Abstract

Objective:

The aim of the current study was to adapt the Adult Disorganized Attachment Scale (ADA) to Persian and to examine its psychometric properties.

Method:

The study was conducted with 202 participants, including 124 female (61.4%), who were students at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, aged 17–36 years. The Experience in Close Relationships measure was used to assess convergent validity, while the Sadism Scale and Shutdown Dissociation Scale were used to evaluate criterion validity. The reliability using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, convergent validity, and construct validity using confirmatory factor analysis were examined. The collected data were analyzed in SPSS v.25 and LISREL 8.8 applications.

Results:

The scale demonstrated strong reliability (α = 0.82) and good convergent validity, with positive correlations to Shutdown Dissociation, Anxious and Avoidant Attachment, and Sadism (p < 0.05). Confirmatory Factor Analysis supported its structural validity with excellent fit indexes (χ2/df = 1.44, RMSEA = 0.047, CFI = 0.98, GFI = 0.96).

Conclusion:

This Persian version of the ADA can be considered a valid and reliable scale, which is a short and practical tool that can be used in clinical and research settings in Iran.

Introduction

Attachment theory, originally formulated by Bowlby (1969, 1973, 1980), primarily focuses on the relationship between an infant and their caregiver (Belsky, 2002).

Through early interactions, the child forms expectations about the world and themselves. These expectations develop into cognitive models of self and others. Bowlby (1988) referred to these cognitive models as internal working models (IWMs), which serve as the foundation for future relationships (Hoffman, 2006; Zhang et al., 2025; Thompson et al., 2021).

Although these models can adapt and change over time, they generally become more fixed as individuals develop (Belsky, 2002). Therefore, the theory offers a comprehensive framework for understanding the development of personality and the capacity for close relationships in adulthood.

Ainsworth (1982) identified three attachment styles in infants: secure, avoidant, and resistant-ambivalent. Main and Solomon (1990) later recognized a fourth group, disorganized, for children displaying inconsistent, bizarre behaviors, such as freezing or acting out, without a clear behavioral pattern (Hoffman, 2006; Main and Solomon, 1986). They also demonstrated that these infants develop multiple, fragmented internal working models (IWMs) of themselves and their primary caregivers (Main and Solomon, 1986; Liotti, 2006). Bowlby (1973) was one of the first to suggest a link between attachment and dissociative psychopathology and noted that emotionally neglected children develop withdrawal as a defense. When exposed to maltreatment, they often rely on dissociation to cope with trauma (Bowlby, 1980; Blizard, 2001). Even when a caregiver is abusive, the child must stay attached (Bowlby, 1969/1982), leading to complete dependence on the same person who causes harm (Fairbairn, 1952; Main, 1981). This conflict can result in a disorganized attachment style (Main, 1981; Main and Solomon, 1986; Main and Solomon, 1990) and the formation of conflicting views of both the self and the caregiver (Liotti, 1992; Liotti, 1999a; Main, 1991). Dissociation acts as a defense, allowing the child to separate nurturing experiences from abuse. This helps preserve a positive view of the caretaker while developing a separate, powerful, but detached sense of self (Blizard, 1997; Blizard, 2001). Ferenczi suggested that any shock or fear involves some level of personality splitting. He observed that when faced with sudden distress, a weak or undeveloped personality does not defend itself but instead identifies with and internalizes the aggressor (Ferenczi, 1988). This process explains how complex trauma and dissociation can fragment the self, leading to the development of sadistic and masochistic self-states.

attachment strategies influence emotion regulation and relational dynamics. Shaver and Mikulincer (2002) suggest that social psychological methods, such as surveys about romantic relationships, can effectively measure attachment in adults, tapping into emotion-regulation strategies like deactivating, activating, and hyperactivating. Secure individuals handle stress well, express emotions openly, and resolve conflicts constructively. Anxious individuals tend to focus on their distress and use coping strategies that worsen their emotions. Avoidant individuals distance themselves from distressing feelings and avoid confronting painful memories. These behaviors reflect the attachment strategies of hyperactivation and deactivation (Belsky, 2002). Individuals with disorganized attachment often employ a combination of these strategies, alternating between hyperactivation and deactivation. For instance, those who use hyperactivation may experience intense, short-lived relationships followed by sudden breakdowns, often blaming external factors for these failures. Meanwhile, individuals who use deactivation strategies may lead more isolated lives, avoiding close connections. This mix of strategies leads to unstable and conflicting emotional regulation (Bateman, 2022; Bateman and Fonagy, 2019).

