- 1School of Computer and Information Technology, Northeast Petroleum University, Daqing, China

- 2Chuang Ke Primary School, Dalian, China

- 3School of Educational Science, Harbin Normal University, Harbin, China

- 4School of Mechanical Science and Engineering, Northeast Petroleum University, Daqing, China

Introduction: This study investigates the impact of perceived teacher emotional support on university students’ engagement in online learning, with a particular focus on the mediating role of academic burnout. Although prior research has established that perceived teacher emotional support positively influences learning engagement and that academic burnout has a negative effect, the underlying mechanisms among these three variables in an online learning context remain unclear.

Methods: Participants were drawn from a public university in China. Data were collected from 361 undergraduate students through a structured questionnaire, and the relationships among the key variables were analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM).

Results: The findings indicate that perceived teacher emotional support is a significant predictor of online learning engagement. Moreover, academic burnout serves as a mediator: higher levels of perceived emotional support from teachers are associated with lower levels of burnout and increased engagement in online learning activities. These results underscore the critical role of perceived teacher emotional support in mitigating academic burnout and enhancing students’ motivation and participation in online learning environments.

1 Introduction

The rapid growth of internet technology in the digital age has significantly transformed the field of education. Online learning has gradually become a crucial component of modern education, providing learners with unprecedented opportunities and experiences (Dhawan, 2020). However, online learning environments also present significant challenges, such as the lack of emotional connection between students and instructors, as well as lower student engagement compared to traditional face-to-face learning (Xie et al., 2020; Martin and Borup, 2022). Learning engagement is a reliable indicator of online learning quality (Phan et al., 2016). Therefore, understanding the factors that affect online learning engagement is crucial importance. And many studies have focused on identifying these key factors.

Online learning engagement refers to the sustained focus and involvement students demonstrate while using online learning platforms. Scholars generally categorize online learning engagement into three dimensions: cognitive, emotional, and behavioral (Hu et al., 2016). The factors influencing online learning engagement are numerous and complex. Most studies treat online learning engagement as the outcome variable and examine how other factors influence it. From the student’s perspective, several factors affect engagement, including the willingness to use electronic devices, self-efficacy (Getenet et al., 2024), motivation and attitude (Ferrer et al., 2022), and personality traits (Yan et al., 2024). From the teacher’s perspective, existing research has confirmed the impact of teacher support on learning engagement (Ma et al., 2023; Wang L, 2022; Luan et al., 2023), including aspects such as teacher-student interaction (Sun et al., 2022) and feedback (Pan and Shao, 2020). In addition to these factors, the learning environment (Luo et al., 2022) and parental support have also been identified as significant contributors to online learning engagement (Novianti and Garzia, 2020).

The concept of “burnout” originally derives from “occupational burnout” which refers to the phenomenon of individuals experiencing fatigue, depression, and other negative emotions due to prolonged exposure to stress (Freudenberger, 1974). In the context of education, this is known as academic burnout. Academic burnout is characterized by students’ feelings of boredom, frustration, and a lack of motivation or interest in learning, yet still feel the obligation to engage in it. This often leads to avoidance behaviors that hinder their learning (Yang and Lian, 2005). In online learning environments, the lack of emotional connections between students and instructors, as well as among students themselves, contributes to higher levels of academic burnout. Furthermore, increased screen time and prolonged use of electronic devices can exacerbate stress and contribute to burnout (Mheidly et al., 2020; Mu and Guo, 2022).

Existing research has shown that teachers’ emotional support plays a mitigating and buffering role in reducing academic burnout and other negative behaviors (Karimi and Fallah, 2021). However, it remains unclear whether university students truly perceive this support and whether it effectively alleviates their negative behaviors. This issue requires further investigation. Moreover, a review of the relevant literature also indicates that teacher emotional support positively affects learning engagement (Yan et al., 2024), while academic burnout negatively affects it (Mu and Guo, 2022). However, most previous studies have focused on face-to-face learning environments and have been limited to examining the relationships between two variables at a time. To date, no study has integrated teacher emotional support, academic burnout, and learning engagement into a single comprehensive framework for analysis. Therefore, several critical questions remain: How do university students perceive teacher emotional support in an online learning environment? What impact does this support have on learning engagement? And what role does academic burnout play in the relationship between perceived teacher emotional support and learning engagement?

This study examines the effect of perceived teacher emotional support on online learning engagement and tests the mediating role of academic burnout. It aims to expand the theoretical understanding of online learning engagement and clarify how perceived teacher emotional support influences this process. By focusing on perceived teacher emotional support, the study provides practical recommendations for preventing and intervening academic burnout, with the goal of enhancing university students’ online learning engagement.

2 Theoretical background and hypotheses

2.1 Perceived teacher emotional support

Yeung and Leadbeater (2010) argue that teachers’ encouragement, respect, and other forms of emotional support exhibited during the teaching process play a crucial role (Yeung and Leadbeater, 2010). Once students perceive this emotional support, it can have a positive impact on their learning (He et al., 2024). Therefore, some scholars focus more on students’ perceptions. For instance, scholars such as Gao et al. (2017) emphasize the importance of students’ perceived care, affection, respect, support, and assistance from teachers (Gao et al., 2017). This study adopts a learner-centered perspective and defines teacher emotional support as students’ perceived respect, care, and understanding from their teachers (Ryan and Patrick, 2001). Previous studies have found that such support contributes to the establishment of positive teacher-student relationships, enhances students’ positive emotions, fosters academic autonomy, and significantly improves academic achievement (Guo et al., 2023).

2.2 The effect of perceived teacher emotional support on learning engagement

Teacher emotional support is categorized under the emotional support dimension of social support, constituting a crucial component within the social support system. According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory, every individual has a fundamental need for belonging and love, with emotional support being the most direct way to fulfill this need (McLeod, 2007). Teacher emotional support helps meet students’ psychological needs, thereby positively influencing their learning engagement (Jin and Wang, 2019). Previous studies have shown a significant positive relationship between perceived teacher emotional support and online learning engagement (Yan et al., 2024). When students perceive emotional support from their teachers, it enhances their learning engagement (Wang et al., 2022), especially in terms of cognitive and affective engagement (Liao et al., 2023). Research indicates that teacher care and attention enhance both emotional and behavioral engagement, regardless of gender (Bru et al., 2019). Additionally, teacher emotional support indirectly boosts students’ online academic engagement by enhancing their intrinsic motivation (Wang Y., 2022). Existing research suggests that the more emotional support students receive from their teachers, the greater their behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement in online learning. Therefore, based on Maslow’s theory and previous research, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1. Perceived teacher emotional support positively and significantly predicts university students’ online learning engagement.

