- 1School of Economics & Management, Southeast University, Nanjing, China

- 2School of Labor and Human Resources, Renmin University of China, Beijing, China

- 3School of Business, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China

In recent years, the positive influences of leadership on subordinate performance have been extensively studied. However, whether high-performing subordinates can, in turn, change the way leaders lead them remains underexplored. Based on social exchange theory, this research examines the mediating role of subordinate contribution in the relationship between subordinate performance and leader ostracism and recognition, as well as the moderating role of the leader’s outcome dependence on subordinate. Results from a multi-wave and multi-source field survey comprising 245 subordinates and 68 leaders indicate that subordinate performance increases subordinate contribution, which in turn, reduces leader ostracism and promotes leader recognition. Moreover, outcome dependence on subordinate reinforces the positive impact of subordinate performance on subordinate contribution, and the mediating effect of subordinate contribution. These findings not only provide a theoretical explanation of how and under what conditions subordinate performance can be welcomed by the leader, but also offer valuable insights for organizations to mitigate negative leader responses and foster positive ones.

1 Introduction

Employee performance serves as the cornerstone of organizational success, acting as the vital bridge between strategic objectives and operational achievement (Decramer et al., 2013; Sarwar and Muhammad, 2021; Ni et al., 2022). In the era of VUCA (i.e., volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous), where businesses operate in a highly competitive and rapidly changing environment (Bennett and Lemoine, 2014; Garavan et al., 2024), the ability to sustain high employee performance has evolved from a competitive advantage to a survival imperative. It directly impacts productivity, innovation, customer satisfaction, and ultimately, the company’s profitability (Gong et al., 2009; Call and Ployhart, 2021). Consequently, extant studies have predominantly focused on identifying factors that can improve employee performance, with leadership consistently considered an important category of antecedents (e.g., Tsai et al., 2009; Wadei et al., 2023; Umrani et al., 2024).

However, can employees who achieve high performance, in turn, alter their leaders’ behavioral patterns? Scholars have conducted preliminary explorations of this question. For example, subordinate performance has been found to decrease negative leadership behaviors (e.g., abusive supervision, Tariq and Weng, 2018; Lyubykh et al., 2022) and promote positive leadership behaviors (e.g., empowering leadership, Cao et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). Nevertheless, examining these two effects in isolation fails to fully capture how high-performing subordinates may receive preferential treatment from leaders, necessitating an integrated investigation. Given that subordinates generally seek to avoid leader ostracism (Fiset and Boies, 2018; Azeem et al., 2024) and desire leader recognition (Wayne et al., 2002; Malek et al., 2020), this study investigates whether subordinate performance can simultaneously reduce leader ostracism and increase leader recognition.

To explain how subordinate performance influences leadership behavior, existing studies have drawn on theories like social comparison theory (Tariq et al., 2021), affective events theory (Li et al., 2024) and self-control framework (Liang et al., 2016). However, these studies have principally focused on the mediating role of leader affect in the relationship between subordinate performance and leadership behavior, while neglecting the crucial role of leader cognition. Social exchange theory posits that individual interactions are guided by the principle of reciprocity (Emerson, 1976; Cropanzano et al., 2017; Akkermans et al., 2024), individuals weigh potential outcomes before deciding whether to engage in specific relationships or behaviors. As mentioned earlier, subordinate performance exerts a positive effect on the individual, the team, and the organization (Gong et al., 2009; Call and Ployhart, 2021), directly or indirectly supporting leaders’ work. Consequently, leaders tend to foster good relationships with subordinates rather than ostracize them and may reciprocate by recognizing subordinates’ contributions. Based on the above line of reasoning, we suggest that subordinate performance may reduce ostracism and enhance recognition through leader-perceived subordinate contribution.

Furthermore, leader personal factors (e.g., leader social orientation, Khan et al., 2018; Tariq et al., 2021) and leader-subordinate dyadic factors (e.g., leader-subordinate guanxi, Duarte et al., 1994; Cao et al., 2022) are acknowledged as two significant types of boundary conditions in the process by which subordinate performance influences the leader. Indeed, the nature of leaders’ tasks affects their interpretations of subordinates’ performance (Xu and Li, 2024). In team tasks requiring a close collaboration between leaders and subordinates, subordinates’ proficiency in completing assigned tasks can influence goal attainment. Therefore, it is necessary to integrate the roles of both parties into the process of how subordinate performance influences leadership. A potential factor is the leader’s outcome dependence on subordinate, defined as the extent to which subordinates’ efforts impact leaders’ work outcomes (Walter et al., 2015). Specifically, when outcome dependence on subordinate is high, the fulfillment of the leader’s goals is tied to the competence and dedication of the subordinate (de Jong et al., 2007). In this case, the contribution of subordinate performance to the leader is magnified, and its impact on leader ostracism and recognition is subsequently enhanced. Therefore, we maintain that outcome dependence on subordinate may play a moderating role in the above relationship.

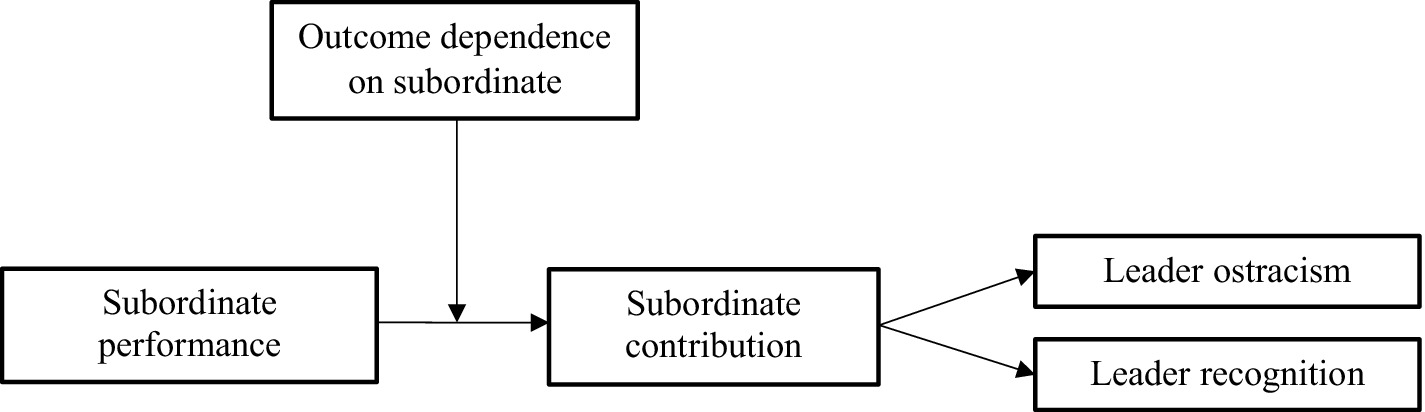

Overall, based on social exchange theory, we develop a research model as shown in Figure 1. By exploring the mediating role of subordinate contribution between subordinate performance, leader ostracism and recognition, as well as the moderating role of outcome dependence on subordinate, there are three main theoretical contributions expected from this study. First, we integrate the inhibitory or promotional effects of subordinate performance on leadership behaviors, which contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the positive influences of subordinate performance on leadership. Second, we investigate the leader’s cognitive mechanisms between subordinate performance and leadership behavior based on social exchange theory, offering a new perspective to explain how subordinate performance impacts leadership behavior. Finally, we incorporate the moderating role of leader personal factors and leader-subordinate dyadic factors in the process of subordinate performance influencing leadership, which facilitates a deeper understanding of the conditions under which subordinate performance can be welcomed by the leader.

