- 1Indofil Industry Ltd., Thane, Maharashtra, India

- 2ICAR-Central Agroforestry Research Institute, Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh, India

- 3Department of Botany, Kalimpong College, Kalimpong, West Bengal, India

- 4Department of Biotechnology, Bundelkhand University, Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh, India

- 5Department of Horticulture, Bundelkhand University, Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh, India

- 6Department of Fruit Science, Rani Lakshmi Bai Central Agricultural University, Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh, India

- 7Dr Yashwant Singh Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry, Nauni, Himachal Pradesh, India

Introduction: Plant gums are recognized for their notable nutraceutical and medicinal properties. Numerous studies have explored the medicinal potential of Aegle marmelos, particularly leaves, fruits, and seeds. Its hardy nature, drought tolerance, and diverse applications make it a promising climate-smart crop for agroforestry systems.

Methods: The present study was therefore designed to address this limitation by conducting an in-depth phytochemical and nutraceutical profiling of bael gum and evaluating different parameters, i.e., macroscopic parameters, physical parameters, antioxidant enzyme activities, total phenol content, antioxidant analysis (DPPH assay, metal chelating activity, and ABTS assay). Ultra-high Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-QTOF-MS) was used to identify a diverse range of bioactive compounds with potential health benefits.

Results: This study presents a detailed nutritional and phytochemical characterization of bael gum, revealing high levels of total polysaccharides (40.94%), total protein (16.2%), total nitrogen (2.59%), and total amino acids (16.14%). The antioxidant assays demonstrated significant activity with IC₅₀ values of 765.7 ± 1.5 mg/g for metal chelation, 488 ± 1 mg/g for DPPH, and 368.7 ± 0.9 mg/g for ABTS, alongside of total phenol content of 90 ± 1 μg/g FWT.

Conclusion: These findings revealed that bael gum is a valuable source of bioactive compounds with promising therapeutic potential and its applicability across multiple industries, including food and beverage, pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and personal care, as well as biodegradable films and edible packaging materials. Furthermore, investigating the mechanisms of action of individual bioactive constituents and evaluating their effectiveness in functional food and therapeutic formulations will be essential to enhance the practical utilization of bael gum.

1 Introduction

Bael (Aegle marmelos L.) is a highly valued tree species among the 0.25 million plant species available on Earth. In different languages, the bael tree has various names, i.e., Bel (Assamese, Bengali & Urdu), Bel, Maredu (Marathi), Bel (Hindi), Heirikhagok (Manipuri), Vilvam (Malayalam), Sandiliyamu (Telugu), Bilvapatre (Kannada), Bello (Konkani), Bili, Bilipatr (Gujarati), Bel-thei (Mizo), Bengal quince, Beli fruit, golden apple, and stone apple (English), Adhararuha, Tripatra, Bilva/Shivaphala, Sivadrumah (Sanskrit), Belo (Oriya), and Vilva Marum (Tamil).1 The diversity of names reflects its wide distribution and cultural significance across different parts of India (1, 2). Additionally, in areas where Hindus reside, it is revered by worshippers and frequently planted next to temples devoted to Lord Shiva (3). Since ancient times, bael has been highly valued and widely used in Ayurvedic medicine, both in India and across the South Asian region (4).

The bael tree is believed to have originated in Central India and the Eastern Ghats and is considered native to Southeast Asia. It thrives in tropical to subtropical climates and is commonly found growing wild up to 500 meters above mean sea level (m asl) in the lower Himalayan hills. Naturally occurring populations of bael are found in the Himalayan foothills, particularly in Uttarakhand and the lower districts of Himachal Pradesh, as well as in Central India (Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh), the Deccan Plateau, and along the eastern coastal regions of India. The bael tree is deciduous in nature. Its fruits are spherical with a hard, woody shell (grey or yellowish) and contain soft, yellow to orange, mucilaginous pulp (5).

Bael fruit offers a wide range of health benefits due to its rich content of minerals, fatty acids, amino acids, carbohydrates, vitamins, dietary fibers, and phytochemicals (6). Moreover, it is traditionally used in diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, inflammatory conditions, and digestive ailments. Scientific studies have demonstrated the fruit’s protective properties against radiation, microbial infections, oxidative stress caused by free radicals, wounds, and even symptoms of depression. These findings highlight the significant natural healing potential of bael. In Ayurveda and other traditional systems of medicine, every part of the bael tree —root, bark, leaves, flowers, and fruit —is valued for its therapeutic properties in treating various diseases. Numerous studies have been conducted on various parts of the bael plant, revealing a wide spectrum of ethnopharmacological activities. These include antimicrobial, anti-diarrheal, anti-diabetic, anti-hyperlipidemic, antifungal, antibacterial, anti-ulcer, anticancer, cardioprotective, antipyretic, anti-inflammatory, radioprotective, hepatoprotective, anti-spermatogenic, wound healing, anticonvulsant, immunomodulatory, antidepressant, anti-genotoxic, anti-proliferative, antimalarial, anti-microfilarial, anti-arthritic, nephroprotective, anti-thyroid, insecticidal, and anti-ocular hypertensive effects (2, 7, 8).

Plant gums are secreted from various parts of the plant, including stems, branches, twigs, leaves, and bark, and can also originate from the seed epidermis (9). Gums produced from plants are extremely valuable items that are valued for their medical applications, bioavailability, and nutritional qualities. Gums derived from plants have been utilized for a wide range of purposes throughout history. In modern times, they are extensively applied in the food industry for diverse functions, including as microencapsulating agents for flavor and color, prebiotics, thickeners, beverage stabilizers, coatings, emulsifiers, fat replacers, clarifying agents, edible packaging materials, and in the formulation of emulsions (10). Plant-derived gums have long served a variety of purposes and are increasingly recognized as valuable resources in pharmaceutical applications. Their biocompatibility, nutritional richness, edibility, cost-effectiveness, and therapeutic potential make them highly suitable for modern drug formulations. These natural polymers improve patient compliance, reduce adverse effects, and are well-tolerated by the skin and eyes without triggering allergic reactions. Their low production cost further contributes to their growing utility in the pharmaceutical sector (11). In traditional systems of medicine, bael gum has been employed for a range of therapeutic purposes (12). It is primarily utilized as a gelling agent, adhesive, waterproofing compound, and a controlled drug release carrier (13) and has antimicrobial and anticoagulant properties (14).

The ethnopharmacological significance of plant gums has long been recognized, yet their comprehensive investigation remains limited. Although numerous studies have explored the medicinal potential of Aegle marmelos, particularly leaves, fruits, and seeds, there is a notable lack of detailed information regarding the nutraceutical and phytochemical attributes of bael gum. These gaps in knowledge restrict the understanding of the full therapeutic potential of the plant. The present study was therefore designed to address this limitation by conducting an in-depth phytochemical and nutraceutical profiling of bael gum. A key objective was to identify and characterize its bioactive constituents and to explore potential correlation with bioactive constituents previously reported in other plant parts, thereby contributing to a more holistic understanding of its pharmacological value.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sampling of bael gum

Bael gum was harvested from the bael plants in Babina block, Jhansi district, Uttar Pradesh. The naturally exuded gum was manually harvested from twigs, branches, and stems. It was initially subjected to physical cleaning to remove adhering bark and extraneous matter. To attain the required brittleness, the collected gum was first air-dried for 120 h and then dried again in a hot air oven set at 50 °C. Once dried, the gum was ground using a high-speed electric blender (Bajaj, India) and sieved through a 100-mesh screen to obtain a uniform powder. To prepare the gum extract, the powdered gum was mixed with distilled water in a 1:10 (w/v) ratio. The mixture was stirred continuously at room temperature for 24 h using a rotary shaker to facilitate gum solubilization. The resulting solution was filtered through muslin cloth to separate the supernatant. The residual material retained on the cloth was thoroughly rinsed with distilled water, and the washings were combined with the original filtrate to ensure complete recovery. This extraction procedure was repeated three times to maximize yield (15).

2.2 Separation and purification process

Bael gum was isolated from the previously obtained supernatant by precipitation using acetone at a 2:1 (v/v) ratio. The precipitated gum was separated via centrifugation and subsequently dried in a hot air oven at 50 °C. The dried material was then finely ground and passed through a 100-mesh sieve to ensure uniform particle size. The purified gum was stored in desiccators before further analysis. The isolated sample was then lyophilized and stored for further examination at −20 °C (Figure 1).

Figure 1. (A) Collection of bael gum from the experimental field of bael orchard. (B) Flow chart for sample preparation of bael gum.

2.3 Macroscopic parameters

Various macroscopic features like color, flavor, shape, surface appearance, texture, and fractures were systematically examined. These attributes were categorized using predefined classification schemes based on odour, taste, and texture. The mechanical properties of the gum, including viscosity, adhesiveness, elasticity, hardness, and geometric attributes, were evaluated through various analytical techniques. Taste was assessed using a five-point hedonic scale (1: sweet, 2: sour, 3: salty, 4: bitter, and 5: umami), while odor intensity was measured on a seven-point scale: no odor, very weak, weak, distinct, strong, very strong, and intolerable (16–18).

2.4 Physical parameters

The physical properties of bael gum analyzed in this study included nitrogen content, amino acid composition, polysaccharide concentration, protein levels, electrical conductivity, pH, and viscosity. Viscosity measurements were performed at 30 °C using rotational speeds of 50 rpm and 100 rpm, expressed in mPa·s. Moisture content was determined using a Contech moisture meter, while pH was recorded with a calibrated pH meter. Electrical conductivity was measured with an EC meter and expressed in Siemens per meter (S/m). Viscosity was further assessed using an Ostwald viscometer. Total polysaccharide (phenol sulfuric acid method) (19, 20), total protein (21) total N (22), and the amino acid % (23) were estimated by standard protocols.

