- 1Faculty of Psychology, Southwest University, Beibei, China

- 2Research Institute of Social Development, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, Chengdu, China

In this study, we examined subjective social status (SSS) and self-esteem as potential mediators between the association of psychological suzhi and problem behaviors in a sample of 1271 Chinese adolescents (44.5% male, grades 7–12). The results showed that SSS and self-esteem were fully mediating the relationship between psychological suzhi and problem behaviors. Moreover, the indirect effect was stronger via self-esteem than via SSS. These findings perhaps provide insight into the preliminary effect that SSS and self-esteem underlie psychological suzhi’s effect on adolescents’ problem behaviors, and also are important in helping school-teachers and administrators to develop a better understanding of problem behaviors in their schools as a pre-requisite to the development of more effective behaviors management practices from the perspective of psychological suzhi. Implications and limitations in the present study have also been discussed.

Introduction

For adolescents, problem behaviors refer to the harmful behaviors to their life, physical, and mental health (e.g., fighting, smoking, and alcohol use; DiClemente et al., 1996; Zhu et al., 2016). Problem behaviors have a great impact on the physical and mental health of adolescents (Karaman, 2013), for example, the failure model theory suggested that the problem behaviors precede depression, which in turn lead to depression (Capaldi, 1992; Capaldi and Stoolmiller, 1999). Therefore, in order to provide theoretical guidance for reducing and solving problem behaviors among adolescents, research needs to examine factors predicting and underlying problem behaviors. Although extensive research had examined problem behaviors, but no research had examined if psychological suzhi affects problem behaviors in adolescents during middle school stage, or aimed at identifying a mechanism underlying such an effect.

Psychological suzhi is a native academic conception first proposed by Chinese scholars within the context of quality-oriented education (Zhang et al., 2000; Zhang, 2003, 2012). As a Chinese-originated conception, there is no corresponding conception in the Western psychology academia. In Chinese psychology domain, Psychological suzhi had also been translated as mental quality or psychological quality. However, the word quality cannot cover the whole meaning of suzhi, and this is the reason why it is coined psychological suzhi. Although psychological suzhi is originated in China, it shares common connotations with traditional conceptions in western psychology. For example, psychological suzhi focuses on individual’s positive and initiative psychological development and emphasizes individual’s adaptation toward environment, which is consistent with the proposal of positive psychology in western psychology (Zhang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2015). Psychological suzhi is a concept of Chinese positive psychology from a certain point of view, which has gained acceptance and recognition in Western academia and been collected in the Handbook of Positive Psychology in Schools (2nd edition), an international authoritative reference book (Furlong et al., 2014).

Psychological suzhi is a kind of comprehensive quality, it is defined as a mental quality characterized by being steady (for a certain period of time remain unchanged), essential (fundamental, throughout the development of the individual), and implicit (an intangible mental activity that cannot be directly observed, measured, or recorded by the outside), which has a derivative function related with individuals’ developmental, adaptive, and creative behaviors and a multi-level self-organized system that involves steady implicit mental qualities (content elements, include cognitive quality and individuality) and explicit adaptive (functional value, include adaptability) behaviors (Zhang et al., 2000, 2011; Zhang, 2003, 2012). Moreover, empirical research has supported the theoretical consideration that psychological suzhi has three dimensions: cognitive quality, individuality, and adaptability. As the most basic component of psychological sushi, cognitive quality is directly involved in individuals’ cognition of objects. Individuality is not directly involved in individuals’ cognition of objects, but reflected in individuals’ actions toward objects. Individuality is related to the concept of personality and has a motivating and moderating function during cognition, which is the core component of psychological suzhi. Adaptability is a reliable indicator of the other two dimensions’ activity in various social environments and governs individuals’ ability to achieve consistence between themselves and the environment by changing themselves or the environment during socialization. Adaptability is also a comprehensive reflection of cognitive quality and individuality in individual’s adaptation–development–creative behavior (or explicit behavioral habit). The three basic dimensions of psychological suzhi are interrelated and differentiated, which constitute the core elements of psychological suzhi (Zhang et al., 2000, 2011; Zhang, 2003).

Psychological suzhi has certain stability, it can also be changed to a certain extent under certain conditions and after a certain period of time, especially for children and adolescents, in other words, psychological suzhi is not only a stable mental quality, but also plastic, whereas mental health is a favorable and positive psychological state according to theoretical models of psychological suzhi’s relationship with mental health (Zhang et al., 2011; Zhang and Wang, 2012). Psychological suzhi directly predicts individuals’ mental health, and mental health indicates sound psychological sushi. The relationship between psychological suzhi and mental health is just like the relationship between “essence” and “surface,” that is to say, the psychological suzhi of adolescents is the core of their psychological structure and the basis of their mental activity (play a dominant role), and mental health is the state layer of their psychological structure (surface or explicit layer), which reflects the state of psychological suzhi (surface) (Zhang et al., 2011; Zhang and Wang, 2012). Generally, individuals with high level of psychological suzhi seldom have mental health problems. In contrast, individuals with low level of psychological suzhi are more likely to suffer from mental disturbances. Mental health not only has its external state or symptoms, but also its intrinsic and endogenous factors (Wang and Zhang, 2011). The essence of mental health is good psychological suzhi, good adaptation, and its behaviors are the external manifestations of mental health (Shen and Ma, 2004). The key to mental health education is to improve the students’ psychological suzhi. The cultivation of adolescents’ perfect psychological suzhi is one of the basic ways to solve the psychological problems of adolescents (Lin, 2000; Zhang, 2008). For example, psychological suzhi significantly negatively predicted depression in children and adolescents from previous empirical researches (Hu and Zhang, 2015; Su and Zhang, 2015).

