomaterials because of its compositional resemblance to human bone, which makes it a perfect product for different biomedical applications. Its biocompatibility, bioactivity, and osteoconductivity are some of its main characteristics that make it suitable for applications in orthopedics, dentistry, and tissue engineering. The adaptability of HAp is also promoted by the possibility of producing HAp of various shapes and mixing it with other substances to add more properties and broaden the scope of its use (Behera et al., 2023).

Figure 5 presents the crystal structure of hydroxyapatite (HAp), a key inorganic component of bones and teeth. HAp exhibits a hexagonal lattice with ions arranged in a highly ordered pattern. PO43- has oxygen atoms (green) and phosphorus atoms (dark red) attached to it in tetrahedron units scattered all over the lattice. The calcium ions are positioned in two locations: columnar positions (blue) that are oriented along the hexagonal axis and screw axis positions (yellow) between the tetrahedra, which offer stability and charge balancing. Hydroxyl groups (white and green) are placed in columnar channels, which add to the peculiarities of HAp in terms of bioactivity and ion exchange capacity. This precise atomic arrangement underpins HAp’s role of HAp in biomineralization, osteoconductivity, and compatibility with medical implants and dental materials (Zhang et al., 2022).

Figure 5. Crystal structure of HAp (Zhang et al., 2022) CC-BY 4.0.

This review summarizes the available research results to identify the impact of these surface modification methods on important characteristics, such as corrosion resistance and osseointegration. This review can be used to determine the most effective coating schemes and materials, compare their relative merits, and identify the mechanisms by which they enhance the longevity of implants and biological integration. This review is also aimed at determining research gaps, clinical translation challenges, and future innovation opportunities in coating technologies, thus informing the generation of next-generation biomaterials with surface properties that optimize surface design in orthopedics and dentistry.

2 Bio-compatible property

The rising popularity of bio-implants is fueled by the effects of customized, effective, and biocompatible remedies for different ailments. Bio-implants are designed and produced using sophisticated procedures that incorporate new and improved technologies for 3D printing and additive manufacturing. These technologies can be used to design a complex structure that can address certain biomechanical and biological needs, allowing their multifunctional use in the medical sphere (Abdulwahab et al., 2019).

As shown in Figure 6, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed dynamic interactions between cells and biphasic α,β-tricalcium phosphate ceramic surfaces over time. Some rounded cells attached loosely to the rough ceramic after 1 day (a), which is an indication of initial attachment. By the fourth day (b), there were several spherical cell clusters evenly distributed across the surface, indicating proliferation and initial deposition of the extracellular matrix. Cells became widely dispersed and released lamellar extracellular sheets after 10 days (c) to produce tightly packed, plate-like mineralized nodules, which are indicators of active differentiation. At 30 days (d), the surface was coated with stable, protruding cell processes closely connected with thicker mineral precipitates and fibrillar networks, which indicates a high level of maturation and mineral cohesion of the matrix. Taken together, these images indicate sequential cell adhesion, cell multiplication, cell differentiation, and biomineralization on 8 Ca 2.5 Pa ceramics, which highlights their ability to assist in every stage of osteogenesis, including the first adhesion phase up to mineral deposition (Safronova et al., 2020).

Figure 6. SEM images of the surface of biphasic α,β-tricalcium phosphate ceramics after culturing for 1 (a), 4 (b), 10 (c), and 30 (d) days (Safronova et al., 2020) CC-BY 4.0.

The mechanical properties and biological integration of implants are improved through the use of novel lattice structures in bio-implants, such as bio-absorbable PLA. These frameworks have a natural tissue architecture and are intended to enhance integration and functionality. These lattice structures can also be incorporated to customize the properties of an implant to fit particular patient or anatomical requirements (Abduo, 2014). Such personalized solutions can result in the best healing process and minimize complications related to implant rejection or failure. Moreover, the bioabsorbable property of PLA-based implants has the benefit of degrading gradually over time; thus, the implant may not be required to undergo secondary surgery to remove the implant, and consequently, the body can regenerate natural tissues (Afzal, 2014).

Figure 7 provides a comprehensive overview of biomaterial classifications and their biocompatibility profiles for medical applications. Section (A) shows the biocompatible behavior, distinguishing the materials as bioinert (minimal tissue interaction), bioactive (stimulates cell response), biodegradable (breaks down in the body), and bio-resorbable (gradually absorbed and replaced by natural tissue). Section (B) singles out metallic biomaterials, such as magnesium and iron alloys, to be used in implants that naturally degrade over time. Part (C) is devoted to ceramic materials, distinguishing between bioinert materials such as alumina and zirconia, and bioactive materials such as hydroxyapatite and apatite-glass composites that have demonstrated superior wear resistance and osteoconductivity in dental caps, joint bearings, and hip replacements. Section (D) provides information on polymer materials, such as natural biodegradable polymers (PLA, PLLA, PGA) and natural polymers (collagen, chitosan), with an emphasis on their use in fixation plates, tissue scaffolds, and drug delivery systems. These materials, in combination, create a versatile instrument for contemporary regenerative medicine and orthopedic engineering (AD et al., 2024).

Figure 7. (A) Diagrammatic representation of biocompatible behavior, (B) Metallic materials, (C) Ceramic materials, (D) Polymer materials (Ad et al., 2024) Open Access.

In additive manufacturing, generative design techniques designed to optimize support structures are based on biological strategies that use less material and less time after processing but still produce structural designs that are as robust as coral or tree branches. These approaches have the potential to produce highly efficient organic-appearing supports, which are attractive and efficient, by successively refining the support geometry according to the distribution of the stresses and material constraints. These optimized structures can not only reduce material waste but are also easier to remove during post-processing, and this offers considerable time and cost savings in the additive manufacturing workflow (Alqutaibi et al., 2025). Patient-specific implants can be produced using techniques such as electron beam melting and laser powder bed fusion, where cellular architecture and porosity are carefully tailored to reduce stress shielding and increase mechanical properties (Annaji et al., 2024).

Figure 8 shows that Panel (A) compares the surface roughness (Ra) of the non-coated (reference) and silicon carbide-coated (SiC) samples, showing that the SiC coating slightly reduces the average roughness from approximately 10 to 8 nm, with overlapping standard deviation bars indicating comparable variability. Panels (B) and (C) present 10 μm × 10 µm atomic force microscopy topography maps for the reference and SiC-coated surfaces, respectively. The uncoated surface (B) exhibits deeper valleys and higher peaks, spanning heights from −68.6 nm to 43.0 nm, whereas the SiC-coated surface (C) shows a smoother profile with narrower height distribution (−28.4 nm–22.1 nm) and fewer pronounced asperities, confirming the coating’s smoothing effect on the substrate (Afonso Camargo et al., 2024).

Figure 8. Roughness means values and standard deviation in non-coated (reference) and coated (ref SiC) samples (A). Atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of surface topography of non-coated (B) and coated SiC (C), with amplifications of 10 µm.

These new production techniques allow for the development of implants with optimal pore size, distribution, and interconnectivity, which facilitates improved osseointegration and bone ingrowth. Being able to customize the structure of the implant down to the microscale means that there will be a better distribution of load and that implant loosening with time will be minimized. Moreover, the possibility of customizing these methods opens new possibilities for creating implants that are closer to the real bone structure, which may have more favorable long-term results in patients (Arias-González et al., 2022). This technique applies to the formation of multilayered structures, including artificial esophageal and blood vessel implants, which are analogous to the complicated layers of natural tissues. These frameworks are intended to preserve the interlayer separation and porosity that supports biological activity and implantation (Attarilar et al., 2021).

