Abstract

Despite changes in their representation and visibility, there are still serious concerns about the inclusion and day-to-day workplace challenges various groups face (e.g., women, ethnic and cultural minorities, LGBTQ+, people as they age, and those dealing with physical or mental disabilities). Men are also underrepresented in specific work fields, in particular those in Health care, Elementary Education, and the Domestic sphere (HEED). Previous literature has shown that group stereotypes play an important role in maintaining these inequalities. We outline how insights from research into stigma, social identity, and self-regulation together increase our understanding of how targets are affected by and regulate negative stereotypes in the workplace. This approach starts from the basis that members of negatively stereotyped groups are not just passive recipients of negative attitudes, stereotypes, and behaviors but are active individuals pursuing multiple goals, such as goals for belonging and achievement. We argue that it is only by understanding stigma from the target’s perspective (e.g., how targets are affected and respond) that we can successfully address workplace inequality. Key in this understanding is that stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination have taken on much more subtle forms, with consequences for the way members of stigmatized groups cope. These insights lead us to propose an approach to understanding barriers to workplace equality that highlights four key aspects: (1) the different (often subtle) potential triggers of identity threat in the workplace for members of stigmatized groups; (2) the ways in which members of stigmatized groups cope with these threats; (3) the role of supportive factors that mitigate potential threats and affect self-regulation; and (4) potential hidden costs for the self or others of what appears at first to be effective self-regulation. The focus on threats, coping, support, and potential hidden costs helps us understand why current diversity efforts are not always successful in increasing and maintaining members of stigmatized groups in organizations and provides insight into how we can aid efforts to effectively lower barriers to workplace equality.

Introduction

Despite changes in their representation and visibility, women and ethnic and cultural minorities are still strongly underrepresented in various work fields and higher occupational positions. Similarly, there are serious concerns about the inclusion and day-to-day workplace challenges facing LGBTQ+ people (Hebl et al., 2002), people as they age (Diekman and Hirnisey, 2007), and people dealing with physical or mental disabilities (Wilson-Kovacs et al., 2008). Men are also underrepresented in specific work fields, in particular those in Health care, Elementary Education, and the Domestic sphere (HEED; Croft et al., 2015).

The underrepresentation of these social groups is problematic as equitable representation is an indicator of the presence of equal opportunities and social justice (Eagly, 2016; Ellemers and Rink, 2016). Also, in inclusive work climates, diversity can positively affect corporate performance and team effectiveness (Gonzalez and Denisi, 2009; Nishii, 2013; Van Knippenberg et al., 2013; Ellemers and Rink, 2016), and people are more attracted to organizations perceived as concerned with justice and morality (Van Prooijen and Ellemers, 2015). There is thus a need to tackle the underrepresentation of different social groups in work contexts.

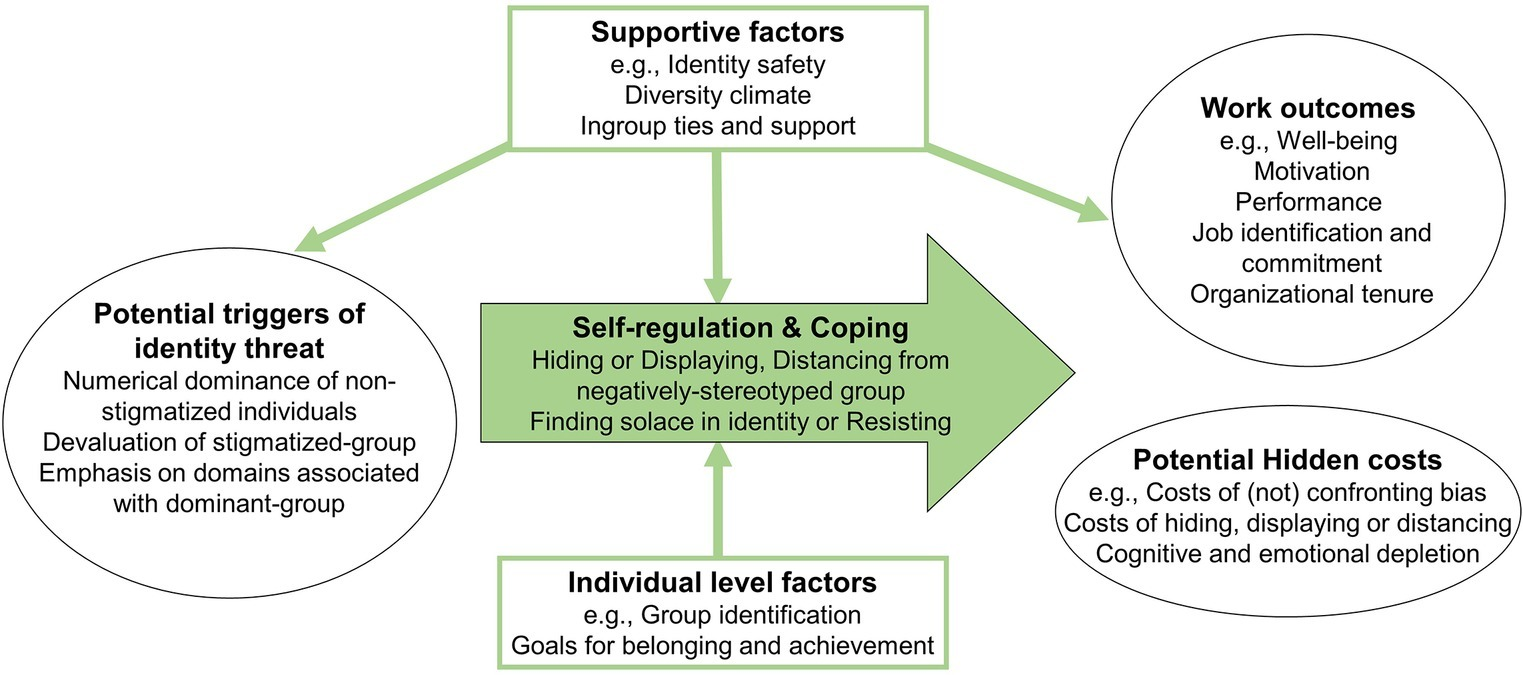

Tackling underrepresentation means understanding why these inequalities continue to exist despite increased movement toward equality. We argue that to truly understand and hence successfully address workplace inequality, it is vital to know how members of underrepresented groups are affected by and respond to the workplace challenges they face. We outline a target-focused approach that integrates research on stigma and social identity with work on self-regulation. We begin with insights from research into stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination that helps us understand the potential workplace threats members of stigmatized groups face. We then move on – from this focus on “perpetrators” of inequality and on targets as passive victims – to a focus on targets as active agents coping with stigma-related threat. Specifically, we make the case that four key aspects need to be understood to address workplace inequality (see Figure 1): (1) the different potential triggers of identity threat; (2) the ways individuals self-regulate and cope with these threats and the individual level factors that affect this; (3) supportive workplace factors that can mitigate the impact of threat; and (4) recognition of the potential hidden costs of regulating such threats.

Figure 1

Conceptual model: a threat, support, and potential hidden costs approach to understand how members of stigmatized groups cope with workplace inequality.

Together these four key aspects present a base for building successful programs addressing workplace inequality. The focus on threats, coping, support, and potential hidden costs brings a more comprehensive understanding of the complexities and nuances by which stigma has its often subtle effects. It demonstrates that taking the target’s perspective into account is indispensable in effectively lowering workplace equality barriers. As such, it helps us understand why current workplace diversity efforts that tend to focus on either fixing the perpetrator or fixing the victim are not always successful in attracting and retaining members of stigmatized groups, and provides tools to effectively approach stigma in the workplace.

A Short History of Psychological Research on Social Inequalities

To understand how individuals cope with workplace stigma, we need to first give an overview of how the field of psychology has approached the topic of social inequalities over time. For many years, research on inequalities focused on the origins of bias and discrimination. This work sought to understand why majority or high-status groups have negative attitudes, prejudices, and stereotypes, and how these can be altered to increase social equality. Major insights followed from such work into what stereotypes are, how they form and affect outcomes of members of stereotyped groups. This included insights into – and the complexities of – reducing stereotypes (for reviews, see Nelson, 2009; Dovidio et al., 2010b).

