- 1Centre for Compassion Research and Training, College of Health, Psychology and Social Care, University of Derby, Derby, United Kingdom

- 2The Compassionate Mind Foundation, Derby, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Psychology, University of Roehampton, London, United Kingdom

- 4Department of Economics and Social Sciences, John Cabot University, Rome, Italy

- 5Compassionate Mind ITALIA, Rome, Italy

- 6School of Human Health Sciences, University of Florence, Florence, Italy

- 7Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham, United Kingdom

- 8Department of Philosophy, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 9College of Health, Psychology and Social Care, University of Derby, Derby, United Kingdom

- 10Lattice Coaching and Training, Chesterfield, United Kingdom

Background: Compassion focused therapy (CFT) is an evolutionary informed, biopsychosocial approach to mental health problems and therapy. It suggests that evolved motives (e.g., for caring, cooperating, competing) are major sources for the organisation of psychophysiological processes which underpin mental health problems. Hence, evolved motives can be targets for psychotherapy. People with certain types of depression are psychophysiologically orientated towards social competition and concerned with social status and social rank. These can give rise to down rank-focused forms of social comparison, sense of inferiority, worthlessness, lowered confidence, submissive behaviour, shame proneness and self-criticism. People with bipolar disorders also experience elevated aspects of competitiveness and up rank status evaluation. These shift processing to a sense of superiority, elevated confidence, energised behaviour, positive affect and social dominance. This is the first study to explore the feasibility of a 12 module CFT group, tailored to helping people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder understand the impact of evolved competitive, status-regulating motivation on their mental states and the value of cultivating caring and compassion motives and their psychophysiological regulators.

Methods: Six participants with a history of bipolar disorder took part in a CFT group consisting of 12 modules (over 25 sessions) as co-collaborators to explore their personal experiences of CFT and potential processes of change. Assessment of change was measured via self-report, heart rate variability (HRV) and focus groups over three time points.

Results: Although changes in self-report scales between participants and across time were uneven, four of the six participants consistently showed improvements across the majority of self-report measures. Heart rate variability measures revealed significant improvement over the course of the therapy. Qualitative data from three focus groups revealed participants found CFT gave them helpful insight into: how evolution has given rise to a number of difficult problems for emotion regulation (called tricky brain) which is not one’s fault; an evolutionary understanding of the nature of bipolar disorders; development of a compassionate mind and practices of compassion focused visualisations, styles of thinking and behaviours; addressing issues of self-criticism; and building a sense of a compassionate identity as a means of coping with life difficulties. These impacted their emotional regulation and social relationships.

Conclusion: Although small, the study provides evidence of feasibility, acceptability and engagement with CFT. Focus group analysis revealed that participants were able to switch from competitive focused to compassion focused processing with consequent improvements in mental states and social behaviour. Participants indicated a journey over time from ‘intellectually’ understanding the process of building a compassionate mind to experiencing a more embodied sense of compassion that had significant impacts on their orientation to (and working with) the psychophysiological processes of bipolar disorder.

Introduction

The bipolar cluster of disorders, which include bipolar I, bipolar II and cyclothymic disorders, are major, debilitating forms of mental health difficulties (Grande et al., 2016). The incidence for the narrow definitions is estimated at around 1–2.4% but becomes higher if one includes the cyclothymic disorders (Merikangas et al., 2011; Grande et al., 2016). Latalova et al. (2014) suggest that 25–50% will make at least one suicide attempt and 8–19% will eventually die by suicide. The risk of suicide increases in the presence of hopelessness, previous attempts, family history, poor social relationships, and substance abuse (Simpson and Jamison, 1999; Latalova et al., 2014). Bipolar disorders are affected by the quality of early and current family and social relationships (Greenberg et al., 2014). Early trauma is especially important (Aas et al., 2016). Trauma in younger patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder is associated with increased suicide risk, depression severity and poor functioning compared to non-traumatised patients (de Azambuja Farias et al., 2019). Bipolar disorders also have a range of detrimental effects on family, social and work relationships which further compromises the potential for helpful social relationships (Greenberg et al., 2014). Indeed, given the impact of social support and understanding for prognosis, a number of researchers have highlighted the importance of addressing styles of social relating for these individuals (Owen et al., 2017). People with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder also have elevated physical health risks. For example, Weiner et al. (2011) point out that people with this diagnosis may have nearly double the risk of cardiovascular disorders than the general population.

Although there are genetic and physiological processes underpinning vulnerability to this family of disorders (Gordovez and McMahon, 2020) these processes interact with trauma and a range of psychological and psychosocial factors (Aas et al., 2016). Hence, various psychosocial therapies have been developed as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy offering psychoeducation, cognitive and behavioural skills training (Vieta et al., 2018; Davenport et al., 2019) and psychosocial interventions (Swartz and Swanson, 2014; Miklowitz et al., 2021). In addition, psychotherapies are increasingly seeking to become more integrative, biopsychosocial (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 1995, 2013; Cozolino, 2017; Music, 2019; Siegel, 2019; Gilbert and Simos, 2022) and process-focused (Gilbert and Kirby, 2019; Watkins and Newbold, 2020). This is because of the growing scientific understanding of the complex co-regulating links between biological, psychological, and social processes in the areas of causation, maintenance, recovery, and change (Cozolino, 2017; Haslam et al., 2018; Porges and Dana, 2018; Kumsta, 2019; Schore, 2019). Dodd et al. (2019) have also addressed the important area of emotion regulation for people with these diagnoses and raised issues over the discrepancies between state and trait emotion regulation strategies. Recent NICE guidelines highlight the need to develop therapies that are specifically designed for people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (Jauhar et al., 2016). Hence, this study explores the modification of compassion focused therapy (CFT) for people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder which seeks to address different aspects of functioning in the areas of motivation and emotion regulation, cognitive and physiological processes, and social relationships.

An Evolved, Biopsychosocial Approach to Therapy

Compassion focused therapy is an evolution informed, biopsychosocial approach to mental health difficulties that draws on interventions from a range of different schools of therapy (Gilbert, 2000, 2010; Gilbert and Simos, 2022). One guiding framework for pursuing a biopsychosocial integration for psychotherapy is evolutionary functional analysis (EFA) (Gilbert, 1995, 1998, 2019, 2020a; Gilbert and Bailey, 2000; Nesse, 2019; Workman et al., 2020). EFA highlights that evolved motivation and emotional processes are underpinned by evolved, complex physiological if A then do B (stimulus response) algorithms which give rise to brain states (Gilbert, 1984, Gilbert, 1989/2016; Gilbert and Simos, 2022). For example, if a stimulus indicates threat, this triggers defensive behaviour. If a stimulus indicates sexual opportunity, then this generates sexual arousal and courting behaviour. The motive of caring has the algorithm of if stimulus indicates distress or need, then this activates behaviours to alleviate them. Clearly, this is just the basic process. In reality, according to the species, there will be multiple complexities such as higher cognitive processes such as mentalizing (Luyten et al., 2020). Nonetheless, CFT targets the specific activation and cultivation of compassion motivation as the framework for interventions because it evolved with neuro- and psychophysiological regulators (e.g. oxytocin and changes to the vagus nerve; Carter et al., 2017) that have profound effects on a range of physical and mental health parameters (Brown and Brown, 2015; Mayseless, 2016; Seppälä et al., 2017; Vrtička et al., 2017). These facilitate prosocial behaviours and the building of caring supportive relationships that have health and wellbeing benefits (Kirby and Gilbert, 2017; Seppälä et al., 2017; Gilbert and Simos, 2022). In addition, compassion has long been recognised as a means to address problematic mental states and suffering in self and others, with a range of interventions, such as mindfulness and compassion focusing (Dalai Lama, 1995; Ricard, 2015) that can be adapted and adopted into western psychotherapy (Germer and Siegel, 2012; Gilbert and Simos, 2022).