3 Advanced coating techniques

Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) (Battistoni et al., 2023), electrochemical deposition (ED) (Li et al., 2003), plasma spraying, sol-gel, and hydroxyapatite (HA) (Beig et al., 2020) layer deposition is are technique that is commonly used to overcome the constraints of metals, including low osseointegration and corrosion under physiological conditions.

Figure 9 illustrates the chemical vapor deposition (CVD) process for depositing hydroxyapatite (HAp) coatings on biomedical implants. The system is characterized by two precursor furnaces that hold calcium and phosphate sources, which are heated to produce volatile compounds that are conveyed to a central mixing chamber through controlled gas flows. The supply of argon provides an inert carrier gas atmosphere, and the oxygen supply allows oxidation reactions that are required to form HAp. The substrate to be coated was placed on a heating stage that was part of a quartz tube reaction chamber, and the temperature was controlled by thermocouples. A vacuum forms low-pressure conditions that are controlled to ensure the uniform movement of precursors and their deposition (Beig et al., 2020).

Figure 9. Schematic of HAp coating using Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) (Beig et al., 2020).

The flowchart in Figure 10 illustrates the comprehensive fabrication and evaluation process of hydroxyapatite-coated titanium scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Porous titanium scaffolds were additively manufactured starting with a 3D computer-aided design model. These scaffolds were prepared on the surface to receive hydroxyapatite coating through two different techniques: electrochemical deposition (EDHA) and plasma spray hydroxyapatite (PSHA), which produce Ti/HA composite scaffolds (Sun et al., 2021).

Figure 10. Fabrication of hydroxyapatite (HA) coatings on 3D-printed titanium (Ti) scaffolds using electrochemical deposition and plasma spraying and in vitro and in vivo evaluations of bone integration (Sun et al., 2021) Open Access.

Plasma-sprayed and sol-gel-derived ceramic coatings are new methods of surface modification that are highly effective for enhancing the performance of implants in two different ways. Coatings of hydroxyapatite resemble natural bone mineral composition, enable direct chemical bonding of the coating with the surrounding bone tissue, and promote cellular attachment (Candidato et al., 2017). Bioactive glasses dissolve to release therapeutic ions that trigger osteoblasts to develop new bones at the implant interface. These ceramic layers simultaneously serve as protective layers, avoiding the leaching of metallic ions and corrosion under physiological conditions (Awasthi et al., 2021).

Table 1 demonstrates the diversity of approaches used to create bioactive HAp coatings for medical implants.

This is a detailed study that has clarified state-of-the-art hydroxyapatite (HAp) coating technologies in biomedical implants by relating the processing parameters, substrate choice, and coating properties (Chen et al., 2018). Different microstructures (needle-like and lamellar crystals, dense and adherent layers) are generated by electrodeposition, plasma spraying, sol-gel, and biomimetic techniques, which are determined by the electrolyte composition, temperature, and kinetics of deposition. Substrate materials, including Ti6Al4V alloys, stainless steels, and magnesium alloys, affect the interfacial bonding, resistance to corrosion, and mechanical compatibility. Crystallinity, thickness, and porosity are regulated by optimizing factors such as pH, dopant ions, and thermal treatment. This understanding provides a personalized HAp coating to coordinate the bioactivity, adhesion of the coating, and durability over time to achieve improved clinical outcomes (Deng et al., 2023a).

4 Mechanical and antibacterial properties

Recent research has emphasized the use of composite and functionally graded ceramic coatings to meet the conflicting needs of mechanical performance and biological activity. Composite coatings make use of hydroxyapatite or bioactive glass as the primary phase with secondary phases, including titanium dioxide, silver nanoparticles, or polymer matrices, to increase toughness, adhesion, and add antibacterial capability. Functionally graded coatings progressively change the composition or porosity between the metal interface and the outer surface, matching the stiffness to minimize stress concentrations without removing bioactive layers to promote bone ingrowth. These engineered gradients enhance mechanical stability during cyclic loading, offer sustained ion release for antimicrobial protection, and enhance uniform osseointegration, thus increasing the duration of implants and minimizing infection risks without hurting strength (Deng et al., 2023b).

Figure 11 load–displacement graph comparing the mechanical stiffness characteristics of different hip stem configurations against the intact femur. The solid Ti6Al4V stem demonstrated the highest stiffness of 2.758 kN/mm, creating a steep linear relationship between the applied load and displacement. This high stiffness significantly exceeds the natural range (1.163–1.446 kN/mm), indicating the potential for stress shielding where the implant bears excessive load relative to the surrounding bone. In contrast, the solid PEEK stem exhibits a much lower stiffness of 0.276 kN/mm, falling below the natural femur range, which could lead to insufficient load transfer and implant stability issues. The intact range of the femur is the best mechanical condition in bone health, presenting the difficulty of aligning implant stiffness with natural bone properties to reduce complications such as bone resorption or implant failure (Naghavi et al., 2022).

Figure 11. Load–displacement graph for the Ti6Al4V stem, PEEK stem, and intact femur. The stiffness value of each configuration is presented above the respective slopes in the diagram (Naghavi et al., 2022) Open Access.

The development of coatings on medical devices and implants has great potential for improving the functionality and safety of devices and implants. Nevertheless, difficulties related to coating adhesion, long-term durability, and the possibility of transferring data obtained in vitro to clinical outcomes are still common. Such challenges are important because they affect the efficacy and dependability of medical devices (Bacchelli et al., 2009).

Adhesion coatings can be important for the life and functionality of medical device coatings. Weak adhesion may cause delamination, which impairs the coating protection. Improvement methods, such as radio frequency magnetron sputtering (RFMS), have been developed to enhance adhesion by allowing the coating to be applied at lower temperatures, which reduces thermal stress and improves bonding with the substrate (Bai et al., 2019). Coatings require durability because their protective properties are not required. Hydrogel coatings have been effective in lowering bacterial adhesion and blood clotting; however, their stability over time in physiological environments requires further research. Additionally, bioactive coatings on metallic implants are burdened by wear and corrosion problems that may deteriorate the performance of the implant over time (Baino et al., 2019).

Figure 12 illustrates the synthesis and bone regeneration mechanism of the CaCuMg-PEM-Col microcapsules for the treatment of bone defects. The fabrication began with co-precipitation to form CaCuMg-CO3 particles containing therapeutic metal ions. These particles undergo layer-by-layer assembly with polyelectrolyte multilayers, specifically PEI, followed by alternating PSS and PAH layers (PEI/[PSS/PAH]5PSS), creating a controlled-release coating. Finally, collagen was incorporated into the CaCuMg-PEM-Col microcapsules. When applied to bone defect areas, microcapsules create a regenerative microenvironment by releasing beneficial ions: Ca2+ for mineralization, Cu2+ for angiogenesis and antimicrobial activity, and Mg2+ for osteoblast activation. The polymer layers (PEI, PSS, and PAH) and collagen matrix provide structural support and biocompatibility. The heliocentric image reveals intricate cellular interplay, such as osteoblast cell growth, osteocytic maturation, incorporation of blood vessels, and gradual mineralization of the bone tissue, which eventually results in ideal bone tissue regeneration and repair of bone defects (Fa et al., 2022).

