- 1College of Management and Economics, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China

- 2Centre of Gaming and Tourism Studies, Macau Polytechnic University, Macau, Macao SAR, China

This study extends the concept of organizational socialization from coworker support to its impact on shaping work–family conflict (WFC), job satisfaction, and turnover intention. Utilizing a sample of 413 female casino dealers, it investigates the interplay between coworker support, WFC, job satisfaction, and turnover intention among female employees in the Macau casino industry, focusing on the post-organizational socialization phase. The results indicate that support from coworkers significantly decreases WFC and improves job satisfaction. Both factors mediate the relationship between coworker support and turnover intention. Furthermore, WFC positively impacts turnover intention, while job satisfaction has a negative impact. These findings highlight the importance of casino management fostering supportive coworker relationships to improve job satisfaction and employee retention, thus enhancing the effectiveness of organizational socialization. This study contributes to the organizational socialization theory and provides practical implications for managing female employees in high-pressure environments.

1 Introduction

Organizational socialization is how new employees learn the values, norms, and behaviors necessary to function effectively within an organization (Bauer and Erdogan, 2011; Saks and Gruman, 2014). Nevertheless, employees’ understanding of the organization and behavior will change after organizational socialization for all individuals’ careers (Torlak et al., 2024). Behavioral reinforcement theory believes that it is necessary to continuously reinforce and consolidate the collective behaviors previously required and determined by the organization (Gavetti et al., 2012). Organizations need to consolidate the achievements of individual organizational socialization (Bauer and Erdogan, 2011; Moreland and Levine, 2014). Therefore, post-organizational socialization refers to the ongoing process of adapting and integrating into an organization after the initial socialization period (Stacey, 2018). However, studying employee organizational behavior changes from the post-organizational socialization stage is still a new perspective.

Moreover, coworker support remains in the organizational socialization strategy and refers to the assistance, understanding, and encouragement employees receive from their colleagues (Ashforth et al., 2007). This support can take various forms, including emotional, informational, and instrumental. Coworker support can be a form of positive reinforcement for organizational socialization (Saks and Gruman, 2011). For example, when colleagues recognize and appreciate each other’s contributions, it reinforces positive behaviors and encourages continued collaboration and effort. Recent attention has been given to the supportive relationships that develop among coworkers, and researchers have produced evidence that coworker support can benefit workers (Sloan, 2012; Singh et al., 2019; De Clercq et al., 2020). Base Conservation of Resources Theory, coworker support is a crucial social resource that can significantly impact employees’ well-being (Sloan, 2012) and job performance (Baker and Kim, 2021). This support can be categorized into two main types: emotional and instrumental. On the one hand, emotional support involves providing empathy, care, and understanding to colleagues, which helps alleviate work-related stress (Patterer et al., 2024) and enhance job satisfaction (Koseoglu et al., 2020; Nguyen and Tuan, 2022). On the other hand, instrumental support includes practical assistance and resources that help employees perform their tasks more efficiently. Further research suggests that instrumental support from coworkers has been linked to improved job involvement and life satisfaction by facilitating a better WFC (French et al., 2018; French et al., 2018). Many studies have examined organizational socialization as an antecedent of WFC, job satisfaction, and turnover intention (Allen and Martin, 2017; Shi et al., 2023). Still, there has been no research on the impact of sustained coworker support in post-organizational socialization on the above organizational behavior outcomes.

Additionally, female newcomers often receive less social support and mentoring than their male counterparts. However, they tend to benefit more from social tactics such as mentoring and interaction, which positively influence their role outcomes (Kowtha, 2013). Compared with male employees, as female employees grow older and gain more experience, various problems will arise in matching their family life and work environment, seriously affecting their organizations’ behavioral consequences (Norling and Chopik, 2020). However, due to their female roles, female employees are given more family demands by the outside world (Greenglass et al., 1988; Allen and Martin, 2017; Zhang et al., 2020). As female employees age and gain experience, they often encounter unique challenges in balancing their family lives and work environments. These challenges can have significant implications for their behavior and overall organizational outcomes, including the incompatibility experienced by employees between their work and family roles (Allen and Martin, 2017; Shi et al., 2023), which may lead to a decrease in job satisfaction (Netemeyer et al., 1996; Bruk et al., 2002; Grandey et al., 2005; Shi et al., 2023) and an increase in turnover intention (Huyghebaert et al., 2018; Anderson et al., 2002; Mumu et al., 2021). A study on Macau casino dealers found that over half of the participants experienced depression, a quarter had anxiety, and about two-thirds reported poor sleep quality. These issues were linked to the impacts of casino employment on family life and responsibilities (Zhou et al., 2022). The Macau casino industry presents special challenges to employees’ work-family balance due to its high salaries and shift work characteristics, especially the female dealers, as the main workforce in the casino industry and tolerate enormous work pressure (Zhou and He, 2018). Their job satisfaction and retention rates directly affect the industry’s human resources stability. However, there are still gaps in the research on WFC, job satisfaction, and turnover intention of female employees under coworker support in the post-organizational socialization context.

In light of the above discussions, this article analyzes the mutual influence and mechanism between coworker support, WFC, job satisfaction, and turnover intention in post-organizational socialization. The sample of female employees from the casinos in Macau was examined to determine how WFC and job satisfaction mediate the relationship between coworker support and turnover intention. It will contribute to the theory of organizational socialization strategy and provide practical guidance for managing female employees in the Macau casino industry.

2 Literature review

2.1 Coworker support and turnover intention

Coworker support refers to the assistance and encouragement provided by colleagues in the workplace (Nazir et al., 2016; Singh et al., 2019; De Clercq et al., 2020). In the workplace, coworker support, as a work resource, is a key resource in reducing employee turnover intention (De Clercq et al., 2020; Chung et al., 2021). When unfriendly coworker relationships hinder employees from fulfilling their job responsibilities or hinder their career development, it may stimulate employees’ turnover intention (Karatepe and Olugbade, 2017). On the contrary, employees who receive coworker support have a lower intention to resign. For example, coworker support can improve the well-being of an employee by reducing stress, role conflict, and role overload (Chiaburu and Harrison, 2008; Norling and Chopik, 2020). It also improves the working environment and stimulates positive feelings and self-esteem, which gives employees more strength and energy to cope with challenges in their work (Singh et al., 2019).

Turnover intention refers to the behavior of an employee who intends to resign but has not yet taken actual action and is a key concern for organizations (Porter and Steers, 1973; Pitts et al., 2011; Li and Yao, 2022). High turnover rates can result in additional costs for recruiting, selecting, and training new members. Thus, it will disrupt the organization’s operations and incur significant costs (Tews et al., 2013; Jolly et al., 2021; McCartney et al., 2022).

Social support from supervisors and co-workers significantly influences employees’ intention to stay. Group cohesiveness and social networks also play a mediating role in enhancing retention (Sundari et al., 2024). Coworker support is essential during socialization, helping newcomers adjust to organizational norms and reducing stress and uncertainty (Singh et al., 2019). Coworker support aids new employees’ emotional and social integration (Sloan et al., 2013). The quality of relationships with co-workers and managers can significantly influence how individuals adapt to new roles or transition out of the organization (Hatmaker, 2015). Based on the Conservation of Resources Theory, De Clercq et al. (2020) found that coworker support can alleviate employees’ work stress and thus reduce their turnover intention. Based on the above discussion, the present paper assumes that coworker support positively impacts the turnover Intention of Female employees and decreases turnover intention. Hence, the following hypothesis is stated:

H1: Coworker support negatively impacts turnover intention.

2.2 Coworker support, WFC, and job satisfaction

The issue of WFC has garnered increasing attention in recent years (Namasivayam and Mount, 2004; Allen and Martin, 2017; Shi et al., 2023). WFC is a specific type of inter-role conflict that arises from the incompatibility of role pressures between the work and family domains. Conflicts in role interaction can emerge while irreconcilable contradictions arise between work and family roles (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985; Mumu et al., 2021). Research has shown that women tend to experience a stronger conflict between these roles than men (Greenglass et al., 1988; Allen and Martin, 2017; Zhang et al., 2020).

