Abstract

Introduction:

Social alienation is an important issue for patients with cancer. However, the interrelationships among factors influencing social alienation in cancer patients have not been sufficiently investigated. The study aimed to clarify the relationships among social alienation, illness perception, fear of cancer progression, and perceived social support in patients with cancer.

Methods:

A cross-sectional descriptive survey was conducted with 244 cancer patients recruited through convenience sampling from a tertiary hospital in Changsha, China. Data were collected using the General Information Questionnaire, Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire, General Alienation Scale, Fear of Progression Questionnaire-Short Form, and Perceived Social Support Scale.

Results:

The findings show that the mean social alienation score among cancer patients was 33.11 ± 7.95. Model fit indices indicated a good fit. Illness perception and perceived social support have a direct and significant negative impact on social alienation, with path coefficients of −0.19 and −0.25, respectively. Fear of cancer progression has a direct and significant positive effect on social alienation, with a path coefficient of 0.45. Additionally, the results of the mediation analysis indicate that illness perception indirectly influences social alienation through its effects on fear of cancer progression and perceived social support; employment status indirectly influences social alienation through illness perception; disease stage indirectly influences social alienation through illness perception and fear of cancer progression.

Conclusion:

This suggests that illness perception, fear of cancer progression, and perceived social support are key factors influencing social alienation in cancer patients. These factors exerted both direct and indirect effects on each other and on social alienation.

1 Introduction

Cancer has been one of the most significant global public health challenges in the 21st century. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer, there were approximately 19.98 million new cancer cases worldwide in 2022, including about 4.83 million in China (Wang et al., 2024). The report Cancer Statistics, 2025 indicates that the 5-year relative survival rate for cancer worldwide during the period 2014–2020 was approximately 69% (Siegel et al., 2025). However, cancer and its treatment exert complex influences on patients’ physical, psychological, and social functioning.

Social alienation refers to a state of deficiency or detachment within an individual’s social network, encompassing both subjective feelings of loneliness and objective social withdrawal (Umberson and Donnelly, 2023). And it is closely linked to psychological status and health risks. The side effects of treatment, economic burdens, and disruptions in social relationships gradually undermine the social functioning of cancer patients. A cohort study reported that 27∼30% of young cancer patients experienced social alienation (Li et al., 2024). Such alienation contributes to symptoms of depression and anxiety, and in severe cases, suicidal ideation (Li et al., 2024; Ernst et al., 2021). Moreover, social alienation may promote tumor growth, reshape the tumor immune microenvironment, and lead to immunosuppression, thereby increasing cancer-specific mortality (Miaskowski et al., 2021; Trachtenberg et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2024). Surveys indicate that cancer patients have a strong need for social support, yet this need is often neglected (Guo and Cui, 2025).

Illness perception refers to an individual’s subjective understanding and evaluation of various aspects of a disease, such as its causes, symptoms, and consequences (Striberger et al., 2020). Studies have shown that negative illness perceptions are significantly associated with poorer psychological outcomes and quality of life (Jabbarian et al., 2021). Among breast cancer patients, negative illness perceptions impair disease management and reduce quality of life (Li et al., 2025). Furthermore, negative perceptions of illness can heighten patients’ anxiety and fear regarding their condition, potentially leading to self-stigmatization, increased social avoidance, social isolation, and the formation of a vicious cycle (Miaskowski et al., 2021; Fox et al., 2023).

Fear of disease progression refers to patients’ persistent fear of disease worsening or recurrence, often manifested as hypervigilance toward physical symptoms and avoidant behaviors (Berg et al., 2011). Among cancer patients, fear of disease progression typically manifests as concern about cancer worsening, and this fear is closely associated with increased risks of anxiety and depression (Sharpe et al., 2022). Severe distress related to fear of progression may impair cognitive functioning and directly reduce quality of life. A study on hemodialysis patients found that fear of disease progression mediated the relationship between illness perception and social alienation (Zhu et al., 2024).

Perceived social support refers to an individual’s awareness of receiving psychological and material support from family, friends, and broader social networks (Jiang et al., 2021). Studies have demonstrated that social support significantly influences patients’ quality of life. Moreover, social support in cancer care is modifiable: supportive care interventions can improve quality of life (Li et al., 2024). A cross-national study further revealed that higher perceived social support mitigates fear of illness and reduces social alienation (Kim and Jung, 2020).

The Multi-factor Model of Psychological Stress, proposed by Jiang (2014) through long-term empirical research, incorporates multiple interacting systems, including life events, cognitive appraisal, coping strategies, social support, personality traits, and psychosomatic responses, with cognition as the central element. Existing studies suggest that illness perception, fear of disease progression, and perceived social support are closely related to social alienation (Zhu et al., 2024; Kim and Jung, 2020). Given that our research focuses on cancer patients, we will specifically define the fear of disease progression as the fear of cancer progression. Specifically, illness perception represents cancer patients’ direct cognition of disease, fear of progression constitutes a psychological reaction based on that cognition, and perceived social support represents the social dimension. Therefore, grounded in this theoretical framework, the present study incorporated these three variables into a structural equation model (SEM) for analysis.

