- North Sichuan Medical College, Nanchong, China

Background: To investigate the association between facial negative physical self, social anxiety, rumination, and self-compassion among college students in western China.

Methods: A questionnaire was used to conduct an online survey of 1, 178 students from a university in western China through convenience sampling using the Self-Compassion Scale, the Ruminative Response Scale, the Negative Physical Self Scale-facial appearance sub-scale and the Interaction Anxiousness Scale.

Results: In the mediation model, the total predictive effect of facial negative physical self on social anxiety was significant (B = 0.46, t = 17.66, p < 0.01), and the mediating effect of facial negative physical self on social anxiety accounted for 48. 1% of the total effect; self-compassion moderated the effect of rumination on social anxiety (B = –0.06, t = 3.00, p < 0.01).

Conclusion: Facial negative physical self affects the level of social anxiety of college students through rumination, and self-compassion regulates the effect of rumination on social anxiety. Students should be encouraged to increase their level of self-compassion or be provided with self-compassion intervention training, which can help reduce social anxiety.

1 Introduction

Today’s college students are in the flourishing period of adolescence, facing a new and independent interpersonal environment. On the one hand, the motivation and driving force to try to socialize are increasing; on the other hand, they do not know how to establish good interpersonal relationships, which makes social anxiety increasingly a common mental health problem of contemporary college students (Peng, 2004). According to the survey in China, 45.7% of college students have experienced social anxiety (Li et al., 2019). A meta-analysis on the global prevalence of social anxiety disorder reported prevalence rates of 8.3% in adolescents and 17% in youth populations (Salari et al., 2024). In recent years, mental health assessments among college students have revealed that a significant proportion of students experience severe social anxiety, which exerts multiple adverse effects on their well-being (Dong et al., 2024). On the one hand, mild social anxiety can lead to diminished quality of interpersonal relationships, reduced subjective well-being (Lacombe et al., 2024; Öztekin, 2024), heightened loneliness (Sun and Liu, 2018), and an increased likelihood of addictive behaviors (Huang et al., 2021). On the other hand, severe social anxiety may even contribute to clinical depression, suicidal ideation, and self-harm behaviors (Zhang and Zhou, 2018). Therefore, investigating social anxiety among college students is critical for safeguarding their mental health.

1.1 Theoretical framework

According to the Cognitive Behavioral Model of Social Phobia (CBMSP), the emotional responses of individuals with social anxiety are caused by non-objective and negative beliefs and perceptions (Clark and Wells, 1995). In recent years, with the widespread use of filters and P-picture software in social media, individuals’ requirements for their appearance have become higher and higher compared with the perfect image of individuals after filters, and appearance anxiety has become more common. Facial negative physical self originates from Negative Physical Self (NPS), also termed body image disturbance, which refers to an individual’s negative affective, cognitive, and behavioral responses toward their own body (Davison and McCabe, 2005). Chinese scholar Chen (2003) identified five dimensions of NPS (general, overweight, underweight, facial appearance, and short stature). As a subdimension of NPS, facial negative physical self specifically denotes negative self-cognitions about one’s facial features, encompassing the detrimental cognitive evaluations, emotional reactions, and behavioral regulations individuals develop regarding their facial appearance (Chen, 2003). Therefore, according to the CBMSP, facial negative physical self functions as a form of negative self-cognition, often play a critical role in shaping interpersonal interactions, with facial negative physical self identified as a major predictor of social anxiety (Pawijit et al., 2019). Existing research has primarily focused on the relationship between general negative physical self and social anxiety, largely overlooking the differential impacts of various NPS dimensions on social anxiety. Given that facial appearance serves as one of the most immediate and crucial factors in interpersonal interactions, this study specifically examines the influence of facial negative physical self on social anxiety and its underlying psychological mechanisms.

In exploring the relationship between facial negative physical self and social anxiety among college students, rumination—a maladaptive cognitive regulation strategy (Zhao and Zhang, 2024)—refers to an individual’s persistent focus on negative self-aspects and repetitive analysis of their causes and consequences, without actively addressing or resolving them (Watkins and Roberts, 2020). Individuals with higher levels of rumination tend to dwell excessively on negative social interactions and engage in harsh self-criticism regarding their behavioral performance, thereby amplifying anxiety in interpersonal contexts and contributing to social anxiety (Modini and Abbott, 2017). Consequently, individuals with higher levels of facial negative physical self are more susceptible to rumination due to excessive preoccupation with their negative self-perceptions, ultimately leading to social anxiety.

