Abstract

The rapid and non-predictable changes in various spheres of human and social life in the 21st century have shifted research focus to the perceived uncertainty stress. Although observations show that the uncertainty stress exists and influences individuals in Russia, no significant attention has been paid to how we can measure it. Previous study presented the instrument for measuring uncertainty stress—a Russian “Subjective and Objective Uncertainty Stress (SOUS-14)” scale. The present study continues the work on validating this scale on different samples. It aims to examine SOUS-14 psychometric characteristics in university students, as well as to check its measurement invariance across gender groups and assess differences between them. The sample consisted of 621 Russian university students (mean age 19.09; 47.02% young women). The results confirmed high validity and reliability of the scale as well as its second-order factor structure. The study revealed that uncertainty stress construct is invariant across genders. It has been also shown that female students experience higher levels of uncertainty stress, than male students. Thus, the study confirmed that the developed scale has adequate statistical and psychometric characteristics, is applicable for studying uncertainty stress and its gender aspects, and can be used for research purposes.

1 Introduction

The problem of uncertainty as a cause of physiological and psychological stress is a well-developed field in psychology (e.g., Greco and Roger, 2003; Peters et al., 2017). Traditionally, uncertainty was associated with decision-making models and was understood as the presence of more than one alternative when the results of choosing one or the other are predicted probabilistically (Solntseva and Smolyan, 2009). Yet, in the 21st century the rapid and non-predictable changes in various spheres of human and social life have shifted researchers’ attention to the analysis of not only decision-making in uncertain situations, and somatic symptoms caused by them, but also subjective assessments of their perception, experience and evaluation as stressful (Fernández-García et al., 2024; McCarty et al., 2023; Sischka et al., 2024; Zolotareva, 2023), i.e., to the study of perceived stress. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the situation was aggravated by fears for life and health and the inconsistency of huge flows of information about the disease, its treatment and prevention (Stankovska et al., 2020; Santomauro et al., 2021; McCarty et al., 2023; Kornienko and Rudnova, 2023). It is no coincidence that the experts called this period the “pandemic of psychological uncertainty stress” (Sweeny et al., 2020).

Experiencing uncertainty stress might lead to severe consequences. Empirical research has linked the perception of uncertainty to decreased mental health (Phillimore and Cheung, 2021) and increased distress (Massazza et al., 2023). It has been shown that uncertainty stress reduces the ability to effectively cope with various life events, negatively affects self-esteem (Peng et al., 2021), and contributes to the development of negative emotional states (Wise et al., 2023). This problem is especially acute in late adolescence and young adulthood, as young individuals during their transition between life stages are engaged in professional self-determination and career exploration—a highly uncertain process due to rapid changes in occupational world (Othman et al., 2019; Morosanova et al., 2024). A large number of recent cross-section and longitudinal studies report an increase in the level of anxiety and distress in college and university students across different countries and regions (Knapstad et al., 2021; Zhai and Du, 2024; Zarowski et al., 2024; Brown and Papp, 2024; Brown et al., 2024) due to demographic and socio-economic aspects (Ahamed and Limbu, 2024), digital fatigue (Krishna and Rajan, 2025), ecological factors (Clayton, 2020; Zinchenko, 2021; Hamaideh et al., 2022). Evidence support that perceived uncertainty and intolerance to uncertainty are important predictors of the recent increase in stress symptoms and decrease in students’ well-being (Satici et al., 2022; Ben Salah et al., 2023). Thus, the data indicate the need to study not only the perceived stress in students, but also the stress associated with their perception of various life situations, including highly uncertain situations.

In this connection, it is important to distinguish between subjective and objective uncertainty stress.

Subjective uncertainty stress occurs when an individual is placed in a difficult ambiguous situation provoking negative stressful experiences and a decrease in psychological well-being. This type of uncertainty becomes a stressor when an individual’s resources (i.e., cognitive, personal, and regulatory competencies) are insufficient for overcoming it and it takes time to actualize or develop those resources (Hobfoll, 2011). This type of stress is well-researched in the studies of perceived stress and intolerance to uncertainty and their influence on various life outcomes (e.g., Arbona et al., 2021; Sultanova et al., 2021). Subjective uncertainty concerns individuals’ problem situations such as dissatisfaction with relationships, school and work difficulties, lack of support from family members (Chernousova, 2022).

Contrary, objective uncertainty stress is much less studied. It arises in response to a subject’s encounter with not just new global challenges, but also objectively unpredictable ones such as natural disasters, pandemics, revolutions, and wars. According to cognitive appraisal (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984) and conservation of resources theories (Hobfoll, 2011), situations of objective uncertainty are always stressors, since their main characteristic is the objective lack of information about their nature, dynamics, and consequences. One of the key characteristics of objective uncertainty stress is that individuals cannot fully cope with it using resources they possess (Kriger, 2014), only mitigate their impact by accumulating psychological and external resources. This is especially relevant for adolescents and young adults, as during the above-mention sensitive period of career exploration it is extremely important to be able to (a) assess how destructive objective uncertainty stress can be during this period; (b) develop support measures to reduce its impact.

Thus, a person’s experience of uncertainty stress is associated with the following aspects: (1) assessment of the situation as tense/stressful; (2) the type of uncertainty of the given situation; (3) presence/absence of resources for overcoming stress.

