- 1Interdisciplinary Laboratory for Research, Education and Disability Support - IREDS Lab, Department of Physiotherapy, University of West Attica, Athens, Greece

- 2Department of Emergency Medicine, Athens University Hospital Attikon, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens Medical School, Athens, Greece

- 3Department of Cardiology, Athens University Hospital Attikon, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens Medical School, Athens, Greece

1 Introduction

Dance is described as a phenomenon in which the human body and its movement, that may have a symbolic or aesthetic value within a variable cultural and rhythmical context, are the primary tools for the human expression and communication under artistic, educational, training, recreational, therapeutic, religious, or other purposes (Basso et al., 2020; Elpidoforou, 2016; Elpidoforou et al., 2025). As a physical activity, dance motivates physical, cognitive, psychological, and social individual's integration, while it enhances neuroplasticity and functional autonomy (Dhami et al., 2014; Foster, 2013; Kattenstroth et al., 2010).

As a performing art, dance is closely related to music, since both arts have a common aspect, the dependence upon rhythm (Schrader, 2005). The therapeutic use of music concerns two main domains, Music Therapy (MT) and Music Medicine (MM), or Therapeutic Music (TM). MT refers to the psychotherapeutic use of music, while MM or TM refers to the use of music during conventional therapeutic interventions (Kang et al., 2025; Lee, 2016). Specifically, the American Music Therapy Association defines MT as “the clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music therapy program” (AMTA, 2025). Meanwhile, the British Association for Music Therapy describes it as the psychological clinical music intervention, delivered by allied healthcare professionals registered in music therapy to help people who, due to an injury, illness or disability, have a certain psychological, emotional, cognitive, physical, communicative, and social need (BAMT, 2025). MM or TM refers to the “pre-recorded music listening experiences administered by medical personnel,” who are not registered in MT (Browning et al., 2020; Lee, 2016; Lorek et al., 2023). Both approaches are performed by specially registered healthcare professionals and are indicated for several purposes in clinical practice, such as pain relief (Guetin et al., 2012; Korhan et al., 2014; Lee, 2016; Roy et al., 2012). While the use of different terms in the field of “music interventions in clinical populations” seems to be well established, this does not seem to be the case for “dance interventions in clinical populations”.