Problem behaviors is defined as the abnormal behaviors of individuals that hinder their social adaptation by Chinese scholars (Lin et al., 2005), which matches the function of psychological suzhi according to the concept and structure of psychological quality (Zhang et al., 2000, 2011; Zhang, 2003). Good adaptation and its behaviors (e.g., adapt to and integrate into the social environment effectively) are the external manifestations of mental health (Shen and Ma, 2004), which means that problem behaviors are the external manifestations of mental health. Besides, research had proved that psychological suzhi significantly negatively predicted problem behaviors in children (Wu et al., 2015). So we predicted that psychological suzhi would be negatively correlated with adolescents’ problem behaviors. However, there was no research has examined if psychological suzhi affects problem behaviors in adolescents. Therefore, our first purpose of this study was to test if psychological suzhi affects problem behaviors in adolescents. We hypothesized that psychological suzhi’s relationship with problem behaviors and mental health would be similar. Psychological suzhi is likely to predict reduced problem behaviors in adolescents, then the mature interventions (e.g., the level of adolescents’ psychological suzhi can be raised through the intervention of parent–child relationship) that could help children and adolescents to cultivate and improve their psychological suzhi would be used to reduce and solve adolescent’s problem behaviors (Zhang et al., 2011, 2014; Zhang, 2012). Examination of psychological suzhi’s association with problem behaviors may extend the understanding of problem behaviors’ causes and inform new interventions targeting problem behaviors.

The second purpose of this study was to identify a mechanism underlying the effect of psychological suzhi which affects problem behaviors in adolescents. Researchers have been doing a lot of studies on the influencing factors of problem behaviors. Among these factors, subjective social status (SSS) may be an important factor of concern. Subjective social status is defined as the individual’s subjective perception and belief of his or her social class (Singh-Manoux et al., 2003). In some previous research, adolescents with a high social status would prefer to exclude others and had more aggression problem behaviors (Cillessen and Mayeux, 2004; Ahn et al., 2010). However, compared to social status, SSS may more accurately capture the consequential aspects of social status (Goodman et al., 2003). In addition, SSS was closely related to the physical and mental health of people of all ages, and the scores of anxiety, depression, various somatic diseases, and dangerous behaviors were lower in high level SSS individuals (Hu et al., 2012), psychological suzhi could positively and significantly predict adolescents’ SSS (Liu et al., 2017). Therefore, psychological suzhi may be correlated with adolescents’ SSS, and we predicted that SSS importantly mediates the relationship between psychological suzhi and adolescents’ problem behaviors.

Self-esteem is another important factor of concern that influences problem behaviors. Self-esteem refers to the individual’s positive evaluation of self-worth and related experience gained in the process of social comparison, which is an affirmative or negative evaluation of oneself and one’s own possession, indicating the extent to which the individual believes that he or she is important, capable, and valuable (Coopersmith, 1967). According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory, self-esteem embodies the individual’s need for respect and belongs to the individual’s advanced needs. Moreover, when the individual’s respect needs to be met, it will make people full of confidence in themselves, to experience the meaning and value of their own lives (Huitt, 2004). On the other hand, adolescence is the “mighty storm” of life developmental period. With the rapid changes in physiology, adolescents’ psychology has undergone tremendous changes. They desire to get respect from parents, teachers, and classmates, and are also eager to get their approval according to the psychological development of adolescents. There is no doubt that high level of self-esteem contributes to the physical and mental health of adolescents (Orth and Robins, 2014). Terror management theory and its anxiety-buffer hypothesis suggest that self-esteem is an “anxiety-buffer,” which the self-regulation mechanism of self-esteem provided the elastic space could ease anxiety, individuals with high level self-esteem are less likely to develop anxious moods and are less prone to anxiety-related behaviors, while low level self-esteem individuals are more prone to anxiety, anxiety-related behaviors, and social adjustment difficulties (Greenberg et al., 1992; Harmon-Jones et al., 1997; Lei and Zhang, 2003). Self-esteem is the core element of mental health (Yang and Zhang, 2003), it could effectively predict adolescents’ well-being and depression (Furnham and Cheng, 2000; Cheng and Furnham, 2003). High level of self-esteem was found to be associated with reduced mental health symptoms in adolescents (Qian and Xiao, 1998). Psychological suzhi significantly positively predicted adolescents’ self-esteem (Liu et al., 2016). Therefore, we predicted that self-esteem importantly mediates the relationship between psychological suzhi and adolescents’ problem behaviors.

Based on the literature review, the current study first attempted to explore the relationships between psychological suzhi, SSS, self-esteem, and problem behaviors in Chinese adolescents, and subsequently attempted to examine the psychological mechanisms that account for these associations. Thus, we hypothesized that:

H1: psychological suzhi would be positively associated with adolescents’ SSS and self-esteem.

H2: SSS and self-esteem would be negatively associated with adolescents’ problem behaviors.

H3: SSS and self-esteem would mediate the association between psychological suzhi and problem behaviors.