Given the critical role of attachment in psychological well-being, researchers have developed various instruments to assess adult attachment styles.

The Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) is the gold standard for assessing adult attachment, offering a detailed evaluation of past and present experiences. However, its administration requires extensive training, certification, and significant time, making self-report measures a more practical alternative (Pollak et al., 2008; Meyer and Pilkonis, 2001; Meier and Bureau, 2018).

To address this limitation, researchers have developed self-report measures specifically designed to assess disorganized attachment.

Psychologists frequently use continuous and dimensional self-report tools such as the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) questionnaire (Brennan et al., 1998) and its revised version (Fraley et al., 2000).

These instruments commonly assess attachment in adult romantic relationships using two primary dimensions: anxiety and avoidance. Clinical studies occasionally investigate attachment across three dimensions: secure, anxious, and avoidant.

Specific scales developed to measure disorganized attachment include the Adult Disorganized Attachment (ADA) scale (Paetzold et al., 2015), the Disorganized Response Scale (DRS) (Briere et al., 2018), and the Childhood Disorganization and Role Reversal Scale (CDRR) (Meier and Bureau, 2018; Pollard et al., 2023).

The ADA scale assesses attitudes and responses to current close relationships, specifically addressing the construct of disorganized attachment in adults by focusing on fear, confusion about relationships, and distrust of close others. Meanwhile, the DRS aims to measure self-reported disorganized verbalizations, thoughts, and behaviors specifically related to discussing childhood experiences (Briere et al., 2018).

CDRR is developed to assess disorganized attachment in young adults by measuring their current perceptions of childhood disorganized and controlling attachment (Meier and Bureau, 2018; Pollard et al., 2023; Molisa, 2015).

Some researchers (Mikulincer and Shaver, 2007; Simpson and Rholes, 2002) have argued that disorganization may be a form of fearful avoidance, based on the Relationship Questionnaire (RQ). Fearful avoidants are seen as high in both anxiety and avoidance, leading to conflicting behaviors. However, disorganization is not simply a combination of organized strategies but coexists with them. Most social psychologists use dimensional measures like the ECR and do not examine how high levels of both anxiety and avoidance might interact. Based on the developmental literature, disorganization should be considered as a distinct construct that requires further investigation. The Adult Disorganized Attachment (ADA) scale, developed by Paetzold et al. (2015), was created to specifically assess this distinct attachment pattern, distinguishing it from other forms of attachment insecurity (Paetzold et al., 2015).

In this study we explore the construct of adult disorganized attachment, how it can be evaluated, and whether the related variables are similar to those seen in childhood and adolescence, which have not yet been explored in Iran due to the lack of an appropriate measurement tool. Therefore, there is a need for a suitable instrument to assess adult disorganized attachment in our country. This study aims to develop a Persian adaptation of the ADA (Adult Disorganized Attachment) scale and conduct a validity and reliability study.

Method

Sample

This study employed a convenience sampling method, selecting participants from Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences during the 2023–2024 academic year. The sample consisted of 124 females (61.4%) and 202 participants in total. Tinsley and Tinsley (1987) suggest having 5 to 10 participants per item for psychometric studies (Kyriazos, 2018), meaning 45–90 participants are needed for a 9-item measure. With 202 participants, the study meets this requirement. Additionally, Kline (2016) states that a minimum of N = 100 participants is necessary for Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) (Kyriazos, 2018), confirming that the sample size of 202 is adequate.

Participants were eligible for inclusion if they were enrolled students at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences during the study period and had experienced at least one close romantic relationship, and no exclusion criteria were applied.

Procedure

The Ethics Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences approved this study on December 13, 2023 (IR.KUMS.MED.REC.1402.246). All participants provided written informed consent after being informed about the study’s objectives and assured of data confidentiality.

The original ADA scale was translated into Persian by three clinical psychologists fluent in both English and Persian. Their recommendations were incorporated to finalize the Persian version. A clinical psychologist with advanced English proficiency then back-translated the scale into English. A pilot test with 14 individuals confirmed the clarity and comprehensibility of the Persian version.

Participants were recruited through direct in-person invitations on campus. Those who agreed completed questionnaires and an interview at the university. No incentives were provided for participation.