Increasingly, however, it became clear that this work on external barriers faced by members of stigmatized groups was missing an important part: an understanding of the ways members of stigmatized groups experience stigma. This emphasis came much later, from the late 1980s onward, along with the increased representation of members of negatively stereotyped groups in the field as researchers. In part through this influx, social inequalities were looked at from a different perspective, examining questions that gave a more central place to the experiences of targets of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination. Initially, this work focused on the target as a passive recipient, and evidenced the harm being done. This highlighted that targets can become threatened in their social identity as members of stigmatized groups, with consequences for their well-being, motivation, and performance (e.g., for overviews, Smith et al., 2007; Schmader et al., 2008; Emerson and Murphy, 2014). Increasingly, however, this work emphasized that members of stigmatized groups are not just passive recipients who in essence are waiting around to be discriminated against, but that they also respond and in this way influence outcomes. This was reflected, for example, in early key work by Crocker and Major and by Swim on the target’s perspective (Crocker and Major, 1989; Crocker et al., 1998; Swim et al., 1998; Oyserman and Swim, 2001). The research increasingly showed that members of disadvantaged groups are quite resilient to stigma and that it is too simple to assume that experiences with prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination automatically get transformed into low well-being and negative educational or work outcomes (Barreto, 2014; Leach and Livingston, 2015; De Lemus et al., 2016).

Increasingly then, the field has begun to examine active coping with stigma and has made substantial gains in understanding exactly how these coping processes work, with this work based on three main literatures that overlap and feed into one another: first, major strides were made through research from the social identity perspective which from its earliest days focused on how group identities affect relations between groups and on how identity processes affect cognition, affect, and behavior (e.g., Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987; Ellemers et al., 1999, 2002). Research on social identities made clear that social identities are malleable (can be emphasized or deemphasized), that people are motivated to pursue a positive sense-of-self, and that this self stems in part from the social groups to which people feel they belong. When a group is valued in a given context (for instance, at work), one’s membership in this group – or social identity – can increase one’s positive sense-of-self. However, when a group is devalued (i.e., faces negative stereotypes, is discriminated against), one’s sense-of-self can become threatened. Further work noted that such social identity threats trigger targets’ responses to reduce the threat. These responses include individual mobility (e.g., attempting to acquire higher workplace status), emphasizing other, more valued qualities of one’s group (e.g., emphasizing that women bring superior interpersonal skills to the workplace), or taking collective steps to challenge the lower position of one’s group (e.g., advocacy for workplace equal opportunity policies). This clarified the important role of groups in coping with negative stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination, and the different personal and social identity strategies people may use to protect a positive sense-of-self (e.g., Heilman, 2012).

The second literature base for strides in understanding how targets cope with negative stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination came in the form of the stigma perspective that became increasingly merged with the social identity perspective over time (e.g., Crocker and Major, 1989; Steele and Aronson, 1995; Aronson et al., 1998; Crocker et al., 1998; Swim et al., 1998; Oyserman and Swim, 2001; Schmader et al., 2008; Shelton et al., 2010; Barreto, 2014). Early work outlined how people identify and react to prejudice in interpersonal and intergroup settings. Increasing insight was gained into the effects of stigma on targets’ assessments of their abilities, motivation, and performance and on self-esteem and well-being (Crocker et al., 1998; Swim and Stangor, 1998). Related work examined social stigma as a potential stressful event (e.g., Miller and Major, 2000; Miller and Kaiser, 2001; Miller, 2006), noting that a stress response occurs when individuals perceive a self-relevant threat that exceeds their coping resources (Miller and Major, 2000; Miller and Kaiser, 2001; Major and O’Brien, 2005). Not only several coping efforts to regulate emotion, cognition, and behavior, but also one’s own physiology and the environment were proposed as responses to stressful events or circumstances (Connor-Smith et al., 2000; Compas et al., 2001). For instance, people can cope through increased engagement (e.g., enhancing a sense of personal control, changing the way one thinks about a situation through positive thinking or cognitive restructuring), or disengagement (coping efforts that disengage from or avoid the stressor; Miller and Kaiser, 2001; Miller, 2006). The stigma and coping perspective helped understand emotional, cognitive, and behavioral coping and clarified how the same stressor may be more or less impactful and may lead to different coping responses for different people and in different situations.

Lastly, our understanding of how members of stigmatized groups respond to negative stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination has been increasingly influenced by work from a self-regulation perspective (e.g., Carver and Scheier, 1998, 2002; Swim and Thomas, 2006; Fiske, 2008; Higgins, 2012; Inzlicht and Legault, 2014). This work takes as a premise that people actively pursue multiple goals. Every individual has core social motives that drive behavior (e.g., esteem, belonging, self-enhancement), and these can become more or less of a concern through the situation people find themselves in (Fiske, 2004; Vignoles et al., 2006; Vignoles, 2011). Self-regulation processes begin when people compare their perceptions of the current situation with their goals or standards (Carver and Scheier, 1998, 2002). A comparison that reveals a discrepancy between inputs and desired goals creates motivation to reduce the discrepancy. Applied to the workplace, the self-regulation perspective leads to the understanding that responses of members of stigmatized groups need to be examined from a goal perspective – distinguishing, for example, goals for achievement and belonging, and that – depending on which goal is salient – people may come to different responses.

Together the blending of these three sets of literature have provided a much better base to understand how individuals cope with stigma in the workplace – e.g., stereotype threat as a cost of identity threat and stigma regulation as discussed later. Also, not only did insights regarding coping with stigma develop and change over time, so did the groups being studied. Early work focused on women and ethnic minorities as the prototypical groups facing stigma. It was only much more recently – also in response to societal changes in laws, attitudes, and interests that increased the visibility of other targets – that others started to be studied, including LGBTQ+, individuals facing age-related workplace stereotypes, and individuals facing physical or mental disabilities. An important recent addition is the focus on men facing stereotypes in fields where they are underrepresented (in particular in HEED – Health care, Elementary Education, and the Domestic sphere; Croft et al., 2015; Meeussen et al., 2019). Also, recent research has begun to focus on intersectionality, examining the experiences of individuals who are members of more than one stigmatized group (Purdie-Vaughns and Eibach, 2008; Cole, 2009; O’Brien et al., 2015; Remedios and Snyder, 2018). While many of the processes of threat and coping and their consequences are shared, each group is also characterized by particular characteristics or experiences (e.g., how visible identities are, whether there is one or multiple stigmas as for female ethnic minorities, what the costs of confronting stigma are, whether a stigma broadly affects many domains or a particular domain [e.g., stigma facing ethnic minorities vs. men in HEED]). In fact, through research focusing on each of these groups, the field as a whole has gained a much more thorough understanding of threat and coping, with insights and questions particularly relevant for one group aiding insights for other groups (e.g., see Deaux and Lafrance, 1998; Creed, 2006; Wilson-Kovacs et al., 2008; Crandall et al., 2009; Herek, 2009; Hebl et al., 2010; Dovidio et al., 2010a).

Building on these research traditions described above, we outline a threat, support, and potential hidden costs approach to help understand how individuals cope with workplace prejudice, discrimination, and stereotypes. As noted, we discuss four key aspects to help address workplace inequality: (1) understanding the different potential triggers of threat; (2) understanding how individuals cope with these threats; (3) identifying the supportive factors that may minimize these threats; and (4) increasing insight into the potential hidden costs of regulating identity threat.

Potential Triggers of Threat in the Workplace

In order to address the threats individuals face in the workplace and to counteract barriers to workplace equality, it is important to understand the different (often very subtle) factors that can trigger identity threat. Identity threat is the psychological threat arising from possible devaluation of one’s group (Branscombe et al., 1999a). While related terms are used in other literatures (e.g., stressor, demand), we use the term typical of the social identity tradition. As we outline below, workplace identity threat can result from three kinds of triggers. These triggers may be activated solely or together, and each trigger can point to different solutions to reduce workplace inequality. The first is the higher workplace numerical presence of members of the non-stigmatized group, the second the devaluation and discrimination of the stigmatized group, and the third a workplace emphasis on characteristics and domains typically associated with the non-stigmatized group (for related discussions, see Inzlicht and Ben-Zeev, 2000; Steele et al., 2002; Van Laar et al., 2010).