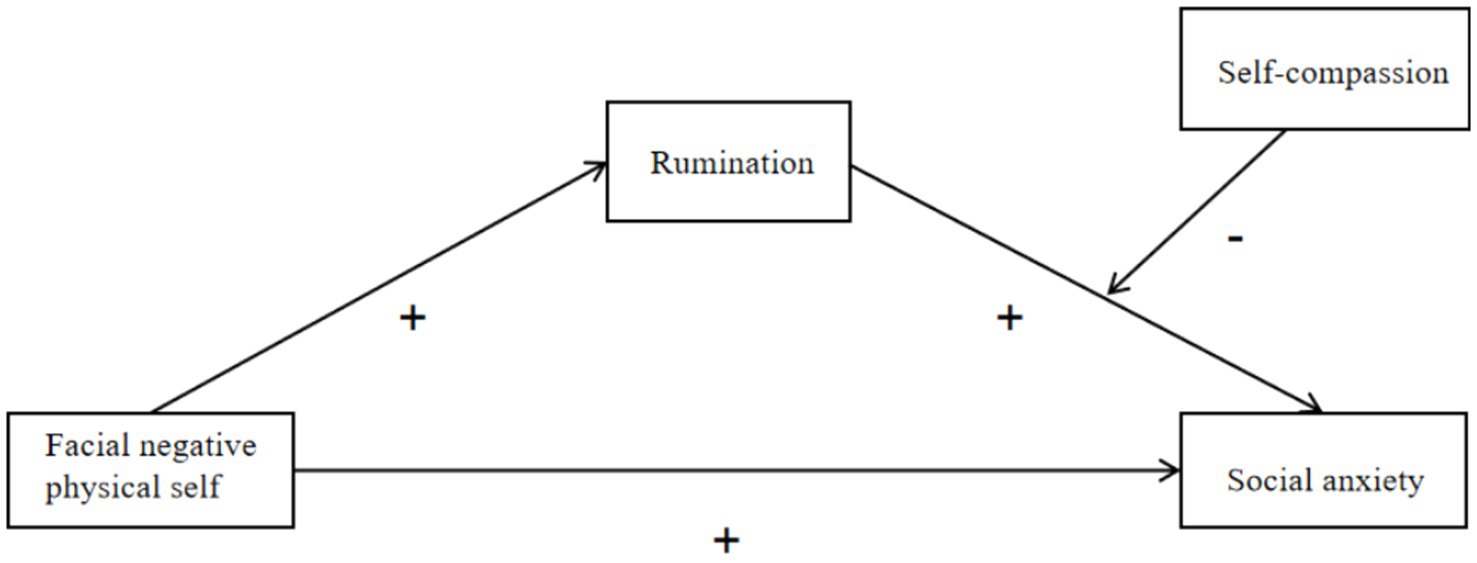

Previous studies have shown that self-compassion, as a positive and receptive emotion regulation strategy, has been found to have a positive impact on rumination (Bugay-Sökmez et al., 2023). In addition, previous studies on college students' social anxiety found that the core feature of social anxiety is mainly fear of negative evaluation (Swee et al., 2021), which is closely related to the concept of self-compassion. Neff (2003) proposed that self-compassion means that individuals are not hard on themselves when facing deficiencies, failures and sufferings and are full of kindness and care for themselves. Individuals with high self-compassion can make more accurate self-assessments in social situations, are less swayed by negative external evaluations (Bugay-Sökmez et al., 2023), and are better able to accept their shortcomings, thus directly countering the core characteristics of social anxiety. In addition, although the concept of self-compassion as a good way of cognitive regulation has not been proposed for a long time, numerous empirical and review studies on self-compassion have shown that self-compassion has a good effect on improving individual negative psychological states (Neff, 2023; Póka et al., 2024). For example, studies have shown that self-compassion is associated with reduced negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, and stress (Blackie and Kocovski, 2018). Therefore, we believe that when individuals cause rumination due to negative physical self-appearance, individuals with a higher level of self-compassion can alleviate social anxiety caused by rumination.Therefore, this study aims to explore the relationship between the facial negative physical self and social anxiety and discuss the roles of rumination and self-compassion in the relationship to build an internal mechanism model of the relationship between the facial negative physical self and social anxiety.

1.2 The relationship between facial negative physical self and social anxiety

Previous studies have demonstrated a significant association between facial negative physical self and social anxiety (IzgiçF et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2021; Cai et al., 2024; Wan et al., 2024). Facial negative physical self encompasses negative emotional (e.g., shame, frustration), cognitive (e.g., dissatisfaction, desire for change), and behavioral (e.g., avoidance, concealment) responses toward one’s body (Chen, 2003). Consequently, when individuals are dissatisfied with their appearance, they tend to excessively focus on their looks, movements, and behaviors in social situations, perceiving that their appearance is under scrutiny by others (Menzel et al., 2010). Moreover, appearance-related insecurity may lead to overestimation of negative evaluations from others during interpersonal interactions, heightening negative emotions and resulting in tendencies toward social anxiety and social avoidance (Zhu et al., 2021). These findings are further supported by empirical research (Zhu et al., 2021; Cai et al., 2024), which indicates that individuals with facial negative physical self frequently experience anxiety and exhibit reluctance to engage in social relationships (Zhu et al., 2021). Negative self-perceptions of one’s body can also adversely affect interpersonal mental states, such as anxiety and depression (Bornioli et al., 2021). Additionally, dissatisfaction with body image has been shown to trigger fear of negative evaluation (Willemse et al., 2023), a core feature of social anxiety. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that negative physical self (including facial negative physical self) serves as a positive predictor of social anxiety and is positively correlated with it. The present study proposes Hypothesis 1: Facial negative physical self positively predicts social anxiety among college students (H1).

1.3 The mediating role of rumination

We propose that negative physical self of college students may directly influence social anxiety, as well as indirectly affect it through rumination. First, research on body dissatisfaction indicates that it often triggers social comparison, which significantly predicts increased rumination (Feinstein et al., 2013). This heightened rumination, in turn, exacerbates body image dissatisfaction (Etu and Gray, 2010; Rivière et al., 2018). Empirical studies have shown that individuals who hold stronger facial negative physical self tend to exhibit lower self-acceptance of their appearance and are more vulnerable to negative emotions triggered by appearance-related insecurity (Zhu et al., 2021), thereby increasing their susceptibility to engage in ruminative thinking characterized by persistent and repetitive negative patterns (Neff, 2009). Therefore, we hypothesize that facial negative physical self may also contribute to increased rumination. Previous research has indicated that individuals with elevated levels of rumination tend to dwell excessively on negative social interactions and engage in harsh self-criticism regarding their behavioral performance, which exacerbates anxiety in interpersonal contexts and leads to social anxiety (Modini and Abbott, 2017). Furthermore, numerous empirical studies have consistently demonstrated a significant positive correlation between rumination and social anxiety (Brozovich et al., 2015; Abdollahi, 2019; Elhai et al., 2018; Valena et al., 2015; Edgar et al., 2024). Based on this evidence, the present study proposes Hypothesis 2: Rumination mediates the relationship between facial negative physical self and social anxiety (H2).

1.4 The regulating role of self-compassion

Self-compassion refers to an individual’s positive and caring attitude toward themselves when confronted with failures and personal shortcomings. According to Neff (2003), self-compassion stems from the cultivation of mindfulness, self-kindness, and a sense of common humanity. Consequently, individuals with high self-compassion are more likely to accept their imperfections and approach challenges by neither avoiding nor over-identifying with their issues, thereby mitigating ruminative thinking (Wasylkiw et al., 2012). Studies suggest that enhancing self-compassion serves as a potential protective strategy for populations prone to ruminative cognitive patterns. Specifically, self-compassion training or targeted interventions can effectively reduce individuals’ tendencies toward rumination (Neff, 2009). Therefore, individuals with higher levels of self-compassion can reduce their rumination in social situations, reducing their self-attention and reducing the frequency of self-criticism (Neff, 2009; Blackie and Kocovski, 2018). Moreover, social anxiety leads individuals to overestimate the likelihood that others are constantly noticing and negatively evaluating them (Werner et al., 2012), significantly impairing their ability to cope with everyday social situations. However, research has found that individuals with higher levels of self-compassion demonstrate greater insight into negative circumstances, exhibit enhanced self-acceptance, and maintain a kind and understanding attitude toward themselves, thereby mitigating social anxiety (Fink-Lamotte et al., 2023). Therefore, we speculate that in the relationship between rumination and social anxiety, self-compassion, as a positive emotion regulation strategy, can effectively alleviate the negative effects of rumination on social anxiety. Based on this, this study proposed the hypothesis that self-compassion plays a negative moderating role between rumination and social anxiety (H3).