Figure 12. Schematic illustration of the fabrication process of CaCuMg-PEM-Col microcapsules [CaCuMg-CO3 particles + PEI/(PSS/PAH)5PSS + Col] and their effects on bone regeneration (Fa et al., 2022) Open Access.

Although a variety of coatings show excellent results in vitro, it is difficult to translate these results to clinical achievement. Outcomes may be influenced by factors, such as the complexity of the in vivo environment and variables with patient specificity. Antimicrobial coatings have demonstrated efficacy in the prevention of infection in animal models; however, their application in human clinical trials has yielded poor results. In addition, a shift between in vitro and in vivo environments tends to unveil some unanticipated complications, such as immune reactions or unanticipated interactions with biological tissues (Ban, 2021).

Figure 13 illustrates the atomic layer deposition (ALD) process for coating titanium dioxide (TiO2) onto oxygen-plasma-treated polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) substrates. The construction begins with the cyclic process of surface modification in the first half, where the PMMA substrate is pretreated with tetrakis(dimethylamido)titanium (TDMAT) in an argon atmosphere, which creates reactive sites in which titanium atoms are bound to the surface. The precursor argon purge eliminated the surplus precursor molecules. The second half encompasses active site regeneration with an oxidizer pulse utilizing a blend of oxygen and ozone (O3/O2 Mix/Ar), which changes the titanium sites into titanium dioxide, restoring the reactive hydroxyl and amine groups on the surface. The second oxidizer purge was used to close the cycle. The legend shows the hydrogen (H), amine groups (R2N), oxygen (O), and titanium (Ti) atoms involved in the process. This sequential, self-limiting reaction mechanism enables precise, uniform, and conformal TiO2 thin film deposition on complex polymer surfaces for applications in biomedical coatings and surface functionalization (Chee et al., 2022).

Figure 13. Schematic of ALD reaction on O-plasma-treated PMMA using TDMAT and an O3/O2 mixture (Chee et al., 2022) Open Access.

Despite this, continuous research and development have been conducted to address these problems. New developments in the field of coating materials and methods of application can eliminate the existing constraints. However, it is important to consider the complexity of biological systems and the variability of patient response when creating and testing new coatings. This comprehensive view can be used to overcome the disconnect between laboratory success and clinical use, which will eventually lead to better patient outcomes (Wandra et al., 2022).

As shown in Table 2 mechanical properties of bone tissues and materials used for orthopedic implants are crucial for ensuring the success and longevity of implants.

This detailed discussion shows that orthopedic biomaterials continue to evolve with a balance that is vital for mechanical compatibility with bone tissue and sufficient strength to sustain implants over the long term. This information identifies the benefits of the developed titanium alloys and engineered porous structures in achieving optimum biomechanical performance (Beig et al., 2020).

5 Types of ceramic-based surface treatment

This is important because the thematic surface treatment of metallic biomaterials, including plasma spraying, sol-gel, and deposition of a hydroxyapatite (HA) layer, is important for improving the performance of implants. These therapies are designed to enhance biocompatibility, corrosion resistance, and mechanical incorporation of implants into the bone tissue. Both approaches have advantages and disadvantages, which are examined in the following sections (Dubnika et al., 2017).

Plasma spraying is popular owing to its low cost and suitability for creating thick coatings. This process was achieved by melting the ceramic powder and spraying it on the substrate, creating a coating when allowed to cool. This procedure is especially useful for HA coatings, which increase the osteoconductivity and corrosion resistance of implants. Nevertheless, the temperatures involved are high, which means that HA can degrade, adding to the structural integrity and bioactivity of the biominerals (Esposito Corcione et al., 2017).

Figure 14 provides a comparative overview of powder-based plasma spray and high-velocity oxy-fuel (HVOF) coating processes. On the left, the plasma gun primarily applies radial feedstock injection, and at higher thermal energies, effectively melts the powder particles. In contrast, the HVOF gun uses lower thermal and higher kinetic energy (supersonic combustion exhaust) axial feedstock injection and produces a denser coating. The main panel includes a description of the path the particles follow during the flight: the feedstock goes through the gradient of thermal and kinetic energies, which are separated into zones I (the highest), II, and III (the lowest). Droplet size sort of its own way--the largest droplets will be deposited closer to the source, whereas the smallest droplets will travel the farthest. Momentum is also zonal in nature. In the right panel, the results of the deposition are displayed; the unmolten, semi-molten, and fully molten particles are deposited at various angles, the smaller the particle, is closer to the shallow angle, and the larger the particle is perpendicular. This affects the formation of voids and densification of the layers in the end coating structure (Mittal and Paul, 2022).

Figure 14. Schematic representation of the powder-based plasma and HVOF spray processes (Mittal and Paul, 2022) Open Access.

Figure 15 shows the bioactive coating effects on zirconia-toughened alumina ceramic implants through scanning electron microscopy analysis of cancellous bone integration. Panel A shows a cylindrical implant specimen (8.0 mm diameter, 15 mm length), while Panel B illustrates implant placement in the humerus and femur bones. The SEM images compare the surface morphologies of different bioactive coatings: NC (negative control), CM, HA (hydroxyapatite), dip-coated bioglass (DipBG), and sol-gel bioglass (SGBG) at varying magnifications (×30, ×200, and ×3000). The coated samples exhibited greater surface roughness and porosity than the control, with SGBG being superior in terms of microstructural characteristics, such as the homogeneity of the coating distribution and the optimum pore architecture. Such bioactive coatings enhance the bone-implant interface with improved bone-implant interaction, serving to mediate calcium phosphate deposition and osteoblast adhesion, ultimately leading to improved bone integration of implants in cancellous bone conditions to enhance implant stability and survival (Pobloth et al., 2019).

Figure 15. Implant design, implantation sites and characterization of bioactive coatings via SEM. SEM images of coated surface in magnifications ×30, ×200, and ×3000. Textured cylindrical ceramic implant (A). Used implantation sites in cancellous bone of the left proximal and distal humerus and both left femoral condyles (B); dark pink = lateral approach; light pink = medial approach). SEM images of NC and coating groups (C–Q).

Sol-gel methods enable uniform nanostructured coatings to be deposited at low temperatures, enhancing coating homogeneity and bioactivity. The sol-gel procedure involves conversion of the solution into a gel to create a thin layer and even coating. This is beneficial because of its low processing temperature and its capability to cover complex geometries. Sol-gel surfaces can enhance surface roughness and adhesion of HA on metallic surfaces, a property essential to implant stability (Ak and Çiçek, 2021).

Figure 16 illustrates the multilayer sol-gel coating method applied to the TiAlV alloy substrates for enhanced performance. The process starts with the preparation of precursor solutions containing TEOS, GPTMS, and TIP, often combined with solvents like C3H7OH and SiO2 particles to optimize film properties. The surface properties were assessed using water contact angle measurements, which indicated improved hydrophilicity and enhanced biological compatibility. The structural properties were characterized via X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), confirming the multilayer formation and material phases. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images revealed the topography and uniformity of the coatings. Specific functional nanoparticles, such as hexagonal boron nitride (hBNNPs) and titanium nitride (TiNNPs), are incorporated into layers to confer antibacterial activity. The integration of TiN and BN phases contributes to superior surface features, improved mechanical stability, and potent antibacterial properties, making multilayer sol-gel coatings highly desirable for biomedical implant surfaces (Matysiak et al., 2025).

Figure 16. Multilayer Sol-gel coating method (Matysiak et al., 2025) Open Access.