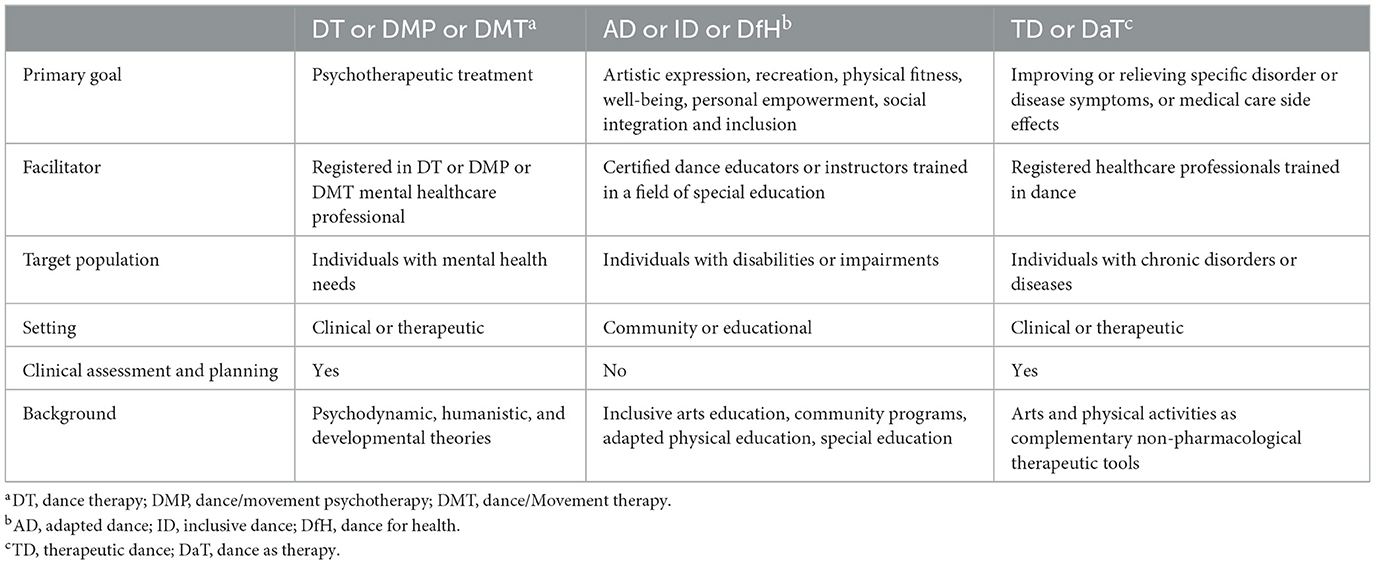

Dance can be applied in populations with various physical, cognitive, sensory, developmental or other impairments or diseases within three different contexts: (i) dance therapy (DT), dance movement psychotherapy (DMP), or dance movement therapy (DMT); (ii) adapted dance (AD), inclusive or dance for health (DfH); and (iii) therapeutic dance (TD) or dance as therapy (DaT).

As the popularity of dance-based interventions grows in healthcare, education, and community settings, it becomes essential to clarify the terminology used to describe the various approaches. This distinction is not merely semantic, but is crucial for the design of future interventional programs, the definition of their outcome measures, and the standardization in clinical, educational, community, and research settings of professional training.

2 Dance therapy or dance movement psychotherapy or dance movement therapy

The terms DT, DMP, or DMT (Table 1) refer to the psychotherapeutic use of movement and dance for the promotion of the emotional, cognitive, physical and social integration of an individual to enhance health and wellbeing, while its practice is facilitated by registered dance-movement therapists or psychotherapists (ADTA, 2025; Koch et al., 2019; Michels et al., 2018; Woolf and Fisher, 2015); the European Association of Dance Movement Therapy also includes the “spiritual integration” to the above list (EADMT, 2025). It is a recognized psychotherapeutic modality associated with diverse professional rights depending on national laws and regulations. There are various clinical indications, such as depression, anxiety, dementia, autism, behavior disorders, addictions, trauma, eating disorders and learning difficulties (Aithal et al., 2021; Biondo, 2023; Bucharova et al., 2020; Karkou et al., 2023, 2019; Moratelli et al., 2023; Savidaki et al., 2020).

The terms DT, DMP, or DMT are used interchangeably by different organizations. DMT is the term used by the American Dance Therapy Association (ADTA, 2025) and the Dance Movement Therapy Association of Australasia (DTAA, 2025), while DMP is the term used by the Association for Dance Movement Psychotherapy of United Kingdom (ADMPUK, 2025). DT is more commonly used in research (Barcelos de Souza et al., 2025; Tomaszewski et al., 2023) and, along with DMT and DMP, refers to the same intervention, although there is not a unique accepted universally name for it (Dunphy et al., 2021).

National dance therapy associations have outlined several pathways for becoming a dance-movement therapist or psychotherapist, ranging from private institutions to university PhD programs (Dunphy et al., 2021). A minimum of 2 years of full-time training is required, including personal psychotherapeutic treatment, clinical training, fieldwork, internships, and supervision, to become a registered dance-movement therapist or psychotherapist (Dunphy et al., 2021).