Job satisfaction was first proposed by Hoppock (1935), who believed that psychological and physiological satisfaction with the work environment and the work itself. Recent studies have shown that employees are increasingly concerned about the work environment, personal development, and interpersonal interactions, directly or indirectly affecting their job satisfaction (Pu et al., 2024).

Furthermore, coworker support can be one of the key methods to resolve WFC (Norling and Chopik, 2020). French et al. (2018) have analyzed the relationship between social support and WFC and found that social support, especially from colleagues, can significantly reduce the degree of WFC. In Zhang et al.'s (2020) study, a sample of 764 female nurses and doctors was analyzed to reveal that colleague support, as an important component of social support, plays a crucial role in alleviating work stress caused by WFCs, reducing emotional exhaustion, and improving the psychological well-being of female workers, and can have a positive impact. Coworker support aids new employees’ emotional and social integration to enhance their well-being and job satisfaction (Yucel and Minnotte, 2017). Coworker support significantly influences job satisfaction across various occupations and industries. Coworker support directly enhances job satisfaction as employees who perceive higher support from their coworkers report greater job satisfaction (Koseoglu et al., 2020; Nguyen and Tuan, 2022). Emotionally, coworker support can enhance employees’ sense of belonging and teamwork, improving job satisfaction (Norling and Chopik, 2020; Nguyen and Tuan, 2022). In practical work, supporting colleagues can enhance teamwork, reduce work pressure, and improve job satisfaction (Macias-Velasquez et al., 2021; Gordon and Adler, 2022). Coworker support indirectly affects job satisfaction via WFC in women but not men (Matijaš et al., 2018). Based on the above reviews, the following hypothesis is stated:

H2: Coworker support negatively impacts WFC.

H3: Coworker support positively impacts job satisfaction.

2.3 WFC, job satisfaction, and turnover intention

Bucks studies reveal that WFC negatively correlates with job satisfaction (Netemeyer et al., 1996; Bruk et al., 2002; Grandey et al., 2005; Shi et al., 2023). The negative effects experienced by women due to WFC are more significant (Greenglass et al., 1988; Bruk et al., 2002; Ergeneli et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2020). Greenglass et al. (1988) argued that women experience a stronger sense of conflict between work and family roles, and this WFC leads to reduced job satisfaction. Beatty (1996) found that Canadian female professionals and managers experience a decline in job satisfaction when they feel WFC. Women face greater challenges in balancing work and family responsibilities, particularly in high-stress professions such as nursing, where the negative impact of WFC on women’s job satisfaction is especially significant (Grzywacz et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2020).

Moreover, WFC is an essential determinant of turnover intention (Huyghebaert et al., 2018). Employees feel stressed and dissatisfied when experiencing conflicts between work and family, which may lead them to consider leaving their current positions for a better work-life balance (Anderson et al., 2002; Mumu et al., 2021). Huang and Cheng (2011) found that WFC significantly impacts job stress for female employees, and this increased job stress further reinforces their intention to leave. Yildiz et al. (2021) examined the relationship between nurses’ WFC and turnover intention and found that WFC and turnover intention are both significantly correlated factors. Additionally, job satisfaction negatively impacts turnover intentions because it reduces the likelihood of employees entertaining thoughts of leaving their positions (Tett and Meyer, 1993). Bucks studies verified that higher job satisfaction will reduce employee turnover intention (Tsai and Wu, 2010; Tschopp et al., 2014). Across various contexts, such as teaching and nursing, it has been consistently demonstrated that enhancing job satisfaction can serve as a strategy to reduce employees’ turnover intention (De Cuyper et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2022). Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4: WFC negatively impacts job satisfaction.

H5: WFC positively influences turnover intention.

H6: Job satisfaction negatively impacts turnover intention.

2.4 Coworker support, WFC, job satisfaction, and turnover intention

The coworker relationship is one important factor that impacts turnover intention (Cotton and Tuttle, 1986). Coworker support, as an important resource in the workplace, positively impacts employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Singh et al., 2019; De Clercq et al., 2020; Kmieciak, 2022). According to social exchange theory (SET), employees who perceive support from their coworkers are likely to exhibit more positive organizational behaviors (Akgunduz and Eryilmaz, 2018). Similarly, coworker support also reduces employee disengagement behaviors or turnover intentions (Chung et al., 2021; Kmieciak, 2022). However, the increase in WFC may weaken the impact of coworker support on employees’ turnover intention (Zhou et al., 2022). A meta-analytic review aimed to explore the relationship between nurses’ WFCs and turnover intentions, indicating a moderate, positive, and significant relationship between WFC and turnover intention (Yildiz et al., 2021).

In addition, job satisfaction significantly reduces turnover intention across different sectors (Bright, 2021; Pu et al., 2024) and significantly negatively impacts turnover intention (Zhang et al., 2022). The coworker relationship is key to job satisfaction (Cotton and Tuttle, 1986; Yildiz et al., 2021). Job satisfaction serves as a mediator in the relationship between various forms of support and turnover intention. For example, perceived organizational support influences turnover intentions through job satisfaction (Sharif et al., 2021). Similarly, Le et al. (2023) mention job satisfaction as a mediator between family support and turnover intention. Based on the above discussions, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H7: WFC mediates the relationship between coworker support and turnover intention.

H8: Job satisfaction mediates the relationship between coworker support and turnover intention.

H9: WFC and job satisfaction sequentially mediate the relationship between coworker support and turnover intention.

3 Methodology

3.1 Scale

The study includes independent variables such as coworker support, work–family conflict, and job satisfaction, with turnover intention as the dependent variable. The measurement tool for perceived coworker support draws mainly from the Organizational Socialization Inventory (OSI) questionnaire developed by Taormina (1994). It results in five scales for perceived coworker support, for example, “Coworkers have helped me on the job in various ways.” The measurement tool for WFC adopts scales from the WFC questionnaires Carlson et al. (2000) and Grandey and Cropanzano (1999). It comprises four measurement indicators for WFC, for example, “My work takes time away from my family and friends.” The measurement tool for job satisfaction refers to scales by Spector et al. (2007) and Judge et al. (2020). It includes four indicators for job satisfaction, for example, “I am satisfied with my current fulfilling career.” The measurement tool for turnover intention is based on scales by Bothma and Roodt (2013) and Singh et al. (1996). It yields three measurement indicators for turnover intention, for example, “I’ve seriously considered changing organizations.”

A back-translation procedure was employed to ensure content validity (Beaton et al., 2000; Son et al., 2000). The measurement was originally developed in English and subsequently translated into Chinese by two independent professionals proficient in English and Chinese. This meticulous translation process aimed to ensure the accuracy and integrity of the instrument’s content in both languages. A 5-point Likert-type scale was adopted, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was chosen for this study due to its suitability for explaining complex relationships and effectively addressing issues such as unacceptable solutions and factor uncertainty (Fornell and Bookstein, 1982). Additionally, SPSS 26.0 was employed as another statistical tool. The evaluation of PLS-SEM followed the recommended two-step systematic approach, beginning with the measurement model assessment and then proceeding to the structural model, as suggested by Hair et al. (2013). The research model underwent testing using Smart PLS 3.2.9.

3.2 Data

This study focuses on the dealers of six casino enterprises in Macau. A non-random convenience sampling method was employed for questionnaire surveys to obtain the necessary data for this research. Before the formal investigation, a pre-test analysis of the questionnaire was conducted to identify potential issues with the scale, eliminate invalid items, and enhance the reliability and validity of the scale. A pre-test was administered to 22 dealers to avoid missing data from the questionnaire. After collecting the pre-test questionnaires, IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 was used as an analytical tool. Cronbach’s α coefficient was employed to verify the reliability of the questionnaire and measure the reliability, stability, and internal consistency among items. The specific Cronbach’s α data are as follows: coworker support (0.835), WFC (0.794), job satisfaction (0.839), and turnover intention (0.811), indicating a high level of reliability for the scale used in this study.

Based on the results of the pre-test analysis, the questionnaire was appropriately revised to form the final version, which was then officially distributed. The survey team consisted of four students who served as dealers in casinos. The questionnaire survey was conducted at the casinos’ exit, utilizing closed-ended questions and random sampling in the questionnaire design. The survey period was from November 5, 2023, to December 20, 2023. 500 questionnaires were distributed, and 413 valid questionnaires were collected, resulting in an effective response rate of 82.6%.

