- 1Division of Population and Behavioural Sciences, School of Medicine, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, United Kingdom

- 2Edinburgh Cancer Centre, Western General Hospital, National Health Service Lothian, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Background: Fidelity of implementation (FOI) reflects whether an intervention was implemented in clinical practice according to the originally developed manual and is a key aspect in understanding intervention effectiveness. To illustrate this process of developing a fidelity measure, this study uses the Mini-AFTERc, a brief psychological intervention aimed at managing breast cancer patients’ fear of cancer recurrence, as an example.

Objectives: To illustrate the development of an FOI measure through (1) applying this process to the Mini-AFTERc intervention, by including the design of a scoring system and rating criteria; (2) content validating the FOI measure using thematic framework analysis as a qualitative approach; (3) testing consistency of the FOI measure using interrater reliability.

Methods: The FOI measure was developed, its scoring system modified and the rating criteria defined. Thematic framework analysis was conducted to content validate the FOI measure using nine intervention discussions between four specialist cancer nurses and four breast cancer patients, and one simulated breast cancer patient. Intraclass-correlation was conducted to assess interrater reliability.

Results: The qualitative findings suggested that the Mini-AFTERc FOI measure has content validity as it was able to measure all five components of the Mini-AFTERc intervention. The interrater reliability suggested a moderate to excellent degree of reliability among three raters, rICC = 0.84, 95% CI [0.51, 0.96].

Conclusion: The study has illustrated the steps that an FOI measure can be developed through a systematic approach applied to the Mini-AFTERc intervention. The FOI measure was found to have content validity and was consistently applied, independently, by three researchers familiar with the Mini-AFTERc intervention. Future studies should determine whether similar levels of interrater reliability can be obtained by distributing written and/or video instructions to researchers who are unfamiliar with the FOI measure, using a larger sample. Employing developed and validated FOI measures such as the one presented for the Mini-AFTERc would facilitate implementation of interventions in the FCR field in clinical practice as intended.

Clinical Trial Registration: www.ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier: NCT03763825.

Introduction

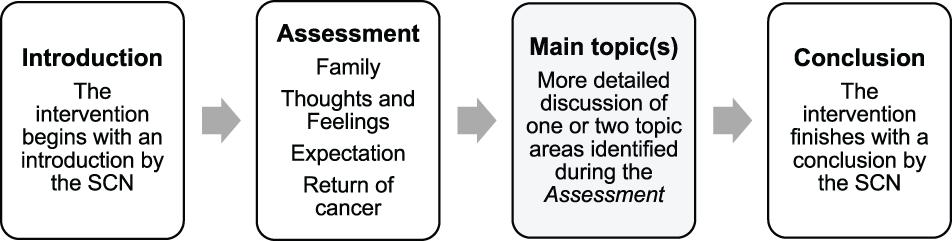

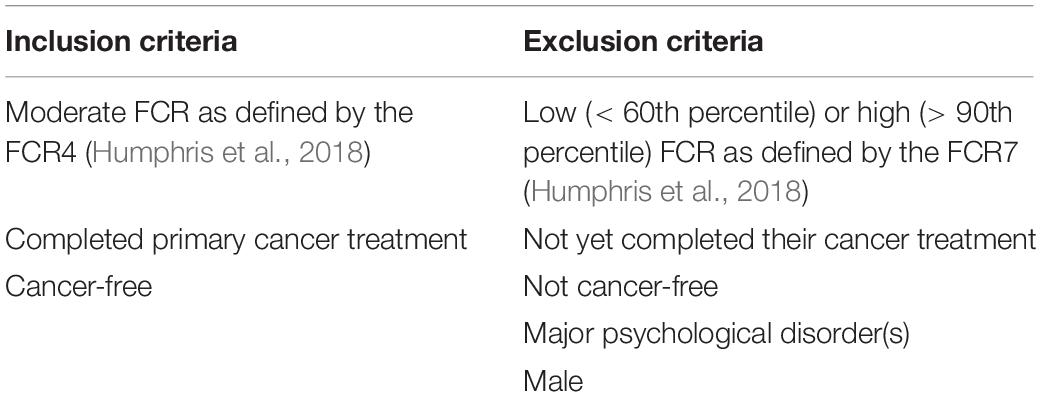

Fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) is the “Fear, worry, or concern about cancer returning or progressing” (Lebel et al., 2016, p. 3267). FCR is a common issue that up to 97% of cancer survivors experience and, importantly, 22–87% of cancer survivors reported experiencing moderate to high FCR levels (Simard et al., 2013). The level of FCR has been associated with the time since primary surgery, the type of surgery and treatment, having symptoms of pain, fatigue, unmet needs, and age (Simard et al., 2013). This paper focused on the Mini-AFTERc intervention which aims to support breast cancer survivors in the management of FCR and was developed for patients experiencing moderate FCR levels (Davidson et al., 2018; McHale et al., 2020). This intervention is based on the cognitive-behavioral therapy approach of Leventhal’s Self-Regulatory Model (Leventhal et al., 1984). Its purpose is to normalize breast cancer patients’ fears and concerns by addressing the primary causes of these fears (Lee-Jones et al., 1997; Davidson et al., 2018; McHale et al., 2020). The intervention consists of 5 key components: Assessment, Family, Thoughts and Feelings, Expectation, and Return of cancer (AFTERc; Figure 1). The Mini-AFTERc is a structured 30 min counseling intervention, which is designed to be delivered during a single telephone conversation led by a specialist cancer nurse (SCN), who has undertaken an intervention training course and has been provided with the intervention manual.

Fidelity of implementation (FOI), also referred to as fidelity of delivery, is an important yet understudied aspect of psychological interventions. FOI has been defined as the extent to which an intervention was delivered as intended, such that the manual originally developed was adhered to, and the critical components of the intervention were present (Orwin, 2000; Century et al., 2010). FOI helps to establish internal and construct validity by providing evidence for the extent to which the implementation of the intervention followed the intervention manual (Stains and Vickrey, 2017). Additionally, FOI contributes to the establishment of external validity by increasing credibility and confidence of scientific findings for practitioners and policymakers, and aids a better understanding of what constitutes an effective intervention (Borrelli, 2011; Brownson et al., 2017). As such, conclusive statements about intervention effects cannot be made without an assessment of FOI (Borrelli, 2011).

Measuring FOI enables researchers to confirm what exactly has been implemented and worked, and hence what can be replicated by research (Nelson et al., 2012). It also aids in identifying aspects of the intervention that were implemented poorly, which may guide future improvements (Nelson et al., 2012). Meta-analyses summarizing over 600 intervention studies targeting mental and physical health, highlighted that higher levels of intervention fidelity were associated with better treatment outcomes (Durlak and DuPre, 2008; Saini, 2009). These findings demonstrated that studies using structured intervention manuals and assessing FOI produced larger effect sizes than studies that did not.

Previous studies that have developed structured psychological interventions for FCR do not robustly or consistently address FOI using evidence-based measures (Lebel et al., 2014; Dodds et al., 2015; Dieng et al., 2016; Butow et al., 2017; van de Wal et al., 2017; Tomei et al., 2018). For example, the SWORD study by van de Wal et al. (2017) used a checklist for a group cognitive behavioral therapy for depression (Hepner et al., 2011), which was not developed specifically for the SWORD intervention. This checklist was developed for the Building Recovery by Improving Goals, Habits, and Thoughts (BRIGHT) and BRIGHT-2 interventions (Hepner et al., 2011). It is unclear to what extent this checklist is relevant and representative of the blended cognitive behavior therapy of the SWORD study, and whether it had been tested previously to ensure content validity. Furthermore, some of these studies do not report how FOI assessments were used to draw conclusions about the intervention, such that they have not been linked to the intervention’s effectiveness. A further example is the ConquerFear study by Butow et al. (2017) which reported that clinicians completed session checklists to ensure fidelity. Additionally, a random 11% of audio recorded intervention sessions was reviewed independently by one of the study team (a clinical psychologist) and feedback was provided to clinicians where non-fidelity was identified. The authors do not report any intra-rater reliability and it is unclear whether the checklist included the core components of the intervention.

Considering the importance of assessing FOI for the robust development and implementation of psychological interventions, it is essential to consistently test and improve fidelity with which current interventions are implemented in clinical practice. As existing measures of fidelity are often generalized to allow the assessment of intervention implementation across a variety of settings and interventions (Breitenstein et al., 2010), they are not always applicable to the intervention being studied. At present, a specific measure to assess FOI of the Mini-AFTERc intervention does not exist and thus necessitates development and testing.

The AFTER intervention (Humphris and Ozakinci, 2008), on which the Mini-AFTERc was based, stressed the need to attend to the therapeutic alliance. Experience of applying this intervention in clinical practice demonstrated that users of the intervention aspired greater flexibility to follow issues that transpired in the patient interaction. Additionally, it increased the chances of the interventionist to provide acknowledgment to patient difficulties and empathize with emotional expressions. Therapeutic alliance can be defined as the collaborative and affective relationship between the therapist and patient (Bordin, 1994; Luborsky, 1994). The therapeutic alliance is regarded to be the most significant aspect in attaining positive therapeutic change (Paul and Charura, 2014). Accordingly, it is important that the interventionist understands the principles of therapeutic alliance to facilitate a strong therapeutic relationship with their client (Paul and Charura, 2014). Earlier meta-analyses including 573 studies concerning youth and adult psychotherapy demonstrated a moderate but reliable link between good therapeutic alliance and positive intervention outcome (Shirk and Karver, 2003; Karver et al., 2006; Horvath et al., 2011; Shirk et al., 2011; Flückiger et al., 2018). Furthermore, a review by Ackerman and Hilsenroth (2003) including 25 studies investigated the type of therapist characteristics and techniques that positively impact on therapeutic alliance. They reported that personal attributes such as being warm and interested, and therapist techniques such as exploration and reflection, impact positively on therapeutic alliance (Ackerman and Hilsenroth, 2003). Therefore, these aspects should be considered when rating the level of fidelity for the Mini-AFTERc intervention and possibly any intervention involved with modifying FCR levels.

