- 1Department of Macromolecular Science and Engineering, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, United States

- 2Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Pennsylvania State University, College Park, PA, United States

Epoxy vitrimers have attracted significant research attention due to their reprocessability, malleability, and potential self-healing capability. In this study, we successfully synthesized two vitrimers based on a bulky diepoxide monomer, 9,9-bis(4-glycidyloxyphenyl)fluorene (DGBPEF) and zinc catalysts. When DGBPEF reacted with flexible Pripol 1040, a soft vitrimer with a glass transition temperature (Tg) of 45 °C and a topology freezing transition temperature (Tv) of 207 °C was obtained. When DGBPEF reacted with glutaric anhydride, a hard vitrimer with a Tg of 166 °C and a Tv of 235 °C was obtained. While both samples exhibited good reprocessability upon hot-pressing around Tv, their surface scratches could not self-heal autonomously without applying pressure. Surface-functionalized superparamagnetic γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles (∼20 nm) were dispersed into the soft vitrimer matrix to prepare nanocomposites. At a nanoparticle loading of 5 wt%, the application of an oscillating magnetic field induced rapid induction heating, raising the nanocomposite temperature to 240 °C–250 °C (well above the Tv) within 5–10 min, which enabled effective autonomous self-healing of surface scratches. In contrast, no self-healing was observed when the nanocomposite was directly heated in a vacuum oven at 240 °C. This difference is attributed to the possible migration of γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles toward the crack site under an oscillating magnetic field, which enhances localized heating and triggers the autonomous self-healing response.

1 Introduction

Thermosets are chemically crosslinked polymers with a three-dimensional (3D) network, offering excellent mechanical strength, thermal stability, and solvent resistance (Dodiuk and Goodman, 2014; Biron, 2004). Epoxy is the most common class of thermosetting polymers, widely used as a matrix for preparation of composites, coatings, adhesives, and electrical components used in the aerospace, transportation and electronics sectors (Saba et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2024). However, due to their permanent 3D structures, epoxy thermosets cannot be remolded or reprocessed once cured. To address this issue, vitrimers, a class of cross-linked polymers that contain abundant dynamically exchangeable covalent bonds, have been developed (Denissen et al., 2016; Guerre et al., 2020; Van Zee and Nicolaÿ, 2020; Yang et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2021; Lucherelli et al., 2022; Schenk et al., 2022). Under an external stimulus such as heat, the bond-exchange reaction is activated, and the crosslinked polymer displays certain thermoplastic characteristics like reparability and malleability.

In a dissociative covalent adaptable network (CAN), (Hayashi, 2020; Jia et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022), chemical bonds break at a higher rate than they form at higher temperatures to reduce network integrity, e.g., the alkoxyamine radical exchange reaction. After the bonds break more at high temperatures, bond exchanges occur and thus provide recyclability and healability. However, if the temperature is too high (i.e., way above the dissociating temperature), the dissociative CAN behaves like a thermoplastic gel or a supramolecularly crosslinked material, where the viscosity dramatically drops following the Williams-Landel-Ferry (WLF) equation (Hayashi, 2020). Therefore, the shape of the dissociative CAN material could not hold above the bond dissociation temperature. On the other hand, vitrimers utilize an associative CAN (Scheutz et al., 2019; Elling and Dichtel, 2020; Hayashi, 2020; Krishnakumar et al., 2020; Porath et al., 2022). A typical mechanism of epoxy vitrimers is the catalyzed dynamic transesterification reaction. In the presence of a catalyst, the ester bond can associate with the alcohol (R2-OH) in the system at high temperatures, enabling bond exchange without reducing the overall crosslinking density. Upon cooling, the fast transesterification ceases, and the crosslinked network becomes frozen, restoring the original strength of the material. Because the dynamic CAN never dissociates, vitrimers can effectively retain its original shape even above the glass transition temperature (Tg). This is different from thermoplastic and dissociative CAN polymers, which cannot hold their shape above Tg (Krishnakumar et al., 2020). Above the topology freezing transition temperature (Tv), the vitrimer changes from a rubbery elastomer to a vitreous/viscoelastic liquid. Usually, Tv is defined as the temperature at which the melt viscosity is 1012 Pa‧s (Montarnal et al., 2011). The viscosity obeys the Arrhenius equation, rather than the WLF equation. For cases with strong dynamic bonds (e.g., transesterification systems), Tv is usually higher than Tg (Capelot et al., 2012; Krishnakumar et al., 2020). For systems with weak dynamic bonds (e.g., imine- and disulfide-based systems), (Belowich and Stoddart, 2012; Azcune and Odriozola, 2016), Tv can be lower than Tg (Krishnakumar et al., 2020). When the temperature is below Tg, chains are frozen because of zero segmental motion. Immediately above Tg, covalent bond exchange happens, and the viscoelastic polymer follows the WLF equation. However, as temperature further increases, the polymer enters the viscoelastic liquid region, following the Arrhenius equation. Because vitrimers can hold the original shape, they are extremely useful for self-healing.