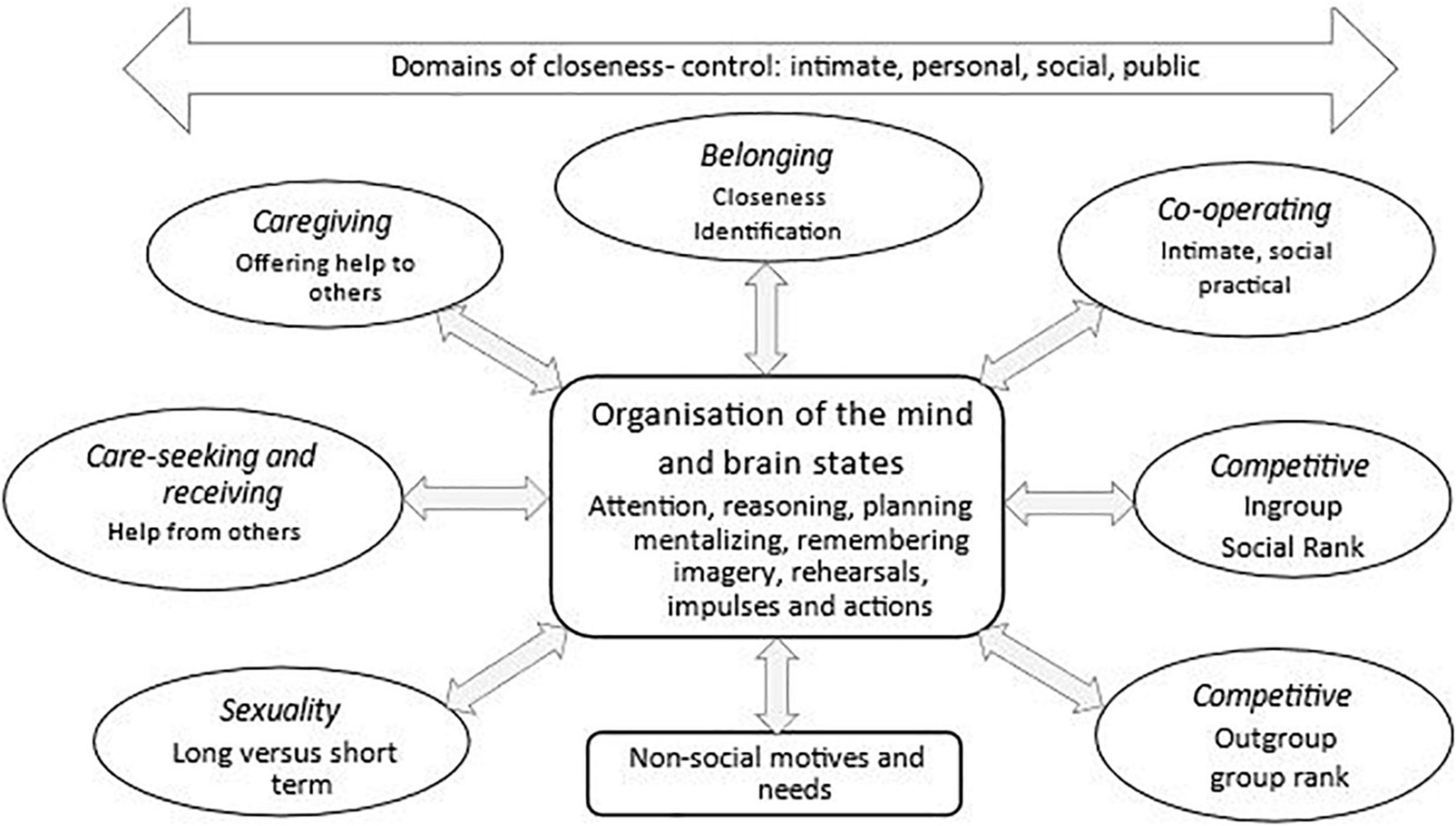

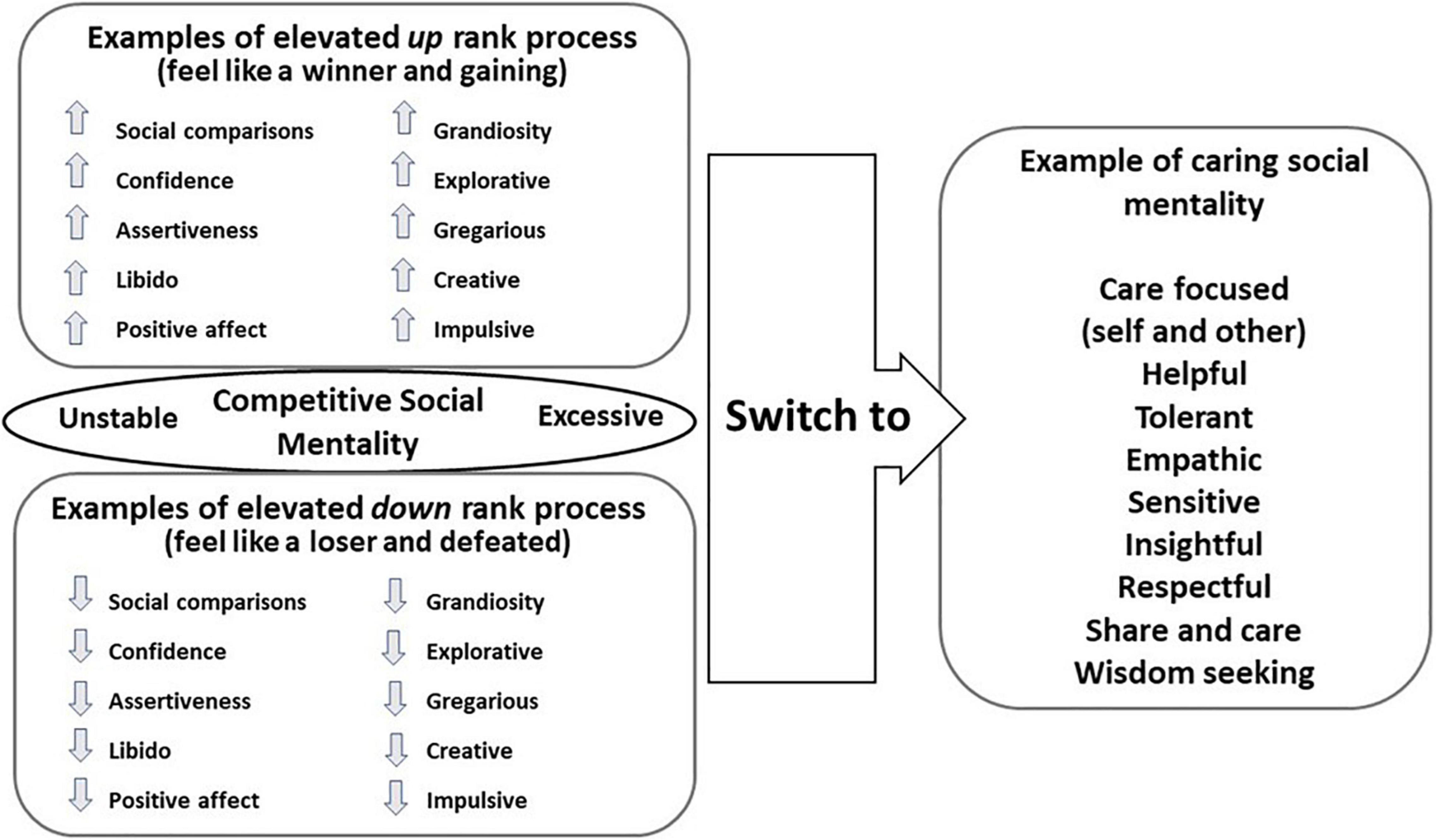

Compassion focused therapy distinguishes between non-social and social motives, and between different social motives (called social mentalities). Examples include: motives for care giving, seeking and responding to care, cooperating, competing and forming social ranks, group formation, and sexuality. Understanding these distinctions is important because evolved motives and their algorithms and multiple derivatives are not only linked to different physiological systems, but are the primary organising functions of the mind, with emotions and cognitive competencies being recruited to pursue the goals of a motive(s). Hence, as depicted in Figure 1, what we pay attention to, how we reason, the actions we plan and enact will be very different according to whether we are caring for somebody, seeking a sexual relationship, competing or arguing with them or seeking help from them. Importantly too, the physiological patterns and brain states will be quite different according to our motives. Differences in social motives are also impacted by the domains of closeness, the nature of the relationship such as how intimate or more distant they are in public to us. Important too is whether the relationship is sought out and wanted or whether it’s imposed by others, a voluntary or involuntary form of relating.

Compassion focused therapy suggests that social motives are different to non-social motives and are called social mentalities (Gilbert, 1989/2016). They create different types of social reciprocal roles, partly because social motives co-evolve to create dynamic reciprocal patterns of interactions. For example, infants could not evolve care seeking behaviours if ‘parents’ were not also evolving abilities to detect infant needs and distress and respond appropriately. Powerful, dynamic reciprocal patterns of interactions emerge as mother and infant come to co-regulate each other (Nguyen et al., 2020). Submissive behaviour and communications could not evolve unless individuals in dominant positions also evolved competencies to detect such signals and de-escalate conflict. Sexual behaviour is another obvious relational form that has to co-evolve in terms of mutual stimulation of sexual receptivity. Social mentalities require specialist processing systems to decode specific social signals in terms of their meaning, the motivation of the sender and the selection of appropriate responses for specific roles (e.g., caring, competing or sexual) (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2005, 2019). Hence, we have different processing systems for co-creating (say) sexual relationships, caring relationships, dominant-subordinate relationships and ingroup-outgroup relationships. Individuals may be sensitive and competent in some role relationships but not all (Liotti and Gilbert, 2011). For example, some individuals may interpret a friendly signal as exploitive or dangerous; be inappropriately trusting or mistrusting; maybe caring or callous in the face of distress. CFT suggests many mental health problems are linked to problematic pursuits, interactions and conflicts between different social mentalities both between and within individuals. One common conflict is competing for social control, status and resources, in contrast to creating sharing, caring and supportive connections and relationships between self and others Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2000, 2010, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c, 2021).

The Problem of Competitiveness and Social Rank Evaluation in Bipolar Affective Disorder

A major social challenge for many species is how to secure resources when conspecifics are seeking (competing) to gain and control the same resources. Hence, a major evolutionary and social challenge was how to live in social groups where individuals would challenge each other. Price (1972) was one of the first to argue that going up and down the ranks had very different impacts on invigorating or deactivating behaviour, mood and physiology. In order to inhibit constant fighting, with the risk of injury, mechanisms for the judgement of social rank evolved (Price, 1972; Gardner, 1982; Price and Sloman, 1987; Gilbert, 1992; Sloman and Gilbert, 2000). Winning required different subsequent behaviours to losing. Winning triggers behavioural activation to take advantage of winning, elevated drive-linked positive affect and feeling energised, confident and explorative. In contrast, losing, and where there was a likelihood of losing again and/or where those more powerful would be vigilant and hostile to efforts to one’s ‘up rank bids’ for resource control, required a reassessment of one’s ability to challenge or defend against others (Sloman et al., 2011). In these contexts, there is a behavioural deactivation/demobilisation, turning off confident, explorative and resource seeking motivation, down-regulation of positive affect, awareness of inferior status/ability and vulnerability, with (often but not always) tendencies to be submissive, appeasing and socially anxious and/or to socially withdraw (see Gilbert, 2000, 2020b; Gilbert and Basran, 2019 for a recent review). Hollis and Kabbaj (2014) provide an extensive review of the physiological, psychological and social changes that occur in animals following defeats and how they closely map processes identified for certain depressions. Sloman (2000) labelled the defeat response an involuntary defeat strategy (IDS). In order to further research on the experiences of defeat, and internal and external entrapment, Gilbert and Allan (1998) developed a self-report measure for defeat and entrapment. Many studies across different client groups have now shown that these are different but interacting processes that are highly correlated with depression and suicidality (Gilbert et al., 2002; Taylor et al., 2011; Siddaway et al., 2015; Wetherall et al., 2019; Höller et al., 2020).

In regard to the role of competitive and dominant-subordinate behaviour in relationship to bipolar disorder, over 50 years ago, Janowsky et al. (1970) drew attention to the competitive and dominant type behaviours of (hypo)manic patients, including with their clinicians. Gardner (1982) further developed the idea that the phenomenology of bipolar disorders links to evolved processing systems that regulate competitive social rank behaviour. Just as in winning social contests and becoming dominant, animals can become energised in their resource seeking behaviour and sexuality, those losing and being socially defeated become socially withdrawn with changes in physical states (Gardner, 1982; Sloman et al., 2011). Wilson (1998) noted that the epidemiology for bipolar disorder was high, indicating positive selection for phenotypic variation in response to the challenges of resource competition in social hierarchical contexts. Johnson et al. (2012) also suggested that the striving for social dominance motivation system regulates mood, attention and energy, and underpins bipolar disorders. While people with unipolar depressions are often striving to avoid unwanted inferiority associated with shame and being rejected (Gilbert et al., 2007), those who shift into more (hypo)manic states can see themselves as superior and are striving to elevate their social control and social status (Johnson et al., 2005, 2012). When in elevated mood, people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder tend to see themselves as superior and have a sense ‘specialness’ (Jamison, 2015). Gilbert et al. (2007) found that in a relatively stable group of people with this diagnosis, their mood variation was linked to elevated changes in social comparison where positive emotion was associated with feeling superior and more talented, competent and attractive than others, indicating that their positive emotion seems to be overly linked into rank evaluative systems. For non-bipolar people, however, elevated positive emotion such as winning a lottery is not necessarily associated with a change in social cognition such that one feels ‘superior, more talented or special’.

Further evidence that the competitive social mentality underpins bipolar disorder comes from Johnson and Carver (2006). They found that individuals vulnerable to bipolar disorder set high ambitious goals particularly for fame, wealth and political influence but less so for other prosocial goals. Similarly, Gruber and Johnson (2009) found that people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder scored higher on interest in competitive goals, particularly of achievement, and less on compassion goals. In a recent review Ironside et al. (2020) note that patients with this diagnosis set extremely high goals for themselves and see achieving those goals as central to their self-worth. They are therefore highly sensitised to cues of reward and show elevated responses to laboratory manipulations involving success (Meyer et al., 2010; Pavlova et al., 2011), with less reactiveness to failures unless in a depressed phase (Wright et al., 2008). In a major review, Gruber (2011) noted that ‘recent research has suggested that bipolar disorder is associated with elevations in positive emotion specifically to reward and achievement-oriented emotions relative to pro social emotions’ (p. 359). In addition, when people move into hypomanic states, they can become impulsive with poor emotion regulation (Musket et al., 2021), grandiose, and if blocked, confrontative with authority (Janowsky et al., 1970). Hence, a number of researchers have highlighted the fact that the mechanisms regulating competitive behaviour, social rank and self-evaluation, are unstable in people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. This makes them vulnerable to extremes of ‘up and down rank brain state shifting’. The clinical question therefore is ‘is it possible to help clients understand this motivational system and how to cultivate a different motivational system which will introduce more psychophysiological stability?’ The candidate for this is the caring system (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2020a; Cassidy and Shaver, 2016; Mayseless, 2016).