2 Theoretical background and hypotheses

2.1 Subordinate performance and contribution

As one of the groups with significant responsibility for the development of the organization, leaders tend to evaluate subordinate performance positively, a factor that can facilitate the efficient functioning, goal accomplishment and competitive advantage of the organization (Yang and Wei, 2017; Hulshof et al., 2020; Van Scotter and Van Scotter, 2021). For example, leaders may believe that high performing subordinates are high in conscientiousness (Lyubykh et al., 2022), beneficial (Mawritz et al., 2017) and trustworthy (Cao et al., 2022). Similarly, we argue that subordinate performance can increase the contribution to the leader, reflecting a subordinate’s assistance to a leader in accomplishing team goals (Spreitzer, 1995). It is important to distinguish these two constructs: subordinate performance refers to behaviors or outcomes mandated by job descriptions (Williams and Anderson, 1991), whereas completing basic duties does not necessarily translate into contributions to the leader’s work. For instance, in an organization that promotes innovation, subordinates who strictly adhere to established procedures may fail to generate incremental value for their leaders.

Subordinate performance can lead to higher contribution for the following reasons. High-performing subordinates tend to be better able to complete work tasks, solve problems, innovate, and move projects forward (Chun et al., 2018; Alaybek et al., 2022), all of which are important indicators for leaders to assess their subordinates’ contributions. In addition, such subordinates usually have more interactions with their leaders (Lam et al., 2007; Rivera et al., 2024), and accordingly, leaders are more likely to notice their accomplishments. Since leaders typically evaluate the contributions of subordinates based on their performance (Breuer et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2023), when a subordinate demonstrates efficient and high-quality work results, it not only facilitates the achievement of team goals but also adds value to the organization, then the leader may perceive the subordinate as a greater contributor. Thus, the following hypothesis is formulated.

H1. Subordinate performance is positively related to contribution.

2.2 Subordinate contribution and leader ostracism

In general, leaders do not display negative leadership behaviors toward subordinates who have made valuable contributions. For instance, subordinates who are good at their jobs are not prone to passive leadership (Krasikova et al., 2013), and more specifically, help from subordinates can reduce a leader’s laissez-faire leadership behavior (Lee et al., 2024). Besides, proactive subordinates are less likely to be derailed during their career development (Crossley et al., 2023). Following this logic, we assume that subordinate contributions decrease leader ostracism, defined as leaders’ exclusion or marginalization of subordinates from decision-making processes, group activities, or social interactions within an organization (Jahanzeb et al., 2018; Hsiao et al., 2024).

Within an organization, leaders often welcome members who exert a positive influence, and enhance efficiency and effectiveness (Crouch and Yetton, 1988; Zhang et al., 2024). When subordinates make substantial contributions through active work attitudes, efficient task execution, and innovative thinking or specialized skills, they alleviate leaders’ workloads and assist leaders in better achieving their goals (Tang et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2020). This, in turn, indirectly improves leaders’ management effectiveness (Brewer et al., 1994; Vasquez et al., 2021). Therefore, such subordinates are not only less likely to experience leader ostracism, but also more likely to become key members whom leaders rely on and value. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis.

H2a. Subordinate contribution is negatively related to leader ostracism.

2.3 Subordinate contribution and leader recognition

In a similar vein, subordinates who make outstanding contributions tend to be treated well by their leaders. For example, leaders exhibit greater amiability toward subordinates with frequent task-related interactions (Crouch and Yetton, 1988). Subordinates with effective communication skills are more likely to be included in leaders’ affairs (Abson and Schofield, 2022). Moreover, leaders are inclined to seek advice from subordinates when perceiving alignment with their goals (Liu and Dong, 2020). Correspondingly, we believe that subordinate contribution can facilitate leader recognition, leaders’ acknowledgment or appreciation of subordinates’ work, capabilities, and attitudes (Wayne et al., 2002; Malek et al., 2020).

Generally, leaders are concerned with their own outcomes and benefits (Porter et al., 2016; Mai et al., 2022). When subordinates’ work can improve efficiency, enhance customer satisfaction, advance the success of projects and bring economic gains (Lichtenthaler and Fischbach, 2018; Huang et al., 2024), such contributions are naturally noticed and appreciated by leaders. To acknowledge and motivate subordinates (Miao et al., 2013; Zhang and Min, 2021), leaders may recognize their efforts through verbal praise or other means. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H2b. Subordinate contribution is positively related to leader recognition.

2.4 The mediating role of subordinate contribution

Combining hypotheses 1 and 2a/2b, subordinate contribution may mediate the relationship between subordinate performance and leader ostracism and recognition. Social exchange theory states that there are mutually beneficial exchange relationships between individuals (Emerson, 1976; Cropanzano et al., 2017; Akkermans et al., 2024). When one person provides a benefit to another, the recipient experiences a psychological obligation to reciprocate. In organizational context, subordinates with high performance deliver positive work outcomes and potential organizational rewards to leaders. For results-driven leaders, such subordinates are indispensable to the attainment of their goals; thus, leaders tend to maintain and strengthen the relationships with them rather than ostracize them. Furthermore, leaders would reciprocate by acknowledging subordinates’ contributions. Taken together, we formulate the following hypotheses.

H3a. Subordinate contribution mediates the relationship between subordinate performance and leader ostracism.

H3b. Subordinate contribution mediates the relationship between subordinate performance and leader recognition.

2.5 The moderating role of outcome dependence on subordinate

Further, previous research suggests that leaders’ interpretations of subordinate performance are not fixed, but can be moderated by leader personal factors (e.g., leader social orientation, Khan et al., 2018; Tariq et al., 2021) and leader-subordinate dyadic factors (e.g., leader-subordinate guanxi, Duarte et al., 1994; Cao et al., 2022). However, few studies have integrated these two types of boundary conditions. According to social exchange theory (Emerson, 1976), the development of interpersonal relationships or engagement in specific behaviors is contingent upon the presence of tangible benefits. For leaders, the significance of subordinate performance to them changes with their degree of reliance on subordinates. To address this gap, we introduce outcome dependence on subordinate (i.e., the extent to which a leader’ performance is reliant on the action and outcome of a subordinate, Walter et al., 2015; Xu and Li, 2024), and explore its moderating role in the relationship between subordinate performance and contribution.

When leaders’ outcome dependence on subordinates is high, they heavily rely on subordinates to achieve desired results and goals (Shi et al., 2013; Xu and Li, 2024). High-quality subordinate performance leads leaders to focus intently on outcomes and perceive such subordinates as critical contributors to goal attainment. Conversely, low-performing subordinates often fail to complete tasks successfully. When leaders heavily depend on these subordinates, they are more likely to notice employees’ shortcomings and ultimately perceive them as poor contributors to team goals. Thus, the positive relationship between subordinate performance and leader-perceived contribution is stronger when leaders’ outcome dependence on subordinate is high.

When outcome dependence on subordinate is low, subordinates play a less critical role in leaders’ goal attainment. On one hand, even if subordinates excel at their tasks, leaders may not strongly recognize the outstanding performance of the subordinate (Moss and Martinko, 1998; Li et al., 2024) because of the weak connection between the leader and the subordinate. On the other hand, although low-performing subordinates may cause problems like delayed task or substandard quality, leaders who do not depend too much on subordinates are unlikely to perceive these problems as threatening team goal achievement. Therefore, the positive relationship between subordinate performance and leader-perceived contribution is weaker when leaders’ outcome dependence on subordinates is low. Taken together, the following hypothesis is developed.

H4. Outcome dependence on subordinate strengthens the relationship between subordinate performance and contribution.

2.6 Moderated mediation

Synthesizing hypotheses 3a, 3b, and 4, it is possible that outcome dependence on subordinate moderates the mediating role of subordinate contribution in the relationship between subordinate performance and leader ostracism and recognition. In the case of high outcome dependence on subordinate, subordinate performance makes a significant contribution and becomes indispensable to the leader’s realization of team goals. Consequently, leaders are less likely to ostracize such subordinate. In addition, leaders are more likely to grant recognition to subordinates for prominent contributions. On the contrary, when outcome dependence on subordinate is low, the impact of subordinate performance on the leader’s objectives and outcomes is minimal. As such, leaders may perceive little need to ostracize under-performing subordinates or benefit from recognizing high-performing ones. In summary, we develop the following hypotheses.