Typical functionalities have been demonstrated for a low-Tg (−40 °C) transesterification-based epoxy vitrimer (Hayashi et al., 2019; Hayashi, 2020). The Tv is estimated based on the second “softening point” at 140 °C, above which significant stress relaxation is observed. First, reprocessability is achieved by fixing the helical shape of a vitrimer stripe around a steel rod using Kapton tape, followed by thermal annealing in an oven at 160 °C for 2 h. After cooling to room temperature, the helical shape becomes permanent without any relaxation behavior. Second, self-healing is achieved for a vitrimer film with a 0.5-mm deep scratch by thermally annealing at 180 °C. The disappearance of the scratch after thermal annealing indicates that the bond exchange via transesterification is effective in reorganizing the polymer chains and thus healing. Recyclability is also demonstrated for fractured pieces by hot-pressing at 180 °C. After hot-pressing, the pieces merge into a disk-shaped sample. It can be swollen in chloroform uniformly without breaking into pieces. Clearly, the dynamic bond reorganization completely removed the boundary between the hot-pressed pieces. Finally, strong self-adhesion is shown for two overlapping pieces under a weight of 50 g at 160 °C for 2 h. After cooling to room temperature and removal of the weight, these two pieces strongly adhere together. Tensile stretching of the adhered two pieces will not break at the adhered place, but in the middle of one piece. In the control experiment without using Zn(OAc)2 catalyst, no adhesion is observed at all. This result again indicates that new covalent bonding is formed between the two adhered pieces.

In addition to transesterification-based bond exchange, other more labile bond exchange mechanisms have also been reported. The first is the disulfide exchange chemistry. Because of the thiol-disulfide exchange, the disulfide bonds can start dynamic bond exchange without any catalyst. A dual bond exchange vitrimer is synthesized by reacting diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A (DGEBA) with 4,4′dithiodibutyric acid at 180 °C with triazobicylodecene as the transesterification catalyst (Chen et al., 2019). The Tg is around room temperature and the Tv is determined to be −6.3 °C. The lower Tv than Tg is attributed to the labile disulfide bonds.

Another labile bond exchange mechanism is the imine-amine exchange and imine metathesis chemistry in imines or Schiff bases (Belowich and Stoddart, 2012). Imines are unique because both dissociative (hydrolysis) and associative bond exchanges (imine-amine exchange and imine metathesis) can occur in the presence of moisture. Again, the bonds are rather weak, and no catalyst is needed for polyimine vitrimers to exhibit reprocessable, recyclable, and healable properties. In the polyimine vitrimer based on vanillin epoxy and 4,4′-methylenebiscyclohexanamine, (Wang et al., 2019), the Tv is determined to be 70 °C, significantly lower than the Tg of 172 °C. This is again attributed to the labile imine bond exchange chemistry. From the above discussion, it is possible to select or combine different bond exchange chemistries and catalysts to fine-tune both Tg and Tv for subsequent reprocessing and self-healing properties.

Most epoxy vitrimers reported so far show relatively low Tgs (<100 °C), which limit their applicability in fields where high thermomechanical performance at elevated temperatures is required. The epoxy vitrimers are usually prepared with an inequivalent epoxy/anhydride or carboxylic acid stoichiometry to achieve a decent transesterification rate within the crosslinked network, which consequently limits the crosslink density and leads to low Tgs of the cured polymers. In addition, aliphatic dicarboxylic acid or anhydride is also used as the flexible building block in the network structure, which facilitates the molecular segment movement and the dynamic transesterification reaction (DTER) but greatly compromises the Tg of the crosslinked polymers.

A high Tg (up to 187 °C) epoxy vitrimer based on a rigid tri-epoxy and a cycloaliphatic anhydride was developed (Liu et al., 2018). However, because of the highly rigid segments in the network, efficient repairing required a high temperature (220 °C) with an external pressure. More recently, triethanolamine (TEOA) was incorporated as a catalytic co-curing agent to a rigid epoxy (DGEBA) - anhydride (nadic methyl anhydride) network to give a TEOA-mediated covalent adaptable network system (Zhao and Abu-Omar, 2018). An equivalent epoxy/anhydride ratio was used in the compositions. While the three -OHs of TEOA were involved in the curing reactions and ensure the availability of sufficient -OHs for DTER in the crosslinked network, the tertiary amine moiety in TEOA serves as an internal catalyst for both curing of epoxy-anhydride and DTER in the crosslinked network (Hao et al., 2020). The resulting epoxy vitrimer exhibits a decent Tg (∼135 °C), excellent tensile strength (∼94 MPa), and repairability at 190 °C.

In this work, we prepared both low- and high-Tg epoxy vitrimers. Using 9,9-bis(4-glycidyloxyphenyl)fluorene (DGBPEF) epoxy (1.0 eq. epoxide group), zinc acetate (10 mol% of epoxide group), and Pripol 1040 (1.0 eq. carboxyl group), the soft network (i.e., low-Tg) vitrimer was prepared via (1) addition-esterification of acids on epoxy rings, (2) etherification of epoxy groups, and (3) Fischer esterification of acids on hydroxyl groups. Similarly, using DGBPEF, glutaric anhydride (GA), and zinc acetylacetonate [Zn (acac)2], the hard network (i.e., high-Tg) vitrimer was successfully prepared. Different from the acid-based vitrimer reactions, anhydride-epoxide reactions involved anhydride-hydroxyl esterification followed by acid-epoxide ring-opening esterification.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Materials

All chemicals were used as received without further purification. Pripol 1040, a mixture of C18 fatty acid derivatives (23 wt% dimers and 77 wt% trimers), was provided by Cargill Corporation. 9,9-Bis(4-glycidyloxyphenyl)fluorene (DGBPEF) was purchased from TCI America. Zinc acetate dihydrate, zinc acetylacetonate hydrate, and glutaric anhydride were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)-coated and silane-coated γ-type iron oxide nanoparticles (γ-Fe2O3, 99.5+%, 20 nm) were supplied from U.S. Research Nanomaterials, Inc.