Although social alienation plays a critical role in psychological stress and mental health among cancer patients, substantial gaps remain in understanding its interrelationships with illness perception, fear of cancer progression, and perceived social support, as well as their implications for clinical practice. Therefore, based on a literature review, we developed a hypothetical model incorporating illness perception, fear of cancer progression, perceived social support, and social alienation. We hypothesize that Illness Perception will negatively affect Social Alienation, and this relationship will be mediated by Fear of Cancer Progression and Perceived Social Support. Furthermore, Fear of Cancer Progression will directly positively influence Social Alienation, while Perceived Social Support will directly negatively influence Social Alienation. The primary aim of this study was to test this model using structural equation modeling, in order to clarify the relationships among these factors in cancer patients and provide evidence for the development of targeted interventions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Research question

Based on a multi-factor model of psychological stress, this study aims to examine the negative impact of Illness Perception on Social Alienation, as well as the mediating roles of Fear of Cancer Progression and Perceived Social Support. Therefore, the following research questions are proposed:

-

Research Question 1: Does Illness Perception have a negative impact on Social Alienation ?

-

Research Question 2: Is the effect of Illness Perception on Social Alienation mediated by Fear of Cancer Progression and Perceived Social Support?

-

Research Question 3: How do Fear of Cancer Progression and Perceived Social Support affect Social Alienation?

2.2 Design and sample

This study is a descriptive cross-sectional study. We used convenience sampling to recruit cancer patients from a tertiary-level hospital in Changsha, China. Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients diagnosed with cancer by cytology or histology; (2) Age ≥ 18 years; (3) Patients who had completed initial anticancer treatments such as surgery or radiotherapy/chemotherapy and were in the follow-up period; (4) Patients who could read or write; (5) Patients who were aware of their condition and consented to participate in this study. Exclusion criteria: (1) Cancer metastasis or recurrence, given that patients with metastatic or recurrent cancer present with more severe disease, heavier treatment burdens, and greater psychological stress, such patients were excluded from the study to ensure clearer and more targeted research findings; (2) Concurrent severe chronic diseases; (3) History of mental illness or communication barriers.

Typically, a median sample size of 200 is recommended for SEM analysis (Kline, 2011). An a priori sample size calculator for SEM was applied, which is popular and publicly designed for calculating SEM sample sizes1 (Soper, 2015). The minimum sample size with a moderate effect (0.3), at a power value of 0.95, including 4 latent and 20 observed variables (all observed indicators and sociodemographic variables), and with an α of 0.05 was calculated as 207. Considering 10% dropout, we chose a minimum sample size of 227.

2.3 Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Nursing of Hunan University of Chinese Medicine. All eligible participants provided informed consent before completing the questionnaire. They were informed of their rights in the study, including their right to withdraw from the study at any time.

2.4 Measurements

2.4.1 General Information Questionnaire

A self-made general survey questionnaire was used to collect demographic data on patients, including age, gender, educational attainment, marital status, employment status, monthly household income, medical expenses, disease stage, and comorbidities.

2.4.2 Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire

The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIQP) is used to measure patients’ self-perception of their illness. The questionnaire was developed by Broadbent et al. (2005) and translated into Chinese by Ma et al. (2015). It consists of 9 items (impact of illness, course of illness, personal control, treatment control, symptoms experienced, concern about illness, understanding of illness, emotions, perceived cause of illness) and 3 dimensions (illness cognition, emotions, understanding ability). The 9th item is an open-ended question, while the remaining 8 items are scored on a 0–10 point scale. For quantitative data analysis, this study focuses on the scores of the first 8 items to assess patients’ illness perception, with a total score of 80 points. Higher scores indicate that patients perceive their disease symptoms as more severe. The Cronbach’s α for this scale in this study is 0.929.

2.4.3 General Alienation Scale

The General Alienation Scale (GAS) is used to assess patients’ feelings of social alienation. The scale was developed by Pattison (1978) and translated into Chinese by Chen et al. (2015) in 2015. The scale consists of 15 items across 4 dimensions (alienation from others, feelings of powerlessness, self-alienation, and feelings of meaninglessness), using a 4-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 1 to 4, corresponding to “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” A higher total score indicates a higher degree of social alienation in patients. The Cronbach’s α for this scale in the present study was 0.907.

2.4.4 Fear of Progression Questionnaire Short Form

The Fear of Progression Questionnaire Short Form (FoP-Q-SF) was developed by Mehnert et al. (2009) based on the FoP-Q, and translated into Chinese by Wu et al. (2015). This study used the questionnaire to assess patients’ fear of cancer progression. The questionnaire consists of 12 items, including 2 dimensions: physiological health factors and social and family factors. A 5-point Likert scale was used, with scores ranging from 1 to 5, representing “never” to “always.” A higher total score indicates greater fear of cancer progression. The Cronbach’s α for this questionnaire in this study was 0.940.

2.4.5 Perceived Social Support Scale

The Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS) is used to measure patients’ perceptions of the level of support they receive from family, friends, and other individuals. Originally developed by Zimet et al. (1988), it was revised into Chinese by Jiang (1999). The scale consists of three dimensions and 12 items, using a 7-point scoring method, with scores ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A higher total score indicates a higher level of perceived social support. The Cronbach’s α for this questionnaire in this study was 0.958.

2.5 Data collection

Convenience sampling was used, and the data were collected from a tertiary-level hospital in Changsha between May 2024 and June 2025. The researchers first contacted the head nurse of the hospital’s oncology department and explained the purpose and methods of the study in detail. After obtaining the head nurse’s consent, two researchers entered the ward and collected data through the “QuestionStar” electronic questionnaire platform. Based on the time researchers spent completing the questionnaire in advance, we set 5 min as the average completion time. A total of 245 questionnaires were distributed, and one patient declined to participate in the study. Ultimately, 244 valid questionnaires were collected.