2.3 The impact of academic burnout on online learning engagement

Academic burnout is prevalent among university students and can affect their learning engagement to varying degrees (Cano et al., 2024; Nurani et al., 2022). In online learning environments, the impact of academic burnout is particularly significant. Existing research has demonstrated a significant negative correlation between online learning engagement and academic burnout (Cazan, 2015). The online learning environment provides an easy escape for students experiencing high levels of academic burnout, leading to reduced time spent on learning engagement (Wang and Cai, 2021). Additionally, studies have found that academic burnout during online learning is not only negatively correlated with students’ cognitive engagement but also tends to increase over time (Huang et al., 2024). Based on these findings, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2. Academic burnout negatively predicts online learning engagement among university students.

2.4 The effect of perceived teacher emotional support on academic burnout

Existing research has shown a significant negative correlation between perceived teacher emotional support and academic burnout (Karimi and Fallah, 2021). Romano et al. (2020) found that high school students’ perception of teacher emotional support is a strong predictor of lower academic burnout (Romano et al., 2020). Similarly, Li et al. (2019) confirmed that middle school students who perceive more emotional support from their teachers tend to feel more confident in their learning and experience less academic burnout (Li et al., 2019). Additionally, research indicated that middle school students with higher levels of perceived teacher emotional support experience lower academic burnout (An, 2020). In online learning environments, teacher emotional support plays a crucial role in alleviating academic burnout caused by the lack of face-to-face interaction and the physical and temporal separation between teachers and students (Yang et al., 2022). Overall, both domestic and international studies have consistently found that perceived teacher emotional support helps alleviate and inhibit academic burnout. Based on these findings, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3. Perceived teacher emotional support negatively predicts academic burnout among university students.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Participants

This study involved 361 first-year students from a university in Daqing, China. The study was conducted entirely in an online environment, and all participants were fully informed of the research objectives before data collection This study focused on first-year university students, who had undergone two and a half years of online learning during their high school education, thereby possessing more profound experiences and perceptions of online learning. The final sample consisted of 224 responses, among which 213 were valid, resulting in a validity rate of 95%. Among the valid responses, 164 were male (77%) and 49 were female (23%), all of whom were enrolled in science-related majors.

3.2 Instruments

The scales used in this study were adapted from well-established domestic and international scales, and modified based on teaching practices. A five-point Likert scale was used to measure the variables, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In the preliminary survey, we collected 126 valid questionnaires. Through item analysis and exploratory factor analysis, the scales were examined, and a total of 14 substandard items were removed across the following three scales. The wording of the items was adjusted to better align with the learners’ context.

3.2.1 Perceived teacher emotional support scale

This study primarily referenced the “Middle School Students’ Perception of Teacher Emotional Support Scale” (Gao et al., 2017). To better align with the online learning context, the perceived teacher emotional support scale was created, drawing from relevant existing scales. The final scale consisted of 15 items, categorized into three dimensions: respect, care, and understanding.

The respect dimension includes 4 items, adapted from Gao et al. (2017) and Xu et al. (2014), such as “During online learning, the teacher listens to and understands my suggestions or views before offering their own, which helps me engage more in learning.”

The care dimension includes 7 items, adapted from Gao et al. (2017), Johnson et al. (1983), Sakiz et al. (2012), and Overall et al. (2011), including statements such as “During online learning, the teacher acknowledges my progress (e.g., praising improvements in my assignment completion or work quality), which encourages me to engage more in learning.”

The understanding dimension consists of 4 items, adapted from Gao et al. (2017), Xu et al. (2014), and Song et al. (2015), including statements such as “During online learning, the teacher understands my difficulties (e.g., needing help with software downloads or needing more time to complete assignments), which motivates me to engage more in learning.”

The internal consistency coefficients for the respect, care, and understanding dimensions were 0.886, 0.933, and 0.924, respectively, while the overall reliability of the scale was 0.955. After revision, the model fit results for the perceived teacher emotional support scale showed CMIN/DF = 2.150 (<3), GFI = 0.926 (>0.90), CFI = 0.957 (>0.90), NFI = 0.923 (>0.90), IFI = 0.957 (>0.90), SRMR = 0.048 (<0.08), and RMSEA = 0.074 (<0.08), all meeting the established standards.

3.2.2 Academic burnout scale

This study adapted the “College Student Learning Burnout Scale” developed by Lian et al. (2005) and made necessary revisions to create a learning burnout scale. The final version consists of 14 items, divided into three dimensions: depressed mood (6 items), inappropriate behavior (5 items), and low sense of achievement (3 items). The consistency coefficients for the three dimensions—depressed mood, inappropriate behavior, and low sense of achievement—were 0.900, 0.842, and 0.855, respectively, while the overall reliability of the scale was 0.911. After revision, the model fit results for the academic burnout scale were as follows: CMIN/DF = 2.303 (<3), GFI = 0.909 (>0.90), CFI = 0.959 (>0.90), NFI = 0.931 (>0.90), IFI = 0.960 (>0.90), SRMR = 0.044 (<0.08), and RMSEA = 0.077 (<0.08), all of which meet the acceptable standards.

3.2.3 Online learning engagement scale

This study adapted the “Online Learning Engagement Scale” from established international scales, making necessary revisions. The final scale consists of 17 items, categorized into three dimensions: behavioral engagement (8 items), cognitive engagement (5 items), and affective engagement (4 items).

The behavioral engagement dimension includes 8 items, adapted from Sun and Rueda (2012) and Deng et al. (2020), with additional self-developed items such as “During online learning, I actively answer the teacher’s questions” and “When I do not understand a certain concept during online learning, I will ask the teacher to explain it again (e.g., using the platform’s hand-raise function or sending a real-time comment, etc.).” The cognitive engagement dimension consists of 5 items, adapted from Sun and Rueda (2012). The affective engagement dimension includes 4 items, also adapted from Sun and Rueda (2012), with additional self-developed items, such as “Online learning sometimes makes me feel sleepy.,” “During online learning, I find it very boring.,” and “I dislike online assessments.”

The consistency coefficients for behavioral, cognitive, and affective engagement, as well as the overall scale consistency, were 0.909, 0.850, 0.859, and 0.916, respectively. The model fit indices of the revised Online Learning Engagement Scale were as follows: CMIN/DF = 1.792 (<3), GFI = 0.907 (>0.90), CFI = 0.954 (>0.90), NFI = 0.903 (>0.90), IFI = 0.955 (>0.90), SRMR = 0.047 (<0.08), and RMSEA = 0.061 (<0.08), all of which meet the acceptable standards.