An important aspect of perceived stress in young adults (and uncertainty stress in particular) is gender differences. Current literature on this issue suggests that young adult females tend to experience overall higher levels of stress than young adult males (Graves et al., 2021). Recent findings on stress, anxiety and negative emotional states during COVID-19 pandemic confirm this trend: young adult females tend to demonstrate higher levels of stress, anxiety, emotional distress and depression than males (Prowse et al., 2021; Rodriguez-Besteiro et al., 2021; Zarowski et al., 2024). Though there was some evidence from Chinese college students that gender had no significant effects on stress symptoms, such as anxiety, during the pandemic (Cao et al., 2020), majority of contemporary researchers report gender differences in perceived stress and stress symptoms. As for gender differences in uncertainty stress, recent work by T. Yang and colleagues showed, that gender was not significant predictor of the uncertainty stress (Yang et al., 2025). Meanwhile, literature analysis shows little to no data on gender differences in specifically subjective and objective uncertainty stress, since these types of stress have not been thoroughly studied yet.

The resent research calls for re-evaluation of previously developed stress assessment instruments (i.e., Rao et al., 2024; Muysewinkel et al., 2024), as well as creation of the new ones (Olasina, 2023). However, most of the new tools were developed during COVID-19 pandemic and cannot be used for evaluating uncertainty stress in more broad contexts. At the same time, despite the wide range of available methods for stress assessment, researchers note that quite many of them have not been thoroughly adapted and validated for student samples (e.g., Fernández-García et al., 2024). To address these issues, we have developed a new instrument—“Subjective and Objective Uncertainty Stress (SOUS-14),” presented in the article “Diagnostics of Stress of Subjective and Objective Uncertainty: Development and Validation of a Questionnaire” (Morosanova et al., 2024). This previous work was focused primarily on developing the concept of subjective and objective uncertainty stress and the instrument for its measurement. It also examined the differences in uncertainty stress between students who chose different educational tracks: college vs. university. Since we found significant differences in the level of uncertainty stress between university and college students, and due to the small sample of university students, the initial validation of the scale was carried out exclusively on a sample of college students.

The present study redresses these limitations and aims at: (1) psychometric evaluation of “Subjective and Objective Uncertainty Stress (SOUS-14)” scale on a large sample of Russian university students; (2) analysis of its measurement invariance and the gender sensitivity in terms of subjective and objective uncertainty stress.

2 Methods

2.1 Sample

The study involved undergraduate students aged 17 to 25 years attending state universities in Central (Moscow, Kaluga) region of Russia. Data was collected between October 2024 and January 2025. The questionnaires were administered via online “Testograf” platform.1 Using online administration has many advantages, primarily related to reducing the costs of study and the possibility to speed up data collection. However, these types of studies are susceptible to a number of selection biases associated with non-probability selection of respondents, such as “self-selection” (De Man et al., 2021), low response rate (Wu et al., 2022), etc. Although in our study we used the non-probability sampling method (conditional sampling), possible selection biases were controlled during the questionnaire administration procedure, which included: (1) providing links to the online-questionnaire in a controlled environment (classrooms in the presence of a lecturer); (2) eliminating the possibility of repeated completion by the same respondent; (3) including of a larger number of students from STEM specialties in the sample to equalize the number of young women and men (since the gender ratio in the social and humanitarian fields is often shifted toward a larger number of women). Participation in the study was encouraged by benefits during the post-term exams (additional points, fewer questions on the exam, etc.). Access to the questionnaires was provided individually to each student through a direct link to the project page, the transition could be made from any device available to the participants (smartphone, tablet, and laptop). The time for completion was limited to one academic hour, since the study implemented short and screening versions of the scales.

Statistical methods for bias control, such as weighting adjustments, were not used in this study. Regarding the minimum sample size, we did not perform a statistical power analysis, but were guided by the rule of “20 observations per measured variable/item,” which in our case (14 items) gave a minimum number of observations—280.

This allowed to obtain responses from 856 students, 229 of which were discarded due to incompletion. The final sample consisted of 621 students majoring in social sciences (35.10%) and STEM (64.90%). Mean age—19.09 ± 1.10; 47.02%—young women; 28.34%—freshmen, 55.52%—sophomore, 14.33%—junior and 0.81%—senior.

2.2 Instruments

1. A Russian “Subjective and Objective Uncertainty Stress—SOUS-14” scale (Morosanova et al., 2024). The SOUS-14 was developed based on the analysis of the existing life stress and uncertainty scales from T. Yang’s “The Student Daily Stress Questionnaire” (Yang et al., 2019) and perceived stress questionnaires. The initial pool of statements was formed on the basis of the existing Russian translation of the SDSQ (Banshchikova et al., 2023) and the Perceived Stress Scale adapted in Russian (Zolotareva, 2023). Four Russian researchers (PhD in Psychology) with experience in the field of stress psychology assessed the face and content validity of the initial set of statements. In addition, the items were checked by a philologist for compliance with Russian language norms. The scale was translated into English by a bilingual specialist with a degree in philology and psychology.

The SOUS-14 consists of 14 items related to situations that can cause stress reactions (ω in the initial validation study = 0.887): 7 of them for subjective uncertainty stress (initial ω = 0.832), and another 7—for the objective uncertainty stress (initial ω = 0.833). The respondents are asked to rate the degree of perceived stress in described situations on a 4-point scale where 1 is “no stress” and 4 is “excessive stress.” The integrative scale assesses the general level of uncertainty stress by summing up the scores obtained on the two scales: high score on this scale stands for severe uncertainty stress, and low score stands for absence of stress. The item examples include: “Отсутствие поддержки от членов семьи /Lack of support from family members” for subjective uncertainty stress, and “Климатические изменения и природные катаклизмы/Climate change and natural disasters” for objective uncertainty stress.