The use of sol-gel coatings is known to be versatile and environmentally friendly, although in most cases, further sintering stages are required to improve the mechanical characteristics (Zheng et al., 2022). Sintering is an operation in which the coated substrate is heated, and is instrumental in enhancing the hardness, adhesion, and durability of these coatings. This is necessitated by the fact that the sol-gel process, although efficient in the formation of coatings at relatively low temperatures, might not be robust enough to obtain the desired mechanical properties unless further treatment is performed (Almeida et al., 2013).

As shown in Table 3, studies have demonstrated enhanced osseointegration rates and reduced infection risks with ceramic-coated 3D-printed implants compared with uncoated alternatives. Further studies should be conducted to streamline the methods to achieve a balance between the mechanical and biological characteristics of the coatings.

Such an extensive discussion provides insight into the direction of hybrid manufacturing strategies integrating additive manufacturing into high-technology surface modification, which is the future of next-generation biomedical implantation that is optimized in terms of biological and mechanical performance.

5.1 Impact on corrosion resistance

Ceramic surface finishes serve as physical and chemical protective layers, which can greatly inhibit the corrosion rates of metallic implants under biological conditions. The electrochemical corrosion behavior of metals and alloys is not a simple process that is affected by several factors. The surface features, surrounding environment, and the material structure are all important in terms of the rate and degree of corrosion. Knowledge of these mechanisms is important for devising efficient corrosion prevention approaches and enhancing the life of metallic structures used in various applications (Benedetti et al., 2017).

Figure 17 shows potentiodynamic polarization curves comparing the electrochemical corrosion behavior of as-extruded magnesium-strontium alloys with varying strontium content against pure magnesium in a standard corrosive environment. The curves plot the potential (V vs. SCE) against the logarithmic current density, revealing the distinct corrosion characteristics for each composition. Pure Mg exhibits the most negative corrosion potential and the highest current density, indicating poor corrosion resistance. The Mg-Sr alloys demonstrate improved electrochemical performance, with Mg-0.25Sr, Mg-1.0Sr, Mg-1.5Sr, and Mg-2.5Sr showing progressively enhanced corrosion resistance through more positive corrosion potentials and reduced current densities. Strontium addition effectively shifts the polarization behavior toward more noble potentials, suggesting that strontium alloying significantly improves the corrosion resistance of Mg, making these alloys more suitable for biomedical implant applications where controlled degradation rates are essential (Liu et al., 2014).

Figure 17. Potentiodynamic polarization curves of as-extruded magnesium–strontium (Mg–Sr) alloys and pure Mg (Liu et al., 2014) Open Access.

It has been observed that surface treatments made of ceramics such as hydroxyapatite (HA), titanium dioxide (TiO2), zirconium dioxide (ZrO2), and bioactive glass coatings enhance the corrosion protection of metallic biomaterials by a wide margin. These coatings serve as isolation barriers between the metal substrate and corrosive body fluids and prevent the release of metal ions (Mehta and Singh, 2023). Ceramic coatings provide a physical and chemical barrier between the implant surface and the physiological environment and reduce direct contact and electrochemical interactions that cause corrosion. In addition, bioactive ceramics, such as HA and bioactive glass, can be used to facilitate a corrosion-resistant apatite layer on top of the implant surface, which will further increase the corrosion resistance. These ceramic coatings have enhanced corrosion resistance capabilities that allow the structural integrity and biocompatibility of metallic implants to persist over long periods in vivo, resulting in improved long-term clinical outcomes. Nevertheless, the coating thickness, adhesion strength, and possible defects should be controlled to maximize protective effects (Melero et al., 2018).

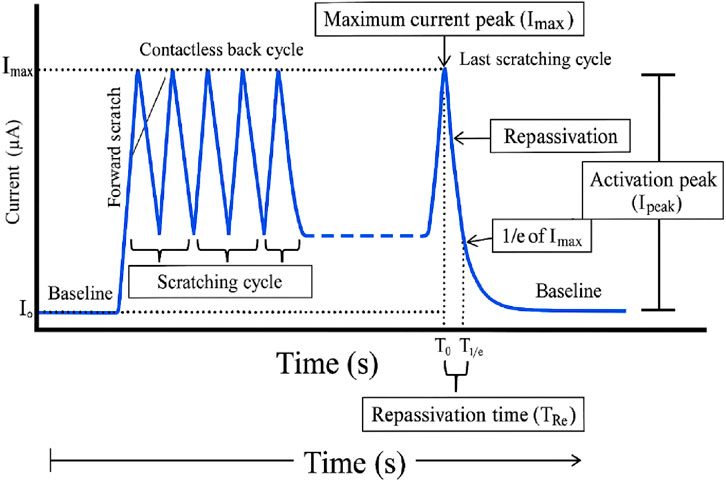

Figure 18 shows the electrochemical scratch test used to assess the surface repassivation kinetics. Initially, the current rests at a low baseline (I0) until the first forward scratch cycle disrupts the passive film, causing current spikes during repeated scratching and contactless back cycles. After the final scratch, the current reaches a maximum peak (Imax), marking complete passive layer removal. Upon halting mechanical damage, the current decays as the surface repassivates, dropping to 1/e of Imax over the repassivation time (Tᵣe), measured between the onset of passive recovery (T0) and the time to reach 1/e current (T1/e). The activation peak (Ipeak) quantifies the initial repassivation rate (Sawada et al., 2017).

Figure 18. Typical fretting-corrosion plot (Sawada et al., 2017) Open Access.

Hydroxyapatite (HA)-based composites coated with either titanium dioxide (TiO2) or zirconium dioxide (ZrO2) have demonstrated better corrosion resistance than single-phase ceramic coatings in metallic implants. Research has established that HA-TiO2 and HA-ZrO2 composite coatings have a significant positive impact on the density of the corrosion current and polarization resistance of titanium and stainless steel implants in simulated body fluids. The synergistic nature of HA with TiO2 or ZrO2 produces a coating with superior corrosion protection and bioactivity, which contributes to the improved long-term stability and performance of metallic implants in vivo (Mocanu et al., 2022).

Figure 19 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive spectroscopy characterize the corrosion behavior of the Mg-0.8Ca specimens after simulated body fluid exposure. The alloy surfaces shown in panels (a), (b), and (c) are bare and have broken and uneven corrosion layers. The EDS spectrum of this sample showed high concentrations of magnesium, oxygen, phosphorus, and calcium. Figure (d)–(f) display the HA2-coated surface with fewer cracks and discrete calcium phosphate deposits; EDS validates the increased calcium and phosphorus signals with fewer magnesium corrosion product peaks. Panels (g–i) depict the BG2-coated specimen, showing a uniform granular bioactive glass layer with little surface degradation. The EDS spectrum reveals that there are other silicon peaks in addition to calcium and phosphorus, proving that bioactive glass has been incorporated successfully and that the surface protection against corrosion has been enhanced (Bița et al., 2022).

Figure 19. (a,b,d,e,g,h) SEM images and (c,f,i) EDS spectra collected after the corrosion tests performed in SBF on the (a–c) bare and (d–f) HA2- and (g–i) BG2-coated Mg-0.8Ca specimens (Bița et al., 2022) Open Access.

