- 1College of Sports Science and Technology, Wuhan Sports University, Wuhan, China

- 2Hubei Provincial Key Laboratory of Sports Training Monitoring, Wuhan Sports University, Wuhan, China

- 3Department of Applied Psychology, Wuhan Sports University, Wuhan, China

Objective: The psycho-lexical approach can be effectively used to explore the structure of sports culture. Based on a lexical list of adjective vocabulary reflecting sports culture and through an item analysis, 87 discriminating objectives were selected representing sports culture.

To explore the structure of sports culture from the objectives lexicons.

Methods: Item analysis and factor analysis were adopted to abstract the structure of sports culture.

Results: Through a principal component analysis, a structure of six factors including extroversion-activity, diligence-progression, experience, independence-excellence, enjoyment, and body culture was extracted. Through a second-order factor analysis, a psychological structure of sports culture consisting of six dimensions and 12 factors was extracted, and result of the reliability analysis revealed good Cronbach α coefficient and test–retest reliability coefficient.

Conclusion: The psycho-lexical structure of sports culture can be used to understand structure of sports culture.

Introduction

Sport is a cultural phenomenon on a natural biological basis (Mcpherson et al., 1989). In the era of “sports society,” sports culture, divided into specific sports culture and sportification in general (Grupe, 1994), is perceived as an expression of modernism. With the turn to cultural philosophy, sports culture has become an inspiring topic in the field of sports study. Despite this substantial uptick in interest, however, the rapidly growing literature on sports culture suffers from two notable limitations. First, there is no clear consensus about precisely what the structure of sports culture is (Luschen, 1967; Krawczyk, 1980; Rodesiler, 2021). Relatedly, the broad definition leads to too much research on generality and not enough research on specificity (Lahire, 2008).In the view of this, new theories and specific frameworks must be adopted to transcend existing disciplinary boundaries and to reshape research on sports culture (Takamatsu, 1987; Bilohur and Andriukaitiene, 2020).

Structure of sports culture

A few empirical studies focusing on the structure of sports culture explored the differences and sportification. These studies were mainly carried out on three research aspects. First, on the value and spirit dimension of sports culture. For example, Lee et al. (2000) developed the Youth Sport Values Questionnaire. Obasa and Borry (2019) analyzed the multivalence of the concept of spirit of sport. The more adequate study among them is the personality structure of sports events (Lee and Cho, 2012; De Vries, 2020). Secondly, on the direct exploring of sports culture’s structure. For example, Kaiser et al. (2009) used Structure Dimensional Analysis (SDA) as an innovative approach to understand the representation of culture-related knowledge in sport organizations. Culpepper and Killion (2015) applied the symbolic analysis to identify the general cultural categories of sports (i.e., movement forms, rules, and values). Thirdly, on the sub-sector of sports culture. For example, regional features of sports culture (Adedeji, 1979; Hargreaves, 1997; Sibaja, 2015), psychometric properties of sport participation (Beaton et al., 2011; Casper et al., 2011) and the structural properties of sport teams culture (Kao and Cheng, 2005; McEwan, 2017) were studied. However, previous studies have not been sufficient to reveal the structure of sports culture, which identifies the cultural function of sport and legitimizes it as a social institution (Kono, 1997). Therefore, there is a need to further investigate the conceptual system, measurement tools, and structural features of sports culture.

The lexical paradigm

The psycho-lexical approach, which uses language to study culturally loaded words, is based on the assumption that the most important individual difference have been encoded into the natural language (Allport and Odbert, 1936). Based on studies that use the lexical paradigm, by following a standard procedure to extract the most common trait-related words from sufficiently large lexicon, and by asking respondents to indicate the extent to which these words represent their, or an acquaintance’s–personality, researchers across the world have been able to arrive at a near consensus about the main dimensions of personality (Goldberg, 1981). The lexical approach has been applied to several psychology domains, such as values (De Raad et al., 2017; Wilkowski et al., 2021), emotions (Macheta and Gorbaniuk, 2020), interpersonal interactions (Strachan et al., 2009), and communication styles (Labasse, 2001; De Vries et al., 2009), but it has rarely been applied to the sport psychology and sports culture domain. As noted above, such a lexical study may provide provides a way to explore the structure of sports culture.

The current study

The aim of our study is to uncover the psycho-lexical structure of sports culture. The lexical study on social scientific domain was conducted in three phases. In the first phrase, a preliminary selection of adjectives that pertained to sports culture was made. In the second phrase, a further reduction of the list of adjectives was made base on a panel of experts. In the third phrase, self-ratings were obtained on the list of adjectives selected. Guo and Qi (2017), by using the psychological vocabulary method, a total of 372 college students were investigated, and a total of 694 typical adjectives as carriers representing the three levels of people, things and incidents in sports culture were collected. After synonym classification and frequency sorting, 87 adjectives representing sports culture were obtained which could provide a basis for the next step to confirm the structure of sports culture. With regard to this research, the Chinese psycho-lexical project in the sports domain is discussed in the present study. The extracted psychological structure of sports culture would possibly pave the way for further empirical studies.

Materials and methods

Participants

The sample 1 (n = 128 college students, 72 males and 56 females, Mage = 19.11, SD = 1.54) for item analysis were randomly selected from a university in Wuhan, China.

The sample 2 (n = 505 college students, 298 males and 207 females, Mage = 19.20, SD = 1.62) for factor analysis were randomly selected from two universities in Wuhan, China.

