- 1Department of Social Work and Psychology, Gävle University College, Gävle, Sweden

- 2Department of Occupational and Public Health Sciences, Gävle University College, Gävle, Sweden

The aim of this study was to investigate the role of personal and collective work identity (including emotion and cognition components), in predicting work motivation (operationalized as work self-determined motivation) and organizational justice (operationalized as organizational pay justice). Digitized questionnaires were distributed by e-mail to 2905 members, teachers, of a Swedish trade union. A total of 768 individuals answered the questionnaire and by that participated in this study. Personal- compared to collective work identity was shown to positively associate with self-determined motivation accounted for by the emotion component of personal work identity. Collective compared to personal work identity was reported to positively associate with organizational pay justice accounted for by the cognition component of collective work identity. All this suggests that both work-related motivation and organizational justice might be, to some extent, accounted for by the psychological mechanisms of work identity and that, as predicted, different types of work identity, play different significant roles in predicting motivation and justice at work. More precisely, the emotion component of work identity was more pronounced in personal work-bonding relationships, and the cognitive component, of work identity in contrast, was more pronounced in collective work-bonding relationships.

Introduction

We identify us with our work. A phenomenon labeled work identity, involving emotion and cognition processes, accounts for this type of bonding (Knez, 2016). Work identity can be divided into personal and collective identity, in general terms, involving two different foci of identification (van Knippenberg and van Schie, 2000; Millward and Haslam, 2013) that differently associate with a wide range of work- and organizational behaviors, norms and attitudes (Riketta, 2005; Riketta and Van Dick, 2005; Lee et al., 2015).

Another important factor that guides our work-related behavior and engagement (e.g., Björklund, 2001; Latham and Pinder, 2005) is work motivation, defined as “the energetic forces that initiate work-related behavior and determine its form, direction intensity and duration” (Pinder, 2008, p. 11). A further construct of great magnitude within the context of occupational work is organizational justice. It involves processes of perceived fairness and different types of interactions within the organization (Greenberg and Colquitt, 2005). Like motivation, organizational justice has been shown to associate with a wide range of crucial employee and organizational outcomes (Colquitt, 2001; Nowakowski and Conlon, 2005; Colquitt et al., 2013).

Accordingly, this paper is about work-related identity, motivation, and justice; more precisely, about the relationships between these three constructs central to different employee and organizational outcomes. We first review the research on work identity. We then review research on work motivation and organizational justice. Finally, we formulate the objectives and the associated hypotheses of the present study.

Work Identity

According to, for example, McConnell (2011) the self is a collection of multiple, context-dependent selves resulting in multiple identities. We furthermore categorize and define ourselves in terms of individual attributes, involving a personal self/identity (Hogg and Terry, 2000; Klein, 2014; Knez, 2016), and social attributes, involving a collective self/identity (Jackson et al., 2006; Knez, 2016). Given this, we can say that work identity involves two levels of abstraction as two different knowledge structures (Kihlstrom et al., 2003), namely, personal and collective work identity (Riketta, 2005; Pate et al., 2009; Miscenko and Day, 2016). In line with the self-categorization theory (e.g., Turner et al., 1987) personal work identity has the personal career or occupation as its focus of identification while collective work identity has the organization as a whole as its focus of identification (van Dick and Wagner, 2002; Riketta and Van Dick, 2005).

Thus, the foci of identification refer to variations of the identity concept “that are defined at different levels of abstraction in applied organizational context” (Millward and Haslam, 2013, p. 51). Personal and collective work identities are relatively independent of each other, meaning that having a strong identity at one level does not rule out a similarly strong identity on another level (Brewer and Gardner, 1996; Pate et al., 2009). It is furthermore suggested that these constructs might differ along the dimension of inclusiveness (Sluss and Ashforth, 2007; Miscenko and Day, 2016), resulting in different self-related definitions and interpretations (Sedikides et al., 2011; Knez, 2016). In particular, personal work identity involves classifications of “My profession/work” and, for example, “I/Me a teacher of psychology.” It articulates the psychological need to distinguish oneself from others (Brewer and Gardner, 1996) “in order to preserve the personal self, the personal story and its memories” (Knez, 2016, p. 3).Therefore, it is associated with individual self-related cognitions, interests, values, attitudes, motivations and behaviors (Ybarra and Trafimow, 1998; Johnson et al., 2006). By consequence, the stronger the personal work identity the stronger personal goals, preferences and needs will be (Brewer and Gardner, 1996; Ybarra and Trafimow, 1998; Ellemers et al., 2004).

In line with our psychological prerequisite to belong to a social group (Brewer and Gardner, 1996), collective work identity involves the We-descriptions “in order to be part of the collective self, the collective story and its memories” (Knez, 2016, p. 3). Accordingly, this phenomenon involves cognitions, interests, values, norms, motivations and behaviors related to the identity of a group or an organization (Ybarra and Trafimow, 1998; Johnson et al., 2006). According to social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1979, 1986; see Hogg, 2012 for a review), the knowledge of belonging to a certain group includes furthermore a depersonalization of the individual self and an emotional attachment to the group/organization. Hence, the more “collectivized” an individual is the more s/he will demonstrate loyalty, acceptance, adherence to norms, values, beliefs and decisions communicated by the group/organization (Hogg and Terry, 2000; Ellemers et al., 2004; Johnson and Jackson, 2009). This suggests that normative and motivational mechanisms of the We will be generated by the depersonalized individual (Brewer and Gardner, 1996; Ybarra and Trafimow, 1998; Ellemers et al., 2004).

Along the lines of Knez (2014) and Knez (2016) proposed a conceptual model of the work-related self, a personal work identity including emotion and cognition categorizations of the work, based on the autobiographical memory research (e.g., Kihlstrom and Klein, 1994; Wilson and Ross, 2003; Conway and Holmes, 2004; Conway et al., 2004; Klein et al., 2004; Knez, 2017; Knez and Nordhall, 2017; Knez et al., 2017). The emotion component encompasses the process of work-related attachment/belongingness/closeness, and the cognition component involves the processes of work-related coherence, correspondence, mental time, reflection and agency. This theoretical frame of reference furthermore implies that that the work identity (encompassing above mentioned cognitive and emotional processes) is a higher order cognitive construct (Law et al., 1998; Stajkovic, 2006), a knowledge structure resulting in a personal, autobiographical work-related experience.

Knez (2016) predicted that the emotional component will precede the cognitive one in establishing personal work identity (see Knez and Eliasson, 2017 for similar argument). Finally, Knez (2016) model is general in its formulations, meaning that the psychological mechanisms accounting for the person-work bonding can be applied in both personal and collective accounts. However, in contrast to personal identity, organizational identity is more of a cognitive structure (Harquail and King, 2003) conceptualized as “a product of the dialectic relationship between collective, shared cognition on one hand and socially structured individual cognitions on the other” (Corley et al., 2006, p. 88). This suggests that the cognitive component in organizational identity, in terms of incorporation, identification and assimilation, might precede the emotional component, in terms of affective commitment, esteem and pride (Mael and Ashforth, 1992; van Knippenberg and Sleebos, 2006).

In sum, the concept of work identity used in this study involves two theoretical perspectives, levels of abstraction (in general terms foci of identification, e.g., Reichers, 1985; van Knippenberg and van Schie, 2000; Millward and Haslam, 2013): (1) personal work identity originated from a cognitive, autobiographical memory perspective (e.g., Knez, 2016); and (2) collective work identity emanated from a social identity perspective (e.g., Ashforth and Mael, 1989). As a result, we broaden the multiple focus of identification concept as a part of everyday organizational life to include personal, autobiographical work-related experiences (personal work identity). By that we suggest that personal career/occupation can be treated at both the autobiographical memory level (individual) and the organizational/workgroup level (social). This means that career/occupation at the former level “can be conceptualized as one of the life goals that we strive for and find meaning in Gini (1998), analogous with Sisyphus rolling the boulder up the hill (Camus, 1942)” (Knez, 2016, p. 2).