2.6 Data analysis

Descriptive and correlation analyses were performed using SPSS 27.0 software. Quantitative data were expressed as , and categorical data were expressed as frequencies and proportions. Pearson correlation analysis was used to describe the correlation between two variables. Independent samples t-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to analyze the effects of sociodemographic factors on intergroup differences in variable scores. Additionally, we incorporate sociodemographic factors identified in Table 1 as exogenous observed variables into the SEM to predict latent variables (Illness Perception, Fear of Cancer Progression, Social Alienation and Perceived Social Support). AMOS 26.0 was used to construct the SEM. The fit index, incremental fit index, normality fit index, and goodness-of-fit index were used as validation indicators for the SEM. If all index values were >0.90, the model was considered to have a good fit. A root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) <0.05 indicated good fit; <0.08 indicated the fit results were within an acceptable range. Approximate maximum likelihood estimation was used to estimate regression coefficients and effect sizes. Based on the significance test results of path coefficients and model fit indices, the model was revised to optimize its parsimony. P < 0.05 indicates statistically significant differences (Brown, 2006; Hu and Bentler, 1999).

TABLE 1

| Variables | N (%) | BIQP | FoP-Q-SF | PSSS | GAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| 18∼30 | 23 (9.4) | 42.04 ± 19.75 | 38.87 ± 10.06 | 57.83 ± 17.98 | 32.61 ± 9.05 |

| 31∼40 | 15 (6.1) | 56.40 ± 15.89* | 37.13 ± 10.59 | 69.40 ± 16.30 | 32.13 ± 8.89 |

| 41∼50 | 26 (10.6) | 46.85 ± 17.64 | 33.19 ± 9.36 | 63.81 ± 14.55 | 34.92 ± 8.05 |

| 51∼60 | 79 (32.4) | 53.89 ± 14.46 | 35.03 ± 11.57 | 61.94 ± 13.55 | 33.10 ± 8.10 |

| 61∼70 | 64 (26.2) | 55.88 ± 10.65 | 35.08 ± 8.31 | 66.73 ± 12.80 | 33.89 ± 7.48 |

| ≥71 | 37 (15.2) | 54.05 ± 14.92 | 31.27 ± 11.37 | 64.24 ± 12.00 | 31.19 ± 7.34 |

| Religious belief | |||||

| None | 222 (91.0) | 52.53 ± 15.27 | 34.53 ± 10.63 | 63.86 ± 13.93 | 32.91 ± 8.05 |

| Yes | 22 (9.0) | 54.68 ± 10.86* | 37.14 ± 7.93 | 63.36 ± 15.63 | 35.09 ± 6.87 |

| Educational level | |||||

| Primary school or below | 32 (13.1) | 57.25 ± 9.48* | 33.47 ± 7.27 | 62.63 ± 13.84 | 31.66 ± 7.44 |

| Middle school | 83 (34.0) | 51.28 ± 13.50 | 33.64 ± 11.04 | 62.49 ± 13.64 | 34.75 ± 7.69 |

| High school or technical secondary school | 64 (26.2) | 56.34 ± 14.89 | 35.17 ± 10.22 | 65.75 ± 13.80 | 32.03 ± 6.91 |

| College | 53 (21.7) | 48.21 ± 18.16 | 35.79 ± 10.90 | 64.21 ± 15.87 | 32.57 ± 9.16 |

| Master’s degree or above | 12 (4.9) | 51.25 ± 15.14 | 39.33 ± 11.99 | 64.08 ± 14.00 | 33.75 ± 9.94 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Unmarried | 23 (9.4) | 43.96 ± 17.32 | 39.43 ± 9.96 | 58.26 ± 14.76 | 33.87 ± 8.74 |

| Married | 205 (84.0) | 53.25 ± 14.70 | 34.29 ± 10.45 | 64.68 ± 14.05 | 33.08 ± 7.93 |

| Other | 16 (6.6) | 58.50 ± 8.55* | 34.19 ± 9.76 | 60.75 ± 11.52 | 32.38 ± 7.64 |

| Employment status | |||||

| Employed | 50 (20.5) | 47.20 ± 18.87 | 36.36 ± 11.46* | 63.22 ± 15.37 | 32.40 ± 8.31 |

| Unemployed | 36 (14.8) | 43.61 ± 17.75 | 30.81 ± 11.26 | 62.61 ± 16.97 | 30.92 ± 8.28 |

| Other | 158 (64.8) | 56.54 ± 10.95* | 35.16 ± 9.72 | 64.28 ± 12.94* | 33.83 ± 7.71 |

| Monthly household income (CNY) | |||||

| ≤2000 | 43 (17.6) | 54.88 ± 12.81 | 35.26 ± 10.36 | 62.40 ± 15.43 | 34.30 ± 10.36 |

| 2000–5000 | 79 (32.4) | 50.62 ± 16.28* | 34.77 ± 11.28 | 61.48 ± 13.45 | 34.29 ± 7.57 |

| 5000–8000 | 68 (17.9) | 49.78 ± 16.09 | 34.09 ± 10.38 | 64.53 ± 14.38 | 31.87 ± 7.08 |

| ≥8000 | 54 (22.1) | 57.78 ± 11.24 | 35.22 ± 9.45 | 67.46 ± 12.90 | 31.98 ± 7.17 |

| Disease stage | |||||

| I | 56 (23.0) | 48.98 ± 18.01 | 38.02 ± 11.34* | 63.16 ± 17.17 | 33.68 ± 10.30 |

| II | 58 (23.8) | 50.43 ± 12.86 | 35.29 ± 9.07 | 61.17 ± 12.79 | 34.05 ± 7.33 |

| III | 63 (25.8) | 49.94 ± 16.24 | 29.68 ± 10.06 | 62.19 ± 13.28 | 32.75 ± 6.89 |

| IV | 67 (27.5) | 60.45 ± 8.66* | 36.37 ± 9.53* | 68.18 ± 12.13* | 32.15 ± 7.20 |

| Medical burden | |||||

| No burden | 18 (7.4) | 52.00 ± 19.24 | 30.67 ± 12.80 | 65.61 ± 20.19 | 27.61 ± 9.61 |

| Minimal burden | 64 (26.2) | 49.66 ± 18.02 | 32.27 ± 10.07 | 65.64 ± 13.50 | 32.56 ± 6.73 |

| Moderate burden | 117 (48.0) | 52.87 ± 12.80 | 36.18 ± 10.50 | 63.39 ± 12.50 | 34.22 ± 8.12* |

| Heavy burden | 45 (18.4) | 56.98 ± 12.55 | 36.29 ± 8.83* | 61.60 ± 15.80 | 33.18 ± 7.74 |

