- 1Center for Nursing Research, Cizik School of Nursing, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, United States

- 2Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, United States

- 3Department of Pediatrics, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 4Graduate School of Social Work, University of Denver, Denver, CO, United States

Purpose: Youth experiencing homelessness (YEH) are an underserved and difficult-to-reach population that experiences a disproportionate burden of trauma and stress compared to their housed peers. Prolonged trauma and stress can impact the development of negative emotions, reactive stress responses, and impulsive decision-making, which can lead to risk-taking behaviors. Growing research shows that Mindfulness-Based interventions (MBIs) can improve coping, impulsivity, emotion regulation, and executive function although no MBIs tailored for YEH have been tested.

Methods: We conducted a pilot attention-control randomized trial to test the feasibility and acceptability of an adapted MBI,.b4me (pronounced dot be for me), for youth living in a homeless shelter. .b4me is a five-session MBI adapted to address the unique considerations of YEH. We randomized youth to.b4me or the control condition, Healthy Topics. Each curriculum comprised 5 h-long group lessons delivered by trained facilitators. Pre- and post-lesson assessments were collected, as well as baseline, immediate-, 3- and 6-month post-follow-ups. Benchmarks for feasibility and acceptability were set a priori, and survey measures to assess emotional and psychological well-being were tested for feasibility and appropriateness of using these measures in future trials among this population and in a shelter setting.

Results: The mean age of participants (N = 90) was 21.5 years old, with the majority identifying as male (62.2%), non-Hispanic (71.1%), black (50.0%), and heterosexual (55.6%). All a priori feasibility and acceptability benchmarks were surpassed and the reliability of most of the emotional and psychological well-being measures was confirmed.

Conclusion: This study demonstrates that an MBI tailored for YEH, .b4me, is acceptable, and it is feasible to conduct a pilot attention control randomized trial with YEH living in a shelter despite major environmental obstacles.

Introduction

Up to 4.2 million youth experience homelessness in the US (Morton et al., 2017). Among high school students across the US, 2.7% experience unstable housing according to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) (McKinnon, 2023). Those who do are more likely to engage in risk behaviors, including risky sexual behaviors, substance use, and suicide ideation and attempts. The challenges they face lead to a disparate burden of adverse health outcomes including death, suicide, substance use, overdose, pregnancy, HIV/STIs, and unmet mental health needs (Cauce et al., 2000; Doroshenko et al., 2012; Edidin et al., 2012; Grant et al., 2007; Kulik et al., 2011; Rosenthal et al., 2008; Smid et al., 2010). Youth experiencing homelessness (YEH) often have difficult family situations and histories of multiple traumas: poverty, physical, sexual, and emotional abuse (Gaetz, 2009). Moreover, YEH have high rates of parental addiction, psychiatric disorders, and criminal involvement that compound the trauma and instability experienced during childhood (Gaetz, 2004). The range of emotional and psychological challenges negatively impact their well-being, risk decision-making, emotion regulation, and coping skills. To this end, interventions aiming to increase YEH resilience must use a trauma-informed model that addresses their state of vulnerability, high levels of acute and chronic stress, unstable housing, trauma, and compromised executive functioning (Rew et al., 2001). The chronic stress of homelessness along with prevailing mood and anxiety disorders (Edidin et al., 2012) deflects attention away from disease prevention and healthy behaviors.

While the need for prevention and health promotion interventions tailored to the special considerations of YEH is undeniable, they continue to be understudied and underserved due to a chronically flawed sentiment that they are a challenging population to work with or study (Slesnick et al., 2000). To the contrary, YEH are able to be recruited and retained in intervention research and see improved outcomes when programs are tailored and relevant (Bender et al., 2015; Santa Maria et al., 2024).

Exposure to toxic stress, defined as an experience of strong, frequent, or prolonged stressful events (Shonkoff et al., 2012), is associated with a heightened risk of developmental or psychiatric disorders and health problems, including the development of chronic diseases (Briggs et al., 2013) and changes in brain structure and cognitive function, such as learning, working memory, and executive functioning tasks (Shonkoff et al., 2012). Interventions that simultaneously address both stress and risk behaviors may be more effective at risk prevention (Carmona et al., 2014). To this end, the American Academy of Pediatrics calls for programs to reduce toxic stress early in life to reduce the development of adult diseases and exacerbate health disparities (Shonkoff et al., 2012). Notably, mindfulness has been found to be protective for exposure to early life adversity (Whitaker et al., 2014).

Underlying psychosocial factors in youth should be addressed to support improvements in stress management, increased emotion regulation, and decreased impulsivity to optimize opportunities for behavioral change. Mindfulness-based interventions (MBI) teach mindfulness practices that can enhance self-regulation and self-observation through focused attention in the present moment (Goyal et al., 2014; Sibinga et al., 2011). MBIs that are trauma-informed and demonstrate acceptability may engage more young people than other service and intervention models (Brown and Bender, 2018) and have been found to improve mindful awareness and decrease psychological symptoms (Joss et al., 2024). Although the documentation on the benefits of mindfulness approaches on stress and anxiety reduction in adults is quite established (Goyal et al., 2014), there has been fewer studies conducted with youth, and even fewer with YEH (Grossman et al., 2004; Kabat-Zinn, 1982).

Evidence of the effectiveness of mindfulness approaches in adolescents shows decreased reactivity and increased mindful attention and awareness (Kuyken et al., 2013), enhanced self-regulation and coping among youth (Perry-Parrish et al., 2016), improved mental health and emotional control and reduced post-traumatic stress symptoms in urban youth (Sibinga et al., 2016), and well-being among youth in substance use programs and juvenile detention (Himelstein et al., 2015). Recent advances have led to the development of a neurodevelopmental framework that supports the potential for mindfulness as a self-regulation strategy particularly for young people with compromised self-regulation capacity, as is often the case with highly traumatized groups such as YEH (Kaunhoven and Dorjee, 2017). Reviews of MBIs (Burke, 2010) and meditation practices (Black et al., 2009) in youth suggest that these interventions may lead to reduced depression and anxiety (Zoogman et al., 2015). Other MBIs have found that mindfulness not only improves emotion regulation and well-being among substance-using youth (Himelstein et al., 2015) but it can also reduce symptoms of craving and withdrawal to aid in the treatment of substance use disorders (Lin et al., 2019). Despite the widespread dissemination of MBI strategies (Michalak and Heidenreich, 2018), little evidence exists to support its efficacy and no MBIs have been tailored specifically for YEH despite their high need for stress management, emotion regulation, and impulse control.

Many studies have suggested that MBIs have high levels of acceptability in urban, underserved youth (Mendelson et al., 2010), sexual and gender minority identifying younger adults (Seabra et al., 2024), and YEH (Bender et al., 2015; Grabbe et al., 2012; Santa Maria et al., 2020). According to a study conducted in HIV-positive and at-risk youth, out of those who attended any sessions, 79% participated in most sessions (Sibinga et al., 2011). A meta-analysis found significant effects on mindfulness, executive function, attention, depression, anxiety/stress, and risk behaviors among youth participating in an MBI compared to the control group (Klingbeil et al., 2017; Maynard et al., 2017; Semple et al., 2010; Zoogman et al., 2015). In particular, high acceptability was found among a school-based sample of youth between 12 and 16 years old for .b (“dot-be” which stands for stop and be)—the intervention adapted in the current study; this study also found decreased stress (p = 0.05), with the amount of practice being associated with reduced stress (p = 0.03) (Kuyken et al., 2013). Other significant benefits associated with mindfulness, depression, and anxiety have also been found among in randomized controlled trials (Sibinga et al., 2016; Zoogman et al., 2015).

Among limited evidence testing of an MBI with unhoused young people (N = 97), one prior study found high intervention engagement, uptake of the practices, and significant improvement in observational skills (Bender et al., 2015). Although the intervention improved attention to external and internal stimuli in youth, the findings suggested that tailoring would be beneficial to meet the unique needs of YEH. In a smaller quasi-experimental study, an MBI was delivered to YEH over 8 weeks (Burke, 2010; Viafora et al., 2015). Although the differences were nonsignificant, YEH reported improved emotional well-being, a greater likelihood of using mindfulness practices at school to deal with difficult emotions, and a greater likelihood of recommending mindfulness to their friends. Many YEH-serving organizations are utilizing mindfulness strategies despite the lack of rigorous data from randomized trials among YEH. Despite promising preliminary findings and strong rationale that interventions for highly stressed populations need to address stress as an antecedent of risk behavior (Brown et al., 2007; Chiesa et al., 2013; Teper and Inzlicht, 2013), well-designed trials are needed to assess if MBIs tailored to YEH are feasible and acceptable.

