- 1School of Business, Guangxi University, Nanning, China

- 2Renmin Business School, Renmin University of China, Beijing, China

While research on supervisor gossip has sought to provide a balanced examination of its potential benefits and drawbacks for employees, there remains a significant disparity in the attention given to positive versus negative gossip. By integrating social comparison theory and goal orientation theory, we propose that the impact of supervisor positive gossip on employee receivers’ self-efficacy and job performance is contingent upon the level of employees’ performance goal orientation (PGO). We argue that high-PGO employees are expected to experience lower levels of self-efficacy upon receiving supervisor positive gossip, whereas low-PGO employees are anticipated to experience higher self-efficacy. Additionally, we suggest that employees’ self-efficacy mediates the relationship between supervisor positive gossip and job performance. Dyadic data collected from 161 supervisors and 556 employees in a Chinese company support our hypotheses. Our findings contribute to a more nuanced discourse on the role of supervisor positive gossip in organizational dynamics and its implications for employee well-being and productivity.

1 Introduction

Supervisors often participate in downward gossip, which is defined as the supervisor’s informal and evaluative talk to an employee (i.e., the gossip receiver) about another employee who is not present (i.e., the gossip target) (Brady et al., 2017; Kuo et al., 2018; Bai et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2023). Such type of gossip is considered more credible and influential than that initiated by employees, as it typically includes compelling narratives about job performance that are not readily available from any other sources (Kuo et al., 2018; Bai et al., 2020). Extant research has primarily focused on exploring the consequences of supervisor gossip on receivers, suggesting that supervisor negative gossip can undermine the leader-member exchange relationship (Kuo et al., 2018), while promoting receivers’ vicarious learning of norms and enhancing receiver performance (Bai et al., 2020).

However, research on the consequences of supervisor gossip suffers from two limitations. First, extant research has differentiated between the positive and negative gossip based on the valence of evaluations being made (Kurland and Pelled, 2000; Ellwardt et al., 2012), but with a general assumption that gossip tends to contain more negative connotations than positive ones (Kong, 2018; Wu L. Z. et al., 2018; Wu X. et al., 2018). This assumption may be biased, as evidence indicates that positive gossip and negative gossip are equally distributed within organizations (Spoelma and Hetrick, 2021). Supervisors might strategically use both types of gossip to reinforce norms and regulate deviant behaviors (Dores Cruz et al., 2021b; Zhu et al., 2022). Second, while the effects of negative gossip on work behavior can be either beneficial or detrimental (Kuo et al., 2018; Bai et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2022, 2023), research on positive gossip has been notably limited to its favorable outcomes, such as its value for receivers’ self-improvement (Martinescu et al., 2014). Such view is generally predicated on the assumption of a homogenous receiver group, overlooking the fact that receivers possess diverse dispositional characteristics and may interpret positive gossip differently.

To address this concern, we pose the question: Does supervisor positive gossip consistently yield favorable outcomes for employee receivers? Alternatively, could it potentially lead to unintended negative consequences for some employee receivers? Based on goal orientation theory (Dweck, 1986), we propose that the impact of supervisor positive gossip on receivers is dependent on the level of gossip receivers’ performance goal orientation (PGO). PGO describes an individual’s desire to affirm and establish their competence through outperforming their peers (Dweck, 1986; Elliot and Church, 1997). This orientation significantly influences how individuals interpret and respond to evaluative information within high-achievement contexts, such as the workplace (Lee et al., 2003; Poortvliet and Darnon, 2010; Downes et al., 2021).

In line with the social comparison perspective on gossip, gossip is seen as a conduit for conveying credible evaluative information that allows employee receivers to engage in social comparisons with the gossip targets (Wert and Salovey, 2004; Martinescu et al., 2014). Notably, when employees receive positive gossip from supervisors about their peers, they are likely to perceive these peers as superior performers and engage in upward social comparisons (Suls, 1977). These comparisons serve as a mirror for receivers to assess their own competence, which subsequently influences their performance (Blanton et al., 1999; Downes et al., 2021). We use the concept of self-efficacy to represent the outcomes of these self-assessments by employees. Self-efficacy pertains to an individual’s judgments of their capabilities to mobilize and apply skills necessary to accomplish specific performance objectives (Bandura, 1986).

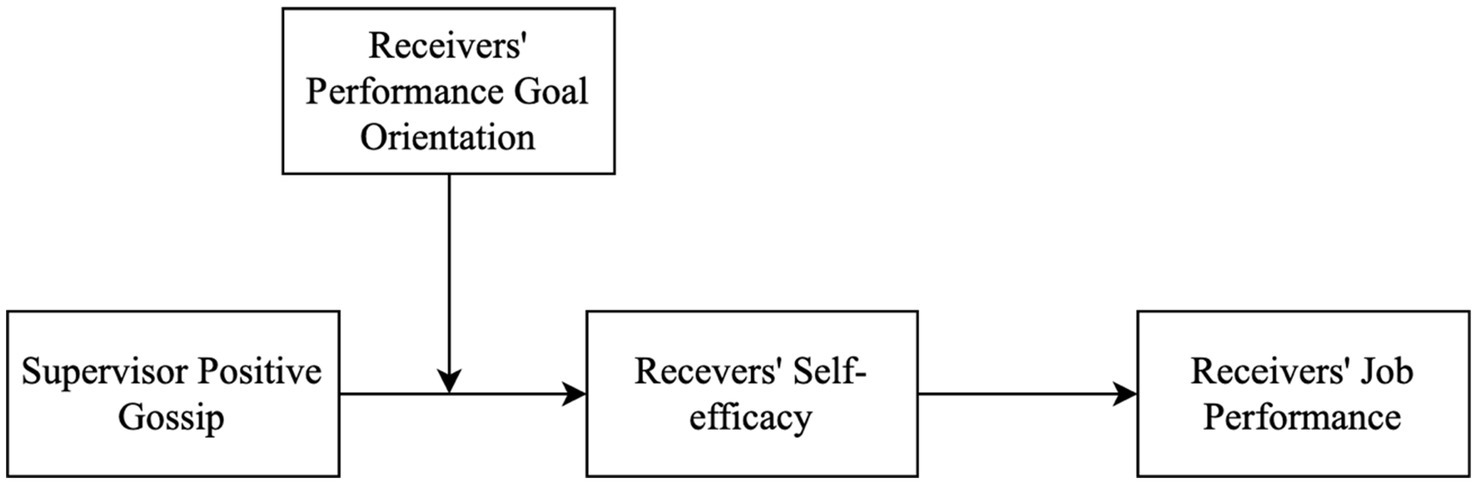

Based on goal orientation theory (Dweck, 1986), we contend that individuals with high PGO are more inclined to contrast themselves against gossip targets. Upon such comparisons, these high-PGO individuals might view themselves as less effective than the gossip targets, particularly when they are on the receiving end of supervisor positive gossip (Buunk and Gibbons, 2007). This realization can undermine their self-efficacy and job performance. In contrast, we expect that low-PGO receivers will exhibit an assimilation pattern. They are likely to view the targets of supervisor positive gossip as exemplary models to emulate, which in turn boosts their self-efficacy and drives them to pursue higher performance (Downes et al., 2021). The overall theoretical framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

Our research contributes to research on supervisor gossip, social comparison and goal orientation literature. First, by examining the contingent effects of supervisor positive gossip on employee receivers’ self-efficacy and job performance, our research provides a more nuanced understanding of when supervisor positive gossip may have unintended negative effects. While prior studies have highlighted gossip’s motivational or informative functions (Kuo et al., 2018; Bai et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2023), we show that high-PGO employees may suffer reduced self-efficacy due to contrastive social comparisons. Second, our work offers cross-disciplinary insights by linking PGO from goal orientation theory to the social comparison function of gossip. Specifically, we argue that PGO functions as a proxy for individuals’ perceived attainability in upward comparisons, which determines whether gossip leads to assimilation or contrast effects (Lockwood and Kunda, 1997; Mussweiler et al., 2004). This perspective advances ongoing debates in social comparison research and highlights the psychological mechanisms that drive differential reactions to the same comparative information. Third, our study deepens the integration of social comparison theory into workplace gossip studies. By revealing the facilitative role of supervisor gossip in prompting receivers’ social comparisons, we reinforce the notion that “social comparison is deeply embedded in the fabric of organizational life” (Greenberg et al., 2007, p. 23). Supervisor gossip is not merely informal talk but a powerful social signal that employees interpret through the lens of their performance goal orientation, shaping their perceived self-worth and job performance.