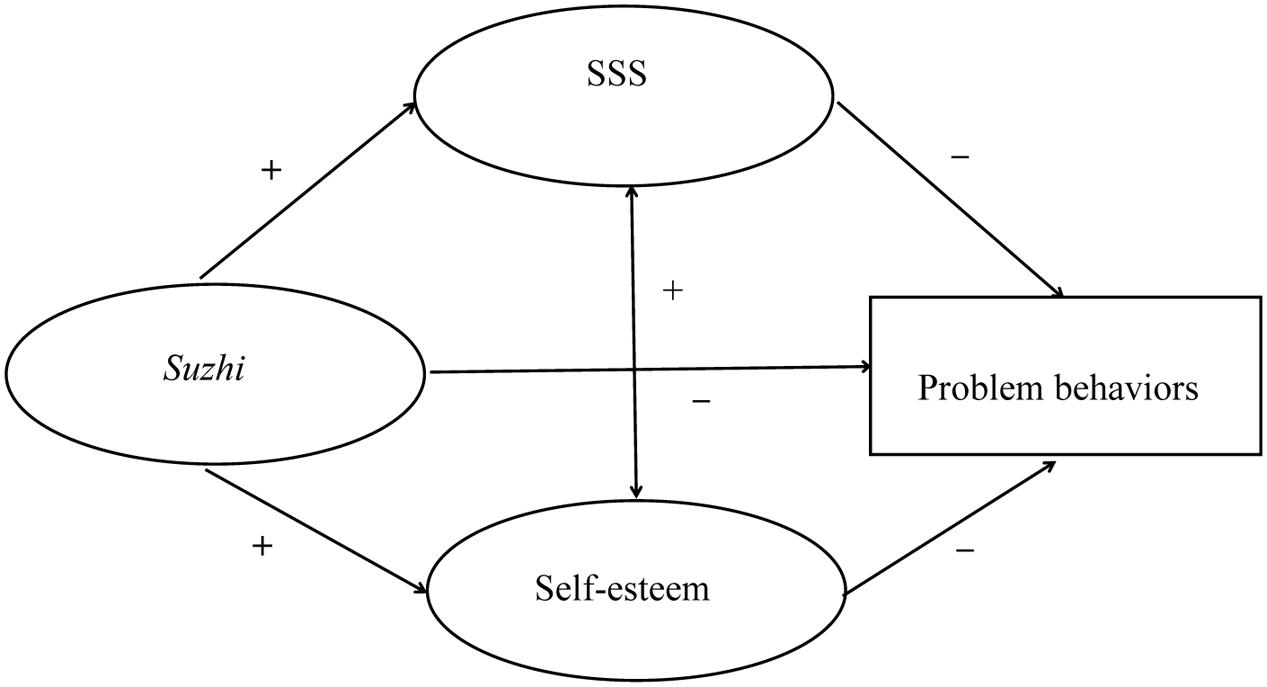

A detailed model of the hypothesized mediator role of SSS and self-esteem in the relationship between psychological suzhi and problem behaviors is presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Model of the hypothesized mediator role of SSS and self-esteem in the relationship 164 between psychological suzhi and problem behaviors.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The Research Ethics Committee of Southwest University approved the study. The participants were 1271 adolescents recruited from three middle and high schools that include middle and high school students in Chongqing, China. Participants were aged 15.13 ± 1.84 years ranged from 11 to 19 years old (only 2 participants were 11 years old; 85 participants were 12 years old; 1161 participants were 13–18 years old; and 23 participants were 19 years old). Among them, 215 were in seventh grade, 209 were in eighth grade, 222 were in ninth grade, 209 were in tenth grade, 221 were in eleventh grade, and 195 were in twelfth grade. There were 575 boys and 696 girls. Participants were all of Han ethnicity.

We obtained both written and informed consent from all participants and their parents. Participants completed a battery of paper-based questionnaires, including the Psychological Suzhi Questionnaire for Middle School Students (PSMQ), the Subjective Social Status Questionnaire (SSSQC), the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (RSES), and the Chinese version of Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Ch-SDQ). Participants completed the battery of questionnaires in their respective classrooms in 30 min.

Measures

Psychological Suzhi

We examined psychological suzhi using the PSMQ (Hu et al., 2017). This questionnaire was developed and validated based on the bi-factor model (Reise et al., 2013; Vecchione et al., 2014), each item or dimension is independent and contributes to overall psychological suzhi. The questionnaire includes 24 items (each dimension includes eight items) examining the following dimensions of psychological suzhi: cognitive quality, individuality, and adaptability (example items from each dimension: I am good at linking old and new knowledge to study, I usually do my own thing by myself, and I often can effectively resolve the embarrassment, respectively), and it is suitable to use for adolescents in the Chinese school environment. Participants indicated their responses to each item on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree. Scores range from 24 to 120, higher scores indicate greater psychological suzhi. Psychological Suzhi Questionnaire for Middle School Students has good internal consistency reliability for the total scale (α = 0.91; Hu et al., 2017). In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha of total scale was 0.91, and the total score was used.

Subjective Social Status

We examined SSS using the SSSQC for College Students (Cheng et al., 2015). The SSSQC is a single-factor construct that contains seven items examining the following topics: academic achievement, family conditions, popularity, social practice ability, talent level, emotional state, and image temperament. The SSSQC uses a 10-rung “ladder” to measure SSS: for each item, participants indicate their position on the ladder. Higher positions indicate greater SSS. For scoring, each rung of the ladder was assigned a numerical value corresponding to its height (i.e., the highest and lowest rungs were coded as 10 and 1, respectively). In the present study, the SSSQC showed that good internal consistency reliability was α = 0.87, and the total score was used.

Self-esteem

We examined self-esteem using the RSES (Rosenberg, 1986). The RSES contains 10 items (example item: I have a positive attitude toward myself, respectively). Participants indicated their responses to each item on a 4-point rating scale from 1 = not at all to 4 = very much. Scores range from 10 to 40, higher scores indicate greater self-esteem. The RSES has been widely used to test self-esteem and has shown good validity and reliability (Wang et al., 1999). However, due to the cultural differences and controversies between the Chinese and Western cultures in item 8 (I hope I can win more respect for myself), Chinese subjects tend to choose very much, this study adopts the practice of Tian (2006), and we deleted it. In the present study, the RSES’ internal consistency reliability was α = 0.81 for the total scale included nine items, and the total score was used.

