Abstract

Objective:

The underlying mechanism between subjective socioeconomic status (SSS) and depressive symptoms among women of reproductive age in China is not fully. This study aims to explore the mediating roles of marital satisfaction and well-being in the association between SSS and depressive symptoms.

Methods:

A total of 4,219 women of reproductive age were selected from the 2022 China Family Panel Studies. Data related to SSS, marital satisfaction, well-being, and depressive symptoms were extracted. Spearman rank regression and bootstrap methods were used to analyze the chain mediation effects of SSS, marital satisfaction, well-being, and depressive symptoms.

Results:

(1) SSS, marital satisfaction, well-being, and depressive symptoms were significantly correlated (p < 0.01). (2) SSS directly affected depressive symptoms (β = −0.1092, p < 0.001). (3) Marital satisfaction (β = −0.0873, p < 0.001) and well-being (β = −0.0867, p < 0.001) each played a mediating role in the effect of SSS on depressive symptoms. (4) Marital satisfaction and well-being played a chain mediating role in the association between SSS and depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age (β = −0.0703, p < 0.001).

Conclusion:

There is a chain mediation effect between SSS, marital satisfaction, well-being, and depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age. Improvement in SSS can enhance marital satisfaction, which in turn increases well-being, ultimately alleviating depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age.

Introduction

Women of reproductive age typically refer to females between the ages of 15 and 49 who are in their childbearing years (Qian et al., 2024). According to the seventh national population census, the number of women of reproductive age in China is 320 million, accounting for 22.9% of the total population (National Bureau of Statistics, 2020). Women of reproductive age are not only important participants in the socio-economic development and core links in families, but they are also a vulnerable group when it comes to mental health issues. This is especially true for married women, who often face challenges from multiple aspects, such as work pressure, family responsibilities, and personal life (Kim et al., 2022; Maeda et al., 2019; Vincent et al., 2025). Their mental health not only affects their own quality of life but also has the potential to influence the next generation through intergenerational transmission. Therefore, focusing on the mental health of women of reproductive age has significant social implications.

Depression is a common mental disorder that can lead to low mood, impaired cognitive function, and even increase the risk of suicide (Han et al., 2024). Preventive and health-promoting actions at the individual level play a crucial role in reducing the prevalence of depression (Herrman et al., 2022). The World Health Organization (WHO) has highlighted that women are more susceptible to depression and anxiety compared to men, with depression being a leading contributor to the disease burden among women in both high-income and low- to middle-income countries (World Health Organization, 2018). A study by Dai et al. (2025) found that from 1990 to 2021, the global burden of depression among women of reproductive age showed a significant upward trend. A survey from rural Hubei province in China revealed that socioeconomic status, illness, and stress are negative factors influencing depressive symptoms among women of reproductive age (Cao et al., 2015). For women of reproductive age, depressive symptoms may also affect the physical and mental health of offspring, creating a negative intergenerational cycle (Motrico et al., 2023; Silverman et al., 2020).

Subjective socioeconomic status (SSS) refers to an individual’s subjective perception of their own social class and economic standing, and is considered to be more sensitive in reflecting an individual’s mental health status compared to socioeconomic status (SES) (Choi et al., 2015). A study from Iran showed that the mediating role of SSS between SES and General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28) scores accounted for over 80% (Nasirpour et al., 2024). Another study on East Asian countries (China, Japan, and Korea) indicated that SSS consistently predicted depression across these three countries (Zang and Bardo, 2019). In the Chinese context, Shu et al. (2024) investigated the relationship between subjective family status and depression in Chinese adolescents, finding a significant correlation between these two variables. Kwong et al. (2020) conducted a 4-year follow-up study on elderly individuals in Hong Kong and concluded that SSS is an independent predictor of long-term mood, highlighting that SSS can capture important aspects of social status that SES may not fully reflect. Tan et al. (2023) studied healthcare workers after emergency risk events and found that a higher SSS could reduce depression in healthcare workers. Collectively, studies from China and other countries suggest that low SSS increases the risk of depressive symptoms. When individuals perceive themselves to be in a lower social economic position, the relative deprivation they feel can give rise to emotions such as jealousy and depression (Li et al., 2025).

Marital satisfaction is the subjective evaluation of the quality of the marital relationship, encompassing various dimensions such as emotional support, conflict resolution, and role division (Nadolu et al., 2020). Marital satisfaction is considered a significant predictor of depressive symptoms, with marital discord being a risk factor for depression (Du et al., 2021; Yang L. et al., 2023). A harmonious marriage can buffer stress by providing positive support, thereby reducing the occurrence of depressive symptoms. Social capital and economic foundation are among the essential factors for maintaining marriage. Previous studies have pointed out that low SSS can lower marital satisfaction (Jia et al., 2025). Women of reproductive age, who bear more family responsibilities, are particularly vulnerable to fluctuations in socioeconomic status (Rashidi Fakari et al., 2022), such as career interruptions or income decline. These changes can reduce their influence in family decision making, leading to marital dissatisfaction and psychological distress.

Well-being is the subjective evaluation of an individual’s quality of life (Xiao and Huang, 2022), including assessments of both their objective environment and subjective emotional state. Research has indicated that high SSS can enhance well-being (Chen et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023), and well-being itself is a related variable for predicting depressive symptoms (Tran et al., 2017; Grant et al., 2013). Marital satisfaction is also linked to well-being (Yang Y. et al., 2023), and a harmonious marital relationship can enhance emotional support, thereby improving well-being.

In the model of this study, social rank theory and relative deprivation theory serve as the theoretical foundation. Individuals form subjective perceptions of their socioeconomic status through comparisons with others. Downward comparisons bring relative satisfaction, while upward comparisons generate relative deprivation. The relative psychological feelings generated in this subjective environment are more likely to influence people’s attitudes and behaviors than the objective environment (Kraus and Keltner, 2013; Kraus et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2012). Based on these theories, this study introduces family stress theory. Reuben Hill defined family stress as the pressure resulting from a lack of resources when the family is in difficulty. The psychological pressure brought about by relative deprivation can erode the harmonious family structure, promoting the onset of depressive symptoms through marital dissatisfaction on both spouses’ part (Hill, 1951). Furthermore, marital satisfaction is part of an individual’s subjective experience. The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) theory theoretically explains the association between marital satisfaction and well-being. In marriage, both spouses are not isolated individuals but interdependent subjects. A lack of well-being increases the risk of depression (Cook and Kenny, 2005).

The current research gap lies in the fact that existing studies have partially explored SSS, marital satisfaction, well-being, and depressive symptoms but have not integrated these four variables into one model for analysis, particularly focusing on the vulnerable group of women of reproductive age. Therefore, this study incorporates social rank theory, relative deprivation theory, family stress theory, and the APIM theory into a single model using chain mediation. It posits that depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age are not only influenced by social comparison but also related to family stress and positive psychological resources. By exploring the relationships among these four variables, this study provides insights at the social and family levels for future interventions in depressive symptoms among women of reproductive age.

In summary, although there have been studies on the association between SSS and depressive symptoms in various groups (Wu et al., 2023; Anna and Michael, 2023; Assari et al., 2018), research on how SSS affects depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age is relatively limited, especially studies related to chain mediation. Therefore, this study aims to explore the association between SSS and depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age, with a focus on the roles of marital satisfaction and well-being in this association.

The following hypotheses are proposed in this study:

Hypothesis 1: SSS negatively predicts depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age.

Hypothesis 2: Marital satisfaction mediates the association between SSS and depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age.

Hypothesis 3: Well-being mediates the association between SSS and depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age.

Hypothesis 4: Marital satisfaction and well-being jointly mediate the association between SSS and depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age through a chain mediation effect.