2.2 Formulation and curing process of the DGBPEF-based soft epoxy vitrimer

The detailed preparation procedure is illustrated in Figure 1. First, 13.0 g of Pripol 1040 (∼296 g/mol COOH, 43.2 mmol COOH groups) and 0.95 g of zinc acetate dihydrate (4.32 mmol, 10 mol% relative to the COOH groups) were combined in a 100 mL PTFE beaker. The mixture was heated to 180 °C under vigorous stirring and maintained at this temperature for 1 h until gas evolution ceased and the zinc catalyst fully dissolved, yielding a viscous dark-brown liquid (Zn2+@Pripol 1040). The mixture was cooled to 165 °C before adding 10 g of DGBPEF (43.2 mmol epoxide groups) with vigorous hand stirring. A prepolymer formed within 2 min and was transferred into a preheated steel mold (140 °C) sprayed with silicone oil for easy release. The mold was covered with nonstick aluminum foil and cured in a hot press at 180 °C for 3 h. To ensure complete curing, the samples were post-cured in a vacuum oven at 240 °C for 1 h.

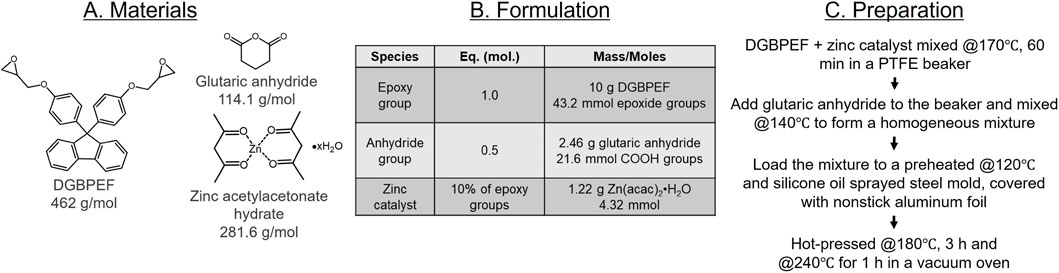

2.3 Formulation and curing process of the DGBPEF-based hard epoxy vitrimer

The detailed preparation procedure of the hard vitrimer is shown in Figure 2. First, 10.0 g of DGBPEF (43.2 mmol epoxide groups) and 1.22 g of zinc acetylacetonate hydrate (4.32 mmol, 10 mol% relative to the epoxide groups) were mixed in a 100 mL PTFE beaker. The mixture was heated to 170 °C under vigorous hand stirring and maintained at this temperature for 1 h until the zinc catalyst dissolved, forming a white cloudy mixture (Zn2+@DGBPEF). The mixture was then cooled to 140 °C before adding 2.46 g of glutaric anhydride (21.6 mmol anhydride groups) to form a homogeneous mixture. This mixture was transferred into a preheated steel mold (120 °C) sprayed with silicone oil for release. The mold was covered with nonstick aluminum foil and cured in a hot press at 180 °C for 3 h. Samples were post-cured in a vacuum oven at 240 °C for 1 h.

2.4 Formulation and curing process of the DGBPEF-based soft epoxy vitrimer/γ-Fe2O3 nanocomposite

Following the procedure for soft epoxy vitrimer preparation, Zn2+@Pripol 1040 was prepared in a 100 mL PTFE flask first. Various amounts of γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles (0.25, 0.5, 1, and 5 wt% of the vitrimer matrix) were dispersed in Zn2+@Pripol 1040 at 150 °C using high-power ultrasonication (300 W in pulsed mode with 5 s on and 5 s off) for 1 h under N2 purge (to avoid oxidation), yielding a black fluid with uniform dispersion of γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles (Supplementary Figure S1). Note that zinc acetate dihydrate only dissolved in Pripol at high temperatures (e.g., 150 °C); therefore, we performed nanoparticle dispersion at 150 °C. This viscous fluid was then mixed with DGBPEF at 165 °C with vigorous hand stirring. The prepolymer was molded and cured following the same process as the soft epoxy vitrimer.

2.5 Characterization and instrumentation

High-power ultrasonication of γ-Fe2O3. nanoparticles in the Zn2+@Priol 1040 mixture was conducted with a Cole-Parmer 750-W ultrasonic processor (Antylia Scientific, Vernon Hills, IL). Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were carried out using a TA Instruments DSC 250. For each run, approximately 3–5 mg of sample was scanned at a rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen gas flow (50 mL/min). Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was carried out on a Nicolet iS50R FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with 2 cm-1 resolution and 32 scans. Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) was performed using a TA Instruments Q800 DMA apparatus in the tension geometry. The heating rate and frequency were 2 °C/min and 1 Hz, respectively. Dilatometry and creep experiments were also performed using the TA-Q800 DMA apparatus in the tension geometry. For non-isothermal creep experiments, sample length was measured under a weak elongational stress (10 kPa) during heating (3 °C/min). For isothermal creep experiments, sample length was recorded under a constant 100 kPa stress at preset temperatures (150, 200, and 240 °C). Isothermal stress relaxation experiments were performed using a TA Instruments RSA-G2 Solid Analyzer at different temperatures. A constant strain of 1% was applied after temperature equilibration. Then, the stress was recorded as a function of time.

