- Institute of Education, HSE University, Moscow, Russia

Anorexia is a serious threat to young women’s wellbeing worldwide. The effectiveness of mental health intervention and treatment is often evaluated on the basis of changes in the personal networks; however, the development of such measures for young women with anorexia is constrained due to the lack of quantitative descriptions of their social networks. We aim to fill this substantial gap. In this paper, we identify the basic properties of these women’s personal networks such as size, structure, and proportion of kin connections. The empirical analysis, using a concentric circles methodology, is based on 50 ego networks constructed on data drawn from interviews with Russian-speaking bloggers who have been diagnosed with anorexia and write about this condition. We conclude that young women with anorexia tend to support a limited number of social ties; they are prone to select women as alters, but do not have a preference to connect to their relatives. Further research is needed to elucidate whether these personal network characteristics are similar among women with anorexia who belong to different age, ethnic, cultural, and income groups.

Introduction

Anorexia is an eating disorder (ED) related to significant physical and mental health problems in adolescence and adulthood (Galmiche et al., 2019). This ED is characterized by restriction of food intake, fear of becoming fatter, and distortions of body image (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Girls are 2–3 times more likely than boys to face anorexia in their teenage years (Steiner and Lock, 1998; Hoek, 2006; Nagl et al., 2016; Galmiche et al., 2019). This is often explained by the social expectations of women (especially women’s bodies) in contemporary societies (Boskind-Lodahl, 1976; Mahowald, 1992; Malson, 1998; Bruch, 2001; Dahlenburg et al., 2019; Giordano, 2020).

Anorexia, as with other self-harming behaviors, is associated with difficulties in interpersonal relations (Tiller et al., 1997; Patel et al., 2016; Cardi et al., 2018; Pace et al., 2018; Birmachu et al., 2019; Okada et al., 2019). Although the relationship between anorexia and personal connections has been investigated, research on this topic has mostly provided qualitative descriptions or only indirectly focused on young women’s social networks (Leonidas and dos Santos, 2014). Studies that have revealed quantitative features of the personal networks of young women with anorexia are scarce and were conducted in a limited number of countries (Quiles Marcos and Terol Cantero, 2009; Tubaro and Mounier, 2014; Pallotti et al., 2018). Additionally, we should note the lack of research on the social networks of people with anorexia in Eastern Europe, especially Russia. Therefore, further research is needed to shed light on the social contexts of these women.

The present study fills this gap. We describe the main characteristics of the personal networks of adolescents and young adult women with diagnosed anorexia. The analysis is based on self-reported ego-networks collected from 50 Russian-speaking young women in the summer (July–August) of 2020.

The contribution of our study is twofold. First, we provide quantitative descriptions of personal networks of young women with anorexia. There is a lack of information on such networks in the scientific literature and our paper provides this valuable data. Second, such information has practical significance because the measurement of the effectiveness of the many types of interventions and treatments targeted at the improvement of women’s mental health is often based on the analysis of changes in their personal networks (Anderson et al., 2015; Siette et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2020).

The paper starts with an overview of network-based research on people with anorexia. It proceeds with a description of the methodology. Finally, the results are reported and discussed.

Literature Review

During adolescence, teenagers actively transform their personal social networks along with significant life events such as separating from their families, taking their first steps in their educational and professional development, and establishing new friends and romantic contacts (Giordano, 2003; Cotterell, 2013). People who surround young adults and adolescents at this time could either provide support and contribute to their wellbeing in various social spheres or influence their involvement in risky and practices deemed deviant by society (López et al., 1989; Wells and Rankin, 1991; Lorant and Tranmer, 2019; Webster et al., 2021).

Anorexia is one of the self-harming behaviors that often originates in adolescence and is most prevalent among girls (Galmiche et al., 2019). Moreover, it is associated with the highest rates of premature mortality among EDs (Arcelus et al., 2011; Keshaviah et al., 2014) and is connected with multiple comorbid mental health problems (Jordan et al., 2008; Martinussen et al., 2017; Marucci et al., 2018). Adult food intake and body image are both significantly dependent on the social networks that are formed in adolescence (Ali and Lindström, 2006; Fletcher et al., 2011; Simone et al., 2018; Grund and Tatum, 2019). For example, in social interactions within female peer groups during adolescence, women may acquire cultural values of beauty and practices of body care via the emulation of dieting practices, body size comparisons, and weight-based teasing that encourages them to lose weight (Allison et al., 2014). All in all, the effect of personal social networks turns out to be an important factor in behavior deemed deviant by society. Therefore, the quantitative analysis of personal networks of young women with anorexia could have significant implications for the prevention and management of this ED (Ferguson et al., 2011).

Network Characteristics of People With Anorexia

The psychological and sociological literature suggests that people with anorexia might experience difficulties with communication, feel socially isolated, and report lower levels of social support from family members and significant others (Tiller et al., 1997; Levine, 2012; Patel et al., 2016; Cardi et al., 2018; Pace et al., 2018; Birmachu et al., 2019; Okada et al., 2019). Specifically, they are described as having problems establishing new relationships and maintaining old ones, caused by a distrust of others (Patel et al., 2016; Cardi et al., 2018; Quiles et al., 2020; Datta et al., 2021; Rowlands et al., 2021). These difficulties are experienced both before and after anorexia. Some scholars argue that these problems usually become more severe during anorexia (Cardi et al., 2018). Although the interpersonal relationships of people with anorexia have been described in theoretical and empirical qualitative studies (Patel et al., 2016; Westwood et al., 2016; Paul et al., 2018), quantitative descriptions of these people’s personal networks are scarce (Leonidas and dos Santos, 2014). This, consequently, significantly restricts perspectives for the exploration of social network factors in anorexia development.

To extend our knowledge of the structural characteristics of the personal networks of people with anorexia, we will focus on three interrelated aspects: (1) network size, (2) network structure, (3) kinship network. In this section of the paper, along with a literature review, we introduce our hypotheses and describe the characteristics of social networks.

Network Size

Network size, one of the central characteristics of the social network structure, is usually defined as the number of alters in a personal social network (Wasserman and Faust, 1994; Crawford et al., 2018). Literature on social support reports that the average size of the social support network of individuals with anorexia varies from 5 to 16 alters (Quiles Marcos and Terol Cantero, 2009; Tubaro and Mounier, 2014; Pallotti et al., 2018). Notably, two of these three studies include both men and women (Tubaro and Mounier, 2014; Pallotti et al., 2018), making it difficult to hypothesize whether the network size of people with diagnosed anorexia is gender-specific. Therefore, based on previous studies of mixed-gendered samples we hypothesize that: The average network size of young women with anorexia will range from 5 to 16 actors (H1).

Network Cohesion

Social cohesion is a widely applied concept in the social sciences (Friedkin, 2004). It might be defined as a resource of a group or society that affects individuals at both local and community levels (Lin, 2001; Martí et al., 2017). From a social network perspective, cohesion usually refers to the general level of network connectedness (Wasserman and Faust, 1994; Martí et al., 2017). In order to measure social cohesion, researchers usually calculate the density of the social network (Pallotti et al., 2018). In this paper, we consider network cohesion from a different perspective. We argue that the local sub-group structure within personal networks needs to be taken into account, because the extent to which an actor is connected to multiple cohesive subsets of alters plays a significant role in certain types of social support (Martí et al., 2017). Previous research demonstrates that individuals within the personal networks of people with anorexia are at least acquainted with each other or maintain other types of relationships such as friendship (Tubaro and Mounier, 2014; Pallotti et al., 2018). Thus, as a measure of social cohesion we use the proportion of isolates in an individual’s social network and based on previous empirical findings (Tubaro and Mounier, 2014; Pallotti et al., 2018), we hypothesize that: The network structure of young women with anorexia will be of middle-high cohesiveness. This means that the proportion of isolates in the networks would be less than 0.5 (H2).