3.3 Common method bias test

To avoid the issue of common method bias, this study employed anonymous scale completion and reverse scoring in the distribution and processing of the scales. However, to further verify the presence of serious common method bias, Har-man’s single-factor test was conducted (Zhou and Long, 2004).

Using SPSS 25.0, an exploratory factor analysis was performed on all items from the Online Learning Engagement Scale, Academic Burnout Scale, and Perceived Teacher Emotional Support Scale. Eight factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted, with the first factor accounting for 33.074% of the variance, which is below the 40% threshold (Deng et al., 2018). This indicates that common method bias is not a significant concern in this study, allowing for further analysis.

4 Data analysis and results

The statistical analysis in this study was primarily conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0. First, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to assess the validity of the scales, and reliability was examined using Cronbach’s alpha. Subsequently, descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were conducted. Based on the theoretical framework and research hypotheses, a structural equation model (SEM) was constructed and analyzed using Amos 24.0 to evaluate model fit. This analysis aimed to explore the relationship between perceived teacher emotional support and university students’ online learning engagement, specifically examining the mediating role of academic burnout.

4.1 Measurement model analysis

The Cronbach’s alpha values for each scale and its dimensions were calculated, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the reliability and convergent validity of the measurement model. To determine whether the model exhibits discriminant validity, chi-square difference tests were performed between different models (Wu, 2010).