Materials and methods

Sample and data collection

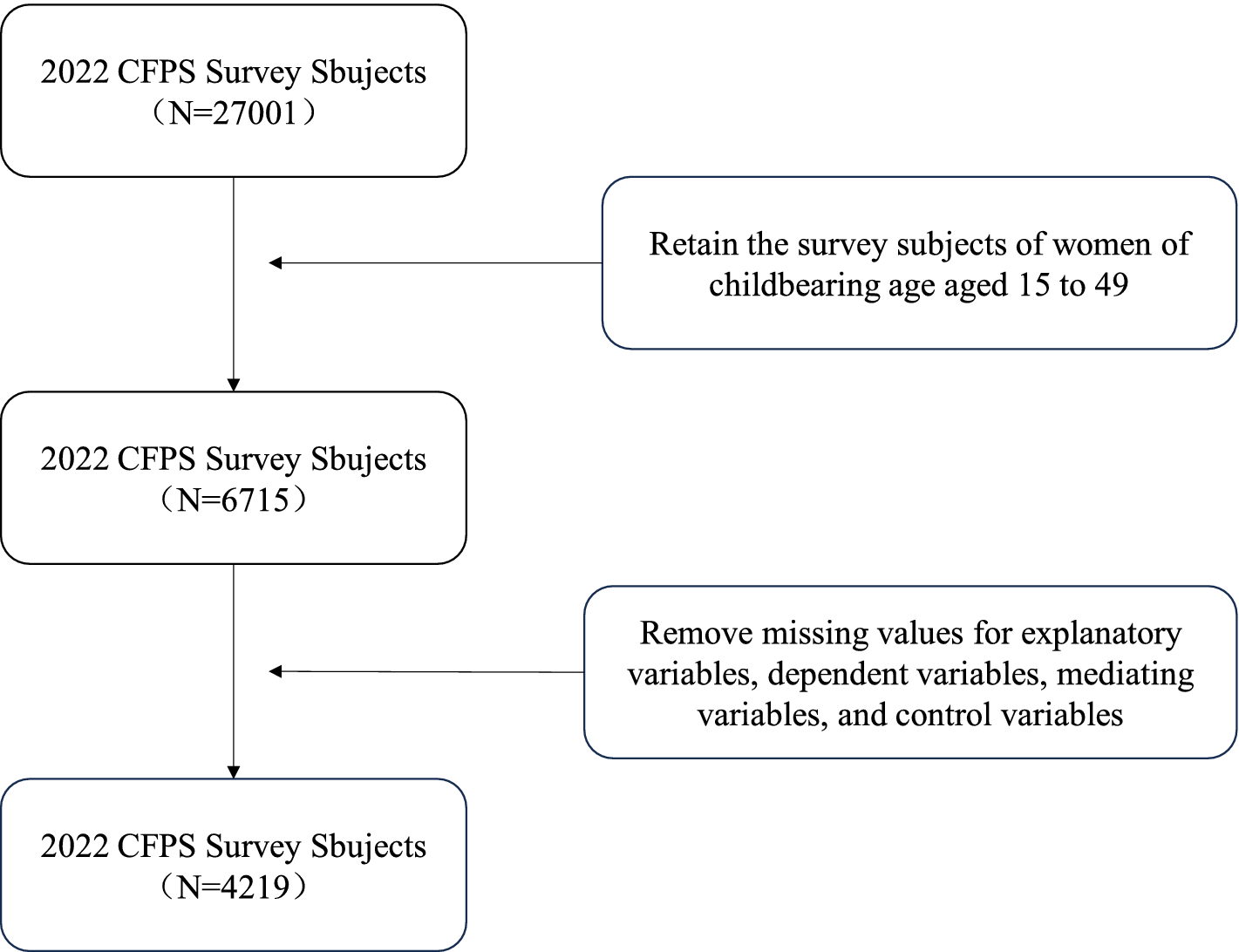

The data used in this study comes from the 2022 individual questionnaire of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), conducted by the Social Science Survey Center at Peking University. The CFPS uses a multi-stage stratified sampling approach to gather data at the individual, family, and community levels. It focuses on both the economic and non-economic welfare of Chinese residents, covering a wide range of research topics such as economic activities, educational outcomes, family dynamics, population migration, and health (Xie and Hu, 2015). Since this study involves marital satisfaction among women of reproductive age, and the legal marriage age for women in China is 20 years old, the study sample was limited to married women of reproductive age between 20 and 49 years. After excluding samples with missing key variables, a total of 4,219 complete individual samples were selected. The specific screening process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Variable screening process.

Measure

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptom severity was evaluated using the 8-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-8) (Van de Velde et al., 2009). The applicability of the CESD-8 has been confirmed in previous studies (Zhao et al., 2024). The CESD-8 consists of eight items, and participants are required to respond to the following eight questions: “I feel depressed,” “I feel strained doing anything,” “My sleep is not good,” “I feel happy,” “I feel lonely,” “I live a happy life,” “I feel sad,” and “I feel that life cannot continue.” Respondents answer these eight questions using four options: 1 = “Rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day),” 2 = “Some of the time (1–2 days),” 3 = “Most of the time (3–4 days),” and 4 = “All of the time (5–7 days).” These four options are scored from 1 to 4 points. The questions “I feel happy” and “I live a happy life” are positive emotion items, and these two items were reverse-scored (i.e., 1 = “Most of the time (5–7 days)” to 4 = “Almost none of the time (less than 1 day)”). The total score of the scale ranges from 8 to 32 points, with a higher score indicating more severe depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age. In this study, Cronbach’s α = 0.776.

SSS

Based on previous studies (Zhou et al., 2023; Yuan and Yueping, 2022), this study uses two questions from the CFPS questionnaire to assess the SSS of women of reproductive age: “How would you rate your social status in your locality?” and “How would you rate your income status in your locality?” Both questions use a 5-point scale (1 point representing very low to 5 points representing very high). The sum of the scores from these two questions is used as the composite score for SSS. The score range is from 2 to 10, with a higher score indicating a higher SSS. In this study, the mean score for the question “How would you rate your social status in your locality?” was 2.81 (standard deviation = 0.991), with a skewness of 0.082. The mean score for the question “How would you rate your income position in your locality?” was 2.83 (standard deviation = 1.000), with a skewness of 0.041. Cronbach’s α = 0.713.

Marital satisfaction

Based on previous research (Yang L. et al., 2023), this study measures marital satisfaction using three questions: “In general, how satisfied are you with your current marital life?,” “How satisfied are you with your spouse’s financial contribution to the family?,” and “How satisfied are you with your spouse’s contribution to the family in terms of household chores?.” The score range is 3 to 15 points, with a 5-point scale used for each question (1 representing very dissatisfied to 5 representing very satisfied). Higher scores indicate higher marital satisfaction. In this study, Cronbach’s α = 0.759.

Well-being

Based on previous studies (Sun et al., 2025), this study measures well-being using the question “How happy are you?” from the CFPS questionnaire, with scores ranging from 0 to 10, where higher scores indicate greater happiness among women of reproductive age.

Control variables

Based on previous research (Zhou et al., 2023; Sweeting and Hunt, 2015; Qiu et al., 2023; Chang et al., 2016), this study includes the following control variables: age, household registration (0 = “Rural,” 1 = “Urban”), education level (1 = “Illiterate/semiliterate,” 2 = “Primary school,” 3 = “Junior high school,” 4 = “Senior high school,” 5 = “College or above”), chronic illness (0 = “No,” 1 = “Yes”), physical exercise (0 = “No,” 1 = “Yes”), alcohol consumption (0 = “No,” 1 = “Yes”), smoking (0 = “No,” 1 = “Yes”), geographical distribution (1 = “Western China,” 2 = “Central China,” 3 = “Eastern China,” 4 = “Northeastern China”), caregiver during illness (1 = “Parents,” 2 = “Spouse,” 3 = “Children,” 4 = “Other family members,” 5 = “Non-family members,” 6 = “Did not get sick,” 7 = “No one/No care needed.”), and health change in the past year (1 = “Better,” 2 = “No change,” 3 = “Worse”).

Statistical analysis

This study uses SPSS 27.0 and R 4.5.1 software for statistical analysis. The Harman single-factor test is used to check for common method bias. Categorical data are described using frequency (N) and percentage (%). The results of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicated that SSS, marital satisfaction, well-being, and depressive symptoms do not follow a normal distribution (all p < 0.001). Therefore, non-normally distributed continuous data are described using the median (P25, P75). The Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis test are used for difference analysis. Spearman rank correlation analysis is used for correlation analysis. The chain mediation effect is tested using the PROCESS v4.0 macro program developed by Hayes (2017). After incorporating control variables, SSS was set as the independent variable (X), depressive symptoms as the dependent variable (Y), and marital satisfaction (M1) and well-being (M2) as mediating variables. The chain mediation effect is tested using the Bootstrap method with 5,000 iterations, which does not involve the population distribution or its parameters, making it suitable for non-normally distributed variables in this study. A chain mediation effect is considered statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval (CI) does not include 0. This study uses two methods for sensitivity analysis: causal mediation analysis proposed by Imai et al. (2010) and the method of adding control variables (Coleman et al., 2020; McNeilly et al., 2022), to assess the robustness of the chain mediation model. Sensitivity analysis was performed using the “mediation” package in R and SPSS PROCESS v4.0. The significance level is set at α = 0.05.

Results

Common method bias test

The data in this study are all based on self-reports from the participants, which may lead to common method bias. Therefore, the Harman single-factor test was used to conduct an unrotated principal component analysis on all 15 items related to depressive symptoms, SSS, marital satisfaction, and well-being. The results showed that there were four factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the variance explained by the first factor was 32.88% (below the critical threshold of 40%). This indicates that there is no significant common method bias in this study.