The Numerical Dominance of the Non-Stigmatized Group

First, increasing evidence shows how the numerical dominance of the non-stigmatized group in the workplace can by itself already present a threat to members of stigmatized groups. This results from basic group processes: people categorize themselves and others into ingroups and outgroups based on observable similarities and differences (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987). Being different from others along a specific dimension (e.g., gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, and disability) makes that dimension more salient (Wilder, 1984) and increases the expectation that one will be viewed in terms of that dimension (Frey and Tropp, 2006). Negative stereotypes associated with that dimension then also become more salient (e.g., Heilman, 1983; Avery et al., 2008; Somvadee and Morash, 2008) and in turn affect outcomes (effects of stereotypes on outcomes are discussed in the next section).

Consistent with this, considerable work in social psychology has demonstrated effects of being in the numerical minority. Generally, environments can be perceived as more identity threatening when they contain fewer others of one’s group (i.e., when they lack critical mass; e.g., Allmendinger and Hackman, 1995; Cohen and Swim, 1995; Sekaquaptewa and Thompson, 2002, 2003; Avery et al., 2008; Duguid, 2011). When in the minority, individuals tend to become vigilant regarding the minority identity, with various negative consequences (Emerson and Murphy, 2014). Illustrative is research in STEM domains (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math), a domain where women tend to be in the numerical minority. Research by Murphy et al. (2007) showed that women in STEM viewing a video of a STEM conference depicting a majority of men/minority of women (vs. a balanced ratio) exhibited more cognitive and physiological vigilance, reported lower belonging, and had less desire to participate in the conference (see also Richman et al., 2011). Men were not influenced by the numerical representation in this (for them) identity-safe domain. Similarly, Inzlicht and Ben-Zeev (2000) have shown that women’s (but not men’s) math performance can become impaired when in a numerical minority, but not when gender is balanced. Relational demography research has also shown numerical underrepresentation (in terms of gender, age, and ethnicity) to be associated with lower organizational commitment, lower job satisfaction, lower work motivation and performance, and increased turnover (Liao et al., 2004; Riordan et al., 2004), particularly when the numerical representation triggered increased perceived conflict between the work identity and the underrepresented-group identity (Veldman et al., 2017). Among African-American professionals, research has related numerical underrepresentation to lower well-being and stronger experiences with employment discrimination (Jackson et al., 1995; Avery et al., 2008). Also, the effects of numerical underrepresentation can be additive when someone is part of multiple minority groups (Jackson et al., 1995; Remedios and Snyder, 2018). In other words, a female leader of color in a predominantly White and masculine context is affected not only by her ethnic minority status (as one of few Blacks) but also by her gender minority status (as one of few women). Moreover, not only generally numerical-representation matters, but particularly also representation at the various (and especially higher) levels of the organizational hierarchy (Unzueta and Binning, 2012), and for some groups numerical underrepresentation is a given, due to their actual numerical minority status in society (e.g., sexual minorities, people with disabilities). Also, those with a concealable stigma have a harder time identifying others who share their stigma and may thus have an even harder time feeling there is any presence of their group.

The Devaluation of Stigmatized Groups

A second way in which identity threat can be triggered in the workplace is through devaluation of stigmatized groups. One of the clearest cues regarding devaluation is seeing discrimination, and many studies have shown the negative effects of experiencing prejudice and discrimination, including higher stress and lower psychological well-being – and lower psychological and physical health more generally (Pascoe and Smart Richman, 2009; Schmitt et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2016).

While blatant discrimination is an obvious cue, devaluation in a given organizational context is often more likely to come from smaller subtler cues. While blatant cues explicitly display negative attitudes toward a group, subtle cues convey the same belief as blatant messages but in more covert and often unintentional ways (Dovidio, 2001; Barreto and Ellemers, 2005; Ellemers and Barreto, 2015). When such subtle cues signal an identity’s low value in a specific context, this particular group identity becomes salient for the group member, and a vigilance process is initiated. This directs stigmatized individuals’ attention toward additional cues to determine the value and meaning of their social identity in that context (Murphy et al., 2007; Murphy and Taylor, 2012). If situational cues confirm the possibility a social identity may be negatively evaluated, vigilance increases. Also, chronic and situational expectations about being stigmatized increase attention to identity-relevant cues (Kaiser et al., 2006). In fact, a single subtle cue can trigger experiences of social identity threat even if the setting exhibits no overt evidence of prejudice or discrimination (Murphy et al., 2007). Also, one cue can determine the interpretation of another (ambiguous cue) in both positive and negative directions (Kaiser et al., 2006).

One of the strongest demonstrations of contextual cues triggering these effects comes from the extensive stereotype-threat literature. Hundreds of studies have now shown that cues making salient negative group stereotypes trigger concern about being judged on the basis of these stereotypes (Steele et al., 2002). In fact, the stereotypes may even only exist in the mind of the stigmatized group member: for stereotype threat to occur, others around one do not need to hold a negative stereotype of the group, one only need to believe that they do. This concern can set in motion anxiety, mind wandering, negative thinking, and a wish to disprove the stereotype. These together co-opt working memory, resulting in decreases in performance and lower well-being (e.g., Steele and Aronson, 1995; Blascovich et al., 2001; Steele et al., 2002; Schmader and Johns, 2003; Cadinu et al., 2005; Johns et al., 2008; Schmader et al., 2008; Inzlicht and Schmader, 2012; Mendes and Jamieson, 2012; Schmader and Beilock, 2012; Pennington et al., 2016; Spencer et al., 2016). Research in organizational contexts has shown that experiences with stereotype threat negatively affect career aspirations, career confidence, and professional identification (see Kalokerinos et al., 2014 for an overview). Also, the effects of stereotype threat have been shown in all kinds of groups. For example, stereotype threat has been related to more negative job attitudes and increased turnover intentions among female employees in the legal profession (Von Hippel et al., 2011); to higher turnover intentions among male primary school teachers (Kalokerinos et al., 2017); and to more negative job attitudes, poorer work mental health, and increased intentions to resign among older employees (von Hippel et al., 2013).

Information as to whether a certain identity is devalued can come from various types of cues. For example, workplace cues that make a specific identity and accompanying stereotypes salient (e.g., when physical access to important company locations is difficult for employees in a wheelchair) or from cues that signal the (under)representation of a stigmatized group (e.g., company photos showing only White males). Devaluation can also come from more general cues that signal an organization’s diversity beliefs and values (e.g., value for meritocracy that may fail to acknowledge structural inequalities) or from organizational structures and policies (e.g., colorblind policies that may fail to recognize the existence and value of different cultural identities; see Emerson and Murphy, 2014). Numerous studies have shown the negative effects of such workplace cues. For instance, when objects in a computer science environment were stereotypically male, women were less interested in computer science and felt less of a sense of belonging (Cheryan et al., 2009; see also Murphy et al., 2007). Similarly, Hall et al. (2015, 2019) showed among female engineers that low acceptance cues from others in daily conversations (rather than explicitly hostile cues) led to a sense of identity threat, which in turn increased mental exhaustion and disengagement (see also Ahlqvist et al., 2013). Other studies have shown similar negative cue effects, for example, lowered leadership aspirations in women following exposure to gender stereotypic advertisements (Davies et al., 2005). Also, Avery et al. (2007) showed that organizational cues indicating low value for diversity predict higher absenteeism in African-American employees. Similarly, Purdie-Vaughns et al. (2008) showed that cues suggesting low minority representation coupled with cues suggesting the organization values colorblindness (vs. values diversity) led to higher identity threat and workplace distrust in African-American professionals.

This work shows that devaluation often stems from small subtle triggers that have profound effects, an understanding key to addressing devaluation in the workplace.