Kinship Network

People with anorexia tend to have difficulties with emancipation from their families and are prone to having limited social contact with people outside their families (Ruuska et al., 2007). Moreover, they frequently mention their mothers among their primary social support providers (Quiles Marcos and Terol Cantero, 2009). However, scholars indicate that the social surroundings of people with anorexia have become more diverse due to technological advances, specifically the opportunity to establish and maintain relationships via the internet, and include a large number of partners and friends (Tubaro and Mounier, 2014; Pallotti et al., 2018). Some papers demonstrate that these connections may worsen their health condition because the members of these communities can motivate each other toward extreme weight loss, as in pro-ana communities, which treat anorexia as a manageable lifestyle (Rodgers et al., 2012; Mento et al., 2021; Osler and Krueger, 2021; Nova et al., 2022). At the same time, online communities comprising people with anorexia who support personal recovery exist, such as pro-recovery communities that encourage people with anorexia to get treatment and may help them improve their health (Branley and Covey, 2017; Lamarre and Rice, 2017; Kenny et al., 2019). Additionally, the personal networks of people with anorexia might include health workers such as psychologists or psychiatrists (Quiles Marcos and Terol Cantero, 2009; Tubaro and Mounier, 2014; Pallotti et al., 2018). Summarizing, current research suggests that kin would outnumber non-kin in personal social networks of people with anorexia, although the proportion of non-kin might increase for various reasons. This leads us to our third hypothesis: Among the members of the young women with anorexia, kin will outnumber non-kin (H3).

People with anorexia usually state that their body condition and weight management are the most important parts of their life, both after having anorexia and during its active phase, and scholars claim that people outside the family circle provide people with anorexia with dieting tips and related information; for example, friends might give advice on pills and exercise (Brotsky and Giles, 2007; Haas et al., 2011; Pallotti et al., 2018). While family members do not always share their attitudes toward food and body, we suppose that alters outside the family circle could be classified by people with anorexia as more significant to them than family members because of their potential function as providers of body management information. We therefore hypothesize that: The non-kin members of the social networks of young women with anorexia will be perceived subjectively as being closer (H4).

Finally, as the social networks of people with anorexia are usually predominantly composed of females (Tubaro and Mounier, 2014; Pallotti et al., 2018) we hypothesized that: Of the non-kin personal network members of women with anorexia, a majority will be women (H5).

Additionally, in the section “Results,” we report the basic descriptive structural metrics of personal networks of women with anorexia. These descriptions contribute to the general understanding of the composition of the social networks of people with anorexia.

Materials and Methods

Sample

We collected data from young Russian-speaking female bloggers who have public blogs on the Russian social networking site VK.1 In these blogs, these young women write about their current health status and relationships with other people as well as other personal information. Additionally, bloggers interact with their audience via text and video on anorexia-related topics. The participants in our study were recruited using purposive sampling (Onwuegbuzie and Leech, 2015) to ensure the heterogeneity of narratives. Namely, we created a list of women who might be willing to participate in our research with a quota on the city and the number of subscribers on VK, then we contacted these people in personal text messages. Out of 156 women contacted, 50 agreed to participate in this study. As a result, in July and August 2020 we conducted biographical interviews with young female bloggers medically diagnosed with anorexia from more than 30 different Russian, Ukrainian, Kazakhstani, and Belarussian cities. Some of these bloggers hold pro-anorexia views (35), while the others support recovery (15). The age of participants ranges from 14 to 25. The description of the sample is in the Supplementary Appendix Table 1. The interviews were conducted via Skype due to the quarantine measures in Russia.

Data Collection

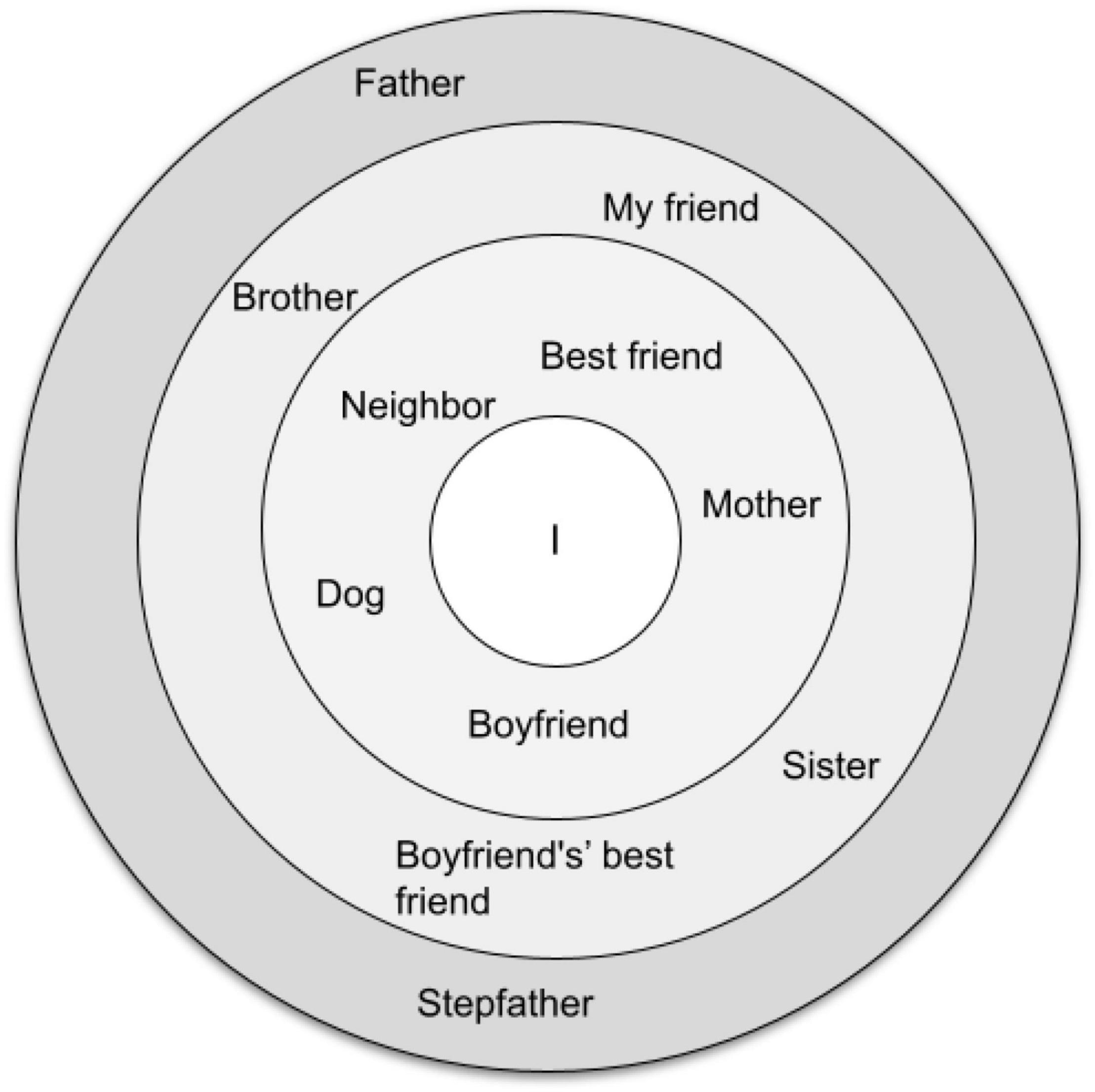

We gathered the data on the personal network connections of these young women using semi-structured biographical interviews (Rosenthal, 2004). The interviews consisted of the following parts: (1) The unstructured narratives of the young women about their lives from the very beginning to the time of the interview, (2) Clarifying questions, and (3) The elicitation of their personal social networks. The personal networks were obtained and analyzed using the concentric circles method (Altissimo, 2016; Tubaro et al., 2016; Van Waes and Van den Bossche, 2020). Participants (egos) were asked to name people they believed to belong to their social surroundings (alters) and to specify the relations between these individuals. In addition, the young women were asked to rate their alters’ significance in their life and put them into three concentric circles according to this ranking, with the ego at the center (Figure 1). Alters subjectively considered to be more significant to ego are in the closest circle to her (1-rated) and those alters who were not included in these circles were considered by the young women as not significant (4-rated). All the young women completed informed consent forms. The research complies with ethical norms of [the University name was removed for review purposes] University and was approved by the IRB.

Figure 1. The social contacts map of participant 2 (translated from Russian). In the center of the map is the blogger herself. In the first circle are people and an animal who she named the most significant to her (her dog, boyfriend, mother, neighbor, and best friend). In the second circle are people she claimed to be less important (brother, friend, sister, and boyfriend’s best friend). The least close to the participant are her father and stepfather. These people are placed in the third circle. She placed no one outside the circles, i.e., this participant did not name people who are not important to her.

