- 1English Department, Hainan Medical University, Haikou, China

- 2Department of Postgraduate Studies, Faculty of Education, Languages and Psychology, SEGi University, Kota Damansara, Malaysia

Given the undeniable role of English as a foreign language (EFL) students’ academic motivation and engagement in L2 success, identifying the antecedents of these positive academic behaviors seems essential. Accordingly, many empirical studies have probed into the impact of students’ personal factors on their motivation and engagement. Yet, not much attention has been paid to the role of teachers’ communication behaviors, notably praise. Additionally, no review has been performed in this regard. The present review study intends to address these gaps by explaining teacher praise and its positive outcomes for EFL students’ motivation and engagement. In light of the empirical and theoretical evidence, the role of teacher praise in improving students’ academic motivation and engagement was proved. The paper concludes with some pedagogical implications.

Introduction

Students’ motivation and engagement as two prime instances of positive academic behaviors serve a facilitative function in their learning success (Martin et al., 2017). Accordingly, raising students’ academic motivation and engagement has been among the top priorities of all effective instructors. However, many instructors, notably English as a Foreign Language (EFL) and English as a Second Language (ESL) teachers are still unaware of how to considerably enhance their students’ academic motivation and engagement. In fact, how EFL and ESL students’ academic motivation and engagement can be improved is not widely recognized (Henry and Thorsen, 2018). Students’ academic motivation or motivation to learn generally refers to “their primary impetus for initiating learning as well as the reason for continuing the prolonged and tedious process of learning” (Ushioda, 2008, p. 21). More specifically, conceptualized language learners’ academic motivation as the degree to which they strive to acquire a new language out of a desire to do so and the enjoyment they experienced in the process of learning. Besides, student academic engagement as another example of desirable academic behaviors pertains to “students’ active, goal-directed, flexible, constructive, persistent, focused interactions with the learning environment” (Furrer and Skinner, 2003, p. 149). In the domain of language education, students’ academic engagement refers to their active participation in learning and mastering a new language (Hiver et al., 2021).

As Irvin et al. (2007) noted academic motivation and engagement as two related constructs are of high importance for students’ increased achievement, advancement, and academic success. Concerning the value of student academic motivation in instructional-learning environments, Froiland and Oros (2014) postulated that both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation of pupils can favorably influence their academic performance. In a similar vein, Martin (2013) also stated that the sense of enjoyment that highly motivated students experience in classroom contexts encourages them to enthusiastically pursue different stages of learning. This, in turn, contributes to desirable learning outcomes. In this regard, Howard et al. (2021) also illustrated the importance of motivation by referring to its positive effect on students’ level of perseverance. They articulated that academic motives can empower students to resist the difficulties that they may experience during the learning process.

To shed light on the significance of student academic engagement, Skinner and Pitzer (2012) mentioned that students’ active membership in instructional-learning contexts enables them to gain higher academic grades. Similarly, Finn and Zimmer (2012) submitted that students’ degree of participation in educational contexts is closely related to their academic growth. To them, nothing like active participation in classrooms can facilitate students’ educational advancement. Additionally, Philp and Duchesne (2016) also postulated that students’ academic engagement can remarkably increase the likelihood of their academic success. Drawing on what has been mentioned regarding the centrality of academic motivation and engagement in students’ educational success, investigating the determinants and predictors of these variables seems crucial.

Against this backdrop, numerous studies have inspected the impact of students’ personality traits on their academic motivation (e.g., Komarraju et al., 2009; De Feyter et al., 2012; Hazrati-Viari et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2013; Guo, 2021) and engagement (e.g., Linvill, 2014; Kahu et al., 2015; Qureshi et al., 2016; Rostami et al., 2017). Several studies have also been conducted to examine the effects of teachers’ personality traits on students’ motivation and engagement (e.g., Gibbs and Powell, 2012; Sabet et al., 2018; Khalilzadeh and Khodi, 2021). Additionally, many empirical and theoretical studies have probed into the role of teachers’ positive communication behaviors, including credibility (e.g., Imlawi et al., 2015; Derakhshan, 2021), immediacy (e.g., Dixson et al., 2017; Liu, 2021; Zheng, 2021), and confirmation (e.g., Shen and Croucher, 2018; LaBelle and Johnson, 2020; Gao, 2021), in promoting student academic motivation and engagement. Nonetheless, teacher praise as one of the most influential communication behaviors has received scant attention (Downs, 2017; Caldarella et al., 2021).