The sample 3 (n = 223 college students, 115 males and 107 females, Mage = 19.34, SD = 1.52) for test–retest reliability analysis were randomly selected from a university in Wuhan, China.

The trained graduate students of psychology explained the requirements of the survey using standard instructions emphasizing the authenticity, independence, and integrity of all answers.

Materials and procedure

Materials

“Survey of sports culture carriers” phase: by adopting survey of sports culture’s carrier, participants were asked to give specific examples of sports culture carriers from three categories: people, events and objects of sports.

“Collection of sports culture adjectives” phase: participants were asked to anthropomorphize the listed sports culture carriers and then describe their qualities in free association, resulting in 694 adjectives.

“Lexical screening of sports culture adjectives” phase: The more frequently the vocabulary is used, the more important the feature being described is. Therefore, the third step of vocabulary sorting is to perform frequency calculation on the obtained 124 vocabularies. After removing the bottom 27% low-frequency words in the lexical frequency ranking, and confirmed by two experts in linguistics, 91 basic vocabularies were obtained.

“Measurement of the Significance of Sports Culture Adjectives” phase: The significance mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) of the 91 adjectives were calculated. The overall score is distributed in negative skewness, which indicated that the respondents have a good understanding of the meaning of these adjectives. After excluding the four adjectives with low meaning and too large standard deviation: bullying, elitist, triumphant, and restrained, the final 87 adjectives were obtained (Guo and Qi, 2017).

Procedure

The 87 selected adjectives were first subjected to an Item Analysis. Factor Analysis and Reliability Analysis were then performed on those with significant discriminability.

Data processing

According to the research requirements,SPSS21.0 software was employed to record data and for data processing.

Results

Item analysis

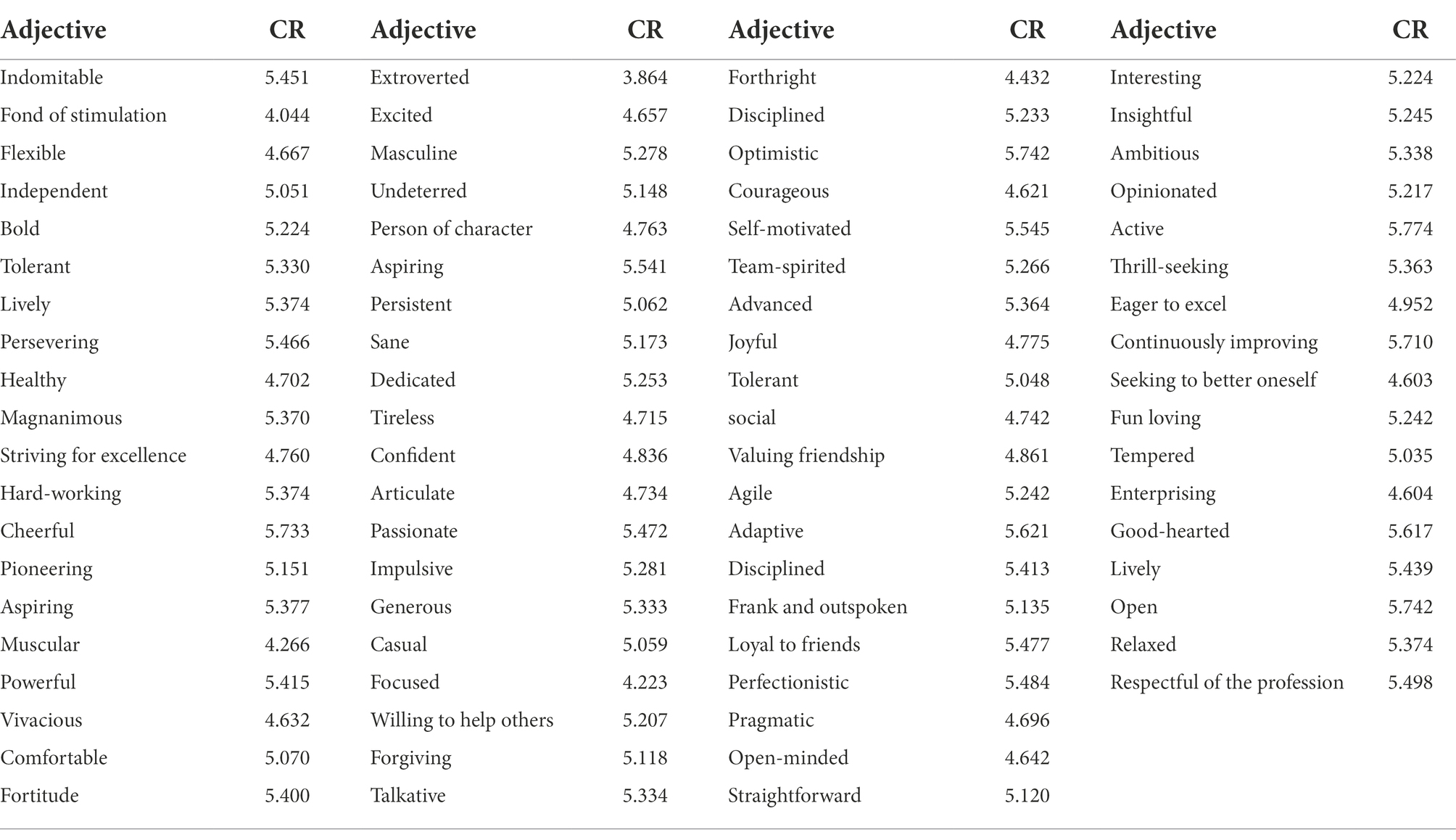

To test the feasibility of revealing sports culture structures from the selected 87 adjectives, each adjective was first subjected to an item analysis. The critical ratio (CR) was employed as an index for item discrimination analysis. According to the t-test results, 10 adjectives (energetic, harmonious, stable, attentive, friendly, imaginative, promising, arrogant, conceited, and self-reliant) with significance levels of greater than 0.01 were eliminated. Finally, 77 adjectives with significant discriminability were obtained (Table 1).