The following methods were used to compare SOUS-14 construct validity in university students with the previously obtained data (Morosanova et al., 2024):

-

V. I. Morosanova’s “Self-Regulation Profile Questionnaire—SRPQM” (Morosanova and Kondratyuk, 2020). The SRPQM is based on the resource approach to conscious self-regulation (SR) by Morosanova (2021). Within this approach, SR is considered a meta-resource for achieving life goals that ensures coordinated interaction of all individual resources (motivation, temperament, emotional processes, etc.). The instrument assesses the general ability for conscious self-regulation and its components, consistently manifested in various types of the human voluntary activity and life situations, i.e., the regulatory resources of a person for achieving their goals. The questionnaire consists of 28 items and 7 subscales: “Planning” (PL), “Modeling” (M), “Programming” (PR), “Results evaluation” (RE), “Flexibility” (F), “Independence” (I), “Reliability” (R) as well as the integrative scale “General Level of Self-Regulation” (GLSR) calculated as the sum of scores on all scales. The respondents are asked to rate their agreement with the statements about their regulatory features on a 5-point scale where 1 is “wrong” and 5 is “right.”

-

“Perceived Stress Scale, PSS-10” (Cohen et al., 1983, Russian adaptation by Zolotareva, 2023) consisted of 10 items and 2 subscales “Distress” and “Coping” as well as an integrative scale of the general level of perceived stress (sum of points). The respondents are asked to rate how often they felt psychological discomfort and their coping abilities during last month on a 5-point scale where 1 is “never” and 5 is “often.”

Socio-demographic data, such as income level and living conditions were not collected in this study.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using JASP ver. 0.18.3.0. Statistical procedures included descriptive statistics, Pearson’s correlation analysis, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), McDonald’s omega and independent samples t-test. Correlation analysis, McDonald’s omega and confirmatory factor analysis (including multigroup CFA for measurement invariance analysis) were used to check for invariance of SOUS’ psychometric properties on a different sample. CFA was also used to examine the measurement invariance across gender groups. The goodness-of-fit of the models in CFA was estimated using the following fit indices: chi-square (χ2), degrees of freedom (df), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), standardized root mean square (SRMR), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Good model fit was defined by CFI ≥ 0.95, TLI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.06, SRMR ≤ 0.06. Measurement invariance was analyzed by comparing three models reflecting three types of invariances (configural, metric, and scalar) by calculating Δ CFI, Δ RMSEA, Δχ2 and Δdf (Van De Schoot et al., 2015). All types of invariances were evaluated with diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimator. Finally, independent samples t-test was performed to examine gender differences in SOUS scale scores.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and correlations for all indicators. According to the results, university students experience low to middle levels of uncertainty stress. The distribution is close to the normal for all variables (skewness and kurtosis values do not exceed 1 in absolute value). For this reason, the parametric methods of analysis were further applied. The correlation analysis demonstrated results similar to our previous work: low to moderate significant correlations between SOUS-14 scales and the levels of conscious self-regulation and perceived stress. In particular, the general level of uncertainty stress moderately positively correlated with general level of perceived stress and “Distress.” Thus, the SOUS-14 questionnaire demonstrates good indicators of construct validity on the sample of university students. The results also show weak negative correlation with general level of conscious self-regulation.

Table 1

| Indicators | M(SD) | Sk | Kr | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Subjective uncertainty stress | 13.95(4.55) | 0,35 | −0,75 | – | |||||

| 2. Objective uncertainty stress | 12.65(3.74) | 0,35 | −0,70 | 0.58*** | – | ||||

| 3. General level of uncertainty stress | 26.60(7.31) | 0,30 | −0,63 | 0.91*** | 0.86*** | – | |||

| 4. General level of self-regulation | 93.33(15.05) | 0,06 | −0,36 | −0.15*** | −0.25*** | −0.22*** | – | ||

| 5. Distress | 16.07(4.96) | −0,13 | −0,41 | 0.35*** | 0.49*** | 0.46*** | −0.38*** | – | |

| 6. General level of perceived stress | 25.25(6.70) | −0,02 | −0,42 | 0.30*** | 0.45*** | 0.41*** | −0.51*** | 0.90*** | – |

Descriptive statistics, Shapiro–Wilk test and correlations for all indicators (n = 621).

**p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Sk, Skewness; Kr, Kurtosis.

3.2 Confirmatory factor analysis and internal consistency

According to our previous work, we tested for only one model: with two first-order factors and one second-order factor (subjective and objective uncertainty stress scales and general uncertainty stress scale). Since the data demonstrate a low deviation from normality, and there was a fairly large sample, the unweighted least squares method was used to assess the model fit. The factor loading threshold was 0.4.