The concept of praise generally refers to “verbal or nonverbal actions indicating the positive quality of a behavior over and above the evaluation of accuracy” (Kalis et al., 2007, p. 23). Similarly, teacher praise pertains to any gesture or statement that instructors employ to admire their students’ appropriate and favorable behaviors (Reinke et al., 2008). Jenkins et al. (2015) postulated that teacher praise is a “feasible, nonintrusive classroom strategy” that can be easily utilized by teachers in any instructional-learning environment. As Marchant and Anderson (2012) noted, the verbal or nonverbal action used by teachers to applaud their pupils’ positive behaviors may work as a stimulator, encouraging students to repeat the desired actions. They also suggested that teachers can inspire a feeling of mastery and accomplishment in their pupils by acknowledging their satisfactory behaviors. These positive feelings contribute to increased student motivation (Titsworth, 2000). According to Richard (2012), students’ willingness to participate in classroom activities also improves when instructors praise their academic performance.

Despite the importance of teachers’ verbal and nonverbal admiration in increasing student’ academic motivation and engagement (Marchant and Anderson, 2012; Richard, 2012), a few scholars (Downs, 2017; Caldarella et al., 2021) have studied teacher praise in relation to these positive academic behaviors. Furthermore, no theoretical or systematic review has been carried out in this regard. Thus, to narrow the existing gaps, the current review study aims to provide a detailed description of these variables (i.e., teacher praise, student motivation, and student engagement), their theoretical foundations, and the existing association among them.

Related Literature

Teacher Praise

The term praise comes from a Latin verb, namely “pretiare,” which means “to value highly” (Burnett, 2002, p. 6). This construct is literally defined as “the expression of approval or admiration for one’s behavior or characteristic” (Brophy, 1981, p. 5). In line with this definition, Burnett and Mandel (2010) conceptualized teacher praise as positive verbal or nonverbal actions through which teachers glorify students whenever they perform well. As clearly mentioned in this definition, like other communication behaviors such as immediacy, confirmation, and stroke (Han and Wang, 2021; Xie and Derakhshan, 2021), teacher praise can be both verbal and nonverbal. As Shernoff et al. (2020) noted, verbal praise refers to any positive comments that teachers offer to students due to their desired academic behaviors. Nonverbal praise also pertains to any gestures, including nodding and smiling, teachers use to exalt their pupils. Generally, teacher praise is of two types: “General Praise (GP)” and “Behavior-Specific Praise (BSP)” (Floress et al., 2017). GP means admiring students’ behavior without mentioning which aspects of their performance were acceptable (Duchaine et al., 2011). In contrast, BSP, as the name speaks for itself, entails “approval with an explanation of the appropriate behavior exhibited” (Duchaine et al., 2011, p. 210).