2 Theory and hypotheses

2.1 Supervisor job-related gossip

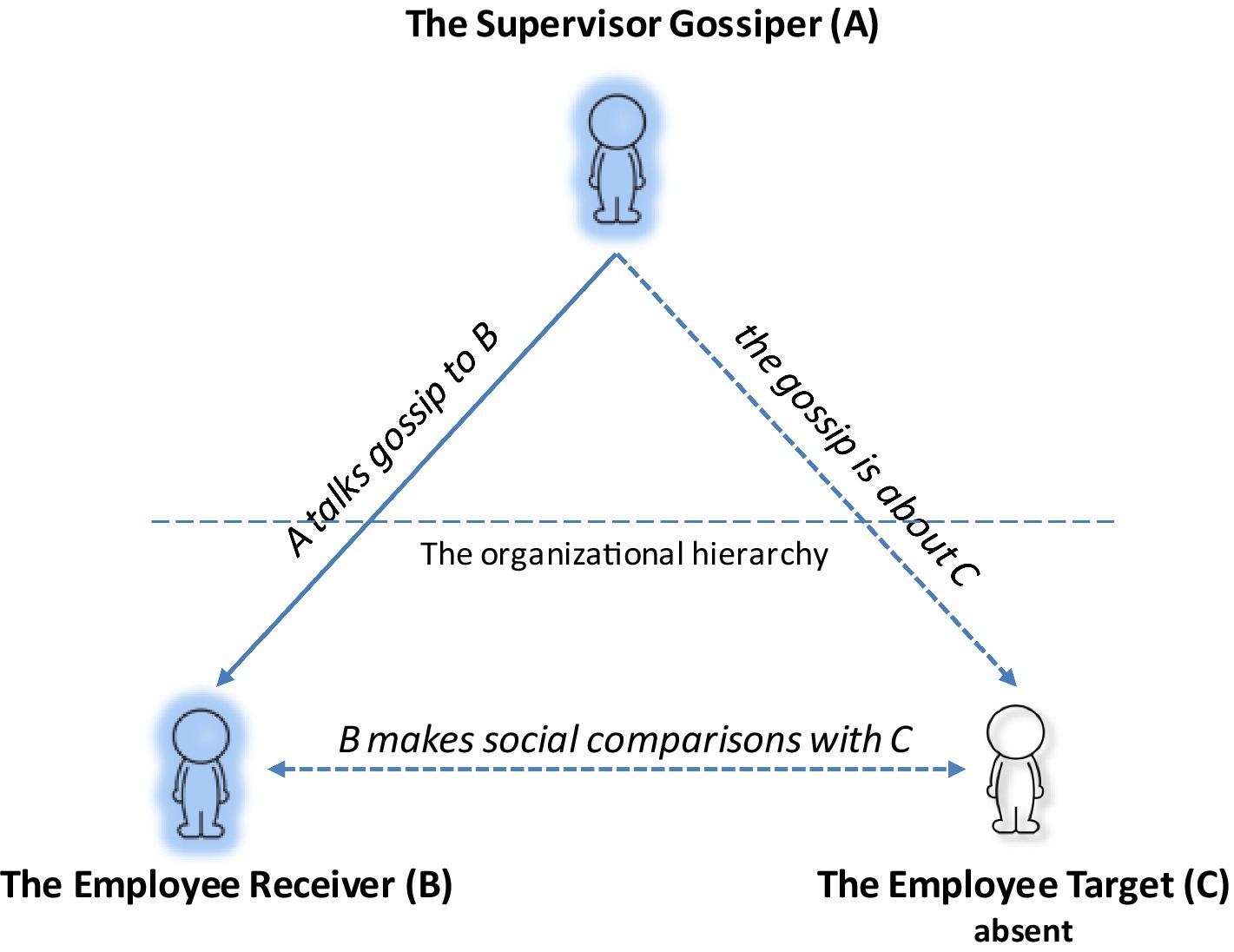

Recent advances in organization research acknowledge gossip as an intrinsic workplace activity that can hardly be eliminated but can be effectively managed (Grosser et al., 2012). Echoing the re-conceptualization of workplace gossip by Brady et al. (2017), we define supervisor gossip as informal and evaluative discourse from a supervisor to an employee about another employee who is not present. A typical instance of supervisor gossip involves a triad structure comprising a gossiper, a gossip receiver and a gossip target (Brady et al., 2017; Dores Cruz et al., 2021a). The gossip triad involved in supervisor gossip is illustrated in Figure 2. Compared to formal communication channels such as formal meetings and written documents, informal channels like gossip allow supervisors to convey messages and expectations more efficiently (Su et al., 2009; Bai et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2023).

In the current study, we have chosen to focus specifically on job-related gossip, which pertains to discussions about employees’ work behaviors, including their job performance, diligence, credibility, work skills, and job morality (Kuo et al., 2015). This type of gossip is particularly relevant to receivers in high-achievement contexts like the workplace (Martinescu et al., 2014; Kuo et al., 2015). Our research concentrates on what we define as supervisor job-related positive gossip, which involves a supervisor sharing positive evaluations about an absent employee’s work behavior with another employee, such as compliments on the absent employee’s excellent job performance or their diligence (Ellwardt et al., 2012).

2.2 Supervisor positive gossip and employee receivers’ self-efficacy

Social comparison theory posits that individuals have a fundamental need to evaluate their own abilities. When clear benchmarks are lacking, individuals tend to compare themselves with peers as a means to gauge the relative standing of their abilities (Festinger, 1954). In the workplace, while some tasks have clear performance metrics, the true value of many work contributions often remains ambiguous. Consequently, given performance levels take on richer meaning through social comparisons (Downes et al., 2021). As a result, employees are continually in search of evaluative information about their peers to evaluate their own capabilities (Sedikides and Skowronski, 2000; Sedikides and Gregg, 2008; Martinescu et al., 2014). Research has shown that workplace gossip fulfills this social comparison need by providing evaluative information about coworkers in a manner that feels less confrontational than direct inquiries (Suls, 1977; Wert and Salovey, 2004).

Supervisor positive gossip, which narrates tales of how other employees successfully accomplished job tasks, can trigger receivers’ upward comparisons with the gossip targets, who are perceived as higher performers (Collins, 1996; Lockwood and Kunda, 1997). Studies suggest that the social comparisons triggered by supervisor gossip underscore the perceived performance discrepancies between receivers and targets (Hogg, 2000; Bai et al., 2020), impacting receivers’ self-concepts such as self-esteem, self-worth, self-efficacy (Lockwood et al., 2002; e.g., Buunk and Gibbons, 2007; Martinescu et al., 2014). When the focus of self-concept construct is job- or task-specific, it becomes closely intertwined with self-efficacy (Gist and Mitchell, 1992; Downes et al., 2021). Self-efficacy, which refers to an individual’s assessment of their capabilities to mobilize skills and execute actions to achieve specific performance goals (Bandura, 1986), is particularly pertinent in the workplace context where employees constantly adjust self-evaluations based on social comparisons with their coworkers.

Social comparison theory further suggests that individuals may exhibit two distinct responses to social comparisons, namely assimilation and contrast (Suls et al., 2002; Mussweiler et al., 2004; e.g., Gerber et al., 2018). Assimilation occurs when receivers’ self-efficacy aligns with that of the gossip targets, adopting a more positive stance upon receiving supervisor positive gossip (i.e., believing that one could emulate the target’s improvements). On the other hand, contrast arises when receivers’ self-efficacy diverges from that of the gossip targets, leading to more negative perceptions after being exposed to supervisor positive gossip (i.e., feeling inferior to the target) (Gerber et al., 2018; Matta and Van Dyne, 2020). These divergent reactions demonstrate that the effects of supervisor positive gossip on receivers’ self-efficacy can swing between positive and negative outcomes (Mussweiler et al., 2004). Therefore, we first propose a baseline hypothesis regarding the relationship between supervisor positive gossip and receivers’ self-efficacy. We will delve into the positive and negative nuances of this relationship in subsequent hypotheses, exploring the conditions under which each type of response is more likely to occur.

Baseline Hypothesis: Supervisor positive gossip is related to employee receivers’ self-efficacy, and this relationship can be either positive or negative.

2.3 The moderation of receivers’ PGO on the relationship between supervisor positive gossip and self-efficacy

Researchers have identified various factors that act as the “toggle switch” which influences whether social comparisons lead to assimilation or contrast effects. For example, when comparers feel psychologically close to the comparison targets (e.g., Lockwood and Kunda, 1997; Tesser, 1988) or share similar characteristics with the targets (e.g., Brown et al., 1992), they are more inclined to assimilate their self-evaluations towards the targets. The contrast effects occur under opposing conditions. Essentially, these moderators hinge on the comparers’ perceived attainability – the belief of whether they could realistically achieve similar outcomes as the targets in the future (Mussweiler et al., 2004).