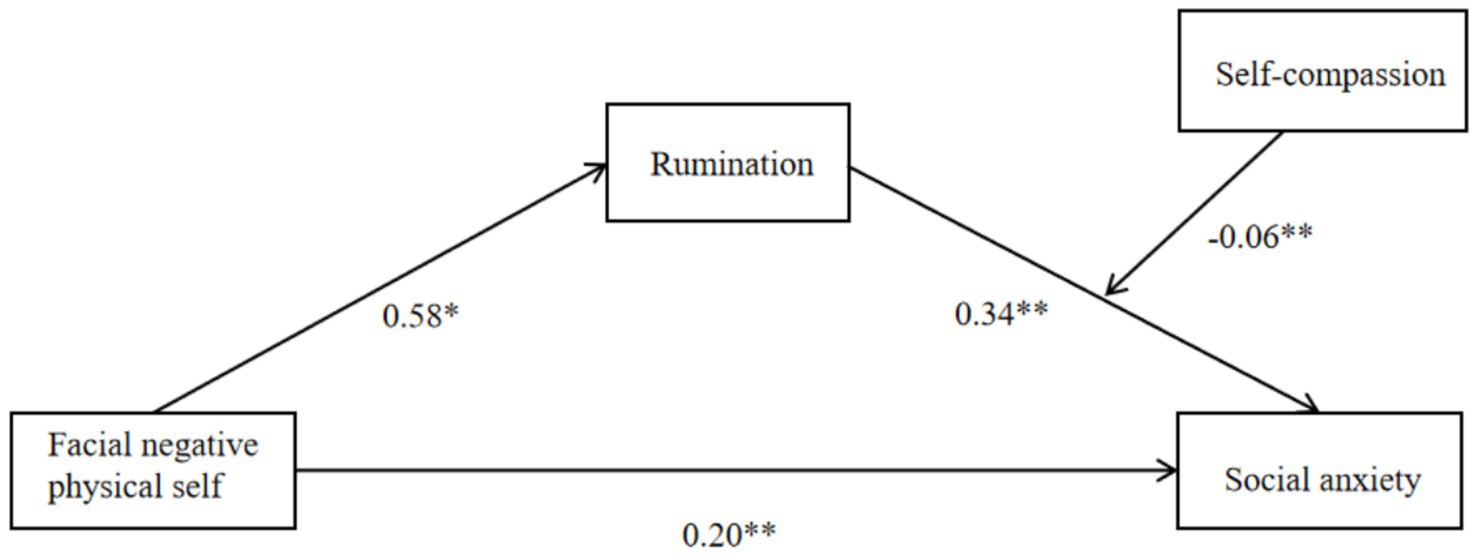

The specific hypothetical model is shown in Figure 1.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants and procedure

This cross-sectional survey was conducted in Southwest China during October 2022. Participants were selected from a multi-disciplinary student population using a convenience sampling approach. The adoption of this non-probability sampling strategy aligns with Etikan et al.'s (2016) methodological framework, whereby convenience sampling is justified when the target population inherently meets predetermined eligibility criteria. All sampled students satisfied the study’s inclusion requirements prior to questionnaire administration. Inclusion criteria: college students at school; signed an informed consent form and voluntarily joined the study. Exclusion criteria: those with severe mental disorders that prevented them from cooperating with the survey; those who did not wish to join the study. The researcher distributed the questionnaire star QR code or link to the subjects through social media platforms, and the participants voluntarily filled in the questionnaire after reading the informed consent form. This study received approval from the North Sichuan Medical College. This study was not preregistered. As such, the confirmatory analyses should be interpreted with caution. A total of 1,350 questionnaires were sent out, the recovery rate was 95.3%, and the completion time was controlled within 15–20 min. After screening (there are 4 lie detector questions, and the wrong answers are regarded as invalid papers), there are 1,178 effective questionnaires, with an effective rate of 91.7%. The subjects were mainly from colleges and universities in Sichuan Province, including 492 male students (41.7%) and 686 female students (58.2%). There are 130 freshmen (11.0%), 347 sophomores (29.4%), 372 juniors (31.6%), 180 seniors (15.3%) and 149 graduate students (12.6%). 508 (43. 1%) of the students came from rural areas and 670 (56.8%) from urban areas.

2.2 Materials

2.2.1 Facial negative physical self

The study utilized the Negative Physical Self Scale-Facial Appearance Subscale (NPSS-A; Chen, 2006). There are 11 questions with 5-point scoring. Higher scores indicate a higher degree of negative appearance. The Cronbach's α coefficient for this subscale in the current study was 0.92.

2.2.2 Social anxiety

The level of social anxiety was assessed using the Interaction Anxiousness Scale (IAS; Leary, 1983) via self-report. The scale was developed by Leary using the clinical empirical method to rate an individual's level of social anxiety and consists of 15 questions on a 5-point scale, including 4 reverse scoring questions (3, 6, 10, and 15). Chunzi Peng revised it in 2004, and the revised scale has good reliability and validity and is a valid tool for measuring social anxiety in college students. The Cronbach's α coefficient for the scale in the current study was 0.85.

2.2.3 Self-compassion

The study used the Adolescent Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) developed by Gong et al. (2014). Using the scale developed by Neff (2003) as a blueprint, Gong revamped the Adolescent Self-Compassion Scale, taking into account the cultural differences between China and the rest of the world. The scale consists of 12 items with the same degree of content encompassment as the scale compiled by Neff, i.e., self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness. 5-point scoring with 5 reverse scoring questions (2, 3, 4, 8, and 11), and the Cronbach's α coefficient for this scale in the current study was 0.66.

2.2.4 Rumination

The Chinese version of the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS) developed by Nolen-Hoeksema (1991) and translated and revised by Han and Yang (2009) was used. There are 22 questions in total, and the scale is divided into four levels of scores from 1 to 4, with 1 representing "never" and 4 representing "always", and the higher the score, the higher the degree of rumination. The Cronbach's α coefficient for this scale in the current study was 0.93.

2.3 Analysis methods

SPSS 26.0 was used for statistical processing of data in this study. Relationships among the four variables and differences in demographic variables were explored. Next, the hypothesized model constructed in this study involves three tests of direct effect, mediating effect, and moderating effect, using the PROCESS plug-in to explore the mediating role of rumination and the moderating role of self-compassion. The PROCESS macro was employed for mediation analysis in preference to structural equation modeling (SEM) based on two methodological rationales. First, this computational tool offers enhanced operational efficiency through its pre-specified mediation models integrated with bootstrapping procedures, which has gained widespread recognition in contemporary mediation research (Preacher and Hayes, 2008). Second, empirical evidence from Hayes et al. (2017) confirms analytical consistency between PROCESS-derived results and SEM outputs in testing mediation pathways.

3 Results

3.1 Common method bias test

Four variables were measured in this study using questionnaires. Harman's one-factor method was used for testing. The results showed that nine factors with eigenroots greater than 1 were extracted from this study without variance rotation of the variables, and the variance explained by the first factor was 27% (< 40%). So there is no serious common method bias.