2.5 Antioxidant enzyme activities

Using modified protocols, different antioxidant enzymes in bael gum were quantified, including polyphenol oxidase (PPO) (24), catalase (25), ascorbate peroxidase (26), NADPH oxidase (27) superoxide dismutase (28), GST (29) and glutathione reductase (30). The extinction values (ε) utilized for enzymes such as catalase, guaiacol peroxidase, glutathione reductase, and ascorbate peroxidase were 2.8, 26.6, 6.22, and 2.8 mM−1 cm−1, respectively. The UV–VIS spectrophotometer absorbance readings were 240, 470, 560, 340, and 290 nm for catalase, guaiacol peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, glutathione reductase, and ascorbate peroxidase, respectively.

2.6 Antioxidant analysis

The antioxidant analysis, such as total phenol content (TPC) (31, 32), DPPH assay, metal chelating activity (31, 33), and ABTS assay (31, 32) were performed as per the standard protocols. Absorbance readings were measured at 517, 734, 562, and 290 nm for DPPH, ABTS+, Metal chelating, and TPC, respectively, using a UV–VIS spectrophotometer. Detailed methodologies for each antioxidant assay are provided below.

The details of different antioxidant analyses is mentioned below.

2.6.1 Total phenolic content (TPC)

The total phenolic content of bael extract was measured according to the standard protocol (31, 32). 1 mL of the extract was reacted with a mixture containing 1 mL of 95% ethanol solution, 5 mL of distilled water, and 500 μL of Folin-Ciocalteau reagent (50%). After an incubation period of 5 min, 1 mL of 5% Na2 CO3 was added. It was mixed thoroughly on a vortex shaker and further kept for 1 h of incubation at room temperature. Finally, the absorbance of the coloured reaction mixture was recorded at 765 nm against the reagent blank.

2.6.2 1,1-diphenyl-2 picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) based free radical scavenging activity

The radical scavenging activity of the bael extract was measured by DPPH method (31, 33). The reaction mixture contained 1.8 mL of 0.1 mM DPPH and 0.2 mL of bael extract. The reaction mixture was vortexed and left in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm. A reaction mixture without test sample was considered as control. Radical scavenging activity was expressed as percent inhibition from the given formula:

Percentage inhibition of DPPH radical = [(A0 – A1)/A0] x 100.

Where, A0: absorbance of the control and A1: absorbance of the extract.

2.6.3 Metal chelating activity

The chelating activity of the extracts for ferrous ions Fe2+ was measured according to the method (31, 33). 0.4 mL of extract was mixed with 0.04 mL of FeCl2 (2 mM) solution. After 30s, 0.8 mL ferrozine (5 mM) solution was added. After 10 min at room temperature, the absorbance of the Fe2+–Ferrozine complex was measured at 562 nm. The chelating activity of the extract for Fe2+ was calculated as

Chelating rate (%) = (A0 - A1)/A0 × 100

Where A0 was the absorbance of the control (blank, without extract) and A1 was the absorbance in the presence of the extract.

2.6.4 2,2-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS+) radical cation(s) decolorization assay

The spectrophotometric analysis of ABTS+ radical cation(s) scavenging activity was measured according to Jha et al. (31) and Re et al. (32). This method is based on the ability of antioxidants to quench the ABTS+ radical cation, a blue/green chromophore with characteristic absorption at 734 nm. The ABTS+ was obtained by reacting 7 mM ABTS+ radical cation(s) in H2O with 2.45 mM potassium persulfate (K2S2O8), stored in the dark at room temperature for 6 h. Before usage, the ABTS+ solution was diluted to get an absorbance of 0.750 ± 0.025 at 734 nm with sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4). Then, 2 mL of ABTS+ solution was added to 1 mL of the bael extract. After 30 min, the percentage inhibition at 734 nm was calculated for each concentration, relative to a blank absorbance. Solvent blanks were run in each assay. The inhibition of the ABTS radical (%) was calculated using a similar equation to that for the DPPH method.

2.7 Antidiabetic assay

The α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitory properties of bael gum were assessed to evaluate its antidiabetic properties, as per standard procedures (34, 35).

2.7.1 In vitro α-glucosidase inhibitory activity

The α-glucosidase inhibitory property of the sample extract was assayed as described by Sudha et al. (36). The different concentrations of extract were prepared by adding 0.2 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.8). After that, 0.1 mL of enzyme solution was added and kept for incubation at 37 °C. Then, 0.25 mL pNPG (p-Nitrophenyl-glucopyranoside) (3 mM) was added, and the reaction was terminated by adding 4 mL of Na2 CO3 (0.1 M). The α-Glucosidase inhibition activity was estimated by determining the kinetics of release of pNPG (p-Nitrophenyl-glucopyranoside) at 405 nm. The control contained all the reagents without the sample extract. The α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was estimated by following equation:

Inhibitory ratio % = [1- (As- Ab)/ Ac] × 10where As, Ab and Ac represent the OD value of the sample, blank, and control reaction mixture, respectively.

2.7.2 In vitro α-amylase inhibitory activity

The α-amylase inhibition potential of the extract was estimated by standard spectrophotometric method (37). Briefly, 0.5 mL of bael extract was mixed with 0.5 mL of α-amylase solution and incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. After the initial incubation, 0.5 mL of 1% starch solution was added to the reaction mixture and incubated further for 10 min. To terminate the enzymatic reaction, 1 mL of dinitrosalicylic acid (DNSA) reagent was added, followed by heating the mixture in a boiling water bath for 10 min until the solution developed an orange-red color, indicating the presence of reducing sugars. The reaction mixture was then cooled to room temperature and diluted to a final volume of 5 mL with distilled water. The optical density (OD) was recorded at 540 nm using a spectrophotometer. The α-amylase inhibitory activity was quantified by calculating the concentration of the sample extract required to inhibit 50% of the enzyme activity (IC₅₀).