Principal component analysis

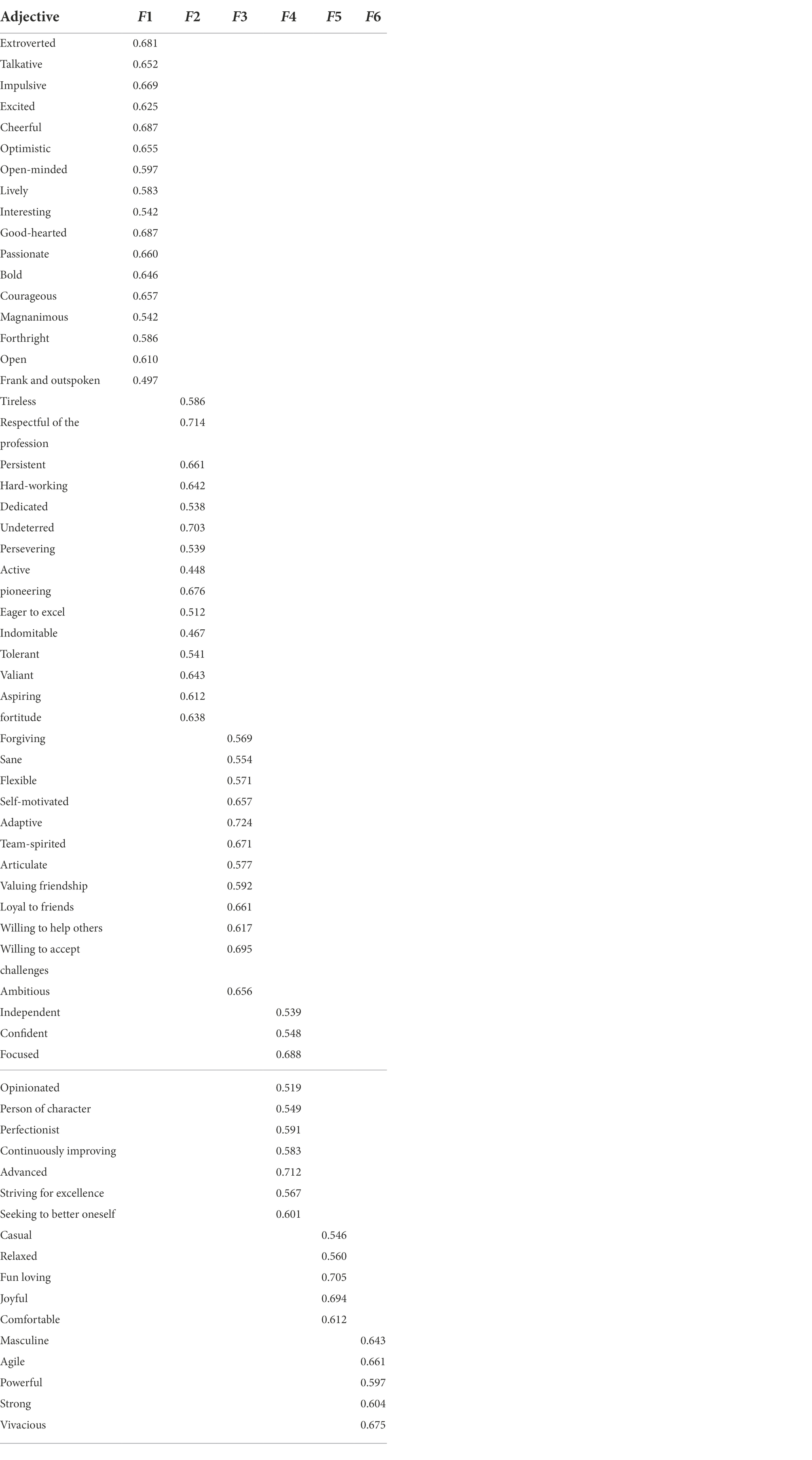

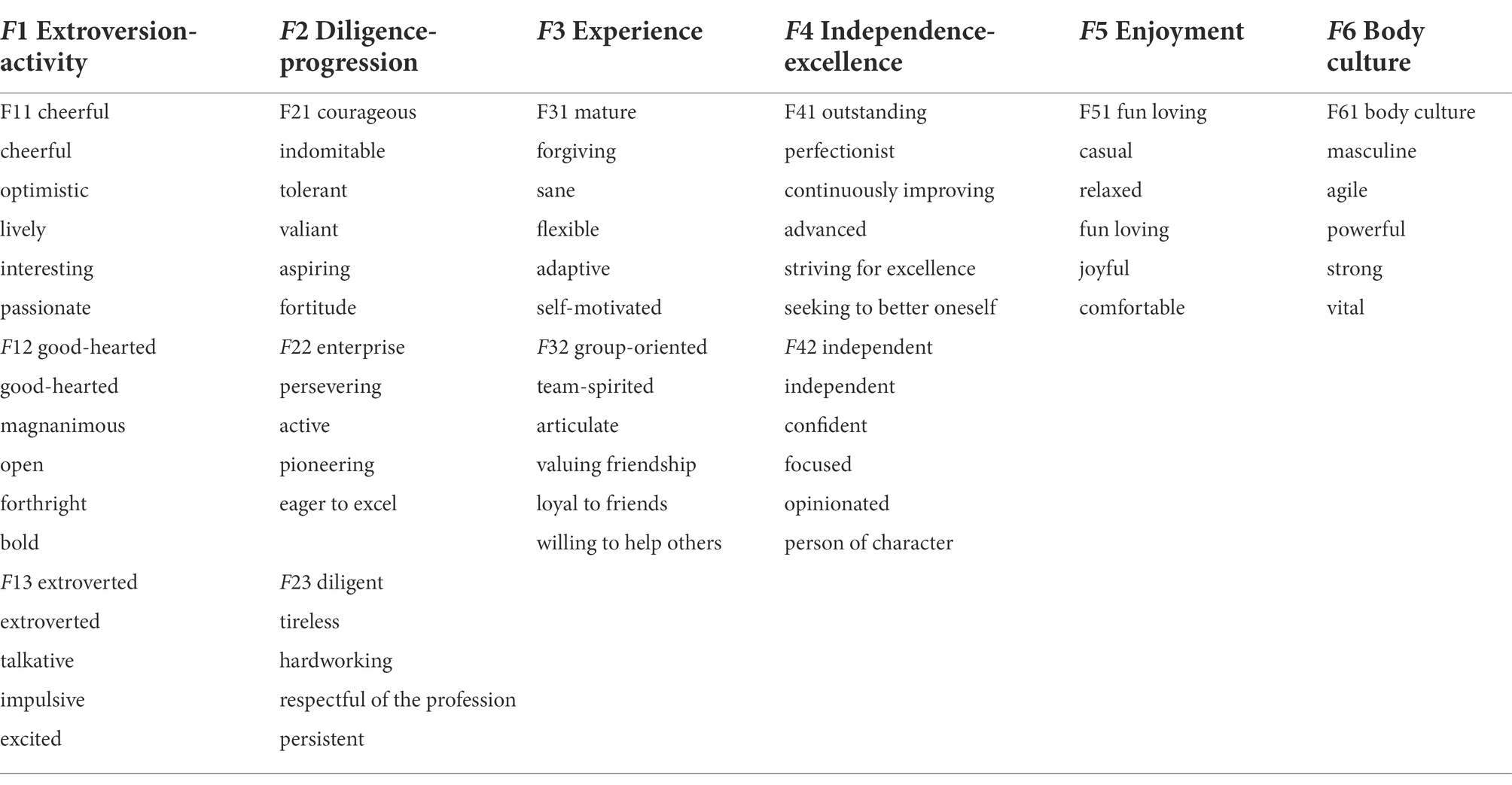

Based on the item analysis results, the 77 remaining items were subjected to Bartlett’s test, which generated a value 2460.76 (p<0.01) and a KMO of 0.89. A principal component analysis was performed on the 77 adjectives. First, items with loads of less than 0.3 were eliminated, including muscular, tempered, disciplined, pragmatic, insightful, and fond of stimulation. Second, items with multiple comparable loads were removed, including social, healthy, open-minded, ambitious, and enterprising. The remaining items could be explained by six main factors with an explained variance of 57.69%. As shown in Table 2, 17 items were identified as factor F1 (extroversion-activity), 15 items were identified as factor F2 (diligence-progression), 12 items were identified as factor F3 (experience), ten items were identified as factor F4 (independence-excellence), five items were identified as factor F5 (enjoymen)t, and five items were identified as factor F6 (body culture),and corresponding explained variances were measured as 12.90, 11.64, 10.15, 9.27, 7.01, and 6.69%, respectively.

Second-order factor analysis

The six factors were analyzed further. Based on the items included in each factor, the first four items of each factor were subjected to second-order factor analysis. Factors with characteristic roots of greater than one were extracted (Tables 3–6). Analyses were performed using the above-described procedure.