3.3 Sample

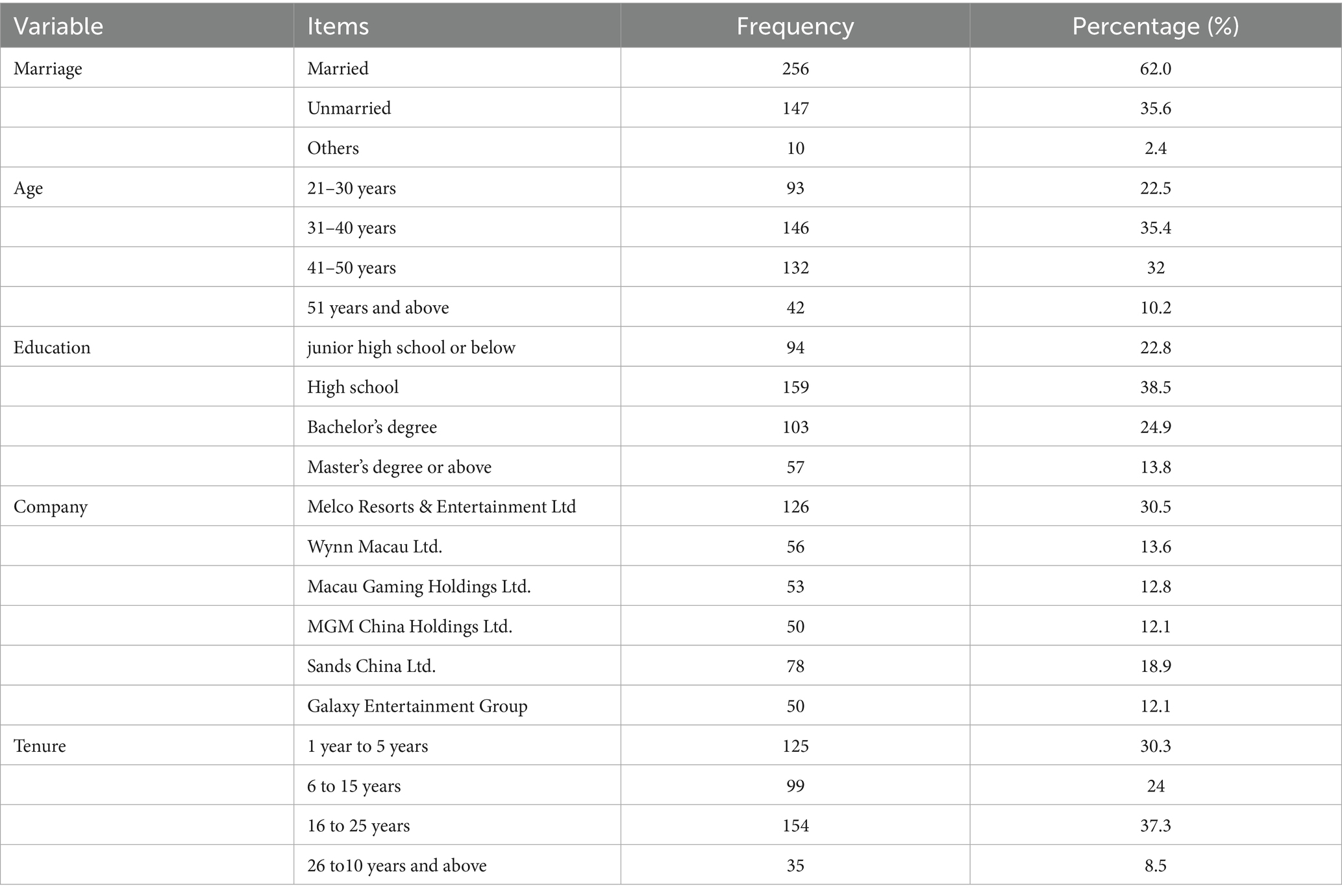

Table 1 presents the demographic data for the 413 collected samples. The sample in Table 1 consists of 413 participants, with a predominance of married individuals (62.0%), followed by unmarried (35.6%), and a small group classified as “others” (2.4%). Age distribution indicates that the largest segment is between 31 and 40 years (35.4%), with 41–50 years close behind (32.0%), while those aged 21–30 years and 51 years and above represent 22.5 and 10.2%, respectively. Regarding education, 38.5% have completed high school, 24.9% hold bachelor’s degrees, 22.8% have junior high or lower education, and 13.8% possess a master’s degree or higher. Regarding employment, Melco Resorts & Entertainment Ltd. is the most represented company (30.5%), followed by Sands China Ltd. (18.9%) and others. For position tenure, a significant majority (37.3%) have been in their roles for 16 to 25 years, while 30.3% have been employed for 1 to 5 years. Overall, this sample reflects a diverse demographic with a strong representation of experienced professionals in the casino industry.