Descriptive statistical analysis

A total of 4,219 women of reproductive age were included in this study. The median age was 36 (32, 43) years. The median SSS score was 6 (5, 6), the median CESD-8 score was 14 (11, 17), the median marital satisfaction score was 12 (10, 14), and the median well-being score was 8 (6, 9). Women of reproductive age in rural areas, illiterate/semi-illiterate, those with chronic illness, those who did not participate in physical exercise, those from the western region, those with no caregiver or no care needed, and those whose health has worsened in the past year had higher CESD-8 scores. No significant differences in depressive symptoms were found in relation to alcohol consumption or smoking (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1

| Variable | N (%) | Depressive symptoms M(P25, P75) |

Z/H | p | M(P25, P75) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household registration | −4.824 | <0.001 | |||

| Rural | 1,802 (42.7) | 14 (11, 17) | |||

| Urban | 2,417 (57.3) | 13 (11, 16) | |||

| Education level | 90.940 | <0.001 | |||

| Illiterate/semiliterate | 329 (7.8) | 16 (13, 19) | |||

| Primary school | 590 (14.0) | 14 (12, 17) | |||

| Junior high school | 1,500 (35.6) | 14 (11, 17) | |||

| Senior high school | 643 (15.2) | 14 (11, 16) | |||

| College or above | 1,157 (27.4) | 13 (11, 16) | |||

| Chronic illness | −5.043 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 3,863 (91.6) | 14 (11, 16) | |||

| Yes | 356 (8.4) | 15 (12, 18) | |||

| Physical exercise | −6.890 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 2,689 (63.7) | 14 (11, 17) | |||

| Yes | 1,530 (36.3) | 13 (11, 16) | |||

| Alcohol consumption | −0.265 | 0.791 | |||

| No | 4,129 (97.9) | 14 (11, 17) | |||

| Yes | 90 (2.1) | 14 (10.75, 17) | |||

| Smoking | −0.708 | 0.479 | |||

| No | 4,164 (98.7) | 14 (11, 17) | |||

| Yes | 55 (1.3) | 14 (11, 17) | |||

| Geographical distribution | 60.396 | <0.001 | |||

| Western China | 1,200 (28.4) | 14 (12, 17) | |||

| Central China | 1,124 (26.6) | 14 (11, 16) | |||

| Eastern China | 1,425 (33.8) | 14 (11, 16) | |||

| Northeastern China | 470 (11.1) | 13 (10, 16) | |||

| Caregiver during illness | 116.950 | <0.001 | |||

| Parents | 238 (5.6) | 14 (11, 17) | |||

| Spouse | 1,897 (45.0) | 14 (11, 16) | |||

| Children | 88 (2.1) | 14 (11, 17) | |||

| Other family members | 31 (0.7) | 14 (11, 17) | |||

| Non-family members | 39 (0.9) | 16 (13, 17) | |||

| Did not get sick | 737 (17.5) | 13 (10, 16) | |||

| No one/no care needed | 1,189 (28.2) | 15 (12, 18) | |||

| Health change in the past year | 221.041 | <0.001 | |||

| Better | 408 (9.7) | 13 (10, 16) | |||

| No change | 2,687 (63.7) | 13 (11, 16) | |||

| Worse | 1,124 (26.6) | 15 (13, 18) | |||

| Age | 36 (32, 43) | ||||

| Subjective socioeconomic status | 6 (5, 6) | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | 14 (11, 17) | ||||

| Marital satisfaction | 12 (10, 14) | ||||

| Well-being | 8 (6, 9) |

Descriptive statistical analysis (N = 4,219).

Spearman rank correlation analysis

Among women of reproductive age, SSS was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms (p < 0.01), marital satisfaction was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms (p < 0.01), and well-being was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms (p < 0.01). Additionally, SSS was positively correlated with both marital satisfaction and well-being (p < 0.01), and marital satisfaction was positively correlated with well-being (p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2

| Variable | Subjective socioeconomic status | Marital satisfaction | Well-being | Depressive symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective socioeconomic status | 1 | |||

| Marital satisfaction | 0.260** | 1 | ||

| Well-being | 0.270** | 0.535** | 1 | |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.151** | −0.269** | −0.339** | 1 |

Spearman rank correlation analysis.

∗Significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed). ∗∗Significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Analysis of chain mediation effects

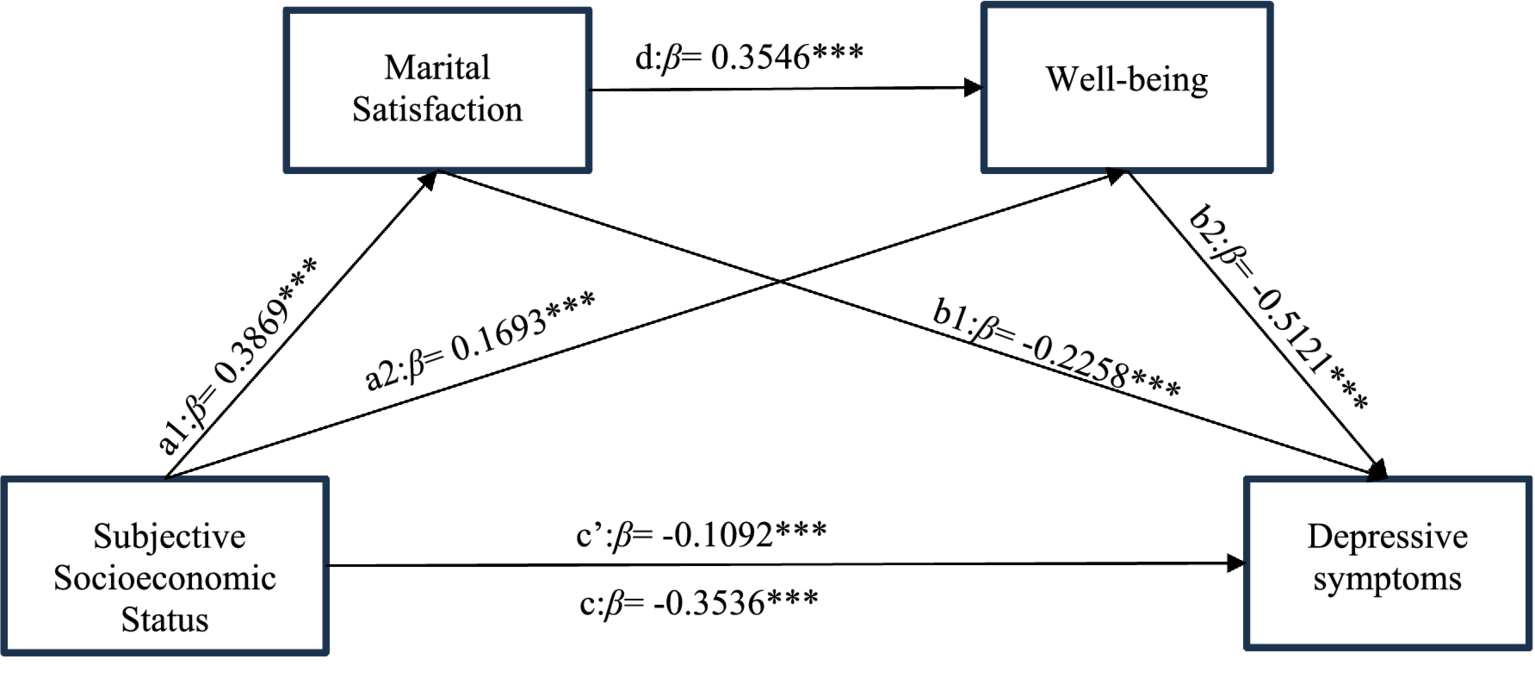

Based on the results of the descriptive and correlation analyses, this study conducted a chain mediation analysis with SSS as the independent variable, depressive symptoms as the dependent variable, and marital satisfaction and well-being as mediating variables, controlling for household registration, education level, chronic illness, physical exercise, and geographical distribution. The results showed that, among women of reproductive age, SSS negatively predicted depressive symptoms (β = −0.1092, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1. After incorporating marital satisfaction and well-being into the model, it was found that SSS positively predicted both marital satisfaction (β = 0.3869, p < 0.001) and well-being (β = 0.1693, p < 0.001). Higher marital satisfaction was significantly correlated with higher well-being (β = 0.3546, p < 0.001) and fewer depressive symptoms (β = −0.2258, p < 0.001), and well-being negatively predicted depressive symptoms (β = −0.5121, p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3

| Variable | Model 1:marital satisfaction (M1) | Model 2:well-being (M2) | Model 3:depressive symptoms (Y) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Se | t | 95% CI | β | Se | t | 95% CI | β | Se | t | 95% CI | |

| Subjective socioeconomic status (X) | 0.3869*** | 0.0233 | 16.5940 | (0.3412,0.4326) | 0.1693*** | 0.0145 | 11.6742 | (0.1409,0.1977) | −0.1092*** | 0.0326 | −3.3468 | (−0.1732, −0.0452) |

| Marital satisfaction (M1) | 0.3546*** | 0.0093 | 38.1889 | (0.3364,0.3729) | −0.2258*** | 0.0239 | −9.4588 | (−0.2726, −0.1790) | ||||

| Well-being (M2) | −0.5121*** | 0.0341 | −15.0019 | (−0.5791, −0.4452) | ||||||||