Student Academic Motivation

The concept of motivation is generally conceptualized as a stimulating force that directs human behaviors (Brophy, 1983). Student motivation to learn, also known as academic motivation, is related to their motive “to make certain academic decisions, participate in classroom activities, and persist in pursuing the demanding process of learning” (Dörnyei and Ushioda, 2009, p. 2). Working on different types of student academic motivation, Brophy (1983) divided this construct into two broad categories, namely “state motivation” and “trait motivation.” State motivation refers to “students’ attitude toward a particular course” (Guilloteaux and Dörnyei, 2008, p. 56). Trait motivation, on the other hand, deals with students’ general tendency toward the learning process (Csizér and Dörnyei, 2005). While students’ trait motivation is typically constant during a whole course, their state motivation is open to drastic changes (Trad et al., 2014). As Hiver and Al-Hoorie (2020) mentioned, student state motivation can be dramatically influenced by their viewpoints and attitudes toward their instructors, course content, and learning environment. Similarly, Dörnyei (2020) also posited that how students perceive their teachers’ personal and interpersonal behaviors has a significant impact on their academic motivation. It implies that those teachers who behave appropriately in classroom contexts have a beneficial impact on their students’ state motivation (Cheng and Dörnyei, 2007; Bernaus and Gardner, 2008; Papi and Abdollahzadeh, 2012).

Student Academic Engagement

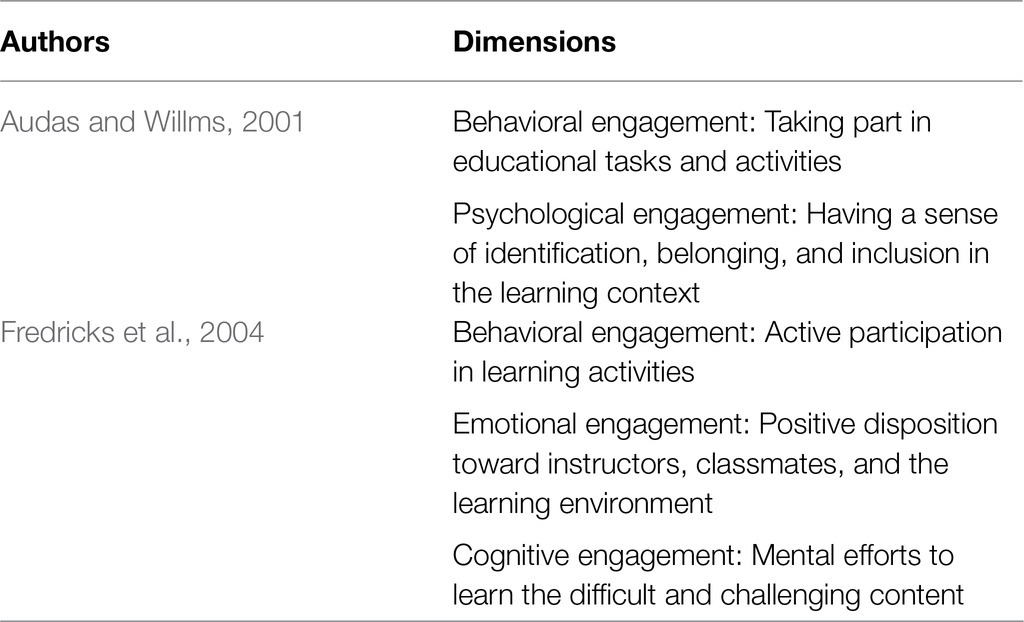

Student engagement, in a general sense, refers to the amount of time, energy, and effort that students willingly dedicate to educational activities (Appleton et al., 2008). Skinner et al. (2009, p. 495) conceptualized this construct as “the quality and quantity of students’ participation or connection with the educational endeavor and hence with activities, values, individuals, aims, and place that comprise it.” Despite the existing controversy regarding the terminology of this concept, many scholars referred to this construct as “student academic engagement” (e.g., Leach and Dolan, 1985; Greenwood et al., 2002; Brint et al., 2008). Other academics named this construct as “school engagement” (Jimerson et al., 2003), “educational engagement” (Wehlage et al., 1989), and “study engagement” (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Similarly, there has been a long debate over the number and types of the components of this construct (Alrashidi et al., 2016). As an instance, Audas and Willms (2001) classified the components of student engagement into two broad categories, whereas Fredricks et al. (2004) divided this construct into three main dimensions (Table 1).