The Evolution of Caring and Compassion

Caring and compassion motives evolved for very different reasons than those for conflict competition and have very different impacts on brain states and reciprocal interactions (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2020b; Goetz et al., 2010; Mayseless, 2016). One of the primary functions of caring is to provide resources that support the survival of offspring into adulthood (Brown and Brown, 2015; Cassidy and Shaver, 2016; Music, 2017). The evolution of attachment behaviour brought with it competencies to be sensitive to the developmental needs of offspring, such as for feeding, thermoregulation and protection and provide for their psychophysiological maturation and development. Hence, the evolution of caring behaviour created new algorithms, rooted in particular psychophysiological systems, that attuned attention, social processing and action systems to the ‘role of caring’ (Bowlby, 1969; Gilbert, 1989/2016; Cassidy and Shaver, 2016; Mayseless, 2016). Among the most salient physiological systems are those related to oxytocin and endorphins (Depue and Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005; Carter, 2017; Carter et al., 2017; Siegel, 2020) changes to the parasympathetic nervous system, and in particular the myelination of the vagus nerve (Porges, 2017, 2021a,2021b) and a range of specific neurocircuits (Vrtička et al., 2017). Attachment theory and research have shown that over and above physical needs, the parent provides for a secure base and safe haven (Bowlby, 1969; Cassidy and Shaver, 2016). A secure base provides the context for learning, guidance and play and in humans, a sense of being loved and lovable, and that others are trustworthy and helpful. A safe haven soothes and calms distress or over excitement and provides inputs for physiological and emotional regulation. These inputs are fundamental to the development of the child’s emotional insights, tolerance and regulation and their basic orientation to the social world. In addition, support throughout life from partners and peers can play a fundamental role in helping people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder cope with the disorder and being treatment adherent. Partner and peer social support have a particular impact on depressive symptoms and coping with depression (Greenberg et al., 2014).

Crucially, empathic caring stimulates important psychophysiological systems (as noted above) that enable the child to become caring of themselves and others and are linked to health and wellbeing (Brown and Brown, 2015; Mayseless, 2016; Music, 2017; Siegel, 2020; Ellis et al., 2021). Tragically when these inputs are not provided, and the child experiences non-empathic, hostile or neglectful ‘caring’ these impact their epigenetic profiles (Cowan et al., 2016), various neurocircuits (Lippard and Nemeroff, 2020), the basic psychophysiological core algorithms for enabling emotion and self-regulation, and the competencies to enter social life socially confident (Music, 2017; Siegel, 2020). They are more likely to become over reliant on threat-based, self-focused competitive strategies to get through life (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2020c; Gilbert and Simos, 2022). When children are forced into being self-protective, they can take one of two social rank strategies. One is to be very vigilant of social risk and adopt appeasing, submissive lifestyles (Gilbert, 2020b). The other is to be more resource, achievement and power seeking, what Johnson et al. (2011) called social dominance seeking. There is growing evidence that these social rank processes are very important regulators in mood disorders (Sloman and Gilbert, 2000; Gilbert et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2011; Hollis and Kabbaj, 2014; Wetherall et al., 2019). They operate along multiple dimensions such as superior-inferior, entitled-undeserving, submissive-aggressive, winner-loser/defeated, competent-incompetent, self-blame vs. other-blame, wanted-unwanted, shame prone vs. shameless, self-critical vs. other-critical (Gilbert, 1992, 2020a). In addition, self-criticism (a target for CFT and linked to the competitive social mentality) in contrast to self-compassion and self-reassurance have been shown to stimulate different neurophysiological pathways (Longe et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2020).

The Therapeutic Benefits of Motivation Switching

As noted, there is general agreement that people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder are characterized by swings between excessive positive mood and low mood associated with invigorated and demobilised behaviour and positive and negative self-evaluation (Power, 2005). Taking an evolutionary approach that seeks to identify the natural regulators of mood states, CFT follows the view that this instability is the result of problematic regulation of strategies and algorithms that regulate competitive behaviour in terms of navigating social challenges and social control (e.g., resource control and status). This algorithm can become internally regulated via biological oscillations, e.g., chronobiological rhythms that contribute to unstable and excessive oscillations within it (Gonzalez et al., 2019). Indeed, many models of bipolar disorder have highlighted the fact that individuals can switch into feeling dominant, with expansive feelings of confidence but also experience dramatic shifts into loss of energy, confidence, feeling defeated, inferior, worthless and incompetent. It is seeking to understand the functions of these changes in the context of a particular motivational process that can provide clues to the disorder. This is depicted in Figure 2. In essence then, for people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder the evolved motivation and processing systems for the regulation of conflict and resource acquisition within social ranks, is unstable and vulnerable to excessive switches of engagement and disengagement of resource seeking behaviour. Although these are presented as if they are unidimensional, that is unlikely because the physiology of dominance is not the opposite of the physiology of subordinate defeat states. This allows for mixed states.

Figure 2. An overview of the instability of the process underpinning social ranking and the movement towards caring motivational process. ©Paul Gilbert.

One way of working with people with this condition is to try to stabilise the rank system. However, CFT suggests that the attachment and caring systems evolved as psychophysiological, emotion and behavioural regulators and provide the foundation for well-being and health (Brown and Brown, 2015). Hence, therapies can seek to switch individuals out of defensive or excessive competitive motives into compassionate and caring ones. As noted above one reason for doing this is that it will shift not only a range of psychological processes but also physiological and social ones too. This shifting process is also depicted in Figure 2.

Any one motivation can have many different textures. For example, the way people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder seek and pursue social dominance can be very different from how psychopaths or narcissists do. People with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder lack the callousness, aggressiveness and hostility of those with psychopathic traits. In some ways psychopathic strategies look ‘more fitted’ to earlier primate and more hostile hierarchical contexts, whereas bipolar forms of competition maybe more fitted to hunter gatherer hierarchies of competing for attractiveness and demonstrations of talent (Gilbert and Simos, 2022). What they have in common is how they socially compare themselves with others and the drive for status and resource control (Tharp et al., 2021). Similarly, people can be compassionate in different ways. For example, risking one’s life to save others as a firefighter or a person working on a COVID-19 ward might not necessarily mean they are most empathic parent. Different roles require slightly different empathic competencies (Liotti and Gilbert, 2011). These variations are because brain states are complex interacting patterns of motives and emotions linked to life history and phenotypic maturation. In addition, people can behave kindly and compassionately for many reasons, including those for being liked (Böckler et al., 2016). One form can be submissive compassion (Catarino et al., 2014). Nonetheless, CFT seeks to help clients to become motivationally aware and practise cultivating compassion because of its biopsychosocial effects (Weng et al., 2018; Singer and Engert, 2019; Kim et al., 2020). Consequently, it uses a range of multi-modal interventions that address the four functions of mind, namely: motives, emotions, cognitive competencies, and behavioural enactments (Gilbert and Simos, 2022). There is increasing evidence that specific compassion practises that target these functions can have specific neuro and psychophysiological effects (Weng et al., 2018; Petrocchi and Cheli, 2019; Singer and Engert, 2019; Porges, 2021a,b). Especially important is to help clients develop an attachment-like inner set of competencies that provide for secure base and safe haven functions in how they relate to themselves (Gilbert, 2020b).

Compassion Focused Therapy

Compassion focused therapy defines compassion in terms of its evolved stimulus-response algorithm which is to be sensitive to (stimuli of) suffering in self and others with a (response of) commitment to try to alleviate and prevent it (Gilbert, 2020a). At times to be sensitive and engaged with suffering requires considerable courage and that includes with one owns distress. To take appropriate action can also require courage but in addition it requires wisdom. Courage without appropriate wisdom can be reckless or harmful and wisdom without courage can be ineffective. Clients are guided through this definition and to see that the core of compassion is to acquire the courage and wisdom to engage with suffering and difficulties and the courage and wisdom to work out, and practise what is helpful and to engage in appropriate action. There are six processes that support engagement with difficulties and distressed mind states. These include: to be motivated to develop compassion, becoming mindful and sensitive to emotional states, being sympathetically in tune with states of suffering and difficulty, being able to tolerate such states, being able to empathically understand and mentalize one’s mind and being open rather than condemning or pushing away what arises in one’s mind with changes of brain state. There are six suggested processes for taking action to prevent and alleviate suffering. These include: learning to remember to bring to one’s attention to what is likely to be helpful, using imaginary scenarios of what can be helpful, using mindfulness and compassionate reasoning, engaging in whatever appropriate helpful behaviour for the specific situation is required, using ‘body grounding’ when helpful, and tolerating as well as working with the emotions that can arise from taking helpful action. The same competencies are used when being compassionate to others.

These are contextualised in helping clients understand the nature of our evolved brains and how tricky they can be because they have been built by genes as vehicles to carry them into the subsequent generations (wisdom). We experience ourselves through the textures of motives and emotions made possible by gene-built and socially-shaped brains. In other words, our brains and minds were built for us, not by us. Clients begin to recognise that much of what is happening within them is not their fault but is part of activated, evolved motivational and emotion systems. These insights help them to then stand back, develop mindful observation skills and recognise that, rather than identify with any particular state of mind, they can begin to work with it (Germer and Siegel, 2012; Gilbert and Choden, 2013). This also involves mentalizing self and others (Luyten et al., 2020). Key to this process is to also help clients identify and work with hostile forms of self-criticism and unhelpful behaviors. Once people are aware and attentive to the evolved nature of mind, they can then practice switching to a compassionate focus and use various combinations of the twelve competencies outlined above. Hence, for any state of mind people are encouraged to consider ‘what would be helpful in contrast to harmful’.

Compassion focused therapy distinguishes compassion from kindness and other ways of being compassionate (Gilbert et al., 2019). As noted recently, in an important paper called Compassion is not a Benzo, Di Bello et al. (2021) highlight the fact that training in compassion does not mean that for any specific compassionate act people will be in a ‘calm mind’. For example, a firefighter or emergency COVID-19 clinician might not have a calm mind, but they are able to tolerate anxieties or other dysregulating emotions to maintain focus on intention. Having the physiological and psychological skills to hold intention is important and can be compared to physical training. Training exercises for compassion can be compared with getting fit. Getting fit does not mean one is in a state of activation all the time, but it means that when we need to run or engage in hard physical activity, we are able to do so, recover quickly and not collapse out of breath, unable to complete a task.