3 Adapted or inclusive dance or dance for health

The terms AD, ID or DfH (Table 1) refer to a dance program appropriately modified for individuals with movement, sensory, cognitive, developmental or other impairments for their recreation, inclusion, social integration, as well as the enhancement of their health, well-being and physical fitness; the program is delivered by certified dance educators or instructors experienced or trained in a field of special education (Côté-Séguin, 2020; Joung et al., 2024; Lentzari et al., 2023; McGuire et al., 2019; Mendoza-Sanchez et al., 2022). The term Psychomotor dance-based exercise (Guzman-Garcia et al., 2013), has also been used in the literature interchangeably with the above terms. AD, ID or DfH programs are designed to be inclusive, allowing individuals of varying abilities or disabilities to participate in dance practices and enhance their physical activity levels (Atkins et al., 2018; Frable et al., 2025; Schroeder et al., 2017). These programs often focus on the joy of movement, fostering creativity and expression, and building community and self-efficacy among participants (Bungay et al., 2022; Bungay and Jacobs, 2020; McRae et al., 2018). Although they may have therapeutic effects, they are not structured as formal therapy sessions nor include adaptations to meet specific clinical needs, and do not require conduction by licensed therapists (Waugh et al., 2024).

These interventions focus on facilitating an inclusive and creative learning process for individuals of different abilities or disabilities in educational or community settings (Dinold and Zitomer, 2015). Suggested practices include adapting and modifying dance techniques and teaching methods, using inclusive language in instruction, encouraging participation, and fostering social interaction in an individualized, team-oriented approach (Dinold and Zitomer, 2015). Numerous AD, ID or DfH programs (Massó-Guijarro et al., 2025; McGuire et al., 2019), suggested guides for developing an inclusive dance intervention (Duarte Machado et al., 2025), and teacher training programs (ALLPlayDance, 2025; Candoco, 2025; DanceAbility, 2025; ParableDance, 2025; Seedbed, 2025; SENDance, 2025; SENDTraining, 2025) exist. However, the lack of clear professional standards and of a representative international organization highlight the need for the development of a unified framework for these interventions.

4 Therapeutic dance or dance as therapy

The term TD or DaT (Table 1) is often used in the scientific literature in different contexts without having yet been clearly defined. As the most loosely defined category, it encompasses structured dance interventions designed to promote health and wellbeing aspects of clinical populations without necessarily meeting the criteria of DT, DMP, or DMT. DaT, as a term, is used to define dance interventions in clinical populations conducted by healthcare practitioners who are not dance-movement therapists (Tomaszewski et al., 2023). Examples include studies in patients with hypertension (Peng et al., 2024, 2021; Wang et al., 2024), heart failure (Gomes Neto et al., 2014), breast cancer (Karkou et al., 2021), Parkinson's disease (Elpidoforou et al., 2022), multiple sclerosis (Davis et al., 2023), chronic pain (Hickman et al., 2022), Alzheimer's disease (Ruiz-Muelle and Lopez-Rodriguez, 2019), and human immunodeficiency virus (Morgan, 2014).

There are many studies in which the terms DT or DMP or DMT have been used—instead of TD or DaT—to describe a dance program applied to clinical populations with specific therapeutic endpoints, but not using specific DT/DMP/DMT assessment or therapeutic tools, or not being facilitated by appropriate therapists. This leads to spurious conclusions concerning the possible effects of each dance intervention, and it does not allow proper use in clinical and research settings.

Thus, TD or DaT could be defined as the complementary non-pharmacological therapeutic use of dance for the improvement or relief of symptoms related to a disorder or disease–not necessarily mental – or symptoms that appear as side effects of medical care, and is facilitated by registered healthcare practitioners trained in dance (Bognar et al., 2017; Brito et al., 2021; Bruyneel, 2019; Elpidoforou et al., 2022; Karkou et al., 2021). The above definition is closely related to the existing definition of TM or MM, that differentiates it from MT (Browning et al., 2020; Kang et al., 2025; Lee, 2016; Lorek et al., 2023), as previously stated. According to that, both TM or MM and TD or DaT are complementary, non-pharmacological, arts-based interventions delivered by registered healthcare practitioners in clinical contexts for non-psychotherapeutic purposes.