3.2 Correlation analyses

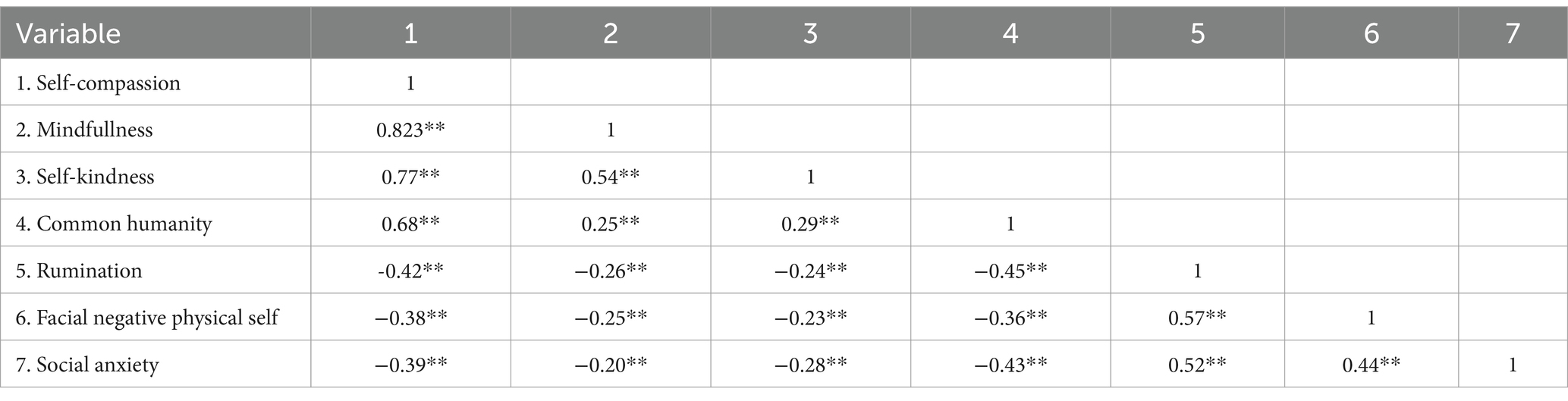

The correlations of the four variables were analyzed using Pearson correlation analysis and the results are shown in Table 1. As can be seen in Table 1, self-compassion and each factor were significantly correlated two-by-two with the other three variables. Specifically, self-compassion was negatively correlated with rumination (p < 0.01), facial negative physical self (p < 0.01), and social anxiety (p < 0.01), with correlation coefficients of –0.42, –0.38, and –0.39, respectively. Facial negative physical self was positively correlated with rumination (p < 0.01), with a coefficient of 0.57. Facial negative physical self and social anxiety were positively correlated (p < 0.01) with a coefficient of 0.44. Rumination thinking was positively correlated (p < 0.01) with social anxiety with a coefficient of 0.52.