Although there is now clear research showing the beneficial effects of stimulating the psychophysiological mechanisms underpinning compassion, one of the challenges for therapy is that people carry many fears, blocks and resistances (FBRs) to it (Gilbert et al., 2011; Lawrence and Lee, 2014; Kirby et al., 2019). Among the fears are that compassion will make one weak or to lose ambition. People can also feel they do not deserve compassion (Pauley and McPherson, 2010). Another major problem is that stimulating compassion activates the attachment and care motivational systems. Traumas coded within those systems, such as neglect or abuse can become re-activated. Hence, rather than feeling connected, safe and relieved clients can begin to re-experience trauma associated with early attachment relationships (Gilbert and Simos, 2022). There is now considerable evidence that fears of compassion are linked to many mental health and anti-social behavioural problems (Kirby et al., 2019). Hence, these are core focuses of CFT (Gilbert and Simos, 2022).

Compassion focused therapy has proved successful for a range of trans-diagnostic and complex mental health difficulties (Basran et al., 2022) including those suffering with: psychosis and voice-hearing (Mayhew and Gilbert, 2008; Braehler et al., 2013; Heriot-Maitland et al., 2014), recovering from psychosis in a high-security setting (Laithwaite et al., 2009); personality disorders (Gilbert and Procter, 2006; Lucre and Corten, 2012) routine outpatients (McManus et al., 2018), community outpatient groups that included participants with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (Judge et al., 2012), survivors of domestic and gender abuse (Naismith et al., 2020). Brown et al. (2020) found that elements of compassionate mind training, in particular developing a compassionate image (coach) increased compassion for others and reduced paranoia in individuals with elevated paranoia scores. Forkert et al. (2022) developed a four-session compassion imagery intervention for clients with persecutory delusions. They found that this compassion intervention was feasible, acceptable, and based on qualitative analyses, was experienced as being helpful. This included participants ability to manage their difficulties and, in some cases, to feel safer and more self-accepting. Gilbert and Procter (2006) developed a module-based compassionate group therapy and mind training approach for day hospital patients. Their feedback, along with work with a number of groups and colleagues (see Gilbert and Simos, 2022 for examples) over the years have generated developments in group based CFT guidance and now there is a manual in preparation for publication (Gilbert et al., 2016–2022). Arnold et al. (2021) and Cattani et al. (2021) have developed a student-focused group CFT manual from our prepublication manual. Lowens (2010) was the first to develop an outline of CFT for people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. He highlighted the need to pay attention to clients’ tendencies for high self-criticism, difficulties with emotional regulation and engagement with compassion. Although not a research study, he articulated a number of areas where cultivating compassion was a challenge but when achieved was particularly helpful. Although some of the authors of this paper have experience of working with people with bipolar disorder, this is one of the first studies to explore group based CFT on client experience and change processes with participants with this diagnosis attending a support service.

Core Themes of Change

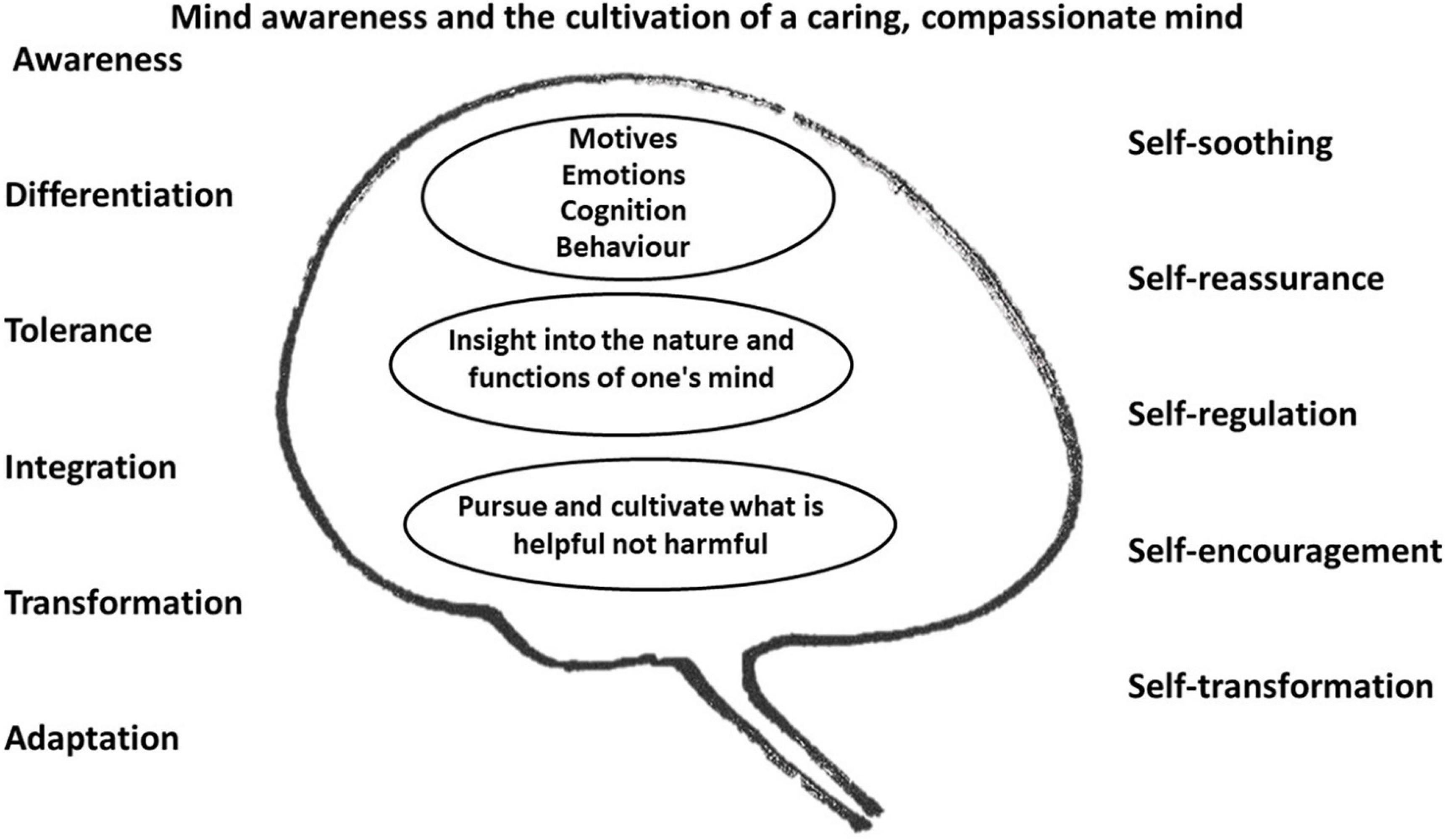

Many psychotherapies seek to help clients with common processes that include: Mind awareness, differentiation, tolerance, integration and transformation which increase people’s biopsychosocial abilities to adapt to changing internal and external events (Gilbert and Kirby, 2019; Gilbert and Simos, 2022). All these facilitate contextually appropriate psychophysiological (wise) flexibility. In addition they build on each other. For example, awareness facilitates differentiation (e.g., of motives, desires, emotions or beliefs) and differentiation increases awareness. Differentiation supports tolerance and tolerance supports openness to explore and differentiate processes within one’s inner mental life. CFT addresses these issues through evolution informed psychoeducation, integrating a range of standard evidence-based interventions such as body focused practices, mindfulness, cognitive reappraisal, visualisation/imagery, empathy training, validation, developing emotional awareness and tolerance and behaviour exposure practises and rehearsals. An overview is presented in Figure 3. These processes in turn develop people’s ability to be self-soothing, reassuring and encouraging and can transform people’s sense of an identity.

What is unique to CFT is how basic interventions are contextualised in psycho-education about why the human brain is tricky and can create these distressing states of mind. Also is the importance of recruiting the psychophysiological properties of the evolved caring social motive system (Vrtička et al., 2017; Singer and Engert, 2019; Gilbert and Simos, 2022). For example, cognitive reappraisal can be generated following a compassionate mind induction that involves particular breathing practises, body grounding and utilising the wisdom and intentionality of compassion. There is increasing evidence that specific practises and intention focusing can have major neurophysiological (Singer and Engert, 2019; Ashar et al., 2021) and physiological effects (Matos et al., 2018). Hence, one of the aims of a compassionate mind priming is to involve activation of the vagus nerve, oxytocin and various neurocircuits (particularly in the frontal cortex) known to be linked to compassion and to have threat regulating properties (Weng et al., 2018; Ashar et al., 2021; Matos et al., 2021).

Heart Rate Variability Profiles in Patients With a Diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder

As indicated, CFT is a biopsychosocial approach to therapy. In regard to the ‘bio’ aspects and related to neuroplasticity, compassion training can change a range of neurocircuits (Singer and Engert, 2019). Kim et al. (2020) highlighted the different neural signatures when people were being either self-reassuring or self-critical to a disappointment, rejection or a failure. They showed that the neural networks associated with threat processing are reduced with compassionate mind training (CMT). In addition, CMT significantly improved heart rate variability (HRV). HRV, especially the regulating functions of the vagus nerve, are linked to a range of psychological and health processes, prosociality (Porges, 2007, 2021a,2021b; Keltner et al., 2014; Kogan et al., 2014) and a sense of social safeness (Kelly et al., 2012). Social safeness may act as an emotion regulation process in its own right, linking a sense of caring social connectedness to such physiological benefits (Armstrong et al., 2021). There is evidence that people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder lack balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic activation (sympathovagal unbalance), with resulting reduced heart rate variability (Levy, 2014; Gruber et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016). In comparison with healthy controls, patients with this diagnosis tend to show lower resting HRV (Chang et al., 2014; Faurholt-Jepsen et al., 2017, for review; Henry et al., 2010; Quintana et al., 2016). Stimulating caring and compassion motives increases parasympathetic activity as measured through HRV (Rockliff et al., 2008; Matos et al., 2017; Petrocchi and Cheli, 2019; Kim et al., 2020; Steffen et al., 2021). Indeed, HRV is a recommended outcome measure for assessing CFT (Kirby et al., 2017) and a recent meta-analysis confirmed a significant association between compassion and HRV with a medium effect size (Di Bello et al., 2020).

Whilst there has been anecdotal evidence that CFT can be helpful to patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (Lowens, 2010) and that CFT can increase HRV in ‘healthy’ populations (Rockliff et al., 2008; Matos et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2020) and depressed students (Steffen et al., 2021), to date, no studies have assessed how people with bipolar disorders will experience a group based CFT, whether they will find it helpful and whether CFT can alter their HRV. To explore the latter, we first sought to explore if CFT impacts on baseline patterns of HRV. Second, we sought to explore if CFT can impact on HRV to specific evolutionary important themes. Gruber (personal communication) suggested that it can be revealing to explore how clients respond to certain provocations linked to their condition. Hence, we designed a competitive scenario and a social connectedness scenario. In the competitive scenario clients were invited to imagine winning and losing a competition. In the connectedness scenario participants were invited to imagine feeling socially connected and belonging and then loneliness. In general then, we sought to explore how people with this diagnosis will experience the psycho-education on evolution in relationship to their disorder, motivational shifting from rank focused to care focused processing and the practices to activate and cultivate compassion motive systems (Figure 2).