Relationship between sociodemographic characteristics and variable scores (n = 244).

*P < 0.05. BIQP, Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire; FoP-Q-SF, Fear of Progression Questionnaire Short Form; PSSS, Perceived Social Support Scale; GAS, General Alienation Scale.

3 Results

3.1 Sample characteristics and its difference among variable scores in the model

A total of 245 patients was recruited for the survey, and 244 cases were included in the statistical analysis (1 patient refused to complete the questionnaire during the survey). Age, religious beliefs, marital status, educational attainment, employment status, monthly household income, disease stage, and medical burden influenced one or more latent variables (Table 1). Therefore, these sociodemographic variables were included as covariates in the model.

3.2 Measured variables and their relationships

The mean total scores for BIQP, FoP-Q-SF, PSSS, and GAS among cancer patients were 52.72 ± 14.92, 34.77 ± 10.43, 63.82 ± 14.06, and 33.11 ± 7.96, respectively. Statistical data for each dimension are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2

| Variables | Mean | SD | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIQP | 52.72 | 14.92 | 54.50 | 0.00–80.00 |

| Illness representation | 32.67 | 9.80 | 34.00 | 0.00–50.00 |

| Emotions | 13.47 | 4.09 | 14.00 | 0.00–20.00 |

| Comprehensibility | 6.58 | 2.13 | 7.00 | 0.00–10.00 |

| FoP-Q-SF | 34.77 | 10.43 | 36.00 | 12.00–60.00 |

| Fear of physical health | 18.57 | 5.44 | 18.00 | 6.00–30.00 |

| Fear of social and family consequences | 16.20 | 5.64 | 16.00 | 6.00–30.00 |

| PSSS | 63.82 | 14.06 | 65.00 | 12.00–84.00 |

| Family support | 22.60 | 4.64 | 23.00 | 4.00–28.00 |

| Friend support | 20.92 | 5.38 | 22.00 | 4.00–28.00 |

| Other support | 20.30 | 5.38 | 20.00 | 4.00–28.00 |

| GAS | 33.11 | 7.96 | 33.00 | 15.00–60.00 |

| Alienation from others | 9.86 | 3.31 | 10.00 | 5.00–20.00 |

| Powerlessness | 9.84 | 2.05 | 10.00 | 4.00–16.00 |

| Self-alienation | 6.71 | 2.07 | 7.00 | 3.00–12.00 |

| Meaninglessness | 6.69 | 1.64 | 7.00 | 3.00–12.00 |

Descriptive statistics of measured variables (n = 244).

Patients’ perception of the disease and fear of cancer progression were significantly positively correlated with perceived levels of social support; patients’ feelings of social isolation were significantly positively correlated with fear of cancer progression and significantly negatively correlated with perceived levels of social support. Additionally, there was no significant relationship between patients’ perception of the disease and feelings of social isolation, or between fear of cancer progression and perceived levels of social support (Table 3).

TABLE 3

| Variables | BIQP | FoP-Q-SF | PSSS | GAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIQP | 1.000 | – | – | – |

| FoP-Q-SF | 0.462a | 1.000 | – | – |

| PSSS | 0.251a | 0.031 | 1.000 | – |

| GAS | 0.069 | 0.356a | −0.256a | 1.000 |

Correlations among the measured variables (n = 244).

a P < 0.01.