In this paper we will focus on personal networks in which the ego is the female blogger with anorexia, the alters are the members of the perceived social surroundings, and the ties between these people are the social relations (talking and other forms of interaction) that, according to the ego’s suggestions, exist between her and her alters.

Social Network Analysis: Measures

One of the central network characteristics is the network size. The sizes of network structures (graph) can be captured by calculating the number of nodes and edges. Within the framework of this study, we considered the network size to be the number of alters (nodes) connected (edges) to the ego (target node).

As a measure of social cohesion, we used the proportion of isolates in a given network. An isolate is an actor who does not have any connections within the network. The proportion of isolates is the ratio between the number of isolates and the network size.

We used Python 3.7.4 for the computations, with networkx Python package 2.6.2 employed to calculate the descriptive statistics of the network. Additionally, we used Pearson’s correlation coefficient in and Student’s t-test (SciPy 1.7.1 package).

Results

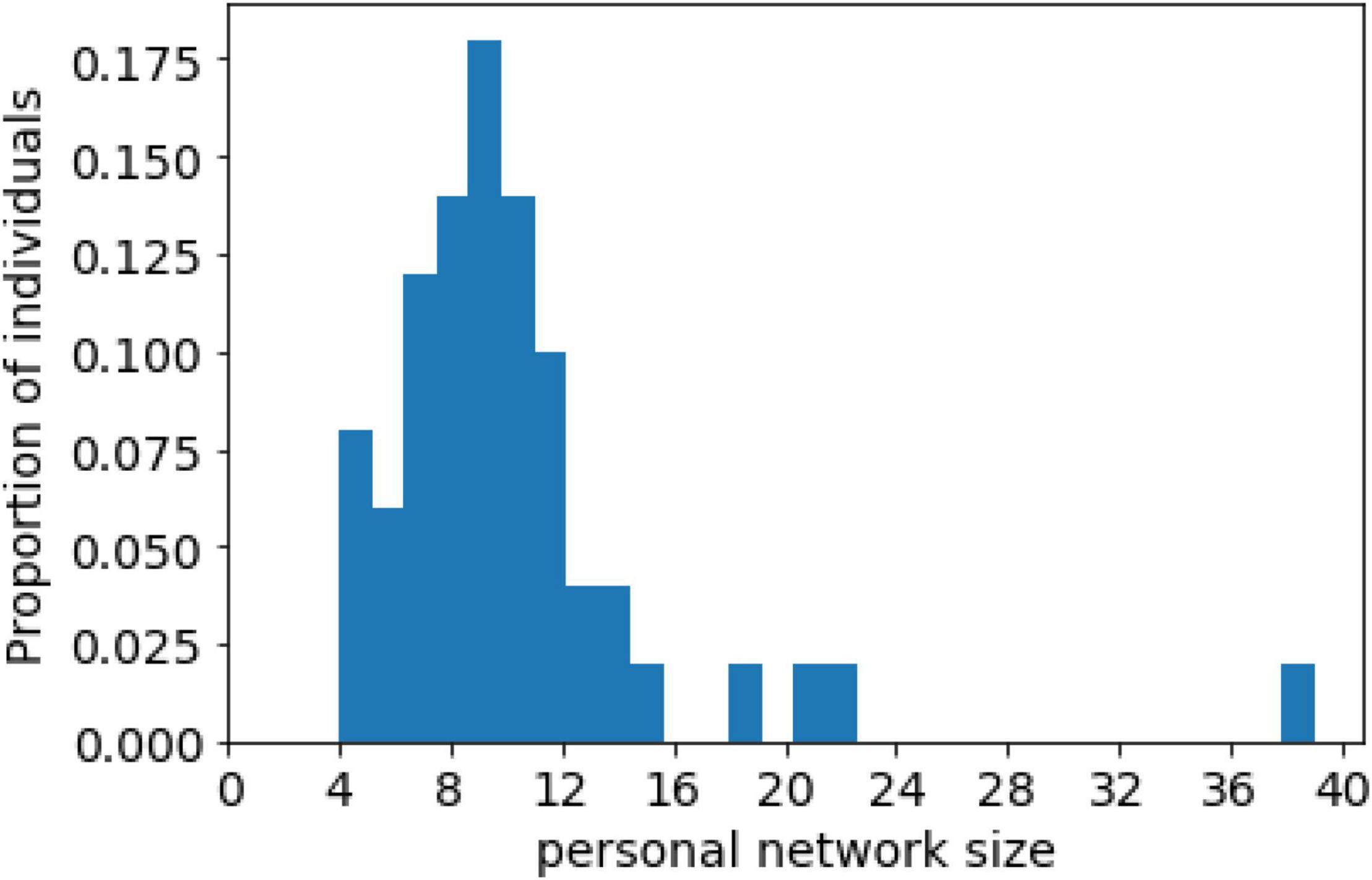

The distribution of the personal network size is presented in Figure 2. The network size varied from 4 to 39. For the majority of the individuals (N = 47, 94% of the sample) it ranged between 5 and 16. On average, the number of alters was 10.24 (SD = 5.56); the median was 9. The distribution of the network size was not normal. We found a small proportion of outliers with extremely high numbers of alters, which aligns with network theory (Barabási and Albert, 1999), which predicts the presence of multiple actors with limited numbers of ties and a few individuals with many ties (so-called hubs). After the exclusion of the most popular individual (with 39 alters in their personal network), the average number of alters for the sample decreased to 9.65 (SD = 3.74). The median network size remained at 9. In further calculations, we analyzed the sample without this outlier.

Our findings support H1, in that the network size for the major part of young women with anorexia ranges from 5 to 16.

On average, there were 5.33 (SD = 3.33) isolated individuals in the observed personal networks, with a median of 5. The proportion of isolated individuals in personal networks was 0.53 (SD = 0.21) (Figure 3). These results support H2. These values might suggest that people tend to diversify their social relationships and maintain connections with both cohesive communities and isolated individuals. Approximately half of a given personal network consisted of isolated alters, while the rest of the network was a connected group of multiple cohesive communities.

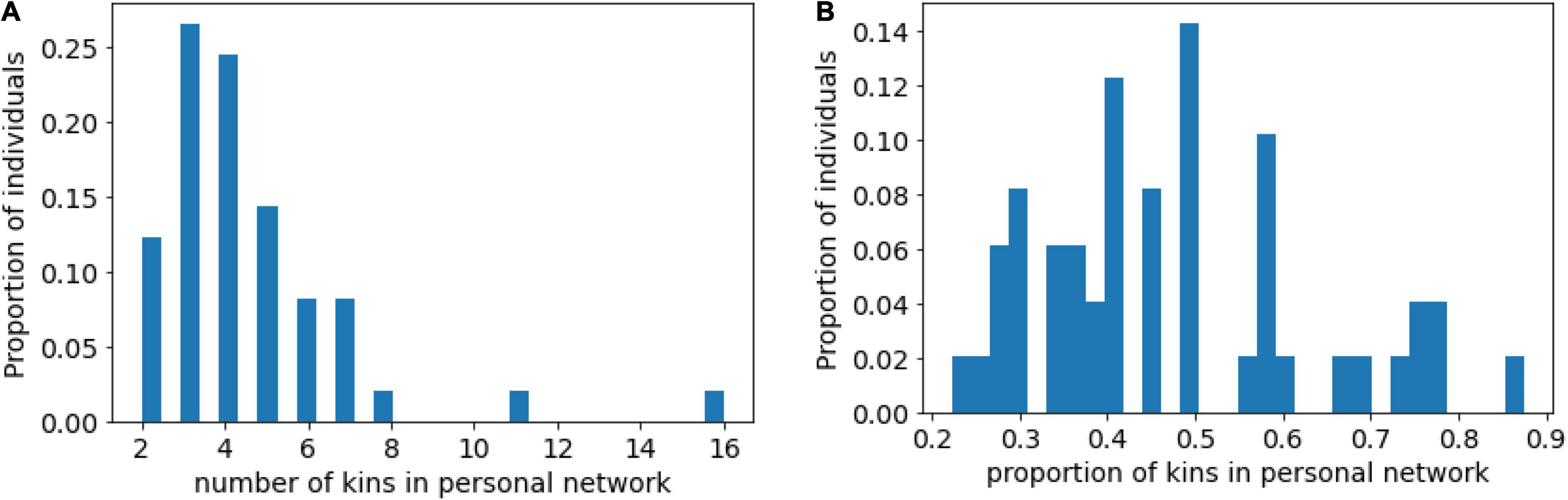

On average, the individuals maintained relationships with 4.51 family members (SD = 2.47) (Figure 4A). For each network we computed the proportion of kin alters in personal networks. For the whole sample, the average fraction of kin alters was 0.47 (SD = 0.16) (Figure 4B). Thus, we conclude that the proportion of kin in personal networks of women with anorexia is not greater than the proportion of non-kin, in contradiction to H3.