Despite all the aforementioned discrepancies, researchers have come to the conclusion that the construct of academic engagement is multidimensional and covers several aspects, including cognitive, emotional, and behavioral, working together to demonstrate students’ positive attitudes toward the learning process (Hiver et al., 2021).

The Impact of Teacher Praise on EFL Students’ Academic Motivation and Engagement

The impact of teacher praise on EFL students’ level of motivation and engagement can be readily illustrated through “Emotional Response Theory (ERT).” In their theory, Mottet et al. (2006) asserted that the positive communication behaviors, including praise, used by language teachers while instructing may result in learners’ positive responses such as happiness, L2 enjoyment, and pleasure. To them, those language learners who experience a sense of happiness, pleasure, or enjoyment in the learning environment are more motivated to pursue the learning process. Those who are sufficiently motivated tend to actively take part in classroom activities (Martin, 2007; Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2012; Reeve, 2012). In a similar vein, drawing on the positive psychology movement (Dewaele et al., 2019; MacIntyre et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021), Xie and Derakhshan (2021) also illustrated the favorable association between teacher communication behaviors and students’ academic behaviors (e.g., engagement, motivation, etc.). They stated that, through effective communication behaviors, language teachers are able to create a pleasant educational atmosphere, wherein learners enjoy learning a new language. Having a sense of enjoyment is of high importance for students’ increased motivation and engagement (Kulakow and Raufelder, 2020; Pedler et al., 2021). All in all, based on what Mottet et al. (2006) and Xie and Derakhshan (2021) mentioned, teacher praise as an instance of effective communication behavior can considerably influence EFL students’ engagement and motivation.

A number of empirical studies have shed light on the extent to which teacher praise is linked to students’ academic motivation and engagement (Richard, 2012; Downs, 2017; Caldarella et al., 2021). As an instance, Richard (2012) examined the impact of teachers’ verbal and nonverbal praise on students’ engagement. In doing so, a group of American teachers and students took part in this inquiry. Some treatment sessions were run to observe the effects of teacher verbal and nonverbal praise on students’ classroom engagement. The analysis of the obtained data demonstrated that students’ participation in classroom exercises was positively influenced by their teachers’ verbal and nonverbal praise. In another study, Downs (2017) probed into the effects of teacher praise on student’ emotional behaviors, namely motivation and engagement. To this aim, 239 students were invited to attend some treatment session. The results of observations indicated that the verbal and nonverbal praise that teachers provided in treatment sessions favorably affected participants’ motivation and engagement.

Conclusion and Pedagogical Implications

So far, various definitions of student academic motivation, academic engagement, and teacher praise, along with their theoretical foundations, were illustrated. Building upon emotional response theory and the positive psychology movement, the association between these variables was also explained. Additionally, a summary of the previous related studies was provided. Based on what has been reviewed in the current study, it is fair to conclude that teacher praise (verbal or nonverbal) is a strong antecedent of EFL students’ academic motivation and engagement. This finding can be highly beneficial for all EFL teachers who struggle with their students’ insufficient motivation and engagement. As noted by Mottet et al. (2006) and Xie and Derakhshan (2021), through admiring students’ behaviors, teacher can dramatically enhance student’ engagement and motivation to learn. The review’s finding has an important implication for teacher trainers as well. An important reason underlying EFL students’ lack of motivation and engagement is teachers’ disability to praise students’ behaviors (Duchaine et al., 2011). Thus, to improve EFL students’ motivation and engagement, teachers should receive adequate instructions on how to praise their students’ academic performances. Put it simply, teacher trainers should teach EFL instructors all they need to know regarding this positive communication behavior.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This paper is a special subject of Hainan Philosophy and Social Sciences Foreign Language Application Research Base “Study on Cultivation of Intercultural Communication Competence of College Students in Hainan Medical College under the Background of Free Trade Port” (grant no. HNWYJD18-05).