3.4 Measures

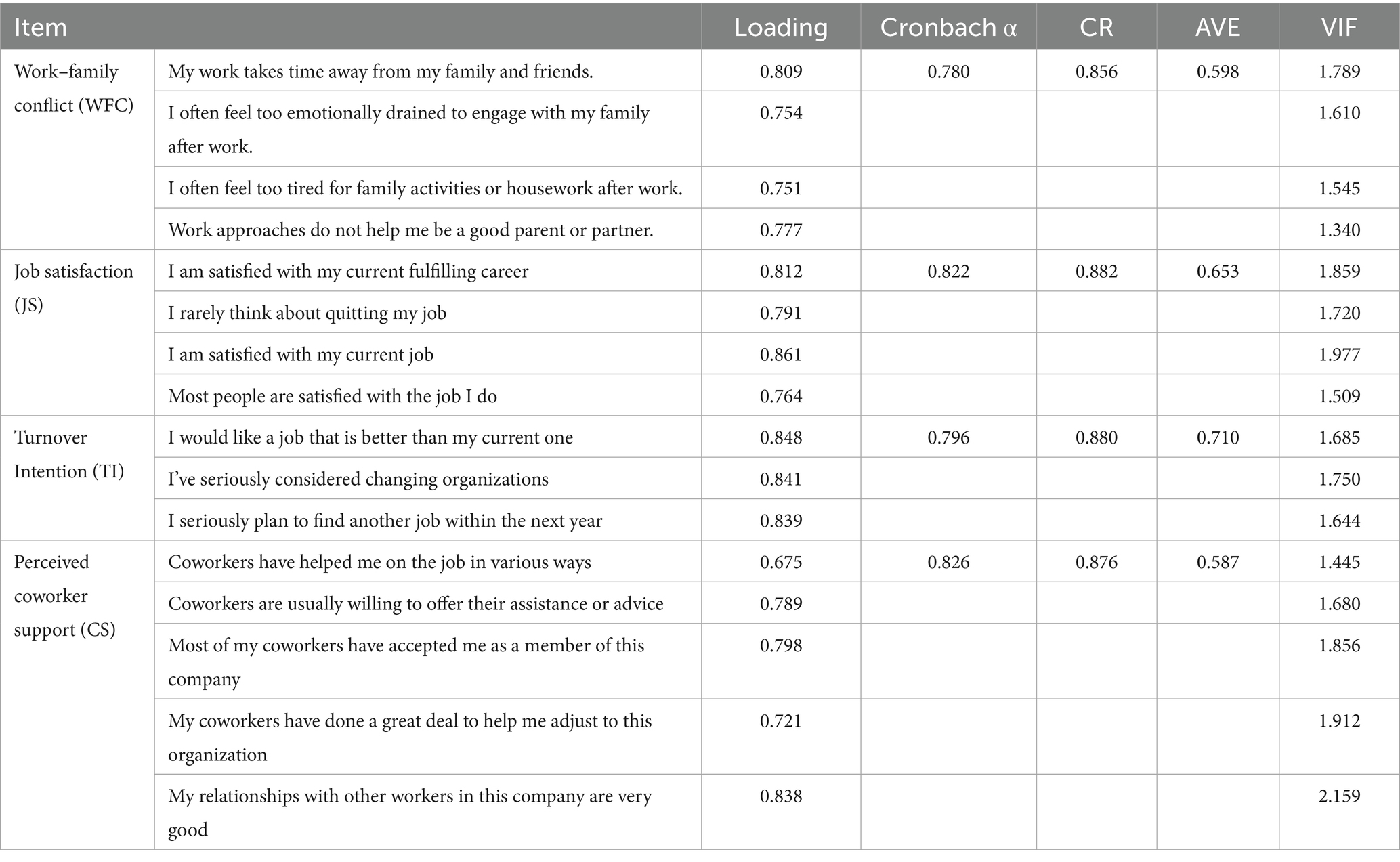

Table 2 presents measurement results of reliability, including internal consistency, convergence, and discriminant validity. Each item demonstrates strong factor loadings, with WFC items ranging from 0.751 to 0.809, indicating a robust relationship between the measured aspects of WFC and the underlying construct. The Cronbach’s alpha values for WFC (0.780), JS (0.822), TI (0.796), and CS (0.826) suggest good internal consistency across these scales (Nunnally, 1978). The Composite Reliability (CR) values for each construct further affirm their reliability, with WFC (0.856), JS (0.882), TI (0.880), and CS (0.876), respectively. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values are satisfactory, with WFC (0.598), JS (0.693), TI (0.710), and CS (0.587), indicating that the constructs explain a significant portion of the variance in their respective items (Hair et al., 2009). Notably, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values are below the threshold of 5, suggesting that multicollinearity is not a concern. Overall, the CFA results indicate that the constructs are well-defined and reliable, providing a solid basis for further analysis.

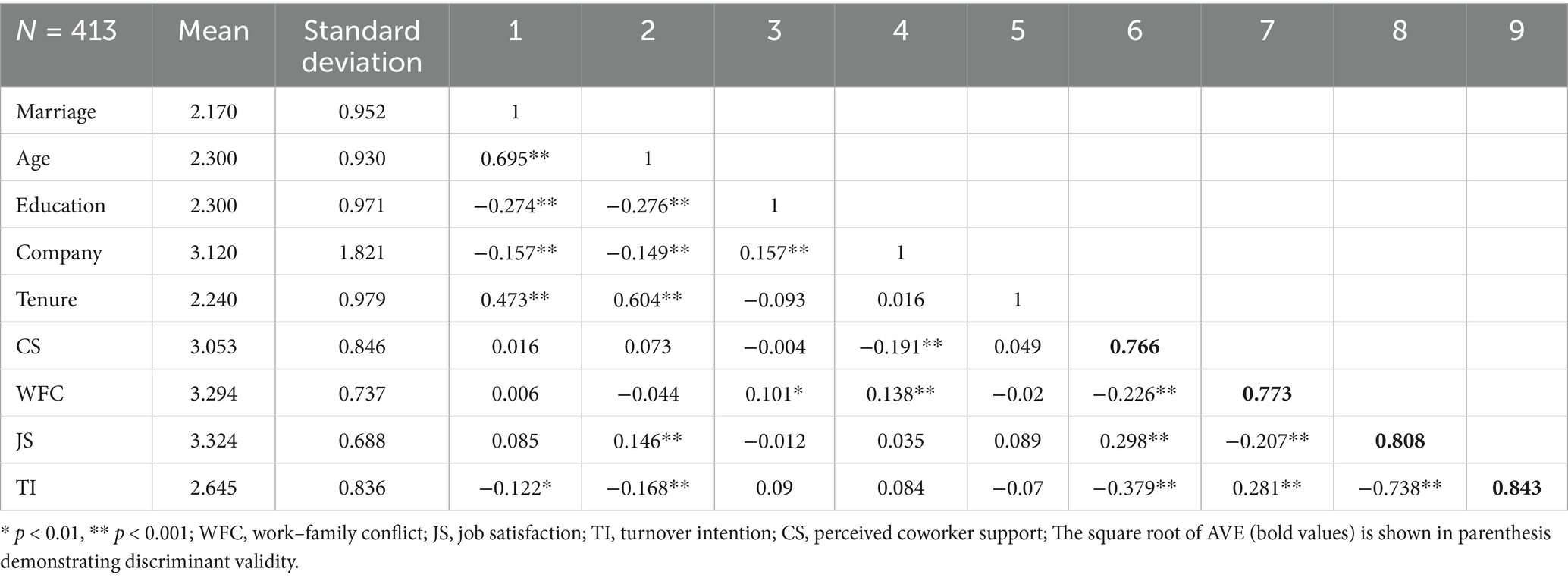

While the average variance extracted (AVE) was higher than 0.5, we can still accept values as low as 0.4. According to Fornell and Bookstein (1982), if the AVE is less than 0.5 but the composite reliability (CR) is higher than 0.7, the convergent validity of the construct is still acceptable. The value of the square root of AVE (as shown in Table 3) was significantly higher than the correlation coefficient of the construct with other constructs, indicating that convergent validity is quite high (Hair et al., 2014). All constructs exhibited strong discriminant validity, with AVE scores > 0.5 and higher square roots of AVE than correlations with other constructs.

The model was examined with the unweighted least squares discrepancy (d_ULS) value of 0.735, the geodesic discrepancy (d_G) value of 0.232, indicating covariance matrix matches the observed covariance matrix. The Normed Fit Index (NFI) value of 0.797, the Chi-square value of 568.057, and the SRMR value of 0.074 were acceptable values. Therefore, all indicators met the model’s standards, and the model fit was good.