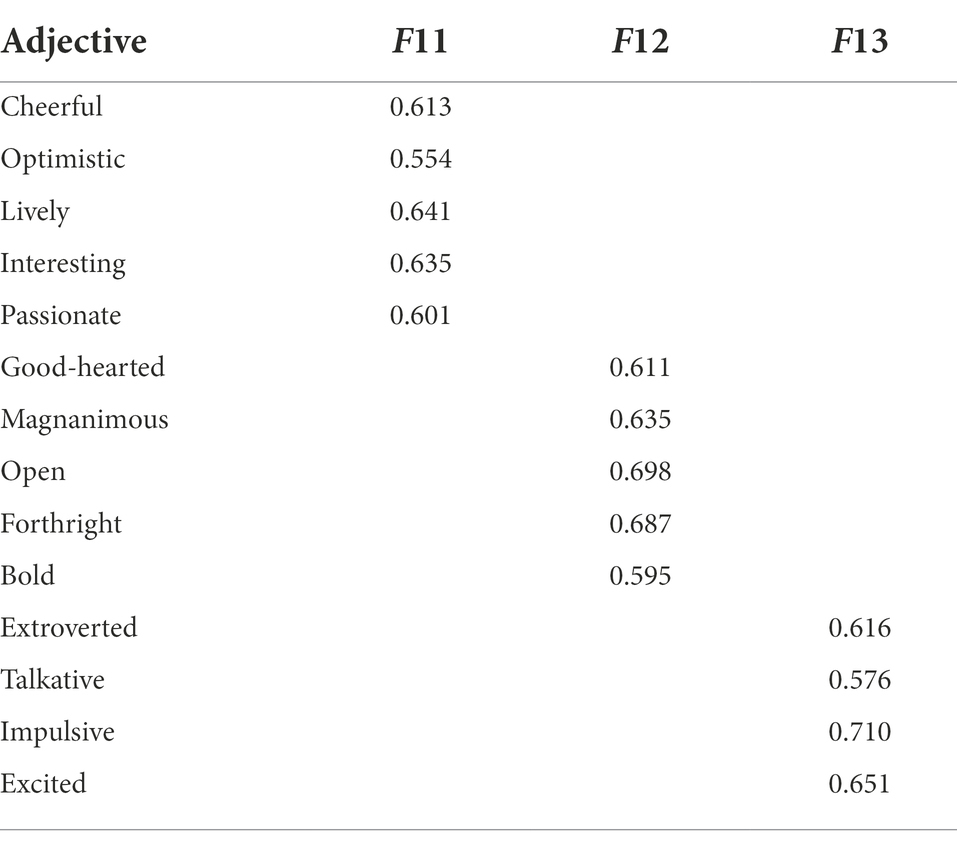

A factor analysis was performed on the 17 items of factor F1. Three second-order factors were used to explain 61.78% of the total variance: F11 (cheerful): cheerful, optimistic, lively, interesting, and passionate; F12 (good-hearted): good-hearted, magnanimous, open, forthright, and bold; and F13 (extroverted): extroverted, talkative, impulsive, and excited; the three second-order factors of F1, respectively, explained 21.87, 20.06, and 19.93% of the variance. Three items, i.e., open-minded, courageous, and frank and outspoken, were eliminated due to the presence of multiple loads (Table 3).

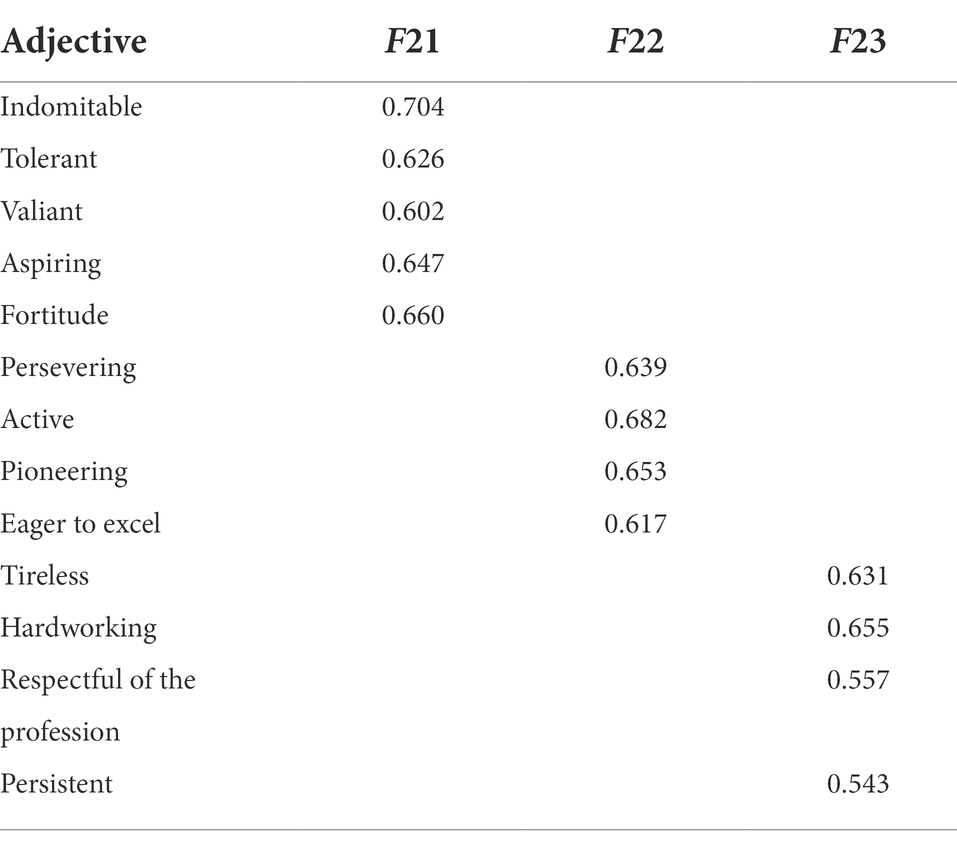

A factor analysis was performed on the 15 items of factor F2. Three second-order factors were found to explain 53.25% of the total variance: F21 (courageous): indomitable, tolerant, valiant, aspiring, and fortitude; F22 (enterprise): persevering, active, pioneering, and eager to excel; and F23 (diligent): tireless, hardworking, respectful of the profession, and persistent; the three second-order factors of F2, respectively, explained 19.72, 16.96, and 16.56% of the variance. Two items, i.e., dedicated and dauntless, were removed due to the presence of multiple loads (Table 4).