Assessing FOI is essential to draw correct conclusions about the effectiveness of the Mini-AFTERc intervention (Borrelli, 2011). It allows researchers to verify that the therapeutic approach used by the SCNs during the intervention represents the defined intervention, and aids in establishing internal, construct, and external validity (Borrelli, 2011; Brownson et al., 2017; Stains and Vickrey, 2017). Particularly, as there is continued work to develop the Mini-AFTERc intervention, close attention is required to devise a bespoke measure for a major trial. Therefore, a comprehensive FOI measure representing the flexibility of the Mini-AFTERc intervention should be developed. Importantly, when defining the rating criteria, therapeutic alliance should be considered (Ackerman and Hilsenroth, 2003). Lastly, interrater reliability of the novel FOI measure, which reflects the variation among two or more raters who measure the same groups of participants, should be established to allow its use in research or clinical applications (Koo and Li, 2016).

This study aimed to develop a comprehensive FOI measure for the Mini-AFTERc intervention and act as an example to other investigators wishing to assess the effectiveness of their interventions in the FCR field. The development of the FOI measure included the design of an unambiguous scoring system and rating criteria to categorize the level of fidelity, providing researchers with a standardized way to quantify how closely the SCNs adhered to the Mini-AFTERc intervention manual. The study objectives were to:

1. Develop a Mini-AFTERc FOI measure, including the design of a scoring system and rating criteria;

2. Content validate the Mini-AFTERc FOI measure using thematic framework analysis as a qualitative approach;

3. Test the consistency of the Mini-AFTERc FOI measure using interrater reliability.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The qualitative study described in this paper was part of the Mini-AFTERc pilot trial (McHale et al., 2020). Thematic framework analysis was employed using an essentialist/realist approach (Terry et al., 2017) to address the study objectives. Thematic framework analysis was chosen due to its flexibility, as it can be used within most theoretical frameworks (Terry et al., 2017).

Study Objective 1: Development of the Mini-AFTERc FOI Measure, Including the Design of a Scoring System and Rating Criteria

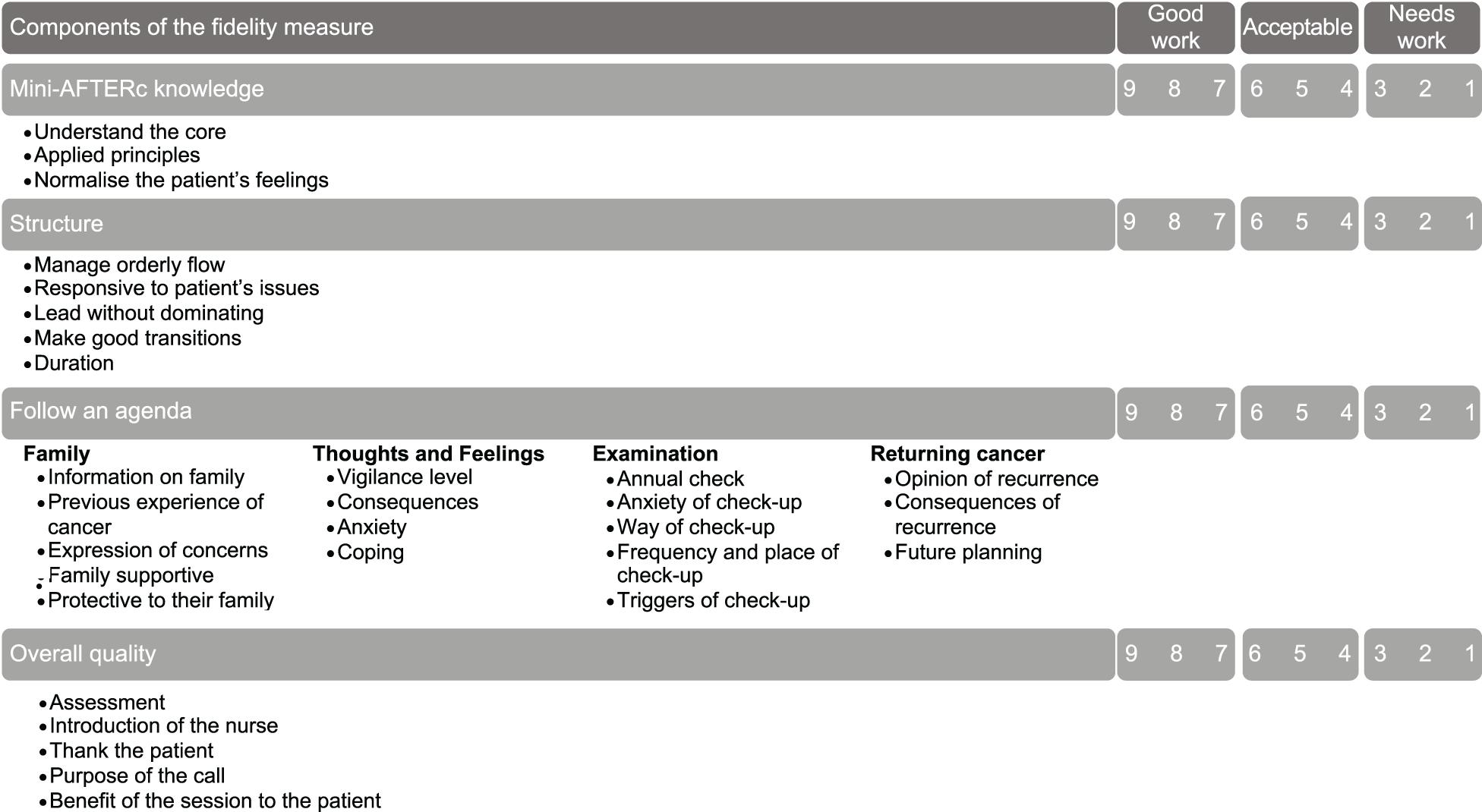

The FOI Rating System, designed by Forgatch et al. (2005), was used to inform the development of an initial version of the Mini-AFTERc FOI measure (Figure 2). This rating system was selected because it was developed to evaluate the fidelity of a manualized theory-based interventions through audio-visual recordings of the intervention being delivered, which fit well with the Mini-AFTERc pilot study protocol (Forgatch et al., 2005). Initial testing of the FOI measure with a small sample of audio recorded Mini-AFTERc intervention telephone calls, collected as part of a feasibility study (Davidson et al., 2018), highlighted that clarification and refinement of content, scoring, and rating was necessary.

Identification of Components

The current iteration of the FOI measure, presented in this paper, was developed by the first author (NGB). After studying the Mini-AFTERc intervention training manual and the initial FOI measure, NGB identified that, while the FOI measure addressed some fundamental aspects of the intervention, including Mini-AFTERc knowledge, structure, follow an agenda, and overall quality, it did not address the separate four core components: Family, Thoughts and Feelings, Expectation, and Return of cancer. Missing, or lacking details, of these essential components leads to an inability to address the intervention’s flexibility and comprehensiveness, thus limiting the ability to assess properly the intervention’s FOI. Hence, to allow the development of a comprehensive FOI measure specifically designed for the Mini-AFTERc intervention, the core components must be addressed separately to enable accurate scoring and rating.

