- 1Department of Kinesiology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 2Department of Nutritional Sciences, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 3School of Kinesiology, Department of Health Science, Western University, London, ON, Canada

Flourishing (i.e., positive mental health reflecting positive social relationships and sense of purpose and optimism) is important for experiencing growth, resilience, and functioning – especially in sport. Factors that may limit or potentiate the experience of flourishing in sport need to be understood. For girls involved in sport, weight-related shame may be a critical factor limiting the potential to flourish. The purpose of the present study was to explore current and anticipatory weight-related shame in association with flourishing among adolescent girls. Participants were Canadian girl athletes (N = 189) aged 13 to 18 years old (M = 15.93, SD = 1.22) who had previous or current involvement in organized sport. Girls completed a self-report survey where they reported their current and anticipatory (weight gain or loss) shame and flourishing. A Path model was tested in MPlus. Higher current weight shame [Estimate = −0.41, SE = 0.07, p < 0.01] and anticipatory weight loss shame [Estimate = −0.13,. SE = 0.07, p = 0.03], were associated with lower flourishing. Anticipatory weight gain shame was not associated with lower flourishing. These results suggest efforts are needed to disconnect the emotion of shame from weight change to foster positive psychological outcomes, such as flourishing, in sport contexts.

Introduction

Adolescence is a formative developmental period to foster positive mental health and well-being (Vijayakumar et al., 2018). Sport has been identified as an important opportunity to buffer mental illness and promote flourishing during adolescence (Eime et al., 2013). Flourishing is defined as high well-being (Keyes, 2002), and reflects an optimal state of functioning, resilience, and growth (Diener et al., 2010; Fredrickson and Losada, 2005). Adolescents who participate in sport report higher flourishing than peers with more sedentary hobbies (Kim et al., 2020). However, girls typically report poorer sport experiences and higher drop-out compared to boys (Canadian Women and Sport, 2020; Slater and Tiggemann, 2011), and the gendered influences that contribute to these patterns may impact not only sport-related experiences, but also more general well-being indicators such as flourishing.

Accumulating evidence suggests that the girls sport context can be appearance-focused, comparative, and evaluative of the body (Willson and Kerr, 2022; Vani et al., 2020), with a particularly strong focus on body weight. Girls have reported pressure from their coaches to lose or maintain their weight (Coppola et al., 2014; Voelker and Reel, 2015), and commentary about their weight from family, teammates, spectators, or opponents in sport (Lucibello et al., 2021a; Murray et al., 2022; Porter et al., 2013). Girls also perceive the importance of meeting a sport-related weight and body ideal, and that athletes can be favored based on weight as opposed to performance (de Oliveira et al., 2021; Lunde and Gattario, 2017). Critically, the perpetuation of body weight importance, stringent weight ideals, and weight management in girls sport may diminish flourishing in athletes by fostering body-related shame.

Body-related self-conscious emotions, an affective domain of body image, represent positive and negative emotions contextualized to the body’s appearance (Castonguay et al., 2014; Sabiston et al., 2020). Body-related shame is an intense negative self-conscious emotion elicited when one attributes perceived deviance from societal body standards to a flawed global self (Sabiston et al., 2010; Tracy and Robins, 2006). Girl athletes report body-related shame contextualized to their sport context (Coppola et al., 2014; Huellemann et al., 2023) and increases in body-related shame have been observed over time in girl athletes (Sabiston et al., 2020). Critically, higher current body-related shame has been associated with lower flourishing in girl athletes (Gilchrist et al., 2021), suggesting the body-related shame fostered in response to the weight-focused and evaluative sport context may impact flourishing.

However, two important limitations to the above evidence warrant consideration. First, examination of the association between body-related shame and flourishing has been limited by a focus on global body appearance as opposed to weight-specific shame that may be uniquely impacted by the weight-centric girls sport environment. Second, little is understood about anticipatory shame specific to weight changes in girl athletes. Anticipatory shame describes how ashamed an individual perceives they would feel in response to a situation that could occur (e.g., shame in response to weight gain). Anticipatory shame may be particularly relevant to girl athletes, as Objectification Theory highlights that girls are generally socialized to anticipate how others will view and evaluate their bodies (Fredrickson and Roberts, 1997). These tendencies for objectification and subsequent shame may be exacerbated within the highly evaluative girls sport context which contains explicit weight and body commentary and ideals (Lucibello et al., 2021a; Murray et al., 2022). Being in a normalized weight-focused environment while witnessing favoritism and bias toward athletes of a certain weight may make girl athletes vulnerable to high anticipatory shame, due to regular messaging about how weight changes could negatively impact their sport experiences and performance.