H5a. Outcome dependence on subordinate strengthens the mediating effect of subordinate contribution on the relationship between subordinate performance and leader ostracism.

H5b. Outcome dependence on subordinate strengthens the mediating effect of subordinate contribution on the relationship between subordinate performance and leader recognition.

3 Method

3.1 Sample and procedure

In this study, subordinates and their leaders from a company in a southeastern city of China were invited to participate in a questionnaire survey. Before the study commenced, the research team explained its purpose, emphasized the voluntary nature of participation, and promised that their personal information would be kept strictly confidential and that the data would be used only for academic analysis. Based on the practice of previous studies (Rank et al., 2009; Cai et al., 2023), data collection was divided into two periods, with a one-month interval, aiming to improve the causality between variables and mitigate common method variance.

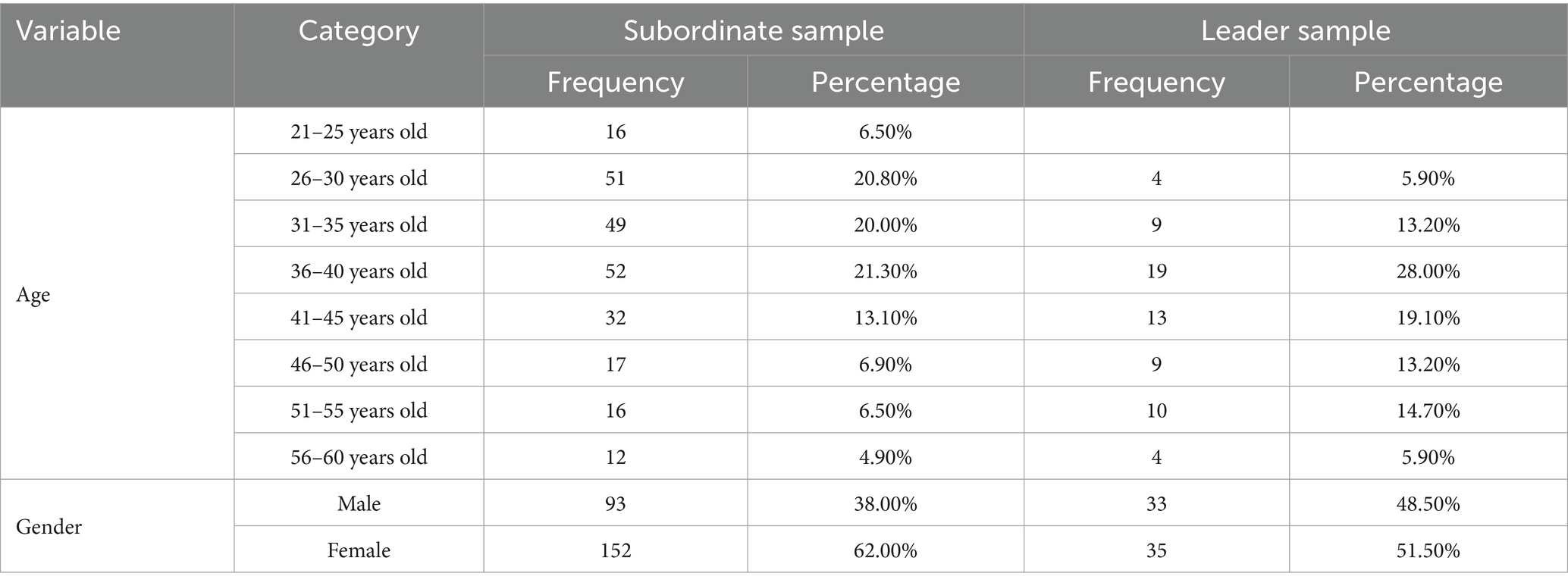

In the first session, data of subordinate performance and outcome dependence on subordinate were collected, both filled out by leaders toward each subordinate, and demographic information was collected for subordinates and leaders. With the help of human resources manager, participants’ questionnaires were numbered and then sent to 290 subordinates and 72 leaders. After eliminating invalid ones with incomplete or mismatched responses, 278 subordinate data and 71 leader data were reserved. In the second period, leaders rated subordinates’ contribution one by one, and subordinates were asked to evaluate leaders’ ostracism and recognition on them. After sorting, the valid data returned this time included 245 subordinates and 68 leaders. The overall effective recovery rate of the two surveys was 84.48% for subordinate data and 94.44% for leader data. Table 1 described the demographic information of subordinates and leaders. For the subordinates, their average age was 37.24 years old and 38.00% of them were male. Among the sample of leaders, the average age was 42.41 years old and men accounted for 48.50%.

3.2 Measures

All the scales used in the study were originally developed in English and the standard procedure of “translation and back-translation” was carried out. The 7-point Likert scale was adopted for all main variables.

3.2.1 Subordinate performance

To measure subordinate performance, three items (1 = “far below average”; 7 = “far above average”) were selected from Williams and Anderson’s (1991) seven-item scale and supplemented with the subject. An example is “This subordinate meets formal performance requirements of the job” (α = 0.969).

3.2.2 Subordinate contribution

We adapted the wording of the three items (1 = “strongly disagree”; 7 = “strongly agree”) developed by Spreitzer (1995) to make them applicable to leaders evaluating the contributions of subordinates, with a sample “This subordinate makes me feel self-assured about my capabilities to perform my work activities” (α = 0.976).

3.2.3 Leader ostracism

We adapted the wording of the six items (1 = “do not remember”; 7 = “often”) developed by O’Reilly et al. (2015) to make them applicable to subordinates evaluating leader ostracism. An example is “My leader excludes me from influential roles or committee assignments” (α = 0.980).

3.2.4 Leader recognition

Similar to leader ostracism, we adapted the wording of the three items (1 = “strongly disagree”; 7 = “strongly agree”) developed by Wayne et al. (2002) to measure leader recognition, with a sample “My leader recognizes me” (α = 0.828).

3.2.5 Outcome dependence on subordinate

To measure outcome dependence on subordinate, we converted the two items (1 = “strongly disagree”; 7 = “strongly agree”) developed by Wee et al. (2017) into declarative sentences. An example is “I am dependent on this subordinate for materials, means, information, etc.” (α = 0.800).

3.2.6 Control variables

Referring to previous studies (e.g., Ferris et al., 2019; Jahanzeb et al., 2021), we controlled for subordinates’ and leaders’ age (1 = “21–25 years old”; 2 = “26–30 years old”; 3 = “31–35 years old”; 4 = “36–40 years old”; 5 = “41–45 years old”; 6 = “46–50 years old”; 7 = “51–55 years old”; 8 = “56–60 years old”) and gender (1 = “male”; 2 = “female”).

4 Results

4.1 Confirmatory factor analyses

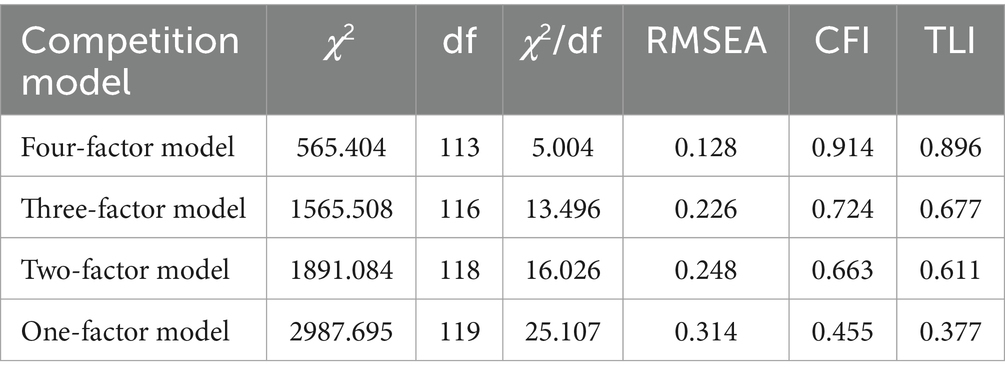

The hypothetical five-factor model was tested, and its main indexes were: χ2 = 145.604, df = 109, χ2/df = 1.336, RMSEA = 0.037, CFI = 0.993, TLI = 0.991, showing a good fit to the data. According to the features of the variables, we set up four competition models, namely four-factor model (subordinate contribution and outcome dependence on subordinate combined), three-factor model (subordinate contribution and outcome dependence on subordinate combined; subordinate performance and leader recognition combined), two-factor model (variables except leader ostracism combined) and one-factor model (all variables combined), as shown in Table 2. Comparative analysis found that the original model fitted better, indicating that the five variables in this study had good discriminative validity.

