- 1Inner Mongolia Medical University, Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, China

- 2Department of General Surgery, The First Medical Center of PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China

- 3The School of Electronic and Information Engineering, Beihang University, Beijing, China

The development of non-invasive probes with significant penetration depth is crucial for quickly characterizing biological tissues during surgical resection specimens, ensuring the full removal of tumors. This paper presents a novel zirconia probe designed to transmit low-power transcutaneous signals for identifying subcutaneous tumors without damaging biological tissues. The probe features a high dielectric constant and combines zirconia with surface-coated copper layers that have a low dielectric constant. This design achieves ultra-wideband matching from 2.8 GHz to 15.1 GHz for biological tissues. Simulations and experimental measurements on ex vivo porcine skin, fat tissue, and muscle tissue placed above the probe allowed us to differentiate tissues using reflection coefficient analysis. The results showed a penetration depth of 19 mm, with biological safety confirmed through specific absorption rate (SAR) simulations. Tumor phantoms embedded within biological matrices demonstrated the probe’s ability to detect lesions larger than 5 mm in diameter. Finally, the potential of the probe for rapid clinical identification was verified through tumor detection and scanning imaging of clinical samples.

1 Introduction

During surgery, the pathological evaluation of the resected tissue samples is considered the gold standard for confirming the complete removal of the tumors. Since tumor tissues can exist at various depths within samples, the classical histopathological method is microscopic frozen section analysis (FS), including processing steps such as freezing, slicing, staining, and microscopic analysis, which are essential for detection. However, the lengthy nature of these procedures often requires extended operative times [1, 2], which can pose significant risks to patients. Therefore, it is crucial to develop a technology that offers deep tissue penetration and rapid characterization.

Conventional clinical tumor detection methods, including X-ray [3, 4], ultrasound [5, 6], and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [7, 8], are used primarily for preoperative patient screening. X-ray techniques pose inherent risks due to exposure to ionizing radiation [9], which can lead to potential secondary carcinogenesis. MRI systems are associated with high operational costs and prolonged examination times [10], while ultrasound diagnostics are significantly dependent on the operator’s skill [11, 12] and often do not meet the requirements for real-time surgery monitoring.

Consequently, researchers leverage relative permittivity values in biological tissues for tissue differentiation, primarily employing the coaxial reflection technique [13, 14] and resonance methodology [15, 16].

In [17], the reflection coefficients of bovine hepatic tissues across the frequency range from 10 MHz to 3 GHz were measured utilizing a coaxial probe, obtaining complex permittivity values through multistage calibration protocols (Open-Short-Water) [18]. Subsequent research [19] employed an SMA-based coaxial probe to characterize the dielectric properties of solute-containing solutions and biological tissues over an operational bandwidth ranging from 10 MHz to 6 GHz. Reference [20] used a wideband electromagnetic reflection methodology for the identification of biological tissue, establishing that coaxial probes with varying diameters achieve maximum penetration depths of 0.6 mm. Moreover, the 40 GHz resonant probe presented in [21] achieved a measured tissue penetration depth of 0.65 mm in experimental evaluations.

Although the above methods address the challenge of real-time tissue identification during surgery, their limited penetration depths impede reliable detection of neoplasms within pathological specimens. Consequently, researchers have focused on novel probe designs that exploit antenna beam-focusing characteristics [22] to achieve enhanced tissue penetration.

Professor Asimina Kiourti [23] discusses an antenna design that utilizes a conical polylactic acid (PLA) matrix infused with distilled water, specifically engineered for low-loss communication in implants within the 1.4 GHz–8.5 GHz frequency range. Simulation results showed a transmission loss of 19.21 dB at 2.4 GHz when the antenna was positioned 2 cm subdermally. In subsequent work described in [24], the conical substrate was replaced with plastic, which extended the operational bandwidth from 1.07 GHz to 11.9 GHz. Simulations indicated a transmission loss of 21.4 dB at 2.4 GHz when the antenna was placed 3 cm deep in tissue. Further developments in [25] further modified the conical core by incorporating zirconia filled with PLA, resulting in an operational bandwidth spanning from 1 GHz to 5 GHz. Achieving similar transmission loss performance while eliminating the challenges associated with the volatility of aqueous solutions.