These interventions aim to use dance as a complementary non-pharmacological therapeutic tool in clinical settings, facilitated by healthcare practitioners with non-psychotherapeutic training backgrounds (Tomaszewski et al., 2023). According to the above, the context determines if the purpose of a dance intervention is basically psychotherapeutic, therapeutic for specific disorder or disease symptoms, or non-therapeutic. Thus, several programs and teacher training programs could be delivered as TD or DaT interventions under the appropriate context (DfPD, 2025; McRae et al., 2018; WSU, 2025). However, no professional standards have been clearly established yet. The development of an appropriate consensus on these standards could clarify the role of TD or DaT professionals.

5 Discussion and future directions

Each of the three different dance-based intervention categories contributes uniquely to human health and experience and may offer profound benefits across diverse populations. However, clarity in terminology is crucial for refining practice, advancing research, and ensuring ethical service delivery. Recognizing the differences among these approaches allows us to better harness their potential.

The question that arises is what practical recommendations could be derived from the above clarified definitions. As noted above, while content matters, context plays the principal role in the case of dance interventions for clinical populations. Each dance intervention may have a psychotherapeutic purpose, a complementary therapeutic purpose targeting specific disease or disorder symptoms, or a non-therapeutic purpose. Accordingly, the primary aim and the facilitator's professional background determine the category to which a given dance intervention belongs. Thus, content seems to serve context and not vice versa. We recommend the use of the terms DT or DMP or DMT in the case of a mental health care professional registered in DT or DMP or DMT and in the context of a primary psychotherapeutic goal. Instead, we recommend the use of the terms AD or ID or DfH in the case of a certified dance educator or instructor with a further training in a field of special education and in the context of a primary goal of artistic expression, recreation, physical fitness, well-being, personal empowerment, or social integration and inclusion. Finally, we recommend the use of the terms TD or DaT in the case of a registered healthcare practitioner with additional training in dance in the context of facilitating a dance intervention with a primary goal of improving or relieving specific disorder or disease symptoms, or medical care side effects.

Author contributions

ME: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft. EP: Writing – review & editing. JP: Writing – review & editing. DF: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

ADMPUK (2025). What is Dance Movement Psychotherapy? Association for Dance Movement Psychotherapy UK. Available online at: https://admp.org.uk/what-is-dance-movement-psychotherapy/ (Accessed August 10, 2025).

ADTA (2025). What is Dance/Movement Therapy? American Dance Therapy Association. Available online at: https://adta.memberclicks.net/what-is-dancemovement-therapy (Accessed August 10, 2025).

Aithal, S., Moula, Z., Karkou, V., Karaminis, T., Powell, J., and Makris, S. (2021). A systematic review of the contribution of dance movement psychotherapy towards the well-being of children with autism spectrum disorders. Front. Psychol. 12:719673. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.719673

ALLPlayDance (2025). Join ALLPlay Dance. Monash University. Available online at: https://www.monash.edu/allplaydance/join-allplay-dance (Accessed August 12, 2025).

AMTA (2025). What is Music Therapy? American Music Therapy Association. Available online at: https://www.musictherapy.org/about/musictherapy/ (Accessed August 11, 2025).

Atkins, R., Deatrick, J. A., Bowman, C., Bolick, A., McCurry, I., and Lipman, T. H. (2018). University community partnerships using a participatory action research model to evaluate the impact of dance for health. Behav. Sci. 8:113. doi: 10.3390/bs8120113

BAMT (2025). What is Music Therapy? British Association for Music Therapy. Available online at: https://www.bamt.org/music-therapy/what-is-music-therapy (Accessed August 11 2025).