Work Motivation

Research on work motivation has previously shown associations between work motivation and well-being (Baard et al., 2004; Steers et al., 2004; Gagné and Deci, 2005), turnover intentions (Houkes et al., 2003), organizational commitment (Tremblay et al., 2009), and work performance and productivity (Steers et al., 2004; Rich et al., 2010), as well as to organizational and interpersonal work environment (Latham and Pinder, 2005) such as leadership (Castanheira et al., 2016), social support (Castanheira, 2016), and satisfaction (Gillet et al., 2016). Also, individual differences in perceived control, self-esteem, ego-development, defensive functioning and basic need satisfaction, have been shown to associate with work motivation (Gagné and Deci, 2005; Latham and Pinder, 2005).

One of the major theories in motivation, Self-Determination Theory (Deci and Ryan, 2000, 2002; Ryan and Deci, 2000a, 2002), has been broadly applied in the occupational work-context. According to this account (Gagné and Deci, 2005) occupational work per se has the potential to promote different psychological needs and thereby influence personal self-determined, i.e., intrinsic, motivation (Ryan and Deci, 2000b; Deci and Ryan, 2010; van den Broeck et al., 2016). Furthermore, Self-Determination Theory highlights individual rather than group-based needs and motivation and by that has the individual as its focus (Gagné and Deci, 2005; Riketta and Van Dick, 2005; Ryan and Deci, 2012; Bjerregaard et al., 2015).

Three basic psychological needs are assumed to form the foundation on which self-determined work motivation relies (Deci and Ryan, 2000; van den Broeck et al., 2016): (1) Competence, involving effectiveness, confidence and capacities in one's daily work and in the interplay with colleagues, managers, customers and clients (Deci and Ryan, 2000, 2008; Elliot et al., 2002; Gagné and Deci, 2005); (2) Relatedness, refers to feelings connected to others (colleagues, managers, customers, clients etc.) and being cared for by, and caring for, others (Deci and Ryan, 2000, 2008; Gagné and Deci, 2005); and (3) Autonomy, involves experiences of own behaviors and actions as expressions of the self (Deci and Ryan, 2000, 2008; Gagné and Deci, 2005).

Finally, previous findings indicate that the more one identifies with occupational work the stronger self-determined work motivation will be, and the stronger one perceives the views of one's organization to be the less one's self-determined motivation is presumed to be (Deci and Ryan, 2000; van den Broeck et al., 2016). Given all this, in this study the concept of work motivation was operationalized as the work self-determined motivation.

Organizational Justice

Organizational justice has been shown to associate with both individual and organizational outcomes (Greenberg, 2011; Colquitt et al., 2013), such as work performance (Wang et al., 2015), job satisfaction (Greenberg, 2011), organizational commitment (López-Cabarcos et al., 2015), counterproductive behavior Cremer (2006), turnover intention (Aryee et al., 2002), organizational citizenship behavior (Blader and Tyler, 2009), health related factors like sick leave, stress related problems, cardiovascular problems, burnout and emotional exhaustion (Greenberg, 2010; Ndjaboué et al., 2012; Robbins et al., 2012; Piccoli and De Witte, 2015), and anxiety and depression (Spell and Arnold, 2007).

Several predictors of organizational justice have also been indicated, such as trust in the supervisor or organization (Aryee et al., 2002), perceived equity and equality within the organization (Colquitt et al., 2005), needs (see Greenberg and Cohen, 1982), job security, complexity and status (Ambrose and Arnaud, 2005) moral and ethical standards (Folger et al., 2005), perceived organizational support (Bies, 2005), and expectations (Colquitt et al., 2005).

This construct has furthermore been shown to comprise four independent dimensions (Colquitt, 2001; Ambrose and Arnaud, 2005; Colquitt and Shaw, 2005; Greenberg and Colquitt, 2005; Ambrose and Schminke, 2009; Nicklin et al., 2014):

Procedural justice involves perceptions of fairness related to organizational procedures (Colquitt et al., 2005; Greenberg, 2011). One central issue is the opportunity to “voice,” i.e. to express one's opinions and concerns (Thibaut and Walker, 1975). Also, consistency, correctness, lack of bias, and accuracy foster this dimension (Leventhal, 1980).

Distributive justice involves perceptions of fairness related to the distribution of outcomes such as money, rewards, and time (Colquitt et al., 2005; Greenberg, 2011). It is fostered when outcomes are consistent with respect to equity and equality (Adams, 1965; Leventhal, 1980) and when personal effort-outcome ratios match effort-outcome ratios of significant others (Adams, 1965).

Interpersonal justice involves perceptions of the supervisor's conduct, in terms of being courteous. Even though decisions might entail negative consequences for the recipient, they are still perceived as fair if the individual recognizes him/herself to be respectfully treated by the supervisor (Greenberg, 1990, 1993).

Informative justice involves the amount, quality and timing of the information received by the employee (Greenberg, 1993). In addition, there should be regular opportunities to receive relevant and adequate explanations of, and arguments for (Bobocel and Zdaniuk, 2005), for example, payment decisions (Andersson-Stråberg et al., 2007).

Previous research strongly suggests including all four justice dimensions in studies related to organizational context issues (Bies, 2005). However, since this phenomenon emanates from the organizational work-environment and thus has the organization, i.e., the collective as its focus (Riketta and Van Dick, 2005), it is reasonable to assume that organizational related issues like organization-related identity, loyalty, shared values and preferences, may be more critical for the organizational justice (Cremer, 2006; Blader and Tyler, 2009). Finally, in this study the concept of organizational justice was operationalized as organizational pay justice, because it originates from an organizational framework (Greenberg and Colquitt, 2005; Andersson-Stråberg et al., 2007) and by that might link with collective work identity (see Present Study below for this line of reasoning).

Present Study

In line with self-categorization theory (e.g., Turner et al., 1987) and the general notion of foci of identification and its associated effects, the relationship between work identity and other work-related constructs might be stronger when foci of categorization between the constructs match; thus, when both the type of identity (predictor) and the outcome (criterion variable) are conceptually related (van Dick and Wagner, 2002; Riketta and Van Dick, 2005; Olkkonen and Lipponen, 2006).

Within the frameworks of social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1979, 1986; see Hogg, 2012 for a review), the two predominating foci of identification (and outcomes) have been work-group (relational level) and organization (collective level), both involving a social focus of identification. This means that the personal focus of identification has to a large extent been neglected in previous research (van Dick and Wagner, 2002; Riketta, 2005; Riketta and Van Dick, 2005). Given this, the aim of the present study was to explicitly test the general notion of foci of identification and its associated effects within and beyond the social focus of identification. This was done by investigating both the personal and the collective focus of identification in relation to work-related motivation and justice.

By consequence and given that personal and collective work identity might tap psychological processes at different levels of abstraction (Haslam et al., 2000; Sluss and Ashforth, 2007), we hypothesized that these constructs will associate differently with work-related motivation and justice.

It has, for example, been reported that collective work identity is not associated with individual internal motivation (van Knippenberg and van Schie, 2000), and that a positive association between collective work identity and organizational-related motivation and behaviors is stronger in a collectivistic vs. an individualistic organizational culture (Lee et al., 2015). Also, the more one identifies with one's occupational work tasks (personal/individual identification) the stronger one's basic need satisfaction is, and the stronger one identifies with one's organization (collective identification), the weaker one's self-determined motivation is (van den Broeck et al., 2016).

The two different structures of work identity have been, furthermore, related to different motivational (van Knippenberg and van Schie, 2000; Ellemers et al., 2004; Johnson et al., 2010; He et al., 2014) and attitudinal (Ybarra and Trafimow, 1998) outcomes. Previous studies have, however, largely addressed the motivational issues on behalf of the organizational collective as opposed to the personal motivation to perform well. Also, the focus of identification has to a large extent been framed in terms of social identity; thus, relational and/or collective work identity (van Knippenberg, 2000; van Dick and Wagner, 2002; Bjerregaard et al., 2015).