The previous work significantly enhanced the ability to penetrate biological tissues. They were not applied to the identification of clinical pathological samples. Ensuring the long-term stable operation of the probe while using distilled water poses challenges. Additionally, PLA materials require precise excavation and filling of the zirconia base, resulting in high processing specifications. Relying solely on transmission losses at a single frequency makes it difficult to differentiate between biological tissues. Therefore, a new probe structure needs to be designed for effective identification of biological tissues.

This study introduces a broadband probe designed for deep penetration into biological tissue, with dimensions of 25.1

This study introduces three key innovations in surgical tumor detection technology: 1) A novel cone-shaped probe made from zirconia showing excellent biomaterial compatibility, allowing quick identification of tumor tissue during surgery. 2) By utilizing the differences in broadband reflection coefficient and harmonic shift of the probe under different biological tissues, it enables real-time discrimination of tissue types. 3) The design achieves wideband frequency matching from 2.8 GHz to 15.1 GHz, enabling a tissue penetration depth of 19 mm even with low-power signal injection (7 dBm), ensuring biological safety through controlled SAR.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 delineates the probe design methodology and the architecture of the measurement system. Section 3 characterizes the operational frequency band, evaluates biological tissue discrimination capabilities, quantifies penetration depth performance, and details SAR simulations. Section 4 obtains the resolution of the tumor probe by measuring pork tissue containing bacon. We verify the feasibility of intraoperative tumor detection using breast cancer sample tissue obtained during surgery. Section 5 provides a comprehensive overview of the findings and implications.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Probe design

To achieve broadband impedance matching with biological tissues while maintaining excellent biosafety [25], appropriate probe materials must be selected and engineered. Biological tissues exhibit frequency-dependent dielectric properties, where low relative permittivity minimises transmission loss at high frequencies and high relative permittivity enhances signal integrity at lower frequencies [26]. Accordingly, ADT-

To determine the optimal geometric configuration, three probe structures were designed and evaluated: rectangular, conical, and pyramidal. The final design features a contact area of 25.1

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the probe used for biological tissue identification. Probe 1 is a rectangular structure, probe 2 is a conical structure, and probe 3 is a square conical structure.

2.2 Measurement system

Following structural finalization, Figure 2a details the dimensional specifications of the probe assembly and its connector interface. The sintered zirconia fabricated in a truncated square conical shape exhibits exceptional mechanical rigidity. This substrate features 35

Figure 2. Biological tissue identification probe’s structural model and measurement system. (a) Key parameters of the wideband bio-matched probe’s structural model and simulated tissue layers. (b) Schematic diagram of the measurement system, comprising a VNA Core component for signal processing and data acquisition, a probe optimized for tissue measurements, and a 3-D Scanning Stage that ensures precise control of probe contact with the tissue.

Table 1. Key parameters of the probe matching model and tissue simulation model in Figure 2a.

As shown in Figure 2b, the complete measurement system consists of the following core components. The vector network analyzer (VNA) generates broadband signals that propagate through a coaxial RF cable to the probe, which electromagnetically couples the energy to the biological tissue surface. Reflected signals from tissue interfaces are subsequently captured by the probe and routed back to the VNA for derivation of the reflection coefficient

Before conducting experimental measurements, it is essential to rigorously calibrate the VNA. The calibration process involves several sequential steps. First, an RF line is used to connect the SMA interface to the VNA. Next, a calibration kit, which includes short, open, load, and through standards, is employed. During this phase, the configuration is systematically set, defining the measurement format and frequency range from 10 MHz to 20 GHz. A total of 2,001 discrete frequency points are designated. The output power is optimized to 7 dBm. All acquired data are archived in CSV format to ensure compatibility across different platforms. Finally, a comprehensive Short-Open-Load-Through (SOLT) calibration procedure is performed to eliminate systematic measurement errors.

To ensure system stability, the probe is rigidly affixed to a high-precision 3D platform, suppressing mechanical vibration artifacts and eliminating measurement errors from positional variations. Throughout the experiments, a precisely calibrated contact pressure of 5.0

2.3 Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chinese PLA General Hosptial approved the study protocol (Approval No. S2024-023-02). All participants were adults and provided written informed consent prior to participation. No minors were included in this study. The consent process included a detailed explanation of study objectives, potential risks, and data usage. Participants signed consent forms, which are securely archived by the research team. The ethics committee did not waive the requirement for informed consent.