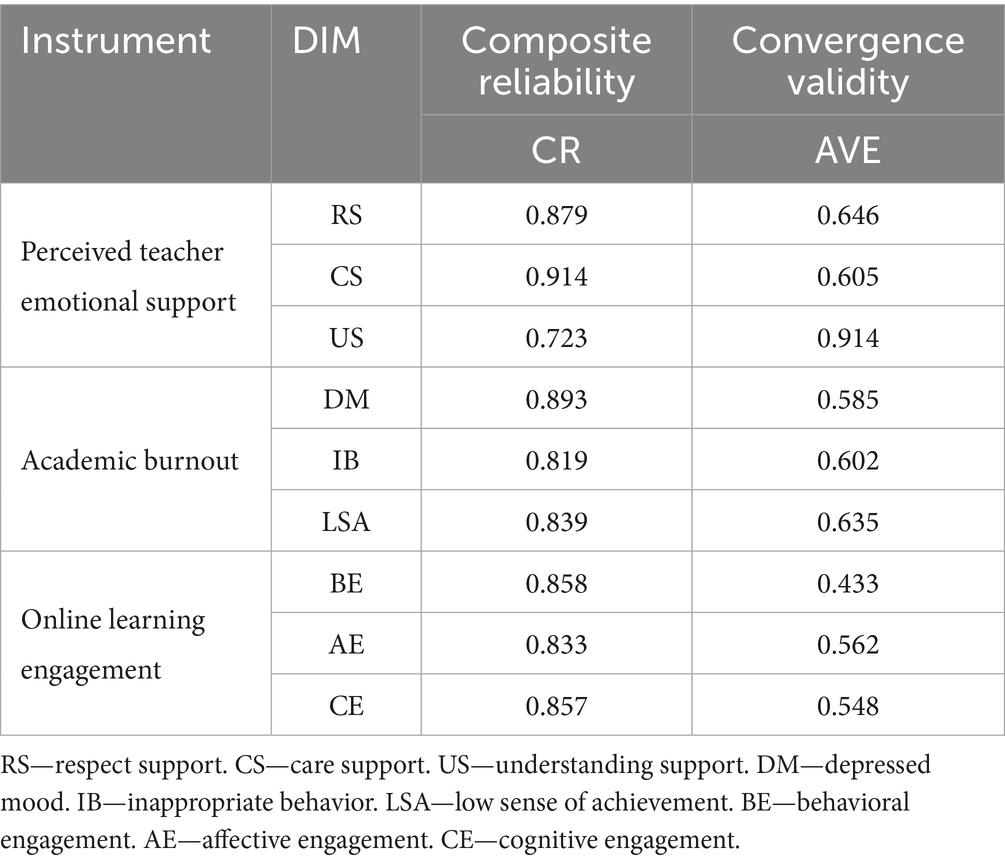

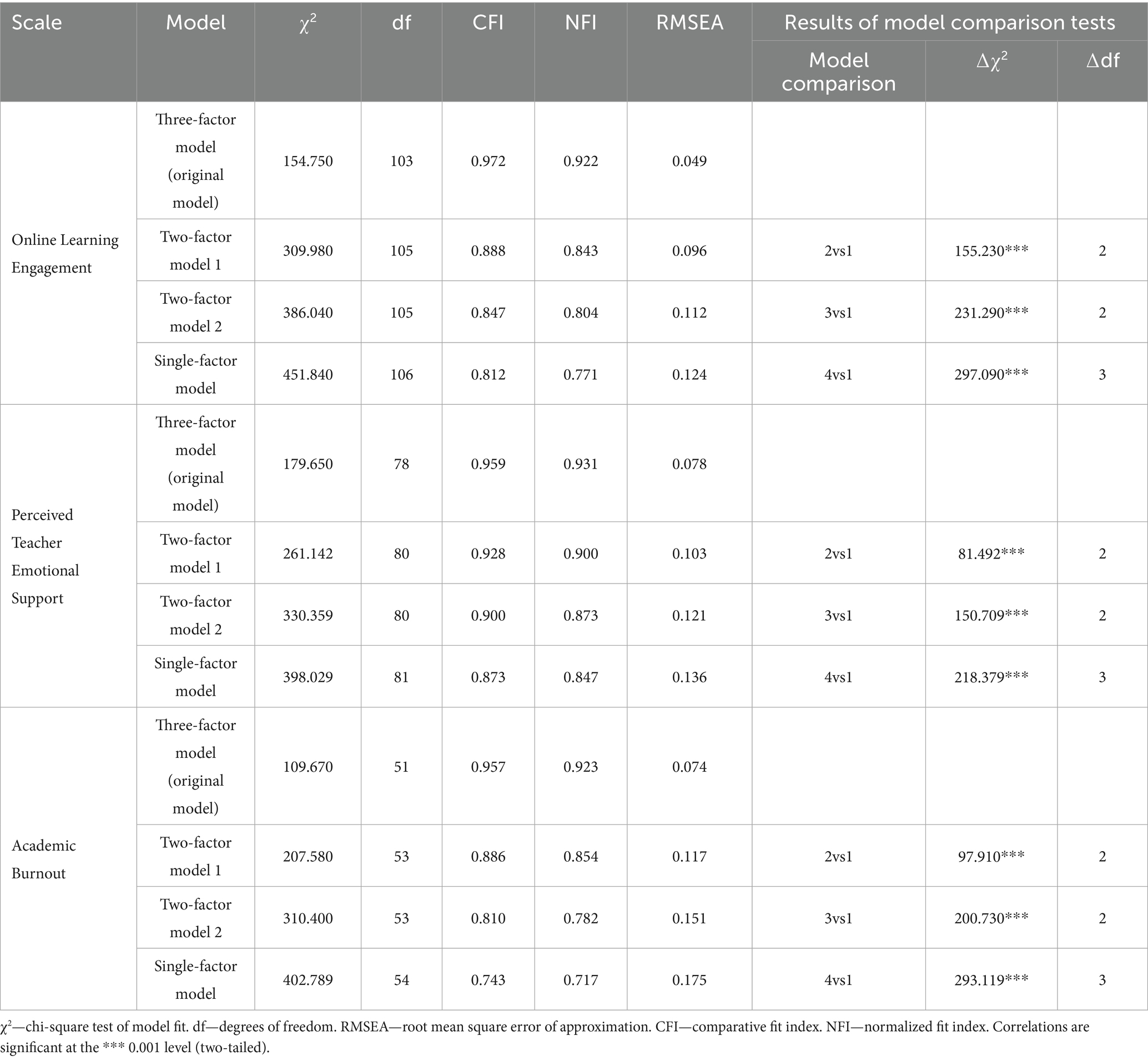

Using AMOS 24.0, the dimensions of the structural equation models for the online learning engagement, academic burnout, and perceived teacher emotional support were combined to form a three-factor model (original model), a two-factor model, and a single-factor model. Model fit indices were examined and compared across these models. The results are presented in the Tables 1, 2.

The Cronbach’s alpha values all exceed 0.8, and the composite reliability (CR) values are greater than 0.7, indicating good internal consistency reliability of the measurement scales (Wu, 2010). All standardized factor loadings are above 0.7, and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values for affective engagement and cognitive engagement were greater than 0.5, indicating effective reflection of the latent variables. The AVE value for behavioral engagement was 0.433, which falls between 0.4 and 0.5. According to Fornell and Larcker (1981), the AVE value is a relatively conservative estimate of measurement model validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Considering that the CR value was well above the recommended threshold, indicating acceptable internal reliability of the measurement items, an AVE value slightly below 0.5 is deemed acceptable (Lam, 2012).

Additionally, the model fit indices of the alternative models formed by recombining the scale dimensions were inferior to those of the original model, and all models passed the significance test (p < 0.001). This confirms that the Perceived Teacher Emotional Support, Online Learning Engagement, and Academic Burnout scales exhibit sufficient discriminant validity. Collectively, these analyses demonstrate that our measurement model exhibits good reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

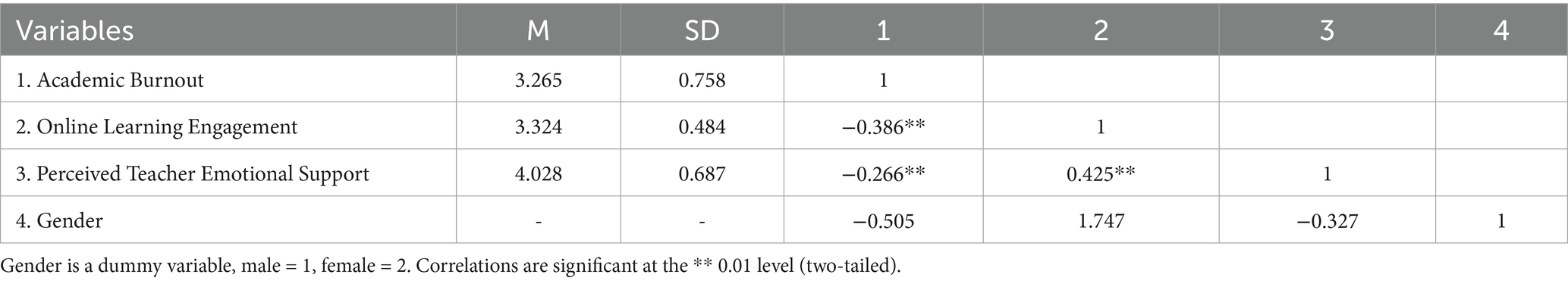

4.2 Descriptive statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for each variable are shown in Table 3. Academic burnout (M = 3.256, SD = 0.758) and online learning engagement (M = 3.324, SD = 0.484) were both at moderate to high levels, while perceived teacher emotional support (M = 4.028, SD = 0.687) was relatively high. Perceived teacher emotional support was significantly positively correlated with online learning engagement and significantly negatively correlated with academic burnout. In addition, academic burnout was also significantly negatively correlated with online learning engagement. These findings suggest that perceived perceived teacher emotional support strongly influences both online learning engagement and academic burnout. Furthermore, gender showed no significant correlation with academic burnout, online learning engagement, and perceived teacher emotional support. Therefore, the potential impact of gender is excluded from the subsequent analysis.

4.3 The impact of perceived teacher emotional support on university students’ online learning engagement: the mediating role of academic burnout