Emphasis on Domains Associated With the Dominant Group

A third way in which threats can present themselves to members of stigmatized groups is through the workplace emphasis on domains perceived to describe the non-stigmatized group more than the stigmatized group (Derks et al., 2006, 2007a). This can result in lower perceived fit and a threatening environment for members of stigmatized groups, leading to lower well-being, lower motivation and disengagement, and lower performance and higher turnover intentions.

Research on role congruity has shown, for example, how emphasis on domains or characteristics perceived to better fit the non-stigmatized than one’s stigmatized group may trigger identity threat (Heilman, 1983; Eagly and Karau, 2002; Lyness and Heilman, 2006; Bongiorno et al., 2014). Much of this work has been conducted with regard to gender. Thus, in traditionally masculine professions such as STEM domains, the police force, or the military, characteristics traditionally associated with men are more strongly valued than characteristics traditionally associated with women (Somvadee and Morash, 2008; Archbold et al., 2010; Cheryan et al., 2017). However, perceived role (in)congruity affects other groups and intersectional identities, too: e.g., older employees – stereotyped as rigid and unadaptable – are at a disadvantage in rapidly changing work domains (Diekman and Hirnisey, 2007), and employees with a mental illness may experience added prejudice when their mental illness is seen as stereotypical of the other gender (Koenig and Eagly, 2014).

Other research has also shown that there can be a mismatch between qualities, values, or norms that tend to be associated with members of traditionally underrepresented groups and the settings they are entering and that this is subtly signaled in the context (Stephens et al., 2012a,b, 2014; Schmader and Sedikides, 2018; Veldman et al., 2019). For example, Gaucher et al. (2011) showed that this may occur for women through job descriptions that use more masculine-themed words (e.g., emphasizing dominance, competitiveness). Men too are perceived as not fitting HEED domains that emphasize traditionally female qualities such as being nurturing, helping others, and being emotionally involved (Cejka and Eagly, 1999; Fiske et al., 2002; Wayne and Cordeiro, 2003; Rajacich et al., 2013; Rudman and Mescher, 2013).

Conclusions Regarding Potential Triggers of Threat in the Workplace

In summary, three kinds of triggers may elicit threat for members of stigmatized groups at work, and each trigger may call for different solutions to reduce workplace inequality (we discuss these in the implications section). First, members of stigmatized groups tend to be in the numerical minority in the workplace. Being in the minority and dissimilar from others tends to make that social identity salient, with negative consequence for well-being, motivation, and performance. Second, devaluation – often through subtle small environmental cues – can profoundly affect the outcomes of members of negatively stereotyped groups. Third, the emphasis on domains stereotypically associated with the dominant group can create an expectation of underperformance and an unwelcoming work environment for members of stigmatized groups. As this overview shows, the group identities themselves are not the problem: it is the threat that comes along with that identity in particular contexts and in various ways that can result in negative consequences for well-being, motivation, turnover, and performance. Also, all of these factors tend to work together: workplace underrepresentation sends the message that the reasons for the underrepresentation of a particular group are legitimate – the result of the lower abilities or skills on the part of these individuals. This bolsters devaluation and maintains segregated roles and contexts that themselves then reconfirm the stereotypes.

While the above research identifies the various potential triggers of threat and the substantial effects of these threats for members of stigmatized groups, research has also brought a much better understanding of the intricate ways that members of negatively stereotyped groups have found to cope with these threats. We turn to this issue next.

How People Cope With Stigma-Related Threat

As discussed, the current understanding of stigma reflects members of stigmatized groups not as passive recipients of stigma-related threats but as active actors pursuing multiple goals in the workplace and beyond (Fiske, 2004, 2008; Swim and Thomas, 2006). Although identity threat can threaten various goals, two key ones are the goal to achieve (to feel competent, to do well) and the goal to belong (to fit in, to feel at home; Steele et al., 2002; Barreto, 2014; Hall et al., 2015). Potential threats to these goals trigger self-regulatory processes and coping, with people adjusting behavior, cognition, and affect to try to achieve these goals (Carver and Scheier’s 1998, 2002; Affect-Alarm Model of Self-Control – Miller and Major, 2000; Inzlicht and Legault, 2014). Workplace threats can differentially affect these specific goals and in turn trigger different regulatory responses that can move people in different directions (Steele et al., 2002; Swim and Thomas, 2006). Thus, concerns for achievement may lead members of stigmatized groups to try even harder to overcome doubts surrounding their group membership. Alternatively, people may disengage or exit if they perceive they cannot change others’ attitudes, or if the challenge is too great, too stressful, or simply too aversive (see also Wrosch et al., 2003). Concerns for belonging meanwhile may lead people to focus on social relations: attempting to increase their fit with others, seeking solace in their shared identity with similar others at work, or working together with these others to challenge workplace barriers. Also here, concerns for belonging may lead members of stigmatized groups to exit the environment and seek environments with increased belonging.

These goals for achievement and belonging need to be understood in the context of the modern workplace where forms of bias have taken on much more subtle, harder to recognize forms (Dovidio, 2001; Barreto and Ellemers, 2005; Cortina, 2008; Ellemers and Barreto, 2015). Blatant forms of bias and discrimination are increasingly less acceptable – so while they are more easily protested against than in the past, they are also much less pervasive (see also Operario and Fiske, 2001). Instead individuals have to face more subtle cues, leaving them unsure whether in fact discrimination or devaluation occurred (e.g., Crosby et al., 1993; Williams et al., 2003; Sterk et al., 2018) – which may make responses that do not involve claiming bias or collectively protesting more likely in the workplace (Wright et al., 1990; Becker, 2012; Branscombe et al., 2012). We address a number of these responses here, varying from hiding and concealing stigmatized identities to finding solace in one’s group and resisting.

Hiding, Displaying, and Distancing

One of the ways members of stigmatized groups may deal with identity threat is through attempting to acquire, display, or emphasize the qualities they perceive to be important or valued in the context and hide or conceal those that are not. Individuals alter their self-presentation in these ways to try and avoid bias and rejection by coworkers and to increase their belonging (an assimilation strategy – Garcia and Crocker, 2008; Newheiser and Barreto, 2014; Newheiser et al., 2017). People may emphasize or display the qualities that they believe to be most fitting in the context (for instance, ethnic minority employees emphasizing ethnic majority characteristics, or women in leadership positions emphasizing agentic characteristics; Derks et al., 2011a,c, 2015; see also earlier discussion on workplace emphasis on domains associated with the dominant group). Additionally, individuals may hide or conceal their threatened identities. For instance, individuals have been found to hide (vs. reveal) concealable stigmatized identities, such as LGBTQ+ identity, having a history of mental illness, or poverty (Newheiser and Barreto, 2014). Similarly, Pronin et al. (2004) showed that women strongly identified with math disavowed traditionally feminine characteristics strongly associated with – but not those that weakly associated with – the gender-math stereotype.

People often combine hiding and displaying in “self-group distancing” as an identity management strategy. Specifically, upwardly mobile members of negatively stereotyped groups may increasingly distance themselves from their negatively stereotyped group in the workplace (Pronin et al., 2004; Derks et al., 2011a,c, 2015, 2016; Becker and Tausch, 2014; Faniko et al., 2017). This can occur inadvertently – as the individual tries to best fit the environment dominated by members of the non-stigmatized group – or more strategically, when upwardly mobile individuals recognize that presenting the self in ways more acceptable to the non-stigmatized group may bring certain benefits (e.g., being perceived as a potential future leadership candidate) or avoid costs (e.g., avoid restrictions on access to key social networks). A number of indicators of self-group distancing have been found, including an increased emphasis on one’s outgroup characteristics, emphasizing that one is different from other members of one’s stigmatized group, concealing the devalued identity, increasing the expression of stereotypical views of other members of one’s group, and denying the existence of bias against one’s group (Ellemers et al., 2004; Pronin et al., 2004; Burkley and Blanton, 2008; Derks et al., 2011c, 2015, 2016; Becker and Tausch, 2014; Faniko et al., 2017). Such self-group distancing behaviors can be mild (e.g., Gay employees not objecting when stereotypes about LGBTQ+ are voiced in meetings) to more major (e.g., a female employee saying that the underrepresentation of women in the company is an indication that women simply do not have what it takes to excel).