3 Performance of the probe

3.1 Operating frequency band

To establish the probe’s effective operational bandwidth, fresh porcine abdominal tissue was procured commercially and dissected into skin, fat, and muscle tissue sections. Each specimen was precision sectioned to 40

Figure 3 presents the simulated and measured

Figure 3. Frequency response characteristics of the probe, comparing simulation result with measurement result.

3.2 Identification of biological tissues

To evaluate the feasibility of tissue discrimination via characterization, we first characterized the simulated

Figure 4. Identification results of skin, fat, and muscle biological tissue characteristics. (a) Frequency response characteristics of

Experimental validation of simulated resonance behavior was subsequently performed. Figure 4b confirms that measured

Figure 4c presents a comparative analysis of three distinct resonance points derived from both simulation and experimental datasets across tissue types. Results consistently demonstrate muscle exhibiting the lowest resonant frequencies, fat maintaining the highest, and skin occupying intermediate values across all measurement points. This consistent hierarchical pattern manifests in both datasets, confirming the reproducibility of tissue-specific electromagnetic responses. Precise alignment of multiple resonant peaks between simulated and experimental results establishes that these spectral features originate from intrinsic tissue dielectric properties rather than measurement artifacts. Collectively, these findings verify that biological tissues’ electromagnetic resonance behavior can be reliably characterized through both simulation and measurement, with fundamental resonances providing a robust discriminatory signature for tissue classification.