4.2 Descriptive statistics and correlations

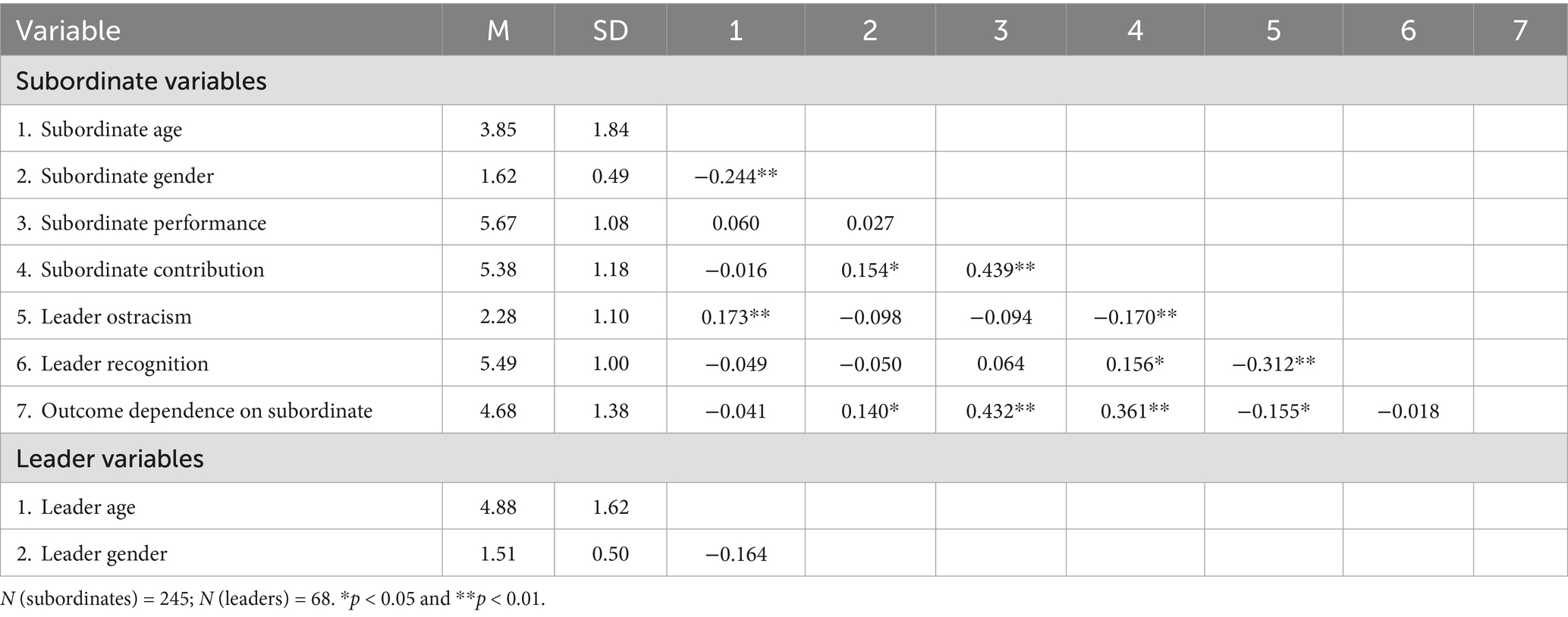

Table 3 exhibited the means, standard deviations and correlations of variables. From the table, we could see that, subordinate performance was significantly positively correlated with contribution (r = 0.439, p < 0.01). Subordinate contribution was significantly negatively related to leader ostracism (r = −0.170, p < 0.01) and positively associated with leader recognition (r = 0.156, p < 0.05). The above results preliminarily supported H1 and H2a-b.

4.3 Hypotheses testing

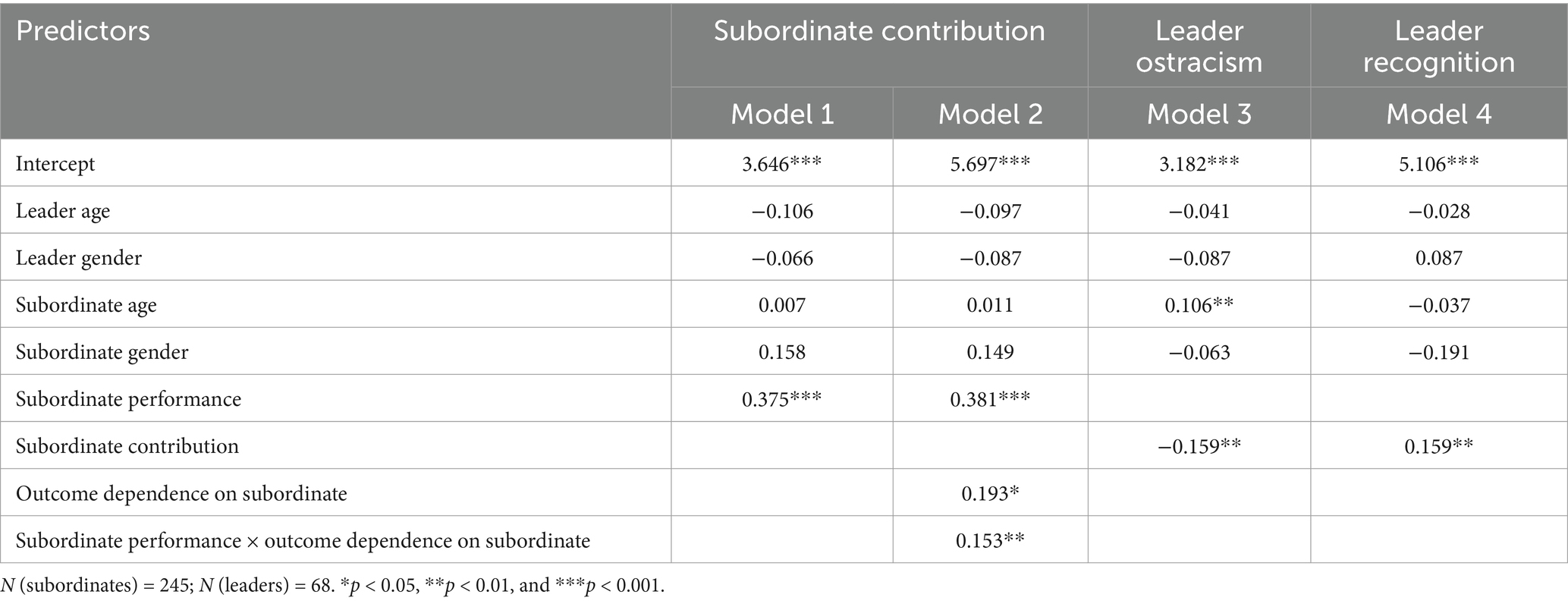

As subordinates were partially nested within leaders, we used HLM (i.e., hierarchical linear modeling) to test our hypotheses. The results of regression analyses were presented in Table 4. As shown in Model 1, subordinate performance was positively related to contribution (γ = 0.375, p < 0.001), supporting H1. Consistent with H2a-b, subordinate contribution significantly decreased leader ostracism (γ = −0.159, p < 0.01, Model 3) and increased leader recognition (γ = 0.159, p < 0.01, Model 4). To test the mediating role of subordinate contribution between subordinate performance and leader ostracism (H3a)/recognition (H3b), bootstrap method was used for analysis, the number of repeated samplings was set to 5,000 and the confidence interval level was 95%, the results provided support for H3a [indirect effect = −0.071, 95% CI = (−0.161, −0.001)] and H3b [indirect effect = 0.066, 95% CI = (0.006, 0.135)].