Problem Behaviors

We examined problem behaviors using the Ch-SDQ (Dai, 2010) translated and revised from Goodman (2001). The SDQ was used to test problem behaviors contains 20 items examining the following four dimensions of problem behaviors: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems with five items for each (example items from each dimension: I often have a headache, stomachache or bad health, I usually do things according to the orders, I’ll think about it before I do something, and I have one or a few good friends, respectively). Participants indicated their responses to each item on a 3-point rating scale from 0 = not true to 2 = certainly true. The self-reported Chinese SDQ has proven reliable and valid in previous studies in Chinese adolescents (Zhao et al., 2013). Higher scores on the SDQ indicate more problem behaviors. In the present study, the SDQ’s internal consistency reliability was 0.70, and the total score was used.

Data Analyses

Descriptive analysis was conducted with the variables of interest for the total sample. Then, SEM was carried out to test if SSS or self-esteem mediates the relationship between psychological suzhi and problem behaviors (Figure 1). Mplus 7.0 was used to evaluate the hypothetical model’s data fit (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2012). Missing data were handled using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) procedure. SEM was performed using the robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimator to account for identified data non-normality. Indirect effects were tested using bootstrapping procedures (Preacher and Hayes, 2008). In order to control for possible inflated measurement errors resulting from multiple items examining the latent variables of psychological suzhi, SSS and self-esteem in the present study, we adapted random assignment (Matsunaga, 2008) to create separate item parcels for variables of SSS and self-esteem that because they are single-dimensional variables, and adapted internal-consistency approach (Bandalos, 2002) to create separate item parcels for psychological suzhi according to its multi-dimensional structure. The number of items in each parcel was roughly equal; therefore, items’ total scores were used to evaluate the hypothetical model’s overall data fit.

Results

Descriptive Statistics of the Variables of Psychological Suzhi, SSS, Self-esteem, and Problem Behaviors

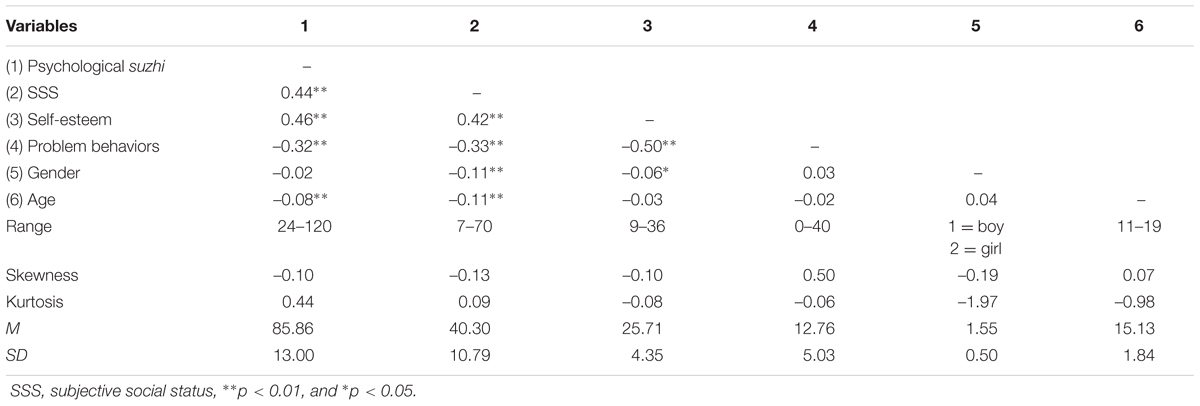

Table 1 summarizes the means and standard deviations, and the correlations between suzhi, SSS, self-esteem, and problem behaviors.

Examining Subjective Social Status and Self-esteem As Potential Mediators of the Link between Psychological Suzhi and Problem Behaviors in Chinese Adolescents