Building on the promising results of the .b pilot study (Santa Maria et al., 2023) the goal of this study was to conduct a feasibility pilot attention control randomized trial of an adapted MBI, .b4me (pronounced dot be for me), among YEH ages 18–25 living in a shelter. .b4me was adapted using ADAPT-ITT in collaboration with YEH and health and social services providers (Santa Maria et al., 2023). .b4me, was adapted from the original .b curriculum during the first phase of the study and is described in a separate publication (Santa Maria et al., 2023). Key curriculum concepts and strategies include paying attention, fostering curiosity, self-compassion, understanding rumination and catastrophizing, staying in the present, recognizing thoughts as separate from self, responding instead of reacting, understanding stress and its impact, accepting negative and positive experiences, moving mindfully, and using mindfulness in everyday life. In summary, adaptations to the curriculum and delivery modality were made to approximate the average length of stay in the shelter, integrate trauma-informed approaches, increase the diversity of images used by race/ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, and gender identity, and increase the relevance of the audio-visual components to modern youth culture.

Methods

This research study was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects. A data safety monitoring board was assembled and met quarterly after enrollment began to monitor participant recruitment, accrual and retention rates, and to assess for any adverse events or protocol deviations.

Participants

Ninety YEH aged 18–25 were recruited using convenience sampling from the largest shelter serving unaccompanied young adults in one large metropolitan area in the U.S. South. The shelter offers a temporary place to stay, a transitional living program, comprehensive case management, life skills, educational/vocational training, and health and mental healthcare. Eligibility criteria included being 18–25 years old, able to speak, read, and understand English, expected to stay at the shelter for at least 3 weeks (the duration of the intervention), and could read English (scored over four on the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine [REALM] health literacy assessment) at the time of recruitment. This protocol for low literacy has been used successfully in our previous studies with homeless youth and did not result in any exclusions. Participants were excluded if there was concern that they were under the influence of substances or experiencing heightened mental health symptoms. In these cases, prospective youth were asked to come back at a later time to determine if they were eligible to participate.

Procedure

Study staff visited the shelter about 3 days a week and provided a brief study description during meetings and announcements. Interested youth spoke with staff individually to learn more about the study and be screened for eligibility. Research staff utilized a three-step process for enrollment over the course of several days. Participants were considered officially enrolled in the study if they completed the consent and baseline survey and attended at least one session of the intervention or control sessions. Enrolled participants were issued a smartphone when they attended the third pre-study visit. This tiered enrollment process has been implemented in previous studies to provide ample time to consider participation, to avoid drop-out due to leaving the shelter quickly, and to ensure responsible use of study resources.

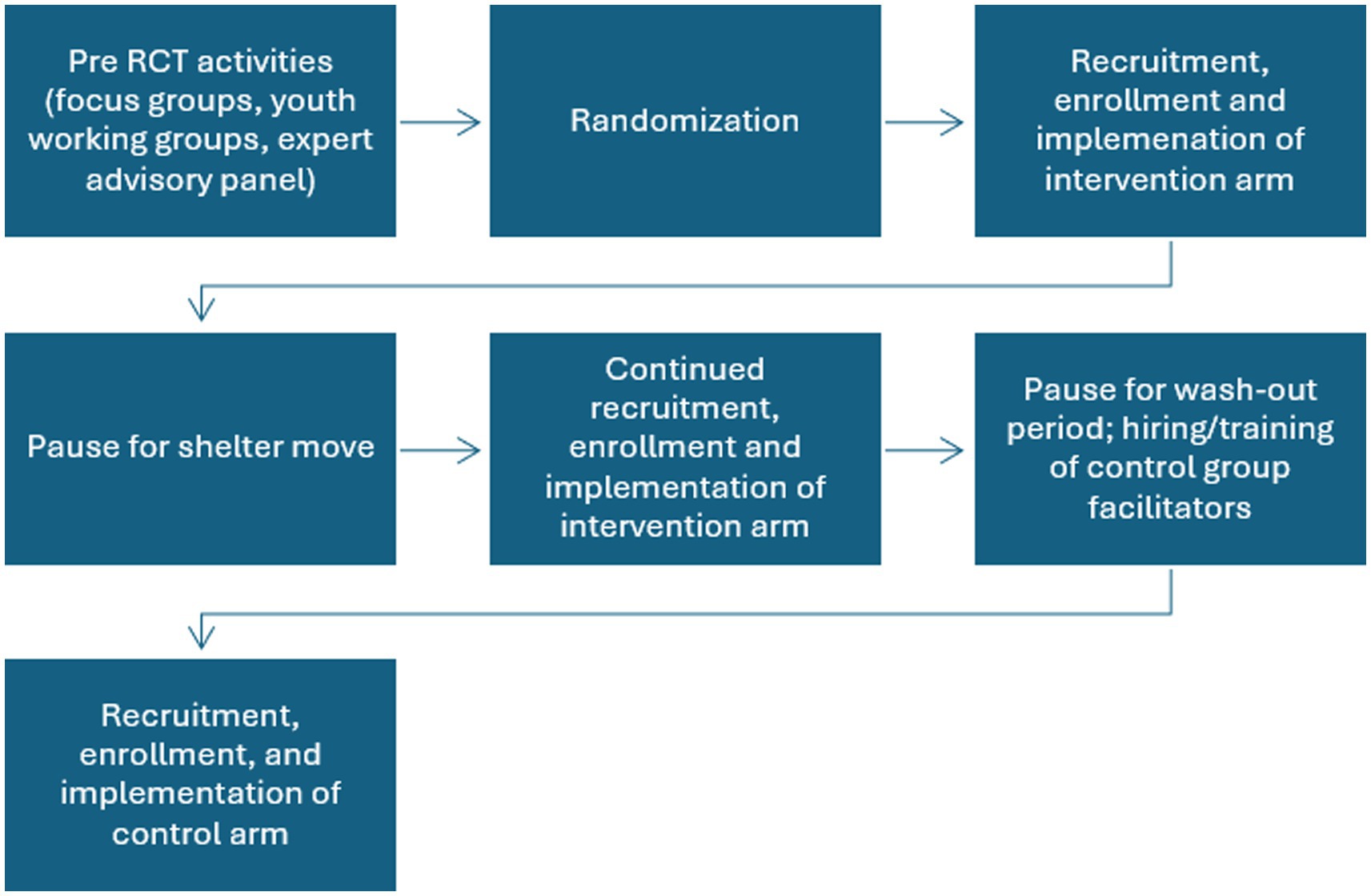

The order of the conditions, not the individual, was randomized in a one-stepped wedge design with the intervention group being offered first followed by the control condition. During the 17 months of recruitment, 5 months were not active due to the shelter being demolished and relocated to a temporary facility and the planned washout period (3 months) between recruitment into the two groups. Once the shelter had reached at least a 50% resident turnover, youth were recruited for the control arm. This was assessed by viewing the resident roster to determine when there was less than 50% of the same residents at the time of enrollment (Figure 1).

The intervention and control condition sessions were held on-site at the shelter 2–4 times a week in the morning, evening after dinner, and on various days of the week. Sessions were offered multiple times to maximize accessibility given the heterogeneity of schedules among sheltered youth. Attendees completed brief pre- and post-assessments at each session and received a $10 gift card for each session attended. Participants also completed follow-up surveys at immediate post, 3-, and 6 months, for which they received a $15 and $20 gift card, respectively. Surveys were administered in person using iPads, and follow-up surveys were administered in person or remotely by sending a link to the study-issued phone to access the survey. Individual exit interviews (N = 18) were conducted after implementation of the intervention or control curricula to collect feedback on study procedures, barriers and facilitators to session attendance, and acceptability of program content and delivery modality. After 18 interviews, no new themes were emerging and saturation was reached.

Three interventionists completed an eight-week mindfulness-based stress reduction course, attended the original .b curriculum training (5-day course), and maintained a personal mindfulness practice for at least 6 months prior to being prepared to deliver .b4me as part of this study. Upon completion of the background training, both interventionists received an orientation of the adapted curriculum .b4me and an overview of all study procedures to prepare for implementation.

The health education program Healthy Topics (HT) adapted from the Glencoe Health Curriculum (McGraw Hill) was modified from its original eight-session format to match the intervention condition delivery period and serve as an active control condition. This curriculum has served as the control condition to similar studies with youth populations (Mendelson et al., 2020; Sibinga et al., 2013; Sibinga et al., 2014). HT was matched to .b4me across session frequency, length, group size, location, timing, and instruction modalities. Topics covered in HT included physical activity, nutrition, managing weight, understanding adolescence, personal care, and avoiding tobacco, alcohol, and drugs. The HT program was led by two trained instructors with backgrounds in health education and experience working with adolescents to avoid contamination of mindfulness strategies across the control condition.