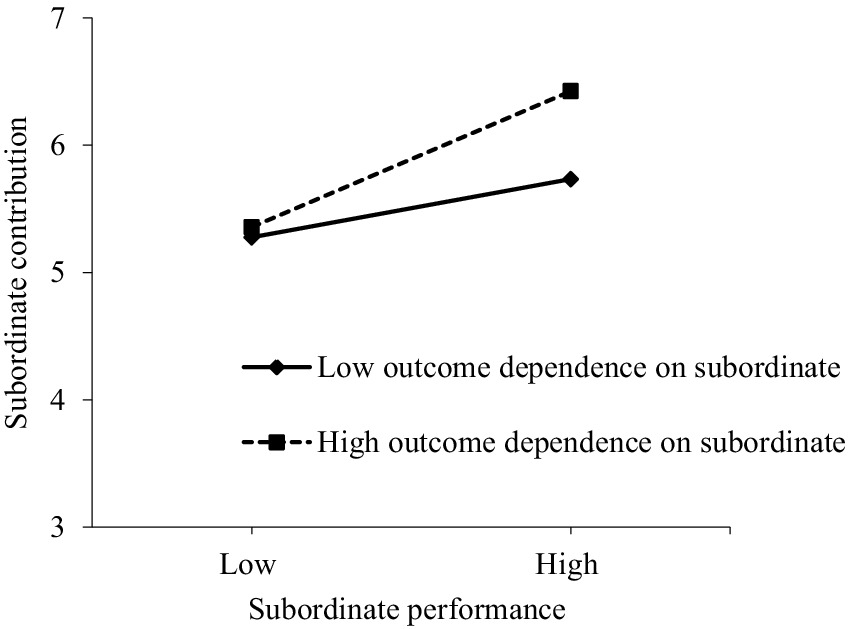

According to Model 2, the interaction term involving subordinate performance and outcome dependence on subordinate significantly predicted subordinate contribution (γ = 0.153, p < 0.01), which supported H4. To demonstrate the moderating effects of outcome dependence, we drew a simple slope plot (see Figure 2). When outcome dependence on subordinate was high, subordinate performance had stronger positive effect on contribution (γ = 0.534, p < 0.001). In the case of low outcome dependence on subordinate, such effect was weakened (γ = 0.229, p < 0.01).

Further, the moderated indirect effect of outcome dependence on subordinate was examined. The results displayed in Table 5 revealed that, the indirect influence of subordinate performance on leader ostracism through subordinate contribution was not significant at a low level of outcome dependence on subordinate [indirect effect = −0.033, 95% CI = (−0.086, 0.001)] but remained significant when outcome dependence on subordinate was high [indirect effect = −0.096, 95% CI = (−0.218, −0.002)], besides, the difference between the two situations was significant [indirect effect = −0.064, 95% CI = (−0.159, −0.001)]. In addition, when outcome dependence on subordinate was low, the indirect effect of subordinate performance on leader recognition through subordinate contribution was not significant [indirect effect = 0.030, 95% CI = (−0.001, 0.074)] but kept significant under high outcome dependence on subordinate [indirect effect = 0.089, 95% CI = (0.007, 0.192)], and the difference between the two conditions was significant [indirect effect = 0.059, 95% CI = (0.003, 0.145)]. In summary, these results supported H5a-b.

5 Discussion

Based on social exchange theory, this study investigates the mediating role of subordinate contribution between subordinate performance and leader ostracism and recognition, as well as the moderating role of outcome dependence on subordinate. Empirical analyses of 245 subordinate data and 68 leader data indicate that subordinate performance reduces leader ostracism/promotes leader recognition by increasing subordinate contribution. Besides, the positive influence of subordinate performance on subordinate contribution and the mediating effect of subordinate contribution are stronger when outcome dependence on subordinate is high.

5.1 Theoretical implications

The above findings contribute to the existing literature in four primary ways. First, we integrate the effects of subordinate performance on leadership behaviors. Although prior research has demonstrated that subordinate performance can either inhibit negative leadership behaviors (e.g., abusive supervision, Tariq and Weng, 2018; Lyubykh et al., 2022) or promote positive leadership behaviors (e.g., empowering leadership, Cao et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022), whether these two effects can coexist remains underexplored. Our results reveal that subordinate performance can not only reduce leader ostracism (a negative behavior), but also increases leader recognition (a positive behavior), thus providing a more comprehensive confirmation of subordinate performance’s dual impacts on leadership.

Secondly, this study investigates the antecedents of leader ostracism and recognition. Previous studies have emphasized leadership styles such as leader ostracism and recognition (e.g., Wayne et al., 2002; Huang and Yuan, 2024), but they have under-investigated the motivations behind why leaders ostracize or recognize subordinates. Addressing scholars’ calls to explore the antecedents of leadership behaviors (Yang et al., 2019; Cao et al., 2022), the findings of this study indicate that low subordinate performance leads to leader ostracism, whereas high subordinate performance fosters leader recognition. This framework advances understanding of the conditions under which leader ostracism and recognition emerge.

Third, the present research enriches the mechanisms by which subordinate performance influences leadership behavior. Prior studies have mainly used social comparison theory (Tariq et al., 2021), affective events theory (Li et al., 2024) and self-control framework (Liang et al., 2016) to explain why subordinate performance impacts leadership behavior from an affective perspective, yet they have underemphasized cognitive mechanisms. Based on social exchange theory, we introduce subordinate contribution as a mediating variable and examine its role in the relationships between subordinate performance, leader ostracism, and leader recognition. This study offers a novel cognitive lens for interpreting how subordinate performance shapes leadership behavior.

Lastly, we broaden the boundary conditions of the relationship between subordinate performance and leader behavioral responses. Although leader individual differences (e.g., leader social orientation, Khan et al., 2018; Tariq et al., 2021) and leader-subordinate dyadic factors (e.g., leader-subordinate guanxi, Duarte et al., 1994; Cao et al., 2022) were identified as two critical categories of moderators influencing leaders’ interpretations of subordinate performance, whether these two categories can be incorporated remains underexplored. Our results demonstrate that outcome dependence on subordinate enhances the effect of subordinate performance on leader ostracism and recognition via leader-perceived subordinate contribution, thus offering a deeper understanding of the conditions under which subordinate performance can be welcomed by leaders.

5.2 Practical implications

At the practice level, the results of this study have valuable implications for organizations seeking to mitigate negative leader responses and amplify positive ones. Firstly, high-performing subordinates are not only less likely to be ostracized by their leaders, but also able to receive more recognition from their leaders. Organizations should encourage employees to pursue high performance. For example, they should ensure that each employee is clear about his or her work objectives and expected outcomes (Kearney et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2023). Moreover, in order to motivate employees, organizations must establish fair, transparent and timely reward systems (Mickel and Barron, 2008; Cao et al., 2022).

Additionally, subordinate contributions to team goals can reduce leader ostracism and increase their recognition, so organizations should facilitate leaders’ awareness of subordinates’ contributions. For instance, organizations should encourage leaders to collaborate with subordinates on projects to enhance interaction and cooperation (de Poel et al., 2012; Ali et al., 2022), thereby deepening leaders’ understandings of subordinates’ work and contributions. At the same time, organizations can provide leaders with special training courses (Lacerenza et al., 2017; Cohrs et al., 2020), such as emotional intelligence enhancement and communication skills strengthening, to help leaders better appreciate subordinates’ efforts.