In high-achievement contexts like the workplace, employees’ perceptions of their abilities significantly shape their expectations for their future performance (Payne et al., 2007). Those who view their competence as a fixed attribute may doubt their capacity for improvement through effort and tend to adopt performance goals as a result (Dweck, 1986). These individuals define competence in terms of outperforming others and are especially attuned to interpersonal comparisons (VandeWalle et al., 1999; Elliot, 2005). When exposed to upward comparisons, such as hearing praise about high-performing coworkers, they may experience threat, frustration, or inferiority (Elliot, 2005; VandeWalle et al., 1999). Accordingly, we propose that receivers’ PGO is a critical moderator that shapes whether supervisor positive gossip enhances or undermines receivers’ self-efficacy. We argue that PGO shapes how employee receivers interpret the supervisor positive gossip, either as an opportunity or threat, by influencing their perception of attainability. Although our study does not directly measure perceived attainability, we conceptualized PGO as a proxy for this belief: individuals high in PGO are more likely to interpret coworkers’ superior performance as unattainable, while those low in PGO are more likely to believe such outcomes are within reach.

Specifically, individuals with high PGO often engage in contrast comparisons, viewing others as competitors and themselves as adversaries (Dweck, 1986; Elliot and Church, 1997). For these individuals, positive gossip from supervisors about other employees can lead to the perception that others are outperforming them, triggering feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt (Buunk and Gibbons, 2007), particularly when they perceive the positively gossiped targets’ performance as unattainable. This perception reduces their self-efficacy, the belief that they are capable of achieving similar success, even if their motivation to perform remains high. Previous studies have indicated that receivers with high PGO, when making upward comparisons, frequently experience negative emotions such as self-directed frustration, resentment and envy towards high performers (Lockwood and Kunda, 1997; Smith, 2000), and they may fail to benefit from vicarious learning opportunities (Downes et al., 2021). Therefore, we expect that for high-PGO receivers, supervisor positive gossip may inadvertently undermine their confidence in bridging the perceived performance gap (i.e., self-efficacy) (Collins, 1996; Cohen-Charash and Mueller, 2007).

In contrast, employees with low PGO do not define their self-worth through outperforming others and are less likely to perceive coworker success as threatening. While they may not be high in learning goal orientation, their lower concern with perceived performance gap enables them to see supervisor positive gossip as useful insights rather than competition (Weber and Hertel, 2007; Downes et al., 2021). By learning from the behaviors and strategies contained in supervisor positive gossip, they can experience various mastery (Bandura, 1977), which enhances their belief in their own ability to achieve similar outcomes. These employees are more likely to interpret high performers as role models and view their success as attainable, thereby increasing their self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977; Lockwood and Kunda, 2000). This perspective aligns with Lockwood and Kunda’s (1997) finding that individuals can be inspired by high-performing “superstars” when they believe success is within their reach.

In sum, we argue that PGO determines whether supervisor positive gossip is interpreted through the lens of threat or inspiration, and thereby whether it decreases or increases self-efficacy. The rationale leads to our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Receivers’ PGO moderates the relationship between supervisor positive gossip and receivers’ self-efficacy such that the relationship is negative for high-PGO receivers and positive for low-PGO receivers.

2.4 The mediation of self-efficacy between supervisor positive gossip and job performance

We further anticipate that receivers’ self-efficacy serves as a mediator in the relationship between supervisor positive gossip and receivers’ job performance. Self-efficacy, which signifies an individual’s assessment of their capabilities to execute courses of action necessary for dealing with prospective situations (Bandura, 1982), fosters both the ambition to pursue higher goals and the persistence to overcome challenges and obstacles (Bandura, 1997). Meta-analyses have confirmed a robust positive link between self-efficacy and work-related performance (Stajkovic and Luthans, 1998).

Individuals with high self-efficacy are more inclined to set lofty performance goals and exhibit a stronger commitment to achieving them, leading to superior performance levels (Downes et al., 2021). In contrast, those with lower self-efficacy often harbor modest aspirations and lower performance expectations, potentially abandoning their efforts early and failing to accomplish their tasks (Bandura, 1977, 1986). Taken together, the assertion that receivers’ self-efficacy is positively related to job performance can be integrated with the notion that supervisor positive gossip influences self-efficacy. This leads to the proposal that self-efficacy acts as a mediator in the relationship between supervisor positive gossip and job performance. We thus propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Receivers’ self-efficacy mediates the relationship between supervisor positive gossip and receivers’ job performance.

2.5 An integrative moderated mediation model

Thus far, we have developed a theoretical framework for the first-stage moderation effect of receivers’ PGO (Baseline Hypothesis and Hypothesis 1), and the mediation of receivers’ self-efficacy between supervisor positive gossip and receivers’ job performance (Hypothesis 2). The theoretical rationales behind these hypotheses altogether suggest an integrative first-stage moderated mediation model, which indicates receivers’ PGO moderates the indirect effect of supervisor positive gossip on receivers’ performance via receivers’ self-efficacy. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3: Receiver’s PGO moderates the indirect effect of supervisor positive gossip on receivers’ job performance via self-efficacy, such that the indirect effect is negative for high-PGO receivers, and positive for low-PGO receivers.

3 Method

3.1 Research context

Our multi-wave and multi-source data were collected from a nation-wide retailer company in China, which operates over 500 branch stores across central mainland China. The company is dedicated to supplying fresh dairy products to local customers. We communicated the purpose and significance of our research with the management team, and gained their support to conduct the questionnaire survey across its branch stores. For each branch store, there are one manager (i.e., the supervisor) and several salespeople (i.e., the employees). During the workday, the employees are assigned with different tasks and have separate working areas. For example, the employee responsible for check-out service works behind the counter, while the employee that serves customers normally works near the store entrance. The manager, meanwhile, walks around the store inspecting their work. Moreover, the employees take turns to have their mealtime. In other words, the setting of separate work areas and staggered mealtime makes it possible for the managers to talk gossip to an employee about an absent employee. Besides, the managers and employees are all highly aware of the significance of their work to the store’s overall business performance because their salary is closely linked to the store’s sales revenue. Therefore, we deem this company an optimal setting for studying supervisor positive gossip and its implications for employee job performance, given the prevalent opportunities for such interactions and the high value placed on job performance.

3.2 Participants and procedures

We conducted a three-wave data collection with the intention to reduce the likelihood of common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). We explained to all participants (both supervisors and their employees) that the purpose of this study was to examine the effectiveness of current human resource practices and to seek out the possible directions for improvements. Separate questionnaires were administered to employees and supervisors. Participants were informed of the details of the study, the voluntary nature of participation and the assurance of anonymity before they filled out the questionnaire. Each employee was assigned a personal code to fill out the questionnaire so we can match their responses with their supervisors’. We collected data with a one-month interval. In Phase 1 (P1), we asked employees to provide their demographic information, and rate their perceptions of the supervisor gossip they received in the past month, and their PGO. In Phase 2 (P2), which was conducted one month after P1, the employees reported their perceived self-efficacy in the past month. In Phase 3 (P3), which was conducted one month after P2, the employees’ direct supervisors were asked to evaluate employees’ job performance in the past month.

We received a list of 719 randomly selected employees and their direct supervisors. 676 of them submitted their questionnaires in P1. In P2, we received 658 usable employee questionnaires. Finally, in P3, questionnaires were distributed to the employees’ direct supervisors. After matching, we obtained a final sample of 556 complete supervisor-employee dyads with a response rate of 77.33%, which constituted the basis for our analysis. Taken together, the final sample used for this study consisted of 161 supervisors and their 556 employees. Of the 556 employees, 73.38% are female. Their average age is 32.5, and the average tenure is 3.79 years. The average time spent under their supervisor’s supervision is 2.10 years, and 39.03% of employees’ education level is junior college and above. Of the 161 supervisors, 66.46% are male. The average age is 31.44, and the average tenure is 3.86 years. 62.11% of supervisors’ education level is junior college and above.

3.3 Measures

As the survey was conducted in China, we used Chinese as our survey language. Nonetheless, all measures in this study were originally developed in English. To ensure the equivalency of meaning and minimize the misunderstanding, we followed the commonly-used back-translation procedures (Brislin, 1980). Specifically, the scales were first translated from English into Chinese by a researcher and then were back translated into English by another researcher. Both researchers have years of overseas study experience. Finally, a bilingual researcher compared the English and Chinese versions of these measures and made modifications to resolve the minor discrepancies. This rigorous process helped to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the survey measures in the context of our study.

3.3.1 Supervisor positive gossip

We modified Kuo et al.’ (2015) five-item job-related gossip scale to measure supervisor positive gossip separately. The original scale was designed to evaluate an employee’s positive and negative gossip about his or her coworker, so we reworded the items to reflect the supervisor’s positive gossip about employees for the purpose of our study. A sample item of supervisor positive gossip is “have your supervisor recently talked to you about your coworker’s diligence and dedication to work?” All of the items were evaluated on a 5-point response scale (1 = never, 2 = seldom, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = always). Cronbach’s alpha for supervisor positive gossip scales is 0.95.