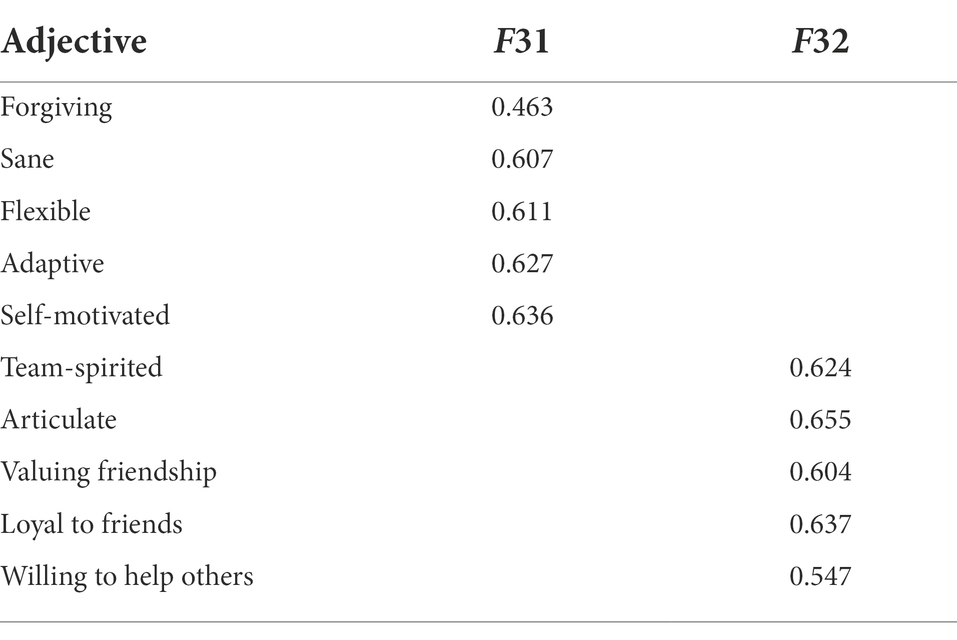

A factor analysis was performed on the 12 items of factor F3. Two second-order factors were found to explain 46.39% of the total variance: F31 (mature): forgiving, sane, flexible, adaptive, and self-motivated; and F32 (group-oriented): team-spirited, articulate, valuing friendship, loyal to friends, and willing to help others; the two second-order factors of F3, respectively, explained 23.87 and 22.52% of the variance(Table 5).

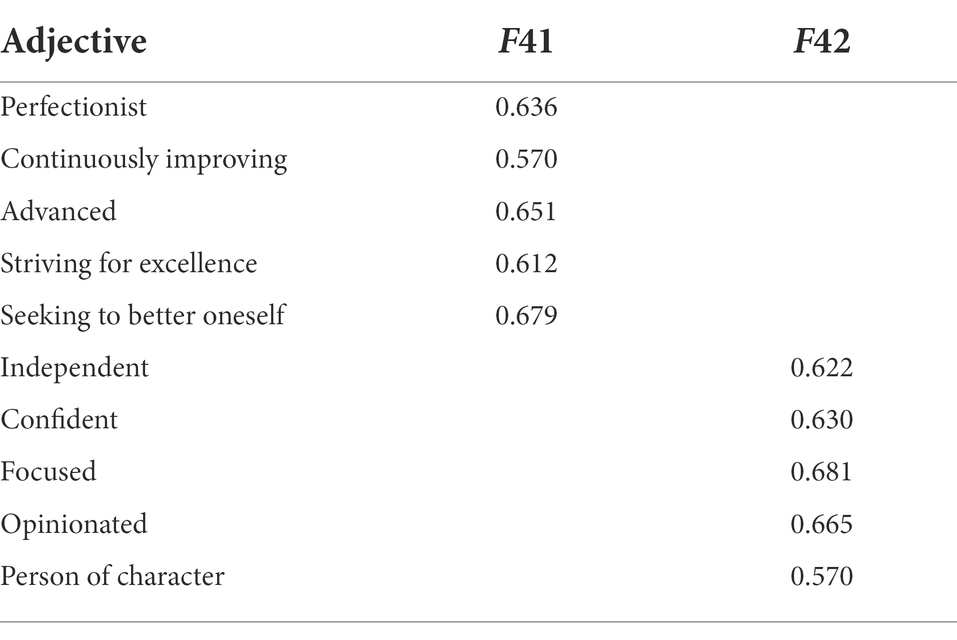

A factor analysis was performed on the 10 items of factor F4. Two second-order factors were found to explain 58.16% of the total variance: F41(outstanding): perfectionist, continuously improving, advanced, striving for excellence, and seeking to better oneself; and F42 (independent): independent, confident, focused, opinionated, and person of character; the two second-order factors of F4, respectively, explained 29.47 and 28.69% of the variance (Table 6).

From the first- and second-order factor analyses, the psychological structure of sports culture was mostly confirmed (Table 7).

Table 7. Composition and second-order factor items of the psychological structure of sports culture.