Barcelos de Souza, J. C., da Silveira, J., de Bem Fretta, T., Gil, P. R., and de Azevedo Guimaraes, A. C. (2025). What are the effects of free dance and dance therapy on self-esteem, anxiety, body image and depressive symptoms of women undergoing breast cancer surgery? A randomized clinical trial. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 42, 1159–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2025.03.004

Basso, J. C., Satyal, M. K., and Rugh, R. (2020). Dance on the brain: enhancing intra- and inter-brain synchrony. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 14:584312. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2020.584312

Biondo, J. (2023). Dance/movement therapy as a holistic approach to diminish health discrepancies and promote wellness for people with schizophrenia: a review of the literature. F1000Res. 12:33. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.127377.1

Bognar, S., DeFaria, A. M., O'Dwyer, C., Pankiw, E., Simic Bogler, J., Teixeira, S., et al. (2017). More than just dancing: experiences of people with Parkinson's disease in a therapeutic dance program. Disabil. Rehabil. 39, 1073–1108. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1175037

Brito, R. M. M., Germano, I. M. P., and Severo Junior, R. (2021). Dance and movement as therapeutic processes: historical context and comparisons. (Danca e movimento como processos terapeuticos: contextualizacao historica e comparacao entre diferentes vertentes). Hist. Cienc. Saude. Manguinhos. 28:146–165. (in Portuguese). doi: 10.1590/s0104-59702021000100008

Browning, S. G., Watters, R., and Thomson-Smith, C. (2020). Impact of therapeutic music listening on intensive care unit patients: a pilot study. Nurs. Clin. North. Am. 55, 557–569. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2020.06.016

Bruyneel, A. V. (2019). Effects of dance activities on patients with chronic pathologies: scoping review. Heliyon 5:e02104. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02104

Bucharova, M., Mala, A., Kantor, J., and Svobodova, Z. (2020). Arts therapies interventions and their outcomes in the treatment of eating disorders: scoping review protocol. Behav. Sci. 10:188. doi: 10.3390/bs10120188

Bungay, H., Hughes, S., Jacobs, C., and Zhang, J. (2022). Dance for Health: the impact of creative dance sessions on older people in an acute hospital setting. Arts Health 14, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2020.1725072

Bungay, H., and Jacobs, C. (2020). Dance for Health: the perceptions of healthcare professionals of the impact of music and movement sessions for older people in acute hospital settings. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 15:e12342. doi: 10.1111/opn.12342

Candoco (2025). Candoco Dance Company Teacher Training. Inclusive Pedagogy for Teachers, Artists and Community Practitioners. Candoco Dance Company. Available online at: https://candoco.co.uk/learning-and-development/teacher-training/ (Accessed August 12, 2025).

Côté-Séguin, É. (2020). Introductory Guide to Adapted Dance. Montréal, QC, Canada: National Centre For Dance Therapy. Les Grands Ballets Canadiens de Montréal.

DanceAbility (2025). Dance Ability International Teacher Trainings. Dance Ability International. Available online at: https://www.danceability.com/teacher-certification (Accessed August 12, 2025).

Davis, E., Webster, A., Whiteside, B., and Paul, L. (2023). Dance for multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Int. J. MS Care. 25, 176–185. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2022-088

DfPD (2025). Dance for Parkinson's Disease. Train With Us. Mark Morris Dance Group. Available online at: https://danceforparkinsons.org/train-with-us/ (Accessed August 12, 2025).

Dhami, P., Moreno, S., and DeSouza, J. F. (2014). New framework for rehabilitation - fusion of cognitive and physical rehabilitation: the hope for dancing. Front. Psychol. 5:1478. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01478

Dinold, M., and Zitomer, M. (2015). Creating opportunities for all in inclusive dance. Palaestra. 29, 45–50. doi: 10.18666/PALAESTRA-2015-V29-I4-7180

DTAA (2025). What is Dance Movement Therapy? Dance Movement Therapy Association of Australasia Incorporated. Available online at: https://dtaa.org.au/therapy/ (Accessed August 10, 2025).

