- 1Physics Department, College of Science, Jouf University, Sakaka, Saudi Arabia

- 2Physics Department, Faculty of Science, Qena University, Qena, Egypt

- 3Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Al-Azhar University, Qena, Egypt

- 4National University of Science and Technology Politehnica Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania

- 5Academy of Romanian Scientists, Bucharest, Romania

- 6Physics Department, Faculty of Science, Galala University, Galala City, Egypt

- 7Nanomaterials Lab, Physics Department, Faculty of Science, Qena University, Qena, Egypt

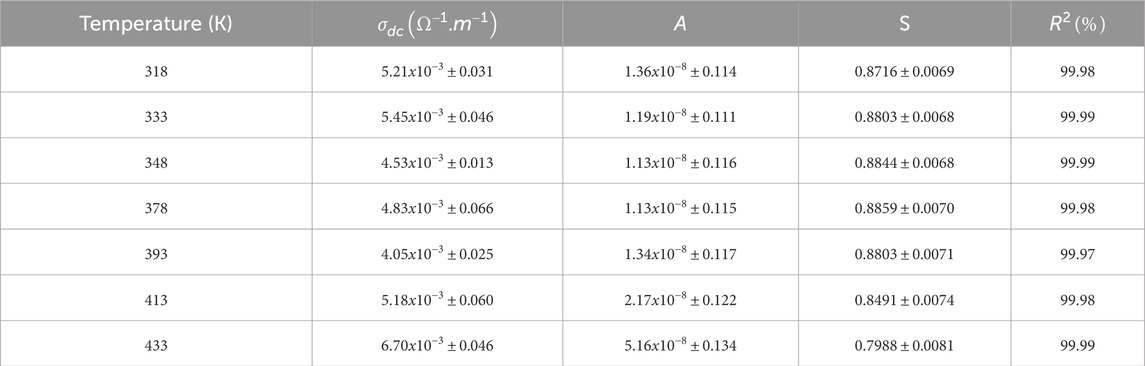

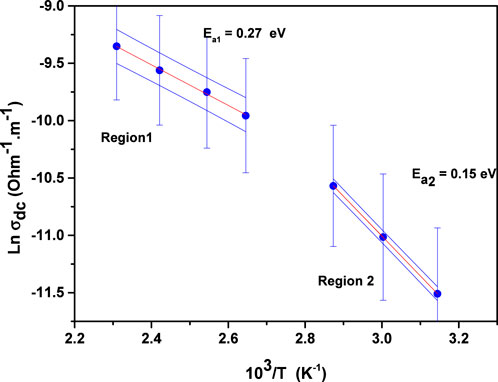

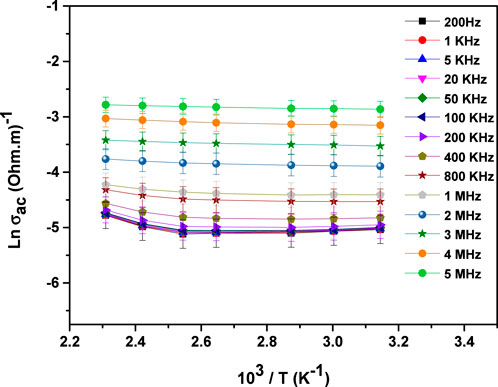

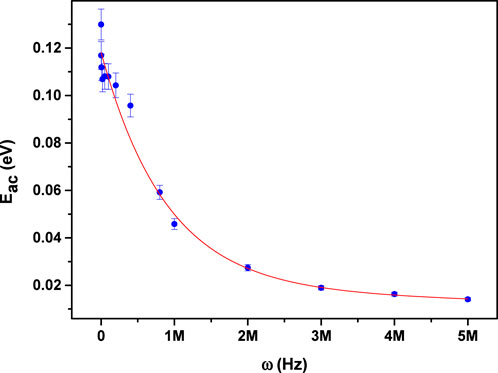

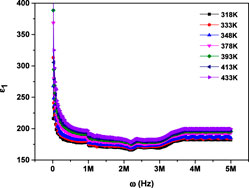

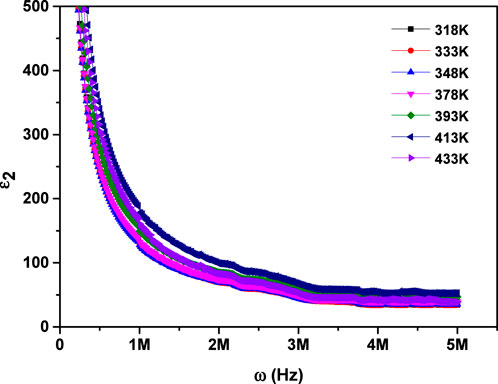

The electrical conductivity and dielectric characteristics were investigated across a frequency range of 200–5 MHz and a temperature range of 318 K to 433K for MgTi2O5 nanoparticles (NPs). The electrical conductivity data displayed two dominant conduction mechanisms: a quantum mechanical tunneling model (QMT) and the correlated barrier hopping model (CBH). The activation energy values derived from the Direct Current (DC) Conductivity were 0.15 and 0.27 eV. In addition, the activation energy values derived from the Alternating Current (AC) Conductivity decreased as frequency increased from 0.13 to 0.014 eV due to the improvement of electronic jumps among localized states. Additionally, dielectric investigation of MgTi2O5 NPs within the frequency range from (200 – 5 MHz) and the temperature range from (318K–433K) revealed that both real (ε1) and imaginary (ε2) components of a dielectric permittivity decrease as the frequency increased and increased as a temperature increased due to thermal motion of electrons, which is related to the polarization mechanism.

1 Introduction

Pseudobrookite MgTi2O5 of the Bbmm space group (1) is a common crystalline phase in TiO2 glass ceramics (2). MgTi2O5 is unique because it can host transitional metal ions in two octahedral cavities while processing refractoriness and high refractive index (2). Furthermore, this material exhibits high thermal stability, cation order-disorder behavior, high permittivity, and dielectric losslessness (3), as well as good mechanical characteristics. The MgTi2O5 compound also has low thermal expansion, good temperature stability, and low cost (4, 5). MgTi2O5 compound is usually used in many applications like a catalyst (6), white pigment (2), photocatalyst (7), pseudobrookit phase