Statistic analysis

Descriptive statistics, including mean and standard deviation (for quantitative variables) and frequency and its percentage (for qualitative variables), were used. Internal consistency reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. Confirmatory factor analysis was applied to examine validity.

Measures

Adult Disorganized Attachment scale (ADA)

The Adult Disorganized Attachment Scale (ADA), was originally developed by Paetzold et al. (2015) assesses disorganized attachment in adults. This self-report measure includes 9 items, each rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), with total scores ranging from 9 to 63. A single-factor structure accounted for 58.76% of the total variance. The scale demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.91) (Paetzold et al., 2015).

The Shutdown Dissociation Scale (Shut-D)

The Shut-D is a brief structured interview designed to assess vulnerability to dissociation as a consequence of exposure to traumatic stressors, based on the defensive cascade model. This scale includes 13 questions on a 4-point Likert scale (Never = 0, Rarely = 1, Sometimes = 2, Often = 3). Factor analysis provided evidence for unidimensionality; the first factor accounted for 43.4% of the variance (eigenvalue 5.65) and the second factor for 8.2% of the variance (eigenvalue 1.07). The questionnaire demonstrated excellent internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89) and high test–retest reliability (r = 0.93). Convergent validity with the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES) was significant (r = 0.86). The Shut-D score reliably distinguished patients exposed to trauma from healthy control groups and differentiated between diagnostic groups associated with varying levels of trauma exposure. Exposure to traumatic events increases the diversity and frequency of dissociation and is associated with higher severity of PTSD symptoms and depression levels (Schalinski et al., 2015).

Experiences in Close Relationships scale (ECR_R)

The Revised Experiences in Close Relationships was developed by Fraley et al. (2000) includes 18 items related to attachment anxiety and 18 items related to attachment avoidance. Participants rated each statement on a 7-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) based on how much they agreed. The ECR-R demonstrates high reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the Anxiety and Avoidance scales typically above 0.85 (Fraley et al., 2000).

Sadism

The Sadism scale, originally developed by Morten Moshagen, Benjamin E. Hilbig, and Ingo Zettler as part of the Dark Core of Personality framework, was validated in its Persian version with a sample of 541 adults from Tehran. It demonstrated excellent reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91) and strong construct validity through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. The sadism subscale uniquely contributes to the overall dark core beyond general dark traits, highlighting its distinctiveness and relevance. This makes the scale a reliable and valid measure for assessing sadism within the context of dark personality traits (Moshagen et al., 2018; Ebrahimi Ghavam, 2020).

Result

Data from 202 subjects (61.4% female, 38.6% male; mean age = 22.91 years, SD = 3.77, range 17–36) were used for the analysis. All participants were students of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, An independent t-test showed no significant difference in disorganized attachment between women (M = 27.24, SD = 10.26) and men (M = 27.23, SD = 11.05), p > 0.05. Levene’s test confirmed homogeneity of variances (p = 0.05).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