3.3 Penetration depth

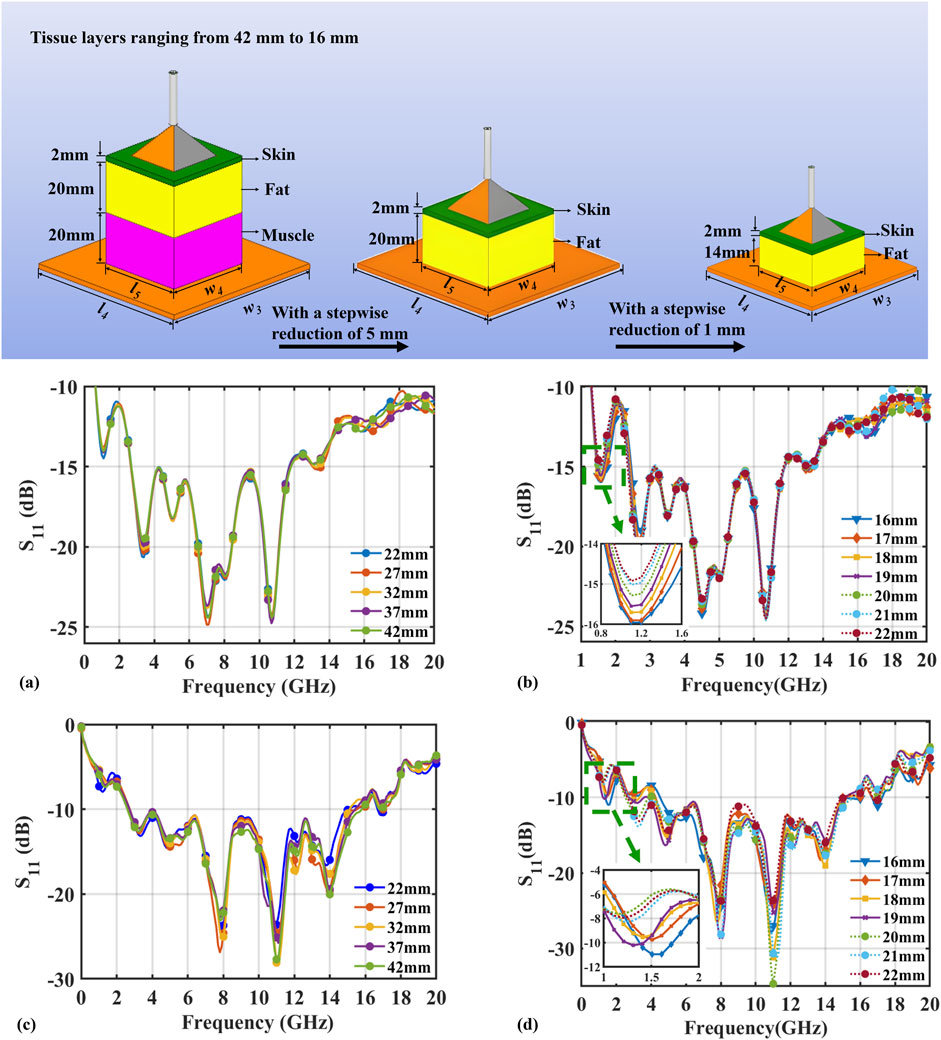

The penetration depth simulation for the probe was systematically investigated using a stratified tissue thickness reduction methodology, as presented in Figures 5a,b. Initial evaluations employed a 42 mm muscle layer, incrementally reduced in 5 mm steps to characterize

Figure 5. The simulation and experimental results of the

Results demonstrate that penetration depth is quantifiable through

Figure 5a confirms negligible penetration effects during the 42mm to 22 mm thickness reduction phase, evidenced by invariant

Characterized by a 200 MHz downward resonance shift. Progressive reduction experiments conclusively established 19 mm as the maximum effective penetration depth.

Experimental assessment of the probe’s penetration depth characteristics is presented in Figures 5c,d, employing a two-phase protocol. Initial evaluation progressively reduced a 42 mm muscle layer in 5 mm increments to identify penetration-induced curve variations. To delineate the maximum penetration depth with high precision, a subsequent analysis was performed using 1 mm decrements across a range of 22 mm–16 mm.

Analysis of measured

The probe demonstrated significant performance advantages: excellent signal stability (

Through systematic simulation and experimental validation, this study demonstrates the reliability of the probe in characterizing the dielectric properties of biological tissues within its effective penetration depth of 19 mm. The measured maximum depth shows excellent agreement with simulation results. Minor deviations attributable to unavoidable experimental interference factors fully validate the simulation model’s accuracy.

3.4 Biosafety of the probe

Biological safety assessment is paramount for intraoperative tissue identification applications. Electric field distribution analysis elucidates signal attenuation and transmission dynamics during probe operation. We quantified tissue exposure using Specific Absorption Rate (SAR), defined as electromagnetic power absorbed per unit tissue mass, through simulation models with 7 dBm input power at the probe’s operational frequency of 10 GHz.

As shown in Figures 6a,b, a peak SAR of

![Graphic with two panels. Panel (a) shows a heatmap of dB(E Field) with a color scale ranging from deep red to blue, illustrating varying field strengths. Panel (b) depicts a SAR Field [W/kg] distribution with a similar color scale. Both panels include color bars indicating maximum and minimum values for reference.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1729565/fphy-13-1729565-HTML/image_m/fphy-13-1729565-g006.jpg)

Figure 6. Biosafety simulation results of the probe. (a) Electric field distribution. (b) SAR distribution.

4 Results

4.1 Detection accuracy of tumor model

To systematically evaluate the detection sensitivity and lateral spatial resolution of the proposed probe, we constructed the tumor phantom model shown in Figure 7a. Previous studies have demonstrated that the dielectric properties of bacon closely resemble those of solid tumors and that its electromagnetic response can adequately represent real tumor tissue; bacon has therefore been widely used in tumor-related experimental studies [29]. Accordingly, bacon was selected in this work as a surrogate tumor lesion. Specifically, the bacon sample was embedded between a 2 mm skin layer and a 20 mm fat layer to mimic a superficial tumor located within subcutaneous adipose tissue, and the vertical distance between the bacon and the probe contact surface was fixed at 18 mm. As shown in Figure 7c, seven tumor phantoms with lateral dimensions ranging from 25 mm

Figure 7. Electromagnetic characterization results of embedded structures in layered biological tissues. (a) Schematic diagram of the experimental model. (b)

The experimental results were quantified by monitoring the resonance frequency shift and magnitude variation of the