stabilizer for the Al2TiO5 compounds, thermistor (8), buffering layers between Silicon substrates and Platinum thin films (9), a red-emitting phosphor (Mg Ti2O5:Eu) (10), sodium-ion batteries, water purification (11) due to its unique properties. Several methods have been used to manufacture MgTi2O5, including, conventional high-temperature (12), sol-gel (13), and citrate gel route, simultaneous hydrolysis (14).

M.A. Ehasn et al. reported the characteristics of MgTi2O5 thin films synthesized by a heterobimetallic single molecular precursor (15), including X-ray diffraction, energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, field emission gun-scanning electron spectroscopy, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Moreover, the optical examination revealed that the MgTi2O5 compound had a direct bandgap of about 3.4 eV. Photoelectrochemical (PEC) measurements of MgTi2O5 electrodes revealed a maximum photocurrent anodic density of approximately 400 μA/cm2 at a voltage of 0.7 V vs. Ag/Ag.Cl/3 M KCl, during simulated sunshine exposure. So, MgTi2O5 has application in optoelectronics. The characteristics of MgTi2O5 prepared by a microwave method, investigated by XRD, TG/DTA, and FTIR, reported by G. Çelik, revealed that the material has an orthorhombic structure and thermal stability (16). T. Selvamani reported the synthesis of MgTi2O5 NPs using a simple hydrothermal post-annealing process (11). The material exhibits a direct allowed transition with an optical band gap of about 3.35 eV. The study reveals that sonophotocatalytic activity degraded crystal violet more effectively than photocatalytic and sonocatalytic activities. So, this material is used in water treatment. H. W. Son (17) reported the investigation of MgTi2O5 ceramics sintered at 1,100 °C–1,200 °C. This study reveals that the material has a high density and flexural strength of 99%. The characterization analysis of MgTi2O5 NPs growth using the co-precipitation technique was reported by S. Elnobi (18), including thermal analysis (TG/DSC), XRD, SEM, TEM, and EDX. Structural characterization revealed that the average crystallite size of the synthesized MgTi2O5 nanoparticles ranges between 27 and 37 nm. Morphological analysis via SEM and TEM imaging confirmed a quasi-spherical particle geometry. The direct band gap value 3.81 + 0.01 eV was estimated from the diffuse reflectance spectra. The DC conductivity was measured across a temperature range of 303–503 K, revealing that thermal activation is the primary mechanism driving conductivity. Besides, MgTi2O5 NPs have a high antibacterial capability (18).