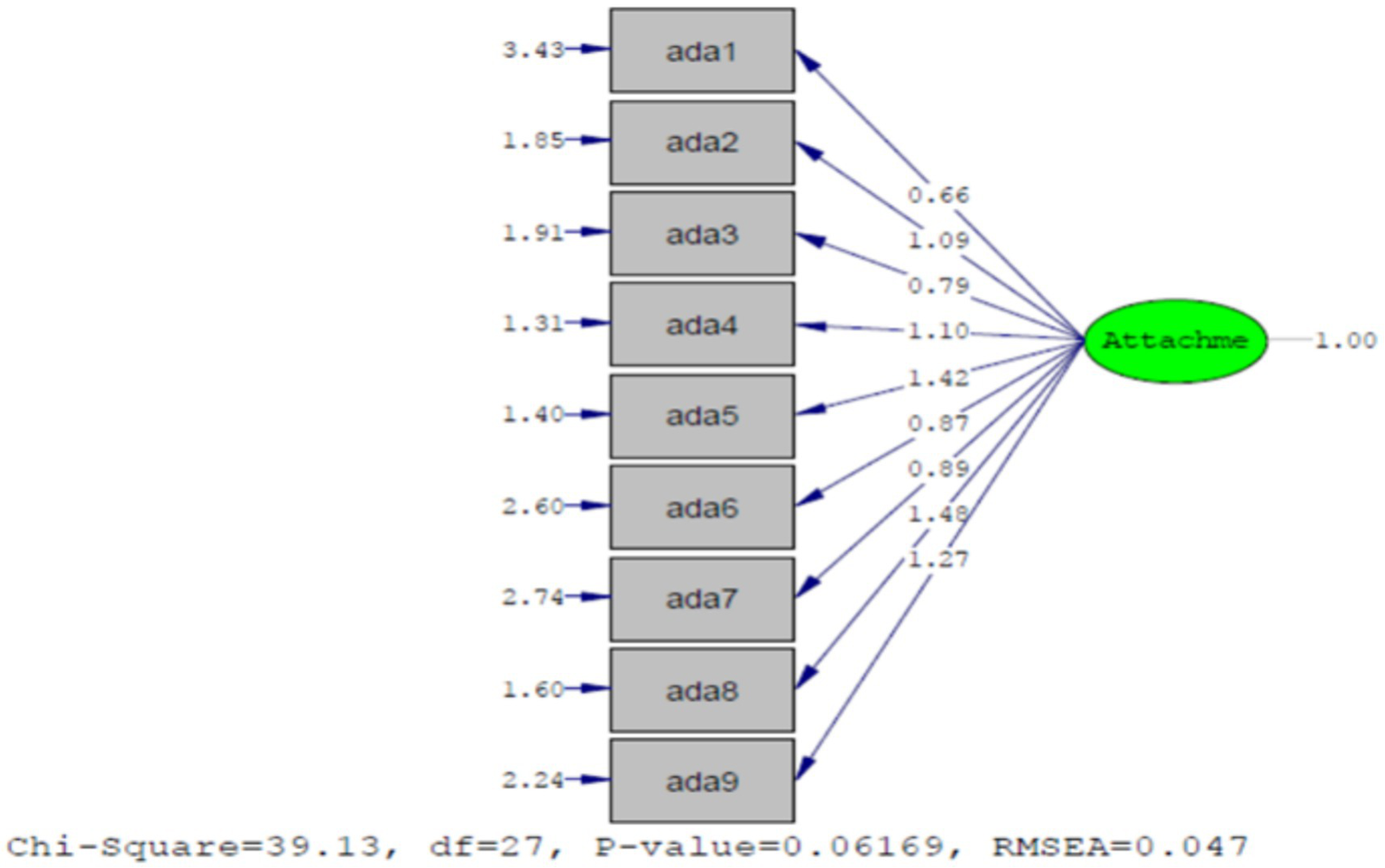

Confirmatory Factor Analysis: The fit of the single-factor structure of the Disorganized Attachment Scale was evaluated using the fit indexes: CFI, NFI, NNFI, GFI, AGFI, IFI, RMSEA, and SRMR. Typically, a Chi-square/df ratio less than 3 indicates a good model fit. However, this index is highly influenced by sample size, and values higher than 3 can also indicate a good fit depending on the sample size.

Generally, an RMSEA less than 0.10, an SRMR less than 0.08, and fit indices CFI, GFI, AGFI, IFI, RFI, NFI, and NNFI above 0.90 (values between 0.80 and 0.90 indicate acceptable and marginal fit) and an AGFI above 0.85 indicate acceptable fit for the structural equation model. The fit results of the single-factor model are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Fit indexes | X2 | df | X2/df | SRMR | GFI | RFI | IFI | CFI | AGFI | NNFI | NFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-factor | 39/13 | 27 | 1.44 | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0/98 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.047 |

Fit indexes for the single-factor structure of the disorganized attachment scale.

RMSEA = Root mean square error of approximation, CFI = Comparative fit index, NFI = Normed fit index, NNFI = Non-normed fit index, AGFI = Adjusted goodness of fit index, RFI = Relative fit index, GFI = Goodness of fit index, SRMR = Standardized root mean square residual, IFI = Incremental fit index.

As shown in the in Figure 1 and Table 2, the single-factor structure of the Disorganized Attachment Scale demonstrates excellent fit.

Figure 1

Single-factor model of the disorganized attachment scale. Numbers next to arrows represent factor loadings. Values on the left side of each item indicate error variances.