2.6 Magnetic induction heating

Magnetic induction heating was performed using a UltraFlex Power Technologies HSB-3 high frequency magnetic heating station. Sample geometry and experimental setup are presented in Supplementary Figure S2. The current, voltage, power, and frequency output to magnetic induction coil were 6 A, 59 Vdc, 0.35 kW, 792 kHz, respectively. Under these output conditions, the complete heating system exhibited a minimum efficiency of 88% with a full-loading operation, indicating that the power input from the mains to the complete heating system was less than 0.4 kW. During the heating process, the sample was placed at the center of the magnetic induction coil, where the maximum magnetic field was about 1.3 mT. The maximum operating time of the heating station is 10 min under these output conditions. The infrared thermal imager (HT-18, Dongguan Xintai Instrument Co., Ltd.) operated at a frame rate of 9 Hz and an accuracy of ±2 K/±2%. The infrared thermal imager was positioned at ∼ 20 cm from the sample to monitor real-time surface temperatures during the magnetic induction heating process. At least six individual samples were tested for each soft vitrimer/γ-Fe2O3 nanocomposites and average values were used to plot the data.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Thermal curing of soft and hard epoxy vitrimers

DSC was used to characterize the curing process of the prepolymer mixtures to prepare the soft and hard epoxy vitrimers. Figure 3A shows the first heating (curing) DSC curve of the prepolymer mixture for the soft epoxy vitrimer. The melting peak of DGBPEF was seen at 159.7 °C, followed by a major curing peak for the acid/epoxide reactions centered at 231 °C. After the first curing process, the soft vitrimer was further studied by the first cooling and second heating DSC scans. From Figures 3A,B Tg was found at 45 °C. Figure 3C shows the first heating (curing) DSC curve for the unreacted mixture of the hard epoxy vitrimer. The first exothermic curing peak for the anhydride/epoxide reaction was observed at 179 °C, followed by a second curing peak for the acid/epoxide reaction around 248 °C. Note that the first exothermic curing peak was so large that the endothermic melting of DGBPEF around 160 °C was overwhelmed and could not be observed. After curing, the first cooling and second heating DSC processes are presented in Figure 3D. The Tg was found at 166 °C. Based on the results from DSC measurements, a curing procedure for the preparation of both epoxy vitrimer systems was established: initial curing at 180 °C for 3 h using a heat press and post-curing at 240 °C for 1 h under vacuum.

Figure 3. Curing DSC curves for (A) prepolymer mixture of the soft vitrimer (partially cured from premixing) and (C) the hard vitrimer mixture. The DSC heating curves of the cured (B) soft and (D) hard vitrimers. The insets in (B) and (D) show the photos of cured soft and hard vitrimers, respectively.

To further validate this curing procedure, the disappearance of epoxide groups and appearance of ester groups after curing was monitored by FTIR. As shown in Figure 4, the characteristic C-O stretching of the oxirane groups at 918 cm-1 largely disappeared after curing at 180 °C for 3 h and 240 °C for 1 h in a vacuum oven. Meanwhile, the ester C=O stretching band appeared at 1735 cm-1 for both samples, which was different from the acid C=O stretching band at 1698 cm-1 for the unreacted mixture of the soft vitrimer. These results confirm the effective consumption of epoxide groups and successful formation of crosslinked epoxy vitrimer networks in both soft and hard systems.

Figure 4. FTIR spectra of DGBPEF/Pripol unreacted mixture for the soft vitrimer, and cured soft and hard epoxy vitrimers.

Tensile mode DMA was carried out for both soft and hard vitrimers with the test frequency set to 1 Hz. At room temperature, the storage modulus of the hard vitrimer (∼6 GPa) was significantly higher than that of the soft vitrimer (∼1.9 GPa) (see Figures 5A,B), due to the incorporation of long, flexible fatty acid chains in the soft vitrimer and short-chain glutaric anhydride in the hard vitrimer. Dynamic Tg, determined from the peak of the dissipation factor (tan δ) at 1 Hz, were 69 °C and 165 °C for the soft and hard vitrimers, respectively. These values were consistent with those determined by DSC (see Figures 3B,D). For the hard vitrimer, a sub-Tg (i.e., β) transition was observed around 55 °C, which is likely due to the localized motion of fluorene moieties within the crosslinked network, as reported before (Zhang et al., 2025).

Figure 5. Tensile DMA curves of storage and loss modulus and dissipation factor (tanδ) for (A) the soft and (B) the hard epoxy vitrimers. The test frequency was 1 Hz.

3.2 Determination of Tv and activation energy using creep experiments

According to previous report (Montarnal et al., 2011), Tv can be determined when the vitrimer viscosity (η) reaches 1012 Pa s. If we assume the shear modulus G = 1 MPa for the vitrimer, the relaxation time τ can be obtained: τ = η/G = 106 s. To determine τ, isothermal stress relaxation experiments were carried out. Figure 6A shows the stress relaxation of the soft vitrimer with a constant strain of 1% at different temperatures. Assuming the Maxwell model, τ could be obtained when the normalized stress decreased to 0.368 (i.e., 1/e). Figure 6B shows the linear fit of τ versus 1/T. By extrapolation to τ = 106 Pa s, the Tv was determined to be 48 °C. Obviously, this result is incorrect because such a low Tv does not fit transesterification-based epoxy vitrimers. A similar conclusion was also reported recently (Hubbard et al., 2021). Instead, the crossover point, where the slope changed, could be used to determine the Tv; see the red lines in Figure 6B. If we use this crossover point, Tv was estimated to be 217 °C for the soft vitrimer.