Measures

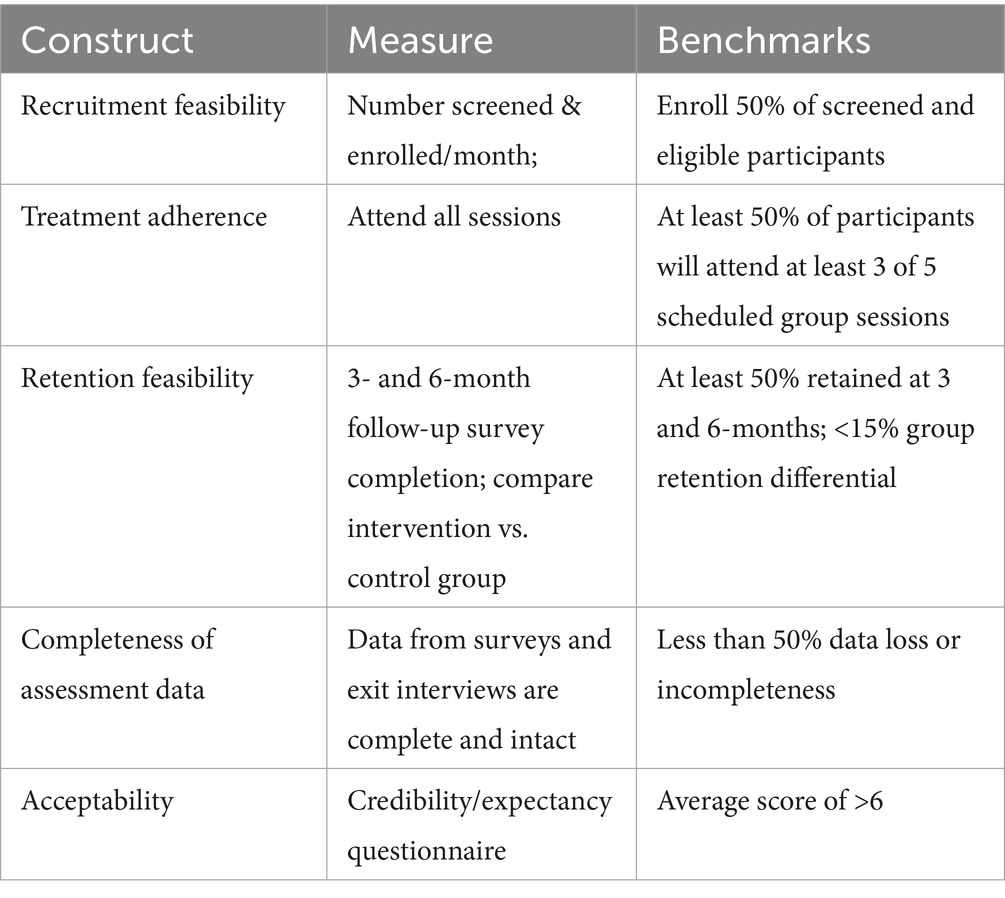

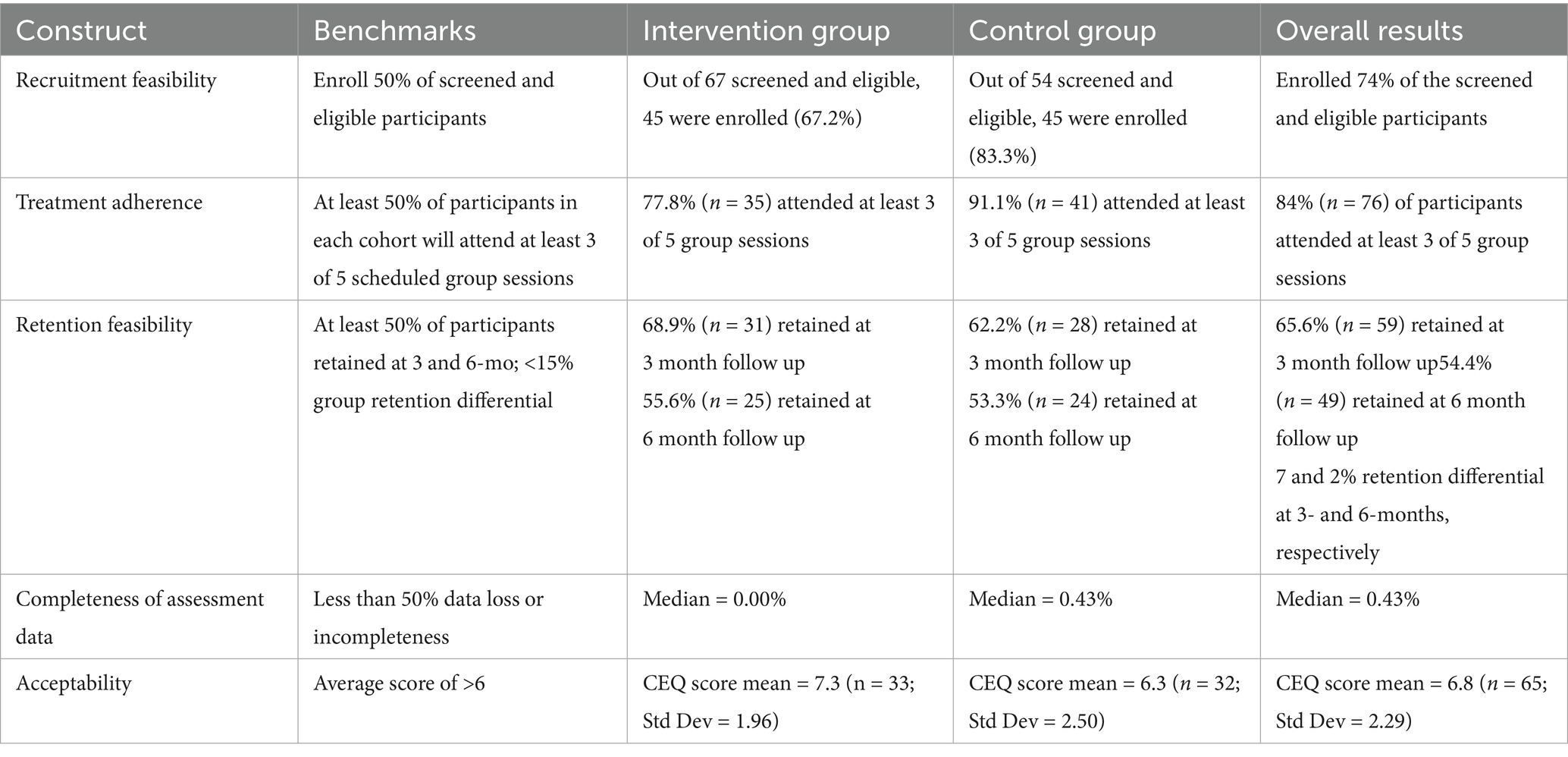

Feasibility and acceptability measures were collected to determine if a priori benchmarks were met (Table 1). Recruitment, treatment adherence, and retention benchmarks were chosen considering the highly variable lengths of stay for young adults in a shelter. The study aimed to enroll 50% of all screened and eligible participants, expose at least 50% of participants to three out of five group sessions, and retain at least 50% of participants at the 3- and 6- months post-follow-up with a group retention differential less than 15%, attain less than 50% of data loss, and achieve over 6 on the credibility and expectancy questionnaire scale (Devilly and Borkovec, 2000). Setting a minimum of three sessions for the participation benchmark was informed by previous studies that found significant intervention effects even without exposure to an entire intervention curriculum (Biegel et al., 2009; Himelstein et al., 2012; Tucker et al., 2017).

Participants completed baseline and follow-up surveys immediately post-intervention and at 3- and 6-months post-intervention. In addition, participants completed very brief assessments immediately before and after each session of the intervention or control curriculum. The baseline survey asked about demographics including age, race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, employment, and education level. A history of homelessness, involvement in the foster care and juvenile justice systems, and experiences of adverse childhood events were also collected.