Table 2

| Scale items | Mean | SD | Factor loadings | Corrected item-total correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fear is a common feeling in close relationships. | 4.20 | 1.96 | 0.66 | 0.48** |

| 2. I believe that romantic partners often try to take advantage of each other. | 2.89 | 1.74 | 1.09 | 0.66** |

| 3. I never know who I am with romantic partners. | 2.25 | 1.58 | 0.79 | 0.58** |

| 4. I find romantic partners to be rather scary. | 2.35 | 1.58 | 1.10 | 0.71** |

| 5. It is dangerous to trust romantic partners. | 2.76 | 1.84 | 1.42 | 0.74** |

| 6. It is normal to have traumatic experiences with the people you feel close to. | 3.58 | 1.83 | 0.87 | 0.57** |

| 7. Strangers are not as scary as romantic partners. | 2.99 | 1.87 | 0.89 | 0.57** |

| 8. I could never view romantic partners as totally trustworthy. | 3.02 | 1.94 | 1.48 | 0.76** |

| 9. Compared to most people, I feel generally confused about romantic relationships. | 3.16 | 1.96 | 1.27 | 0.69** |

Adult disorganized attachment scale factor structure.

**Correlation is significant at 0.01 level. *Correlation is significant at 0.05 level. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Validity

Convergent and criterion validity

Table 3 presents the mean and standard deviation for the variables: Shutdown Dissociation, Disorganized Attachment Style, Anxious Attachment Style, Avoidant Attachment Style, and Sadism. As shown in Table 3, the Disorganized Attachment Scale has a significant positive correlation (p < 0.05) with Shutdown Dissociation, Anxious Attachment Style, Avoidant Attachment Style and Sadism, demonstrating good convergent validity for the scale.

Table 3

| Variables | Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Disorganized attachment | 27.23 (10.54) | 1 | 0.15* | 0.46** | 0.47** | 0.38** |

| 2-Shutdown dissociation (criterion validity) | 7.60 (5.46) | 1 | 0.20* | 0.12** | 0.28** | |

| 3-Anxious attachment (convergent validity) | 3.83 (0.93) | 1 | 0.15* | 0.29** | ||

| 4-Avoidant attachment (convergent validity) | 3.46 (0.76) | 1 | 0.20** | |||

| 5-Sadism (criterion validity) | 23.60 (10.25) | 1 |

Convergent and criterion validity of the disorganized attachment scale.

Correlations represent Pearson correlation coefficients. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Regression analysis

A multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine whether attachment anxiety and avoidance predict disorganized attachment. The results showed that the model was statistically significant, F(2, 199) = 61.95, p < 0.001, and accounted for 38.4% of the variance in disorganized attachment scores (R2 = 0.384, Adjusted R2 = 0.378). Both attachment anxiety (β = 0.403, p < 0.001) and avoidance (β = 0.412, p < 0.001) were significant predictors.

Reliability

The Disorganized Attachment Scale showed strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82. The item-total correlations ranged from 0.48 to 0.76, with a mean of 0.65.

Discussion

The results of the current study indicated that this Persion version of 9-item ADA is a valid and reliable scale.

The results of this study showed single-factor structure of the Persian ADA had a good fit.

The convergent and criterion validity of the Persian ADA were also investigated in our study. The convergent validity was investigated in relation with the experience in close relationships measure and criterion validity was investigated in relation with The Sadism Scale, and Shutdown Dissociation Scale.

The Disorganized Attachment Scale demonstrated good convergent and criterion validity through significant correlations with several related constructs. There was a modest but significant correlation with Shutdown Dissociation (r = 0.15, p < 0.05), supporting theoretical expectations that disorganized attachment involves dissociative symptoms. Notably, the scale showed moderate and highly significant correlations with both Anxious Attachment (r = 0.46, p < 0.01) and Avoidant Attachment (r = 0.47, p < 0.01), indicating that disorganized attachment encompasses aspects of both anxiety and avoidance in attachment behaviors. Paetzold et al. (2015) found higher correlations (r = 0.52 for Anxious Attachment, r = 0.66 for Avoidant Attachment) and reported that anxiety and avoidance together explained 52% of the variance in disorganized attachment (F(2, 496) = 267.74, p < 0.001). Similarly, our regression analysis showed that these predictors accounted for 38.4% of the variance (F(2, 199) = 61.95, p < 0.001), reinforcing that disorganization is not merely a combination of anxiety and avoidance but a distinct construct.

Additionally, the positive correlation with Sadism (r = 0.38, p < 0.01) suggests a link between disorganized attachment and sadism, emphasizing the scale’s importance in understanding attachment patterns and their implications for personality disorders and psychopathology.

The reliability analysis of the scale resulted in a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.82, indicating strong internal consistency among its items. The corrected item-total correlation coefficients of the scale were also in the expected direction and significant. In our study all items ranged from 0.48 to 0.76, which indicates satisfactory values for the scale. The findings indicated that the scale has an acceptable level of reliability.