Importantly, anticipatory emotions have unique influences on behavioral and psychological outcomes above and beyond current emotions (Troop et al., 2006). Anticipatory body-related shame in response to weight gain has been associated with numerous maladaptive outcomes, including depressive symptoms, excessive exercise, fasting, dieting, body checking, binge eating, and fear of weight gain (Troop, 2016; Troop and Redshaw, 2012). While anticipatory emotions are often investigated as motivators of goal-directed behaviors (Pila et al., 2021) they may also be related to aspects of well-being and flourishing. Given that sport is considered a channel to promote flourishing in adolescence (Eime et al., 2013), understanding whether anticipatory weight-related shame may diminish flourishing is an important consideration for girl athletes.

The present study examined (i) mean differences in current and anticipatory weight-related shame, and (ii) the associations among current weight-related shame, anticipatory weight-related shame, and flourishing in adolescent girl athletes. Based on theoretical tenets and empirical evidence (Fredrickson and Roberts, 1997; Gilchrist et al., 2021; Troop, 2016), it was hypothesized that higher (i) current weight shame and (ii) anticipated weight gain/loss shame, would be associated with lower flourishing.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Data were drawn from a prospective longitudinal cohort study of adolescent girl athletes enrolled in organized team-based sport, recruited at an average age of 14 from the Greater Toronto Area and followed for three additional years (Sabiston et al., 2020). Study advertisements were relayed to coaches of girls sport teams and administrators at local sport organizations on “the effect of playing organized sport on the mental, physical, and social well-being of adolescent girls.” Any adolescent enrolled on a girls team that coaches or administrators contacted was eligible to participate. Following participant assent and parental consent, participants completed a 20–30-min survey in a group setting supervised by trained research assistants. Participants were compensated with a gift card ($10 CAD) and given the option to be contacted for yearly follow-up online surveys. Data for the current analysis (n = 189) is from the third time point, approximately 2 years following baseline when the girls were an average of 16 years old, as this wave is when measures of anticipatory weight-related emotions were included. This sample size is consistent with sample size estimates for path modeling which suggest at least 10 participants per parameter (Bentler and Chou, 1987). All study procedures were approved by the University of Toronto research ethics board.

Measures

Demographic characteristics

Participants reported their age, ethnicity, sport status, height (ins) and weight (lbs), to calculate body mass index (BMI)-for-age growth percentiles (De Onis and Onyango, 2008).

Weight-related shame

The 15-shame items from the 30-item Bodily Pride Shame Scale (BPSS) measured behavioral, affective and attitudinal aspects of current and anticipated weight shame (Troop, 2016). The BPSS has three subscales: current weight, anticipated weight gain (~ 15 lbs), and anticipated weight loss (~ 15 lbs). Each subscale contains five items (e.g., “I am/would feel ashamed of my body”) with responses ranging from 1 (not at all true of me) to 10 (completely true of me). The items in each subscale are identical except for the time frame (current, anticipated) and weight change direction (loss, gain). Higher mean subscale scores indicate greater weight shame. Adequate internal consistency was noted for current weight shame (α = 0.82), anticipatory weight gain shame (α = 0.90), and anticipatory weight loss shame (α = 0.83).

Flourishing

The 8-item Flourishing Scale (Diener et al., 2010) was used to measure participants’ self-perceived positive functioning and success in areas ranging from relationships, self-esteem, purpose, and optimism (e.g., “my social relationships are supportive and rewarding”). Items are answered on a 7-item Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with higher mean scores reflecting higher levels of flourishing (α = 0.90).