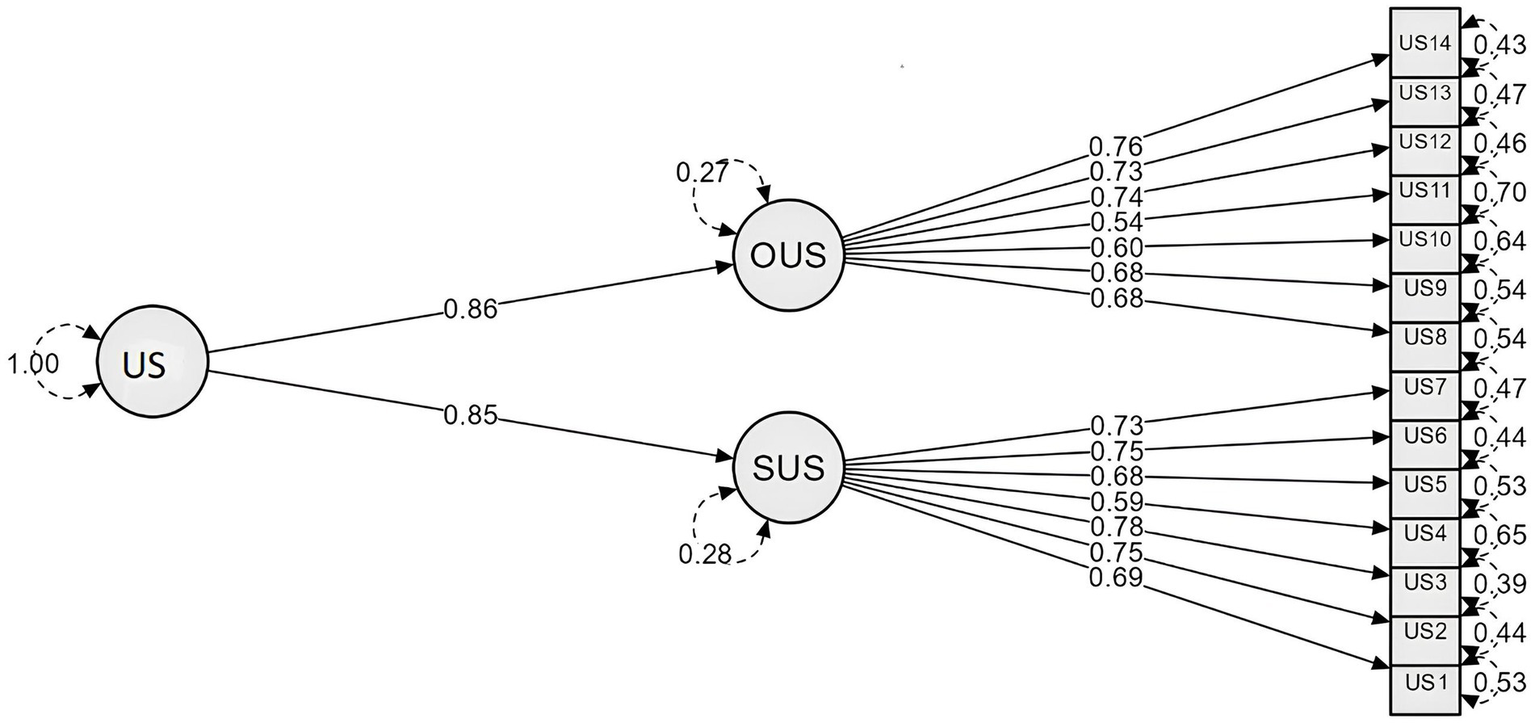

According to the data obtained, the model showed good fit indices: χ2 = 254.64, df = 75, CFI = 0.982, TLI = 0.971, RMSEA = 0.062, SRMR = 0.063. The fit indices of this model are not very different from the final model verified in our previous study: Δ CFI = 0.006; Δ TLI = 0.015; Δ RMSEA = 0.006; Δ SRMR = 0.005 (Morosanova et al., 2024). The range of factor loading coefficients in current CFA model were from 0.54 to 0.78. Figure 1 shows the factor loadings of the items on the scales as well as the contribution of the common factor to explaining the covariance between the first-order latent factors.

Figure 1

SOUS-14 CFA model.

McDonald’s Omega coefficient was calculated to evaluate internal consistency of SOUS-14 scales. According to the obtained results, all three scales demonstrate high internal consistency in university students. For subjective uncertainty stress: ω = 0.838; for objective uncertainty stress: ω = 0.816; for the general level of uncertainty stress: ω = 0.878.

3.3 Gender differences and measurement invariance across genders

First, we examined measurement invariance across genders to assess the applicability of SOUS-14 in male and female groups. Since in this type of analysis we compared nested models in smaller groups (n = 292 for male and n = 329 for female), for multigroup CFA we chose diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimator. Initially we tested the configural invariance, i.e., assessed our model for each gender group. Next, we analyzed metric invariance, i.e., tested if the factor loadings were equal across gender groups (Van De Schoot et al., 2015). Finally, we assessed scalar invariance by constraining factor loadings and intercepts to be equal. Table 2 shows the results of baseline and difference tests of three models corresponding to each type of invariance. The results revealed that all baseline models showed acceptable fit indices (CFI ≥ 0.95; RMSEA ≤ 0.06). Difference test between configural invariance model and metric invariance model showed no significant differences both in the Δχ2 (p = 0.545) and in fit indices (ΔCFI = 0.001; ΔRMSEA = 0.002). Thus, our data shows the invariance of factor loadings between gender groups. Difference test between metric invariance model and scalar invariance model revealed significant differences in the Δχ2 (p < 0.001), indicating that null hypothesis about equal loadings and intercepts should be rejected. However, otherwise the model for scalar invariance showed good fit to the data (ΔCFI = 0.002; ΔRMSEA = 0.000). Since informational criteria are considered superior to Δχ2 due to their independence to sample size (Meade et al., 2008), we made the final decision about the hypothesis based on ΔCFI and ΔRMSEA. According to observed changes in fit indices, our data shows scalar invariance in gender groups. Thus, the SOUS-14 scale is applicable for measuring gender differences in uncertainty stress.

Table 2

| Model | CFI | RMSEA | Baseline test | Difference test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | p | Δ CFI | Δ RMSEA | Δχ2 | Δdf | p | |||

| Configural invariance | 0.982 | 0.065 | 343.39 | 150 | <0.001 | |||||

| Metric invariance | 0.981 | 0.063 | 363.36 | 163 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 19.97 | 13 | 0.545 |

| Scalar invariance | 0.979 | 0.063 | 415.93 | 188 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 52.57 | 25 | 0.019 |

Model fit indices for measurement invariance across gender groups.