Figure 6. Determination of Tv for the soft vitrimer using (A) isothermal stress relaxation at different temperatures and (B) extrapolation to τ = 106 s (assuming shear modulus G = 1 MPa) at the hypothetical Tv, where the viscosity is 1012 Pa s. Determination of Tv using nonisothermal creep experiments for (C) the soft and (D) the hard vitrimers. The static force was 0.02 N (∼10 kPa) and the heating rate was 3 °C/min.

In addition to the isothermal stress relaxation method, we also used the non-isothermal creep method to determine the Tv. Compared to the stress relaxation method, the non-isothermal creep method was simpler and faster, provided that the heating rate remained moderate (Montarnal et al., 2011; Capelot et al., 2012; Klingler et al., 2024). As shown in Figures 6C,D, Tg and Tv were determined by the first and second change of the linear thermal expansion in strain, respectively. For the soft and hard vitrimers, Tg values were determined to be 71 °C and 160 °C, and Tv values were determined to be 207 °C and 235 °C, respectively. As we can see, the Tv from the non-isothermal creep experiment was consistent with the Tv from isothermal stress relaxation experiment for the soft vitrimer.

In addition to the nonisothermal creep experiments, isothermal creep experiments were carried out to determine the apparent extensional viscosity (η) of the soft and hard vitrimers, which could be fitted with the Arrhenius equation rather than the WLF equation. Figures 7A–F show the isothermal creep tests under a constant stress (σ) of 105 Pa for the soft and the hard vitrimers, respectively. From the linear region of deformation, the η could be estimated using Newton’s law:

Figure 7. Isothermal creep results of (A–C) the soft and (D–F) the hard vitrimer under a constant tensile stress of 105 Pa at different temperatures. The apparent extensional viscosity (η) was determined by fitting the linear creep region with Newton’s law.

Figure 8. Arrhenius fitting results of ln(η) vs. 1/T for (A) the soft and (B) the hard vitrimers under a constant tensile stress of 105 Pa.

3.3 The non-autonomous healing behavior of the soft and the hard vitrimers

The non-autonomous healing behavior of the soft and hard vitrimers is presented in Figure 9. In the first molding test, the rectangular vitrimer bars were broken in the middle and re-hot-pressed in a steel mold for 1 h (180 °C for the soft vitrimer and 200 °C for the hard vitrimer). As we can see, the broken vitrimer samples successfully healed into a single piece, suggesting the dynamic nature of the two vitrimer networks at temperatures close to the respective Tv. In the second self-healing test, the surfaces of the soft and hard vitrimers were scratched with a razor blade. After heating to 240 °C without any external pressure in a vacuum oven, no self-healing was achieved even after 1 h at temperatures higher than Tv. This observation indicated the high melt viscosity of the dynamic covalent networks in these two vitrimer systems. Note that healing at higher temperatures (>280 °C) for more than 0.5 h would lead to significant charring on the sample surface, so it was not a viable healing condition in air, although a lower viscosity of the dynamic covalent network could be achieved. Instead, after applying a pressure of ca. 15 MPa, the scratches were healed with only 5 min hot-press for the soft vitrimer, yet leading to a thinner sample thickness. Nonetheless, the surface of the hard vitrimer cracked with the same hot-press condition (i.e., without the constraining mold). This was attributed to the much slower relaxation kinetics of the highly crosslinked dynamic covalent network of the hard vitrimer.

Figure 9. Hot-pressing induced healing of broken (A) soft and (B) hard vitrimers at temperatures slightly below the Tv. Self-healing of surface scratches of (C) soft and (D) hard vitrimers using hot-pressing at temperatures above the Tv.

Based on the two tests, it can be concluded that the covalent networks of the two crosslinked vitrimers were intrinsically dynamic and thus re-moldable or malleable at temperature near Tv. However, autonomous self-healing at temperature higher than Tv was not observed, despite its desirability for practical applications. Specifically, appropriate external forces and sample molding were required for the successful healing (or remolding) of the two vitrimers, which would increase the interfacial contact area and facilitate network flow at the damaged site. In contrast, deformation and mechanical failure of samples (especially the hard vitrimer) could happen if too aggressive forces were applied without a mold.

The mechanical properties of the soft vitrimer before and after healing were tested using tensile experiments. As shown in Supplementary Figure S3 and Supplementary Table S1, the mechanical properties decreased, including elongation at break, tensile strength at break, and energy density (or toughness). Therefore, it is desired to improve the mechanical properties after healing by hot compression in the future.