Data analysis

Normality was assessed for continuous variables, and descriptives, Cronbach’s alpha, and bivariate correlations were computed. Paired sample t-tests compared the mean differences in shame (current, anticipatory gain, anticipatory loss), and a path model with maximum likelihood robust estimation was tested in MPlus Version 8.5 (Muthén and Muthén, 2019). The hypothesized positive correlation between current shame, weight gain shame, and weight loss shame, was specified. The empirically supported variables of body mass index (continuous, age- and sex-based percentile; De Onis and Onyango, 2008) and current sport participation (yes/no) were selected a-priori and included as covariates (Goldstein et al., 2021; Kim and Jang, 2018). Model fit was assessed using comparative fit index (CFI; values ≥ 0.95), standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR; ≤ 0.08), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; < 0.10) (Browne and Cudeck, 1993; Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Results

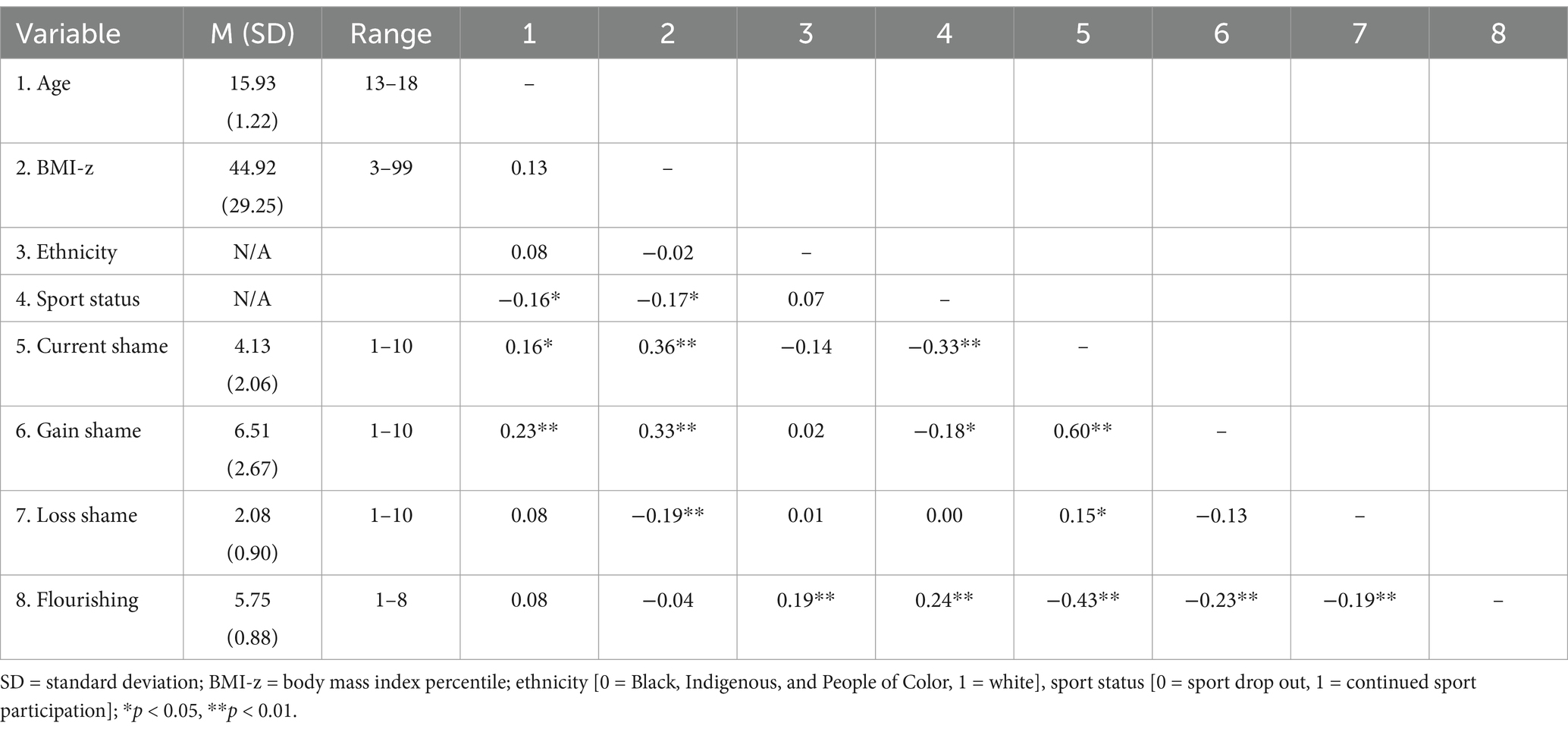

Demographic characteristics, means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations are presented in Table 1. Girls were an average of 15.93 years (SD = 1.22 years), while the mean BMI-for-age percentile was 44.9th (SD = 29.3rd percentile). Participants predominantly identified as White (n = 150, 74.6%) followed by another ethnicity (n = 11, 6%), multiple ethnicities (n = 9, 4.5%), Black (n = 7, 3.5%), Chinese (n = 7, 3.5%), and South Asian (n = 6, 3.0%). Most participants (n = 127, 67%) were participating in sports at the third time point; girls most commonly reported soccer as their primary sport (n = 113, 56.2%), followed by hockey (n = 24, 11.9%), swimming (n = 21, 10.4%), gymnastics (n = 8, 4.0%), and skiing (n = 6, 3.0%). All other primary sports (n = 12, e.g., dance, volleyball) were endorsed by under 3% of the sample.

Table 1. Score ranges, means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlation coefficients of main study variables (n = 189).

Participants reported significantly higher anticipatory weight gain shame (M = 6.51, SD = 2.67) than current shame (M = 4.00, SD = 2.06) [t(376) = −9.6, p < 0.01], and lower anticipatory weight loss shame (M = 2.08, SD = 0.89) than current shame [t(376) = 12.50, p < 0.01].

