1 Introduction

Compared to their monolingual peers, bilingual children may experience different developmental routes and rates in cognitive and social-emotional skills due to their unique dual language experience, which includes frequent language switching. Previous studies have predominantly focused on the relationship between child bilingualism and cognitive development, with relatively less attention given to the association between child dual language learning and social-emotional wellbeing (Halle et al., 2011). In fact, bilingual children must navigate between two sets of cultural expectations that have distinct goals for behavior that relates to social-emotional development (Halle et al., 2014). This negotiation of cultural expectations occurs for various reasons, across different aspects of life, and with a wide range of people (Grosjean, 2010).

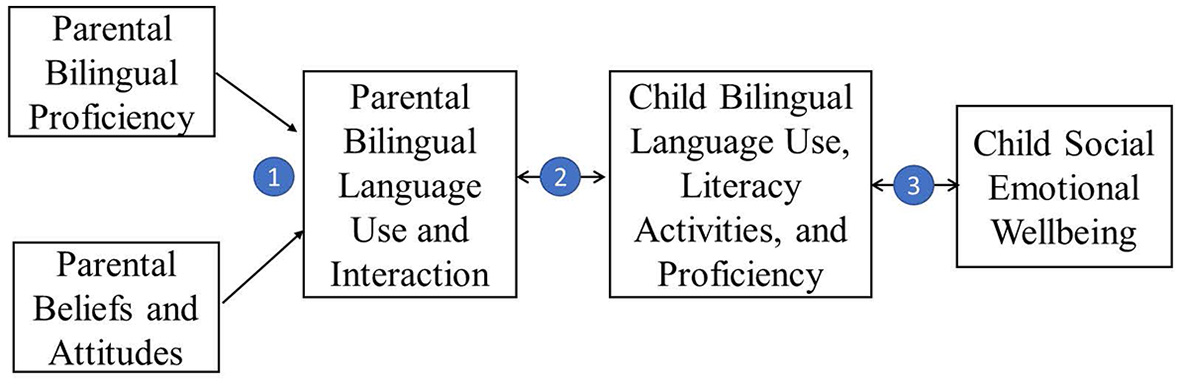

Effective communication between bilingual children and key stakeholders (e.g., parents, peers, and teachers) equip children with better skills to adapt to new environments and reduces the risk of internalizing and externalizing issues (Han, 2010). Parents play a particularly important role during the process, as “children's socio-emotional skills are thought to originate in the home environment” (Farver et al., 2006, p. 198). Not only does parents' language use influence their children's language use, literacy practices, and language competence, it also passes on their cultural values and beliefs (Halle et al., 2014). As children's first teachers, their interaction with their children not only lays the basis for their learning of social norms and behaviors, but also helps children form their self-concept and develop social adjustment (Oller and Jarmulowicz, 2007). Therefore, it is important to investigate parents' language use and its antecedents, to explore their impact on children's bilingual experience. In this opinion paper, I propose a holistic framework on Harmonious Bilingual Experience (HBE), a concept derived from Harmonious Bilingual Development (De Houwer, 2015), to address:

-

1) How parents' bilingual perception and proficiency may influence their language use,

-

2) How parental language use would influence their children's language use, literacy activities, and dual language proficiency,

-

3) How children's bilingual experience is related to their language and social-emotional skills.

As the relationship between children's HBE and their social-emotional wellbeing is the focus of our discussion, we review the major findings about this relationship first, before discussing parental factors. To conclude, I present a four-tiered conceptual framework to link the three parts of the review, addressing the relationship between parental language perception and proficiency, parent and child language use, and child social emotional wellbeing.

2 Child bilingual experience and their social-emotional wellbeing

Social-emotional wellbeing is a comprehensive concept that encompasses interrelated areas of social and emotional competence, including skills related to social interactions such as self-regulation, conflict resolution, and the establishment and maintenance of positive peer relationships (SAGE Reference, 2016). The literature reveals that both internal and external factors can affect the social-emotional and behavioral skills of bilingual children (Han, 2010; Sun et al., 2021). In this paper, I will specifically focus on three components: language use, exposure to literacy, and bilingual proficiency.