3.3 Mediating effects analysis

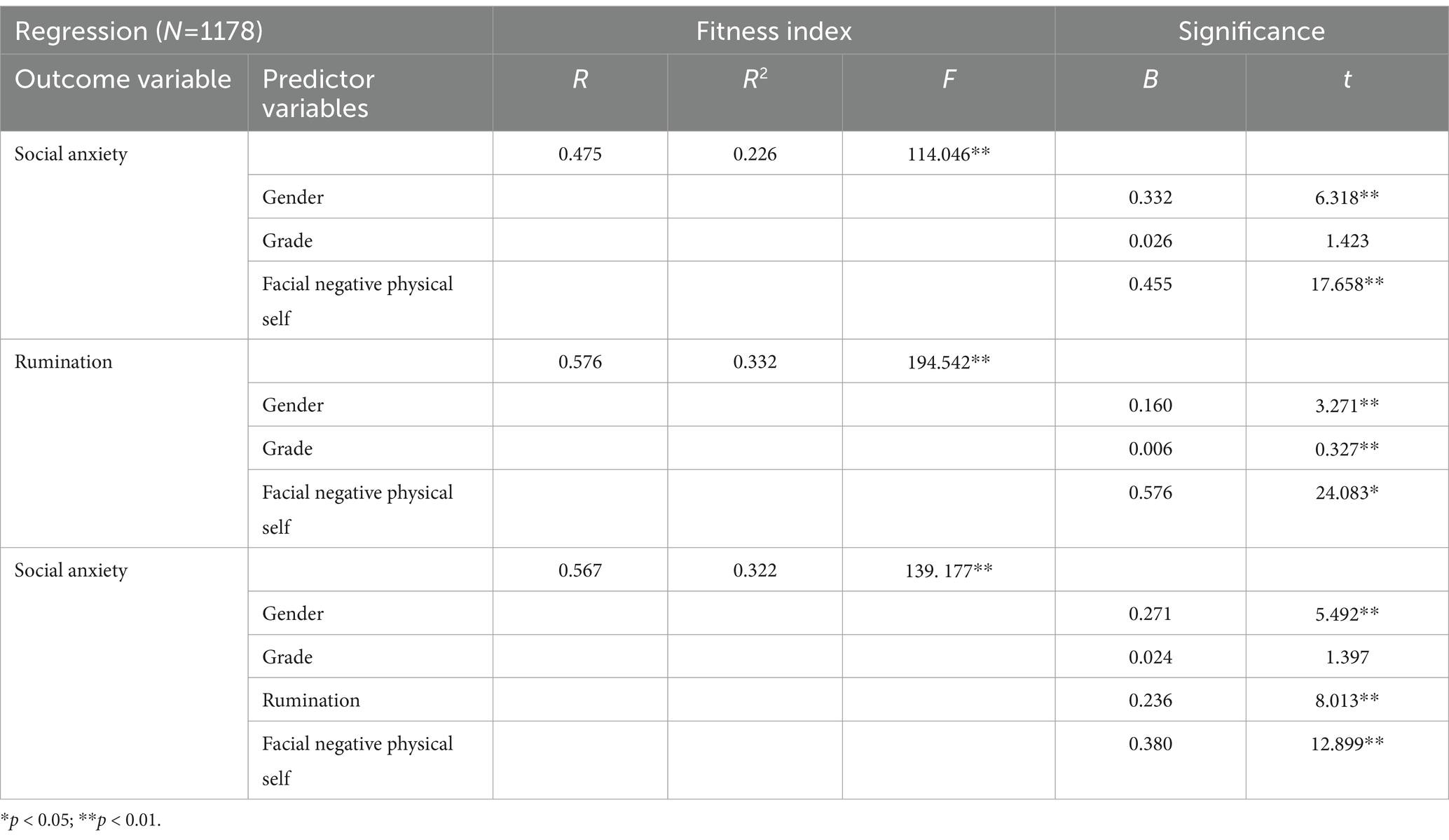

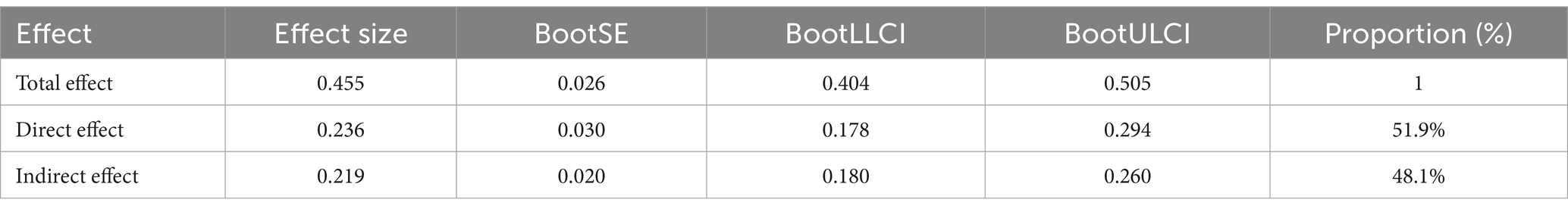

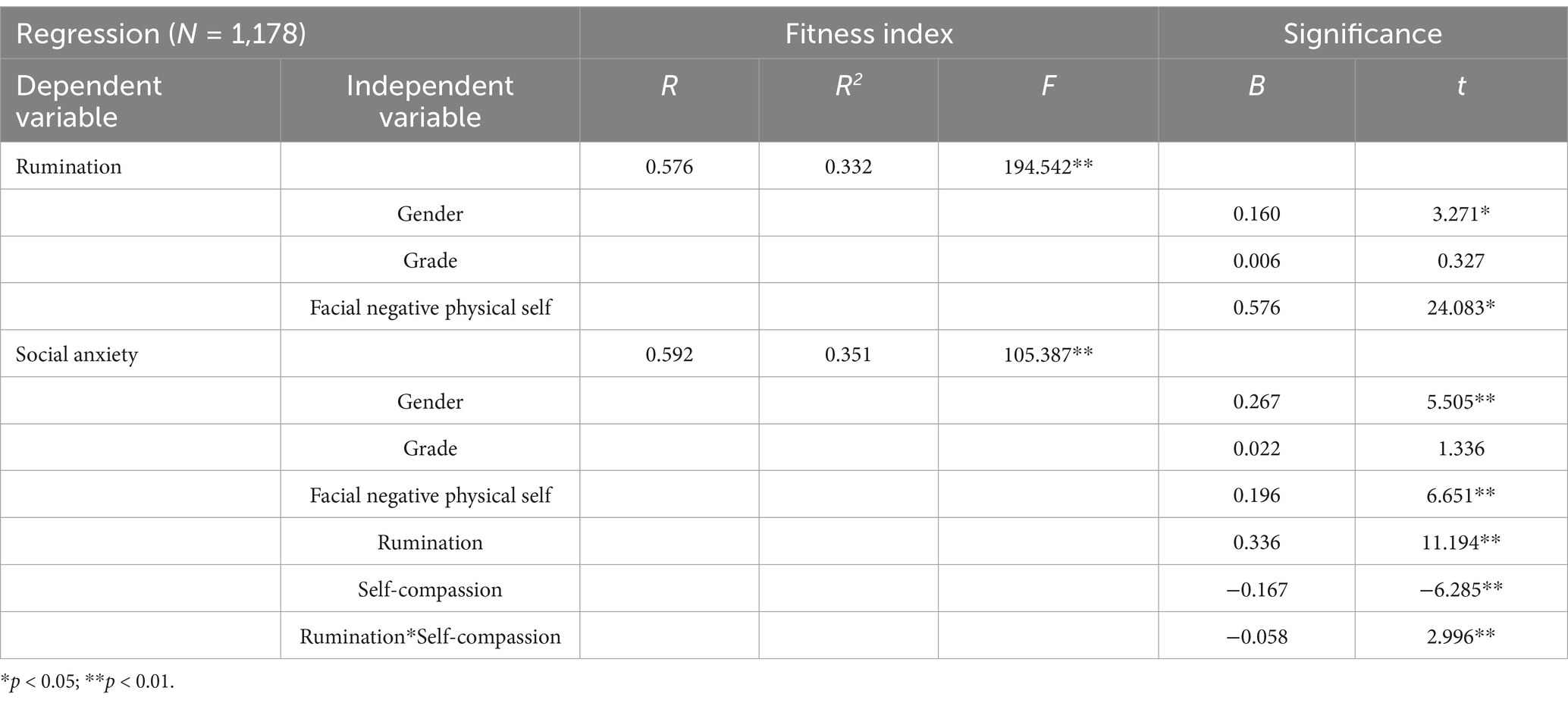

The hypothesized model constructed in this study involves three tests of direct effect, mediating effect, and moderating effect, and SPSS 26.0 was used to analyze the data to verify the previous hypotheses. To test the hypotheses proposed by the study, we proposed to use Process in SPSS for model testing. We controlled for gender and grade as demographic variables, and we verified the significance of the mediating effect of rumination in the facial negative physical self and social anxiety by using facial negative physical self as the independent variable and social anxiety as the dependent variable.The results showed (as shown in Table 2) that when we tested with Model 4 (simple mediator model), there was a significant positive predictive effect of facial negative physical self on social anxiety (B = 0.46, t = 17.66, p < 0.01), and Hypothesis H1 was supported: Facial negative physical self positively predicts social anxiety. We put rumination into the model as a mediating variable and the direct effect of the model remained significant (B = 0.38, t = 12.90, p < 0.01) and there was a significant positive predictive effect of facial negative physical self on rumination (B = 0.58, t = 24.08, p < 0.01), and rumination also positively predicted social anxiety (B = 0.24, t = 8.01, p < 0.01), suggesting that facial negative physical self enhances rumination and rumination enhances social anxiety. In addition, the direct utility of the facial negative physical self on social anxiety and the mediating utility of rumination were not included in the upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence intervals in Bootstrap at zero (see Table 3). The results of this data suggest that the facial negative physical self not only directly predicts social anxiety, but also predicts social anxiety through the mediating effect of rumination, as validated by H2. Finally, the direct (0.236) and mediated (0.219) effects in the mediation model accounted for 51.9% and 48. 1% of the total effect (0.455), respectively. To test our hypotheses, we include moderating variables.