Investigating charge transport processes holds significant value both for advancing technological applications (19) and deepening our fundamental understanding of material behavior. Measuring electrical conductivity (DC and AC) can provide us with information about the mechanisms of charge transport. DC conductivity reflects the movement of free charges in a constant external electric field. Moreover, AC conductivity measurements are particularly useful for probing the characteristics of materials with limited charge mobility.

Despite the extensive research on the structural, optical, and catalytic properties of MgTi2O5, its charge transport behavior—particularly under alternating current (AC) conditions—remains insufficiently understood. Given the compound’s promising dielectric characteristics, thermal stability, and potential for integration into microelectronic and optoelectronic devices (19), a deeper understanding of its frequency- and temperature-dependent electrical response is essential. AC conductivity and impedance spectroscopy offer powerful tools to probe localized charge dynamics, dielectric relaxation, and conduction mechanisms, which are critical for optimizing material performance (18, 20, 21) in real-world applications such as capacitors, sensors, and energy storage systems. This study focuses on exploring how the dielectric properties of MgTi2O5 nanoparticles vary with temperature and frequency, using impedance spectroscopy across a frequency range from 200 Hz to 5 MHz and a temperature range of 318 K–433 K. The conduction mechanism model is defined from the AC conductivity measurements. Moreover, activation energy values and the dielectric permittivity components can be determined from these measurements.

2 Experimental procedure

Previous work illustrated in detail the synthesis of MgTi2O5 NPs using the aqueous co-precipitation method and the characterization of the prepared samples (18).

To prepare MgTi2O5 samples for AC conductivity measurements, we grind the MgTi2O5samples to a fine powder and then press the powder into a pellet with a diameter of 10 mm and a thickness of 2 mm. The two electrodes were formed on a polished pellet surface using silver paste as ohmic contacts. The AC conductivity was obtained using an automated LCR meter program (Hioki model 3,536). Experimental measurements were conducted over a temperature range of 318K–433 K and a frequency range of 200 Hz - 5 MHz.

3 Results and discussion

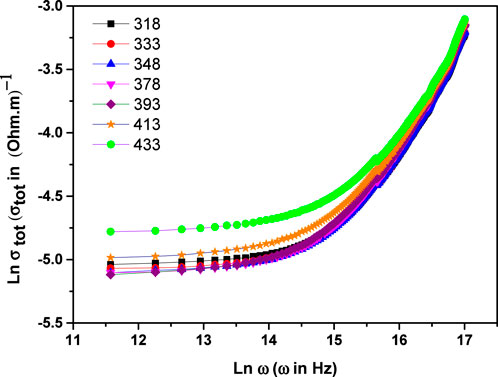

3.1 Investigation of frequency-dependent conductivity

Figure 1 illustrates the frequency-dependent behavior of total conductivity (σtot) across the temperature interval of 318K–433 K, expressed using Jonscher’s law of the universal power (22):

Figure 1. The frequency-dependent electrical conductivity (

3.1.1 Conduction mechanism

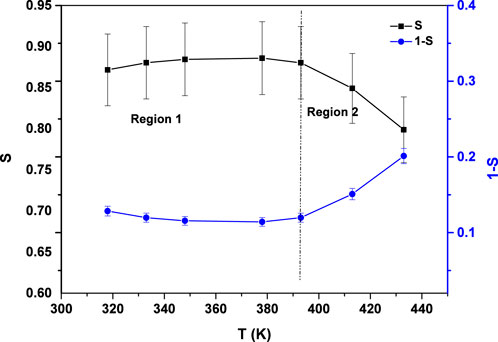

The conduction mechanism can be elucidated by analyzing the temperature and frequency dependence of the frequency exponent (s). To interpret the AC conductivity behavior under varying thermal and frequency conditions, four theoretical models have been proposed. According to the QMT model, the frequency exponent s remains temperature-independent and typically approximates a value near 0.8. According to the CBH model, the frequency exponent s exhibits a temperature-dependent decline, decreasing progressively as temperature increases. In the overlapping large polaron tunneling (OLPT) model, the frequency exponent s initially decreases with rising temperature, reaching a minimum at a specific threshold, beyond which it increases again—demonstrating dependence on both temperature and frequency. Meanwhile, the non-overlapping small polaron tunneling (NSPT) model indicates a temperature-dependent increase in s with thermal elevation.