Thick coatings of ceramics tend to have a more effective level of corrosion protection because they constitute a stronger barrier between the metal substrate and the corrosion environment. However, excessive thickness of coatings can result in poor adhesion or cracking. The benefit of the decreased porosity in the ceramic coating is that it leads to a higher resistance to corrosion by reducing the routes by which the corrosive media can reach the metal surface. Dense and nonporous coatings act as more effective barriers (Bhand et al., 2023).

Close bonding between the metal substrate and the ceramic coating is essential to protect against corrosion in the long term. A lack of adhesion may cause coating delamination, exposing the underlying metal may be exposed. The chemical composition of the ceramic coating determines its corrosion-resistance properties. To illustrate, hydroxyapatite layers are biocompatible, but perhaps do not have as much corrosion resistance as chemically stable ceramics such as alumina or zirconia (Mocanu et al., 2023).

Cleaning and preparing the metal surface before coating deposition increases the adhesion and quality of the coating, thereby increasing its corrosion resistance. Methods employed to deposit ceramic coatings (e.g., plasma spraying, sol-gel, atomic layer deposition) influence coating density, uniformity, and adhesion, which in turn influence corrosion protection. Porosity can be minimized and coating properties can be enhanced by heat treatment or sealing operations following coating deposition (Bhojak et al., 2023). Nanostructured or graded coatings offer better corrosion protection than microstructured coatings. The inherent corrosive nature (pH, temperature, and mechanical stresses) affects the effectiveness of a certain coating in resisting corrosion. It is important to reduce cracks, pinholes, and other imperfections in the coating because they may be a starting point for localized corrosion. The optimization of these factors enables the ceramic surface to be used effectively as an anticorrosive coating for metallic biomaterials without loss of biocompatibility or induction of osseointegration (Blázquez-Carmona et al., 2021).

5.2 Enhancement of osseointegration

Coatings made of ceramics, especially those with hydroxyapatite (HA) and bioactive glass, are valuable in facilitating the quick formation of bones, as well as in increasing bone-implant bonding. These layers unite the mechanical capability of the metal implants with the biocompatibility and bioactivity of the ceramics and enable implants to integrate into the bone as well as enhance the life of the implants. It has also been indicated that the incorporation of HA and bioactive Glass in the ceramic coatings on implants has a major impact in improving the mechanical and the biological properties of implants rendering them more viable in clinical practice (Mohammadi et al., 2007).

HA Coatings are very common because they are chemically similar to bone minerals; therefore, they exhibit high bonding with bone tissue. Research has shown that HA surfaces can improve mechanical characteristics, including push-out force and adhesive shear strength, which results in an increase in the rate of osseointegration. HA coatings also work best in transferring motion-induced fibrous membranes to bony anchorage even under unsteady mechanical conditions (Boban et al., 2024).

Figure 20 schematic contrasts an uncoated CoCrMo alloy (a) with CoCrMo bearing a SiN0.(std) Coating (b). In (a), the bulk metal comprises Co, Cr, and Mo. A thin passive layer of chromium oxide and hydroxide formed at the surface beneath the adsorbed carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, calcium, and sodium species. In a physiological solution, metallic ions (Co2+, Cr3+, Mo 3 +) leach into the fluid, while solution ions adhere to the interface. In (b), the SiN0.8(std) coating replaces the passive film, built from silicon–nitrogen, silicon–oxygen, and silicon–silicon bonds, with occasional hydroxyl and argon entrapment. This dense, chemically inert layer minimizes metal ion release and reduces the adsorption of solution elements, thereby enhancing the corrosion resistance and biocompatibility (Pettersson et al., 2016).

Figure 20. Schematic sketch of bulk, surface, and solution elements, ions, bonds, and structures seen in this study in (a) CoCrMo and (b) SiN0.8(std) coating on a CoCrMo substrate (Pettersson et al., 2016) Open Access.

Special coatings on the surfaces of implants have shown considerable improvement in the process of enhancing their ability to be integrated with the body. These surfaces act as bioactive interfaces that stimulate a cascade of cellular events that are essential for successful implant integration. First, they enable the adsorption of proteins, which provides a favorable microenvironment for the attachment of cells. The layer of this protein serves as a link between the implant surface and the surrounding cells, which allows greater adhesion of cells (Bružauskaitė et al., 2015). The coatings then help in the proliferation of cells, which can further grow into osteoblasts and other bone-forming cells. In addition, these surface changes trigger osteogenic differentiation, which promotes the growth of mature bone-forming cells. The aggregation of these mechanisms leads to increased osseointegration, as shown by in vitro experiments in cell cultures and in vivo experiments in animal models. This enhanced communication between the implant and bone tissue eventually results in enhanced implant stability and long-term success (Bonda et al., 2015).

The most important issues that have a significant impact on the biological response to biomaterials are the surface topography, chemistry, and wettability. Micro-and nanoscale surface topography influences cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation, which is due to the physical signaling of the physical environment provided by the surface topography. Surface chemistry defines biomolecules that are capable of adsorbing to a material, which facilitates cell-material interactions (Chen et al., 2024). Wettability affects the extent of protein adsorption and cell attachment; moderately hydrophilic surfaces usually support better cell adhesion than highly hydrophobic or hydrophilic surfaces. These surface properties are synergistic and facilitate the formation of a pro- or anti-biological biointerface. Controlling these parameters enables the development of biomaterials that can be used to stimulate desired cellular responses and tissue regeneration and enhance the overall functionality and durability of medical implants and devices. Therefore, surface topography, chemistry, and wettability should be carefully considered and controlled to produce biomaterials with improved biocompatibility and functionality (Chen et al., 2014).

5.3 Challenges and innovations

Applications, such as poor adhesion, delamination, and long-term durability under physiological loading, are of great concern in the areas of biomaterials, composite materials, and coatings. These challenges arise because of the complex material-environmental relationships that can result in failure over time. It is vital to understand these issues in terms of material performance and life enhancement (Chia and Wu, 2015). Figure 21 illustrates how implant fibrosis and myofibroblast activity drive long-term prosthesis failure via multiple interlinked pathways. Fibrous encapsulation occurs when stimulated myofibroblasts lay down thick collagen about the implant, effectively isolating the implant and inhibiting stable osseointegration. All these processes eventually lead to revision surgery, which highlights the great but underrated importance of myofibroblasts in the fibrotic encapsulation and durability of implants (Noskovicova et al., 2021).

Figure 21. Implant fibrosis and the underappreciated role of myofibroblasts (Noskovicova et al., 2021) open access.

Antibacterial coatings of medical and veterinary implants have focused on the functional grading of coatings, composites, and hybrid coatings, and the introduction of antibacterial agents such as silver (Ag) and cerium (Ce) to reduce the risk of infection. These innovations are intended to improve the antibacterial activity, mechanical characteristics, and biocompatibility of implants to address the major problem of implant-associated infections (Lone and Rahman, 2020). Functionally graded coats have been developed to generate smooth changes in composition or structure, thereby increasing the mechanical and antibacterial properties. An example is given of a dental implant design that uses a layer of silver-coated porous titanium-hydroxyapatite that provides antibacterial action and compatibility with bone tissue in mechanical terms. These coatings are customizable for certain applications, including orthopedic implants, in which they achieve a trade-off between the strength and antibacterial properties (Mrdak et al., 2023).