Next, we ran independent samples t-test to examine gender differences between SOUS-14 values. Table 3 shows the test results: female students demonstrated significantly higher subjective, objective and general uncertainty stress than male students. The effect size was medium for all variables (Cohen’s d ϵ [0.5–0.6]).

Table 3

| SOUS scales | Female (N = 292) | Male (N = 329) | Welch t | Cohen’s d [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(SD) | M(SD) | |||

| Subjective uncertainty stress | 15.16 (4.77) | 12.87 (4.05) | 6,42*** | 0.519 [0.358; 0.679] |

| Objective uncertainty stress | 13.95 (3.71) | 11.50 (3.39) | 8,55*** | 0.689 [0.526; 0.851] |

| General level of uncertainty stress | 29.11 (7.49) | 24.37 (6.51) | 8,37*** | 0.676 [0.513; 0.838] |

Gender differences for SUS, OUS and US total scores.

Effect size is given by the Cohen’s d; ***p < 0.001. Since Brown-Forsythe test suggested violation of the equal variance assumption, Welch t-test was applied.

4 Discussion

The study examined and reported the psychometric characteristics of SOUS-14 scale among university students in Russia. It also assessed measurement invariance across gender groups and gender differences in uncertainty stress in male and female students.

First, our results confirmed the validity of SOUS-14 in university students. Positive moderate correlations of the SOUS-14 scales with general level of perceived stress and distress level correspond both with the data on the relationship between uncertainty and perceived stress (Wu et al., 2021; Reizer et al., 2021) and our previous findings on college students (Morosanova et al., 2024). Moderate size of correlation coefficients confirms that uncertainty stress and perceived stress are conceptually close, but distinct constructs. Thus, SOUS-14 might supplement data obtained with PSS-10 with a detailed information about the severity of different types of uncertainty stress.

Interestingly, subjective uncertainty stress showed weaker connections with perceived stress in university students compared to college students (Morosanova et al., 2024). Note, that these results still do not fully explain differences in uncertainty stress between university and college students, particularly whether it is due to specifics of these educational tracks in Russia. Regional specifics might also explain these differences. University students in our study were from the same geographical region, and college sample included students from different Russian regions (e.g., Far East). Resent findings by T. Yang and his colleagues support this assumption: uncertainty stress shows high geographical variation (Yang et al., 2025). This issue should be investigated further in the future studies.

Negative correlations found between the questionnaire scales and the general level of conscious self-regulation are consistent with our data on the negative association between the development of SR and stress (Morosanova, 2021; Kondratyuk and Morosanova, 2021). This is consistent with theoretical and empirical evidence for self-regulation preventing stress development and mitigating its effect on psychological well-being and academic success in adolescents and young adults (Morosanova, 2021; Barbayannis et al., 2022). Recent work on the Chinese sample also supports this finding: self-regulatory fatigue found to strengthen the relationship between intolerance to uncertainty and academic burnout (Qiang et al., 2024). Additionally, our findings suggest that self-regulation might act as a universal resource for coping with uncertainty stress. Previous studies on the Russian sample during the COVID-19 pandemic showed that successful coping with uncertainty was associated with components of conscious self-regulation (Zinchenko et al., 2020). Testing this assumption in different contexts might be one of the future research directions.

Second, the reliability analysis demonstrated high internal consistency of SOUS-14 in the sample of university students—McDonald’s Omega were above 0.8 for all scales. This is consistent with both the reliability data of original Yang’s questionnaire (Yang et al., 2019) and the internal consistency of SOUS-14 scale in college students (Morosanova et al., 2024). The confirmatory factor analysis supported the suggested second-order factor structure, proposed and validated on the college students’ sample (Morosanova et al., 2024). Thus, our questionnaire allows for measuring uncertainty stress with a high degree of reliability on different student samples.

Third, our results indicate that the model describing SOUS is not gender-biased and this instrument is applicable for studying gender differences. Thus, the study revealed that female students have significantly higher levels of both subjective and objective uncertainty stress, than male students. This finding corresponds with existing literature on gender differences in perceived stress in general (Graves et al., 2021), and the data on stress in young adult females obtained in situations of uncertainty (like COVID-19; Prowse et al., 2021; Clabaugh et al., 2021). However, our results differ from those of Yang et al.: they found no significant contribution of gender to uncertainty stress (Yang et al., 2025). Moreover, their result showed higher life stress in male students, while we found higher subjective uncertainty stress (which is conceptually close to life stress) in female students. We suggest this might be due to different methodology behind SOUS-14 and SDSQ. According to resources theories of stress underlying SOUS-14, it is the depletion (or lack of) of psychological resources that causes higher stress, not the type of stressful situation itself. Another explanation might be the above-mentioned geographical variation and cross-cultural differences. Global meta-analysis on the negative emotions during COVID-19 pandemic reported higher increase in depression, anxiety and stress in European females compared to Asian and American (Daniali et al., 2023). Still, further research is needed for more in-depth understanding of the interplay between socio-economic, geographic, and psychological factors in subjective and objective uncertainty stress gender differences.