The results are in line with the factor structure of the main version of ADA in the study by Paetzold et al. (2015).

Our findings are consistent with previous studies using the ADA, which showed strong internal consistency (α = 0.882) and significant correlations with disorganized attachment and fearful attachment styles (Pollard et al., 2020).

Additionally, large positive correlations were observed between disorganized attachment and dissociation, further supporting the ADA’s psychometric reliability (Pollard et al., 2020).

Our results are consistent with previous research on the Turkish version of the ADA scale, which showed good psychometric properties and acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79). Significant correlations with the ECR anxious and avoidant attachment subdimensions further support the scale’s validity (Erturk and Batigun, 2021).

Our study shows that the fit indices for the single-factor structure of the Disorganized Attachment Scale indicate a strong model fit. The SRMR is 0.04, suggesting a good fit, while other indices (GFI, RFI, IFI, CFI, AGFI, NFI, NNFI) range from 0.93 to 0.98, confirming the model’s quality. The RMSEA is also 0.04, supporting the model’s adequacy. These results confirm that the single-factor model is a good fit for the data, demonstrating its validity and reliability in assessing disorganized attachment.

A bunch of research and theories confirm that disorganized attachment results from complex trauma and is correlated with dissociation symptoms (Liotti, 1999b; Burback et al., 2024; Guérin-Marion et al., 2020).

As we mentioned already, in the literature of psychopathology, the common assessment of attachment styles was included in two dimensions: anxious attachment style and avoidant attachment style. In the previous researches, one study that used the two common dimensions, found that sadism is only related to avoidant attachment style (Nickisch et al., 2020), and another study, mentioned that sadism was related to anxious attachment style, while Machiavellianism was related to disorganized attachment style (Russell and King, 2016). our study found a positive correlation between sadism and disorganized attachment (r = 0.38, p < 0.01).

In an interesting study, researchers found that anxious maternal attachment indirectly predicted sexual violence (Russell and King, 2016). We recommend similar research that examines disorganized attachment with the ADA scale.

The ADA is a useful tool for assessing disorganized attachment. The main goal of this study was to investigate the validity and reliability of the Persian ADA among students in Kermanshah, Iran. The results of this study showed that the single-factor structure of the Persian ADA had a good fit.

Our results demonstrated that the Persian version of the ADA is a valid and reliable scale for assessing disorganized attachment in adulthood. Due to the lack of Persian measurement tools for assessing disorganized attachment in adult romantic relationships, no local studies have quantitatively addressed this issue. This has represented a significant gap in the Persian literature. The validation of the Persian adaptation of the ADA, as demonstrated by our study, is a crucial step in filling this gap. This scale will be valuable in future research, particularly in studies examining various psychopathologies such as borderline personality disorder, dissociative symptoms, post-traumatic stress disorder, and sadism.

Understanding disorganized attachment in adulthood, how it develops, and how it appears in adult relationships is essential for developing effective interventions (Jacobvitz and Reisz, 2019).

This study has some limitations that should be considered. First, the sample included only university students, which may limit how well the findings apply to the general population. Future studies should include more diverse participants to improve generalizability.

Second, while this study confirmed the initial reliability and validity of the ADA, it did not assess test–retest reliability. Future research should examine whether the scale produces consistent results over time.

Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable evidence for the ADA’s psychometric strength. The use of comprehensive statistical analysis supports its reliability as a measure of disorganized attachment. Future studies should further test its effectiveness in clinical settings and different cultural contexts.

In conclusion, the Persian version of the ADA is a valid and reliable tool for assessing disorganized attachment in adulthood. Its validation fills a critical gap in the Persian literature and paves the way for future research and clinical applications. By addressing the limitations of this study and incorporating additional reliability and validity measures, future research can further enhance our understanding of disorganized attachment and its implications for mental health.

Statements

Author’s note

This article includes a part of the master dissertation study conducted by Mitra Pahlavan under the advisory of Dr. Yukhabeh Mohammadian within the scope of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Clinical Psychology Master Program.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. NJ: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. BM: Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction note

A correction has been made to this article. Details can be found at: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1751064.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Ainsworth M. D. S. (1982). “The development of infant-mother attachment” in Thebeginning: Readings on infancy. ed. BelskyJ. (New York, NY: Columbia University Press), 133–143.