3.4 The autonomous healing behavior of the soft vitrimer@γ-Fe2O3 nanocomposite using magnetic induction heating

We recently reported that the addition of a small amount (<0.1 vol%) of superparamagnetic γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles into a thermoplastic polymer (i.e., polyethylene) enabled the autonomous self-healing of damaged regions at microscale and the restoration of the mechanical and dielectric properties (Yang et al., 2019). Driven by the depletion force, superparamagnetic γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles in the polymer matrix spontaneously migrated to the cracks, which led to aggregation of nanoparticles near the damaged area that induced local high temperature under high-frequency oscillating magnetic field (OMF), enabling the local fusion and healing. It is speculated that the addition of γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles could also be a potential way to induce autonomous self-healing of vitrimers with relatively high Tg. First, it was considered that enough loading of superparamagnetic γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles would be necessary to generate high temperatures (>Tv) inside the sample to activate the dynamic covalent network and enable the migration of γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles to the cracks. Second, the higher concentration of γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles near cracks would generate an even higher local temperature with the OMT treatment, further decreasing the viscosity and facilitating fusion of the local dynamic covalent network for autonomous self-healing. Similar results were also reported recently (Collado et al., 2025a).

Because the hard vitrimer could not even heal after hot-pressing without a constraining mold (see Figure 9D), we did not pursue the autonomous self-healing by induction heating. Instead, the soft vitrimer was employed for this study. The soft vitrimer was used as the polymer matrix for the preparation of nanocomposites by dispersing different amounts of 20 nm PVP- or silane-coated γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles into liquid Pripol 1040 fatty diacids using high-power ultrasonication. Specifically, γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles with a size ∼20 nm showed optimized heating power under the OMF treatment, and the PVP or silane coating stabilized γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles in the soft vitrimer matrix. As presented in Figure 10 and Supplementary Figures S4-S8, 5 wt% loading of PVP- or silane-coated γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles could generate temperatures higher than Tv of the soft vitrimer, which is essential for the migration of nanoparticles within the dynamic covalent network to the crack sites. In particular, soft vitrimer nanocomposites with 5 wt% loading of PVP- or silane-coated γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles could reach as high as 249 °C and 235 °C, respectively, after 5 min induction heating (Figures 10A,B).

Figure 10. Typical IR images of induction-heated soft vitrimers with (A) 5 wt% γ-Fe2O3@PVP and (B) 5 wt% γ-Fe2O3@silane during heating at 10 min. (C) Temperature change of various soft vitrimer/γ-Fe2O3 nanocomposites with different γ-Fe2O3 contents during induction heating.

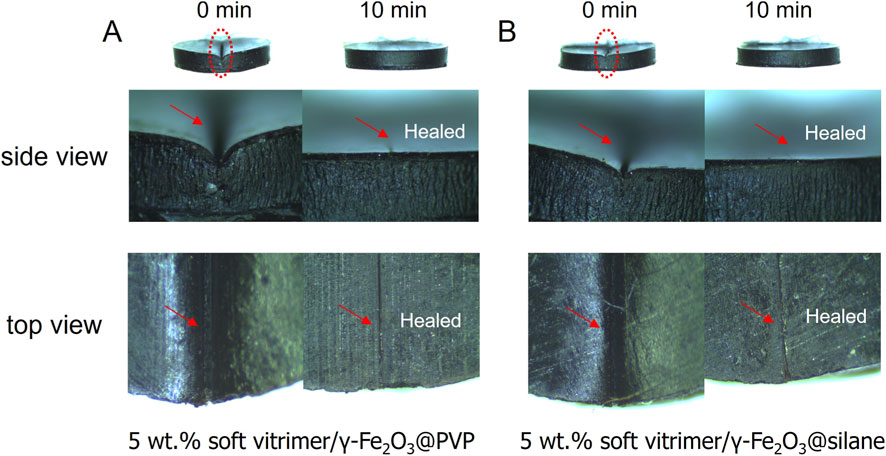

The autonomous self-healing of soft vitirimer/γ-Fe2O3 nanocomposites was further investigated. As presented in Figure 11, after the MOF treatment for 10 min, the surface scratches on both nanocomposites with 5 wt% PVP- or silane-coated γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles could automatically self-heal. The induction heating of the entire sample was monitored by infrared thermal imager during the healing process (Supplementary Figure 2B). The emissivity was calibrated to be 0.6, as shown in (Supplementary Figure S9). The temperatures of both samples stabilized after 2-min induction heating and were higher than the Tv of the soft vitrimer matrix. In contrast, the autonomous self-healing was not observed in neat soft vitrimer (Figure 9C) or 5 wt% soft vitirimer/γ-Fe2O3 nanocomposites by heating at 240 °C in a vacuum oven (Supplementary Figure S10). We infer that the superparamagnetic γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles must have accumulated at the scratched sites upon induction heating, driven by the entropic effect reported before (Yang et al., 2019; Collado et al., 2025a; Collado et al., 2025b). This local aggregation of γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles near the scratches would generate a higher local temperature (>240 °C) with the MOF treatment and significantly decrease the viscosity of the vitrimer matrix near cracks, promoting the autonomous self-healing process.

Figure 11. Autonomous self-healing of (A) the soft vitrimer/5 wt% γ-Fe2O3@PVP and (B) the soft vitrimer/5 wt% γ-Fe2O3@silane nanocomposites with induction heating for 10 min.