| Age | −0.0104 | 0.0063 | −1.6404 | (−0.0228,0.0020) | −0.0129*** | 0.0038 | −3.3760 | (−0.0204, −0.0054) | −0.0384*** | 0.0085 | −4.5364 | (−0.0550, −0.0218) |

| Household registration | −0.2038 | 0.0888 | −2.2963 | (−0.3778, −0.0298) | 0.1112 | 0.0535 | 2.0787 | (0.0063,0.2162) | −0.0731 | 0.1186 | −0.6166 | (−0.3057,0.1594) |

| Education level | −0.1059** | 0.0393 | −2.6954 | (−0.1829, −0.0289) | 0.0772** | 0.0237 | 3.2568 | (0.0307,0.1236) | −0.4418*** | 0.0525 | −8.4075 | (−0.5448, −0.3388) |

| Chronic illness | −0.1845 | 0.1462 | −1.2621 | (−0.4710,0.1021) | −0.2265* | 0.0881 | −2.5715 | (−0.3992, −0.0538) | 0.8553*** | 0.1953 | 4.3797 | (0.4724,1.2381) |

| Physical exercise | 0.0537 | 0.0881 | 0.6100 | (−0.1190,0.2264) | 0.2030*** | 0.0531 | 3.8236 | (0.0989,0.3070) | −0.4655 | 0.1178 | −3.9523 | (−0.6964, −0.2346) |

| Geographical distribution | 0.1661*** | 0.0419 | 3.9650 | (0.0840,0.2482) | 0.1160*** | 0.0253 | 4.5856 | (0.0664,0.1656) | −0.2498*** | 0.0562 | −4.4482 | (−0.3599, −0.1397) |

| Constant | 10.0987*** | 0.3261 | 30.9676 | (9.4594,10.7380) | 2.0833*** | 0.2178 | 9.5672 | (1.6564,2.5102) | 24.7387*** | 0.4875 | 50.7419 | (23.7829,25.6946) |

| R | 0.2648*** | 0.5700*** | 0.4352*** | |||||||||

| R2 | 0.0701 | 0.3249 | 0.1894 | |||||||||

| F | 45.3508 | 253.2647 | 109.2414 | |||||||||

Regression analysis of subjective socioeconomic status, marital satisfaction, and well-being on depressive symptoms.

∗Significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed). ∗∗Significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed). ∗∗∗Significant at the 0.001 level (two-tailed).

Using SPSS PROCESS macro Model 6 with control variables, the mediation effect of marital satisfaction and well-being in the association between SSS and depressive symptoms was tested. The results are shown in Table 4. The total effect was significant (95% CI: −0.4189, −0.2882), the direct effect was significant (95% CI: −0.1732, −0.0452), and the total indirect effect was significant (95% CI: −0.2825, −0.2083). Marital satisfaction had a significant mediating effect in the association between SSS and depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age (95% CI: −0.1116, −0.0653), supporting Hypothesis 2. Well-being also had a significant mediating effect in the association between SSS and depressive symptoms (95% CI: −0.1101, −0.0656), supporting Hypothesis 3. Additionally, marital satisfaction and well-being had a significant chain mediation effect in the association between SSS and depressive symptoms (95% CI: −0.0867, −0.0556), supporting Hypothesis 4. The chain mediation model of marital satisfaction and well-being in the association between SSS and depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age is shown in Figure 2.

Table 4

| Path | Effect | Boot SE | Boot 95%CI | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | −0.3536 | 0.0333 | (−0.4189, −0.2882) | |

| Direct effect | −0.1092 | 0.0326 | (−0.1732, −0.0452) | 30.88% |

| Total mediation effect | −0.2443 | 0.0188 | (−0.2825, −0.2083) | 69.09% |

| Subjective socioeconomic status—Marital satisfaction—Depressive symptoms | −0.0873 | 0.0118 | (−0.1116, −0.0653) | 24.69% |

| Subjective socioeconomic status—Well-being—Depressive symptoms | −0.0867 | 0.0112 | (−0.1101, −0.0656) | 24.52% |

| Subjective socioeconomic status—Marital satisfaction—Well-being—Depressive symptoms | −0.0703 | 0.0079 | (−0.0867, −0.0556) | 19.88% |

Significance test of mediation effects.

Figure 2

The chain mediation effect model of marital satisfaction and well-being in the association between subjective socioeconomic status and depressive symptoms. ∗Significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed). ∗∗Significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed). ∗∗∗Significant at the 0.001 level (two-tailed).