Scoring of the Mini-AFTERc FOI Measure

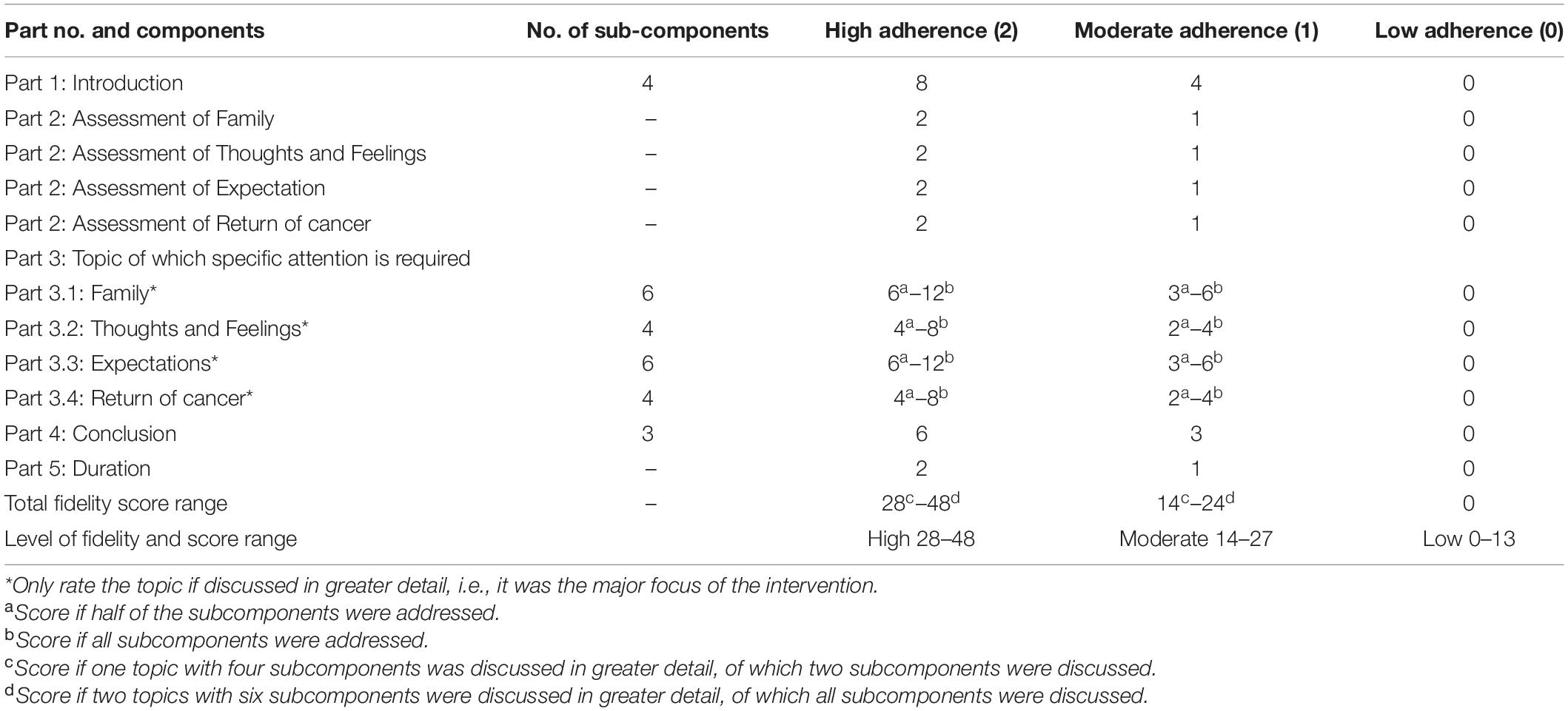

The initial development of the FOI measure included a 9-point scoring system (Figure 2) which NGB redesigned to a 3-point scale. This 3-point scale of adherence was designed to reduce the ambiguity of the scoring process and allow raters to employ their discriminative abilities (Jacoby and Matell, 1971), reducing the possibility of introducing error. The possible adherences scores are as follows: (2) high adherence, (1) moderate adherence, and (0) low adherence. Adherence is defined as whether “a program service or intervention is being delivered as it was designed or written” (Mihalic, 2004, p. 2).

The intervention manual instructs that it is not feasible, within the allotted 30 min, to cover all four core intervention discussion topics in extensive detail. If it is apparent that a patient has potential issues in all four topics, the SCN should prioritize two topics and potentially offer another session. Therefore, the scoring system was designed with the expectation that only one to two core discussion topics would be the major focus of discussion during the intervention. At least half of the subcomponents must be addressed for a topic to be identified as a major focus of the intervention discussion. During the major topic discussion phase, at least half of the subcomponents had to be explicitly addressed by the SCN in at least one major discussion topic for “high adherence” to be scored, providing the SCN scored “high adherence” for all components. To reduce the possibility of scoring unfairly and/or inaccurately, high fidelity could be achieved regardless of whether half of the subcomponents of one main topic were addressed, or all subcomponents of two main topics (Table 1; parts 3.1–3.4).

Rating Criteria of the Mini-AFTERc FOI Measure

The decision to rate adherence as high (2) or moderate (1) was informed by principles positively contributing to therapeutic alliance (Ackerman and Hilsenroth, 2003; Table 2 and Supplementary File 1 for full principle definitions). If the SCN displayed personal attributes and used therapist techniques during the intervention (Table 2), the SCN should receive a rating indicating high adherence (2); otherwise, they should receive a rating indicating moderate adherence (1). Additionally, if the SCN did not consider the intervention’s flexibility, they should receive a rating indicating moderate adherence (1); this includes adhering too strictly to the manual and not considering possible issues that had been shared previously in the interaction by the patient. A rating of 0 should be attributed to a component that is not addressed.

The researcher should rate the duration as 2 if it was within the limits of 25–35 min, 1 if it was between 20–25 and 35–40 min, and 0 if it was below 20 min or above 40 min. These limits were discussed and agreed on by the three researchers involved in this study, as duration is a key component in the design of the intervention. Lastly, no negative points should be given for flexibility; when rating the main topic of the intervention, points should be given for any subcomponents of the main topic already discussed during the Assessment process.

Study Objective 2: Content Validate the Mini-AFTERc FOI Measure Using Thematic Framework Analysis

This FOI measure was tested by qualitatively analyzing the audio-recordings of the intervention discussions using thematic framework analysis (Terry et al., 2017).

Participants

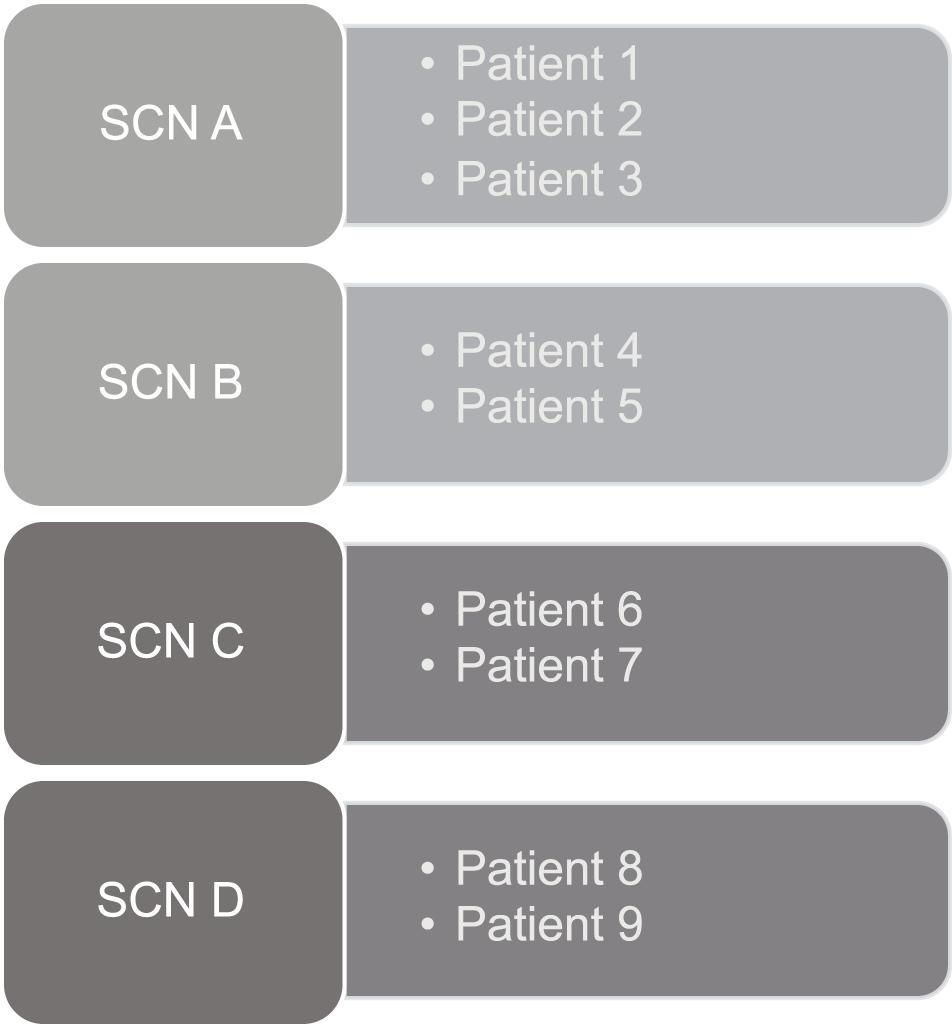

A convenience sample of nine audio-recorded Mini-AFTERc intervention discussions was used to test the FOI measure. Four SCNs (A-D) from two breast cancer centers in National Health Service (NHS) Scotland, five breast cancer patients and one simulated breast cancer patient produced these nine intervention discussions. SCN A and B held the intervention with breast cancer patients 1–5. SCN C and D held the intervention with one simulated breast cancer patient, who acted out four different patient roles, resulting in breast cancer patients 6–9 (Table 3 and Figure 3). The simulated breast cancer patient was a volunteer actor who works regularly with the School of Medicine at the University of St Andrews to facilitate practical and communication training with medical students. They assumed the persona of several FCR case studies, developed by GMH based on previous real clinical cases. Nine participants were chosen as this study sought sufficient complexity in the transcripts of intervention discussions to ensure all aspects of the FOI measure could be tested.

Data Collection

The Mini-AFTERc intervention was delivered through one single telephone conversation between SCNs and NHS breast cancer patients. Additionally, four simulated telephone conversation between SCNs and the simulated breast cancer patient were recorded as part of SCNs training for the Mini-AFTERc pilot trial (McHale et al., 2020). All SCNs and NHS breast cancer patients were consented to participate. The conversations were audio-recorded using Tascam DR-05X, resulting in good audio quality. Audio-recordings were brought to the School of Medicine, University of St Andrews for storage and analysis. The data from all SCNs were included to ensure the level of fidelity was not due to a specific therapist technique used by one SCN.