Figure 4. (A) Distribution of number of kin alters in personal networks; (B) Distribution of proportion of kin alters in personal networks.

To examine whether young women with anorexia tend to select non-kin members as the closest alters in their networks, for each personal network, we computed the average significance of the kin and non-kin members in the personal network (Figures 5A,B). The average significance of kin alters was 1.13 (SD = 0.59), and 1.12 (SD = 0.60) for non-kin alters (p-value = 0.95, t-test). Thus, we did not find a difference between the levels of significance for kin and non-kin alters, and the results do not support H4.

Figure 5. (A) Relationship between average kin and non-kin alter significance; (B) Distribution of average difference between non-kin and kin alter significance.

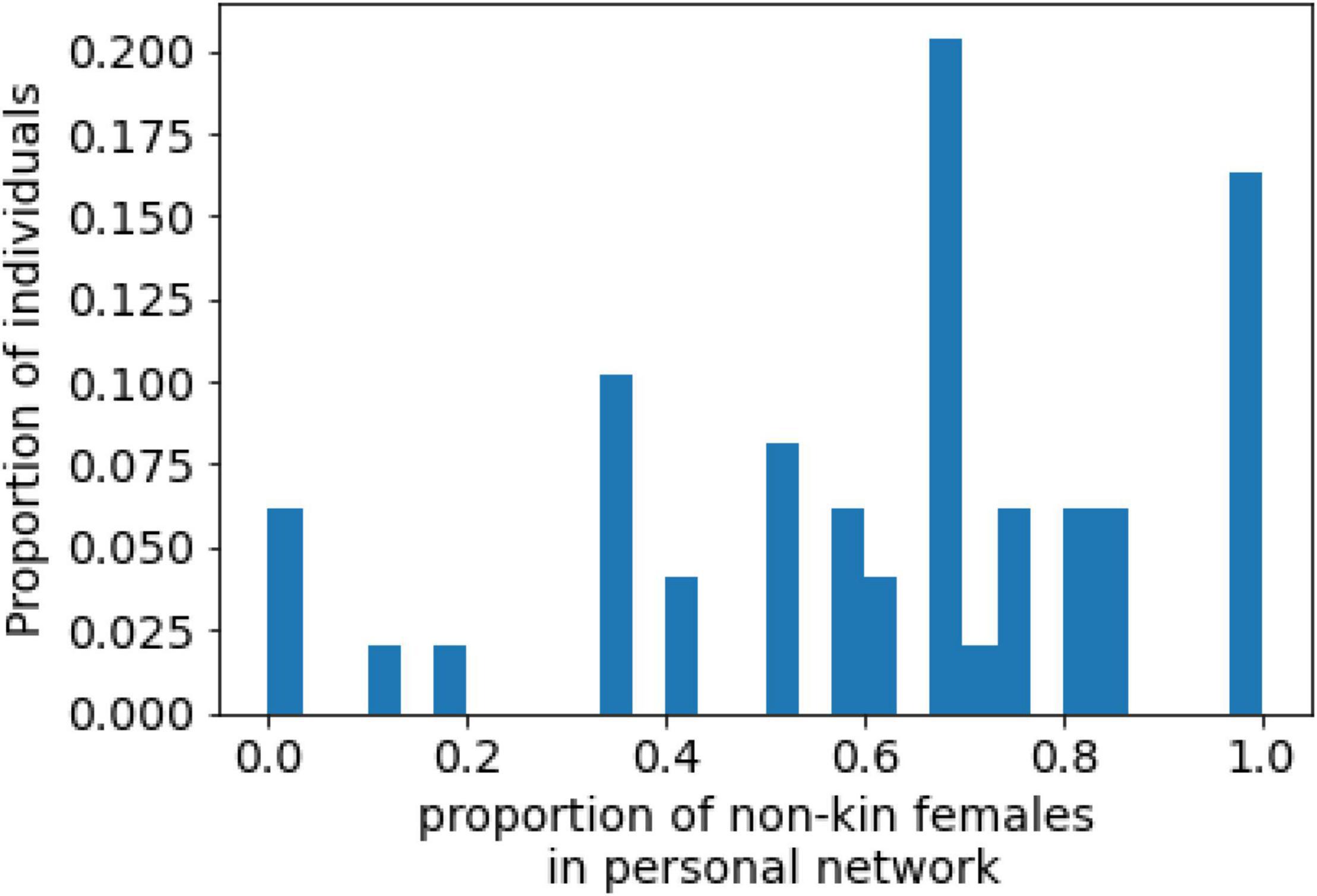

The average proportion of females in non-kin networks was 0.62 (SD = 0.27), and the median was 0.67 (Figure 6). In more than two thirds of the participants’ networks (68%), the proportion of females among the non-kin alters was greater than half. Thus, the evidence supports H5, and we might conclude that participants tend to create ties with females, and that this tendency is independent of their overall network structure.

Additional descriptive statistics on personal networks of young women with anorexia and association between the variables are reported in the Supplementary Appendix.

Discussion

This paper addresses the gap in the literature on the relationships of young women with anorexia by providing information on the quantitative aspects of their personal networks. Previous studies on this topic are scarce (Quiles Marcos and Terol Cantero, 2009; Tubaro and Mounier, 2014; Pallotti et al., 2018), and most is qualitative, which significantly limits scholars’ and practitioners’ abilities to develop reliable measures for interventions and treatment outcomes based on network indicators. We report on young women’s personal networks in terms of size, structure, and kinship network. The calculations of these parameters were made on the basis of 50 ego networks described by Russian-speaking bloggers in qualitative interviews in the summer of 2020.

The results regarding the average personal network size of young women with anorexia largely agree with the previous research (H1). We demonstrated, consistent with Quiles Marcos and Terol Cantero (2009), Tubaro and Mounier (2014), and Pallotti et al. (2018) that on average, these women maintain relationships with 10 people. A personal network of this size does not, at first, appear critically small because studies show that the active network of a person in the general population usually comprises at least 20–30 people (Maguire, 1983; Lubbers et al., 2019). However, these numbers include both online and offline contacts. The literature on the utilization of mental health services demonstrates that a limited number of personal connections is often related to increased usage of mental health services (Mitchell, 1989; Albert et al., 1998; Thoits, 2011) because the person is not surrounded by people who can provide the necessary care and support. Moreover, small personal network size is associated with an elevated likelihood of compulsory hospital admission (Kogstad et al., 2013). Therefore, we suppose that in future studies it would be important to address the association between personal network size and the severity of anorexia outcomes for women with this condition. This could extend understanding of whether interventions tailored toward the improvement of the general social skills of young women (Spence, 2003) are also effective in the prevention of severe anorexia symptoms (Pratt and Woolfenden, 2002; Dimitropoulos et al., 2016; Hay et al., 2019; Gan et al., 2021).

In line with previous research, we found that our participants had connections with both cohesive communities and isolated individual actors (H2) (Tubaro and Mounier, 2014; Pallotti et al., 2018). By contrast, in the general population, a person’s social network is made up of 10 percent or less of isolated alters on average (Golinelli et al., 2010; Martí et al., 2017; Stadel and Stulp, 2022). This means that the social network of the ordinary person is much denser than the networks of our research participants. The connection between social network density and diversity is complicated (Walker, 2015; Lee et al., 2020). Network density is positively related to personal wellbeing only when the individual is in a self-affirming social environment (Walker, 2015). Otherwise, being surrounded by many people who actively interact with each other does not have a positive effect on the individual’s mental health because she feels trapped in the social groups in which she is included. Network diversity, despite being connected to improvements in psychological wellbeing, is not related to an increase in personal feelings of social support (Müller et al., 2007). This means that in a woman with anorexia, a high level of social contact diversity could coincide with personal feelings of loneliness. We believe this could be true of our study participants, who told us during the interviews that many people they interact with tend to produce negative body talk and collaborate on this production of negative statements (Mikhaylova, 2022). Young women often cannot cease communication with these abusive individuals because they are their classmates, teachers, or even family members (Shannon and Mills, 2015). Furthermore, our data do not allow us to quantitatively determine the way the diversity and density of the personal social networks of women with different incomes are connected to their experience of anorexia, which is a question that future studies can address. Economic inequality means that it might be easier for some women to change their social environments and, as a result, improve their psychological wellbeing; for others, such a move may be much more problematic.