Using the equation of Jonscher’s universal power law (22):

The frequency exponent s and pre-exponential factor A are evaluated from the slope and intercept, respectively, of the linear fit to the plot of

According to the QMT model, the exponent s remains unaffected by changes in both temperature and frequency (27).

Within the CBH model, electrical conduction occurs through either single polaron or bipolaron hopping mechanisms, which causes disorder in their surrounding medium by displacing atoms away from their equilibrium locations, resulting in structural flaws (28). The CBH model expresses the exponent s as the following formula (29).

Where

As illustrated in Figure 2, plotting (1-s) against absolute temperature T yields a straight line, from which the slope is used to determine the hopping energy

Additionally, the CBH model describes the hopping distance using the following relation (30):

Here, n denotes the number of polarons involved in the hopping process, where n = 1 corresponds to single polaron hopping and n = 2 to a bipolaron hopping. Based on the results, the hopping energy

Based on the CBH model, the Austin-Mott relation can be utilized to determine the AC conductivity

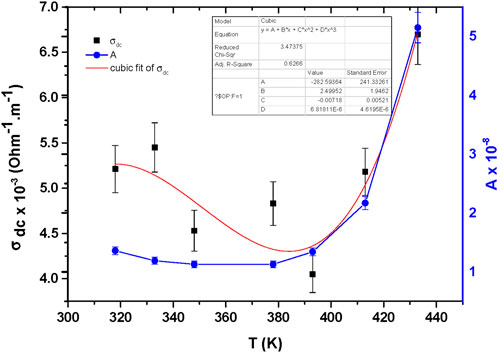

Figure 3 shows a relationship between both pre-exponential factor A, and DC conductivity versus temperature. It is noticed, the pre-exponential factor A increases exponentially significantly with temperature from 1.36 × 10−8 at 318K to 5.16 × 10−8 at 433K. this behavior may be due to enhanced hopping probability and carrier mobility at elevated temperature as well as, a transition from tunneling to thermally hopping reinforcing the CBH mechanism at elevated temperature. While, for DC conductivity σdc variation with temperature, it is clear, an initial decrease of σdc values from 318K to 393K, reach a maximum value 4.05 × 10−3 (Ohm-1.m-1) at 393K and raise sharply again with elevated temperature reaching 6.7 × 10−3 (Ohm-1.m-1) at 433K. This behavior is demonstrating two conduction mechanism exist in MgTi2O5 NPs in temperature range from 318K to 433K.

3.2 Study the temperature-dependent electrical conductivity

The variation of DC conductivity with temperature can be interpreted using the Arrhenius relation (32):

In this relation,

The value of

According to Equation 1, AC conductivity is derived by eliminating the DC contribution from the total conductivity. Its variation with temperature can be examined through the Arrhenius Law (32):

Figure 5 illustrates the temperature-dependent behavior of AC conductivity in MgTi2O5 at various frequencies. The observed increase in conductivity with rising temperature suggests a thermally activated conduction mechanism (36).

Figure 6 illustrates how the AC activation energy

3.3 Analysis of dielectric properties

Examining dielectric permittivity is crucial for gaining insight into the properties of materials. The complex permittivity, denoted as

The symbols

Figures 7, 8 illustrate how the real (

Figure 7. Variation of the real component of dielectric permittivity with frequency for MgTi2O5 NPs at various temperatures.

Figure 8. Dependence of the imaginary component of dielectric permittivity on frequency for MgTi2O5 NPs at various temperatures.