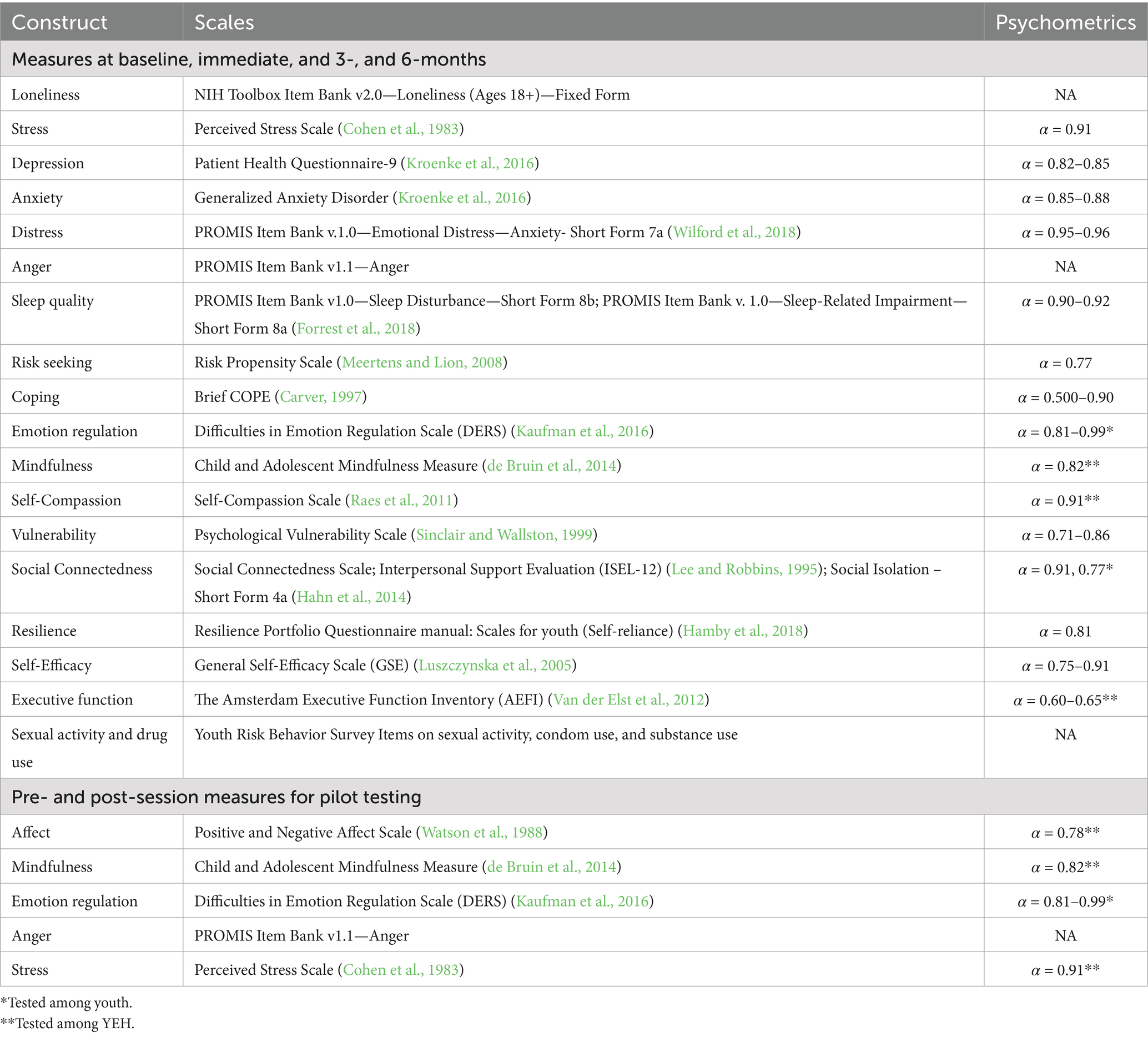

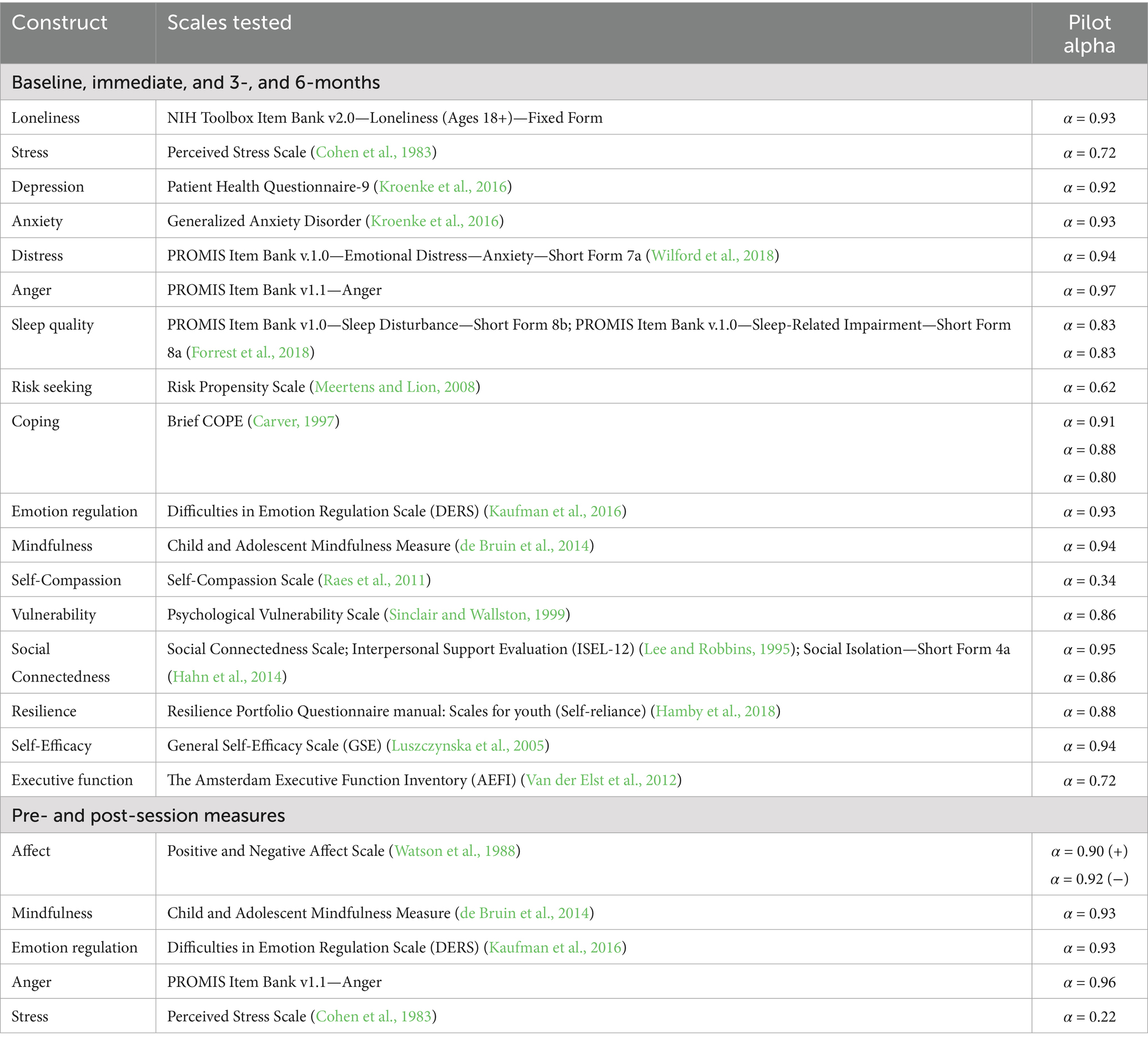

Measures chosen to assess emotional and psychological well-being were informed by the study team, expert advisors, and cognitive interviews with the youth working group. The final baseline, immediate-, 3-, and 6-month follow-up surveys included scales to assess loneliness, stress (PSS), depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD), emotional distress, anger, sleep disturbance/impairment, risk propensity, coping, emotion regulation, mindfulness, self-compassion, psychosocial vulnerability, social connectedness, resilience, social isolation, self-efficacy, executive function, and risk behaviors (see Table 2). The surveys administered pre- and post-session contained the same scales to assess mindfulness, emotion regulation, and anger, a shortened scale to measure stress, and a scale to measure positive and negative affect. The semi-structured exit interview guide was developed to assess the overall experience of participating in the study, expectations and perceived outcomes of the program, facilitators and barriers of attendance, experience with the session facilitators, acceptability of program content and delivery modality, and feedback on outcome measures and survey format and length.

Data analysis

To analyze quantitative data, frequencies and percentages were calculated to determine the rates of recruitment, retention, attendance, and data completeness. Emotional and psychological well-being measures were tested for reliability. As a feasibility study, changes in these measures are outside the scope of this study and not reported here.

Exit interviews were recorded to collect qualitative data and the audio files were transcribed by a third-party HIPAA compliant service. Codes were developed to capture the content discussed. Transcriptions were coded by trained team members who were not directly involved in the intervention delivery or data collection and were grouped according to theme. The investigators summarized themes and identified quotes that exemplified each theme.

Results

Recruitment

From March 2022 to August 2023, 121 individuals were screened, and 118 consented to reach the goal end sample size of 90 participants (45 intervention and 45 control). Youth at the shelter showed high interest in the program. As part of the study design, participants were provided with a study-issued phone to enhance follow-up and retention efforts.