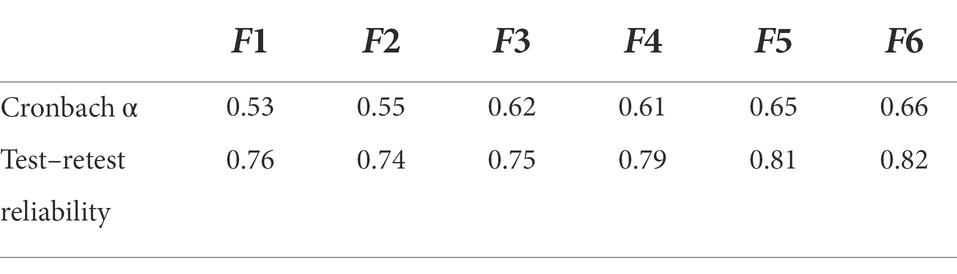

Reliability analysis

Cronbach α coefficients of the six main factors were found to range from 0.53 to 0.66. The high degree of variance in the adjectives denotes the homogeneous reliability of the structure. Six weeks later, a retest was performed on 93 undergraduate students. The test–retest reliability level was between 0.74 and 0.82 (Table 8).

Discussion

The sports culture is a complex, multidimensional phenomenon. The conceptual contents of its structural components lack a common perspective. In other words, different theories are premised on different concepts. Therefore, other structures of sports culture must also be explored through the implementation of other theoretical frameworks and approaches. This paper argues that sports culture, as a social phenomenon, is an integral part of the culture and that its systemic formative factors are sporting values and individual attitudes towards sport and physical activity (Seppnen, 1989). Human physical culture results from the internalizing process of the cultural and educational potential, values, and techniques of the sport, the accumulation of human experience of physical culture and physical activity, and the discovery of individual consciousness in physical culture and physical activity. From this perspective, it is possible to configure the components of sporting culture through the study of psychological structures.

The structure of complex phenomena, which also refers to the human personality, represents a combination of different elements, layers, and certain interactions. The structure of sports culture represents some personality and social values (Hughson, 2009). For example, Korovin (2016) used physical adaptation, cognitive-intellectual, and axiology to construct the components of Professional Physical Culture of Personality(PPCP). The model of 6 dimensions-12 factors identified through this study shows that sports culture is not only a body culture but also a psychological and social culture, demonstrating both the rationality of Apollonian culture and the romance of Dionysian culture, which seeks not only excellence but also health. The spirit of personality and the formation of values is fundamental to all the elements of activity in sports culture because the relationship of human values which runs through its elements, is the standard core of personality, the backbone elements of sports culture, and the determination to the specific expression of the other elements. Also, the sport has a subjective and universal structure that organizes sporting activities for specific competitions and gives them a clear meaning.

The clusters and factors extracted were meaningful and interpretable. However, there was still some limitation in this study. First, the research mainly relied on participants’ self-reported or hypothetical situational responses, and their relevance to actual behavior needs to be replicated (Baumeister et al., 2007). Second, the empirical research on the structure of sports culture is still in its infancy, and the validity of the 6-dimensional 12-factor model developed through a psychological normative process needs to be further expanded and validated. Third, word association is a critical tool for identifying intrinsic values (Angleitner et al., 1990). And vocabulary sorting by two linguistic experts might be subjective. It is important to note that vivid adjectives obtained through everyday conversation can vary greatly, which requires increased vocabulary through other means to reduce variation in future studies. Finally, cross-cultural research should be assessed by using the structural approach and by comparing the position of these factors in the field of research and in the field of social practice.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the patients/participants or patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

XH and WW were responsible for the design of the study. YG and NY were responsible for data collection and essay writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project is financially supported by the 14th Five-Year-Plan Advantageous and Characteristic Disciplines (Groups) of Colleges and Universities in Hubei Province for Exercise and Brain Science from Hubei Provincial Department of Education in China, Major Project for Prosperity of Philosophy and Social Sciences in Hubei Province (21ZD096), Ministry of Education Project of Research of Humanitarian (19YJC890013) and Young and Middle-aged Scientific Research Team of Wuhan Sports University in 2021 (21KT06).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants in the study and the members of our research group for their help.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adedeji, J. A. (1979). Social and cultural conflict in sport and games in developing countries. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 14, 81–88. doi: 10.1177/101269027901400105

Allport, G. W., and Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait-names: a psycho-lexical study. Psychol. Monogr. 47, i–171. doi: 10.1037/h0093360

Angleitner, A., Ostendorf, F., and John, O. P. (1990). Towards a taxonomy of personality descriptors in German: a psycho-lexical study. Eur. J. Personal. 4, 89–118. doi: 10.1002/per.2410040204

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., and Funder, D. C. (2007). Psychology as the science of self-reports and finger movements: whatever happened to actual behavior? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2, 396–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00051.x

Beaton, A. A., Funk, D. C., Ridinger, L., and Jordan, J. (2011). Sport involvement: a conceptual and empirical analysis. Sport. Manag. Rev. 14, 126–140. doi: 10.1016/j.smr.2010.07.002

Bilohur, V., and Andriukaitiene, R. (2020). Sports culture as a means of improving the integrity of sports personality: philosophical cultural and anthropological analysis. Humanit. Stud. 83, 136–152. doi: 10.26661/hst-2020-6-83-10

Casper, J. M., Bocarro, J. N., Kanters, M. A., and Floyd, M. F. (2011). Measurement properties of constraints to sport participation: a psychometric examination with adolescents. Leisure. Sci. 33, 127–146. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2011.550221

Culpepper, D., and Killion, L. (2015). 21Century sport: micro or macro system? Res. Q. Exercise Sport. 86, A27–A28.