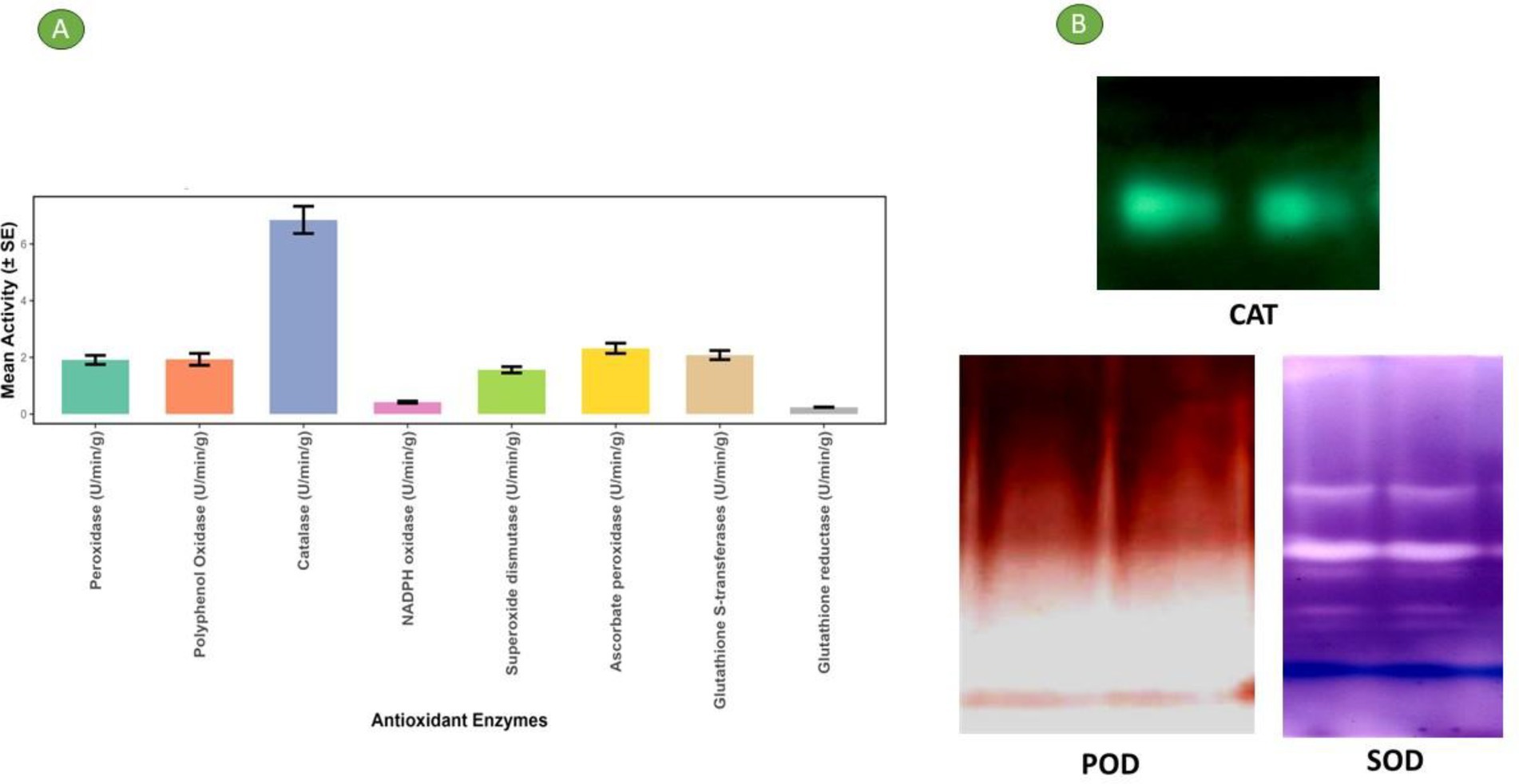

2.8 UHPLC-QTOF-MS analysis of bael gum

Bael gum was further analyzed using the UHPLC-QTOF-MS technique as per the procedure described by Haron et al. (38). Metabolite profiling was carried out using G6550A Ion Mobility Q-TOF LC/MS (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) on the Agilent 6,500 Series Q-TOF LC/MS System (version B.05.01, B5125.3), which combines quadrupole and TOF analyzers for high-resolution and accurate mass detection. Analyte separation was achieved using a Hypersil Gold column (100 × 2.1 mm, 3 μm, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Mumbai, India). The gradient elution method consisted of mobile phases water (0.1% formic acid) as phase A and acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid) as phase B. The steep gradient elution for the analysis of bael gum was carried out with the following procedure: 0–1.0 min at 5 percent of B, 1.1–20.0 min at 100 percent of B, 20.1–25.0 min at 100 percent of B, 25.1–26.0 min at 5 percent of B, and 26.1–30.0 min at 5 percent of B. The column was kept at 40 °C, the injected sample volume was set at 5.0 μL, and the elution flow rate was set at 0.3 mL/min (17). Thermo Scientific’s Xcalibur (version 4.2.28.14) and Agilent MassHunter Workstation Software (version B.05.01) were used in conjunction with Compound Discoverer 3.2 SPI software to acquire and process the data. Minor modifications were applied to optimize the method for natural product analysis. After each cycle, the column was flushed for 2 min to prepare for the subsequent injection. The highest flow rate for ramp-up and ramp-down was set at 100.0 mL/min2, with pressure ranging from 0 to 1,200 bar. Agilent MassHunter Workstation Software (version B.05.01, B5125.3) was used to process and analyze the collected data on some bael gum parameters. Agilent Mass Hunter Workstation Software-Data Acquisition for 6550A Series Q-TOF, version B.05.01 (B5125.3), was used for data processing and analysis. The default parameters were slightly modified to better support the analysis of natural products.

Library matching, elemental composition determination, feature recognition, background subtraction utilizing blank data, retention time alignment, and fragmentation search (FISh) score were all part of the procedure. Chemical constituents in bael gum were identified primarily through comparison of MS/MS data with the mzCloud database. For unmatched signals with a FISh score above 40, identification was reattempted using the ChemSpider database based on MS data.

2.9 Statistical analysis

The present study profiled bael gum using samples collected through random sampling, which provided an overall understanding of its biochemical and nutraceutical attributes. XLSTAT software and Microsoft Excel were used to analyze all of the data using ANOVA analysis. The mean value of three replications is used to characterize the results.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Macroscopic parameters

Table 1 presents an analysis of the morphological traits of bael gum. It exhibits a pale golden to yellowish hue, which is visually appealing. The gum has a firm texture, a salty taste, and is odorless. It also possesses a viscous and thick consistency. Gum particles are crystalline in form and structure, and they are categorized as gritty, grainy, and coarse. These morphological traits are a strong indicator of the gum’s quality and contribute to its potential marketability and versatility in various industries, particularly in the pharmaceutical sector. Similar high-quality appearances have also been reported in other gums, such as gum Arabic (39), Chironji gum (17), almond gum (40) and olibanum gum (34).

3.2 Physical attributes

Table 2 summarizes the physical characteristics of bael gum. The gum exhibits a moisture content of 8.9% and an average pH of 6.55 in a 1% aqueous solution. It is rich in total polysaccharide (40.94%), total protein (16.2%), total nitrogen (2.59%), and total amino acid (16.1%). Bael gum also demonstrates a conductivity of 860 S/m and shows good solubility (89.0%) in warm water. Viscosity measurements indicate that a 1% solution of bael gum has a viscosity of 605 mPa·s at 30 °C and 50 rpm, which decreases to 345 mPa·s at 100 rpm, suggesting shear-thinning behavior.

These properties are comparable to those observed in gums derived from other plant sources such as gum acacia (Acacia senegal), axlewood (Anogeissus latifolia), thorny acacia/babul (Acacia nilotica), and Indian tragacanth (Sterculia urens Roxb) (35). According to Zhou et al. (41)protein plays a vital role in maintaining human health, and the protein content of the bael gum was 16.2%. Other plant gums, such as khaya gum, chironji gum, and honey locust gum, have also been reported to contain appreciable amounts of protein (10, 17). These findings highlight the potential of bael gum as a valuable dietary component.

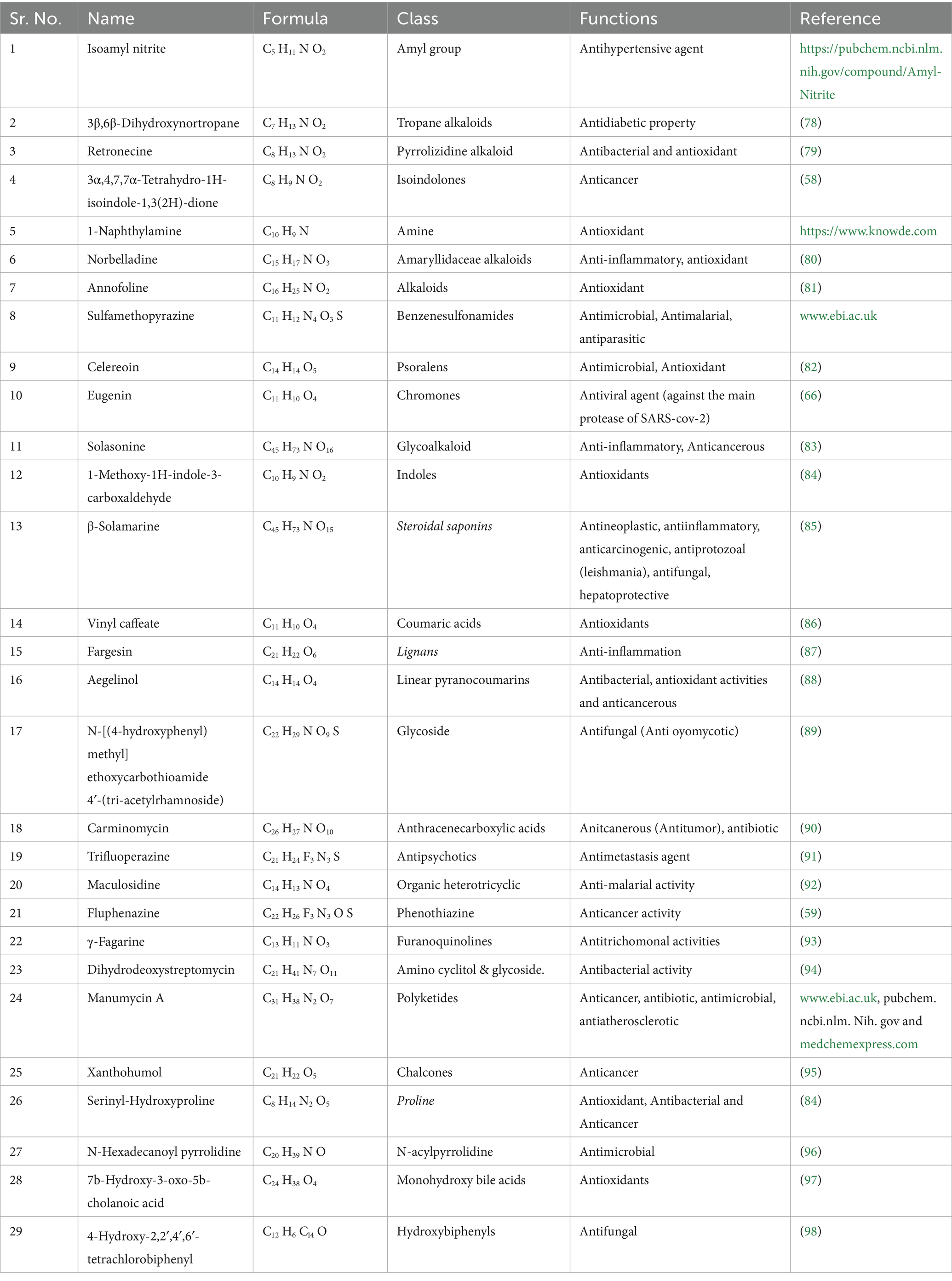

3.3 Antioxidant enzyme activities

Antioxidant enzymes in plants are crucial for defending plant cells from oxidative injury caused by exposure to environmental stressors like UV radiation, pollution, pathogens, and adverse weather conditions. In addition to their protective functions, these enzymes are also involved in regulating key physiological processes, including plant growth and development, responses to both biotic and abiotic stress. Maintaining a balanced antioxidant enzyme system is essential for plant health and resilience (42). Table 2 and Figure 2 present the various antioxidant enzyme activities of bael gum. Superoxide dismutase (SOD), which mitigates the harmful effects of superoxide radicals by catalyzing their conversion into molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, was found to have an activity of 0.76 U/min/g (43). Catalase decomposes H2O2 (hydrogen peroxide) into water and oxygen, preventing oxidative injury to cellular structures (44), and its activity was recorded as 6.85 U/min/g. Peroxidases, such as glutathione peroxidase (GPX) and ascorbate peroxidase (APX), utilize reducing agents like ascorbate and glutathione to detoxify hydrogen peroxide and organic hydroperoxides (45). The peroxidase (POD) activity in bael gum was recorded at 1.91 U/min/g. Glutathione reductase (GR), which regenerates reduced glutathione—a key antioxidant—by converting its oxidized form back to its active state, showed an activity of 0.24 U/min/g (46). Similarly, Chironji gum has been reported to contain significant levels of antioxidant enzymes, including CAT, GPX, SOD, GR, and APX, further supporting the biochemical relevance of plant-derived gums in oxidative stress management (17).