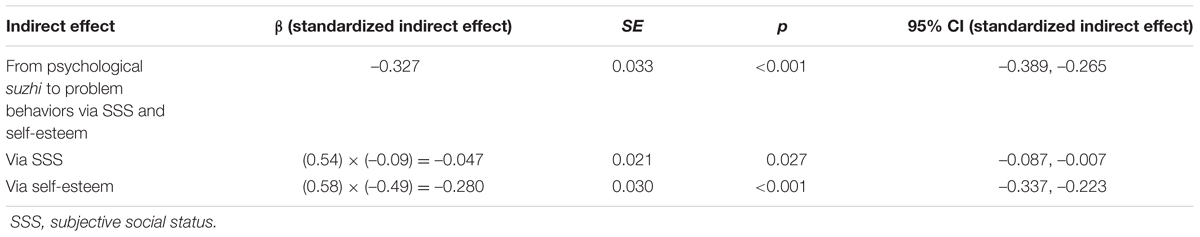

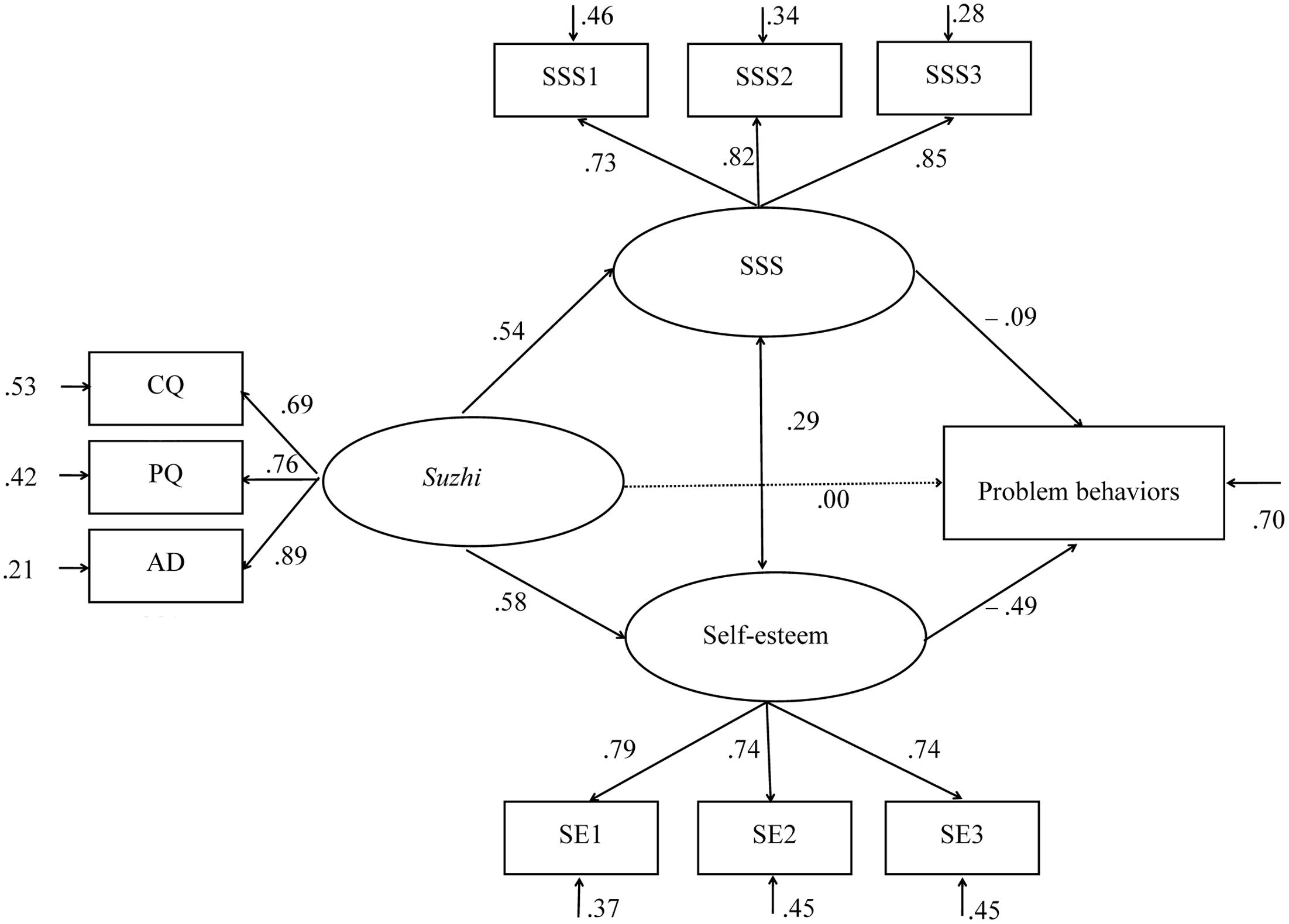

The model examined the associations between psychological suzhi, SSS, self-esteem, and problem behaviors (see Figure 2). Results showed good data fit, χ2 (28, N = 1271) = 146.446 (p < 0.001); CFI = 0.976, TLI = 0.961; RMSEA = 0.058 (90% CI = 0.049, 0.067); and SRMR = 0.034 (Hu and Bentler, 1999). Tests of the indirect effects indicated that SSS and self-esteem fully mediated between psychological suzhi and problem behaviors [β = –0.327, SE = 0.033, p < 0.001, 95% CI = (–0.389, –0.265)], including specific indirect effects of SSS [β = –0.047, SE = 0.021, p < 0.05, 95% CI = (–0.087, –0.007)] and self-esteem [β = –0.280, SE = 0.030, p < 0.001, 95% CI = (–0.337, –0.223); Table 2]. We subsequently used model constraint command of Mplus to create auxiliary variables and used bootstrapping in order to compare the mediation effects (Preacher and Hayes, 2008; Muthén and Muthén, 2010). Psychological suzhi’s indirect correlation with problem behaviors was significantly stronger via self-esteem than via SSS [β = –1.172, SE = 0.201, p < 0.001, 95% CI = (–1.574, –0.792)].

FIGURE 2. Structural equation model with standardized parameters estimates: psychological suzhi and problem behaviors. CQ, cognitive quality; PQ, personality quality; AD, adaptability; SSS, subjective social status, SSS1–SSS3, three parcels of subjective social status; and SE1–SE3, three parcels of self-esteem.

Discussion

As expected, psychological suzhi, SSS, self-esteem, and problem behaviors had significant relationships with each other. Psychological suzhi was significantly positively correlated with adolescents’ SSS and self-esteem, which in turn were negatively correlated with adolescents’ problem behaviors. Moreover, we found that SSS and self-esteem fully mediated psychological suzhi’s effect on problem behaviors, and the indirect effect was significant stronger via self-esteem than via SSS.

Consistent with prior research, psychological suzhi was negatively associated with adolescents’ SSS (Liu et al., 2017). Subjective social status can accurately capture more sensitive aspects of social status than objective indicators and had a greater impact on individuals’ health (Wilkinson, 1999; Goodman et al., 2003). For example, SSS could predict individuals’ well-being and mental health well (Euteneuer, 2014; Haught et al., 2015). Additionally, psychological suzhi significantly positively predicted adolescents’ self-esteem was also consistent with prior research (Liu et al., 2016). Self-esteem is an important factor in the promotion of individuals’ physical and mental health (Orth and Robins, 2014). Therefore, as the core element of mental health (Yang and Zhang, 2003), psychological suzhi could effectively predict adolescents’ well-being and depression (Furnham and Cheng, 2000; Cheng and Furnham, 2003). The results showed that psychological suzhi was significantly positively correlated with adolescents’ SSS and self-esteem, which supports our Hypothesis 1. Both of SSS and self-esteem were positive predictor or core element of mental health that could be significantly positively predicted by psychological suzhi, which support and verify the models of suzhi’s relationship with mental health (Zhang et al., 2011; Zhang and Wang, 2012). This result indicates us that improving adolescents’ psychological suzhi and thereby improving their SSS and self-esteem may promote adolescents’ development of good mental health. Moreover, the current results are preliminary and should inform future longitudinal or experimental studies.