Most previous findings on the relationships between work identity and organizational justice have, in line with the group-engagement model (Tyler and Blader, 2003; Blader and Tyler, 2009), focused on justice as a decisive predictor of different levels of work identity. This was done to clarify the role of identity-based information incorporated in organizational justice (Lipponen et al., 2011), as well as the mediating role of work identity in relation to the effects of organizational justice on different outcomes (Olkkonen and Lipponen, 2006; Cho and Treadway, 2011; He et al., 2014). Finally, interaction effects of social identity and organizational justice dimensions on different work-related outcomes have additionally been investigated (Cremer, 2006; Lipponen et al., 2011; Smith, 2012).

Regarding the relationship between work identity and organizational justice, it is suggested that the self-constitutes one of the predicting foundations for self-reported justice (Skitka, 2003). Several findings have indicated that this association primarily concerns collective work identity (Olkkonen and Lipponen, 2006; Blader and Tyler, 2009; Cho and Treadway, 2011; Ehrhardt et al., 2012; He et al., 2014).

Despite the previous research on work-related motivation and justice no previous research has, as far as we know, investigated the role of personal and collective work identity in predicting these constructs. Accordingly, and in line with the general notion of foci of identification and its associated effects (van Dick and Wagner, 2002; Riketta and Van Dick, 2005; Olkkonen and Lipponen, 2006) the aim of the present study was to investigate the relationships between personal and collective work identity, as predictors, and work-related motivation and justice as criterion variables. This involves both matching variables and two levels of explanation; that is, a link between: (1) Personal work identity and work-related Self-determined motivation (personal level of explanation); and (2) Collective work identity and Organizational pay justice (collective level of explanation).

Hypotheses

Given the above, we predicted:

Hypothesis 1. In accordance with Deci and Ryan (2000) and van den Broeck et al. (2016), the more one identifies with occupational work the stronger self-determined motivation one will be subjected to. Accordingly, the association might be stronger when identity and motivation conceptually match (Riketta and Van Dick, 2005; Olkkonen and Lipponen, 2006). Hence, we predicted a stronger positive association of personal work identity  work self-determined motivation than collective work identity

work self-determined motivation than collective work identity  work self-determined motivation.

work self-determined motivation.

Hypothesis 2. In line with Knez (2016) and Knez and Eliasson (2017), we predicted that emotion compared to cognition component of personal work identity would show a stronger positive association with work self-determined motivation.

Hypothesis 3. Given that organizational pay justice (Greenberg and Colquitt, 2005; Andersson-Stråberg et al., 2007) emanates from an organizational framework, and thus has the same level of explanation as collective work identity, we hypothesized a stronger positive association of collective work identity  organizational pay justice than personal work identity

organizational pay justice than personal work identity  organizational pay justice. This suggests that organizational compared to individual work-related issues might be more central to organizational justice (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Cremer, 2006; Blader and Tyler, 2009).

organizational pay justice. This suggests that organizational compared to individual work-related issues might be more central to organizational justice (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Cremer, 2006; Blader and Tyler, 2009).

Hypothesis 4. In line with some previous research suggesting organizational identity to be more of a cognitive structure of shared collective and individual cognitions (Harquail and King, 2003; Haslam and Ellemers, 2005; Corley et al., 2006), we predicted that cognition compared to emotion component of collective work identity would show a stronger positive association with organizational pay justice.

Methods

Participants

Digitized questionnaires were distributed by e-mail to 2905 members of the Swedish trade union “The National Union of Teachers” (in Swedish “Lärarnas Riksförbund”) working in the south and middle part of Sweden, during April and May 2016. A total of 768 questionnaires were returned, with a response rate of 26%. Ninety-nine percent of the participants had an educational function, that is, they worked as teachers or similar. Also, the participants worked within the municipal sector (92.1%), had university studies as their highest level of education (68%), were in permanent employment (95.2%), had full-time jobs (80.5%) and were female (75.5%). Mean age was 46.3 (SD = 10.07, range 24–67) and mean employment time within the organization was 14 years (SD = 10.2).

Measures

Work Motivation

Work motivation was measured by “Work Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation Scale,” WEIMS (Tremblay et al., 2009), applied in several previous studies (Peklar and Boštjančič, 2012; Stoeber et al., 2013; Jayaweera, 2015; Saltson and Nsiah, 2015). WEIMS is an 18-item measure theoretical grounded in self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Ryan and Deci, 2000a; Gagné and Deci, 2005). Participants responded to the WEIMS-items regarding the question “Why do you do your work?” on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“Does not correspond at all”) to 5 (“Corresponds exactly”). WEIMS contains six subscales measuring: (a) Intrinsic motivation (e.g., “Because I derive much pleasure from learning new things”); (b) Integrated regulation (e.g. “Because it is part of the way in which I have chosen to live my life”); (c) Identified regulation (e.g., “Because I chose this type of work to attain my career goals”); (d) Introjected regulation (e.g., “Because I want to be a “winner” in life”); (e) External regulation (e.g., “For the income it provides me”); (f) Amotivation (e.g., “I don't know, too much is expected of us”). In order to obtain a measure of the participants' overall work motivation, the subscales a-f were aggregated into an overall “Work self-determined index,” W-SDI (Tremblay et al., 2009). The response scale has a range of ±24. The positive part of the scale indicates self-determined work motivation, while the negative one indicates non-self-determined work motivation (Vallerand and Ratelle, 2002; Tremblay et al., 2009). Good psychometric properties have been reported for this measure, with a Cronbach alpha (α) of 0.84 (Tremblay et al., 2009). In the current study the Cronbach alpha (α) of work self-determined motivation was 0.74, indicating acceptable internal consistency (DeVellis, 2003).

Organizational Pay Justice

In order to measure organizational pay justice as a construct derived from the more general concept of organizational justice, we used Colquitt's (2001) 20-item measure (Colquitt and Shaw, 2005; see also Greenberg, 2011), measuring Procedural pay justice (e.g., “You have been able to express your views and feelings during the pay procedures”); Distributive pay justice (e.g., “Your salary reflects the effort you have put into your work”); Interpersonal pay justice (e.g., “The pay setting manager has treated you in a polite manner”); Informative pay justice (e.g., “The pay setting manager has explained the procedures thoroughly”). Participants responded to the statements on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“To a very small extent”) to 5 (“To a very large extent”). Previous studies have shown good fit for the four-factor model of this measure with good psychometric properties (Colquitt, 2001; Andersson-Stråberg et al., 2007). In the present study, the four dimensions of organizational pay justice showed the following Cronbach alpha values (α): procedural pay justice 0.91; distributive pay justice 0.95; interpersonal pay justice 0.93; and informative pay justice 0.94. This indicates very good internal consistency for organizational pay justice dimensions (DeVellis, 2003).

Work Identity

In order to measure personal work identity we used a measure suggested by Knez (2014, 2016) and Knez and Eliasson (2017). It includes 10 statements measuring emotion and cognition components of personal work identity: Emotion (“I am keenly familiar with my work”; “I miss it when I'm not there.”; “I have strong ties to my work.”; “I am proud of my work.”; “It is a part of me.”); Cognition (“I have had a personal contact with my work over a long period.”; “There is a link between my work and my current life.”; “I can travel back and forth in time mentally to my work when I think about it.”; “I can reflect on the memories of my work”; “Thoughts about my work are part of me.”). Participants were asked to respond to the statements on a 5-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). In the present study, the Cronbach alpha (α) values were 0.86 for personal work identity and 0.75 for emotion and 0.84 for cognition component respectively, indicating acceptable-good internal consistency (DeVellis, 2003).

In addition, we examined the construct validity of the personal work identity construct with a confirmatory factor analysis, including a second-order factor representing a general personal work identity construct, with cognitive and emotional components as first-order factors. According to Byrne (2016) the model showed acceptable data fit of Chi2 = 188.57, df = 28 (p = 0.000), CFI = 0.95 and RMSEA = 0.08.