Furthermore, when outcome dependence on subordinate is high, the indirect effects of subordinate performance on leader ostracism and recognition are both amplified. Thus, organizations can strengthen leader-subordinate job interdependence through optimized job design. For example, organizations should encourage leaders to delegate important tasks and projects to subordinates (Cheong et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2020). By assigning critical responsibilities that have a direct impact on team success, leaders become more reliant on their subordinates to achieve desired outcomes. Besides, organizations should implement evaluation systems where leaders’ performance reviews significantly incorporate subordinate development, engagement, and productivity (Walter et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2022).

5.3 Limitations and future research directions

It should be noted that this study has limitations. For instance, while leader-rated subordinate performance and subordinate-rated leadership (i.e., leader ostracism and recognition) collected at different time points effectively minimize common method variance (Rank et al., 2009; Cai et al., 2023), cross-sectional data cannot test causality among variables (Ugwu et al., 2016; Kanat-Maymon et al., 2020), particularly given that leadership is often regarded as an antecedent of subordinate performance (Chan, 2017; Ding and Yu, 2020). Longitudinal designs and experimental methods, which are better suited to infer causality (Wang et al., 2018; Moin et al., 2024) could be employed in future research to validate our model.

Although our research hypotheses are supported in China and subordinate performance may affect leaders in other cultural contexts (e.g., Khan et al., 2018; Lyubykh et al., 2022), the generalizability of these findings to other countries and regions remains unconfirmed. Future research could test our model in countries or regions other than China to explore whether subordinate performance universally reduces leader ostracism and promotes leader recognition.

Finally, this study has only focused on the effects of subordinate task performance on leader behaviors. Indeed, subordinate performance also includes extra-role performance (Landry and Vandenberghe, 2012; Vera and Sánchez-Cardona, 2023), with prior research demonstrating that subordinates’ constructive ideas (Xu et al., 2023) and personal initiative (Sharma and Kirkman, 2015) influence leadership behaviors. Investigating how subordinate extra-role performance affects leader ostracism and recognition would further refine our theoretical framework.

6 Conclusion

Previous studies have mainly focused on how leadership contributes to high subordinate performance. Applying the social exchange framework, we in turn explore how high-performing subordinates influence leadership style. When subordinates’ efforts are significant to the leader’s achievement of desired outcomes, their high performance can be positively evaluated by the leader, which in turn leads to less ostracism and more recognition from the leader. We hope that our findings will encourage future research to reveal more conditions conducive to reducing negative leadership behaviors and promoting positive ones.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

QX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. HH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SZ: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This paper was partly supported by the Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education (Grant No. 23YJA630110), the Social Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. 24GLB009), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72342027).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abson, E., and Schofield, P. (2022). Exploring the antecedents of shared leadership in event organisations. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 52, 439–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.08.003

Akkermans, J., Tomlinson, M., and Anderson, V. (2024). Initial employability development: introducing a conceptual model integrating signalling and social exchange mechanisms. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 33, 54–66. doi: 10.1080/1359432x.2023.2186783

Alaybek, B., Wang, Y., Dalal, R. S., Dubrow, S., and Boemerman, L. S. G. (2022). The relations of reflective and intuitive thinking styles with task performance: a meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 75, 295–319. doi: 10.1111/peps.12443

Ali, A., Ali, S. M., and Xue, X. F. (2022). Motivational approach to team service performance: role of participative leadership and team-inclusive climate. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 52, 75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.06.005

Azeem, M. U., Haq, I. U., De Clercq, D., and Liu, C. (2024). Why and when do employees feel guilty about observing supervisor ostracism? The critical roles of observers’ silence behavior and leader-member exchange quality. J. Bus. Ethics 194, 317–334. doi: 10.1007/s10551-023-05610-x

Bennett, N., and Lemoine, G. J. (2014). What a difference a word makes: understanding threats to performance in a VUCA world. Bus. Horiz. 57, 311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2014.01.001

Breuer, K., Nieken, P., and Sliwka, D. (2013). Social ties and subjective performance evaluations: an empirical investigation. Rev. Manag. Sci. 7, 141–157. doi: 10.1007/s11846-011-0076-3

Brewer, N., Wilson, C., and Beck, K. (1994). Supervisory behavior and team performance amongst police patrol sergeants. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 67, 69–78. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1994.tb00550.x

Cai, Y. H., Zhou, C. Y., Li, J. S., and Sun, X. L. (2023). Leaders’ competence matters in empowerment: implications on subordinates’ relational energy and task performance. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 32, 389–401. doi: 10.1080/1359432x.2022.2161370

Call, M. L., and Ployhart, R. E. (2021). A theory of firm value capture from employee job performance: a multidisciplinary perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 46, 572–590. doi: 10.5465/amr.2018.0103

Cao, Q., Niu, X. F., Wang, D. D., and Wang, R. N. (2022). Antecedents of empowering leadership: the roles of subordinate performance and supervisor-subordinate guanxi. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 31, 727–742. doi: 10.1080/1359432x.2022.2037562

Chan, S. C. H. (2017). Benevolent leadership, perceived supervisory support, and subordinates’ performance the moderating role of psychological empowerment. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 38, 897–911. doi: 10.1108/lodj-09-2015-0196

Cheong, M., Yammarino, F. J., Dionne, S. D., Spain, S. M., and Tsai, C. Y. (2019). A review of the effectiveness of empowering leadership. Leadersh. Q. 30, 34–58. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.08.005

Chun, J. U., Lee, D., and Sosik, J. J. (2018). Leader negative feedback-seeking and leader effectiveness in leader-subordinate relationships: the paradoxical role of subordinate expertise. Leadersh. Q. 29, 501–512. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.11.001

Cohrs, C., Bormann, K. C., Diebig, M., Millhoff, C., Pachocki, K., and Rowold, J. (2020). Transformational leadership and communication evaluation of a two-day leadership development program. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 41, 101–117. doi: 10.1108/Lodj-02-2019-0097

Cropanzano, R., Anthony, E. L., Daniels, S. R., and Hall, A. V. (2017). Social exchange theory: a critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 11, 479–516. doi: 10.5465/annals.2015.0099

Crossley, C., Taylor, S. G., Trevino, L. K., Taylor, R., and Rice, D. (2023). Welcome to the club? Unethical behavior and proactivity in promotion and derailment decisions. J. Organ. Behav. 44, 1340–1361. doi: 10.1002/job.2736

Crouch, A., and Yetton, P. (1988). Manager subordinate dyads—relationships among task and social contact, manager friendliness and subordinate performance in management groups. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 41, 65–82. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(88)90047-7

de Jong, S. B., Van der Vegt, G. S., and Molleman, E. (2007). The relationships among asymmetry in task dependence, perceived helping behavior, and trust. J. Appl. Psychol. 92, 1625–1637. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1625

de Poel, F. M., Stoker, J. I., and van der Zee, K. I. (2012). Climate control? The relationship between leadership, climate for change, and work outcomes. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 23, 694–713. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2011.561228

Decramer, A., Smolders, C., and Vanderstraeten, A. (2013). Employee performance management culture and system features in higher education: relationship with employee performance management satisfaction. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 24, 352–371. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2012.680602

Ding, H., and Yu, E. H. (2020). Subordinate-oriented strengths-based leadership and subordinate job performance: the mediating effect of supervisor-subordinate guanxi. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 41, 1107–1118. doi: 10.1108/lodj-09-2019-0414

Duarte, N. T., Goodson, J. R., and Klich, N. R. (1994). Effects of dyadic quality and duration on performance-appraisal. Acad. Manag. J. 37, 499–521. doi: 10.5465/256698

Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social-exchange theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2, 335–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.02.080176.002003