3.3.2 Self-efficacy

An eight-item scale developed by Chen et al. (2001) was used to measure receivers’ self-efficacy. The response options ranged from 1, “strongly disagree,” to 5, “strongly agree.” A sample item is “when facing difficult tasks, I am certain that I will accomplish them.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale is 0.92.

3.3.3 Performance goal orientation

An eight-item scale developed by Button et al. (1996) was used to measure PGO. The response options ranged from 1, “strongly disagree,” to 5, “strongly agree.” A sample item is “I feel smart when I can do something better than most other people.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale is 0.95.

3.3.4 Job performance

Given that employees’ contributions to store revenue are highly interdependent and not directly traceable to individual performance for all roles (For instance, some employees are responsible for checkout services or stocking inventory rather than direct sales), we argue that store-level sales cannot reliably capture each employee’s individual performance. Therefore, we used a six-item subscale developed by Tsui et al. (1997) to measure job performance. The response options ranged from 1, “strongly disagree,” to 5, “strongly agree.” Of the original 11 items, six assessed employees’ basic task performance in terms of task quantity, quality, and efficiency. The supervisor rated the extent to which he or she agreed with the items describing the employee’s performance as better than the average level. The sample items include “this employee’s quantity of work is higher than average” and “this employee strives for higher quality work than required.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale is 0.93.

3.3.5 Control variables

As negative gossip has been found to influence individuals’ self-evaluations and work behavior (Martinescu et al., 2014; Kong, 2018; e.g., Bai et al., 2020; Spoelma and Hetrick, 2021), we controlled for supervisor negative gossip using Kuo et al. (2015) 5-item negative gossip scale. A sample item is “have your supervisor recently talked to you about your coworker’s carelessness and poor work engagement?” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale is 0.85.

Since PGO is a paired variable with learning goal orientation (LGO), we also controlled for employees’ LGO using Button et al. (1996)‘s eight-item scale. A sample item is “the opportunity to learn new things is important to me.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale is 0.82. Although there is sparse empirical evidence that women gossip more frequently than men (Foster, 2004; Grosser et al., 2012; Robbins and Karan, 2020), the content or valence of gossip among female and male differs (Levin and Arluke, 1985; Watson, 2012). In order to be consistent with prior gossip studies, we controlled for supervisors’ and employees’ biological sex. We also controlled for their age based on some evidence showing that younger women gossip more about rivals (Massar et al., 2012) and the elders who live alone gossip more about their acquaintances (Torres and Warren-Findlow, 2019). Besides, we controlled for supervisors’ and employees’ working tenure, education level and employees’ working time with the supervisor in consideration of their possible influences on job performance (Ng and Feldman, 2009, 2010).

3.4 Analytical strategy

Although all studied variables were conceptualized and measured at the individual level (Level 1), employees were nested within supervisors, introducing potential non-independence in the data. To assess this, we conducted null models without predictors and calculated the intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC(1)] for the outcome variable, employee job performance. The ICC(1) of employee job performance is 0.20, which exceeds the commonly accepted threshold of 0.10 (LeBreton and Senter, 2008) and indicates medium between-group variances. This justifies the use of multilevel modeling approaches.

Accordingly, we conducted the two-level analysis in Mplus 8 with the TYPE = TWOLEVEL command to account for the between-group variances (Muthén and Muthén, 2017). All focal predictors (e.g., supervisor positive gossip, PGO and self-efficacy) were modeled at the within-group level (%WITHIN%), while group-level control variables (i.e., supervisors’ age, gender, tenure and education) were modeled at the between-group level (%BETWEEN).

We used Monte Carlo integration with 10,000 iterations for indirect effect testing, and the significance of mediation and moderated mediation effects was evaluated using bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (95%). Model fit was assessed using standard fit indices including CFI, TLI, RMSEA and SRMR.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive statistics and confirmatory factor analysis

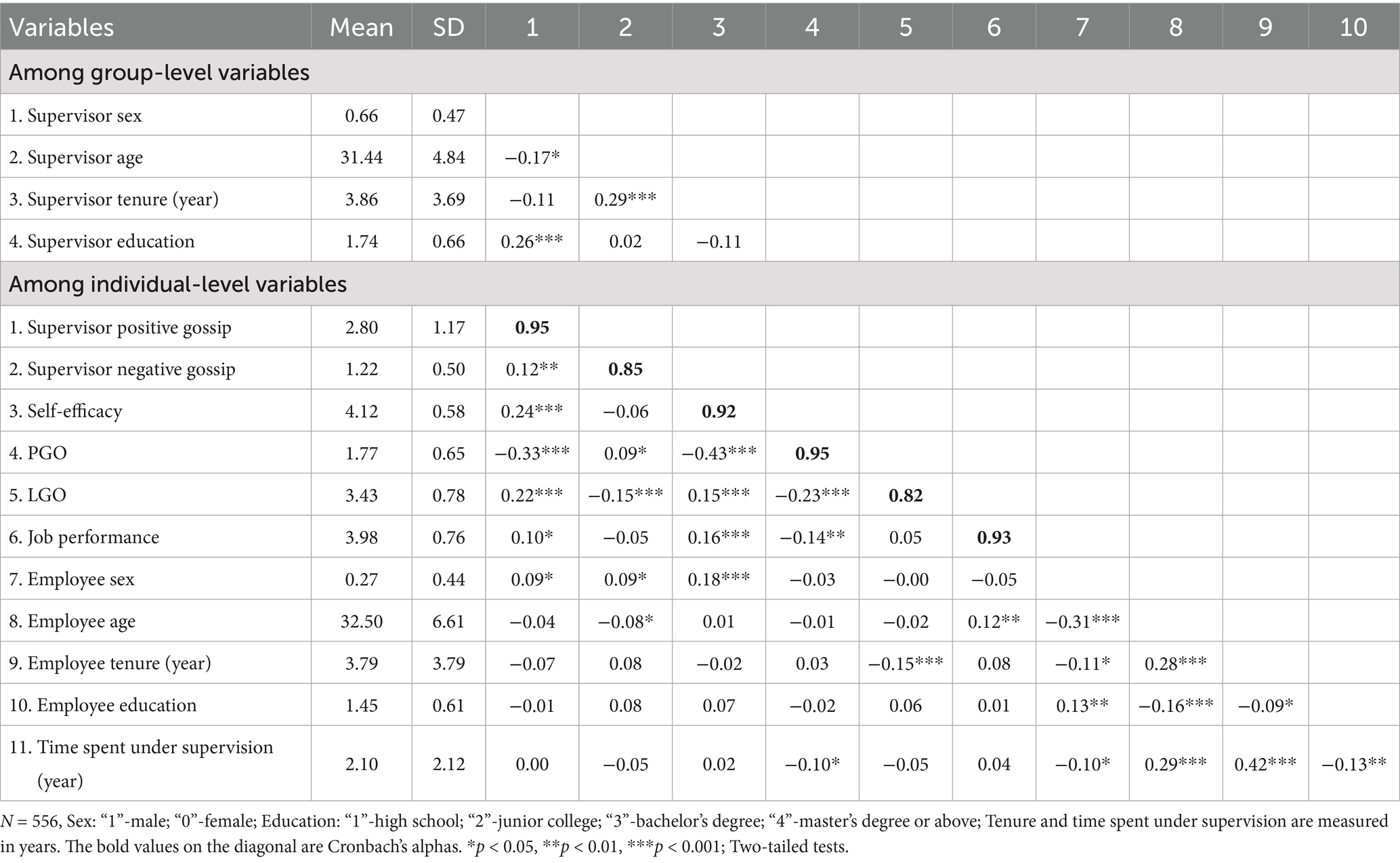

All variables’ means, standard deviations, reliability scores and correlations are reported in Table 1. We find significant correlations between supervisor positive gossip and receivers’ self-efficacy (γ = 0.24, p < 0.001), and between self-efficacy and job performance (γ = 0.16, p < 0.001), and between supervisor positive gossip and job performance (γ = 0.10, p < 0.05). These significant correlations warrant further investigations on their relationships.