2

Bateman A. W . (2022). Mentalization-based treatment. Personality disorders and pathology: Integrating clinical assessment and practice in the DSM-5 and ICD-11 era. ed. HuprichS. K. (American Psychological Association), 237–258.

3

Bateman A. W. Fonagy P. (2019). Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice: American Psychiatric Pub.

4

Belsky J. (2002). Developmental origins of attachment styles. Attach Hum. Dev.4, 166–170. doi: 10.1080/14616730210157510,

5

Blizard R. A. (1997). The origins of dissociative identity disorder from an object relations and attachment theory perspective. Dissociation10, 223–229.

6

Blizard R. A. (2001). Masochistic and sadistic ego states: dissociative solutions to the dilemma of attachment to an abusive caretaker. J. Trauma Dissociation2, 37–58. doi: 10.1300/J229v02n04_03,

7

Bowlby J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Attachment, vol. 1. New York. NY: Basic Books.

8

Bowlby J. (1969/1982). Attachment and loss. New York: Basic Books.

9

Bowlby J. (1973). Attachment and loss, vol. 2. London, UK: Separation: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

10

Bowlby J. (1980). Loss: Sadness and depression. 3:472New York: Basic books.

11

Bowlby J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. London: Routledge.

12

Brennan K. A. Clark C. L. Shaver P. R . (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. Attachment theory and close relationships. eds. SimpsonJ. A.RholesW. S. (Guilford Press) 46:70–100.

13

Briere J. Runtz M. Eadie E. Bigras N. Godbout N. (2018). The disorganized response scale: construct validity of a potential self-report measure of disorganized attachment. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy11, 486–494. doi: 10.1037/tra0000396,

14

Burback L. Forner C. Winkler O. K. Al-Shamali H. F. Ayoub Y. Paquet J. et al . (2024). Survival, attachment, and healing: an evolutionary lens on interventions for trauma-related dissociation. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag.17, 2403–2431. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S402456,

15

Ebrahimi Ghavam S. (2020). Psychometric Properties of the Moshagen, Hilbig, and Zettler Nine Dark Characteristics Questionnaire (2018). Psychological Models and Methods, 11, 141–158.

16

Erturk I. S. Batigun A. D. (2021). Adult disorganized attachment scale (ADA): Turkish adaptation, validity, and reliability study. Düşünen Adam: Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences34:262.

17

Fairbairn W. (1952). Psychoanalytic studies of the personality. London: Tavistock.[→]. Routlege Keegan Paul.

18

Ferenczi S. (1988). Confusion of tongues between adults and the child: the language of tenderness and of passion. Contemp. Psychoanal.24, 196–206. doi: 10.1080/00107530.1988.10746234

19

Fraley R. C. Waller N. G. Brennan K. A. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.78, 350–365. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.350,

20

Guérin-Marion C. Sezlik S. Bureau J.-F. (2020). Developmental and attachment-based perspectives on dissociation: beyond the effects of maltreatment. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol.11:1802908. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1802908,

21

Hoffman P. M. (2006). Attachment styles and use of defense mechanisms: A study of the adult attachment projective and cramer's defense mechanism scale. TN, USA: The University of Tennessee.

22

Jacobvitz D. Reisz S. (2019). Disorganized and unresolved states in adulthood. Curr. Opin. Psychol.25, 172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.06.006,

23

Kline R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

24

Kyriazos T. A. (2018). Applied psychometrics: sample size and sample power considerations in factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in general. Psychology9, 2207–2230. doi: 10.4236/psych.2018.98126

25

Liotti G. (1992). Disorganized/disoriented attachment in the etiology of the dissociative disorders. Dissociation5, 196–204.

26

Liotti G. (1999a). Disorganization of attachment as a model for understanding dissociative psychopathology. Attachment disorganization. eds. SolomonJ.GeorgeC. (The Guilford Press). 291–317.

27

Liotti G. (1999b). Understanding the dissociative processes: the contribution of attachment theory. A topical journal for mental health professionals. Psychoanal. Inq.19, 757–783. doi: 10.1080/07351699909534275

28

Liotti G. (2006). A model of dissociation based on attachment theory and research. J. Trauma Dissociation7, 55–73. doi: 10.1300/J229v07n04_04,

29

Main M. (1981). Avoidance in the service of attachment: a working paper. Behav. Dev., 651–693.