Thematic Framework Analysis

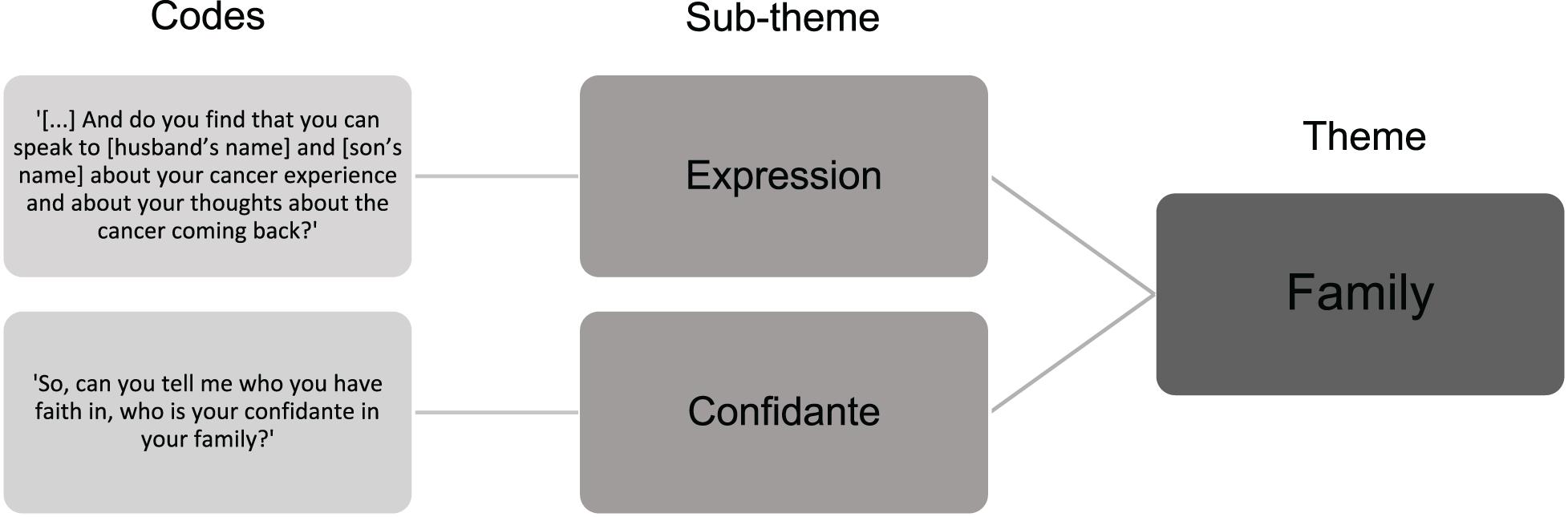

Given that clearly defined themes already exist in the Mini-AFTERc intervention (Figure 1), a deductive, analyst-driven approach was used. This approach allows existing theoretical concepts to be brought in that provide a basis for “seeing” the data (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2012). As the intervention’s components were discussed explicitly and implicitly, the data was approached semantically and latently (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2012). All nine audio-recorded intervention discussions were transcribed verbatim (total duration = 254.04 min). The author reviewed the transcripts against the audio-recordings several times to ensure accuracy and correct potential mistakes (Terry et al., 2017). To test the FOI measure, the transcripts were analyzed according to the thematic analysis principles outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). This process involved familiarization with the data, such as transcribing the audio-recordings, reading and re-reading through the transcripts and taking initial notes. Data coding was completed by highlighting particular sentences or phrases in different colors to represent different codes. Lastly, the different codes were sorted into the relevant, clearly defined sub-themes and themes of the Mini-AFTERc intervention (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Example of codes sorted into the relevant sub-theme and theme of the Mini-AFTERc intervention.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for this study was granted for the Mini-AFTERc pilot trial by the NHS Research Ethics Committee (18/SS/0135) and the University of St Andrews Teaching and Research Ethics Committee (MD14241). All nurse and patient participants provided written consent to participate. Ethical issues were considered by removing all identifiable information from the transcripts, including patients’ names, family’s or friends’ names, and names of locations, places, or organizations.

Study Objective 3: Testing the Consistency of the Mini-AFTERc FOI Measure Using Interrater Reliability

NGB listened to the audio-recordings available and read verbatim transcripts; two researchers, who are considered experts of the Mini-AFTERc intervention (originator and feasibility investigator: GMH and CTM, respectively) read verbatim transcripts to rate the SCNs’ adherence to the intervention manual independently of each other.

Interrater reliability analysis was performed by NGB on nine transcripts using intraclass correlation on IBM SPSS Version 24 on macOS Mojave Version 10.14.1. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) estimates and their 95% confident intervals (CI) were calculated based on mean-rating (k = 3; k is the number of raters), consistency, and a two-way mixed-effects model, for the total fidelity score of each of the nine transcripts. Interpretation was as follows: < 0.50, poor; 0.50–0.75, moderate; 0.75–0.90 good; > 0.90, excellent (Koo and Li, 2016; Perinetti, 2018).

Results

Study Objective 1: Development of the Mini-AFTERc FOI Measure, Including the Design of a Scoring System and Rating Criteria

See Supplementary File 2 for the full FOI measure. A description of the development process can be found in “Materials and Methods” section of this paper.

Study Objective 2: Content Validating the Mini-AFTERc FOI Measure Using Thematic Framework Analysis

The nine analyzed conversations lasted between 12:42 and 45:20 min (M = 28:18 min, SD = 9.00). The average total fidelity score across all evaluated intervention discussions was 27 (range: 19–34), reflecting moderate adherence to the intervention manual. The qualitative findings indicated that the Mini-AFTERc FOI measure has content validity as it was able to measure all five components of the Mini-AFTERc intervention: Introduction, assessment, main topic(s), conclusion, and duration. Additionally, the subject matter experts, GMH and CTM, judged the contents of the FOI measure to be relevant and representative to those of the Mini-AFTERc intervention. The qualitative findings including examples of, and explanations for, FOI ratings are presented in the following sections.

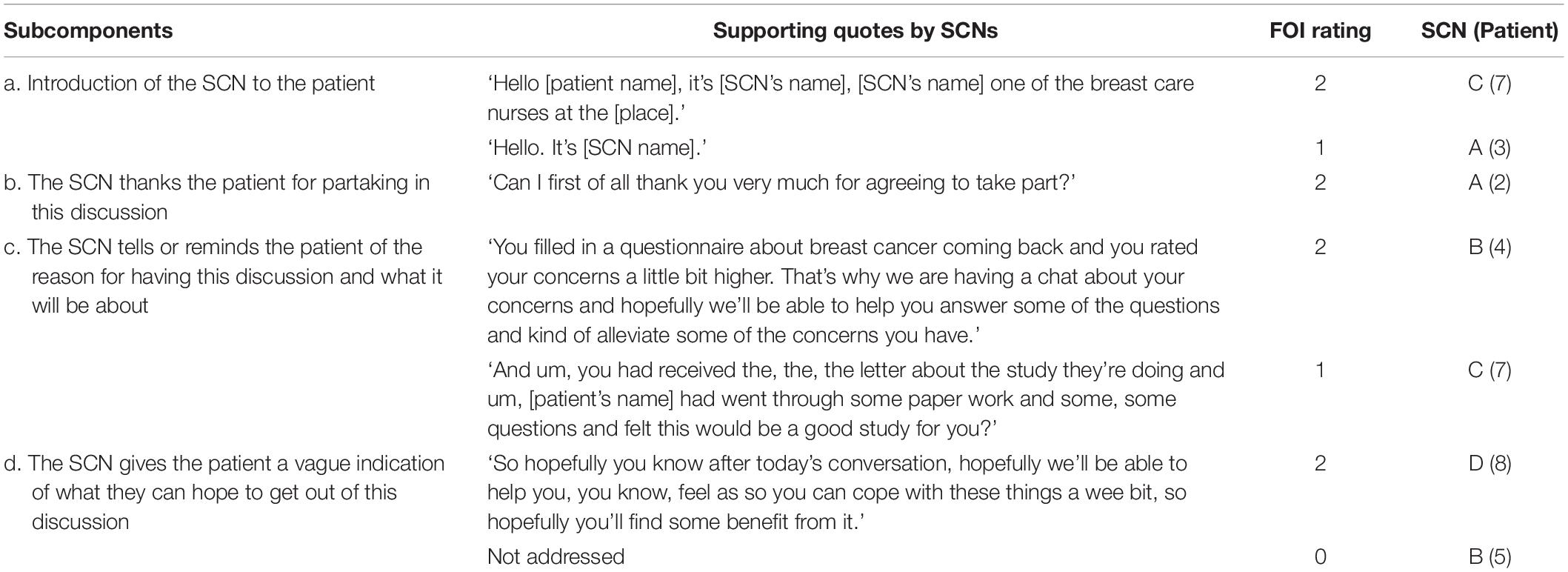

Introduction (Setting the Scene)

The total fidelity score ranged between 3 and 7 among SCNs out of a possible 8. SCND held two interventions and was rated above average, as they exhibited personal attributes such as being warm, friendly, and supportive (Table 4). In contrast, SCNC held two interventions but did not receive a score above average, mostly because they did not address subcomponents b and d in both interventions held, which led to a rating of 0 for both. Additionally, SCNC received a rating of 1 for subcomponent c, as it was unclear what questions they were referring to, and what the intervention will be about (Table 4).