Figure 2. (A) Antioxidant enzyme activity through different methods in the bael gum. (B) Gel picture of different antioxidant enzyme content in bael gum.

3.4 Antioxidant analysis

The antioxidant activity of plant extracts is being assessed to estimate their medicinal value, because antioxidants play a vital role in scavenging free radicals and preventing diseases associated with oxidative stress (47). Therefore, DPPH, ABTS, and metal chelation assays were used in the current investigation to assess the bael gum’s antioxidant activity. The DPPH assay is a widely used, reliable, and sensitive method for evaluating the antioxidant activity of plant extracts. It is valued for its simplicity and rapid execution, although its effectiveness may vary depending on the plant source and extraction procedure (48). The assay measures the ability of antioxidants to scavenge DPPH free radicals, which is observed spectrophotometrically at 517 nm. The antioxidant strength was commonly expressed as IC50. In the present study, bael gum extract exhibited notable antioxidant activity, with IC₅₀ values of 488.3 ± 1 mg/g for the DPPH assay and 368.7 ± 1 mg/g for the ABTS assay, indicating that the extract was more effective in scavenging ABTS free radicals compared to DPPH (Table 3).

Another crucial antioxidant mechanism is the ability of certain compounds to chelate transition metal ions such as copper and iron. By sequestering these metals, chelators inhibit their participation in reactions like the Fenton and Haber–Weiss reactions, thereby preventing the generation of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (49). Antioxidants that are effective in chelating ferrous ions contribute to reducing oxidative stress by forming stable, water-soluble complexes with iron. These complexes facilitate the mobilization and elimination of excess iron from tissues, allowing it to be excreted safely through urine and faeces (43). The IC₅₀ value for metal chelating activity for bael gum was found to be 765.7 ± 1.5 mg/g. Comparatively, previous research has reported varying antioxidant potentials across different parts of the bael plant. For instance, a study by Wali et al. (50) evaluated methanolic extracts of bael leaf, bark, and fruit. The leaf extract exhibited the highest DPPH radical scavenging activity with an IC₅₀ value of 249.3 ± 9.4 μg/mL, while the fruit extract showed the least activity with an IC₅₀ of 1032.2 ± 7.03 μg/mL. In terms of metal chelating activity, the leaf extract again outperformed the others, with an IC₅₀ of 165.7 ± 2.3 μg/mL, compared to 977 ± 5.7 μg/mL for the fruit extract.

Phenolic compounds are well-recognized for their antioxidant properties, contribution to human health (51). In light of this, the total phenolic content of bael gum was evaluated and found to be 90.3 ± 1 μg/g, indicating a notable presence of antioxidant constituents. Similarly, Yadav et al. (17) reported that Chironji gum exhibited substantial antioxidant activity, including significant DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging capacities, as well as metal chelating ability, further supporting the relevance of gum-derived phenolics in antioxidant defense.

3.5 Antidiabetic assay

The digestive enzymes α-amylase and α-glucosidase play essential roles in the hydrolysis of complex carbohydrates into glucose, enabling its absorption into the bloodstream. Inhibiting these enzymes can effectively slow carbohydrate digestion and reduce postprandial hyperglycemia, offering a therapeutic strategy for managing type 2 diabetes (52). Several studies have reported that phytochemicals, particularly phenolic compounds, have inhibitory effects on α-amylase and α-glucosidase, and may be useful in treatment of diabetes (53, 54). In addition, plant-derived antioxidants can shield β-cells from. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), which may help prevent diabetes brought on by ROS (55). Consequently, it is essential to explore natural sources that could be used to lower blood glucose levels. In this study, the in vitro antidiabetic potential of bael gum was evaluated by assessing its inhibitory activity against α-amylase and α-glucosidase, expressed as IC₅₀ values. The IC₅₀ values for bael gum extract were found to be 1,126 ± 18 μg/mL for α-amylase and 853 ± 15 μg/mL for α-glucosidase (Table 3), indicating a stronger inhibitory effect on α-glucosidase. These results suggest that bael gum possesses moderate antidiabetic potential and may contribute to the regulation of postprandial blood glucose levels. However, previous studies have reported significantly lower IC₅₀ values for α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibition in the leaf extracts of Aegle marmelos (56, 57), indicating that bael leaves exhibit superior antidiabetic activity compared to bael gum.