Collective work identity was measured by the “Identification with a Psychological Group Scale” (Mael and Ashforth, 1992; Mael and Tetrick, 1992; Riketta, 2005), theoretically grounded in Social Identity Theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1979, 1986) and the Self-Categorization Theory (Hogg and Terry, 2000). This measure includes six statements with a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Based on the conceptual model of Knez (2014, 2016) that distinguishes between an emotion and a cognition component of the work-related personal and collective self (Jackson et al., 2006; Knez, 2016), the items of the “Identification with a Psychological Group Scale” (Mael and Ashforth, 1992), was, besides being indexed, categorized into an Emotion component (item 1 = “When someone criticizes my organization, it feels like a personal insult”; 5 = “When someone praises the organization, it feels like a personal compliment”; 6 = “If a story in the media criticized the organization, I would feel embarrassed”), and a Cognition component (item 2 = “I am very interested in what others think about the organization”; 3 = “When I talk about the organization, I usually say ‘we’ rather than ‘they”’; 4 = “This organizations' successes are my successes”). This was done in line with Mael and Ashforth's (1992) suggestions.

The following Cronbach alphas (α) were reported in the present study: 0.87 for collective work identity, and 0.78 for emotional and 0.77 for cognitive component, indicating good internal consistency (DeVellis, 2003). We also, as above, examined the construct validity of the collective work identity construct, including a second-order factor representing a general collective work identity, with cognitive and emotional components as first-order factors. This model showed acceptable data fit of Chi2 = 64.09, df = 7 (p = 0.000), CFI = 0.97 and RMSEA = 0.10 (Byrne, 2016).

Procedure

Chairpersons of 11 municipal associations of the Swedish trade union The National Union of Teachers were contacted and informed of the purpose of the present study. They were asked to invite their union members to participate in the present study, of which they approved. Due to Swedish juridical restrictions that do not permit a chairperson of a union to distribute individual e-mail addresses of the members, a web-link to the questionnaire was distributed to the members by the chairpersons. The questionnaires were accompanied by a covering letter that described the purpose of the study and informed the participants that completion of the questionnaire was taken as an indication of their consent to participate in the present study, and that this was voluntary and that confidentiality and anonymity was assured. After completion of the questionnaire the participants were asked to fill in their name and address if they wanted to receive a cinema ticket as compensation for their participation. They were informed that nobody but the researchers of the present study would have access to their names and addresses.

Finally, an ethical application was reviewed and approved by the Swedish regional ethical committee of Uppsala University (Dnr 2015/423).

Design and Analyses

In line with the four hypotheses, four types of multiple hierarchical regression analyses were performed in order to investigate the role of personal and collective work identity in predicting motivation and justice at work:

(1) Personal- and collective work identity (predictors) and work self-determined motivation (criterion variable)

(2) Emotion- and cognition component of personal work identity (predictors) and work self-determined motivation (criterion variable)

(3) Personal- and collective work identity (predictors) and organizational pay justice (including procedural, distributive, interpersonal, informative dimensions as criterion variables)

(4) Emotion- and cognition component of collective work identity (predictors) and organizational pay justice (including procedural, distributive, interpersonal, informative dimensions as criterion variables)

In all four analyses, we controlled additionally for the effects of: monthly income; school sector (public vs. private); years of employment; and permanent employment (no vs. yes). These variables have previously been addressed as potential confounders, related to work self-determination motivation (Amabile et al., 1994; Vansteenkiste et al., 2007; Howard et al., 2016; Ryan and Deci, 2017) and organizational pay justice (Ambrose and Schminke, 2003; Andersson-Stråberg et al., 2007; Fortin, 2008). In order to specify a fixed order of entry to control for the effects of potential confounders, in the four multiple hierarchical regression analyses, the covariates were entered in step one and predictors in step two.

Results

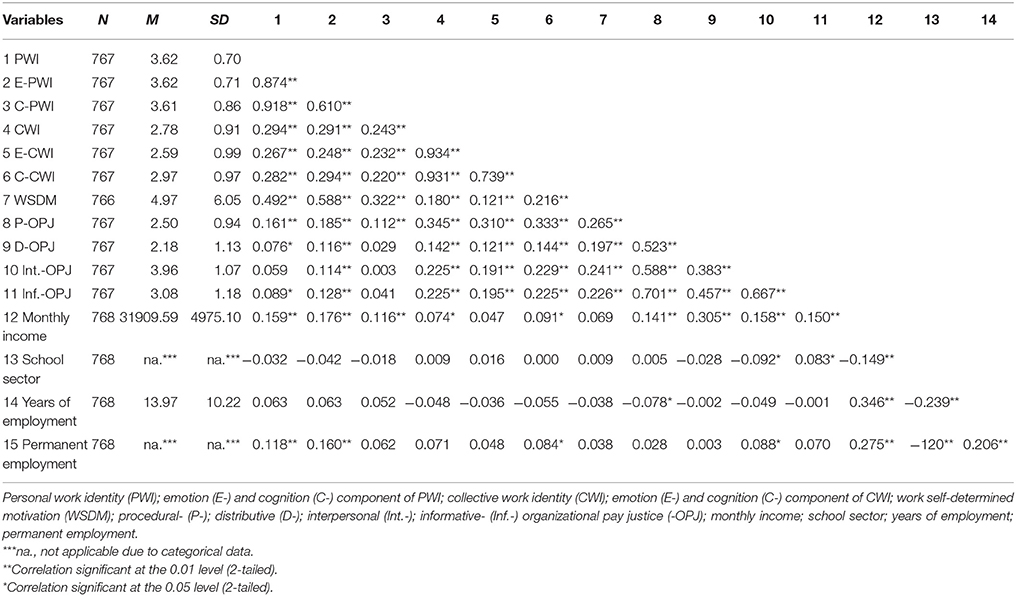

First, we report the bivariate correlations, N, mean and standard deviation statistics for all variables included in the regression analyses (see Table 1). Second, we report the results obtained in accordance with our hypotheses and the types of regression analyses associated with each one of the four hypotheses respectively (see section Design and Analyses). None of the statistical analyses below were subjected to multicollinearity effects, showing Tolerance values of >0.10, range 0.446–0.934 and all VIF (variance inflation factor) <10, range 1.070–2.242 (see Myers, 1990; Menard, 1995; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2012).

Table 1. Bivariate correlations (r), N, mean (M), and standard deviation (SD) statistics for all variables included in regression analyses.

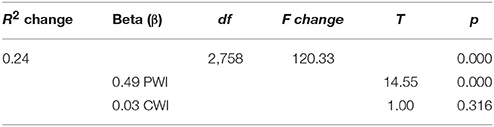

Personal- and Collective Work Identity and Work Self-determined Motivation

Together, personal- and collective work identity predicted work self-determined motivation, with an additional explained variance of 24% after controlling for the four potentially confounding variables. As predicted (Hypothesis 1), personal compared to collective work-related identity was shown to positively associate with work self-determined motivation (see Table 2; see also Appendix 1 for the first step regression statistics).

Table 2. Relation between personal- (PWI) and collective (CWI) work identity and work self-determined motivation after controlling for the four covariates (monthly income, school sector, years of employment, permanent employment).

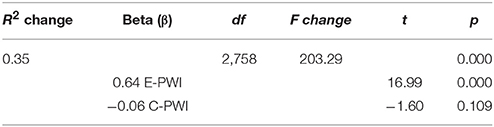

Emotion- and Cognition Component of Personal Work Identity and Self-determined Motivation

Together, emotion- and cognition components of personal work identity predicted work self-determined motivation, with an additional explained variance of 35% after controlling for the four potentially confounding variables. In agreement with Hypothesis 2, emotion- compared to cognition component of personal work identity was shown to positively associate with work self-determined motivation (see Table 3; see also Appendix 1 for the first step regression statistics).

Table 3. Relation between emotion- (E-) and cognition (C-) component of personal work identity (PWI) and work self-determined motivation after controlling for the four covariates (monthly income, school sector, years of employment, permanent employment).