3.3 SEM of measured variables

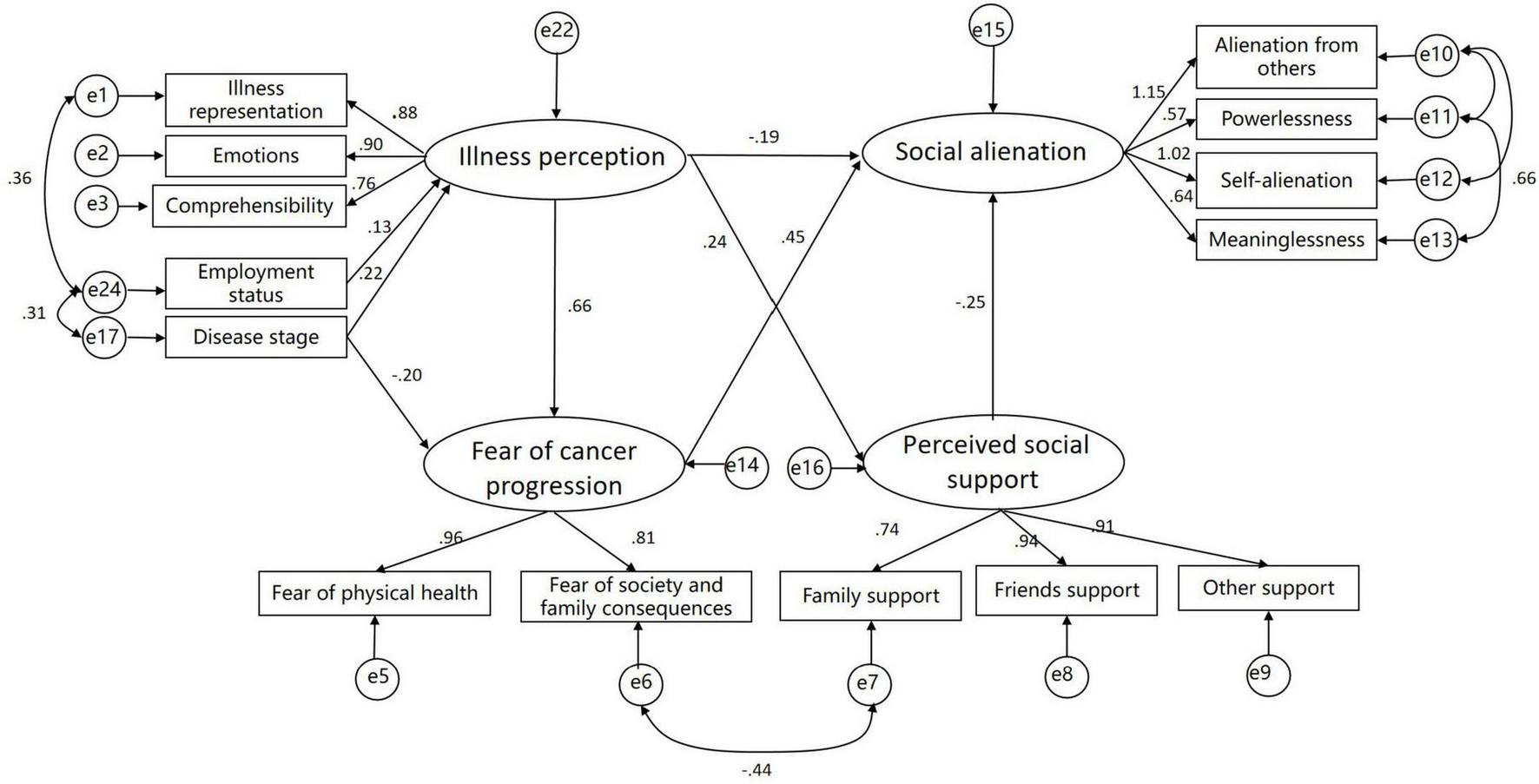

The hypothetical model (Figure 1) does not fit the data well, we modified the model (Figure 2) based on the correction index and deleted paths with small standardized coefficients (absolute value < 0.1). Therefore, the following paths were removed: Religious belief→Illness perception, Age→Illness perception, Marital status→Illness perception, Educational level→Illness perception, Monthly household income→Illness perception, Disease stage→Perceived social support. Although the modified model showed significant differences (P < 0.05), other indicators showed that it fit well (Table 4).

FIGURE 1

The hypothetical model.

FIGURE 2

The modified model.

TABLE 4

| Model | CMIN(P) | DF | CMIN/DF | GFI | NFI | IFI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | >0.05 | <3 | 0.9–1 | 0.9–1 | 0.91 | 0.9–1 | <0.08 | |

| Hypothetical | 781.084 (0.000) | 161 | 4.851 | 0.710 | 0.713 | 0.758 | 0.755 | 0.126 |

| Modified | 186.466 (0.000) | 65 | 2.869 | 0.901 | 0.918 | 0.945 | 0.945 | 0.088 |

SEM goodness-of-fit evaluation results.

Structural equation model indicates that illness perception and perceived social support have a direct and significant negative impact on social alienation. Although correlation analysis revealed no significant association between patients’ disease cognition and social isolation (Table 3), SEM uncovered a direct negative relationship between the two (Table 5). This discrepancy likely stems from other complex pathways obscuring the true association between these variables in the correlation analysis. Therefore, SEM must be employed to explore the intricate mechanisms underlying these variables. Fear of cancer progression has a direct and significant positive effect on social alienation (Table 5). Additionally, the results of the mediation analysis indicate that illness perception indirectly influences social alienation through its effects on fear of cancer progression and perceived social support; employment status indirectly influences social alienation through illness perception; disease stage indirectly influences social alienation through illness perception and fear of cancer progression (Table 6).

TABLE 5

| Pathway | Non-standardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | SEs | Critical ratio | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social alienation ← Illness perception | −0.436 | −0.187 | 0.154 | −2.834 | 0.005 |

| Social alienation ← Fear of cancer progression | 0.367 | 0.449 | 0.055 | 6.690 | <0.001 |

| Social alienation ← Perceived social support | −0.191 | −0.247 | 0.038 | −4.973 | <0.001 |

| Perceived social support ← Illness perception | 0.740 | 0.245 | 0.210 | 3.527 | <0.001 |

| Fear of cancer progression ← Illness perception | 1.885 | 0.659 | 0.223 | 8.441 | <0.001 |

SEM path coefficients.

TABLE 6

| Endogenous variables | Exogenous variables | Standardized direct effects | Standardized indirect effects | Standardized total effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social alienation | Illness perception | −0.187 | 0.236 | 0.049 |

| Fear of cancer progression | 0.449 | 0 | 0.449 | |

| Perceived social support | −0.247 | 0 | −0.247 | |

| Disease stage | 0 | −0.780 | −0.780 | |

| Employment status | 0 | 0.006 | 0.006 | |

| Perceived social support | Illness perception | 0.245 | 0 | 0.245 |

| Fear of cancer progression | Illness perception | 0.659 | 0 | 0.659 |

Standardized direct, indirect, and total effects for the modified model.