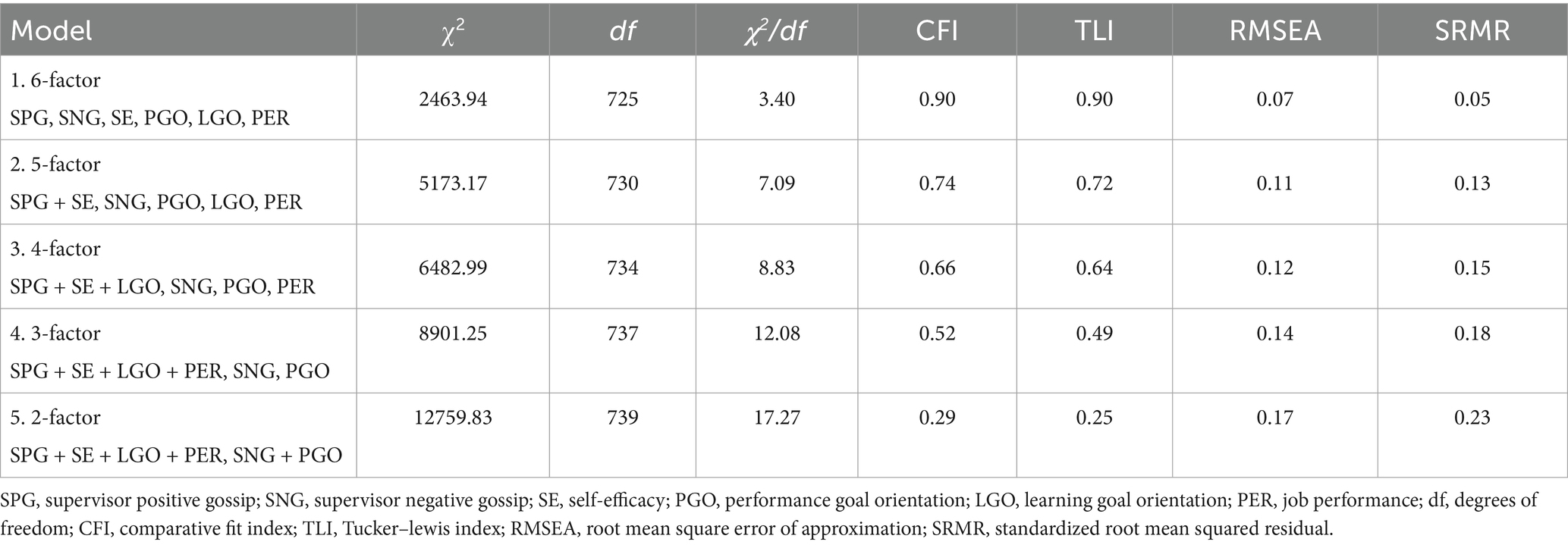

We conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses to evaluate the discriminant validity and goodness of fit of our hypothesized model. The χ2, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) indicators were used to assess the fit of the hypothesized model (Bentler, 1990; Browne and Cudeck, 1993; Kline, 2005). As shown in Table 2, the hypothesized six-factor model yields better fit to the data (χ2/df = 3.40, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.05) than the parsimonious models, and provides satisfactory fit to the data (Browne and Cudeck, 1993).

4.2 Hypotheses testing

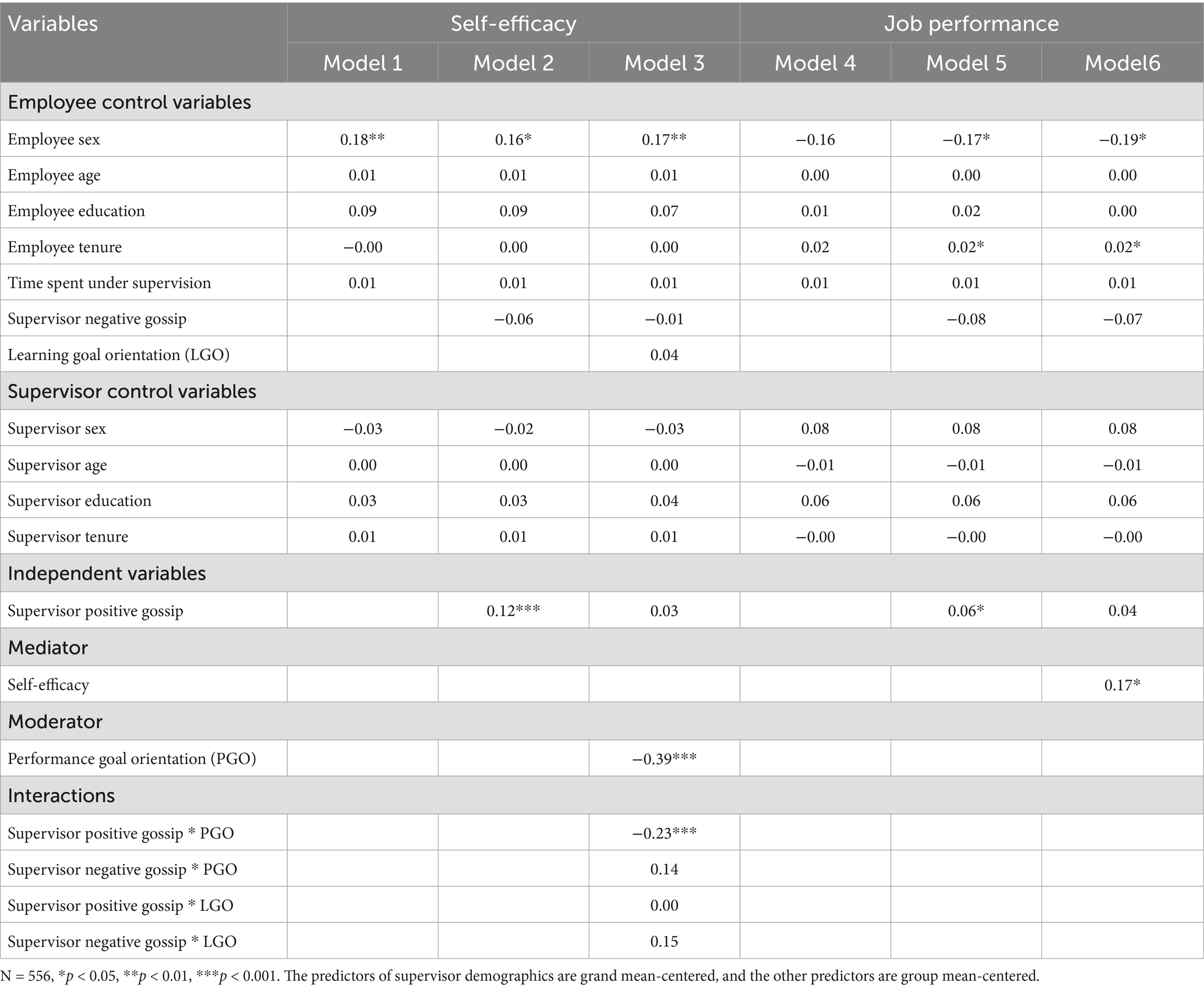

We tested our hypotheses using two-level analysis in Mplus 8. The predictors of supervisor demographics are grand mean-centered at the group level, and the other predictors are group mean-centered (Enders and Tofighi, 2007). The baseline hypothesis posits a relationship between supervisor positive gossip and receivers’ self-efficacy. As shown in Model 2 of Table 2, supervisor positive gossip is positively associated with the receiver’s self-efficacy (β = 0.12; p < 0.001), which suggests that in general case, receivers would assimilate rather than contrast to the gossip targets of supervisor positive gossip.

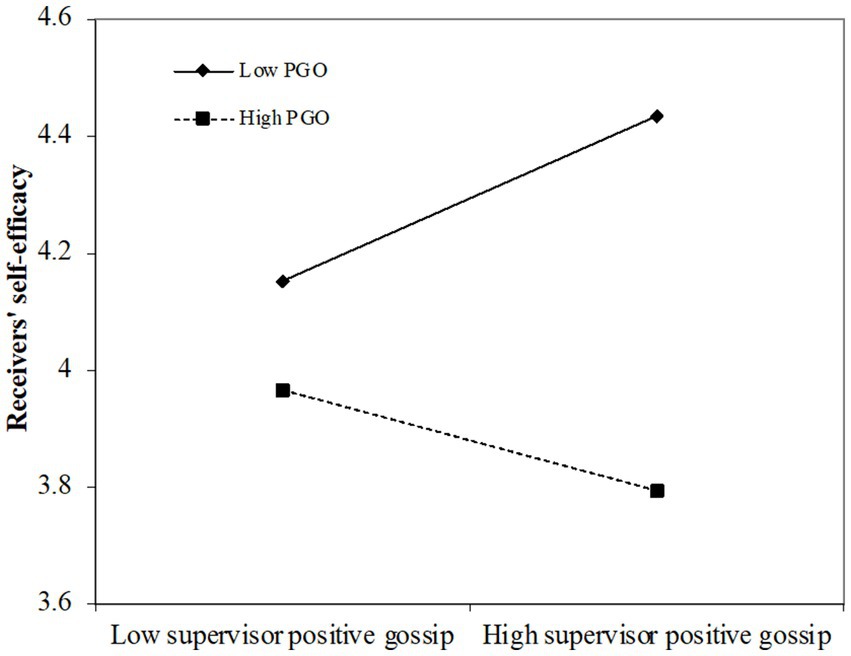

Hypothesis 1 proposes the moderation effect of PGO. To examine this, we first form the interaction item by multiplying the group mean-centered variables of supervisor positive gossip with PGO to minimize multi-collinearity (Aiken and West, 1991). As shown in Model 3 of Table 3, the interaction is significantly related to self-efficacy (β = −0.23; p < 0.001). Therefore, we find preliminary support for Hypothesis 1. To specify the exact “toggle-switch” effect of PGO, we conduct simple slope tests at one standard deviation above and below the mean of PGO (Preacher et al., 2006), and the results demonstrate that the relationship between supervisor positive gossip and self-efficacy is significantly negative when PGO is high (β = −0.09; p < 0.05), and turns significantly positive when PGO is low (β = 0.15; p < 0.05), which confirms Hypothesis 1. We further illustrate the moderation effect in Figure 3 following the procedures proposed by Aiken and West (1991) and Dawson (2014).