Subjective social status and self-esteem were significantly negatively correlated with adolescents’ problem behaviors, which supports Hypothesis 2. Problem behaviors are generally divided into externalizing problem behaviors (such as aggression and alcohol abuse) and internalizing problem behaviors (such as anxiety and depression) (Achenbach, 1991; Barber et al., 1994). Subjective social status’ significant positive prediction of adolescents’ problem behaviors supports Hu et al. (2012) that higher SSS was closely related to individual’s lower anxiety and depression. Similarly, self-esteem’ significant negative prediction of adolescents’ problem behaviors supports terror management theory and its anxiety-buffer hypothesis. A possible explanation for this result is that as an “anxiety-buffer,” individuals with high level self-esteem are less likely to develop anxious moods and are less prone to anxiety-related behaviors, while low level self-esteem individuals are more prone to anxiety, anxiety-related behaviors, and social adjustment difficulties (Greenberg et al., 1992; Harmon-Jones et al., 1997; Lei and Zhang, 2003), then reduce or eliminate the generation of problem behaviors. The results indicate that individuals perceive higher SSS and self-esteem on their own will help to improve or reduce the level of adolescents’ problem behaviors.

The fact that SSS and self-esteem’ full mediation between psychological suzhi and problem behaviors supports Hypothesis 3, this result was similar to Hu and Zhang (2015), Liu et al. (2016), and Su and Zhang (2015). Possible explanations for this result are as follows. According to the relationship model between psychological suzhi and mental health, the state of mental health must rely on the stability and strong internal psychological suzhi’s support, psychological suzhi can be seen as the intrinsic foundation power of good mental health state to develop, and mental health can be regarded as the psychological suzhi’s explicit performance and behavior signs (Zhang et al., 2011; Zhang and Wang, 2012). Generally, higher psychological suzhi means higher cognitive quality and individuality (i.e., the ability to accurately understand and respond to objects and form reasonable beliefs), and higher adaptability (i.e., the ability to effectively control their behaviors; Hu and Zhang, 2015). In the present study, higher psychological suzhi may lead to better internal regulation to achieve higher SSS and self-esteem, and further affects adolescents’ problem behaviors. This indicates that it is an effective way to guarantee adolescents’ mental health (i.e., SSS, self-esteem, and problem behaviors) through cultivating adolescents’ sound psychological suzhi with the following mature methods and implementary strategies such as multimedia aided mode and implementation strategy, home-school cooperation mode and implementation strategy, and aesthetic nurturing mode and implementing strategy (Zhang, 2012; Zhang et al., 2014).

Moreover, we found that psychological suzhi’s indirect correlation with problem behaviors was significantly stronger via self-esteem than via SSS. Problem behaviors were more strongly correlated with self-esteem than SSS, and self-esteem and SSS were equally correlated with psychological suzhi. Possible explanations for this result may be as follows. For adolescence, they desire to get respect from their parents, teachers, and students, their own level of self-esteem also will rise and play an important role. For example, adolescents with high level of self-esteem tend to take the initiative to communicate with others, are easy to get the goodwill of others, and more likely to have good interpersonal relationships (Baumeister et al., 2003). Compared to self-esteem, SSS played a secondary role in adolescence, but played an important role in the upcoming contact with the society in college students (Chen et al., 2014). Therefore, psychological suzhi’s indirect effect on problem behaviors via self-esteem may exceed that of SSS.

The findings of the present study have important theoretical and practical implications. Whether it is psychological suzhi, or SSS and self-esteem, they all serve as significant predictors of problem behaviors and can thus be used as important tools to reduce the most frequent and harmful problem behaviors. Thus, when designing courses or interventions for reducing problem behaviors, researchers and educators should also focus on adolescents’ psychological suzhi, SSS, and self-esteem. Psychological suzhi affects adolescents’ problem behaviors via SSS and self-esteem, which extend the ways for interventions targeting problem behaviors in adolescents. Adolescence is a key stage for psychological suzhi and problem behaviors development. Teachers and educators should provide more related courses, activities to develop and improve adolescents’ psychological suzhi, SSS, and self-esteem, and then may reduce or eliminate problem behaviors among adolescents. According to the findings of the parallel mediating role of SSS and self-esteem between psychological suzhi and problem behaviors, first and most importantly, we should guide and facilitate adolescents’ psychological suzhi in their daily study life. Therefore, future research should test strategies for cultivating psychological suzhi in order to reduce or eliminate problem behaviors in adolescents.

Despite the theoretical and practical implications are discussed above, the present study has several possible limitations as follows. Firstly, although we used anonymous methods and used different self-report methods and formats to measure psychological suzhi, SSS, self-esteem, and problem behaviors, these methods may have improved the study’s internal validity and avoided or reduced common-method covariance. The one-sided self-report answers may have affected the level of the variables. To test the accuracy of the mediating model, future research should attempt to overcome this limitation by using other-report methods. Secondly, we used a cross-sectional design that cannot test possible causal relationships between the four variables. Therefore, future research should use an experimental or longitudinal design to test such possible relations. Thirdly, as the current study was conducted with a sample of students from three middle schools in China, whether the findings discussed above could be generalized to other middle schools’ students remains to be determined.

Conclusion

This study expands the understanding of the mechanisms underlying suzhi’s effect on problem behaviors by the mediating roles of SSS and self-esteem, and its findings are novel and insightful, both theoretically and practically. This study not only clarifies that adolescents’ psychological suzhi negatively predicts their problem behaviors, but also supports the roles of their SSS and self-esteem as mediators in this relationship. Besides, self-esteem has a stronger indirect effect on problem behaviors than SSS does. In short, these findings suggest that SSS and self-esteem underlie psychological suzhi’s effect on adolescents’ problem behaviors. To this end, the current study offers an important foundation for future work.