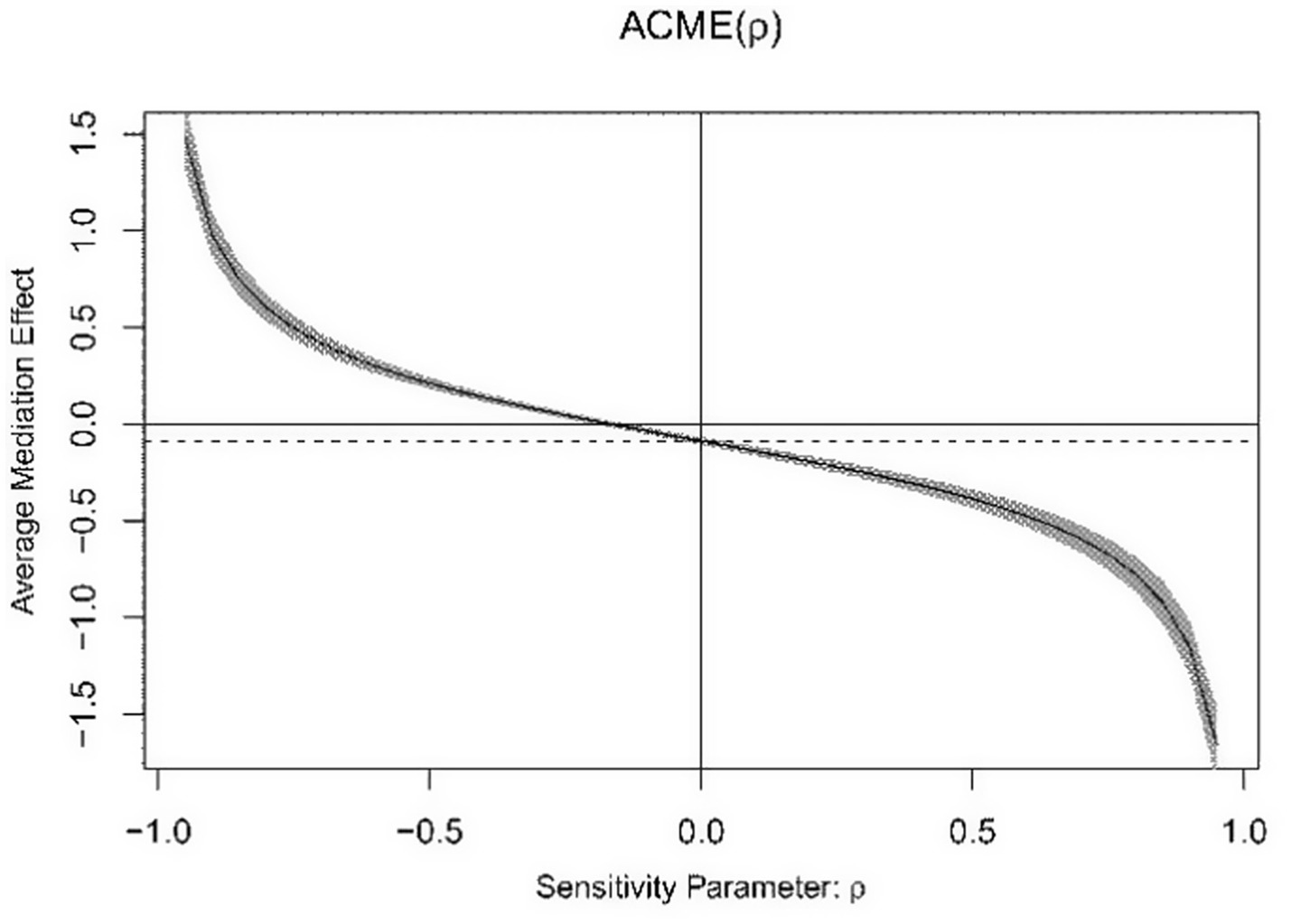

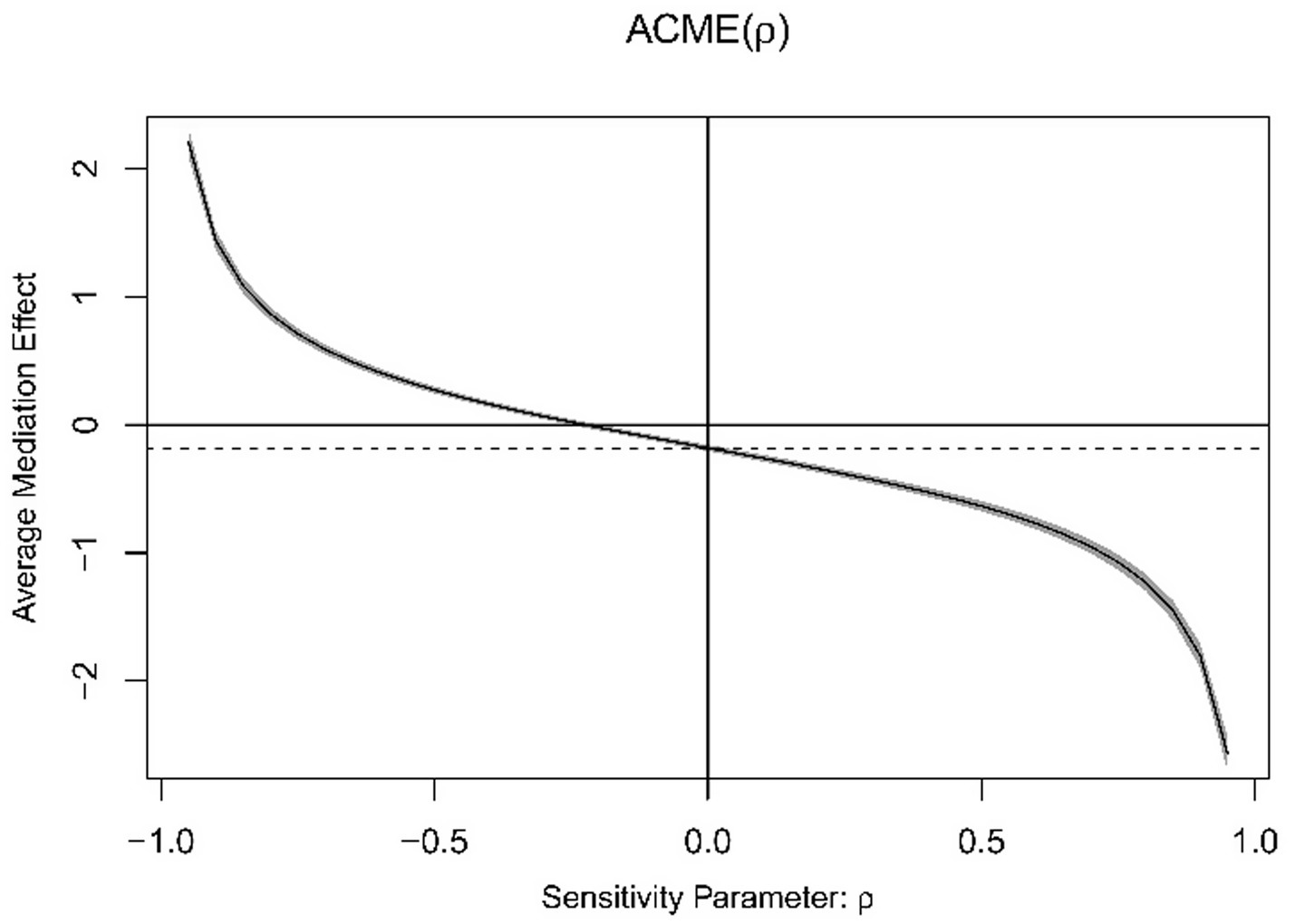

Sensitivity analysis

The average causal mediation analysis was conducted separately for Model 1 and Model 2. The results showed that when the average causal mediation effect (ACME) of the model was 0, the rho value for Model 1 must be at least −0.15, and the rho value for Model 2 must be at least −0.25 (Figures 3, 4). By adding the caregiver during illness and health change in the past year as additional control variables into Model 3, the results indicated that the chain mediation effect still held (Table 5). The sensitivity analysis suggests that the mediation effect in this study is robust.

Figure 3

Average causal mediation analysis of Model 1.

Figure 4

Average causal mediation analysis of Model 2.

Table 5

| Path | Effect | Boot SE | Boot 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | −0.2954 | 0.0330 | (−0.3601, −0.2307) |

| Direct effect | −0.0820 | 0.0323 | (−0.1454, −0.0186) |

| Total mediation effect | −0.2134 | 0.0177 | (−0.2496, −0.1792) |

| Subjective socioeconomic status—Marital satisfaction—Depressive symptoms | −0.0714 | 0.0106 | (−0.0930, −0.0518) |

| Subjective socioeconomic status—Well-being—Depressive symptoms | −0.0818 | 0.0107 | (−0.1040, −0.0617) |

| Subjective socioeconomic status—Marital satisfaction—Well-being—Depressive symptoms | −0.0602 | 0.0070 | (−0.0749, −0.0472) |

The mediation effect values in the sensitivity analysis.

Discussion

This study used data from the 2022 CFPS to conduct a cross-sectional analysis on women of reproductive age, examining SSS, marital satisfaction, well-being, and depressive symptoms. The results revealed that marital satisfaction and well-being served as a sequential mediator in the association between SSS and depressive symptoms in this group. The total mediation effect accounted for 69.09%, explaining most of the total effect. This reflects the significant role of the family system and individual positive emotions in alleviating depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age, providing a theoretical reference for multi-level approaches to ensuring the mental health of women of reproductive age.

SSS influences depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age

The results of this study found that SSS was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms (β = −0.1092). The direct effect explained 30.88% of the variation of total effect, indicating that the higher the SSS, the lower the risk of depressive symptoms among women of reproductive age, which is consistent with previous studies (Hoebel et al., 2017; Assari et al., 2018; Callan et al., 2015). Both the Social Rank Theory of Depression (Wetherall et al., 2018) and the Relative Deprivation Theory (Mummendey et al., 1999) support the idea that depression can arise through social comparison. According to the Social Rank Theory of Depression, when an individual perceives themselves to be in a lower rank or disadvantaged position within a group, the frustration caused by this status gap significantly lowers their psychological evaluation of their own socioeconomic status, leading to depression and other mental health issues (Carraturo et al., 2023; Xiong and Hu, 2022). The Relative Deprivation Theory also suggests that when individuals compare themselves to social reference groups and perceive a gap, they experience negative feelings of deprivation regarding their resources or rights, leading to self-deprecation, inferiority, and other negative psychological states (Cundiff and Matthews, 2017; Yang et al., 2021).

Combining the aforementioned theories with the specific circumstances of women of reproductive age, it can be observed that women in this group not only engage in horizontal comparisons with colleagues and friends around them but also experience vertical self-comparisons. Career interruptions caused by childbearing force women to choose between career development and family caregiving (Zhang L. et al., 2024). The results of the Fourth China Women’s Social Status Survey show that only 2.7% of children under the age of 3 are primarily cared for by childcare institutions during the day, while 63.7% are cared for by their mothers (The Fourth Chinese Women’s Social Status Survey Office, 2022), reflecting the heavy caregiving burden on women of reproductive age, making it difficult to balance career development. This disparity caused by self-comparison, where income and status decline, may lead to a sense of relative deprivation, weaken their perception of their own socioeconomic status, and result in depression.

Marital satisfaction mediates the association between SSS and depressive symptoms

Marital satisfaction mediates the association between SSS and depressive symptoms, accounting for 24.69% of the mediation effect. The higher the SSS of women of reproductive age (β = 0.3869), the higher their satisfaction with their marital association (β = −0.2258). These findings are consistent with previous research results (Leng et al., 2021; Moore et al., 2017). Higher marital satisfaction, in turn, reduces the risk of depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age. From the perspective of Family Stress Theory, changes in status perception due to family economic difficulties and lack of social resources can increase tension in marital relationships, leading to escalating family conflicts (Papp et al., 2009). Couples with low SSS are more likely to experience dissatisfaction with each other and less mutual understanding, thereby reducing marital quality.

However, marriage is a key source of emotional support, and a decrease in marital satisfaction removes a critical pathway for buffering stress. In the Marital Discord Model of Depression (MDMD), marital discord is considered a significant risk factor for depressive symptoms (Beach et al., 1990). Research by Whisman (2001) suggests that women are more likely to experience depressive symptoms than men as a result of reduced marital satisfaction. Similarly, Yang L. et al. (2023) using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Moderation Model (APIMoM), found a strong negative correlation between individuals’ marital satisfaction and both their own and their spouse’s depressive symptoms, with wives being more susceptible to depressive symptoms than husbands. Thus, making significant contributions to family finances and maintaining a harmonious marital relationship are important ways to effectively reduce depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age. Maintaining a good marital relationship serves as a protective factor for women of reproductive age in combating depressive symptoms.

Well-being mediates the association between SSS and depressive symptoms

Well-being mediates the association between SSS and depressive symptoms, accounting for 24.52% of the mediation effect. Women of reproductive age with higher SSS have higher well-being (β = 0.1693), and higher well-being is associated with a lower risk of depressive symptoms (β = −0.5121). These findings are consistent with previous research (Grant et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2017). Positive psychology advocates for discovering one’s positive factors, and positive emotions are considered the best “weapon” to combat psychological disorders (Seligman, 2008). A meta-analysis by Tan et al. (2020) indicated that SSS is more strongly correlated with well-being than objective socioeconomic status. Curhan et al. (2014) analyzed the association between SSS and SES and mental health in the United States and Japan, finding that both could predict well-being. For women of reproductive age, those with higher SSS may have better access to material resources such as healthcare and education. Furthermore, high SSS, as a product of higher social rank, enhances self-worth and a sense of social respect, thereby increasing well-being. In contrast, low SSS may increase stress due to perceptions of insufficient economic and social support, which could diminish well-being.