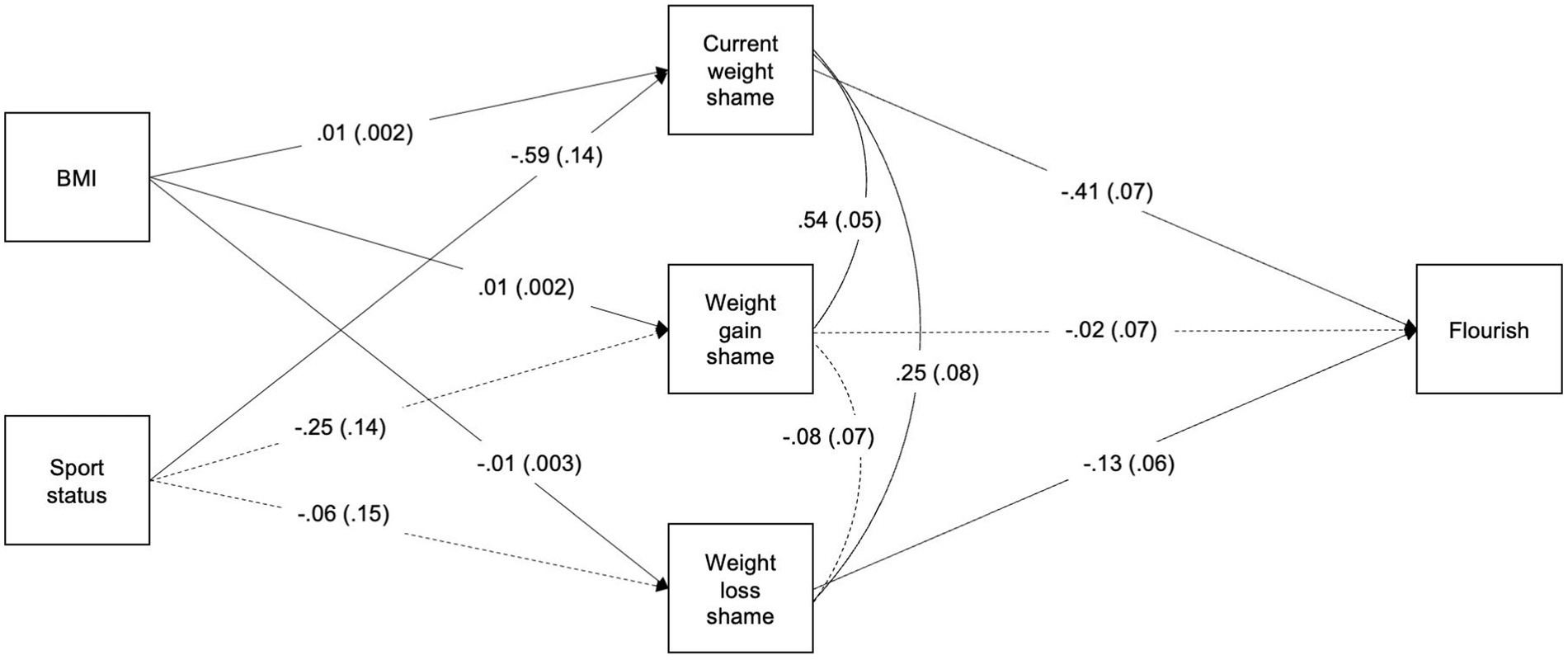

The final path model demonstrated adequate fit [χ2(2) = 5.28, p = 0.07; CFI = 0.98; SRMR = 0.03; RMSEA = 0.09 (90% CI = 0.00, 0.19)], with full path models results presented in Figure 1. Higher current weight-related shame [Estimate = −0.41, SE = 0.07, p < 0.01] and anticipatory weight loss shame [Estimate = −0.13,. SE = 0.07, p = 0.03], but not anticipatory weight gain shame, were associated with lower flourishing.

Figure 1. Path model representing the associations among current weight-related shame, anticipatory weight-related shame, and flourishing, after controlling for sport status and BMI. BMI = body mass index (age and sex-percentile), sport status = 1 (yes currently participating in sport), 2 (no longer participating in sport), flourish = flourishing. Significant paths indicated by solid arrows (p < 0.05), nonsignificant paths indicated by dashed arrows.

Discussion

The current study examined the associations between current and anticipatory shame and flourishing. Consistent with previous evidence (Troop, 2016), girls reported significantly higher levels of anticipatory weight gain shame than current weight shame or weight loss shame. However, only higher current shame and anticipated weight loss shame were associated with lower flourishing. This study extends previous research by utilizing weight-contextualized measures of shame to capture the potential body image ramifications of the weight-focused nature of girls’ sports. These findings also extend understanding of the impact of anticipatory emotions on flourishing and offer further support for larger-scale changes to girls’ sport (i.e., mandating weight neutral language, sport leaders emphasizing body functionality as opposed to appearance, body diverse imagery; Koulanova et al., 2021) that may mitigate current and anticipatory weight-related shame.

Although low average levels were reported relative to current and anticipatory weight gain shame, higher anticipated shame in response to weight loss was associated with lower flourishing. Given the focus on current emotional experiences in research involving girl athletes, these findings suggest that broadening assessments of body image to include anticipatory emotions may provide a more nuanced understanding of how the girls sport context contributes to negative body image, as well as how body image relates to psychological outcomes in girl athletes. Anticipatory weight loss shame relating to flourishing may indicate adolescent girl athletes’ investment in maintaining a particular weight within