4 Discussion

4.1 Current state of social alienation

In this survey, the mean social alienation score among cancer patients was 33.11 ± 7.96, indicating a medium-to-high level. This result is consistent with findings from studies on other chronic diseases in China (Xu et al., 2024; Li et al., 2022). Research conducted in other countries has shown that more than 26.6% of patients experience psychosocial distress (Baye et al., 2023). Collectively, these studies suggest that patients with cancer and other chronic illnesses commonly experience social alienation. The underlying reasons may be related to disease itself and treatment-related side effects, which restrict physical functioning and alter appearance, thereby reducing patients’ social capacity and willingness (Fox et al., 2023). In addition, cancer patients often suffer from elevated psychological stress and poor mental health, both of which further exacerbate social alienation (Li et al., 2024).

4.2 SEM analysis

This study employed SEM to examine the relationships among social alienation, illness perception, fear of cancer progression, and perceived social support in Chinese cancer patients. Our findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the pathways influencing social alienation and support the development of interventions targeting social alienation in this population.

4.2.1 Illness perception

This study found that illness perception had a direct impact on social alienation. Negative cognitions regarding disease severity, treatment side effects, and prognosis increased patients’ psychological burden (Kim et al., 2022). It reduced their motivation to socialize, resulting in objective social withdrawal behaviors and subjective feelings of loneliness. Additionally, illness perception indirectly influenced social alienation via fear of cancer progression. Negative cognitions not only directly led patients to reduce social contact but also heightened fear of progression, producing psychological stress (Sharpe et al., 2023). Such fear further encouraged avoidance of potentially health-threatening social situations, thereby intensifying social alienation. Psychological stress can activate the neuroendocrine system, increase inflammatory cytokine levels, and subsequently impair brain function, which reinforces social withdrawal (Kim et al., 2022). Evidence suggests that professional psychological interventions helping patients distinguish realistic risks from excessive worries may foster more accurate illness perceptions, enhance quality of life, and reduce social alienation (Barello et al., 2022). Hence, empowerment education focusing on emotion regulation and stress relief may help patients cope positively with negative emotions.

Moreover, this study found that perceived social support mitigated the level of social alienation. Perceived social support is a core protective factor that can improve patients’ social connectedness. Specifically, perceived support is negatively associated with limbic system activity, reducing negative emotional responses and enabling patients to feel “respected” and “accepted,” thereby decreasing social avoidance and promoting active social engagement (Borgers et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2021). Illness perception also exerted an indirect effect on social alienation through perceived social support. Evidence indicates that positive illness perceptions are independently associated with higher levels of perceived social support (Mathieu et al., 2024). Greater perceived support buffers the impact of negative illness cognitions and emotions, reducing loneliness, whereas insufficient support amplifies these effects and aggravates alienation. Healthcare providers can act as bridges between patients and social support systems by encouraging open communication with family and friends and organizing online/offline peer-support groups to facilitate emotional support.

4.2.2 Disease stage

This study revealed that disease stage indirectly affected social alienation through illness perception or fear of cancer progression. As an objective clinical indicator, disease stage directly shapes patients’ subjective perceptions of disease severity and prognosis. A higher tumor stage implies greater disease severity and poorer prognosis, thereby heightening patients’ sense of threat, including concerns about survival rates and the emergence of negative emotions such as depression and anxiety (Liu et al., 2023). It also directly intensifies fear of cancer progression, ultimately leading to social withdrawal and increased social alienation.

4.2.3 Employment status

This study demonstrated that employment status indirectly influenced social alienation through illness perception. Employment itself represents an important form of social support (Leep Hunderfund et al., 2022). Cancer patients often face substantial financial burdens, and work serves as a crucial source of income. Job loss sharply reduces income, creating financial stress, while an unsupportive work environment may foster workplace exclusion (Carlson et al., 2022). Patients often attribute these difficulties to their illness, thereby forming erroneous negative perceptions of their condition. They view the disease as a devastating economic event and a core factor threatening their social role positioning, believing it robs them of normal working capacity, diminishes their self-worth, and lowers their social standing. Consequently, they adopt avoidant coping behaviors and reduce social engagement. Healthcare providers can help link patients with community services, charitable foundations, and government subsidies to alleviate financial stress.

4.3 Limitations

This study has three limitations: (1) The sample was drawn from a single hospital in Changsha, China, which may limit generalizability to all cancer patients. (2) The cross-sectional design restricts causal inference among variables. (3) Convenience sampling may introduce selection bias, thereby limiting the validity of research findings to some extent. (4) The SEM does not encompass all potential factors that may influence social alienation among cancer patients, such as common psychological states like depression, anxiety, and stress. In the future, we will incorporate patients’ psychological states into structural equation modeling for analysis, thereby deepening our research into the factors influencing social alienation among cancer patients. (5) We did not perform stratified analysis based on diagnosis timing. Patients diagnosed at a later stage may face more frequent treatments and a heavier disease burden. These factors may exacerbate patients’ feelings of social alienation, thereby influencing study outcomes.