3.6 UHPLC-QTOF-MS analysis of bael gum

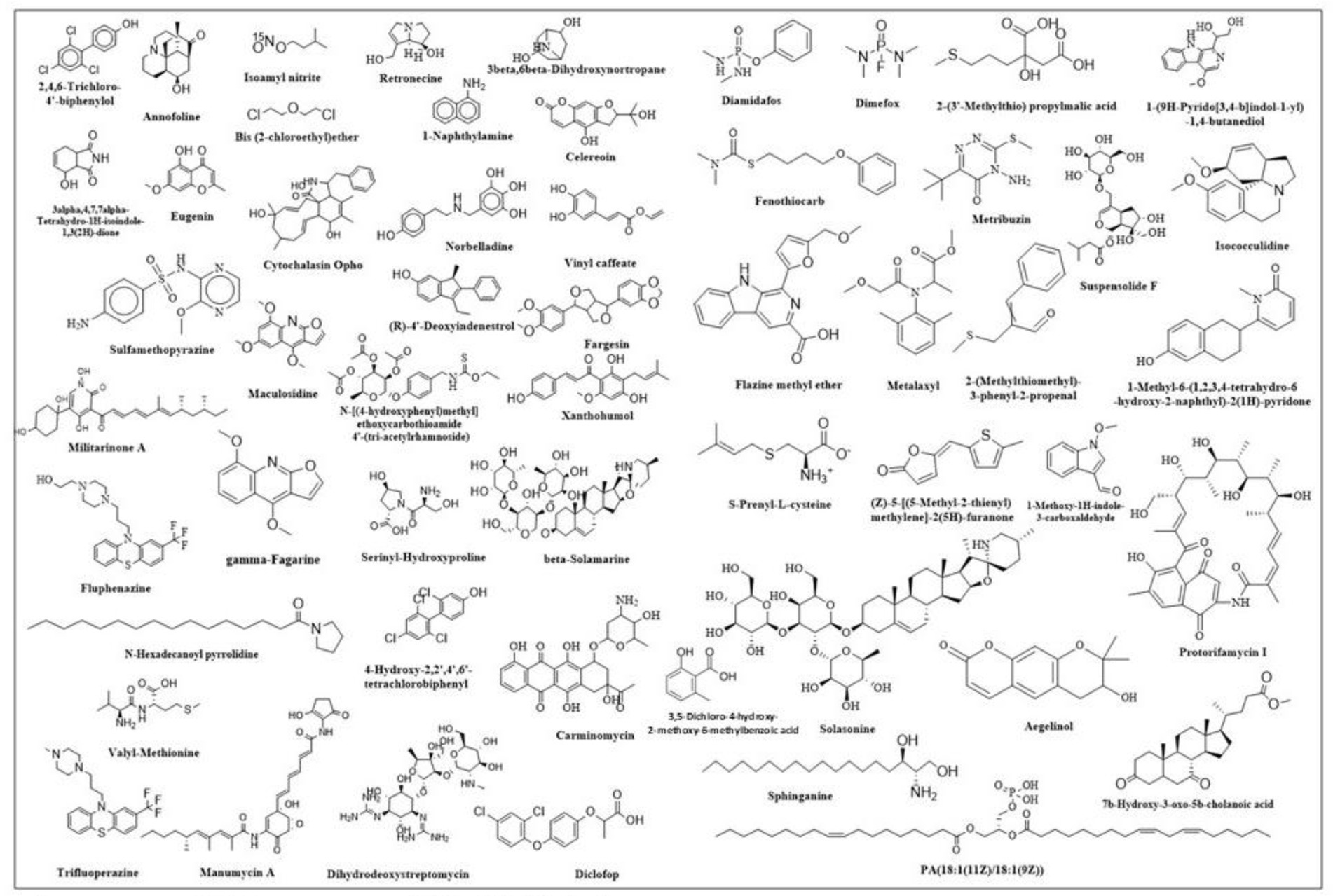

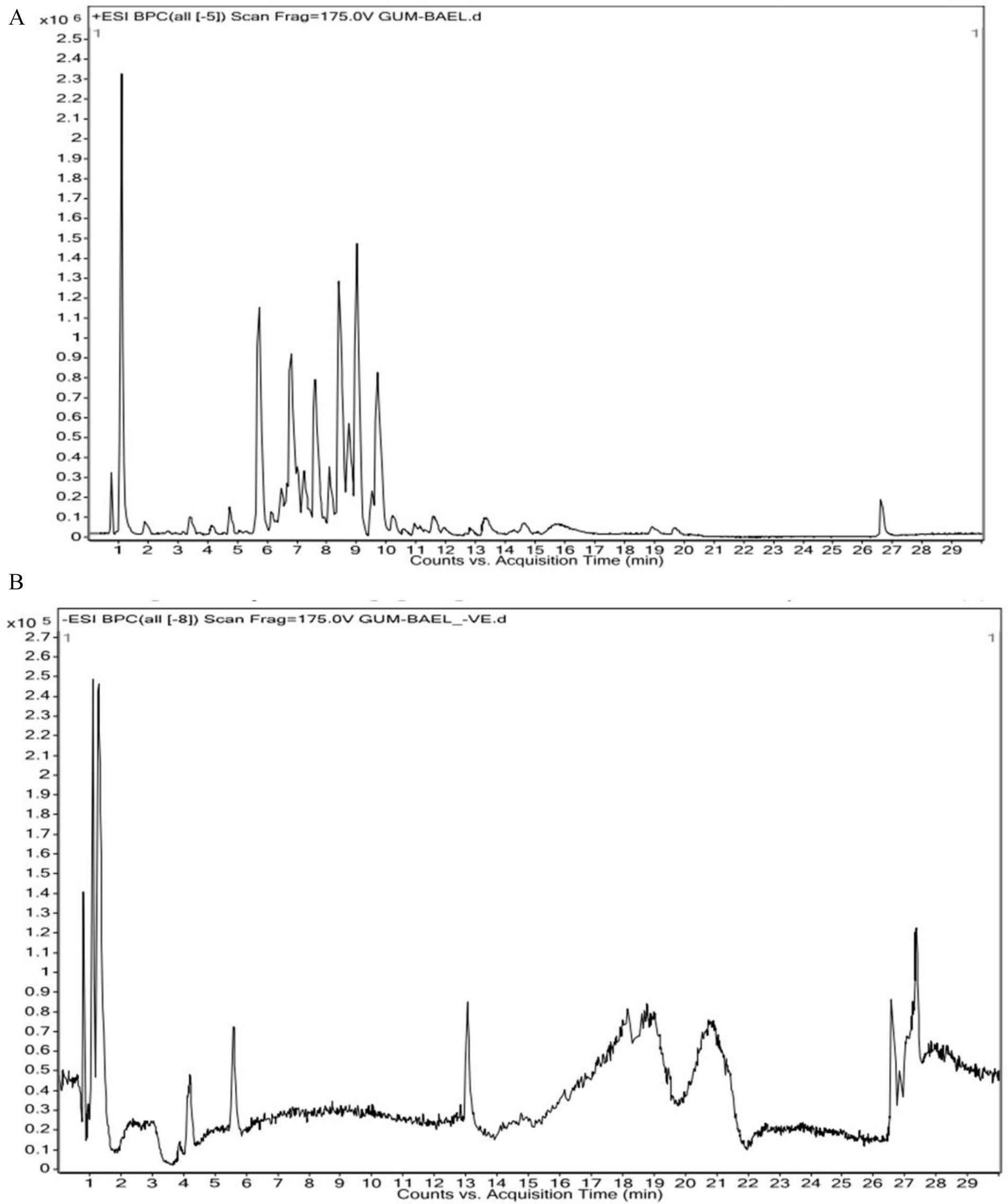

The findings of the analysis using liquid chromatography-time of flight mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) are shown in Table 4. A total of 71 phytochemicals were identified in the bael gum aqueous extract, comprising 67 in positive mode and 4 in negative mode. The LC–MS/MS spectra are illustrated in Figures 3A,B, while the structures of the identified compounds are depicted in Figure 4. The functions of 17 of the 67 compounds found by positive mode analysis were unknown, whereas the 50 bioactive compounds were divided into various classes such as alkaloids, alkyl group, amine, amyl group, aromatic ether, benzene sulfonamides, carboxylic acids, chalcones, chromones, cinnamaldehydes, coumaric acids, cysteine, dipeptides, dipeptides, furanoquinolines, glycoalkaloid, glycoside, hydroxybiphenyls, indoles, lignans, monohydroxy bile acids, n-acylpyrrolidine, o-methoxybenzoic acids, organic compound, organic phosphoramides, phenols, phenothiazine, Polyketides, proline, psoralens, steroidal saponins, terpene glycosides, thiophenes, and triazines. Table 5 outlines the functions of the found molecule, showing that bael gum has a significant bioactive compound with a variety of applications, including antifungal (β-Solamarine, 4-Hydroxy-2,2′,4′,6′-tetrachlorobiphenyl metalaxyl), anti-cancerous (3α, 4,7,7α-Tetrahydro-1H-isoindole-1,3(2H)-dione, Carminomycin, Solasonine, β-Solamarine, Aegelinol, Fluphenazine, Xanthohumol, Serinyl-Hydroxyproline, Manumycin A), antibacterial (Retronecine, Celereoin, Aegelinol, Carminomycin, Dihydrodeoxystreptomycin, Serinyl-Hydroxyproline, Manumycin-A), antimicrobial (Sulfamethopyrazine, Celereoin, N-Hexadecanoyl pyrrolidine, Manumycin-A,), antiviral (Eugenin), antimalarial (Maculosidine, Benzenesulfonamides), acaricide (Dimefox, Fenothiocarb), antioxidant (Retronecine, 1-Naphthylamine, Norbelladine, Celereoin, 1-Methoxy-1H-indole-3-carboxaldehyde, Vinyl caffeate, Aegelinol, Serinyl-Hydroxyproline, 7b-Hydroxy-3-oxo-5b-cholanoic acid), antidiabetic (3β,6β-Dihydroxynortropane), anti-atherosclerotic (Manumycin A), antiparasitic (Benzenesulfonamides), anti-inflammatory (β-Solamarine, Fargesin, Norbelladine), antineoplastic (β-Solamarine), and antiprotozoal (β-Solamarine, γ-Fagarine) compounds.

Figure 3. (A) HR-LCMS positive chromatogram of bael gum extract showing prominent compound corresponding to retention time. (B) HR-LCMS negative chromatogram of bael gum extract showing prominent compound corresponding to the retention time.

Globally, cancer is predicted to claim the lives of 10.0 million people, and 19.3 million more cases are expected in 2020. Globally, 18,094,716 instances of cancer were reported in 2020. The rate was higher for men (206.9 per 100,000) than for women (178.1 per 100,000). Preventing cancer is therefore a major public health concern because it is getting increasingly prevalent in practically every nation. By addressing risk factors related to nutrition, exercise, and food, almost 40% of cancer cases could be prevented. Nine phytochemicals with anti-cancer properties were found in bael gum, including 3α,4,7,7α-Tetrahydro-1H-isoindole-1,3(2H)-dione, Carminomycin, Solasonine, β-Solamarine, Aegelinol, Fluphenazine, Xanthohumol, Serinyl-Hydroxyproline, and Manumycin A (58, 59). Therefore, bael gum might be a crucial source for the extraction of anti-cancer compounds. According to reports, the Arabic gum of Acacia Senegal (60), guggulipid of Commiphora mukul (61), Boswellia sacra gum samroresins (62), asafoetida gum (63), Azadirachta indica gum (64) and Chironji gum (17) also contains anti-cancerous phyto-chemicals.

The human population is currently infected with 219 different types of viruses, and the world has experienced multiple viral disease pandemics in the past that have not only negatively impacted human life (65) but also hampered economic growth and development, as well as other industries like agriculture, animals, and poultry. The documented viral pandemics include SARS-CoV-1 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) from 2002 to 2004, Influenza A H1N1 (Swine Flu) in 2009, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) CoV Infection in 2012, the Ebola Virus Pandemic from 2013 to 2016, the Zika and SARS-CoV-2 epidemics in 2015, and the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic from 2019 to 2022. In order to treat viral infections, new bioactive chemical sources must be investigated due to the global population pressure. In this context, we have also discovered Eugenin, an antiviral drug that works against SARS-CoV-2’s primary protease in the bael gum (66). Therefore, the bael gum may be essential for controlling SARS-CoV-2.

Fungal diseases, which are already a major global concern, are becoming worse for both humans and plants and are responsible for about 1.7 million fatalities each year. Only a few hundred of the 1.5 to 5.0 million fungal species (67), can infect healthy people and cause illness in humans (68, 69). Three antifungal chemicals, β-solanine, 4-Hydroxy-2,2′,4′,6′-tetrachlorobiphenyl, and Metalaxyl, have been found in bael gum. The Metalaxyl present in bael gum may have been transferred from the soil as a result of an earlier application made during the planting stage to manage the fungal disease in bael. Similarly, antifungal compounds have also been reported in different plants of gum, like mastic tree gum, Chironji gum, and asafoetida gum (17, 63).

Antioxidants are extensively used in cosmetics, medicines, and food processing industries. Because of their anti-aging properties and capacity to manage neurological diseases, diabetes mellitus, cancer, and anti-inflammatory diseases (70). People nowadays are more curious about having a diet rich in antioxidants. Besides this, they are also used in encapsulation to prevent spoilage and stabilize foods. In the present study, we have found nine antioxidant compounds in bael gum (Retronecine, 1-Naphthylamine, Norbelladine, Celereoin, 1-Methoxy-1H-indole-3-carboxaldehyde, Vinyl caffeate, Aegelinol, Serinyl-Hydroxyproline, Annofoline, and 7b-Hydroxy-3-oxo-5b-cholanoic acid), which can be used for different purposes such as food processing, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and other uses. Similarly, antioxidants have also been reported in different plant gums, such as neem (64), Cordia myxa (71), A. Senegal (72), guggul (73) and Chironji (17). The presence of an antidiabetic compound, i.e., 3β, 6β-Dihydroxynortropane, identified through phytochemical screening, supports the results of our anti-diabetic assay, indicating that bael gum can play a crucial role in preventing diabetes. The analysis of bael gum revealed the presence of several other bioactive compounds exhibiting diverse therapeutic potentials. Notably, it contains Manumycin A, known for its anti-atherosclerotic activity, which helps in preventing the formation of arterial plaques (74). The presence of Benzenesulfonamides indicates antiparasitic properties, suggesting potential use against parasitic infections (75). Compounds such as β-Solamarine, Fargesin, and Norbelladine contribute to the anti-inflammatory activity (76), while β-Solamarine also demonstrates antineoplastic effects, highlighting its possible role in cancer prevention or treatment. Furthermore, both β-Solamarine and γ-Fagarine exhibit antiprotozoal activity (77), supporting the traditional medicinal use of bael in managing protozoal infections. Overall, these findings underscore bael gum’s multifaceted pharmacological potential and its relevance in developing natural therapeutic agents.