De Raad, B., Timmerman, M. E., Morales-Vives, F., Renner, W., Barelds, D. P. H., and Van Oudenhoven, J. P. (2017). The psycho-lexical approach in exploring the field of values: a reply to Schwartz. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 48, 444–451. doi: 10.1177/0022022117692677

De Vries, R. E. (2020). The main dimensions of sport personality traits: A lexical approach. Front. Psychol. 11:2211. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02211

De Vries, R. E., Bakker-Pieper, A., Siberg, R. A., Van Gameren, K., and Vlug, M. (2009). The content and dimensionality of communication styles. Commun. Res. 36, 178–206. doi: 10.1177/0093650208330250

Goldberg, L. (1981). “Language and individual differences: the search for universals in personality lexicons,” in Review of Personality and Social Psychology. ed. L. Wheeler (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publication), 141–165.

Grupe, O. (1994). Sport and culture-the culture of sport. J. Jpn. Soc. Sports. Ind. 4, 39–53. doi: 10.5997/sposun.4.39

Guo, Y. B., and Qi, C. Z. (2017). Psycho-lexical research on sports culture. J. Qufu Norm. Univ. 43, 115–118. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5337.2017.1.115

Hargreaves, J. (1997). Women's sport, development, and cultural diversity: the south African experience. Women. Stud. Int. Forum. 20, 191–209. doi: 10.1016/S0277-5395(97)00006-X

Hughson, J. (2009). Book review: Tony Schirato, understanding sports culture. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 12, 123–125. doi: 10.1177/13675494090120010703

Kaiser, S., Engel, F., and Keiner, R. (2009). Structure-dimensional analysis—an experimental approach to culture in sport organizations. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 9, 295–310. doi: 10.1080/16184740903024045

Kao, S. F., and Cheng, B. S. (2005). Assessing sport team culture: qualitative and quantitative approaches. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 15, 245–251. doi: 10.1142/S0218127405012144

Kono, K. (1997). A study of the structure of sport as a symbolic form: centered on its generation, function, and development. Res. Phys. Educ. 42, 128–141. doi: 10.5432/jjpehss.kj00003391570

Korovin, S. S. (2016). The structure and content of the professional physical culture of the personality. Samara J. Sci. 5, 171–174. doi: 10.17816/snv20161309

Krawczyk, Z. (1980). Sport and culture. Int. Rev. Soc. Sport. 15, 7–18. doi: 10.1177/101269028001500302

Labasse, B. (2001). From linguistics to communications didactics: the case of lexicology. Iral-Int. Rev. Appl. Li. 39, 217–243. doi: 10.1515/iral.2001.003

Lahire, B. (2008). The individual and the mixing of genres: cultural dissonance and self-distinction. Poetics 36, 166–188. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2008.02.001

Lee, H. S., and Cho, C. H. (2012). Sporting event personality: scale development and sponsorship implications. Int. J. Sport. Mark. Spo. 14, 46–63. doi: 10.1108/IJSMS-14-01-2012-B005

Lee, M. J., Whitehead, J., and Balchin, N. (2000). The measurement of values in youth sport: development of the youth sport values questionnaire. J. Sport. Exercise. Psy. 22, 307–326. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00195

Luschen, G. (1967). The interdependence of sport and culture. J. Int. Soc. Sports. 2, 127–141. doi: 10.1177/101269026700200109

Macheta, K., and Gorbaniuk, O. (2020). The lexical approach to the taxonomy of emotions. Annales 33, 21–32. doi: 10.17951/j.2020.33.3.21-32

Mcpherson, B. D., Curtis, J. E., and Loy, J. W. (1989). The Social Significance of Sport: An Introduction to the Sociology of Sport. New York, NY: Human Kinetics.

Obasa, M., and Borry, P. (2019). The landscape of the “Spirit of sport”. J. Bioethic. Inq. 16, 443–453. doi: 10.1007/s11673-019-09934-0

Rodesiler, L. (2021). Controversies, rivalries, and representation: sports culture as a site for research and inquiry. J. Adolesc. Adult. Lit. 65, 55–63. doi: 10.1002/jaal.1158

Seppnen, P. (1989). Competitive sport and sport success in the Olympic games: a cross-cultural analysis of value systems. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 24, 275–282. doi: 10.1177/101269028902400401

Sibaja, R. (2015). Sports culture in Latin American history. J. Soc. Hist. 23, shv110–shv210. doi: 10.1093/jsh/shv110

Strachan, L., Cté, J., and Deakin, J. (2009). An evaluation of personal and contextual factors in competitive youth sport. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 21, 340–355. doi: 10.1080/10413200903018667

Takamatsu, M. A. (1987). Study of the structure of sport as a cultural form. Jpn. J. Sport Educ. Stud. 7, 17–25. doi: 10.7219/jjses.7.2_17

Keywords: sports culture, psycho-lexical hypothesis, psychological structure, factor analysis, psychological adjectives

Citation: Guo Y, Ye N, Hong X and Wang W (2022) The psycho-lexical structure of sports culture. Front. Psychol. 13:894694. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.894694

Edited by:

Erin M. Buchanan, Harrisburg University of Science and Technology, United StatesReviewed by:

Lekhnath Sharma Pathak, Tribhuvan University, NepalMohamad Djavad Akbari Motlaq, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Malaysia

Nermina Cordalija, University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Copyright © 2022 Guo, Ye, Hong and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaobin Hong, NDcxNzgwNjkzQHFxLmNvbQ==; Wenjing Wang, MjAyMTAyMUB3aHN1LmVkdS5jbg==

Yuanbing Guo

Yuanbing Guo Na Ye3

Na Ye3 Xiaobin Hong

Xiaobin Hong Wenjing Wang

Wenjing Wang