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alrashidi, O., Phan, H. P., and Ngu, B. H. (2016). Academic engagement: an overview of its definitions, dimensions, and major conceptualizations. Int. Educ. Stud. 9, 41–52. doi: 10.5539/ies.v9n12p41

Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., and Furlong, M. J. (2008). Student engagement with school: critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychol. Sch. 45, 369–386. doi: 10.1002/pits.20303

Audas, R., and Willms, J. D. (eds.) (2001). Engagement and Dropping out of School: A Life-Course Perspective. Hull, QC: Human Resources Development Canada.

Bernaus, M., and Gardner, R. C. (2008). Teacher motivation strategies, student perceptions, student motivation, and English achievement. Mod. Lang. J. 92, 387–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2008.00753.x

Brint, S., Cantwell, A. M., and Hanneman, R. A. (2008). The two cultures of undergraduate academic engagement. Res. High. Educ. 49, 383–402. doi: 10.1007/s11162-008-9090-y

Brophy, J. (1981). Teacher praise: a functional analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 51, 5–32. doi: 10.3102/00346543051001005

Brophy, J. (1983). Conceptualizing student motivation. Educ. Psychol. 18, 200–215. doi: 10.1080/00461528309529274

Burnett, P. C. (2002). Teacher praise and feedback and students' perceptions of the classroom environment. Educ. Psychol. 22, 5–16. doi: 10.1080/01443410120101215

Burnett, P. C., and Mandel, V. (2010). Praise and feedback in the primary classroom: teachers' and students' perspectives. Aust. J. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 10, 145–154.

Caldarella, P., Larsen, R. A., Williams, L., Wills, H. P., and Wehby, J. H. (2021). “Stop doing that”: effects of teacher reprimands on student disruptive behavior and engagement. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 23, 163–173. doi: 10.1177/1098300720935101

Cheng, H. F., and Dörnyei, Z. (2007). The use of motivational strategies in language instruction: the case of EFL teaching in Taiwan. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 1, 153–174. doi: 10.2167/illt048.0

Csizér, K., and Dörnyei, Z. (2005). Language learners’ motivational profiles and their motivated learning behavior. Lang. Learn. 55, 613–659. doi: 10.1111/j.0023-8333.2005.00319.x

De Feyter, T., Caers, R., Vigna, C., and Berings, D. (2012). Unraveling the impact of the big five personality traits on academic performance: the moderating and mediating effects of self-efficacy and academic motivation. Learn. Individ. Differ. 22, 439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2012.03.013

Derakhshan, A. (2021). The predictability of Turkman students’ academic engagement through Persian language teachers’ nonverbal immediacy and credibility. J. Teac. Persian Speak. Other Lang. 10, 3–26. doi: 10.30479/jtpsol.2021.14654.1506

Dewaele, J. M., Chen, X., Padilla, A. M., and Lake, J. (2019). The flowering of positive psychology in foreign language teaching and acquisition research. Front. Psychol. 10:2128. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02128

Dixson, M. D., Greenwell, M. R., Rogers-Stacy, C., Weister, T., and Lauer, S. (2017). Nonverbal immediacy behaviors and online student engagement: bringing past instructional research into the present virtual classroom. Commun. Educ. 66, 37–53. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2016.1209222

Dörnyei, Z. (2020). Innovations and Challenges in Language Learning Motivation. New York, NY: Routledge.

Dörnyei, Z., and Ushioda, E. (2009). “Motivation, language identities and the L2 self: a theoretical overview,” in Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self. eds. Z. Dörnyei and E. Ushioda (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 1–8.

Downs, K. R. (2017). Effects of teacher praise and reprimand rates on classroom engagement and disruptions of elementary students at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders. Doctoral Dissertation. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University.

Duchaine, E. L., Jolivette, K., and Fredrick, L. D. (2011). The effect of teacher coaching with performance feedback on behavior-specific praise in inclusion classrooms. Educ. Treat. Child. 34, 209–227. doi: 10.1353/etc.2011.0009

Finn, J. D., and Zimmer, K. S. (2012). “Student engagement: what is it? Why does it matter?,” in Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. eds. S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, and C. Wylie (Boston, MA: Springer), 97–131.