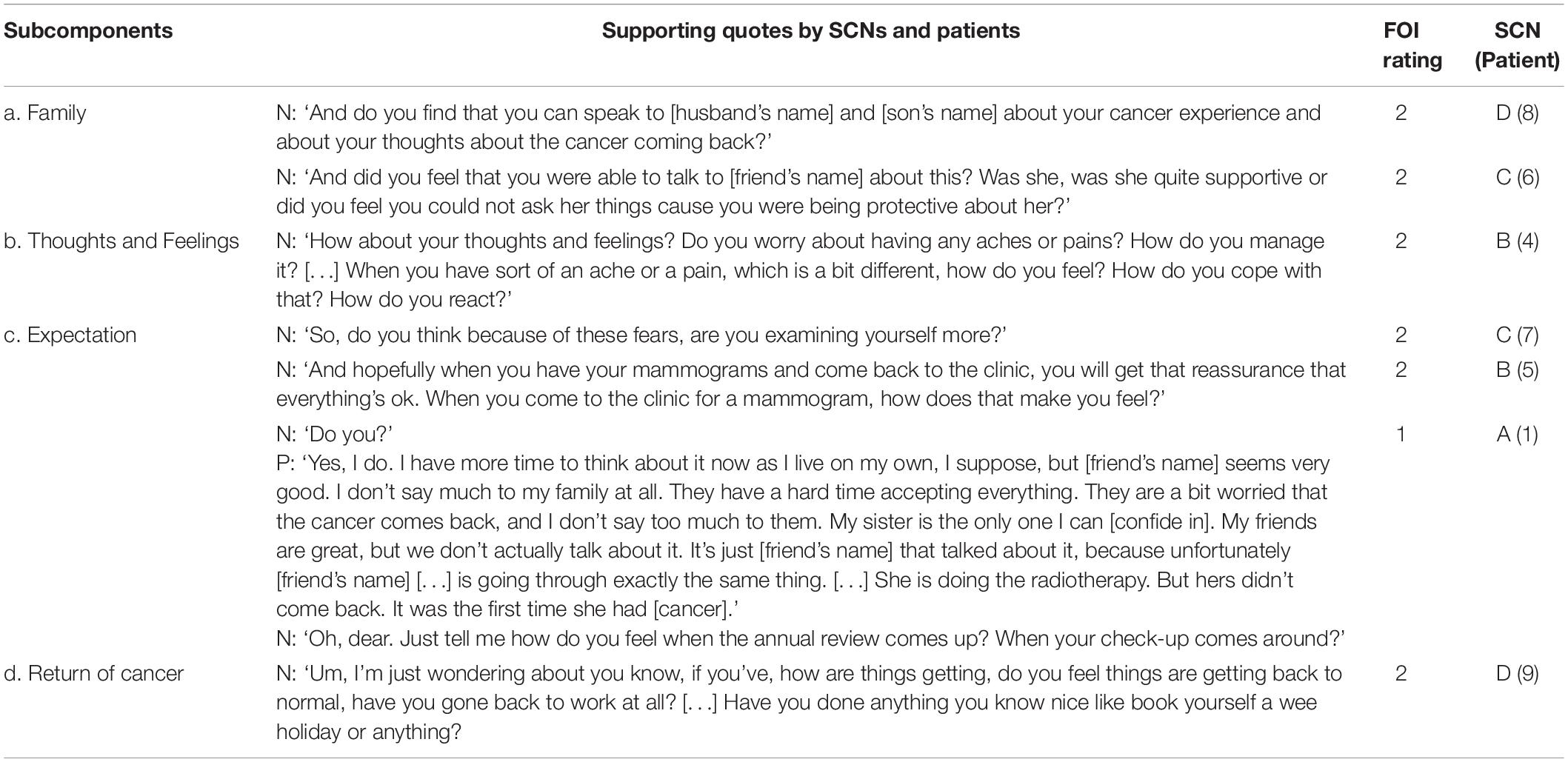

Assessment of Which Topics Require Detailed Discussion

The SCNs’ total fidelity score ranged between 4 and 8 out of a possible 8. As SCNA had technical difficulties with the tape recording, they received an average total fidelity score of 4. All SCNs exhibited personal attributes and used therapist techniques (e.g., reflection; Table 5) essential for therapeutic alliance. For example, SCNC used therapist techniques, such as exploration and facilitating the expression of affect, which reflects their high score (Table 5, a). In contrast, SCNA did not attend to the patient’s experience, which reflects their moderate score (Table 5, c).

Topic of Which Specific Attention Is Required

Each of the four components that form the main part of the intervention were present in the transcripts. The findings are presented in the following subsections.

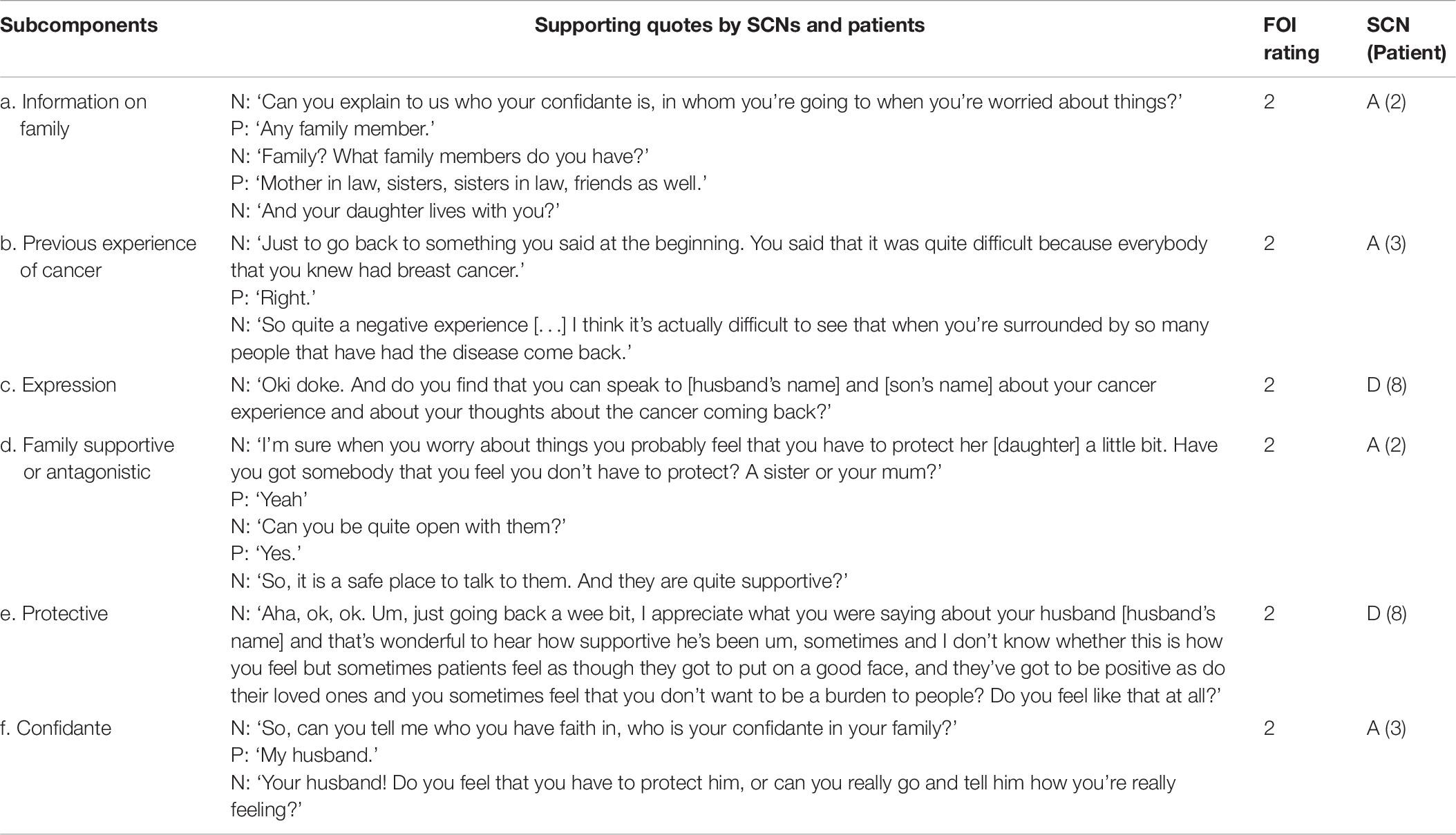

Family

Four interventions held by two SCNs covered this component as the main topic of the intervention. The total fidelity score ranged between 5 and 11 out of a possible 12. SCNs used therapist techniques such as exploration and reflection, and had personal attributes, such as being warm, friendly and interested, which reflect their high scores (Table 6). For example, SCND reflected back the patient’s words to explore whether the patient felt the need to be protective of their family members, whilst being open and interested (Table 6, e).