Duarte Machado, E., Miller, L., Nicholas, J., Cross, J., Orr, R., and Cole, M. H. (2025). Developing an inclusive dance guide for children with cerebral palsy: a co-design process and initial feasibility study. Health Expect. 28:e70304. doi: 10.1111/hex.70304

Dunphy, K., Federman, D., Fischman, D., Gray, A., Puxeddu, V., Zhou, T. Y., et al. (2021). Dance therapy today: an overview of the profession and its practice around the world. CAET 7, 158–186. doi: 10.15212/CAET/2021/7/13

EADMT (2025). What is Dance Movement Therapy (DMT)? European Association of Dance Movement Therapy. Available online at: https://eadmt.com/what-is-dance-movement-therapy-dmt (Accessed August 11, 2025).

Elpidoforou, M. (2016). “Types of dance: steps and positions,” in Overuse Injuries in Dancers, ed. A. Angoules (Foster City, CA: OMICS Group eBooks), 1–9.

Elpidoforou, M., Bakalidou, D., Drakopoulou, M., Kavga, A., Chrysovitsanou, C., and Stefanis, L. (2022). Effects of a structured dance program in Parkinson's disease. A Greek pilot study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 46:101528. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101528

Elpidoforou, M., Grimani, I., Papadopoulou, M., Papagiannakis, N., Bougea, A., Simitsi, A. M., et al. (2025). An In-person and online intervention for parkinson disease (UPGRADE-PD): protocol for a patient-centered and culturally tailored 3-arm crossover trial. JMIR. Res. Protoc. 14:e65490. doi: 10.2196/65490

Foster, P. P. (2013). How does dancing promote brain reconditioning in the elderly? Front. Aging Neurosci. 5:4. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00004

Frable, P. J., Wagner, T. L., Bratton, B. D., and Howe, C. J. (2025). Texas dance for health: mixed methods pilot study promoting physical activity among older adults. J. Commun. Health Nurs. 42, 81–93. doi: 10.1080/07370016.2024.2416957

Gomes Neto, M., Menezes, M. A., and Oliveira Carvalho, V. (2014). Dance therapy in patients with chronic heart failure: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 28, 1172–1179. doi: 10.1177/0269215514534089

Guetin, S., Ginies, P., Siou, D. K., Picot, M. C., Pommie, C., Guldner, E., et al. (2012). The effects of music intervention in the management of chronic pain: a single-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Clin. J. Pain 28, 329–337. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31822be973

Guzman-Garcia, A., Hughes, J. C., James, I. A., and Rochester, L. (2013). Dancing as a psychosocial intervention in care homes: a systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 28, 914–924. doi: 10.1002/gps.3913

Hickman, B., Pourkazemi, F., Pebdani, R. N., Hiller, C. E., and Fong Yan, A. (2022). Dance for chronic pain conditions: a systematic review. Pain Med. 23, 2022–2041. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnac092

Joung, H. J., Kim, T. H., and Park, M. S. (2024). Effect of adapted dance program on gait in adults with cerebral palsy: a pilot study. Front. Neurol. 15:1443400. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1443400

Kang, A., Rohlfing, R., Janss, A., and Stafford, R. (2025). A call to rethink music interventions implementation to address health disparities. Arts. Health 17, 179–183. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2025.2486064

Karkou, V., Aithal, S., Richards, M., Hiley, E., and Meekums, B. (2023). Dance movement therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8:CD011022. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011022.pub3

Karkou, V., Aithal, S., Zubala, A., and Meekums, B. (2019). Effectiveness of dance movement therapy in the treatment of adults with depression: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Front. Psychol. 10:936. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00936

Karkou, V., Dudley-Swarbrick, I., Starkey, J., Parsons, A., Aithal, S., Omylinska-Thurston, J., et al. (2021). Dancing with health: quality of life and physical improvements from an EU collaborative dance programme with women following breast cancer treatment. Front. Psychol. 12:635578. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635578

Kattenstroth, J. C., Kolankowska, I., Kalisch, T., and Dinse, H. R. (2010). Superior sensory, motor, and cognitive performance in elderly individuals with multi-year dancing activities. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2:31. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00031