The present study profiled bael gum using samples collected through random sampling, which provided an overall understanding of its biochemical and nutraceutical attributes. However, this approach does not account for the substantial variability that may occur among individual plants, environmental conditions, plant age, management practices, or seasonal influences. For future investigations, quantifying gum yield per plant, evaluating nutraceutical and bioactive compound variability across different genotypes and environments, and developing standardized protocols for gum extraction and characterization will be essential. Incorporating these aspects will enhance the robustness, reproducibility, and applicability of the findings, thereby strengthening the scientific value and practical relevance of bael gum research.

4 Conclusion

The findings of this study demonstrate that bael gum possesses nutraceutical and therapeutic potential, primarily due to its rich composition of antioxidants, antioxidant enzymes, and diverse bioactive compounds. These attributes make it a promising candidate for use as a natural food additive and functional ingredient. The presence of bioactive chemicals beneficial to both plant and human health suggests broad applicability in industries such as food, dairy, beverage, cosmetic, plant protection, and pharmaceutical. This study offers a novel and comprehensive insight into the phytochemical screening of bael gum and establishes it as an imperative source of compounds with the potential to cure a variety of human ailments. Given these promising results, future research should aim to conduct in vivo studies and clinical trials to validate the health benefits observed in vitro. Additionally, exploring the mechanisms of action of specific bioactive components and assessing their efficacy in functional food and therapeutic formulations will be crucial for advancing the practical applications of bael gum.

Data availability statement

The data presented in the study are deposited in the Figshare database and is available on following link: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30656966.

Author contributions

SJ: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. AY: Supervision, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Validation, Data curation, Resources, Investigation. SGu: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Validation. AR: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Conceptualization. GC: Visualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SGa: Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Software, Data curation, Visualization, Investigation, Methodology, Conceptualization. HA: Data curation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. RY: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Visualization, Validation, Data curation. GS: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization. PS: Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NK: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Validation, Conceptualization. ID: Data curation, Conceptualization, Visualization, Validation, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

For their guidance and assistance, the author would like to sincerely thank ICAR and the director of the Central Agroforestry Research Institute in Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh.

Conflict of interest

Author(s) SJ was employed by Indofil Industry Ltd.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

ABTS, 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid); APX, Ascorbate peroxidase; CAT, Catalase; CAFRI, Central Agroforestry Research Institute; DPPH, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; EC, Electrical conductivity; FRSA, Free Radical Scavenging Activity; GPS, Global Positioning System; GR, Glutathione reductase; GST, Glutathione S-transferases; NOX, NADPH oxidase; PPO, Polyphenol Oxidase; POD, Peroxidase; SOD, Superoxide dismutase; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species; TPC, Total Phenol Content; UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS, Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry.

Footnotes

References

1. Lim, T.K. Edible medicinal and non-medicinal plants, New York, London: Springer, Dordrecht Heidelberg, (2015) 824. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9511-1

2. Sarkar, T, Salauddin, M, and Chakraborty, R. In-depth pharmacological and nutritional properties of bael (Aegle marmelos): A critical review. J Agric Food Res. (2020) 2:100081. doi: 10.1016/j.jafr.2020.100081,

3. Singhal, VK, Salwan, A, Kumar, P, and Kaur, J. Phenology, pollination and breeding system of Aegle marmelos (Linn.) correa (Rutaceae) from India. New For. (2011) 42:85–100. doi: 10.1007/s11056-010-9239-3

4. Jagetia, GC, and Baliga, MS. The evaluation of nitric oxide scavenging activity of certain Indian medicinal plants in vitro: A preliminary study. J Med Food. (2004) 7:343–8. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2004.7.343,

5. Neeraj,, Bisht, V, and Johar, V. Bael (Aegle marmelos) extraordinary species of India: a review. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. (2017) 6:1870–1887. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2017.603.213

6. Bhardwaj, R.L., Role of bael fruit juice in nutritional security of Sirohi tribals. Benchmark survey report of Sirohi tribals, Krishi Vigyan Kendra. Jodhpur. (2014) 11–37.

7. Manandhar, B, Paudel, KR, Sharma, B, and Karki, R. Phytochemical profile and pharmacological activity of Aegle marmelos Linn. J Integr Med. (2018) 16:153–63. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2018.04.007,

8. Singh, R, Singh, A, Babu, N, and Navneet,. Ethno-medicinal and pharmacological activities of Aegle marmelos (Linn.) Corr: a review. Pharma Innovation J. (2019) 8:176–181.

9. Avachat, AM, Dash, RR, and Shrotriya, SN. Recent investigations of plant based natural gums, mucilages and resins in novel drug delivery systems. Indian J Pharm Educ Res. (2011) 45:86–99.

10. Amiri, MS, Mohammadzadeh, V, Yazdi, MET, Barani, M, Rahdar, A, and Kyzas, GZ. Plant-based gums and mucilages applications in pharmacology and nanomedicine: A review. Molecules. (2021) 26:1770. doi: 10.3390/molecules26061770,

11. Anbalahan, N. Pharmacological activity of mucilage isolated from medicinal plants. Int J Appl Pure Sci Agric. (2017) 3:98–113.

12. Jindal, M, Kumar, V, Rana, V, and Tiwary, AK. Exploring potential new gum source Aegle marmelos for food and pharmaceuticals: physical, chemical and functional performance. Ind Crop Prod. (2013) 45:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.12.037

13. Srivastava, A, Gowda, DV, Hani, U, Shinde, CG, and Osmani, RAM. Fabrication and characterization of carboxymethylated bael fruit gum with potential mucoadhesive applications. RSC Adv. (2015) 5:44652–44659. doi: 10.1039/c5ra05760d

14. Gaikwad, D, Patil, D, Chougale, R, and Sutar, S. Development and characterization of bael fruit gum-pectin hydrogel for enhanced antimicrobial activity. Int J Biol Macromol. (2025) 291:139082. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.139082,

15. Sujitha, B, Krishnamoorthy, B, and Muthukumaran, M. Role of natural polymers used in formulation of pharmaceutical dosage forms: a review. Int J Pharm Technol. (2012) 4:2347–62.

17. Yadav, A, Jha, S, Garg, S, Arunachalam, A, Handa, AK, and Alam, B. Unveiling nutraceutical, antioxidant properties and bioactive compound profiling of Chironji gum. Food Biosci. (2024) 62:105274. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2024.105274

18. Guinard, JX, and Mazzucchelli, R. The sensory perception of texture and mouthfeel. Trends Food Sci Technol. (1996) 7:213–219. doi: 10.1016/0924-2244(96)10025-X

19. Krishnaveni, SB, Theymoli, SB, and Sadasivam, S. Phenol sulphuric acid method. Food Chem. (1984) 15:229.

20. Pawar, HA, and D’Mello, PM. Spectrophotometric estimation of total polysaccharides in Cassia tora gum. J Appl Pharm Sci. (2011) 1:93–95.

21. Lowry, OH, Rosebrough, NJ, Farr, AL, and Randall, RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. (1951) 193:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9258(19)52451-6,

22. Nelson, DW, and Sommers, LE. Determination of total nitrogen in plant material 1. Agron J. (1973) 65:109–112. doi: 10.2134/agronj1973.00021962006500010033x

23. Roland, JF, and Gross, AM. Quantitative determination of amino acids. Anal Chem. (1954) 26:502–5. doi: 10.1021/ac60087a022

24. da Silva, CR, and Koblitz, MGB. Partial characterization and inactivation of peroxidases and polyphenol-oxidases of umbu-cajá (Spondias spp.). Cienc Tecnol Aliment. (2010) 30:790–6. doi: 10.1590/S0101-20612010000300035

25. Sadasivam, S., and Manickam, A., Biochemical methods, in: 1st ed., New Age International (P) Limited, New Delhi, 1996: 124–126.

26. Nakano, Y, and Asada, K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. (1981) 22:867–880. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a076232

27. Kaundal, A, Rojas, C, and Mysore, K. Measurement of NADPH oxidase activity in plants. Bio Protoc. (2012) 2:e278. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.278

28. Gowthami, N, and Vasantha, S. Cadmium induced changes in the growth and oxidative metabolism of green gram-Vigna radiata Linn. J Plant Biochem Physiol. (2015) 3:151–3. doi: 10.4172/2329-9029.1000151

29. Habig, WH, Pabst, MJ, and Jakoby, WB. Glutathione S-transferases. J Biol Chem. (1974) 249:7130–9. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)42083-8

30. Goldberg, DM, and Spooner, RJ. Assay of glutathione reductase In: HV Bergmeyen, editor. Methods of enzymatic analysis. 3rd Editio ed. Deerfiled Beach: Verlog Chemie (1983). 258–65.