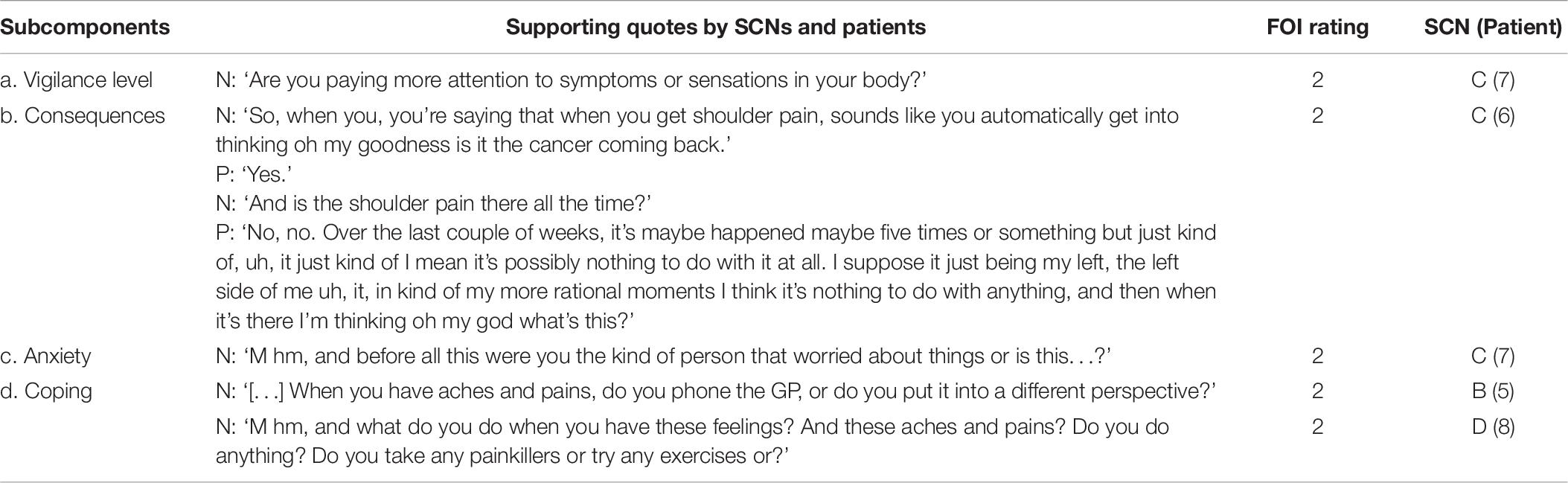

Thoughts and Feelings

Four interventions held by three SCNs covered this component. The total fidelity score ranged between 5 and 8 out of a possible 8. All SCNs had personal attributes, such as being open and flexible, and used therapist techniques such as exploration, attending to the patient’s experience and accurate interpretation during their conversation with the patient, which reflect their high scores (Table 7).

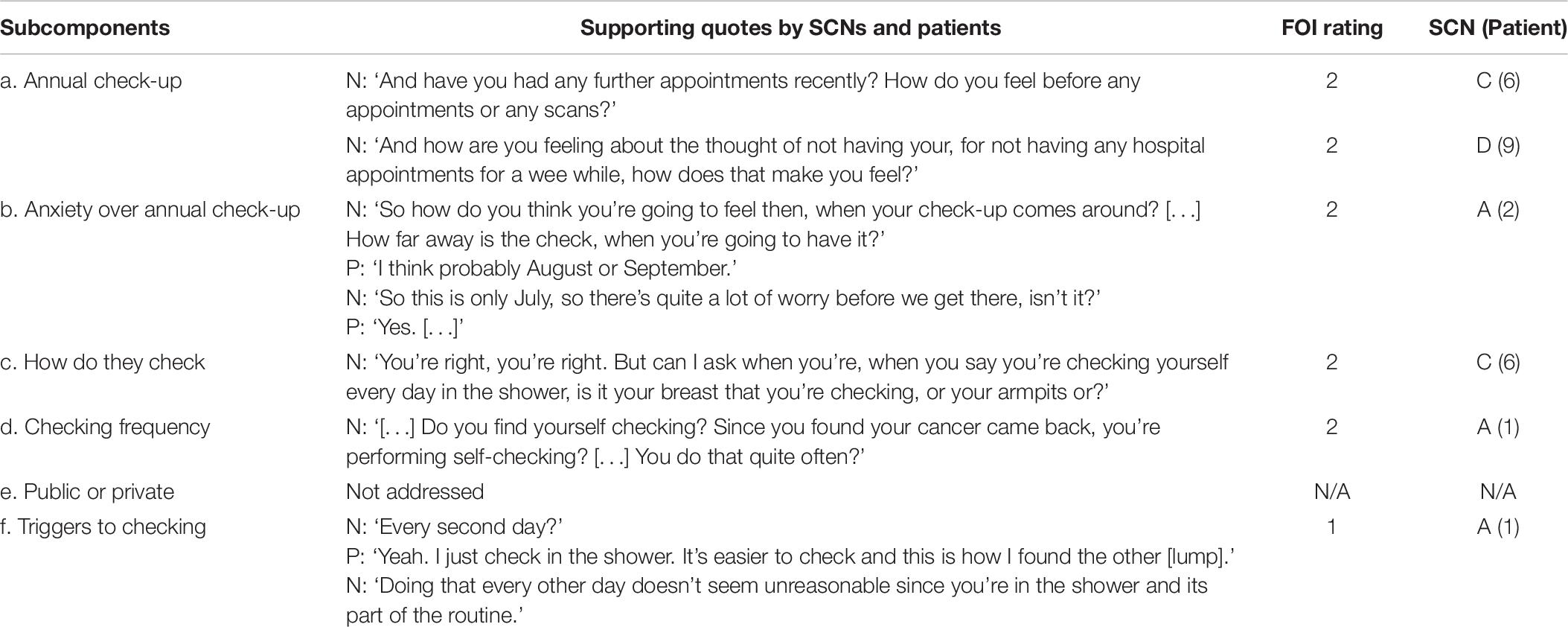

Expectation

Four interventions held by three SCNs covered this component. The total fidelity score ranged between 4 and 8 out of a possible 12. SCNA showed warmth and attended to the patient’s experience, which reflects their high score (Table 8, b). Similar skills were observed for SCNC who demonstrated interest, attended to the patient’s experience and used exploration as a therapist technique (Table 8, c). In contrast, although SCNA accurately interpreted why the patient is checking themselves in the shower, they may have used exploration to further investigate whether there are any specific triggers to checking, which reflects their moderate score (Table 8, f).

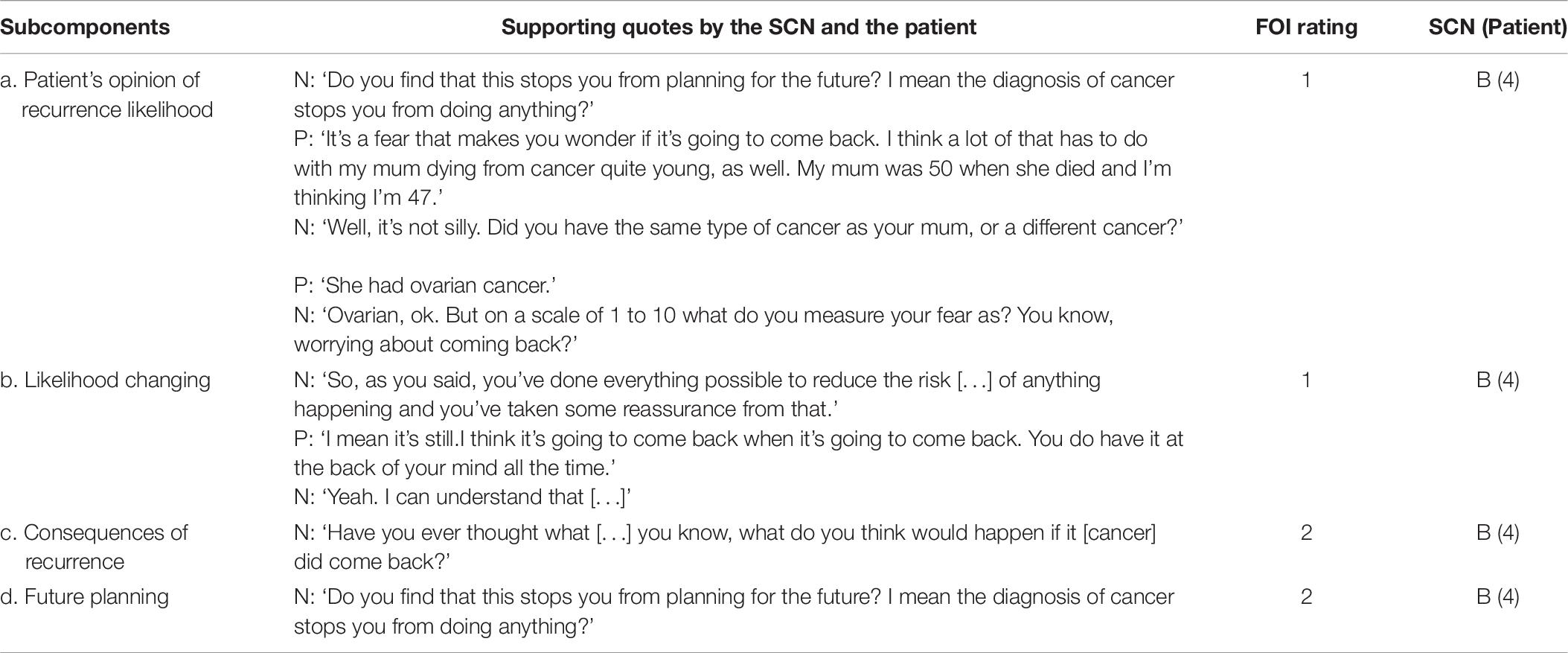

Return of Cancer

One SCN discussed this component as the main topic of the intervention, with a total fidelity score of 6 out of 8. As the SCN addressed subcomponent a without attending to the patient’s experience, they received a rating of 1; although the patient directed the conversation from Return of cancer toward Family, the SCN did not attend to the patient’s experience of their mother dying from cancer and led the conversation back to the main topic Return of cancer (Table 9).