Koch, S. C., Riege, R. F. F., Tisborn, K., Biondo, J., Martin, L., and Beelmann, A. (2019). Effects of dance movement therapy and dance on health-related psychological outcomes. a meta-analysis update. Front. Psychol. 10:1806. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01806

Korhan, E. A., Uyar, M., Eyigor, C., Hakverdioglu Yont, G., Celik, S., and Khorshid, L. (2014). The effects of music therapy on pain in patients with neuropathic pain. Pain Manag. Nurs. 15, 306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.10.006

Lee, J. H. (2016). The effects of music on pain: a meta-analysis. J. Music Ther. 53, 430–477. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thw012

Lentzari, L., Misouridou, E., Karkou, V., Paraskeva, M., Tsiou, C., Govina, O., et al. (2023). The experience of dancing among individuals with cerebral palsy at an inclusive dance group: a qualitative study. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1425, 443–456. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-31986-0_43

Lorek, M., Bak, D., Kwiecien-Jagus, K., and Medrzycka-Dabrowska, W. (2023). The effect of music as a non-pharmacological intervention on the physiological, psychological, and social response of patients in an intensive care Unit. Healthcare. 11:1687. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11121687

Massó-Guijarro, B., Ramos Herrera, G. M., and Ocaña Fernández, A. (2025). Dance for all: a qualitative synthesis of inclusive dance literature. Res. Dance Educ. 1–19. doi: 10.1080/14647893.2025.2524134

McGuire, M., Long, J., Esbensen, A. J., and Bailes, A. F. (2019). Adapted dance improves motor abilities and participation in children with down syndrome: a pilot study. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 31, 76–82. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0000000000000559

McRae, C., Leventhal, D., Westheimer, O., Mastin, T., Utley, J., and Russell, D. (2018). Long-term effects of dance for PD® on self-efficacy among persons with Parkinson's disease. Arts. Health 10, 85–96. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2017.1326390

Mendoza-Sanchez, S., Murillo-Garcia, A., Leon-Llamas, J. L., Sanchez-Gomez, J., Gusi, N., and Villafaina, S. (2022). Neurophysiological response of adults with cerebral palsy during inclusive dance with wheelchair. Biology. 11:1546. doi: 10.3390/biology11111546

Michels, K., Dubaz, O., Hornthal, E., and Bega, D. (2018). “Dance Therapy” as a psychotherapeutic movement intervention in Parkinson's disease. Complement Ther. Med. 40, 248–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.07.005

Moratelli, J. A., Veras, G., Lyra, V. B., Silveira, J. D., Colombo, R., and de Azevedo Guimaraes, A. C. (2023). Evidence of the effects of dance interventions on adults mental health: a systematic review. J. Dance Med. Sci. 27, 183–193. doi: 10.1177/1089313X231178095

Morgan, V. (2014). The feasibility of a holistic wellness program for HIV/AIDS patients residing in a voluntary inpatient treatment program. J. Holist. Nurs. 32, 54–60. doi: 10.1177/0898010113489178

ParableDance (2025). Parable Dance Inclusive Training. Parable Dance. Available online at: https://parabledance.co.uk/what-we-offer/inclusive-training/ (Accessed August 12, 2025).

Peng Xu, X., Hu, P., Zhu, X., and Wang, L. (2024). The physical and psychological effects of dance therapy on middle-aged and older adult with arterial hypertension: a systematic review. Heliyon 10:e39930. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e39930

Peng, Y., Su, Y., Wang, Y. D., Yuan, L. R., Wang, R., and Dai, J. S. (2021). Effects of regular dance therapy intervention on blood pressure in hypertension individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 61, 301–309. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.20.11088-0

Roy, M., Lebuis, A., Hugueville, L., Peretz, I., and Rainville, P. (2012). Spinal modulation of nociception by music. Eur. J. Pain. 16, 870–877. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2011.00030.x

Ruiz-Muelle, A., and Lopez-Rodriguez, M. M. (2019). Dance for people with Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 16, 919–933. doi: 10.2174/1567205016666190725151614