2.1 Child dual language use

Vygotsky (1962) conceptualized language as a vital social tool learned and developed through interactions with others. Children's use of language in interactions with various interlocutors is the primary means for them to grow in both linguistic and social competence. Bilingual children navigate a complex social world, where individuals in their social network possess differing language knowledge (Byers-Heinlein and Lew-Williams, 2013). Furthermore, they are likely to be exposed to a variety of socialization practices through language from parents and caregivers. In comparison to their monolingual peers, bilingual children may excel in differentiating between these socialization cues and responding appropriately in diverse social contexts (Halle et al., 2014). This, in turn, facilitates communication and fosters better relationships with peers, teachers, and family (Han, 2010). The more opportunities bilingual children have for communication, the greater their chances of developing social skills (Coelho et al., 2018), forming a positive feedback loop (Gallagher, 1999).

Empirical studies have demonstrated this positive link. In a study of 805 Singaporean bilingual preschoolers, Sun et al. (2021) discovered that the number of months children had been speaking both of their languages was significantly and positively related to their prosocial skills, even after controlling for multiple covariates such as socioeconomic status and gender. Similar evidence has been found for immigrant children, whose use of the societal dominant language is associated with positive relationships with peers (Chen and Tse, 2010) and teachers (Ren and Wyver, 2016). Beyond the use of societal dominant languages, children's heritage languages are critical for their social-emotional development. Tannenbaum and Howie (2002) found that children's use of heritage languages at home was associated with their perception of their family as cohesive and egalitarian. Children who perceived their families in this way were more likely to speak and maintain their parents' language.

2.2 Home literacy activities

Home literacy activities, book reading in particular, have been shown to be connected to child social-emotional skills as well. The positive association is supported by Farver et al.'s (2006) finding, who found that low SES Latino mothers' literacy involvement (e.g., home reading frequency), was linked to their children's better social competency in the US. Sun (2019) confirmed the results, finding that Chinese literacy activities such as library visits and parent-child shared reading sessions were associated with lower child difficulty level and better prosocial skills in Singapore.

The benefits of reading for social-emotional wellbeing may stem from the content of children's books, as well as the nature of the activity. Books targeted at children are often rich in socio-emotional content: Dyer et al. (2000) found that in 90 children's books, on average, a reference to social events or emotions occurred every three sentences. These books are often centered around interactions between people or personifications and are a good source of exposure to emotional states and social situations (Aram and Aviram, 2009). Looking at illustrations in these books also gives young readers the opportunity to reflect on and discuss the behaviors, feelings, relationships, and differing intentions and perspectives of book characters (Murray et al., 2016; Sun, 2022). Additionally, adults often discuss important social-emotional concepts (e.g., sharing) with children during shared book reading (Sun, 2022), which can help children better understand these notions. Home literacy activities are thus important bases where children are exposed to social norms and moral behavior and develop the language skills that they can use to enact said norms and behaviors. While it is crucial, it should be noted that a literary tradition in the heritage language might not be readily available across all ethnicities. Therefore, bilingual parents may not be able or willing to read in the majority language in some cultures.

2.3 Dual language proficiency

Language ability is positively associated with children's social competence: As children grow in language proficiency, so does their ability to use the language to communicate. For bilingual children, the ability to communicate in both societal and home languages is important to their social emotional wellbeing (Han, 2010; Sun et al., 2021). At home, the use of heritage languages is believed to be conducive to good family relationships (Ren and Wyver, 2016). Boutakidis et al. (2011) found that adolescents' heritage language fluency among Chinese and Korean immigrant families was positively related to their respect for parents, a relationship mediated by quality of communication. The authors argue that these positive effects go beyond simple communication. Language is the main tool that parents can use to convey cultural values and beliefs (Halle et al., 2014), including terms and concepts unique to heritage languages such as honorifics or titles of respect (Boutakidis et al., 2011). Sharing a language can improve the quality of communication, promoting cultural understanding and a shared view of the world.

In the school setting, children's societal language proficiency seems to be important for obtaining peer acceptance and getting involved in peer activities (Chen and Tse, 2010). Pallotti (1996) presents the example of a Moroccan girl in an Italian preschool, whose early Italian language proficiency consisted largely of phrases that would gain her access to peer interaction. Children who do not speak the societal language well often face bullying and victimization by their monolingual peers (De Houwer, 2020), which can cause psychological harm. For instance, Hispanic bilingual children with lower English proficiency in kindergarten were found to exhibit more externalizing behaviors than their peers with higher English proficiency (Dawson and Williams, 2008).