When women show self-group distancing behavior, this has been referred to as “Queen bee” behavior. Women have indeed been found to show self-group distancing behavior in response to existing stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination in their organizations (Pronin et al., 2004; Cohen and Garcia, 2005; Derks et al., 2011a,c, 2015; Kaiser and Spalding, 2015). For instance, senior policewomen showed more self-group distancing following reminders of gender bias at work (Derks et al., 2011c). Research has also shown that individuals who are less identified with their stigmatized group are more likely to self-group distance under threat, and indeed high identifiers may not show distancing at all (e.g., Derks et al., 2009, 2015; Kaiser and Spalding, 2015). This is consistent with other work within the social identity approach showing that low identifiers may be less loyal and faithful to the group as threats increase, while high identifiers are more likely to stay loyal and choose collective routes to address inequality (Derks et al., 2009; Hersby et al., 2009; Iyer and Ryan, 2009; Ellemers and Van Laar, 2010). As such then, self-group distancing appears to be an identity management strategy aimed at benefitting individual mobility and individual-level outcomes (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Derks et al., 2007b, 2016).

However, self-group distancing occurs not only for women but also for other groups (see Derks et al., 2016 for reviews). Older adults, for example, respond to stigma with reduced group identification, and by indicating that they feel younger than they are (Weiss and Lang, 2012). Also, following priming with ethnic bias, ethnic minorities present themselves in ways fitting the ethnic majority group (Derks et al., 2015), and contact with the majority group increases the likelihood that ethnic minorities will distance (Becker et al., 2013). Also, Gay men have been found to distance themselves from the stigma of the “feminine” homosexual by emphasizing their masculinity and rejecting Gays they see as stereotypically “feminine” (Eguchi, 2009; Hunt et al., 2016). Even in minimal groups created in laboratory settings, being undervalued and underrepresented induces self-group distancing (Wright and Taylor, 1999).

Hiding, displaying, or distancing can be effective to the degree that this presentation of the self is accepted by the various workplace parties. Also, hiding one’s identity is possible to the degree that identities are concealable (e.g., low SES, sexual orientation, mental illness), and less easy for visible identities such as gender or ethnicity (Quinn, 2017). Acquiring, displaying, or emphasizing qualities typical of the dominant group meanwhile is more generally available to all kinds of groups. However, this may not always be accepted by other members of one’s stigmatized group (Marques and Paez, 1994; Van Laar et al., 2014), or may lead to rejection by members of the dominant group who do not accept the altered presentation. This has been shown, for example, in the case of women showing more agentic (and lower communal) traits and behaviors, and as a result being rejected by both men and women (Fiske et al., 1991; Rudman and Glick, 2001; Gabriel et al., 2017). Similarly, men are not always accepted, welcomed, or valued when showing more communal qualities, for example, in HEED domains (Lockwood and Kunda, 1999; Wayne and Cordeiro, 2003; Lockwood, 2006; Bell-Scriber, 2008; Rudman and Mescher, 2013). Lastly, various personal and group costs may result from self-group distancing, hiding, and concealment, as we will see later in the section on potential hidden costs.

Finding Solace in Identity or Resisting

While members of stigmatized groups may try to hide, conceal, or minimize their threatened identity, emphasize their outgroup characteristics, or more generally distance from their stigmatized group, they may also go in the opposite direction: finding solace in strong group identities that they share with others, or resisting prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination (Branscombe et al., 2012).

Research on identity affirmation has shown that strong group identities can indeed bring solace. This work is grounded in extensive research on the function of group identities, with group identities providing a base for self-definition, allowing individuals to maintain their distinctiveness, and to enhance positive views of the self (Spears et al., 1997; Ellemers et al., 2002; Jetten et al., 2014). Specifically, this work shows that members of stigmatized groups benefit when they themselves (or the surrounding context, as outlined later under “supportive factors”) value or affirm positive aspects of this identity (Biernat et al., 1996; Sherman and Cohen, 2002; Sherman et al., 2007; Oswald and Chapleau, 2010; Ghavami et al., 2011; Latrofa et al., 2012). Research has shown that members of stigmatized groups indeed personally affirm group identity in response to threat (Derks et al., 2006, 2007a; Latrofa et al., 2012; see also Crocker and Major, 1989), and that this identity affirmation helps against stereotype threat (Logel et al., 2009), buffers self-esteem (Spencer-Rodgers et al., 2016), and protects motivation and performance (Derks et al., 2006, 2007a), in part by decreasing physiological threat and increasing physiological challenge (Derks et al., 2011b). Such affirmation of group identities is particularly likely to be shown by those more highly identified with their group (Derks et al., 2009; Hersby et al., 2009; Iyer and Ryan, 2009; Ellemers and Van Laar, 2010). Work on the rejection-identification model has similarly shown that rejection may motivate a return to the group (Branscombe et al., 1999b – but see Begeny and Huo, 2017, 2018 for potential costs of identification through cognitive saliency).

Members of stigmatized groups may also obtain extra motivation precisely from the stereotypes they face, trying extra hard to show the stereotypes are wrong (e.g., Steele et al., 2002; Keller, 2007; Grimm et al., 2009; Ståhl et al., 2012a; Leach and Livingston, 2015). Research using psycho-physiological indices (Blascovich et al., 2000) has shown that people indeed can resist negative effects of stereotypes, showing efficient mobilization of energy and turning threat experiences into a challenge to perform well despite negative stereotypes (Derks et al., 2011b). For example, research with women with high leadership efficacy found increased leadership identification on confrontation with gender stereotypes about leadership. They also performed better in a leadership task, despite this being physiologically stressful for them (Hoyt and Blascovich, 2007, 2010). Additionally, research has shown that when experiencing gender inequality, higher group identification may prompt resistance, resulting in greater activation of reversed gender stereotypes, stronger leadership aspirations, more persistence in stereotypically masculine domains, and greater support for collective action (De Lemus et al., 2013, 2015; Leicht et al., 2017; Van Breen et al., 2018).

Research shows that people usually do not start with resistance. Often they first try to work within the system, adapting to the new situation and trying harder, using affirmations or other ways of coping, and only when this is not effective turning to the stigmatized group to try to work together (Wright et al., 1990; Boen and Vanbeselaere, 2000; Iyer and Ryan, 2009; Branscombe et al., 2012). As discussed earlier, such direct collective responses may be less likely in modern workplaces where bias is perceived as being in the past, and less identifiable and pervasive. Altogether then, there is substantial evidence that people may find solace in strong group identities, and the sharing of these identities with others of their group, and may also find strong motivation precisely from the stereotypes they face.

Conclusions Regarding Coping With Threat

In summary, research on coping has provided increasing insight into the various ways in which members of stigmatized groups deal with identity threat. As workplace bias has taken more subtle and ambiguous forms in many societies, more indirect responses to stigma (such as hiding, displaying, and distancing from the group, or conversely finding solace in identity and resisting the group stereotypes) are also more likely. Members of negatively stereotyped groups may minimize or conceal the threatened identity in the workplace in an effort to fit in, triggering the identity as little as possible in the minds of those with whom they interact. They may try extra hard to do well, to show the stereotypes are wrong, obtaining extra motivation precisely from the stereotypes they face. When such efforts appear insufficient, individuals may disengage from the domain altogether in an effort to protect well-being, and instead focus on domains in which they expect they may be more successful.

Of course, even though members of stigmatized groups are active agents coping with threat, this does not mean that the responsibility to do so must (only) lie with them (Ellemers and Barreto, 2015). Considerable research has provided insights into the factors in the work environment that may mitigate the effects of identity threat, and how this can be useful to organizations in their efforts to reduce workplace inequality. We discuss these contextual supportive factors next.

Supportive Factors That Mitigate Threat or Its Effects

Increasing evidence is providing a better understanding of how supportive factors outside the individual may help members of stigmatized groups cope with identity threat in the workplace. Specifically, as shown in Figure 1, supportive factors can affect whether potential triggers of identity threat are in fact experienced as threats; affect the self-regulation and coping strategies that are available to members of stigmatized groups; and can directly affect the outcomes of members of stigmatized groups. We review recent work on identity safety and diversity climate factors (including colorblind vs. multiculturalist approaches), plus the importance of ingroup ties, role models and support for members of stigmatized groups.