sport, consistent with messaging of weight maintenance from some coaches (Coppola et al., 2014; Lucibello et al., 2021a). Identifying girls who may be more vulnerable to anticipatory weight loss shame may be a useful approach to mitigating feelings of anticipatory shame. For example, self-objectification was associated with anticipatory shame in a previous reporting of this sample (Pila et al., 2021). Similarly, internalized weight stigma has been associated with higher current body-related shame in young women (Lucibello et al., 2021b). Anticipating shame in response to weight loss may reflect greater investment in body weight and appearance (Cash et al., 2004), or internalization of weight norms and societal standards (Tiggemann, 2011), which may also relate to lower flourishing. Therefore, more complex pathways that may explain the association between anticipatory shame and flourishing should also be investigated. For example, anticipatory shame promotes engagement in negative behaviors such as fasting and compulsive exercise (Troop and Redshaw, 2012), which may be an indirect pathway that reduces flourishing over time. Longitudinal research is imperative for understanding the interpersonal factors that predict anticipatory shame and the mechanisms through which anticipatory weight loss shame may reduce flourishing in girl athletes.

Although the high levels of anticipatory weight gain shame are consistent with the pervasive fat bias and weight stigma that exist within girls sport (Coppola et al., 2014; Huellemann et al., 2023; Sabiston et al., 2020), anticipatory weight gain shame was not significantly associated with flourishing among girl athletes, while controlling for covariates and accounting for current and anticipated weight loss shame. However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the measure in understanding anticipatory shame for weight gain among adolescent girls. Anticipatory weight gain shame was the highest type of shame reported; a high and relatively ubiquitous emotional response may suggest the 15-pound weight gain scale is too drastic to capture nuance or variability in this age group relative to young adult women (Troop, 2016). The bivariate correlation was also significant between anticipatory weight gain shame and flourishing in the expected direction. Therefore, future research that investigates anticipated shame in response to more subtle or variable changes in weight gain is integral for understanding adolescent girls’ experiences of weight gain shame within the weight-centric and fat phobic sport context.