3.4 Moderating effect analysis

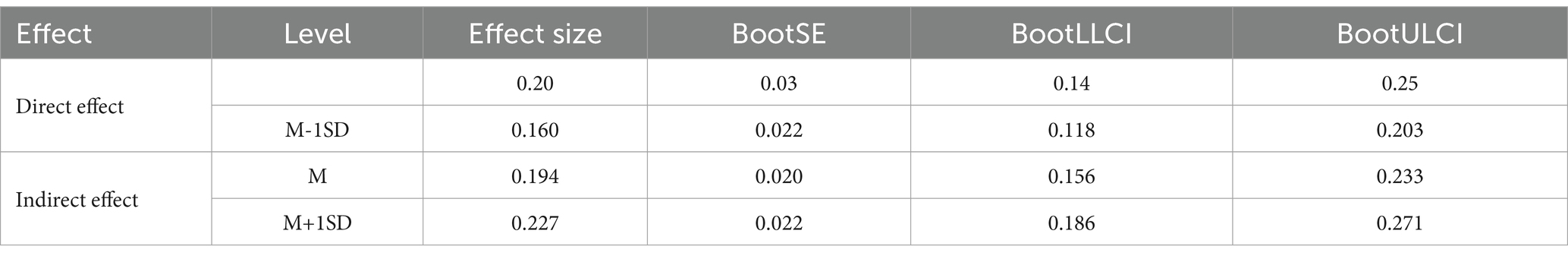

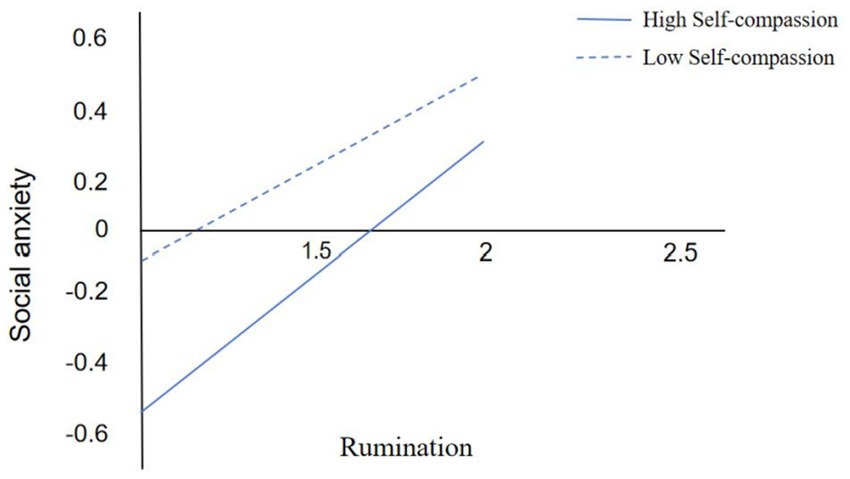

We added self-compassion as a moderating variable to the path of the facial negative physical self effect of looks on social anxiety using Model 14 in the SPSS process (which assumes that the moderating variable moderates the second half of the path in a simple mediation model). After controlling for gender and grade, we tested this moderated mediation model.The results showed (see Table 4) that after placing self-compassion into the model, the interaction term between rumination and self-compassion had a significant negative effect on social anxiety (β = −0.06, t = 3.00, p < 0.01), and since rumination was a significant positive effect on social anxiety (β = 0.34, t = 11.19, p < 0.01), we concluded that self-compassion buffered the effect of rumination on the positive predictive effect of social anxiety. Combined with the simple slope test (see Figure 2), we found that college students with lower levels of self-compassion (one standard deviation below the mean, M-1SD), rumination was a significant positive predictor of social anxiety (simple slope = 0.28, t = 8.18, p < 0.01). In contrast, for individuals with higher levels of self-compassion (M + 1SD), rumination also significantly positively predicted social anxiety (simple slope = 0.39, t = 10.58, p < 0.01), but with a weaker predictive effect. This suggests a gradual weakening of the positive prediction of social anxiety by rumination due to increasing levels of individual self-compassion.

In addition, at all three levels of self-compassion, the mediating effect of rumination in the relationship between the look-negative body self and social anxiety tended to diminish as the level of self-compassion increased (see Table A1). This means that as college students’ level of self-compassion increased, the look-negative body self was less likely to influence social anxiety through rumination. This suggests that self-compassion moderated the second half of the mediating effect: self-compassion moderated the effect of rumination on social anxiety, as validated by H3. The specific moderated mediation model diagram is shown in Figure A1.

4 Discussion

The present study found that facial negative physical self positively predicts social anxiety among college students, with rumination serving as a mediating factor in this relationship. Specifically, the influence of facial negative physical self on social anxiety may be realized through rumination. Self-compassion was found to moderate the latter half of this mediating pathway, that is, self-compassion moderates the effect of rumination on social anxiety. These findings provide empirical evidence for the prevention and intervention of social anxiety in college students.

4.1 The effect of facial negative physical self on social anxiety

The results revealed a positive correlation between the two variables, with facial negative physical self significantly predicting social anxiety. Social anxiety encompasses specific fears arising from social situations, including fear of exposure to unfamiliar individuals, apprehension about being scrutinized by others, and feelings of shame (Swee et al., 2021). Consequently, individuals with negative self-perceptions of their appearance may overestimate the likelihood of receiving negative evaluations from others, thereby developing symptoms of social anxiety. The research results of this paper are consistent with many domestic and foreign research results. Zhang and Hu (2021) demonstrated that self-objectification exerts a significant effect on social anxiety through the mediating role of body dissatisfaction. Findings indicated that, except for the "thinness" dimension, other dimensions of negative physical self (global, weight, facial appearance, and height) were significantly positively correlated with social anxiety (Wang, 2017). International studies have consistently supported these conclusions. For instance, regression analyses revealed that women’s social anxiety is significantly negatively associated with body image (Ratnasari et al., 2021). Additional research has shown that both men and women dissatisfied with their physical appearance often experience negative emotions (e.g., anxiety and depression) and exhibit reluctance to engage in social relationships, thereby contributing to social anxiety (Zhu et al., 2021; Dou et al., 2023).

4.2 Analysis of the mediating role of rumination

The mediation model revealed that rumination plays a partial mediating role between facial negative physical self and social anxiety among college students: Facial negative physical self can directly influence social anxiety and also indirectly affect it through rumination. First, facial negative self reflects dissatisfaction with one’s appearance. When individuals are dissatisfied with their physical appearance, they are more likely to perceive their appearance as being scrutinized or even mocked by others in social situations (Menzel et al., 2010). This perception leads to heightened negative emotions, increasing reluctance to engage in social relationships (Zhu et al., 2021), ultimately fostering anxiety and fear toward social interactions and behaviors. This perspective has been widely supported by researchers (Zhu et al., 2021; Cai et al., 2024). Furthermore, facial negative physical self in college students can also impact social anxiety via rumination. Individuals with stronger negative self-perceptions of their appearance exhibit lower self-acceptance and greater susceptibility to negative emotional states (Zhu et al., 2021), as well as a tendency to ruminate excessively about their appearance during interpersonal interactions (Neff, 2009). Rumination is a common and critical issue faced by college students in social contexts. If individuals excessively focus on their negative emotions, thoughts, or behaviors during social interactions, repetitively and passively dwell on details and antecedents of social events, fixate on the causes and consequences of distressing social experiences, and struggle to disengage from these thoughts, they are more likely to experience anxiety in social situations (Modini and Abbott, 2017). Therefore, facial negative physical self among college students can also influence social anxiety through the mediating role of rumination.

4.3 Analysis of the moderating role of self-compassion

The moderated mediation model revealed that self-compassion significantly moderates the mediating role of rumination between facial negative physical self and social anxiety. Specifically, across three levels of self-compassion, the mediating effect of rumination in the relationship between facial negative physical self and social anxiety gradually diminished as self-compassion levels increased. In other words, college students with higher self-compassion are less likely to experience social anxiety through the pathway of facial negative physical self influencing rumination. On one hand, research indicates that self-compassion, as an adaptive emotion regulation strategy, can effectively alleviate ruminative thinking in individuals prone to ruminative cognitive patterns (Neff, 2009). On the other hand, from the perspective of the three dimensions of self-compassion (self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness), enhancing self-compassion enables individuals to approach both past and potential future events with self-kindness, recognition of shared human experiences, and mindful acceptance. To elaborate: Self-kindness refers to treating one’s shortcomings with benevolence rather than self-judgment. Common humanity involves acknowledging that imperfection, suffering, and failure are universal human experiences. Mindfulness entails observing problems objectively without avoidance or over-identification, maintaining a non-emotional and accepting stance. If individuals cultivate self-compassion, they are better able to observe their emotional states and personal flaws with objectivity and openness, thereby reducing rumination (Allen and Leary, 2010). These findings are corroborated by extensive empirical studies (Butz and Stahlberg, 2018; Neff, 2009; Allen and Knight, 2005). Consequently, higher levels of self-compassion lead to reduced rumination, and the subsequent decline in rumination alleviates fear of social interactions (Modini and Abbott, 2017). Thus, self-compassion moderates the role of rumination in the association between facial negative physical self and social anxiety among college students.