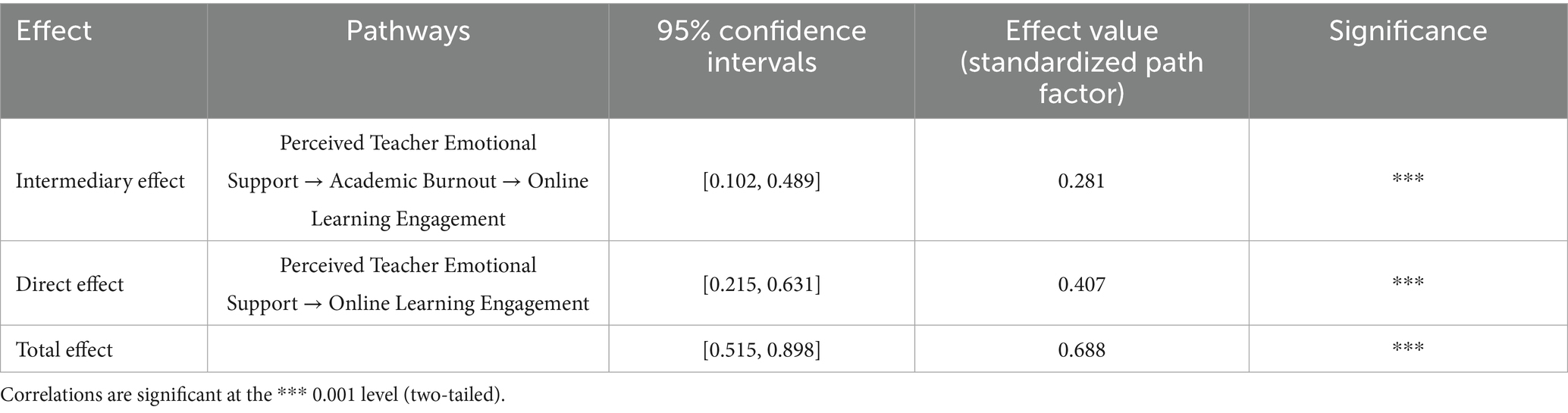

The study employs perceived teacher emotional support as the independent variable, online learning engagement as the dependent variable, academic burnout as the mediating variable. A structural equation model was constructed using Amos 24.0, and the Bootstrap method was applied to further examine the mediating effect of academic burnout. The resampling process was repeated 5,000 times to calculate the 95% confidence intervals for both the Bias-Corrected and Percentile methods. If the 95% confidence interval does not include zero, the effect is considered significant (Taylor et al., 2008). The path effect values between variables were estimated using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method with the Bootstrap approach. The effect values among the variables are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Analysis of mediating effects between perceived teacher emotional support, academic burnout, and online learning engagement.

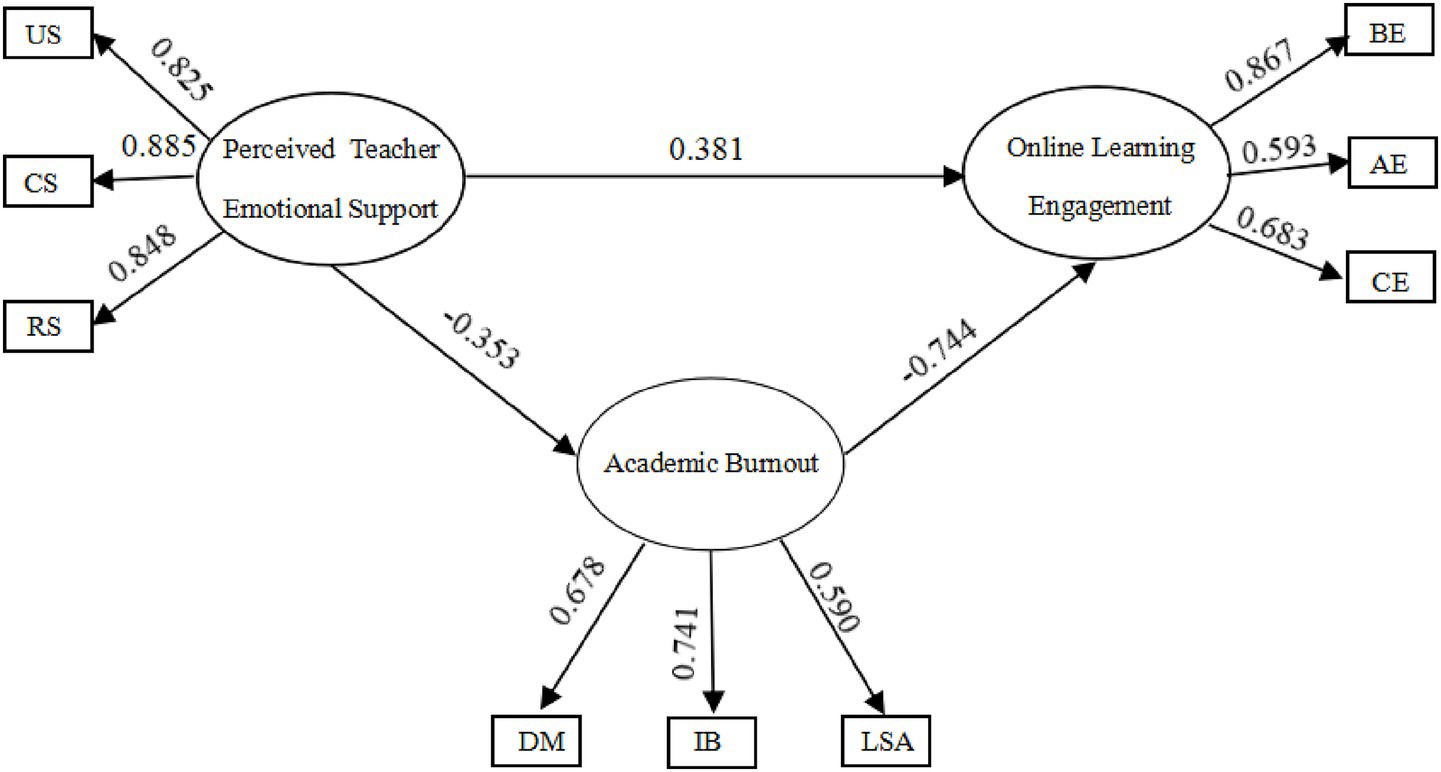

4.4 Structural model of perceived teacher emotional support, academic burnout, and online learning engagement

The structural equation model, with perceived teacher emotional support as the independent variable, academic burnout as the mediating variable, and student online learning engagement as the dependent variable, is illustrated in the figure. After model modification, the model demonstrated a good fit, with the following fit indices: CMIN/DF = 1.587 < 3, GFI = 0.97 > 0.90, CFI = 0.989 > 0.90, NFI = 0.971 > 0.90, IFI = 0.989 > 0.90, SRMR = 0.052 < 0.08, and RMSEA = 0.053 < 0.08.

As shown in Table 4 and Figure 1, perceived teacher emotional support significantly and positively predicts online learning engagement, with a direct effect value of 0.407 (p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis H1. Furthermore, perceived teacher emotional support also negatively influences online learning engagement through academic burnout, supporting Hypothesis H2 and H3, and indicating a significant mediating effect of academic burnout in the relationship between perceived teacher emotional support and online learning engagement, with a mediating effect value of 0.281 (p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Structural model of perceived teacher emotional support, academic burnout, and online learning engagement.

5 Discussion

This study aims to examine the status of university students’ online learning engagement, perceived teacher emotional support, and the level of academic burnout during online learning. Additionally, it seeks to verify the mediating role of academic burnout in the relationship between perceived teacher emotional support and online learning engagement.