Hypothesis 2 states the mediation effect of self-efficacy. The results of two-level analysis indicate that supervisor positive gossip is positively related to self-efficacy (β = 0.12; p < 0.001, Model 2 of Table 3), and self-efficacy is positively related to job performance (β = 0.17; p < 0.05, Model 6 of Table 3). We ran the two-level analysis for the indirect relationship between supervisor positive gossip and job performance via self-efficacy, and results show that the unconditional indirect effect = 0.02 with the 95% CI = [0.003, 0.038], which supports Hypothesis 2.

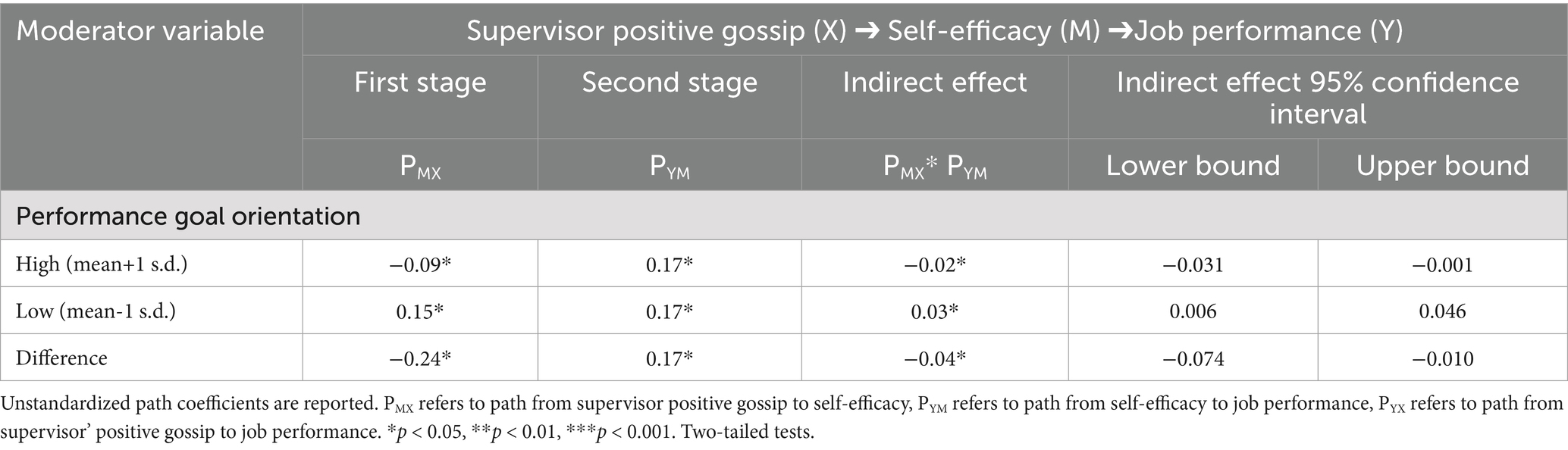

Hypothesis 3 states that PGO moderates the indirect effect of supervisor positive gossip on receiver’s job performance through self-efficacy. To test the first-stage moderated mediation proposed by Hypothesis 3, we applied the moderated path analysis approach of Edwards and Lambert (2007) to estimate the indirect effects at one standard deviation above and below the mean of PGO levels. The results reported in Table 4 indicates that the conditional indirect effect between supervisor positive gossip and job performance via self-efficacy is significantly negative when PGO is high (Indirect effect = −0.02, 95% CI = [−0.031, −0.001]), and becomes significantly positive when PGO is low (Indirect effect = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.006, 0.046]). Moreover, the difference between the two conditional indirect effects is −0.04 with 95% CI = [−0.074, −0.010], which supports Hypothesis 3.

5 Discussion

The empirical examinations have indicated that the supervisor positive gossip’s influences on receivers’ self-efficacy and performance are contingent on receivers’ PGO levels. Specifically, for low-PGO receivers, supervisor positive gossip prompts them to view targets as exemplary figures, inspiring them to pursue comparable accomplishments. This, in turn, leads to an increase in their self-efficacy and performance. Conversely, for those with high PGO, a contrasting reaction occurs, upon hearing supervisor positive gossip, their self-efficacy and job performance are likely to decline. Overall, the level of PGO among receivers is a pivotal factor in determining whether supervisor positive gossip serves as a boon or a bane to their self-efficacy and job performance. This underscores the complexity of how supervisor gossip is perceived and internalized within an organizational context, with significant implications for workplace dynamics and individual motivation.

5.1 Theoretical contributions

Our findings contribute to the extant literature in the following ways. First, we contribute to workplace gossip research by extending the balanced view to positive gossip. While recent organizational research has recognized the dual nature of workplace gossip, highlighting both its benefits and costs for gossipers, receivers and targets (Brady et al., 2017; e.g., Bai et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2023; Zhong et al., 2023), much of this research has focused on negative gossip. Limited research has often assumed that positive gossip uniformly benefits receivers (Martinescu et al., 2014). We demonstrate that even positive gossip from supervisors can yield unintended negative consequences. Specifically, it lowers the self-efficacy of high-PGO employees who may interpret such upward comparisons as threats. Our findings underscore the importance of examining the complex and nuanced outcomes of positive gossip in the workplace.

Second, our research contributes to social comparison literature by strengthening its connections with supervisor gossip studies. Psychological scholars have long posited that gossip serves social comparison functions for all parties involved, providing an indirect and less confrontational means of satisfying individuals’ need for comparative information (Suls, 1977; Wert and Salovey, 2004). However, the integration of workplace gossip research with social comparison theory has been lacking in organizational literature, with most findings focusing on other functions of workplace gossip, such as reflective learning (Bai et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2022), sense-making (Michelson et al., 2010; Mills, 2010), and social bonding (Beersma and Van Kleef, 2012; Dores Cruz et al., 2019). By investigating supervisor positive gossip as a vehicle for social comparison in the workplace, our study uncovers its potential to fulfill receivers’ social comparison needs. Supervisors’ formal authority over employees’ performance evaluations, compensation, and promotions lends credibility to their gossip, making it particularly salient to employees. By conceptualizing PGO as a proxy for perceived attainability, we extend the classic notion that comparison effects hinge on similarity and closeness (e.g., Brown et al., 1992; Lockwood and Kunda, 1997; Tesser, 1988), applying it in a new context of hierarchical gossip. Overall, this integration of social comparison approach with supervisor positive gossip enriches our understanding of workplace gossip functions and extends the applicability of social comparison theory cross disciplines.

Third, we contribute to goal orientation theory by showing that PGO not only predicts whether individuals engage in social comparisons but also shapes how they interpret and respond to the comparison information they receive. While researchers have established connections between goal orientation and social comparison theory, suggesting that individuals’ PGO prompts them to engage in social comparisons (Ames, 1992), few studies have examined how PGO shapes or determines individuals’ responses to these comparisons in high-achievement contexts (see exception: Downes et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2023). Our study theorizes and finds that PGO reverses assimilation to a contrast path for high-PGO receivers. This finding underscores the value of considering PGO as a contingency factor that switches receivers’ reactions to supervisor positive gossip, and confirms the utility of goal orientation theory in clarifying the debate between assimilation and contrast effects in social comparison literature.

5.2 Practical implications

Our research offers several practical implications for supervisors, employees and organizations. First, recognizing that gossip is an inherent aspect of human social interaction, it is impractical for supervisors to eradicate it from the workplace entirely (Grosser et al., 2012; Dores Cruz et al., 2021a). However, its impact can be managed to some extent. Supervisors can strategically mitigate the adverse effects of gossip while leveraging its potential benefits. Our findings indicate that even positive gossip about employees can inadvertently harm individuals with high PGO. Therefore, we advise supervisors to utilize positive gossip judiciously as a motivational tool. Specifically, supervisors might consider engaging in positive gossip with low-PGO employees to inspire them to emulate high performers and set ambitious goals. Conversely, supervisors should be cautious about sharing positive gossip with high-PGO employees, as this may inadvertently diminish their self-efficacy for higher performance.