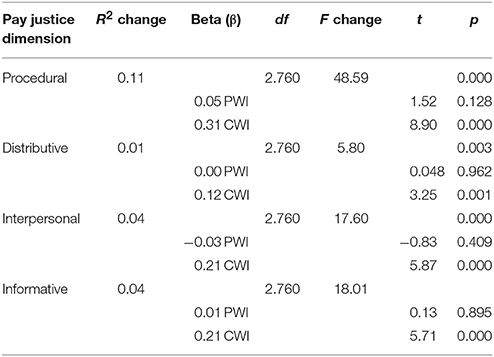

Personal- and Collective Work Identity and Organizational Pay Justice

Together, personal- and collective work identity predicted all organizational pay justice dimensions, with an additional explained variance of 11.1% in procedural pay justice, 1.3% in distributive pay justice, 4.2% in interpersonal pay justice and 4.4% in informative pay justice, respectively, after controlling for the four potentially confounding variables. Consistent with Hypothesis 3 collective- compared to personal work identity was shown to positively associate with all organizational pay justice dimensions (see Table 4; see also Appendix 2 for the first step regression statistics).

Table 4. Relation between personal- (PWI) and collective (CWI) work identity and organizational pay justice dimensions after controlling for the four covariates (monthly income, school sector, years of employment, permanent employment).

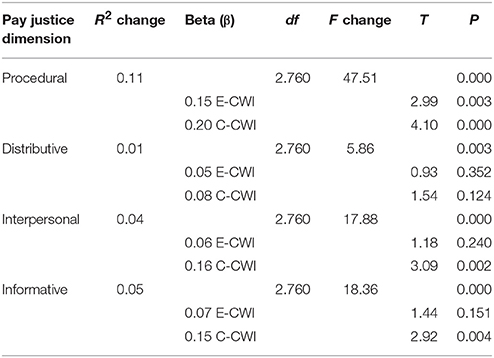

Emotion and Cognition Component of Collective Work Identity and Organizational Pay Justice

Together, emotion and cognition components of collective work identity predicted the organizational pay justice dimensions with an additional explained variance of 11% in procedural pay justice, 1.4% in distributive pay justice, 4.3% in interpersonal and 4.5% in informative pay justice, respectively, after controlling for the four potentially confounding variables. In line with Hypothesis 4, cognition vs. emotion component of collective work identity showed a stronger positive relationship with organizational pay justice, with exception for the distributive justice dimension. In other words, the cognition component of collective work identity accounted for a stronger association with three dimensions of organizational pay justice than did the emotion component of collective work identity (see Table 5; see also Appendix 2 for the first step regression statistics).

Table 5. Relation between emotion- (E-) and cognition (C-) component of collective work identity (CWI) and organizational pay justice dimensions after controlling for the four covariates (monthly income, school sector, years of employment, permanent employment).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the role of personal and collective work identity (including emotion and cognition components) in predicting motivation and justice at work, in a Swedish teacher sample (N = 768). In line with a general notion of focus of identification and its associated effects (van Dick and Wagner, 2002; Riketta and Van Dick, 2005; Olkkonen and Lipponen, 2006) and our predictions, we showed that both personal and collective work identity played significant, but different roles in predicting work-related motivation and organizational pay justice respectively. These relationships were, furthermore, not influenced by any of the previously suggested confounders of monthly income, school sector, years of employment, and permanent employment (Amabile et al., 1994; Ambrose and Schminke, 2003; Andersson-Stråberg et al., 2007; Vansteenkiste et al., 2007; Fortin, 2008; Howard et al., 2016; Ryan and Deci, 2017).

More precisely and concerning Hypotheses 1 and 2, it was shown that personal compared to collective work identity positively associated with work self-determined motivation, accounted for by the emotion component of personal work identity. Also, this is in accordance with previous research indicating that occupational task identity (i.e., personal identification) positively predicts all of the three psychological needs; competence, relatedness and autonomy, which may function as the basis of self-determined work motivation (Deci and Ryan, 2000; van den Broeck et al., 2016). Furthermore, the present results are in accordance with findings that collective (organizational) identity is neither positively nor negatively associated with satisfaction of personal motivators and needs, i.e., factors specific to the individual employee (Haslam et al., 2000), for example that collective identity is not associated with individual internal motivation (van Knippenberg and van Schie, 2000). By this, one might suppose that the personal- compared to collective work identity constitutes a crucial foundation on which satisfaction of the psychological needs (Deci and Ryan, 2000) is based.

The results related to Hypothesis 2 are in line with Knez (2014) and Knez and Eliasson (2017), showing that emotion component precedes the cognitive one in personal identity and by that accounts for its effects. This implies that the extent to which work motivation is self-determined, i.e. that employees are autonomously motivated in terms of pure satisfaction and interest, is stronger related to processes of personal work-related attachment/belongingness/closeness (emotion component), compared to cognitive processes of coherence, correspondence, mental time, reflection and agency (Knez, 2014, 2016). In general, this is also in line with findings showing that emotion may regulate intrinsic psychological processes (Gross, 2010), and enhance retention and recall in autobiographical memory (Canli et al., 2000; Phelps, 2006; Knez et al., 2017); a type of memory that grounds identity construction (Conway, 2005; Knez, 2017; Knez and Nordhall, 2017).

Regarding Hypotheses 3 and 4, collective compared to personal work identity was reported to positively associate with organizational pay justice accounted for by the cognition component of collective work identity. Firstly, this is in line with previous findings showing that the individual self-concept is not associated with organizational pay justice, while the collective self-concept is positively associated with different organizational pay justice dimensions (Johnson et al., 2006; Ehrhardt et al., 2012). This indicates that collective contrary to personal work identity has stronger associations with whether one judges the outcomes, procedures, interpersonal treatment and communication in an organizational context to be more or less fair. Furthermore, the results related to Hypothesis 3 are in line with the Accessible Identity Model which posits that how people define and perceive justice depends on which aspect of the self (social, personal etc.) dominates the working self-concept. Thus, in order to understand perceptions and reasons about justice one has to know the accessibility of different self-aspects, indicating the self as one of the predicting foundations of justice perceptions (Skitka, 2003).

Secondly, the results related to Hypothesis 4 are in accordance with previous studies indicating that in contrast to personal- collective (organizational) work identity is more of a cognitive structure (Harquail and King, 2003). Thus, how fair one judges the outcomes, procedures, interpersonal treatment and communication in an organizational context to be is strongly related to processes of incorporation, identification and assimilation making up the cognitive bond to the organization, compared to processes of affective commitment, esteem and pride making up the emotional bond to the organization (Mael and Ashforth, 1992; van Knippenberg and Sleebos, 2006).

Finally, our results are in general consistent with the suggestion that when focus of identity match the focus of outcome, the association will be stronger compared to when the two foci do not match (van Dick and Wagner, 2002; Riketta and Van Dick, 2005; Olkkonen and Lipponen, 2006). Given this, our findings extend the results of Riketta and Van Dick (2005) and Olkkonen and Lipponen (2006) by showing that the notion of foci of identification and its associated effects also yields both individual and collective work identity.

Conclusion

Our results highlight the importance of person-work bonding by suggesting that motivation and justice at work might be, to some extent, accounted for by the psychological mechanisms of work identity. We have also reported that these relationships were not influenced by the previously indicated confounders of monthly income, school sector, years of employment, and permanent employment (Amabile et al., 1994; Ambrose and Schminke, 2003; Andersson-Stråberg et al., 2007; Vansteenkiste et al., 2007; Fortin, 2008; Howard et al., 2016; Ryan and Deci, 2017). Hence, we have shown that the links between work identity and other work-related constructs are stronger when foci of categorization between the constructs match. As a result, when both the type of identity and the outcome are conceptually related the association will be stronger; however, differing across personal and collective work identity respectively. In other words, the emotion component of work identity was more pronounced in personal work-bonding relationships, and the cognitive component of work identity, in contrast, was more pronounced in collective work-bonding relationships.

Practically this implies that emotional personal- and cognitive collective work identity constitute psychological resources for the teachers in their everyday work setting (Bakker and Demerouti, 2008; Bakker and Bal, 2010; Choochom, 2016). More precisely, when teachers feel more and think less about their personal work-bonding, they are more self-determined motivated and so may have stronger need satisfaction regarding competence, relatedness and autonomy (Deci and Ryan, 2000; van den Broeck et al., 2016). By contrast, when teachers think more and feel less about their collective work-bonding, they experience a stronger sense of justice regarding the procedural, interpersonal and informative aspects of their payment.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of APA with written informed consent from all subjects. The project has been approved by the local ethical board, at the University of Uppsala, Sweden (Dnr 2015/423).