Sample characteristics

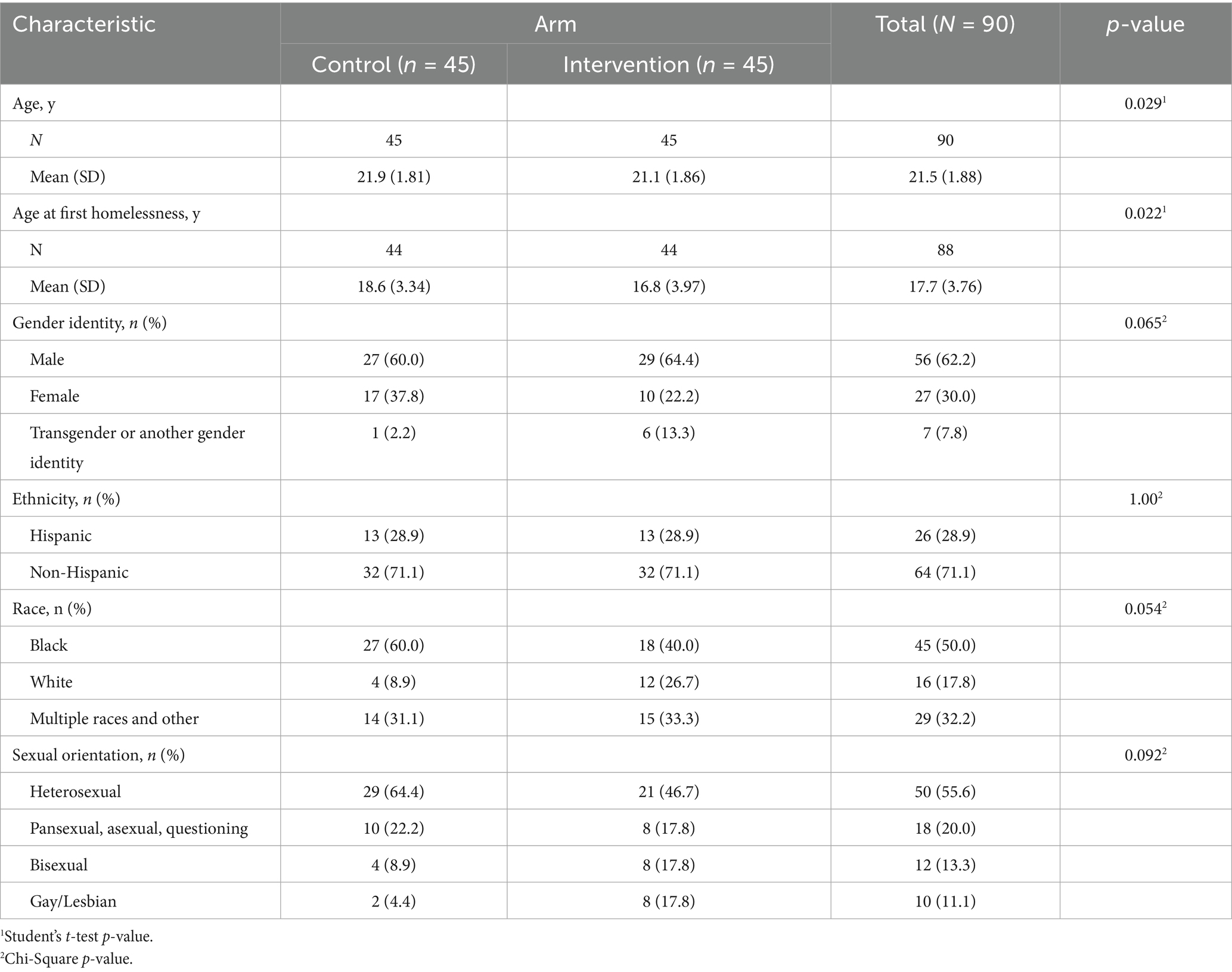

Participants were predominantly male (62.2%), non-Hispanic (71.1%), Black (50.0%), and heterosexual (55.6%). The mean age at enrollment was 21.5 and the mean age at first homelessness was 17.7. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between groups (Table 3).

Intervention arm

Implementation of the intervention began in April 2022. Staff were onsite 66 times over 6 months. Due to the demolition of the shelter, the residents moved to a temporary site in October, 2022, after the implementation of the intervention arm commenced. To allow time for staff and residents to acclimate to their new environment, implementation of the intervention was paused in October, 2022 and resumed in November, 2022. Sessions were provided in semi-private spaces such as a meeting room, library, cafeteria, or shared living space in the mornings and evenings 2–4 times a week depending on shelter and trained facilitator schedule. Participants were not required to attend all sessions within a specific time range to maximize flexibility and participant access to the intervention. Implementation of the intervention arm ended in January, 2023. Thirty-five participants (77.8%) completed over half of the intervention curriculum with 27 (60%) completing the entire curriculum. While three facilitators were trained to deliver the intervention curriculum, one main facilitator delivered most of the sessions due to relocation and availability changes due to the pandemic.

Control arm

The control condition, Healthy Topics was implemented entirely at the temporary shelter between April, 2023 and August, 2023 with staff being onsite 53 times over five consecutive months. Participants in the control arm were not required to attend all classes within a specific time range, similar to the intervention arm. Forty-one participants (91.1%) completed over half of the control curriculum with 24 (53.3%) completing the entire curriculum. Two trained facilitators delivered sessions equally.

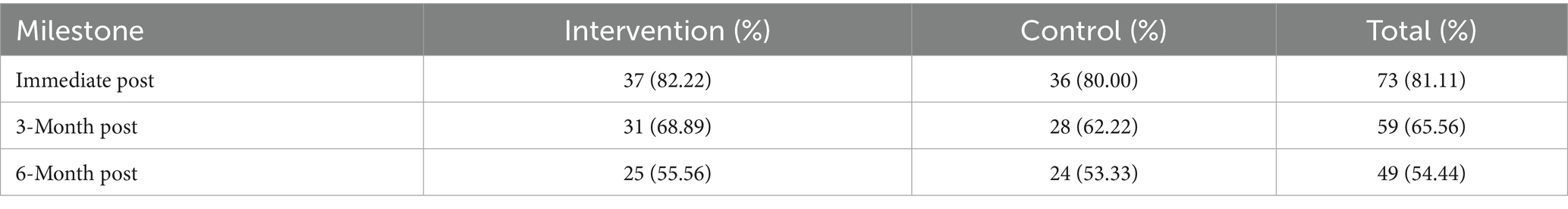

Retention

Follow-up data collection was challenging due to the transient nature of the participants. Twenty-five youth left the shelter during the study period. While youth were able to return to the shelter to participate in the sessions, transportation was a prohibitive factor for those housed through vouchers in apartments that were far from the shelter, or staying with family or friends who lived out of town. Aside from leaving the shelter, additional reasons for not completing the sessions may have been finding a job, enrolling in school or vocational program, or loss of interest. Further, the immediate post-survey was designed to be administered immediately after the last session. However, youth (n = 18) did not participate in the last session. Youth (n = 3) also left the shelter but returned months later for 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Despite these common realities of the lived experience of youth who are unhoused, benchmarks for retention were met (Table 4).

Data completeness

The overall percentage of missing survey items across all surveys being 0.43% (median) for the control participants, 0.00% (median) for the intervention participants, and 0.43% (median) for both groups, which equated to 1 out of 235 items.

Acceptability

The Credibility/Expectancy (n = 33; mean = 7.3; Std Dev = 1.96) score (CEQ) for the intervention group indicated that the adapted curriculum was acceptable. An acceptable CEQ score for the control group (n = 32; mean = 6.3; Std Dev = 1.96) score (CEQ) indicates the control program was also acceptable for this sample. A summary of feasibility and acceptability outcomes are outlined in Table 5.

Outcome measures for pilot testing

To assess the reliability of outcome measures in the baseline and follow-up surveys, Cronbach alpha scores were calculated for all scales and ranged from α = 0.34–0.97 (Table 6). All outcomes were deemed to have acceptable reliability except self-compassion and risk-seeking measures. To assess the reliability of outcome measures in the pre-and post-session surveys, Cronbach alpha scores were calculated for all scales and ranged from α = 0.22–0.96. All outcomes were deemed to have acceptable reliability except the abbreviated stress scale. There were no adverse events or protocol deviations during this study.