4 Results

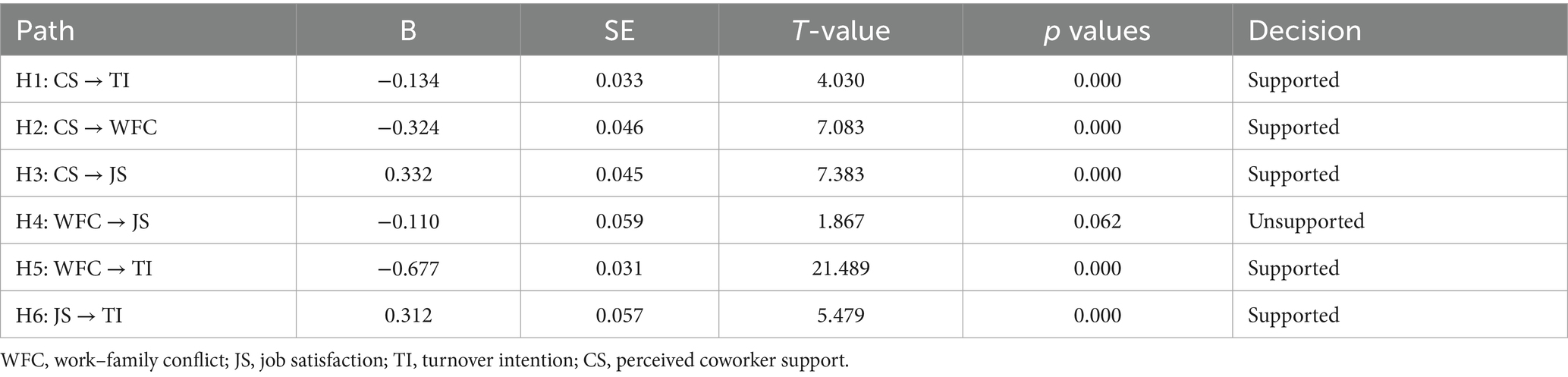

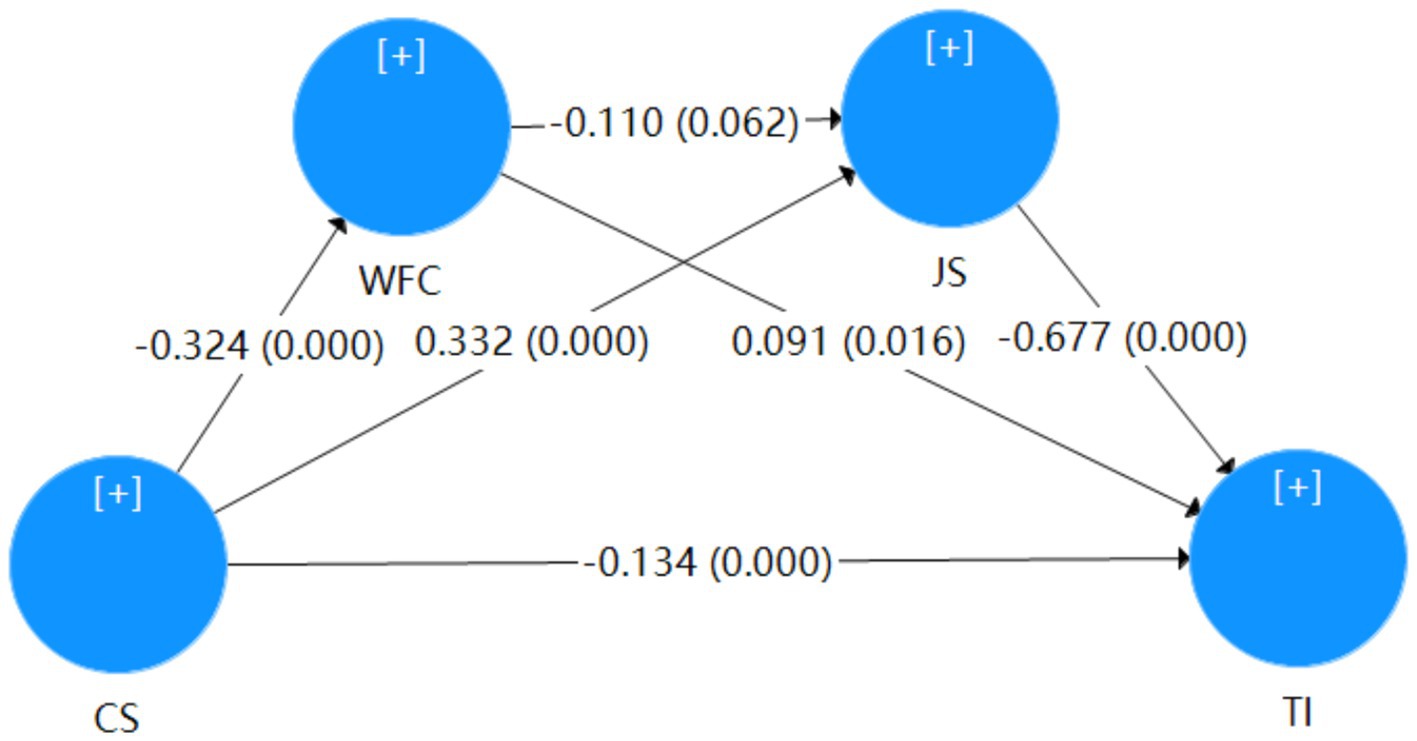

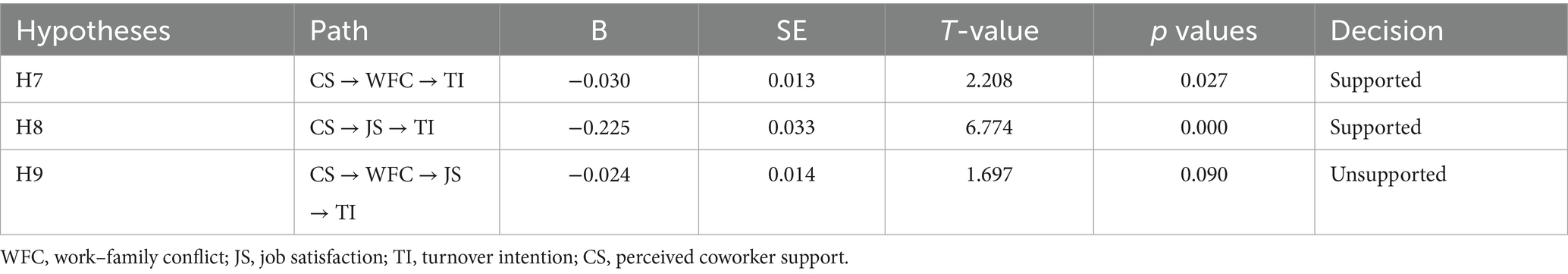

Table 4 summarizes the results of the path analysis, evaluating the relationships among perceived coworker support (CS), WFC, job satisfaction (JS), and turnover intention (TI). It shows that all hypothesized paths except one are supported. Specifically, CS negatively influences TI (B = −0.134, p < 0.001), H1 was supported, CS significantly reduces WFC (B = −0.324, p < 0.001), and positively influences JS (B = 0.332, p < 0.001), H2 and H3 were supported. However, the path from WFC to JS is only marginally significant (B = −0.110, p = 0.062), H4 was unsupported, and WFC has a strong negative impact on TI (B = −0.677, p < 0.001), H5 was supported. Lastly, JS positively affects TI (B = 0.312, p < 0.001), and H6 was supported. The path coefficients for the model are shown in Figure 1.

Table 5 presents the results of the mediation effect analysis, exploring how perceived coworker support (CS) influences turnover intention (TI) through WFC and job satisfaction (JS). Hypothesis 7 (H7) indicates a significant mediation effect where CS negatively impacts TI through WFC (B = −0.030, p = 0.027); H7 was supported. Hypothesis 8 (H8) also finds strong support, with CS leading to decreased TI via enhanced job satisfaction (B = −0.225, p < 0.001), and H8 was supported. However, Hypothesis 9 (H9), which posits a mediation pathway of CS influencing TI through WFC and then JS, is unsupported (B = −0.024, p = 0.090).

5 Discussions and conclusions

The present study developed a model to analyze the relationship between coworker support, WFC, job satisfaction, and turnover intention. The collected sample data from full-time female employees in six casino enterprises in Macau were employed to examine all presented hypotheses. The detailed findings and conclusions are outlined as follows:

5.1 Discussions

Firstly, the study found that coworker support positively impacts job satisfaction, while coworker support negatively impacts turnover intention and WFC, which is consistent with previous studies (French et al., 2018; Koseoglu et al., 2020; Nguyen and Tuan, 2022). It shows that coworker support is a significant factor that positively influences job satisfaction for female dealers in the Macau casino industry. Coworker support can enhance a sense of receiving support and recognition, meet their social needs and sense of belonging, and thus improve job satisfaction. In practical work, colleague support can enhance teamwork, reduce work pressure, and improve job satisfaction (Macias-Velasquez et al., 2021; Gordon and Adler, 2022). Coworkers’ support can help female employees enhance teamwork, reduce work pressure, and improve job satisfaction (Macias-Velasquez et al., 2021; Gordon and Adler, 2022). Coworker support negatively influences turnover intention, aligning with De Clercq et al. (2020) findings. In the casino industry, female dealers face greater work pressure from factors such as high-intensity work pace, complex customer service demands, and uncertainty in career development (Zhou and He, 2018). These pressures not only affect the physical and mental health of female dealers but also significantly increase their intention to resign. However, coworker support can alleviate female dealers’ work pressure and improve their job satisfaction and organizational cohesion. When female dealers feel accepted and recognized by their colleagues, their sense of belonging to their work will increase, reducing their intention to resign. In addition, cooperation and support among colleagues can help female dealers better cope with challenges in their work, giving them more confidence when facing work pressure. Therefore, in the casino industry, enhancing coworker support is crucial for improving the retention of female employees during the post-organizational socialization process.

Secondly, the results of this study indicate that WFC positively influences turnover intention, while job satisfaction negatively impacts turnover intention. It shows that WFC is a significant factor that positively influences turnover intention (Anderson et al., 2002; Mumu et al., 2021). Female dealers often face more expectations of family responsibilities from the outside world and their families due to gender reasons. The particularity of working in the Macau casino industry exacerbates this phenomenon, making it easier for female dealers to have conflicts between their responsibilities in the workplace and their expectations at home (Zhou et al., 2022). This conflict often leads them to need to balance work and family, and when they feel that work pressure is too great and affects the care of their families, they increase their tendency to resign. Job satisfaction negatively impacts turnover intention, aligning with the findings of Zhang et al. (2022). As mentioned, the casino industry is characterized by a fast-paced work environment. Female dealers face not only workplace pressures but also expectations and demands from the outside world and their families. In this context, female dealers’ job satisfaction reduces turnover intentions and increases their willingness to remain in the industry for post-organizational socialization.