Author Contributions

ON collected the data, did the data analyses and wrote all manuscript sections together with IK.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02307/full#supplementary-material

References

Adams, J. S. (1965). “Inequity in social exchange,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 2, eds L. Berkowitz and W. Walster (New York, NY: Academic Press), 267–299.

Amabile, T. M., Hill, K. G., Hennessey, B. A., and Tighe, E. M. (1994). The work preference inventory: assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 66, 950–967. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.66.5.950

Ambrose, M. L., and Arnaud, A. (2005). “Are procedural justice and distributive justice conceptually distinct?” in Handbook of Organizational Justice, eds J. Greenberg, and J. A. olquitt (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 59–84.

Ambrose, M. L., and Schminke, M. (2003). Organization structure as a moderator of the relationship between procedural justice, interactional justice, perceived organizational support, and supervisory trust. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 295–305. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.295

Ambrose, M. L., and Schminke, M. (2009). The role of overall justice judgments in organizational justice research: a test of mediation. J. Appl. Psychol. 94, 491–500. doi: 10.1037/a0013203

Andersson-Stråberg, T., Sverke, M., and Hellgren, J. (2007). Perceptions of justice in connection with individualized pay setting. Econ. Indus. Democ. 28, 431–464. doi: 10.1177/0143831X07079356

Aryee, S., Budhwar, P. S., and Chen, Z. X. (2002). Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: test of a social exchange model. J. Organ. Behav. 23, 267–286. doi: 10.1002/job.138

Ashforth, B. E., and Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 14, 20–39.

Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2004). Intrinsic need satisfaction: a motivational basis of performance and weil-being in two work settings. J. Appl. Psychol. 34, 2045–2068. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02690

Bakker, A., and Bal, P. (2010). Weekly work engagement and performance: a study among starting teachers. J. Occupat. Organ. Psychol. 83, 189–206. doi: 10.1348/096317909X402596

Bakker, A., and Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Develop. Int. 13, 209–223. doi: 10.1108/13620430810870476

Bies, R. J. (2005). “Are procedural justice and interactional justice conceptually distinct?” in Handbook of Organizational Justice, eds J. Greenberg, J. A. Colquitt, J. Greenberg, and J. A. Colquitt (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 85–112.

Bjerregaard, K., Haslam, S. A., Morton, T., and Ryan, M. K. (2015). Social and relational identification as determinants of care workers' motivation and well-being. Front. Psychol. 6, 1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01460

Björklund, C. (2001). Work Motivation - Studies of its Determinants and Outcomes. Dissertation, Stockholm School of Economics.

Blader, S. L., and Tyler, T. R. (2009). Testing and extending the group engagement model: linkages between social identity, procedural justice, economic outcomes and extra role behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 94, 445–464. doi: 10.1037/a0013935

Bobocel, D. R., and Zdaniuk, A. (2005). “How can explanations be used to foster organizational justice?” in Handbook of Organizational Justice, eds J. Greenberg and J. A. Colquitt (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 469–497.

Brewer, M. B., and Gardner, W. (1996). Who is this “we”? Levels of collective identity and self representations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 71, 83–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.1.83

Byrne, B. (2016). Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS. Basic Concepts, Applications and Programming. New York, NY: Routledge Press.

Camus, A. (1942). Le Mythe de Sisyphe: The Myth of Sisyphus and other Essays. Transl. by J. O'Brien New York, NY: Vintage International.

Canli, T., Zhao, Z., Brewer, J., Gabrielli, J. D., and Cahill, L. (2000). Event-related activation in the human amygdala associates with lateral memory for individual emotional experience. J. Neurosci. 20:RC99.

Castanheira, F. (2016). Perceived social impact, social worth, and job performance: mediation by motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 37, 789–803. doi: 10.1002/job.2056

Castanheira, F., Chambel, M. J., Moretto, C., Sobral, F., and Cesário, F. (2016). “The role of leadership in the motivation to work in a call center,” in Self-Determination Theory in New Work Arrangements, eds M. J. Chambel, M. J. Chambel (Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers), 107–127.

Cho, J., and Treadway, D. (2011). Organizational identification and perceived organizational support as mediators of the procedural justice–citizenship behaviour relationship: a cross-cultural constructive replication. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 20, 631–653. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2010.487363

Choochom, O. (2016). A causal relationship model of teachers' work engagement. Int. J. Behav. Sci. 11, 143–152.

Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: a construct validation of a measure. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 386–400. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.386

Colquitt, J. A., and Shaw, J. C. (2005). “How should organizational justice be measured,” in Handbook of Organizational Justice, eds J. Greenberg, and J. A. Colquitt (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 113–152.

Colquitt, J. A., Greenberg, J., and Zapata-Phelan, C. P. (2005). “What is organizational justice? a historical overview,” in Handbook of Organizational Justice, eds J. Greenberg and J. A. Colquitt (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 3–56.

Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., Rodell, J. B., Long, D. M., Zapata, C. P., Conlon, D. E., et al. (2013). Justice at the millennium, a decade later: a meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. J. Appl. Psychol. 98, 199–236. doi: 10.1037/a0031757

Conway, M. A., and Holmes, A. (2004). Psychological stages and the accessibility of autobiographical memories across the life cycle. J. Person. 3, 461–480.

Conway, M. A., Singer, J. A., and Tagini, A. (2004). The self and autobiographical memory: correspondence and coherence. Soc. Cogn. 22, 495–537.

Corley, K. G., Harqail, C. V., Pratt, M. G., Glynn, M. A., Fiol, C. M., and Hatch, M. J. (2006). Guiding organizational identity through aged adolescence. J. Manag. Inquiry 15, 85–99. doi: 10.1177/1056492605285930

Cremer, D. D. (2006). Unfair treatment and revenge taking: The roles of collective identification and feelings of disappointment. Group Dynamics 3, 220–232.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The 'what' and 'why' of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inquiry 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2002). Handbook of Self-determination Research. University Rochester Press.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: a macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can. Psychol. 49, 182–185. doi: 10.1037/a0012801

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2010). “Intrinsic motivation,” in The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology, eds I. B. Weiner and W. E. Craighead (John Wiley and Sons, Inc.), 1–2. doi: 10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0467

DeVellis, R. F. (2003). Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ehrhardt, K., Shaffer, M., Chiu, W. K., and Luk, D. M. (2012). ‘National’ identity, perceived fairness and organizational commitment in a Hong Kong context: a test of mediation effects. Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 23, 4166–4191. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2012.655759

Ellemers, N., de Gilder, D., and Haslam, S. A. (2004). Motivating individuals and groups at work: a social identity perspective on leadership and group performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 29, 459–478. doi: 10.2307/20159054

Elliot, A. J., McGregor, H. A., and Thrash, T. M. (2002). “The need for competence,” in Handbook of Self-determination Research, eds E. L. Deci and R. M. Ryan (University Rochester Press), 339–360.

Folger, R., Cropanzano, R., and Goldman, B. (2005). “What is the relationship between justice and morality?” in Handbook of Organizational Justice, eds J. Greenberg and J. A. Colquitt (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 215–245.

Fortin, M. (2008). Perspectives on organizational justice: concept clarification, social context integration, time and links with morality. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 10, 93–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00231.x

Gagné, M., and Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 26, 331–362. doi: 10.1002/job.322

Gillet, N., Fouquereau, E., Lafrenière, M. K., and Huyghebaert, T. (2016). Examining the roles of work autonomous and controlled motivations on satisfaction and anxiety as a function of role ambiguity. J. Psychol. Interdisc. Appl. 150, 644–665. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2016.1154811

Gini, A. (1998).Work, identity and self: how we are formed by the work we do. J. Bus. Ethics 17, 707–714. doi: 10.1023/A:1017967009252

Greenberg, J. (1990). Organizational justice: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. J. Manag. 16, 399–432. doi: 10.1177/014920639001600208

Greenberg, J. (1993). “The social side of fairness: interpersonal and informational classes of organizational justice,” in Justice in the Workplace: Approaching Fairness in Human Resource Management, ed R. Cropanzano (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 79–103.