Consistent with previous literature examining global appearance emotions as well as general negative emotions as contributors to reduced flourishing (Fredrickson and Losada, 2005; Gilchrist et al., 2021), higher current weight-related shame was related to lower flourishing. While body-related shame has been identified as an important target for improving sport experiences for girl athletes (Pila et al., 2020) these findings also support the importance of considering their influence on psychological factors outside of the sport context.

While causation cannot be inferred due to the cross-sectional design, these findings suggest that reducing current and anticipatory weight-related shame in girl athletes may foster and optimize their potential for flourishing. This may be done by reducing weight- and body-related comments and pressures within the sport environment (Koulanova et al., 2021). The pervasiveness of weight ideals, commentary, and pressures in girls sport (Coppola et al., 2014; Lucibello et al., 2021a) has been noted as a significant distraction for girl athletes (Lauer et al., 2018) and can contribute to poorer sport experiences and drop out (Pila et al., 2020). Negative sport experiences may in turn foster shame, potentially reducing flourishing; notably, a reduction in flourishing may lead to lasting negative health behaviors (e.g., disordered eating; Zemestani et al., 2021) and sport drop out (Sabiston et al., 2020).

There are some study limitations to address. First, there are additional negative body-related self-conscious emotions (e.g., guilt, embarrassment) that could not be investigated due to a lack of validated anticipatory measures. Additionally, the girl athletes were predominantly White, limiting statistical power for examining associations across race or ethnicity. Due to limited sample size investigation into differences based on sport (i.e., hockey vs. swimming) and sport features (i.e., aesthetic vs. non-aesthetic, team vs. individual sport; Abbott and Barber, 2011; De Bruin et al., 2007) could also not be explored. Similarly, by only examining girls in sport as opposed to comparing mean levels and associations with girls not in sport, the impact of the sport environment in fostering shame cannot be determined. Lastly, the cross-sectional data warrants further investigation into the associations among anticipatory emotions and flourishing over time.

In conclusion, this study provides preliminary support for the associations among current and anticipatory weight loss shame and flourishing in girl athletes. Future longitudinal and experience sampling studies will provide important insight into the mechanisms, moderators, and outcomes of current and anticipatory shame, contributing to the enhancement of girls’ sport experiences and well-being.

Data availability statement

Data is only available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Toronto Research Ethics Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin, and participants provided informed assent.

Author contributions

KL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. TZ: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. DB: Writing – review & editing. EP: Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. CS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. KL was supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Postdoctoral Fellowship at manuscript submission, and a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Doctoral Fellowship when manuscript preparation began. CS holds a Canada Research Chair in Physical Activity and Mental Health. Funding for this project was provided through a SSHRC Insight grant awarded to CS (862-2013-0005). The funding agency was not involved in data collection, analysis, or interpretation, nor manuscript preparation or submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbott, B. D., and Barber, B. L. (2011). Differences in functional and aesthetic body image between sedentary girls and girls involved in sports and physical activity: does sport type make a difference? Psychol. Sport Exerc. 12, 333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2010.10.005

Bentler, P. M., and Chou, C. P. (1987). Practical issues in structural equation modeling. Sociol. Meth. Res. 16, 78–117. doi: 10.1177/0049124187016001004

Browne, M. W., and Cudeck, R. (1993). “Alternative ways of assessing model fit” in Testing structural equation models. eds. K. A. Bollen and J. S. Long (Newbury Park, CA: Sage), 136–162.

Canadian Women and Sport (2020). The rally report: encouraging action to improve sport for women and girls. Available online at: https://womenandsport.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Canadian-Women-Sport_The-Rally-Report.pdf. (Accessed November 1, 2024).