The findings showed that the level of perceived teacher emotional support was moderate to high, which aligns with the results of He et al. (2024). This suggests that, during online learning, university students generally perceive teacher emotional support well. Additionally, no significant gender differences were found in the perception of teacher emotional support. In this study, university students’ online learning engagement was found to be at a moderate level, with an average score ranging from 3 to 3.5. This result is consistent with the findings of Wang L. (2022). This suggests that while students participate in various learning activities and complete learning tasks during online learning, they are not highly proactive. Overall, the level of online learning engagement among university students is not ideal.

Furthermore, the study confirmed that perceived teacher emotional support significantly predicts online learning engagement. This finding is consistent with previous research by Lobo (2023) and Lavy and Naama-Ghanayim (2020). Their research also demonstrated that perceived teacher emotional support greatly enhances meaningful learning engagement.

Based on the direct effect size and the proportion of the total effect of perceived teacher emotional support on online learning engagement (0.407, 59.2%), it is evident that perceived teacher emotional support exerts a stronger impact on students’ engagement in online learning. The scale results indicate that all three dimensions of perceived teacher emotional support have a significant impact on learning engagement, primarily reflected in the respect and care for students’ autonomy. Compared to primary and secondary school students, university students exhibit greater autonomy and individuality, requiring teachers to provide more respect and support for their ideas and actions. This is consistent with the work of Ruzek et al. (2016), who found that teachers’ emotional support motivates students through their perceived autonomy and competence. Additionally, perceived teacher emotional support plays a crucial role in helping students cope with the difficulties encountered in online learning. Since online learning imposes certain demands on the learning environment, internet connectivity, and devices, it can create additional pressure on students. Therefore, perceived teacher understanding and assistance become even more important. With sufficient emotional support, university students experience a sense of love and security, fulfilling their psychological needs and making them more willing to engage in learning, as noted by Jin and Wang (2019).

This study found that university students’ academic burnout was at a moderate level, with no significant gender differences. The lowest average score was in the “low achievement” dimension, while the highest was in the “emotional exhaustion” dimension. These findings are consistent with research by Zhao et al. (2018). The study also confirmed that perceived teacher emotional support is negatively correlated with academic burnout, which aligns with the results of Huang et al. (2024) and Li and Zhang (2024). Previous studies have consistently shown that in online learning environments, perceived teacher emotional support can alleviate academic burnout among university students.

The underlying reason is that among the factors contributing to academic burnout, the depressed mood dimension exhibits the highest factor loading, making it the dominant factor. In the online learning environment, prolonged study sessions increase feelings of burnout, frustration, and fatigue. However, teachers can foster emotional presence through synchronous interactions and asynchronous feedback, such as “paying attention to my learning progress” and “understanding my negative emotions.” These actions help students feel respected, cared for, and understood, which alleviates negative emotions and boosts academic engagement. These findings align with the research of He et al. (2024).

This study reveals the relationships among perceived teacher emotional support, academic burnout, and university students’ learning engagement. It confirms the positive effects of perceived teacher emotional support in reducing academic burnout and enhancing online learning engagement, offering important implications for online teaching and learning.

First, in the online learning environment, teachers should prioritize building strong teacher-student relationships to encourage students to open up, thereby enhancing their perception of teacher emotional support (Akram and Li, 2024). For instance, since a teacher’s image is conveyed to students through digital media, attention should be given to language expression, body language, and facial expressions to project warmth and approachability. Teachers can also engage in regular in-depth communication with students and provide timely feedback. Through positive feedback, students can feel valued and acknowledged. Additionally, as online learning may lead to increased feelings of loneliness and anxiety, teachers should actively show concern for students’ learning progress and overall well-being, offer praise for their achievements, and provide encouragement in times of difficulty to strengthen the teacher-student bond.

Second, teachers should focus on enhancing students’ sense of academic achievement to alleviate academic burnout. This can be achieved by leveraging online platforms to recognize and validate students’ learning outcomes in real time. For example, publicly praising students for insightful contributions in discussion forums or outstanding performance on assignments can help them clearly see the results of their efforts, thereby boosting their sense of accomplishment. Additionally, assigning challenging learning tasks can further enhance students’ achievement motivation. When students successfully complete such tasks, their sense of achievement increases, fostering intrinsic motivation and encouraging active engagement in learning, ultimately reducing academic burnout.

Third, teachers should pay close attention to students’ negative emotions in online learning and take proactive measures to prevent academic burnout (Wang et al., 2024). Creating a harmonious and positive online learning atmosphere allows students to study in a relaxed and enjoyable environment, making them more willing to participate in learning activities, collaborate with peers, and enhance their learning enthusiasm and initiative. Furthermore, providing individualized emotional support based on students’ unique needs can strengthen their psychological resilience, enabling them to approach challenges with a more positive mindset, thereby effectively preventing academic burnout.

6 Conclusion

This study provides an in-depth examination of the impact of perceived teacher emotional support on online learning engagement and validates the mediating role of academic burnout. The main findings are as follows:

First, the study reveals that university students’ perceived teacher emotional support, academic burnout, and learning engagement during online learning are all at a moderate level, with no significant gender differences. Additionally, our findings highlight the critical role of perceived teacher emotional support in enhancing online learning affective, significantly influencing behavioral, cognitive, and affective engagement.

Second, academic burnout serves as a key mediating factor affecting learning engagement in online learning environments. Perceived teacher emotional support not only directly enhances online learning engagement but also exerts an indirect effect by alleviating academic burnout, further strengthening engagement.

Despite these findings, the study has several limitations. First, the data for the study variables were primarily collected through self-reported scale, which may introduce subjectivity and limit the ability to accurately reflect objective realities. Second, this study focused exclusively on first-year students majoring in computer-related disciplines. Due to the gender imbalance within this major, the generalizability of the findings may be limited. Future research will aim to expand the sample size to include students from different academic years and cultural backgrounds, in order to validate the conclusions. Finally, this study focuses solely on the positive effects of perceived teacher emotional support on academic burnout and learning engagement. Future research should consider incorporating teacher autonomy support and cognitive support into the framework to comprehensively examine the mechanisms through which teacher support influences learning engagement.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by School of Computer and Information Technology, Northeast Petroleum University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LS: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. RM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision. CD: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Software. JZ: Writing – review & editing, Validation. YY: Software, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study is supported by the project Basic Research Support Plan for Outstanding Young Teachers of Heilongjiang Province (No.YQJH2023082)”, “Northeast Petroleum University ‘National Fund’ Cultivation Program” (No.2024GPW-03), “2024 Annual Higher Education Scientific Research Planning Project” of the China Association of Higher Education (No. 24XX0407) and “Key Project of the 2023 Heilongjiang Provincial Educational Science Research Program” (No. GJB1423360).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akram, H., and Li, S. (2024). Understanding the role of teacher-student relationships in students’ online learning engagement: mediating role of academic motivation. Percept. Mot. Skills 131, 1415–1438. doi: 10.1177/00315125241248709

An, L. (2020). The relationship between middle school students’ perception of teacher emotional support and academic burnout. Zhengzhou: Zhengzhou University.