Figure 7d further summarizes the changes in

4.2 Tumor detection of clinical sample

To verify the rapid response and accuracy of the proposed probe in clinical detection, fresh breast cancer specimens were obtained from patients undergoing surgery at the Chinese PLA General Hospital, in accordance with approval by the institutional ethics committee and with written informed consent. As shown in Figure 8, the specimens were placed on a three-dimensional positioning stage, and the probe was connected to a vector network analyzer (VNA) via an RF cable. Based on the tumor-responsive frequency band established in the phantom experiments, the system was configured to scan from 100 MHz to 8 GHz with 1,001 sampling points and a transmit power of 7 dBm. The contact force between the probe and the tissue surface was precisely controlled at 5

This study selected three representative regions from clinical samples (primarily consisting of adipose–glandular tissues) for measurement: the skin–adipose–glandular composite region, the adipose–glandular region, and the adipose–glandular–tumor composite region. All experiments were conducted in collaboration with clinical and pathological teams, and the results are summarized in Figure 9a. Due to the excellent broadband impedance matching of the probe and its effective coupling with the tissues, each region exhibited significantly distinct resonant characteristics in the frequency spectrum: the skin–adipose–glandular composite region showed a resonant peak at 2.18 GHz (

Figure 9. Clinical sample measurement results. (a)

Utilizing a 2.5 cm step resolution. The 3D control system executed raster scans across the surfaces of the clinical sample through a 4

5 Conclusion

Table 2 provides a systematic performance comparison between the proposed zirconia-based broadband probe and representative tumor-penetrating probes from prior studies. In comparison to conventional open-ended coaxial probes (e.g., Agilent Technologies 85070E) and resonant designs, our device exhibits significant advantages in terms of penetration depth, operational bandwidth, and spatial resolution. Specifically, whereas commercial open-ended coaxial probes are constrained to submillimeter penetration (<1 mm) within narrow frequency bands, the proposed design achieves a consistent penetration depth of 19 mm across a broad frequency range from 2.8 GHz to 15.1 GHz, a 38-fold enhancement over Agilent 85070E [30].

The probe’s ability to perform biotissue identification and its excellent resolution were verified through the identification of different pork tissues and the detection of bacon tissue. Finally, tumor detection in clinical samples verified the potential of the designed probe in rapid clinical testing.

In summary, this work establishes a novel electromagnetic approach for non-invasive tumor screening with sub-centimeter resolution in deep subcutaneous tissue. The probe architecture integrating a zirconia ceramic substrate with lithographically defined copper feeding networks overcomes the fundamental compromise between penetration depth and operational bandwidth. Demonstrated performance metrics include: 19 mm penetration at ultralow 7 dBm injection power, broadband impedance-stable operation from 2.8 GHz to 15.1 GHz, and well-controlled discrimination of embedded inclusions. These capabilities advance microwave diagnostic techniques for detecting deep-tissue malignancies.

5.1 Limitations

While the proposed broadband bio-matching probe demonstrates promising potential, several limitations merit consideration. Firstly, the current validation relies on a limited sample size. Expanded clinical trials are required to verify the probes’ rapid identification accuracy across diverse clinical samples. Secondly, although the probes exhibit favorable penetration depth and spatial resolution, evaluations have been confined to specific tissue types and geometries, without accounting for pathological alterations such as fibrosis or necrosis. Finally, the existing single-channel measurement configuration necessitates future development of multi-channel probe arrays to enable spatial mapping and imaging capabilities.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Chinese PLA General Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

GW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. ZL: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. ZY: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing. DM: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing. HX: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing. JS: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing. ZO: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing. YT: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing. XC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing. YP: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. JW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China 62476285 and the National Key Laboratory Open Fund EMC 2024N001.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the team of Academician Donglin Su from Beihang University for their invaluable support in experimental design and probe development. Special thanks are extended to Professor Jiandong Wang, Professor Xingye Chen, and Dr. Yanhua Peng for their insightful guidance and assistance throughout this project. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of all participating students for their dedication and hard work.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Mackey JR, Ecclestone B, Dinakaran D, Bigras G, Haji Reza P. H&e-like histology of unstained fresh and formalin fixed breast tissue with photo acoustic remote sensing (pars) microscopy. J Clin Oncol (2021) 39:e12590. doi:10.1200/jco.2021.39.15_suppl.e12590

2. Nowikiewicz T, Śrutek E, Głowacka-Mrotek I, Tarkowska M, Żyromska A, Zegarski W. Clinical outcomes of an intraoperative surgical margin assessment using the fresh frozen section method in patients with invasive breast cancer undergoing breast-conserving surgery – a single center analysis. Sci Rep (2019) 9:1–8. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49951-y