Thus, our study demonstrated that SOUS-14 is a reliable and valid tool for measuring the uncertainty stress in both college and university students. This instrument might also be used to assess gender differences in subjective and objective uncertainty stress levels. The SOUS-14 questionnaire has potential for the practical application. It opens up new possibilities in psychological and pedagogical practice for diagnosing the sources of increase in uncertainty stress in adolescents and young adults and providing them with counseling services. Yet, the study has certain limitations, since it does not address the issue of measurement invariance between different age groups. Besides, the SOUS-14 is still applicable only to the studies on student samples (17–25 years). Further research could be aimed at validating the questionnaire on samples of other ages, i.e., adults. Developing a version of the SOUS for younger adolescents and children could also have theoretical and practical significance. In addition, the study involved only students from large cities in the Central region of Russia, which raises the question of the questionnaire validity for the students living in other regions and/or in smaller cities. Another limitation is the lack of longitudinal validation of this questionnaire. Finally, the cross-cultural validity of the instrument has not yet been assessed. Future research will consider these limitations.

Another quite promising research direction is to study the impact of various aspects of uncertainty stress on academic success, subjective well-being, personal and professional development in students.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal Scientific Center for Psychological and Multidisciplinary Research (known as Psychological Institute of the Russian Academy of Education until 2023), protocol No. 7, date of approval January 31 2024. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants or participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

YZ: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. VM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AP: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (the research project 075-15-2024-526).

Acknowledgments

All authors confirm that the following manuscript is a transparent and honest account of the reported research. This research is related to the previous study titled “Diagnostics of Stress of Subjective and Objective Uncertainty: Development and Validation of a Questionnaire” (Morosanova et al., 2024), which was based on the development of the concept of subjective and objective uncertainty stress in the Russian context and the instrument for its measurement as well as the comparison of students attending different types of educational institutions (colleges and universities) on the developed scale. The current submission is focusing on the psychometric evaluation of “Subjective and Objective Uncertainty Stress” scale on a large sample of Russian university students, the analysis of its measurement invariance, and the gender differences in levels of subjective and objective uncertainty stress. The study is following the methodology explained in the previous work “Diagnostics of Stress of Subjective and Objective Uncertainty: Development and Validation of a Questionnaire.”

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

1

Ahamed A. J. Limbu Y. B. (2024). Financial anxiety: a systematic review. Int. J. Bank Mark.42, 1666–1694. doi: 10.1108/IJBM-08-2023-0462

2

Arbona C. Fan W. Phang A. Olvera N. Dios M. (2021). Intolerance of uncertainty, anxiety, and career indecision: a mediation model. J. Career Assess.29, 699–716. doi: 10.1177/10690727211002564

3

Banshchikova T. N. Sokolovskii M. L. Tegetaeva J. R. (2023). Conscious self-regulation as resource for overcoming stress and achieving subjective well-being: ethno-regional specificity. Theoretical and Experimental Psychology, 19–42. doi: 10.24412/TEP-23-2. (In Russ.).

4

Barbayannis G. Bandari M. Zheng X. Baquerizo H. Pecor K. W. Ming X. (2022). Academic stress and mental well-being in college students: correlations, affected groups, and COVID-19. Front. Psychol.13:886344. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.886344

5

Ben Salah A. DeAngelis B. N. Al’Absi M. (2023). Uncertainty and psychological distress during COVID-19: what about protective factors?Curr. Psychol.42, 21470–21477. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03244-2

6

Brown J. K. Barringer A. Kouros C. D. Papp L. M. (2024). Examining enduring effects of COVID-19 on college students' internalizing and externalizing problems: a four-year longitudinal analysis. J. Affect. Disord.351, 551–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.01.199

7

Brown J. K. Papp L. M. (2024). COVID-19 pandemic effects on trajectories of college students' stress, coping, and sleep quality: a four-year longitudinal analysis. Stress. Health40:e3320. doi: 10.1002/smi.3320

8

Cao W. Fang Z. Hou G. Han M. Xu X. Dong J. et al . (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res.287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

9

Chernousova T. V. (2022). Strategies of responding to uncertainty as a subject of socio-psychological analysis. Psychol. Educ.4, 421–434. doi: 10.33910/2686-9527-2022-4-4-421-434

10

Clabaugh A. Duque J. F. Fields L. J. (2021). Academic stress and emotional well-being in United States college students following onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol.12:628787. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.628787

11

Clayton S. (2020). Climate anxiety: psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord.74:102263. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102263

12

Cohen S. Kamarck T. Mermelstein R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav., 385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404

13

Daniali H. Martinussen M. Flaten M. A. (2023). A global meta-analysis of depression, anxiety, and stress before and during COVID-19. Health Psychol.42, 124–138. doi: 10.1037/hea0001259

14

De Man J. Campbell L. Tabana H. Wouters E. (2021). The pandemic of online research in times of COVID-19. BMJ Open11:e043866. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043866

15

Fernández-García R. Melguizo-Ibáñez E. Zurita-Ortega F. Ubago-Jiménez J. L. (2024). Development and validation of a mental hyperactivity questionnaire for the evaluation of chronic stress in higher education. BMC Psychol.12:392. doi: 10.1186/s40359-024-01889-1

16

Graves B. S. Hall M. E. Dias-Karch C. Haischer M. H. Apter C. (2021). Gender differences in perceived stress and coping among college students. PloS one, 16:e0255634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255634

17

Greco V. Roger D. (2003). Uncertainty, stress, and health. Personal. Individ. Differ.34, 1057–1068. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00091-0

18

Hamaideh S. H. Al-Modallal H. Tanash M. A. Hamdan-Mansour A. (2022). Depression, anxiety and stress among undergraduate students during COVID-19 outbreak and" home-quarantine". Nurs. Open9, 1423–1431. doi: 10.1002/nop2.918

19

Hobfoll S. E. (2011). “Conservation of resources theory: its implication for stress, health, and resilience” in The Oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping. ed. S. Fokman (New York: Oxford University Press), 127–147.