Contrary to our assumptions based on previous studies (Quiles Marcos and Terol Cantero, 2009; Tubaro and Mounier, 2014; Pallotti et al., 2018), we found that the proportion of kin members in the participants’ personal networks was not higher than the proportion of other members of these networks (H3). Furthermore, people in the general population also report that almost half of their personal network consists of relatives, and this figure holds across different country samples (Wellman and Wortley, 1989; Dunbar and Spoors, 1995; Grossetti, 2007). Because the quality of family relationships could influence the success of psychotherapy (Sapin et al., 2016; Fleming et al., 2021), we suggest cautious interpretations of the proportion of kin in the personal networks of people with psychological problems. Women with mental health problems who experience overload and ego-centered conflict in family relationships could show patterns of evaluated psychological distress (Sapin et al., 2016; Tournier et al., 2021). Therefore, we believe that future studies, preferably longitudinal, are necessary to clarify the connection between kinship networks and treatment outcomes for women with anorexia.

We found no statistically significant difference between the subjective closeness of kin and non-kin members of the participants’ social networks (H4). This contradicts the assumptions formulated on the basis of the studies by Brotsky and Giles (2007), Haas et al. (2011), and Pallotti et al. (2018). Moreover, this contradicts the research on the general population, which claims that people at various life stages tend to perceive their relatives as socially closer than non-kin members of their personal networks (Shulman, 1975; Wellman and Wortley, 1989; Aeby et al., 2018). Nevertheless, we deduced that women with larger personal networks maintain both deep and shallow relationships with non-kin members of their networks. Support from family members has been described in the literature as being more important for one’s personal mental health than support from friends and significant others (Shor et al., 2013; Aeby et al., 2020). Nonetheless, as the importance of familial support increases with age (Shor et al., 2013; Widmer et al., 2018; Woods et al., 2020), we believe it likely that the value of family support for older women (Gadalla, 2008) with anorexia might be higher. This idea would need further investigation carried out on older individuals.

In accordance with Tubaro and Mounier (2014) and Pallotti et al. (2018), we discovered that young women with anorexia had a high proportion of female non-kin personal network members (H5). This finding corresponds with social comparison studies that have shown that body dissatisfaction and eating problems among women are related to the internalization of the body-related attitudes shared by significant women in their lives, such as mothers, sisters, and close female friends (Thompson et al., 1999; Lev-Ari et al., 2014a,b; Nerini et al., 2016; Betz et al., 2019; Pollet et al., 2021). Additionally, this result is in line with research on the general population, which has found that non-kin contacts account for more than half of people’s personal networks (Dunbar and Spoors, 1995; McPherson et al., 2006; Roberts et al., 2008, 2009). Because our participants came from Russian-speaking countries, we acknowledge that gender ideology and social expectations of women in this cultural context (White, 2005; Barrett and Buckley, 2009; Kosterina, 2012; Turbine, 2012) could influence the functioning of social comparison mechanisms among women, especially in the family context. Therefore, we think that comparative research of the personal networks of women with anorexia from different regions worldwide is needed to show how the environments of the state and social institutions can moderate the effect of social connections on the wellbeing of such women.

Because the data was collected during a COVID-19 lockdown, participants were additionally asked about the perceived effects of the pandemic on their mental and physical health and social networks. They mentioned that lockdown and other consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic have influenced their eating behavior. As has been reported in comparable research (Phillipou et al., 2020; Schlegl et al., 2020), participants claimed that they started to exercise and control their food intake more. They associate these changes with lockdown restrictions. Women also reported that they felt more anxious about their current and future educational and career prospects, which corresponds with studies of emotional wellbeing during COVID-19 pandemic among people with eating disorders (Sideli et al., 2021; Linardon et al., 2022). These studies have demonstrated that during COVID-19 pandemic people with eating disorders have experienced elevated feelings of stress, fear, and anxiety. At the same time, our study participants did not note any change in their relations with people in their personal networks contrary to some of the other studies of the perceived social support among people with eating disorders during COVID-19 pandemic (Sideli et al., 2021; Linardon et al., 2022). Perhaps our participants were able to maintain relationships with people from their personal networks via digital technologies that is why they did not notice any changes in their social networks. Additionally, they could have felt peer support from the members of the online eating disorder communities as many researchers, for example, Albano et al. (2021) have discovered that during emergent global situations such as COVID-19 pandemic these communities may provide for the members the feelings of being understood by people with comparable life situations.

Limitations

Our research is not without shortcomings. First, the sample comprises young white women, whose personal networks may differ from those of women of color (Ajrouch and Antonucci, 2018) and those who belong to other minorities (Frost et al., 2016; Watson et al., 2019; Fischer, 2021), as well as those of women with anorexia who belong to other age groups (Midlarsky and Nitzburg, 2008; Lapid et al., 2010; Scholtz et al., 2010). Second, because women with anorexia are a hard-to-reach population, especially in Russian-speaking countries, where there is no officially gathered data on the prevalence of EDs, in this paper, we estimated the network characteristics of only 50 women. However, we hope that future studies can utilize larger samples, creating opportunities for a wider range of between-group comparisons. Third, our sample comprises women bloggers and we do not know whether their social contacts differ from those of young women with anorexia who do not blog. Fourth, reports on the personal relations that young women maintain should be regarded with caution due to memory (Brewer, 2000), sensitivity (Cronin et al., 2020), problems with the attribution of roles to the members of personal networks (Bush et al., 2017), and other interview-related issues (Feld and Carter, 2002; Kogovšek and Ferligoj, 2005). Fifth, when reporting on the personal networks of young women based on their narratives, we should remember that these are only the young women’s perceptions of their relations (Bayer et al., 2020; Feld and McGail, 2020). Additional research is needed that includes the perspectives of the members of these personal networks (Suitor et al., 2020) to reveal how the members of these personal social circles perceive their relations with young women with anorexia.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that young women with anorexia do have small personal social networks. On average, half of the alters in their personal networks are in communication with each other and potentially might be involved in the same social circles. We did not find that kin alters outnumber non-kin in these social networks. At the same time, it could be argued that women with anorexia maintain relationships primarily with other women. Further research, better on larger samples, is needed to elucidate whether these personal network characteristics are similar between women of different ages, incomes, ethnicities, and cultural groups.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by HSE University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by Russian Science Foundation (project No 21-78-00069).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.848774/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ This dataset is a part of one of the authors’ Ph.D. dissertations and can be obtained from the author directly if needed.

References

Aeby, G., Gauthier, J.-A., and Widmer, E. D. (2020). Patterns of support and conflict relationships in personal networks and perceived stress. Curr. Sociol. 2020:926.

Aeby, G., Widmer, E. D., Česnuitytė, V., and Gouveia, R. (2018). “Mapping the Plurality of Personal Configurations,” in Families and Personal Networks: An International Comparative Perspective Palgrave Macmillan Studies in Family and Intimate Life, eds K. Wall, E. D. Widmer, J. Gauthier, and R. Gouveia (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 131–166. doi: 10.1057/978-1-349-95263-2_5

Ajrouch, K. J., and Antonucci, T. C. (2018). Social relations and health: comparing “invisible” arab americans to blacks and whites. Soc. Ment. Health 8, 84–92. doi: 10.1177/2156869317718234

Albano, G., Bonfanti, R. C., Gullo, S., Salerno, L., and Lo Coco, G. (2021). The psychological impact of COVID-19 on people suffering from dysfunctional eating behaviours: a linguistic analysis of the contents shared in an online community during the lockdown. Res. Psychother. 24:557. doi: 10.4081/ripppo.2021.557

Albert, M., Becker, T., Mccrone, P., and Thornicroft, G. (1998). Social networks and mental health service utilisation-a literature review. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 44, 248–266. doi: 10.1177/002076409804400402

Ali, S. M., and Lindström, M. (2006). Socioeconomic, psychosocial, behavioural, and psychological determinants of BMI among young women: differing patterns for underweight and overweight/obesity. Eur. J. Public Health 16, 324–330. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki187

Allison, S., Warin, M., and Bastiampillai, T. (2014). Anorexia nervosa and social contagion: Clinical implications. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry 48, 116–120. doi: 10.1177/0004867413502092

Altissimo, A. (2016). Combining egocentric network maps and narratives: an applied analysis of qualitative network map interviews. Sociol. Res. Online 21, 1–13.