5 Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations. First, during data collection, the majority of participants were first- and second-year undergraduates, resulting in an uneven distribution across academic years. Second, as a cross-sectional study, it cannot establish causal relationships or fully demonstrate the predictive effect of negative facial appearance self-perception on college students' social anxiety. Third, regarding the study sample: (1) focusing solely on enrolled college students limits the sample representativeness, and the findings may not be generalizable to other populations; (2) participants were recruited exclusively from universities in Sichuan, China, which may introduce demographic limitations due to the single data source. Lastly, the lack of preregistration raises the possibility of file-drawer effects, limiting the robustness and replicability of our conclusions.

The limitations of this study provide concrete directions for future research. First, subsequent studies should strictly control the number of participants from each academic year to achieve balanced distribution across grade levels, thereby enhancing sample representativeness and result reliability. Second, building on our findings, future research could employ longitudinal intervention designs to examine how state self-compassion levels moderate the relationship between facial negative physical self and social anxiety. Third, expanding both the participant pool and geographical coverage would improve the generalizability of findings. Fourth, as negative physical self encompasses five dimensions (facial appearance, height, weight, thinness, and general negative physical self), future studies could focus on dimensions beyond facial appearance to investigate their differential impacts on social anxiety. Lastly, it is essential to preregister all procedures and hypotheses. This will be crucial in examining whether the results obtained in this study are robust and can be replicated.

6 Conclusion

This study revealed that: the facial negative physical self positively predicts social anxiety among college students; the facial negative physical self indirectly influences social anxiety through the mediating role of rumination; Self-compassion moderates the impact of rumination on social anxiety. These findings suggest that universities should pay attention to the phenomenon of appearance anxiety among college students, guiding them to establish appropriate self-evaluation standards. Rather than judging self-worth solely by physical appearance, students should be encouraged to conduct comprehensive assessments of their abilities and intrinsic values to cultivate inner self-confidence. Simultaneously, social media and popular culture should take responsibility for actively promoting healthy and diverse aesthetic standards to alleviate adolescents' appearance anxiety. Furthermore, this study provides intervention strategies for reducing college students' social anxiety, specifically through the enhancement of self-compassion competencies to optimize psychological well-being in social interactions.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by North Sichuan Medical College. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

YY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. XinyZ: Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. JZ: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. YC: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. XinZ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was financially supported by the Funding Project of North Sichuan Medical College (No. CBY22-QNB06) and Nanchong Social Science Research “14th Five-Year Plan” 2024 Annual Project (No. NC24C170).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdollahi, A. (2019). The association of rumination and perfectionism to social anxiety. Psychiatry, 82, 345–353.

Allen, N. B., and Knight, W. E. J. (2005). “Mindfulness, compassion for self, and compassion for others: implications for understanding the psychopathology and treatment of depression” in Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy. ed. P. Gilbert (Hove: Routledge), 239–262.

Allen, A. B., and Leary, M. R. (2010). Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 4, 107–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00246.x

Blackie, R. A., and Kocovski, N. L. (2018). Examining the relationships among self-compassion, social anxiety, and post-event processing. Psychol. Rep. 121, 669–689. doi: 10.1177/0033294117740138

Bornioli, A., Lewis-Smith, H., Slater, A., and Bray, I. (2021). Body dissatisfaction predicts the onset of depression among adolescent females and males: a prospective study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 75, 343–348. doi: 10.1136/jech-2019-213033

Brozovich, F. A., Goldin, P., Lee, I., Jazaieri, H., Heimberg, R. G., and Gross, J. J. (2015). The effect of rumination and reappraisal on social anxiety symptoms during cognitive‐behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. J. Clin. Psychol, 71, 208–218.

Bugay-Sökmez, A., Manuoğlu, E., Coşkun, M., and Sümer, N. (2023). Predictors of rumination and co-rumination: the role of attachment dimensions, self-compassion and self-esteem. Curr. Psychol. 42, 4400–4411. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01799-0

Butz, S., and Stahlberg, D. (2018). Can self-compassion improve sleep quality via reduced rumination? Self Identity 17, 666–686. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2018.1456482

Cai, J., Du, L., Yu, J., Yang, X., Chen, X., Xu, X., et al. (2024). Body image and social anxiety in hemifacial spasm: examining self-esteem and fear of negative evaluation as mediators. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 245:108516. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2024.108516

Chen, H. (2003). A theoretical and empirical study of adolescents' physical self. (Doctoral dissertation). Chongqing: Southwest University, Southwest Normal University.

Chen, H. (2006). Adolescent physical self: Theory and empirical evidence. Beijing: Xinhua Publishing House, 125.

Davison, T. E., and McCabe, M. P. (2005). Relationships between men’s and women’s body image and their psychological, social, and sexual functioning. Sex roles, 52, 463–475.

Dong, W., Tang, H., Wu, S., Lu, G., Shang, Y., and Chen, C. (2024). The effect of social anxiety on teenagers’ internet addiction: the mediating role of loneliness and coping styles. BMC Psychiatry 24:395. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-05854-5

Dou, Q., Chang, R., and Xu, H. (2023). Body dissatisfaction and social anxiety among adolescents: a moderated mediation model of feeling of inferiority, family cohesion and friendship quality. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 18, 1469–1489. doi: 10.1007/s11482-023-10148-1

Edgar, E. V., Richards, A., Castagna, P. J., Bloch, M. H., and Crowley, M. J. (2024). Post-event rumination and social anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 173, 87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.03.013

Elhai, J. D., Tiamiyu, M., and Weeks, J. (2018). Depression and social anxiety in relation to problematic smartphone use: The prominent role of rumination. Internet Res, 28, 315–332.

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., and Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 5, 1–4. doi: 10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Etu, S. F., and Gray, J. J. (2010). A preliminary investigation of the relationship between induced rumination and state body image dissatisfaction and anxiety. Body Image 7, 82–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.09.004

Feinstein, B. A., Hershenberg, R., Bhatia, V., Latack, J. A., Meuwly, N., and Davila, J. (2013). Negative social comparison on Facebook and depressive symptoms: Rumination as a mechanism. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult, 2, 161.

Fink-Lamotte, J., Hoyer, J., Platter, P., Stierle, C., and Exner, C. (2023). Shame on me? Love me tender! Inducing and reducing shame and fear in social anxiety in an analogous sample. Clin. Psychol. Eur. 5:e7895. doi: 10.32872/cpe.7895

Gong, H. L., Jia, H. L., Guo, T. M., and Zou, L. L. (2014). Revision of the Adolescent Self-Compassion Scale and tests of its reliability and validity. Psychol. Res. 7:6.