3. Nakamura M, Ishizuka Y, Horimoto Y, Shiraishi A, Arakawa A, Yanagisawa N, et al. Clinicopathological features of breast cancer without mammographic findings suggesting malignancy. The Breast (2020) 54:335–42. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2020.11.010

4. Gierach GL, Choudhury PP, García-Closas M. Toward risk-stratified breast cancer screening: considerations for changes in screening guidelines. JAMA Oncol (2020) 6:31–3. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3820

5. Yuan WH, Hsu HC, Chen YY, Wu CH. Supplemental breast cancer-screening ultrasonography in women with dense breasts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer (2020) 123:673–88. doi:10.1038/s41416-020-0928-1

6. Song K, Feng J, Chen D. A survey on deep learning in medical ultrasound imaging. Front Phys (2024) 12:1398393. doi:10.3389/fphy.2024.1398393

7. Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, Mann RM, Peeters PHM, Monninkhof EM, et al. Supplemental mri screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med (2019) 381:2091–102. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1903986

8. Heinke MY, Holloway L, Rai R, Vinod SK. Repeatability of mri for radiotherapy planning for pelvic, brain, and head and neck malignancies. Front Phys (2022) 10:879707. doi:10.3389/fphy.2022.879707

9. Guerra MR, Coignard J, Eon-Marchais S, Dondon MG, Le Gal D, Beauvallet J, et al. Diagnostic chest x-rays and breast cancer risk among women with a hereditary predisposition to breast cancer unexplained by a brca1 or brca2 mutation. Breast Cancer Res (2021) 23:79. doi:10.1186/s13058-021-01456-1

10. Geuzinge HA, Obdeijn IM, Rutgers EJT, Saadatmand S, Mann RM, Oosterwijk JC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of breast cancer screening with magnetic resonance imaging for women at familial risk. JAMA Oncol (2020) 6:1381–9. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2922

11. Iacob R, Iacob ER, Stoicescu ER, Ghenciu DM, Cocolea DM, Constantinescu A, et al. Evaluating the role of breast ultrasound in early detection of breast cancer in low- and middle-income countries: a comprehensive narrative review. Bioengineering (2024) 11:262. doi:10.3390/bioengineering11030262

12. Chen J, Jiang Y, Yang K, Ye X, Cui C, Shi S, et al. Feasibility of using ai to auto-catch responsible frames in ultrasound screening for breast cancer diagnosis. iScience (2022) 26:105692. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2022.105692

13. Mahdavi R, Hosseinpour P, Abbasvandi F, Mehrvarz S, Yousefpour N, Ataee H, et al. Bioelectrical pathology of the breast; real-time diagnosis of malignancy by clinically calibrated impedance spectroscopy of freshly dissected tissue. Biosens Bioelectron (2020) 165:112421. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2020.112421

14. Rao X, Chen Q, Ding L, Shahid N, Wafa S, Huang Q, et al. Application of dielectric properties for identification of normal and malignant gastrointestinal tumors and lymph nodes ex vivo. Phys Eng Sci Med (2024) 48:75–85. doi:10.1007/s13246-024-01490-1

15. Bing S, Chawang K, Chiao J. A tuned microwave resonant sensor for skin cancerous tumor diagnosis. IEEE J Electromagn RF Microwaves Med Biol (2023) 7:320–7. doi:10.1109/jerm.2023.3281726

16. Wang X, Guo H, Zhou C, Bai J. High-resolution probe design for measuring the dielectric properties of human tissues. Biomed Eng Online (2021) 20:86. doi:10.1186/s12938-021-00924-1

17. Canicattì E, Fontana N, Barmada S, Monorchio A. Open-ended coaxial probe for effective reconstruction of biopsy-excised tissues’ dielectric properties. Sensors (2024) 24:2160. doi:10.3390/s24072160

18. Linha Z, Vrba J, Kollar J, Fiser O, Pokorny T, Novak M, et al. An inexpensive system for measuring the dielectric properties of biological tissues using an open-ended coaxial probe. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas (2025) 74:1–11. doi:10.1109/TIM.2025.3561426