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edn. Arlington, TX: American Psychiatric Association. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Anderson, K., Laxhman, N., and Priebe, S. (2015). Can mental health interventions change social networks? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 15:297. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0684-6

Arcelus, J., Mitchell, A. J., Wales, J., and Nielsen, S. (2011). Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders: a meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch. Gener. Psychiatry 68, 724–731. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74

Barabási, A.-L., and Albert, R. (1999). Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science 286, 509–512. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.509

Barrett, J. B., and Buckley, C. (2009). Gender and perceived control in the russian federation. Eur. Asia Stud. 61, 29–49. doi: 10.1080/09668130802532910

Bayer, J. B., Lewis, N. A., and Stahl, J. L. (2020). Who comes to mind? dynamic construction of social networks. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 29, 279–285. doi: 10.1177/0963721420915866

Betz, D. E., Sabik, N. J., and Ramsey, L. R. (2019). Ideal comparisons: body ideals harm women’s body image through social comparison. Body Image 29, 100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.03.004

Birmachu, A. M., Heidelberger, L., and Klem, J. (2019). Rumination and perceived social support from significant others interact to predict eating disorder attitudes and behaviors in university students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2019, 1–7. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2019.1682001

Boskind-Lodahl, M. (1976). Cinderella’s Stepsisters: a feminist perspective on anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Signs 2, 342–356. doi: 10.1086/493362

Branley, D. B., and Covey, J. (2017). Pro-ana versus pro-recovery: a content analytic comparison of social media users’ communication about eating disorders on twitter and tumblr. Front. Psychol. 8:1356. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01356

Brewer, D. D. (2000). Forgetting in the recall-based elicitation of personal and social networks. Soc. Networks 22, 29–43. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8733(99)00017-9

Brotsky, S. R., and Giles, D. (2007). Inside the “Pro-ana” community: a covert online participant observation. Eat. Disord. 15, 93–109. doi: 10.1080/10640260701190600

Bruch, H. (2001). The Golden Cage: The Enigma of Anorexia Nervosa. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bush, A. N., Walker, A. M., and Perry, B. L. (2017). “The framily plan”: Characteristics of ties described as both “friend” and “family” in personal networks. Network Sci. 5, 92–107. doi: 10.1017/nws.2017.2

Cardi, V., Mallorqui-Bague, N., Albano, G., Monteleone, A. M., Fernandez-Aranda, F., and Treasure, J. (2018). Social difficulties as risk and maintaining factors in anorexia nervosa: a mixed-method investigation. Front. Psychiatry 9:12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00012

Crawford, F. W., Wu, J., and Heimer, R. (2018). Hidden population size estimation from respondent-driven sampling: a network approach. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 113, 755–766. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2017.1285775

Cronin, B., Perra, N., Rocha, L. E. C., Zhu, Z., Pallotti, F., Gorgoni, S., et al. (2020). Ethical implications of network data in business and management settings. Soc. Networks 2020:782.

Dahlenburg, S. C., Gleaves, D. H., and Hutchinson, A. D. (2019). Anorexia nervosa and perfectionism: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 52, 219–229. doi: 10.1002/eat.23009

Datta, N., Foukal, M., Erwin, S., Hopkins, H., Tchanturia, K., and Zucker, N. (2021). A mixed-methods approach to conceptualizing friendships in anorexia nervosa. PLoS One 16:e0254110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254110

Dimitropoulos, G., Freeman, V. E., Muskat, S., Domingo, A., and McCallum, L. (2016). “You don’t have anorexia, you just want to look like a celebrity”: perceived stigma in individuals with anorexia nervosa. J. Ment. Health 25, 47–54. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1101422

Dunbar, R. I. M., and Spoors, M. (1995). Social networks, support cliques, and kinship. Human Nat. 6, 273–290. doi: 10.1007/BF02734142

Feld, S. L., and Carter, W. C. (2002). Detecting measurement bias in respondent reports of personal networks. Soc. Networks 24, 365–383. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8733(02)00013-8

Feld, S. L., and McGail, A. (2020). Egonets as systematically biased windows on society. Network Sci. 8, 399–417. doi: 10.1017/nws.2020.5

Ferguson, C. J., Winegard, B., and Winegard, B. M. (2011). Who is the fairest one of all? how evolution guides peer and media influences on female body dissatisfaction. Rev. Gener. Psychol. 15, 11–28. doi: 10.1037/a0022607

Fischer, M. M. (2021). Social exclusion and resilience: examining social network stratification among people in same-sex and different-sex relationships. Soc. Forces 2021:19. doi: 10.4324/9781003089995-3

Fleming, C., Brocque, R. L., and Healy, K. (2021). How are families included in the treatment of adults affected by eating disorders? A scoping review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 54, 244–279. doi: 10.1002/eat.23441

Fletcher, A., Bonell, C., and Sorhaindo, A. (2011). You are what your friends eat: systematic review of social network analyses of young people’s eating behaviours and bodyweight. J. Epidemiol. Comm. Health 65, 548–555. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.113936

Frost, D. M., Meyer, I. H., and Schwartz, S. (2016). Social support networks among diverse sexual minority populations. Am. J. Orthopsych. 86:91. doi: 10.1037/ort0000117

Gadalla, T. M. (2008). Eating disorders and associated psychiatric comorbidity in elderly Canadian women. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 11, 357–362. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0031-8

Galmiche, M., Déchelotte, P., Lambert, G., and Tavolacci, M. P. (2019). Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 109, 1402–1413. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy342

Gan, J. K. E., Wu, V. X., Chow, G., Chan, J. K. Y., and Klainin-Yobas, P. (2021). Effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions on individuals with anorexia nervosa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Edu. Counsel. 2021:22. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.05.031

Giordano, P. C. (2003). Relationships in Adolescence. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 29, 257–281. doi: 10.1023/A:1024586006966

Giordano, S. (2020). Secret hunger: the case of anorexia nervosa. Topoi 40, 545–554. doi: 10.1007/s11245-020-09718-x

Golinelli, D., Ryan, G., Green, H. D., Kennedy, D. P., Tucker, J. S., and Wenzel, S. L. (2010). Sampling to reduce respondent burden in personal network studies and its effect on estimates of structural measures. Field Methods 22, 217–230. doi: 10.1177/1525822X10370796

Grossetti, M. (2007). Are french networks different? Soc. Networks 29, 391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2007.01.005

Grund, T. U., and Tatum, T. (2019). Some friends matter more than others: BMI clustering among adolescents in four European countries. Network Sci. 7, 123–139. doi: 10.1017/nws.2018.20

Haas, S. M., Irr, M. E., Jennings, N. A., and Wagner, L. M. (2011). Communicating thin: a grounded model of online negative enabling support groups in the pro-anorexia movement. New Media Soc. 13, 40–57. doi: 10.1177/1461444810363910

Hay, P. J., Touyz, S., Claudino, A. M., Lujic, S., Smith, C. A., and Madden, S. (2019). Inpatient versus outpatient care, partial hospitalisation and waiting list for people with eating disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1:827. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010827.pub2

Hoek, H. W. (2006). Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 19, 389–394. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000228759.95237.78

Jordan, J., Joyce, P. R., Carter, F. A., Horn, J., McIntosh, V. V. W., Luty, S. E., et al. (2008). Specific and nonspecific comorbidity in anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 41, 47–56. doi: 10.1002/eat.20463

Kenny, T. E., Boyle, S. L., and Lewis, S. P. (2019). #recovery: Understanding recovery from the lens of recovery-focused blogs posted by individuals with lived experience. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019:23221.