3 Child bilingual experience and their parental language use, perception, and proficiency

The three key bilingual factors (i.e., child dual language use, literacy practice, and bilingual proficiency) are positively associated with children's home and school language environment (De Houwer, 2018; Sun et al., 2020; Luo and Song, 2022), as well as child agency (Schwartz and Mazareeb, 2023). Among which, parents play a critical role in children's early bilingual development. Various studies reveal that parents' and children's current language use patterns are highly correlated (e.g., Bedore et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2021, 2022), and parental language use is also significantly associated with the home literacy environment: those who speak to their children more in a language also tend to conduct more literacy activities in that language (e.g., Baker, 2014). Lastly, the quantity and quality of parental language use has also been consistently found to affect bilingual children's semantic and morphosyntactic development (Cobo-Lewis et al., 2002).

Various factors, including familial socio-economic status, can influence parents' language input (Hoff, 2005). Among which, parental language perception and proficiency have been consistently found to influence the quantity and quality of parental language use (De Houwer, 1999; Paradis, 2011; Surrain, 2021). De Houwer (1999) emphasizes the importance of parental attitudes and impact belief, which affects their language choices and interaction strategies used with their children, which in turn affects their children's language development. Parents who harbor positive attitudes toward bilingualism are believed to aid their children's bilingual development (De Houwer, 1999). Although being crucial, positive bilingual perception alone is insufficient to promote HBE. Curdt-Christiansen (2016) presented a case where a parent mainly spoke English to their children at home, despite claiming positive attitudes toward Malay language.

One possible reason for this could be parental language proficiency. While parents may want to speak to their children in a certain language, they may lack the proficiency to do so regularly. Sun et al. (2022) found that amongst English–Mandarin bilingual mothers in Singapore, a high self-evaluated Mandarin proficiency corresponded to a significantly higher amount of Mandarin spoken to their children compared to low or medium proficiency mothers. Low and medium proficiency mothers tended to use significantly more English than Mandarin, compared to high proficiency mothers.

Parental proficiency could also affect the quality of their input. Mothers with high L2 proficiency were found to have a larger vocabulary size (Bialystok, 2009) and use more varied and complex words with their children (Rowe, 2012; Hoff et al., 2020). Their proficiency has been found to affect children's literacy activity. Baker (2014) found those mothers who were more proficient in English engaged in more English literacy activities with their children such as singing songs, shared book reading, or visiting the library.

4 Harmonious bilingual experience: a four-tiered conceptual framework

The review above leads to a four-tier conceptual framework demonstrated in Figure 1. In the bilingual home setting, parent's perception of bilingualism and their proficiency in dual languages impact the extent of their language use with their children, which in turn influences their children's bilingual use, literacy activities, and dual language skills. These three aspects of children's bilingual experience eventually impact their social-emotional wellbeing, such as prosocial skills and emotion recognition, even controlling the direct impact of parental social-emotional wellbeing. The current four-tier conceptual framework calls for large-scale and longitudinal studies to verify the potential chain of effects unidirectionally or bidirectionally. It highlights the necessity of doing research on early bilingualism across domains, with united efforts from linguists, developmental psychologists, and educators. It is worth noting that other distal (e.g., educational policy, familial SES) and proximal factors (e.g., child's communicative needs) would also affect the chain of effect and future research should control these covariates when examining the framework.

Figure 1

Harmonious bilingual experience: a four-tiered conceptual framework.

Statements

Author contributions

HS: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Singapore Ministry of Education (MOE) under the Education Research Funding Programme (OER 13/19 HS) and administered by National Institute of Education (NIE), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Nathaniel Hong for the discussions and proofreading of the paper.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Singapore MOE and NIE.

References

1

Aram D. Aviram S. (2009). Mother's storybook reading and kindergartners' socioemotional and literacy development. Reading Psychol.30, 175–194. 10.1080/02702710802275348

2

Baker E. C. (2014). Mexican mothers' English proficiency and children's school readiness: mediation through home literacy involvement. Early Educ. Dev.25, 338–355. 10.1080/10409289.2013.807721

3

Bedore L. M. Peña E. D. Summers C. L. Boerger K. M. Resendiz M. D. Greene K. et al . (2012). The measure matters: language dominance profiles across measures in Spanish-English bilingual children. Bilingualism Lang. Cognit.15, 90. 10.1017/S1366728912000090

4

Bialystok E. (2009). Bilingualism: the good, the bad, and the indifferent. Bilingualism Lang. Cognit.12, 3–11. 10.1017/S1366728908003477