Aims

The aim of the present study was to examine the experience and feasibility of a 12 module CFT group tailored for individuals with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. The participants were clinically, and personally regarded themselves as relatively stable, not currently suffering from any major depression or hypomania episodes. They were invited as collaborators in this research project to explore the feasibility of CFT and to help modify current compassion focused interventions for bipolar disorder. We hypothesized that if participants were able to understand the nature of our ‘tricky brain’ and how motives organise the mind, and therefore the value of switching from a competitive focus to a compassion focus motivation orientation, this would have significant impact on coping with their bipolar disorder. In particular, there would be reductions in self-criticism and increases in self-compassion and openness to compassion. We studied changes in self-report measures and HRV at the beginning and end of the therapy, as well as changes in HRV related to specific scenario activations. In addition, we qualitatively explored and analysed participants’ detailed insights and reflections from three focus groups provided at different timepoints.

Materials and Methods

Design

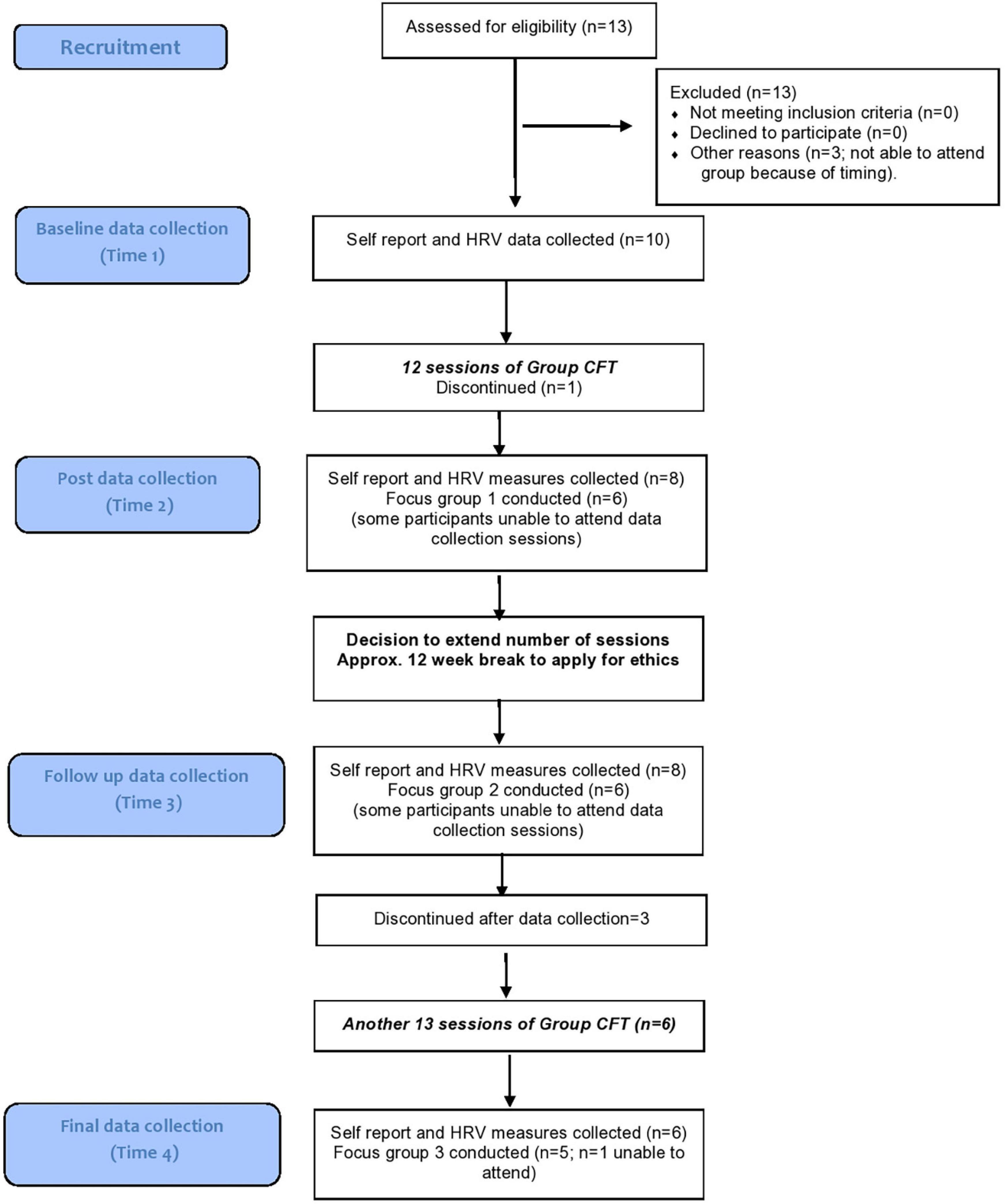

The study employed a repeated measures within-subjects design using self-report and HRV measures, as well as qualitative focus groups and therapist observations. The initial design proposed to deliver 12 modules of group CFT to explore its feasibility. As participants were invited as collaborators as part of the research study, we kept very close attention to their experience and their suggestions. They became very engaged with the therapy, and wanted to spend more time on each of the themes and content of the module than had been anticipated. Consequently after 12 sessions, a number of modules had not been completed and both participants and the therapists were very keen to see if we could extend the number of sessions so that the materials planned could be covered. Participants felt that 12 sessions were far too short and as the qualitative data will reveal they felt they had ‘only just got started’. So, with agreement from the participants and ethics, it was extended from 12 to 25 sessions (additional 13 sessions). The sessions were delivered once a week (where possible) for a duration of just over 47 weeks. There was a break of 2 weeks during the first 12 sessions due to Easter holidays and other contingencies and a 20-week gap between the two parts due to seeking permission for the extension from the ethics committee.

Self-report and HRV measures were collected at baseline; at the end of the first set of 12 sessions of group CFT; and after the 20-week break (and before the commencement of the second set of sessions); and finally at the end of the second set of sessions. Focus groups were conducted at all three time points after baseline: after the first 12 sessions, just before the start and then at the end of the second set of sessions. A further 1 year follow up was planned, unfortunately due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this was not possible.

Participant Engagement Process

One of the therapists, who is employed by a United Kingdom specialist Bipolar Service and interested in working with CFT, advised clients of the potential for research in a compassion focused approach for those with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and explored potential interest. Subsequently, PG who has run a number of CFT groups for complex cases, visited the bipolar service and offered a 1.5-h introduction on the evolutionary model of bipolar disorder (as related to social rank instabilities) and the nature of compassion. They then explored if the participants would be interested in taking part in a study exploring the impact of cultivating compassion. Some participants were enthusiastic and acknowledged that the idea of ‘instability of social rank mechanisms’ as rooted in evolutionary mechanisms that were not their fault was a novel and helpful way to think about their mood difficulties. They were intrigued by the idea that they could ‘maybe’ learn to explore and use compassion motives to be helpful. Approximately 6 months later, they along with other clients from the service were invited to participate in the study by their clinician who also took informed consent.

Inclusion criteria were that participants had a clinical diagnosis of, and had been treated for, a bipolar affective disorder and were relatively mood stable. The exclusion criteria were (i) being severely depressed or hypomanic, (ii) having other major mental health issues such as drug or alcohol use problems or organic complications that could interfere with the reliability of the study, and (iii) clinical or self-assessment as a suicide risk. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from London Central NRES Committee (REC ref 18/LO/1234 IRAS 248283).

Initially, 13 participants were recruited into the study, three of whom decided to withdraw before the group commenced as they were unable to attend all the sessions. The final group consisted of 10 participants, 6 women and 4 men aged 31–60 years old with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. All participants had previously attended the Bipolar Service where they received an intervention designed for those with a bipolar or cyclothymia diagnosis called Mood on Track. This draws heavily on a number of therapies including CBT, mindfulness and family therapy. During the course of the study, two participants withdrew because of work-related reasons, and two withdrew because they were offered additional support for their needs at the time which may have influenced the change process. Therefore four women and two men (aged 31–59) completed the full 25 sessions of CFT, attending an average of 82% of the sessions. All participants were taking medication, the most common of which was lithium (n = 4, associated with minimal effects on HRV; Bassett, 2016), followed by anti-psychotics (n = 3, associated with reduced HRV; Huang et al., 2016), anti-depressants (n = 2, associated with reduced HRV; O’Regan et al., 2015), anti-convulsant medication (n = 1), blood pressure medication (n = 1), thyroid medication, (n = 1), pain (n = 1) and sleep medication (n = 1).

For the full participant flow, refer to Figure 4.

Intervention

Compassion focused therapy was delivered by two qualified clinical psychologists (AR and AH). AR has extensive experience with CFT, and AH has attended CFT training and has extensive experience delivering psychological therapies for people with a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder. They were supervised regularly by the founder of CFT (Gilbert, 2000, 2009, 2020a). Another author (KL) facilitated the process of the project within the Trust.

As this study was a proof of principle, the initial plan was to deliver a standard 12 module program over 12 weeks. However, as participants became very engaged with the therapy, with desires to discuss it with the therapists and each other in detail, it became clear that the time necessary for working with this group was insufficient. Hence, the therapists and participants sought to extend the intervention. The ethics committee was contacted at the end of the initial 12 sessions to request an extension. This process took over 20 weeks during which time participants did not receive any active therapy but were able to practise the CFT exercises they learned during the first 12 sessions. Consequently, the intervention consisted of the original 12 sessions over 12 weeks (14 weeks in total when 2-week break due to holidays considered), a 20-week rest period and then another 13 sessions over 13 weeks. Therefore, the 12-module content was covered in 25 sessions over a total duration of 47 weeks when holidays and break (for ethics) considered.