Greenberg, J. (2010). Organizational injustice as an Occupational Health Risk. Acad. Manag. Annals 4, 205–243. doi: 10.1080/19416520.2010.481174

Greenberg, J. (2011). “Organizational justice: the dynamics of fairness in the workplace,” in APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 3 Maintaining, Expanding, and Contracting the Organization, eds S. Zedeck and S. Zedeck (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 271–327.

Greenberg, J., and Cohen, R. L. (1982). “Why Justice? Normative and instrumental interpretations,” in Equality and Justice in Social Behavior, eds J. Greenberg and R. L. Cohen (New York, NY: Academic), 437–469.

Greenberg, J., and Colquitt, J. A. (2005). Handbook of Organizational Justice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Gross, J. J. (2010). “Emotion regulation,” in Handbook of Emotions, eds M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, and L. Feldman Barrett (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 497–512.

Harquail, C. V., and King, A. W. (2003). Organizational identity and embodied cognition: a multi-level conceptual framework. Acad. Manage Proc. 2003, E1–E6. doi: 10.5465/AMBPP.2003.13792529

Haslam, S. A., and Ellemers, N. (2005). “Social identity in industrial and organizational psychology: concepts, controversies and contributions,” in International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 20, ed G. P. Hodgkinson (Chichester: Wiley), 39–118.

Haslam, S. A., Powell, C., and Turner, J. C. (2000). Social identity, self-categorization, and work motivation: rethinking the contribution of the group to positive and sustainable organizational outcomes. Appl. Psychol. 49, 319–339. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00018

He, H., Zhu, W., and Zheng, X. (2014). Procedural justice and employee engagement: roles of organizational identification and moral identity centrality. J. Busin. Ethics 122, 681–695. doi: 10.1007/s10551-013-1774-3

Hogg, M. A. (2012). “Social identity and the psychology of groups,” in Handbook of Self and Identity, 2nd Edn., eds M. R, Leary and J. P. Tangney (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 502–519.

Hogg, M. A., and Terry, D. J. (2000). Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 25, 121–140. doi: 10.2307/259266

Houkes, I., Janssen, P. P., Jonge, J. d., and Bakker, A. B. (2003). Specific determinants of intrinsic work motivation, emotional exhaustion and turnover intention: a multi sample longitudinal study. J. Occupat. Organ. Psychol. 76, 427–450. doi: 10.1348/096317903322591578

Howard, J., Gagn,é, M., Morin, A. J., and Van den Broeck, A. (2016). Motivation profiles at work: a self-determination theory approach. J. Vocat. Behav. 95–96, 74–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2016.07.004

Jackson, C. L., Colquitt, J. A., Wesson, M. J., and Zapata-Phelan, C. P. (2006). Psychological collectivism: a measurement validation and linkage to group member performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 91, 884–899. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.884

Jayaweera, T. (2015). Impact of work environmental factors on job performance, mediating role of work motivation: a study of hotel sector in England. Int. J. Busin. Manag. 10, 271–277. doi: 10.5539/ijbm.v10n3p271

Johnson, R. E., and Jackson, E. M. (2009). Appeal of organizational values is in the eye of the beholder: the moderating role of employee identity. J. Occupat. Organ. Psychol. 82, 915–933. doi: 10.1348/096317908X373914

Johnson, R. E., Chang, C., and Yang, L. (2010). Commitment and motivation at work: the relevance of employee identity and regulatory focus. Acad. Manag. Rev. 35, 226–245. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2010.48463332

Johnson, R. E., Selenta, C., and Lord, R. G. (2006). When organizational justice and the self-concept meet: consequences for the organization and its members. Organizational Behavior And Human Decision Processes, 99, 175–201. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.07.005

Kihlstrom, J. F., and Klein, S. B. (1994). “The self as a knowledge structure,” in Handbook of Social Cognition, Vol. 1, eds R. S. Wyer and T. K. Srull (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 153–208.

Kihlstrom, J. F., Beer, J. S., and Klein, S. B. (2003). “Self and identity as memory,” in Handbook of Self and Identity, eds M. R. Leary, J. P. Tangney, M. R. Leary and J. P. Tangney (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 68–90.

Klein, S. B. (2014). Sameness and the self: philosophical and psychological considerations. Front. Psychol. 5:29. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00029

Klein, S. B., German, T. P., Cosmides, L., and Gabriel, R. (2004). A theory of autobiographical memory: necessary components and disorders resulting from their loss. Soc. Cogn. 5, 460–490.

Knez, I. (2014). Place and the self: an autobiographical memory synthesis. Philos. Psychol. 27, 164–192. doi: 10.1080/09515089.2012.728124

Knez, I. (2016). Toward a model of work-related self: a narrative review. Front. Psychol. 7, 1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00331

Knez, I. (2017). Life goals, self-defining life goal memories, and mental time travel among women and men going through emerging versus entering adulthood: an explorative study. Psychol. Consc. 4, 414–426. doi: 10.1037/cns0000123

Knez, I., and Eliasson, I. (2017). Relationships between personal and collective place-identity and well-being in mountain communities. Front. Psychol. 8:79. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00079

Knez, I., and Nordhall, O. (2017). Guilt as a motivator for moral judgment: an autobiographical memory study. Front. Psychol. 8:750. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00750

Knez, I., Ljunglöf, L., Arshamian, A., and Willander, J. (2017). Self-grounding visual, auditory, and olfactory autobiographical memories. Consc. Cogn. 52, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2017.04.008

Latham, G. P., and Pinder, C. C. (2005). Work motivation theory and research at the dawn of the Twenty-First Century. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 56, 485–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142105

Law, K. S., Wong, C. S., and Mobley, W. H. (1998). Toward a taxonomy of multidimensional constructs. Acad. Manage. Rev. 23, 741–755. doi: 10.5465/AMR.1998.1255636

Lee, E. S., Park, T. Y., and Koo, B. (2015). Identifying organizational identification as a basis for attitudes and behaviors: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bullet. 141, 1049–1080. doi: 10.1037/bul0000012

Leventhal, G. S. (1980). “What should be done with equity theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships,” in Social Exchange: Advances in Theory and Research, eds K. Gergen, M. Greenberg, and R. Wallis (New York: Plenum Press), 27–55.

Lipponen, J., Wisse, B., and Perälä, J. (2011). Perceived justice and group identification: the moderating role of previous identification. J. Person. Psychol. 10, 13–23. doi: 10.1027/1866-5888/a000029

López-Cabarcos, M. Á., Machado-Lopes-Sampaio-de Pinho, A. I., and Vázquez-Rodríguez, P. (2015). The influence of organizational justice and job satisfaction on organizational commitment in Portugal's hotel industry. Cornell Hospit. Q. 56, 258–272. doi: 10.1177/1938965514545680

Mael, F. A., and Tetrick, L. E. (1992). Identifying organizational identification. Educ. Psychol. Measur. 52, 813–824. doi: 10.1177/0013164492052004002

Mael, F., and Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: a partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 13, 103–123. doi: 10.1002/job.4030130202

McConnell, A. R. (2011). The multiple self-aspects framework: self-concept representation and its implications. Person. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 15, 3–27. doi: 10.1177/1088868310371101

Menard, S. (1995). Applied Logistic Regression Analysis. Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, 07-106. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Millward, L., and Haslam, A. (2013). Who are we made to think we are? Contextual variation in organizational, workgroup and career foci of identification. J. Occupat. Organ. Psychol. 86, 50–66. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.2012.02065.x

Miscenko, D., and Day, D. (2016). Identity and identification at work. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 6, 215–247. doi: 10.1177/2041386615584009

Ndjaboué, R., Brisson, C., and Vézina, M. (2012). Organizational justice and mental health: a systematic review of prospective studies. Occupat. Environ. Med. 69, 694–700. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2011-100595

Nicklin, J. M., McNall, L. A., Cerasoli, C. P., Strahan, S. R., and Cavanaugh, J. A. (2014). The role of overall organizational justice perceptions within the four-dimensional framework. Social Justice Res. 27, 243–270. doi: 10.1007/s11211-014-0208-4

Nowakowski, J. M., and Conlon, D. E. (2005). Organizational justice: looking back, looking forward. Int. J. Conflict Manag. 16, 4–29. doi: 10.1108/eb022921

Olkkonen, M., and Lipponen, J. (2006). Relationships between organizational justice, identification with organization and work unit, and group-related outcomes. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decision Process. 100, 202–215. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.08.007

Pate, J., Beaumont, P., and Pryce, G. (2009). Organizations and the issue of multiple identities: who loves you baby? VINE 39, 319–338. doi: 10.1108/03055720911013625

Peklar, J., and Boštjančič, E. (2012). Motivation and life satisfaction of employees in the public and private sectors. Mednarodna Revija za Javno Upravo 10:57.