Cash, T. F., Melnyk, S. E., and Hrabosky, J. I. (2004). The assessment of body image investment: an extensive revision of the appearance schemas inventory. Int. J. Eat.Disord. 35, 305–316. doi: 10.1002/eat.10264

Castonguay, A. L., Sabiston, C. M., Crocker, P. R. E., and Mack, D. E. (2014). Development and validation of the body and appearance self-conscious emotions scale (BASES). Body Image 11, 126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.12.006

Coppola, A. M., Ward, R. M., and Freysinger, V. J. (2014). Coaches’ communication of sport body image: experiences of female athletes. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 26, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2013.766650

De Bruin, A. K., Oudejans, R. R., and Bakker, F. C. (2007). Dieting and body image in aesthetic sports: a comparison of Dutch female gymnasts and non-aesthetic sport participants. Psychol. Sport. Exer. 8, 507–520. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.10.002

de Oliveira, L., Costa, V. R., Antualpa, K. F., and Nunomura, M. (2021). Body and performance in rhythmic gymnastics: science or belief? Sci. Gymnas. J. 13, 311–321. doi: 10.52165/sgj.13.3.311-321

De Onis, M., and Onyango, A. W. (2008). WHO child growth standards. Lancet 371:204. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60131-2

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D.-W., Oishi, S., et al. (2010). New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 97, 143–156. doi: 10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J., and Payne, W. R. (2013). A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 10, 98–21. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-98

Fredrickson, B. L., and Losada, M. F. (2005). Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. Am. Psychol. 60, 678–686. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.678

Fredrickson, B. L., and Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: toward understanding women's lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychol. Women Quart. 21, 173–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

Gilchrist, J. D., Lucibello, K. M., Pila, E., Crocker, P. R. E., and Sabiston, C. M. (2021). Emotion profiles among adolescent female athletes: associations with flourishing. Body Image 39, 166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.08.003

Goldstein, E., Topitzes, J., Miller-Cribbs, J., and Brown, R. L. (2021). Influence of race/ethnicity and income on the link between adverse childhood experiences and child flourishing. Pediatr. Res. 89, 1861–1869. doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-01188-6

Hu, L. T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Huellemann, K. L., Ens, G., Gray, E., Osa, M. L., and Pila, E. (2023). “If I talk about it, I’m weak, and I’m supposed to be strong”: experiences of body-related shame in women athletes. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 22, 1819–1842. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2023.2238277

Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life.J. Health Soc. Behav. 43, 207–222. doi: 10.2307/3090197

Kim, T. E., and Jang, C. Y. (2018). The relationship between children's flourishing and being overweight. J Exerc. Rehabil. 14, 598–605. doi: 10.12965/jer.1836208.104

Kim, T., Jang, C. Y., and Kim, M. (2020). Socioecological predictors on psychological flourishing in the US adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:7919. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217917

Koulanova, A., Sabiston, C. M., Pila, E., Brunet, J., Sylvester, B., Sandmeyer-Graves, A., et al. (2021). Ideas for action: exploring strategies to address body image concerns for adolescent girls involved in sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 56:102017. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102017

Lauer, E. E., Zakrajsek, R. A., Fisher, L. A., Bejar, M. P., McCowan, T., Martin, S. B., et al. (2018). NCAA DII female student-athletes' perceptions of their sport uniforms and body image. J. Sport Behav. 41, 40–63.

Lucibello, K. M., Koulanova, A., Pila, E., Brunet, J., and Sabiston, C. M. (2021a). Exploring adolescent girls’ experiences of body talk in non-aesthetic sport. J. Adoles. 89, 63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.04.003

Lucibello, K. M., Nesbitt, A. E., Solomon-Krakus, S., and Sabiston, C. M. (2021b). Internalized weight stigma and the relationship between weight perception and negative body-related self-conscious emotions. Body Image 37, 84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.01.010

Lunde, C., and Gattario, K. H. (2017). Performance or appearance? Young female sport participants’ body negotiations. Body Image 21, 81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.03.001

Murray, R. M., Lucibello, K. M., Pila, E., Maginn, D., Sandmeyer-Graves, A., and Sabiston, C. M. (2022). “Go after the fatty”: the problematic body commentary referees hear—and experience—in adolescent girls’ sport. Sport. Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 11, 1–11. doi: 10.1037/spy0000282

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (2019). Mplus Version 8.5 (8.5). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén.