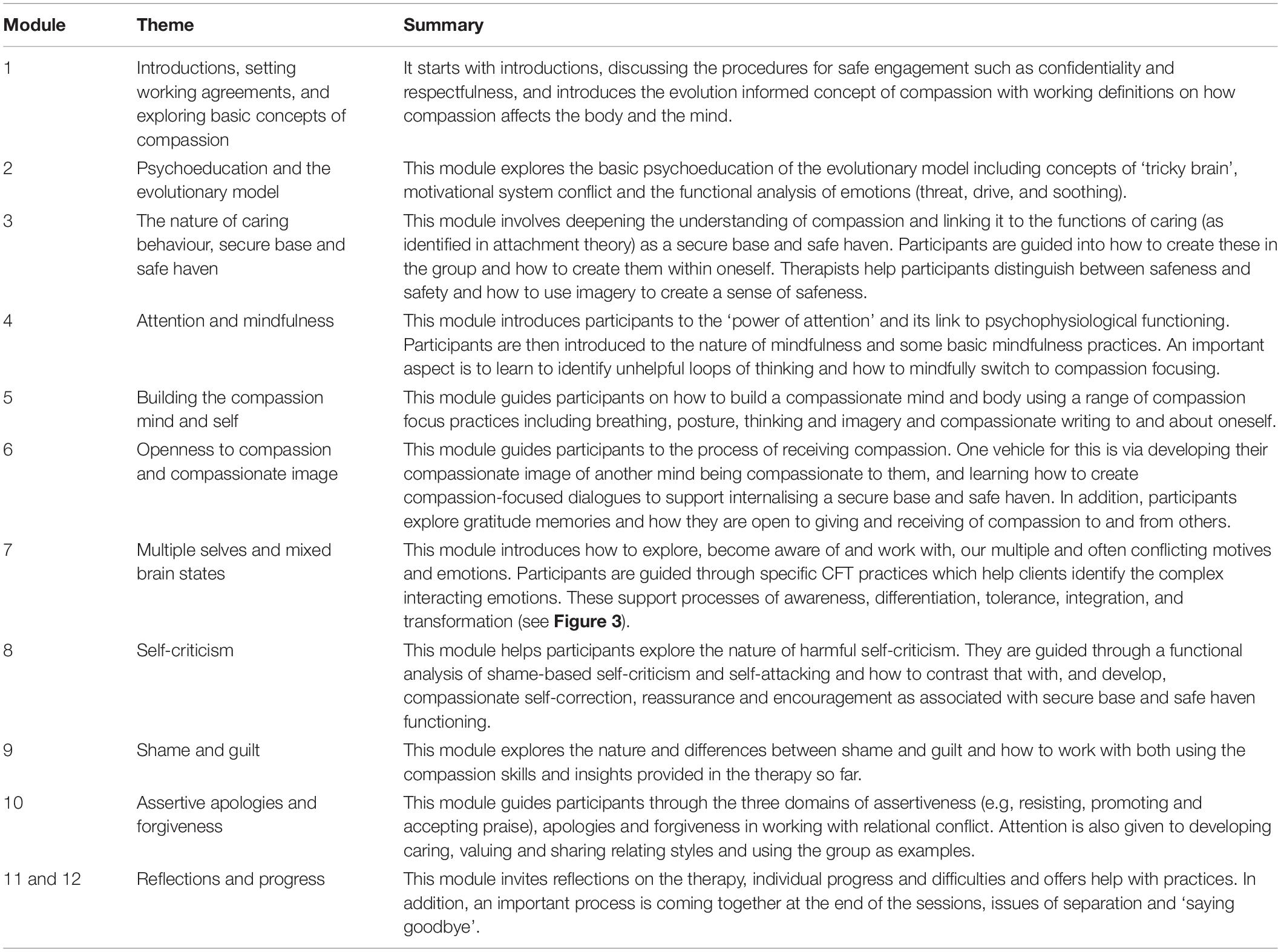

Group therapy was delivered once a week (where possible) covering material from a standardised manual for CFT using a modular approach derived from a manual in preparation (Gilbert et al., 2016–2022). Generally, the modules focus on specific themes and can take more than one session. For example, the self-criticism module was covered over three sessions. Additional sessions also focused on therapeutic processes such as when participants disclosed traumatic experiences or identified particular fears, blocks or resistances to compassion. Key to group CFT is the use of flip charts to regularly write up participant ideas, feedback and discussion. Therapists use participant feedback to draw diagrams of processes for reflection, and practises such as mindfulness and soothing rhythm breathing and creating compassionate images can be recorded, and copies given to clients. Summaries of sessions can be written up and given to participants with key points. The standard 12 modules are covered in Table 1.

A brief description of the module recommendations for compassion focused therapy are given in Supplementary Appendix 1. These are derived from an ongoing manual development (Gilbert et al., 2016–2022). Group psychotherapist Burlingame et al. (2018) attended training in CFT in the United Kingdom and utilised the manual noted above for working with university students (Arnold et al., 2021; Cattani et al., 2021). They have proceeded with research with good evidence for effectiveness (Fox et al., 2020; Steffen et al., 2021).

In this study the therapists followed the manual with some adaptations partly due to the fact that these clients, as part of the Bipolar Service, had already participated in a programme which draws heavily on CBT, family-focused therapy and mindfulness-based interventions, called Mood on Track. This programme includes 11 group sessions and a number of individual sessions alongside an ongoing monthly support group. As such, initially, the mindfulness module was touched on briefly and later expanded on to introduce opportunities to practise mindfulness and to facilitate a understanding of how mindfulness supports compassion. Moreover, some modules took longer than anticipated, therefore due to time constraints the module on assertiveness, apology and forgiveness was not covered.

Measures

Feasibility

As this was the first study to explore CFT group therapy for people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, we will identify the core themes recommended by Bowen et al. (2009). We are grateful to one of the reviewers for highlighting this approach. These include:

Demand arises from the epidemiology of the difficulty and need for, and availability of interventions.

Acceptability relates to how participants experience and react to an intervention.

Implementation addresses the degree to which an intervention can be fully implemented as planned and proposed.

Practicality addresses the issues of time commitment and resource availability.

Adaptation is concerned with any modifications as may be needed to accommodate different formats, media or populations.

Integration relates to the process of integrating the interventions into systems of care delivery.

Limited-efficacy testing relates to the evidence for preliminary effectiveness.

Self-Report Measures

The following self-report measures were completed:

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale

The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) (Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995) measures symptoms of depression ‘I felt that life was meaningless’, anxiety ‘I felt I was close to panic’ and, stress ‘I found it difficult to relax’. For this study, we have opted to use the short form of the original 42-item DASS. The 21-item short form has seven items from each of the original three subscales. Participants respond to the items on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much, or most of the time). This scale has high internal consistency, with Cronbach alphas of 0.94 for depression, 0.87 for anxiety, and 0.91 for stress (Antony et al., 1998).

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was developed by Zigmond and Snaith (1983) to provide a measure of severity of depression and anxiety in general medical environments. It consists of 14 items, seven of which measure depression, and the other seven anxiety, scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. The scale has high internal consistency for both anxiety (0.92) and depression (0.88) subscales (Djukanovic et al., 2017).

The Experiences Questionnaire

The Decentering subscale of the Experiences Questionnaire (EQ; Fresco et al., 2007) is an 11-item self-report instrument that assesses the construct of decentering, an ability to observe one’s thoughts and feelings as temporary, objective events in the mind, as opposed to reflections of the self that are necessarily true. Sample items include “I am better able to accept myself as I am” and “I can observe unpleasant feelings without being drawn into them”. The Decentering subscale has good internal consistency (0.83; Fresco et al., 2007).

Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale

The Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) (Watson et al., 1988) consists of two 10-item mood scales and was developed to provide brief measures of positive and negative affect. The items were derived from a principal components analysis of Zevon and Tellegen’s (1982) mood checklist. Participants are asked to rate the extent to which they have experienced each particular emotion within a specified time period, with reference to a five-point scale. A number of different timeframes have been used with the PANAS and we adopted ‘during the past week’ for this study. The scale has good internal for both factors, positive affect (0.90) and negative affect (0.91) (Serafini et al., 2016).

Three Types of Positive Affect Scale

Gilbert et al. (2008) developed this scale to measure the degree to which people experience different positive emotions. Participants are asked to rate 18 ‘feeling’ words on a five-point scale to indicate how characteristic it is of them (0 = ‘not characteristic of me’ to 4 = ‘very characteristic of me’). Factor analysis revealed three factors or subscales, these are: Activated Positive Affect (e.g., “excited”, “dynamic”, “active”); Relaxed Positive Affect (e.g., “relaxed”, “calm”, “peaceful”) and Safeness/Contentment Positive Affect (e.g., “safe”, “secure”, “warm”). The scale showed good psychometric properties with Cronbach alphas of 0.83 for Activating Positive Affect and Relaxed Positive Affect, and 0.73 for Safeness/Contentment Positive Affect (Gilbert et al., 2008).

Forms of Self-Criticism/Self-Reassuring Scale

The Forms of Self-Criticism/Self-Reassuring Scale (Gilbert et al., 2004) consists of 22-items and assesses participant’s self-critical thoughts and feelings about themselves during a perceived failure. Two subscales measure forms of self-criticising (inadequate self and hated self) and one subscale measures tendencies to be reassuring to the self (reassured self). Participants are asked to rate how they typically think and react when things go wrong for them and to respond on a five-point Likert scale (0–4). The scale has good reliability with Cronbach’s alphas of 0.90 for inadequate self, 0.86 for hated self, and 0.86 for reassured self (Gilbert et al., 2004).

Social Comparison

This scale was developed by Allan and Gilbert (1995) and consists of 11 bipolar constructs regarding rank and relationships with others in society. Each item is rated in a 10-point Likert scale. Low scores indicate to feelings of inferiority and general low rank self-perceptions. The Cronbach alpha was 0.91 in students and 0.93 in patients (Allan and Gilbert, 1995).

Social Safeness and Pleasure Scale

The Social Safeness and Pleasure Scale (SSPS) (Gilbert et al., 2009) was developed to assess the extent to which individuals feel a sense of warmth, acceptance, and connectedness in their social world. Participants rate their agreement with 11 statements using a Likert scale from 1 (“almost never”) to 5 (“almost all the time”). Previous research has found that this scale demonstrates good internal consistency (0.96) (Kelly and Dupasquier, 2016).

Compassion Engagement and Action Scale

The Compassionate Engagement and Action Scales (Gilbert et al., 2017) are three scales which measure self-compassion (“I am motivated to engage and work with my distress when it arises”), the ability to be compassionate to distressed others (“I am motivated to engage and work with other peoples’ distress when it arises”) and the ability to receive compassion from key persons in the respondent’s life (“Other people are actively motivated to engage and work with my distress when it arises”). In the first section of each scale, six items are formulated to reflect the six compassion attributes in the CFT model: sensitivity to suffering, sympathy, non-judgemental, empathy, distress tolerance and care for wellbeing. These sections also include two reversed filler items. The second section of the scale has four more items which reflect specific compassionate actions to deal with distress and an extra reversed filler item. Filler items are not included in the scoring. Participants are asked to rate each statement according to how frequently it occurs on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 = Never; 10 = Always). In their original study, the CEAS showed good internal consistencies and temporal reliability (Gilbert et al., 2017).

Heart Rate Variability Measurement

For controlled collection of heart rate variability (HRV) data, participants were asked to refrain from: (a) eating; (b) drinking tea or coffee; and (c) strenuous exercise, 2 h preceding the scheduled appointment. They were asked to: (a) follow a normal sleep routine the day before, recording sleep and wake times; (b) avoid intense physical training the day before, and (c) avoid alcohol for 24 h (Laborde et al., 2017). Upon arrival at the Bipolar Service, participants were welcomed by a clinician (unrelated to the delivery of their CFT course) and were seated whilst the clinician assisted them in attaching disposable electrodes to their wrist and ankle to measure their HRV via Biopack software. Participants were asked to sit as still as possible with both feet flat on the floor and their palms upwards on their thighs whilst they were led through two rank and two attachment-based imagery scenarios with neutral scenarios in between. Scenarios were presented using a PowerPoint presentation to aid with standardisation and timing of the scenarios, which lasted 3 min each with the neutral scenarios lasting 2 min each.

Before the first scenario, a short set of instructions were given to introduce the imagery task: ‘When imagining the situations, they don’t have to be actual memories. We would like you to use your imagination. You do not need to try to create vivid pictures in your mind when you are creating your imagined situations. It’s more important that you try to put yourself in a state of mind of being in that situation and the kind of feelings and thoughts that might arise for you. You may find that your mind wanders and you might not be able to keep it on task for very long. This is because our minds often wander and think about a range of things at the same time. Do not worry about this, just bring it back to your focus’. A presentation then guided participants to imagine two competitive scenarios (winning and losing) and two social connection scenarios (feeling connected to others and feeling lonely). For example, in the losing scenario participants were instructed to: ‘Try to imagine yourself in a situation where you feel defeated, and other people seem to have done better than you. This could be losing a competition or being rejected at a job interview’. In the social disconnection scenario participants were instructed to: ‘Try to imagine yourself in a situation where you feel lonely and isolated, and less connected to other people. This could be feeling different to other people and not being part of the group’. In an attempt to bring participants back to a neutral state, a scenario of imagining walking through a bookshop was used between each scenario. The sequence of scenarios was defeat, winning, lonely and connected, with neutral tasks in-between.