Second, for employees, being aware of the social comparison triggered by supervisor gossip and its potential effects is crucial. Since individuals can embrace both performance goals and learning goals simultaneously (Button et al., 1996), we suggest high-PGO employees temper their performance goals when exposed to supervisor positive gossip. Instead, they should adopt a constructive learning mindset towards the targets of supervisor positive gossip. Moreover, organizations should recognize that even well-intentioned comments by supervisors can be interpreted seriously by employees, leading to unintended consequences for work efficacy and performance. Organizations are encouraged to develop leadership coaching programs focused on communication skills and establish formal channels for performance feedback. In addition, we recommend that organizations adopt absolute performance evaluation standards rather than relative ones, particularly in settings where employees generally exhibit higher PGO. By relying more on formal feedback channels and absolute evaluation criteria, these organizations can mitigate the risk of employees experiencing reduced self-efficacy due to informal feedback, such as supervisor positive gossip.

6 Limitations and future directions

Despite its contributions, our research suffers from several limitations that warrant future investigation.

First, although our theoretical model draws on social comparison theory and posits perceived attainability as the key condition for whether upward comparisons yield assimilation or contrast effects (Mussweiler et al., 2004), we did not measure perceived attainability directly. Instead, we treated PGO as a proxy for individuals’ chronic beliefs about ability and the threat of upward comparisons. While theoretically grounded, this approach limits the precision of our inferences. Future research should consider directly assessing perceived attainability, possibly via experiments or validated measures, to better isolate its role in shaping responses to supervisor positive gossip.

Second, all data were collected from a single sales company in China, which may constrain the generalizability of our findings. Cultural norms surrounding authority, hierarchy, and indirect communication (such as gossip) may vary across cultures and industries, influencing how supervisor positive gossip is interpreted. We recommend future studies conduct cross-cultural and cross-industry replications to examine the robustness and boundary conditions of the observed effects.

Third, we used questionnaires to collect retrospective ratings of supervisor gossip, which lacks accuracy compared to real-time record methods such as laboratory experiments and naturalistic observations. Researchers have pointed out that since gossip is more like a private behavior, it is especially sensitive to research methods (Wert and Salovey, 2004). We acknowledge innovative attempts like the Electronically Activated Recorder (EAR) method adopted by Robbins and Karan (2020) to capture workplace gossip in real time. We encourage future studies to adopt such experimental or observational approaches in the natural workplace settings for more accurate insights.

Fourth, all variables in our study were collected through quantitative surveys, which may limit the depth of understanding of how employees interpret gossip and attribute meaning to it. Future studies could benefit from qualitative approaches such as interviews or open-ended diary studies to explore employees’ subjective experiences and sensemaking processes in response to supervisor positive gossip. Such methods may uncover additional boundary conditions or mediating mechanisms that are difficult to detect through standardized measurements.

Finally, while our outcome variable, job performance, was rated by supervisors, it still relied on subjective evaluations. Future research could incorporate objective indicators, such as actual sales figures or performance metrics, to more accurately assess the behavioral implications of gossip-related processes and mitigate potential biases in supervisory ratings.

7 Conclusion

By adopting a balanced view of workplace gossip, our research delves into the contingent effects of supervisor positive gossip on employees’ self-efficacy and job performance. Through the lens of social comparison theory and goal orientation theory, we found that supervisor positive gossip prompts receivers to make upward comparisons with the gossip targets, thereby enhancing their self-efficacy and job performance for low-PGO receivers, while diminishing the self-efficacy and job performance of high-PGO receivers. We aspire for this research to stimulate broad academic curiosity in the investigation of supervisor gossip, especially concerning the varied outcomes it may have on the individuals involved.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

FZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aiken, L. S., and West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: goals, structures, and student motivation. J. Educ. Psychol. 84, 261–271. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.84.3.261

Bai, Y., Wang, J., Chen, T., and Li, F. (2020). Learning from supervisor negative gossip: the reflective learning process and performance outcome of employee receivers. Hum. Relat. 73, 1689–1717. doi: 10.1177/0018726719866250

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 37, 122–147. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

Beersma, B., and Van Kleef, G. A. (2012). Why people gossip: an empirical analysis of social motives, antecedents, and consequences. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 42, 2640–2670. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00956.x

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 107, 238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Blanton, H., Buunk, B. P., Gibbons, F. X., and Kuyper, H. (1999). When better-than-others compare upward: choice of comparison and comparative evaluation as independent predictors of academic performance. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 76, 420–430. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.420

Brady, D. L., Brown, D. J., and Liang, L. H. (2017). Moving beyond assumptions of deviance: the reconceptualization and measurement of workplace gossip. J. Appl. Psychol. 102, 1–25. doi: 10.1037/apl0000164

Brislin, R. W. (1980). “Translation and content analysis of oral and written material” in Handbook of cross-cultural psychology. eds. H. C. Triandis and J. W. Berry (Boston: Allyn and Bacon), 349–444.

Brown, J. D., Novick, N. J., Lord, K. A., and Richards, J. M. (1992). When Gulliver travels: social context, psychological closeness, and self-appraisals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 62, 717–727. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.62.5.717

Browne, M. W., and Cudeck, R. (1993). “Alternative ways of assessing model fit” in Testing structural equation models. eds. J. A. Bollen and J. S. Long (Newbury Park, CA: SAGE), 136–162.

Button, S. B., Mathieu, J. E., and Zajac, D. M. (1996). Goal orientation in organizational research: a conceptual and empirical foundation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 67, 26–48. doi: 10.1006/obhd.1996.0063

Buunk, A. P., and Gibbons, F. X. (2007). Social comparison: the end of a theory and the emergence of a field. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 102, 3–21. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.007

Chen, G., Gully, S. M., and Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organ. Res. Methods 4, 62–83. doi: 10.1177/109442810141004

Cohen-Charash, Y., and Mueller, J. S. (2007). Does perceived unfairness exacerbate or mitigate interpersonal counterproductive work behaviors related to envy? J. Appl. Psychol. 92, 666–680. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.666

Collins, R. L. (1996). For better or worse: the impact of upward social comparison on self-evaluations. Psychol. Bull. 119, 51–69. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.51

Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: what, why, when, and how. J. Bus. Psychol. 29, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7

Dores Cruz, T. D., Beersma, B., Dijkstra, M. T. M., and Bechtoldt, M. N. (2019). The bright and dark side of gossip for cooperation in groups. Front. Psychol. 10:1374. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01374

Dores Cruz, T. D., Nieper, A. S., Testori, M., Martinescu, E., and Beersma, B. (2021a). An integrative definition and framework to study gossip. Group Org. Manag. 46, 252–285. doi: 10.1177/1059601121992887

Dores Cruz, T. D., Thielmann, I., Columbus, S., Molho, C., Wu, J., Righetti, F., et al. (2021b). Gossip and reputation in everyday life. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 376:20200301. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2020.0301

Downes, P. E., Crawford, E. R., Seibert, S. E., Stoverink, A. C., and Campbell, E. M. (2021). Referents or role models? The self-efficacy and job performance effects of perceiving higher performing peers. J. Appl. Psychol. 106, 422–438. doi: 10.1037/apl0000519

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. Am. Psychol. 41, 1040–1048. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1040

Edwards, J. R., and Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: a general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 12, 1–22. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1

Elliot, A. J. (2005). “A conceptual history of the achievement goal construct” in Handbook of competence and motivation. eds. A. J. Elliot and C. S. Dweck (New York: Guilford Publications), 52–72.

Elliot, A. J., and Church, M. A. (1997). A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 72, 218–232. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.218

Ellwardt, L., Labianca, G., and Wittek, R. (2012). Who are the objects of positive and negative gossip at work?. A social network perspective on workplace gossip. Soc. Networks 34, 193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2011.11.003

Enders, C. K., and Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: a new look at an old issue. Psychol. Methods 12, 121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 7, 117–140. doi: 10.1177/001872675400700202

Foster, E. K. (2004). Research on gossip: taxonomy, methods, and future directions. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 8, 78–99. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.78

Gerber, J. P., Wheeler, L., and Suls, J. (2018). A social comparison theory meta-analysis 60+ years on. Psychol. Bull. 144, 177–197. doi: 10.1037/bul0000127

Gist, M. E., and Mitchell, T. R. (1992). Self-efficacy: a theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Acad. Manag. Rev. 17, 183–211. doi: 10.5465/amr.1992.4279530

Greenberg, J., Ashton-James, C. E., and Ashkanasy, N. M. (2007). Social comparison processes in organizations. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 102, 22–41. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.006

Grosser, T. J., Lopez-Kidwell, V., Labianca, G., and Ellwardt, L. (2012). Hearing it through the grapevine. Positive and negative workplace gossip. Organ. Dyn. 41, 52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2011.12.007

Hogg, M. A. (2000). “Social identity and social comparison” in Handbook of social comparison: Theory and research. eds. J. Suls and L. Wheeler (New York, NY: Kluwer/Plenum Press), 401–421.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Second Edn. London: Guilford Publications.