20

Knapstad M. Sivertsen B. Knudsen A. K. Smith O. R. F. Aarø L. E. Lønning K. J. et al . (2021). Trends in self-reported psychological distress among college and university students from 2010 to 2018. Psychol. Med.51, 470–478. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719003350

21

Kondratyuk N. G. Morosanova V. I. (2021). “Self-regulation's reliability as resource of personal psychological safety under stressful conditions and uncertainty” in Psychology of self-regulation in the context of current problems of education (to the 90th anniversary of the birth of O.A. Konopkin). eds. V. I. Morosanova, Y. P. Zinchenko (Moscow: Publishing House), 156–161. In Russia

22

Kornienko D. S. Rudnova N. A. (2023). Exploring the associations between happiness, life-satisfaction, anxiety, and emotional regulation among adults during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Russia. Psychol Russia: State of the Art16, 99–113. doi: 10.11621/pir.2023.0106

23

Kriger E. E. (2014). Uncertain situations and problem situations: general and specific. Modern Problems Sci Educ2:581. (In Russ.)

24

Krishna M. S. Rajan G. (2025). “Virtual fatigue, real solutions: addressing digital fatigue and reclaiming well-being in the era of online learning for college students” in Digital pedagogy. Revolutionizing education through technology. eds. M. Banerjee, D. Dey, P. Pandey, R. Dwivedi (London: Red’shine Publication), 7–17.

25

Lazarus R. S. Folkman S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

26

Massazza A. Kienzler H. Al-Mitwalli S. Tamimi N. Giacaman R. (2023). The association between uncertainty and mental health: a scoping review of the quantitative literature. J. Ment. Health32, 480–491. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2021.2022620

27

McCarty R. J. Downing S. T. Daley M. L. McNamara J. P. Guastello A. D. (2023). Relationships between stress appraisals and intolerance of uncertainty with psychological health during early COVID-19 in the USA. Anxiety Stress Coping36, 97–109. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2022.2075855

28

Meade A. W. Johnson E. C. Braddy P. W. (2008). Power and sensitivity of alternative fit indices in tests of measurement invariance. J. Appl. Psychol.93, 568–592. doi: 10.1037/0021/-9010.93.3.568

29

Morosanova V. I. (2021). Conscious self-regulation as a meta-resource for achieving goals and solving the problems of human activity. Lomonosov Psychol J1, 4–37. doi: 10.11621/vsp.2021.01.01

30

Morosanova V. I. Kondratyuk N. G. (2020). V.I. Morosanova’s “self-regulation profile questionnaire - SRPQM 2020”. Questions Psychol.4, 155–167. (In Russ.)

31

Morosanova V. I. Potanina A. M. Pashchenko A. K. (2024). Diagnostics of stress of subjective and objective uncertainty: development and validation of a questionnaire. Russian Psycholog. J.21, 112–132. doi: 10.21702/rpj.2024.3.7

32

Muysewinkel E. Stene L. E. Van Deynse H. Vesentini L. Bilsen J. Van Overmeire R. (2024). Post-what stress? A review of methods of research on posttraumatic stress during COVID-19. J. Anxiety Disord.102:102829. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2024.102829

33

Olasina G. (2023). Using new assessment tools during and post-COVID-19. Libr. Philos. Pract.7902. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/7902 (Accessed August 30, 2025).

34

Othman N. Ahmad F. El Morr C. Ritvo P. (2019). Perceived impact of contextual determinants on depression, anxiety and stress: a survey with university students. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Syst.13, 17–19. doi: 10.1186/s13033-019-0275-x

35

Peng S. Yang X. Y. Yang T. Zhang W. Cottrell R. R. (2021). Uncertainty stress and its impact on disease fear and prevention behavior during the COVID-19 epidemic in China: a panel study. Am. J. Health Behav.45, 334–341. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.45.2.12

36

Peters A. McEwen B. S. Friston K. (2017). Uncertainty and stress: why it causes diseases and how it is mastered by the brain. Prog. Neurobiol.156, 164–188. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2017.05.004

37

Phillimore J. Cheung S. Y. (2021). The violence of uncertainty: empirical evidence on how asylum waiting time undermines refugee health. Soc. Sci. Med.282:114154. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114154

38

Prowse R. Sherratt F. Abizaid A. Gabrys R. L. Hellemans K. G. Patterson Z. R. et al . (2021). Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic: examining gender differences in stress and mental health among university students. Front. Psychol.12:650759. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.650759

39

Qiang J. He X. Xia Z. Huang J. , and XuC. (2024). The association between intolerance of uncertainty and academic burnout among university students: the role of self-regulatory fatigue and self-compassion. Frontiers in Public Health, 12:1441465. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1441465

40

Rao H. Gupta M. Agarwal P. Bhatia S. Bhardwaj R. (2024). Mental health issues assessment using tools during COVID-19 pandemic. Innov. Syst. Softw. Eng.20, 393–404. doi: 10.1007/s11334-022-00510-1

41

Reizer A. Geffen L. Koslowsky M. (2021). Life under the COVID-19 lockdown: on the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and psychological distress. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy13, 432–437. doi: 10.1037/tra0001012

42

Rodriguez-Besteiro S. Tornero-Aguilera J. F. Fernández-Lucas J. Clemente-Suárez V. J. (2021). Gender differences in the COVID-19 pandemic risk perception, psychology, and behaviors of Spanish university students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health18:3908. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18083908

43

Santomauro D. F. Herrera A. M. M. Shadid J. Zheng P. Ashbaugh C. Pigott D. M. et al . (2021). Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet398, 1700–1712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7

44

Satici B. Saricali M. Satici S. A. Griffiths M. D. (2022). Intolerance of uncertainty and mental wellbeing: serial mediation by rumination and fear of COVID-19. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Addict.20, 2731–2742. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00305-0

45

Sischka P. E. Grübbel L. Reisinger C. V. Neufang K. M. Schmidt A. F. (2024). On the dimensionality, suitability of sum/mean scores, and cross-country measurement invariance of the perceived stress scale 10 (PSS-10)—evidence from 41 countries. Int. J. Stress. Manag.31, 375–391. doi: 10.1037/str0000330

46

Solntseva G. N. Smolyan G. L. (2009). Decision-making in situations of uncertainty and risk (psychological aspect). Proceedings of the Institute of System Analysis of the Russian Acad Sci41, 266–280. (In Russ.)