Phelps, E. A. (2006). Emotion and cognition: insights from studies of the human amygdala. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 57, 27–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070234

Piccoli, B., and De Witte, H. (2015). Job insecurity and emotional exhaustion: testing psychological contract breach versus distributive injustice as indicators of lack of reciprocity. Work Stress 29, 246–263. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2015.1075624

Pinder, C. (2008). Work Motivation in Organizational Behavior, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Psychological Press.

Reichers, A. E. (1985). A review and reconceptualization of organizational commitment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 13, 95–109.

Rich, B. L., LePine, J. A., and Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 53, 617–635. doi: 10.5465/AMJ.2010.51468988

Riketta, M. (2005). Organizational identification: a meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 66, 358–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2004.05.005

Riketta, M., and Van Dick, R. (2005). Foci of attachment in organizations: a meta-analytic comparison of the strength and correlates of workgroup versus organizational identification and commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 67, 490–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2004.06.001

Robbins, J. M., Ford, M. T., and Tetrick, L. E. (2012). Perceived unfairness and employee health: a meta-analytic integration. J. Appl. Psychol. 97, 235–272. doi: 10.1037/a0025408

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000a). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000b). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25, 54–67. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2002). “An overview of self-determination theory: an organismic-dialectical perspective,” in Handbook of Self-determination Research, eds E. L, Deci and R. M. (Ryan University Rochester Press), 3–36.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2012). “Multiple identities within a single self: a self-determination theory perspective on internalization within context and cultures,” in Handbook of Self and Identity, 2nd Edn., eds M. R. Leary and J. P. Tangney (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 225–256.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2017). “Work and Organizations: promoting wellness and productivity,” in Self-determination Theory- Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development and Wellness, eds R. M. Ryan and E. L. Deci (New York, NY: The Guildford Press), 532–558.

Saltson, E., and Nsiah, S. (2015). The mediating effects of motivation in the relationship between perceived organizational support and employee job performance. Int. J. Econ. Comm. Manag. 3, 654–667.

Sedikides, C., Gaertner, L., and O'Mara, E. M. (2011). Individual self, relational self, collective self: hierarchical ordering of the tripartite self. Psychol. Stud. 56, 98–107. doi: 10.1007/s12646-011-0059-0

Skitka, L. J. (2003). Of different minds: an accessible identity model of justice reasoning. Person. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 7, 286–297. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0704_02

Sluss, D. M., and Ashforth, B. E. (2007). Relational identity and identification: defining our-selves through work relationships. Acad. Manage. Rev. 32, 9–32. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2007.23463672

Smith, N. V. (2012). Equality, justice and identity in an expatriate/local setting: which human factors enable empowerment of Filipino aid workers? J. Pacific Rim Psychol. 6, 57–74. doi: 10.1017/prp.2012.10

Spell, C. S., and Arnold, T. J. (2007). A multi-level analysis of organizational justice climate, structure, and employee mental health. J. Manag. 33, 724–751. doi: 10.1177/0149206307305560

Stajkovic, A. (2006). Development of a core confidence-higher order construct. J. Appl. Psychol. 6, 1208–1224. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1208

Steers, R. M., Mowday, R. T., and Shapiro, D. L. (2004). Introduction to special topic forum: the future of work motivation theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 29, 379–387. doi: 10.2307/20159049

Stoeber, J., Davis, C. R., and Townley, J. (2013). Perfectionism and workaholism in employees: the role of work motivation. Person. Indiv. Differ. 55, 733–738. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.06.001

Tabachnick, B. G., and Fidell, L. S. (2012). Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th Edn. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Tajfel, H., and andTurner, J. C. (1979). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict,” in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds W.G. Austin and S. Worchel (Monterey: CA: Brooks/Cole), 33–47.

Tajfel, H., and andTurner, J. C. (1986). “The social identity theory of intergroup behavior,” in Psychology of Intergroup Behavior, eds S. Worchel and W. G. Austin (Chicago, IL: Nelson), 7–24.

Thibaut, J. W., and Walker, L. (1975). Procedural Justice: A Psychological Analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Tremblay, M. A., Blanchard, C. M., Taylor, S., Pelletier, L. G., and Villeneuve, M. (2009). Work extrinsic and intrinsic motivation scale: its value for organizational psychology research. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 41, 213–226. doi: 10.1037/a0015167

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., and Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell.

Tyler, T. R., and Blader, S. L. (2003). The group engagement model: procedural justice, social identity, and cooperative behavior. Person. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 7, 349–361. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0704_07

Vallerand, R. J., and Ratelle, C. F. (2002). “Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: a hierarchical model,” in Handbook of Self-determination Research, eds E. L. Deci and R. M. Ryan (University Rochester Press), 37–64.

van den Broeck, A., Ferris, D. L., Chang, C., and Rosen, C. C. (2016). A review of self-determination theory's basic psychological needs at work. J. Manag. 42, 1195–1229. doi: 10.1177/0149206316632058

van Dick, R., and Wagner, U. (2002). Social identification among school teachers: dimensions, foci, and correlates. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 11, 129–149. doi: 10.1080/13594320143000889

van Knippenberg, D. (2000). Work motivation and performance: a social identity perspective. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 49, 357–371. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00020

van Knippenberg, D., and Sleebos, E. (2006). Organizational identification versus organizational commitment: self-definition, social exchange, and job attitudes. J. Organ. Behav. 27, 571–584. doi: 10.1002/job.359

van Knippenberg, D., and van Schie, E. M. (2000). Foci and correlates of organizational identification. J. Occupat. Organ. Psychol. 73, 137–147. doi: 10.1348/096317900166949

Vansteenkiste, M., Neyrinck, B., Niemiec, C. P., Soenens, B., De Witte, H., and Van den Broeck, A. (2007). On the relations among work value orientations, psychological need satisfaction and job outcomes: a self-determination theory approach. J. Occupat. Organ. Psychol. 80, 251–277. doi: 10.1348/096317906X111024

Wang, H. J., Lu, C. Q., and Siu, O. L. (2015). Job insecurity and job performance: the moderating role of organizational justice and the mediating role of work engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 100, 1249–1258. doi: 10.1037/a0038330

Wilson, A. E., and Ross, M. (2003). The identity function of autobiographical memory: time is on our side. Memory 11, 137–149. doi: 10.1080/741938210

Keywords: work identity, personal identity, collective identity, work motivation, organizational justice

Citation: Nordhall O and Knez I (2018) Motivation and Justice at Work: The Role of Emotion and Cognition Components of Personal and Collective Work Identity. Front. Psychol. 8:2307. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02307

Received: 13 July 2017; Accepted: 19 December 2017;

Published: 15 January 2018.

Edited by:

Konstantinos G. Kafetsios, University of Crete, GreeceReviewed by:

Chris Myburgh, University of Johannesburg, South AfricaAthena Xenikou, Hellenic Air Force Academy, Greece

Copyright © 2018 Nordhall and Knez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ola Nordhall, b2xhLm5vcmRoYWxsQGhpZy5zZQ==

Ola Nordhall

Ola Nordhall Igor Knez

Igor Knez