Kong, M. (2018). Effect of perceived negative workplace gossip on employees’ behaviors. Front. Psychol. 9, 1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01112

Kuo, C. C., Chang, K., Quinton, S., Lu, C. Y., and Lee, I. (2015). Gossip in the workplace and the implications for HR management: a study of gossip and its relationship to employee cynicism. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 26, 2288–2307. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2014.985329

Kuo, C. C., Wu, C. Y., and Lin, C. W. (2018). Supervisor workplace gossip and its impact on employees. J. Manag. Psychol. 33, 93–105. doi: 10.1108/JMP-04-2017-0159

Kurland, N. B., and Pelled, L. H. (2000). Passing the word: toward a model of gossip and power in the workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 25, 428–438. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2000.3312928

LeBreton, J. M., and Senter, J. L. (2008). Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organ. Res. Methods 11, 815–852. doi: 10.1177/1094428106296642

Lee, F. K., Sheldon, K. M., and Turban, D. B. (2003). Personality and the goal-striving process: the influence of achievement goal patterns, goal level, and mental focus on performance and enjoyment. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 256–265. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.256

Levin, J., and Arluke, A. (1985). An exploratory analysis of sex differences in gossip. Sex Roles 12, 281–286. doi: 10.1007/BF00287594

Lockwood, P., Jordan, C. H., and Kunda, Z. (2002). Motivation by positive or negative role models: regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83, 854–864. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.4.854

Lockwood, P., and Kunda, Z. (1997). Superstars and me: predicting the impact of role models on the self. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 73, 91–103. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.91

Lockwood, P., and Kunda, Z. (2000). “Psychological perspectives on self and identity” in Psychological perspectives on self and identity. eds. A. Tesser, R. B. Felson, and J. M. Suls (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 147–171.

Martinescu, E., Janssen, O., and Nijstad, B. A. (2014). Tell me the gossip: the self-evaluative function of receiving gossip about others. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 40, 1668–1680. doi: 10.1177/0146167214554916

Massar, K., Buunk, A. P., and Rempt, S. (2012). Age differences in women’s tendency to gossip are mediated by their mate value. Personal. Individ. Differ. 52, 106–109. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.09.013

Matta, F. K., and Van Dyne, L. (2020). Understanding the disparate behavioral consequences of LMX differentiation: the role of social comparison emotions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 45, 154–180. doi: 10.5465/amr.2016.0264

Michelson, G., van Iterson, A., and Waddington, K. (2010). Gossip in organizations: contexts, consequences, and controversies. Group Org. Manag. 35, 371–390. doi: 10.1177/1059601109360389

Mills, C. (2010). Experiencing gossip: the foundations for a theory of embedded organizational gossip. Group Org. Manag. 35, 213–240. doi: 10.1177/1059601109360392

Mussweiler, T., Rüter, K., and Epstude, K. (2004). The ups and downs of social comparison: mechanisms of assimilation and contrast. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 87, 832–844. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.832

Ng, T. W. H., and Feldman, D. C. (2009). How broadly does education contribute to job performance? Pers. Psychol. 62, 89–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.01130.x

Ng, T. W. H., and Feldman, D. C. (2010). Organizational tenure and job performance. J. Manag. 36, 1220–1250. doi: 10.1177/0149206309359809

Payne, S. C., Youngcourt, S. S., and Beaubien, J. M. (2007). A meta-analytic examination of the goal orientation nomological net. J. Appl. Psychol. 92, 128–150. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.128

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Poortvliet, P. M., and Darnon, C. (2010). Toward a more social understanding of achievement goals: the interpersonal effects of mastery and performance goals. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 19, 324–328. doi: 10.1177/0963721410383246

Preacher, K. J., Curran, P. J., and Bauer, D. J. (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 31, 437–448. doi: 10.3102/10769986031004437

Robbins, M. L., and Karan, A. (2020). Who gossips and how in everyday life? Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 11, 185–195. doi: 10.1177/1948550619837000

Sedikides, C., and Gregg, A. P. (2008). Self-enhancement: food for thought. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 3, 102–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00068.x

Sedikides, C., and Skowronski, J. J. (2000). “On the evolutionary functions of the symbolic self: the emergence of selfevaluation motives” in Psychological perspectives on self and identity. eds. A. Tesser, R. Felson, and J. Suls (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 91–117.

Smith, R. H. (2000). “Assimilative and contrastive emotional reactions to upward and downward social comparisons” in Handbook of social comparison: Theory and research. eds. J. Suls and L. Wheeler (Dordrecht: Springer US), 173–200.

Spoelma, T. M., and Hetrick, A. L. (2021). More than idle talk: examining the effects of positive and negative team gossip. J. Organ. Behav. 42, 604–618. doi: 10.1002/job.2522

Stajkovic, A., and Luthans, F. (1998). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 124, 240–261.

Su, C., Yang, Z., Zhuang, G., Zhou, N., and Dou, W. (2009). Interpersonal influence as an alternative channel communication behavior in emerging markets: the case of China. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 40, 668–689. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2008.84

Suls, J. (1977). Gossip as social comparison. J. Commun. 27, 164–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1977.tb01812.x

Suls, J., Martin, R., and Wheeler, L. (2002). Social comparison: why, with whom, and with what effect? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 11, 159–163. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00191

Sun, T., Schilpzand, P., and Liu, Y. (2023). Workplace gossip: an integrative review of its antecedents, functions, and consequences. J. Organ. Behav. 44, 311–334. doi: 10.1002/job.2653

Tan, N., Yam, K. C., Zhang, P., and Brown, D. J. (2020). Are you gossiping about me? The costs and benefits of high workplace gossip prevalence. J. Bus. Psychol. 36, 417–434. doi: 10.1007/s10869-020-09683-7

Tesser, A. (1988). “Toward a self-evaluation maintenance model of social behavior” in Advances in experimental social psychology. ed. L. Berkowitz (New York: Academic Press), 181–227.

Torres, S., and Warren-Findlow, J. (2019). Aging alone, gossiping together: older adults’ talk as social glue. J. Gerontol. 74, 1474–1482. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby154

Tsui, A. S., Pearce, J. L., Porter, L. W., and Tripoli, A. M. (1997). Alternative approaches to the employee-organization relationship: does investment in employees pay off? Acad. Manag. J. 40, 1089–1121. doi: 10.2307/256928

VandeWalle, D., Brown, S., Cron, W., and Slocum, J. (1999). The influence of goal orientation and self-regulation tactics on sales performance: a longitudinal field test. J. Appl. Psychol. 84, 249–259. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.84.2.249

Watson, D. C. (2012). Gender differences in gossip and friendship. Sex Roles 67, 494–502. doi: 10.1007/s11199-012-0160-4

Weber, B., and Hertel, G. (2007). Motivation gains of inferior group members: a meta-analytical review. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 93, 973–993. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.973

Wert, S. R., and Salovey, P. (2004). A social comparison account of gossip. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 8, 122–137. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.122

Wu, L. Z., Birtch, T. A., Chiang, F. F. T., and Zhang, H. (2018). Perceptions of negative workplace gossip: a self-consistency theory framework. J. Manag. 44, 1873–1898. doi: 10.1177/0149206316632057

Wu, X., Kwan, H. K., Wu, L. Z., and Ma, J. (2018). The effect of workplace negative gossip on employee proactive behavior in China: the moderating role of Traditionality. J. Bus. Ethics 148, 801–815. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-3006-5

Zhong, R., Tang, P. M., and Lee, S. H. (2023). The gossiper’s high and low: investigating the impact of negative gossip about the supervisor on work engagement. Pers. Psychol. 77, 621–649. doi: 10.1111/peps.12571

Zhu, Q., Martinescu, E., Beersma, B., and Wei, F. (2022). How does receiving gossip from coworkers influence employees’ task performance and interpersonal deviance? The moderating roles of regulatory focus and the mediating role of vicarious learning. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 95, 213–238. doi: 10.1111/joop.12375

Keywords: supervisor positive gossip, self-efficacy, performance goal orientation, social comparison, workplace gossip

Citation: Zhang F and Zhu C (2025) The contingent effects of supervisor positive gossip on employee receivers: the moderating role of performance goal orientation. Front. Psychol. 16:1516309. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1516309

Edited by:

Yustinus Budi Hermanto, Universitas Katolik Darma Cendika, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Hao Zeng, Jiangxi Science and Technology Normal University, ChinaVeronika Agustini Srimulyani, Universitas Katolik Widya Mandala Madiun, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Zhang and Zhu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunling Zhu, emh1Y2h1bmxpbmdAcm1icy5ydWMuZWR1LmNu

Fangliang Zhang

Fangliang Zhang Chunling Zhu

Chunling Zhu