Keshaviah, A., Edkins, K., Hastings, E. R., Krishna, M., Franko, D. L., Herzog, D. B., et al. (2014). Re-examining premature mortality in anorexia nervosa: a meta-analysis redux. Compreh. Psychiatry 55, 1773–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.07.017

Kogovšek, T., and Ferligoj, A. (2005). Effects on reliability and validity of egocentered network measurements. Soc. Networks 27, 205–229. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2005.01.001

Kogstad, R. E., Mönness, E., and Sörensen, T. (2013). Social networks for mental health clients: resources and solution. Comm. Ment. Health J. 49, 95–100. doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9491-4

Kosterina, I. (2012). Young married women in the russian countryside: women’s networks, communication and power. Eur. Asia Stud. 64, 1870–1892. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2012.717360

Lamarre, A., and Rice, C. (2017). Hashtag recovery:# eating disorder recovery on Instagram. Soc. Sci. 6:68.

Lapid, M., Prom, M., Burton, M., Mcalpine, D., Sutor, B., and Rummans, T. (2010). Eating disorders in the elderly. Int. Psychoger. 22, 23–36. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-81174-7_4

Lee, D. S., Stahl, J. L., and Bayer, J. B. (2020). Social resources as cognitive structures: thinking about a dense support network increases perceived support. Soc. Psychol. Q 83, 405–422. doi: 10.1177/0190272520939506

Leonidas, C., and dos Santos, M. A. (2014). Social support networks and eating disorders: an integrative review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 10, 915–927. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S60735

Lev-Ari, L., Baumgarten-Katz, I., and Zohar, A. H. (2014a). Mirror, mirror on the wall: How women learn body dissatisfaction. Eat. Behav. 15, 397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.04.015

Lev-Ari, L., Baumgarten-Katz, I., and Zohar, A. H. (2014b). Show me your friends, and i shall show you who you are: the way attachment and social comparisons influence body dissatisfaction. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 22, 463–469. doi: 10.1002/erv.2325

Levine, M. P. (2012). Loneliness and eating disorders. J. Psychol. 146, 243–257. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.606435

Linardon, J., Messer, M., Rodgers, R. F., and Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (2022). A systematic scoping review of research on COVID-19 impacts on eating disorders: a critical appraisal of the evidence and recommendations for the field. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 55, 3–38. doi: 10.1002/eat.23640

López, J. M. O., Redondo, L. M., and Martín, A. L. (1989). Influence of family and peer group on the use of drugs by adolescents. Int. J. Addict. 24, 1065–1082. doi: 10.3109/10826088909047329

Lorant, V., and Tranmer, M. (2019). Peer, school, and country variations in adolescents’ health behaviour: a multilevel analysis of binary response variables in six European cities. Soc. Networks 59, 31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2019.05.004

Lubbers, M. J., Molina, J. L., and Valenzuela-García, H. (2019). When networks speak volumes: variation in the size of broader acquaintanceship networks. Soc. Networks 56, 55–69. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2018.08.004

Ma, R., Mann, F., Wang, J., Lloyd-Evans, B., Terhune, J., Al-Shihabi, A., et al. (2020). The effectiveness of interventions for reducing subjective and objective social isolation among people with mental health problems: a systematic review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 55, 839–876. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01800-z

Mahowald, M. B. (1992). To be or not be a woman: anorexia nervosa, normative gender roles, and feminism. J. Med. Philosophy 17, 233–251. doi: 10.1093/jmp/17.2.233

Malson, H. (1998). The Thin Woman: Feminism, Post-Structuralism, and the Social Psychology of Anorexia Nervosa. Hove: Psychology Press.

Martí, J., Bolíbar, M., and Lozares, C. (2017). Network cohesion and social support. Soc. Networks 48, 192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2016.08.006

Martinussen, M., Friborg, O., Schmierer, P., Kaiser, S., Øvergård, K. T., Neunhoeffer, A.-L., et al. (2017). The comorbidity of personality disorders in eating disorders: a meta-analysis. Eat. Weight Disord. 22, 201–209. doi: 10.1007/s40519-016-0345-x

Marucci, S., Ragione, L. D., De Iaco, G., Mococci, T., Vicini, M., Guastamacchia, E., et al. (2018). Anorexia nervosa and comorbid psychopathology. Endocr. Metabol. Immune. Disord. Drug Targ. 18, 316–324. doi: 10.2174/1871530318666180213111637

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., and Brashears, M. E. (2006). Social isolation in america: changes in core discussion networks over two decades. Am. Soc. Rev. 71, 353–375. doi: 10.1177/000312240607100301

Mento, C., Silvestri, M. C., Muscatello, M. R. A., Rizzo, A., Celebre, L., Praticò, M., et al. (2021). Psychological impact of pro-anorexia and pro-eating disorder websites on adolescent females: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:2186. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18042186

Midlarsky, E., and Nitzburg, G. (2008). Eating disorders in middle-aged women. J. Gener. Psychol. 135, 393–408. doi: 10.3200/genp.135.4.393-408

Mikhaylova, O. R. (2022). Measuring moral panic propagation on the interpersonal level: case of pro-ana women bloggers. Interaction. Interview. Interpretation. 14.

Mitchell, M. E. (1989). The relationship between social network variables and the utilization of mental health services. J. Comm. Psychol. 17, 258–266. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(198907)17:3<258::aid-jcop2290170308>3.0.co;2-l

Müller, B., Nordt, C., Lauber, C., and Rössler, W. (2007). Changes in social network diversity and perceived social support after psychiatric hospitalization: results from a longitudinal study. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 53, 564–575. doi: 10.1177/0020764007082344

Nagl, M., Jacobi, C., Paul, M., Beesdo-Baum, K., Höfler, M., Lieb, R., et al. (2016). Prevalence, incidence, and natural course of anorexia and bulimia nervosa among adolescents and young adults. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 25, 903–918. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0808-z

Nerini, A., Matera, C., and Stefanile, C. (2016). Siblings’ appearance-related commentary, body dissatisfaction, and risky eating behaviors in young women. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 66, 269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.013

Nova, F. F., Coupe, A., Mynatt, E. D., Guha, S., and Pater, J. A. (2022). Cultivating the community: inferring influence within eating disorder networks on twitter. Proc. ACM Human Comp. Interact. 6, 1–33. doi: 10.1145/3492826

Okada, L. M., Miranda, R. R., das Graças Pena, G., Levy, R. B., and Azeredo, C. M. (2019). Association between exposure to interpersonal violence and social isolation, and the adoption of unhealthy weight control practices. Appetite 142:104384. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104384

Onwuegbuzie, A., and Leech, N. (2015). Sampling designs in qualitative research: making the sampling process more public. Qualit. Rep. 12, 238–254.

Osler, L., and Krueger, J. (2021). ProAna worlds: affectivity and echo chambers online. Topoi 12, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11245-021-09785-8

Pace, U., D’Urso, G., and Zappulla, C. (2018). Negative eating attitudes and behaviors among adolescents: the role of parental control and perceived peer support. Appetite 121, 77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.11.001

Pallotti, F., Tubaro, P., Casilli, A. A., and Valente, T. W. (2018). “You See Yourself Like in a Mirror”: The Effects of Internet-Mediated Personal Networks on Body Image and Eating Disorders. Health Communication 33, 1166–1176. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1339371

Patel, K., Tchanturia, K., and Harrison, A. (2016). An exploration of social functioning in young people with eating disorders: a qualitative study. PLoS One 11:e0159910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159910

Paul, E. C., Pazienza, R., Maestro, K. J., Flye, A., Mueller, P., and Martin, J. L. (2018). The impact of disordered eating behavior on college relationships: a qualitative study. J. Coll. Counsel. 21, 139–152. doi: 10.1002/jocc.12093

Phillipou, A., Meyer, D., Neill, E., Tan, E. J., Toh, W. L., Rheenen, T. E. V., et al. (2020). Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: initial results from the COLLATE project. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 53, 1158–1165. doi: 10.1002/eat.23317

Pollet, T. V., Dawson, S., Tovée, M. J., Cornelissen, P. L., and Cornelissen, K. K. (2021). Fat talk is predicted by body dissatisfaction and social comparison with no interaction effect: evidence from two replication studies. Body Image 38, 317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.05.005