Figure 22 depicts the multifaceted biochemical mechanism by which XDA/CS/BG/HA/lawsone composite coatings accelerate bone regeneration and inhibit biofilm formation on metallic implants. The composite layer, containing xanthan dialdehyde (XDA), chitosan (CS), bioactive glass (BG), hydroxyapatite (HA), and lawsone, provides a bioactive polymeric interface that assists in the recruitment and differentiation of stem cells. BG and HA are osteoconductive agents that increase the conversion of stem cells into osteoblasts and stimulate the formation of new bone matrix at the fracture site. The coating additionally regulates osteoclast activity, balances bone resorption without overtone destruction of matrix, and promotes the migration of fibroblasts to integrate the tissue. Lawsone and BG add to the antimicrobial effect by releasing the ions that affect the bacterial membrane and preventing biofilm formation, which is involved in the development of implant-associated infections. These synergistic actions lead to rapid osteoblast expansion, regulated resorption, and sustained bone repair, as well as the preservation of a sterile implant environment and minimization of the risk of chronic infection or implant failure (Nawaz et al., 2023).

Figure 22. Proposed mechanism of biochemical action of XDA/CS/BG/HA/lawsone composite coatings facilitates bone regeneration and inhibits biofilm formation (Nawaz et al., 2023) Open Access.

Multifunctionality is achieved using composite and hybrid layers made of dissimilar materials. Titanium implants containing composite hybrid layers composed of silver nanoparticles have demonstrated good antibacterial and corrosion resistance. Ag and ZnO nanoparticles in TiO2 nanotube composite layers have been shown to exhibit improved antibacterial applications with controlled release of antibacterial agents (Das et al., 2013).

Cold spraying and room-temperature deposition processes are being actively investigated to conserve the bioactivity of delicate ceramics, such as hydroxyapatite (HAp), which can be used in medicine (Ajdelsztajn et al., 2005). Such techniques have considerable benefits compared to the old high-temperature process, which frequently results in unwanted modification of material properties. Two of the most notable techniques that enable the deposition of ceramics at lower temperatures, thereby preserving their bioactive properties, are cold spray (CS) and nanoparticle deposition systems (NPDS) (Padilla-Gainza et al., 2022).

Cold spray technology enables the deposition of HAp coatings at temperatures lower than their melting point, thereby maintaining the raw properties and bioactivity of the material. This is important for preserving the integrity of calcium phosphate ceramics in bone-tissue engineering. CS coatings provide increased biocompatibility and bioactivity of implants, which is critical for orthopedic usage (Arabgol et al., 2014). It is cost-effective, environmentally friendly, and appropriate for use in oxygen-sensitive materials. The CS process yields coatings with adhesive and mechanical properties comparable to those of traditional methods such as plasma spraying. This helps improve the longevity and performance of implants (Sandhyarani et al., 2014).

6 Future perspectives and challenges

Biomaterials are hybrid and multilayered coating systems that are meant to improve the functionality of medical implants by blending the properties of various materials. The purpose of these systems is to enhance corrosion resistance, bioactivity, and mechanical properties, which qualifies them for use in different biomedical applications. The organic and inorganic flavors in these coatings enable the development of multifunctional surfaces that meet specific clinical requirements (Davoodi et al., 2021). Multilayer hybrid sol-gel coatings (e.g., featuring TEOS and GPTMS) have been demonstrated to markedly enhance the corrosion resistance of magnesium alloys, which otherwise readily degrade under physiological conditions. The enhanced bioactivity of these coatings is attributed to the development of apatite-like phases, which play a significant role in bone integration (Lin et al., 2019).

Figure 23 compares the mechanical and surface properties of the CoCr and multilayer ceramic (M1, M2, M3)-coated systems. The loaddeflection curves (a) reveal how each system reacts to an increase in extension, with multilayer ceramics having higher values of peak loads (Ffail) at failure than uncoated CoCr, indicating better mechanical bonding. In panel (b), the roughness (Ra) and contact angle of all groups and the bond strength (τ b) are shown. Multilayer ceramics have a rougher surface and average contact angles, which are associated with a stronger bond strength than that of CoCr. These advances are courtesy of the ceramic multilayer architecture, which increases adhesion between the interfaces and alters the surface properties to enhance the mechanical and biological implant performance (Dinu et al., 2024).

Figure 23. Load–deflection curves (a) and bond strength variation (b) of the CoCr multilayer ceramic system (Dinu et al., 2024) Open Access.

The incorporation of hydroxyapatite (HA)-based hybrid coatings on magnesium alloys dramatically increases biocompatibility and osteoconductivity and is effective in reducing corrosion rates. Magnesium alloys are potential materials for biomedical applications because they are biodegradable and can perform mechanical functions, such as bone. These alloys are coated with the natural mineral HA, which enhances their bioactivity and resistance to corrosion. These properties are further improved through the use of hybrid coatings, which are coatings based on HA with other materials, to overcome the limitations of single-layer coatings (Pei et al., 2011). HA coatings on magnesium alloys enhance biocompatibility and osteoconductivity, as the natural similarity of HA to bone minerals also facilitates cell proliferation and differentiation. Research indicates that HA coatings improve the growth of pre-osteoblasts as well as bone-to-implant contact, and therefore, osteointegration is enhanced (Prakash et al., 2021).

Figure 24 outlines the design process for an oblique lateral lumbar interbody fusion (OLIF) cage customized for elderly patients with osteoporosis. Starting from CT-derived statistical models that capture typical vertebral endplate morphologies in osteoporotic spines, a validated finite element (FE) model simulates a range of spinal motions: flexion (21.5%), extension (21.5%), bending (33%), and rotation (24%)to assess stress distribution and structural demands. Endplate morphology adjustments inform the WTO (Weight Topology Optimization) structural design, maintaining tri-mesh integrity for biomechanical realism. The optimal OLIF cage structure, measuring 45 mm × 22 mm with a 12° wedge, was refined to support implant stability and bone integration. The final design includes strategic screw placement at calculated angles (40° and 30°), enhancing fixation, and reducing the risk of implant migration or failure in fragile osteoporotic bone. This simulation-driven, morphology-tailored process ensures patient-specific performance and safety in spinal fusion procedures (Lai et al., 2023).

Figure 24. Design process of the oblique lateral lumbar interbody fusion (OLIF) cage including an FE model based on the endplate morphology obtained from osteoporosis in the elderly and the WTO (Lai et al., 2023) Open Access.

Machine learning (ML) has developed into a disruptive technology in biocompatible material design as it provides new answers to the old problems of the sector. Using the advantages of ML algorithms, scientists can maximize the characteristics of materials, including magnesium alloys, architected materials, and hydrogels, thereby making them more biocompatible and functional in the medical domain. This strategy not only enhances the speed of the design process but also enhances the accuracy and effectiveness of the design materials (Al et al., 2024). It has been used in orthopedic implants, where the materials have a biocompatible elastic modulus and increased strength compared to the conventional design. These materials could also be adjusted to more complex anatomical shapes, which was possible owing to the ML-driven design process and increased load-bearing capacity (Alves et al., 2018).

Figure 25 presents a workflow for generating architected tissue-support materials that mimic the irregular structures of nature and optimize the stress distribution for bone healing. In panel (a), natural materials with complex architectures, which are considered inspirational for bioengineered supports, include wood, seashells, bones, bird feathers, spider silk, and turtle shells. Panel (b) illustrates the optimization in which the microstructural design variables are adjusted to produce a material capable of controlling stress at micro and macro scales to achieve the desired properties. The virtual growth simulator featured in panel (c) is a model used to study the impact of building block combinations on the geometry of the printed scaffolds. Figures (d) and (e) describe the generation protocol, where the personalized support is positioned around a fracture in the femur and the local stress is modulated in a series of steps, correcting the measured stress to the desired values. As demonstrated in panel (f), the completed and stress-compliant material wrapping the femur was finalized, and panel (g) demonstrates the physical result through 3D printing, which produces a customized support that allows the best bone regeneration (Jia et al., 2024).