Conclusion

The total fidelity score ranged between 1 and 4 among SCNs out of a possible 6. SCND received a rating of 2, as they showed interest and used exploration as a therapist technique (Table 10, c). In contrast, SCNC received a rating of 1 as they could have been more open and interested in the patient getting a benefit out of the intervention discussion (Table 10, c). Compared to other parts of the intervention, no SCN addressed all three subcomponents of the Conclusion.

Duration

The total fidelity score ranged between 0 and 2 out of a possible 2 among SCNs. SCNA held the intervention with three patients and received different scores for the duration for each of them: 0, 1, and 2, for 12:42 min, 23:31 min, and 27:33 min, respectively. In contrast, SCND held two interventions with a simulated patient and received a score of 2 for both, a duration of 30:10 min and 31:40 min.

Study Objective 3: Testing the Consistency of the Mini-AFTERc FOI Measure Using Interrater Reliability

A moderate to excellent degree of reliability was found among raters, average measure ICC = 0.84, 95% CI [0.51, 0.96]. The full interrater dataset and analysis can be found in Supplementary File 3.

Discussion

This study developed and tested an FOI measure, designed specifically for the Mini-AFTERc intervention to assess and categorize adherence to the intervention manual. The findings indicate that, through the processes of development outlined, this FOI measure is a useful and practical tool to comprehensively assess the delivery of the Mini-AFTERc intervention, that it has content validity, and that it is reliable with the sample used in this study.

Mini-AFTERc FOI Measure: Scoring System and Rating Criteria

The 3-point scoring system was found to be useful in practice, as it allowed researchers to employ their discriminative abilities (Jacoby and Matell, 1971) and reduced the possibility of introducing error. Therefore, the reduced rating scheme from nine to three categories can be considered more precise and accurate compared to complex scoring systems with various response categories. Using therapist principles that positively impact on therapeutic alliance (Ackerman and Hilsenroth, 2003) as rating criteria were instructive and facilitated the rating process, allowing a more accurate distinction to be made between high and moderate adherence. Consequently, these categorical definitions for each rating point may increase consistency among prospective raters who are unfamiliar with this FOI measure.

Content Validating the Mini-AFTERc FOI Measure: Qualitative Findings

The qualitative findings indicated that the Mini-AFTERc FOI measure has content validity as it was able to measure all five components of the Mini-AFTERc intervention: Introduction, assessment, main topic(s), conclusion, and duration. Additionally, the subject matter experts judged the contents of the FOI measure to be relevant and representative to those of the Mini-AFTERc intervention, allowing valid results to be produced. Consequently, the FOI measure’s scores may be used to make important and relevant implications, suggestions, and interpretations, and also allow researchers to link the FOI results to the intervention’s effectiveness and thus draw accurate conclusions. As mentioned previously, existing FCR intervention studies do not consistently address the development and testing of FOI, which may have implications for how the results of these interventions are reported and interpreted (Lebel et al., 2014; Dodds et al., 2015; Dieng et al., 2016; Butow et al., 2017; van de Wal et al., 2017; Tomei et al., 2018). Although many of these studies do employ fidelity assessment tools, they are often not comprehensively described and/or their development and implementation is not addressed. Therefore, it is unclear whether many of these fidelity tools have content validity and whether their results accurately reflect treatment fidelity. This lack of clarity may result in inaccurate application of the fidelity tools, ambiguity regarding the integrity of the tools, and inaccurate conclusions about the efficacy of the intervention. This paper provides a detailed report of how FOI was conceptualized, developed and tested for the Mini-AFTERc intervention to ensure content validity, which may provide a template for future FCR intervention fidelity assessment tools. We propose that the systematic and evidence-based development of an FOI measure, as well as transparent, detailed and replicable reporting of such measures, should be the norm within FCR intervention research, as it is within many other areas of psychological intervention research. We hope that the work detailed in this paper will have a wider impact in that it will provide a rigorous methodological and analytical template for other researchers seeking to develop bespoke fidelity measures of healthcare communication interventions. Such practices would improve clarity, reduce bias and inform and facilitate improved FOI tool development. Most importantly, robust FOI development and assessment may lead to the refinement of FCR interventions and ensure their effectiveness for clinicians and patients.

Testing the Consistency of the Mini-AFTERc FOI Measure Using Interrater Reliability

The results indicate a moderate to excellent consistency among the three raters, as per the classification from Koo and Li (2016). However, there was noticeable total fidelity score variability among raters, which may be attributable to the rating process. NGB listened to the four audio-recordings available to transcribe the data and rate the intervention discussions. In contrast, GMH and CTM rated the intervention discussions using the transcripts only. Research has reported that transcribing spoken data loses information as emotional responses or concrete events are translated into written language; this results in the loss of the fundamentals of natural speech, such as intonation and stress, which increase insights and understanding beyond the explicit content (Markle et al., 2011). As the rating process involved consideration of the principles of therapeutic alliance to differentiate between moderate and high adherence, GMH and CTM may have had less information on which to base and interpret their ratings and scorings of these principles, as opposed to NGB. This may explain some of the scoring variability.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

A strength of the present study is the unambiguity of the 3-point scoring system. This allows raters to employ their discriminative abilities, increases accuracy and limits the possibility of introducing error (Jacoby and Matell, 1971) as opposed to the 9-point scoring system designed during the initial development of this FOI tool. A further strength is the variety of audio-recordings and transcripts, such that each of the core components of the Mini-AFTERc intervention was present at least once in the intervention discussions used in this study. Consequently, this allowed the FOI assessment of all core components of the intervention. Furthermore, definitions and descriptions of the measure, its scoring system, and rating criteria make the application of the FOI measure more accessible. Finally, the moderate to excellent degree of interrater reliability among the three researchers involved in this study will allow the use of the FOI measure in research or clinical applications (Koo and Li, 2016).

A potential limitation to the application of the interrater reliability finding is that the developer of the FOI measure (NGB) was involved in rating the transcripts and provided instructions and explanations face-to-face to the other two raters. Therefore, future research should establish whether similar levels of interrater reliability can be obtained with the use of written and/or video instructions, that could be distributed to researchers who are unfamiliar with the FOI measure. Furthermore, it is commonly accepted that data should be collected from a broad range of participants to obtain accurate estimates of reliability in research. However, the sample of this study was relatively small due to restricted resources. Nevertheless, this study yielded important qualitative and quantitative findings, and future research should consider replicating the current study with a larger sample of patients, SCNs, and raters.

Implications for Research and Practice

The availability of this unambiguous, content validated, and reliable FOI measure will allow confident application by individuals trained on how to employ this FOI measure. This FOI measure will allow researchers and clinicians to recognize what aspects of the Mini-AFTERc intervention work well or require improvement, and thus what aspects to emphasize in training sessions. To reduce the risk of potential liking bias, prospective researchers assessing the intervention’s FOI should be independent and not work directly with the SCNs holding the intervention. Lastly, the approach taken to develop the FOI measure for the Mini-AFTERc intervention may be helpful for other investigators to consider for novel interventions in the FCR field.

Conclusion

This study developed and tested a novel FOI measure that considers the flexibility and comprehensiveness of the Mini-AFTERc intervention. The 3-point scoring system allowed raters to employ their discriminative abilities, thus increasing accuracy. The qualitative findings indicated that the FOI measure was able to assess all of the Mini-AFTERc intervention’s core components, thus indicating that the FOI measure has content validity. The quantitative findings indicated that the FOI measure has a moderate to excellent degree of reliability with the sample used. Future research should determine whether similar levels of interrater reliability can be obtained by distributing written and/or video instructions to researchers who are unfamiliar with the FOI measure, using a larger sample. Researchers trained on using the Mini-AFTERc FOI measure may use it to understand the translation of evidence-based research of the Mini-AFTERc intervention into clinical practice. The procedures outlined provide an example for other interventionists concerned with implementing FCR management programmes.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because full transcripts of Mini-AFTERc intervention discussions, used to test the FOI measure, are potentially identifiable. The data used to calculate interrater reliability are available. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to CTM, Y3RtMkBzdC1hbmRyZXdzLmFjLnVr.

Ethics Statement

This study involved human participants and was reviewed and approved by the NHS South East Scotland Research Ethics Committee 02 (18/SS/0135) and the University of St Andrews Teaching and Research Ethics Committee (MD14241). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

NGB developed the FOI measure, conducted all transcription and data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. CTM and GMH collected the audio recordings. All authors contributed to the interrater reliability scoring and edited and agreed the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted as part of NBG’s MSc in Health Psychology supported by the University of St Andrews. The Mini-AFTERc pilot trial was funded by the Chief Scientist Office (CSO), which is part of the Scottish Government Health Directorates (Reference: HIPS/17/57).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the specialist cancer nurses, patients, and the simulated patient for contributing their time to the generation of the data of this study. Thanks is also due to Maria Kontomichou whose work contributed to the initial development of the Mini-AFTERc FOI measure.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.601813/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

Mini-AFTERc, Assessment Family, Thoughts and Feelings Expectations Return of cancer: Brief intervention; CI, Confidence Interval; FCR, Fear of cancer recurrence; FOI, Fidelity of implementation; ICC, Intraclass correlation coefficient; NHS, National Health Service; SCN, Specialist cancer nurse.