Ferris, D. L., Fatimah, S., Yan, M., Liang, L. D. H., Lian, H. W., and Brown, D. J. (2019). Being sensitive to positives has its negatives: an approach/avoidance perspective on reactivity to ostracism. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 152, 138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2019.05.001

Fiset, J., and Boies, K. (2018). Seeing the unseen: ostracism interventionary behaviour and its impact on employees. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 27, 403–417. doi: 10.1080/1359432x.2018.1462159

Garavan, T. N., Darcy, C., and Bierema, L. L. (2024). Learning and development in highly dynamic VUCA contexts: a new framework for the L&D function. Pers. Rev. 53, 641–656. doi: 10.1108/pr-03-2024-0284

Gong, Y. P., Huang, J. C., and Farh, J. L. (2009). Employee learning orientation, transformational leadership, and employee creativity: the mediating role of employee creative self-efficacy. Acad. Manag. J. 52, 765–778. doi: 10.5465/amj.2009.43670890

Hsiao, M. J., Teng, H. Y., Chen, C. Y., and Hsieh, C. H. (2024). The impact of leaders’ affiliative humor and aggressive humor on the workplace ostracism: a serial mediation model. J. Hosp. Market. Manag. 33, 525–546. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2023.2272665

Hu, L. Y., Jiang, N., Huang, H., and Liu, Y. (2022). Perceived competence overrides gender bias: gender roles, affective trust and leader effectiveness. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 43, 719–733. doi: 10.1108/Lodj-06-2021-0312

Huang, M. J., Geng, S., Yang, W., Law, K. M. Y., and He, Y. Q. (2024). Going beyond the role: how employees’ perception of corporate social responsibility fuels proactive customer service performance. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 76:103565. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103565

Huang, W. Y., and Yuan, C. Q. (2024). Workplace ostracism and helping behavior: a cross-level investigation. J. Bus. Ethics 190, 787–800. doi: 10.1007/s10551-023-05430-z

Hulshof, I. L., Demerouti, E., and Le Blanc, P. M. (2020). Day-level job crafting and service-oriented task performance the mediating role of meaningful work and work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 25, 355–371. doi: 10.1108/Cdi-05-2019-0111

Jahanzeb, S., Bouckenooghe, D., and Mushtaq, R. (2021). Silence and proactivity in managing supervisor ostracism: implications for creativity. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 42, 705–721. doi: 10.1108/Lodj-06-2020-0260

Jahanzeb, S., Fatima, T., and Malik, M. A. R. (2018). Supervisor ostracism and defensive silence: a differential needs approach. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 27, 430–440. doi: 10.1080/1359432x.2018.1465411

Kanat-Maymon, Y., Elimelech, M., and Roth, G. (2020). Work motivations as antecedents and outcomes of leadership: integrating self-determination theory and the full range leadership theory. Eur. Manag. J. 38, 555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2020.01.003

Kearney, E., Shemla, M., van Knippenberg, D., and Scholz, F. A. (2019). A paradox perspective on the interactive effects of visionary and empowering leadership. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 155, 20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2019.01.001

Khan, A. K., Moss, S., Quratulain, S., and Hameed, I. (2018). When and how subordinate performance leads to abusive supervision: a social dominance perspective. J. Manag. 44, 2801–2826. doi: 10.1177/0149206316653930

Krasikova, D. V., Green, S. G., and LeBreton, J. M. (2013). Destructive leadership: a theoretical review, integration, and future research agenda. J. Manag. 39, 1308–1338. doi: 10.1177/0149206312471388

Lacerenza, C. N., Reyes, D. L., Marlow, S. L., Joseph, D. L., and Salas, E. (2017). Leadership training design, delivery, and implementation: a meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 102, 1686–1718. doi: 10.1037/apl0000241

Lam, W., Huang, X., and Snape, E. (2007). Feedback-seeking behavior and leader-member exchange: Do supervisor-attributed motives matter? Acad. Manag. J. 50, 348–363. doi: 10.5465/20159858

Landry, G., and Vandenberghe, C. (2012). Relational commitments in employee-supervisor dyads and employee job performance. Leadersh. Q. 23, 293–308. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.05.016

Lee, H. W., Chi, N. W., Kim, Y. J., Lee, H., Lin, S. H., and Johnson, R. E. (2024). Leaders’ responses to receipt of proactive helping: integrating theories of approach-avoidance and challenge-hindrance. Hum. Relat. 77, 560–590. doi: 10.1177/00187267221137991

Li, Y. N., Law, K. S., Zhang, M. J., and Yan, M. (2024). The mediating roles of supervisor anger and envy in linking subordinate performance to abusive supervision: a curvilinear examination. J. Appl. Psychol. 109, 1004–1021. doi: 10.1037/apl0001141

Liang, L. D. H., Lian, H. W., Brown, D. J., Ferris, D. L., Hanig, S., and Keeping, L. M. (2016). Why are abusive supervisors abusive? A dual-system self-control model. Acad. Manag. J. 59, 1385–1406. doi: 10.5465/amj.2014.0651

Lichtenthaler, P. W., and Fischbach, A. (2018). Leadership, job crafting, and employee health and performance. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 39, 620–632. doi: 10.1108/Lodj-07-2017-0191

Liu, F. Z., and Dong, M. (2020). Perspective taking and voice solicitation: a moderated mediation model. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 58, 504–526. doi: 10.1111/1744-7941.12260

Lyubykh, Z., Bozeman, J., Hershcovis, M. S., Turner, N., and Shan, J. V. (2022). Employee performance and abusive supervision: the role of supervisor over-attributions. J. Organ. Behav. 43, 125–145. doi: 10.1002/job.2560

Mai, N. K., Do, T. T., and Nguyen, D. T. H. (2022). The impact of leadership competences, organizational learning and organizational innovation on business performance. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 28, 1391–1411. doi: 10.1108/Bpmj-10-2021-0659

Malek, S. L., Sarin, S., and Haon, C. (2020). Extrinsic rewards, intrinsic motivation, and new product development performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manage. 37, 528–551. doi: 10.1111/jpim.12554

Mawritz, M. B., Greenbaum, R. L., Butts, M. M., and Graham, K. A. (2017). I just can’t control myself: a self-regulation perspective on the abuse of deviant employees. Acad. Manag. J. 60, 1482–1503. doi: 10.5465/amj.2014.0409

Miao, Q., Newman, A., Sun, Y. X., and Xu, L. (2013). What factors influence the organizational commitment of public sector employees in China? The role of extrinsic, intrinsic and social rewards. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 24, 3262–3280. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2013.770783

Mickel, A. E., and Barron, L. A. (2008). Getting “more bang for the buck” symbolic value of monetary rewards in organizations. J. Manage. Inq. 17, 329–338. doi: 10.1177/1056492606295502

Moin, M. F., Omar, M. K., Ali, A., Rasheed, M. I., and Abdelmotaleb, M. (2024). A moderated mediation model of knowledge hiding. Serv. Ind. J. 44, 378–390. doi: 10.1080/02642069.2022.2112180

Moss, S. E., and Martinko, M. J. (1998). The effects of performance attributions and outcome dependence on leader feedback behavior following poor subordinate performance. J. Organ. Behav. 19, 259–274.