In this study, a decrease in well-being was found to increase the risk of depressive symptoms. A study of Mexican women also highlighted the association between well-being and depressive symptoms, noting that lower well-being scores could evolve into a risk factor for severe depression (Hernández-Muñoz et al., 2022). Women of reproductive age are in a unique phase of life, where estrogen influences cognitive, behavioral, and emotional processes by regulating neurotransmitter systems (Colzato and Hommel, 2014), making them more susceptible to emotional fluctuations. Additionally, during this period, women face various social issues and conflicts, including parenting pressure, elder care, and housing loans, among others. The accumulation of negative emotions over time negatively affects well-being, ultimately leading to the emergence of depressive symptoms.

Marital satisfaction and well-being serve as a chain mediating effect between SSS and depressive symptoms

Enhancing SSS can boost marital satisfaction, which in turn improves well-being and helps alleviate depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age, with the mediation effect accounting for 19.88%. This study also identified a decline in marital satisfaction as a predictor of lower well-being (β = 0.3546), aligning with the findings of Cook and Kenny (2005) based on the Actor-Partner Independence Model. In marital relationships, when one partner experiences dissatisfaction, they may attribute the blame to their spouse, thereby causing negative psychological effects on the other person. Conversely, individuals in happy marriages are more likely to provide emotional support and positive reinforcement to their partners, and such positive interactions help to increase the well-being of both spouses (Thomas et al., 2017). The positive emotional support derived from enhanced well-being can assist women of reproductive age in better coping with the pressures and challenges of life, reducing the occurrence of depressive symptoms.

This pathway indicates that the association between SSS and depressive symptoms is not a single, direct process, but also involves the interaction between family dynamics and individual subjective psychological experiences. Women with higher SSS may improve marital quality through economic resources and social support, which in turn enhances their well-being. Higher well-being, in turn, may help them face marital challenges with a more positive attitude, creating a virtuous cycle. In conclusion, marital satisfaction and well-being play independent mediating roles between SSS and depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age, and they also exhibit a chain mediation effect.

Implications

To improve the mental health of women of reproductive age, this study proposes several recommendations based on the research findings. Firstly, there is a need to promote structural support policies aimed at enhancing women’s perception of their SSS. Efforts should focus on building a birth-friendly society that alleviates the economic and caregiving burdens faced by women of reproductive age. This can be achieved through the implementation of national policies such as paid parental leave (Mensah and Adjei, 2020), childcare subsidy (Yang, 2025), and personal income tax deductions (Yang and Zhang, 2023), as well as exploring universal childcare services (Horwood et al., 2021). These measures will help women balance work and family responsibilities, reduce the motherhood penalty (Yu and Liang, 2022), enhance income security, and improve career continuity, ultimately strengthening their SSS perception.

Secondly, it is crucial to strengthen family support and incorporate marital relationships into grassroots public services. Marital and family development should be integrated with community governance, and community grid-based services can be leveraged to provide public services like marriage communication skills training (Nejatian et al., 2021) and family conflict mediation. These initiatives will help women of reproductive age and their spouses build healthy interaction patterns, improve marital satisfaction (Alipour et al., 2020), and strengthen the emotional support provided by marriage.

Thirdly, targeted psychological interventions should be implemented with a focus on vulnerable groups. More focus should be directed towards the mental health of women of reproductive age at high risk of depression, especially in rural and western areas of China (Wang et al., 2024). These regions have lower levels of socioeconomic development and are more susceptible to negative events such as life pressures and traditional cultural biases, leading to pessimistic emotions. For these groups, a variety of mental health support strategies should be implemented, including regular monitoring of their well-being, the dissemination of mental health information, and the use of digital technology to offer remote psychological counseling (Zhen et al., 2024). This would overcome geographic limitations, improve mental health levels, benefit women in remote areas, and enhance their well-being.

Due to the limitations of the questionnaire, several potential variables that could be relevant to the model were not included. Different personality traits are often related to social and environmental factors, such as one’s social status and marital status (Zhang N. et al., 2024). Personality traits are also important factors influencing depressive symptoms. Previous research has pointed out that, according to the vulnerability-stress model, individuals possessing vulnerability or susceptibility traits are more susceptible to psychological issues like anxiety, depression, and loneliness when confronted with stressful events (He et al., 2025). A history of mental health issues or a family history of psychiatric disorders can influence current depressive symptoms through a vicious cycle, which may affect an individual’s perception of their socioeconomic status (Brandon et al., 2012; Bavle et al., 2016). Additionally, based on the stress process theory, stress can directly or indirectly lead to depressive symptoms. Exposure to chronic stress conditions may continuously cause negative emotions, which in turn can result in an increase in the level of depressive symptoms (Wickrama et al., 2017).

Limitations

It is also important to recognize the limitations of this study. Firstly, the cross-sectional design means that the results primarily reveal the associations between variables and the potential mediating effects, but cannot establish strict causal relationships. Future research could further confirm these findings through longitudinal analysis. Secondly, well-being was measured using a single item, which, although common in large social surveys, does not capture the multidimensional nature of the construct of well-being. Additionally, the measurements of SSS and marital satisfaction were relatively brief. While they demonstrated acceptable internal consistency in this study, compared to more established and comprehensive scales, their content and construct validity may be limited. Thirdly, all variables in this study were obtained through self-reported data from the respondents, which may introduce recall bias and reporting bias. Fourthly, although multiple variables were controlled in this study, potential confounding factors such as personality traits, mental health history, and stress were not included, which may affect the internal validity of the results. Fifthly, the sample in this study only included married women of reproductive age, which allowed for a focus on the role of marital satisfaction but also means the conclusions may not be generalizable to all women of reproductive age. Future research could compare groups with different marital statuses to more comprehensively analyze the impact of subjective socioeconomic status on the mental health of women of reproductive age.

Conclusion

The research results indicate that the level of SSS affects depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age. Furthermore, this study found that the intervention effect of SSS on depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age is mediated through a sequential pathway involving marital satisfaction and well-being. Specifically, higher SSS enhances marital satisfaction, which in turn increases well-being, ultimately alleviating depressive symptoms. Policies should be implemented to enhance SSS from multiple perspectives, as this is crucial for promoting the construction of a birth-friendly society.

Statements

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Peking University Biomedical Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RH: Writing – original draft. XD: Writing – review & editing. MY: Writing – review & editing. WF: Writing – review & editing. YW: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. WC: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. QG: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. YuH: Writing – review & editing. YoH: Writing – review & editing. AM: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Humanities and Social Sciences Planning Fund of Ministry of Education (22YJAZH081); Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation Project (ZR202211250283).

Acknowledgments

The research team greatly appreciates the funding support and the research participants for their cooperation and support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Alipour Z. Kazemi A. Kheirabadi G. Eslami A. A. (2020). Marital communication skills training to promote marital satisfaction and psychological health during pregnancy: a couple focused approach. Reprod. Health17:23. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-0877-4

2

Anna M. Michael D. (2023). Socioeconomic status and depressive symptoms and suicidality: the role of subjective social status. J. Affect. Disord.326, 36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.078

3

Assari S. Preiser B. Lankarani M. M. Caldwell C. H. (2018). Subjective socioeconomic status moderates the association between discrimination and depression in African American youth. Brain Sci.8:71. doi: 10.3390/brainsci8040071

4

Bavle A. D. Chandahalli A. S. Phatak A. S. Rangaiah N. Kuthandahalli S. M. Nagendra P. N. (2016). Antenatal depression in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J. Psychol. Med.38, 31–35. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.175101

5

Beach S. R. Sandeen E. O’Leary K. D. (1990). Depression in marriage: a model for etiology and treatment. London: Guilford Press.