30

Main M . (1991). Metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive monitoring, and singular (coherent) vs. multiple (incoherent) model of attachment: findings and directions for future research. Attachment across the life cycle. Routledge. 33.

31

Main M. Solomon J . (1986). Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. Affective development in infancy. eds. BrazeltonT. B.YogmanM. W. (Ablex Publishing) 95–124.

32

Main M. Solomon J . Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth strange situation. (1990).

33

Meier M. Bureau J.-F. (2018). The development, psychometric analyses and correlates of a self-report measure on disorganization and role reversal. J. Child Fam. Stud.27, 1805–1817. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1028-1

34

Meyer B. Pilkonis P. A. (2001). Attachment style. Psychotherapy: theory, research, practice. Training38, 466–472. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.38.4.466,

35

Mikulincer M. Shaver P. R . Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. The Guilford Press. (2007).

36

Molisa M. The development, psychometric analyses and correlates of a new self-report measure on disorganization and role reversal. (2015). (Doctoral dissertation, University of Ottawa). University of Ottawa.

37

Moshagen M. Hilbig B. E. Zettler I. (2018). The dark core of personality. Psychol. Rev.125, 656–688. doi: 10.1037/rev0000111,

38

Nickisch A. Palazova M. Ziegler M. (2020). Dark personalities–dark relationships? An investigation of the relation between the dark tetrad and attachment styles. Personal. Individ. Differ.167:110227. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110227

39

Paetzold R. L. Rholes W. S. Kohn J. L. (2015). Disorganized attachment in adulthood: theory, measurement, and implications for romantic relationships. Rev. Gen. Psychol.19, 146–156. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000042

40

Pollak E. Wiegand-Grefe S. Höger D. (2008). The Bielefeld attachment questionnaires: overview and empirical results of an alternative approach to assess attachment. Psychother. Res.18, 179–190. doi: 10.1080/10503300701376365,

41

Pollard C. Bucci S. Berry K. (2023). A systematic review of measures of adult disorganized attachment. Br. J. Clin. Psychol.62, 329–355. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12411,

42

Pollard C. Bucci S. MacBeth A. Berry K. (2020). The revised psychosis attachment measure: measuring disorganized attachment. Br. J. Clin. Psychol.59, 335–353. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12249,

43

Russell T. D. King A. R. (2016). Anxious, hostile, and sadistic: maternal attachment and everyday sadism predict hostile masculine beliefs and male sexual violence. Personal. Individ. Differ.99, 340–345. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.05.029

44

Schalinski I. Schauer M. Elbert T. (2015). The shutdown dissociation scale (shut-D). Eur. J. Psychotraumatol.6:25652. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.25652,

45

Shaver P. R. Mikulincer M. (2002). Attachment-related psychodynamics. Attach Hum. Dev.4, 133–161. doi: 10.1080/14616730210154171,

46

Simpson J. A. Rholes W. S. (2002). Fearful-avoidance, disorganization, and multiple working models: some directions for future theory and research. Attach Hum. Dev.4, 223–229. doi: 10.1080/14616730210154207,

47

Thompson R. A. Simpson J. A. Berlin L. J. (2021). Attachment: The fundamental questions. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Publications.

48

Tinsley H. E. Tinsley D. J. (1987). Uses of factor analysis in counseling psychology research. Couns. Psychol.34, 414–424.

49

Zhang Y. Hillman S. Pereira M. Anderson K. Cross R. M. (2025). Preliminary findings on psychometric properties of the adolescent story stem profile. Front. Psychol.16:1478372. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1478372,

Summary

Keywords

Persian adaptation, validity and reliability study adaptation, adult romantic relationships, disorganized attachment, reliability

Citation

Pahlavan M, Mohammadian Y, Jaberghaderi N and Mahaki B (2025) Adult Disorganized Attachment scale (ADA): Persian adaptation, validity, and reliability study. Front. Psychol. 16:1471538. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1471538

Received

27 July 2024

Accepted

11 April 2025

Published

22 May 2025

Corrected

15 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Gudberg K. Jonsson, University of Iceland, Iceland

Reviewed by

Shalini Munusamy, International Medical University, Malaysia

Eva Flemming, University Hospital Rostock, Germany

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Pahlavan, Mohammadian, Jaberghaderi and Mahaki.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Youkhabeh Mohammadian, yokhabe@gmail.com

ORCID: Mitra Pahlavan, orcid.org/0000-0002-7061-9621

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.