Thirdly, the results of this study demonstrate that both WFC and job satisfaction mediate the relationship between coworker support and turnover intention. Specifically, the impact of coworker support on employee turnover intention can be conveyed through WFC (Yildiz et al., 2021). Female dealers in the casino industry need to receive support and assistance from coworkers when facing high-pressure work. Coworker support reduces WFCs caused by work for female dealers, enabling them to achieve a work-family balance. Therefore, turnover intention has been reduced, which helps maintain the stability of the workforce. In addition, the results of this study reveal that the relationship between coworker support and turnover intention can be achieved through job satisfaction (Zhang et al., 2022). When female dealers in the casino industry feel positive support from their coworkers, their job satisfaction will significantly increase. Coworker support can help them cope with work pressure and enhance their sense of belonging and team cohesion. With the improvement in job satisfaction, the turnover intention of female dealers in the casino industry will significantly decrease.

In addition, the results of this study found that WFC does not significantly negatively impact job satisfaction, indicating that the factor of WFC did not influence female dealers’ perceived satisfaction with their jobs. It can be explained that antecedents of job satisfaction are various, and can be different in varied contexts. In Macao, employees in casinos earn higher incomes than those in other sectors, which attracts many residents to join the industry. Thus, WFC cannot be a key factor impacting job satisfaction. Furthermore, the findings of this study do not support the hypothesis that Work–Family Conflict (WFC) and job satisfaction sequentially mediate the relationship between coworker support and turnover intention. This can be attributed to the fact that female dealers experience heightened work stress, which leads to increased turnover intention, as noted by Zhou et al. (2022), rather than WFC itself. Therefore, while coworker support often benefits employee retention, its impact may be diminished in high-stress environments. This suggests that organizations need to enhance the nature and quality of support provided among coworkers to address the specific needs of female dealers from a family perspective.

Finally, the findings of this article reveal several important relationships regarding female dealers’ demographics and their implications for turnover intention and job satisfaction. Specifically, age and marital status correlate negatively with turnover intention, suggesting that elderly and married female dealers are less likely to consider leaving their jobs. Moreover, age also shows a positive correlation with job satisfaction, which implies that, like organizational socialization, they may find more fulfillment and contentment in their roles. On the other hand, education and company affiliation are positively correlated with WFC. This indicates that female dealers with higher education levels and those employed by certain companies may face greater challenges balancing their professional and personal lives. Additionally, company affiliation has a negative correlation with perceived coworker support. This suggests that female dealers within certain companies may feel less supported by their colleagues, which could further exacerbate feelings of isolation or stress, particularly in high-pressure environments. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for post-organizational socialization aiming to improve employee retention and satisfaction by fostering a supportive workplace culture.

5.2 Theoretical implications

The theoretical contributions of this study to the concept of post-organizational socialization lie in its exploration of the role of coworker support, work–family conflict, job satisfaction, and turnover intention within the context of the Macau casino industry, particularly for female employees. By focusing on post-organizational socialization, the study extends the existing literature on socialization processes by highlighting how these post-socialization factors influence employees’ adaptation and integration into the organization after initial onboarding. Specifically, the study underscores the mediating role of job satisfaction and work–family conflict in the relationship between coworker support and turnover intention, which has not been extensively explored in previous research. Previous studies have emphasized the importance of coworker support in reducing work-related stress and increasing job satisfaction (e.g., French et al., 2018; Koseoglu et al., 2020), but this study contributes to the theoretical literature by highlighting that coworker support influences turnover intention through both WFC and job satisfaction. The findings suggest that coworker support, by enhancing job satisfaction and reducing work–family conflict, significantly contributes to dropping turnover intention, thus promoting the stability of the workforce during the post-socialization phase. This contributes to a more nuanced understanding of post-organizational socialization by emphasizing the importance of interpersonal relationships and work-life balance in employee retention and long-term organizational commitment.

Moreover, the findings challenge some established assumptions regarding the direct impact of WFC on job satisfaction. While the literature often suggests that WFC has a detrimental effect on job satisfaction (e.g., Allen et al., 2000), this study did not find a significant negative impact of WFC on job satisfaction. This divergence could be attributed to the unique characteristics of the casino industry, where higher income levels and other contextual factors might buffer the typical negative consequences of WFC. This implies that future research should consider contextual variables, such as industry-specific factors or demographic influences, when assessing the broader applicability of WFC theories.

Finally, this study clarifies the mediating mechanism by which coworker support reduces turnover intention by alleviating WFC and increasing job satisfaction, providing a new perspective for understanding the complex role of coworker support in organizational behavior and laying the foundation for future research on the relationship between coworker support and other organizational variables.

5.3 Practical implications

This study offers valuable insights for organizational leaders, human resource managers, and policymakers in the casino industry, particularly those concerned with employee retention and job satisfaction. The discovery that support from coworkers significantly reduces turnover intention and alleviates work–family conflict has important implications for workplace interventions. For casino operators, fostering a supportive work environment where employees feel recognized, valued, and assisted by their colleagues could be a key strategy for retaining female employees, particularly in high-stress roles of a casino dealer. Interventions such as team-building activities, mentoring programs, and promoting a collaborative work culture may improve coworker support and reduce work–family conflict.

Secondly, the study highlights the importance of addressing WFC, particularly for female dealers who may face greater familial expectations. Casino operators should consider implementing policies that support work-life balance, such as flexible scheduling, childcare assistance, or more generous family leave policies, to help mitigate the negative impacts of WFC. This will enhance job satisfaction and decrease turnover intention among female dealers who may be balancing demanding work schedules with family obligations.

In addition, the study emphasizes the importance of increasing job satisfaction in reducing turnover intention. Casino operators should improve the working environment, optimize compensation and benefits, and provide career development opportunities to enhance dealers’ job satisfaction and identification, making them more willing to stay in the company for the long term.

Lastly, the study’s finding that certain demographic factors, such as age, marital status, and education level, influence turnover intention and WFC provides practical guidance for tailoring organizational policies. For example, older and married female dealers may benefit from specific retention strategies focused on job satisfaction and work-life balance. In contrast, younger or less experienced dealers might need extra support and training to handle the challenges of the casino environment. Understanding these demographic nuances can help managers design effective interventions and improve employee retention.

5.4 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study underscores the critical role of coworker support in enhancing job satisfaction and reducing turnover intention among female dealers in the Macau casino industry. The findings reveal that coworker support not only mitigates work–family conflict (WFC) but also fosters a sense of belonging, which is essential for employee retention. While WFC was found to influence turnover intention, it did not significantly impact job satisfaction, highlighting the unique context of the casino environment where higher income levels may buffer typical negative effects.

Moreover, the mediating roles of job satisfaction and WFC in the relationship between coworker support and turnover intention provide new insights into post-organizational socialization. This study emphasizes the need for casino operators to cultivate a supportive workplace culture and implement policies that promote work-life balance, ultimately enhancing employee satisfaction and stability within the workforce. By addressing the specific needs and challenges faced by female dealers, organizations can significantly reduce turnover intention and improve overall employee well-being.

6 Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the sample is limited to full-time female employees in six casino enterprises in Macau, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other industries or regions with different cultural, economic, or organizational contexts. Expanding the sample to include male employees or those from other sectors could enhance the external validity of the results. Second, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw causal inferences between the variables. A longitudinal or experimental design would provide stronger evidence of causality by examining how coworker support, work–family conflict, job satisfaction, and turnover intention evolve. Third, the study relies on self-reported data, which may be subject to biases like social desirability or recall bias, and future research could benefit from incorporating objective measures such as turnover records or supervisor assessments. Fourth, while important demographic variables such as age, marital status, and education level are considered, other factors such as personality traits, leadership styles, and organizational culture may also influence the relationships studied, warranting further exploration of these variables. Finally, the study does not explore industry-specific factors that may uniquely impact the work-family dynamics and job satisfaction of female employees in the casino industry, such as irregular working hours, job security, or career advancement opportunities, which could mitigate the effects of work–family conflict and turnover intentions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the patients/participants or patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

YB: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Validation. JZ: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Macao Polytechnic University Foundation (RP/CJT-02/2023).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akgunduz, Y., and Eryilmaz, G. (2018). Does turnover intention mediate the effects of job insecurity and co-worker support on social loafing? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 68, 41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.09.010

Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E., Bruck, C. S., and Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 5:278.