6

Brandon A. R. Ceccotti N. Hynan L. S. Shivakumar G. Johnson N. Jarrett R. B. (2012). Proof of concept: partner-assisted interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Arch. Womens Ment. Health15, 469–480. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0311-1

7

Callan M. J. Kim H. Matthews W. J. (2015). Predicting self-rated mental and physical health: the contributions of subjective socioeconomic status and personal relative deprivation. Front. Psychol.6:1415. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01415

8

Cao B. Jiang H. Xiang H. Lin B. Qin Q. Zhang F. et al . (2015). Prevalence and influencing factors of depressive symptoms among women of reproductive age in the rural areas of Hubei, China. Public Health129, 465–474. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.01.020

9

Carraturo F. Di Perna T. Giannicola V. Nacchia M. A. Pepe M. Muzii B. et al . (2023). Envy, social comparison, and depression on social networking sites: a systematic review. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ.13, 364–376. doi: 10.3390/ejihpe13020027

10

Chang E. S. Simon M. A. Dong X. (2016). Using community-based participatory research to address Chinese older women's health needs: toward sustainability. J. Women Aging28, 276–284. doi: 10.1080/08952841.2014.950511

11

Chen G. Zhang J. Hu Y. Gao Y. (2022). Gender role attitudes and work-family conflict: a multiple mediating model including moderated mediation analysis. Front. Psychol.13:1032154. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1032154

12

Choi Y. Kim J. H. Park E. C. (2015). The effect of subjective and objective social class on health-related quality of life: new paradigm using longitudinal analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes13:121. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0319-0

13

Coleman N. C. Burnett R. T. Ezzati M. Marshall J. D. Robinson A. L. Pope C. A. (2020). Fine particulate matter exposure and cancer incidence: analysis of SEER cancer registry data from 1992-2016. Environ. Health Perspect.128:107004. doi: 10.1289/EHP7246

14

Colzato L. S. Hommel B. (2014). Effects of estrogen on higher-order cognitive functions in unstressed human females may depend on individual variation in dopamine baseline levels. Front. Neurosci.8:65. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00065

15

Cook W. L. Kenny D. A. (2005). The actor-partner independence model: a model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. Int. J. Behav. Dev.29, 101–109. doi: 10.1080/01650250444000405

16

Cundiff J. M. Matthews K. A. (2017). Is subjective social status a unique correlate of physical health? A meta-analysis. Health Psychol.36, 1109–1125. doi: 10.1037/hea0000534

17

Curhan K. B. Levine C. S. Markus H. R. Kitayama S. Park J. Karasawa M. et al . (2014). Subjective and objective hierarchies and their relations to psychological well-being: a U.S/Japan comparison. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci.5, 855–864. doi: 10.1177/1948550614538461

18

Dai F. Cai Y. Chen M. Dai Y. (2025). Global trends of depressive disorders among women of reproductive age from 1990 to 2021: a systematic analysis of burden, sociodemographic disparities, and health workforce correlations. BMC Psychiatry25, 263–263. doi: 10.1186/s12888-025-06697-4

19

Du W. Luo M. Zhou Z. (2021). A study on the relationship between marital socioeconomic status, marital satisfaction, and depression: analysis based on actor-partner interdependence model (APIM). Appl. Res. Qual. Life17, 1477–1499. doi: 10.1007/s11482-021-09975-x

20

Grant F. Guille C. Sen S. (2013). Well-being and the risk of depression under stress. PLoS One8:e67395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067395

21

Han R. Xu T. Shi Y. Liu W. (2024). The risk role of defeat on the mental health of college students: a moderated mediation effect of academic stress and interpersonal relationships. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot.26, 731–744. doi: 10.32604/ijmhp.2024.054884

22

Hayes A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

23

He C. He Y. Lin Y. Hou Y. Wang S. Chang W. (2025). Associations of temperament, family functioning with loneliness trajectories in patients with breast cancer: a longitudinal observational study. BMC Psychol.13:110. doi: 10.1186/s40359-025-02442-4

24

Hernández-Muñoz A. E. Méndez-Magaña A. Fletes-Rayas A. L. Rangel M. A. García L. T. de Jesús López-Jiménez J. (2022). Subjective well-being’s alterations as risk factors for major depressive disorder during the perimenopause onset: an analytical cross-sectional study amongst Mexican women residing in Guadalajara, Jalisco. BMC Womens Health22:275. doi: 10.1186/s12905-022-01848-1

25

Herrman H. Patel V. Kleling C. Berk M. Buchweitz C. Cuijpers P. et al . (2022). Time for united action on depression: a lancet-world psychiatric association commission. Lancet399, 957–1022. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02141-3

26

Hill R. (1951). Interdisciplinary workshop on marriage and family research. Marriage Fam. Living13, 13–28.

27

Hoebel J. Maske U. E. Zeeb H. Lampert T. (2017). Social inequalities and depressive symptoms in adults: the role of objective and subjective socioeconomic status. PLoS One12:e0169764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169764

28

Horwood C. Hinton R. Haskins L. Luthuli S. Mapumulo S. Rollins N. (2021). I can no longer do my work like how I used to’: a mixed methods longitudinal cohort study exploring how informal working mothers balance the requirements of livelihood and safe childcare in South Africa. BMC Womens Health21:288. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01425-y

29

Huang S. Hou J. Sun L. Dou D. Liu X. Zhang H. (2017). The effects of objective and subjective socioeconomic status on subjective well-being among rural-to-urban migrants in China: the moderating role of subjective social mobility. Front. Psychol.8:819. Published 2017 May 22. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00819

30

Imai K. Keele L. Yamamoto T. (2010). Identification, inference and sensitivity analysis for causal mediation effects. Stat. Sci.25, 51–71. doi: 10.1214/10-STS321

31

Jia L. Antonides G. Liu Z. (2025). Spouses’ personalities and marital satisfaction in Chinese families. Front. Psychol.16:1480570. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1480570

32

Kim H. S. Oh C. Y. Ahn K. H. (2022). A survey on public perceptions of low fertility: a social research panel study. J. Korean Med. Sci.37:e203. Published 2022 Jun 27. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e203

33

Kraus M. W. Keltner D. (2013). Social class rank, essentialism, and punitive judgment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.105, 247–261. doi: 10.1037/a0032895

34

Kraus M. W. Tan J. J. X. Tannenbaum M. B. (2013). The social ladder: a rank-based perspective on social class. Psychol. Inq.24, 81–96. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2013.778803

35

Kwong E. Kwok T. T. Y. Sumerlin T. S. Goggins W. B. Leung J. Kim J. H. (2020). Does subjective social status predict depressive symptoms in Chinese elderly? A longitudinal study from Hong Kong. J. Epidemiol. Community Health74, 882–891. doi: 10.1136/jech-2019-212451

36

Leng X. Han J. Zheng Y. Hu X. Chen H. (2021). The role of a “happy personality” in the relationship of subjective social status and domain-specific satisfaction in China. Appl. Res. Qual. Life16, 1733–1751. doi: 10.1007/s11482-020-09839-w

37

Li J. Wei C. Lu J. (2025). Peer rejection and internet gaming disorder: the mediating role of relative deprivation and the moderating role of grit. Front. Psychol.15:1415666. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1415666

38

Maeda E. Nomura K. Hiraike O. Sugimori H. Kinoshita A. Osuga Y. (2019). Domestic work stress and self-rated psychological health among women: a cross-sectional study in Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med.24:75. doi: 10.1186/s12199-019-0833-5

39

McNeilly E. A. Saragosa-Harris N. M. Mills K. L. Dahl R. E. Magis-Weinberg L. (2022). Reward sensitivity and internalizing symptoms during the transition to puberty: an examination of 9-and 10-year-olds in the ABCD study. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci.58:101172. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2022.101172

40

Mensah A. Adjei N. K. (2020). Work-life balance and self-reported health among working adults in Europe: a gender and welfare state regime comparative analysis. BMC Public Health20:1052. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09139-w

41

Moore S. M. Uchino B. N. Baucom B. R. Behrends A. A. Sanbonmatsu D. (2017). Attitude similarity and familiarity and their links to mental health: an examination of potential interpersonal mediators. J. Soc. Psychol.157, 77–85. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2016.1176551

42

Motrico E. Bina R. Kassianos A. P. le H. N. Mateus V. Oztekin D. et al . (2023). Effectiveness of interventions to prevent perinatal depression: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry82, 47–61. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2023.03.007

43

Mummendey A. Kessler T. Klink A. Mielke R. (1999). Strategies to cope with negative social identity: predictions by social identity theory and relative deprivation theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.76, 229–245. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.76.2.229

44

Nadolu D. Runcan R. Bahnaru A. (2020). Sociological dimensions of marital satisfaction in Romania. PLoS One15:e0237923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237923

45

Nasirpour N. Jafari K. Asgarabad H. M. Salehi M. Amin-Esmaeili M. Rahimi-Movaghar A. et al . (2024). The mediating role of subjective social status in the association between objective socioeconomic status and mental health status: evidence from Iranian national data. Front. Psych.15:1427993. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1427993

46

National Bureau of Statistics (2020). China census yearbook. Beiing: China Statistics Press.