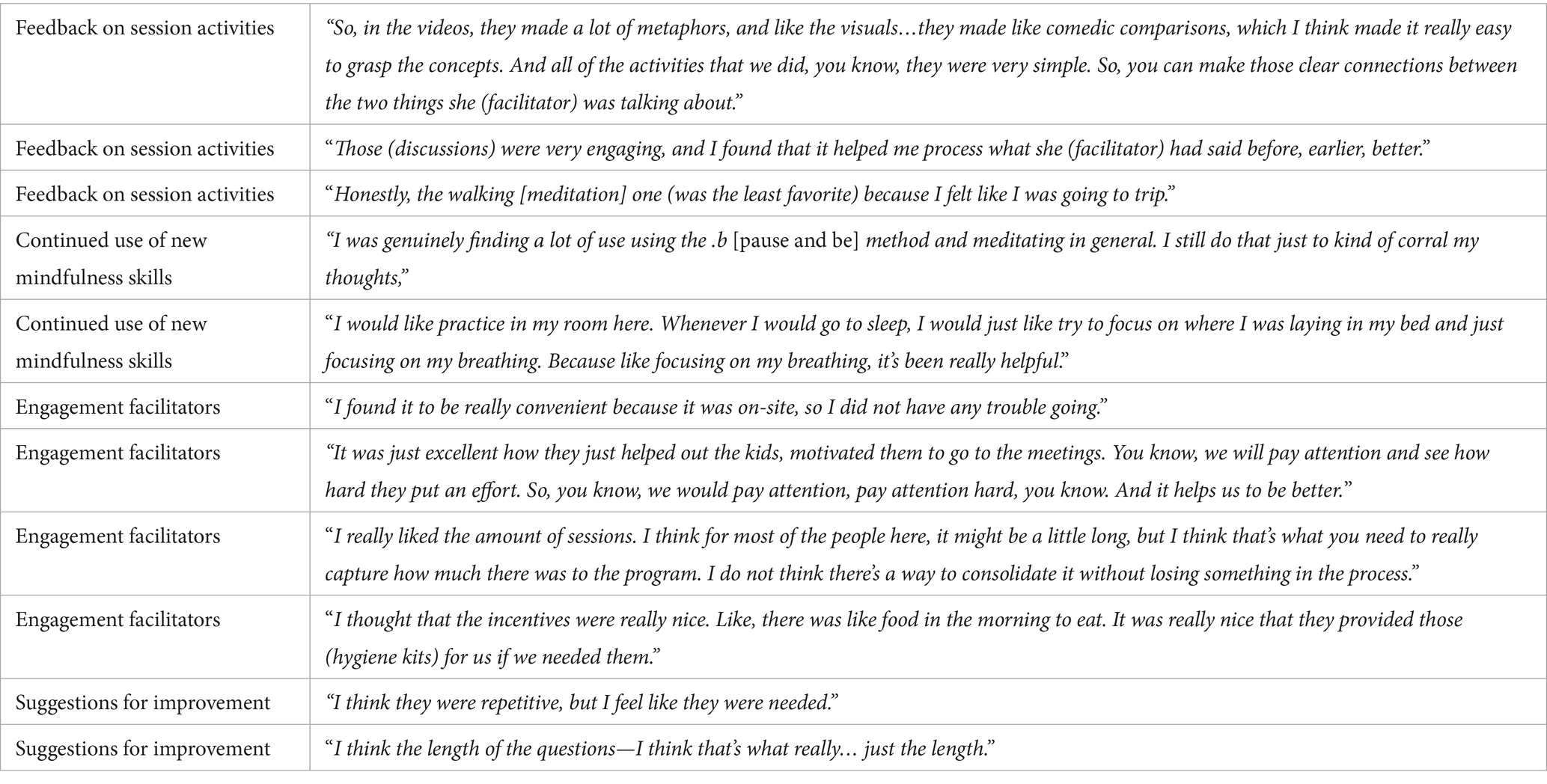

Qualitative findings

Overall, the youth described the usefulness of .b4me and how it helped them with emotion regulation, mindfulness, and coping. Based on the responses in the exit interviews, youth felt that the sessions had benefitted them in many ways. “Well, it’s very interesting. It helped me cope with a lot of things.” Several participants spoke about how the mindfulness practices learned in the intervention helped to clear their minds. One participant mentioned regaining control over their thoughts and said, “Honestly, it was kind of eye-opening to the fact that my brain could work a certain way, and I could learn to tame it.” Another participant described the intervention as “learning to help your brain stop, going back into that primal mode that it was set in for years.” One youth felt that there were also other potential benefits for others. They said, “I feel like people with anxiety disorder could benefit too, just learning how to, like, get a hold on their brain.” When asked the purpose of the study, one participant believed that it was “to spread awareness of your brain and how it works and how to fix what has been wired into it.” In general, the study sessions seemed to be positively received. As stated by one of the participants, “It helped me out throughout the whole session,… before I even got into the sessions and stuff, I just felt angry most of the time. You know, it helped me learn new skills, how to cope with it, and…better myself.” Additional themes are summarized in Table 7.

There were various activities, including videos, worksheets, discussions, and various mindfulness/meditation practices. Participants were asked about their least and most favorite activities. They described how they felt about the session content and their thoughts on the curriculum activities. Based on their responses, several participants seemed to enjoy the videos. A few participants commented on how they found the discussions beneficial to understanding the lesson. In relation to the practices taught, mixed responses were received. Many youth reported how they continued to use the practices that they learned. When youth were asked about what factors facilitated their attendance, self-determination and motivation were common themes. Completing the sessions seemed to also provide some participants with a feeling of motivation and a sense of accomplishment. Often youth residing in the shelter were either attending job interviews, counseling sessions, meetings with their case workers, or were employed. To cater to their different schedules, the sessions took place within the shelter and were repeated on various days and times in order to give participants a chance to attend in case they were not available. While this did not emerge in the interviews, it was clearly observed by the study staff and interventionist as a barrier to attendance. The youth also talked about how their experience with the interventionists helped to motivate them as well. Several of the participants reported that the interventionists created a comfortable environment in which they could be themselves.

Regarding the session logistics and their thoughts about the number, time of day, and length of sessions, the responses. Some youth agreed that the length and number of sessions were satisfactory. Overall, the participants appreciated the incentives provided during the sessions. Participants also shared that they enjoyed the food, coffee, and hygiene kits that were provided during the sessions. When participants were asked to share their feedback on how the program could be improved, several responses centered around the length of the baseline and follow-up surveys. Many agreed that the baseline and follow-up surveys were lengthy and had many questions that seemed repetitive yet were acceptable. When asked if they felt the same way about the pre- and post-session surveys, the participants reported the opposite. Many others agreed with this critique. In regard to other aspects of the study, participants were in agreement with each other about keeping everything else the same.

Discussion

The qualitative data collected from the exit interviews coupled with the quantitative data on feasibility benchmarks suggests overall success and acceptance of delivering .b4me in a one-site randomized trial. Feasibility and acceptability benchmarks were surpassed in this pilot and valuable information was gathered about recruitment, implementation, treatment adherence, study retention, assessment data collection, and content acceptability. This was, in part, due to the commitment of the shelter and study staff and the trusting relationship built with participants throughout the study. This allowed the team to reach participants who may have left the shelter using the extensive follow-up strategies developed to support retention including having multiple contacts for each participant and permission to contact them using social media.

Regarding outcome measures, the brief, pre- and post-session assessments were time-consuming despite being limited to only include the priority measures. Because attendees took the assessments at different paces or a participant may have arrived late delaying the start of the lesson, some attendees left before the lesson started. Therefore, the pre/post-session surveys need to be more brief and nondisruptive and be able to be completed in less than 5 min. Strategies that assisted with data completeness of these surveys included having a backup Wi-Fi hotspot to overcome any disruptions in the shelter-based Wi-Fi and having a minimum of three staff assisting with survey completion and classroom management.

Three measures that will need to be adjusted in future studies include self-compassion, risk-seeking, and stress as the measures used did not meet a priori benchmarks for reliability. Therefore, these measures will need to be revisited in subsequent studies and their outcomes here should not be interpreted as valid. One solution would be to expand the Perceived Stress Scale to the 10-item verses the four-item scale and identify and test other self-compassion measures with this population. Further, the entire survey will need to be streamlined to reduce the current length as suggested by participant feedback.

While every effort was made to implement the intervention and control arm similarly, external events throughout the duration of the study caused interruptions and changes in the environment during implementation, including the COVID-19 pandemic-related restrictions of access to the shelter and demolition and relocation of the main shelter recruitment site. The pandemic delayed the initiation of the study and changed the a priori schedule of structured activities at the shelter. To reduce the spread of the infection within the shelter residents and staff, the shelter restricted outside visitors, causing additional delays in offering the sessions across the intervention and control arms. Additionally, several key shelter staff left during the pandemic. Further, the shelter was demolished and temporary housing was found across town. The space for group activities at the temporary location was much smaller and less ideal than the shelter space. Since youth often had to give up work hours to attend the sessions, it became critical to also provide an incentive for session attendance to offset the cost to the participant in missed work and potential income.

Despite the numerous challenges faced, youth were very interested in participating in the study. It is possible this was enhanced by the receipt of a study-issued phone and incentives for which participants were eligible. While this is an attractive incentive and critical to maintaining contact with a highly transient population, measures needed to be taken to ensure participants fully considered the commitment required for study participation. The step-wise enrollment process enabled staff to give potential participants adequate time to consider study expectations prior to fully enrolling in the study.

The COVID-19 pandemic created numerous challenges to implementing the study procedures and timeline. The study implementation was delayed as the shelter enforced restricted building access to reduce the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks among residents and staff. Coupled with the planned shelter demolition and the subsequent move to a temporary location, the study activities were adjusted several times during the study period. One such adjustment was increasing the number of times a session was offered to allow participants maximum flexibility to participate while also meeting their immediate needs of securing employment and education, keeping their appointments for needed healthcare, and meeting their mental health needs. YEH were often new to the shelter and adjusting to being newly homeless, a new environment, needing to manage appointments with case managers, obtaining essential documents such as IDs, and needing to secure employment or enroll in school. Prior studies in similar populations have found that even with less than full attendance, participants can experience improvements in substance use and sexual risk behavior (Biegel et al., 2009; Himelstein et al., 2012; Tucker et al., 2017). Despite these competing priorities, participant incentives and full shelter collaboration allowed the study to continue successfully reaching the a priori benchmarks for implementation and treatment adherence. This finding reiterates that enhancing flexibility in delivering interventions (e.g., offering many touchpoints, variety of days and times) to populations that experience extreme challenges can improve adherence.