Bru, E., Virtanen, T., Kjetilstad, V., and Niemiec, C. P. (2019). Gender differences in the strength of association between perceived support from teachers and student engagement. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 65, 153–168. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2019.1659404

Cano, F., Pichardo, C., Justicia-Arráez, A., Romero-López, M., and Berbén, A. B. G. (2024). Identifying higher education students’ profiles of academic engagement and burnout and analyzing their predictors and outcomes. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 39, 4181–4206. doi: 10.1007/s10212-024-00857-y

Cazan, A. M. (2015). Learning motivation, engagement, and burnout among university students. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 187, 413–417. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.077

Deng, R., Benckendorff, P., and Gannaway, D. (2020). Learner engagement in MOOCs: scale development and validation. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 51, 245–262. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12810

Deng, W., Li, X., Chen, B., Luo, K., and Zeng, X. (2018). Current status of common method bias tests in domestic psychological literature. Jiangxi Normal Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 42, 447–453. doi: 10.16357/j.cnki.issn1000-5862.2018.05.02

Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: a panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 49, 5–22. doi: 10.1177/0047239520934018

Ferrer, J., Ringer, A., Saville, K., AParris, M., and Kashi, K. (2022). Students’ motivation and engagement in higher education: the importance of attitude to online learning. High. Educ. 83, 317–338. doi: 10.1007/s10734-020-00657-5

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Freudenberger, H. J. (1974). Staff burn-out. J. Soc. Issues 30, 159–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x

Gao, D., Li, X., and Qiao, H. (2017). Development of a questionnaire on middle school students’ perception of teacher emotional support. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 25, 111–115. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2017.01.025

Getenet, S., Cantle, R., Redmond, P., and Albion, P. (2024). Students’ digital technology attitude, literacy, and self-efficacy and their effect on online learning engagement. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 21:3. doi: 10.1186/s41239-023-00437-y

Guo, Q., Samsudin, S., Yang, X., Gao, J., Ramlan, M. A., Abdullah, B., et al. (2023). Relationship between perceived teacher support and student engagement in physical education: a systematic review. Sustain. For. 15:6039. doi: 10.3390/su15076039

He, L., Feng, L., and Ding, J. (2024). The relationship between perceived teacher emotional support, online academic burnout, academic self-efficacy, and online English academic engagement of Chinese EFL learners. Sustain. For. 16:5542. doi: 10.3390/su16135542

Hu, M., Li, H., Deng, W., and Guan, H. (2016). “Student engagement: One of the necessary conditions for online learning.” In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Educational Innovation Through Technology (EITT), Tainan, China, pp. 22–24 September 2016.

Huang, C., Tu, Y., He, T., Han, Z., and Wu, X. (2024). Longitudinal exploration of online learning burnout: the role of social support and cognitive engagement. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 39, 361–388. doi: 10.1007/s10212-023-00693-6

Jin, G., and Wang, Y. (2019). The influence of gratitude on learning engagement among adolescents: the multiple mediating effects of teachers’ emotional support and students’ basic psychological needs. J. Adolesc. 77, 21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.09.006

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R., and Anderson, D. (1983). Social interdependence and classroom climate. J. Psychol. 114, 135–142. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1983.9915406

Karimi, M. N., and Fallah, N. (2021). Academic burnout, shame, intrinsic motivation, and teacher affective support among Iranian EFL learners: a structural equation modeling approach. Curr. Psychol. 40, 2026–2037. doi: 10.1007/s12144-019-0138-2

Lam, L. W. (2012). Impact of competitiveness on salespeople’s commitment and performance. J. Bus. Res. 65, 1328–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.026

Lavy, S., and Naama-Ghanayim, E. (2020). Why care about caring? Linking teachers’ caring and sense of meaning at work with students’ self-esteem, well-being, and school engagement. Teach. Teach. Educ. 91:103046. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2020.103046

Li, X., Qiao, H., Liu, Y., and Gao, D. (2019). Middle school students’ comprehension of teachers’ emotional support on academic burnout: a mediated moderating effect. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2, 414–417. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2019.02.042

Li, Y., and Zhang, L. (2024). Exploring the relationships among teacher-student dynamics, learning enjoyment, and burnout in EFL students: the role of emotional intelligence. Front. Psychol. 14:1329400. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1329400

Lian, R., Yang, L., and Wu, L. (2005). Relationship between professional commitment and learning burnout of undergraduates and scales developing. Acta Psychol. Sin. 5, 632–636. doi: cnki:sun:xlxb.0.2005-05-008

Liao, H., Zhang, Q., Yang, L., and Fei, Y. (2023). Investigating relationships among regulated learning, teaching presence, and student engagement in blended learning: An experience sampling analysis. Educ. Inf. Technol. 28, 12997–13025. doi: 10.1007/s10639-023-11717-5

Lobo, J. (2023). Instructor emotional support, academic resiliency, and school engagement in an online learning setting during Covid-19 pandemic. J. Learn. Dev. 10, 252–266. doi: 10.56059/jl4d.v10i2.826

Luan, L., Hong, J. C., Cao, M., Dong, Y., and Hou, X. (2023). Exploring the role of online EFL learners’ perceived social support in their learning engagement: a structural equation model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 31, 1703–1714. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2020.1855211

Luo, N., Li, H., Zhao, L., Wu, Z., and Zhang, J. (2022). Promoting student engagement in online learning through harmonious classroom environment. Asia Pac. Educ. Res. 31, 541–551. doi: 10.1007/s40299-021-00606-5

Ma, X., Jiang, M., and Nong, L. (2023). The effect of teacher support on Chinese university students’ sustainable online learning engagement and online academic persistence in the post-epidemic era. Front. Psychol. 14:1076552. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1076552

Martin, F., and Borup, J. (2022). Online learner engagement: conceptual definitions, research themes, and supportive practices. Educ. Psychol. 57, 162–177. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2022.2089147

McLeod, S. (2007). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Simply Psychol. 1, 1–30. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.15240896

Mheidly, N., Fares, M. Y., and Fares, J. (2020). Coping with stress and burnout associated with telecommunication and online learning. Front. Public Health 8:574969. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.574969

Mu, D., and Guo, W. (2022). Impact of students’ online learning burnout on learning performance-the intermediary role of game evaluation. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 17, 239–253. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v17i02.28555