Identity Safety and Diversity Climate

An important way to reduce identity threats or the consequences of identity threat experienced by members of negatively stereotyped groups in work settings is through the creation of identity safety. Identity safety makes it less likely that identity threat is triggered. Also, identity-safe environments reduce the need to regulate any threats and directly affect outcomes. This research emerges from a number of different angles: for instance, work with groups that are in conflict or that differ in power has shown that feeling one’s group is accepted is a prerequisite for members of low status or negatively stereotyped groups to move toward reconciliation (Shnabel et al., 2009; Saguy and Kteily, 2014). Also, identity safety can be effectively created through contextual identity affirmations, signaling that a social group is valued within this organization. Affirmation of identities of importance to members of underrepresented groups has been found to protect well-being, motivation, and performance (Derks et al., 2006, 2007a, 2009; Van Laar et al., 2010). For example, contextual identity affirmation has been found to lower identity threat among those of low socio-economic status (Stephens et al., 2015), and to lower identity threat and increase well-being, motivation, and perceptions of opportunity in the workplace among young Muslim women (Van Laar et al., 2013).

One key way in which identity safety is communicated is through the diversity climate of an organization. The diversity climate signals the extent to which the workplace is open to various social groups (Huo and Molina, 2006; Purdie-Vaughns et al., 2008; Gonzalez and Denisi, 2009; Plaut, 2010). For members of stigmatized groups, perceiving a positive diversity climate that accepts, respects, and values their group helps reduce threat, relates to feeling more included, stronger organizational identification and commitment, and lower turnover intentions (e.g., Luijters et al., 2008; Gonzalez and Denisi, 2009; Plaut et al., 2009; Choi and Rainey, 2013; Podsiadlowski et al., 2013; Meeussen et al., 2014; Van Laer, 2018). Interestingly, diversity climates have effects beyond the groups specifically targeted: men of color, for instance, experience identity safety from organizational diversity policies aimed at women, and women from ethnic diversity policies (Chaney et al., 2016).

A positive diversity climate in a work organization is not sufficient if numerical underrepresentation, presence of negative stereotypes and devaluation, and the emphasis on domains associated with the dominant group outlined earlier are not addressed. A recent study showed, for example, that among women in the police force, experiencing a positive diversity climate only partially reduced the negative effects of underrepresentation, with the women continuing to show negative consequences of underrepresentation on identity conflict (Veldman et al., 2017). Other work has shown the dangers of piecemeal diversity initiatives and “token” minority representation (i.e., representation of only a few minority group members) that can blind people to existing inequality (Brady et al., 2015; Kirby et al., 2015; Anisman-Razin and Saguy, 2016; Gündemir and Galinsky, 2017), and should therefore not constitute the sole strategy to advance equality (see also Hentschel et al., 2013). Also, in generating a positive diversity climate, it is important that organizations also pay attention to the needs of the majority or high-status individuals, who similarly use information on diversity climate as an indicator of the degree to which their identity is accepted. They may resist diversity efforts within an organization when they feel that these put their group at a disadvantage (Avery et al., 2013). Thus, a focus on the value of differences in multiculturalism may be interpreted by majority members as a lack of value for their “standard” identity (Stevens et al., 2008; Plaut et al., 2011). Instead, researchers identify an all-inclusive multicultural climate or a multicultural meritocracy as most effective, with these focusing on identity safety not just for members of negatively stereotyped groups, but making sure that members of dominant or majority groups also feel valued and included (Stevens et al., 2008; Emerson and Murphy, 2014; Gündemir et al., 2017; see also Ellemers and Rink, 2016).

One aspect of a positive diversity climate that serves as an indicator of identity safety and an antidote to workplace threats for stigmatized groups is organizational support. Support can be proximal or distal, and can come in the form of instrumental support that provides tangible help to solve a problem or issue, or in the form of emotional support, offered through empathy and caring (Cohen and Wills, 1985; Wills, 1985; House et al., 1988; Richman et al., 2011; London et al., 2011a,b). As discussed earlier, possessing a social stigma in the workplace is a potentially stressful event (Miller and Major, 2000; Miller and Kaiser, 2001), and support can increase the perceived resources to cope with the stressor, thus even turning threat into positive challenge (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984a,b; Cohen and Wills, 1985; Miller, 2006). For members of stigmatized groups, experiencing support in the organization – or perceiving that it is available – predicts stronger engagement and better achievement outcomes (Eccles, 1994; Walton and Cohen, 2007; Hartman and Hartman, 2008; Richman et al., 2011; Baysu et al., 2014). Such support can come from various sources: e.g., support from representatives of the majority high-status group in the workplace can lower negative effects of stigma-related threat, and support may be especially important from those in positions of authority or power (e.g., Baruch-Feldman et al., 2002; Drury and Kaiser, 2014). Support from both these sources signals acceptance and value for the stigmatized group, and can create new norms throughout an organization, particularly in organizations where members of stigmatized groups are underrepresented, face strong negative stereotypes, or where domains associated with the dominant group are more strongly emphasized. Hall et al. (2015) showed this in their recent daily-diary study among female engineers, where having positive work conversations with male colleagues cueing acceptance protected the women from identity threat. Importantly, such positive conversations were more likely to occur in organizations perceived to have more gender-inclusive policies (i.e., in identity-safe organizational cultures; Hall et al., 2018). Recent work is more generally beginning to address support for diversity by members of high-status groups, examining the conditions under which members of high-status groups may offer support, for example as allies, and the effects this support can have (e.g., Saguy et al., 2008; Fingerhut, 2011; Becker et al., 2013; Saguy and Dovidio, 2013; Cihangir et al., 2014; Drury and Kaiser, 2014; Brown, 2015; Simon and O’Brien, 2015; Droogendyk et al., 2016; Emina et al., 2018; Good et al., 2018). In our own work, we are examining, for example, support in military and police organizations, examining whether men become more aware of gender inequality in their organization through contact with women, and effects of this contact on their support for gender-related social change.

Importance of Ingroup Ties and Support

In lieu of or in addition to identity safety or support from the high-status majority group in the workplace, ingroup support can also provide a resource to mitigate threat. Obtaining workplace ingroup support can become more difficult if one’s group is underrepresented and if the stigma is concealed or not visible. However, ingroup support outside the organization can then offer additional possibilities. Positive effects of a connection with the ingroup when under threat is predicted by various social-psychological models, including the rejection-identification model (Branscombe et al., 1999b), and the stereotype inoculation model which shows ingroup members to function as “social vaccines,” who inoculate and strengthen fellow group members (Dasgupta, 2011), and backed up by substantial evidence (e.g., Correll and Park, 2005; Haslam et al., 2005; Bakouri and Staerklé, 2015; see also Richman et al., 2011 – but see Begeny and Huo, 2017, 2018 for potential negative effects of increased cognitive salience following identification). People are particularly likely to seek ingroup support when identity threat is high or pervasive (Branscombe et al., 2012). Such support helps individuals overcome various negative effects of threat (e.g., Cohen et al., 2000; McLeroy et al., 2001; Ostberg and Lennartsson, 2007; Rosenthal et al., 2013), increases psychological well-being, and decreases distress (Turner, 1981; Haslam et al., 2005). Ingroup support may also encourage people to pursue (rather than avoid) activities in which they are negatively stereotyped. Men, for instance, are more likely to increase engagement in HEED domains and increase HEED occupational aspirations when told that other men support and value communal characteristics (Van Grootel et al., 2018). Even through mere presence of similar others, support can lift self-esteem, improve mood (Frable et al., 1998), and provide a buffer for social identity threat (Levin et al., 2006; Richman et al., 2011).