Han, X., and Yang, H. F. (2009). Application of the Nolen-Hoeksema ruminative response scale in China. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 17, 550–551. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611

Hayes, A. F., Montoya, A. K., and Rockwood, N. J. (2017). The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equation modeling. Australas. Mark. J. 25, 76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ausmj.2017.02.001

Huang, F., Guo, F., Ding, Q., and Hong, J. Z. (2021). Social anxiety and mobile phone addition in college students: the influence of cognitive failure and regulatory emotional self-efficacy. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 29, 56–59. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.01.011

IzgiçF, A. G., Doğan, O., and Kuğu, N. (2004). Social phobia among university students and its relation to self-esteem and body image. Can. J. Psychiatry 49, 630–634. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900910

Lacombe, C., Elalouf, K., and Collin, C. (2024). Impact of social anxiety on communication skills in face-to-face vs. online contexts. Comp. Human Behavior Reports 15:100458. doi: 10.1016/j.chbr.2024.100458

Leary, M. R. (1983). Social anxiousness: the construct and its measurement. J Personal. Assess. 47, 66–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4701_8

Li, C., Xu, K., Huang, X., Chen, N., Li, J., Wang, J., et al. (2019). Mediating role of negative physical self in emotional regulation strategies and social anxiety. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 27, 1564–1567.

Menzel, J. E., Schaefer, L. M., Burke, N. L., Mayhew, L. L., Brannick, M. T., and Thompson, J. K. (2010). Appearance-related teasing, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating: a meta-analysis. Body Image 7, 261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.05.004

Modini, M., and Abbott, M. J. (2017). Negative rumination in social anxiety: a randomised trial investigating the effects of a brief intervention on cognitive processes before, during and after a social situation. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 55, 73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2016.12.002

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity 2, 223–250. doi: 10.1080/15298860309027

Neff, K. D. (2009). “Self-compassion” in Handbook of individual differences in social behavior. eds. M. R. Leary and R. H. Hoyle (New York: Guilford Press), 561–573.

Neff, K. D. (2023). Self-compassion: theory, method, research, and intervention. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 74, 193–218. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-032420-031047

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 100, 569–582. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569

Öztekin, G. G. (2024). The effects of social anxiety on subjective well-being among adolescents: the mediating roles of mindfulness and loneliness. Iğdır Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 36, 220–236. doi: 10.54600/igdirsosbilder.1433959

Pawijit, Y., Likhitsuwan, W., Ludington, J., and Pisitsungkagarn, K. (2019). Looks can be deceiving: body image dissatisfaction relates to social anxiety through fear of negative evaluation. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 31, 1–7. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2017-0031

Peng, C. (2004). The adaptation of interaction anxiousness scale in Chinese undergraduate students. Chin. Ment. Health J. 18, 39–41. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1000-6729.2004.01.014

Póka, T., Fodor, L. A., Barta, A., and Mérő, L. (2024). A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effectiveness of self-compassion interventions for changing university students’ positive and negative affect. Curr. Psychol. 43, 6475–6493. doi: 10.1007/s12144-023-04834-4

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Ratnasari, S. E., Pratiwi, I., and Wildannisa, H. (2021). Relationship between body image and social anxiety in adolescent women. Eur. J. Psychol. Res. 8, 65–72. Available at: https://www.idpublications.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Full-Paper-RELATIONSHIP-BETWEEN-BODY-IMAGE-ANDSOCIAL-ANXIETY-IN-ADOLESCENT-WOMEN.pdf.

Rivière, J., Rousseau, A., and Douilliez, C. (2018). Effects of induced rumination on body dissatisfaction: is there any difference between men and women? J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 61, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2018.05.005

Salari, N., Heidarian, P., Hassanabadi, M., Babajani, F., Abdoli, N., Aminian, M., et al. (2024). Global prevalence of social anxiety disorder in children, adolescents and youth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Prevent. 45, 795–813. doi: 10.1007/s10935-024-00789-9

Sun, M., and Liu, K. (2018). Analysis of the mediating role of loneliness between social anxiety and depressive symptoms in middle school students. China Health Statistics 35, 926–928.

Swee, M. B., Hudson, C. C., and Heimberg, R. G. (2021). Examining the relationship between shame and social anxiety disorder: a systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 90:102088. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102088

Valena, S. P., and Szentagotai-Tatar, A. (2015). The relationships between stress, negative affect, rumination and social anxiety. J EVID-BASED PSYCHOT, 15:179.

Wan, Z., Li, S., and Fang, S. (2024). The effect of negative physical self on social anxiety in college students: the bidirectional chain mediation roles of fear of negative evaluation and regulatory emotional self-efficacy. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 17, 2055–2066. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S457405

Wang, T. (2017). The relationship between social comparison orientation and social anxiety among female college students: The mediating role of negative physical self. (Master's thesis). Nanjing: Nanjing Normal University.

Wasylkiw, L., MacKinnon, A. L., and MacLellan, A. M. (2012). Exploring the link between self-compassion and body image in university women. Body Image, 9, 236–245.

Watkins, E. R., and Roberts, H. (2020). Reflecting on rumination: consequences, causes, mechanisms and treatment of rumination. Behav. Res. Ther. 127:103573. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2020.103573

Werner, K. H., Jazaieri, H., Goldin, P. R., Ziv, M., Heimberg, R. G., and Gross, J. J. (2012). Self-compassion and social anxiety disorder. Anxiety, Stress \u0026amp; Coping, 25, 543–558.

Willemse, H., Geenen, R., Egberts, M. R., Engelhard, I. M., and Van Loey, N. E. (2023). Perceived stigmatization and fear of negative evaluation: two distinct pathways to body image dissatisfaction and self-esteem in burn survivors. Psychol. Health 38, 445–458. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2021.1970160

Zhang, X. Y., and Hu, J. S. (2021). The effects of self-objectification on social anxiety in college students: the mediating role of body dissatisfaction. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 3, 428–431. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2021.03.022

Zhang, C. L., and Zhou, Z. K. (2018). Passive social network site use, social anxiety, rumination and depression in adolescents. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 26, 490–497. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2018.03.016

Zhao, D., and Zhang, J. (2024). The effects of working memory training on attention deficit, adaptive and non-adaptive cognitive emotion regulation of Chinese children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). BMC Psychol. 12:59. doi: 10.1186/s40359-024-01539-6

Zhu, Y., Huang, P., Cai, C., Wang, X., Zhang, M., and Li, B. (2021). The study on the relationship among negative physical self, fear of negative evaluation, physical appearance perfectionism and social appearance anxiety in female patients with psoriasis. Chin. J. Practical Nur. 36, 2577–2583. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn211501-20201022-04244

Appendix

Keywords: rumination, self-compassion, social anxiety, moderated mediation model, facial negative physical self

Citation: Yan Y, Zhou X, Zhou J, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Zhou X and Luo J (2025) The relationship between facial negative physical self and social anxiety in college students: the role of rumination and self-compassion. Front. Psychol. 16:1450174. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1450174

Edited by:

Konrad Reschke, Leipzig University, GermanyReviewed by:

Jakob Fink-Lamotte, University of Potsdam, GermanyKemal Oztemel, Gazi University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Yan, Zhou, Zhou, Chen, Zhang, Zhou and Luo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuxian Yan, MTIyOTAzNDkzMUBxcS5jb20=; Jiaming Luo, amlhbWluZ2x1b0Buc21jLmVkdS5jbg==

Yuxian Yan

Yuxian Yan Xinyu Zhou

Xinyu Zhou Jinhui Zhou

Jinhui Zhou Jiaming Luo

Jiaming Luo