Floress, M. T., Beschta, S. L., Meyer, K. L., and Reinke, W. M. (2017). Praise research trends and future directions: characteristics and teacher training. Behav. Disord. 43, 227–243. doi: 10.1177/0198742917704648

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., and Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 74, 59–109. doi: 10.3102/00346543074001059

Froiland, J. M., and Oros, E. (2014). Intrinsic motivation, perceived competence and classroom engagement as longitudinal predictors of adolescent reading achievement. Educ. Psychol. 34, 119–132. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2013.822964

Furrer, C., and Skinner, E. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children's academic engagement and performance. J. Educ. Psychol. 95, 148–162. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.148

Gao, Y. (2021). Towards the role of language teacher confirmation and stroke in EFL/ESL students’ motivation and academic engagement: a theoretical review. Front. Psychol. 12:723432. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.723432

Gibbs, S., and Powell, B. (2012). Teacher efficacy and pupil behaviour: the structure of teachers’ individual and collective beliefs and their relationship with numbers of pupils excluded from school. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 82, 564–584. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02046.x

Greenwood, C. R., Horton, B. T., and Utley, C. A. (2002). Academic engagement: current perspectives on research and practice. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 31, 328–349. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2002.12086159

Guilloteaux, M. J., and Dörnyei, Z. (2008). Motivating language learners: a classroom-oriented investigation of the effects of motivational strategies on student motivation. TESOL Q. 42, 55–77. doi: 10.1002/j.1545-7249.2008.tb00207.x

Guo, Y. (2021). Exploring the dynamic interplay between foreign language enjoyment and learner engagement with regard to EFL achievement and absenteeism: a sequential mixed methods study. Front. Psychol. 12:575. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.679575

Han, Y., and Wang, Y. (2021). Investigating the correlation among Chinese EFL teachers’ self-efficacy, reflection, and work engagement. Front. Psychol. 12:763234. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.763234

Hazrati-Viari, A., Rad, A. T., and Torabi, S. S. (2012). The effect of personality traits on academic performance: the mediating role of academic motivation. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 32, 367–371. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.055

Henry, A., and Thorsen, C. (2018). Teacher–student relationships and L2 motivation. Mod. Lang. J. 102, 218–241. doi: 10.1111/modl.12446

Hiver, P., and Al-Hoorie, A. H. (2020). Reexamining the role of vision in second language motivation: a preregistered conceptual replication of you, Dörnyei, and Csizér (2016). Lang. Learn. 70, 48–102. doi: 10.1111/lang.12371

Hiver, P., Al-Hoorie, A. H., Vitta, J. P., and Wu, J. (2021). Engagement in language learning: a systematic review of 20 years of research methods and definitions. Lang. Teach. Res. doi: 10.1177/13621688211001289

Howard, J. L., Bureau, J., Guay, F., Chong, J. X., and Ryan, R. M. (2021). Student motivation and associated outcomes: a meta-analysis from self-determination theory. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. doi: 10.1177/1745691620966789

Imlawi, J., Gregg, D., and Karimi, J. (2015). Student engagement in course-based social networks: the impact of instructor credibility and use of communication. Comput. Educ. 88, 84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.04.015

Irvin, J. L., Meltzer, J., and Dukes, M. (eds.) (2007). Taking Action on Adolescent Literacy: An Implementation Guide for School Leaders. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ACDS).