5

Boutakidis I. P. Chao R. K. Rodríguez J. L. (2011). The role of adolescents' native language fluency on quality of communication and respect for parents in Chinese and Korean immigrant families. Asian Am. J. Psychol.2, 128–139. 10.1037/a0023606

6

Byers-Heinlein K. Lew-Williams C. (2013). Bilingualism in the early years: what the science says. Learn Landsc. 7, 95–112. 10.36510/learnland.v7i1.632

7

Chen X. Tse H. C. (2010). Social and psychological adjustment of Chinese Canadian children. Int. J. Behav. Dev.34, 330–338. 10.1177/0165025409337546

8

Cobo-Lewis A. Pearson B. Z. Eilers R. E. Umbel V. C. (2002). “Effects of bilingualism and bilingual education on oral and written English skills: a multifactor study of standardized test outcomes,” in Language and Literacy in Bilingual Children, eds K. Oller, and R. E. Eilers (London: Multilingual Matters), 64–98.

9

Coelho V. Cadima J. Pinto A. I. Guimarães C. (2018). Self-regulation, engagement, and developmental functioning in preschool-aged children. J. Early Interv.41, 238. 10.1177/1053815118810238

10

Curdt-Christiansen X. L. (2016). Conflicting language ideologies and contradictory language practices in Singaporean bilingual families. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev.37, 694–709. 10.1080/01434632.2015.1127926

11

Dawson B. A. Williams S. A. (2008). The impact of language status as an acculturative stressor on internalizing and externalizing behaviors amongst Latino/a children: a longitudinal analysis from school entry through third grade. J. Youth Adoles.37, 399–411. 10.1007/s10964-007-9233-z

12

De Houwer A. (1999). “Environmental factors in early bilingual development: the role of parental beliefs and attitudes,” in Bilingualism and Migration, eds G. Extra and L. Verhoeven (London: De Gruyter), 75–96.

13

De Houwer A. (2015). Harmonious bilingual development: young families' well-being in language contact situations. Int. J. Biling.19, 169–184. 10.1177/1367006913489202

14

De Houwer A. (2018). “The role of language input environments for language outcomes and language acquisition in young bilingual children,” in Bilingual Cognition and Language: The State of the Science Across Its Subfields, eds D. Miller, F. Bayram, J. Rothman, and L. Serratrice (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 127–153.

15

De Houwer A. (2020). “Harmonious bilingualism: well-being for families in bilingual settings,” in Handbook of Social and Affective Factors in Home Language Maintenance and Development, eds S. Eisenchlas and A. Schalley (London: De Gruyter), 63–83.

16

Dyer J. R. Shatz M. Wellman H. M. (2000). Young children's storybooks as a source of mental state information. Cognit. Dev.15, 17–37. 10.1016/S0885-2014(00)00017-4

17

Farver J. A. M. Xu Y. Eppe S. Lonigan C. J. (2006). Home environments and young Latino children's school readiness. Early Childhood Res. Q. 21, 196–212. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.04.008

18

Gallagher T. M. (1999). Interrelationships among children's language, behavior, and emotional problems. Topics Lang. Disorder19, 1–15. 10.1097/00011363-199902000-00003

19

Grosjean F. (2010). Bilingual: Life and Reality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

20

Halle T. Castro D. Franco X. McSwiggan M. Hair E. Wandner L. (2011). “The role of early care and education in the development of young Latino dual language learners,” in Latina and Latino Children's Mental Health, eds N. Cabrera, F. Villarruel, and H. Fitzgerald (England: ABC-CLIO), 63–90.

21

Halle T. G. Whittaker J. V. Zepeda M. Rothenberg L. Anderson R. Daneri P. et al . (2014). The social-emotional development of dual language learners: looking back at existing research and moving forward with purpose. Early Childhood Res. Q. 29, 734–749. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.12.002

22

Han W. J. (2010). Bilingualism and socioemotional well-being. Children Youth Serv. Rev. 32, 720–731. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.01.009

23

Hoff E. (2005). (2006). How social contexts support and shape language development. Dev. Rev.26, 55–88. 10.1016/j.dr.2005.11.002

24

Hoff E. Core C. Shanks K. F. (2020). The quality of child-directed speech depends on the speaker's language proficiency. J. Child Lang.47, 132–145. 10.1017/S030500091900028X