Figure 25. (a) Natural irregular materials found in wood, seashells, bones, spider silk, turtle shells, and bird feathers. (b) A material property optimizer governs the design variables, microstructures, and material properties (directional elasticity), guiding the evolution of the bulk material at both macro and micro scales to achieve the desired stress distribution. (c) A virtual growth simulator produces diverse disordered microstructures based on the input frequency combinations of basic building blocks. A machine learning model further maps the frequency combinations of the building blocks to their corresponding material properties, which are fed back into the material property optimizer in (c). (d–g) The generation and fabrication of irregular architected materials used for orthopedic femur restoration after a fracture. (d) The generation setup including a fractured femur and a support to be filled with four types of basic building blocks. (e) The initial, optimized, and target stresses in the control region around the fracture, where the initial stress corresponds to a homogeneous distribution of building blocks. (f) The generated support made of optimized irregular materials, which are further composed of disordered microstructures illustrated in the two insets. (g) The 3D-printed samples at varying scales.

An inverse design of molecules with functionality and biocompatibility was developed using a deep learning framework. This approach enabled the generation of molecules with preferred qualities, including increased antibacterial potency and decreased cytotoxicity, indicating that ML can be beneficial for molecular design in biocompatible assays (Antoniadi et al., 2021).

To improve the performance and biocompatibility of biosystems, for example, enzymes and genetic circuits, ML is used in their design. This involves the application of ML to identify trends in biological data and forecast new candidates to enhance biosystem design (Arisoy and Özel, 2015).

Figure 26 illustrates an anatomic approach to bone fixation using a machine-learning (ML)-inspired implant design tested in a rabbit femoral model. Panel (a) shows the rabbit model, with (b) fluoroscopic guidance localizing a 30 mm mid-diaphyseal osteotomy, and (c) the extracted femur and corresponding 5 mm scaffold segment used for mechanical testing. Panel (d) presents the load–displacement curves comparing the ML-inspired, topology-optimized (TO), and uniform scaffold architectures under axial compression. All designs exhibited similar stiffness (∼3,860 N/mm), but the ML-inspired scaffold achieved the highest yield force (1,016.6 N), outperforming TO (856.8 N) and uniform (834.5 N) designs by >20%. The insets show scaffold cross-sections, highlighting the hierarchical irregular porosity of the ML-inspired design. Panel (e) contrasts ML-inspired versus uniform scaffolds, demonstrating an approximately 20% increase in the initial yield strength and a more uniform stress distribution (von Mises stress ∼75% average) in the ML-inspired architecture. These results validate that data-driven biomimetic scaffold geometries can significantly enhance the mechanical performance of patient-specific bone fixation (Peng et al., 2023).

Figure 26. (a, b) A 30 mm bone defect in a New Zealand rabbit’s middle part of the tibia. (c) Micro-computed tomography (Micro-CT) of the tibia. (d) Finite element method (FEM) simulated displacement-force curves of ML-inspired, topology optimization (TO), and uniform designs. (e) Experimental displacement-force curves of the ML-inspired design versus uniform design. The inset shows the cross-sections of von Mises stress under 0.6 mm deformation for both designs.

Although ML has great potential for the development of biocompatible materials, there are still obstacles: better interpretability and compatibility of ML models with complex biological systems are required. In addition, combining ML with conventional design and high-throughput screening strategies is essential to achieve the potential of ML in the field (Arjmandnia and Alimohammadi, 2024). The literature clearly favors the use of ceramic-based surface treatments to not only increase the corrosion resistance, but also the osseointegration of metallic biomaterials. The most proven methods are plasma spraying and sol-gel with HA; bioactive glass coating is the best combination of bioactivity and corrosion protection (Singh et al., 2023). The evidence base for better implant longevity and integration is not weak, and has been supported by a wide range of in vitro and in vivo research, as well as clinical reports. These studies point to the major progress in implant surface modifications, which have been proven to increase the process of osseointegration and, therefore, the life of implants. The modifications are as simple as the alteration of surface topography to biochemical modifications to increase the contact between the implant and biological tissues (Edathazhe, 2018).

Other surface modification methods, such as blasting, acid etching, and anodic oxidation, have also been demonstrated to enhance the biocompatibility of titanium implants and achieve faster rates of osseointegration, resulting in shorter edentulous periods of patient duration (Fang et al., 2019).

Table 4 indicates that ceramic coatings such as hydroxyapatite, bioactive glass, and composite ceramics reinforce metallic implants, which support osseointegration, corrosion resistance, and prevention of infections. Difficulties include adhesion, stability, and complexity of fabrication. Future advances will be based on multi-ion doping, functionally graded layers, additive manufacturing, and hybrid deposition methods to maximize performance.

Table 4. Ceramic coatings such as hydroxyapatite, bioactive glass, and composite ceramics enhance metallic implants.

Surges in the attachment of bioactive molecules, including peptides and bone morphogenetic proteins, to the surface of implants have been reported to improve bone formation and remodeling, and further enhance the ability of implants to integrate into the bone. Ti-Ga alloys have been proven to have better osseointegration than pure titanium because Ga induces the formation of apatite and osteogenic differentiation, which increases the bone-implant interface. Zirconia implants have been researched for their mechanical and esthetic characteristics, and studies have shown that they can be successful over the long term in clinical settings (Li et al., 2023).

Figure 27 illustrates the comprehensive surface engineering approach for biodegradable implants, combining bioactive coatings and mechanical treatment strategies to optimize implant performance. Two major directions of modification culminate in the central implant system: application of bioactive coating (presented in the form of a strata layer) and mechanical surface treatment (presented in the blue processing tool). These surface engineering methods are synergistic with three important performance parameters, which are illustrated by the hexagonal indicators. Surface modification processes enhance the mechanical properties to maximize strength, fatigue, and structural integrity. The integration of tissues is impregnated through bioactive coating, which encourages OSI integration, cellular adhesion, and biocompatibility with the surrounding bone tissue. Protective surface treatments protect against degradation in physiological environments and allow controlled rates of biodegradation to occur, thereby attaining corrosion resistance. This combined surface engineering solution aims to overcome the inherent problems of biodegradable implants by balancing mechanical, biological, and controlled dissolution of the biomatter, resulting in better clinical outcomes and patient safety in temporary fixation cases (Nilawar et al., 2021).

Figure 27. Surface engineering of biodegradable implants (Nilawar et al., 2021) Open Access.

These innovations are still promising, but the long-term stability of antibacterial coatings and their biocompatibility still need to be ensured. The possibility of resistance to antibacterial agents and cost-effective production processes is an urgent factor for massive clinical implementation. In addition, the introduction of these technologies in current medical practice requires research and development to streamline their performance and ensure patient safety to patients (Dias et al., 2024).