19. Arias-Rodríguez J, Moreno-Merín R, Martínez-Lozano A, Torregrosa-Penalva G, Ávila Navarro E. Validation of a low-cost open-ended coaxial probe setup for broadband permittivity measurements up to 6 ghz. Sens (2025) 25:3935. doi:10.3390/s25133935

20. Naqvi SAR, Mobashsher AT, Mohammed B, Foong D, Abbosh A. Handheld microwave system for in vivo skin cancer detection: development and clinical validation. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas (2024) 73:1–16. doi:10.1109/tim.2024.3398123

21. Mansutti G, Mobashsher AT, Bialkowski K, Mohammed B, Abbosh A. Millimeter-wave substrate integrated waveguide probe for skin cancer detection. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng (2020) 67:2462–72. doi:10.1109/TBME.2019.2963104

22. Zhu L, Liu N. Multimode resonator technique in antennas: a review. Electromagn Sci (2023) 1:1–17. doi:10.23919/emsci.2022.0004

23. Blauert J, Kiourti A. Bio-matched horn: a novel 1–9 ghz on-body antenna for low-loss biomedical telemetry with implants. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag (2019) 67:5054–62. doi:10.1109/TAP.2018.2889159

24. Blauert J, Kiourti A. Theoretical modeling and design guidelines for a new class of wearable bio-matched antennas. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag (2020) 68:2040–9. doi:10.1109/TAP.2019.2948727

25. Kongkiatkamon S, Rokaya D, Kengtanyakich S, Peampring C. Current classification of zirconia in dentistry: an updated review. PeerJ (2023) 11:e15669. doi:10.7717/peerj.15669

26. Rice A, Kiourti A. High-contrast low-loss antenna: a novel antenna for efficient into-body radiation. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag (2022) 70:10132–40. doi:10.1109/TAP.2022.3188354

27. Roehling S, Gahlert M, Bacevic M, Woelfler H, Laleman I. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of zirconia dental Implants—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res (2023) 34:112–24. doi:10.1111/clr.14133

28. Peng Y, Xu H, Cui S, Su D. A novel method to acquire circuit transmission characteristics by noncontact power injection and detection. Chin J Electron (2024) 34:1078–90. doi:10.23919/cje.2024.00.148

29. Lu M, Xiao X, Pang Y, Liu G, Lu H. Detection and localization of breast cancer using uwb microwave technology and cnn-lstm framework. IEEE Trans Microw Theor Techn. (2022) 70:5085–94. doi:10.1109/tmtt.2022.3209679

30. Meaney PM, Gregory AP, Epstein NR, Paulsen KD. Microwave open-ended coaxial dielectric probe: interpretation of the sensing volume re-visited. BMC Med Phys (2014) 14:3. doi:10.1186/1756-6649-14-3

31. Aydinalp C, Joof S, Dilman I, Akduman I, Yilmaz T. Characterization of open-ended coaxial probe sensing depth with respect to aperture size for dielectric property measurement of heterogeneous tissues. Sens. (2022) 22:760. doi:10.3390/s22030760

Keywords: biological tissue, penetration depth, tumor identification, ultra-wideband matching, zirconia-based probe

Citation: Wu G, Liu Z, Yang Z, Mu D, Xu H, Sun J, Ou Z, Tian Y, Chen X, Peng Y and Wang J (2026) A zirconia-based wideband biological tissue identification probe with enhanced penetration depth. Front. Phys. 13:1729565. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2025.1729565

Received: 21 October 2025; Accepted: 17 December 2025;

Published: 07 January 2026.

Edited by:

Imran Khan, COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, PakistanReviewed by:

Yuening Zhang, University of Oklahoma University College, United StatesSharmila B., Sri Ramakrishna Engineering College, India

Copyright © 2026 Wu, Liu, Yang, Mu, Xu, Sun, Ou, Tian, Chen, Peng and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yanhua Peng, ZW1jX3B5aEBidWFhLmVkdS5jbg==; Jiandong Wang, dmlja3kxOTY4QDE2My5jb20=

Guangmin Wu

Guangmin Wu Zhongyi Liu3

Zhongyi Liu3 Jiahong Sun

Jiahong Sun Yanhua Peng

Yanhua Peng Jiandong Wang

Jiandong Wang