47

Stankovska G. Memedi I. Dimitrovski D. (2020). Coronavirus COVID-19 disease, mental health and psychosocial support. Society Register4, 33–48. doi: 10.14746/sr.2020.4.2.03

48

Sultanova A. N. Tagil'tseva E. V. Stankevich A. S. (2021). Psychological determinants of successful adaptation of migrant students. Lomonosov Psychol J3, 129–147. doi: 10.11621/vsp.2021.03.07

49

Sweeny K. Rankin K. Cheng X. Hou L. Long F. Meng Y. et al . (2020). Flow in the time of COVID-19: findings from China. PLoS One15:e0242043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242043

50

Van De Schoot R. Schmidt P. De Beuckelaer A. Lek K. Zondervan-Zwijnenburg M. (2015). Measurement invariance. Front. Psychol.6:1064. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01064

51

Wise T. Zbozinek T. D. Charpentier C. J. Michelini G. Hagan C. C. Mobbs D. (2023). Computationally-defined markers of uncertainty aversion predict emotional responses during a global pandemic. Emotion23, 722–736. doi: 10.1037/emo0001088

52

Wu D. Yang T. Hall D. L. Jiao G. Huang L. Jiao C. (2021). COVID-19 uncertainty and sleep: the roles of perceived stress and intolerance of uncertainty during the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak. BMC Psychiatry21:306. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03310-2

53

Wu M. J. Zhao K. Fils-Aime F. (2022). Response rates of online surveys in published research: a meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep.7:100206. doi: 10.1016/j.chbr.2022.100206

54

Yang T. Barnett R. Fan Y. Li L. (2019). The effect of urban green space on uncertainty stress and life stress: a nationwide study of university students in China. Health Place59:102199. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102199

55

Yang T. Peng S. Oliffe J. L. Zhang W. (2025). Geographical disparities of uncertainty stress and life stress among university students: a study across all provinces in mainland China. Stress. Health41:e70009. doi: 10.1002/smi.70009

56

Zarowski B. Giokaris D. Green O. (2024). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on university students' mental health: a literature review. Cureus16:e54032. doi: 10.7759/cureus.54032

57

Zhai Y. Du X. (2024). Trends in diagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder in us college students, 2017-2022. JAMA Netw. Open7:e2413874. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.13874

58

Zinchenko Y. P. (2021). Psychological support during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moscow: Moscow Univ. Press(In Rus.).

59

Zinchenko Y. P. Morosanova V. I. Kondratyuk N. G. Fomina T. G. (2020). Conscious self-regulation and self-organization of life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Russia: State of the Art13, 168–182. doi: 10.11621/pir.2020.0411

60

Zolotareva A. A. (2023). Psychometric properties of the Russian version of the perceived stress scale (PSS-4, 10, 14). Clin. Psychol. Spec. Educ.12, 18–42. doi: 10.17759/cpse.2023120102

Appendix

Instructions, statements, and key to the “Subjective and Objective Uncertainty Stress—SOUS-14”

Instructions:

You will be given some statements related to situations that can cause negative stress reactions. Please, evaluate the extent of possible stress in each of these situations on a scale: 1, no stress; 2, slight stress; 3, significant stress; 4, excessive stress.

Items:

-

Difficulties in studies

-

Unsatisfying relationships with peers

-

Conflicting relationships with teachers

-

Dissatisfaction with romantic relationships

-

Regular financial difficulties

-

Lack of support from family members

-

Threats to life and health

-

A rapidly changing world

-

Flow of negative news

-

In today’s world it is difficult to identify what is the truth and what is the lie

-

Climate change and natural disasters

-

Difficulties in projecting professional plans under conditions of uncertainty

-

It is difficult to understand who are the enemies and who are the friends

-

Growing uncertainty about the future

Key. The scales indicators are calculated by summing up the scores on the following items: subjective uncertainty stress—items 1–7; objective uncertainty stress—items 8–14. The indicator of the integral scale of the general level of uncertainty stress is calculated as the sum of the values on both scales of the questionnaire.

Summary

Keywords

uncertainty stress, subjective uncertainty stress, objective uncertainty stress, scale validation, measurement invariance, university students

Citation

Zinchenko YP, Morosanova VI and Potanina AM (2025) The Russian subjective and objective uncertainty stress (SOUS-14) scale: factor validity, internal reliability, and measurement invariance in university student sample. Front. Psychol. 16:1583172. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1583172

Received

13 March 2025

Accepted

30 September 2025

Published

30 October 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Ghaleb Hamad Alnahdi, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia

Reviewed by

Lucrezia Perrella, University of Sassari, Italy

Zihniye Okray, European University of Lefka, Türkiye

Tzu-Yang Chao, National Central University, Taiwan

Jun Li, Hainan Vocational University of Science and Technology, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zinchenko, Morosanovа and Potaninа.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Varvara I. Morosanova, morosanova@mail.ru

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.