5 Conclusion

In summary, this study constructed a model of influencing factors of social alienation in cancer patients using SEM. By analyzing the effects of illness perception, fear of cancer progression, and perceived social support on social alienation, it clarified the pathways and magnitudes of relationships among variables. The findings of this study hold significant implications for the social care of cancer patients at all stages who meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria, providing valuable reference for developing interventions aimed at alleviating patients’ social alienation and improving their mental health. This model highlights the need for clinicians and nurses to focus on the determinants of social alienation in care, with targeted strategies to reduce alienation and enhance patients’ quality of life.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics statement

In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, this study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Approval Committee of the School of Nursing of Hunan University of Chinese Medicine (Approval No. ZYYHLLL202506008) before data collection. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Participants took part voluntarily and anonymously. All the participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Author contributions

YH: Writing – original draft, Data curation. YeH: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. XL: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SL: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. FX: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. OC: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Conceptualization, Supervision. JZ: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Youth Project of the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of the Ministry of Education (23YJCZH294), Department of Education of Hunan Province (22B0366), Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2023JJ40491), and Natural Science Foundation Project of Hunan University of Chinese Medicine (2022XJZKC019).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants and research staff involved in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. This study involved the use of ChatGPT-5 to assist in translation tasks. All AI-generated outputs were manually reviewed and edited by the researchers to ensure accuracy, professionalism, and compliance with academic standards.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

SEM, structural equation model; BIQP, Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire; FoP-Q-SF, Fear of Progression Questionnaire Short Form; PSSS, Perceived Social Support Scale; GAS, General Alienation Scale.

References

1

Barello S. Anderson G. Acampora M. Bosio C. Guida E. Irace V. et al (2022). The effect of psychosocial interventions on depression, anxiety, and quality of life in hemodialysis patients: A systematic review and a meta-analysis.Int. Urol. Nephrol.55897–912. 10.1007/s11255-022-03374-3

2

Baye A. Bogale S. Delie A. Melak Fekadie M. Wondyifraw H. Tigabu M. et al (2023). Psychosocial distress and associated factors among adult cancer patients at oncology: A case of Ethiopia.Front. Oncol.13:1238002–1238002. 10.3389/fonc.2023.1238002

3

Berg P. Book K. Dinkel A. Henrich G. Marten-Mittag B. Mertens D. et al (2011). [Fear of progression in chronic diseases].Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol.6132–37. 10.1055/s-0030-1267927

4

Borgers T. Rinck A. Enneking V. Klug M. Winter A. Gruber M. et al (2024). Interaction of perceived social support and childhood maltreatment on limbic responsivity towards negative emotional stimuli in healthy individuals.Neuropsychopharmacology491775–1782. 10.1038/s41386-024-01910-6

5

Broadbent E. Petrie K. Main J. Weinman J. (2005). The brief illness perception questionnaire.J. Psychosom. Res.60631–637. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020

6

Brown T. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research.New York, NY: Guilford Press.

7

Carlson M. Fradgley E. Bridge P. Taylor J. Morris S. Coutts E. et al (2022). The dynamic relationship between cancer and employment-related financial toxicity: An in-depth qualitative study of 21 Australian cancer survivor experiences and preferences for support.Support Care Cancer303093–3103. 10.1007/s00520-021-06707-7

8

Chen W. Zhao S. Luo J. Zhang J. (2015). Validity and reliability of the general alienation scale in college students.Chinese Mental Health J.29780–784. 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2015.10.013

9

Ernst M. Brähler E. Wild P. Faber J. Merzenich H. Beutel M. (2021). Loneliness predicts suicidal ideation and anxiety symptoms in long-term childhood cancer survivors.Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol.21:100201. 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.10.001

10

Fox R. Armstrong G. Gaumond J. Vigoureux T. Miller C. Sanford S. et al (2023). Social isolation and social connectedness among young adult cancer survivors: A systematic review.Cancer1292946–2965. 10.1002/cncr.34934

11

Guo F. Cui J. (2025). Current status and optimization strategies for comprehensive cancer care management.Natl. Nat. Sci. Foundation China3970–79. 10.16262/j.cnki.1000-8217.20250227.006

12

Hu L. Bentler P. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives.Struct. Equ. Model.61–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118

13

Jabbarian L. Rietjens J. Mols F. Oude Groeniger J. van der Heide A. Korfage I. (2021). Untangling the relationship between negative illness perceptions and worse quality of life in patients with advanced cancer-a study from the population-based PROFILES registry.Support Care Cancer296411–6419. 10.1007/s00520-021-06179-9

14

Jiang Q. (1999). “Perceived social support scale (Psss),” in Manual for the Mental Health Assessment Scale, (Beijing: China Journal of Mental Health Publishing House).

15

Jiang Q. (2014). “Stress system model: Theory and practice,” in Paper presented at the The 17th National Conference on Psychology, (Beijing).

16

Jiang T. Yakin S. Crocker J. Way B. (2021). Perceived social support-giving moderates the association between social relationships and interleukin-6 levels in blood.Brain Behav. Immun.10025–28. 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.11.002

17

Kim H. Jung J. (2020). Social isolation and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-national analysis.Gerontologist61103–113. 10.1093/geront/gnaa168

18

Kim I. Lee J. Park S. (2022). The Relationship between stress, inflammation, and depression.Biomedicines101929–1929. 10.3390/biomedicines10081929

19

Kline R. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. methodology in the social sciences, 3rd Edn. New York: Guilford Press.