While data collection can be challenging among YEH, with a priori efforts such as comprehensive retention and follow-up procedures and study-issued phones, it is possible to meet a priori benchmarks. Further, extreme and unanticipated challenges, such as the global pandemic and the demolition of the main recruitment and implementation site, can be overcome with strong community partnerships, study team commitment, and trust-building with participants (Santa Maria et al., 2024).

Both the quantitative and qualitative data indicate that .b4me is acceptable to YEH who are residing in a shelter. The youth highlighted the importance of the relatability of the videos used and created. They felt that the session discussions were understandable and aligned well with the session lessons. They appreciated the diverse teaching modalities used and the variability of activities provided. Youth thought that the sessions were about the right number and length and that the surveys were reasonable.

Limitations and future directions

While this pilot resulted in valuable data to inform a randomized control trial, there were several limitations. The COVID-19 pandemic and demolition of the shelter may have impacted adherence to the intervention and retention that we were unable to fully measure. Additionally, due to unforeseen circumstances, two facilitators trained to deliver .b4me was unable to continue working with the study. As a result, only one facilitator delivered the vast majority of the intervention sessions while two facilitators delivered the control condition. Another possible limitation was the use of compensation for session attendance. Since attending a session often meant not attending another obligation such as another life skills class or work and it is standard practice that YEH get compensated for the various activities that they participate in at a shelter, this study also provided incentives. This strategy could limit the scalability of the intervention. However, it does approximate universal shelter-based operations.

This one-site, attention control randomized trial demonstrated that an adapted MBI, .b4me, is feasible and acceptable among sheltered YEH. We were able to recruit, implement, and retain YEH in the study as designed with minor adjustments to account for the challenges experienced during the pandemic and with the shelter demolition. The strong collaborative partnership with the shelter staff, experienced study staff, flexible intervention delivery schedule, highly engaged youth, and strong support from the mindfulness curriculum creators, allowed for the study to succeed. Given the challenges experienced, future studies are needed to determine the feasibility of conducting a multi-site randomized trial to demonstrate that an adequate sample size can be recruited and retained prior to conducting a fully powered randomized trial to test the efficacy of .b4me.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants.

Author contributions

DS: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Resources, Validation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization. PC: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation. ES: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. KB: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. EJ: Writing – original draft. WL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JJ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (award number 5R34AT010672).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the youth who participated in this study, Covenant House Texas, and Mindfulness in Schools.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bender, K., Begun, S., DePrince, A., Badiah, H., Brown, S., Hathaway, J., et al. (2015). Mindfulness intervention with homeless youth. J. Soc. Soc. Work Res. 6, 491–513. doi: 10.1086/684107

Biegel, G. M., Brown, K. W., Shapiro, S. L., and Schubert, C. M. (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for the treatment of adolescent psychiatric outpatients: a randomized clinical trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 77, 855–866. doi: 10.1037/a0016241

Black, D. S., Milam, J., and Sussman, S. (2009). Sitting-meditation interventions among youth: a review of treatment efficacy. Pediatrics 124, e532–e541. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3434

Briggs, M. A., Granado-Villar, D. C., Gitterman, B. A., Brown, J., Chilton, L. A., Cotton, W. H., et al. (2013). Providing care for children and adolescents facing homelessness and housing insecurity. Pediatrics 131, 1206–1210. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0645

Brown, S. M., and Bender, K. (2018). “Mindfulness approaches for youth experiencing homelessness” in Mental health and addictions interventions for youth experiencing homelessness: Practical strategies for front-line providers. eds. S. A. Kidd, N. Slesnick, T. Frederick, J. Karabanow, and S. Gaetz (Toronto, ON: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press), 31–43.

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., and Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychol. Inq. 18, 211–237. doi: 10.1080/10478400701598298

Burke, C. A. (2010). Mindfulness-based approaches with children and adolescents: a preliminary review of current research in an emergent field. J. Child Fam. Stud. 19, 133–144. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9282-x

Carmona, J., Slesnick, N., Guo, X., and Letcher, A. (2014). Reducing high risk behaviors among street living youth: outcomes of an integrated prevention intervention. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 43, 118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.05.015

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med. 4, 92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6

Cauce, A. M., Paradise, M., Ginzler, J. A., Embry, L., Morgan, C. J., Lohr, Y., et al. (2000). The characteristics and mental health of homeless adolescents: age and gender differences. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 8, 230–239. doi: 10.1177/106342660000800403

Chiesa, A., Serretti, A., and Jakobsen, J. C. (2013). Mindfulness: top-down or bottom-up emotion regulation strategy? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 33, 82–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.006

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., and Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 24, 385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404

de Bruin, E., Zijlstra, B. J., and Bogels, S. M. (2014). The meaning of mindfulness in children and adolescents: further validation of the child and adolescent mindfulness measure (CAMM) in two independent samples from the Netherlands. Mindfulness 5, 422–430. doi: 10.1007/s12671-013-0196-8

Devilly, G. J., and Borkovec, T. D. (2000). Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 31, 73–86. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7916(00)00012-4

Doroshenko, A., Hatchette, J., Halperin, S. A., MacDonald, N. E., and Graham, J. E. (2012). Challenges to immunization: the experiences of homeless youth. BMC Public Health 12:338. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-338

Edidin, J. P., Ganim, Z., Hunter, S. J., and Karnik, N. S. (2012). The mental and physical health of homeless youth: a literature review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 43, 354–375. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0270-1

Forrest, C. B., Meltzer, L. J., Marcus, C. L., de la Motte, A., Kratchman, A., Buysse, D. J., et al. (2018). Development and validation of the PROMIS pediatric sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairment item banks. Sleep 41:zsy054. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy054

Gaetz, S. (2004). Safe streets for whom? Homeless youth, social exclusion, and criminal victimization. Can. J. Criminol. Crim. Justice 46, 423–456. doi: 10.3138/cjccj.46.4.423

Gaetz, S. (2009). Backgrounder: “Who are street youth?”. York University. Availble online at: https://www.homelesshub.ca/resource/who-are-street-youth [Accessed May 21, 2024].

Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E. M., Gould, N. F., Rowland-Seymour, A., Sharma, R., et al. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 174, 357–368. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018

Grabbe, L., Nguy, S. T., and Higgins, M. K. (2012). Spirituality development for homeless youth: a mindfulness meditation feasibility pilot. J. Child Fam. Stud. 21, 925–937. doi: 10.1007/s10826-011-9552-2

Grant, R., Shapiro, A., Joseph, S., Goldsmith, S., Rigual-Lynch, L., and Redlener, I. (2007). The health of homeless children revisited. Adv. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 54, 173–187. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2007.03.010

Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., and Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. A meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 57, 35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7

Hahn, E. A., DeWalt, D. A., Bode, R. K., Garcia, S. F., DeVellis, R. F., Correia, H., et al. (2014). New English and Spanish social health measures will facilitate evaluating health determinants. Health Psychol. 33, 490–499. doi: 10.1037/hea0000055

Hamby, S., Taylor, E., Smith, A., and Blount, Z. (2018). Resilience portfolio questionnaire manual: Scales for youth. In. Sewanee, TN: Life Paths Research Center.

Himelstein, S., Hastings, A., Shapiro, S., and Heery, M. (2012). A qualitative investigation of the experience of a mindfulness-based intervention with incarcerated adolescents. Child Adolesc. Mental Health 17, 231–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00647.x

Himelstein, S., Saul, S., and Garcia-Romeu, A. (2015). Does mindfulness meditation increase effectiveness of substance abuse treatment with incarcerated youth? A pilot randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness 6, 1472–1480. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0431-6

Joss, D., Teicher, M. H., and Lazar, S. W. (2024). Temporal dynamics and long-term effects of a mindfulness-based intervention for young adults with adverse childhood experiences. Mindfulness, 15, 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s12671-024-02439-x

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 4, 33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3

Kaufman, E. A., Xia, M., Fosco, G., Yaptangco, M., Skidmore, C. R., and Crowell, S. E. (2016). The difficulties in emotion regulation scale short form (DERS-SF): validation and replication in adolescent and adult samples. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 38, 443–455. doi: 10.1007/s10862-015-9529-3

Kaunhoven, R. J., and Dorjee, D. (2017). How does mindfulness modulate self-regulation in pre-adolescent children? An integrative neurocognitive review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 74, 163–184. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.007

Klingbeil, D. A., Renshaw, T. L., Willenbrink, J. B., Copek, R. A., Chan, K. T., Haddock, A., et al. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions with youth: a comprehensive meta-analysis of group-design studies. J. Sch. Psychol. 63, 77–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.006