Jenkins, L. N., Floress, M. T., and Reinke, W. (2015). Rates and types of teacher praise: a review and future directions. Psychol. Sch. 52, 463–476. doi: 10.1002/pits.21835

Jimerson, S. R., Campos, E., and Greif, J. L. (2003). Toward an understanding of definitions and measures of school engagement and related terms. Calif. Sch. Psychol. 8, 7–27. doi: 10.1007/BF03340893

Kahu, E., Stephens, C., Leach, L., and Zepke, N. (2015). Linking academic emotions and student engagement: mature-aged distance students’ transition to university. J. Further High. Educ. 39, 481–497. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2014.895305

Kalis, T. M., Vannest, K. J., and Parker, R. (2007). Praise counts: using self-monitoring to increase effective teaching practices. Prevent. Sch. Fail. Alter. Educ. Child. Youth 51, 20–27. doi: 10.3200/PSFL.51.3.20-27

Khalilzadeh, S., and Khodi, A. (2021). Teachers’ personality traits and students’ motivation: a structural equation modeling analysis. Curr. Psychol. 40, 1635–1650. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-0064-8

Komarraju, M., Karau, S. J., and Schmeck, R. R. (2009). Role of the big five personality traits in predicting college students' academic motivation and achievement. Learn. Individ. Differ. 19, 47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2008.07.001

Kulakow, S., and Raufelder, D. (2020). Enjoyment benefits adolescents’ self-determined motivation in student-centered learning. Int. J. Educ. Res. 103:101635. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101635

LaBelle, S., and Johnson, Z. D. (2020). The relationship of student-to-student confirmation and student engagement. Commun. Res. Rep. 37, 234–242. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2020.1823826

Leach, D. J., and Dolan, N. K. (1985). Helping teachers increase student academic engagement rate: the evaluation of a minimal feedback procedure. Behav. Modif. 9, 55–71. doi: 10.1177/01454455850091004

Linvill, D. (2014). Student interest and engagement in the classroom: relationships with student personality and developmental variables. Southern Commun. J. 79, 201–214. doi: 10.1080/1041794X.2014.884156

Liu, W. (2021). Does teacher immediacy affect students? A systematic review of the association between teacher verbal and non-verbal immediacy and student motivation. Front. Psychol. 12:713978. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713978

MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., and Mercer, S. (2019). Setting an agenda for positive psychology in SLA: theory, practice, and research. Mod. Lang. J. 103, 262–274. doi: 10.1111/modl.12544

Marchant, M., and Anderson, D. H. (2012). Improving social and academic outcomes for all learners through the use of teacher praise. Beyond Behav. 21, 22–28. doi: 10.1177/107429561202100305

Martin, A. J. (2007). Examining a multidimensional model of student motivation and engagement using a construct validation approach. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 77, 413–440. doi: 10.1348/000709906X118036

Martin, A. J. (2013). Improving the achievement, motivation, and engagement of students with ADHD: the role of personal best goals and other growth-based approaches. J. Psychol. Couns. Sch. 23, 143–155. doi: 10.1017/jgc.2013.4

Martin, A. J., Ginns, P., and Papworth, B. (2017). Motivation and engagement: same or different? Does it matter? Learn. Individ. Differ. 55, 150–162. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2017.03.013

Mottet, T. P., Frymier, A. B., and Beebe, S. A. (2006). “Theorizing about instructional communication,” in Handbook of Instructional Communication: Rhetorical and Relational Perspectives. eds. T. P. Mottet, V. P. Richmond, and J. C. McCroskey (Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon), 255–282.

Papi, M., and Abdollahzadeh, E. (2012). Teacher motivational practice, student motivation, and possible L2 selves: an examination in the Iranian EFL context. Lang. Learn. 62, 571–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2011.00632.x

Pedler, M. L., Willis, R., and Nieuwoudt, J. E. (2021). A sense of belonging at university: student retention, motivation and enjoyment. J. Further High. Educ., 1–12. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2021.1955844

Pekrun, R., and Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2012). “Academic emotions and student engagement,” in Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. eds. S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, and C. Wylie (Boston, MA: Springer), 259–282.