Pratt, B. M., and Woolfenden, S. (2002). Interventions for preventing eating disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2002:2891. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002891

Quiles Marcos, Y., and Terol Cantero, M. C. (2009). Assesment of social support dimensions in patients with eating disorders. Spanish J. Psychol. 12, 226–235. doi: 10.1017/s1138741600001633

Quiles, Y., Quiles, M. J., León, E., and Manchón, J. (2020). Illness perception in adolescent patients with anorexia: does it play a role in socio-emotional and academic adjustment? Front. Psychol. 11:1730. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01730

Roberts, S. G. B., Dunbar, R. I. M., Pollet, T. V., and Kuppens, T. (2009). Exploring variation in active network size: constraints and ego characteristics. Soc. Networks 31, 138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2008.12.002

Roberts, S. G. B., Wilson, R., Fedurek, P., and Dunbar, R. I. M. (2008). Individual differences and personal social network size and structure. Person. Ind. Diff. 44, 954–964. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.10.033

Rodgers, R. F., Skowron, S., and Chabrol, H. (2012). Disordered eating and group membership among members of a pro-anorexic online community. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 20, 9–12. doi: 10.1002/erv.1096

Rowlands, K., Willmott, D., Cardi, V., Clark Bryan, D., Cruwys, T., and Treasure, J. (2021). An examination of social group memberships in patients with eating disorders, carers, and healthy controls. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 29, 733–743. doi: 10.1002/erv.2840

Ruuska, J., Koivisto, A.-M., Rantanen, P., and Kaltiala-Heino, R. (2007). Psychosocial functioning needs attention in adolescent eating disorders. Nordic J. Psychiatry 61, 452–458. doi: 10.1080/08039480701773253

Sapin, M., Widmer, E. D., and Iglesias, K. (2016). From support to overload: patterns of positive and negative family relationships of adults with mental illness over time. Soc. Networks 47, 59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2016.04.002

Schlegl, S., Maier, J., Meule, A., and Voderholzer, U. (2020). Eating disorders in times of the COVID-19 pandemic—Results from an online survey of patients with anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 53, 1791–1800. doi: 10.1002/eat.23374

Scholtz, S., Hill, L. S., and Lacey, H. (2010). Eating disorders in older women: Does late onset anorexia nervosa exist? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 43, 393–397. doi: 10.1002/eat.20704

Shannon, A., and Mills, J. S. (2015). Correlates, causes, and consequences of fat talk: a review. Body Image 15, 158–172. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.09.003

Shor, E., Roelfs, D. J., and Yogev, T. (2013). The strength of family ties: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of self-reported social support and mortality. Soc. Networks 35, 626–638. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2013.08.004

Shulman, N. (1975). Life-cycle variations in patterns of close relationships. J. Marr. Family 37, 813–821. doi: 10.2307/350834

Sideli, L., Lo Coco, G., Bonfanti, R. C., Borsarini, B., Fortunato, L., Sechi, C., et al. (2021). Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on eating disorders and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 29, 826–841. doi: 10.1002/erv.2861

Siette, J., Cassidy, M., and Priebe, S. (2017). Effectiveness of befriending interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 7:e014304. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014304

Simone, M., Long, E., and Lockhart, G. (2018). The dynamic relationship between unhealthy weight control and adolescent friendships: a social network approach. J. Youth Adolesc. 47, 1373–1384. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0796-z

Spence, S. H. (2003). Social skills training with children and young people: theory, evidence and practice. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 8, 84–96. doi: 10.1111/1475-3588.00051

Stadel, M., and Stulp, G. (2022). Balancing bias and burden in personal network studies. Soc. Networks 70, 16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2021.10.007

Steiner, H., and Lock, J. (1998). Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in children and adolescents: a review of the past 10 years. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 37, 352–359. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199804000-00011

Suitor, J. J., Gilligan, M., Rurka, M., and Hou, Y. (2020). Roles of egos’ and siblings’ perceptions of maternal favoritism in adult children’s depressive symptoms: a within-family network approach. Network Sci. 8, 271–289. doi: 10.1017/nws.2019.31

Thoits, P. A. (2011). Perceived social support and the voluntary, mixed, or pressured use of mental health services. Soc. Ment. Health 1, 4–19. doi: 10.1177/2156869310392793

Thompson, J. K., Coovert, M. D., and Stormer, S. M. (1999). Body image, social comparison, and eating disturbance: a covariance structure modeling investigation. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 26, 43–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199907)26:1<43::aid-eat6>3.0.co;2-r

Tiller, J. M., Sloane, G., Schmidt, U., Troop, N., Power, M., and Treasure, J. L. (1997). Social support in patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 21, 31–38. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199701)21:1<31::aid-eat4>3.0.co;2-4

Tournier, T., Hendriks, A. H. C., Jahoda, A., Hastings, R. P., Giesbers, S. A. H., Vermulst, A. A., et al. (2021). Family network typologies of adults with intellectual disability: associations with psychological outcomes. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 34, 65–76. doi: 10.1111/jar.12786

Tubaro, P., and Mounier, L. (2014). Sociability and support in online eating disorder communities: evidence from personal networks. Netw. Sci. 2, 1–25. doi: 10.1017/nws.2014.6

Tubaro, P., Ryan, L., and D’angelo, A. (2016). The visual sociogram in qualitative and mixed-methods research. Sociol. Res. Online 21, 180–197. doi: 10.5153/sro.3864

Turbine, V. (2012). Locating women’s human rights in post-soviet provincial russia. Eur. Asia Stud. 64, 1847–1869. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2012.681245

Van Waes, S., and Van den Bossche, P. (2020). Around and around: the concentric circles method as powerful tool to collect mixed method network data. Mixed Methods Appr. Soc. Network Anal. 2020, 159–174. doi: 10.4324/9780429056826-15

Walker, M. H. (2015). The contingent value of embeddedness: self-affirming social environments, network density, and well-being. Soc. Ment. Health 5, 128–144. doi: 10.1177/2156869315574601

Wasserman, S., and Faust, K. (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Watson, R. J., Grossman, A. H., and Russell, S. T. (2019). Sources of social support and mental health among LGB Youth. Youth Soc. 51, 30–48. doi: 10.1177/0044118X16660110

Webster, D., Dunne, L., and Hunter, R. (2021). Association between social networks and subjective well-being in adolescents: a systematic review. Youth Soc. 53, 175–210. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003148.pub3

Wellman, B., and Wortley, S. (1989). Brothers’ keepers: situating kinship relations in broader networks of social support. Sociol. Perspect. 32, 273–306. doi: 10.2307/1389119

Wells, L. E., and Rankin, J. H. (1991). Families and delinquency: a meta-analysis of the impact of broken homes. Soc. Prob. 38, 71–93. doi: 10.2307/800639

Westwood, H., Lawrence, V., Fleming, C., and Tchanturia, K. (2016). Exploration of friendship experiences, before and after illness onset in females with anorexia nervosa: a qualitative study. PLoS One 11:e0163528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163528

White, A. (2005). Gender roles in contemporary russia: attitudes and expectations among women students. Eur-Asia Stud. 57, 429–455. doi: 10.1080/09668130500073449

Widmer, E. D., Girardin, M., and Ludwig, C. (2018). Conflict structures in family networks of older adults and their relationship with health-related quality of life. J. Fam. Issues 39, 1573–1597. doi: 10.1177/0192513X17714507

Keywords: anorexia, networks, personal networks, mental health, young women

Citation: Mikhaylova O and Dokuka S (2022) Anorexia and Young Womens’ Personal Networks: Size, Structure, and Kinship. Front. Psychol. 13:848774. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.848774

Received: 05 January 2022; Accepted: 14 March 2022;

Published: 19 April 2022.

Edited by:

Gianluca Lo Coco, University of Palermo, ItalyReviewed by:

Connie Marguerite Musolino, Flinders University, AustraliaMatteo Panero, University of Turin, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Mikhaylova and Dokuka. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Oxana Mikhaylova, b21pa2hhaWxvdmFAaHNlLnJ1; Sofia Dokuka, c2Rva3VrYUBoc2UucnU=

Oxana Mikhaylova

Oxana Mikhaylova Sofia Dokuka

Sofia Dokuka