References

Ackerman, S. J., and Hilsenroth, M. J. (2003). A review of therapist characteristics and techniques positively impacting the therapeutic alliance. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 23, 1–33. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00146-0

Bordin, E. S. (1994). “Theory and research on the therapeutic working alliance: new directions,” in The Working Alliance: Theory, Research, and Practice, eds A. O. Horvath and L. S. Greenberg (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons), 13–37.

Borrelli, B. (2011). The assessment, monitoring, and enhancement of treatment fidelity in public health clinical trials. J. Public Health Dent. 71, 52–63.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2012). “Thematic analysis,” in APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol. 2. Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological, eds H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, and K. J. Sher (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 57–71.

Breitenstein, S. M., Gross, D., Garvey, C. A., Hill, C., Fogg, L., and Resnick, B. (2010). Implementation fidelity in community-based interventions. Res. Nurs. Health. 33, 164–173. doi: 10.1002/nur.20373

Brownson, R. C., Colditz, G. A., and Proctor, E. K. (2017). Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Butow, P. N., Turner, J., Gilchrist, J., Sharpe, L., Smith, A. B., Fardell, J. E., et al. (2017). Randomized trial of ConquerFear: a novel, theoretically based psychosocial intervention for fear of cancer recurrence. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 4066–4077. doi: 10.1200/jco.2017.73.1257

Century, J., Rudnick, M., and Freeman, C. (2010). A framework for measuring fidelity of implementation: a foundation for shared language and accumulation of knowledge. Am. J. Eval. 31, 199–218. doi: 10.1177/1098214010366173

Davidson, J., Malloch, M., and Humphris, G. (2018). A single-session intervention (the Mini-AFTERc) for fear of cancer recurrence: a feasibility study. Psychooncology 27, 2668–2670. doi: 10.1002/pon.4724

Dieng, M., Butow, P. N., Costa, D. S., Morton, R. L., Menzies, S. W., Mireskandari, S., et al. (2016). Psychoeducational intervention to reduce fear of cancer recurrence in people at high risk of developing another primary melanoma: results of a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 4405–4414. doi: 10.1200/jco.2016.68.2278

Dodds, S. E., Pace, T. W., Bell, M. L., Fiero, M., Negi, L. T., Raison, C. L., et al. (2015). Feasibility of Cognitively-Based Compassion Training (CBCT) for breast cancer survivors: a randomized, wait list controlled pilot study. Support. Care Cancer 23, 3599–3608. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2888-1

Durlak, J. A., and DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 41, 327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

Flückiger, C., Del Re, A., Wampold, B. E., and Horvath, A. O. (2018). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: a meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy 55, 316–340. doi: 10.1037/pst0000172

Forgatch, M. S., Patterson, G. R., and DeGarmo, D. S. (2005). Evaluating fidelity: predictive validity for a measure of competent adherence to the oregon model of parent management training. Behav. Ther. 36, 3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(05)80049-8

Hepner, K. A., Howard, S., Paddock, S. M., Hunter, S. B., Osilla, K. C., and Watkins, K. E. (2011). A Fidelity Coding Guide for a Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Horvath, A. O., Del Re, A., Flückiger, C., and Symonds, D. (2011). Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy 48, 9–16. doi: 10.1037/a0022186

Humphris, G., and Ozakinci, G. (2008). The AFTER intervention: a structured psychological approach to reduce fears of recurrence in patients with head and neck cancer. Br. J. Health Psychol. 13, 223–230. doi: 10.1348/135910708x283751

Humphris, G. M., Watson, E., Sharpe, M., and Ozakinci, G. (2018). Unidimensional scales for fears of cancer recurrence and their psychometric properties: the FCR4 and FCR7. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 16, 30–41.

Jacoby, J., and Matell, M. S. (1971). Three point Likert scales are good enough. J. Mark. Res. 8, 495–500. doi: 10.2307/3150242

Karver, M. S., Handelsman, J. B., Fields, S., and Bickman, L. (2006). Meta-analysis of therapeutic relationship variables in youth and family therapy: the evidence for different relationship variables in the child and adolescent treatment outcome literature. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 26, 50–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.09.001

Koo, T. K., and Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15, 155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

Lebel, S., Maheu, C., Lefebvre, M., Secord, S., Courbasson, C., Singh, M., et al. (2014). Addressing fear of cancer recurrence among women with cancer: a feasibility and preliminary outcome study. J. Cancer Surviv. 8, 485–496. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0357-3

Lebel, S., Ozakinci, G., Humphris, G., Mutsaers, B., Thewes, B., Prins, J., et al. (2016). From normal response to clinical problem: definition and clinical features of fear of cancer recurrence. Support. Care Cancer 24, 3265–3268. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3272-5

Lee-Jones, C., Humphris, G., Dixon, R., and Hatcher, M. B. (1997). Fear of cancer recurrence—a literature review and proposed cognitive formulation to explain exacerbation of recurrence fears. Psychooncology 6, 95–105. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199706)6:2<95::aid-pon250>3.0.co;2-b

Leventhal, H., Nerenz, D., and Steele, D. (1984). “Illness representations and coping with health threats,” in Handbook of Psychology and Health, Volume IV: Social Psychology Aspects of Health, eds A. Baum, S. E. Taylor, and J. E. Singer (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 219–252. doi: 10.4324/9781003044307-9

Luborsky, L. (1994). “Therapeutic alliances as predictors of psychotherapy outcomes: factors explaining the predictive success,” in The Working Alliance: Theory, Research, and Practice, eds A. O. Horvath and L. S. Greenberg (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons), 38–50.

Markle, D. T., West, R. E., and Rich, P. J. (2011). Beyond transcription: technology, change, and refinement of method. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 12, 1–21.

McHale, C. T., Cruickshank, S., Torrens, C., Armes, J., Fenlon, D., Banks, E., et al. (2020). A controlled pilot trial of a nurse-led intervention (Mini-AFTERc) to manage fear of cancer recurrence in patients affected by breast cancer. Pilot Feasibil. Stud. 6, 60–69.

Mihalic, S. (2004). The importance of implementation fidelity. Emo. Behav. Disorders Youth 4, 83–105.

Nelson, M. C., Cordray, D. S., Hulleman, C. S., Darrow, C. L., and Sommer, E. C. (2012). A procedure for assessing intervention fidelity in experiments testing educational and behavioral interventions. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 39, 374–396. doi: 10.1007/s11414-012-9295-x

Orwin, R. G. (2000). Assessing program fidelity in substance abuse health services research. Addiction 95(Suppl. 3), 309–327. doi: 10.1080/09652140020004250

Paul, S., and Charura, D. (2014). An Introduction to the Therapeutic Relationship in Counselling and Psychotherapy. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Perinetti, G. (2018). StaTips Part IV: selection, interpretation and reporting of the intraclass correlation coefficient. South Eur. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Res. 5, 3–5. doi: 10.5937/sejodr5-17434

Saini, M. (2009). A meta-analysis of the psychological treatment of anger: developing guidelines for evidence-based practice. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 37, 473–488.

Shirk, S. R., and Karver, M. (2003). Prediction of treatment outcome from relationship variables in child and adolescent therapy: a meta-analytic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 71, 452–464. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.452

Shirk, S. R., Karver, M. S., and Brown, R. (2011). The alliance in child and adolescent psychotherapy. Psychotherapy 48, 17–24. doi: 10.1037/a0022181

Simard, S., Thewes, B., Humphris, G., Dixon, M., Hayden, C., Mireskandari, S., et al. (2013). Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J. Cancer Surviv. 7, 300–322. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0272-z

Stains, M., and Vickrey, T. (2017). Fidelity of implementation: an overlooked yet critical construct to establish effectiveness of evidence-based instructional practices. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 16, 1–11.

Terry, G., Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2017). “Thematic analysis,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, eds C. Willig and W. Stainton- Rogers (London: SAGE Publications Ltd), 17–37.

Tomei, C., Lebel, S., Maheu, C., Lefebvre, M., and Harris, C. (2018). Examining the preliminary efficacy of an intervention for fear of cancer recurrence in female cancer survivors: a randomized controlled clinical trial pilot study. Support. Care Cancer 26, 2751–2762. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4097-1

van de Wal, M., Thewes, B., Gielissen, M., Speckens, A., and Prins, J. (2017). Efficacy of blended cognitive behavior therapy for high fear of recurrence in breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors: the SWORD study, a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 2173–2183. doi: 10.1200/jco.2016.70.5301

Keywords: fidelity, implementation, Mini-AFTERc intervention, breast cancer, fear of cancer recurrence

Citation: Brandt NG, McHale CT and Humphris GM (2020) Development and Testing of a Novel Measure to Assess Fidelity of Implementation: Example of the Mini-AFTERc Intervention. Front. Psychol. 11:601813. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.601813

Received: 01 September 2020; Accepted: 02 November 2020;

Published: 25 November 2020.

Edited by:

Elizabeth Grunfeld, Birkbeck University of London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Gregor Weissflog, Leipzig University, GermanyNorbert Schäffeler, Tübingen University Hospital, Germany

Copyright © 2020 Brandt, McHale and Humphris. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Calum Thomas McHale, Y3RtMkBzdC1hbmRyZXdzLmFjLnVr

Nathalie Georgia Brandt

Nathalie Georgia Brandt Calum Thomas McHale

Calum Thomas McHale Gerald Michael Humphris

Gerald Michael Humphris