This behavior is explained using many types of polarization, including; electronic, ionic, orientational, and interfacial. (38, 39). At lower frequencies, the dipoles within the material have sufficient time to align completely with the externally applied electric field, resulting in maximum or total polarization. As the frequency rises, the rapid oscillation of the external electric field causes dipoles to struggle with maintaining full alignment. This partial alignment, driven by the swift rotation of dipoles, results in a reduction in orientational polarization. At higher frequencies (around 106 Hz), dipoles can no longer maintain full alignment with the oscillating electric field due to its rapid variation. As a result, their contribution becomes frequency-independent and stabilizes. In this regime, interfacial polarization emerges as the predominant mechanism influencing the dielectric response (26, 31). Moreover, at a given frequency, both ε1 and ε2 exhibit an upward trend with rising temperature. This behavior can be attributed to enhanced thermal agitation of electrons, which plays a key role in the polarization process. At lower temperatures, limited electron mobility restricts their ability to align with the electric field. However, as temperature increases, electrons gain sufficient energy to reorient more effectively, resulting in greater polarization and consequently higher values of ε1 and ε2 (40).

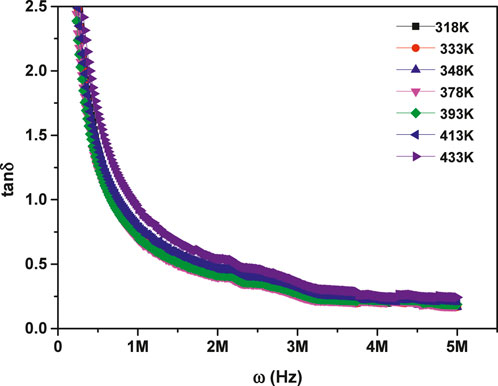

Figure 9 illustrates how the dielectric loss tangent (tan δ) varies with frequency across different temperature conditions. The figure revealed an exponential decrease of

Figure 9. Frequency-dependent behavior of the dielectric loss tangent for MgTi2O5 NPs at various temperatures.

4 Conclusion

The electrical and dielectric behavior of MgTi2O5 nanoparticles was systematically investigated across a temperature range of 318–433 K and a frequency span of 200 Hz to 5 MHz. The AC conductivity exhibited a frequency-dependent trend consistent with the power law relation,

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

AS: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. HW: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review and editing. AI: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. MAE-S: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphy.2025.1728372/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Pauling L. VII. The crystal structure of pseudobrookite. Z für Kristallographie (1930) 73:97–112. doi:10.1524/zkri.1930.73.1.97

2. Matteucci F, Cruciani G, Dondi M, Gasparotto G, Tobaldi DM. Crystal structure, optical properties and colouring performance of karrooite MgTi2O5 ceramic pigments. J Solid State Chem (2007) 180:3196–210. doi:10.1016/j.jssc.2007.08.029

3. Purohit RD, Saha S. Synthesis of magnesium dititanate by citrate gel route and its characterization. Ceram Int (1999) 25:475–7. doi:10.1016/S0272-8842(98)00062-5

4. Suzuki Y, Morimoto M. Porous MgTi2O5/MgTiO3 composites with narrow pore-size distribution: in situ processing and pore structure analysis. J Ceram Soc Jpn (2010) 118:819–22. doi:10.2109/jcersj2.118.819

5. Suzuki Y, Morimoto M. Uniformly porous MgTi2O5 with narrow pore-size distribution: in situ processing, microstructure and thermal expansion behavior. J Ceram Soc Jpn (2010) 118:1212–6. doi:10.2109/jcersj2.118.1212

6. Lopez T, Hernandez-Ventura J, Aguilar DH, Quintana P. Thermal phase stability and catalytic properties of nanostructured TiO2-MgO sol–gel mixed oxides. J Nanosci Nanotech (2008) 8:6608–17. doi:10.1166/jnn.2008.18434

7. Kapoor PN, Uma S, Rodriguez S, Klabunde KJ. Aerogel processing of MTi2O5 (m=Mg, Mn, Fe, Co, Zn, sn) compositions using single source precursors: synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic behavior. J Mol Catal A: Chem (2005) 229:145–50. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2004.11.008

8. Weise EK, Lesk IA. On the electrical conductivity of some alkaline Earth titanates. J Chem Phys (1953) 21:801–6. doi:10.1063/1.1699036

9. Lee C-H, Kim S-I. The characteristics of magnesium titanate thin film as buffer layer by electron beam evaporation. Integ Ferroelectr (2003) 57:1265–70. doi:10.1080/10584580390259821