31. Jha, S, Gupta, S, Bhattacharyya, P, Ghosh, A, and Mandal, P. In vitro antioxidant and antidiabetic activity of oligopeptides derived from different mulberry (Morus alba L.) cultivars. Pharm Res. (2018) 10:361. doi: 10.4103/pr.pr_70_18

32. Re, R, Pellegrini, N, Proteggente, A, Pannala, A, Yang, M, and Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol Med. (1999) 26:1231–7. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00315-3,

33. Dinis, TCP, Madeira, VMC, and Almeida, LM. Action of phenolic derivatives (acetaminophen, salicylate, and 5-Aminosalicylate) as inhibitors of membrane lipid peroxidation and as peroxyl radical scavengers. Arch Biochem Biophys. (1994) 315:161–9. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1485,

34. Patil, JS, Marapur, SC, Kadam, DV, and Kamalapur, MV. Pharmaceutical and medicinal applications of olibanum gum and its constituents: A review. J Pharm Res. (2010) 3:587–9.

35. Ambily, R, Kour, M, Shynu, M, Bhatia, B, and Aravindakshan, TV. Evaluation of antibacterial activity of laccase from Bacillus subtilis. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. (2020) 9:2960–2963. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2020.905.351

36. Sudha, P, Zinjarde, SS, Bhargava, SY, and Kumar, AR. Potent α-amylase inhibitory activity of Indian ayurvedic medicinal plants. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2011) 11:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-11-5

37. Li, DQ, Qian, ZM, and Li, SP. Inhibition of three selected beverage extracts on α-glucosidase and rapid identification of their active compounds using HPLC-DAD-MS/MS and biochemical detection. J Agric Food Chem. (2010) 58:6608–13. doi: 10.1021/jf100853c,

38. Haron, FK, Shah, MD, Yong, YS, Tan, JK, Lal, MTM, and Venmathi Maran, BA. Antiparasitic potential of methanol extract of Brown alga Sargassum polycystum (Phaeophyceae) and its LC-MS/MS metabolite profiling. Diversity (Basel). (2022) 14:796. doi: 10.3390/d14100796,

39. Lelon, JK, Jumba, IO, Keter, JK, Chemuku, W, and Oduor, FDO. Assessment of physical properties of gum arabic from Acacia senegal varieties in Baringo District, Kenya. African J Plant Sci. (2010) 4:95–98.

40. Bashir, M, and Haripriya, S. Assessment of physical and structural characteristics of almond gum. Int J Biol Macromol. (2016) 93:476–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.09.009,

41. Zhou, Y, Wang, D, Zhou, S, Duan, H, Guo, J, and Yan, W. Nutritional composition, health benefits, and application value of edible insects: A review. Foods. (2022) 11:3961. doi: 10.3390/foods11243961,

42. Gill, SS, and Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. (2010) 48:909–30. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.016,

43. Hebbel, R, Leung, A, and Mohandas, N. Oxidation-induced changes in microrheologic properties of the red blood cell membrane. Blood. (1990) 76:1015–20. doi: 10.1182/blood.V76.5.1015.1015,

44. Ali, AA, and Alqurainy, F. Activities of antioxidants in plants under environmental stress In: N Motohashi, editor. The lutein-prevention and treatment for diseases. India: Transworld Research Network (2006). 187–256.

45. Asada, K. The water-water cycle in chloroplasts: scavenging of active oxygens and dissipation of excess photons. Annu Rev Plant Biol. (1999) 50:601–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.601,

46. Rao, SVC, and Reddy, AR. Glutathione reductase: A putative redox regulatory system in plant cells In: Khan, NA editor. Sulfur assimilation and abiotic stress in plants. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg (2008). 111–47.

47. Gupta, SK, and Mandal, P. Involvement of calcium ion in enhancement of antioxidant and antidiabetic potential of fenugreek sprouts. Free Radic Antioxid. (2015) 5:74–82. doi: 10.5530/fra.2015.2.5

48. Benmohamed, M, Guenane, H, Messaoudi, M, Zahnit, W, Egbuna, C, Sharifi-Rad, M, et al. Mineral profile, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, anti-urease and anti-α-amylase activities of the unripe fruit extracts of Pistacia atlantica. Molecules. (2023) 28:349. doi: 10.3390/molecules28010349,

49. Gulcin, İ, and Alwasel, SH. Metal ions, metal chelators and metal chelating assay as antioxidant method. PRO. (2022) 10:132. doi: 10.3390/pr10010132

50. Wali, A, Gupta, M, Mallick, SA, Gupta, S, and Jaglan, S. Antioxidant potential and phenolic contents of leaf, bark and fruit of Aegle marmelos. J Trop Forest Sci. (2016) 28:268–74.

51. Hu, W, Sarengaowa, W, Guan, Y, and Feng, K. Biosynthesis of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity in fresh-cut fruits and vegetables. Front Microbiol. (2022) 13:906069. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.906069

52. Zengin, G, Sarikurkcu, C, Aktumsek, A, Ceylan, R, and Ceylan, O. A comprehensive study on phytochemical characterization of Haplophyllum myrtifolium Boiss. Endemic to Turkey and its inhibitory potential against key enzymes involved in Alzheimer, skin diseases and type II diabetes. Ind Crop Prod. (2014) 53:244–51. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.12.043

53. Ibrahim, MA, Koorbanally, NA, and Islam, MS. Antioxidative activity and inhibition of key enzymes linked to Type-2 diabetes (α-glucosidase and α-amylase) by Khaya Senegalensis. Acta Pharma. (2014) 64:311–24. doi: 10.2478/acph-2014-0025,

54. Ademiluyi, A, and Oboh, G. Soybean phenolic-rich extracts inhibit key-enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes (α-amylase and α-glucosidase) and hypertension (angiotensin I converting enzyme) in vitro. Exp Toxicol Pathol. (2013) 65:305–9. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2011.09.005,

55. Patel, DK, Kumar, R, Laloo, D, and Hemalatha, S. Diabetes mellitus: an overview on its pharmacological aspects and reported medicinal plants having antidiabetic activity. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. (2012) 2:411–20. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60067-7,

56. Ahmad, W, Amir, M, Ahmad, A, Ali, A, Ali, A, Wahab, S, et al. Aegle marmelos leaf extract phytochemical analysis, cytotoxicity, in vitro antioxidant and antidiabetic activities. Plants. (2021) 10:2573. doi: 10.3390/plants10122573,

57. Venkatesan, S, Rajagopal, A, Muthuswamy, B, Mohan, V, and Manickam, N. Phytochemical analysis and evaluation of antioxidant, antidiabetic, and anti-inflammatory properties of Aegle marmelos and its validation in an in-vitro cell model. Cureus. (2024) 16:e70491. doi: 10.7759/cureus.70491,

58. Li, JX, Li, RZ, Sun, A, Zhou, H, Neher, E, Yang, JS, et al. Metabolomics and integrated network pharmacology analysis reveal tricin as the active anti-cancer component of Weijing decoction by suppression of PRKCA and sphingolipid signaling. Pharmacol Res. (2021) 171:105574. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105574

59. Otręba, M, and Kośmider, L. In vitro anticancer activity of fluphenazine, perphenazine and prochlorperazine. A review. J Appl Toxicol. (2021) 41:82–94. doi: 10.1002/jat.4046,

60. Nasir, O, Wang, K, Foller, M, Bhandaru, M, Sandulache, D, Artunc, F, et al. Downregulation of angiogenin transcript levels and inhibition of colonic carcinoma by gum Arabic (Acacia senegal). Nutr Cancer. (2010) 62:802–10. doi: 10.1080/01635581003605920,

61. Xiao, D, Zeng, Y, Prakash, L, Badmaev, V, Majeed, M, and Singh, SV. Reactive oxygen species-dependent apoptosis by gugulipid extract of ayurvedic medicine plant Commiphora mukul in human prostate cancer cells is regulated by c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Mol Pharmacol. (2011) 79:499–507. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.068551,

62. Ni, X, Suhail, MM, Yang, Q, Cao, A, Fung, K-M, Postier, RG, et al. Frankincense essential oil prepared from hydrodistillation of Boswellia sacra gum resins induces human pancreatic cancer cell death in cultures and in a xenograft murine model. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2012) 12:253. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-253,

63. Devanesan, S, Ponmurugan, K, Alsalhi, MS, and Al-Dhabi, NA. Cytotoxic and antimicrobial efficacy of silver nanoparticles synthesized using a traditional phytoproduct, asafoetida gum. Int J Nanomedicine. (2020) 15:4351–62. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S258319,

64. Samrot, AV, Lavanya Agnes Angalene, J, Roshini, SM, Stefi, SM, Preethi, R, Raji, P, et al. Purification, characterization and exploitation of Azadirachta indica gum for the production of drug loaded nanocarrier. Mater Res Express. (2020) 7:055007. doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/ab8b16

65. Bhadoria, P, Gupta, G, and Agarwal, A. Viral pandemics in the past two decades. J Family Med Prim Care. (2021) 10:2745–50. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2071_20,

66. Saraswat, J, Singh, P, and Patel, R. A computational approach for the screening of potential antiviral compounds against SARS-CoV-2 protease: ionic liquid vs herbal and natural compounds. J Mol Liq. (2021) 326:115298. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115298,

67. O’Brien, HE, Parrent, JL, Jackson, JA, Moncalvo, JM, and Vilgalys, R. Fungal community analysis by large-scale sequencing of environmental samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. (2005) 71:5544–50. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5544-5550.2005,

68. Kohler, JR, Casadevall, A, and Perfect, J. The Spectrum of Fungi that infects humans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. (2015) 5:a019273–3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019273,

69. Jiang, G, Xiao, X, Zeng, Y, Nagabhushanam, K, Majeed, M, and Xiao, D. Targeting beta-catenin signaling to induce apoptosis in human breast cancer cells by z-Guggulsterone and Gugulipid extract of ayurvedic medicine plant Commiphora mukul. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2013) 13:203. doi: 10.1186/1472-688Y13-203,