4 Conclusion

Utilizing the transesterification dynamic covalent network, both soft and hard epoxy vitrimers were successfully synthesized using a bulky diepoxide monomer (DGBPEF), an acid (Pripol 1040) or an anhydride (glutaric anhydride) monomer, and 10 mol% zinc catalyst, respectively. The soft vitrimer exhibited a Tg and a Tv at 45 °C and 207 °C, respectively. The hard vitrimer exhibited a Tg and a Tv at 166 °C and 235 °C, respectively. From the isothermal creep experiments, the activation energies for the soft and hard vitrimers were determined to be 92.6 and 89.7 kJ/mol, respectively. Although both samples showed reasonable malleability by hot-pressing the broken parts in a mold, self-healing was only achieved for the soft vitrimer by applying pressure on the sample. In contrast, hot-pressing the hard vitrimer above 240 °C resulted in surface cracking, and the self-healing could not be achieved. Therefore, only the soft vitrimer was used for the autonomous self-healing study using induction heating from 20 nm γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles coated with either PVP or silane stabilizing ligands. For the soft vitrimer containing 5 wt% γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles, the average sample temperature reached as high as 220 °C–250 °C after 5 min induction heating, which was higher than the Tv (207 °C) of the soft vitrimer matrix. After 10 min induction heating, both soft vitrimer/γ-Fe2O3@PVP and soft vitrimer/γ-Fe2O3@silane could achieve autonomous self-healing. However, direct heating the soft vitrimer nanocomposites in a vacuum oven would not achieve self-healing autonomously. This result indicates that the γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles could migrate to the crack sites after heating above the Tv, which would induce a higher local temperature at the crack sites and promote autonomous self-healing for the cracks.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

JH: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Data curation. SZ: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review and editing. QW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review and editing. LZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under grant number FA9550-22-1-0281.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmats.2025.1709367/full#supplementary-material

References

Azcune, I., and Odriozola, I. (2016). Aromatic disulfide crosslinks in polymer systems: self-healing, reprocessability, recyclability and more. Eur. Polym. J. 84, 147–160. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2016.09.023

Belowich, M. E., and Stoddart, J. F. (2012). Dynamic imine chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 2003–2024. doi:10.1039/c2cs15305j

Biron, M. (2004). Thermosets and Composites: Technical Information for Plastics Users. New York: Elsevier.

Capelot, M., Unterlass, M. M., Tournilhac, F., and Leibler, L. (2012). Catalytic control of the vitrimer glass transition. ACS Macro Lett. 1, 789–792. doi:10.1021/mz300239f

Chen, M., Zhou, L., Wu, Y., Zhao, X., and Zhang, Y. (2019). Rapid stress relaxation and moderate temperature of malleability enabled by the synergy of disulfide metathesis and carboxylate transesterification in epoxy vitrimers. ACS Macro Lett. 8, 255–260. doi:10.1021/acsmacrolett.9b00015

Collado, I., Vázquez-López, A., Fernández, M., De La Vega, J., Jiménez-Suárez, A., and Prolongo, S. G. (2025a). Nanocomposites of sequential dual curing of thiol-epoxy systems with Fe3O4 nanoparticles for remote/in situ applications: thermomechanical, shape memory, and induction heating properties. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 8, 199. doi:10.1007/s42114-025-01264-7

Collado, I., Vázquez-López, A., Jimenez-Suárez, A., and Prolongo, S. G. (2025b). Multifunctional sequential dual curing electroactive graphene nanocomposites: self-heating, de-icing and in-situ curing. Compos. B Eng. 307, 112911. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2025.112911

Denissen, W., Winne, J. M., and Du Prez, F. E. (2016). Vitrimers: permanent organic networks with glass-like fluidity. Chem. Sci. 7, 30–38. doi:10.1039/c5sc02223a

Elling, B. R., and Dichtel, W. R. (2020). Reprocessable cross-linked polymer networks: are associative exchange mechanisms desirable? ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 1488–1496. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.0c00567

Fortman, D. J., Brutman, J. P., Cramer, C. J., Hillmyer, M. A., and Dichtel, W. R. (2015). Mechanically activated, catalyst-free polyhydroxyurethane vitrimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 14019–14022. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b08084

Guerre, M., Taplan, C., Winne, J. M., and Du Prez, F. E. (2020). Vitrimers: directing chemical reactivity to control material properties. Chem. Sci. 11, 4855–4870. doi:10.1039/d0sc01069c

Hao, C., Liu, T., Zhang, S., Liu, W., Shan, Y., and Zhang, J. (2020). Triethanolamine-mediated covalent adaptable epoxy network: excellent mechanical properties, fast repairing, and easy recycling. Macromolecules 53, 3110–3118. doi:10.1021/acs.macromol.9b02243

Hayashi, M. (2020). Implantation of recyclability and healability into cross-linked commercial polymers by applying the vitrimer concept. Polymers 12, 1322. doi:10.3390/polym12061322

Hayashi, M., Yano, R., and Takasu, A. (2019). Synthesis of amorphous low Tg polyesters with multiple COOH side groups and their utilization for elastomeric vitrimers based on post-polymerization cross-linking. Polym. Chem. 10, 2047–2056. doi:10.1039/c9py00293f

Hubbard, A. M., Ren, Y. X., Konkolewicz, D., Sarvestani, A., Picu, C. R., Kedziora, G. S., et al. (2021). Vitrimer transition temperature identification: coupling various thermomechanical methodologies. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 3, 1756–1766. doi:10.1021/acsapm.0c01290

Jia, Y., Delaittre, G., and Tsotsalas, M. (2022). Covalent adaptable networks based on dynamic alkoxyamine bonds. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 307, 2200178. doi:10.1002/mame.202200178