Ni, D., Liu, X., and Zheng, X. M. (2022). How and when does service performance improve positive emotions? An employee-customer social exchange perspective. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 31, 367–382. doi: 10.1080/1359432x.2021.1981292

O’Reilly, J., Robinson, S. L., Berdahl, J. L., and Banki, S. (2015). Is negative attention better than no attention? The comparative effects of ostracism and harassment at work. Organ. Sci. 26, 774–793. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2014.0900

Porter, C. O. L. H., Franklin, D. A., Swider, B. W., and Yu, R. C. F. (2016). An exploration of the interactive effects of leader trait goal orientation and goal content in teams. Leadersh. Q. 27, 34–50. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.09.004

Rank, J., Nelson, N. E., Allen, T. D., and Xu, X. (2009). Leadership predictors of innovation and task performance: subordinates’ self-esteem and self-presentation as moderators. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 82, 465–489. doi: 10.1348/096317908x371547

Rivera, M., Jiang, C., and Kumar, S. (2024). Seek and ye shall find: an empirical examination of the effects of seeking real-time feedback on employee performance evaluations. Inf. Syst. Res. 35, 783–806. doi: 10.1287/isre.2021.0130

Sarwar, A., and Muhammad, L. (2021). Impact of organizational mistreatment on employee performance in the hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 33, 513–533. doi: 10.1108/Ijchm-01-2020-0051

Sharma, P. N., and Kirkman, B. L. (2015). Leveraging leaders: a literature review and future lines of inquiry for empowering leadership research. Group Organ. Manage. 40, 193–237. doi: 10.1177/1059601115574906

Shi, J. Q., Johnson, R. E., Liu, Y. H., and Wang, M. (2013). Linking subordinate political skill to supervisor dependence and reward recommendations: a moderated mediation model. J. Appl. Psychol. 98, 374–384. doi: 10.1037/a0031129

Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace—dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 38, 1442–1465. doi: 10.5465/256865

Tang, G. Y., Chen, Y., van Knippenberg, D., and Yu, B. J. (2020). Antecedents and consequences of empowering leadership: leader power distance, leader perception of team capability, and team innovation. J. Organ. Behav. 41, 551–566. doi: 10.1002/job.2449

Tang, T. L. P., Sutarso, T., Davis, G. M. T. W., Dolinski, D., Ibrahim, A. H. S., and Wagner, S. L. (2008). To help or not to help? The Good Samaritan effect and the love of money on helping behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 82, 865–887. doi: 10.1007/s10551-007-9598-7

Tariq, H., and Weng, Q. X. (2018). Accountability breeds response-ability instrumental contemplation of abusive supervision. Pers. Rev. 47, 1019–1042. doi: 10.1108/Pr-05-2017-0149

Tariq, H., Weng, Q. X., Ilies, R., and Khan, A. K. (2021). Supervisory abuse of high performers: a social comparison perspective. Appl. Psychol. 70, 280–310. doi: 10.1111/apps.12229

Tsai, W. C., Chen, H. W., and Cheng, J. W. (2009). Employee positive moods as a mediator linking transformational leadership and employee work outcomes. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 20, 206–219. doi: 10.1080/09585190802528714

Ugwu, L. I., Enwereuzor, I. K., and Orji, E. U. (2016). Is trust in leadership a mediator between transformational leadership and in-role performance among small-scale factory workers? Rev. Manag. Sci. 10, 629–648. doi: 10.1007/s11846-015-0170-z

Umrani, W. A., Bachkirov, A. A., Nawaz, A., Ahmed, U., and Pahi, M. H. (2024). Inclusive leadership, employee performance and well-being: an empirical study. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 45, 231–250. doi: 10.1108/Lodj-03-2023-0159

Van Scotter, I. I., and Van Scotter, J. R. (2021). Does autonomy moderate the relationships of task performance and interpersonal facilitation, with overall effectiveness? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 32, 1685–1706. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2018.1542607

Vasquez, C. A., Madrid, H. P., and Niven, K. (2021). Leader interpersonal emotion regulation motives, group leader-member exchange, and leader effectiveness in work groups. J. Organ. Behav. 42, 1168–1185. doi: 10.1002/job.2557

Vera, M., and Sánchez-Cardona, I. (2023). Is it your engagement or mine? Linking supervisors’ work engagement and employee performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 34, 912–940. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2021.1996431

Wadei, K. A., Asaah, J. A., Amoah-Ashyiah, A., and Wadei, B. (2023). Do the right thing the right way! How ethical leaders increase employees creative performance. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 30, 428–441. doi: 10.1177/15480518231195597

Walter, F., Lam, C. K., van der Vegt, G. S., Huang, X., and Miao, Q. (2015). Abusive supervision and subordinate performance: instrumentality considerations in the emergence and consequences of abusive supervision. J. Appl. Psychol. 100, 1056–1072. doi: 10.1037/a0038513

Wang, S. H., De Pater, I. E., Yi, M., Zhang, Y. C., and Yang, T. P. (2022). Empowering leadership: employee-related antecedents and consequences. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 39, 457–481. doi: 10.1007/s10490-020-09734-w

Wang, M. Y., Lu, C. Q., and Lu, L. (2023). The positive potential of presenteeism: an exploration of how presenteeism leads to good performance evaluation. J. Organ. Behav. 44, 920–935. doi: 10.1002/job.2604

Wang, A. C., Tsai, C. Y., Dionne, S. D., Yammarino, F. J., Spain, S. M., Ling, H. C., et al. (2018). Benevolence-dominant, authoritarianism-dominant, and classical paternalistic leadership: testing their relationships with subordinate performance. Leadersh. Q. 29, 686–697. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.06.002

Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., Bommer, W. H., and Tetrick, L. E. (2002). The role of fair treatment and rewards in perceptions of organizational support and leader-member exchange. J. Appl. Psychol. 87, 590–598. doi: 10.1037//0021-9010.87.3.590

Wee, E. X. M., Liao, H., Liu, D., and Liu, J. (2017). Moving from abuse to reconciliation: a power-dependence perspective on when and how a follower can break the spiral of abuse. Acad. Manag. J. 60, 2352–2380. doi: 10.5465/amj.2015.0866

Williams, L. J., and Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job-satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 17, 601–617. doi: 10.1177/014920639101700305

Xu, J. Y., and Li, Y. T. (2024). Uncover the veil of power: the determining effect of subordinates’ instrumental value on leaders’ power-induced behaviors. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 41, 1661–1696. doi: 10.1007/s10490-023-09892-7

Xu, A. J., Loi, R., and Cai, Z. Y. (2023). Not threats, but resources: an investigation of how leaders react to employee constructive voice. Br. J. Manage. 34, 37–56. doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.12581

Yang, Q., and Wei, H. (2017). Ethical leadership and employee task performance: examining moderated mediation process. Manag. Decis. 55, 1506–1520. doi: 10.1108/Md-09-2016-0627

Yang, J. C., Zhang, W., and Chen, X. (2019). Why do leaders express humility and how does this matter: a rational choice perspective. Front. Psychol. 10:1925. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01925

Zhang, J. H., Huang, R., Huang, B. L., Xu, T., and Zhao, G. Q. (2024). Employee motivation and outcomes of developing and maintaining high-quality supervisor-subordinate guanxi in hotel operations. Cornell Hosp. Q. 65, 509–525. doi: 10.1177/19389655241226563

Zhang, I. D., Mao, Y. A., and Wong, C. S. (2023). Potential buffering effect of being a right-hand subordinate on the influence of abusive supervision. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 44, 72–86. doi: 10.1108/Lodj-05-2022-0216

Zhang, Z., and Min, M. (2021). Organizational rewards and knowledge hiding: task attributes as contingencies. Manag. Decis. 59, 2385–2404. doi: 10.1108/Md-02-2020-0150

Keywords: subordinate performance, subordinate contribution, leader ostracism, leader recognition, outcome dependence on subordinate

Citation: Xu Q, Huang H, Zhang X, Zhao S and Zhou L (2025) Can subordinate performance simultaneously reduce leader ostracism and promote leader recognition? A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 16:1588034. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1588034

Edited by:

Wenjing Cai, University of Science and Technology of China, ChinaReviewed by:

Guanglei Zhang, Wuhan University of Technology, ChinaChulwoo Kim, Gachon University, Republic of Korea

Copyright © 2025 Xu, Huang, Zhang, Zhao and Zhou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hao Huang, aGg3OTkzNzk5NzVAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Qin Xu1

Qin Xu1 Hao Huang

Hao Huang Lulu Zhou

Lulu Zhou