Pila, E., Gilchrist, J. D., Huellemann, K. L., Adam, M. E. K., and Sabiston, C. M. (2021). Body surveillance prospectively linked with physical activity via body shame in adolescent girls. Body Image 36, 276–282. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.01.002

Pila, E., Sabiston, C. M., Mack, D. E., Wilson, P. M., Brunet, J., Kowalski, K. C., et al. (2020). Fitness- and appearance-related self-conscious emotions and sport experiences: a prospective longitudinal investigation among adolescent girls. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 47:101641. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101641

Porter, R. R., Morrow, S. L., and Reel, J. J. (2013). Winning looks: body image among adolescent female competitive swimmers. Qual. Res. Sport. Exerc. Health. 5, 179–195. doi: 10.1080/2159676x.2012.712983

Sabiston, C. M., Brunet, J., Wilson, P. M., and Mack, D. E. (2010). The role of body-related self conscious emotions in motivating women’s physical activity. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 32, 417–437. doi: 10.1123/jsep.32.4.417

Sabiston, C. M., Pila, E., Crocker, P. R. E., Mack, D. E., Wilson, P. M., Brunet, J., et al. (2020). Changes in body-related self-conscious emotions over time among youth female athletes. Body Image 32, 24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.11.001

Slater, A., and Tiggemann, M. (2011). Gender differences in adolescent sport participation, teasing, self-objsctification and body image concerns. J. Adoles. 34, 455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.06.007

Tiggemann, M. (2011). “Sociocultural perspectives on human appearance and body image” in Body image: A handbook of science, practice, and prevention. eds. T. F. Cash and L. Smolak (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 12–19.

Tracy, J. L., and Robins, R. W. (2006). Appraisal antecedents of shame and guilt: support for a theoretical model. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 32, 1339–1351. doi: 10.1177/0146167206290212

Troop, N. A. (2016). The effect of current and anticipated body pride and shame on dietary restraint and caloric intake. Appetite 96, 375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.039

Troop, N. A., and Redshaw, C. (2012). General shame and bodily shame in eating disorders: a 2.5-year longitudinal study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 20, 373–378. doi: 10.1002/erv.2160

Troop, N., Sotrilli, S., Serpell, L., and Treasure, J. (2006). Establishing a useful distinction between current and anticipated bodily shame in eating disorders. Eat. Weight. Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bul. Obes. 11, 83–90. doi: 10.1007/BF03327756

Vani, M. F., Pila, E., deJonge, M., Solomon-Krakus, S., and Sabiston, C. M. (2020). ‘Can you move your fat ass off the baseline?’ Exploring the sport experiences of adolescent girls with body image concerns. Qual. Res. Sport. Exerc. Health. 13, 671–689. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2020.1771409

Vijayakumar, N., Op de Macks, Z., Shirtcliff, E. A., and Pfeifer, J. H. (2018). Puberty and the human brain: insights into adolescent development. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 92, 417–436. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.06.004

Voelker, D. K., and Reel, J. J. (2015). An inductive thematic analysis of female competitive figure skaters’ experiences of weight pressure in sport. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 9, 297–316. doi: 10.1123/jcsp.2015-0012

Willson, E., and Kerr, G. (2022). Body shaming as a form of emotional abuse in sport. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 20, 1452–1470. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2021.1979079

Keywords: body-related shame, self-conscious emotions, athletes, youth, body image, positive mental health

Citation: Lucibello KM, Zeitoun T, Brown DM, Pila E and Sabiston CM (2025) The associations between current and anticipatory weight-related shame and flourishing in adolescent girls in sport. Front. Psychol. 16:1535766. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1535766

Edited by:

Rubén Maneiro, University of Vigo, SpainReviewed by:

Gaurav Singhal, University of Wisconsin-Madison, United StatesRachel Sweenie, Banner Health, United States

Copyright © 2025 Lucibello, Zeitoun, Brown, Pila and Sabiston. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Catherine M. Sabiston, Y2F0aGVyaW5lLnNhYmlzdG9uQHV0b3JvbnRvLmNh

†Present address: Kristen M. Lucibello, School of Kinesiology, Department of Health Science, Western University, London, ON, Canada

‡ORCID: Kristen M. Lucibello, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6614-2007

Tara Zeitoun, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5623-1997

David M. Brown, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5946-2774

Eva Pila, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5175-4329

Catherine M. Sabiston, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8419-6666

Kristen M. Lucibello

Kristen M. Lucibello Tara Zeitoun2‡

Tara Zeitoun2‡ David M. Brown

David M. Brown Eva Pila

Eva Pila Catherine M. Sabiston

Catherine M. Sabiston