A particular case of ingroup support comes through support from ingroup leaders and role models (see also, Unzueta and Binning, 2012). For members of stigmatized groups, demographic similarity with supervisors (e.g., ethnic or gender similarity) is related to reduced absenteeism and tardiness, and increased intent to remain in the organization (Avery et al., 2012). Also, seeing examples of successful members of one’s stigmatized group has been found to improve self-evaluations and performance, give inspiration and proof others can do it, and increase aspirations and motivation (Lockwood and Kunda, 1999; Marx and Roman, 2002; McIntyre et al., 2003, 2005; Lockwood, 2006; Marx et al., 2009; O’Brien et al., 2016; Dennehy and Dasgupta, 2017). For men too, having male role models in HEED domains increases interest in elementary teaching and nursing (e.g., Cochran and Brassard, 1979). Recent work by Morgenroth et al. (2015) suggests that role models have three distinct functions: acting as behavioral models, representing the possible, and being inspirational.

Conclusions Regarding the Effects of Supportive Factors in Work Environment

In conclusion, research on identity safety, diversity climates, and ingroup and outgroup support suggests various ways in which supportive factors in the workplace may buffer threat or help cope with threat. Supportive factors may also moderate which self-regulation and coping are available and used to deal with threat (and this would be an interesting avenue for future research). For instance, the presence of supportive (minority) networks in the organization makes it easier to display and find solace in an identity, and to show resistance when identity-threatening experiences do occur. Meanwhile, hiding and distancing are more likely when such supportive networks or positive diversity climates are not available. This – and the work reviewed above – also highlights the benefits for members of stigmatized groups to maintain their links with other members of their group for the protection of well-being, motivation, and performance in the workplace. In addition, support from the dominant group may be key as majority individuals are still more likely to be in positions of power and seen as legitimate sources of workplace information (Drury and Kaiser, 2014). Hence, ingroup and outgroup support processes can contribute to efforts to address workplace inequality.

Potential Hidden Costs of Dealing With Stigma

As outlined above, we have quite good understanding of the potential threats facing members of stigmatized groups in work settings. While the threats can be significant, we also know that individuals have various coping strategies at their disposal, and environments can offer important sources of support. Nevertheless, dealing with stigma – even if seemingly effectively – can have important unintended and hidden costs, either for the stigmatized individuals themselves or for other members of their group. These costs are often not at all obvious, and understanding these potential costs is important to effectively address workplace equality in the long run. Below, we discuss costs that can be particularly consequential in the workplace: costs of (not) confronting bias, costs of concealing identity and distancing from one’s group, and cognitive and emotional depletion following stigma regulation.

Costs of (Not) Confronting Bias

One of the hardest tasks members of stigmatized groups face is deciding whether to confront or not confront the injustice they experience in the workplace, because confronting others with claims of bias or discrimination entails risks. Research has shown that members of stigmatized groups who confront bias are less likely to be believed and are evaluated less favorably than members of majority groups addressing the same bias. This is true even when the bias is acknowledged and blatant (e.g., Swim and Hyers, 1999; Czopp and Monteith, 2003; Kaiser and Miller, 2003; Czopp et al., 2006; Kaiser, 2006; Shelton et al., 2006; Rasinski and Czopp, 2010; Becker et al., 2011, 2014; Eliezer and Major, 2012; Gervais and Hillard, 2014). Also, given that bias cues have become more subtle, these costs can become even higher as the legitimacy of bias attributions is more ambiguous.

Deciding whether to confront or not can thus be a very difficult decision, and members of stigmatized groups may ruminate extensively on what is best. Even when they do not confront, this rumination about whether they should have confronted can last long after the situation has passed. Also, when they do not confront, members of stigmatized groups can face costs, such as guilt or shame about not confronting injustice, or feeling they have let down or sold out the group (Shelton et al., 2006). Also, non-confrontation may leave members of stigmatized groups feeling inauthentic, feeling they failed to be loyal to their true selves and personal goals. Such dissonance has been found to be so aversive that people who do not confront sometimes minimize the seriousness of the bias claim to restore a positive sense-of-self (Rasinski et al., 2013).

Costs of Hiding, Displaying, and Distancing

Potential costs can also result from coping strategies that involve hiding threatened identities; emphasizing outgroup characteristics; and from distancing from the negatively stereotyped group more generally. These costs can be incurred by the self as well as by other ingroup members.

First, hiding, concealing, or distancing from an identity in the workplace can be a costly strategy for the self. Individuals hide, conceal, and distance because they believe others will view them more favorably when they minimize their stigmatized identity, and that they will thus be less likely to experience bias or discrimination (Quinn, 2017, 2018). Also, they believe that distancing from the stigmatized identity will increase their chances for acceptance and belonging (Newheiser and Barreto, 2014). However, research has shown that concealment often tends to have the opposite effect: leading individuals to feel lower belonging and acceptance (Newheiser et al., 2017). This is driven in part by people reducing their self-disclosure also of other self-relevant information beyond the stigmatized identity, and by feeling less authentic in interactions (Newheiser and Barreto, 2014). Also, research has shown that hiding (vs. revealing) a stigmatized identity is detected by external observers and by non-stigmatized interaction partners, who have less positive impressions of the person, and of the interaction, when the person conceals an identity (Newheiser and Barreto, 2014). Moreover, as with failure to confront, members of stigmatized groups may feel disloyal to their ingroup following distancing (Goldman and Kernis, 2002; Shelton et al., 2005). Distancing also lowers opportunities to obtain support from the ingroup, further increasing negative consequences for the self (Branscombe et al., 1999b; Haslam et al., 2005; Van Laar et al., 2014; Derks et al., 2016). Such findings show that distancing from one’s stigmatized identity in an organization can be a costly strategy.

Not only the self, but others too may experience costs from hiding or distancing. Recent research suggests that self-group distancing behavior by women in leadership positions has harmful effects for junior women exposed to this behavior (Sterk et al., 2018). Behaviors such as the denial of gender bias and expressions of negative views of women may be taken at face value when shown by a woman, while seen as bias when shown by a man (see also Ni and Huo, 2018). As members of one’s own group are often assumed to have positive intent toward the ingroup (Hornsey et al., 2002; Hornsey and Imani, 2004), these expressions may remain unchallenged and not counter argued by the self, and in this way affect self-evaluations and well-being (Barreto and Ellemers, 2005; Sterk et al., 2018; c.f., Ni and Huo, 2018)1. Thus, while self-group distancing can allow leaders who are members of stigmatized groups to cope with experienced threats, it may increase negative consequences for subordinates coming up in the ranks.

Other work has shown that distancing behaviors may have more general negative effects for addressing workplace equality. While members of stigmatized groups are unlikely to see self-group distancing behavior as bias, it is even less likely that members of the dominant group will do so. People tend to believe that representatives of groups have their groups’ interests at heart (Sutton et al., 2006) – and thus members of stigmatized groups expressing stereotypical views of their own group (e.g., as having lower abilities or being less committed), or denying the existence of discrimination against their group, may be perceived as presenting the objective truth as to the current degree of inequality. This has important ramifications, as members of dominant groups can play a valuable role in addressing workplace inequality. Hence, an important avenue for future research is to examine to what extent members of non-stigmatized groups indeed start to believe inequality is less of a problem when successful members of stigmatized groups (e.g., female leaders) deny the existence of discrimination and express negative stereotypes of their own group.

Also in other ways, distancing has costs for the organization at large: members of stigmatized groups trying to hide, fit in, and assimilate into the organizational context undermines the organization’s potential to profit from diversity (e.g., see Ellemers and Rink, 2016). Again then, distancing from the group – like other responses to threat such as exiting when one feels low fit – reduces the likelihood that organizations will actually change to become more welcoming to members of stigmatized groups. While distancing behaviors result from social inequality, they can then also contribute to the maintenance of workplace inequality.