10. Komimami H, Tanaka M, Hara K, Nakanishi Y, Hatanaka Y. Synthesis and luminescence properties of Mg-Ti-O: Eu red-emitting phosphors. Phys Status Solidi C (2006) 3:2758–61. doi:10.1002/pssc.200669655

11. Selvamani T, Anandan S, Asiri AM, Maruthamuthu P, Ashokkumar M. Preparation of MgTi2O5 nanoparticles for sonophotocatalytic degradation of triphenylmethane dyes. Ultrason Sonochem (2021) 75:105585. doi:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105585

12. Purohit RD, Saha S. Synthesis of magnesium dititanate by citrate gel route and its characterisation. Ceram Int (1999) 25:475–7. doi:10.1016/s0272-8842(98)00062-5

13. López T, Hernández J, Gómez R, Bokhimi X, Boldú JL, Muñoz E, et al. Synthesis and characterization of TiO2−MgO mixed oxides prepared by the sol−Gel method. Langmuir (1999) 15:5689–93. doi:10.3390/ma12050698

14. Yamaguchi O, Yamamoto S. Kinetics of the formation of alkoxy-derived MgO0.2TiO2 and MgO.TiO2. Ceram Int (1981) 7:73–4. doi:10.1016/0272-8842(81)90018-3

15. Ali Ehsan M, Naeem R, McKee V, Saeed Hakeem A, Mazhar M. MgTi2O5 thin films from single molecular precursor for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Solar Energy Mater & Solar Cells (2017) 161:328–37. doi:10.1016/j.solmat.2016.12.015

16. Çelik G, Kurtulus F. Fast microwave synthesis and characterization of MgTi2O5. Int J Mater Res (2015) 106:311–3. doi:10.3139/146.111175

17. Son H-W, Maki RSS, Kim B-N, Suzuki Y. High-strength pseudobrookite-type MgTi2O5 by spark plasma sintering. J Ceram Soc Jpn (2016) 124:838–40. doi:10.2109/jcersj2.16058

18. Elnobi S, Abuelwafa AA, Abd El-sadek MS, Wasly HS. Facile synthesis and physical properties of magnesium dititanate nanoparticles for antibacterial applications. Indian J Phys (2024) 7:2417–27. doi:10.1007/s12648-023-03028-9

19. Siva Jahnavi V, Kumar Tripathy S, Ramalingeswara AVN. Rao 2019 structural, optical, magnetic and dielectric studies of SnO2 nano particles in real time applications. Physica B: Condensed Matter (2019) 565:61–72. doi:10.1016/j.physb.2019.04.020

20. Suzuki Y, Shinoda Y. Magnesium dititanate (MgTi2O5) with pseudobrookite structure: a review. Sci Technol Adv Mater (2011) 12:034301. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/12/3/034301

21. Son HW, Guo Q, Suzuki Y, Kim BN, Mori T. Thermoelectric properties of MgTi2O5/TiN conductive composites prepared via reactive spark plasma sintering for high-temperature functional applications. Scripta Materialia (2020) 178:44–50. doi:10.1016/j.scriptamat.2019.11.008

22. Dhahri A, Dhahri E, Hlil EK. Electrical conductivity and dielectric behaviour of nanocrystalline La0.6Gd0.1Sr0.3Mn0.75Si0.25O3. RSC Adv (2018) 8:9103–11. doi:10.1039/c8ra00037a

23. Aman S, Ahmad N, Almutairi BS, Tahir MB, Ali HE. Study of gadolinium substituted barium-based spinel ferrites for microwave applications. J Electron Mater (2023) 52:4149–61. doi:10.1007/s11664-023-10396-9

24. Ben Yahya S, Barillé R, Louati B. Synthesis, optical and ionic conductivity studies of a lithium cobalt germanate compound. RSC Adv (2022) 12:6602–14. doi:10.1039/d2ra00721e

25. Hossain MS, Islam R, Khan KA. Electrical conduction mechanisms of undoped and vanadium doped ZnTe thin films. Chalcogenide Lett (2008) 5:1–9.