Ethics Statement

The Research Ethics Committee of Southwest University approved the study. Prior to testing, we obtained both written and informed consent from all participants and their parents. Willing participants subsequently provided spoken consent.

Author Contributions

On the basis of reading the relevant literature, GL put forward the research questions and the solution of this research, and the whole research process is responsible for the research plan of this research, for example, to determine the research object, clear research methods, contact the subjects to test, data entry, and so on, and finally to collect the data back analysis to verify the assumptions made by this study, and is responsible for the study of the full text of the writing work. At the same time, according to the teachers’ and cooperative researchers’ recommendations and comments on the draft of the paper have been amended to formally form the final submission manuscript. DZ was mainly responsible for the supervision and guidance of the entire research process, timely correct the wrong ideas and direction, and the smooth completion of the entire study plays an important role. DZ was also mainly responsible for modifying and providing guidance to this paper. YP was mainly responsible for modifying and providing guidance to this paper, played an important role in the successful writing of the paper. YM was mainly responsible for modifying and providing guidance to this paper, also played an important role. XL was mainly responsible for language polish.

Funding

This work was supported by the “2011 Plan” project of the Basic Education Quality Monitoring Collaborative Innovation Center of China: Mental Health Assessment Tool for Primary and Secondary School Students and Development Diagnostic Research (2014-06-007-01).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer KG and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation.

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Integrative Guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont.

Ahn, H. J., Garandeau, C. F., and Rodkin, P. C. (2010). Effects of classroom embeddedness and density on the social status of aggressive and victimized children. J. Early Adolesc. 30, 76–101. doi: 10.1177/0272431609350922

Bandalos, D. L. (2002). The effects of item parceling on goodness-of-fit and parameter estimate bias in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Modeling 9, 78–102. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0901_5

Barber, B. K., Olsen, J. E., and Shagle, S. C. (1994). Associations between parental psychological and behavioral control and youth internalized and externalized behaviors. Child Dev. 65, 1120–1136. doi: 10.2307/1131309

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., and Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 4, 1–44. doi: 10.1111/1529-1006.01431

Capaldi, D. M. (1992). Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: II. A 2-year follow-up at Grade 8. Dev. Psychopathol. 4, 125–144. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2007.07.004

Capaldi, D. M., and Stoolmiller, M. (1999). Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: III. Prediction to young-adult adjustment. Dev. Psychopathol. 11, 59–84. doi: 10.1017/S0954579499001959

Chen, Y. H., Cheng, G., Guan, Y. S., and Zhang, D. J. (2014). The mediating effects of subjective social status on the relations between self-esteem and socioeconomic status for college students. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 30, 594–600.

Cheng, G., Zhang, D. J., Guan, Y. S., and Chen, Y. H. (2015). On composition of college students’ subjective social status indexes and their characteristics. J. Southwest Univ. 6, 156–162.

Cheng, H., and Furnham, A. (2003). Personality, self-esteem, and demographic predictions of happiness and depression. Pers. Individ. Dif. 34, 921–942. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00078-8

Cillessen, A. H., and Mayeux, L. (2004). From censure to reinforcement: developmental changes in the association between aggression and social status. Child Dev. 75, 147–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00660.x

Coopersmith, S. (1967). The Antecedents of Self-Esteem. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Dai, X. Y. (2010). Common Psychological Assessment Handbook. Beijing: Beijing People’s Medical Publishing House.

DiClemente, R. J., Hansen, W. B., and Ponton, L. E. (eds). (1996). “Adolescents at risk,” in Handbook of Adolescent Health Risk Behavior, (New York, NY: Springer), 1–4. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-0203-0_1

Euteneuer, F. (2014). Subjective social status and health. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 27, 337–343. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000083

Furlong, M. J., Gilman, R., and Huebner, E. S. (eds) (2014). Handbook of Positive Psychology in Schools, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Furnham, A., and Cheng, H. (2000). Perceived parental behaviour, self-esteem and happiness. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 35, 463–470. doi: 10.1007/s001270050265

Goodman, E., Adler, N. E., Daniels, S. R., Morrison, J. A., Slap, G. B., and Dolan, L. M. (2003). Impact of objective and subjective social status on obesity in a biracial cohort of adolescents. Obes. Res. 11, 1018–1026. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.140

Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 40, 1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015

Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Pyszczynski, T., Rosenblatt, A., Burling, J., Lyon, D., et al. (1992). Why do people need self-esteem? Converging evidence that self-esteem serves an anxiety-buffering function. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 63, 913–922. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.63.6.913

Harmon-Jones, E., Simon, L., Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., and McGregor, H. (1997). Terror management theory and self-esteem: evidence that increased self-esteem reduced mortality salience effects. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 72, 24–36. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.24

Haught, H. M., Rose, J., Geers, A., and Brown, J. A. (2015). Subjective social status and well-being: the role of referent abstraction. J. Soc. Psychol. 155, 356–369. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2015.1015476

Hu, L. T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Hu, M. L., Wang, M. C., Cai, L., Zhu, X. Z., and Yao, S. Q. (2012). Development of subjective socioeconomic status scale for Chinese adolescents. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 20, 155–157.

Hu, T. Q., and Zhang, D. J. (2015). The relationship between psychological suzhi and depression of middle school students: the mediating role of self service attribution bias. J. Southwest Univ. 6, 13.

Hu, T. Q., Zhang, D. J., and Cheng, G. (2017). Revision of the psychological suzhi questionnaire of the middle school students (simplified version) and the test of the reliability and validity. J. Southwest Univ. 10, 120–126.