Allen, T. D., and Martin, A. (2017). The work-family interface: a retrospective look at 20 years of research in JOHP. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 22, 259–272. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000065

Anderson, S. E., Coffey, B. S., and Byerly, R. T. (2002). Formal organizational initiatives and informal workplace practices: Links to work-family conflict and job-related outcomes. Journal of Management 28, 787–810. doi: 10.1177/014920630202800605

Ashforth, B. E., Sluss, D. M., and Harrison, S. H. (2007). Socialization in organizational contexts. Int. Rev. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2007, 1–70. doi: 10.1002/9780470753378.ch1

Baker, M. A., and Kim, K. (2021). Becoming cynical and depersonalized: how incivility, co-worker support, and service rules affect employee job performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 33, 4483–4504. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-01-2021-0105

Bauer, T. N., and Erdogan, B. (2011). “Organizational socialization: The effective onboarding of new employees” in APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. ed. S. Zedeck, Maintaining, expanding, and contracting the organization, vol. 3 (American Psychological Association), 51–64. doi: 10.1037/12171-002

Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., and Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 25, 3186–3191.

Beatty, C. A. (1996). The stress of managerial and professional women: is the price too high? J. Organ. Behav. 17, 233–251. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199605)17:3<>3.0.CO;2-V

Bothma, C. F., and Roodt, G. (2013). The validation of the turnover intention scale. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 11, 1–12. doi: 10.4102/sajhrm.v11i1.507

Bright, L. (2021). Does perceptions of organizational prestige mediate the relationship between public service motivation, job satisfaction, and the turnover intentions of federal employees? Public Pers. Manag. 50, 408–429. doi: 10.1177/0091026020952818

Bruk, C. S., Allen, T. D., and Spector, P. E. (2002). The relation between work-family conflict and job satisfaction: a finer-grained analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 60, 336–353. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2001.1836

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., and Williams, L. J. (2000). Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work-family conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 56, 249–276. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1999.1713

Chiaburu, D. S., and Harrison, D. A. (2008). Do peers make the place? Conceptual synthesis and meta-analysis of coworker effects on perceptions, attitudes, OCBs, and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 93, 1082–1103. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.5.1082

Chung, H., Quan, W., Koo, B., Ariza-Montes, A., Vega-Muñoz, A., Giorgi, G., et al. (2021). A threat of customer incivility and job stress to hotel employee retention: do supervisor and co-worker supports reduce turnover rates? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:6616. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126616

Cotton, J. L., and Tuttle, J. M. (1986). Employee turnover: a meta-analysis and review with implications for research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 11, 55–70. doi: 10.2307/258331

De Clercq, D., Azeem, M. U., Haq, I. U., and Bouckenooghe, D. (2020). The stress-reducing effect of coworker support on turnover intentions: moderation by political ineptness and despotic leadership. J. Bus. Res. 111, 12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.064

De Cuyper, N., Mauno, S., Kinnunen, U., and Mäkikangas, A. (2011). The role of job resources in the relation between perceived employability and turnover intention: a prospective two-sample study. J. Vocat. Behav. 78, 253–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.09.008

Ergeneli, A., Ilsev, A., and Karapınar, P. B. (2010). Work–family conflict and job satisfaction relationship: the roles of gender and interpretive habits. Gend. Work. Organ. 17, 679–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0432.2009.00487.x

Fornell, C., and Bookstein, F. L. (1982). Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. Journal of Marketing Research 19, 440–452.

French, K. A., Dumani, S., Allen, T. D., and Shockley, K. M. (2018). A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and social support. Psychol. Bull. 144, 284–314. doi: 10.1037/bul0000120

Gavetti, G., Greve, H. R., Levinthal, D. A., and Ocasio, W. (2012). The behavioral theory of the firm: assessment and prospects. Acad. Manag. Ann. 6, 1–40. doi: 10.5465/19416520.2012.656841

Gordon, S., and Adler, H. (2022). Challenging or hindering? Understanding the daily effects of work stressors on hotel employees’ work engagement and job satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 103:103211.

Grandey, A. A., and Cropanzano, R. (1999). The conservation of resources model applied to work-family conflict and strain. J. Vocat. Behav. 54, 350–370. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1998.1666

Grandey, A., Cordeiro, L. B., and Crouter, A. C. (2005). A longitudinal and multi-source test of the work-family conflict and job satisfaction relationship. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 78, 305–323. doi: 10.1348/096317905X26769

Greenhaus, J. H., and Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review 10, 76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103211

Greenglass, E. R., Pantony, K.-L., and Burke, R. J. (1988). A gender-role perspective on role conflict, work stress and social support. J. Soc. Behav. Pers. 3, 317–328.

Greenhaus, J. H., and Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: a theory of work-family enrichment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 31, 72–92. doi: 10.5465/amr.2006.19379625

Grzywacz, J. G., Frone, M. R., Brewer, C. S., and Kovner, C. T. (2006). Quantifying work–family conflict among registered nurses. Research in Nursing & Health 29, 414–426.

Hair, F.Jr, Gabriel, M. L., and Patel, V. K. (2014). AMOS covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on its application as a marketing research tool. REMark: Revista Brasileira de Marketing, 13.

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning 46, 1–12.

Hair, E. C., Park, M. J., Ling, T. J., and Moore, K. A. (2009). Risky behaviors in late adolescence: co-occurrence, predictors, and consequences. Journal of Adolescent Health 45, 253–261.

Hatmaker, D. M. (2015). Bringing networks in: a model of organizational socialization in the public sector. Public Manag. Rev. 17, 1146–1164. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2014.895029

Huang, M. H., and Cheng, Z. H. (2011). The effects of inter-role conflicts on turnover intention among frontline service providers: does gender matter? The Service Industries Journal 32, 367–381. doi: 10.1080/02642069.2010.545391

Huyghebaert, T., Gillet, N., Fernet, C., Lahiani, F. J., and Fouquereau, E. (2018). Leveraging psychosocial safety climate to prevent ill-being: the mediating role of psychological need thwarting. J. Vocat. Behav. 107, 111–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2018.03.010

Judge, T. A., Zhang, S. C., and Glerum, D. R. (2020). Job satisfaction. Essentials of job attitudes and other workplace psychological constructs, 207–241.

Jolly, P. M., McDowell, C., Dawson, M., and Abbott, J. (2021). Pay and benefit satisfaction, perceived organizational support, and turnover intentions: the moderating role of job variety. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 95:102921. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102921

Karatepe, O. M., and Olugbade, O. A. (2017). The effects of work social support and career adaptability on career satisfaction and turnover intentions. J. Manag. Organ. 23, 337–355. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2016.12

Kmieciak, R. (2022). Co-worker support, voluntary turnover intention and knowledge withholding among IT specialists: the mediating role of affective organizational commitment. Balt. J. Manag. 17, 375–391. doi: 10.1108/BJM-03-2021-0085

Koseoglu, G., Blum, T. C., and Shalley, C. E. (2020). Gender similarity, coworker support, and job attitudes: an occupation’s creative requirement can make a difference. J. Manag. Organ. 26, 880–898. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2018.40

Kowtha, N. R. (2013). Not separate but unequal: gender and organizational socialization of newcomers. Asian Women 29, 47–77.

Le, H., Lee, J., Nielsen, I., and Nguyen, T. L. A. (2023). Turnover intentions: the roles of job satisfaction and family support. Pers. Rev. 52, 2209–2228. doi: 10.1108/PR-08-2021-0582

Li, R., and Yao, M. (2022). What promotes teachers’ turnover intention? Evidence from a meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 37:100477. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100477

Macias-Velasquez, S., Baez-Lopez, Y., Tlapa, D., Limon-Romero, J., Maldonado-Macías, A. A., Flores, D. L., et al. (2021). Impact of co-worker support and supervisor support among the middle and senior management in the manufacturing industry. IEEE Access 9, 78203–78214. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3082177

Matijaš, M., Merkaš, M., and Brdovčak, B. (2018). Job resources and satisfaction across gender: the role of work–family conflict. J. Manag. Psychol. 33, 372–385. doi: 10.1108/JMP-09-2017-0306

McCartney, G., Chi In, C. L., and Pinto, J. S. D. A. F. (2022). COVID-19 impact on hospitality retail employee turnover intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 34, 2092–2112. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-08-2021-1053

Moreland, R. L., and Levine, J. M. (2014). “Socialization in organizations and work groups” in Groups at Work (New York: Psychology Press), 69–112.