26. Saad Ebied M, Abd El-sadek MS, Salwa AS. Structural and dielectric properties of green synthesized SnO2 nanoparticles. Phys Scr (2025) 100:015989. doi:10.1088/1402-4896/ad9ee8

27. Kumar A, Singh S. Electrical properties and conduction mechanisms of Ba0.75Sr0.25Ti1-xZrxO3 ceramics synthesized by sol-gel route. Ceramics Int (2024) 50:29476–85. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.05.242

28. Elliott SR. A theory of AC conduction in chalcogenide glasses. Phil Mag (1977) 36:1291–304. doi:10.1080/14786437708238517

29. Meena R, Dhaka RS. Dielectric properties and impedance spectroscopy of NASICON type Na3Zr2Si2PO12. Ceramics Int (2022) 23:35150–9. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.08.111

30. Saleh AM, Hraibat S, Kitaneh RL, Abu-Samreh M, Musameh S. Dielectric response and electric properties of organic semiconducting phthalocyanine thin films. J Semiconductors (2012) 8:082002. doi:10.1088/1674-4926/33/8/082002

31. Hamood R, Abd El-sadek MS, Gadalla A. Facile synthesis, structural, electrical and dielectric properties of CdSe/CdS core-shell quantum dots. Vacuum (2018) 157:291–8. doi:10.1016/j.vacuum.2018.08.050

32. Moustafa MG, Saad HMH, Ammar MH. Insight on the weak hopping conduction produced by titanium ions in the lead borate glassy system. Mater Res Bull (2021) 140:111323. doi:10.1016/j.materresbull.2021.111323

33. Kang SD, Dylla M, Snyder GJ. Thermopower-conductivity relation for distinguishing transport mechanisms: polaron hopping in CeO2 and band conduction in SrTiO3. Phys Rev B (2018) 97:235201. doi:10.1103/physrevb.97.235201

34. Triberis GP. A conductivity study on V2O5 layers deposited from gels. J non-crystalline Sol (1988) 104:135–8. doi:10.1016/0022-3093(88)90192-5

35. Takahama R, Arizono M, Indo D, Yoshinaga T, Terakra C, Takeshita N, et al. Magnetic and transport properties of the pseudobrookite Al1−xTi2+xO5 single crystals. JPS Conf Proc (2023) 38:011114. doi:10.7566/JPSCP.38.011114

36. Yakuphanoglu F, Aydogdu Y, Schatzschneider U, Rentschler E. DC and AC conductivity and dielectric properties of the metal-radical compound: aqua[bis(2-dimethylaminomethyl-4-NIT-phenolato)] copper(II). Solid State Commun (2003) 128:63–7. doi:10.1016/s0038-1098(03)00651-3

37. El-Nahass MM, Atta AA, El-Zaidia EFM, Farag AAM, Ammar AH. Electrical conductivity and dielectric measurements of Co MTPP. Mater Chem Phys (2014) 143:490–4. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2013.08.038

38. Darwish AAA, El-Nahass MM, Bekheet AE. AC electrical conductivity and dielectric studies on evaporated nanostructured InSe thin films. J Alloys Compd (2014) 586:142–7. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.10.054

39. Sharma A, Mehta N. Analysis of dielectric relaxation in glassy Se and Se98M2 (M = Ag, Cd and Sn) alloys. Eur Phys J Appl Phys (2012) 59:10101–7. doi:10.1051/epjap/2012120184

Keywords: MgTi2O5 NPs, QMT model, CBH model, AC conductivity, dielectric properties

Citation: Salwa AS, Wasly HS, Ioanid A and Abd El-Sadek MS (2025) Quantum tunneling and barrier hopping in MgTi2O5 nanoparticles: a study of AC/DC conductivity and dielectric response. Front. Phys. 13:1728372. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2025.1728372

Received: 19 October 2025; Accepted: 07 November 2025;

Published: 26 November 2025.

Edited by:

Shiyun Xiong, Guangdong University of Technology, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Salwa, Wasly, Ioanid and Abd El-Sadek. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: A. S. Salwa, c3NhYWxpQGp1LmVkdS5zYQ==; Alexandra Ioanid, YWxleGFuZHJhLmlvYW5pZEB1cGIucm8=

A. S. Salwa

A. S. Salwa H. S. Wasly3

H. S. Wasly3 Alexandra Ioanid

Alexandra Ioanid