47

Nejatian M. Alami A. Momeniyan V. Delshad Noghabi A. Jafari A. (2021). Investigating the status of marital burnout and related factors in married women referred to health centers. BMC Womens Health21:25. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01172-0

48

Papp L. M. Cummings E. M. Goeke-Morey M. C. (2009). For richer, for poorer: money as a topic of marital conflict in the home. Fam. Relat.58, 91–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00537.x

49

Qian H. Shang W. Zhang S. Pan X. Huang S. Li H. et al . (2024). Trends and predictions of maternal sepsis and other maternal infections among women of childbearing age: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Front. Public Health12, –1428271. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1428271

50

Qiu D. Li Y. Wu Q. An Y. Tang Z. Xiao S. (2023). Patient's disability and caregiver burden among Chinese family caregivers of individual living with schizophrenia: mediation effects of potentially harmful behavior, affiliate stigma, and social support. Schizophrenia9:83. doi: 10.1038/s41537-023-00418-0

51

Rashidi Fakari F. Doulabi M. A. Mahmoodi Z. (2022). Predict marital satisfaction based on the variables of socioeconomic status (SES) and social support, mediated by mental health, in women of reproductive age: path analysis model. Brain Behav.12:e2482. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2482

52

Seligman E. M. (2008). Positive health. Appl. Psychol.57, 3–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00351.x

53

Shu Z. Chen S. Chen H. Chen X. Tang H. Zhou J. et al . (2024). The effects of subjective family status and subjective school status on depression and suicidal ideation among adolescents: the role of anxiety and psychological resilience. PeerJ.12:e18225. doi: 10.7717/peerj.18225

54

Silverman M. E. Burgos L. Rodriguez Z. I. Afzal O. Kalishman A. Callipari F. et al . (2020). Postpartum mood among universally screened high and low socioeconomic status patients during COVID-19 social restrictions in New York City. Sci. Rep.10:22380. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79564-9

55

Smith H. J. Pettigrew T. F. Pippin G. M. Bialosiewicz S. (2012). Relative deprivation: a theoretical and meta-analytic review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev.16, 203–232. doi: 10.1177/1088868311430825

56

Sun L. Xiong J. Zhang C. (2025). The association between network literacy and subjective well-being among middle-aged and older adults. Front. Psychol.16:1590622. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1590622

57

Sweeting H. Hunt K. (2015). Adolescent socioeconomic and school-based social status, smoking, and drinking. J. Adolesc. Health57, 37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.020

58

Tan J. J. X. Kraus M. W. Carpenter N. C. Adler N. E. (2020). The association between objective and subjective socioeconomic status and subjective well-being: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull.146, 970–1020. doi: 10.1037/bul0000258

59

Tan X. Lv M. Fan L. Liang Y. Liu J. (2023). What alleviates depression among medical workers in emergency risk events? The function of subjective social status. Heliyon9:e13762. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13762

60

The Fourth Chinese Women’s Social Status Survey Office (2022). The main data of the fourth China women’s social status survey. Feminist Studies Journal1, 1–129. (in Chinese). Available online at: https://www.wsic.ac.cn/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=show&catid=51&id=11 (Accessed September 13, 2025).

61

Thomas P. A. Liu H. Umberson D. (2017). Family relationships and well-being. Innov. Aging1:igx025. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igx025

62

Tran P. Sturgeon J. A. Nilakantan A. Foote A. Mackey S. Johnson K. (2017). Pain catastrophizing mediates the relationship between trait happiness and depressive symptoms in individuals with current pain. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res.22:e12069. doi: 10.1111/jabr.12069

63

Van de Velde S. Levecque K. Bracke P. (2009). Measurement equivalence of the CES-D 8 in the general population in Belgium: a gender perspective. Arch. Public Health67, 98–111. doi: 10.1186/0778-7367-67-1-15

64

Vincent C. Ménard A. Giroux I. (2025). Cultural determinants of body image: what about the menopausal transition?Healthcare13:76. doi: 10.3390/healthcare13010076

65

Wang W. Chen K. Xiao W. Du J. Qiao H. (2024). Determinants of health poverty vulnerability in rural areas of Western China in the post-poverty relief era: an analysis based on the Anderson behavioral model. BMC Public Health24:459. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-18035-6

66

Wang Y. Xu S. Chen Y. Liu H. (2023). A decline in perceived social status leads to post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in adults half a year after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic: consideration of the mediation effect of perceived vulnerability to disease. Front. Psych.14:1217264. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1217264

67

Wetherall K. Robb K. A. O’Connor R. C. (2018). Social rank theory of depression: a systematic review of self-perceptions of social rank and their relationship with depressive symptoms and suicide risk. J. Affect. Disord.246, 300–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.045

68

Whisman M. A. (2001). “The association between depression and marital dissatisfaction” in Marital and family processes in depression: a scientific foundation for clinical practice. ed. BeachS. R. H. (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association).

69

Wickrama K. A. S. King V. A. O'Neal C. W. Lorenz F. O. (2017). Stressful work trajectories and depressive symptoms in middle-aged couples: moderating effect of marital warmth. J. Aging Health. doi: 10.1177/0898264317736135

70

World Health Organization . Women’s health [EB/OL]. (2018). Available online at: https://www.who.int/zh/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/women-s-health. (Accessed June 14, 2025)

71

Wu Z. Zhang J. Jiang M. Zhang J. Xiao Y. W. (2023). The longitudinal associations between perceived importance of the internet and depressive symptoms among a sample of Chinese adults. Front. Public Health11:1167740. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1167740

72

Xiao Z. Huang J. (2022). The relation between college students’ social anxiety and mobile phone addiction: the mediating role of regulatory emotional self-efficacy and subjective well-being. Front. Psychol.13:861527. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.861527

73

Xie Y. Hu J. (2015). An introduction to the China family panel studies (CFPS). Chin. Sociol. Rev.47, 3–29. doi: 10.2753/CSA2162-0555470101

74

Xiong M. Hu Z. (2022). Relative deprivation and depressive symptoms among Chinese migrant children: the impacts of self-esteem and belief in a just world. Front. Public Health10:1008370. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1008370

75

Yang J. (2025). Elderly care expectation how to influence the fertility desire: evidence from Chinese general social survey data. PLoS One20:e0318628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0318628

76

Yang B. Cai G. Xiong C. Huang J. (2021). Relative deprivation and game addiction in left-behind children: a moderated mediation. Front. Psychol.12:639051. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.639051

77

Yang Y. Luo B. Ren J. Deng X. Guo X. (2023). Marital adjustment and depressive symptoms among Chinese perinatal women: a prospective, longitudinal cross-lagged study. BMJ Open13:e070234. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070234

78

Yang L. Yang Z. Yang J. (2023). The effect of marital satisfaction on the self-assessed depression of husbands and wives: investigating the moderating effects of the number of children and neurotic personality. BMC Psychol.11:163. doi: 10.1186/s40359-023-01200-8

79

Yang G. Zhang L. (2023). Relationship between aging population, birth rate and disposable income per capita in the context of COVID-19. PLoS One18:e0289781. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0289781

80

Yu X. Liang J. (2022). Social norms and fertility intentions: evidence from China. Front. Psychol.13:947134. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.947134

81

Yuan S. U. Yueping L. I. (2022). Relationship between subjective socioeconomic status and sense of gain of health-care reform and the mediating role of self-rated health: a cross-sectional study in China. BMC Public Health22:790. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13106-y

82

Zang E. Bardo A. R. (2019). Objective and subjective socioeconomic status, their discrepancy, and health: evidence from East Asia. Soc. Indic. Res.143, 765–794. doi: 10.1007/s11205-018-1991-3

83

Zhang L. Huang R. Lei J. Liu Y. Liu D. (2024). Factors associated with stress among pregnant women with a second child in Hunan province under China’s two-child policy: a mixed-method study. BMC Psychiatry24:157. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-05604-7

84

Zhang N. Qi J. Liu Y. Liu X. Tian Z. Wu Y. et al . (2024). Relationship between big five personality and health literacy in elderly patients with chronic diseases: the mediating roles of family communication and self-efficacy. Sci. Rep.14:24943. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-76623-3

85

Zhao R. Wang J. Lou J. Liu M. Deng J. Huang D. et al . (2024). The effect of education level on depressive symptoms in Chinese older adults-parallel mediating effects of economic security level and subjective memory ability. BMC Geriatr.24:635. doi: 10.1186/s12877-024-05233-5

86

Zhen Z. Tang D. Wang X. Feng Q. (2024). The impact of digital technology on health inequality: evidence from China. BMC Health Serv. Res.24:1531. doi: 10.1186/s12913-024-12022-8

87

Zhou J. Guo W. Ren H. (2023). Subjective social status and health among older adults in China: the longitudinal mediating role of social trust. BMC Public Health23:630. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15523-z

Summary

Keywords

women of reproductive age, subjective socioeconomic status, marital satisfaction, well-being, depressive symptoms

Citation

Han R, Ding X, Yang M, Feng W, Wang Y, Cai W, Gao Q, Han Y, Hu Y and Ma A (2025) The association between subjective socioeconomic status and depressive symptoms in women of reproductive age: the chain mediating effects of marital satisfaction and well-being. Front. Psychol. 16:1715488. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1715488

Received

29 September 2025

Revised

06 November 2025

Accepted

20 November 2025

Published

05 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

María Cantero-García, Universidad a Distancia de Madrid, Spain

Reviewed by

María Rueda-Extremera, Universidad a Distancia de Madrid, Spain

María Provencio, Universidad a Distancia de Madrid, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Han, Ding, Yang, Feng, Wang, Cai, Gao, Han, Hu and Ma.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Youli Hu, 13625369666@163.com; Anning Ma, yxyman@126.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.