Mumu, J. R., Tahmid, T., and Azad, M. A. K. (2021). Job satisfaction and intention to quit: a bibliometric review of work-family conflict and research agenda. Appl. Nurs. Res. 59:151334. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2020.151334

Namasivayam, K., and Mount, D. J. (2004). The relationship of work-family conflicts and family-work conflict to job satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 28, 242–250. doi: 10.1177/1096348004264084

Nazir, S., Shafi, A., Qun, W., Nazir, N., and Tran, Q. D. (2016). Influence of organizational rewards on organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Empl. Relat. 38, 596–619. doi: 10.1108/ER-12-2014-0150

Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. S., and McMurrian, R. (1996). Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 81, 400–410. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400

Nguyen, N. T. H., and Tuan, L. T. (2022). Creating reasonable workload to enhance public employee job satisfaction: the role of supervisor support, co-worker support, and tangible job resources. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 45, 131–162. doi: 10.1080/15309576.2021.2018717

Norling, L. R., and Chopik, W. J. (2020). The association between coworker support and work-family interference: a test of work environment and burnout as mediators. Front. Psychol. 11:819. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00819

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). An overview of psychological measurement. Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders: A Handbook, 97–146.

Patterer, A. S., Kühnel, J., and Korunka, C. (2024). Parallel effects of the need for relatedness: a three-wave panel study on how coworker social support contributes to OCB and depersonalization. Work Stress 38, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2023.2222367

Pitts, D., Marvel, J., and Fernandez, S. (2011). So hard to say goodbye? Turnover intention among US federal employees. Public Adm. Rev. 71, 751–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02414.x

Porter, L. W., and Steers, R. M. (1973). Organizational, work, and personal factors in employee turnover and absenteeism. Psychol. Bull. 80:151. doi: 10.1037/h0034829

Pu, B., Sang, W., Ji, S., Hu, J., and Phau, I. (2024). The effect of customer incivility on employees' turnover intention in hospitality industry: a chain mediating effect of emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 118:103665. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2023.103665

Saks, A. M., and Gruman, J. A. (2011). Organizational socialization and positive organizational behavior: implications for theory, research, and practice. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 28, 14–26. doi: 10.1002/cjas.169

Saks, A., and Gruman, J. A. (2014). Making organizations more effective through organizational socialization. J. Organ. Eff. 1, 261–280. doi: 10.1108/JOEPP-07-2014-0036

Sharif, S. P., Bolt, E. E. T., Ahadzadeh, A. S., Turner, J. J., and Nia, H. S. (2021). Organizational support and turnover intentions: a moderated mediation approach. Nurs. Open 8, 3606–3615. doi: 10.1002/nop2.911

Shi, S., Chen, Y., and Cheung, C. M. (2023). How techno stressors influence job and family satisfaction: exploring the role of work–family conflict. Inf. Syst. J. 33, 953–985. doi: 10.1111/isj.12431

Singh, B., Selvarajan, T. T., and Solansky, S. T. (2019). Coworker influence on employee performance: a conservation of resources perspective. J. Manag. Psychol. 34, 587–600. doi: 10.1108/JMP-09-2018-0392

Singh, J., Verbeke, W., and Rhoads, G. K. (1996). Do organizational practices matter in role stress processes? A study of direct and moderating effects for marketing-oriented boundary spanners. J. Mark. 60, 69–86. doi: 10.1177/002224299606000305

Sloan, M. M. (2012). Unfair treatment in the workplace and worker well-being: the role of coworker support in a service work environment. Work. Occup. 39, 3–34. doi: 10.1177/0730888411406555

Sloan, M. M., Evenson Newhouse, R. J., and Thompson, A. B. (2013). Counting on coworkers: race, social support, and emotional experiences on the job. Soc. Psychol. Q. 76, 343–372. doi: 10.1177/0190272513504937

Son, G. R., Zauszniewski, J. A., Wykle, M. L., and Picot, S. J. F. (2000). Translation and validation of caregiving satisfaction scale into Korean. Western Journal of Nursing Research 22, 609–622.

Spector, P. E., Allen, T. D., Poelmans, S. A., Lapierre, L. M., Cooper, C. L., Michael, O. D., et al. (2007). Cross-national differences in relationships of work demands, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions with work–family conflict. Personnel Psychology 60, 805–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00092.x

Stacey, S. R. (2018). Where the Difference Begins: A Phenomenological Inquiry into the Lived Organizational Socialization Experiences of United States Marine Corps Veterans to Describe the Perceived Transformational Effects of Recruit Training. Ph.D. dissertation: Johnson University.

Sundari, P., Cahyono, B., Lusianti, D., and Nurhayati, E. C. (2024). Post-development employee retention: a literature review based on social exchange dynamics in the work environment. Achieving Sustainable Business through AI, Technology Education and Computer Science : Volume 1: Computer Science, Business Sustainability, and Competitive Advantage, 251–260. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-70855-8_22

Taormina, R. J. (1994). The organizational socialization inventory. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2, 133–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2389.1994.tb00134.x

Tett, R. P., and Meyer, J. P. (1993). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Pers. Psychol. 46, 259–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1993.tb00874.x

Tews, M. J., Michel, J. W., and Ellingson, J. E. (2013). The impact of coworker support on employee turnover in the hospitality industry. Group Org. Manag. 38, 630–653. doi: 10.1177/1059601113503039

Torlak, N. G., Budur, T., and Khan, N. U. S. (2024). Links connecting organizational socialization, affective commitment and innovative work behavior. Learn. Organ. 31, 227–249. doi: 10.1108/TLO-04-2023-0053

Tsai, Y., and Wu, S. W. (2010). The relationships between organizational citizenship behavior, job satisfaction, and turnover intention. J. Clin. Nurs. 19, 3564–3574. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03375.x

Tschopp, C., Grote, G., and Gerber, M. (2014). How career orientation shapes the job satisfaction–turnover intention link. J. Organ. Behav. 35, 151–171. doi: 10.1002/job.1857

Yildiz, B., Yildiz, H., and Ayaz Arda, O. (2021). Relationship between work–family conflict and turnover intention in nurses: a meta-analytic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 77, 3317–3330. doi: 10.1111/jan.14846

Yucel, D., and Minnotte, K. L. (2017). Workplace support and life satisfaction: the mediating roles of work-to-family conflict and mental health. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 12, 549–575. doi: 10.1007/s11482-016-9476-5

Zhang, Q., Li, X., and Gamble, J. H. (2022). Teacher burnout and turnover intention in higher education: the mediating role of job satisfaction and the moderating role of proactive personality. Front. Psychol. 13:1076277. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1076277

Zhang, H., Tang, L., Ye, Z., Zou, P., Shao, J., Wu, M., et al. (2020). The role of social support and emotional exhaustion in the association between work-family conflict and anxiety symptoms among female medical staff: a moderated mediation model. BMC Psychiatry 20, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02673-2

Zhou, J., GAO, B. W., He, W., and He, G. (2022). Do young employees satisfy their job under work stress and work-family conflict? Evidence from resorts in Macau. Int. J. Sci. Soc. 4, 557–576. doi: 10.54783/ijsoc.v4i4.605

Keywords: coworker support, work–family conflict, job satisfaction, turnover intention, female employee, resorts

Citation: Bai Y and Zhou J (2025) Coworker support, work–family conflict, job satisfaction, and turnover intention: female employees in post-organizational socialization. Front. Psychol. 16:1472977. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1472977

Edited by:

Wuke Zhang, Ningbo University, ChinaReviewed by:

Nasr Chalghaf, University of Gafsa, TunisiaDragan Mijakoski, Institute of Occupational Health of RNM, North Macedonia

Copyright © 2025 Bai and Zhou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jinquan Zhou, anF6aG91QG1wdS5lZHUubW8=

Yang Bai1

Yang Bai1 Jinquan Zhou

Jinquan Zhou