Klingler, A., Reisinger, D., Schlögl, S., Wetzel, B., Breuer, U., and Krüger, J. K. (2024). Vitrimer transition phenomena from the perspective of thermal volume expansion and shape (in)stability. Macromolecules 57, 4246–4253. doi:10.1021/acs.macromol.4c00207

Krishnakumar, B., Sanka, R. V. S. P., Binder, W. H., Parthasarthy, V., Rana, S., and Karak, N. (2020). Vitrimers: associative dynamic covalent adaptive networks in thermoset polymers. Chem. Eng. J. 385, 123820. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2019.123820

Liu, T., Hao, C., Zhang, S., Yang, X., Wang, L., Han, J., et al. (2018). A self-healable high glass transition temperature bioepoxy material based on vitrimer chemistry. Macromolecules 51, 5577–5585. doi:10.1021/acs.macromol.8b01010

Lucherelli, M. A., Duval, A., and Avérous, L. (2022). Biobased vitrimers: towards sustainable and adaptable performing polymer materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 127, 101515. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2022.101515

Montarnal, D., Capelot, M., Tournilhac, F., and Leibler, L. (2011). Silica-like malleable materials from permanent organic networks. Science 334, 965–968. doi:10.1126/science.1212648

Porath, L., Soman, B., Jing, B. B., and Evans, C. M. (2022). Vitrimers: using dynamic associative bonds to control viscoelasticity, assembly, and functionality in polymer networks. ACS Macro Lett. 11, 475–483. doi:10.1021/acsmacrolett.2c00038

Saba, N., Jawaid, M., Alothman, O. Y., Paridah, M. T., and Hassan, A. (2016). Recent advances in epoxy resin, natural fiber-reinforced epoxy composites and their applications. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 35, 447–470. doi:10.1177/0731684415618459

Schenk, V., Labastie, K., Destarac, M., Olivier, P., and Guerre, M. (2022). Vitrimer composites: current status and future challenges. Mater. Adv. 3, 8012–8029. doi:10.1039/d2ma00654e

Scheutz, G. M., Lessard, J. J., Sims, M. B., and Sumerlin, B. S. (2019). Adaptable crosslinks in polymeric materials: resolving the intersection of thermoplastics and thermosets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 16181–16196. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b07922

Spiesschaert, Y., Taplan, C., Stricker, L., Guerre, M., Winne, J. M., and Du Prez, F. E. (2020). Influence of the polymer matrix on the viscoelastic behaviour of vitrimers. Polym. Chem. 11, 5377–5385. doi:10.1039/d0py00114g

Van Zee, N. J., and Nicolaÿ, R. (2020). Vitrimers: permanently crosslinked polymers with dynamic network topology. Prog. Polym. Sci. 104, 101233. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2020.101233

Wang, S., Ma, S., Li, Q., Xu, X., Wang, B., Yuan, W., et al. (2019). Facile in situ preparation of high-performance epoxy vitrimer from renewable resources and its application in nondestructive recyclable carbon fiber composite. Green Chem. 21, 1484–1497. doi:10.1039/c8gc03477j

Wu, W., Feng, H., Xie, L., Zhang, A., Liu, F., Liu, Z., et al. (2024). Reprocessable and ultratough epoxy thermosetting plastic. Nat. Sustain. 7, 804–811. doi:10.1038/s41893-024-01331-9

Yang, Y., He, J., Li, Q., Gao, L., Hu, J., Zeng, R., et al. (2019). Self-healing of electrical damage in polymers using superparamagnetic nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 151–155. doi:10.1038/s41565-018-0327-4

Yang, Y., Xu, Y., Ji, Y., and Wei, Y. (2021). Functional epoxy vitrimers and composites. Prog. Mate. Sci. 120, 100710. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2020.100710

Zhang, V., Kang, B., Accardo, J., and Kalow, J. (2022). Structure-reactivity-property relationships in covalent adaptable networks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 22358–22377. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c08104

Zhang, W., Lv, S., Chen, Q., Yin, J., Yue, D., Feng, Y., et al. (2025). Improvement of high-temperature energy storage performance of PC/FPE all-organic composite dielectrics based on functional multilayer structure design. J. Energy Storage 124, 116934. doi:10.1016/j.est.2025.116934

Zhao, S., and Abu-Omar, M. M. (2018). Recyclable and malleable epoxy thermoset bearing aromatic imine bonds. Macromolecules 51, 9816–9824. doi:10.1021/acs.macromol.8b01976

Keywords: high temperature epoxy vitrimers, self-healing, topology freezing transition temperature, induction heating, nanocomposites

Citation: Huang J, Zhang S, Wang Q and Zhu L (2025) Synthesis and induction heating-induced self-healing of epoxy vitrimer nanocomposites. Front. Mater. 12:1709367. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2025.1709367

Received: 20 September 2025; Accepted: 12 November 2025;

Published: 03 December 2025.

Edited by:

Mazeyar Parvinzadeh Gashti, Pittsburg State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Ignacio Collado, Rey Juan Carlos University, SpainAntonio Pavone, Politecnico di Bari, Italy

Omar Amin, Ain Shams University, Egypt

Copyright © 2025 Huang, Zhang, Wang and Zhu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lei Zhu, bHh6MTIxQGNhc2UuZWR1; Qing Wang, cXV3MTBAcHN1LmVkdQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Jiahao Huang1†

Jiahao Huang1† Shixian Zhang

Shixian Zhang Lei Zhu

Lei Zhu