Kroenke, K., Wu, J., Yu, Z., Bair, M. J., Kean, J., Stump, T., et al. (2016). Patient health questionnaire anxiety and depression scale: initial validation in three clinical trials. Psychosom. Med. 78, 716–727. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000322

Kulik, D. M., Gaetz, S., Crowe, C., and Ford-Jones, E. L. (2011). Homeless youth’s overwhelming health burden: a review of the literature. Paediatr. Child Health 16:e43-47. doi: 10.1093/pch/16.6.e43

Kuyken, W., Weare, K., Ukoumunne, O. C., Vicary, R., Motton, N., Burnett, R., et al. (2013). Effectiveness of the mindfulness in schools Programme: non-randomised controlled feasibility study. Br. J. Psychiatry 203, 126–131. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.126649

Lee, R. M., and Robbins, S. B. (1995). Measuring belongingness: the social connectedness and the social assurance scales. J. Couns. Psychol. 42, 232–241. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.42.2.232

Lin, J., Chadi, N., and Shrier, L. (2019). Mindfulness-based interventions for adolescent health. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 31, 469–475. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000760

Luszczynska, A., Scholz, U., and Schwarzer, R. (2005). The general self-efficacy scale: multicultural validation studies. J. Psychol. 139, 439–457. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.139.5.439-457

Maynard, B. R., Solis, M. R., Miller, V. L., and Brendel, K. E. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions for improving cognition, academic achievement, behavior, and socioemotional functioning of primary and secondary school students. Campbell Syst. Rev. 13, 1–144. doi: 10.4073/CSR.2017.5

McKinnon, I. I. (2023). Experiences of unstable housing among high school students—youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2021. MMWR supplements, 72.

Meertens, R., and Lion, R. (2008). Measuring an individual’s tendency to take risks: the risk propensity scale. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 38, 1506–1520. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00357.x

Mendelson, T., Clary, L. K., Sibinga, E., Tandon, D., Musci, R., Mmari, K., et al. (2020). A randomized controlled trial of a trauma-informed school prevention program for urban youth: rationale, design, and methods. Contemp. Clin. Trials 90:105895. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2019.105895

Mendelson, T., Greenberg, M. T., Dariotis, J. K., Gould, L. F., Rhoades, B. L., and Leaf, P. J. (2010). Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a school-based mindfulness intervention for urban youth. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 38, 985–994. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9418-x

Michalak, J., and Heidenreich, T. (2018). Dissemination before evidence? What are the driving forces behind the dissemination of mindfulness-based interventions? Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 25:60. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12254

Morton, M. H., Dworsky, A., and Samuels, G. M. (2017). Missed opportunities: Youth homelessness in America. National Estimates: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

Perry-Parrish, C., Copeland-Linder, N., Webb, L., and Sibinga, E. M. (2016). Mindfulness-based approaches for children and youth. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 46, 172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2015.12.006

Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., and Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 18, 250–255. doi: 10.1002/cpp.702

Rew, L., Taylor-Seehafer, M., Thomas, N. Y., and Yockey, R. D. (2001). Correlates of resilience in homeless adolescents. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 33, 33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00033.x

Rosenthal, D., Mallett, S., Milburn, N., and Rotheram-Borus, M. J. (2008). Drug use among homeless young people in Los Angeles and Melbourne. J. Adolesc. Health 43, 296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.002

Santa Maria, D., Cuccaro, P., Bender, K., Cron, S., Fine, M., and Sibinga, E. (2020). Feasibility of a mindfulness-based intervention with sheltered youth experiencing homelessness. J. Child Fam. Stud. 29, 261–272. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01583-6

Santa Maria, D., Cuccaro, P., Bender, K., Sibinga, E., Guerrero, N., Keshwani, N., et al. (2023). Adapting an evidence-based mindfulness-based intervention for sheltered youth experiencing homelessness. BMC Complement Med Ther 23:366. doi: 10.1186/s12906-023-04203-5

Santa Maria, D. M., Fernandez-Sanchez, H., Nyamathi, A., Lightfoot, M., Quadri, Y., Paul, M., et al. (2024). Lessons learned from conducting a community-based, nurse-led HIV prevention trial with youth experiencing homelessness: pivots and pitfalls. Public Health Nurs. 41, 806–814. doi: 10.1111/phn.13314

Seabra, D., Gato, J., Petrocchi, N., and do Céu Salvador, M. (2024). Affirmative mindfulness, acceptance, and compassion-based group intervention for sexual minorities (Free2Be): a non-randomized mixed-method study for feasibility with exploratory analysis of effectiveness. Mindfulness 15, 1814–1830. doi: 10.1007/s12671-024-02403-9

Semple, R. J., Lee, J., Rosa, D., and Miller, L. F. (2010). A randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for children: promoting mindful attention to enhance social-emotional resiliency in children. J. Child Fam. Stud. 19, 218–229. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9301-y

Shonkoff, J. P., and Garner, A. S. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of, C., Family, H., Committee on Early Childhood, A., Dependent, C., Section on, D., & Behavioral, P (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 129, e232–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663

Sibinga, E. M., Kerrigan, D., Stewart, M., Johnson, K., Magyari, T., and Ellen, J. M. (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for urban youth. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 17, 213–218. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0605

Sibinga, E. M., Perry-Parrish, C., Chung, S. E., Johnson, S. B., Smith, M., and Ellen, J. M. (2013). School-based mindfulness instruction for urban male youth: a small randomized controlled trial. Prev. Med. 57, 799–801. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.08.027

Sibinga, E. M., Perry-Parrish, C., Thorpe, K., Mika, M., and Ellen, J. M. (2014). A small mixed-method RCT of mindfulness instruction for urban youth. Explore 10, 180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2014.02.006

Sibinga, E. M., Webb, L., Ghazarian, S. R., and Ellen, J. M. (2016). School-based mindfulness instruction: an RCT. Pediatrics 137:2532. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2532

Sinclair, V. G., and Wallston, K. A. (1999). The development and validation of the psychological vulnerability scale. Cogn. Ther. Res. 23, 119–129. doi: 10.1023/A:1018770926615

Slesnick, N., Meyers, R. J., Meade, M., and Segelken, D. H. (2000). Bleak and hopeless no more. Engagement of reluctant substance-abusing runaway youth and their families. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 19, 215–222. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(00)00100-8

Smid, M., Bourgois, P., and Auerswald, C. L. (2010). The challenge of pregnancy among homeless youth: reclaiming a lost opportunity. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 21, 140–156. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0318

Teper, R., and Inzlicht, M. (2013). Meditation, mindfulness and executive control: the importance of emotional acceptance and brain-based performance monitoring. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 8, 85–92. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss045

Tucker, J. S., D’Amico, E. J., Ewing, B. A., Miles, J. N., and Pedersen, E. R. (2017). A group-based motivational interviewing brief intervention to reduce substance use and sexual risk behavior among homeless young adults. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 76, 20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.02.008

Van der Elst, W., Ouwehand, C., van der Werf, G., Kuyper, H., Lee, N., and Jolles, J. (2012). The Amsterdam executive function inventory (AEFI): psychometric properties and demographically corrected normative data for adolescents aged between 15 and 18 years. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 34, 160–171. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2011.625353

Viafora, D. P., Mathiesen, S. G., and Unsworth, S. J. (2015). Teaching mindfulness to middle school students and homeless youth in school classrooms. J. Child Fam. Stud. 24, 1179–1191. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-9926-3

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., and Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54, 1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Whitaker, R. C., Dearth-Wesley, T., Gooze, R. A., Becker, B. D., Gallagher, K. C., and McEwen, B. S. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences, dispositional mindfulness, and adult health. Prev. Med. 67, 147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.07.029

Wilford, J., Osann, K., Hsieh, S., Monk, B., Nelson, E., and Wenzel, L. (2018). Validation of PROMIS emotional distress short form scales for cervical cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 151, 111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.07.022

Keywords: mindfulness, youth, young adults, homelessness, feasibility

Citation: Santa Maria D, Cuccaro P, Sibinga E, Bender K, Jacko E, Liyanage W, Jones J and Cron S (2025) Feasibility of conducting a pilot randomized trial of a mindfulness-based intervention among sheltered young adults experiencing homelessness. Front. Psychol. 16:1649664. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1649664

Edited by:

Michail Mantzios, Birmingham City University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Vanessa Caridad Somohano, United States Department of Veterans Affairs, United StatesAamer Aldbyani, Shandong Xiehe University, China

Copyright © 2025 Santa Maria, Cuccaro, Sibinga, Bender, Jacko, Liyanage, Jones and Cron. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Diane Santa Maria, ZGlhbmUubS5zYW50YW1hcmlhQHV0aC50bWMuZWR1

Diane Santa Maria

Diane Santa Maria Paula Cuccaro

Paula Cuccaro Erica Sibinga

Erica Sibinga Kimberly Bender

Kimberly Bender Ethel Jacko1

Ethel Jacko1 Widumini Liyanage

Widumini Liyanage Jennifer Jones

Jennifer Jones