Novianti, R., and Garzia, M. (2020). Parental engagement in children’s online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Teach. Learn. Elem. Educ. 3, 117–131. doi: 10.33578/jtlee.v3i2.7845

Nurani, G. A., Nafis, R. Y., Ramadhani, A. N., Prastiwi, M., Hanif, N., and Ardianto, D. (2022). Online learning impacts on academic burnout: a literature review. J. Digital Learn. Educ. 2, 150–158. doi: 10.52562/jdle.v2i3.433

Overall, N. C., Deane, K. L., and Peterson, E. R. (2011). Promoting doctoral students’ research self-efficacy: combining academic guidance with autonomy support. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 30, 791–805. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2010.535508

Pan, X., and Shao, H. (2020). Teacher online feedback and learning motivation: learning engagement as a mediator. Soc. Behav. Pers. 48, 1–10. doi: 10.2224/sbp.9118

Phan, T., McNeil, S. G., and Robin, B. R. (2016). Students’ patterns of engagement and course performance in a massive open online course. Comput. Educ. 95, 36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.11.015

Romano, L., Tang, X., Hietajärvi, L., Salmela-Aro, K., and Fiorilli, C. (2020). Students’ trait emotional intelligence and perceived teacher emotional support in preventing burnout: the moderating role of academic anxiety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:4771. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134771

Ruzek, E. A., Hafen, C. A., Allen, J. P., Gregory, A., Mikami, A. Y., and Pianta, R. C. (2016). How teacher emotional support motivates students: the mediating roles of perceived peer relatedness, autonomy support, and competence. Learn. Instr. 42, 95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.004

Ryan, A. M., and Patrick, H. (2001). The classroom social environment and changes in adolescents’ motivation and engagement during middle school. Am. Educ. Res. J. 38, 437–460. doi: 10.3102/00028312038002437

Sakiz, G., Pape, S. J., and Hoy, A. W. (2012). Does perceived teacher affective support matter for middle school students in mathematics classrooms? J. Sch. Psychol. 50, 235–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2011.10.005

Song, J., Bong, M., Lee, K., and Kim, S. I. (2015). Longitudinal investigation into the role of perceived social support in adolescents’ academic motivation and achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 107, 821–841. doi: 10.1037/edu0000016

Sun, J. C. Y., and Rueda, R. (2012). Situational interest, computer self-efficacy, and self-regulation: their impact on student engagement in distance education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 43, 191–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01157.x

Sun, H. L., Sun, T., Sha, F. Y., Gu, X. Y., Hou, X. R., Zhu, F. Y., et al. (2022). The influence of teacher-student interaction on the effects of online learning: based on a serial mediating model. Front. Psychol. 13:779217. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.779217

Taylor, A. B., MacKinnon, D. P., and Tein, J. Y. (2008). Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organ. Res. Methods 11, 241–269. doi: 10.1177/1094428107300344

Wang, L. (2022). Student intrinsic motivation for online creative idea generation: mediating effects of student online learning engagement and moderating effects of teacher emotional support. Front. Psychol. 13:954216. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.954216

Wang, Y. (2022). Effects of teaching presence on learning engagement in online courses. Distance Educ. 43, 139–156. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2022.2029350

Wang, S., and Cai, H. (2021). Analysis of graduate students’ time investment in online and offline learning and its influencing factors-based on a large-scale survey of online teaching and learning data. China Higher Educ. Res. 1, 56–63. doi: 10.16298/j.cnki.1004-3667.2021.01.09

Wang, Y., Xin, Y., and Chen, L. (2024). Navigating the emotional landscape: insights into resilience, engagement, and burnout among Chinese high school English as a foreign language learners. Learn. Motiv. 86:101978. doi: 10.1016/j.lmot.2024.101978

Wang, W., Zhang, L., Wang, Y., and Yang, S. (2022). The chain mediating effect of perceived teacher emotional support on academic self-concept among middle school students: the role of class environment and learning engagement. Occup. Health 38, 2552–2555. doi: 10.13329/j.cnki.zyyjk.2022.0549

Wu, M. (2010). Structural equation modeling-AMOS: Operation and application. 2nd Edn. Chongqing: Chongqing University Press, 52-54–258-262.

Xie, X., Siau, K., and Nah, F. F. H. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic-online education in the new normal and the next normal. J. Inf. Technol. Case Appl. Res. 22, 175–187. doi: 10.1080/15228053.2020.1824884

Xu, X., Yang, D., and Jia, J. (2014). The development and characteristics of the middle school students’ perception of teacher emotional support questionnaire. Southwest Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 36, 175–179. doi: 10.13718/j.cnki.xdzk.2014.06.029

Yan, Y., Zhang, X., Lei, T., Zheng, P., and Jiang, C. (2024). The interrelationships between Chinese learners’ trait emotional intelligence and teachers’ emotional support in learners’ engagement. BMC Psychol. 12:35. doi: 10.1186/s40359-024-01519-w

Yang, L., and Lian, R. (2005). Research status and prospects of learning burnout. J. Jimei Univ. (Educ. Sci. Ed.). 2, 54–58. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-6493.2005.02.010

Yang, G., Sun, W., and Jiang, R. (2022). Interrelationship amongst university student perceived learning burnout, academic self-efficacy, and teacher emotional support in China’s English online learning context. Front. Psychol. 13:829193. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.829193

Yeung, R., and Leadbeater, B. (2010). Adults make a difference: the protective effects of parent and teacher emotional support on emotional and behavioral problems of peer-victimized adolescents. J. Community Psychol. 38, 80–98. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20353

Zhao, C., Li, H., Jiang, Z., and Huang, Y. (2018). Eliminating online learners’ burnout: the impact of teacher emotional support. China Educ. Technol. 2, 29–36. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-9860.2018.02.005

Keywords: perceived teacher emotional support, academic burnout, online learning, learning engagement, university students

Citation: Sun L, Ma R, Du C, Zhao J, Yang Y and Zhang X (2025) A study on the impact of perceived teacher emotional support on university students’ online learning engagement: the mediating role of academic burnout. Front. Psychol. 16:1625857. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1625857

Edited by:

Nelly Lagos San Martín, University of the Bío Bío, ChileReviewed by:

Zhiyuan Liu, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, ChinaThananun Thanarachataphoom, Kasetsart University, Thailand

Copyright © 2025 Sun, Ma, Du, Zhao, Yang and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rongshuang Ma, MTcyNzQ5MzkyOUBxcS5jb20=

Lina Sun

Lina Sun Rongshuang Ma2*

Rongshuang Ma2*