Huitt, W. (2004). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University.

Karaman, N. G. (2013). Predicting the problem behavior in adolescents. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 52, 137–154.

Lei, L., and Zhang, L. (2003). The Psychological Development of Adolescents. Beijing: Peking University Press, 41–46.

Lin, C. D. (2000). The key to mental health education is to improve students’ psychological quality. Ideol. Polit. Teach. 34–35.

Lin, C. D., Yang, Z. L., and Huang, X. T. (2005). Dictionary of Psychology. Shanghai: Shanghai Education Press, 1317.

Liu, G., Zhang, D., Pan, Y., Hu, T., He, N., Chen, W., et al. (2017). Self-concept clarity and subjective social status as mediators between psychological suzhi and social anxiety in Chinese adolescents. Pers. Individ. Dif. 108, 40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.11.067

Liu, G. Z., Zhang, D. J., Pan, Y. G., Chen, W. F., and Ma, Y. X. (2016). The relationship between middle school students’ psychological suzhi and peer relationship: the mediating role of self-esteem. Chin. J. Psychol. Sci. 39, 1290–1295.

Matsunaga, M. (2008). Item parceling in structural equation modeling: a primer. Commun. Methods Meas. 2, 260–293. doi: 10.1080/19312450802458935

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus User’s Guide 7th Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén. (2010). Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables: User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Orth, U., and Robins, R. W. (2014). The development of self-esteem. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 23, 381–387. doi: 10.1177/0963721414547414

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.87

Qian, M. Y., and Xiao, G. L. (1998). Self-efficacy, self-esteem and parental rearing styles. Chin. J. Psychol. Sci. 21, 553–555.

Reise, S. P., Scheines, R., Widaman, K. F., and Haviland, M. G. (2013). Multidimensionality and structural coefficient bias in structural equation modeling: a bifactor perspective. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 73, 5–26. doi: 10.1177/0013164412449831

Singh-Manoux, A., Adler, N. E., and Marmot, M. G. (2003). Subjective social status: its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Soc. Sci. Med. 56, 1321–1333. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00131-4

Su, Z. Q., and Zhang, D. J. (2015). The relationship between psychological suzhi and depression of children aged 8-12: the mediating effect of coping styles. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 2, 72–77.

Tian, L. M. (2006). Shortcoming and merits of Chinese version of Rosenberg (1965) Self-Esteem Scale. Psychol. Explor. 26, 88–91.

Vecchione, M., Alessandri, G., Caprara, G. V., and Tisak, J. (2014). Are method effects permanent or ephemeral in nature? The case of the revised life orientation test. Struct. Equ. Model. A 21, 117–130. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2014.859511

Wang, J. L., Zhang, D. J., and Zimmerman, M. A. (2015). Resilience theory and its implications for Chinese adolescents. Psychol. Rep. 117, 354–375. doi: 10.2466/16.17.PR0.117c21z8

Wang, X. D., Wang, X. L., and Ma, H. (1999). Handbook of mental health assessment scale. Chin. Ment. Health J. 13, 31–35.

Wang, X. Q., and Zhang, D. J. (2011). A review on the dual-factor model of mental health and its prospect. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 10, 68–73.

Wilkinson, R. G. (1999). Health, hierarchy, and social anxiety. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 896, 48–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08104.x

Wu, L., Zhang, D., Cheng, G., Hu, T., and Rost, D. H. (2015). Parental emotional warmth and psychological Suzhi as mediators between socioeconomic status and problem behaviours in Chinese children. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 59, 132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.09.019

Yang, L. Z., and Zhang, L. H. (2003). On psychological significance of self-esteem. Psychol. Explor. 23, 10–12.

Zhang, D. J. (2008). Integrated research on the mental health and its education among Chinese adolescents. J. Southwest Univ. 34, 22–28.

Zhang, D. J. (2012). Integrating adolescents’ mental health and psychological suzhi cultivation. Chin. J. Psychol. Sci. 35, 530–536.

Zhang, D. J., Feng, Z. Z., Guo, C., and Chen, X. (2000). Problems on research of children psychological suzhi. J. Southwest China Norm. Univ. 26, 56–62.

Zhang, D. J., Wang, J. L., and Yu, L. (2011). Methods and Implementation Strategies on Cultivating Children’s Psychological Suzhi. New York, NY: Nova Science.

Zhang, D. J., and Wang, X. Q. (2012). An analysis of the relationship between mental health and psychological suzhi: from the perspective of connotation and structure. J. Southwest Univ. 38, 69–74.

Zhang, D. J., Yu, L., and Wang, J. L. (2014). Psychological Suzhi Training Mode and Implementation Strategy of Students. Beijing: China Science Press.

Zhao, B., Huang, Z., Guo, F., Hu, Y., and Chen, Z. Y. (2013). The agreement of results between parents and self report of strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 28–31.

Keywords: psychological suzhi, problem behaviors, subjective social status, self-esteem, adolescents

Citation: Liu G, Zhang D, Pan Y, Ma Y and Lu X (2017) The Effect of Psychological Suzhi on Problem Behaviors in Chinese Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Subjective Social Status and Self-esteem. Front. Psychol. 8:1490. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01490

Received: 14 March 2017; Accepted: 17 August 2017;

Published: 31 August 2017.

Edited by:

Barbara McCombs, University of Denver, United StatesReviewed by:

Kathy Ellen Green, University of Denver, United StatesRuomeng Zhao, MacPractice, Inc., United States

Copyright © 2017 Liu, Zhang, Pan, Ma and Lu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dajun Zhang, emhhbmdkakBzd3UuZWR1LmNu

Guangzeng Liu

Guangzeng Liu Dajun Zhang

Dajun Zhang Yangu Pan2

Yangu Pan2