20

Leep Hunderfund A. West C. Rackley S. Dozois E. Moeschler S. Vaa Stelling B. et al (2022). Social Support, Social Isolation, and Burnout: Cross-sectional Study of U.S. Residents Exploring Associations With Individual, Interpersonal, Program, and Work-Related Factors.Acad. Med.971184–1194. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004709

21

Li M. Zhang L. Zhang L. Li X. Xie Y. Qiu Y. et al (2025). The relationships among illness perceptions, dyadic coping and illness management in breast cancer patients and their spouses: A dyadic longitudinal mediation model.Br. J. Health Psychol.30:12771. 10.1111/bjhp.12771

22

Li W. Tang Y. Cui Q. A. (2022). Study on social alienation among patients with schizophrenia in the stabilization phase and its influencing factors.J. Nurs. Sci.3777–79. 10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2022.09.077

23

Li X. Hathaway C. Small B. Tometich D. Gudenkauf L. Hoogland A. et al (2024). Social isolation, depression, and anxiety among young adult cancer survivors: The mediating role of social connectedness.Cancer1304127–4137. 10.1002/cncr.35508

24

Liu S. He H. He M. Zha R. Zen M. (2023). A longitudinal study on factors influencing fear of cancer recurrence in patients undergoing chemotherapy for colorectal cancer.Military Nurs.4054–58. 10.3969/j.issn.2097-1826.2023.03.013

25

Liu Y. Wen L. Zhang X. Wei J. Li Y. Huang Q. (2021). Survey analysis of social isolation among lung cancer survivors and its influencing factors.J. Nurs. Sci.3663–66.

26

Ma C. Zhang L. Yan J. Tang H. (2015). Revision of the Chinese version of the modified illness perception questionnaire and its reliability and validity testing among breast cancer patients.Chinese General Pract.183328–3334. 10.3969/j.issn.1007-9572.2015.27.015

27

Mathieu A. Reignier J. Le Gouge A. Plantefeve G. Mira J. Argaud L. et al (2024). Resilience after severe critical illness: A prospective, multicentre, observational study (RESIREA).Crit. Care28:237. 10.1186/s13054-024-04989-x

28

Mehnert A. Berg P. Henrich G. Herschbach P. (2009). Fear of cancer progression and cancer-related intrusive cognitions in breast cancer survivors.Psychooncology181273–1280. 10.1002/pon.1481

29

Miaskowski C. Paul S. Snowberg K. Abbott M. Borno H. Chang S. et al (2021). Loneliness and symptom burden in oncology patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.Cancer1273246–3253. 10.1002/cncr.33603

30

Pattison E. M. (1978). Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth.Am. J. Psychiatry1351129–1130. 10.1176/ajp.135.9.1129

31

Sharpe L. Menzies R. Richmond B. Todd J. MacCann C. Shaw J. (2022). The development and validation of the Worries about recurrence or progression scale (WARPS).Br. J. Health Psychol.29454–467. 10.1111/bjhp.12707

32

Sharpe L. Michalowski M. Richmond B. Menzies R. Shaw J. (2023). Fear of progression in chronic illnesses other than cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a transdiagnostic construct.Health Psychol. Rev.17301–320. 10.1080/17437199.2022.2039744

33

Siegel R. Kratzer T. Giaquinto A. Sung H. Jemal A. (2025). Cancer statistics, 2025.CA Cancer J. Clin.7510–45. 10.3322/caac.21871

34

Soper D. (2015). A-priori sample size calculator for structural equation models. Available online at: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89(accessed September 7, 2025)

35

Striberger R. Axelsson M. Zarrouk M. Kumlien C. (2020). Illness perceptions in patients with peripheral arterial disease: A systematic review of qualitative studies.Int. J. Nurs. Stud.116103723–103723. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103723

36

Trachtenberg E. Ruzal K. Sandbank E. Bigelman E. Ricon-Becker I. Cole S. et al (2024). Deleterious effects of social isolation on neuroendocrine-immune status, and cancer progression in rats.Brain Behav. Immun.123524–539. 10.1016/j.bbi.2024.10.005

37

Umberson D. Donnelly R. (2023). Social isolation: An unequally distributed health hazard.Annu. Rev. Sociol.49379–399. 10.1146/annurev-soc-031021-012001

38

Wang Y. Kaifeng P. Wenqing L. (2024). Interpreting the 2022 Global cancer statistics report.J. Multidisciplinary Cancer Manag.101–16. 10.12151/JMCM.2024.03-01

39

Wu Q. Ye Z. Li L. Liu P. (2015). Chinese version and psychometric analysis of the cancer patient fear of disease progression simplified scale.Chinese J. Nurs.501515–1519. 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2015.12.021

40

Xu Y. Xie S. Lu Y. Shi X. Zhao Y. Huang H. (2024). A study on the current status and influencing factors of social isolation among patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis.J. Nurs. Sci.3986–90.

41

Zhao X. Li F. Cheng C. Bi M. Li J. Cong J. et al (2024). Social isolation promotes tumor immune evasion via β2-adrenergic receptor.Brain Behav. Immun.123607–618. 10.1016/j.bbi.2024.10.012

42

Zhu B. Wu H. Lv S. Xu Y. (2024). Association between illness perception and social alienation among maintenance hemodialysis patients: The mediating role of fear of progression.PLoS One19:e0301666. 10.1371/journal.pone.0301666

43

Zimet G. Dahlem N. Zimet S. Farley G. (1988). “The multidimensional scale of perceived social support.J. Pers. Assess.5230–41. 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Summary

Keywords

oncology, cancer, social alienation, structural equation modeling, factors

Citation

Hu Y, He Y, Liu X, Liao S, Xie F, Chen O and Zhang J (2025) Factors associated with social alienation in cancer patients: a structural equation modeling approach. Front. Psychol. 16:1721305. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1721305

Received

09 October 2025

Revised

13 November 2025

Accepted

14 November 2025

Published

10 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Simon Dunne, Dublin City University, Ireland

Reviewed by

Ahmed Jaradat, Arabian Gulf University, Bahrain

Yasmin Ibrahim Abdelkader Khider, Mansoura University, Egypt

Budhi Ida Bagus, Sebelas Maret University, Indonesia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Hu, He, Liu, Liao, Xie, Chen and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jie Zhang, zzuzhangjie@163.comOuying Chen, 1577554027@qq.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.