Figure 28 summarizes the influence of the mean stress and additive manufacturing build orientation on the fatigue behavior of the miniaturized Ti6Al4V struts. The building orientation panel shows cylindrical specimens printed at angles ranging from 0° (horizontal) to 90° (vertical) relative to the build plate. In the fatigue and buckling sections, slender struts were analyzed using Johnson’s buckling criterion, while fatigue loading was characterized by stress ratio cycles (R = 0.1, 0.4, 1, and 10) to capture the tension–compression asymmetry. The mean stress effect is then incorporated via Haigh diagrams, plotting alternating stress (σa) against mean stress (σm) for each orientation and deriving Walker coefficients, which decrease with increasing build angle owing to the anisotropic microstructure. Finally, a fatigue failure image and CT scans indicated that surface cracks begin at external strut surfaces with orientation-sensitive defect populations, and internal porosity and lack-of-fusion defects encourage subsurface crack nucleation. The current integrative analysis indicates that the mean stress and build orientation play a critical role in the fatigue life of thin-strut titanium structures (Murchio et al., 2024).

Figure 28. Influence of mean stress and building orientation on fatigue properties of sub-unital thin-strut miniaturized Ti6Al4V (Murchio et al., 2024) Open Access.

One promising research direction involves the development of functionally graded, composite, and antibacterial coatings because these types of coatings may improve the performance and longevity of biomedical implants and other engineering applications. Their properties include a combination of new properties, such as enhanced mechanical strength, biocompatibility, and antibacterial activity, which are vital in many applications, including dental and orthopedic implants (Ding et al., 2024).

7 Conclusion

Surface modification of metallic biomaterials by the application of ceramic materials improves the functionality of these materials in orthopedic and dental implants. Such treatments enhance biocompatibility, resistance to corrosion, and incorporation of the patient into the bone, which contributes to improved long-term patient results. Ceramic coating methods can be performed in several ways, such as sol-gel deposition, physical vapor deposition, and plasma spraying. Researchers can manipulate the surface properties to achieve maximum cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation by accurately controlling the composition and microstructure of the ceramic layer. Plasma spraying is economical and creates dense hydroxyapatite layers that enhance osteoconductivity and corrosion resistance. Plasma-sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings have also been found to promote excellent adhesion even on metallic implant surfaces, which improves their stability in the body in the long run. Nevertheless, owing to the heat associated with plasma spraying, phase changes and modifications in the crystallinity of the coating may occur, which may influence its biological functionality.

Sol-gel methods allow homogeneous nanoporous coatings at low temperatures that enhance coating homogeneity and bioactivity. The precursor composition and processing parameters can be modified to produce coatings for biomedical applications. Low-temperature processing also enables the incorporation of temperature-labile biomolecules such as growth factors or antibiotics into the coating matrix. Moreover, sol-gel coatings can be used to release therapeutic agents or allow tissue incorporation over time. Functionally graded coating features a gradual change in composition or porosity to reduce stress concentration and encourage bone ingrowth. Future studies are aimed at establishing higher-performing and longer-lasting implants with functionally graded, composite, and antibacterial coatings. These surfaces are usually characterized by a dense inner surface that gives them strength and corrosion resistance, and a more porous outer surface that resembles the bone form.

Author contributions

AM: Writing – original draft, Software, Formal Analysis. HV: Supervision, Writing – review and editing. JS: Writing – review and editing, Validation, Visualization, Formal Analysis.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmats.2025.1697332/full#supplementary-material

References

A, L., Nayak, S., and Elsen, R. (2024). Artificial intelligence-based 3D printing strategies for bone scaffold fabrication and its application in preclinical and clinical investigations. ACS Biomaterials Sci. and Eng. 10, 677–696. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.3c01368

Abate, K. M., Nazir, A., and Jeng, J.-Y. (2021). Design, optimization, and selective laser melting of vin tiles cellular structure-based hip implant. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 112, 2037–2050. doi:10.1007/s00170-020-06323-5

Abdulghafor, M. A., Mahmood, M. K., Tassery, H., Tardivo, D., Falguiere, A., and Lan, R. (2023). Biomimetic coatings in implant dentistry: a quick update. J. Funct. Biomaterials 15, 15. doi:10.3390/jfb15010015

Abdullah, M., Mubashar, A., and Uddin, E. (2023). Structural optimization of orthopedic hip implant using parametric and non-parametric optimization techniques. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 9, 055026. doi:10.1088/2057-1976/aced0d

Abdulwahab, M., Aigbodion, V., and Enechukwu, M. (2019). Anti-corrosion of isothermally treated Ti-6Al-4V alloy as dental biomedical implant using non-toxic bitter leaf extract. Chem. Data Collect. 24, 100271. doi:10.1016/j.cdc.2019.100271

Abduo, J. (2014). Fit of CAD/CAM implant frameworks: a comprehensive review. J. Oral Implant. 40, 758–766. doi:10.1563/aaid-joi-d-12-00117

Ad, S., Spa, P., Naveen, J., Khan, T., and Khahro, S. H. (2024). Advancement in biomedical implant materials—a mini review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., 12–2024.

Afonso Camargo, S. E., Mohiuddeen, A. S., Fares, C., Partain, J. L., Carey, P. H., Ren, F., et al. (2024). Anti-bacterial properties and biocompatibility of novel SiC coating for dental ceramic. J. Funct. Biomaterials. doi:10.3390/jfb11020033

Afzal, A. (2014). Implantable zirconia bioceramics for bone repair and replacement: a chronological review. Mater. Express 4, 1–12. doi:10.1166/mex.2014.1148

Ajdelsztajn, L., Schoenung, J. M., Jodoin, B., and Kim, G. E. (2005). Cold spray deposition of nanocrystalline aluminum alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 36, 657–666. doi:10.1007/s11661-005-0182-4

Ak, A., and Çiçek, B. (2021). Synthesis and characterization of hydrophobic glass-ceramic thin film derived from colloidal silica, zirconium (IV) propoxide and methyltrimethoxysilane via sol–gel method. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 98, 252–263. doi:10.1007/s10971-021-05482-5

Alkurdi, A. A. H., Al-Mohair, H. K., Rodrigues, P., Alazzawi, M., Sharma, M. K., and Oudah, A. Y. (2024). Enhancing mechanical behavior assessment in porous thermal barrier coatings using a machine learning fine-tuned with genetic algorithm. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 33, 824–838. doi:10.1007/s11666-024-01756-w

Alahnoori, A., Badrossamay, M., and Foroozmehr, E. (2023). Characterization of hydroxyapatite powders and selective laser sintering of its composite with polyamide. Mater. Chem. Phys. 296, 127316. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2023.127316

Almeida, V., Balzaretti, N., Costa, T., Machado, G., and Gallas, M. (2013). Surfactants for CNTs dispersion in zirconia-based ceramic matrix by sol–gel method. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 65, 143–149. doi:10.1007/s10971-012-2918-0

Alqutaibi, A. Y., Alghauli, M. A., Algabri, R. S., Hamadallah, H. H., Aboalrejal, A. N., Zafar, M. S., et al. (2025). Applications, modifications, and manufacturing of polyetheretherketone (PEEK) in dental implantology: a comprehensive critical review. Int. Mater. Rev. 70, 103–136. doi:10.1177/09506608251314251

Alves, T., Das, R., and Morris, T. (2018). Embedding encryption and machine learning intrusion prevention systems on programmable logic controllers. IEEE Embed. Syst. Lett. 10, 99–102. doi:10.1109/les.2018.2823906

Annaji, M., Mita, N., Poudel, I., Boddu, S. H. S., Fasina, O., and Babu, R. J. (2024). Three-dimensional printing of drug-eluting implantable PLGA scaffolds for bone regeneration. Bioengineering 11, 259. doi:10.3390/bioengineering11030259