25

Luo R. Song L. (2022). The unique and compensatory effects of home and classroom learning activities on Migrant and Seasonal Head Start children's Spanish and English emergent literacy skills. Front. Psychol. 13, 1016492. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1016492

26

Murray L. de Pascalis D. Tomlinson L. Valley M. Dadomo Z. MacLachlan H. et al . (2016). Randomized controlled trial of a book-sharing intervention in a deprived South African community: effects on carer-infant interactions, and their relation to infant cognitive and socioemotional outcome. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatr.57, 1370–1379. 10.1111/jcpp.12605

27

Oller D. K. Jarmulowicz L. (2007). “Language and literacy in bilingual children in the early school years,” in Blackwell Handbook of Language Development, eds E. Hoff and M. Shatz (London: Blackwell Publishing), 368–386.

28

Pallotti G. (1996). “Towards an ecology of second language acquisition: SLA as a socialization process,” in Proceedings of EUROSLA 6, Toegepaste Taalwetenschap in Artikelen, eds E. Kellerman, B. Weltens, and T. Bongaerts (Amsterdam: VU Uitgeverij), 121–134.

29

Paradis J. (2011). Individual differences in child English second language acquisition: comparing child-internal and child-external factors. Linguistic Approaches Bilingualism1, 213–237. 10.1075/lab.1.3.01par

30

Ren Y. G. Wyver S. (2016). Bilingualism and development of social competence of english language learners: a review. Child Stu. Asia-Pacific Contexts6, 17–29. 10.5723/csac.2016.6.1.017

31

Rowe M. L. (2012). A longitudinal investigation of the role of quantity and quality of child-directed speech in vocabulary development. Child Dev.83, 1762–1744. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01805.x

32

SAGE Reference (2016). “Social-emotional development,” in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Contemporary Early Childhood Education, Vol. 3, eds D. Couchenour, and J. L. Chrisman (London: SAGE Reference), 1251–1255.

33

Schwartz M. Mazareeb E. (2023). Exploring children's language-based agency as a gateway to understanding early bilingual development and education. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev.8, 1–16. 10.1080/01434632.2023.2224783

34

Sun H. (2019). Home environment, bilingual preschooler's receptive mother tongue language outcomes, and social-emotional and behavioral skills: one stone for two birds?Front. Psychol.10, 1–13. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01640

35

Sun H. (2022). “Harmonious bilingual development: the concept, the significance, and the implications,” in Early Childhood Development and Education in Singapore, eds S. T. Oon, K. K. Poon, and B. A. O'Brien (Singapore: Springer Singapore), 261–280.

36

Sun H. Low J. M. Chua I. (2022). Maternal heritage language proficiency and child bilingual heritage language learning. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling.26, 861–875. 10.1080/13670050.2022.2130153

37

Sun H. Ng S. C. O'Brien B. A. Fritzsche T. (2020). Child, family, and school factors in bilingual preschoolers' vocabulary development in heritage languages. J. Child Lang.47, 817–843. 10.1017/S0305000919000904

38

Sun H. Yussof N. Mohamed M. Rahim A. Bull R. Cheung W. L. et al . (2021). Bilingual language experience and social-emotional well-being: a cross-sectional study of Singapore pre-schoolers. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling.24, 324–339. 10.1080/13670050.2018.1461802

39

Surrain S. (2021). ‘Spanish at home, English at school': how perceptions of bilingualism shape family language policies among Spanish-speaking parents of preschoolers. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling.24, 1163–1177. 10.1080/13670050.2018.1546666

40

Tannenbaum M. Howie P. (2002). The association between language maintenance and family relations: Chinese immigrant children in Australia. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev.23, 408–424. 10.1080/01434630208666477

41

Vygotsky L. (1962). Thought and Language. London: MIT Press.

Summary

Keywords

harmonious bilingualism, social-emotional wellbeing, child bilingualism, language output, shared book reading, dual language proficiency

Citation

Sun H (2023) Harmonious bilingual experience and child wellbeing: a conceptual framework. Front. Psychol. 14:1282863. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1282863

Received

05 September 2023

Accepted

10 November 2023

Published

24 November 2023

Volume

14 - 2023

Edited by

Elena Nicoladis, University of Alberta, Canada

Reviewed by

Ily Hollebeke, Vrije University Brussels, Belgium

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Sun.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: He Sun he.sun@nie.edu.sg

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.