70. Rani, K. Role of antioxidants in prevention of diseases. J Applied Biotechnol Bioengineering. (2017) 4:00091. doi: 10.15406/jabb.2017.04.00091

71. Keshani-Dokht, S, Emam-Djomeh, Z, Yarmand, MS, and Fathi, M. Extraction, chemical composition, rheological behavior, antioxidant activity and functional properties of Cordia myxa mucilage. Int J Biol Macromol. (2018) 118:485–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.06.069,

72. Ali, BH, Ziada, A, Al Husseni, I, Beegam, S, Al-Ruqaishi, B, and Nemmar, A. Effect of Acacia gum on blood pressure in rats with adenine-induced chronic renal failure. Phytomedicine. (2011) 18:1176–80. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2011.03.005,

73. Matsuda, H, Morikawa, T, Ando, S, Oominami, H, Murakami, T, Kimura, I, et al. Absolute stereostructures of polypodane- and octanordammarane-type triterpenes with nitric oxide production inhibitory activity from guggul-gum resins. Bioorg Med Chem. (2004) 12:3037–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.03.020,

74. Sugita, M, Sugita, H, and Kaneki, M. Farnesyltransferase inhibitor, manumycin A, prevents atherosclerosis development and reduces oxidative stress in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2007) 27:1390–5. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.140673,

75. Borges, JC, Carvalho, AV, Bernardino, AMR, Oliveira, CD, Pinheiro, LCS, Marra, RKF, et al. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of new benzenesulfonamides as antileishmanial agents. J Braz Chem Soc. (2014) 25:980–86. doi: 10.5935/0103-5053.20140062

76. Manimegalai, S, Rajeswari, VD, Parameswari, R, Nicoletti, M, Alarifi, S, and Govindarajan, M. Green synthesis, characterization and biological activity of Solanum trilobatum-mediated silver nanoparticles, Saudi. J Biol Sci. (2022) 29:2131–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.11.048,

77. Szewczyk, A, and Pęczek, F. Furoquinoline alkaloids: insights into chemistry, occurrence, and biological properties. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:12811. doi: 10.3390/ijms241612811,

78. Wadekar, PP, and Salunkhe, VR. Unveiling the therapeutic potential of Cichorium intybus callus: a phytochemical study. Int. J. Chem. Biochem. Sci. (2023) 24:299–306.

79. Tsiokanos, E, Tsafantakis, N, Obé, H, Beuerle, T, Leti, M, Fokialakis, N, et al. Profiling of pyrrolizidine alkaloids using a retronecine-based untargeted metabolomics approach coupled to the quantitation of the retronecine-core in medicinal plants using UHPLC-QTOF. J Pharm Biomed Anal. (2023) 224:115171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2022.115171,

80. Park, JB. Synthesis and characterization of norbelladine, a precursor of Amaryllidaceae alkaloid, as an anti-inflammatory/anti-COX compound. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. (2014) 24:5381–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.10.051,

81. Dymek, A, Widelski, J, Wojtanowski, KK, Płoszaj, P, Zhuravchak, R, and Mroczek, T. Optimization of pressurized liquid extraction of Lycopodiaceae alkaloids obtained from two Lycopodium species. Molecules. (2021) 26:1626. doi: 10.3390/molecules26061626,

82. Azam, M, Al-Resayes, SI, Wabaidur, SM, Altaf, M, Chaurasia, B, Alam, M, et al. Synthesis, structural characterization and antimicrobial activity of cu(II) and Fe(III) complexes incorporating azo-azomethine ligand. Molecules. (2018) 23:813. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040813,

83. Wang, YZ, Wang, T, Liu, WD, Luo, GZ, Lu, GY, Zhang, YN, et al. Anticancer effects of solasonine: evidence and possible mechanisms. Biomed Pharmacother. (2024) 171:116146. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116146,

84. Awadelkareem, AM, Al-Shammari, E, Elkhalifa, AEO, Adnan, M, Siddiqui, AJ, Snoussi, M, et al. Phytochemical and in silico ADME/tox analysis of Eruca sativa extract with antioxidant, antibacterial and anticancer potential against Caco-2 and HCT-116 colorectal carcinoma cell lines. Molecules. (2022) 27:1409. doi: 10.3390/molecules27041409,

85. Parasuraman, S, Yu Ren, L, Chik Chuon, BL, and Wong Kah Yee, S. Computer-aided prediction of biological activities and toxicological properties of the constituents of Solanum trilobatum. Rapports de Pharmacie. (2015) 1:59–63.

86. Duan, H, Cheng Wang, G, Khan, GJ, hui Su, X, lan Guo, S, ming Niu, Y, et al. Identification and characterization of potential antioxidant components in Isodon amethystoides (Benth.) Hara tea leaves by UPLC-LTQ-orbitrap-MS. Food Chem Toxicol. (2021) 148:111961. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111961,

87. Wang, G, Gao, JH, He, LH, Yu, XH, Zhao, ZW, Zou, J, et al. Fargesin alleviates atherosclerosis by promoting reverse cholesterol transport and reducing inflammatory response. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. (2020) 1865:158633. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2020.158633,

88. Rosselli, S, Maggio, AM, Faraone, N, Spadaro, V, Morris-Natschke, SL, Bastow, KF, et al. The cytotoxic properties of natural coumarins isolated from roots of Ferulago campestris (Apiaceae) and of synthetic ester derivatives of aegelinol. Nat Prod Commun. (2009) 4:1701–06. doi: 10.1177/1934578x0900401219

89. Zahran, EM, Mohamad, SA, Yahia, R, Badawi, AM, Sayed, AM, and Abdelmohsen, UR. Anti-otomycotic potential of nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: an integrated in vitro, in silico and phase 0 clinical study. Food Funct. (2022) 13:11083–96. doi: 10.1039/D2FO02382B,

90. Brazhnikova, MG, Zbarsky, VB, Ponomarenko, VI, and Potapova, NP. Physical and chemical characteristics and structure of carminomycin, a new antitumor antibiotic. J Antibiot (Tokyo). (1974) 27:254–9. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.27.254,

91. Pulkoski-Gross, A, Li, J, Zheng, C, Li, Y, Ouyang, N, Rigas, B, et al. Repurposing the antipsychotic trifluoperazine as an antimetastasis agent. Mol Pharmacol. (2015) 87:501–12. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.096941,

92. Amoa Onguéné, P, Ntie-Kang, F, Lifongo, LL, Ndom, JC, Sippl, W, and Mbaze, LMA. The potential of anti-malarial compounds derived from African medicinal plants, part I: a pharmacological evaluation of alkaloids and terpenoids. Malar J. (2013) 12:449. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-449,

93. Mizuta, M, and Kanamori, H. Mutagenic activities of dictamnine and γ-fagarine from Dictamni radicis cortex (rutaceae). Mutat Res Lett. (1985) 144:221–5. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(85)90054-5,

94. Patil, SV, Mane, RP, Mane, SD, Anbhule, PV, and Shimple, VB. Chemical composition of essential oil from seeds of Pinda concanensis: an endemic plant of Western Ghats of India. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. (2016) 41:49–51.

95. Gerhauser, C, Alt, A, Heiss, E, Gamal-Eldeen, A, Klimo, K, Knauft, J, et al. Cancer chemopreventive activity of xanthohumol, a natural product derived from hop. Mol Cancer Ther. (2002) 1:959–69.

96. Bhattacharya, E, and Mandal Biswas, S. Role of tartaric acid in the ecology of a zoochoric fruit species, Tamarindus indica. L. Int J Fruit Sci. (2021) 21:819–25. doi: 10.1080/15538362.2021.1936347

97. Cen, Q, Fan, J, Zhang, R, Chen, H, Hui, F, Li, J, et al. Impact of Ganoderma lucidum fermentation on the nutritional composition, structural characterization, metabolites, and antioxidant activity of soybean, sweet potato and Zanthoxylum pericarpium residues. Food Chem X. (2024) 21:101078. doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2023.101078,

Keywords: antidiabetic, antioxidant, bael, ethnomedical, gum, nutraceutical

Citation: Jha S, Yadav A, Gupta SK, Ram A, Choudhary G, Garg S, Anuragi H, Yadav R, Sandeep GP, Sonwalkar PM, Kumar N and Dev I (2025) Phytochemical profiling and bioactive potential of bael gum using UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS: a novel nutraceutical source. Front. Nutr. 12:1720060. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1720060

Edited by:

Juliana Aparecida Correia Bento, Federal University of Mato Grosso, BrazilReviewed by:

Anwara Khatun, Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University, BangladeshLuciano Lião, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brazil

Copyright © 2025 Jha, Yadav, Gupta, Ram, Choudhary, Garg, Anuragi, Yadav, Sandeep, Sonwalkar, Kumar and Dev. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sandeep Garg, c2FuZGVlcGdhcmc3MDQ5NkBnbWFpbC5jb20=; Ashok Yadav, YXNob2tjYWZyaWhvcnQxQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Suchisree Jha

Suchisree Jha Ashok Yadav

Ashok Yadav Saran Kumar Gupta

Saran Kumar Gupta Asha Ram

Asha Ram Girija Choudhary

Girija Choudhary Sandeep Garg

Sandeep Garg Hirdayesh Anuragi

Hirdayesh Anuragi Ronak Yadav

Ronak Yadav Guntukogula Pattabhi Sandeep

Guntukogula Pattabhi Sandeep Prasad Manikrao Sonwalkar

Prasad Manikrao Sonwalkar Naresh Kumar

Naresh Kumar Inder Dev

Inder Dev