Savidaki, M., Demirtoka, S., and Rodriguez-Jimenez, R. M. (2020). Re-inhabiting one's body: a pilot study on the effects of dance movement therapy on body image and alexithymia in eating disorders. J. Eat. Disord. 8:22. doi: 10.1186/s40337-020-00296-2

Schrader, C. A. (2005). A Sense of Dance: Exploring Your Movement Potential. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Schroeder, K., Ratcliffe, S. J., Perez, A., Earley, D., Bowman, C., and Lipman, T. H. (2017). Dance for health: an intergenerational program to increase access to physical activity. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 37, 29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2017.07.004

Seedbed (2025). Seedbed Professional Training. Stopgap Dance Company. Available online at: https://www.stopgapdance.com/learn-and-practice/professional-training/practitioner-training/seedbed/ (Accessed August 12, 2025).

SENDance (2025). SEN Dance. Empower: Inclusive Dance for Teachers and Carers. Amici Dance Theatre Company. Available online at: https://www.hfals.ac.uk/courses/special-educational-needs/sen-dance/empower-inclusive-dance-for-teachers-and-carers (Accessed August 12, 2025).

SENDTraining (2025). Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) Training: Inclusive Dance for Adults. Synergy Dance. Available online at: https://futurefitforbusiness.co.uk/course/send-training-inclusive-dance-for-adults/ (Accessed August 12, 2025).

Tomaszewski, C., Belot, R. A., Essadek, A., Onumba-Bessonnet, H., and Clesse, C. (2023). Impact of dance therapy on adults with psychological trauma: a systematic review. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 14:2225152. doi: 10.1080/20008066.2023.2225152

Wang, J., Yin, Y., Yu, Z., Lin, Q., and Liu, Y. (2024). Does dance therapy benefit the improvement of blood pressure and blood lipid in patients with hypertension? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11:1421124. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1421124

Waugh, M., Youdan, G. Jr., Casale, C., Balaban, R., Cross, E. S., and Merom, D. (2024). The use of dance to improve the health and wellbeing of older adults: a global scoping review of research trials. PLoS ONE 19:e0311889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0311889

Woolf, S., and Fisher, P. (2015). The role of dance movement psychotherapy for expression and integration of the self in palliative care. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 21, 340–348. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2015.21.7.340

WSU (2025). Therapeutic Dance Certificate of Proficiency. Weber State University. Lindquist College of Arts & Humanities. Available online at: https://catalog.weber.edu/preview_program.php?catoid=23&poid=11973&_gl=1*vimu8u*_gcl_au*NTUwNTI1MjUuMTc1NDk1Nzk3MQ (Accessed August 12, 2025).

Keywords: dance-movement psychotherapy, dance therapy, dance-movement therapy, adapted dance, inclusive dance, dance for health, therapeutic dance, dance as therapy

Citation: Elpidoforou M, Polyzogopoulou E, Parissis JT and Farmakis D (2025) Dance-based interventions in clinical populations: not all are the same. Front. Psychol. 16:1668357. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1668357

Received: 17 July 2025; Accepted: 22 September 2025;

Published: 17 October 2025.

Edited by:

Steven Robert Livingstone, Ontario Tech University, CanadaReviewed by:

Rebecca Elizabeth Barnstaple, University of Guelph, CanadaPatricia Anne Mckinley, McGill University, Canada

Natalia Ollora Triana, International University of La Rioja, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Elpidoforou, Polyzogopoulou, Parissis and Farmakis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michail Elpidoforou, bWVscGlkb2Zvcm91QHVuaXdhLmdy; ZWxwaWRvZm9yb3VtaWNoYWxpc0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Michail Elpidoforou

Michail Elpidoforou Effie Polyzogopoulou2

Effie Polyzogopoulou2 John T. Parissis

John T. Parissis Dimitrios Farmakis

Dimitrios Farmakis