Focus Group

There is increasing evidence that people diagnosed with depressions may have very different subjective experiences and symptom profiles (Fried and Nesse, 2015). Consequently, in depth investigations of these mental states require opportunities for individuals to discuss and describe their subjective mental states. Therapists from cognitive-behavioural backgrounds are also recognising the importance of reintroducing detailed exploration of subjective experience into both therapy and research (Taschereau-Dumouchel et al., 2022). One of the central ways subjective experience is investigated is with qualitative methodology. Braun and Clarke (2014) point out that “…[q]ualitative research offers rich and compelling insights into the real worlds, experiences, and perspectives of patients and health care professionals in ways that are completely different to, but also sometimes complimentary to, the knowledge we can obtain through quantitative methods” (p. 1). The use of interview data was to explore in-depth how participants experienced the intervention. The interviews were conducted via a focus group at three time points after baseline: after the first 12 sessions of CFT, just before the second set of 13 sessions and at the end of the second set of sessions. Due to unforeseen circumstances (an emergency with one of the participants), the second focus group was interrupted, and recording stopped part way through the second question. As the participants provided relevant feedback in a short amount of time, the feedback was included for analysis. Moreover, due to personal commitments, some of the participants could not attend all the focus groups, therefore, six participants attended the first focus group, six attended the second, and five attended the third. As all participants were invited to join at the time of the focus group, the groups represent some of the participants who took part and at a later date may have withdrawn. As the focus groups focused on the impact of the intervention, rather individual outcomes (i.e., case studies), the authors decided to include all participant feedback for analysis as it was deemed relevant. All participants were given pseudonyms to preserve confidentiality.

Focus groups were led by the same interviewer, who used the same interview schedule for all three focus groups. The interviewer was not involved in the therapy, transcription or analysis. The below summarises the questions. Participants readily identified with the questions, although in retrospect it was felt that some of the wording of the interviews may have been initially unclear (and could be improved for future research), for example using words such as ‘psychoeducation’. Moreover, participants shared reflections additional to the specific questions and are included in the analysis.

• Question 1. This set of questions relate to your experience of the evolutionary model of compassion and how it might relate to your life situation. Can you describe how you experienced this in the psychoeducation?

• Question 2. This set of questions relates to the exercises and practices. As you know there were a series of exercises and practices relating to breathing, mindfulness and developing a compassionate sense of self and the compassionate image. Can you describe your experience of the exercises and practices, in general? How were the exercises and practices for you?

• Question 3. This set of questions relates to your general feelings of self-criticism: What, if any, impact might the exercises and materials have had on the way you think and treat yourself particularly at times of difficulty, setbacks or failures?

• Question 4. This set of questions relates to how this course has helped you in general with issues of mood and emotion. Do you think the course and its modules have in any way changed your approach to how you think about and manage your moods and emotions?

• The final set of questions are focused on moving forward and any other feedback. What would support you to grow and further cultivate your inner compassionate self and compassionate mind? Any other thoughts you would like to offer on your experiences, or any insights you would like to feed back to the research team on how to improve the therapy.

Data Analyses

Self-Report Measures

Data was analysed using SPSS versions 26. Results from all six participants who completed the study and completed the self-report measures are reported. Item-level missing data were imputed using the mode for scales with fewer than 20% of items missing. In the case where missing data was higher, last observations carried forward was used to calculate mean scores. Given this was a pilot study with a small number of participants, statistical analyses to determine significant differences were not used and instead, descriptive statistics and visual inspection of scores were considered.

Heart Rate Variability

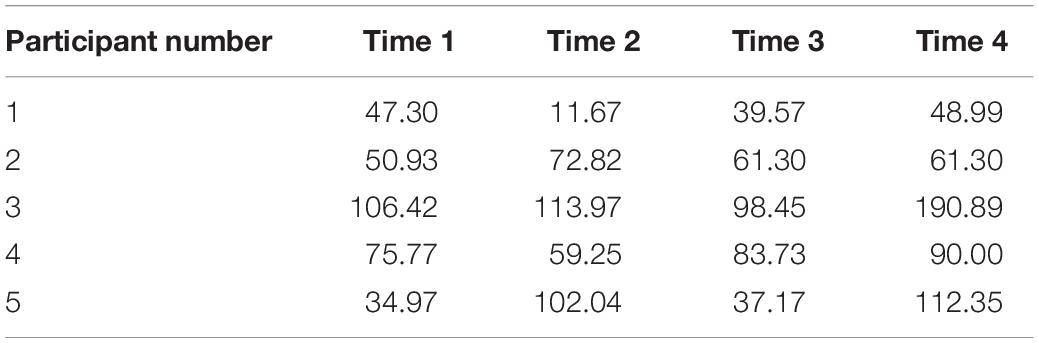

Electrocardiogram (ECG) signals were displayed on a laptop, using AcqKnowledge v. 4.1 (44), digitized at 2000 Hz and inspected offline using Kubios software – Premium version (45). Successive R waves (identified by an automatic beat detection algorithm) were visually inspected, and any irregularities were edited. Data that, after visual inspection, required more than 5% correction were excluded, resulting in missing data at baseline for one of the participants where it is thought that there was poor electrode connection. Thus, the data for that participant was not included in the analysis and only data from five participants was used. As CFT aims to increase vagally-mediated parasympathetic activity, a time domain measure of HRV (Root Mean Square Successive Difference; RMSSD) was then obtained for resting state, and for all the four scenarios at four assessment points (before and after the first and the second set of sessions). The RMSSD reflects the integrity of vagus nerve-mediated autonomic control of the heart (Laborde et al., 2017).

Given the pilot nature of this exploration, visual inspection and a non-overlapping method for analysing the difference between phases in single-case studies was implemented. Such a method is aimed at quantifying differences between two subsequent phases in a single-case design by descriptively summarizing the extent to which data points in the phases do not overlap (Parker and Vannest, 2009). The significance of non-overlap of all pairs (NAP) indexes were calculated for the five different scenarios combining all five cases (Vannest et al., 2016). The R package SCAN was used for all the analyses (RStudio Team, 2015).

Focus Group

Data analysis was conducted using the thematic approach (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2019) as this type of analysis offers flexibility and methodological rigour. This research adopted a deductive approach, where researchers worked with a predetermined framework relating to the research questions. These provided a structure to explore the experience of participants in regard to specific CFT processes. As mentioned in the previous section, six participants attended the first focus group, six attended the second, and five attended the third.

Two of the researchers (JR and HG) with qualitative research experience conducted the analysis. Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six phases of thematic analysis were followed for the three focus groups. JR completed the first phase by familiarising herself with the data and noting initial areas of interest. She then completed the second phase by compiling an extensive list of codes that aimed to capture the rich content of each focus group, before identifying connections between codes across the three focus groups. Codes were designed to match the participant’s own wording in order to maintain a fidelity to the data. These connections, which related to the most significant frequency of codes, became a focus for subsequent analysis. In phase three, JR identified potential themes with the aid of HG. In phase four, JR checked the codes against the theme candidates, and an initial thematic map was drawn up by JR and HG and presented to the research team. These themes were then matched against the research questions to identify potential connections. In phase five, an over-arching story of the data, created in accordance with the research questions but grounded in the data, was identified, and themes were clarified and named. In phase six, the themes were organised in order to present a coherent narrative of the findings in view of the research questions, and relevant extracts were selected.

Results

This section will explore the key principles of feasibility as suggested by Bowen et al. (2009) in regard to the information elicited from self-report HRV and focus groups measures.

Demand

Discussions during the initial exploratory session with PG confirmed that there was a great deal of interest in CFT. Participants were enthusiastic and acknowledged that the idea of ‘instability of social rank mechanisms’ as rooted in evolutionary mechanisms that were not their fault was a novel and helpful way to think about their mood difficulties. They were intrigued by the idea that they could ‘maybe’ learn to explore and use compassion motives to be helpful. This was further supported by comments during the focus groups (as outlined below in ‘Going Forward and Suggestions for the Future’ section). Furthermore, as noted in the introduction, these difficulties are relatively common, often with serious consequences to the quality of life of individuals and in need of improved therapies.

Acceptability

Participants indicated that the therapy group was perceived as helpful and was highly recommended for individuals with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder as well as for more general use by individuals (as outlined below particularly in ‘Going Forward and Suggestions for the Future’ section).

Implementation

The initial plan was to deliver a standard 12 module program over 12 weeks. However, as participants became very engaged with the therapy, with desires to discuss it with the therapists and each other in detail, it became clear that the time necessary for working with this group was insufficient. Hence, the therapists and participants sought to extend the intervention. The ethics committee was contacted at the end of the initial 12 sessions to request and an extension. This process took over 20 weeks during which time participants did not receive any active therapy but were able to practise some of the CFT exercises they learned during the first 12 sessions. Consequently, the intervention consisted of the original 12 sessions over 12 weeks (14 weeks in total when 2 weeks break due to holidays considered), a 20-week rest period and then another 13 sessions over 13 weeks. Therefore, the 12-module content was covered in 25 sessions over a total duration of 47 weeks when holidays and break (for ethics) considered.

Practicality

Of the 10 participants who started the CFT group and completed the baseline measures, nine participants completed the first 12 sessions (90%), whilst six participants completed the full 25 sessions (60%), attending an average of 82% of the sessions. One participant withdrew after the first few sessions, another just before the second set of sessions because of work-related reasons, and two withdrew because they were offered alternative support for their needs at the time which may have interfered with the change process. This suggests that the time commitment is acceptable, and most participants were motivated to complete all the sessions.

Adaptation

The intervention was based on a manual currently being developed for group CFT therapy (Gilbert et al., 2016–2022). In this study, the therapists followed the manual with some adaptations partly due to the fact that these clients, as part of the Bipolar Service, had already participated in a programme which draws heavily on CBT, family-focused therapy and mindfulness-based interventions, called Mood on Track. As such, initially, the mindfulness module was touched on briefly and later expanded to introduce opportunities to practise mindfulness and to facilitate understanding of how mindfulness supports compassion. Moreover, some modules took longer than allowed for, therefore due to time constraints the module on assertiveness, apology and forgiveness was not covered.

Integration

This study was undertaken in a specialist Bipolar Service and the intention is that it will have an impact on the regular care offered to people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Participants also indicated how they applied knowledge and practices learnt to everyday life.