Philp, J., and Duchesne, S. (2016). Exploring engagement in tasks in the language classroom. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 36, 50–72. doi: 10.1017/S0267190515000094

Qureshi, A., Wall, H., Humphries, J., and Balani, A. B. (2016). Can personality traits modulate student engagement with learning and their attitude to employability? Learn. Individ. Differ. 51, 349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2016.08.026

Reeve, J. (2012). “A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement,” in Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. eds. S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, and C. Wylie (Boston, MA: Springer), 149–172.

Reinke, W. M., Lewis-Palmer, T., and Merrell, K. (2008). The classroom check-up: a classwide teacher consultation model for increasing praise and decreasing disruptive behavior. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 37, 315–332. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2008.12087879

Richard, B. J. (2012). The effects of teacher praise on engagement and work completion of students of typical development. Doctoral Dissertation. Hattiesburg, Mississippi: The University of Southern Mississippi.

Rostami, S., Talepasand, S., and Rahimian Bogar, I. (2017). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between personality traits and academic engagement. J. Educ. Psychol. Stud. 14, 103–122. doi: 10.22111/jeps.2017.3242

Sabet, M. K., Dehghannezhad, S., and Tahriri, A. (2018). The relationship between Iranian EFL teachers’ self-efficacy, their personality and students’ motivation. Int. J. Educ. Literacy Stud. 6, 7–15. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.6n.4p.7

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., and Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 3, 71–92. doi: 10.1023/A:1015630930326

Shen, T., and Croucher, S. M. (2018). A cross-cultural analysis of teacher confirmation and student motivation in China, Korea, and Japan. J. Intercult. Commun. 47, 1404–1634.

Shernoff, E. S., Lekwa, A. L., Reddy, L. A., and Davis, W. (2020). Teachers’ use and beliefs about praise: a mixed-methods study. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 49, 256–274. doi: 10.1080/2372966X.2020.1732146

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., and Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 69, 493–525. doi: 10.1177/0013164408323233

Skinner, E. A., and Pitzer, J. R. (2012). “Developmental dynamics of student engagement, coping, and everyday resilience,” in Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. eds. S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, and C. Wylie (Boston: Springer), 21–44.

Titsworth, B. S. (2000). The effects of praise on student motivation in the basic communication course. Basic Communication Course Annual, 12, 1–27.

Trad, L., Katt, J., and Neville Miller, A. (2014). The effect of face threat mitigation on instructor credibility and student motivation in the absence of instructor nonverbal immediacy. Commun. Educ. 63, 136–148. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2014.889319

Ushioda, E. (2008). “Motivation and good language learners,” in Lessons from Good Language Learners. ed. C. Griffiths (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 19–34.

Wang, Y., Derakhshan, A., and Zhang, L. J. (2021). Researching and practicing positive psychology in second/foreign language learning and teaching: the past, current status and future directions. Front. Psychol. 12:731721. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731721

Wehlage, G., Rutter, R., Smith, G., Lesko, N., and Fernandez, R. (eds.) (1989). Reducing the Risk: School as Communities of Support. Philadelphia: The Falmer Press.

Xie, F., and Derakhshan, A. (2021). A conceptual review of positive teacher interpersonal communication behaviors in the instructional context. Front. Psychol. 12:708490. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.708490

Zhang, W., Su, D., and Liu, M. (2013). Personality traits, motivation and foreign language attainment. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 4, 58–66. doi: 10.4304/jltr.4.1.58-66

Keywords: teacher praise, academic motivation, academic engagement, EFL classes, positive academic emotion

Citation: Peng C (2021) The Academic Motivation and Engagement of Students in English as a Foreign Language Classes: Does Teacher Praise Matter? Front. Psychol. 12:778174. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.778174

Edited by:

Ali Derakhshan, Golestan University, IranReviewed by:

Reza Bagheri Nevisi, University of Qom, IranYunxian Guo, Henan University, China

Reza Pishghadam, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran

Copyright © 2021 Peng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunju Peng, Y2h1bmp1OTE2MjAyMUAxNjMuY29t

Chunju Peng

Chunju Peng