Cognitive and Emotional Depletion

A third set of potential costs of coping with stigma is cognitive and emotional costs for the individual. As described earlier, coping with threat can at first boost energy and resources: individuals often try extra hard to overcome stereotypes and recruit extra resources to do so (Hoyt and Blascovich, 2007, 2010; Ståhl et al., 2012a). In fact, the prevention focus or vigilance that accompanies stereotype threat may be especially useful to recruit such resources (Seibt and Förster, 2004; Koch et al., 2008, 2009; Ståhl et al., 2012b; see also van Peer et al., 2007; Putman and Roelofs, 2011) and to more effectively differentiate (and thus choose) between signals and environments offering threat versus safety (Seligman, 1971; Öhman and Mineka, 2001; Ståhl et al., 2012b). However, coping with workplace stigma has many aspects: constant vigilance for threat, especially among those highly identified with their stigmatized group (Begeny and Huo, 2017, 2018); managing and suppressing stereotype-relevant thoughts and feelings; effectively negotiating threatening contexts; choosing to confront or not confront bias; avoiding mistakes and the confirmation of group-relevant stereotypes; and more generally regulating threat (emotional coping, accepting, or resisting). To some degree, targets can become better at – and habituated to – responding to stigma, such that those who have more frequent experiences and practice dealing with stigma become better at doing so and suffer fewer cognitive costs (Crisp et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 2010). Nevertheless, all of these aspects take cognitive and emotional energy and can eventually lead to exhaustion (e.g., Schmader and Johns, 2003; Johns et al., 2008; Logel et al., 2009; Ståhl et al., 2012a; Hall et al., 2015; c.f., Baumeister et al., 1998; Muraven and Baumeister, 2000). Research has shown that this exhaustion has negative consequences for later similar tasks as well as for other domains (e.g., reducing regulation of learning behaviors, lowering persistence on physical tasks, and increasing unhealthy eating behavior – for an overview, see Schmader et al., 2008; Inzlicht et al., 2011; Ståhl et al., 2012a).

Conclusions Regarding Potential Hidden Costs of Coping With Stigma in the Workplace

In summary then, while we know individuals have various creative strategies available to cope with negative stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination, the regulation involved can take a significant toll. Members of negatively stereotyped groups face not only the usual workplace task demands but also juggle regulation of stigma with all its consequences. This regulation includes complex choices about whether to confront or not confront injustice and whether to display or hide one’s identity – staying with or distancing from the stigmatized group. Moreover, regulation strategies successful for the individual may have unintended negative consequences for other group members. Also, regulating threat may have its own consequences – including cognitive depletion and emotional exhaustion, potentially leading to less effective functioning over time. This can have serious consequences for the self, the organization, and the ironic reinforcement of the stereotypes that caused the initial depletion and exhaustion. Fatigue from daily management of such issues may lead members of negatively stereotyped groups to opt out: leaving contexts and domains in which they are stigmatized and entering domains where they face fewer such challenges (Crocker et al., 1998; Ryan et al., 2008; Stephens and Levine, 2011; Kossek et al., 2016). Crucially, these phenomena are unlikely to be recognized as responses to identity threat and may instead be seen as individual problems and “choices” (Ryan et al., 2008; Stephens and Levine, 2011). Also, even if each specific cost were to be small, they can build up and accumulate. Important future research directions thus include obtaining a much greater understanding of these cumulative costs of facing stigma (for examples see, Pascoe and Smart Richman, 2009; Kogan et al., 2015; Van Dijk and van Engen, 2019).

Implications for Organizations

A threat, support, and hidden costs approach to targets’ responses to stigma helps us understand why current workplace diversity efforts that tend to focus on either “fixing the perpetrator” (e.g., anti-bias training) or “fixing the victim” (mentoring programs etc.) are not always successful in attracting and retaining members of stigmatized groups, and provides insights as to how we can more effectively reduce workplace inequality. A fixing the perpetrator or victim approach is much too simple of an understanding that ignores much of the complex human cognition and behavior through which in- and exclusion takes place. As reviewed here, processes of in- and exclusion include inadvertent automatic stereotypes and biases and subtle devaluations. These are harder to identity but potentially even more potent. A fixing the perpetrator or victim approach tends to look for sources within individuals rather than in the larger work environment or interaction between individuals. A threat, support, and hidden costs approach to targets’ responses to stigma helps us understand why members of negatively stereotyped groups may experience higher levels of stress, depletion, and burn out in organizations; may underperform or appear less committed or motivated; and may not always take available opportunities. These responses should be understood not as dysfunctional responses – or as inherent group differences – but as consequences of the regulation of identity threat in efforts to maintain multiple and sometimes conflicting goals for esteem, belonging, and achievement. This regulation can also entail important, but less obvious hidden costs. Extra vigilance for stigma may mean members of stigmatized groups recruit extra resources and perform well or even excellently in the short run. However, they may also show cognitive depletion and exhaustion over time. Similarly, moving up on the organizational ladder importantly benefits enhancement of self, but may leave members of negatively stereotyped groups as loners in predominantly outgroup organizations much in need of identity safety and ingroup support, or may lead them to distance themselves from other members of their group in an attempt to fit in, leaving the status quo unchanged and the benefits of diversity for organizations uncultivated.

Key in this focus on threats, coping, support, and hidden costs is also that this approach considers members of stigmatized groups not as passive recipients of negative stereotypes and bias, but as active individuals pursuing multiple goals for esteem, belonging, and achievement. This approach is thus part of a shift away from a perspective on members of majority groups as perpetrators and members of stigmatized groups as victims, to a social psychology of intergroup relations that examines the interacting role of the high-status dominant group and the low-status stigmatized group within the contexts in which these interactions occur (Ellemers and Barreto, 2015).

Based on the insights described in this paper, a number of specific implications for organizations arise. First, organizations can do more to create awareness: awareness of how sometimes very subtle identity threats occur in work contexts and in daily interactions through underrepresentation, stereotypes, and an emphasis on domains associated with the dominant group. This also includes an awareness of which supportive contextual factors can reduce threat, and the potential hidden costs of regulating negative stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. Such awareness is particularly important among employees who function as gatekeepers in evaluation, selection, and promotion functions and committees, and among people in leadership positions who strongly impact organizational norms, climates, and policies.

Creating awareness should be approached using good state-of-the-art methods, and it is vital for organizations to understand that offered diversity training programs – and diversity initiatives more generally – are not always consistent with the research state-of-the-art and may backfire or actually increase stereotypes (Kalev et al., 2006; Dobbin and Kalev, 2013, 2018; Kaiser et al., 2013; Roberson et al., 2013; Dover et al., 2014; Moss-Racusin et al., 2014; Brady et al., 2015; Kirby et al., 2015; Gündemir and Galinsky, 2017). This is especially the case when such programs emphasize group membership and stereotypical differences; focus on “fixing the faults” of members of stigmatized groups; or when employees who are members of groups currently overrepresented in the organization feel that these efforts find their group at fault or put their group at a disadvantage. Additionally, for programs to be effective, it is important that they provide insight into how potential threats often manifest themselves in subtle ways in daily workplace interactions. Increased awareness of what is actually important in order to address threats, support, and hidden costs for members of stigmatized groups then allows the tackling of the subtle barriers involved. These approaches are often quite different than what is currently common in the organization: for instance, an organizational diversity contact point where employees can notify someone when experiencing discrimination is not likely to pick up on (and hence address) subtle daily devaluation cues. Instead, counteracting such cues involves systematically scanning the workplace for cues in organizational materials, images, policies and advertisements, and in task and position assignments. Also, it means understanding how these cues and stereotypes become salient in the day-to-day workplace – e.g., in interactions between colleagues, and creating attention to this in the organization.

Second, organizations can create better structures and procedures that take into account this knowledge on threat, coping, support, and hidden costs. We know from much research that we cannot get rid of stereotypes easily, but we can set up recruitment, selection, evaluation, and promotion procedures in organizations such that there is less opportunity for stereotypes to affect outcomes. These structures and procedures go against individuals’ inclinations as busy and time-stressed human beings, leaving less opportunity for biases to impact decisions. The diversity literature has extensive guidelines on how to do this, including the monitoring and feedback of diversity progress (e.g., through the organization’s demographic statistics), and ensuring accountability for this progress; the use of more standardized and transparent recruitment, selection, and promotion procedures; and extra efforts to support networks, mentoring, and the availability of role models and supportive career planning for members of stigmatized groups (see e.g., Bias Interrupters for a comprehensive site monitoring and continually updating the best state-of-the-art on structures and procedures to increase diversity at work).