Limited-Efficacy Testing

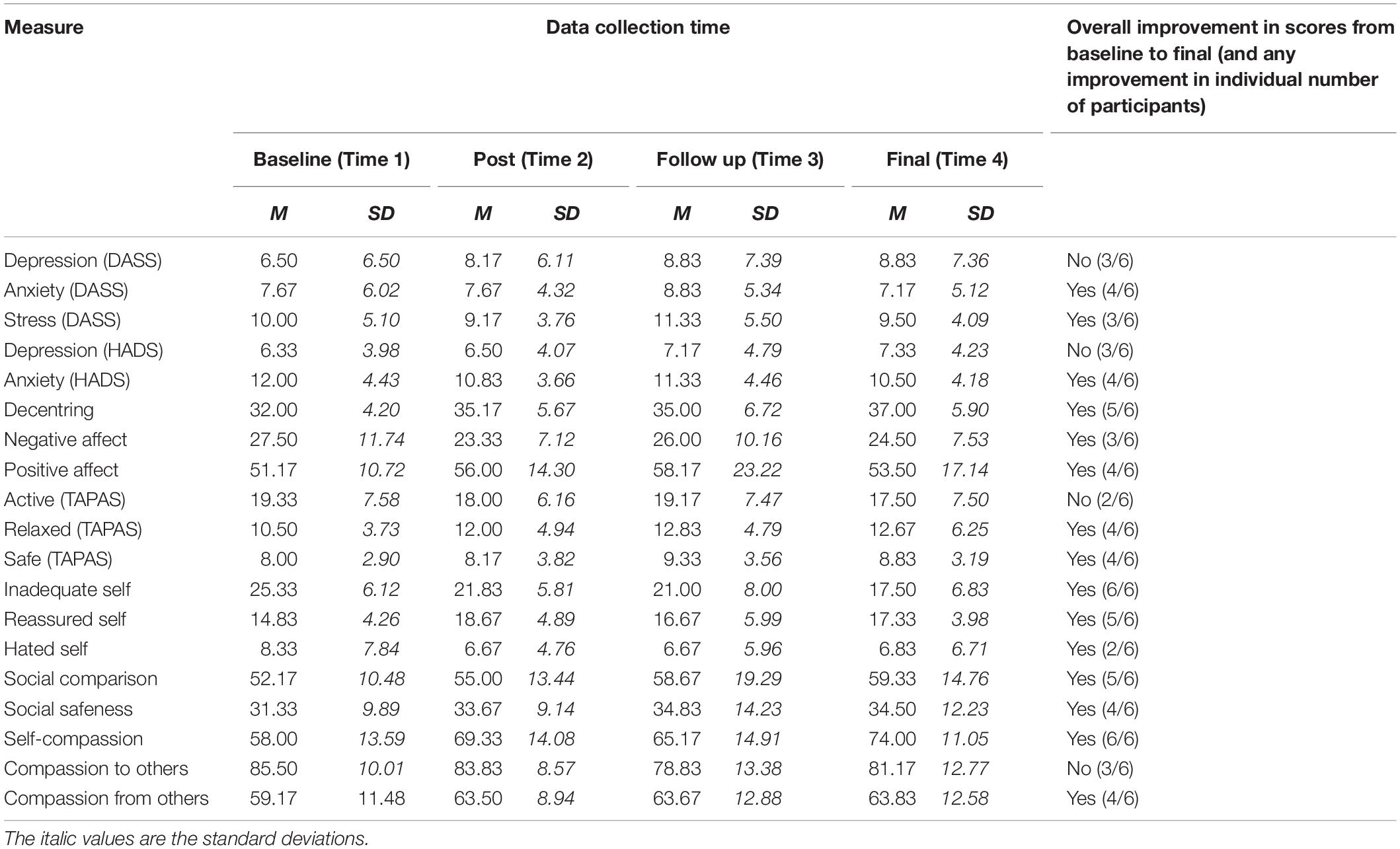

While this was a feasibility study, and not powered enough to detect significant change due to limited sample size, it is worth noting that from visual inspection of individual scores as outlined in Table 2, four of the six participants consistently showed improvements across the majority of self-report measures and maintained them at the final assessment point after all 25 sessions. Improvements in compassion for self and from others, decentring (ability to observe thoughts and feelings as temporary), inadequate self and social comparison were all observed. Two participants showed more mixed results, with improvements on fewer self-reports. Unfortunately, due to COVID-19 pandemic a 1 year follow up was not possible.

Table 2. Mean scores and indicators of improvements for all self-report measures at baseline, post, follow up, and final data collection point.

Moreover, results from the HRV measurements and focus group support the self-report findings and the acceptability of the group.

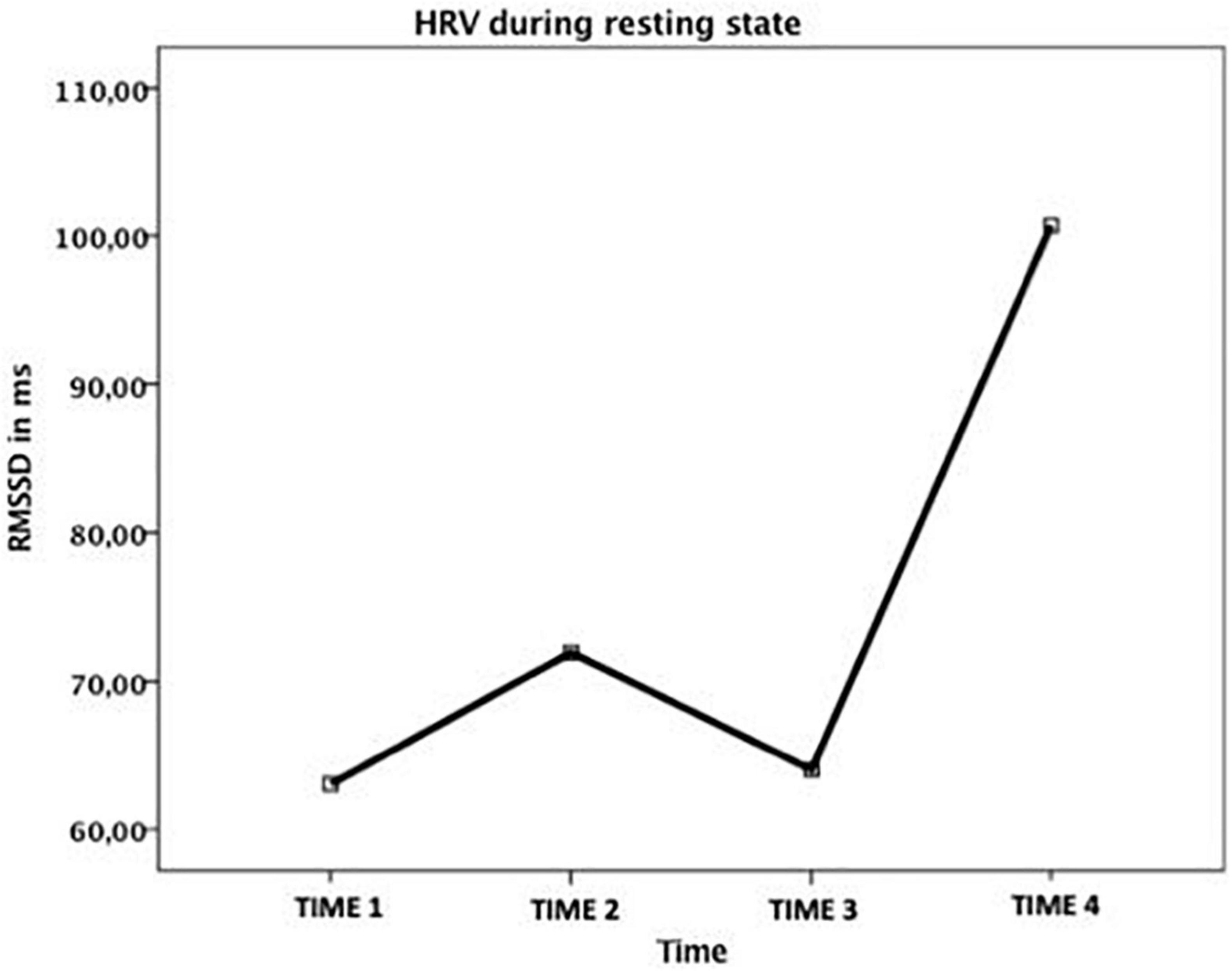

Heart Rate Variability

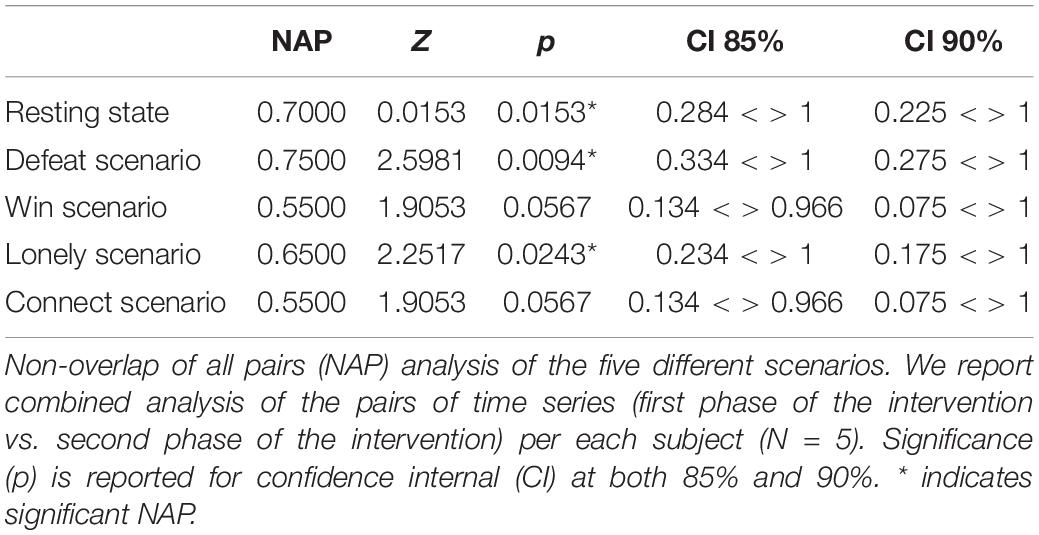

Visual inspection (see Table 3 and Figure 5) suggested an overall improvement in HRV that was particularly evident during the second set of 12 CFT sessions. In particular, resting state HRV slightly improved during the first set of 12 sessions, seemed to decrease during the “break” between the first set and the second set of sessions, and improved again, more strongly, during the second set of sessions.

The overall improvement on HRV was also supported by NAP data analysis, suggesting a significant difference (p < 0.05), in terms of non-overlapping of the pairs of the two phases of the intervention for the five single cases series, for resting HRV and two out of four scenarios: defeat, and lonely (see Table 4). Connect and winning scenarios approached significance (p = 0.0567).

Qualitative Analysis of the Focus Groups

The transcripts were analysed in regard to the questions noted in the methods section. For the most part, we have followed the question and answers but occasionally answers to one question were clearly relevant to another question and therefore we connected those themes. Participant dialogue is given in italics. All names given are pseudonyms.

Question 1: Understanding and Utilising the Evolutionary Model

Participants found the psychoeducation on the evolutionary model extremely helpful and relatable. The concept that many of the emotional textures we experience are the result of the evolution of the mind and therefore are ‘not our fault’ was found particularly de-shaming and enabled a ‘de-centring and standing back’ and more observational orientation to mental events. A key CFT insight is that we have minds built for us not by us and it is that sense in which we understand the concept “it’s not our fault”. This concept highlights the need to learn about the mind in order to take responsibility as noted.

Sophia. “Because it’s your biology and the way that you’re made, it made us then recognize that some of the things that we went through as a bipolar person, weren’t your fault”. Another participant, (Jayne) suggested that this knowledge made them ‘…. feel enlightened, because I felt lighter about things’ and ‘more hopeful, more optimistic’.

Other participants suggested: